THE CALL OF THE EAST

THE

CALL OF THE EAST

A ROMANCE OF FAR FORMOSA

BY

THURLOW FRASER

Illustrated

TORONTO

WILLIAM BRIGGS

Copyright, 1914, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

To

Her who shared my life and

suffered in the Beautiful Isle

FOREWORD

In every port of the Orient the outposts of the restless, aggressive West touch the lines of the impassive East. Consuls, military and naval officers, merchants, missionaries force the ideas and ideals of the West upon the reluctant East. Many of these representatives of western civilization are true to the high standards of the nations and religions from which they come. Many others fall to the level, and below the level, of those they live among.

This story is an attempt to picture this life where the East meets the West, in one small port and for the one short period covered by the Franco-Chinese War of 1884-85. Of the characters one, Dr. MacKay, is unhesitatingly called by his own name. Sergeant Gorman and one or two others of the subordinate figures are drawn from life. The rest, including the principal actors, are purely imaginary.

T. F.

OWEN SOUND, ONT.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

They came over the last bluff . . . . . . Frontispiece

Sinclair threw off his coat, rolled up his sleeves, and went to work

A yell from one of the Chinese attracted the attention of Sinclair and Gorman

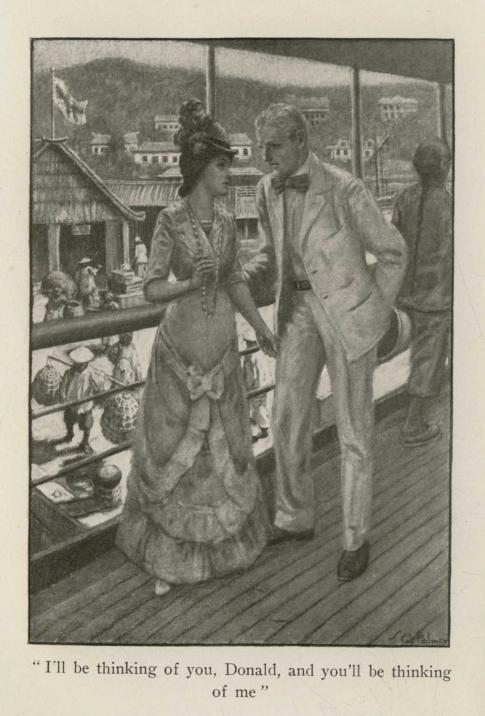

"I'll be thinking of you, Donald, and you'll be thinking of me"

I

STORM SIGNALS

"Pardon me, Miss MacAllister! Is there any way in which I can be of service to you?"

The young lady addressed turned quickly from the deck-rail on which she had been leaning, and with a defiant toss of her head faced her questioner. A hot flush of resentment chased from her face the undeniable pallor of a moment before.

"In what way do you think you can be of service to me, Mr. Sinclair?" she demanded sharply.

"I thought that you were ill, and——"

"And is it so uncommon to be sea-sick, or is it such a dangerous ailment, that at the first symptom the patient must be cared for as if she had the plague?"

"Perhaps not! But I am told that it is uncomfortable."

There was a humorous twinkle in his eyes. At the sight of it hers flashed, and the flame of her anger rose higher.

"From that I am to understand, Mr. Sinclair, that you are one of those superior beings who never suffer from sea-sickness."

"I must confess to belonging to that class," he replied good-humouredly. "I have never experienced its qualms."

"Then I abominate such people. They call themselves 'good sailors.' They offer sympathy to others, and all the while are laughing in their sleeves. They are insufferable prigs. I want none of their sympathy."

"But, Miss MacAllister, you misunderstand me. I am not offering you empty sympathy. I am a medical doctor, and for the present am in charge of the health of the passengers on this ship."

"Then, Dr. Sinclair, I am not in need of your care. I never yet saw a doctor who could do anything for sea-sickness. Their treatment is all make-believe. They know no more about it than any one else. I do not propose to be the subject of experiments. Good-evening."

She was again leaning on the rail, in an attitude which belied her defiant words.

"Good-evening," replied the young doctor, as he turned away with a scarcely perceptible shrug of his shoulders, and with an expression of mingled amusement and annoyance on his face. A low chuckle of laughter caught his ear. He was passing the cabin of the chief officer, and the door stood open.

"What is the matter with you, Mr. McLeod?" he asked, the shade of annoyance passing from his face, and a good-humoured laugh taking its place.

"Come in and close the door."

"You heard what she said?"

"Yes. How do you feel after that, doctor?"

"Withered; ready to blow away like a dry leaf in autumn!"

"You look it," laughed the mate, as he glanced admiringly at the big, handsome man who seemed to take up all the available space in the little cabin, and who was laughing as heartily as if some one else had suffered instead of himself.

"Isn't she a haughty one?" continued the chief.

"Who is she, anyway? The captain made us acquainted. But you know he doesn't go into particulars. She was Miss MacAllister. I was Sinclair. That was our first encounter. You witnessed the second."

"Her father is senior member of the big London firm of 'MacAllister, Munro Co., China Merchants.' They have hongs at every open port on the China Coast. He is making an inspection of all their agencies and has brought his wife and daughter along for company. Being a Scot, he likes to keep on good terms with the Lord, who is the giver of all good gifts. So he is mixing religion with business. In the intervals between examining accounts and sizing up the stock in their godowns, he is visiting missions, seeing that the missionaries are up to their pidgin, and preaching to the natives through interpreters."

"Easy seeing, McLeod, that you're a Scot yourself, or the son of a Scot, from your faculty of acquiring things. Where did you get all this about the MacAllisters? They joined us only this afternoon at Amoy."

"Oh, yes! But they were with us from Hong-Kong to Swatow last trip. You missed that, doctor, by going over to Canton. Miss MacAllister and I got quite chummy. Bright moonlight; dead calm; too hot to turn in and sleep! So we just sat out or strolled up and down nearly all night. If you had been there, I should have had no show. See what you missed."

"If what I got to-day be a fair sample of what I missed last trip, you're welcome to it."

The mate laid back his head and laughed with boyish glee at the rueful look which came over his friend's countenance, at the mere memory of the stinging rebuff he had suffered.

"Do not imagine that your lady friend is always in the humour she showed to-day, doctor. She is pretty sick, and for the first time, too. She told me before what a good sailor she was. Never missed a meal at sea! Never had an inclination to turn over!"

"Did she say that, McLeod? That she was a 'good sailor'?"

"Yes."

"The vixen! And then you heard the way she has just soaked it to me for being a 'good sailor.'"

McLeod shook with laughter.

"Don't be too hard on her, doctor. She has got it good and plenty this time, and she's disgusted with herself, disgusted with the sea, the boat, and everything and everybody connected with them."

"She doesn't hesitate to express her disgust," replied the doctor. "I blundered upon her at an unlucky moment and received the full contents of the vials of her wrath."

"Never mind; she will soon get over this. Then she will be quite angelic."

"I guess she got some Chinese chow at Amoy, which didn't agree with her."

"Perhaps! But it doesn't need any chow to turn over even good sailors on a sea like this. The Channel can be dirty when it likes. This is one of the times it has chosen to be dirtier than usual."

The two young men had stepped out of the mate's cabin and were leaning on the rail looking at the turbulent sea through which they were steaming. The coast-line had already faded out of sight in the gathering gloom, but away to the northwest a great, white light winked at slow intervals of a minute. The tide was setting strongly in a southerly direction, and the ship was breasting almost directly against it. The southwest monsoon meeting the tidal current, and perhaps several other wayward and variable ocean streams which whisk and swirl through that vexed channel, was kicking up a perfect chaos of broken waves. Through this choppy turmoil the Hailoong ploughed her way, all the while pitching and rolling in an exasperating fashion, no two successive motions of the ship being alike. None but seasoned sailors could escape the qualms of sickness in such a sea.

"It certainly is nasty enough," said the doctor; "and the appearance of the weather does not promise much improvement."

"The storm signals were hoisted as we weighed anchor," replied McLeod. "They indicated a typhoon near the Philippines, but travelling this way. The captain thought that we could make the run across before it caught us. But if we don't see some weather before we cross Tamsui bar, I'm no prophet."

"Seven bells! Guess I had better polish up a bit for dinner."

"Don't throw away too much labour on yourself, Sinclair. She'll not appear at table this evening."

