TRUE DIGNITY.

Barbara. "Oh, Mother dear, I've got such a Pain!"

Mother. "Have you, Darling? Where?"

Barbara. "In the Proper Place, of course!"

Question. Having no cash you wish to make a living. Kindly tell me the objections to sweeping a crossing?

Answer. A small sum of money would be necessary to purchase a broom—a preliminary step that could not be surmounted.

Q. Quite so. And would a like difficulty arise to prevent you selling lucifers?

A. Certainly, for matches suitable for street hawking cannot be obtained on credit.

Q. Would a clerkship be within your reach?

A. Scarcely, as a new suit, or a nearly new suit of clothes would be requisite to give one the air of respectability necessary for securing an audience with an employer.

Q. Could you not become a company promoter?

A. Not with safety, now that the winding-up business is superintended by a judge capable of understanding the intricacies of city finance.

Q. Is there any opening for you as a cab-driver?

A. No, as a license cannot be obtained for love, but must be bought with money.

Q. Surely you have a chance as a slave to journalism?

A. Writing for the press is at all times precarious, and is, moreover, a calling which cannot be followed without a small but impossible expenditure on pens, ink. and paper.

Q. Has not life sometimes been supported by the successful attempts to borrow from one's friends?

A. Yes, but this financial condition will have been enjoyed and abandoned before one can truthfully style oneself an ex-capitalist.

Q. The sale of information of an interesting character to those concerned has sometimes—has it not—been found of a profitable nature?

A. Occasionally, but this again is not only an unpleasant but a dangerous operation, and if resisted, may end with an entirely embarrassing prosecution at the Old Bailey.

Q. Then having no cash, no credit, and no references, what career is open to you?

A. But one—to become the responsible manager of a theatrical company touring in the provinces.

"Tempora Mutantur."—In these days of very late dining hours a performance at 5 P.M., if over at 7, or 7.15 at latest, ought to suit those whose daily work is over about 4 or 4.30, and who dislike "turning out" after dinner if they are at home, and who cannot get away from any dinner party if they are out in time to see even half of the entertainment. The matinée at two is a very difficult time, as it clashes with lunch; but as tea can be taken in the entr'actes, five o'clock seems a very reasonable hour, that is, if the show be over at 7.15, and the dinner hour be 8 or 8.15.

Barbara. "Oh, Mother dear, I've got such a Pain!"

Mother. "Have you, Darling? Where?"

Barbara. "In the Proper Place, of course!"

Do not venture on the ice until you can skate properly. Practice the various steps and evolutions before a looking-glass in your bed-room.

There is a great art in falling gracefully, and it is surprising what a number of interesting, complicated, and unlooked-for attitudes and figures can be thus developed. To ensure perfect confidence at the critical moment, it is as well to hire somebody, say a professional wrestler or prize-fighter, to trip you up and knock you down in all the possible methods. A mattress may be used for beginners to fall on. The more improbable your manner of tumbling, the greater success will you achieve in the eyes of the on-lookers.

When skating with a lady, you may cross hands, but it is unusual for you to put your arm round her waist. This is only done in great emergencies, or in a thick fog, or when you have the pond to yourselves. It is generally found that this proceeding is equivalent to skating on very thin ice, and will lead to dangerous consequences.

If, however, a lady, who evidently has not complete control of herself, and does not readily answer her helm, steers straight into your arms, you should accept the situation in your best ball-room manner. Do not attempt to avoid a collision, as if you dodge suddenly, the lady, on failing to meet your support, will probably sit down abruptly on the ice, or get entangled with a sweeper.

Should you, owing to any unforeseen circumstance, find yourself prostrated at a young lady's feet, do not place your hand on your heart and say she is the only girl you ever loved. These little scenes are apt to collect a crowd. Merely say you stopped to examine the thickness of the ice, or any little plaisanterie you feel capable of inventing. Then retire to a discreet distance and rub yourself.

If the ice gives way, and you find yourself in the water, get out as speedily as possible. I do not advise drowning. It is always a wet and uncomfortable process, and has very few recommendations. It is, moreover, quite fatal to true enjoyment, and only those who are morbidly anxious for a "par" in the papers will habitually resort to this mode of creating a sensation.

Do not hit people much with any stick you may think it de rigueur to brandish about. Such personal attentions are best performed when you and a string of ten or twelve other 'Arries are banded together. You can then stand up without fear for the rights of the high-spirited young citizen to enjoy himself.

There is nothing that figure-skaters so much appreciate as the sudden inroad of hockey-players in their midst. It adds immensely to their zest to feel they are liable to be knocked over in the middle of an exciting "rocker" or "mohawk"; and, of course, they like their combined figures to be nicely disarranged, as it enables them to show their skill in sorting themselves again. Hockey should therefore be indulged in anywhere and everywhere.

Lastly, if you prefer sliding to skating, do not slide in a top-hat and frock-coat, unless you are a member of the Skating Club, and even then it looks ostentatious. Dress appropriately in some quiet costume of kickseys and pearlies, with a feather in your hat. Wear your billycock at the back of your head, as it will break your falls. Always shout at the top of your voice.

Once we dreamed of a magical clime,

Powerful fairies lived there then,

Ready to change, in the shortest time,

Men to fishes, or fish to men;

Science, alas, assails the land,

Down the magical palaces fall,

Fairies and elves, we understand,

Never could really exist at all.

Still remain to us spectres strange,

Headless horsemen and monks severe,

Some that arrive each night in the Grange,

Others (like Christmas) once a year;

Yet they linger, a fearful joy,

Elderly relics of childhood's day.

Now our "scientists" would destroy

All their humorous, mild array!

Mr. Maskelyne, learned man!

