"ANIMAL SPIRITS."

No. V.—Golf. "The Old Scotch Terriers."

(By Mr. Punch's own Short Story-teller.)

I.—THE PINK HIPPOPOTAMUS. (continued from page 81.)

In these awful circumstances, with the night air whistling past me, and with my beloved Chuddah and her nurse hurtling upwards beside me, it is scarcely necessary for me to say that I never for an instant lost my coolness and my perfect self-possession. That the situation was dangerous, nay, almost desperate, I fully realised, but it is in these very situations that true courage and resourcefulness are always of the highest value. Again and again in the course of my long life have I plucked safety, aye, and that which is higher and better than all safety, namely, reputation, from the nettle danger. Let fools prate as they will; the brave man must always rise triumphant above the stormy waves of envy and detraction.

These thoughts, I admit, did not occur to me at the moment. Our flight was too perilous and too swift to allow me to think of aught save what concerned the immediate necessities of this truly fearful crisis. Poor little Chuddah, I observed, being made of lighter material, was gradually outstripping me in this dreadful and involuntary race. First her head topped me; then her shoulders soared beyond me; at last her feet were on a level with my face. As one of them (I forget which) passed upwards, I was just able by leaning slightly forward, to imprint a kiss upon it. "Farewell, Chuddah," I sighed, as the lovely foot left my lips. "Farewell, Orlando," she murmured all but inaudibly, and fled up, up, up into the dismal night. I never saw her again.

The Ayah, however, a stout and heavy woman, was still beside me, rising inch for inch as I rose. By turning slightly round I could look at her. I did so. Judge of my horror when I realised by the faint light of the stars that the Ayah was no longer alive! The shock of the sudden ascent must have proved too much for one accustomed to the sedate and comfortable life of an eastern palace, and enfeebled, moreover, by advancing age. The explosion acting on such a constitution had snapped the cords that kept life in her faithful body. The Ayah was dead, and I who tell this tale was alone with a corpse in the encircling atmosphere! As I realised this horrible situation, I confess that for the first and last time in my life I turned faint with a feeling almost amounting to fear. In imagination I saw myself speeding for ever, as the æons revolved in their courses, with only a dead Indian nurse to keep me company. Then, by an instantaneous revulsion, the grim humour of the situation struck me. With only my knapsack of provisions and my brandy-flask, it was unlikely, even under the most favourable circumstances, that I should be able to prolong life for more than a week. At the end of a week, then, I too should be a corpse. I laughed aloud as I thought of the last scion of the Wilbrahams, the unconquerable Orlando, mated in mid-air to the dusky Ayah, a skeleton to a skeleton, and my sepulchral "Ha, ha," went reverberating through the dim spaces of night. The sound roused me once more. Why, after all, should I die? Life was sweet; much remained to be done; there were wrongs still to be redressed in the world below; millions of the oppressed still waited for a deliverer; countless herds of big game still roamed the prairies or made their lairs in the forests of earth. No, I would live if I could, and prove once more the unquenchable fortitude of my race.

At this moment I looked down.

(To be continued.)

Monday.—Now that the Law lectures at the different Inns have been "thrown open to the public," any outrage in the way of cringing to the democracy may be expected. They'll be opening Lincoln's Inn Fields next to the mob!

Tuesday.—They have! And a steam merry-go-round set up within thirty yards of my formerly tranquil Chambers! Oh, why was I ever called?

Wednesday.—Dinner in Hall to-day. Found two perfect strangers dining at my table! Seems that the Benchers have thrown open dining-hall to the public as well! Asked strangers if they intended being called to the Bar? One of them replied (with a wink) that he didn't—why should he? He could get all the legal training, use of library, &c., without going to expense of a call.

Thursday.—In Court. Unknown Counsel opposed to me. Seem to recognise his face. Can it be the stranger who dined in Hall last night? It is. New rule has thrown the Courts open to amateur pleaders! What are we coming to? Must say stranger pleads uncommonly well. And Judge so deferential to him!

Friday.—Wonders never cease. To-day my stranger of yesterday found seated on Bench! Judge ill—has appointed him as Commissioner in his place. New rule allows this sort of thing. What is the reason of this sudden democratising of the Profession?

Saturday.—Mystery explained. One of the Benchers wants to be made a L. C. C. Alderman! In his Election Address he even stoops so far as to give way to the vulgar delusion that Law is expensive, and recommends a rule that costs should always be "on the lower scale." Perhaps he is right. Everything on the lowest possible scale at Bar nowadays!

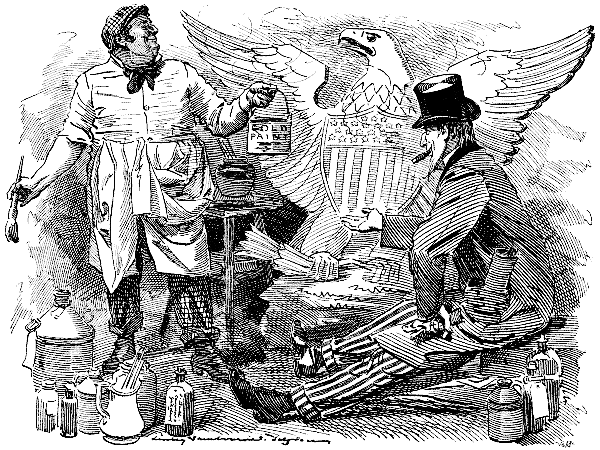

John Bull (Painter and Decorator). "Always ready to oblige so good a Customer!"