"She must have made considerable impression on you, Mac, from the frequency with which your mind recurs to her," retorted Sinclair, as the two separated to make hasty preparations for dinner.

II

A LULL

There were not many at dinner that evening. The Hailoong never had a very heavy passenger list. Her cabin accommodation was limited. On this trip half of the small number of passengers were in no humour for dinner.

When Dr. Sinclair entered the saloon, the chief officer, McLeod, was already at the table. His watch was nearly due, and he did not stand upon ceremony. Presently Captain Whiteley came in, and with him a tall, broad-shouldered man of past middle age. Sinclair had barely time to note the high, broad forehead, and the square jaw, clean shaven except for a fringe of side-whiskers, trimmed in old-fashioned style, and meeting under the chin, before the captain introduced him.

"Mr. MacAllister, this is Dr. Sinclair, a Canadian medical man, spying out the Far East, and incidentally acting as our ship's doctor."

"I am pleased to make your acquaintance, Dr. Sinclair. I have been in your country, and have a great respect for the energy and progressiveness of your countrymen."

"I am glad to know that you have visited Canada, Mr. MacAllister. It seems to me that most British business men and British public men are lamentably ignorant of Britain's dominions beyond the seas. It's refreshing to meet one who has visited these new lands and knows something of their possibilities."

"It must be acknowledged that too many of us in the British Isles are insular and conservative in our ideas. But I have always felt that even in the matter of trade we cannot make a success, unless we know the people and the wants of the people with whom we do business. Our firm's largest foreign trade is with China, and this is my fourth visit to the China Coast. But we have interests in Canada also, and in connection with them I have spent some months in the Dominion."

"I am quite sure that your interests there will grow. It is a great country. There is practically no limit to its possibilities. Even the Canadians themselves are only now discovering that."

"With such a country, and with such possibilities in it for a young man, I am surprised, Dr. Sinclair, that you have forsaken it to seek your fortune on the China Coast."

"Seeking one's fortune, in the ordinary meaning of that phrase, is not the only thing worth living for, Mr. MacAllister. If that were the main object in life, I should have remained in Canada."

The keen grey eyes of the successful business man searched the young doctor's face, as if they would read his very thoughts. But Dr. Sinclair did not answer their questioning gaze, nor volunteer any explanation of his statement.

"Dr. Sinclair thinks with you," broke in Captain Whiteley, "that a man is better of seeing life in different parts of the world, even though he may end up by finding a snug harbour in some out-of-the-way corner."

"Yes," replied the merchant, "that is wise, if he can make any use of the experience gained."

"And I think that the doctor is nearly as much interested in missions as you are, Mr. MacAllister, judging from the way he visits them and studies them at every port."

"Is that so, Dr. Sinclair?" The keen eyes were again reading his face.

"I am interested in anything which proposes to make this old world better, and to help the men who are in it. That's why I chose medicine as a profession. I like to see things for myself. That's why I visit missions."

"And what are your conclusions?"

"I have hardly come to any conclusions yet. I have been only a few months on the Coast. Tourists and newspaper correspondents know all about the Far East after spending ten or twelve hours at each of the ports touched by the big liners. I am not a genius. I cannot form conclusions so rapidly. But here is a fellow-countryman of mine who knows more of missions now than, in all probability, I ever shall know."

As he was speaking a man had entered the dining saloon who would have attracted attention anywhere. It was not his dress or his stature which would have caused him to be noticed. Like the rest he wore a close-fitting suit of white drill. He was of barely middle height, though well-knit, wiry and erect. But the quick, nervous movements, the piercing dark eyes, which seemed to take in with one swift glance everything and everybody in the room, betokened the fiery energy of the soul which burned within. The high forehead, a trifle narrow perhaps, and the straight line of the mouth, with its firmly-closed lips, indicated intensity of purpose and determination. A long black beard flowed down on his chest, contrasting sharply with the spotless white of his clothing.

"Mr. MacAllister, have you met Dr. MacKay?"

"I have not had that pleasure. Is this MacKay of Formosa?"

"I am MacKay."

"It is a great pleasure to me to meet you. I have heard so much of your work."

"I hope it may have been good."

"What else could it be? I am told that it is marvellous what you have accomplished in so short a time and almost alone."

"All have not that opinion of my work."

"All who spoke of it to me had that opinion. If what they told me is true, as I believe it is, how could they think otherwise?"

"Different men have different methods. So have different missions. Some can see no good in any but their own. My methods differ from those of others. They have not approved themselves to many of my seniors in the mission fields of China."

"I shall be glad to study your methods and see your results for myself."

"You shall have the opportunity."

The little group of officers and passengers were ere this seated at the table. In addition to those already mentioned there was the chief engineer, Watson, a Scot from the Clyde. There was also a passenger, a tea-buyer from New York.

The latter sat opposite Dr. MacKay at the mate's left. He had been listening to the conversation with a look of amused contempt on his flabby face. At the head of the table the captain, the engineer, Sinclair, and MacAllister formed one group, who were soon deep in conversation. The tea-buyer took advantage of their preoccupation to address his neighbour across the table:

"So you are one of those missionaries."

"I am."

"Been gettin' a pretty fine collection of souls saved."

"I never saved a soul. Never expect to."

The mate chuckled to himself. But the point was lost on the tea-buyer. He thought that he had scored.

"Glad to see that you have come round to my point of view," he said; "and that there is one missionary honest enough to acknowledge it."

"And what is your point of view?"

"My point of view is that the red-skins and the black-skins and the brown-skins and the yaller-skins ain't got any souls, any more than a dog has."

"I do not know of any reason why the colour of a man's skin should affect his possession of a soul." MacKay spoke very quietly. The tea-buyer began to bluster.

"Reason or no reason, no man is going to make me believe that any of the niggers or Chinees or any of the rest of them have souls. Christian or no Christian, a nigger is a nigger, a Chinee is a Chinee, a Dago is a Dago, and a Sheeny is a Sheeny from first to last. All the missionary talk and missionary money-getting is nothing but damned graft, and the missionaries know it. Boy! One piecee whiskey-soda! Chop-chop!"

"All lite! Have got." And the "boy," a Chinese waiter perhaps sixty or seventy years old, quickly and noiselessly brought the bottles.

"I suppose you have had abundance of opportunity to see and judge for yourself before you came to those conclusions, Mr. Clark," said MacKay.

There was that in his tone which would have made most men careful in their reply. But Clark was too self-confident to be wary, and repeated whiskeys and sodas had made him still less cautious.

"You may bet your bottom dollar I have," he replied. "I have known niggers and Dagos since I was knee-high to a grasshopper; and I have spent every season on the China Coast for the last five or six years. Oh, yes! I know what I'm talking about. I know them from the ground up."

"Doubtless you have visited many of the churches and chapels at the different ports where you have done business, and have for yourself seen the natives at worship."

"Me visit their churches! Not on your life! What do you take me for? I take no stock in any of their joss pidgin. I'd sooner go to a native temple than to a native church. But I've never been in either."

"Then I am afraid that I must assist your memory, Mr. Clark. You were in a native church."

"Me? Never!"

"If I am not mistaken, Mr. Clark, you were a passenger on the American bark Betsy, when she was wrecked on South Point, just outside of Saw Bay, a year ago last November."

"I was. But I don't see what that has to do with the subject we were discussing."

"The Betsy's boats were all smashed as soon as they touched water." MacKay was speaking in the dead level tones of suppressed emotion. But there was something so penetrating in his voice that the conversation at the other end of the table ceased, and all were listening. "The Pe-po-hoan or Malay natives there went out through the surf in their fishing-boats and took every man off safely."

"Yes," replied Clark uneasily, "that's all right enough. But I reckon we could have made the shore ourselves."

"They took you to their village, called Lam-hong-o: they opened their church: the preacher gave up his own house to you: they made beds for you there and fed you."

"Damned poor accommodation, and damned poor grub! Boy! One piecee whiskey! Be quick about it!"

"All lite! No wanchee soda? My can catchee."

"No! Damn the soda!"

"All lite! All lite! Dammee soda!"

"I shall not say anything, Mr. Clark, of the return those white men with souls made to those brown men without souls who saved them. But I shall tell you what would have happened if the missionaries had not gone to Lam-hong-o; if there had not been a chapel there; if those brown-skins had not been Christians. Your ship would have been pillaged. Your heads would have been cut off. Your carcasses would have been fed to the sharks. But they were Christians. So they saved you. They fed you. They clothed you. They sent you home with all your belongings that they were able to save from the sea."

