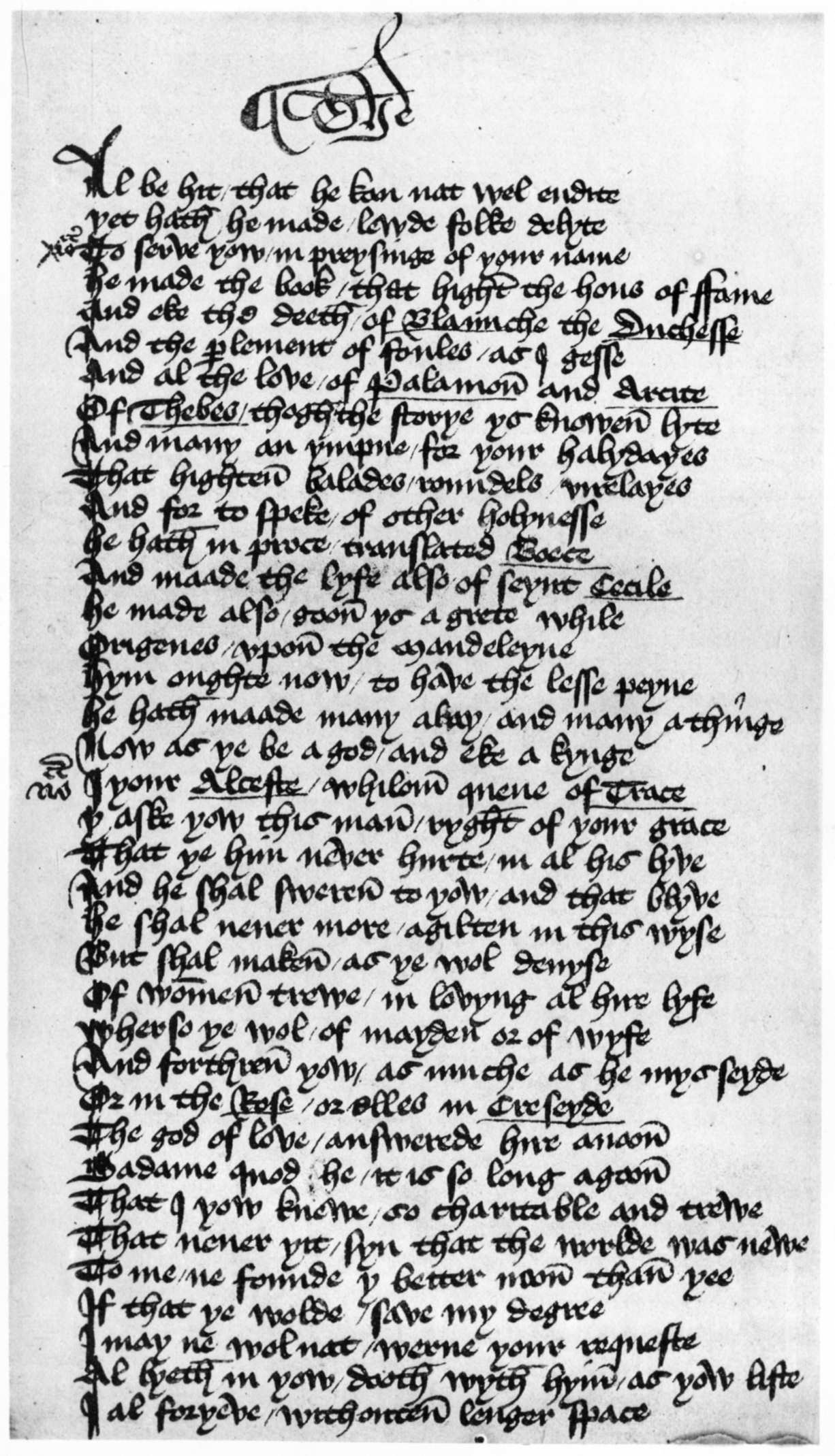

MS. Fairfax 16. Legend of Good Women, 414-450

Frontispiece***

Project Gutenberg's Chaucer's Works, Volume 3 (of 7), by Geoffrey Chaucer

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Chaucer's Works, Volume 3 (of 7)