Brother Jonathan. "Guess this time the Obligation's mutual!"

["The amount subscribed in England for the United States Loan was £120,000,000, or twenty times the sum reserved for London."—Daily Paper.]

"Why, I was a thinking, Sir," returned Mark Tapley, "that if I was a painter, and was called upon to paint the American Eagle, how should I do it?"

"Paint it as like an Eagle as you could, I suppose."

"No," said Mark. "That wouldn't do for me, Sir. I should want to draw it like a Bat, for its short-sightedness; like a Bantam, for its bragging; like a Magpie, for its honesty; like a Peacock, for its vanity; like an Ostrich, for its putting its head in the sand, and thinking nobody sees it——"

"And like a Phœnix, for its power of springing from the ashes of its faults and vices, and soaring up anew into the sky!" said Martin.

Martin Chuzzlewit.

Brother Jonathan loquitur:—

He was prejudiced, that Mark, a Eurōpian, in the dark,

Concernin' of our Glorious Institutions.

He paint our Bird o' Freedom? Lots have tried, but we don't heed 'em;

And revolvin' years bring curus retributions.

We don't care a brass farden! Dickens had to beg our pardon,

And that Max O'Rell will eat his words one day, Sir!

The real Yankee Eagle is as strong-winged as a Sea-gull,

With a beak as sharp as any Sheffield razor.

Still, he's been a trifle pippy, and has looked a little chippy—

By the mighty Mississippi yes, Sir!—lately.

Kinder moulty as to feathers, as though blizzards and bad weathers

Of every blamed big sort had tried him greatly.

Good Jee-rusulum! No wonder! for great snakes and buttered thunder!

Our blasts have been fair busters for his pinions.

In the words of Mister Chollop, all creation he can wallop,—

But tornaders have been sweepin' his dominions!

As to that Mark Tapley's twaddle, why the Peacock ain't the model,

Nor the Bantam, nor the Ostrich, I'd be pickin'

For the finest fowl in Natur. Better dub him Alligator,

A Whangdoodle, or a Cincinnati Chicken!

Like the Phœnix he's immortal, and he soars to the Sun's portal,

But—the Phœnix has sick spells, like lesser poultry.

Wants fresh fixing up, I reckon, then the dawn once more he'll beckon,

And sprint—from Memnon's statue to Fort Moultrie.

Bull ain't an Eagle builder, but he makes a bully gilder,

And I reckon, guess, and calc'late I'll jest try him.

If I git from the old fellow a good coat of British Yellow—

A sort o' paint J. B. keeps always by him—

My Bird o' Freedom soaring, where the blizzards are a roaring,

And the cloud-bursts are out-pouring, will jest flicker

Real rollicking and regal, like a genu-ine Golden Eagle.—

Wal!—you've fixed him real smart, John! Let us liquor!

Oh dear no! Merely the "First Open Day" after a long Frost, and a Tom-tit has been inconsiderate enough to fly suddenly out of the Fence on the way to Covert!

Now that hypnotism is in the air, our conversation-books will have to be remodelled, as thus:—

Good morning, have you hibernated well?

Yes, I have had a most successful trance this winter. Have you laid up at all?

Only for a few days at Christmas, just to escape the bills. I had a delightfully unconscious Boxing Day.

Well, you take my advice old man, and rent a private catacomb on the three-years' system. It comes much cheaper in the end, and you save all your coal and gas, to say nothing of clothes.

We've started a Nirvana Club in our neighbourhood on the tontine principle. The last person who wakes gets the prize, unless the first who comes to makes off with it.

It is capital, anyway, when you are taking a tour. Saves all the trouble of sight-seeing. You are just packed up and forwarded from place to place, with an automatic Kodak which records everything you visited. Try it!

Will, some day. By Jove, I must be off! I've got to attend an anæsthetic concert, absolutely painless.

And I've got a mesmeric dinner-party on to-night. All the bores will be put in glass-cases, and fed mechanically.

Good-bye, then. Sleep well!

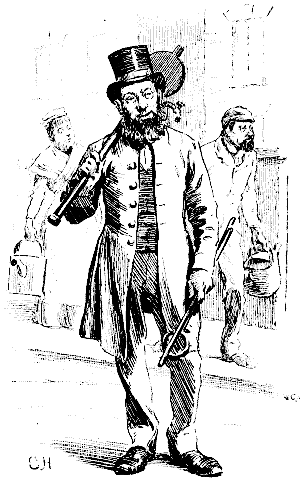

THE TURNCOCK

This eminent individual, born in the early forties, comes of a numerous family, and was originally destined by his parents for the career of a night-watchman. Not feeling, however, any vocation in this direction, he tried many other professions, and many other professions tried him. At last, in the year 1864, he entered the service of the Twiddlesex Water Company, where, by strict attention to the quality of his liquor, and his unfailing perception of the right time to be sober, he has risen to his present conspicuous and responsible position.

Canton des Grisons, Feb. 10.

