CANDY! | Send $1, $2, $3, or $5 for retail box by Express of the best Candies in America, put up in elegant boxes, and strictly pure. Suitable for presents. Express charges light. Refers to all Chicago. Try it once.

Address C. F. GUNTHER, Confectioner, Chicago. |

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Breakfast Cocoa. Warranted absolutely pure Cocoa, from which the excess of Oil has been removed. It has three times the strength of Cocoa mixed with Starch, Arrowroot or Sugar, and is therefore far more economical, costing less than one cent a cup. It is delicious, nourishing, strengthening, easily digested, and admirably adapted for invalids as well as for persons in health.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Vanilla Chocolate, Like all our chocolates, is prepared

with the greatest care, and

consists of a superior quality of

cocoa and sugar, flavored with

pure vanilla bean. Served as a

drink, or eaten dry as confectionery,

it is a delicious article,

and is highly recommended by

tourists.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

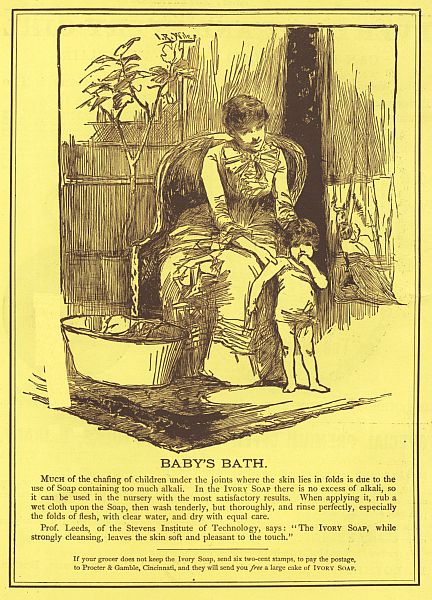

A Beautiful Imported Birthday Card sent

to any baby whose mother will send us the

names of two or more other babies, and their

parents' addresses. Also a handsome Diamond

Dye Sample Card to the mother and

much valuable information. Wells,

Richardson & Co., Burlington, Vt.

BEFORE YOU BUY A BICYCLE

Of any kind, send stamp to A. W. GUMP.,

Dayton, Ohio, for large Illustrated Price

List of New and Second-Hand Machines.

Second-hand BICYCLES taken in exchange. |

Recognizing the superior excellence of the St. Louis Magazine, we have arranged to furnish it in connection with The Pansy at the low price of $1.75 a year for both publications, the Magazine, under its enlarged and improved condition, being $1.50 a year alone. Those wishing to see a sample copy of the Magazine before subscribing should send 10 cents to St. Louis Magazine, 213 North Eighth street, St. Louis, Mo., or send $1.75 net either to The Pansy or Magazine, and receive both for one year. Sample copy and a beautiful set of gold-colored Picture Cards sent for Ten Cents.

| HEADQUARTERS | FOR LADIES' FANCY WORK. |

We will send you our 15-c. Fancy Work Book (new 1886 edition), for 3 two-cent stamps. A Felt Tidy and Imported Silk to work it, for 20 cents. A Fringed linen Tidy and Embroidery Cotton to work it, for 16c., Florence "Waste" Embroidery Silk, 25c. per package. Illustrated Circulars Free. J. F. Ingalls, Lynn, Mass.

The St. Louis Magazine, edited by Alexander N. de Menil, now in its fifteenth year, is brilliantly illustrated, purely Western in make-up, replete with stories, poems, timely reading and humor. Sample copy and a set of gold-colored picture cards sent for ten cents. Address T. J. GILMORE, 213 North Eighth Street, St. Louis. The Pansy and St. Louis Magazine sent one year for $1.75.

YOU CAN DYE | ANYTHING ANY COLOR |

The British Government awarded a Medal for this article October, 1885.

The WIDE AWAKE one year, and the Detroit Weekly Free Press until Dec. 31, 1886, will be mailed on receipt of $3.60 for the two.

The Detroit Free Press is one of the best, most interesting and purest family papers published. It should be in thousands of homes where it is not now taken. No family will regret having subscribed for this choicest of papers for the household.

A combination that will afford instructive and entertaining reading to a whole household for a year.

It is a very fine lithographic portrait, size 8 inches by 10 inches. We will send two of the pictures to any subscriber sending us one new subscriber before May 1st, with $1.00 for the same. Address all the subscriptions to

"The very last Sabbath I was in church," said she to Doctor Wheeler, "Mr. Lewis said in his sermon, that even our afflictions had a blessing wrapped up in them. But I do not believe there is one inside this trouble. I can't conceive of any good that can possibly come out of it all!"

"Well, I don't know," replied Doctor Wheeler, "I should never have conceived of anything like that statue, yet it was inside the marble all the time, and plainly discerned by the eye of the sculptor. There are things in the spiritual world which we cannot conceive until they are revealed to us."

Poor Mrs. Hamlin shook her head doubtfully. She was very sure no good could grow out of this trial. Doctor Wheeler was a sweet-voiced little woman who looked upon the bright side of things and whom the children loved; they were very sorry for their little friend across the street who had the fever and whose father insisted upon sending for that gruff old Doctor Smith, who never had a smile for children.

"Your children have good constitutions and you have good nurses, I see no reason why they should not pull through easily," said Doctor Wheeler when Mr. Hamlin asked her opinion as to the prospects of the recovery of his little folks. "But what about that oldest boy of yours? Does he not have an Easter vacation?"

"Yes; and I suppose he ought not to come home?"

"Most certainly not! It will not be safe for several weeks; he must be kept away from this vicinity, though I hope the disease will not spread. You should send word for him to remain at the school through the vacation."

It was a very sober face indeed that presented itself at Doctor Brown's study door, a day or two after this conversation took place.

Doctor Brown was the principal of Howland Hall School for boys, and was the right man in the right place.

"What is it, Fred?" he asked kindly. "Come in and let me hear about it."

"It is this," replied Fred Hamlin, handing the Doctor his father's letter.

"Ah! Well, my boy, it might be worse news. You understand, the little folks at home are all on the high road to recovery, and it is on your account that you are not to go home."

"I know; but it will be dreadful lonesome here with the boys all away."

"That is so; and what will make it worse is, that we have planned a little trip which will take us all away excepting Mr. and Mrs. Jennings. I am afraid it will be rather doleful for you alone in this great house; but that will be better than the scarlet fever. Eh?"

Fred turned away in a very disconsolate frame of mind. The Easter vacation to which he had been looking forward was likely to be anything but pleasant. Now Fred Hamlin was by no means a model boy, and matters did not always go smoothly with him at home. His own mother died when he was a baby, and his grandmother had taken charge of him until Fred was ten years old. Then she too died, and the boy was taken home by his father. The second mother tried earnestly to win the boy's heart, but seeds of suspicion and jealousy had been dropped into the young mind, and he refused to be won. After three years of trial Mr. Hamlin concluded to send Fred to school. Doctor Brown had the reputation of being a strict disciplinarian, and Mr. Hamlin hoped much as a result of school discipline. But Watt Vinton, Fred's room-mate, knew very well that any such expectations were not likely to be realized. I cannot tell you of all the ways in which Fred contrived to make himself disagreeable to his quiet and gentlemanly companion. But so well did he succeed, that Watt, sometimes, with his face buried in the pillow, would whisper just to himself, "He is the hatefulest, meanest, crossest fellow I ever saw! I don't believe he has a particle of respect or love for anybody on earth!" Now perhaps you will almost doubt me when I tell you that the pillow was Watt's only confident. He never[139] breathed a word of his troubles to a single person. There were several reasons for this reticence. Watt was an orphan, and had learned to keep his troubles to himself. He was too proud to complain; he had a notion that it would be more manly to endure annoyances than to make a fuss over them. It was only when he got out of patience that he took his troubles to his friend the pillow. This will explain why Watt Vinton frowned a little over a letter which he received a few days before the Easter vacation, and why he carried it in his pocket a whole day before coming to a decision in regard to one of its propositions. The letter was from his cousin, May Vinton, and here is one sentence from it: "Now that it is settled that you are to spend your vacation here, would you like to bring a boy with you? If there is somebody who cannot go home, or who needs a chance, whom you would like to bring, you may invite him to be your guest for the week."

It took Watt a whole day to make up his mind that he could do it. But at the end of the twenty-four hours he wrote to his cousin, "I am going to bring my chum."