Scoff at Theosophists as you will,

Spot each fraudulent gambler's plan,

Only allow us our Bogies still!

Little we value prosaic truth,

If it must scatter these shadowy hosts;

Spare us a single belief of youth,

Leave us, ah, leave us at least our Ghosts!

Candid Vet (who has been called in to look at Mr. Noodle's new purchase, which is somehow amiss). "Ah, yer want to know what to do with 'im? Well now, he's been goin' pretty 'ard to Hounds for a Dozen Seasons or more, to my knowledge, has that 'Oss. Now, take my advice, don't keep 'em waitin' for 'im any longer,—you send 'im to 'em!"

Make your Game! Is't fortune, fame,

Power supreme, mere notoriety,

'Tis mere gambling all the same,—

Craving knowing not satiety.

Marquis or Gavroche, what matter?

Rabagas or Noble Red;

How the bullion's clink and clatter

Fires the eye and heats the head!

Mammon-Mephistopheles

At the sight in shadow grins;

And the player, at his ease,

With a dream his heart may please,

Red wins!

Will it win, or, winning, will

La République lose or gain?

Is the game chance versus skill,

Sly intrigue 'gainst heart and brain?

Sanguine as sanguineous,

The Mob-loving Marquis sits.

Exile, will finesse and fuss,

Clack of tongues, and clash of wits,

Play the patriotic game?

Fall the cards, the ball re-spins!

Blood a-fire and walls a-flame

Menace if—to Wisdom's blame—

Red wins!

The Long Frost.—Sportsmen are coming up to town in despair. Their hunters are"eating their heads off," and very soon there will be nothing left to tell the tail!

In the Lords.—Lord Battersea "the Flower of the Flock."

(From Mr. Punch's Very Special Correspondents.)

Reports from all parts of the country are eloquent of the phenomenal nature of the weather experienced everywhere. By an extraordinary coincidence, of which it is hardly possible to make too much, the intense cold has been accompanied by a lowness of temperature—on the (Fahren) height.

The Oldest Inhabitant has had a high old time, and been in immense form. To prevent the extinction in future years of this interesting individual, oxen have been roasted freely, and, wherever at all practicable, carriages have been driven over frozen rivers. Occasionally irreverent descendants have roasted the Oldest Inhabitant.

It is reported, on the authority of Lord Salisbury, that the Liberal Party intend at once to engage in snowballing the House of Lords. As the ex-Prime Minister has promised to play the game with no lack of mutuality, interesting developments are expected.

A very remarkable occurrence comes from abroad—considerations of an international character make it advisable not to particularise further. A bishop went out in the middle of a raging blizzard. Although the bishop was suitably attired in episcopal dress, so that no mistake as to his identity was possible, it went on blizzarding, and the spiritual dignitary was put to extreme temporal temporary inconvenience.

Ice floes have penetrated to London Bridge. Mr. Seymour Hicks's topical song in the Shop Girl—"Oh, floe! ice and snow, you know"—is received every night with even greater enthusiasm than formerly.

The following letter will NOT appear in an early number of The Spectator:—

Dear Sir,—I desire to draw your attention to what I think I may fairly describe as a wonderful instance of animal sagacity. During the recent severe frost a large number of birds and rabbits were fed every day in my garden. On Friday, for the first time, I noticed a fine hare, which, from its appearance, evidently felt the cold bitterly. I fed it, but shivering set in, and pained by its suffering (for I have a kind heart) I took it into the kitchen. Half-an-hour afterwards the cook came to tell me that the kitchen-maid was in hysterics. I went down and found out the reason—the girl had been frightened, when taking up a large jug which stood on the ground, to find the hare in it! The hare, poor thing, preferred a warm death to a cold existence, but, denied the possibility of human speech, had taken this graphic way of indicating its wishes. I have only to add that they were respected at dinner yesterday.

Stickiton Rectory.

Mem.—It would not be logical to conclude that Sir Arthur Sullivan is a good cricketer because of his capital scores.

An Expensive Call to Pay.—A Call to the Bar.

THE THIRD ACT.

An elevation and rockery in Früyseck's back-garden, from which—but for the houses in between—an extensive view over the steamer-pier and fiord could be obtained. In front, a summer-house, covered with creepers and wild earwigs. On a bench outside, Mopsa is sitting. She has the inevitable little travelling-bag on a strap over her shoulder. Blochdrähn comes up in the dusk. He, too, has a travelling-bag, made of straw, containing professional implements, over his shoulder. He is carrying a rolled-up handbill and a small paste-pot.

Sanitary Engineer Blochdrähn (catching sight of Mopsa's handbag). So you really are off at last? So am I. I'm going by train.

Mopsa (with a faint smile). Are you? Then I take the steamer. Have you seen Alfred anywhere about—or Spreta?

San. Eng. Bloch. I have been seeing a good deal of Mrs. Früyseck. She asked me to come up here and paste one of these handbills on the summer-house. To offer a reward for Little Mopsëman, you know. I've been sticking them up everywhere. (Busied with the paste-pot.) But you'll see—he'll never turn up.

Mopsa (sighing). Poor Spreta! and oh, poor dear Alfred! I really don't know if I can have the heart to leave him.

San. Eng. Bloch. (pasting up the bill). I shall not believe it myself until I actually see you do it. But why shouldn't you come along with me, if you are going—h'm?

Mopsa. If you were only a married man—but I have to be so careful now, you know!

San. Eng. Bloch. It tortures me to think of our two handbags each taking its own way; it really does, Miss Mopsa. And then for me to have to plumb all by myself. Though, to be sure, one can always get round the district surveyor alone.

Mopsa. Ah, yes, that you can surely manage alone.

San. Eng. Bloch. But it takes two to connect the ventilating shaft with the main drainage.