The House of Fame; The Legend of Good Women; The Treatise

on the Astrolabe; The Sources of the Canterbury Tales

Author: Geoffrey Chaucer

Editor: Walter Skeat

Release Date: February 27, 2014 [EBook #45027]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHAUCER'S WORKS, VOLUME 3 (OF 7) ***

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

In this edition the two versions of the Prologue to the Legend are each assembled for continuous reading. Page numbers {66a} etc. refer to the upper parts of the printed pages, {66b} etc. refer to the lower parts. Skeat's commentary on the Astrolabe (mentioned in the text as "Footnotes") has been similarly separated from Chaucer's text. A Glossary including words from the texts in this volume is included in Skeat's Volume VI, available from Project Gutenberg at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/43097/43097-h/43097-h.htm. |

THE COMPLETE WORKS

OF

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

EDITED, FROM NUMEROUS MANUSCRIPTS

BY THE

Rev. WALTER W. SKEAT, M.A.

Litt.D., LL.D., D.C.L., Ph.D.

ELRINGTON AND BOSWORTH

PROFESSOR OF ANGLO-SAXON

AND FELLOW OF CHRIST'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

* * *

THE HOUSE OF FAME: THE LEGEND OF

GOOD WOMEN

THE TREATISE ON THE ASTROLABE

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE SOURCES OF THE CANTERBURY TALES

'He made the book that hight the Hous of Fame.'

Legend of Good Women; 417.

'Who-so that wol his large volume seke

Cleped the Seintes Legende of Cupyde.'

Canterbury Tales; B 60.

'His Astrelabie, longinge for his art.'

Canterbury Tales; A 3209.

SECOND EDITION

Oxford

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

M DCCCC

Oxford

PRINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

BY HORACE HART, M.A.

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

| PAGE | |

| Introduction to the House of Fame.—§ 1. Authorship. § 2. Influence of Dante. § 3. Testimony of Lydgate. § 4. Influence of Ovid. § 5. Date of the Poem. § 6. Metre. § 7. Imitations. § 8. Authorities. § 9. Some Emendations | vii |

| Introduction to the Legend of Good Women.—§ 1. Date of the Poem. § 2. The Two Forms of the Prologue. § 3. Comparison of these. § 4. The Subject of the Legend. § 5. The Daisy. § 6. Agaton. § 7. Chief Sources of the Legend. § 8. The Prologue; Legends of (1) Cleopatra; (2) Thisbe; (3) Dido; (4) Hypsipyle and Medea; (5) Lucretia; (6) Ariadne; (7) Philomela; (8) Phyllis; (9) Hypermnestra. § 9. Gower's Confessio Amantis. § 10. Metre. § 11. 'Clipped' Lines. § 12. Description of the MSS. § 13. Description of the Printed Editions. § 14. Some Improvements in my Edition of 1889. § 15. Conclusion | xvi |

| Introduction to a Treatise on the Astrolabe.—§ 1. Description of the MSS. §§ 2-16. MSS. A., B., C., D., E., F., G., H., I., K., L., M., N., O., P. § 17. MSS. Q., R., S., T., U., W., X. § 18. Thynne's Edition. § 19. The two Classes of MSS. § 20. The last five Sections (spurious). § 21. Gap between Sections 40 and 41. § 22. Gap between Sections 43 and 44. § 23. Conclusion 40. § 24. Extant portion of the Treatise. § 25. Sources. § 26. Various Editions. § 27. Works on the Subject. § 28. Description of the Astrolabe Planisphere. § 29. Uses of the Astrolabe Planisphere. § 30. Stars marked on the Rete. § 31. Astrological Notes. § 32. Description of the Plates | lvii |