For the neighbourhood it is a sultry day; glass up to 5° Fahrenheit and a taint of scirocco, or föhn, as the facetious native calls this wind. My toboggan lies idle by stress of drifting snow. "No chance," I say, "of doing a record this afternoon!" This is what I say openly and pompously to my fellows. With my own dear heart I commune otherwise, saying how heaven should be praised for this one blessed day's recess from broken scalp.

If I have asked myself once (as is proper with an enigma) I have asked myself a thousand times, "Why did I come out here, to this resort of invalids and polar athletes?" My right lung is flawless: my left is very perfect. On the other hand I do not show well on ice; my legs are ill-shaped for bandy; curling I find to be but poor sport after skittles; and I have met one wayfarer only, and that a fool, who did not laugh upon my figure-skating.

In a climate where one must either do or suffer something to justify one's existence, there remained this sole thing—to toboggan. I said, "I will surely toboggan!"

"Good!" they said; "but on an instrument of what sort? 'Swiss' for women and children; ordinary 'Americas' for men; 'Skeleton Americas' for heroes."

"I will choose the last," I said; for if I do anything at all I like to do it passing well, and with the best of tools.

There was no lack of willing teachers to illustrate for me the true posture—ventre à terre, and to show me how I should go armed as to my Alpine boots with spiked rakes screwed to the forefront of my sole for the better negotiation of sharp angles on the side of a ravine.

One may add that if a pine-tree, or a telegraph post, or an ascending hay-sleigh opposes your career, you learn by the simple interposition of your head to save the delicate machinery of the toboggan from brutalization. It may be that by inadvertence you have attained an impetus so terrific that you overtake a walking horse in possession of the path. Once again your headpiece will protect the instrument from the fiery choler of the beast's hind hoof. After some two miles of fortuitous descent, diversified by such checks as I have here shadowed forth, you will be rounding the final corner at a pointed angle of 45°, travelling perhaps several miles per hour, when a large beer-cart with an upward tendency will dispute the road. Then the banked snow shall be your pall, and your requiescat shall be rendered by the local teamster in German of a bastard order.

Nor is this all. To the beetling edge of the descent you will first have been conveyed by an impetuous zwei-spänner, thoughtlessly gay with bells and feathers. Twenty-five candidates having urged their claims for the five seats, some will have need to be content to trail behind on their toboggans. As one wanting in experience, you will have the last place assigned to you, or else the last but one, with a casual riderless machine at the tail-end to give you an unholy spasm as it swings off the track round the corners. At intervals, while your pensive mind is absorbed upon the maintenance of a happy equilibrium, rendered strangely-difficult by the ruthless speed of the sleigh, some two or perhaps three of the tailing-party will fall off in front. The sharp contact of several raked boots with your open countenance draws your attention to the altered condition of things. Over the mangled bodies of friend and foe you are carried forward. The sleigh is tardily arrested, and your innocent head becomes the recipient of fearless abuse.

Or again, from some mountain-hut upon the route issues forth a gross and even elephantine dog, born of unhallowed union between a wolfhound and an evilly-bred St. Bernard. Foiled in his attack upon the head of the caravan he revenges himself upon the outstretched leg of the hindmost. The lacerated calf will be your own.

This is well enough in open daylight, and when you are swathed in buskins from heel to hip, and your rakes are good for retaliation. But in doubtful moonlight with the air at 15° below zero, as you toboggan back to your hostelry in the valley from a fancy dress ball, where you have simulated Hamlet in black silk tights and pumps, the humour lies purely on the side of the dog.

But apart from the lower animal nature, in this barbaric sport you are never confident of your dearest friends. Thus, we had been a pleasant and hilarious party at the international bal masqué: the ardour of the stirrup-cup was still upon us as we attained the brow of the decline. By a happy inspiration I had proposed that my friend Mr. Stark Munro, being a heavy-weight and disguised as a Völsunga Saga, should proceed in the van to clear any incidental drift or desultory avalanche. He disappeared headlong down the pine-forest track followed by the Ace of Clubs, a Sardinian Brigand, and a Tonsured Benedictine. All the costumes gained in picturesqueness from the Arctic background.

The New Woman of the party, attired as Good Queen Bess, begged me to precede her, arguing that I should go faster on my Skeleton than she on her Swiss. I engaged to do so on the understanding that she should allow me seven minutes' start in case of eventualities, the course being usually done in some 5¾ minutes under happy conditions. She was to be succeeded by Antigone, the Spirit of the Engadine and the Mother of the Gracchi.

I do not greatly care to linger over the details of my descent. I had started gaily humming those Elizabethan lines, "Fain would I climb, but that I fear to fall,"—out of pure gallantry to Good Queen Bess who had given me a dainty little cow-bell as a favour at the cotillon; and I had been travelling cautiously for 8½ minutes, with my nose, no fewer than six fingers, and all the toes on each foot frostbitten, and a half-moon piece already gone out of my calf at the spot where it had attracted the notice of the St. Bernard wolf-hound, when, even as I was navigating a rotten bridge at a sharp turn, I heard a rushing sound out of the night behind me, and "Achtung!" (the terrible warning-note of the tobogganer) rang in my stricken ear.

I had barely time to throw a backward glance of horror and deprecation, when the projecting feet of Good Queen Bess, her toboggan and her spiked steering-pegs were upon me.