Mopsa (looking up at him). Always two? Never more? Never many?

San. Eng. Bloch. Well, then, you see, it becomes quite a different matter—it cuts down the profits. But are you sure you can never make up your mind to share my great new job with me?

Mopsa. I tried that once—with Alfred. It didn't quite answer—though it was delightful, all the same.

San. Eng. Bloch. Then there really has been a bright and happy time in your life? I should never have suspected it!

Mopsa. Oh yes, you can't think how amusing Alfred was in those days. When he distinguished himself by failing to pass his examinations, and then, from time to time, when he lost his post in some school or other, or when his big, bulky manuscripts were declined by some magazine—with thanks!

San. Eng. Bloch. Yes, I can quite see that such an existence must have had its moments of quiet merriment. (Shaking his head.) But I don't see what in the world possessed Alfred to go and marry as he did.

Mopsa (with suppressed emotion). The Law of Change. Our latest catchphrase, you know. Alfred is so subject to it. So will you be, some day or other!

San. Eng. Bloch. Never in all my life; whatever progress may be made in sanitation! (Insistently.) Can't you really care for me?

Mopsa. I might—(looking down)—if you have no objection to go halves with Alfred.

San. Eng. Bloch. I am behind the times, I daresay; but such an arrangement does not strike me as a firm basis for a really happy home. I should certainly object to it, most decidedly.

Mopsa (laughs bitterly). What creatures of convention you men are, after all! (Recollecting herself.) But I quite forgot. I am conventional myself now. You are perfectly right; it would be utterly irregular!

Alfred (comes up the steps). Is it you, Blochdrähn, that has posted up that bill? On the new summer-house!

San. Eng. Bloch. Yes, Mrs. Früyseck asked me to.

Alfred (touched). Then she does miss Little Mopsëman, after all! Are you going? Not without Mopsa?

San. Eng. Bloch. (shaking his head). I did invite her to accompany me; but she won't. So I must make my jobs alone.

Alfred. It's so horrible to be alone—or not to be alone, if it comes to that! (Oppressed—to himself.) My troll is at it again! I shall press her to stay—I know I shall—and it will end in the usual way!

Spreta (comes up the steps, plaintively). It is unkind of you all to leave me alone like this. When I'm so nervous in the dark, too!

Mopsa (tenderly). But I must leave you, Spreta, dear. By the next steamer. That is——Well, I really ought to!

Alfred (almost inaudibly, hitting himself on the chest). Down, you little beggar, down! No, it's no use; the troll will keep popping up! (Aloud) Can't we persuade you, dear Mopsa? Do stay—just to keep Spreta company, you know!

Mopsa (as if struggling with herself). Oh, I want to so much! I'd do anything to oblige dear Spreta!

San. Eng. Bloch. (to himself, dejectedly). She is just like that Miss Hilda Wangel for making herself so perfectly at home!

Spreta (resignedly). Oh, I don't mind. After all, I would rather Alfred philandered than fretted and fussed here alone with me. You had better stay, and be our Little Mopsëman. It will keep Alfred quiet—and that's something!

Mopsa. No; it was only a temporary lapse. I keep on forgetting that I am no longer an emotional Cuckoo heroine. I am perfectly respectable. And I will prove it by leaving with Mr. Blochdrähn at once—if he will be so obliging as to escort me?

San. Eng. Bloch. Delighted, my dear Miss Mopsa, at so unexpected a bit of good luck. We've only just time to catch the steamer.

Mopsa. Then, thanks so much for a quite too delightful visit, Spreta. So sorry to have to run away like this! (To Alfred, with subdued anguish.) I am running away—from you! I entreat you not to follow me—not just yet, at any rate!

Alfred (shrinking back). Ah! (To himself.) If it depends upon our two trolls whether——. (Mopsa goes off with Sanitary Engineer Blochdrähn.) There's the steamer, Spreta.... By Jove, they'll have a run for it! Look, she's putting in.

Spreta. I daren't. The steamer has one red and one green eye—just like Mopsëman's at mealtimes!

Alfred (common-sensibly). Only her lights, you know. She doesn't mean anything personal by it.

Spreta. But they're actually mooring her by the very pier that——How can they have the heart!

Alfred. Steamboat companies have no feelings. Though why you should feel it so, when you positively loathed the dog.

Spreta. After all, you weren't so particularly fond of him yourself; now were you, Alfred?

Alfred. H'm, he was a decent dog enough—for a mongrel. I didn't mind him; now you did.

Spreta (nods slowly). There is a change in me now. I am easier to please. I could share you with the mangiest mongrel, if I were only quite sure you would never again want to follow that minx Mopsa, Alfred!

Alfred. I never said I did want to; though I can't answer for the troll. But I must go away somewhere—I'm such a depressing companion for you. I shall go away up into the solitudes—which reminds me of an anecdote I never told either you or Mopsa before. Sit down and I will tell it you.

Spreta (timidly). Not the one about the night of terror you had on the mountains, Alfred, when you lost your way and couldn't find a policeman anywhere about the peaks? Because I've heard that—and I don't think I can stand it again.

Alfred (coldly and bitterly). You see that I have really nothing to fill up my life with, when my own wife refuses to listen to my anecdotes! Now Mopsa always—— What is all that barking down there in the town?

Spreta (with an outburst). Oh, you'll see, they've found Little Mopsëman!

Alfred. Not they. He'll never be found. Those handbills of yours were a mere waste of money. It is only the curs fighting in the street—as usual.

Spreta (slowly, and with resolution). Only that, Alfred. And do you know what I mean to do, as soon as you are away solitudinising up there in the mountain hotels? I will go down and bring all those poor neglected dogs home with me.

Alfred (uneasily). What—the whole lot of them, Spreta? (Shocked.) In our Little Mopsëman's place!