"Right you are, MacKay!" exclaimed Captain Whiteley, bringing his fist down on the table with a thump which threatened to throw on the floor the few dishes which the motion of the ship had not already dashed out of the retaining frames. "Right you are! Nearly thirty years ago I was on the Teucer, Captain Gibson, as senior apprentice with rank of fourth mate. We were bound from Liverpool to Shanghai, but ran on the rocks a little farther down the East Coast than the Betsy did. There were thirty-one of us all told. We got ashore without the loss of a man. But when those devils of natives were done with us, there were only three of us left alive—the carpenter, an A.B., and myself. And we wished that we were dead. We would have been dead, too, before long. But after being worked as slaves for nine months, a Chinaman, who had been with the missionaries on the mainland, bought us from the Malays, and rowed us out to the first foreign ship he saw, the old Spindrift. She took us to Shanghai."

As the captain finished speaking MacKay rose and left the table. As was his wont, he had eaten sparingly and quickly. MacAllister was pressing Captain Whiteley for more details of his captivity among the head-hunters. McLeod was on the point of going out to his watch.

"That was score one on you, Clark," he said to his neighbour. "It doesn't pay to get too fresh even with a parson."

"I don't see that it's any of your pidgin to stick up for those fakirs," retorted the tea-buyer angrily.

"And I don't make it my pidgin," replied McLeod, "but it wasn't up to you to butt in on a man like MacKay the way you did. He gave you what you deserved."

"He needn't have flared up so and brought in all those mock-heroics about what those niggers of his did. I was only jollying him. He made things a great deal worse than they were."

"He didn't make things half as bad as they were, Clark. What about the way the native preacher's daughter was used by the men to whom the preacher gave up his house and his church? Those brown-skins may have no souls. But MacKay believes they have. To my thinking they have a good deal more soul than the white-skins who did what was done there. You fellows went the limit. I wonder that MacKay let you off so easy."

"Oh!—Say!—Damn it, McLeod, that's going too far.—I'll not stand for that.—Say!—Here!—McLeod!—Wait and we'll break a bottle of champagne.—Here!—Boy! One piecee champagne!"

"No, thank you, Clark! It's my watch."

At the door the chief officer paused and called back:

"Say, Doc, when you are done feeding that big body of yours, come up on the bridge."

"All right, Mac. I'll be with you."

III

THE TYPHOON

When Dr. Sinclair joined his friend on the bridge, a very marked change had come over the weather. It was intensely hot and sultry even where the circulation of air was freest. The wind was no longer blowing steadily from the south-west. It came in short puffs, dying away entirely between them, and veering around quarter of a circle. The short, broken waves of earlier in the evening were giving place to a long swell, coming up from the south. The movement of the ship was much easier. One or two passengers who had been unable to appear at dinner had recovered sufficiently to come on deck and escape the unbearable sultriness and stuffiness of the cabins.

"It's coming all right, doctor. Going to catch us sure. I don't care so much if it will only wait till daylight. I have no ambition to be floundering around this channel in a typhoon in the dark."

"How's the glass?"

"Away down, and still going. Haven't seen it so low since the big typhoon that cleaned up Hong-Kong Harbour a couple of years ago."

"What prospect is there that the big blow will hold off till morning?"

"Oh, pretty fair! The rain hasn't started yet, and on this coast we generally get splashes of rain for quite a few hours before the real thing begins. The sea is rising, but not very fast yet. I don't think we'll see very bad weather till to-morrow."

Just then a merry ripple of woman's laughter sounded from away aft.

"Listen to that, Sinclair," said the mate. "That 'sweet Highland girl' of yours has evidently recovered sufficiently to come on deck. She's back there talking to the captain. I hope he may be as gallant as he sometimes is with our rare lady passengers, and may bring her up here to view the scenery. I should just like to see how you and she would act at your first meeting after the little tiff you had to-day. I'm interested in this case, doctor."

"What the deuce is the matter with you anyway, McLeod? You are talking a lot of rot to me about a young woman I have never seen before. Surely our experiences so far have been unpropitious enough. If it were not that I know about a little girl away back on your own Island, I should say that those moonlight promenades between Hong-Kong and Swatow had turned your head."

"Never mind, Doc. You know that a bad beginning makes a good ending. We people of Highland blood have a sort of second sight. We can see a bit into the future. I give you fair warning——"

There was another ripple of laughter, this time from forward, almost under the bridge. Then a woman's voice said:

"Oh, Captain Whiteley, I behaved myself most shockingly to-day."

"Surely not, Miss MacAllister. I couldn't conceive of your doing anything which wasn't charming."

"You told me that you were a Yorkshireman, Captain Whiteley. After such a speech as that I believe that you must have been born near Blarney Castle. But I really did behave shamefully."

"How?"

"I said just awful things to your doctor."

"And what ever did Dr. Sinclair do to deserve those 'awful things'?"

"It was all your fault, Captain Whiteley. When you introduced him, you did not tell me that he was a doctor. I was sea-sick, and—and in just dreadful humour. He offered assistance. I did not know that he was a medical doctor, sauced him, and sent him about his business. And now what shall I do to make amends? It was all your fault——"

Anything more was lost to the ears of the two young men on the bridge, as she and the captain strolled slowly aft. But the rippling laughter reached their ears from time to time.

"Not very penitent, that!" laughed McLeod.

"Did you catch on to the reason she gave for saucing me, because she didn't know that I was a medical doctor? It was just when she found out that I was a doctor that she gave me the worst. Doesn't that beat the Dutch?"

"'O woman! in our hours of ease,Uncertain, coy, and hard to please,'"

quoted McLeod.

In the light of the binnacle lamp the two friends looked into each other's eyes and laughed heartily. There was no cynicism, no cheap scoff at a woman's variableness. Instead there was that manly healthy-mindedness which can afford to laugh at her inexplicable ways, and honour and admire her still.

"By the way, McLeod, Dr. MacKay put it all over Clark this evening, didn't he? I couldn't hear it all. Caught just the last few sentences. But I thought, from what I heard, that he was giving that old Mormon some knockout blows."

"You're right he was. But not half as much as he deserved. There are some white men who come out here who wouldn't be decent company for pigs. Clark is one of them. I'm no paragon of virtue, and I don't set up to preach to others. But there are a lot of us on the China Coast who try to keep decent enough not to be ashamed to go home once in a while and look our mothers and sisters in the face. There are a number of others who are simply rotten. They give us all a bad name. Mormon! Yes, worse than that! He could give points to old Abdul Hamid of Turkey."

A dash of warm rain driving before a sharp squall of wind struck them. The Hailoong was rising and falling with the mighty heave of the great swells which were following each other in regular succession from the south, each apparently bigger than the last. Captain Whiteley climbed the ladder to the bridge.

"Looks as if we were in for a bad night, Mr. McLeod."

"Yes, sir; and a worse day to follow."

"From the way the sea is rising, I'm afraid we cannot make Tamsui before it breaks."

"I am sure we cannot. I'll be satisfied if it only waits till daylight. We may have our hands full even with the light."

"I see that you have been making things snug. That's right. I'll have a look at everything before eight bells."

The captain went down to see that every preparation was made. McLeod spoke to his companion.

"You had better turn in, Sinclair," he said. "Get a bit of rest. You may be needed to-morrow. Good-night."

"Good-night, Mac."

* * * * *

How long he was in his berth, how much of that time he slept, how much was spent in more or less conscious efforts to keep from being thrown about his cabin, Sinclair did not know. Accustomed though he was to the sea and to storms, there came a time when he could remain in his berth no longer. The angle at which the ship lay over told him that she was still holding in her course of the night before. His cabin was still on the lee side. He opened his door and stepped out, grasping the hand-rail with all his might to keep from being hurled off his feet.

Such a sight met his eyes as is rarely seen even by the sailor who spends his life at sea. The Hailoong was heeled over so far that it seemed hardly possible that she could right herself. It appeared to be the force of the wind rather than of the waves which had thrown her on her beam ends, for she did not recover herself as she ought to have done between the assaults of the billows. Held in that position by sheer wind pressure, she was deluged with water, rain, spray, torn crests of waves—the air was full of them, while ever and anon some mountainous roller, higher than its fellows, swept across her decks in a smother of green water and snowy foam.

