WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES.

Hawker’s prose sketches appeared originally as contributions to various periodicals, and in 1870 they were published for him in book form by Mr. John Russell Smith, as “Footprints of Former Men in Far Cornwall.” In 1893, eighteen years after his death, a new edition was issued by Messrs. Blackwood, entitled “The Prose Works of Rev. R. S. Hawker,” containing two essays previously unpublished, “Humphrey Vivian” and “Old Trevarten.” The late Mr. J. G. Godwin, who was Hawker’s friend and adviser in literary matters, edited the volume, and added the bibliographical footnotes to the several papers. In the present edition it has been thought appropriate to revert to Hawker’s own more picturesque title, and this is to be done also in the case of his poetical works, which will shortly be re-issued as “Cornish Ballads and other Poems.” The two books will thus form companion volumes. It is interesting to read them concurrently, and to compare his treatment of the same themes in prose and verse. An[vi] attempt has been made in the notes to assist such a comparison by indicating some of the more obvious parallels. In the prose, as in the poems, there is the same deep and peculiar love of symbol and miracle and superstition, but the prose further reveals, what might not be suspected from the poems alone, that Hawker was a humourist as much as a mystic.

Hawker won his literary reputation as a ballad-writer, but his prose also deserves a share in his fame. He has the gift of style. Like his handwriting, which makes a manuscript of his a thing of beauty in itself, it is bold and clear, free from prettiness or affectation, but with the massive grace of his native rocks, and made distinctive by a characteristic touch of archaism. The rugged scenery of his abode had its influence upon his work. He was a hewer of words, as Daniel Gumb was a hewer of stone, and his language has the strength of rough masonry wrought in a broad and homely manner out of solid granite. The sea, and the great spaces of lonely moorland that surrounded him, gave to his work a sense of breadth and freedom. He is always at his best in describing his own dearly loved Cornwall, and in particular the wild coast by which all his years were spent. Perhaps the finest passage of this kind is that which concludes the legend of Daniel Gumb, and which forms[vii] a prose counterpart to that grand ending of “The Quest of the Sangraal:”

There is an element of fiction in Hawker’s biographical studies. He never let facts, or the absence of them, stand in the way of his imagination, and he had a Chattertonian habit of passing off compositions of his own as ancient manuscripts.

His letters are full of complaints that legends “invented” by himself have been regarded by others as common property. But this is not surprising when the said inventions wear the solemn garb of history. Hawker had many of the qualities necessary to historical romance. His rich native humour, and his rare gift for telling a story; his vivid presentment of scene, character, and situation, make it a matter of regret that he did not apply his powers more fully in this direction, just as it is a matter of regret that his fine poem, “The Quest of the Sangraal,” is only a fragment, though a fragment worthy to rank beside “Hyperion.”

Both in his prose and his poetry there is a disappointing lack of sustained effort. His literary manner and antiquarian tastes bear many[viii] points of resemblance to those of Scott, whose novels it was his custom to re-read every year as Christmas-time came round. In his local and scanty degree Hawker has done for the legends and worthies of old Cornwall what Sir Walter did for those of Scotland.

The prose impulse seems to have moved Hawker somewhat late in life, all the following papers having been published since 1850, when he had reached the age of forty-seven. These papers, as a matter of fact, represent a brave effort in years of increasing pecuniary anxiety to add to his income by his pen. His letters contain many interesting allusions to his literary struggles and his dealings with the editors of his day, among whom were Froude and Dickens. He also met or corresponded with several other famous contemporaries, including Tennyson, Longfellow, Kingsley, and Cardinals Newman and Manning. Earlier, too, he had a correspondence with Macaulay. But on these matters it will be more fitting to enlarge in the new memoir of Hawker, which is in course of preparation.

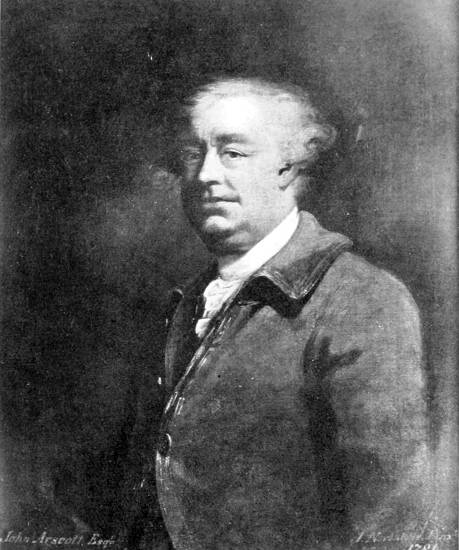

It remains for me to express my warmest thanks to those who have helped in the production of this volume. Mr. R. Pearse Chope has been indefatigable in collecting matter for the Appendix, and his are the notes on “Morwenstow,” “Daniel Gumb’s Rock,” “Cruel[ix] Coppinger,” and “Thomasine Bonaventure.” This Appendix, it is hoped, will be of interest both in itself and as showing the sources of Hawker’s information. It enables us, too, to judge his power of imparting colour and romance to a plain record of facts. The account of old Stowe and the Granvilles, and their gigantic retainer, Antony Payne, has been kindly furnished by a descendant of the great Sir Bevill, the Rev. Prebendary Roger Granville, and it has thus a double interest. Mrs. Waddon Martyn of Tonacombe Manor, Morwenstow, and her son, Mr. N. H. Lawrence Martyn, have been especially kind and helpful. The Rev. John Tagert, Vicar of Morwenstow, and his daughter, Miss Tagert, Miss Rowe of Poughill, Miss Louisa Twining, Mr. and Mrs. William Shephard, the Rev. Canon Bone, the Rev. Ll. W. Bevan of Stratton, Mr. J. Sommers James, and the Rev. H. Upton Squire of Tetcott, have also rendered generous and valuable assistance. The portraits of Black John, Arscott of Tetcott, and Parson Rudall have been reproduced from pictures kindly lent by Mrs. Calmady, Mrs. Ford of Pencarrow, and the Rev. S. Baring-Gould respectively. The portrait of Black John was formerly in the possession of Mr. Hawker.

These acknowledgments would be incomplete if they did not refer to the zealous care bestowed[x] by Mr. J. Ley Pethybridge on his charming illustrations. His work has been to a large extent a labour of love. Thanks are also due to the various photographers, amateur and professional, who have lent their aid. Mr. George Penrose, Curator of the Royal Institution of Cornwall at Truro, kindly photographed the painting of Antony Payne and the flask which formerly belonged to the giant. The Manning tomb is from a photo by Mr. T. W. Woodruffe. The interior of Morwenstow Church as it was in Hawker’s time is by S. Thorn of Bude, as is also the piscina.

C. E. Byles.

June, 1903.

| PAGE | |

| Morwenstow | 1 |

| The First Cornish Mole | 27 |

| The Gauger’s Pocket | 32 |

| The Light of Other Days | 41 |

| The Remembrances of a Cornish Vicar | 46 |

| Black John | 79 |

| Daniel Gumb’s Rock | 90 |

| Antony Payne, a Cornish Giant | 109 |

| Cruel Coppinger | 123 |

| Thomasine Bonaventure | 139 |

| The Botathen Ghost | 158 |

| A Ride from Bude to Boss | 176 |

| Holacombe | 199 |

| Humphrey Vivian | 216 |

| Old Trevarten: A Tale of the Pixies | 234 |

| APPENDICES | 241 |

The Design on the Title-page, by Mr. J. Ley Pethybridge, represents the Carving of The Fruitful Vine, in Welcombe Church.

The Panel Design on the Front Cover represents a Bench End in Morwenstow Church; that of the Border is the Vine Carving of the Roof (see p. 15).

The Panel Design on the Back represents the Carving of The Barren Fig-tree, in Welcombe Church.