Spreta (firmly and decidedly). Every one. To fill Little Mopsëman's place. They shall dig up his bones, lie on his mat, take it in turns to sleep in his basket. I will try to—h'm—lighten and ennoble their lot in life.

Alfred (with growing uneasiness). When you simply detest all dogs! I don't know anyone less fitted than you to manage a Dog's Home. I really don't!

Spreta. I must fill the void in my life somehow—if you go and leave me. And I must educate myself to understand dogs better, that's all.

Alfred. Yes, that you would have to do. (As if struck with an idea.) Before you begin. Suppose I take up my big fat book on Canine Idiosyncrasy once more, eh? That would teach you how to purify and ennoble every poodle really scientifically, you know. Only you must promise to wait till I've got it done.

Spreta (with a melancholy smile). I am in no hurry Alfred. Only to write that you would have to remain at home.

Alfred (half evasively). Not necessarily. I might, of course—for a while, that is. But I shall have many a heavy day of work before me, Spreta, and you will see, now and then perhaps, a great slumberous peace descend on me as I toil away in my brown study—but I shall be making wonderful progress all the same.

Spreta. I shall quite understand that, Alfred. Oh, dear, who in the world's this?

[The Varmint-Blõk appears mysteriously in the gloom.

The Varmint-Blõk. Excuse me, Captin, and your sweet ladyship, but I just happened to drop my eye on one of those lovely little hand-billikins here, and took the liberty to step up, thinking it might so happen that you'd been advertising the very identical dawg what followed me home the other day. You may remember me passing the remark how wonderful partial dawgs was to me. So I brought him up on the chance like.

[He produces Little Mopsëman—in mufti—from a side-pocket.

Spreta. It is our Little Mopsëman! So you are not some supernatural sort of shadowy symbol after all, then?

The Varm.-B. (hurt). Now I ask you, lady—do I look it? Here's my professional card. And if you should have the reward handy—— (As Alfred pays him.) Five Rix dollarkins—correct, my lord, and thankee kindly. (As he departs.) You'll find I've learned that sweet little mongrel a thing or two; take the nonsense out of any rat in Norway now, he will. And just you ask him to set up and give three cheers for Dr. Ibsen—that's all!

[He goes out, chuckling softly.

Alfred (holding out Little Mopsëman at arms' length). H'm; it will be a heavy day's work to purify and ennoble this poodle after all he has been through, eh, Spreta? I think, as you seem to have developed quite a taste for such tasks, I shall allow you to undertake it—all by yourself.

Spreta (turns away with her half-teasing smile). Thanks!

THE END.

"Before you finish your whiff and depart to dress for dinner," quoth the Baron, "just read through Mr. Escott's article in the Fort-nightly." If you lived in Literary Bohemia many years ago, it will revive pleasant memories, and if you didn't, it will interest those who did with whom, in conversation at dinner, you can start the subject. Bohemia exists always; only, as Mr. Laudator Temporis Acti will, of course, sing, it was at its best in

"The days when we went gipseying

A long time ago!"

"Glad to see Mr. Escott's pen at work again," quoth the kindly

Kindly Gentleman (from True Blue Club). "And what has brought you to this deplorable condition? Drink?—Gambling?"

Gentleman of the Pavement (spotting his man). "No, indeed, Sir; my misfortunes are entirely attributable to Free Trade, Monometallism, and the Death Duties."

[Immediate relief on a generous scale.

An awful night! I do believe it's snowing!

Who from his "ain fireside" would wish to roam?

Only a fool would go—and yet I'm going—

To Mrs. A.'s At Home!

The burden of At Homes! The bore of dressing!

I must be wielding razor, brush, and comb

(The snow has almost stopped—Come, that's a blessing!)

For Mrs. A.'s At Home.

Why am I going? Well, to me the reason

Looms large and clear as Paul's cathedral dome:

The reason's—Nancy, whom I met last season

At Mrs. A.'s At Home.

Hi, hansom! Off we go! Although sweet Nancy

Since then has vanished like a fairy gnome,

Yet I shall see her (sweet conceit) in fancy

At Mrs. A.'s At Home.

"Thankee, my lord!"—he's earned that extra shilling,

We've come along, the horse is flecked with foam—

Slowly upstairs I go, the rooms are filling

At Mrs. A.'s At Home.

Then—why, good heavens! No! It isn't fancy!—

"Can it be you? I heard you were in Rome.

Just fancy meeting you"—the real Nancy!—

"At Mrs. A.'s At Home!"

To-night and Nancy—rhyme excuses fiction—

Might, if I sang them, fill a ponderous tome:

A perfect night! I breathe a benediction

On Mrs. A.'s At Home!

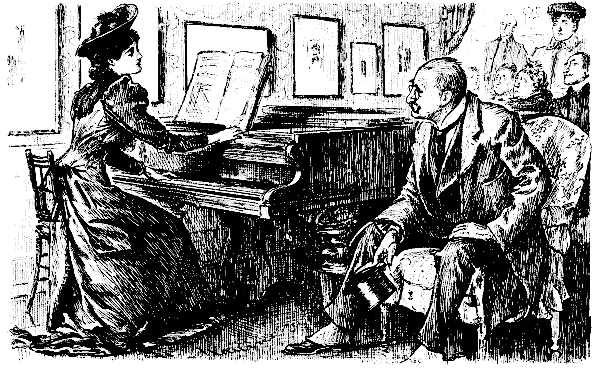

"Ach! Dat is a putiful Zong, Laty Peacocke, and you bronounce Cherman very vell—pot vy do you blay ze Aggombaniment in B Natural?"

"The Song's written in B Natural, Herr Maestro."

"Ach zo! Zen vy do you zing ze Meloty in B Vlat?"