Well, what came of it all—the scarlet fever, Mrs. Hamlin's trouble, Fred's disappointment, and Watt's sacrifice?

Do you suppose God knew that May Vinton could reach that wayward boy's heart, and help him to a better life, and so planned all this to bring about the meeting? Do you not suppose that he knew that Watt's sacrifice would make him stronger and better? It was a day or two after the boys reached the beautiful home of the Vintons that Fred sat in May's lovely room, chatting confidentially with her. Watt had been called to the library by his guardian, and the boy was left alone with the loveliest young lady he had ever met. Just how it was I do not know; Fred himself does not know, but it was not long before he was telling this new and it seemed to him first friend he had ever known, all his story; how nobody loved him, and how he hated everybody; how dreadful it was to have a stepmother, and a great deal of nonsense which to the mistaken and misunderstood boy seemed very solemn truth.

I have not space in which to tell you how May Vinton helped him to a better understanding of himself, and of his position. But at the close of one of the many conversations which they had during Fred's visit, he said:

"I see how it is! I have been more to blame than anybody else. But the boys have got so used to expecting hatefulness from me, they would never understand if I tried to do differently."

"Never is a long time," said Miss Vinton.

One day Watt said to his cousin, "What have you done to Fred? He is so different here!"

"Perhaps more will come of your sacrifice than you expected," replied May quietly.

"What do you know about a sacrifice?" asked Watt quickly.

A smile was her only reply.

More did grow out of it all than anyone would have suspected. May Vinton's seed-sowing was on good ground. By her love and sympathy she had softened the soil, and the heart of the friendless boy opened to the refining and elevating influences she threw around him, and a month later Watt wrote, "Fred is just as different as you can think. The boys all like him now."

So they read in the book in the law of God distinctly, and gave the sense, and caused them to understand the reading.

So will I go in unto the king, which is not according to the law; and if I perish, I perish.

Behold, I will send my messenger, and he shall prepare the way before me.

Thy throne, O God, is forever and ever; the sceptre of thy kingdom is a right sceptre.

"Why, Grandma?" and, "O Grandma, tell us what you see!" and, "Grandma, show us the picture, won't you?" this was the chorus which greeted her laugh.

"Dear me! It isn't much of a story, but I remember it as well as though it happened yesterday. I was a little thing, not much over four, I should think. It was a warm Sunday, and first[140] I see myself in church. I was in my best dress, a lovely white slip with blue stars all over it."

"Grandma, who ever heard of blue stars?" This from Marion.

"I did, child, many a time when I was of your age, and younger; it used to be the favorite print. Mine was very pretty and was made in the latest fashion—a yoke in the neck, and a long full skirt. I had slippers, too, with straps which went around my ankle and buttoned at the side; those slippers had just come in, and I felt very fine in them. I had a shirred hat of white mull, with a puffing of pink ribbon around the edge, and a pink bow exactly on the top. I went to church with father and mother; the high, old-fashioned pew was rather an uncomfortable seat; the only relief I had was to kick my heels softly against the back. I remember it seemed to take the ache out of them wonderfully. Generally I was a pretty good girl in church, but on this day I don't know what was the matter with me—I had the fidgets. Mother shook her head, and grandma gave me a caraway seed to suck, and father looked at me over his spectacles, but it all did no good, I could not seem to sit still. I plaited folds in my nicely-starched calico until mother took my hand and held it for awhile; then I took off my hat and tried to hang it on the button which fastened the door, until father took it away; then I turned the leaves of the psalm book until it scared me by dropping on the floor with a thud. Oh! I couldn't begin to tell you all the naughty things I did; but the last and most dreadful was to fumble in my brother Ralph's pocket until I found a little wooden comb which he always carried, then I softly tore a fly leaf from the psalm book, and before I knew it I went 'toot, toot, toot!' right out there in the meeting.

"I tell you, that was a dreadful minute!" said Grandma, looking sober, while her audience giggled. "I hadn't the least idea of making such a noise. It had never gone very well for me before, and I was as much astonished as any one could be to hear it sound out like that. The minister stopped in the middle of his sentence and looked at me with a solemn face. Father set me down hard on the seat, and mother's face turned the color of the red roses which were looking in at the side window. Of course they took the comb and the psalm leaf away, and it frightened me to think they went in my father's pocket. I knew I should hear more of it. After that I sat pretty still, but I did not dare to raise my eyes to the minister's face.

"I always used to like Sunday afternoon, because mother told us a story, and grandfather took us a walk through our own home fields and had always something sweet and interesting to tell us. First, though, we went to grandfather's room right after dinner, and each told all we could remember about the church service. I generally had my little story to tell, young as I was. Sometimes it was only a line of a hymn, or a little piece of the text, or maybe one sentence in the prayer. On this Sunday I had not a word to tell; try as I would, I could not recall a line or word. The only thing I could seem to think of, was that noise I made on the comb. Father asked the questions instead of grandfather, and that frightened me, because I knew father was displeased with me. 'What was the matter, Ruth?' he asked at last. 'Don't you think the minister spoke distinctly?' I thought a minute, then I said I didn't believe he did; for if he had, I should have remembered a little bit about it.

"'What do you think the sermon was about?' he asked. And I said, 'It was about Ahab.' I don't know what made me say that; only I had heard a story of Ahab only the Sabbath before, and he was in my mind. I thought from father's face that I had guessed right, so when he asked me for any words in the text, I thought I would guess again; and I said it was about Ahab's doing worse than all the rest of the kings. Then father turned to your uncle Ben, and said, 'Benjamin, you may repeat the text; do it slowly, that Ruth may see what part she has left out.' Just think how I felt when Ben repeated, 'So they read in the book in the law of God distinctly, and gave the sense, and caused them to understand the reading.' I cannot tell you how ashamed I felt!

"What do you suppose I did! I wanted to hide my face in mother's lap, and tell her how sorry I was; if I had done so, it would have been better for me. Instead, I slipped behind her chair and ran out of the side door. There stood the old well with the bucket full of water[141] and the dipper hanging beside it. I felt very hot, and I thought I would take a drink of water to cool me; then if father asked why I run away, I could say I went for a drink of water. It was an unlucky day for me all around; what ailed that dipper I never could understand. Perhaps it was because I had my hat on; I was swinging that by its elastic when father was questioning me, so finding I had it in my hand when I slipped away, I put it on my head, and I think maybe the dipper hit against its edge; anyway, what did that water do but stream down over my starched Sunday dress, and my white dimity collar; and I never knew it until I drank my fill!

"Ben came in search of me, and led me back into grandfather's room, wet as I was, and struggling to get free. 'Put her to bed!' said father, in a voice which I knew must be obeyed. So I was undressed and laid in my trundle bed, and all that bright afternoon I had to lie there. My father wasn't over severe, children."—Grandma paused to say this, seeing disapproval in the eyes of her audience.—"You see I had been told not to help myself to a drink from that bucket because it was set too high for me; so, though I did not think of it at the time, of course it was disobedience. Well, I lay there, and the only occupation I had was to spell out the words of that text, to repeat to father the next morning. He sent it up to me all printed out on a card; I was just beginning to learn to read print, and I had to work hard, I tell you, to get it learned. But the worst was the next day. There was to[142] be a ride on the lake in the afternoon, and I was to go. When I was all dressed, in my blue and white, made fresh for the occasion, father came in, took out of his pocket that dreadful comb, with the fly leaf of the psalm book wrapped around it, and said: 'Ruth, your mother and I have decided to give you a treat this afternoon while we are gone for our ride. You are to sit in this chair by the window, and make music on this comb; make it as loud and as much as you want to.'

"And if you'll believe it, they went away on their ride and left me sitting there!"

The children exclaimed over this, and Marion ventured to say she had no idea that Great-grandfather Wells could be so cruel; she was sure dear Grandfather Burton would never do such a thing; and as for papa, he never could.

"Cruel!" said Grandma Burton, with a flash in her eyes which made them look like Marion's. "Never you call him that; a better father never lived in the world; only times are changed, that is all. Mind you this: I never misbehaved in church again; and I could always repeat the real text, after that, instead of stopping to make one up."

One instance will illustrate; a neighbor had a piece of land to sell. It was not valuable land, but Mr. Taylor wanted it because if anyone bought it for a building spot it would cut off the view of the lake from the front piazza, and Mr. Taylor very indiscreetly remarked in Walter's presence, "I shall buy that corner at any price, for it is worth a great deal more to me than to anyone else."