| Plates illustrating the description of the Astrolabe | lxxxi |

| The Hous of Fame: Book I. | 1 |

| The Hous of Fame: Book II. | 16 |

| The Hous of Fame: Book III. | 33 |

| 65 | |

| XVIII. The Legend of Cleopatra | 106 |

| XVIII. The Legend of Thisbe | 110 |

| XVIII. The Legend of Dido | 117 |

| XIIIV. The Legend of Hypsipyle and Medea | 131 |

| XIIIV. The Legend of Lucretia | 140 |

| XIIVI. The Legend of Ariadne | 147 |

| XIVII. The Legend of Philomela | 158 |

| XVIII. The Legend of Phyllis | 164 |

| VIIIX. The Legend of Hypermnestra | 169 |

| A Treatise on the Astrolabe | 175 |

| Critical Notes to a Treatise on the Astrolabe | 233 |

| Notes to the House of Fame | 243 |

| Notes to the Legend of Good Women | 288 |

| Notes to a Treatise on the Astrolabe | 352 |

| An Account of the Sources of the Canterbury Tales | 370 |

§ 1. It is needless to say that this Poem is genuine, as Chaucer himself claims it twice over; once in his Prologue to the Legend of Good Women, l. 417, and again by the insertion in the poem itself of the name Geffrey (l. 729)[1].

§ 2. Influence of Dante. The influence of Dante is here very marked, and has been thoroughly discussed by Rambeau in Englische Studien, iii. 209, in an article far too important to be neglected. I can only say here that the author points out both general and particular likenesses between the two poems. In general, both are visions; both are in three books; in both, the authors seek abstraction from surrounding troubles by venturing into the realm of imagination. As Dante is led by Vergil, so Chaucer is upborne by an eagle. Dante begins his third book, Il Paradiso, with an invocation to Apollo, and Chaucer likewise begins his third book with the same; moreover, Chaucer's invocation is little more than a translation of Dante's.

Among the particular resemblances, we may notice the method of commencing each division of the Poem with an invocation[2]. Again, both poets mark the exact date of commencing their poems; Dante descended into the Inferno on Good Friday, 1300 {viii}(Inf. xxi. 112); Chaucer began his work on the 10th of December, the year being, probably, 1383 (see note to l. 111).

Chaucer sees the desert of Lybia (l. 488), corresponding to similar waste spaces mentioned by Dante; see note to l. 482. Chaucer's eagle is also Dante's eagle; see note to l. 500. Chaucer gives an account of Phaethon (l. 942) and of Icarus (l. 920), much like those given by Dante (Inf. xvii. 107, 109); both accounts, however, may have been taken from Ovid[3]. Chaucer's account of the eagle's lecture to him (l. 729) resembles Dante's Paradiso, i. 109-117. Chaucer's steep rock of ice (l. 1130) corresponds to Dante's steep rock (Purg. iii. 47). If Chaucer cannot describe all the beauty of the House of Fame (l. 1168), Dante is equally unable to describe Paradise (Par. i. 6). Chaucer copies from Dante his description of Statius, and follows his mistake in saying that he was born at Toulouse; see note to l. 1460. The description of the house of Rumour is also imitated from Dante; see note to l. 2034. Chaucer's error of making Marsyas a female arose from his misunderstanding the Italian form Marsia in Dante; see note to l. 1229.

These are but some of the points discussed in Rambeau's article; it is difficult to give, in a summary, a just idea of the careful way in which the resemblances between these two great poets are pointed out. I am quite aware that many of the alleged parallel passages are too trivial to be relied upon, and that the author's case would have been strengthened, rather than weakened, by several judicious omissions; but we may fairly accept the conclusion, that Chaucer is more indebted to Dante in this poem than in any other; perhaps more than in all his other works put together.

It is no longer possible to question Chaucer's knowledge of Italian; and it is useless to search for the original of The House of Fame in Provençal literature, as Warton vaguely suggests that we should do (see note to l. 1928). At the same time, I can see no help to be obtained from a perusal of Petrarch's Trionfo della Fama, to which some refer us.