The bridge had never been strong in point of bulwarks; the torrent which it spans is rapid and fed from icy heights; its banks do not lend themselves to debarkation.

When I recovered consciousness by force of exquisitely painful restoratives applied by the Völsunga Saga, the Mother of the Gracchi and Good Queen Bess (herself unscratched, though the plush of her toboggan was tarnished with my gore). I was solemnly intoning, "World without end: Achtung!" with all the conviction of a cathedral tenor. I am going home the day after to-morrow.

Suggestion.—A certain restaurant not a hundred miles away from the St. James's Theatre advertises, among other attractions, "Dîner Salon Gobelin, 7s. 6d." But wouldn't it be more appropriate to spell the last word "Gobbling"?

Air—"Toréador."

["After its recent behaviour, Ecuador cannot be said to have any credit worth talking about."—Times City Article, February 19.]

Ecuador, contento?

Ecuador! Ecuador!

You have all our money spent O,

Who will lend you more?

No one here on British shore

Will lend you more, Ecuador! Ecuador!

From H. W. L.'s Summary of the Debate last Thursday in the Daily News.—"Mr. Barlow approved the action of the Government in exempting coarser yarns from duties." This is not exactly what might have been expected from Mr. Barlow, but no doubt Masters Sandford and Merton in the Strangers' Gallery were mightily delighted at the prospect of "coarser yarns"—(which is only another name for men's stories after dinner when the ladies have left the room)—being "exempted from duties." Really our old friend, the preceptor of Sandford and Merton, has deteriorated, and Mr. Punch is severely against him on this point.

Leader. "Now, don't forget, the Union rate of pay is Fourpence a Doorway. Any Chap workin' for less is a bloomin' 'Blackleg'!"

An Irrelevant Biography.

(Scraps collected by Richard Medallion.)

SCRAP I.—Horticulture. (Boot-trees.)

"Ah! old men's boots don't go there, Sir," said the boot-maker to me one day, rather pointedly, pointing to the toes of the boots I had brought him for mending. As I danced home, writing another chronicle with every springing step, the remark filled me with reflection—such reflection, reader, as your mirror shows you when you gaze in it to rejoice in your own beauty.

Have you kept a diary for thirty years? Dear me! And have you kept your gas bills, your water-rates, your Christmas-cards, your writs, your circulars of summer sales? I might never have undertaken to write this biography if I had not chanced one evening—being unoccupied—to break open a private desk belonging to my friend Narcissus, and tearing open an envelope (sealed, and labelled "Compromising Postcards—to be opened before my death,") came across these old boot-bills, and been struck by the manner in which there lay revealed in them the story of the years over which they ran....

The first night we went to see George Donkeystir we heard in the kitchen a curious voice—suggestive somehow of the vine-leaves in the hair—singing "Ours is a Happy, Happy Home!" In the hall we saw none but a wee boy of four, standing on his head, balancing a billiard-cue on his chin.

"All done by kindness!" lisped the little chap. As we made an attempt to enter the dining-room, what should fall on our heads but a great wet sponge, backed by a ring of laughter from the hidden prompter, and George appeared, shouting "Bo!" followed by the loving wife, who helped to make the fun possible. What a time we had! From the moment we arrived (and fell over a string adroitly arranged by the dear little children across the little hall) to the moment that we had got into our little apple-pie beds, all was fun, frolic, merriment, and domestic joy. Just as we were falling asleep, tired out with a happy evening, we were disturbed by a chorus, as of waits, singing outside our room these beautiful words—

"O! Flo, what a change you know!

When he left the village he was shy,

But since he come into a little bit of splosh

His golden hair is hanging down his back!"

This was more of George's loving ingenuity. But we wished he had made it rhyme. His wife had helped him, but she would not take the credit. "That was George's idea," laughed along her lips. I threatened "to make copy" of him, and now I have done it. Moreover, I shall further presume on his forbearance by writing no more about him for the present.

All the Difference.—In the programme of the Ballad Concerts given in the Times, Mr. Ben Davies was advertised to sing Sullivan's "Come, Come, Margherita." Now the title of this song is its refrain, i.e., "Come, Margherita, come!" which is evidently a lover's passionate invitation, while if it is written as "Come, Come, Margherita," it is clearly only an expostulation of a rather commonplace character uttered to Margherita, who has been exasperatingly petulant, and who won't come when asked. For many many years it was the fashion (as it still is with the veteran tenor) for "Maud" to be invited to "come into the garden," just as the fly used to be requested by the spider to "walk into his parlour." Now it is Margherita who is having her turn (in the garden) with Ben Davies.

"Come along, Bobbie! Don't lag behind!"

"Wait a minute, Mother. There are two Soldiers going to meet. I just want to see the Battle!"

Or, The Burden of the Bells.

The new Progressive Dick Whittington, would-be Lord Mayor of London, sitteth on Saturday, March 2, 1895, and meditateth on the probable meaning of the L. C. C. Election Bells:—

Hear the loud Election bells—

Noisy bells!

What a world of wonderment their clatter-clash compels!

How they jangle, jangle, jangle,

On the air of coming night!

Like committee-men a-wrangle,

And my thoughts are in a tangle

Of mixed doldrums and delight.

How they chime, chime, chime!

In my head there runs a rhyme,

And I wish I were but certain what their shindying foretells,

What a future I may gather from the voices of the bells—

The jangling and the wrangling of the bells!