On his way to school Walter stopped to look at what he already counted a part of the home grounds. He was planning rows of trees, and gravel walks, when the owner came along and entered into conversation. Walter was ready to talk, and desirous of telling what he knew, and very early in the conversation he said, "Father means to buy this corner."

"Indeed!"

"Yes; he says he will have it at any price, for it is worth a great deal more to him than to anyone else; so he means to bid on it to-morrow."

"Well, we shall give him a chance," said the owner, laughing. And as he walked on he secretly thanked Walter for that bit of information. To Mr. Taylor's surprise, he found another apparently anxious bidder the next day, and he found himself forced either to pay an exorbitant price or relinquish the idea of becoming the owner of the lot. Before he had fully decided to do the latter, his rival stopped bidding and the lot was struck off to him at three times its real value. The former owner chuckled over what he called his "good luck," and though Mr. Taylor wondered a little, he never knew that his boy's folly in repeating a careless remark of his own, had cost him so dear in giving his unscrupulous neighbor the opportunity of taking an unfair advantage.

Another time Walter spoiled a surprise which his father and mother meant to give his sister.

"You'd better hurry home from school to-night," he said that morning as they neared the academy.

"Why?" asked Ella.

"O, nothing! only it is my advice to get home as quick as you can, and see what is going on."

"What do you mean?"

"You'll find out!"

"Are we going to have company?"

"Company? Well, yes—I don't know but it might be called company—a sort of dumb companion—well,[143] no—you couldn't call it dumb either."

"Walter Taylor! is it something father and mother do not want me to know?"

"I don't know how they will help your knowing."

"I believe you are letting out a secret and I will not listen! I should think folks would learn not to tell you any secrets."

"They didn't tell me. I heard a man tell father that it had come."

Ella Taylor failed in her recitations that morning for the first time during the quarter. Her thoughts were at home, in the parlor; she knew exactly where it ought to stand and wondered if they would put it in the right place. She tried to study, but Walter's hints which were too plain to be misunderstood insisted upon crowding themselves into her mind.

"Come in, Ella!" her mother called from the parlor as Ella was hanging her hat and wraps in the hall. Ella obeyed the call with flushed cheeks. She could not feign a surprise which she did not feel, and she stood embarrassed and uncertain what to do for a moment, then burst into tears.

"Poor child! the surprise is too much for her," said her father.

"It isn't that," said Ella; "I tried to be surprised and I couldn't, that is why I cried."

"Did you know about it?" asked Mr. Taylor.

"Yes, sir; Walter told me this morning, and I was so glad, I could not study at all."

Mr. Taylor turned towards Walter who began to excuse himself.

"I never said a word about a piano!"

"But you said enough for me to guess," said Ella. "I tried not to know," she added, turning to her parents, "but I could not help it. But don't blame Walter. He didn't think."

"I do blame him," said Mr. Taylor sternly. "Walter, will you never have any regard for other people's property? You have no more right to dispose of other's secrets than you have to dispose of their money! If you took five dollars from my desk you would be a thief. But what do you call yourself when you take my secrets and use them to gratify your love of talking? I sometimes wonder if you will ever have a lesson severe enough to cure you of this fault. Now you have spoiled this little surprise which we had planned and given Ella an uneasy day."

"I am sure I did not mean to tell her; I only wanted to tease her a little."

"You wanted to let her know that you possessed knowledge which she did not, I suppose. Or rather I presume you simply wanted to talk. My boy, if you would learn to regard the secrets of others and also to reserve your own opinions now and then, you would save yourself and your friends much mortification."

Meantime Ella had dried her tears and was now ready to try the new piano, but Walter was too chagrined to enjoy music, and went up to his own room saying within himself, "I wonder if I can never learn to hold my tongue!"

"By thy words shalt thou be justified, and by thy words shalt thou be condemned."

Just when he had read or learned those words Walter did not know, but they came into his mind suddenly. He supposed they were in the Bible, but he thought it queer that he should have remembered them just then. And as he repeated them he thought, "I suppose that means that if one's words are wrong or foolish, he is condemned—that makes solemn business of talking!"

You have told your friend Katie about the story and asked her if she didn't think it was real silly to make such an ado over clothes; you have said you were sure you would just as soon wear a blue gingham as not if it was clean and neat. But now let me venture a hint. I shouldn't be surprised if that was because you never do have to go to places differently dressed from all the others. Because if you did, you would know that it was something of a trial. Oh! I don't say it is the hardest thing in the world; or that one is all ready to die as a martyr who does it; but what I do say is, that it takes a little moral courage; and, for one, I am not surprised that Nettie looked very sober about it when the afternoon came.

It took her a good while to dress; not that there was so much to be done, but she stopped to think. With her hair in her neck, still unbraided, she pinned a lovely pink rose at her breast just to see how pretty it would look for a minute. Miss Sherrill had left it for her to wear; but she did not intend to wear it, because she thought it would not match well with her gingham dress. Just here, I don't mind owning that I think her silly; because I believe that sweet flowers go with sweet pure young faces, whether the dress is of gingham or silk.

But Nettie looked grave, as I said, and wished it was over; and tried to plan for the hundredth time, how it would all be. The girls, Cecelia Lester and Lorena Barstowe and the rest of them, would be out in their elegant toilets, and would look at her so! That Ermina Farley would be there; she had seen her but once, on the first Sunday, and liked her face and her ways a little better than the others; but she had been away since then. Jerry said she was back, however, and Mrs. Smith said they were the richest folks in town; and of course Ermina would be elegantly dressed at the flower party.

Well, she did not care. She was willing to have them all dressed beautifully; she was not mean enough to want them to wear gingham dresses, if only they would not make fun of hers. Oh! if she could only stay at home, and help iron, and get supper, and fry some potatoes nicely for father, how happy she would be. Then she sighed again, and set about braiding her hair. She meant to go, but she could not help being sorry for herself to think it must be done; and she spent a great deal of trouble in trying to plan just how hateful it would all be; how the girls would look, and whisper, and giggle; and how her cheeks would burn. Oh dear!

Then she found it was late, and had to make her fingers fly, and to rush about the little wood-house chamber which was still her room, in a way which made Sarah Ann say to her mother with a significant nod, "I guess she's woke up and gone at it, poor thing!" Yes, she had; and was down in fifteen minutes more.

Oh! but didn't the little girls look pretty! Nettie forgot her trouble for a few minutes, in admiring them when she had put the last touches to their toilet. Susie was to be in a tableau where she would need a dolly, and Miss Sherrill had furnished one for the occasion. A lovely dolly with real hair, and blue eyes, and a bright blue sash to match them; and when Susie got it in her arms, there came such a sweet, softened look over her face that Nettie hardly knew her. The sturdy voice, too, which was so apt to be fierce, softened and took a motherly tone; the dolly was certainly educating Susie. Little Sate looked on, interested, pleased, but without the slightest shade of envy. She wanted no dolly; or, if she did, there was a little black-faced, worn, rag one reposing at this moment in the trundle bed where little Sate's own head would rest at night; kissed, and caressed, and petted, and told to be good until mamma came back; this dolly had all of Sate's warm heart. For the rest, the grave little old women in caps and spectacles, which wound about her dress, crept up in bunches on her shoulders, lay in nestling heaps at her breast, filled all Sate's thoughts.[147] She seemed to have become a little old woman herself, so serious and womanly was her face.

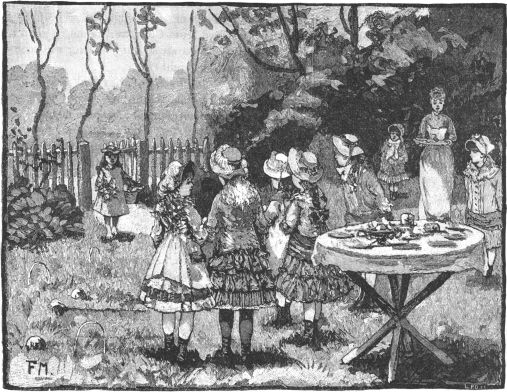

Nettie took a hand of each, and they went to the flower festival. There was to be a five o'clock tea for all the elderly people of the church, and the tables, some of them, were set in Mr. Eastman's grounds, which adjoined the church. When Nettie entered these grounds she found a company of girls several years younger than herself, helping to decorate the tables with flowers; at least that was their work, but as Nettie appeared at the south gate, a queer little object pushed in at the west side. A child not more than six years old, with a clean face, and carefully combed hair, but dressed in a plain dark calico; and her pretty pink toes were without shoes or stockings.