So dark was it that at first Sinclair could scarcely tell whether it was night or day. Presently he made out some figures clinging desperately to anything which would afford a hold of safety. He made his way slowly towards them. They were McLeod and a couple of the crew, looking to the lashings of the boats.

"Man, but it's a wild morning whatever!" roared the mate in his ear, lapsing into the idiom of his native province when his feelings were greatly stirred.

"How is she standing it?"

"Fine, so far! The starboard boats are smashed. No other damage done that I know of. But it's hard to tell what may be happening to starboard. Nothing to be seen but water!"

"The engines are working all right," said the doctor, as he noted the steady throb and quiver running like an undertone through the succession of terrific shocks the ship was receiving from the waves.

"Ay, and if they don't work all right, it'll not be Watson's fault. Yon's a grand man whatever."

The mate was off, traversing the tilted deck with marvellous agility and sureness of foot. The doctor went below to see if he could be of any service to the passengers. An hour or more passed, and he was again on deck, working his way forward to get as good a view as possible.

There in the shelter of the forward cabin stood Dr. MacKay. He was bareheaded; his long, black beard was blowing in the wind; his white suit was drenched as if he had been overboard; his keen eyes were striving to pierce the murk of cloud and rain and spray which turned the day almost into night. He seemed to be expecting to get a glimpse of the land.

He was not clinging to the hand-rail, but had his hands clasped behind his back. In spite of the distressing angle at which the ship's deck was tilted, in spite of her pitching and plunging, he seemed able to accommodate himself to her every movement. A man of big stature and splendid physical development himself, Sinclair could not help pausing for some minutes to admire the poise and self-control of that comparatively small, spare, but erect and athletic figure. Then he stepped a little nearer and shouted:

"Do you often have storms like this in Formosa?"

"I have seen as bad; perhaps worse: but not often."

"Do you think that we're near Tamsui?"

"We must be."

"Can we make the harbour?"

"Not this time. We'll be late for the tide."

"A bad wind for putting about and getting out to sea again!"

"'Who hath measured the waters in the hollow of His hand?'"

At that instant a tremendous billow tumbled on board with such a weight of water that for some moments it seemed as if the Hailoong could not rise from beneath it. It caught two Chinese deck-hands, tore them from the bridge supports to which they were clinging, and swept them helplessly from starboard to port. Like a flash MacKay's left hand shot out, grasped a thin brown wrist, and swung one of the natives into the shelter of the cabin. But the other was dashed with terrific force against the deck-rail, where he lay motionless.

Sinclair sprang forward to help him. A second wave hurled him against the rail. He did not fall, but performed some weird gymnastics in the effort to keep his feet. And through the shrieking of the wind and the roar of the waves he heard a clear, joyous woman's laugh, the same as he had heard the night before. There in the shelter of the cabin, on almost the very spot where he had stood a moment before, was Miss MacAllister, looking like the very spirit of the storm.

That was too much. Even Sinclair's usually unruffled temper began to give way. He caught up the helpless Chinese as if he had been a child, and with one quick spring was back to shelter.

"You seem to find it very amusing to see men hurt, Miss MacAllister," he said almost fiercely.

"I did not know that you were hurt, Dr. Sinclair, or I should not have laughed. I am so sorry."

"I'm not hurt," said the young man even more ferociously than before; "but this man is injured, seriously injured, I'm afraid. He's still unconscious."

"Oh, but I was not laughing at him. I was laughing at you. You would have laughed yourself if you could have seen the figure you cut going across the deck. Really, Dr. Sinclair, you would. I simply could not help it."

She looked up in his face with such a childlike innocence of expression, such confidence in the validity of the excuse, that even Dr. MacKay's somewhat stern face relaxed, and he turned away to hide a smile. As for Dr. Sinclair, he was helpless. He could not remain angry under the circumstances. His good-humoured laugh broke out as he replied:

"We must accept your confession, believe in your penitence, and grant you absolution."

He and MacKay went below with the injured Chinese, but in a few minutes reappeared on deck.

"I have not seen your father to-day, Miss MacAllister," said Dr. MacKay.

"He is in his stateroom with mother. She is very ill and he will not leave her."

"I must congratulate you on being so good a sailor. You do not show a symptom of sea-sickness. That is quite remarkable in such a storm as this."

She shot a quick glance at Sinclair. He did not seem to be paying attention to what they were saying. But a quizzical smile playing about his eyes and mouth betrayed his interest in the conversation and his remembrance of what had taken place the evening before.

"Indeed, Dr. MacKay, I am not a good sailor at all. I have been sea-sick when there was only a little chop on the water. I was sea-sick yesterday. I should have been sick to-day, only this storm is so interesting that I have not had time to think about myself. When the officers and crew are being tossed about the deck by the waves, like dead leaves on a burn in autumn, it is really too interesting and amusing to be missed."

The rare smile lighted up the missionary's face as he glanced at Sinclair. The latter accepted the challenge, and a quick answer was on his tongue, when McLeod hurried past. He paused long enough to say to Sinclair:

"We're opposite the harbour, doctor, but we can't make it." Then he ran up on the bridge to join Captain Whiteley, who had not left it since midnight.

The words were intended for Sinclair alone. But a momentary lull in the storm made them louder than McLeod anticipated. Sinclair's two companions heard them. Yet neither showed any trace of concern—neither the mature man who had faced death scores of times on sea and on land, nor the young woman who had never knowingly been in danger before.

The same brief lull in the force of the wind brought an equally momentary gleam of light through the darkness, which had up till then made noonday as gloomy as a late twilight. That gleam lighted for a few short seconds the landscape, and showed the storm-tossed company where they were. There directly ahead was the harbour of Tamsui, with the green and purple hills beyond. There on the nearest hill-top was the Red Fort which for two and a half centuries had braved such storms as this. Just beyond it were the low white bungalows of the mission, nearly hidden in the trees, where anxious eyes were watching for one who was on that battling ship. There, too, were the black balls hanging on the yard-arm at the signal station, saying that the tide was falling and the bar impassable. And the two white beacons for a single instant in line, and then widening apart, told the seamen that not only the tempest but the ebb tide, sweeping past the mouth of the harbour, was bearing them full upon the long curving beach of sand and shells which lay just to the north, where the surf was beating so furiously.

It takes time to tell. But in reality the respite lasted only a few seconds. Then the typhoon burst upon them again, with apparently redoubled violence. The darkness and the tumult of wind and waves were appalling.

"I wonder that you are not afraid," said Sinclair to Miss MacAllister, losing sight of their passages at arms in the seriousness of the situation.

"Should I be afraid?" was her reply.

"Most people would be."

"Are you afraid?"

"No: I do not think I am."

"Well, if you and the other officers who know whatever danger there may be are not afraid, I do not see why I should. They know the situation. I do not. When they tell me that there is serious danger, it will be time enough for me to be frightened."

Then for the first time Sinclair turned upon her a look of genuine admiration. Up to that moment she had been to him a mischievous, teasing, whimsical girl, with a quick wit and a ready tongue, who had been amusing herself at his expense. Now he saw another side to her character. There was a strong, brave nature under the light, changeful surface humours he had seen before.

If she were not afraid, there was at least one passenger who was. During the brief lull in the storm Clark, the tea-buyer, had come on deck. He had hardly reached it when the second fury of the typhoon burst upon them. He was now clinging to the hand-rail, with a face so flabby and ghastly that it was terrible to look upon. He was not sea-sick. He was too experienced a sailor for that. But he was afraid, horribly afraid. As the murk and gloom closed down again, and a gigantic wall of water broke over the ship, making her shudder and struggle like a living thing in death agony, Clark's voice was heard rising in a scream above the roar of the elements:

"MacKay, for God's sake, why don't you pray?"

MacKay looked at the man clinging there in abject terror. For a moment the keen, stern face softened as if in pity. Then it seemed as if the memory of something—was it of that wreck on the East Coast, and the evil deeds done in the chapel and the preacher's house there?—flashed through his mind. His face hardened again, and in a voice like ice he replied:

"Men who honour God when the days are fine do not have to howl to Him for help in the time of storm."