Now they sound like wedding bells,

Golden bells!

Meaning mischief in their music to the Moderates and the swells!

Their vibrations there's a vox in

Which to me sounds like a tocsin.

From their molten golden notes,

All in tune,

What a pleasant sound there floats

Like a promise of Progressive Party Votes,

Blessed boon!

Oh, from Bow to Sadler's Wells,

What a gush of Unity voluminously swells.

How it swells!

How it dwells

On the Future! how it tells

Of the Progress that impels

To the swinging and the ringing

Of the bells, bells, bells.

From the Brixtons, Claphams, Southwarks, Islingtons and Clerkenwells,

To the rhyming and the chiming of those bells!

Hear the Rate-Alarum bells—

Brazen bells!—

What base tarradiddles their loud turbulency tells!

In men's startled ears in spite,

How they scream out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak

They can only shriek, shriek,

Through the fog,

In a clamorous appealing to the voters to retire

That much Progressive Party, which—much like the Rates, or fire—

Climbeth higher, higher, higher,

With a desperate desire,

And a bullying endeavour

Now—now to sit, or never

In the seat of Gog-Magog!

Oh, those bells, bells, bells,

What a tale their terror tells

Of despair!

What reactionary roar!

What a horror they outpour

On the bosom of the City and Mayfair.

Yet the ear it fully knows

By their twanging

And their clanging

How the voting ebbs and flows.

Yet the ear distinctly tells

In the jangling and the wrangling

How Monopoly sinks or swells

By the sinking or the swelling in the clangour of those bells—

Beastly bells!—

is Landlordism, Ground-rents, Dirty Slums, and Drinking Hells

In the clamour of those horrid Moderate bells!

Hear the rolling of the bells,—

Polling bells!

What a world of solemn thought their monody compels.

So Dick Whittington—poor wight!—

Heard them ringing, with delight

At the fair prophetic promise of their tone!

For every sound that floats

May I too hope my votes

Will have grown?

And the People—ah, the People!—

Is their verdict, from each steeple,

All mine own?

Does that tolling, tolling, tolling,

Mean "Return again my Dick!"

Or do they as they're rolling

Mean "turn out" or "cut your stick!"?

Shall I be "Lord Mayor of London"?

Or are we Progressives undone

At the Polls?

Pussy, what is it that tolls

From each belfry, as it rolls,

Rolls?

A pæan from the bells

To the Party of the Swells?

Or a message from the bells

That Reaction howls and yells?

Does that tintinnabulation

Mean false Joe's "Tenification"

Or our own "Unification"?

Sounds dear "Betterment" this time

In the rolling Runic rhyme

Of the bells?

Does their throbbing mean that jobbing,

And the London Landlord's robbing,

Find their finish in these bells?

That Monopoly is sobbing

To the sobbing of those bells?

That their knells, knells, knells,

Ring out in Runic rhyme?

Does the rolling of those bells

Mean that I turn out this time?

Can they possibly mean that,

Faithful, purring, Pussy-Cat,

After all your sweet mol-rowing?

Sounds the verdict "Dick is going"

In the tolling of the bells, bells, bells, bells, bells,

In the moaning and the groaning of the bells?

The New Progressive Dick W. "WHAT ARE THE BELLS SAYING, PUSSY? 'TURN AGAIN, WHITTINGTON, LORD MAYOR OF LONDON,'—OR IS IT 'TURN OUT'?"

Mrs. Bonner has done well to write a record of the life and work of her father, Charles Bradlaugh, which Fisher Unwin publishes in two volumes. If it had been one 'twould have been better. Mrs. Bonner has been assisted in her labours by Mr. J. M. Robertson, who deals with Mr. Bradlaugh's political doctrine and work, and describes in detail his parliamentary struggle. The consequence is that the record runs into two closely-printed volumes, a proportion that somewhat overweights the interest of the subject. Mrs. Bonner is, naturally, indignant at the treatment her father received in the early days of his parliamentary life and in other public relations. But Mr. Bradlaugh was a fighting man. He gave hard knocks and, to do him justice, did not unduly complain when knocks were dealt back to him. It is a pathetic story how the crowning triumph of his life came in the hour of his death. He never knew that the House of Commons had unanimously agreed to the motion which expunged from its journals the resolution excluding the junior member for Northampton from its membership. That confession, my Baronite says, was the completest justification of the action on Mr. Bradlaugh's part that enlivened the Parliament of 1880-5 and was the immediate cause of the birth of the Fourth Party.

Mr. John Davidson's Earl Lavender is "pernicious nonsense," and the Aubrey Beardsley frontispiece—if, considering its subject, it can, with absolute correctness, be described as a "frontispiece,"—might, a few years ago, have endangered its existence. But "I suppose," quoth the Baron, "I am becoming old-fashioned, and 'we have changed all that now.' But in view of this extraordinary illustration, is it a book that can be left out 'promiscuously-like' on the drawing-room table? I trow not," quoth the Baron. "And as to The Great God Pan ('Key-note' series), well—infernally or diabolically clever it may be, but should I be informed," quoth the Baron, "that we should never look upon its like again, I, for one should not grieve."