I am not sure that if a little wolf had suddenly appeared before them, it could not have caused more exclamations of astonishment and dismay.

"Only look at that child!" "The idea!" "Just to think of such a thing!" are a few of the exclamations with which the air was thick. At last, one bolder than the rest, stepped towards her: "Little girl, where did you come from? What in the world do you want here?"

Startled by the many eyes and the sharp tones, the small new-comer hid her face behind an immense bunch of glowing hollyhocks, which she held in her hand, and said not a word. Then the chorus of voices became more eager:

"Do look at her hollyhocks! Did ever anybody see such a queer little fright! Girls, I do believe she has come to the party." Then the one who had spoken before, tried again: "See here, child, whoever you are, you must go right straight home; this is no place for you. I wonder what your mother was about—if you have one—to let you run away barefooted, and looking like a fright."

Now the barefooted maiden was thoroughly frightened, and sobbed outright. It was precisely what Nettie Decker needed to give her courage. When she came in at the gate, she had felt like shrinking away from all eyes; now she darted an indignant glance at the speaker, and moved quickly toward the crying child, Susie and Sate following close behind.

"Don't cry, little girl," she said in the gentlest tones, stooping and putting an arm tenderly around the trembling form; "you haven't done anything wrong; Miss Sherrill will be here soon, and she will make it all right."

Thus comforted, the tears ceased, and the small new-comer allowed her hand to be taken; while Susie came around to her other side, and scowled fiercely, as though to say: "I'll protect this girl myself; let's see you touch her now!"

A burst of laughter greeted Nettie as soon as she had time to give heed to it. Others had joined the groups, among them Lorena Barstow and Irene Lewis. "What's all this?" asked Irene.

"O, nothing," said one; "only that Decker girl's sister, or cousin, or something has just arrived from Cork, and come in search of her. Lorena Barstow, did you ever see such a queer-looking fright?"

"I don't see but they look a good deal alike," said Lorena, tossing her curls; "I'm sure their dresses correspond; is she a sister?"

"Why, no," answered one of the smaller girls; "those two cunning little things in white are Nettie Decker's sisters; I think they are real sweet."

"Oh!" said Lorena, giving them a disagreeable stare, "in white, are they? The unselfish older sister has evidently cut up her nightgowns to make them white dresses for this occasion."

"Lorena," said the younger girl, "if I were you I would be ashamed; mother would not like you to talk in that way."

"Well, you see Miss Nanie, you are not me, therefore you cannot tell what you would be, or do; and I want to inform you it is not your business to tell me what mother would like."

Imagine Nettie Decker standing quietly, with the barefooted child's small hand closely clasped in hers, listening to all this! There was a pretense of lowered voices, yet every word was distinct to her ears. Her heart beat fast and she began to feel as though she really was paying quite a high price for the possibility of getting Norm into the church parlor for a few minutes that evening.

At that moment, through the main gateway, came Ermina Farley, a colored man with her, bearing a basket full of such wonderful roses, that for a minute the group could only exclaim over them. Ermina was in white, but her dress[148] was simply made, and looked as though she might not be afraid to tumble about on the grass in it; her shoes were thick, and the blue sash she wore, though broad and handsome, had some way a quiet air of fitness for the occasion, which did not seem to belong to most of the others. She watched the disposal of her roses, then gave an inquiring glance about the grounds as she said, "What are you all doing here?"

"We are having a tableau," said Lorena Barstow. "Look behind you, and you will see the Misses Bridget and Margaret Mulrooney, who have just arrived from ould Ireland shure."

Most of the thoughtless girls laughed, mistaking this rudeness for wit, but Ermina turned quickly and caught her first glimpse of Nettie's burning face; then she hastened toward her.

"Why, here is little Prudy, after all," she said eagerly; "I coaxed her mother to let her come, but I didn't think she would. Has Miss Sherrill seen her? I think she will make such a cunning Roman flower-girl, in that tableau, you know. Her face is precisely the shape and style of the little girls we saw in Rome last winter. Poor little girlie, was she frightened? How kind you were to take care of her. She is a real bright little thing. I want to coax her into Sunday-school if I can. Let us go and ask Miss Sherrill what she thinks about the flower-girl."

How fast Ermina Farley could talk! She did not wait for replies. The truth was, Nettie's glowing cheeks, and Susie's fierce looks, told her the story of trial for somebody else besides the Roman flower-girl; she could guess at things which might have been said before she came. She wound her arm familiarly about Nettie's waist as she spoke, and drew her, almost against her will, across the lawn. "My!" said Irene Lewis. "How good we are!"

"Birds of a feather flock together," quoted Lorena Barstow. "I think that barefooted child and her protector look alike."

"Still," said Irene, "you must remember that Ermina Farley has joined that flock; and her feathers are very different."

"Oh! that is only for effect," was the naughty reply, with another toss of the rich curls.

Now what was the matter with all these disagreeable young people? Did they really attach so much importance to the clothes they wore as to think no one was respectable who was not dressed like them? Had they really no hearts, so that it made no difference to them how deeply they wounded poor Nettie Decker?

I do not think it was quite either of these things. They had been, so far in their lives, unfortunate, in that they had heard a great deal about dress, and style, until they had done what young people and a few older ones are apt to do, attached too much importance to these things. They were neither old enough, nor wise enough, to know that it is a mark of a shallow nature to judge of people by the clothes they wear; then, in regard to the ill-natured things said, I tell you truly, that even Lorena Barstow was ashamed of herself. When her younger sister reproved her, the flush which came on her cheek was not all anger, much of it was shame. But she had taught her tongue to say so many disagreeable words, and to pride itself on its independence in saying what she pleased, that the habit asserted itself, and she could not seem to control it. The contrast between her own conduct and Ermina Farley's struck her so sharply and disagreeably it served only to make her worse than before; precisely the effect which follows when people of uncontrolled tempers find themselves rebuked.

Half-way down the lawn the party in search of Miss Sherrill met her face to face. Her greeting was warm. "Oh! here is my dear little grandmother. Thank you, Nettie, for coming; I look to you for a great deal of help this afternoon. Why, Ermina, what wee mousie have you here?"

"She is a little Roman flower-girl, Miss Sherrill; they live on Parker street. Her mother is a nice woman; my mother has her to run the machine. I coaxed her to let Trudie wear her red dress and come barefoot, until you would see if she would do for the Roman flower-girl. Papa says her face is very Roman in style, and she always makes us think of the flower-girls we saw there. I brought my Roman sash to dress her in, if you thought well of it; she is real bright, and will do just as she is told."

"It is the very thing," said Miss Sherrill with a pleased face; "I am so glad you thought of it. And the hollyhocks are just red enough to go in the basket. Did you think of them too?"

"No, ma'am; mamma did. She said the more red flowers we could mass about her, the better for a Roman peasant."

"It will be a lovely thing," said Miss Sherrill. Then she stooped and kissed the small brown face, which was now smiling through its tears. "You have found good friends, little one. She is very small to be here alone. Ermina, will you and Nettie take care of her this afternoon, and see that she is happy?"

"Yes'm," said Ermina promptly. "Nettie was taking care of her when I came. She was afraid at first, I think."

"They were ugly to her," volunteered Susie, "they were just as ugly to her as they could be; they made her cry. If they'd done it to Sate I would have scratched them and bit them."

"Oh," said Miss Sherrill sorrowfully. "How sorry I am to hear it; then Susie would have been naughty too, and it wouldn't have made the others any better; in fact, it would have made them worse."

"I don't care," said Susie, but she did care. She said that, just as you do sometimes, when you mean you care a great deal, and don't want to let anybody know it. For the first time, Susie reflected whether it was a good plan to scratch and bite people who did not, in her judgment, behave well. It had not been a perfect success in her experience, she was willing to admit that; and if it made Miss Sherrill sorry, it was worth thinking about.