§ 3. Testimony of Lydgate. It is remarkable that Lydgate {ix}does not expressly mention The House of Fame by name, in his list of Chaucer's works. I have already discussed this point in the Introduction to vol. i. pp. 23, 24, where I shew that Lydgate, nevertheless, refers to this work at least thrice in the course of the poem in which his list occurs; and, at the same time, he speaks of a poem by Chaucer which he calls 'Dant in English,' to which there is nothing to correspond, unless it can be identified with The House of Fame[4]. We know, however, that Lydgate's testimony as to this point is wholly immaterial; so that the discussion as to the true interpretation of his words is a mere matter of curiosity.

§ 4. Influence of Ovid. It must, on the other hand, be obvious to all readers, that the general notion of a House of Fame was adopted from a passage in Ovid's Metamorphoses, xii. 39-63. The proof of this appears from the great care with which Chaucer works in all the details occurring in that passage. He also keeps an eye on the celebrated description of Fame in Vergil's Æneid, iv. 173-183; even to the unlucky rendering of 'pernicibus alis' by 'partriches winges,' in l. 1392[5].

I here quote the passage from Ovid at length, as it is very useful for frequent reference (cf. Ho. Fame, 711-24, 672-99, 1025-41, 1951-76, 2034-77):—

'Orbe locus medio est inter terrasque, fretumque,

Caelestesque plagas, triplicis confinia mundi;

{x}Unde quod est usquam, quamuis regionibus absit,

Inspicitur penetratque cauas uox omnis ad aures.

Fama tenet, summaque domum sibi legit in arce;

Innumerosque aditus, ac mille foramina tectis

Addidit, et nullis inclusit limina portis.

Nocte dieque patent. Tota est ex aere sonanti;

Tota fremit, uocesque refert, iteratque quod audit.

Nulla quies intus, nullaque silentia parte.

Nec tamen est clamor, sed paruae murmura uocis;

Qualia de pelagi, si quis procul audiat, undis

Esse solent; qualemue sonum, cum Iupiter atras

Increpuit nubes, extrema tonitrua reddunt.

Atria turba tenet; ueniunt leue uulgus, euntque;

Mixtaque cum ueris passim commenta uagantur

Millia rumorum, confusaque uerba uolutant.

E quibus hi uacuas implent sermonibus aures;

Hi narrata ferunt alio; mensuraque ficti

Crescit, et auditis aliquid nouus adicit auctor.

Illic Credulitas, illic temerarius Error,

Vanaque Laetitia est, consternatique Timores,

Seditioque repens, dubioque auctore Susurri.

Ipsa quid in caelo rerum, pelagoque geratur,

Et tellure uidet, totumque inquirit in orbem.'

A few other references to Ovid are pointed out in the Notes.

By way of further illustration, I here quote the whole of Golding's translation of the above passage from Ovid:—

'Amid the world tweene heauen and earth, and sea, there is a place,

Set from the bounds of each of them indifferently in space,

From whence is seene what-euer thing is practizde any-where,

Although the Realme be neere so farre: and roundly to the eare

Commes whatsoeuer spoken is; Fame hath his dwelling there,

Who in the top of all the house is lodged in a towre.

A thousand entries, glades, and holes are framed in this bowre.

There are no doores to shut. The doores stand open night and day.

The house is all of sounding brasse, and roreth euery way,

Reporting double euery word it heareth people say.

There is no rest within, there is no silence any-where.

Yet is there not a yelling out: but humming, as it were

The sound of surges being heard farre off, or like the sound

That at the end of thunderclaps long after doth redound

When Ioue doth make the clouds to crack. Within the courts is preace

Of common people, which to come and go do neuer ceace.

And millions both of troths and lies run gadding euery-where,

And wordes confuselie flie in heapes, of which some fill the eare

That heard not of them erst, and some cole-cariers part do play,

To spread abroade the things they heard, and euer by the way

The thing that was inuented growes much greater than before,

And euery one that gets it by the end addes somewhat more.

{xi}Light credit dwelleth there, there dwells rash error, there doth dwell

Vaine ioy: there dwelleth hartlesse feare, and brute that loues to tell

Uncertaine newes vpon report, whereof he doth not knowe

The author, and sedition who fresh rumors loues to sowe.

This Fame beholdeth what is done in heauen, on sea, and land,

And what is wrought in all the world he layes to vnderstand.'