"Oh, really, Herr Maestro! I don't pretend to be a Professional, you know. I only sing just to please my Friends!"

His task demands sinews and nerves

As tough and as supple as hickory;

He's done if he stumbles or swerves,

This Titan-like pet of Terpsichore.

What wonder he seems strung on wires

From the tip of his trunk to his very toe,

Performing a feat which requires

The joint skill of Blondin and Cerito?

Ah, Jumbo! stretch balance-wise tail-whisp and trunk,

For you'll never get through if you fumble or funk.

Scarce "light" is his ponderous form,

And his footing is hardly "fantastic."

It makes one grow nervous and warm

To watch this colossus gymnastic.

Can't "trip it,"—although he may trip,—

His tentative toes throb and tremble;

He waggles his tail like a whip:

There's danger, but he must dissemble;

And though he an imminent downfall may dread,

Must walk o'er the bottles with confident tread.

For Titan to dance on a tub

As steady as—Cecil's majority,

Is easy, but—oh! there's the rub—

The bottle-trick has the priority.

It comes first "by special request,"

And there isn't a chance of evasion.

Poor Jumbo must fain do his best,

Though he'd rather postpone the occasion.

Titan-Turreydrop now on St. Stephen's new floor

Can't choose his own figures or steps any more!

There are plenty of "turns" he'd prefer,

And numbers of tricks he'd do better.

His "Gradation Dance" made a great stir.

But, alas, for the goad and the fetter!

As his enemies pipe he must dance,

To public opinion he's plastic;

And so, with a dubious glance,

He essays this untried "Light Fantastic."

From bottle to bottle slow picking his way,

As an overture forced to the programme he'd play!

(Communications Intercepted in Transit.)

From a School Boy to his Younger Brother.—My dear Bobbie,—How are you getting on at home? We are having a high old time at Swishers'. All the pipes frozen, and no water to be got anywhere! And it is so comfortable!

From a Firm of Coachbuilders to one of their Customers.—Dear Sir,—As there is every reason to believe that the present severe weather will last for a considerable time, may we have the honour of building for you a sleigh? We shall be pleased to have the vehicle ready for you in the course of a month, or at the latest six weeks. Should the weather break in the meanwhile, it will be available under similar conditions next year or the year after. It will also be quite possible to carry the sleigh to Siberia, where it will at all times be found, not only a luxury, but a necessity. We are, dear Sir, awaiting your esteemed order,

From a Dramatist to an Intimate Friend.—My dear Bill,—Thank you for the marked paper you have forwarded to me. But the statistics are misleading. Talk about this being the greatest frost on record! You would not say so if you had been present at the first night of my play, The Force of Circumstances.—Yours gloomily,

From a Celestial Official to the Public.—Poor creatures,—You think you have seen the worst of the winter! Just like your presumption! When I can manage a sky salad of rain, fog, snow, thunderbolts and sunshine all mixed together in the course of ten minutes and set it before a London audience in the midst of a modern January, don't you be too sure of anything! Wait, my melancholy maniacs, and you shall see what you may possibly live to witness.—Yours disrespectfully,

"There is an exception to every Rule."

'Tis the voice of the Oyster,

I heard him complain,

"You have woke me too soon,

I must slumber again.

I'm fat and quite well—

Have no doubt on that head—

But say that I'm ill,

And do leave me in bed.

"Just a little more sleep,

Just a little more rest;

How sweet, my dear friends,

I shall be at my best!

Oh, let me repose

Say till May—May the one'th—

When, as everyone knows,

There's no 'R' in the month!"

(And a Remonstrance.)

This day to yow, dere ladye, wol I schowe

Myn hertes wissche—cum privilegio.

Of alle seintes nis ther more benigne

To man and mayden noon thanne Valentyne;

Sith everych yeer on that swete seintes day

Man can to mayden al his herte displaie

(Bye Cupid arwes smit in sory plighte—

One grote al pleyn, and twayn ypeinted brighte).

Then wol I mak my playnte, so maist ye knowe

Yon whele, dere ladye, don me mochel wo.

Algates I greve, whanne that scorchours I mete

That riden reccheles adoun the strete:

I praie, bethynke yow, swiche diversioun

Ben weel for mayde of mene condicioun,

But ladye fayre in brekes al ydighte

Certes meseems ne verray semelye sighte.

Swiche gere, yclept "raccionale," parde,

Righte sone wol be the dethe of chivalrye;

And we schal heren, whanne that it be dede,

The verdite, "Dethe by—Newe Womman-hede."

Heede then theffect and end of my prayere,

Upyeve thy whele, ne mannissche brekes were,

Contente in graces maydenlye to schyne,

So mote ye be myn owen Valentyne.

"Just the weather for receiving a sharp retort," observed our laughing Philosopher, with his snow-boots on. Naturally his friend wished to know why. "Because," replied Dr. Chuckler, "with the temperature below zero, no one can object to having a wrap over the knuckles." Then away he went merrily over the unartificial ice on the Serpentine.

[À propos of cropping dogs' ears, a letter from Sir F. Knollys appeared last week in the Stock-Keeper, informing an inquirer that H.R.H. had never allowed any dog of his to be "mutilated," and was pleased to hear that "owners of dogs had agreed to abandon so objectionable a practice."]

We humbly thank the Prince of Wales,

Henceforth we'll keep our ears and tails

Intact, and shall not dread the shears

Which used to crop our tails and ears.

As novelists in magazines,

And writers of dramatic scenes,

By editorial scissors caught

Object to have their tales cut short,

So we, gay dogs: for gay we'll be,

Henceforth the best of company!

Convivial we around a joint,

And not a tail without a point.

Not cropped like convicts from the gaols!