FOOTPRINTS OF FORMER MEN IN FAR CORNWALL

There cannot be a scene more graphic in itself, or more illustrative in its history of the gradual growth and striking development of the Church in Celtic and Western England, than the parish of St. Morwenna. It occupies the upper and northern nook of the county of Cornwall; shut in and bounded on the one hand by the Severn Sea, and on the other by the offspring of its own bosom, the Tamar River, which gushes, with its sister stream the Torridge, from a rushy knoll on the eastern wilds of Morwenstow.[2][2] Once, and in the first period of our history, it was one wide wild stretch of rocky moorland, broken with masses of dunstone and the sullen curve of the warrior’s barrow, and flashing here and there with a bright rill of water or a solitary well. Neither landmarks nor fences nor walls bounded or severed the bold, free, untravelled Cornish domain. Wheel-tracks in old Cornwall there were none; but strange and narrow paths gleamed across the moorlands, which the forefathers said in their simplicity, were first traced by angel’s feet.[3] These, in truth, were trodden and worn by religious men—by the pilgrim as he paced his way toward his chosen and votive bourn, or by the palmer, whose listless footsteps had neither a fixed keblah nor a future abode. Dimly visible by the darker hue of the crushed grass, these straight and narrow roads led the traveller along from chapelry to cell, or to some distant and solitary cave. On the one hand, in this scenery of the past, they would guide us to the “Chapel-piece of St. Morwenna,” a grassy glade along the gorse-clad cliff, where to this very day neither will bramble cling nor heather grow; and, on the other, to the walls and roof and the grooved stone for the waterflow, which still survive, halfway down a headlong precipice, as the relics of St.[3] Morwenna’s Well.[4] But what was the wanderer’s guidance along the bleak, unpeopled surface of these Cornish moors? The wayside cross. Such were the crosses of St. James and St. John, which even yet give name to their ancient sites in Morwenstow, and proclaim to the traveller that, or ever a church was reared or an altar hallowed here, the trophy of old Syria stood in solemn stone, a beacon to the wayfaring man, and that the soldiers of God’s army had won their honours among the unbaptised and barbarous people!

Here, then, let us stand and survey the earliest scenery of pagan Morwenstow. Before us lies a breadth of wild and rocky land; it is bounded by the billowy Atlantic, with its arm of waters, and by the slow lapse of that gliding stream of which the Keltic proverb said, before King Arthur’s day,—

Barrows curve above the dead; a stony cross stands by a mossed and lichened well; here and there glides a shorn and vested monk, whose function it was, often at peril of life and limb, to sprinkle the brow of some hard-won votary,[4] and to breathe the Gospel of the Trinity on the startled ear of the Keltic barbarian. Let us close this theme of thought with a few faint echoes from the River of the West:—

Then arrived, to people this bleak and lonely boundary with the thoughts and doctrines of the Cross, the piety and the legend of St. Morwenna. This was the origin of her name and place.

There dwelt in Wales in the ninth century a Keltic king, Breachan[5] by name—it was from him that the words “Brecon” and “Brecknock” received origin; and Gladwys was his wife and queen. They had, according to the record of Leland, the scribe, children twenty-and-four. Now either these were their own daughters and sons, or they were, according to the usage of those days, the offspring of the nobles of their land, placed for loyal and learned nurture in the palace of the king, and so called the children of his house.

Of these Morwenna was one. She grew up wise, learned, and holy above her generation; and it was evermore the strong desire of her soul to bring the barbarous and pagan people[6] among whom she dwelt to the Christian font. Now so it was that when Morwenna was grown up to saintly womanhood there was a king of Saxon England, and Ethelwolf was his noble name. This was he who laid the endowment of his realm of England on the altar of the Apostles at Rome, the first and eldest Church-king of the islands who occupied the English throne. He, Ethelwolf, had likewise many children; and while he intrusted to the famous St. Swithun the guidance of his sons, he besought King Breachan to send to his court Morwenna, that she might become the teacher of the Princess Edith and the other daughters of his royal house.[6] She came. She sojourned in his palace long and patiently; and she so gladdened King Ethelwolf by her goodness and her grace, that at last he was fain to give her whatsoever she sought.

Now the piece of ground, or the acre of God, which in those old days was wont to be set apart or hallowed for the site of a future shrine and church, was called the “station,” or in native speech the “stowe,” of the martyr or saint whose name was given to the altar-stone. So, on a certain day thus came and so said Morwenna to the King: “Largess, my lord the king, largess, for God’s sake!” “Largess, my daughter?”[7] answered Ethelwolf the king; “largess! be it whatsoever it may.” Then said Morwenna: “Sir, there is a stern and stately headland in thy appanage of the Tamar-land, it is a boundary rugged and tall, and it looks along the Severn Sea; they call it in that Keltic region Hennacliff—that is to say, the Raven’s Crag—because it hath ever been for long ages the haunt and the home of the birds of Elias.[7] Very often, from my abode in wild Wales, have I watched across the waves until the westering sun fell red upon that Cornish rock, and I have said in my maiden vows, ‘Alas! and would to God a font might be hewn and an altar built among the stones by yonder barbarous hill.’ Give me, then, as I beseech thee, my lord the king, a station for a messenger and a priest in that scenery of my early prayer, that so and through me the saying of Esaias the seer may come to pass, ‘In the place of dragons, where each lay, there may be grass with reeds and rushes.’”

Her voice was heard; her entreaty was fulfilled. They came at the cost and impulse of Morwenna; they brought and they set up yonder font, with the carved cable coiled around it in stone, in memory of the vessel of the fishermen of the East anchored in the Galilæan Sea. They built there altar and arch, aisle and device in stone. They linked their earliest structure with[8] Morwenna’s name, the tender and the true; and so it is that notwithstanding the lapse of ten whole centuries of English time, at this very day the bourn of many a pilgrim to the West is the Station of Morwenna, or, in simple and Saxon phrase, Morwenstow. So runs the quaint and simple legend of our Tamar-side; and so ascend into the undated era of the ninth or tenth age the early Norman arches, font, porch, and piscina of Morwenstow church.[8]

The endowment, in abbreviated Latin, still exists in the registry of the diocese.[9] It records that the monks of St. John at Bridgewater, in whom the total tithes and glebe-lands of this parish were then vested, had agreed, at the request of Walter Brentingham, the Bishop of Exeter, to endow an altar-priest with certain lands, bounded on the one hand by the sea, and on the other by the Well of St. John of the Wilderness, near the church. They surrendered, also, for this endowment the garbæ of two bartons of vills, Tidnacomb[10] and Stanbury, the altarage, and the small tithes of the parish. But the striking point in this ancient document is that, whereas the date of the endowment is A.D. 1296, the church is therein referred to by name as an old[9] and well-known structure. To such a remote era, therefore, we must assign the Norman relics of antiquity which still survive, and which, although enclosed within the walls and outline of an edifice enlarged and extended at two subsequent periods, have to this day undergone no material change.

We proceed to enumerate and describe these features of the first foundation of St. Morwenna,[11] and to which I am not disposed to assign a later origin than from A.D. 875 to A.D. 1000.

First among these is a fine Norman doorway at the southern entrance of the present church. The arch-head is semicircular, and it is sustained on either side by half-piers built in stone, with capitals adorned with different devices; and the curve is crowned with the zigzag and chevron mouldings. This moulding is surmounted by a range of grotesque faces—the mermaid and the dolphin, the whale, and other fellow-creatures of the deep; for the earliest imagery of the primeval hewers of stone was taken from the sea, in unison with the great sources of the Gospel,—the Sea of Galilee, the fishing men who were to haul the net, and the “catchers of men.” The crown of the arch is adorned with a richly carved, and even eloquent, device: two dragons are crouching in the presence of a lamb, and underneath his conquering feet lies their passive chain.

But it is time for us to unclose the door and enter in. There stands the font in all its emphatic simplicity. A moulded cable girds it on to the mother church; and the uncouth lip of its circular rim attests its origin in times of a rude taste and unadorned symbolism. For wellnigh ten centuries the Gospel of the Trinity has sounded over this silent cell of stone, and from the Well of St. John[12] the stream has glided in, and the water gushed withal, while another son or daughter has been added to the Christian family. Before us stand the three oldest arches of the Church in ancient Cornwall. They curve upon piers built in channelled masonry, a feature of Norman days which presents a strong contrast with the grooved pillars of solid or of a single stone in succeeding styles of architecture. The western arch is a simple semicircle of dunstone from the shore, so utterly unadorned and so severe in its design that it might be deemed of Saxon origin, were it not for its alliance with the elaborate Norman decoration of the other two. These embrace again, and embody the ripple of the sea and the monsters that take their pastime in the deep waters. But there is one very graphic “sermon in stone” twice repeated on the curve and on the shoulder of the arch. Our forefathers[11] called it (and our people inherit their phraseology) “The Grin of Arius.” The origin of the name is this. It is said that the final development of every strong and baleful passion in the human countenance is a fierce and angry laugh. In a picture of the Council of Nicæa, which is said still to exist, the baffled Arius is shown among the doctors with his features convulsed into a strong and demoniac spasm of malignant mirth. Hence it became one of the usages among the graphic imagery of interior decoration to depict the heretic as mocking the mysteries with that glare of derision and gesture of disdain, which admonish and instruct, by the very name of “The Grin of Arius.” Thence were derived the lolling tongue and the mocking mouth which are still preserved on the two corbels of stone in this early Norman work. To this period we must also allot the piscina,[13] which was discovered and rescued from desecration by the present vicar.