Another Keynoteworthy book, i.e., one quite worthy to belong to such of the Key-note series as the Baron has read, is The Dancing Faun. Had a novel appeared some years ago in the palmy, but not less leggy, days of the drama at the Gaiety, entitled The Dancing Vaughan, when the elegant Kate of that ilk was the light and leading danseuse, what a vogue such a volume would have had among the patrons of the above-mentioned Temple of Burlesque-Extravaganza. "Où sont les neiges d'antan?" and "Where is dat barty now?"

B. de B.-W.

A Double Applicability.—"Intrigues which render stable government impossible," though a phrase applied by the Times to Egyptian affairs, would, it is clear, be applicable to attempts to get at the jockey, or the stable assistants, guarding the loose box of the Derby favourite.

Professional Model. "It's comin' to somefing. Burney Jones a drawrin' fur Daily Papers! Bad enuf when 'e draw'd fur the Fe-ay-ters. I reckon 'e'll be on the Pavement next."

[Note.—Sir Edward Burne-Jones, who designed the costumes for the L-c-m, has made a drawing representing "Labour" for the D-ly Chr-n-cle.]

(A Dreadful Object-Lesson.)

I've often thought I'd like to write a sonnet,

I wonder, though, if I can find the way.

Sometimes you muse upon your mistress—say

Her eyebrow, then you poetise upon it.

Maybe instead you celebrate her bonnet,

A striking symphony in green or grey.

And when it's done, for many and many a day,

With eager eye, you ever scan and con it,

Intent on seeing that it's quite correct,

And free from all suspicion of defect,

No inauspicious phrase, no halting line.

And when the time of scrutiny is past

Your thought is probably exactly mine—

Thank heaven! the horrid thing is done at last!

The St. James's Gazette, in giving the news of the Cabinet Council meeting last Thursday, said, "Mr. John Morley left at 12.30, and Mr. Fowler a few minutes later; but a messenger was almost immediately despatched to call the last-named Minister back, and he returned to the Council Room, and remained until 12.35, when the Council broke up."

So you see a good deal may happen in five minutes.

Jones (who has come to stay the night at Little Peddlington Hall, and finds he's forgotten to bring his white ties). "I want some White Evening Ties, please."

The Village Draper. "I'm sorry we 'aven't got any in Stock, Sir. You see the White Tie Season has 'ardly commenced!"

At the re-opening of the Royal United Service Institution last week by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, in new premises at Whitehall, a novel and ingenious electrical instrument was exhibited. By means of this addition to the list of communicators a general in the field is able not only to send an autograph letter to a colleague or subordinate at a distance, but also to convey in fac simile a drawing of his own composition. On the occasion to which reference is made, the Prince of Wales sent a message to his brother. To this despatch the Duke of Connaught was obliged to respond that he did not quite understand its full meaning. According to the reports some slight error was rectified, and then the machine worked to everyone's satisfaction. However, the fact remains that the initial attempt to convey intelligibly a message was not entirely successful. To impress upon those answerable for the perfect action of the instrument the importance of their task, we subjoin an imaginary scene of a nearly impossible situation. We will assume that a commander-in-chief is conversing with a general in the field some ten miles distant.

Commander-in-Chief (wiring). We hear here that a force of twenty-five thousand infantry are advancing by the Dover road with a view to turning your left front.

General in the Field. Kindly repeat. (Message repeated.) No, we do not want any more marmalade, as we have plenty of butter.

C.-in-C. I said nothing about marmalade, I was talking of the enemy. Twenty-five thousand men are advancing on your left front.

Gen. I think I now understand what you mean, but we can't get near Woolwich, because our gas has failed us. However, we will look out for the twenty-five thousand balloons you say are coming.

C.-in-C. I said nothing about balloons. Infantry, I spoke of. They are approaching by the Dover Road.

Gen. Thank you for your offer, but we have plenty of hammocks. We have just seen this. Can you identify her? I forward sketch.

C.-in-C. You have sent me what appears to be a drawing of either a grand pianoforte or a hippopotamus. Which is it?

Gen. It is very difficult to make out your messages. We think we understand your last. Yes, the mail to India did start without the elephants. We did not know that any had been ordered.

C.-in-C. I said nothing about elephants. What is the meaning of your drawing?

Gen. Very sorry; can't make out your message. Besides, have no more time for telegraphing. Twenty-five thousand infantry of the enemy have just been noticed on the Dover Road, threatening our left front. Why did you not tell us they were coming?

But of course, as we have already said, when the hour arrives everything will be in perfect working order. It is to be hoped that there will be a supplementary signal to be used in cases of extreme emergency, to decide promptly a line of action where two courses are open for adoption. It might signify "Toss up."

(When Literary.)

I had a brutal husband, as is our sex's doom,

I put him in a problem-novel; then I made it boom!

I bought a little "Log-roller" who twaddled up and down,

Discovered it, and slavered it, and made it take the town.

But meaner beauties of my sex declared I wore blue hose,

And at my Gospel of Revolt cocked each a pretty nose.