§ 5. Date of the Poem. Ten Brink, in his Chaucer Studien, pp. 120, 121, concludes that The House of Fame was, in all probability, composed shortly after Troilus, as the opening lines reproduce, in effect, a passage concerning dreams which appears in the last Book of Troilus, ll. 358-385. We may also observe the following lines in Troilus, from Book I, 517-8:—

'Now, thonked be god, he may goon in the daunce

Of hem that Love list febly for to avaunce.'

These lines, jestingly applied to Troilus by Pandarus, are in the House of Fame, 639, 640, applied by Chaucer to himself:—

'Although thou mayst go in the daunce

Of hem that him list not avaunce.'

Again, the House of Fame preceded the Legend of Good Women, because he here complains of the hardship of his official duties (652-660); whereas, in the Prologue to the Legend, he rejoices at obtaining some release from them. We may also note the quotation from Boethius (note to l. 972). As Boethius and Troilus seem to have been written together, somewhere about 1380, and took up a considerable time, and the apparent date of the Legend is 1385, the probable date of the House of Fame is about 1383 or 1384. Ten Brink further remarks that the references to Jupiter suggest to the reader that the 10th of December was a Thursday (see note to 111). This would give 1383 for beginning the poem; and perhaps no fitter date than the end of 1383 and the spring of 1384 can be found.

§ 6. Metre. Many of Chaucer's metres were introduced by him from the French; but the four-accent metre, with rime as here employed, was commonly known before Chaucer's time. It was used by Robert of Brunne in 1303, in the Cursor Mundi, and in Havelok. It is, however, of French origin, and occurs in the very lengthy poem of Le Roman de la Rose. Chaucer only employed it thrice: (1) in translating the Roman de la Rose; (2) in the Book of the Duchesse; and (3) in the present poem.

For normal lines, with masculine rimes, see 7, 8, 13, 14, 29, {xii}33, &c. For normal lines, with feminine rimes, see 1, 2, 9, 15, 18, &c. Elision is common, as of e in turne (1), in somme (6), in Devyne (14); &c. Sometimes there is a middle pause, where a final syllable need not always be elided. Thus we may read:—

'By abstinencë—or by seknesse' (25):

'In studie—or melancolious' (30):

'And fro unhappë—and ech disese' (89):

'In his substáuncë—is but air' (768).

Two short syllables, rapidly pronounced, may take the place of one:—

'I noot; but who-so of these mirácles' (12):

'By avisiouns, or bý figúres' (47).

The first foot frequently consists of a single syllable; see 26, 35, 40, 44; so also in l. 3, where, in modern English, we should prefer Unto.

The final e, followed by a consonant, is usually sounded, and has its usual grammatical values. Thus we have think-e, infin. (15); bot-e, old accus. of a fem. sb. (32); swich-e, plural (35); oft-e, adverbial (35); soft-e, with essential final e (A.S. sōfte); find-e, pres. pl. indic. (43); com-e, gerund (45): gret-e, pl. (53); mak-e, infin. (56); rod-e, dat. form used as a new nom., of which there are many examples in Chaucer (57); blind-e, def. adj. (138). The endings -ed, -en, -es, usually form a distinct syllable; so also -eth, which, however, occasionally becomes 'th; cf. comth (71). A few common words, written with final e, are monosyllabic; as thise (these); also shulde (should), and the like, occasionally. Remember that the old accent is frequently different from the modern; as in orácles, mirácles (11, 12): distaúnc-e (18), aventúres, figúres (47, 48): povért (88): málicióus (93): &c. The endings -i-al, -i-oun, -i-ous, usually form two distinct syllables.

For further remarks on Metre and Grammar, see vol. v.

§ 7. Imitations. The chief imitations of the House of Fame are The Temple of Glas, by Lydgate[6]; The Palice of Honour, by Gawain Douglas; The Garland of Laurell, by John Skelton; and {xiii}The Temple of Fame, by Pope. Pope's poem should not be compared with Chaucer's; it is very different in character, and is best appreciated by forgetting its origin.