"Ear! Ear!" and "Bless the Prince of Wales!"

Musical Note.—The title of a song, "Come where the Booze is Cheaper," has become widely known owing to a recent trial. We believe we are correct in saying that this song about "the Booze" is not published by the well-known firm of "Boosey & Co."

(By Mr. Punch's own Short Story-teller.)

I.—THE PINK HIPPOPOTAMUS. (continued.)

I ought to mention that the Ranee, the aunt of my darling Chuddah, was as susceptible as she was haughty and ferocious. During my stay in the capital I had had several interviews with her, and I could not disguise from myself—why should I?—that she regarded me with no common favour. Indeed, she had taken the somewhat extreme step of informing me semi-officially (so that she might afterwards, if necessary, be at liberty to disavow it) that, if I would only consent to marry her, she would undertake to poison Sir Bonamy Battlehorn. I should thus be elevated not only to the supreme command of the British forces, but also to the throne of the Diamond City. But I withstood her blandishments, captivated, as I was, by the tender maidenly loveliness of Chuddah, and the wicked old woman had sworn to have her revenge. I had, of course, a staunch ally in her brother, the Meebhoy, but in his disabled condition, that veteran warrior could be of little real use to me. Still he knew of my love for his niece Chuddah, and, knowing all my worth, he had already consecrated with his blessing our prospective union. On this particular evening I found Chuddah in her cosy little boudoir alone, save for the presence of her stout and comfortable old Ayah or Nana. The darling girl sprang up as I entered the room and threw herself into my arms in a passion of affection. I gently disengaged her arms from about my neck, and proceeded, as best I could, to inform her that I had come to take leave of her for a short time. Her grief was terrible to witness.

"Oh, my own!" she sobbed (I translate her language); "my very, very own, my tall and gorgeously beautiful son of the fair-faced English, my moon of radiant splendour, my star of aspiring hope, say not thou art come to say farewell, say it not my dearest Duffadar, for Chuddah cannot bear it."

"But, my darling," I urged, "duty calls, and Chuddah would not have her Orlando flinch."

The beautiful girl admitted the force of this appeal and a renewed scene of affectionate leave-taking took place. Suddenly the Ayah, who up to this moment had been dozing in her arm-chair, rose, and holding up a warning hand said, "Hist!"

We did so, alarmed by the impressive air of the good old nurse.

"Hist! What is that sound?"

I listened intently, and sure enough heard a faint tapping, proceeding apparently from the floor under my feet.

"I suspect treachery," continued the Ayah hurriedly. "'Twas only yester morn I saw Youbyoub scowling at us as we passed by on our early walk. Oh, beware, my lord, of Youbyoub."

This Youbyoub, I ought to say, was the young and bloodthirsty Prince of the Lozen Jehs, a tribe of wild warriors from the north. Betrothed to the beautiful Chuddah at an early age, he naturally viewed with hatred the advent of one on whom nature had bestowed her favours so bountifully, and who was bound, therefore, to make himself dear to Chuddah. I knew he detested me, but I had hitherto scorned him. I was now to discover my mistake.

Scarcely had the words left the Ayah's lips when a loud rumbling made itself heard: the floor seemed to heave in one terrific crash, there was a horrible explosion, and before I had time to realise what had happened we three, Chuddah, the Ayah and I, were being propelled upwards into space at the rate of at least a thousand miles an hour.

(To be continued.)

(Being an unflattering Tale of Hope.)

"There's ingratitude for you," said the Rag Doll marked "three-and-six."

"Where?" I asked, rousing myself from my meditation on my tambourine and drumsticks.

She pointed to a figure which had just been placed in the second row. He was dressed very smartly in a red coat trimmed with tinsel. But he had an unmistakeable air of second-hand.

"I made that man," said the Rag Doll, "and now he cuts me dead before them all! It's atrocious! Why, but for me he would have been bought for five shillings, and would have been the property of the plainest child in London."

"Not that," I pleaded; "think of——"

"Well, very plain, anyhow. I was ready to bow to him. I almost did."

"In fact, you did."

"I didn't. I declare I didn't."

"Oh, well, you didn't, then. It only looked like it."

"He first came here," said the Rag Doll, "three weeks ago. At that time he was—quite presentable. He was everything he should be. He stood firmly on his legs without toppling over, and had his cocked hat firmly fixed on his head. And his sword——"

"Where did he wear that?"

"He carried that, Mr. Whyte Rabbit. Don't be silly. Wore it by his side, you know, and had epaulettes, too."

"He has changed outwardly at least."

"Yes, I know; well, I did that. I took him in hand, and I just taught him, and now——!"

"Yes, I know. But how did you teach him?"

"I fell upon him. I knocked him from his perch, and in the fall broke his wretched sword with my own weight!"

"What very arbitrary distinctions you draw!"

"I don't know what you mean. I do like a plaything to be smart, anyhow. Don't you, Mr. Whyte Rabbit? You don't play your tambourine properly. Now I shall take you in hand." And she slipped toward me.

"I prefer to use my own drumsticks. I can make enough noise in the world without extraneous assistance."

"How silly you are. I don't want to see you spick and span, as if you were ready to be given away with a pound of tea."

"Still, I don't see why I should alter my drumming——"

"Oh, you are stupid! Of course you admire me!"

"As he did. I see."

"You seem to think that very funny."

"Not a bit."

"Then we are agreed. There is not much fun in our talk."

"You're always so observant. There is not. Short sentences."

"And a soupçon of the unexpressed."

"Which means so very much. When understood?"

She swayed from one side to the other. There was an easterly wind blowing full from the open north door of the Arcade. I looked unhappy. There is an understanding that I shall look unhappy except when I am beating my tambourine with my drumsticks.