The chancel wall one day sounded hollow when struck; the mortar was removed, and underneath there appeared an arched aperture, which had been filled up with jumbled carved work and a crushed drain. It was cleared out, and so rebuilt as to occupy the exact site of its former existence. It is of the very earliest type of Christian architecture, and, for aught we know, it may be the oldest piscina in all the land. At all events, it can[12] scarcely have seen less than a thousand years. It perpetuates the original form of this appanage of the chancel; for the horn of the Hebrew altar,[14] as is well known to architectural students, was in shape and in usage the primary type of the Christian piscina. These horns were four, one at each corner, and in outline like the crest of a dwarf pillar, with a cup-shaped mouth and a grooved throat, to receive and to carry down the superfluous blood and water of the sacrifices into a cistern or channel underneath. Hence was derived the ecclesiastical custom that, whenever the chalice or other vessel had been rinsed, the water was reverently poured into the piscina, which was usually built into a carved niche of the southward chancel wall. Such is the remarkable relic of former times which still exists in Morwenstow church, verifying, by the unique and remote antiquity of its pillared form, its own primeval origin.

But among the features of this sanctuary none exceed in singular and eloquent symbolism the bosses of the chancel roof. Every one of these is a doctrine or a discipline engraven in the wood by some Bezaleel or Aholiab of early Christian days. Among these the Norman rose and the fleur-de-lis have frequent pre-eminence. The one, from the rose of Sharon downward, is the pictured type of our Lord; the other, whether as the lotus of the[13] Nile or the lily of the vale, is the type of His Virgin Mother; and both of these floral decorations were employed as ecclesiastical emblems centuries before they were assumed into the shields of Normandy or England. Another is the double-necked eagle, the bird of the Holy Ghost in the patriarchal and Mosaic periods of revelation, just as the dove afterwards became in the days of the Gospel; and, mythic writers having asserted that when Elisha sought and obtained from his master “a double portion of Elijah’s spirit,” this miracle was portrayed and perpetuated in architectural symbolism by the two necks of the eagle of Elisha. Four faces cluster on another boss,—three with masculine features, and one with the softer impress of a female countenance, a typical assemblage of the Trinity and the Mother of God. Again we mark the tracery of that “piety of the birds,” as devout writers have named the fabled usage of the pelican.[15] She is shown baring and rending her own veins to nourish with her blood her thirsty offspring,—a group which so graphically interprets itself to the eye and mind of a Christian man that it needs no interpretation.

But very remarkable, in the mid-roof, is the[14] boss of the pentacle[16] of Solomon. This was the five-angled figure which was engraven on an emerald, and wherewith he ruled the demons;[17] for they were the vassals of his mighty seal: the five angles in their original mythicism, embracing as they did the unutterable name, meant, it may be, the fingers of Omnipotence as the symbolic Hand subsequently came forth in shadows on Belshazzar’s wall. Be this as it may, it was the concurrent belief of the Eastern nations that the sigil of the Wise King was the source and instrument of his supernatural power. So Heber writes in his “Palestine”—

Hence it is that we find this mythic figure, in decorated delineation, as the signal of the boundless might of Him whose Church bends over all, the pentacle of Omnipotence! Akin to this graphic imagery is the shield of David, the theme of another of our chancel-bosses. Here the outline is six-angled: Solomon’s device with one angle more, which, I would submit, was added in order to suggest another doctrine—the manhood taken into God, and so to become a typical prophecy of the Incarnation. The framework of these bosses is a cornice of vines. The root of the vines on each wall grows from the altar-side; the stem travels outward across the screen towards the nave. There tendrils cling and clusters bend, while angels sustain the entire tree.

A screen[19] divides the deep and narrow chancel from the nave. A scroll of rich device runs across it, wherein deer and oxen browse on the leaves of a budding vine. Both of these animals are the well-known emblems of the baptised, and the sacramental tree is the type of the Church grafted into God.

INTERIOR OF MORWENSTOW CHURCH AS IT WAS IN HAWKER’S TIME, SHOWING HIS ROOD SCREEN

From a photo by S. Thorn, Bude

A strange and striking acoustic result is accomplished by this and by similar chancel-screens: they act as the tympanum of the structure, and increase and reverberate the volume of sound. The voice uttered at the altar-side smites the hollow work of the screen, and is carried onward, as by some echoing instrument, into the nave and aisles; so that the lattice-work of the chancel, which at first thought might appear to impede the transit of the voice, does in reality grasp and deliver into stronger echo the ministry of tone.

Just outside the screen, and at the step of the nave, is the grave of a priest. It is identified by the reversed position of the carved cross on the stone, which also indicates the self-same attitude in the corpse. The head is laid down toward the east, while in all secular interment the head is turned to the west. Until the era of the Reformation, or possibly to a later date, the head of the priest upon the bier for burial, and afterwards in[17] the grave, was always placed “versus altare;” and, according to all ecclesiastical usage, the discipline was doctrinal also. The following is the reason as laid down by Durandus and other writers. Because the east, “the gate of the morning,” is the keblah of Christian hope, inasmuch as the Messiah, whose symbolic name was “The Orient,” thence arrived, and thence, also, will return on the chariots of cloud for the Judgment: we therefore place our departed ones with their heads westward, and their feet and faces towards the eastern sky,[20] that at the outshine of the Last Day, and the sound of the archangel, they may start from their dust, like soldiers from their sleep, and stand up before the Son of man suddenly! But the apostles were to sit on future thrones and to assist at the Judgment: the Master was to arrive for doom amid His ancients gloriously, and the saints were to judge the world. These prophecies were symbolised by the burial of the clergy, and thence, in contrast with other dead, their posture in the grave. It was to signify that it would be their office to arise and to “follow the Lord in the air,” when He shall arrive from the east and pass onward, gathering up His witnesses toward the west. Thus, in the posture of the departed multitudes, the sign is, “We look for the Son of Man: ad Orientem Judah.” And in the attitude of His appointed[18] ministers, thus saith the legend on the tombs of His priests, “They arose and followed Him.”

The eastern window of the chancel,[21] as its legend records, is the pious and dutiful oblation of Rudolph, Baron Clinton, and Georgiana Elizabeth his wife. The central figure embodies the legend of St. Morwenna, who stands in the attitude of the teacher of the Princess Edith, daughter of Ethelwolf the Founder King; on the one side is shown St. Peter, and on the other St. Paul. The upper spandrels are filled with a Syrian lamb, a pelican with her brood, and the three first letters of the Saviour’s name. The window[22] itself is the recent offering of two noble minds; and while on this theme we may be pardoned for the natural boast that the patrons of this chancel have called by the name of Morwenna one of the fair and graceful daughters of their house. “Nomen, omen,” was the Roman saying,—“Nomen, numen,” be our proverb now! But before we proceed to descend the three steps of the chancel floor, so obviously typical of Faith, Hope, and Charity, let us look westward through the[19] tower-arch; and as we look we discover that the builders, either by chance or design, have turned aside or set out of proportional place the western window of the tower. Is this really so, or does the wall of the chancel swerve? The deviation was intended, nor without an error could we render the crooked straight. And the reason is said to be this: when our Redeemer died, at the utterance of the word τετέλεσται, “It is done!” His head declined towards His right shoulder, and in that attitude He chose to die. Now it was to commemorate this drooping of the Saviour’s head, to record in stone this eloquent gesture of our Lord, that the “wise in heart,” who traced this church in the actual outline of a cross, departed from the precise rules of architect and carpenter.