Once again I salute you, oh actors of the Cambridge A. D. C., and congratulate you on your rendering of The Rivals—no mean task for a body of amateur actors. Specially do I note the admirably and grotesquely humorous impersonation of Mrs. Malaprop by Mr. R. A. Austen Leigh. Will the elaborate Wildean paradoxes have to a future generation the freshness and the laughter-provoking qualities of Mrs. Malaprop's derangements? I doubt it. At Cambridge the other day I saw a learned Doctor of Letters in convulsions over the Malapropian sallies. Will a Doctor of Letters towards the end of the next century be seen to smile over Oscar's inversions? Mr. R. Balfour made an excellent Bob Acres, broad in his characterisation, self-possessed and clear. I should have called him, however, a trifle too smart and modish in dress. Mr. Geikie was very effective in the rages of Sir Anthony, and Mr. Watson played well as Jack Absolute. Admirable, too, was the Fag of Mr. Talbot. The leading ladies were, as usual, miracles of curls and divine complexions. Yet did their voices and their hands bewray them. We were fortunately spared the gloomy maunderings of Julia and Faulkland. "Hearty congratters," as they say at the sister university.

A Vagrant.

Her Puzzle.—"I recollect," quoth Mrs. R., "a sort of riddle that used to puzzle me when I was a child, and I can't say I quite see the answer now. It is this: 'If Dick's uncle is Tom's son, what relation is Dick to John?'"

"The Right Man in the Wrong Place."—Labby, M.P., in the Unionist Lobby, Monday, February 18.

Son of Toil. "Ow yus, me an' my Missus gits on fust-clorss tergither, Sir. Reg'lar chummy, we ore. I tells 'er everythink!"

Philanthropist. "Ever tell her a Lie?"

Son of Toil. "Tells 'er everythink, I tell yer——!"

A Trivial Tragedy for Wonderful People.

(Fragment found between the St. James's and Haymarket Theatres).

Aunt Augusta (an Aunt).

Cousin Cicely (a Ward).

Algy (a Flutterpate).

Dorian (a Button-hole).

The Duke of Berwick.

Time—The other day. The Scene is in a garden, and begins and ends with relations.

Algy (eating cucumber-sandwiches). Do you know, Aunt Augusta, I am afraid I shall not be able to come to your dinner to-night, after all. My friend Bunbury has had a relapse, and my place is by his side.

Aunt Augusta (drinking tea). Really, Algy! It will put my table out dreadfully. And who will arrange my music?

Dorian. I will arrange your music, Aunt Augusta. I know all about music. I have an extraordinary collection of musical instruments. I give curious concerts every Wednesday in a long latticed room, where wild gipsies tear mad music from little zithers, and I have brown Algerians who beat monotonously upon copper drums. Besides, I have set myself to music. And it has not marred me. I am still the same. More so, if anything.

Cicely. Shall you like dining at Willis's with Mr. Dorian to-night, Cousin Algy?

Algy (evasively). It's much nicer being here with you, Cousin Cicely.

Aunt Augusta. Sweet child! I see distinct social probabilities in her profile. Mr. Dorian has a beautiful nature. And it is such a blessing to think that he was not brought up in a handbag, like so many young men of the present day.

Algy. It is such a blessing, Aunt Augusta, that a woman always grows exactly like her aunt. It is such a curse that a man never grows exactly like his uncle. It is the greatest tragedy of modern life.

Dorian. To be really modern one should have no soul. To be really mediæval one should have no cigarettes. To be really Greek——

[The Duke of Berwick rises in a marked manner, and leaves the garden.

Cicely (writes in her diary, and then reads aloud dreamily). "The Duke of Berwick rose in a marked manner, and left the garden. The weather continues charming." ...

Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.

House of Commons, Monday, February 18.—Debate on Address finished, at last. Been on the whole dreary business. Instead of sharp roar of honest artillery from Opposition camp at opening of campaign, series of squibs popped off; some of them damp. Novel idea at commencement of new Session for Opposition chiefs to lurk in the wood armed with blunderbusses, watching efforts of lesser villains to waylay and murder Ministers, they coming on scene when these efforts been repulsed. Novel, but on whole not so successful that we are likely to see repetition.

Odd thing is that in series of divisions Government had nearest squeak on motion for the Closure. S. Woods had amendment on paper; wanted to have debate adjourned so that another day might be appropriated for his use; Squire of Malwood thought really been enough talk round Address. Moved closure. Woods and two or three other good Radicals go into Lobby against Ministers; others abstain; Opposition seeing opportunity flock into Lobby; Ministry saved by eight votes.

"Yes," said the Squire of Malwood as we walked home together, after last division, "it is not exactly encouraging. But what distresses me most is the way some of our fellows talk about Rosebery. Used to be old constitutional maxim that the King can do no wrong. Modern reading on our side is that Premier can do no right. Speeches like Dilke's to-night hurt me more than anything else." This conversation followed close on one I had earlier in day with the noble lord.

"How's the Squire looking?" he asked, anxiously. "Bearing up I trust, against the fatigues of a thankless task. What a few of our men say about me not the slightest consequence. Passes over me like fluttering of idle wind. Know all about it. Could, an' I would, describe animating motive in each case. What cuts me to the heart is their treatment of the Squire. He manages admirably. Spares no labour; makes no mistake. Yet whenever some men returned to support us are not permitted to take in own hands direction of public business, they go over to the enemy. Great blessing the Squire is endowed by nature with angelic temper. Otherwise, when this sort of thing happens, he would chuck up the whole business, and tell malcontents and deserters to manage matters for themselves."