§ 8. Authorities. The authorities for the text are few and poor; hence it is hardly possible to produce a thoroughly satisfactory text. There are three MSS. of the fifteenth century, viz. F. (Fairfax MS. 16, in the Bodleian Library); B. (MS. Bodley, 638, in the same); P. (MS. Pepys 2006, in Magdalene College, Cambridge). The last of these is imperfect, ending at l. 1843. There are two early printed editions of some value, viz. Cx. (Caxton's edition, undated); and Th. (Thynne's edition, 1532). None of the later editions are of much value, except the critical edition by Hans Willert (Berlin, 1883). Of these, F. and B., which are much alike, form a first group; P. and Cx. form a second group; whilst Th. partly agrees with Cx., and partly with F. The text is chiefly from F., with collations of the other sources, as given in the footnotes, which record only the more important variations.

§ 9. Some emendations. In constructing the text, a good deal of emendation has been necessary; and I have adopted many hints from Willert's edition above mentioned; though perhaps I may be allowed to add that, in many cases, I had arrived at the same emendations independently, especially where they were obvious. Among the emendations in spelling, I may particularise misdemen (92), where all the authorities have mysdeme or misdeme; Dispyt, in place of Dispyte (96); barfoot, for barefoot or barefote (98); proces (as in P.) for processe, as in the rest (251); delyt, profyt, for delyte, profyte (309, 310); sleighte for sleight (462); brighte[7], sighte, for bright, sight (503, 504); wighte, highte, for wight, hight (739, 740); fyn, Delphyn (as in Cx.), for fyne, Delphyne (1005, 1006); magyk, syk, for magyke, syke (1269, 1270); losenges, for losynges (1317), and frenges (as in F.) for frynges, as in the rest (1318); dispyt for dispite (1716); laughe for laugh (Cx. lawhe, 1809); delyt for delyte (P. delit, 1831); thengyn (as in Th.) for thengyne (1934); othere for other (2151, footnote). {xiv}These are only a few of the instances where nearly all the authorities are at fault.

The above instances merely relate to questions of spelling. Still more serious are the defects in the MSS. and printed texts as regards the sense; but all instances of emendation are duly specified in the footnotes, and are frequently further discussed in the Notes at the end. Thus, in l. 329, it is necessary to supply I. In 370, allas should be Eneas. In 513, Willert rightly puts selly, i.e. wonderful, for sely, blessed. In 557, the metre is easily restored, by reading so agast for agast so. In 621, we must read lyte is, not lytel is, if we want a rime to dytees. In 827, I restore the word mansioun; the usual readings are tautological. In 911, I restore toun for token, and adopt the only reading of l. 912 that gives any sense. In 1007, the only possible reading is Atlantes. In 1044, Morris's edition has biten, correctly; though MS. F. has beten, and there is no indication that a correction has been made. In 1114, the right word is site; cf. the Treatise on the Astrolabe (see Note). In 1135, read bilt (i.e. buildeth); bilte gives neither sense nor rhythm. In 1173, supply be. Ll. 1177, 1178 have been set right by Willert. In 1189, the right word is Babewinnes[8]. In 1208, read Bret (as in B.). In 1233, read famous. In 1236, read Reyes[9]. In 1303, read hatte, i.e. are named. In 1351, read Fulle, not Fyne. In 1372, adopt the reading of Cx. Th. P., or there is no nominative to streighte; and in 1373, read wonderliche. In 1411, read tharmes (= the armes). In 1425, I supply and hy, to fill out the line. In 1483, I supply dan; if, however, poete is made trisyllabic, then l. 1499 should not contain daun. In 1494, for high the, read highte (as in l. 744). In 1527, for into read in. In 1570, read Up peyne. In 1666, 1701, and 1720, for werkes read werk. In 1702, read clew (see note)[10]. In 1717, lyen is an error for lyuen, i.e. live. In 1750, read To, not The. In 1775, supply ye; or there is no sense. In 1793, supply they for a like reason. In 1804, 5, supply the, and al; for the scansion. In 1897, read {xv}wiste, not wot. In 1940, hattes should be hottes; this emendation has been accepted by several scholars. In 1936, the right word is falwe, not salwe (as in Morris). In 1960, there should be no comma at the end of the line, as in most editions; and in 1961, 2 read werre, reste (not werres, restes). In 1975, mis and governement are distinct words. In 2017, frot[11] is an error for froyt; it is better to read fruit at once; this correction is due to Koch. In 2021, suppress in after yaf. In 2049, for he read the other (Willert). In 2059, wondermost is all one word. In 2076, I read word; Morris reads mothe, but does not explain it, and it gives no sense. In 2156, I supply nevene.