Well, that afternoon which began so dismally, blossomed out into a better time than Nettie had imagined it possible for her to have. To be sure those particular girls who had been the cause of her sorrow, would have nothing to do with her; and whispered, and sent disdainful glances her way when they had opportunity; but Nettie went in their direction as little as possible, and when she did was in such a hurry that she sometimes forgot all about them. Miss Sherrill, who was chairman of the committee of entertainment, kept her as busy as a bee the entire afternoon; running hither and thither, carrying messages to this one, and pins to that one, setting this vase of flowers at one end, and[150] that lovely basket at another, and, a great deal of the time; standing right beside Miss Sherrill herself, handing her, at call, just what she needed when she dressed the girls with their special flowers. She could hear the bright pleasant talk which passed between Miss Sherrill and the other young ladies. She was often appealed to with a pleasant word. Her own teacher smiled on her more than once, and said she was the handiest little body who had ever helped them; and all the time that lovely Ermina Farley with her beautiful hair, and her pretty ways, and her sweet low voice, was near at hand, joining in everything which she had to do. To be sure she heard, in one of her rapid scampers across the lawn, this question asked in a loud tone by Lorena Barstow: "I wonder how much they pay that girl for running errands? Maybe she will earn enough to get herself a new white nightgown to wear to parties;" but at that particular minute, Ermina Farley running from another direction on an errand precisely like her own, bumped up against her with such force that their noses ached; then both stopped to laugh merrily, and some way, what with the bump, and the laughter, Nettie forgot to cry, when she had a chance, over the unkind words. Then, later in the afternoon, came Jerry; and in less than five minutes he joined their group, and made himself so useful that when Mr. Sherrill came presently for boys to go with him to the chapel to arrange the tables, Miss Sherrill said in low tones, "Don't take Jerry please, we need him here." Nettie heard it, and beamed her satisfaction. Also she heard Irene Lewis say, "Now they've taken that Irish boy into their crowd—shouldn't you think Ermina Farley would be ashamed!"

Then Nettie's face fairly paled. It is one thing to be insulted yourself; it is another to stand quietly by and see your friends insulted. She was almost ready to appeal to Miss Sherrill for protection from tongues. But Jerry heard the same remark, and laughed; not in a forced way, but actually as though it was very amusing to him. And almost immediately he called out something to Ermina, using an unmistakable Irish brogue. What was the use in trying to protect a boy who was so indifferent as that?

"Yes, I know, but that old thing won't go."

"How do you know that?"

"I don't, only I should suppose if it hadn't been past its usefulness, Grandfather Bradley would not have bought a new one in its place."

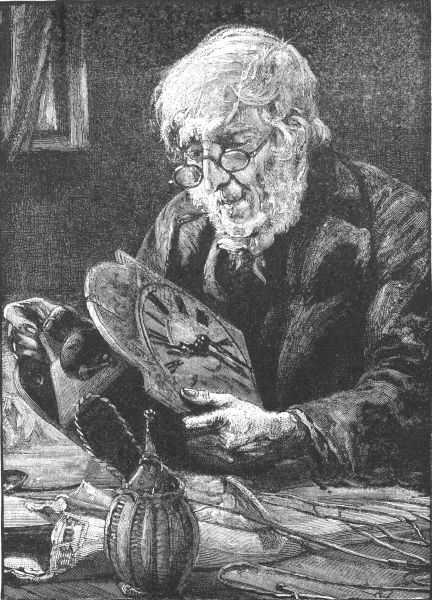

"O, people do not always use things until they are worn out; did I not hear you tell aunt Mary that our centre-table looked so shabby and old-fashioned that although it was strong and not broken at all you intended to send it to the attic and have a new one? Now I suppose that either aunt Mary or aunt Charlotte thought the same thing about the old clock, and when some 'Yankee peddler' came along with a new-fashioned Connecticut clock, they coaxed grandfather to buy one and sent this old one to this dark corner. Now I am going to investigate." Indeed Tom was soon ready to report. "See here, Nell! I believe that the old thing only needs cleaning and oiling to put it in running order. Let's take it down to Lampson and see what can be done."

By this time I was interested; to have that old clock down in the hall would be to excite the wonder, admiration and envy of the neighborhood. The old man laughed when he saw it.

"I remember that clock. I sold your grandfather the one which took its place. I was a young fellow then, and I remember that your aunts wanted a new clock while the old gentleman thought the old one was good enough; but the girls always had their way with their father. I have wondered about this old clock lately and meant to try to get hold of it and make my fortune out of it;" and the old man laughed heartily; "but you young ones have got the start of me. Yes, it is all right; I can make it run about as well as ever. It will outlast half a dozen modern clocks. Thirty years? Yes, more'n that. It's nigher fifty years since I used to sell clocks, hereabouts. Well, changes have come about that would astonish one to know, since then.

"Tom," said the old man suddenly, after a pause in which his thoughts seemed busy with the past, "when I was a young fellow like you I did not think that at seventy I should be just an old tinker; there's a place over across the river that used to just suit my fancy and it was my ambition to get rich enough to buy it and take a sweet girl I knew in those days over there and live out my time, growing old, respected and looked up to as your grandfather was. Do you know why I failed? My boy, I threw away just thirty years of my life! That is why I failed. Your father can tell you how he has seen me reeling through the streets in those days. There were half a dozen of us fellows and I am the only one left—the only one who has escaped a drunkard's grave. And I have only just escaped. It was after I had squandered my money, broken my wife's heart, made my children outcasts and ruined my health that I was saved. All the rest went down, drinking to the last. I tell you, my boy, never touch it! Never tamper with temptation! Yes, I can fix the old clock and make it run about as well as ever, but you can't mend up an old drunkard and make him tell off the remaining hours of his life with any certainty. Whiskey somehow uses up the inside works and it is a poor sort of a service that a worn-out old rum drinker can render his Master. And Tom, I say, let rum alone! And Nellie, don't have anything to do with a young fellow that will not sign a pledge!"

The old clock adorns our lower hall, is much looked at and admired; but to Tom and me, every stroke as it tells off the hours comes as a warning voice, and we seem to hear the old man saying, "Never tamper with temptation."

What was going on? Why, this was the dedication of Bethany Chapel, the room for which the young men and the young women up on these Hills have been working for years. Yesterday it was in order. On the wall hung a motto at which everybody looked and smiled. It was a very pretty motto:

Then of course every one of them said "Yes, ma'am," in their eager little voices; and then I suppose some of them went home and forgot all about it. Not so little Faith whose story I am going to tell you. She thought it over, fixing all the powers of her mind on it. She talked it over with her particular friend Robbie, as he worked with the scissors and a sheet of paper trying to cut a pattern for a new kind of cart wheel which he intended to make.

How should she get a nail to put in the new Sunday-school room? It ought to be a very big nail, Robbie," she explained. "Because, you see, I should want it to help hold something; and I should want it to hold real hard, or else I would be ashamed of it."

Robbie agreed, but was too busy with his wheel to say much. "And where do you s'pose I could get one?" said Faith. "If I only had some money I could buy a great big one; but I haven't a single cent."

It took days of thinking and planning, and hunting, but at last, oh, joy! Faith found the object of her desire; a great big nail! Very rusty and a trifle bent, but so large that it filled her heart with delight. Never was a happier maiden than the one who carried the precious nail to her teacher, all neatly wrapped in paper. Some of the scholars laughed, and said it was not good for anything; but that was because they did not know any better. That blessed superintendent did not laugh. He received the gift with smiles and thanks, and he took it down town and had it straightened, and covered with gold; so that the unsightly rusty thing glowed with beauty, and then it was used to hold the[155] motto; and is to fill its place in Bethany Chapel so long as the building stands. Will anybody say little Faith did not do what she could?

But I want to tell you about the meeting. There were many speeches and much singing. When Doctor Hays began to speak, all the little children straightened themselves and made ready to listen; there was something in his voice which made them think he was worth listening to.

"Children," he began, "how many know what I have in my hand?" Hundreds of voices answered that he had a watch.

"Is there anything about it in the Bible?"

This they did not know; so he told them he wanted them to be sure to remember his text, for it was that one word, "Watch," and they would find it in Mark, thirteenth chapter and last verse. He had quite a time getting them to remember where it was, and they laughed a little at their mistakes; but at last I think every boy and girl there could give it correctly. He had a good deal to say about a watch; how the "little fellow" inside of it worked away all day and all night, and day after day, never stopping to fret because it had so much to do; never resolving that it would begin to-morrow morning and do great things, and being content because of that resolve to do nothing, for awhile; it just worked away, a tick at a time. Then he said there were three things he wanted to tie to their memories by the help of that watch. First, they were to watch for scholars for their Sabbath-school. Every boy and girl there ought to be on the watch for those who went nowhere else, and nab them.