So nice to have this state of things existing. Sufferers in common affliction, each thinks only of the other.

Business done.—Address agreed to after ten days talk.

Tuesday Night.—Every prospect of quiet evening, even talk of count out. After spending our nights and days with Address during last fortnight, small wonder if the hearts of Members, untravelled, fondly turn to home. Diversion created by appearance on scene of Howard Vincent. Got up in extraordinary fashion. Round his waist a belt, in which slung miscellaneous assortment of brushes and other articles of domestic use. Pendent were hair brushes, hat brushes, tooth brushes, boot brushes (with case in solid leather), whisk brooms, carpet sweepers, wall brushes, chimney-sweeping machine (with whalebone head and chimney cloth), deck scrubbers, one venetian blind-duster, feather brushes (eight feet long with jointed handles), floor polishers, hearth brushes (white hair and black), lamp brushes, aid one hair waver patent for producing in a few minutes, without the use of heated irons, a natural wavy appearance in the hair. (Frank Lockwood much interested in this.)

Other brushes peeped out from every pocket save those at coat-tails, which, as being more roomy, were reserved for specimens of filters, fish-kettles, bread-platters, revolving boot-cleaners, specimens of boxes in which eggs may be safely sent through the parcel-post, and a lemon-squash stand (oak and nickel mounts complete, with four tumblers, corkscrew, lemon-knife, and glass sugar basin).

"Been to a bazaar?" I asked; "or are you going to give up military pursuits, and set up a stall somewhere on your own account?"

"No, Toby," said the Colonel, severely—"would you just hitch round the handle of that frying-pan? Thank you; it might get in Bartley's way whilst I am addressing the House—these few things you see only partially concealed about my person are the result of the labours of convicts and felons working in foreign prisons. A Government lost to all sense of public duty permits their free importation, to the detriment of honest British workman. You'd better stop and hear me broil Bryce."

Colonel walked off with curious clatter, much more effective than the spurs he wears on field days with the Queen's Westminster Volunteers. Most interesting lecture, occasionally marred by Colonel, intending at particular point to produce a blacking-brush, fishing forth from his miscellaneous store a plated biscuit-box. But the moral all the same. The articles all made in Germany or elsewhere on Continent. Bryce glad to get out of difficulty by offering Committee.

Business done.—Motion carried for restriction of foreign prison-made goods.

Thursday Afternoon.—"Hist!" said Sir Henry James to Joey C. "A word in thine ear. Prince Arthur away to-night; ground clear; suppose we occupy it? show Prince Arthur how we would manage business, and let the Markiss see that there are statesmen other than those who hail from Hatfield and its dependencies. Here's this import duty added on British yarn entering India. Lancashire members sore about it. Don't know much on subject myself, but can do simple rule in arithmetic. If we can detach seven or eight Lancashire Liberals and put on all our forces, the Government must go. Think how pleasant for Prince Arthur, sitting with his feet in hot water and his head out of the window, to hear the tramp of our messenger along Carlton House Terrace bringing news that Government is out. If we'd only time we might hire man with wooden-leg, like the party in Treasure Island, wasn't it? Sound of wooden-leg tramping along silent broadway where Prince Arthur lives, and is just now nursing his cold, would be most dramatic. That a mere detail. Thing is this, Indian cotton business is so much gun-cotton for Government; I apply torch; up they go—Harcourt, Fowler, Asquith (who was so rude to you the other night), and the rest of them. What do you think?"

Joey C. is sly, de-vilish sly; said nothing. But he winked.

Henry James knew that all was well.

Friday, 12.10 a.m.—Not quite so well as it looked when House met at three o'clock yesterday afternoon. Ministerialists then in state of trepidation; Ministers assuming air of resignation. Odds distinctly in favour of defeat of Government. Henry Fowler, formally recognising situation, had declared they were prepared for the worst. Somehow things got mixed; explosion took place as arranged; gun-cotton went off with genial roar; but it was Henry James blown into the air, and with him Joey C. 109 Members mustered under new Opposition Leadership; 304 going with Ministers. Majority, 195.

"Glad I didn't engage the messenger with a wooden leg," said Henry James with deepened gloom. "Awful to have a man of that kind going stamping through a quiet thoroughfare in the dead of the night carrying news of Government majority of a trifle under 200. Wish Prince Arthur would stick to his post and not take colds at such inconvenient seasons."

Business done.—Henry James and Joey C. go out to shear and come back shorn.

Friday, 8 p.m.—House counted out. Members gone home in state of hair-bristling perturbation. Brunner brought under notice of Speaker circumstances attendant upon mysterious disappearance of Joey C. last night. When House cleared for division on James's motion, Joe seen to leave and go into Lobby. Thereafter all trace lost of him. Name does not appear in division list. Witnesses report he was seen endeavouring to induce Serjeant-at-Arms to unlock door and let him pass through. Serjeant incorruptible, inflexible. Joseph turned back and straightway lost to human ken.

"When I was a lad," says Wilfrid Lawson, "I used to be baffled by inquiry, 'Where was Moses when the candle went out?' That a plain proposition compared with this new one, 'Where was Joseph when the division was taken?'" House faced by mystery could not set itself down to business. Something uncanny about the place. Accordingly got itself counted out at eight o'clock.

Business done.—Second reading of London Waterworks Bill carried.