I mention these as examples of necessary emendations of which the usual editions take no notice.

I also take occasion to draw attention to the careful articles on this poem by Dr. J. Koch, in Anglia, vol. vii. App. 24-30, and Englische Studien, xv. 409-415; and the remarks by Willert in Anglia, vii. App. 203-7. The best general account of the poem is that in Ten Brink's History of English Literature.

In conclusion, I add a few 'last words.'

L. 399. We learn, from Troil. i. 654, that Chaucer actually supposed 'Oënone' to have four syllables. This restores the metre. Read:—And Paris to Oënone.

503. Read 'brighte,' with final e; 'bright' is a misprint.

859. Compare Cant. Tales, F 726.

1119. 'To climbe hit,' i.e. to climb the rock; still a common idiom.

2115. Compare Cant. Tales, A 2078. Perhaps read 'wanie.'

§ 1. Date of the Poem: A.D. 1385. The Legend of Good Women presents several points of peculiar, I might almost say of unique interest. It is the immediate precursor of the Canterbury Tales, and enables us to see how the poet was led on towards the composition of that immortal poem. This is easily seen, upon consideration of the date at which it was composed.

The question of the date has been well investigated by Ten Brink; but it may be observed beforehand that the allusion to the 'queen' in l. 496 has long ago been noticed, and it has been thence inferred, by Tyrwhitt, that the Prologue must have been written after 1382, the year when Richard II. married his first wife, the 'good queen Anne.' But Ten Brink's remarks enable us to look at the question much more closely.

He shows that Chaucer's work can be clearly divided into three chief periods, the chronology of which he presents in the following form[12].

First Period.

1366 (at latest). The Romaunt of the Rose.

1369. The Book of the Duchesse.

1372. (end of the period).

{xvii}Second Period.

1373. The Lyf of Seint Cecile.

1373. The Assembly of Foules.

1373. Palamon and Arcite.

1373. Translation of Boethius.

1373. Troilus and Creseide.

1384. The House of Fame.

Third Period.

1385. Legend of Good Women.

1385. Canterbury Tales.

1391. Treatise on the Astrolabe.

It is unnecessary for our present purpose to insert the conjectured dates of the Minor Poems not here mentioned.

According to Ten Brink, the poems of the First Period were composed before Chaucer set out on his Italian travels, i.e. before December, 1372, and contain no allusions to writings by Italian authors. In them, the influence of French authors is very strongly marked.

The poems of the Second Period (he tells us) were composed after that date. The Life of Seint Cecile already marks the author's acquaintance with Dante's Divina Commedia; lines 36-51 are, in fact, a free translation from the Paradiso, canto xxxiii. ll. 1-21. See my note to this passage, and the remarks on the 'Second Nun's Tale' in vol. v. The Parlement of Foules contains references to Dante and a long passage translated from Boccaccio's Teseide; see my notes to that poem in vol. i. The original Palamon and Arcite was also taken from the Teseide; for even the revised version of it (now known as the Knightes Tale, and containing, doubtless, much more of Chaucer's own work) is founded upon that poem, and occasionally presents verbal imitations of it. Troilus is similarly dependent upon Boccaccio's Filostrato. The close connexion between Troilus and the translation of Boethius is seen from several considerations, of which it may suffice here to mention two. The former is the association of these two works in Chaucer's lines to Adam—

'Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee befalle

Boece or Troilus to wryten newe.'

Minor Poems; see vol. i. p. 379.