What more the terror-stricken boaster of the evening before may have said was lost on his companions, for something was happening which engrossed all their attention. Down in the engine-room bells jangled sharply. The screw began to thresh the water at a tremendous rate. The Hailoong heeled still farther to port, began to forge ahead, bumped something, was caught by a mighty wave squarely on the stern, righted herself, and plunged forward. Then Sinclair realized what was happening.

"Everybody below!" he shouted. "Quick! The next will catch us on this side. Dr. MacKay, help Miss MacAllister."

Seizing the helpless Clark, he flung him by main strength into safety. They were scarcely under cover when a big roller tumbled on board on the port side. The Hailoong had turned almost completely around, and was fighting her way out to sea.

All afternoon and far into the night the brave little vessel battled with the waves to get back to the coast of the mainland. At last her anxious officers were rewarded by a distant, hazy gleam of light through the dense, water-laden atmosphere. Fifteen seconds passed, almost minutes in length. Again the white beam shot athwart the darkness. Then regularly and growing ever nearer, at intervals of fifteen seconds, the great white light flashed, showing the way to safety. It was Turnabout lighthouse, behind which lay Haitan Straits, winding among the islands, and between them and the mainland shore.

Into one of their many natural harbours the Hailoong cautiously felt her way, and cast anchor in a quiet basin among the hills. There nothing but the torrents of rain falling and the roar of the surf beyond the island barrier remained to tell of the dangers they had passed through. Then Captain Whiteley left the bridge for the first time in more than twenty-four hours. Neither he nor his chief officer had found a chance to sleep for forty-eight hours.

For years afterwards only three persons knew exactly what happened on the bridge that day. Then when Captain Whiteley was commanding a Castle boat running to the Cape, and McLeod had a big trans-Pacific liner, the quarter-master, who with a Chinese sea-cunny had been at the Hailoong's wheel, felt absolved from the promise he had made to McLeod to keep the secret, and told what he knew.

When the momentary lifting of the clouds showed the captain that the wind combined with the ebb of the tide had carried them past the line of entrance to the harbour, towards the shoaling beach on which the surf was beating, he shouted to his mate:

"My God, McLeod, we're lost!"

"Not so bad as that yet, sir!" was the reply.

"There isn't room to turn and clear that shoal water. To starboard it's stern on: to port it's broadside on."

"We haven't tried, sir!"

"Then, for God's sake, McLeod, try!"

The words had hardly left the captain's lips when the engineer received the signal for full steam ahead, and the mate, springing into the wheel-house, flung himself on the wheel, and with the combined strength of three men forced it over. The Hailoong responded gallantly. Her head swung directly towards the dreaded shoal, passed it, and pointed out to sea. So close was she that when the wind caught her stern it dropped just for an instant between two rollers on the hard, smooth sand. But the next one lifted her, gave her churning screw a chance, and the ebb tide, which a moment before had been threatening to send her broadside to destruction, now helped to bear her past the long receding curve of the sand bank, out into the open sea.

"That was the tightest corner I ever was in," Whiteley used to say afterwards; "and it was McLeod who took us out."

But McLeod, in a moment of confidence, said to Sinclair:

"Man, but that engineer, Watson, is the jewel whatever! He let his second handle the levers, while himself held pistols to the heads of the Chinese stokers, and told them to shovel or die in their tracks. That's what saved us. He's a jewel. I never saw his likes whatever."

IV

PARRIED

It was a bright, calm summer day, perfect in its tropical splendour, when the Hailoong arrived off the port of Tamsui. On the blue, smiling sea and rich green shore not a trace remained of the furious storm of two days before. Where, save for one brief gleam, all had been hidden from sight by the blackness of the tempest and the deluge of rain and spray, there now lay before the ship's company as fair a landscape as the eye could wish to look upon.

Immediately in front of them was the broad, brimming river, its sand-spits and oyster-beds hidden beneath the waters of the full tide. On the right or southern shore a mountain rose from its margin in an isolated peak to the height of seventeen hundred feet, clothed with dense verdure to the very summit. To the left, on a hill and plateau two hundred feet high, were the red brick buildings of the old Dutch fort, the residence of the British consul, and the mission schools, and the white bungalows of the missionaries and customs officers. At the foot of this hill and along the river bank, the mean buildings of the Chinese town of Tamsui straggled off until lost to sight around the curve. Its limits were marked by the little forest of masts of the junks which lay along in front of the town. In the centre of the river, directly opposite the mission houses, a trim gunboat rested at anchor. Over all rose the Taitoon Mountains in successive ranges of green and purple and blue, the highest and farthest summits blending with the unclouded sky.

Exclamations of delight burst from those of the passengers who had never looked upon the scene before.

"Father, isn't this just glorious?"

"It certainly is. I have often heard of the beauty of Formosa, but this first view quite exceeds my expectations."

"It was worth while experiencing that typhoon and being delayed for two days. It heightens the enjoyment of a scene like this. We should not have appreciated it so much if we had been favoured with a peaceful voyage. Do you not think so, Dr. MacKay?"

"Perhaps you are right, Miss MacAllister. But Formosa is always beautiful to me. It never loses its charm. I have gone up and down it for more than a dozen years. I never grow weary of it. It never palls upon me. It is still to me as the first day I saw it 'Ilha Formosa,' the Beautiful Isle. It always will be Beautiful Formosa."

There was an accent in his reply which spoke of more than love for the scenery. Miss MacAllister was not slow to detect it. She heard in it the passionate devotion of a heroic soul to the cause to which he had given his life. It struck a responsive chord somewhere in her own being. It was with a softened voice, a voice expressive of sympathy and admiration, that she said:

"You love the island and its people, Dr. MacKay?"

"I do."

And Sinclair, who chanced to be standing near, as once before during the storm, saw the veil of her surface waywardness lifted and caught a glimpse of a character beneath which was capable of serious purpose.

"Mr. McLeod, that sampan over there with the flag is hailing us."

It was the captain's voice which broke in on the conversation of the group on deck.

"Yes, sir," replied the chief. "It came out from the pilot village, and has been waiting for us."

"I wonder what's up?"

"I don't know, sir. Hold on, they are signalling from the Customs."

In an instant the chief officer had a glass focussed on the flagpole at the customs offices. The other officers and the passengers stood silent while the little fluttering oblongs and triangles of red, white, yellow, and blue talked.

"What do they say, chief?"

"Wait for a pilot. Danger."

"A pilot! The devil! What do they take us for? Some tramp which has never been here before? Perhaps the typhoon shifted the bar."

While he spoke, McLeod had swung his glass upon the approaching Chinese boat. Two fishermen, standing up and pushing forward on their long oars, were driving it rapidly through the water. Their bodies, naked to the waist, and their legs, bare save for the shortest of cotton trousers, were covered with perspiration and shone in the sun like burnished copper. In the stern sat a Chinese in a dress which was an indescribable cross between Chinese official robes and a Western uniform.

"That's a Chinese military or naval officer of some kind, sir," said the mate. "They must be in a mix-up with somebody. Perhaps the French have taken it into their heads to annex Formosa."

The sampan shot alongside, and with unexpected agility the Chinese officer clambered up the sea-ladder.

"The captain will please to excuse me," he said in slow, precise English, "for offering to pilot his ship into the harbour. The captain's skill as a pilot is well known to me. The government of China regrets to find itself in a state of war with the government of France. Therefore, His Excellency, the Provincial Governor of Formosa, has laid down mines for the defence of the port of Tamsui. As I have knowledge of the position of the mines, he has commanded me to pilot the captain's ship past the mines into the harbour."

He concluded his little speech with a profound bow. The captain's reply was brief:

"The ship is yours, sir."

Another profound bow, and the Chinese officer was in charge.

Captain Whiteley turned to Mr. MacAllister.

"I am sorry, sir," he said, "that the French have taken the notion to transfer their scrimmage with the Chinese to Formosa just at this moment. It will interfere with your plans."

"It probably will interfere somewhat with our movements. But, on the other hand, it may be of advantage to us. We are out to learn, and are not hampered by lack of time. I am deeply interested in your pilot. He seems perfectly at home, and to know his business thoroughly."

"Not the slightest doubt of that! This is not the first time he has navigated a ship. Very likely he has spent years of apprenticeship on board a British or American man-of-war."

"Is China getting her young man trained like that?"