The southern aisle, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, with its granite and dunstone pillars, is of the later Decorated order, and is remarkable for its singular variety of material in stone. Granite pillars are surmounted by arches of dunstone; and, vice versa, dunstone arches by pillared granite. This is again a striking example of doctrine proclaimed in structure, and is symbolic of the fact that the Spiritual Church gathered into one body every hue and kind of belief; whereas “Jew and Greek, Barbarian and Scythian, bond and free,” were to be all one in Christ Jesus: so the material building personified, in its various and visible embrace, one Church to[20] grasp, and a single roof to bend over all. This, the last addition to the ancient sanctuary of St. Morwenna, bears on the capital of a pillar the date A.D. 1475,[23] and thus the total structure stands a graphic monument of the growth and stature of a scene of ancient worship, which had been embodied and completed before the invention of printing and other modern arts had worked their revolution upon Western Europe.

The worshipper must descend three steps of stone as he enters into this aisle of St. John; and this gradation is intended to recall the time and the place where the multitude went down into the river of Dan “at Bethabara, beyond Jordan, where John was baptising.”

The churchyard of Morwenstow is the scene of other features of a remote antiquity. The roof of the total church—chancel, nave, northern and southern aisles—is of wood. Shingles of rended oak occupy the place of the usual, but far more recent, tiles which cover other churches; and it is not a little illustrative of the antique usages of this remote and lonely sanctuary, that no change has been wrought, in the long lapse of ages, in this unique and costly, but fit and durable, roofing. It supplies a singular illustration of the Syriac version of the 90th Psalm, wherein, with prophetic reference to these commemorations of the death-bed[21] of the Messias, it is written, “Lord, Thou hast been our roof from generation to generation.”

The northern side of the churchyard is, according to ancient usage, devoid of graves.[24] This is the common result of an unconscious sense among the people of the doctrine of regions—a thought coeval with the inspiration of the Christian era. This is their division.[25] The east was held to be the realm of the oracles, the especial gate of the throne of God; the west was the domain of the people—the Galilee of all nations was there; the south, the land of the mid-day, was sacred to things heavenly and divine; but the north was the devoted region of Satan and his hosts, the lair of the demon and his haunt. In some of our ancient churches, and in the church of Welcombe,[26] a hamlet bordering on Morwenstow, over against the font, and in the northern wall, there is an entrance named the Devil’s door: it was thrown open at every baptism, at the Renunciation, for the escape of the fiend; while at every other time[22] it was carefully closed. Hence, and because of the doctrinal suggestion of the ill-omened scenery of the northern grave-ground, came the old dislike[27] to sepulture on the north side, so strikingly visible around this church.

The events of the last twenty years have added fresh interest to God’s acre, for such is the exact measure of the grave ground of St. Morwenna. Along and beneath the southern trees, side by side, are the graves of between thirty and forty seamen, hurled by the sea, in shipwreck, on the neighbouring rocks, and gathered up and buried there by the present vicar and his people. The crews of three lost vessels, cast away upon the rocks of the glebe and elsewhere, are laid at rest in this safe and silent ground. A legend for one recording-stone thus commemorates a singular scene. The figurehead[28] of the brig Caledonia, of Arbroath, in Scotland, stands at the graves of her crew, in the churchyard of Morwenstow:—

Halfway down the principal pathway of the churchyard is a granite altar-tomb. It was raised, in all likelihood, for the old “month’s mind,” or “year’s mind,” of the dead: and it records a sad parochial history of the former time. It was about the middle of the sixteenth century that John Manning, a large landowner of Morwenstow, wooed and won Christiana Kempthorne, the vicar’s daughter. Her father was also a wealthy landlord of the parish in that day. Their marriage united in their own hands a broad estate, and in the midst of it the bridegroom built for his bride the manor-house of Stanbury, and labelled the door-heads and the hearths with the blended initials[29] of the married pair. It was a great and a joyous day when they were wed, and the bride[24] was led home amid all the solemn and festal observances of the time. There were liturgical benedictions of the mansion-house, the hearth, and the marriage-bed; for a large estate and a high place for their future lineage had been blended in the twain. Five months afterwards, on his homeward way from the hunting-field, John Manning was assailed by a mad bull, and gored to death not far from his home. His bride, maddened at the sight of her husband’s corpse, became prematurely a mother and died. They were laid, side by side, with their buried joys and blighted hopes, underneath this altar-tomb—whereon the simple legend records that there lie “John Manning and Christiana his wife, who died A.D. 1546, without living issue.”

When the vicar of the parish arrived, in the year 1836, he brought with him, among other carved oak furniture, a bedstead of Spanish chestnut, inlaid and adorned with ancient veneer: and it was set up, unwittingly, in a room of the vicarage which looked out upon the tombs. In the right-hand panel of the framework, at the head, was grooved in the name of John Manning; and in the place of the wife, the left hand, Christiana Manning, with their marriage date between. Nor was it discovered until afterwards that this was the very couch of wedded benediction, a relic of the great Stanbury marriage, which had been brought back and set up within sight of[25] the unconscious grave; and thus that the sole surviving records of the bridegroom and the bride stood side by side, the bedstead and the tomb, the first and the last scene of their early hope and their final rest.

Another and a lowlier grave bears on its recording-stone a broken snatch of antique rhythm, interwoven with modern verse. A young man[30] of this rural people, when he lay a-dying, found solace in his intervals of pain in the remembered echo of, it may be, some long-forgotten dirge; and he desired that the words which so haunted his memory might somehow or other be engraved on his stone. He died, and his parish priest fulfilled his desire by causing the following death-verse to be set up where he lies. We shall close our legends of Morwenstow with these simple lines.[31] The fragment which clung to the dying man’s memory was the first only of these lines:—

A MORALITY FROM THE ROCKY LAND

A lonely life for the dark and silent mole! Day is to her night. She glides along her narrow vaults, unconscious of the glad and glorious scenes of earth and air and sea. She was born, as it were, in a grave; and in one long, living sepulchre she dwells and dies. Is not existence to her a kind of doom? Wherefore is she thus a dark, sad exile from the blessed light of day? Hearken!

Here, in our bleak old Cornwall, the first mole was once a lady of the land. Her abode was in the far west, among the hills of Morwenna, beside the Severn Sea. She was the daughter of a lordly race, the only child of her mother; and the father of the house was dead: her name was Alice of the Combe. Fair was she and comely, tender and tall; and she stood upon the threshold of her youth. But most of all did men marvel at the glory of her large blue eyes. They were, to look upon, like the summer waters, when the sea is soft with light. They were to her mother a joy, and to the maiden herself, ah! benedicite, a pride.[28] She trusted in the loveliness of those eyes, and in her face and features and form; and so it was that the damsel was wont to pass the whole summer day in the choice of rich apparel and precious stones and gold. Howbeit this was one of the ancient and common usages of those old departed days. Now, in the fashion of her stateliness and in the hue and texture of her garments, there was none among the maidens of old Cornwall like Alice of the Combe. Men sought her far and near, but she was to them all, like a form of graven stone, careless and cold. Her soul was set upon a Granville’s love, fair Sir Beville of Stowe—the flower of the Cornish chivalry—that noble gentleman! That valorous knight! he was her star. And well might she wait upon his eyes; for he was the garland of the west. The loyal soldier of a Stuart king—he was that stately Granville who lived a hero’s life and died a warrior’s death! He was her star. Now there was signal made of banquet in the halls of Stowe, of wassail and dance. The messenger had sped, and Alice of the Combe would be there. Robes, precious and many, were unfolded from their rest, and the casket poured forth jewel and gem, that the maiden might stand before the knight victorious. It was the day—the hour—the time—her mother sate at her wheel by the hearth—the page waited in the hall—she came down in her loveliness, into the old oak room,[29] and stood before the mirrored glass—her robe was of woven velvet, rich and glossy and soft; jewels shone like stars in the midnight of her raven hair, and on her hand there gleamed afar off a bright and glorious ring! She stood—she gazed upon her own fair countenance and form, and worshipped! “Now all good angels succour thee, my Alice, and bend Sir Beville’s soul! Fain am I to greet thee wedded wife before I die! I do yearn to hold thy children on my knee! Often shall I pray to-night that the Granville heart may yield! Ay, thy victory shall be thy mother’s prayer.” “Prayer!” was the haughty answer: “now, with the eyes that I see in that glass, and with this vesture meet for a queen, I lack no trusting prayer!”[33] Saint Juliot shield us! Ah! words of fatal sound—there was a sudden shriek, a sob, a cry, and where was Alice of the Combe? Vanished, silent, gone! They had heard wild tones of mystic music in the air, there was a rush, a beam of light, and she was gone, and that for ever! East sought they her, and west, in northern paths and south; but she was never more seen in the lands. Her mother wept till she had not a tear left; none sought to comfort her, for it was vain. Moons waxed and waned, and the crones by the cottage[30] hearth had whiled away many a shadowy night with tales of Alice of the Combe. But at the last, as the gardener in the pleasaunce[34] leaned one day on his spade, he saw among the roses a small round hillock of earth, such as he had never seen before, and upon it something which shone. It was her ring! It was the very jewel she had worn the day she vanished out of sight! They looked earnestly upon it, and they saw within the border, for it was wide, the tracery of certain small fine runes in the ancient Cornish tongue, which said—