"What was I saying before—before you—you know—oh, about our talk, of course, being rather flat and not very profitable?"

"I have no more to say," said I.

"But he was very angry, for in my fall I broke his nose."

"I have a bad nose, too."

"What's the matter with your nose?" asked the Rag Doll smiling.

"The joint is injured and some of the fur has come off my head—in fact, I am as bald as the ball of an eighteen-penny bagatelle-board," and I contrived (with the assistance of the draught) to roll away a little.

"You find carriage exercise good for your poor nose?" bubbled the Rag Doll.

Now when the Rag Doll bubbles—an operation which includes a sudden slipping down the shelf, the lighting up of glass eyes, a dart of a kid-covered arm with vague fingers, and a gurgling gust of slipping drapery—I am in the habit of ceasing to argue the question.

"Well, your fall will not damage the machinery. You have nothing to do but look—you understand. While I have to beat my tambourine with my drumsticks."

"But I won't fall upon you. I reserved my weight for the warrior that was once valued at five shillings and is now reduced to half-a-crown."

"Because you—educated him?"

"Yes. And now he cuts me dead! Why he will be bought by some one with poorer means, and will be all the more appreciated."

"Of course you did not care for the impoverished soldier?"

"Not a little bit."

"Nor any one else?"

"Oh, well——"

Then I repeated the question several times in such a way that if written a line of space would be given to every query. It was a notion of Alexandre Dumas père to do the same in his novels. And his sentences were worth a franc a line. At least, so it has been related.

The Rag Doll looked straight in front of her.

"Hullo, old chappie," I said to myself; "where did you spring from?"

"Why, it's my proprietor!" said the Rag Doll, ceasing to bubble, and becoming all propriety.

The toy merchant took no notice of what we had said. How could he when our voices were inaudible? But he dusted us with his feather-brush, and left us ready for another dialogue. For all that the Rag Doll didn't think he was coming just then. No more did I.

(An Unionist's Forecast.)

[The measures in the Government Programme are ten in number (says the Westminster Gazette), viz., 1, Irish Land Reform; 2, Welsh Disestablishment; 3, Local Veto; 4, One Man, one Vote; 5, Charging Election Expenses on Rates; 6, Unification of London; 7, A Factory Bill; 8, Establishment of Conciliation Boards; 9, Completion of Scottish County Government; 10, Relief of Crofters.]

Ten little measures hung upon the line,

One went up to the Lords, and then there were nine.

Nine little measures asked their turn to wait,

One shoved in to the front, and then there were eight.

Eight little measures promising us heaven,

One met a Witler host, and then there were seven.

Seven little measures crossing the Lords' Styx,

One of 'em tumbled in, and then there were six.

Six little measures a-trying to look alive,

One was talked clean off his head, and then there were five.

Five little measures on the Session's lea shore,

One saw Gog and Magog there, and then there were four.

Four little measures as weak as weak could be,

One o'er an Amendment tripped, and then there were three.

Three little measures a-looking precious blue,

One met K-r H-rd-e's frown, and then there were two.

Two little measures a-trying a last run,

One of them had "special Scotch," and then there was one.

One little measure then aspired to "cop the bun,"

H-rc-rt coolly chucked it up, and then there were None!

[And then the Government went out, and Unionists had fun!

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TOBY, M.P.

House of Commons, Tuesday, February 5.—Almost thought just now we were going to have another Bradlaugh business. House crowded; Members on all sides eager for the fray. At the bar, closely packed, stood group of newly-elected Members. Seen some of them here before. Broadhurst back again after what seems years of exile. Elliott Lees, deep in thought as to where he shall next go for his groceries in Birkenhead, in centre of the group. The new Solicitor-General, our old friend Frank Lockwood, like a tall maple (not Sir Blundell), lifts his head and smiles.

"Members desiring to take their seats will please come to the table," says the Speaker.

Broadhurst, in the van, sprang forward. Had made a fair start when Henry James, watchful in aerie on corner bench below gangway, leaped to feet and proposed to discuss the legality of situation. Objection founded on abstruse mathematical problem. Two writs had been moved to fill vacancies in the representation of Leicester. There had been only one election. There should, Henry James argued, have been two. Consequently, election invalid; the two new Members for Leicester not Members at all, only strangers, intruders across the bar, liable to be whipped off in custody of Sergeant-at-Arms.

Here was a pretty prospect for opening of Session to which Squire of Malwood had come with his pocket full of Bills! Sergeant-at-Arms glanced uneasily at Broadhurst retreating before interruption. What if repetition of the old process were imminent? Were there to be more carpet-dances on floor of House through summer afternoons, as was the wont of Captain Gosset pirouetting to and from the Mace, House not quite sure whether he was clutching Bradlaugh or Bradlaugh him? Then the merry scenes in the outer hall, Bradlaugh fighting at long odds, finally thrust down the staircase, breathless, his coat torn, his stylographic pen broken. Broadhurst a stone or two lighter than Bradlaugh. But was he equally nimble-footed? Certainly he had not yet acquired the practice which in the second Session of the controversy enabled Bradlaugh and the Sergeant-at-Arms to advance, retire, chasser, and clasp hands across the middle, in perfect time.

But a great deal has happened in the fifteen years that have sped since, from a corner seat on the side of the House facing Henry James, Drummond Wolff rose, and with emphatic gesture barred Bradlaugh's progress to the table. By striking coincidence that strange chapter in Parliamentary history, opening by chance accident and leading to stirring consequences, was finally closed this very night, when Akers-Douglas moved writ to fill vacancy created in South Paddington by death of "Right Hon. Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill, commonly called Lord Randolph Churchill."