"They are getting themselves trained. The government isn't awake yet. But many of the young men are. The old China is passing. This is one of the pioneers of the new China which is coming. It will take time. But when it does come, mark my words, the Western nations will have to sit up and take notice."

Meanwhile the Hailoong, under the command of her Oriental pilot, crossed the bar and zigzagged her way slowly up the river, following invisible channels through the field of hidden mines until she reached her berth at the customs jetty.

Leaning on the rail, Sinclair watched with keenest interest the little crowd of foreigners and natives gathered on the shore and jetty, waiting for the passengers to disembark. He had met a number of them on a former trip to this port, and occasionally waved his hand or gave a greeting to some one he recognized.

There was a sprinkling of officers of the Imperial Maritime Customs, sunburned young Britons for the most part, who had taken service under the brilliant Irishman whose genius had saved the Chinese Government from bankruptcy. There were the representatives of the various foreign business firms, all British, glad to leave their hongs for an hour, to experience the little excitement caused by the coming of the weekly steamer, and to welcome those whom they had almost given up for lost. The foreign community doctor had found time from his not very pressing duties to come down to the landing and call a "Wie geht es Ihnen?" to his confrère on board the Hailoong.

Contrasting with the close-fitting snow-white garments of the foreigners were the long, blue, or mauve silk gowns with, in some cases, sleeveless yellow jackets over them, of the Chinese Christian preachers and students who were there to do honour to Dr. MacKay. Darting back and forth, chattering, screaming, quarrelling in high-pitched nasal tones, were bronzed, sweating, almost naked coolies, each trying to get ahead of the other and earn the most cash.

It was a scene of which Sinclair never tired. Fascinated by this strange mingling of the East and the West he leaned over the rail, watching every movement. A quick step approached him:

"Dr. Sinclair, as soon as your duties here are done, you will come to my house and be my guest. The college coolies will bring up your baggage. If I am not there, Mrs. MacKay will receive you and look after your wants."

"Thank you, Dr. MacKay. I shall be very glad to accept your hospitality for a time. I shall probably be with you to-morrow."

MacKay was gone as quickly as he had come. A minute or two later his native converts were receiving him with the oft-repeated salutation: "Peng-an, Kai Bok-su! Kai Bok-su, peng-an!" (Peace, Pastor MacKay! Pastor MacKay, peace!).

One of the oldest preachers walked off with him up the narrow, climbing path. The rest tailed out in single file behind.

There was another quicker and lighter step, accompanied by the rustle of a woman's garments. Sinclair turned to find himself face to face with Miss MacAllister. Her eyes were sparkling with mischief, her hand was extended in farewell:

"Good-bye, Dr. Sinclair. I have enjoyed this voyage so much. I hope that we shall meet again. But, if we should not, I shall never forget your rescue of that Chinese, the heroism and the grace you displayed. Really, I never shall."

It was premeditated, and she intended to escape the moment the shaft was shot. But Sinclair was not so nonplussed as he had been at their first encounter. He held her hand firmly so that she could not get away, long enough to reply:

"Good-bye, Miss MacAllister. I am delighted to know that I have given you pleasure. I should be happy to make a similar exhibition of myself any day, if it would only contribute to your enjoyment."

He released her hand and she escaped into the saloon. The colour which overspread her face was not all the flush of triumph. This time she had met the unexpected.

"Well parried, Doc," said a voice beside him. "That fair tyrant was beginning to think that you were an easy mark. But you gave her as much as you got this time.... Here's a chit for you.... From the consulate."

"Where's the boy?" said Sinclair, taking the letter McLeod held out to him. "I had better sign his chit-book."

"You don't need to. I signed for you. There's the boy going back," replied the mate, pointing to a Chinese in the dark blue and red uniform of the British consul's service, climbing the steep path up to where the old Dutch fort and the consul's house crowned the lofty hill above them. "Don't think that you are the only one to get a billet-doux like that. The captain and I are among the favoured. It's a bid to dinner at the consulate to-morrow evening."

Sinclair opened and glanced at the note. It was a brief and formal invitation:

"Mr. and Mrs. Beauchamp request the pleasure of the company of Dr. Donald Sinclair at dinner at 7:30 on Tuesday the 5th instant.

H. B. M. Consulate,

Tamsui,

August 4th, 1884."

"I guess I'll be able to go. Though I promised to put myself in MacKay's hands to-morrow, and he may have something else on for me."

"No danger! MacKay knows everything that's going on as well as the next one. He will not ask you to do anything which will conflict with a dinner at the consulate. If he's at home, he'll be there himself. You just lay out to be present. Mrs. Beauchamp is famous for the chow she provides. Where she gets it out here off the earth, I don't know. And for entertaining guests, she and Beauchamp haven't their equals on the Coast."

"You're a great pleader, Mac. I'll give you my word. I'll go."

"And the Highland girl will be there."

"Look here, McLeod, you're gone batty on that subject. I know an address in Prince Edward Island. If you continue to talk as foolishly as you have been doing the last few days, I'll write and peach on you."

"Oh, no, you won't! But just to change the subject, look at old De Vaux meeting them. He's so excited that I shouldn't wonder to see him take an apoplectic fit."

Mr. MacAllister, his wife, and daughter had just left the boat. A large, fleshy man, with a clean-shaven, florid face, bulging blue eyes, and all his features except the double chin bunched unnecessarily close together, was hurrying forward to meet them in a state of perspiring excitement and nervousness. He was carrying his white sun-helmet in one hand, mopping his brows with a huge handkerchief held in the other, and all the while the mid-summer tropical sun was beaming down on his shining face, and on his head with its quite inadequate covering of hair.

"Mr. MacAllister! ... You cannot know what pleasure it gives me to welcome you to Formosa.... 'Pon my soul, you cannot! ... I have been twenty years in Formosa, and this is the greatest pleasure I have experienced.... 'Pon my honour, it is!"

"Glad to see you again, Mr. De Vaux. If I remember right, the last time we saw each other was in our office at Amoy, five years ago last May."

"That is so, Mr. MacAllister.... Lord, what a memory you have! ... I don't know another man on the China Coast who would have remembered a date like that.... 'Pon my soul, I do not!"

"Mr. De Vaux, I wish you to meet my wife and daughter. My dear, allow me to present Mr. De Vaux. My wife, Mr. De Vaux. My daughter, Mr. De Vaux."

The stout man bent double in profound bows, dropping his hat to the very ground, gurgling something almost inarticulate with excitement:

"Mrs. MacAllister! ... I am so pleased! ... Bless my soul! Miss MacAllister.... This is the happiest moment of my life.... 'Pon my honour, it is!"

Above them on the deck Sinclair was saying to McLeod:

"Who is this De Vaux, anyway? Of course, I know that he is chief agent in Formosa of MacAllister, Munro Co. But who is he and what are his antecedents?"

"That is just the question," replied McLeod. "We know, and we don't know. We know that the Honourable Lionel Percival Dudley de Vaux is the oldest known son of the late Lord Eversleigh, the oldest brother or half-brother of the present lord. But why he is out here sweltering and swearing in this steambath of a climate while his younger brother enjoys the cool shade of his ancestral parks and halls, and holds down a seat in the Lords, no one seems to know. Some say that he is the son of the late lord by a Scotch marriage in his wild-oat stage; some that he is a son born to the late lord by the countess dowager before wedlock. At any rate, he was shipped to the Far East as a boy, and here he has been these more than twenty years, pensioned, they say, to keep out of England."

"He seems to be very excitable," said Sinclair, as he looked down at the stout, perspiring individual, who was still holding his hat in his hand, still bowing, still gurgling in a high-toned voice, while his face and head grew redder and shinier every moment.

"Yes, he is now. When he came out first, they say that he was a regular Lord Chesterfield in his manners. But he was here alone for years. No comforts but drink and a yellow woman. He took to both. These with the isolation and the climate have made him what he is. When he meets a white woman he loses his head completely. Any little irritation in business sends him right up in the air. Then he swears. We call him old De Vaux. In fact he has hardly reached middle age. The life here is killing him. If he doesn't die of apoplexy one of those days, he'll commit suicide. And he's not a bad old soul. Just the victim of his parent's wrong-doing. Poor old De Vaux!"

Just then they heard Miss MacAllister saying in a tone of utmost concern:

"Mr. De Vaux, will you not put on your hat? I am so afraid that your head will get sunburned."