Second, they were to be on the watch against sin. He knew a very little boy who once prayed this prayer: "Dear Lord, make Satan look just like Satan every time he comes after me, so I will know who he is, and fight." That was a good prayer, said Doctor Hays. "You see to it that you know who Satan is, every time, when he comes after you. When he comes whining to you that it isn't a very bad thing to hang around the street corners, and play, or to disobey your mother, or to tell what isn't true, say to him 'You are Satan: I know you; and I am not going to have anything to do with you.'"

Thirdly, they were to be on the watch for opportunities to do good. There was a very earnest little talk about that, which I have not room for; and besides, I cannot tell it as Doctor Hays said it; I wish I could. But the three heads to his sermon I remember, because of the watch on which he hung them. What made him think of the watch? Because, when the disciples of Jesus were talking with him, one day, he said that word, not only for his disciples, but for you and me: "And what I say unto you, I say unto all, watch." And after he was through talking with them, he went to Bethany. So as the new school was named Bethany, the doctor thought the scholars would remember his sermon and text better if he told it in that way.

There were some little boys and girls who recited Bible verses about the House of the Lord, each bringing an evergreen letter which commenced their verse, and when the letters were hung on the wire waiting for them, they spelled

I began to copy the verses for you. Then I decided not to do any such thing. I said: I will tell the Pansies about it, and ask them to hunt out verses for themselves which will spell the same; verses that they think would fit their Sabbath-school, or describe what their lives ought to be, or that they like very much, for some reason. Then they will have an acrostic of verses of their own. How many will do it? What is the use of our going to so many places together, if we don't learn some new nice things to do when we get home?

When it was done and declared to be a good likeness, each fellow armed himself with snowballs, and, standing a little way off, the command was given to fire, and "Old Snooks" received a merciless pelting, one ball hitting him squarely in the eye, another on the nose, another knocking off an ear, until the image was completely demolished amid shouts of triumph.

Then somebody else was set up for a mark. But usually the most fun was in building a fort and laying siege to it—or rather storming and taking it.

Once the real "Old Snooks" himself came staggering by while the boys were raising the breastworks. He stopped a moment to swear as he usually did, when one of the little "rascals" took deliberate aim and fired, and Snooks' old hat was lifted into the air and landed over the fence into a big snowbank.

Now when the boys saw the rage of the old man, and that he was making for them as fast as his poor legs would let him, away they ran. But all that night and the next day they trembled and kept out of the way, fearing the wrath of Old Snooks.

The wretched man found it easier to catch his hat than scampering boys. So he gave up the chase and urged his way homeward.

But the track was drifted, and his limbs chilled. Soon he fell, but was picked up by a passing neighbor and carried to his miserable home.

Not long after the village bell tolled for his funeral. Those boys were thoroughly sobered when they remembered that their fun had something to do with Old Snooks' death; so they resolved that, whatever they did, they would never find pleasure again over the misery or sin of any one.

One day when their snow fortress was done and besiegers and besieged were about to see which party was master of the situation, several of General Gage's soldiers came along. This was more than one hundred years ago, and the "village" was Boston; the playground Boston Common; Gage, the British general in command. It was a time when almost every American man, woman and child, was "mad" at England because of taxes or the "Stamp Act."

The wise old men said with an ominous shake of the head that trouble was coming. The boys heard it and began to talk war and "play soldier." They were at it now. Those in the fort were "British;" those about to storm it, "Americans."

The passing soldiers heard the words, "Drive the Britishers out;" "shoot them;" "kill the tyrants." Though it was all in play, the words stung them, and coming suddenly upon the[157] boys, they handled them roughly, calling them "young rebels," and demolishing the fort.

This did not make the boys less "rebel." They spread the news of their bad treatment by General Gage's soldiers. Teachers, parents, everybody, was angry.

The next day a procession of boys, headed by one of the "storming party," marched through the Common and halted before General Gage's headquarters. Three of the number were admitted to his presence and asked what it all meant. Nothing frightened by being surrounded by officers, glittering with armor, the young "captain," looking the great general full in the face, recounted the affair about the destroying of their fort by the soldiers.

General Gage patiently heard the statement and promised to reprove his men and see their sport should not be spoiled again in that way.

So the procession departed in triumph. The boys were no more molested.

But the Revolution soon came on, and instead of snowballs and snow forts and the sport of children, there were musket balls and roaring cannon, there were stone forts and "banners rolled in blood."

Seven years of war followed, in which the sword, the bayonet, the bullet, fire and famine, played their awful part, and—"the Britishers" went home to England.

America was free!

How many of those boys who snowballed "Old Snooks" and visited General Gage became Congressmen, I have never heard. Yet I dare say some of them got into the high places of the new nation.

But one of the best "resolutions" ever passed was theirs:

Never to have fun at the expense of such creatures as "Old Snooks."

"Finally we reached the shore. I did not know where we were. We got in a train, and after a few hours' ride, changed to a carriage, and drove through the streets. The rest of the party seemed greatly interested in the signs over the store doors, but as I had never learned to read, I saw nothing strange about them. We reached a large building, and were ushered into a fine 'suite of rooms.' That was what they called them. As I was the only pin on the cushion, my mistress sent for some more, and soon several were placed with me. From them I learned that we were in Paris, in the country of France, though it was with difficulty that they made me understand, and doubtless we could not have talked together at all, only they had met an English pin, who had taught them some of his language. They were Parisians, as they told me with much haughtiness, but if they were, I did not like them for they were very proud. My dear young friend, if you ever expect to be agreeable company, you must not be proud.

"By some chance, a disconsolate-looking, and acting pin was put on the cushion, after the Parisians had all gone. He told me he was English; and gave me the story of his life, which was a very sad one. He said he did not care what happened to him now, and that the first chance he could get, he should make away with himself. I advised him not to do so, and tried to console him a little. But it was useless. He said that without friends, life was but a burden to him.

"When I told him how I was made into a pin, he seemed much amazed, and said the wire that he had been made of had been softened by heating, and then had been pounded and twisted like a horseshoe into the right shape. He said that that was the way with all his former English friends, and he sighed. Then I was proud (I confess it) of my country; proud that I was an American, and did not have to go through all English pins did! While my creation only lasted ten seconds, his took many minutes.

"Just as we were discussing the different methods by which we were made, my mistress (and his) came into the room, and he hurriedly said good-by.

"'You will never see me again. She will take me, and not you. Mine has been a sad life, and it will have a sad end. I hope that you will be happy. You are the only one that has ever tried to comfort me since all my friends were taken away from me; but you could not. Good-by!' And with that, my mistress took him away.

"She went over to the marble basin with the silver faucets, and turned some water in, while she held the pin, not very securely, I suppose, for he tried with all his strength, and gave a leap into the basin. The water carried him swiftly through the hole, and he was seen no more!

"O how I felt! To see one of my own race go to destruction before my eyes was hard to bear! I would have wept, but you know that is impossible to me, but whenever I think of the sad, sad fate of him with whom I was acquainted, for so short time, my brassy heart aches, as it were, and I feel as if I must go and comfort him, lie he in sewer or sea!"

(Just here the pin seemed much moved, and trembled so violently that I put my hand on the edge of the desk, to keep him from falling off.)

Presently he continued: "Let this be a lesson to you, my dear young friend, never to be discouraged, whatever be your lot in life, or you will meet with a sad fate, like my poor acquaintance, the English pin.

"It must have been for about a week then, that my life was rather dull. I was sorry for this; I longed for something to divert my mind from the sad scene I had witnessed. All I could[159] do was to gaze disconsolately at the shining marble basin in the corner of the room, feeling that it was a sort of tombstone erected over the body of my friend, and make a solemn resolve never to become so discouraged with that which it was my duty to bear, as to desire to put an end to my existence, but always to bear patiently the task set before me. And you, my boy, will find your life much happier, if you make the same resolve.