Then came the priest of the place of Morwenna, a grey and silent man! He had served long years at his lonely altar, a worn and solitary form. But he had been wise in language in his youth, and men said that he heard and understood voices in the air when spirits speak and glide. He read and he interpreted thus the legend on the ring,—

Now as on a day he uttered these words, in the pleasaunce, by the mound, on a sudden there was among the grass a low faint cry. They beheld, and oh, wondrous and strange! There was a small dark creature, clothed in a soft velvet skin in texture and in hue like the Lady Alice[31] her robe, and they saw, as it groped into the earth, that it moved along without eyes, in everlasting night! Then the ancient man wept, for he called to mind many things and saw what they meant; and he showed them how that this was the maiden, who had been visited with a doom for her Pride! Therefore her rich array had been changed into the skin of a creeping thing; and her large proud eyes were sealed up, and she herself had become

The First Mole of the Hillocks of Cornwall!

Ah, woe is me and well-a-day! that damsel so stately and fair, sweet Lady Alice of the Combe, should become, for a judgment, the dark mother of the Moles! Now take ye good heed, Cornish maidens, how ye put on vain apparel to win love! And cast down your eyes, all ye damsels of the west, and look meekly on the ground! Be ye ever good and gentle, tender and true; and when ye see your own image in the glass, and ye begin to be lifted up with the loveliness of that shadowy thing, call to mind the maiden of the vale of Morwenna, her noble eyes and comely countenance, her vesture of price, and the glittering ring! Set ye by the wheel as of old they sate, and when ye draw forth the lengthening wool, sing ye evermore and say—

Poor old Tristram Pentire! How he comes up before me as I pronounce his name! That light, active, half-stooping form, bent as though he had a brace of kegs upon his shoulders still; those thin, grey, rusty locks that fell upon a forehead seamed with the wrinkles of threescore years and five; the cunning glance that questioned in his eye, and that nose carried always at half-cock, with a red blaze along its ridge, scorched by the departing footstep of the fierce fiend Alcohol, when he fled before the reinforcements of the coast-guard.

He was the last of the smugglers; and when I took possession of my glebe, I hired him as my servant-of-all-work, or rather no-work, about the house, and there he rollicked away the last few years of his careless existence, in all the pomp and idleness of “The parson’s man.” He had taken a bold part in every landing on the coast, man and boy, full forty years; throughout which time all kinds of men had largely trusted him with their brandy and their lives, and true and faithful had he been to them, as sheath to steel.

Gradually he grew attached to me, and I could[33] but take an interest in him. I endeavoured to work some softening change in him, and to awaken a certain sense of the errors of his former life. Sometimes, as a sort of condescension on his part, he brought himself to concede and to acknowledge, in his own quaint, rambling way—

“Well, sir, I do think, when I come to look back, and to consider what lives we used to live,—drunk all night and idle abed all day, cursing, swearing, fighting, gambling, lying, and always prepared to shet [shoot] the gauger,—I do really believe, sir, we surely was in sin!”

But, whatever contrite admissions to this extent were extorted from old Tristram by misty glimpses of a moral sense and by his desire to gratify his master, there were two points on which he was inexorably firm. The one was, that it was a very guilty practice in the authorities to demand taxes for what he called run goods; and the other settled dogma of his creed was, that it never could be a sin to make away with an exciseman. Battles between Tristram and myself on these themes were frequent and fierce; but I am bound to confess that he always managed, somehow or other, to remain master of the field. Indeed, what Chancellor of the Exchequer could be prepared to encounter the triumphant demand with which Tristram smashed to atoms my suggestions of morality, political economy, and finance? He would listen with apparent patience[34] to all my solemn and secular pleas for the revenue, and then down he came upon me with the unanswerable argument—

“But why should the king tax good liquor? If they must have taxes, why can’t they tax something else?”

My efforts, however, to soften and remove his doctrinal prejudice as to the unimportance, in a moral point of view, of putting the officers of his Majesty’s revenue to death, were equally unavailing. Indeed, to my infinite chagrin, I found that I had lowered myself exceedingly in his estimation by what he called standing up for the exciseman.

“There had been divers passons,” he assured me, “in his time in the parish, and very learned clergy they were, and some very strict; and some would preach one doctrine and some another; and there was one that had very mean notions about running goods, and said ’twas a wrong thing to do; but even he, and the rest, never took part with the gauger—never! And besides,” said old Trim, with another demolishing appeal, “wasn’t the exciseman always ready to put us to death when he could?”

With such a theory it was not very astonishing—although it startled me at the time—that I was once suddenly assailed, in a pause of his spade, with the puzzling inquiry, “Can you tell me the reason, sir, that no grass will ever grow upon the grave of a man that is hanged unjustly?”

“No, indeed, Tristram. I never heard of the fact before.”

“Well, I thought every man know’d that from the Scripture: why, you can see it, sir, every Sabbath-day. That grave on the right hand of the path, as you go down to the porch-door, that heap of airth with no growth, not one blade of grass on it—that’s Will Pooly’s grave that was hanged unjustly.”

“Indeed! but how came such a shocking deed to be done?”

“Why, you see, sir, they got poor Will down to Bodmin, all among strangers, and there was bribery, and false swearing; and an unjust judge came down—and the jury all bad rascals, tin-and-copper-men—and so they all agreed together, and they hanged poor Will. But his friends begged the body and brought the corpse home here to his own parish; and they turfed the grave, and they sowed the grass twenty times over, but ’twas all no use, nothing would ever grow—he was hanged unjustly.”

“Well, but, Tristram, you have not told me all this while what this man Pooly was accused of: what had he done?”

“Done, sir! Done? Nothing whatever but killed the exciseman!”

The glee, the chuckle, the cunning glance, were inimitably characteristic of the hardened old smuggler; and then down went the spade with[36] a plunge of defiance, and as I turned away, a snatch of his favourite song came carolling after me like the ballad of a victory:—

Among the “king’s men,” whose achievements haunted the old man’s memory with a sense of mingled terror and dislike, a certain Parminter and his dog occupied a principal place. This officer appeared to have been a kind of Frank Kennedy[36] in his way, and to have chosen for his watchword the old Irish signal, “Dare!”

“Sir,” said old Tristram once, with a burst of indignant wrath—“Sir, that villain Parminter and[37] his dog murdered with their shetting-irons no less than seven of our people at divers times, and they peacefully at work in their calling all the while!”

I found on further inquiry that this man Parminter was a bold and determined officer, whom no threats could deter and no money bribe. He always went armed to the teeth, and was followed by a large, fierce, and dauntless dog, which he had thought fit to call Satan. This animal he had trained to carry in his mouth a carbine or a loaded club, which, at a signal from his master, Satan brought to the rescue. “Ay, they was bold audacious rascals—that Parminter and his dog—but he went rather too far one day, as I suppose,” was old Tristram’s chuckling remark, as he leaned on his spade, and I stood by.

“Did he, Trim; in what way?”

“Why, sir, the case was this. Our people had a landing down at Melhuach,[37] in Johnnie Mathey’s hole, and Parminter and his dog found it out. So they got into the cave at ebb tide, and laid in wait, and when the first boat-load came ashore, just as the keel took the ground, down storms Parminter, shouting for Satan to follow. The dog knew better, and held back, they said, for the first time in all his life: so in leaps Parminter smash into the boat alone, with his cutlass drawn;[38] but” (with a kind of inward ecstasy) “he didn’t do much harm to the boat’s crew——”

“Because,” as I interposed, “they took him off to their ship?”

“No, not they; not a bit of it. Their blood was up, poor fellows; so they just pulled Parminter down in the boat, and chopped off his head on the gunwale!”

The exclamation of horror with which I received this recital elicited no kind of sympathy from Tristram. He went on quietly with his work, merely moralising thus—“Ay, better Parminter and his dog had gone now and then to the Gauger’s Pocket at Tidnacombe[38] Cross, and held their peace—better far.”