"A sunstroke you mean, my dear," said her father, "a sunstroke."

"No, father, I mean sunburned. Really, Mr. De Vaux's head is becoming quite crimson."

"Lord! ... Miss MacAllister! ... How good of you to notice that! ... Bless my soul! ... I never thought of it.... 'Pon my honour, I didn't! ... A man should put on his hat in a sun like this.... 'Pon my soul, he should!..."

He was still executing a sort of war-dance around the ladies and still holding his hat in his hand. Mr. MacAllister took him gently by the arm.

"My dear De Vaux," he said, "it has been exceedingly kind of you to come down to meet us as you have done, and to provide those sedan chairs, for I can see that it is you who have engaged them. With your permission, we'll go to our quarters now. The captain promised to see that our baggage was sent over at once. After tiffin, I am sure that you will be so good as to accompany me to call on the consul."

As the four chairs were borne off along the narrow road by the shore, McLeod said to Sinclair:

"MacAllister's a trump. He saved the situation. Old De Vaux was just ready to go up like a balloon, and—swear."

And Sinclair thought to himself as he turned away:

"Miss MacAllister has found another victim."

V

INTRODUCTIONS

A few minutes before the time appointed for dinner, Sinclair strolled over to the consulate. A couple of the I.M.C. officers joined him on the way. Out on the broad verandah the consul and his wife were receiving their guests, taking every advantage possible of the slight coolness of the evening air. None had yet gone inside. Some lounged on the verandah. Most were strolling about the grounds, on the gravelled walks or the green of the tennis lawn between the house and the old Dutch fort.

Many coloured paper lanterns hung from the cocoanut and areca palms, were nestled in the clumps of oleanders, or were strung on wires around the verandah. On the side of the house shaded from the sunset glow, native servants were already lighting them.

It was a scene of rare beauty. The broad river gleaming between its lofty banks: the green mountain towering up on the opposite shore: the glassy ocean stretching away to where the sun had sunk to rest in its waters: the old fort lifting its dark, massive walls and battlements, undecayed by centuries of tropical storm and tropical sun, against the pale yellow and rose and purple of the sunset sky: the strange, rich vegetation of a tropic clime, amidst which moved men and women in conventional evening dress, as they would have done in the drawing-rooms of England.

Save for the shrilling of the cicadas and the quiet voices of the hosts and their guests, the air was as still as if it had never known disturbance. Yet all that day, from eight A.M. till nearly sundown, it had quivered with the roar of heavy ordnance and the rattle of machine guns. Less than twenty miles away, across those hills to the east, the French fleet had poured a tempest of shot and shell from its long naval guns and mitrailleuses into the Chinese forts at Keelung, and the Chinese had replied from their Krupps and Armstrongs till their defences tumbled about their ears. Now the game of war was over for the day, and all seemed as peaceful as if it had never been played. But the conversation of the guests continually reverted to the tempest which had so suddenly broken upon the island.

Just at the hour set for dinner the little gunboat, the Locust, which had been away since early dawn, was seen steaming up the harbour. As she passed the consulate, a boat dropped from her and pulled swiftly in towards the jetty. At the sight of it the host and hostess led the way into the brightly-lighted drawing-room.

"Commander Gardenier has made jolly good time," said the consul. "We can well afford to wait a few minutes for him. He'll be here directly. In the meantime we can get acquainted."

While the host was busy with introductions, Sinclair had time to consider the company. He had met almost all before. But he had not by any means satisfied his keen interest in their personal characteristics. One by one he studied the men and women before him, taking in with the celerity of one who has long practised it as an art the physical type of each, and estimating the mental peculiarities which lay behind the outward forms.

The first was the consul. Of barely middle height, but perfectly proportioned, every movement betrayed muscles trained and developed by consistent physical exercise. The keen, bright blue eyes, looking out of a sunburned face, the small, closely-clipped moustache, the nervous, vigorous movements, hardly needed the confirmation of his short, quick sentences and decisive accents to tell the story of his character. The interests of his country would not suffer at his hands for lack of courage or decision.

Mrs. Beauchamp was a small woman, somewhat delicate in appearance. Her slight figure was well set off by the rich simplicity of her evening gown. The quiet ease of her manners spoke of a lifetime spent in the atmosphere of polite society.

In sharp contrast was Mrs. MacAllister—large, stout, middle-aged, with raven black hair, and the bright colour characteristic of her Highland people still warm in her cheeks. Considering the occasion and the tropic heat, she was over-dressed. More noticeable still was the fact that she was not at home in her present surroundings. With her husband she had risen from a humble station in life to wealth, and the entrée into social circles which wealth gives. The wife of the great London merchant and financier must not be overlooked. Oh, no! Indeed, she had no desire to be overlooked. She had brought from an almost menial position an exaggerated reverence for the gentry, and the ambition to associate with them. Yet she was never at ease in their company. Her husband showed the poise of one who could adapt himself to any position in life, and manifested no embarrassment or awkwardness in any company. But Mrs. MacAllister was never free from constraint at social functions, and her attempts to appear at home sometimes resulted in disaster.

There was another married woman present—Mrs. Thomson, the wife of Dr. MacKay's colleague. Youthful in face and figure, she was dressed plainly, almost to the verge of severity. But her quick wit and vivacious manner gathered a little group of the guests about her, and more than atoned for the commonplace dulness of her husband.

Standing among some tropic plants just outside a French window, Sinclair, unobserved himself, was able to study each one in succession. But ever and anon his eyes turned to where nearly half the men present had gathered around the only other woman who was there to grace the occasion. Miss MacAllister was facing him, and he could note every play of expression on her countenance. There was a rapid exchange of conversation, and she had an answer for every one. The rippling laughter he had heard on the deck of the Hailoong now sounded over the murmur of voices in the drawing-room.

"What a queenly stature and bearing!" Sinclair thought to himself.

It was true. Miss MacAllister was taller than all but one of the little circle of men gathered about her. She held her small head, with its wavy crown of rich brown hair, as if she were proud of her commanding height. Her eyes, so dark a blue that in the light of the candles they seemed black, looked right over the heads of the men of average stature.

Yet, if her height was masculine, there was nothing masculine about her figure. Though well proportioned and vigorous, it gave the general impression of slightness. Neither was there a trace of masculinity about the face. It was thoroughly feminine, with its somewhat low forehead, its small, straight nose, the rich, Highland colour in the softly-rounded cheeks, the small chin, and the lips parted in merry laughter—a thoroughly girlish face.

Keeping himself in the shadow, and looking at her in the bright light of the drawing-room, Sinclair thought that rarely, if ever, had he seen a more strikingly beautiful woman. He wondered that he had not noticed it before. Then he laughed to himself as he remembered that, during their short acquaintance, he had so often suffered from her raillery that he had been in little humour for appreciation or admiration.

"A pretty picture, that!" said McLeod's voice at his shoulder. "I am glad to see you enjoying it, doctor."

"Until I get better acquainted I prefer looking on to taking part in the conversation. It's an interesting study."

"Isn't she a beauty? That evening rig sets her off to perfection." McLeod generally used nautical terms to describe dress, on which he was not an expert.

"I see that you are still on the same tack," replied Sinclair, with a laugh. "But really I agree with you that the 'rig' does suit her, and that she is a beauty. Who is that tall, dark fellow who is trying to monopolize the conversation with her?"

"English remittance man. A younger son, no better than he ought to be. Sent out here to be rid of him. In a moment of weakness the I.G.[#] gave him a place on the customs.... But here comes Beauchamp."

[#] Sir Robert Hart, Inspector-General of Chinese customs, was familiarly known as the I.G.

"Is this where you are, Sinclair? I have been looking around for you. Have you met every one yet?"

"I believe so, Mr. Beauchamp, except the tall gentleman talking to Miss MacAllister."

"Come along then and I'll introduce you before I have to receive Gardenier.... Miss MacAllister, I am sure you will pardon me for interrupting your conversation. I should like to make these gentlemen acquainted.... Dr. Sinclair, the Honourable Reginald Carteret of the Imperial Maritime Customs staff.... Will you excuse me now? I see Commander Gardenier at the door."

Sinclair saluted Carteret with the frank, easy courtesy which suited so well his big, powerful frame and pleasant countenance. The acknowledgment was a slight, stiff bow and a brief:

"Glad to make your acquaintance, I'm sure."