Henry James had not concluded his sentence when Speaker interposed with ruling that there must be no interference with Members desiring to take their seats. So incident closed. Members for Leicester sworn in. Broadhurst, in exuberance of moment, made as though he would publicly shake the hand the clerk held out to take writ of return. But Reginald Francis Douce Palgrave not made K.C.B. for nothing. "The writ, the writ!" he hoarsely murmured, waving back the friendly hand. Broadhurst hastily produced document from breast-pocket, and thus fresh scandal was averted.

Business done.—Address moved.

Wednesday.—Exceptional interest in this afternoon's proceedings in view of circumstance that Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (Knight)—what was it Grandolph said about mediocrity with double-barrelled names?—would appear in his new character as Silomio. Title conferred during recess by delegates from Swaziland. Curiosity quickened by report that début would be made in character. Yesterday we had mover and seconder of Address in velvet suits with silver buttons and brands Excalibur at their side. Why no Silomio in the native dress of the nation that has adopted him? Some disappointment when he turned up in ordinary frock-coat. Understood that weather responsible for this. Swazi morning dress picturesque, but with nine degrees of frost in Palace Yard a little inadequate, especially for a beginner.

Even in commonplace English dress Silomio made a striking figure as he stood at the table, and belaboured it for "Swaziland, my Swaziland." Looked at times as if he were going to leap over, and seize by the throat Sydney Buxton provokingly smiling on the other side. Last week's handkerchief hanging out from his coat tail pocket, in liberal measure though crumpled state, lent a weird effect to back view, not interrupted by inconvenient crowding on front Opposition Bench. Odd how Silomio's colleagues in late Ministry find business elsewhere when he rises to orate.

Business done.—Talking round Address.

Thursday.—Rather painful scene in House to-night. Chaplin resuming debate on Address led its course gently by the still waters of bimetallism. Somehow that a subject that has never quite entranced attention of frivolous Commons. It works certain subtle spell upon them. At clink of sovereign and shilling between argumentative finger and thumb they slink away. So it was to-night whilst Chaplin spoke. Faithful among the faithless found was Jemmy Lowther. He sat attentive beside the orator with an expression of profound wisdom, unmitigated by boyish habit of keeping his hands in his trouser pocket, not without suspicion of furtively counting his marbles or attempting to open his knife with the fingers of one hand.

Jemmy and Chaplin rank amongst oldest boys in the school. One took his seat for mid-Lincolnshire in December, 1868; saw the rise to supreme power of Mr. G. and, with some intervals, suffered it up to the end. The other rode in triumphantly from York one July day in 1865. Thus their united Parliamentary ages if fifty-seven, a record hard to beat. Shoulder to shoulder they have, through all this time, resisted attacks on British Constitution. Now, suddenly, publicly, in eye of the scorner, came sharp parting of the ways.

Chaplin viewing state of things depressing industrial communities admitted it was very bad. Mills closed, mines empty, ship-building yards silent, workmen starving. Only one thing would save the State—Bimetallism. "Is there anyone," said the orator with magnificent wave of arm round desolate benches; "who has any other suggestion to make for the salvation of these industries?" Then up spoke Jemmy Lowther. "I have," he said with final tug at the blade of the knife hidden in his pocket.

Chaplin stood aghast. Could it be possible—his own familiar friend? He turned, looked down on him, gasping for breath. Then in a hollow voice he added, "What has my right hon. friend been doing all this time? Why doesn't he make his proposal?"

Here was an opening for apology, recantation, or at least, submissive silence. But Jemmy evidently gone to the bad; got the bit between his teeth and bolted. "I've made it over and over again," he growled, thinking resentfully of his much crying in the wilderness for that blessed thing Protection. Ribald House roared with laughter. Chaplin, cut to heart, avoided repetition of painful incident by bringing oration to early conclusion.

"Let's put this matter to practical test, Toby," he said. "Come along with me, and we'll consult the Unemployed."

Not far to go. On Westminster Bridge a hollow-cheeked man leaning over low wall stared at ice-floes silently gliding down with the tide. "My good man," said Chaplin, "you look unemployed, and I daresay you're hungry. Now, in order to put you straight, which would you rather have, Bimetallism or Protection?"

"Well, if you don't mind, master," said the Unemployed huskily, "I'd like a chunk o' bread."

"Ah!" said Chaplin, "these people are so illogical." And he gave him half-a-crown.

Business done.—Drifted into debate on Bimetallism. Business can wait.

Friday.—Squire of Malwood left sick room to take part in debate and division on Jeffreys' Amendment to Address. Self-devotion dangerous on foggy, frosty night. But the result worth it, at least for crowded House that heard the speech. Best thing of the kind done in House since Dizzy's prime. Squire evidently profited by necessity for rapidity of composition. The sharpest barbs aimed at quivering figure of Jokim sitting opposite.

"Wot's this he means about stealing my clothes when I was bathing?" said Hardie, with puzzled look. "With thirteen degrees of frost under the fog I Don't Keir less than ever about bathing. As for my clothes, they might suit Prince Arthur, but they wouldn't quite fit him."

Business done.—Amendment to Address defeated by twelve votes in House of 534 Members.

Literature and Philosophy Class for Female Students.

Master. What is the analogy between Hamlet and Mirabeau?

First Girl (rising). I know. (Pause, then suddenly, and with determination.) Mirabeau didn't get on well with his father, and Hamlet was at daggers drawn with his uncle.

[Reseats herself triumphantly.

Resetting an Old Saw.—The descriptive writer in the Daily Telegraph, giving his account of the opening of Parliament, observed that "Hypercritics have combated the generally accepted axiom that one pea entirely resembles another," and he went on to show how one parliamentary crowd resembled any other parliamentary crowd at the initial ceremony. Assuming therefore this similarity, suppose we re-set the old saw, and say, "As like as two M.P.'s."