The term “The Gauger’s Pocket,” in old Tristram’s phraseology, had no kind of reference to any place of deposit in the apparel of the exciseman, but to a certain large grey rock, which stands upon a neighbouring moorland, not far from the cliffs which overhang the sea. It bears to this day, among the parish people, the name of the Witan-stone—that is to say, in the language of our forefathers, the Rock of Wisdom; because it was one of the places of usual assemblage for the Grey Eldermen of British or of Saxon times—a sort of speaker’s chair or woolsack in the local parliaments. It was, moreover, there is no doubt, one of the natural altars of the old religion;[39] and, as such, it is greeted with a fond and legendary reverence still. Hither Trim guided me one day, to show, as he told me, “the great rock set up by the giants, so they said—long, long ago, before there was any bad laws such as they make now.” It was indeed a wild, strange, striking scene; and one to lift and fill, and, moreover, to subdue the thoughtful mind. Around was the wild, half-cultured moor; yonder, within reach of sight and ear, that boundless, breathing sea, with that shout of waters which came up ever and anon to recall the strong metre of the Greek[39]—

And there, before me, stood the tall, vast, solemn stone: grey and awful with the myriad memorials of ancient ages, when the white fathers bowed around the rocks and worshipped!

“And now, sir,” clashed in a shrill, sharp voice, “let me show you the wonderfullest thing in all the place, and that is, the Gauger’s Pocket.”

Accordingly I followed my guide, for it seems “I had a dream that was not all a dream,” as he led the way to the back of the Witan-stone; and[40] there, grown over with moss and lichen, with a movable slice of rock to conceal its mouth, old Tristram pointed out, triumphantly, a dry and secret crevice, almost an arm’s-length deep. “There, sir,” said he, with a joyous twinkle in his eye,—“there have I dropped a little bag of gold, many and many a time, when our people wanted to have the shore quiet and to keep the exciseman out of the way of trouble; and there he would go, if so be he was a reasonable officer, and the byword used to be, when ’twas all right, one of us would go and meet him, and then say, ‘Sir, your pocket is unbuttoned;’ and he would smile and answer, ‘Ay, ay! but never mind, my man, my money’s safe enough;’ and thereby we knew that he was a just man, and satisfied, and that the boats could take the roller in peace; and that was the very way, sir, it came to pass that this crack in the stone was called for evermore ‘The Gauger’s Pocket.’”

The life and adventures of the Cornish clergy during the eighteenth century would form a graphic volume of ecclesiastical lore. Afar off from the din of the noisy world, almost unconscious of the badge-words High Church and Low Church, they dwelt in their quaint grey vicarages by the churchyard wall, the saddened and unsympathising witnesses of those wild, fierce usages of the west which they were utterly powerless to control. The glebe whereon I write has been the scene of many an unavailing contest in the cause of morality between the clergyman and his flock. One aged parishioner recalls and relates the run—that is, the rescue—of a cargo of kegs underneath the benches and in the tower-stairs of the church. “We bribed Tom Hockaday, the sexton,” so the legend ran, “and we had the goods safe in the seats by Saturday night. The parson did wonder at the large congregation, for divers of them were not regular church-goers at other times; and if he had known what was going on he could not have preached a more[42] suitable discourse, for it was, ‘Be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess.’ One of his best sermons; but there it did not touch us, you see, for we never tasted anything but brandy or gin. Ah! he was a dear old man our parson, mild as milk; nothing ever put him out. Once I mind, in the middle of morning prayer, there was a buzz down by the porch, and the folks began to get up and go out of church one by one. At last there was hardly three left. So the parson shut the book and took off his surplice, and he said to the clerk, ‘There is surely something amiss.’ And so there certainly was; for when we came out on the cliff there was a king’s cutter in chase of our vessel, the Black Prince, close under the land, and there was our departed congregation looking on. Well, at last Whorwell, who commanded our trader, ran for the Gullrock (where it was certain death for anything to follow him), and the revenue commander sheered away to save his ship. Then off went our hats, and we gave Whorwell three cheers. So, when there was a little peace, the parson said to us all, ‘And now, my friends, let us return and proceed with divine service.’ We did return; and it was surprising, after all that bustle and uproar, to hear how Parson Trenowth went on, just as nothing had come to pass: ‘Here beginneth the Second Lesson.’” But on another occasion, the equanimity and forbearance of the parson were sorely tired. He presided, as the[43] custom was, at a parish feast, in cassock and bands, and had, with his white hair and venerable countenance, quite an apostolic aspect and mien. On a sudden, a busy whisper among the farmers at the lower end of the table attracted his notice, interspersed as it was by sundry nods and glances towards himself. At last one bolder than the rest addressed him, and said that they had a great wish to ask his reverence a question if he would kindly grant them a reply: it was on a religious subject that they had dispute, he said. The bland old man assured them of his readiness to yield them any information or answer in his power.

“But what was the point in debate?”

“Why, sir, we wish to be informed if there were not sins which God Almighty would never forgive?”

Surprised and somewhat shocked, he told them “that he trusted there were no transgressions, common to themselves, but, if repented of and abjured, they might clearly hope to be forgiven.” But, with a natural curiosity, he inquired what kind of iniquities they had discussed as too vile to look for pardon. “Why, sir,” replied their spokesman, “we thought that if a man should find out where run goods was deposited and should inform the gauger, that such a villain was too bad for mercy.”

How widely the doctrinal discussions of those[44] days differed from our own! Let us not, however, suppose that all the clergy were as gentle and unobtrusive as Parson Trenowth. A tale is told of an adjacent parish, situate also on the sea-shore, of a more stirring kind. It was full sea in the evening of an autumn day when a traveller arrived where the road ran along by a sandy beach, just above high-water mark. The stranger, who was a native of some inland town, and utterly unacquainted with Cornwall and its ways, had reached the brink of the tide just as a “landing” was coming off. It was a scene not only to instruct a townsman but also to dazzle and surprise. At sea, just beyond the billows, lay the vessel well moored with anchors at stem and stern. Between the ship and the shore boats laden to the gunwale passed to and fro. Crowds assembled on the beach to help the cargo ashore. On the one hand a boisterous group surrounded a keg with the head knocked in, for simplicity of access to the good cognac, into which they dipped whatsoever vessel came first to hand: one man had filled his shoe. On the other side they fought and wrestled, cursed and swore. Horrified at what he saw, the stranger lost all self-command, and, oblivious of personal danger, he began to shout, “What a horrible sight! Have you no shame? Is there no magistrate at hand? Cannot any justice of the peace be found in this fearful country?”

“No—thanks be to God,” answered a hoarse, gruff voice; “none within eight miles.”

“Well, then,” screamed the stranger, “is there no clergyman hereabout? Does no minister of the parish live among you on this coast?”

“Ay! to be sure there is,” said the same deep voice.

“Well, how far off does he live? Where is he?”

“That’s he yonder, sir, with the lanthorn.” And sure enough there he stood, on a rock, and poured, with pastoral diligence, the light of other days on a busy congregation.

It has frequently occurred to my thoughts that the events which have befallen me since my collation to this wild and remote vicarage, on the shore of the billowy Atlantic sea, might not be without interest to the reader of a more refined and civilised region. When I was collated to the incumbency in 18—,[42] I found myself the first resident vicar for more than a century. My parish was a domain of about seven thousand acres, bounded on the landward border by the course of a curving river,[43] which had its source with a sister stream[44] in a moorland spring within my territory, and, flowing southward, divided two counties in its descent to the sea. My seaward boundary was a stretch of bold and rocky shore, an interchange of lofty headland and deep and sudden gorge, the cliffs varying from three hundred to four hundred and fifty feet of perpendicular or gradual height, and the valleys gushing with torrents, which bounded rejoicingly[47] towards the sea, and leaped at last, amid a cloud of spray, into the waters. So stern and pitiless is this iron-bound coast, that within the memory of one man upwards of eighty wrecks have been counted within a reach of fifteen miles, with only here and there the rescue of a living man. My people were a mixed multitude of smugglers, wreckers, and dissenters of various hue. A few simple-hearted farmers had clung to the grey old sanctuary of the church and the tower that looked along the sea; but the bulk of the people, in the absence of a resident vicar, had become the followers of the great preacher[45] of the last century who came down into Cornwall and persuaded the people to alter their sins. I was assured, soon after my arrival, by one of his disciples, who led the foray among my flock, that my “parish was so rich in resources for his benefit, that he called it, sir, the garden of our circuit.” The church stood on the glebe, and close by the sea. It was an old Saxon station, with additions of Norman structure, and the total building, although of gradual erection, had been completed and consecrated before the middle of the fifteenth century. The vicarage, built by myself, stood, as it were, beneath the sheltering shadow of the walls and tower. My land extended thence to the shore. Here, like the Kenite,[46] I had “built my nest upon the rock,” and here my days were to glide away,[48] afar from the noise and bustle of the world, in that which is perhaps the most thankless office in every generation, the effort to do good against their will to our fellow-men. Mine was a perilous warfare. If I had not, like the apostle, to “fight with wild beasts at Ephesus,” I had to soothe the wrecker, to persuade the smuggler, and to “handle serpents,” in my intercourse with adversaries of many a kind. Thank God! the promises which the clergy inherit from their Founder cannot fail to be fulfilled. It was never prophesied that they should be popular, or wealthy, or successful among men; but only that they “should endure to the end,” that “their generation should never pass away.” Well has this word been kept!