The tone and the words stung Sinclair. His face lost something of its good-humour. His lips closed tightly. A gleam of anger showed for an instant in his blue eyes. The signs of irritation passed quickly. But it was in a colder and more formal tone that he uttered some commonplaces, to which Carteret made a commonplace reply.

Slight as were the changes of tone and manner, they were not lost on Miss MacAllister. She had noted the unconscious ease with which Sinclair had met Carteret, and had been surprised at the superciliousness, almost insolence, of the latter's response. She had caught that momentary flash of the eye, betraying the rising anger, immediately brought under control.

Then as the two young men exchanged a sentence or two of polite formalities, she mentally compared them. Both were tall men—with the possible exception of her father, much the tallest men in the company. Neither was less than six feet in height. The Englishman was the slighter of the two, though fairly athletic in appearance. He was black-haired and dark-eyed. A black moustache and well-trimmed pointed beard gave him a foreign appearance and made him look older than his five-and-twenty years.

The Canadian was equally tall, but broad-shouldered and deep-chested. The massive head with its abundance of loosely-curled hair, so light in colour as to be almost golden, the clear-cut features, fair complexion, and singularly bright blue eyes reminded her of pictures of idealized Vikings she had seen at home. Perhaps it was more than a fanciful resemblance. Sinclair's forefathers had come from Caithness to Canada, and the blood of Norsemen probably flowed in his veins. Though older by a couple of years than the Englishman, Sinclair's fair, clean-shaven face looked years younger than Carteret's. In spite of the maturity of the broad, white forehead, it was almost a boyish face, with its cheerful, eager outlook on life.

"Allow me to apologize, Miss MacAllister, for having interrupted your conversation with Mr. Carteret. The consul simply projected me into the midst of it."

"A heavy projectile, Dr. Sinclair, for so light an explosive! With the thunder of the bombardment still in our ears, I suppose that we cannot help talking in terms of cannonading. But I assure you that no apologies are necessary. I am ever so glad to meet again a companion of our eventful voyage."

She looked so charmingly sincere that Sinclair wondered to himself if she really meant it.

"Attention! The consul is marshalling the company for dining-room parade," said Mr. Boville, the commissioner of customs.

"Exactly seven minutes and forty seconds late," said Carteret, looking at his watch. "Beauchamp will not recover from this for a year. He'll have to report it to the Foreign Office and ask that his leave be postponed six months as a punishment."

"Why? Is Mr. Beauchamp so particular about being punctual?" asked Miss MacAllister.

"Latest for an engagement he was ever known to be, three minutes and fifteen seconds. That was because of a typhoon."

"Pity that there were not more like him!" said the commissioner tartly.

"Commander Gardenier, you will conduct my wife to the dining-room. Mr. MacAllister, will you take in Mrs. Thomson? And Mr. Boville, Miss MacAllister. The less fortunate gentlemen will follow."

Offering his arm to Mrs. MacAllister, the consul led the way.

VI

ON THE DEFENSIVE

The commissioner of customs had the honour of conducting Miss MacAllister to the table, because his official position and his long years of residence in the island gave him precedence over the newcomers, or those who were engaged in mercantile pursuits. In appearance he was ill-suited to be the escort of such a young and queenly person. He was middle-aged, very bald, rotund in figure, and so short that his head was hardly level with her shoulder.

When she took Boville's proffered arm, she realized how absurd their disproportionate statures must appear. Involuntarily she glanced around to find Sinclair. He was just offering his arm to McLeod, for lack of a lady companion. A moment later she heard their voices at her back, and knew that they had taken their places in the little procession immediately behind her and the commissioner. Then the voices ceased, and instinctively she felt that they were laughing silently. Her figure stiffened, and she held her head a trifle higher than before. Her escort made the most of his five feet one or two, but do his best he couldn't get the shiny top of his head above her shoulder.

As they entered the dining-room she caught a glimpse of McLeod's face. He was laughing undisguisedly. When she took her place at the table she found herself facing Sinclair. He was not looking at her. He was watching the last of the guests filing in, and was trying to look unconcerned. But there was a suspicious quivering of his mouth and a sparkle in his eyes. Her quick Celtic blood took fire at once.

"He's laughing at me," she thought to herself. "How dare he? There's no limit to the presumption of those Canadians. But I'll teach him."

Strange to say, she quite forgot how she had laughed at him on board the Hailoong. Stranger still, she seemed to take no offence at the laughter of McLeod, who also was a Canadian.

As soon as they were seated, the natives out on the verandah began to pull the cords; the punkah began to wave to and fro and creak. It wouldn't have been a punkah if it hadn't creaked. The consul, who had nerves, had striven to put an end to the creaking, but had failed. The creak was an essential part of the punkah. But there was no creaking about the movements of the waiters. Noiseless as spectres, the "boys" in their long blue gowns moved quickly in and out, back and forth, their felt-soled shoes sliding silently over the smooth tiled floor.

"Commander Gardenier, we have all been models of patience. No one has asked you how the day went at Keelung. But you cannot expect us to wait much longer. Such virtue would be superhuman. Do tell the company what all the noise was about to-day and who got the better of it."

A murmur of applause greeted the consul's request, and all eyes turned towards the bronzed sailor who sat beside Mrs. Beauchamp. He seemed a little uncomfortable under the expectant gaze of so many eyes and answered modestly:

"I do not know that I can tell you much about it. The French had three ships at it. On their part the Chinese in the big new fort on the east side of the harbour and in the old fortifications on the west side were engaged. Between them they put up a pretty scrap for a while."

"Really! Did the Chinese actually pretend to offer any resistance to the French?" inquired Carteret.

"There was no pretending. They offered resistance, and a very effectual one for a time," replied Gardenier. "You know, Beauchamp, the lie of the harbour?"

The consul nodded.

"The old corvette Villars was anchored in the inner harbour, opposite the south side of Palm Island. She pelted away with her guns and mitrailleuses at the new fort at a thousand-yard range. The little gunboat Lutin lay close in shore on the west side and hammered the old fortifications there. Admiral Lespès, in La Galissonnière, lay in the outer harbour and raked both sides with his long guns."

"I should think that he would be in little danger there," said one of the merchants. "The Chinese gunners couldn't hit a range of mountains, let alone a ship, at that range."

"That is just where you are mistaken. They put three holes into La Galissonnière just above water-line, almost as soon as the game commenced. If they didn't beat off the French to-day, it was not the fault of their gunners. It was because their works could not stand the French fire. The Chinese worked their guns till their forts were knocked to pieces."

"Did the French land any men?" inquired Boville.

"Yes," replied Gardenier. "When we left Keelung, a landing-party of marines had just hoisted the French flag on the ruined Chinese fort."

"Then Keelung is in the hands of the French?"

"Yes. That is if by Keelung you mean a strip of a few hundred feet wide around the harbour. But the hills all around that again are occupied by the Chinese."

"Little difference that will make," said Carteret. "The Celestials have had all they want. At the first sign of a French advance they'll run, and never stop running till they reach Taipeh."

"I'm not so sure about that," replied Gardenier, a trifle coldly. "In the first place, the French have no land forces with which to make an advance. In the second place, the Chinese are better fighters than you give them credit for, Mr. Carteret. All they need is a good leader, and I believe that they have such a man in Liu Ming-chuan."

"And in the third place," said Beauchamp, "the Keelung climate is enough to defeat the French if there were no Chinese. By the time their transports arrive the northeast monsoon will be about due. Then the Lord help them! One of the wettest spots on earth. Boville, what is the annual rainfall over there?"

"One hundred and fifty-eight inches on the average. One year it lacked only an inch and a half of the two hundred."

"One hundred and fifty-eight inches," repeated MacAllister. "That does not convey much meaning to my mind. How does it compare with some climates we do know? That of London, for example?"

"Ashamed to say that I don't know London's rainfall," said the consul. "All I remember is that it seemed to do little else but rain there when I was a boy. Boville? ... Carteret? ... You are Londoners.... What? Do none of you know? ... Shocking ignorance!"

"I do not want to put forward my opinion on the climate of London in a company of Englishmen," said Sinclair; "but I believe the rainfall there is about twenty-five inches."

"Easy seeing that you have not lived in England," said Carteret, with the same contemptuous tone he had already used when introduced to Sinclair. "A hundred inches would be more like it."