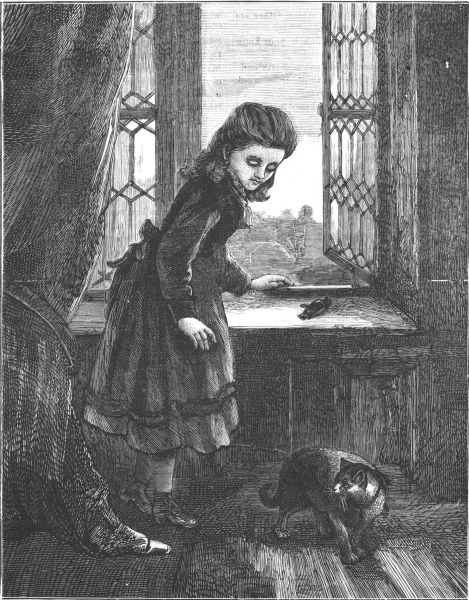

"One day while my mistress' little girl was sitting reading by the window, a gentleman came in who had made his appearance during the last few days, and whom the children called uncle. He invited her to take a walk. She hastily brushed her hair, and hunting around for a smaller pin, evidently, took me reluctantly, to pin her sash with, and hurried down to meet her uncle, who was waiting at the hotel door; for that I had learned was the name of the building.

"They walked along down many streets, until finally they came to one where stores were. Into one of these the little girl went, and bought a paper of pins; as soon as they reached a quieter street, she took me out, so as to fill my place with a smaller pin, and would have thrown me into the gutter, but her uncle stopped her, saying:

"'Give it to me, if you don't want it. Never throw away even so small a thing as a pin, my girl, or you may want one very much, some day.'

"She laughed, and handed me to him, and he put me on the inside of his coat. When they reached home, or rather the hotel, he bade all the family good-by, and that evening boarded a train, and travelled till we reached another large city, where he took a steamer the next day, and I learned from some of his remarks that he was going back to America. I was very glad, I can assure you, for by this time I had grown homesick. The ride back was just about the same as the ride away from home had been, the only incident of any importance, that I remember, being that my master once fell overboard while I was on his coat, which was exceedingly disagreeable for both of us, until the sailors rescued us, and though I suppose those same brave men did not even know of my existence, I think I was really as thankful to them as was my master.

"When the steamer reached New York, the gentleman took a train, which, after a few hours' ride, brought us to a small town, where we found at the depot a carriage waiting for my master, with a gentleman in it, who greeted him warmly.

"During the ride to the stranger's house, he suddenly exclaimed:

"'Will, my cuff has come unpinned, and the pin has mysteriously disappeared. Have you another for me?'

"So my master put his hand to his coat, where I had been ever since we left Paris, and gave me to the gentleman. He, of course, fastened his cuff with me, and I remained in it till night, when, as he was taking it off when making ready for bed, he (whom I had so faithfully served) accidently dropped me from the open window, and I fell into a crack in the sidewalk!"

"But, doctor, I must have some kind of a stimulant. I am cold, and it warms me."

"Precisely," came the doctor's crusty answer. "See here, this stick is cold," taking up a stick of wood from the box beside the hearth and tossing it into the fire, "now it is warm; but is the stick benefited?"

The sick man watched the wood first send out little puffs of smoke, and then burst into flame, and replied: "Of course not: it is burning itself!"

"And so are you when you warm yourself with alcohol; you are literally burning up the delicate tissues of your stomach and brain."

Yes, alcohol will warm you, but who finds the fuel? When you take food, that is fuel, and as it burns out, you keep warm. But when you take alcohol to warm you, you are like a man who sets his house on fire and warms his fingers by it as it burns.—Temperance Banner.

"We don't allow drunken people in here," he said coldly, "you'll have to stay outside."

"I ain't drunk," cried Thomas, roused to action; "I'm blest if I am; I'm only unfortunate."

The man laughed loud and long, and called to another, "See here; here's a chap got off his train—not half seas over, you know, oh no! only he's unfortunate."

Thomas' face blazed in an instant. That he, Mr. Bang's man, who had filled one place for a good dozen years, and was saving and industrious, with no taste for the company of low-lived fellows and no leaning toward their habits, should be brought face to face with one of them in this unlucky moment of his life when courage was at its lowest ebb, seemed to him the cruelest blow of Fate, and it deprived him of what little remaining sense he had.

"If anyone says that to me again I'll pitch right into him," he shouted.

"Good—hurrah! he knows what's what!" cried the fellow, a stalwart lounger whose only interest had been in seeing the train come in and depart. When that was over, he had nothing else for his active mind to work upon, and he hailed with delight this new excitement. "Come on, fellows, this chap is determined to fight. So we won't disappoint him. You're a drunken, good-for-nothing sot," he cried in Thomas' face.

Thomas gave one plunge and struck the quarrelsome man squarely in the face.

"Take that, and that, and that," he cried, beside himself in a passion. Never in his life engaged in a quarrel involving blows, now that he was in one, it was purely delicious to give free rein to his anger, and for the first few moments he felt a man indeed.

The young fellow thus struck and two or three other men now closed around him, and he was soon occupied in warding off as best he might the shower of blows, kicks and cuffs that fell to his portion. The noise brought speedily to the spot, the depot officials, one or two farmers riding by, and all the boys in the vicinity.

"Stop—hold—I won't have any of that!" cried the ticket agent, puffing up in authority.

"Oh! won't you?" cried one of the men whose blood was up, and pounding away at Thomas, whom they had succeeded in getting to the ground.

"No, I won't," cried the ticket agent, "I'll have you all arrested."

"Who's going to do it, I'd like to know," asked another man derisively.

Meanwhile Thomas was shouting out his case, and succeeded in catching the ear of a farmer who sitting on the bags of meal in his wagon had paused to see what the trouble was about.

"It's my opinion," said the farmer deliberately, and stopping to clear his throat now and then with a sharp Hem! "that you want me to give you three chaps a poundin' that man, a taste of my whip, and it's also my opinion that I shall do it." With that he sprang from his wagon with surprising alertness considering he looked so old, and, whip in hand, he advanced upon the crowd.

They all fell back. He had "whip" in his eye, and beside, every one knew Jacob Bassett, and that there was no reason to think he would fail to do as he said.

Before all could desert Thomas, however, the last man had the benefit of the leather lash, and he ran off rubbing his leg, and uttering several ejaculations as if he had received enough.

"My man," said Farmer Bassett, tucking up his long whip under his arm and helping Thomas to his feet, "now what's the matter with you?"

"I'm in trouble," said Thomas briefly.

"So I should think," said the old farmer with a wise nod.[163]

"I don't care about myself," said Thomas not regarding certain flapping portions of his once neat suit, nor mindful of the other signs of his predicament, "but it's young master and those other boys who were left to my care." At mention of them, he became helpless once more, and began to bemoan his fate.

"Hah!" said the old farmer. He had boys of his own, not so very long ago either, although he looked so old, and though they were all but one out in the world and promising to be successful men, his heart went back to the time when they were little chaps and running about the farm.

The one who was not out in the world was safe at rest from all temptation and suffering. There was a tiny grave on the hill-top back of the old homestead, and here the farmer often stole in an odd moment, and Betsey his wife went of an afternoon when the work was done up, for a quiet time with her darling—the little Richard, so early folded away from her care, and Sundays they always went together to get peace and resignation for the coming week.

"What's the trouble with the boys?" asked the farmer, quickly.

Thomas looked into his face and the first gleam of hope he had known, now radiated his own countenance. Here was a man who evidently meant to help, and that right speedily.

"Oh sir," he cried, "they're over at Sachem Hill, and locked out of their house."

"Over at Sachem Hill and locked out of their house," repeated the farmer. "How did that happen?"

"'Twas me," cried Thomas miserably, and then he laid bare his confession.

Farmer Bassett said never a word, only as Thomas finished, "Come," he commanded, and motioning him to the green wagon, he climbed in, and seated himself again on his bags.

"I'm goin' to stop a minute an' tell Betsey to put us up a few things, an' while she's doin' it, I'll hitch into the sleigh. I took the wagon to mill, as 'twas poor draggin' along one piece o' bare ground—an' then, says I, we'll be off for them youngsters of yours."

Thomas gave a long breath of relief—and the wagon rolled on in silence till it came to a stop before a large red house.