Among my parishioners there were certain individuals who might be termed representative men,—quaint and original characters, who embodied in their own lives the traditions and the usages of the parish. One of these had been for full forty years a wrecker—that is to say, a watcher of the sea and rocks for flotsam and jetsam, and other unconsidered trifles which the waves might turn up to reward the zeal and vigilance of a patient man. His name was Peter Burrow, a man of harmless and desultory life, and by no means identified with the cruel and covetous natives of the strand, with whom it was a matter of pastime to lure a vessel ashore by a treacherous[49] light, or to withhold succour from the seaman struggling with the sea. He was the companion of many of my walks, and the witness with myself of more than one thrilling and perilous scene. Another of my parish notorieties, the hero of contraband adventure, and agent for sale of smuggled cargoes in bygone times, was Tristram Pentire,[47] a name known to the readers of these pages. With a merry twinkle of the eye, and in a sharp and ringing tone, it was old Tristram’s usage to recount for my instruction such tales of wild adventure and of “derring-do” as would make the foot of an exciseman falter and his cheek turn pale. But both these cronies of mine were men devoid of guile, and in their most reckless of escapades innocent of mischievous harm. It was not long after my arrival in my new abode that I was plunged all at once into the midst of a fearful scene of the terrors of the sea. About daybreak of an autumn day I was aroused by a knock at my bedroom-door; it was followed by the agitated voice of a boy, a member of my household, “Oh, sir, there are dead men on vicarage rocks!”

In a moment I was up, and in my dressing-gown and slippers rushed out. There stood my lad, weeping bitterly, and holding out to me in his trembling hands a tortoise alive. I found afterwards that he had grasped it on the beach,[50] and brought it in his hand as a strange and marvellous arrival from the waves, but in utter ignorance of what it might be. I ran across my glebe, a quarter of a mile, to the cliffs, and down a frightful descent of three hundred feet to the beach. It was indeed a scene to be looked on once only in a human life. On a ridge of rock, just left bare by the falling tide, stood a man, my own servant; he had come out to see my flock of ewes, and had found the awful wreck. There he stood, with two dead sailors at his feet, whom he had just drawn out of the water stiff and stark. The bay was tossing and seething with a tangled mass of rigging, sails, and broken fragments of a ship; the billows rolled up yellow with corn, for the cargo of the vessel had been foreign wheat; and ever and anon there came up out of the water, as though stretched out with life, a human hand and arm. It was the corpse of another sailor drifting out to sea. “Is there no one alive?” was my first question to my man. “I think there is, sir,” he said, “for just now I thought I heard a cry.” I made haste in the direction he pointed out, and, on turning a rock, just where a brook of fresh water fell towards the sea, there lay the body of a man in a seaman’s garb. He had reached the water faint with thirst, but was too much exhausted to swallow or drink. He opened his eyes at our voices, and as he saw me leaning over him in[51] my cassock-shaped dressing-gown, he sobbed, with a piteous cry, “O mon père, mon père!” Gradually he revived, and when he had fully come to himself with the help of cordials and food, we gathered from him the mournful tale of his vessel and her wreck. He was a Jersey man by birth, and had been shipped at Malta, on the homeward voyage of the vessel from the port of Odessa with corn. I had sent in for brandy, and was pouring it down his throat, when my parishioner, Peter Burrow, arrived. He assisted, at my request, in the charitable office of restoring the exhausted stranger; but when he was refreshed and could stand upon his feet, I remarked that Peter did not seem so elated as in common decency I expected he would be. The reason soon transpired. Taking me aside, he whispered in my ear, “Now, sir, I beg your pardon, but if you’ll take my advice, now that man is come to himself, if I were you I would let him go his way wherever he will. If you take him into your house, he’ll surely do you some harm.” Seeing my surprise, he went on to explain, “You don’t know, sir,” he said, “the saying on our coast—

There was one Coppinger[48] cast ashore from a brig that struck up at Hartland, on the Point.[52] Farmer Hamlyn dragged him out of the water and took him home, and was very kind to him. Lord, sir! he never would leave the house again! He lived upon the folks a whole year, and at last, lo and behold! he married the farmer’s daughter Elizabeth, and spent all her fortin rollicking and racketing, till at last he would tie her to the bedpost and flog her till her father would come down with more money. The old man used to say he wished he’d let Coppinger lie where he was in the waves, and never laid a finger on him to save his life. Ay, and divers more I’ve heerd of that never brought no good to they that saved them.”

“And did you ever yourself, Peter,” said I, “being, as you have told me, a wrecker so many years—did you ever see a poor fellow clambering up the rock where you stood, and just able to reach your foot or hand, did you ever shove him back into the sea to be drowned?”

“No, sir, I declare I never did. And I do believe, sir, if I ever had done such a thing, and given so much as one push to a man in such a case, I think verily that afterwards I should have been troubled and uncomfortable in my mind.”

“Well, notwithstanding your doctrine, Peter,” said I, “we will take charge of this poor fellow; so do you lead him into the vicarage and order a bed for him, and wait till I come in.”

I returned to the scene of death and danger, where my man awaited me. He had found, in addition to the two corpses, another dead body jammed under a rock. By this time a crowd of people had arrived from the land, and at my request they began to search anxiously for the dead. It was, indeed, a terrible scene. The vessel, a brig of five hundred tons, had struck, as we afterwards found, at three o’clock that morning, and by the time the wreck was discovered she had been shattered into broken pieces by the fury of the sea. The rocks and the water bristled with fragments of mast and spar and rent timbers; the cordage lay about in tangled masses. The rollers tumbled in volumes of corn, the wheaten cargo; and amidst it all the bodies of the helpless dead—that a few brief hours before had walked the deck the stalwart masters of their ship—turned their poor disfigured faces toward the sky, pleading for sepulture. We made a temporary bier of the broken planks, and laid thereon the corpses, decently arranged. As the vicar, I led the way, and my people followed with ready zeal as bearers, and in sad procession we carried our dead up the steep cliff, by a difficult path, to await, in a room at my vicarage which I allotted them, the inquest. The ship and her cargo were, as to any tangible value, utterly lost.

The people of the shore, after having done their best to search for survivors and to discover[54] the lost bodies, gathered up fragments of the wreck for fuel, and shouldered them away,—not perhaps a lawful spoil, but a venal transgression when compared with the remembered cruelties of Cornish wreckers. Then ensued my interview with the rescued man. His name was Le Daine. I found him refreshed, and collected, and grateful. He told me his Tale of the Sea. The captain and all the crew but himself were from Arbroath, in Scotland. To that harbour also the vessel belonged. She had been away on a two years’ voyage, employed in the Mediterranean trade. She had loaded last at Odessa. She touched at Malta, and there Le Daine, who had been sick in the hospital, but recovered, had joined her. There also the captain had engaged a Portuguese cook, and to this man, as one link in a chain of causes, the loss of the vessel might be ascribed. He had been wounded in a street-quarrel the night before the vessel sailed from Malta, and lay disabled and useless in his cabin throughout the homeward voyage. At Falmouth whither they were bound for orders, the cook died. The captain and all the crew, except the cabin-boy, went ashore to attend the funeral. During their absence the boy, handling in his curiosity the barometer, had broken the tube, and the whole of the quicksilver had run out. Had this instrument, the pulse of the storm, been preserved, the crew would have received[55] warning of the sudden and unexpected hurricane, and might have stood out to sea. Whereas they were caught in the chops of the Channel, and thus, by this small incident, the vessel and the mariners found their fate on the rocks of a remote headland in my lonely parish. I caused Le Daine to relate in detail the closing events.

“We received orders,” he said, “at Falmouth to make for Gloucester to discharge. The captain, and mate, and another of the crew, were to be married on their return to their native town. They wrote, therefore, to Arbroath from Falmouth, to announce their safe arrival there from their two years’ voyage, their intended course to Gloucester, and their hope in about a week to arrive at Arbroath for welcome there.”

But in a day or two after this joyful letter, there arrived in Arbroath a leaf torn out of my pocket-book, and addressed “To the Owners of the Vessel,” the Caledonia of Arbroath, with the brief and thrilling tidings, written by myself in pencil, that I wrote among the fragments of their wrecked vessel, and that the whole crew, except one man, were lost “upon my rocks.” My note spread a general dismay in Arbroath, for the crew, from the clannish relationship among the Scots, were connected with a large number of the inhabitants. But to return to the touching details of Le Daine.

“We rounded the Land’s End,” he said, “that[56] night all well, and came up Channel with a fair wind. The captain turned in. It was my watch. All at once, about nine at night, it began to blow in one moment as if the storm burst out by signal; the wind went mad; our canvas burst in bits. We reeved fresh sails; they went also. At last we were under bare poles. The captain had turned out when the storm began. He sent me forward to look out for Lundy Light. I saw your cliff.” (This was a bluff and broken headland just by the southern boundary of my own glebe.) “I sung out, ‘Land!’ I had hardly done so when she struck with a blow, and stuck fast. Then the captain sung out, ‘All hands to the maintop!’ and we all went up. The captain folded his arms, and stood by, silent.”

Here I asked him, anxious to know how they expressed themselves at such a time, “But what was said afterwards, Le Daine?”

“Not one word, sir; only once, when the long-boat went over, I said to the skipper, ‘Sir, the boat is gone!’ But he made no answer.”

How accurate was Byron’s painting—

“At last there came on a dreadful wave, mast-top high, and away went the mast by the board, and we with it, into the sea. I gave myself up. I was the only man on the ship that could not swim, so where I fell in the water there I lay. I[57] felt the waves beat me and send me on. At last there was a rock under my hand. I clung on. Just then I saw Alick Kant, one of our crew, swimming past. I saw him lay his hand on a rock, and I sung out, ‘Hold on, Alick!’ but a wave rolled and swept him away, and I never saw his face more. I was beaten onward and onward among the rocks and the tide, and at last I felt the ground with my feet. I scrambled on. I saw the cliff, steep and dark, above my head. I climbed up until I reached a kind of platform with grass, and there I fell down flat upon my face, and either I fainted away or I fell asleep. There I lay a long time, and when I awoke it was just the break of day. There was a little yellow flower just under my head, and when I saw that I knew I was on dry land.” This was a plant of the bird’s-foot clover, called in old times Our Lady’s Finger. He went on: “I could see no house or sign of people, and the country looked to me like some wild and desert island. At last I felt very thirsty, and I tried to get down towards a valley where I thought I should find water; but before I could reach it I fell and grew faint again, and there, thank God, sir, you found me.”

Such was Le Daine’s sad and simple story, and no one could listen unmoved or without a strong feeling of interest and compassion for the poor solitary survivor of his shipmates and crew. The coroner arrived, held his ’quest, and the[58] usual verdict of “Wrecked and cast ashore” empowered me to inter the dead sailors, found and future, from the same vessel, with the service in the Prayer-book for the Burial of the Dead. This decency of sepulture is the result of a somewhat recent statute, passed in the reign of George III. Before that time it was the common usage of the coast to dig, just above high-water mark, a pit on the shore, and therein to cast, without inquest or religious rite, the carcasses of shipwrecked men. My first funeral of these lost mariners was a touching and striking scene. The three bodies first found were buried at the same time. Behind the coffins, as they were solemnly borne along the aisle, walked the solitary mourner, Le Daine, weeping bitterly and aloud. Other eyes were moist, for who could hear unsoftened the greeting of the Church to these strangers from the sea, and the “touch that makes the whole earth kin,” in the hope we breathed that we, too, might one day “rest as these our brethren did”? It was well-nigh too much for those who served that day. Nor was the interest subdued when, on the Sunday after the wreck, at the appointed place in the service, just before the General Thanksgiving, Le Daine rose up from his place, approached the altar, and uttered, in an audible but broken voice, his thanksgiving for his singular and safe deliverance from the perils of the sea.

The text of the sermon that day demands its history. Some time before, a vessel, the Hero of Liverpool, was seen in distress, in the offing of a neighbouring harbour, during a storm. The crew, mistaking a signal from the beach, betook themselves to their boat. It foundered, and the whole ship’s company, twelve in number, were drowned in sight of the shore. But the stout ship held together, and drifted on to the land so unshattered by the sea that the coast-guard, who went immediately on board, found the fire burning in the cabin. When the vessel came to be examined, they found in one of the berths a Bible, and between its leaves a sheet of paper, whereon some recent hand had transcribed verses the twenty-first, twenty-second, and twenty-third of the thirty-third chapter of Isaiah. The same hand had also marked the passage with a line of ink along the margin. The name of the owner of the book was also found inscribed on the fly-leaf. He was a youth of eighteen years of age, the son of a widow, and a statement under his name recorded that the Bible was “a reward for his good conduct in a Sunday-school.” This text, so identified and enforced by a hand that soon after grew cold, appeared strangely and strikingly adapted to the funeral of shipwrecked men; and it was therefore chosen as the theme for our solemn day. The very hearts of the people seemed hushed to hear it, and every eye was[60] turned towards Le Daine, who bowed his head upon his hands and wept. These are the words: “But there the glorious Lord will be unto us a place of broad rivers and streams; wherein shall go no galley with oars, neither shall gallant ship pass thereby. For the Lord is our judge, the Lord is our lawgiver, the Lord is our king; He will save us. The tacklings are loosed; they could not well strengthen their mast, they could not spread the sail: then is the prey of a great spoil divided; the lame take the prey.” Shall I be forgiven for the vaunt, if I declare that there was not literally a single face that day unmoistened and unmoved? Few, indeed, could have borne, without deep emotion, to see and hear Le Daine. He remained as my guest six weeks, and during the whole of this time we sought diligently, and at last we found the whole crew, nine in number. They were discovered, some under rocks, jammed in by the force of the water, so that it took sometimes several ebb-tides, and the strength of many hands, to extricate the corpses. The captain I came upon myself lying placidly upon his back, with his arms folded in the very gesture which Le Daine had described as he stood amid the crew on the maintop. The hand of the spoiler was about to assail him when I suddenly appeared, so that I rescued him untouched. Each hand grasped a small pouch or bag. One contained his pistols; the other held two little log-[61]reckoners[49] of brass; so that his last thoughts were full of duty to his owners and his ship, and his latest efforts for rescue and defence. He had been manifestly lifted by a billow and hurled against a rock, and so slain; for the victims of our cruel sea are seldom drowned, but beaten to death by violence and the wrath of the billows. We gathered together one poor fellow in five parts; his limbs had been wrenched off, and his body rent. During our search for his remains, a man came up to me with something in his hand, inquiring, “Can you tell me, sir, what is this? Is it a part of a man?” It was the mangled seaman’s heart, and we restored it reverently to its place, where it had once beat high with life and courage, with thrilling hope and sickening fear. Two or three of the dead were not discovered for four or five weeks after the wreck, and these had become so loathsome from decay, that it was at peril of health and life to perform the last duties we owe to our brother-men. But hearts and hands were found for the work, and at last the good ship’s company—captain, mate, and crew—were laid at rest, side by side, beneath our churchyard trees. Groups of grateful letters from Arbroath[50] are to this day among the most cherished[62] memorials of my escritoire. Some, written by the friends of the dead, are marvellous proofs of the good feeling and educated ability of the Scottish people. One from a father breaks off in irrepressible pathos, with a burst of “O my son! my son!” We placed at the foot of the captain’s grave the figurehead[51] of his vessel. It is a carved image, life-size, of his native Caledonia, in the garb of her country, with sword and shield.