This child's name was Isaac Newton. He belonged to a country gentleman's family. His father having died, his mother's second marriage occasioned the giving of the child into the care of his grandmother. As he grew older he gained in health and was sent to school. Having inherited a small estate, as soon as he had acquired an education which was considered sufficient to enable him to attend to the duties of one in his position, he was removed from school and entrusted with the management of his estate. However, this young Newton developed a passion for mathematical studies which led him to neglect the business connected with his estate. He busied himself in the construction of toys illustrating the principles of mechanics. These were not the clumsy work which might be expected from the hands of a schoolboy, but were finished with exceeding care and delicacy. It is said there is still in existence two at least of these toys; one is an hour-glass kept in the rooms of the Royal Society in London.

Isaac Newton's mother was a wise woman in that she did not discourage his desire for the pursuing of his studies and for investigation. She did not say, "Now, my son, you must put away these notions and attend to your business. You have a property here which it is your duty to manage and enjoy. You should find satisfaction in your position as a country squire and consider that you have no need of further study." On the contrary, this mother allowed her son to continue his studies; he was prepared for[164] and entered the college at Cambridge when he was eighteen. From that period until his death, at eighty-five, he devoted himself unweariedly to mathematical and philosophical studies.

You all know the story of the falling apple. He had been driven by the plague in London to spend some time at his country-seat in Woolstrop, and while resting one day in his garden he saw an apple fall to the ground. Suddenly the question occurred, Why should the apple fall to the ground? Why, when detached from the branch, did it not fly off in some other direction?

And where do you suppose he found the answer? Read the first sentence of this article and see if you find it there! The truth had been the controlling power of all the falling apples since the creation, but it had never before been understood or formulated; perhaps this discovery of the law of universal gravitation gave him more renown than all his other labors put together.

He met with a sad misfortune, later, when, by the accidental upsetting of a lighted candle, the work of twenty years was destroyed. The story as told by a biographer is, that Sir Isaac left his pet dog alone in his study for a few moments, and during this brief absence the dog overturned the candle amongst the papers on the study table. It is further told as an evidence of the calmness and patience of the great man, that he only said, "Ah! Fido, you little know of the mischief you have done!"

But although he was so quiet under the great loss, the trial was almost too much for him; for a time his health seemed to give way, and his mental powers suffered from the effects of the shock. He died in 1725, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

She excelled in portrait painting; when she went to London she was engaged to paint the portraits of "the most distinguished and beautiful ladies of the court." She everywhere received much attention, both on account of her[165] talents as an artist, and her beauty and charming manner. Some of her pictures are in the Royal Gallery in Dresden; others may be seen in the Louvre in Paris.

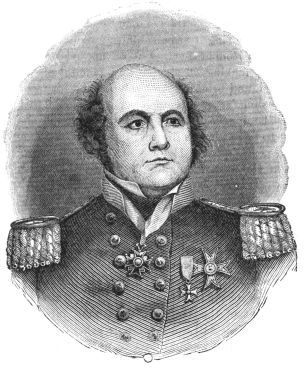

Away they sailed from the wharf where many came to see them off, among them Lady Franklin, Sir John's wife.

Away they pushed through the sea toward the North. On they went, further and further from their home, to see if they could find the North Pole or what was called the "Northwest Passage."

Soon they met icebergs, or great mountain castles, moving down from the north. But the Erebus and Terror turned aside and sailed north, north, north, hundreds of miles.

Then the winter came on. The two ships were soon hedged in by the ice. They could neither go forward nor backward. The ice became thicker and thicker; the nights longer and colder. The men were clothed in fur, and there were stoves in the ships, but they shivered with the cold. No word came to them from their friends. They, however, tried to be cheerful, hoping for spring and the breaking up of the ice so they could sail out of their prison and find the Northwest Passage.

They sang, told stories, read, celebrated each other's birthday; good Sir John read sermons and prayers to his men as was his custom and exhorted them to be of good cheer. It was a joyful thought to them of making wonderful discoveries in that strange land and then coming back some day with the news.

But the spring came and went, another and another, but no tidings of Sir John. Then there was alarm. Meetings were called, speeches made, great sums of money raised; brave captains and crews offered to go in search of him. Vessel after vessel went and came, only to report failure.

Five years passed; seven; nine; ten—Hope was dying—eleven. Lady Franklin did not give up, but fitted out, at her own expense, a little ship.

Captain and sailors bid good-by to wives and friends, not knowing they would ever see them again, as they resolved not to come back till they found out something as to the fate of Sir John.

So this little ship disappeared far away northward, and, like the others, in a few weeks, was in the midst of majestic palaces of ice.

But it worked its way on, when, lo! one day as the captain was hunting here and there, he came upon parts of a ship, and he knew it was Sir John's. He also found Sir John's own handwriting and many other things that told of great sufferings and death.

It appeared that he had died June 11th, 1847; but he was not found till 1857. All had perished.

He was a noble Christian man, with a heart tender as a woman's.

When the little ship came back with the news, England mourned as did this nation over the fate of Sir John Franklin.

(You will remember that the fourth of March is always the Inauguration Day, when the President of the United States goes into the White House as Leader for four years.)

Now let the Leader start to music from the piano—through the parlors, halls, dining-room—perhaps if the cook is pleasant, to the kitchen. These little games do a great deal to draw all the family together with a happy feeling. If he stops a minute to examine anything, the company following him in Indian file must stop too and imitate his movements, as if examining something closely. If he says in the course of his travels "ooh—ooh!" just like a pig, each one of the pillow-slip-and-sheet brigade must say "ooh—ooh!" also in the same tone without smiling, unless he laughs. If he says "cock-a-doodle-doo-o!" each one must say it. Whoever fails to follow his Leader imitating him in everything, and whoever smiles or laughs, or says anything unless the Leader does, must be pointed out by the audience, dropped out of ranks, set up in a corner, told to stand there until the game is played out, and all take off sheets and pillow-slips—to sit down and laugh over it all, before plates of apples and cracked walnuts.

May you have a jolly time with your March game. I wish I could play one with the Pansies.

I spent a day at his house and had many funny talks with Poll; parrots can talk after a fashion.

She was a fine lady, not so large as some you may have seen at the New Orleans Exposition. Some of them were from two to three feet long. One was perfectly green; another, white; a third, nearly all bright colors.

The one I saw in Cincinnati was fond of her friends, but sulky and cross to me, a stranger.

She had learned many wicked words from passers-by, swearing words even. When she could not have her own way and, like other folks, was out of humor, she would "let fly" her worst opinions of people and things in her bad language.

At such times she did not seem so beautiful with all her gay plumage. Few folks do appear well when out of sorts, no matter how rich and fashionable their clothes. Remember that.

In the picture you see a parrot sitting upon a perch. It is another one and there is a long story about it. But all stories can't be put into The Pansy without bursting its covers. However, you may hear a little about this one and think out the rest when your thinkers get time.

This Pol came from a distant land. She had such rich feathers, and could talk and sing so well, and, withal, her manners and behavior were so correct that she made friends of everybody.

So in due time Pol was treated like one of the family and as one of the first ladies in society—so far as a parrot could be. Her bread and drink[167] and bed were all any bird could wish. She had the freedom of the house. Without asking, she could go up stairs or down, out door, into the barn, to the top of the highest trees, sometimes to the neighbors. She always came home at meal and bed time. Every one, nearly, knew her and treated her politely. Thus she forgot her far-away relations and became happy "as happy can be." She was now a maiden lady of sixty years. Some parrots live to be one hundred. Pol's life had been pleasant as a June morning. But June doesn't last forever. Trouble came.

One day she went out to call and was quietly walking home. A bad boy met her and made some provoking remarks. Instead of paying no attention to such creatures and going right on her way, she stopped, listened, lost her temper and "sauced him back." Then what should the fellow do but strike Pol and tear out some of her finest feathers and, leaving her half-dead, went his way. Pol managed to drag herself home, and, as best she could, tell what had happened.

How grieved they all were and wondered who could have treated her so cruelly. They suspected who had done it; for that boy was given to such things. Some seem to delight in giving pain to animals. I need not say what was done to that hateful boy. He deserved punishment and received it. But Poor Pol, what of her? She was tenderly washed and coaxed to eat and tell more about it. Her appetite left her in spite of all that could be done and she became sad and silent and wished to retire to bed.

It was hoped that she would feel better in the morning; but when morning came, there she sat, her wings drooping and her eyes cast down like one that is passing through great sorrow.

Near by lived a lad by the name of Eddie Landseer. He thought the world of Pol. As soon as he heard of her misfortune he came running in with a playmate, a bright little girl, to see what they could do for their afflicted neighbor.