And the latter is, the fact that Chaucer inserts in Troilus (book iv. {xviii}stanzas 140-154) a long passage on predestination and free-will, taken from Boethius, book v. proses 2, 3; which he would appear to have still fresh in his mind. It is probable that his Boethius preceded Troilus almost immediately; indeed, it is conceivable that, for a short season, both may have been in hand at the same time.

There is also a close connexion between Troilus and the House of Fame, the latter of which shows the influence of Dante in a high degree; see p. vii. This connexion will appear from comparing Troil. v. stt. 52-55 with Ho. Fame, 2-54; and Troil. i. st. 74 (ll. 517-8) with Ho. Fame, 639, 640. See Ten Brink, Studien, p. 121. It would seem that the House of Fame followed Troilus almost immediately. At the same time, we cannot put the date of the House of Fame later than 1384, because of Chaucer's complaint in it of the hardship of his official duties, from much of which he was released (as we shall see) early in 1385. Further, the 10th of December is especially mentioned as being the date on which the House of Fame was commenced (l. 111), the year being probably 1383 (see Note to that line).

It would appear, further, that the Legend was begun soon after the House of Fame was suddenly abandoned, in the very middle of a sentence. That it was written later than Troilus and the House of Fame is obvious, from the mention of these poems in the Prologue; ll. 332, 417, 441. That it was written at no great interval after Troilus appears from the fact that, even while writing Troilus, Chaucer had already been meditating upon the goodness of Alcestis, of which the Prologue to the Legend says so much. Observe the following passages (cited by Ten Brink, Studien, p. 120) from Troilus, bk. v. stt. 219, 254:—

'As wel thou mightest lyen on Alceste

That was of creatures—but men lye—

That ever weren, kindest and the beste.

For whan hir housbonde was in Iupartye

To dye himself, but-if she wolde dye,

She chees for him to dye and go to helle,

And starf anoon, as us the bokes telle.

Besechinge every lady bright of hewe,

And every gentil womman, what she be,

That, al be that Criseyde was untrewe,

That for that gilt she be not wrooth with me.

{xix}Ye may hir gilt in othere bokes see;

And gladlier I wol wryten, if yow leste,

Penelopeës trouthe, and good Alceste.'

There is also a striking similarity between the argument in Troilus, bk. iv. st. 3, and ll. 369-372 (B-text) of the Prologue to the Legend. The stanza runs thus:—

'For how Criseyde Troilus forsook,

Or at the leste, how that she was unkinde,

Mot hennes-forth ben matere of my book,

As wryten folk thorugh whiche it is in minde.

Allas! that they shulde ever cause finde

To speke hir harm; and, if they on hir lye,

Y-wis, hem-self sholde han the vilanye.'

I will here also note the fact that the first line of the above stanza is quoted, almost unaltered, in the earlier version of the Prologue, viz. at l. 265 of the A-text, on p. 88.

From the above considerations we may already infer that the House of Fame was begun, probably, in December, 1383, and continued in 1384; and that the Legend of Good Women, which almost immediately succeeded it, may be dated about 1384 or 1385; certainly after 1382, when King Richard was first married. But now that we have come so near to the date, it is possible to come still nearer; for it can hardly be doubted that the extremely grateful way in which Chaucer speaks of the queen may fairly be connected with the stroke of good fortune which happened to him just at this very period. In the House of Fame we find him groaning about the troublesomeness of his official duties; and the one object of his life, just then, was to obtain greater leisure, especially if it could be had without serious loss of income. Now we know that, on the 17th of February, 1385, he obtained the indulgence of being allowed to nominate a permanent deputy for his Controllership of the Customs and Subsidies; see Furnivall's Trial Forewords to the Minor Poems, p. 25. If with our knowledge of this fact we combine these considerations, viz. that Chaucer expresses himself gratefully to the queen, that he says nothing more of his troublesome duties, and that Richard II. is known to have been a patron of letters (as we learn from Gower), we may well conclude that the poet's release from his burden was brought about by the queen's intercession with the king on his behalf. We may here {xx}notice Lydgate's remarks in the following stanza, which occurs in the Prologue to the Fall of Princes[13]:—

'This poete wrote, at the request of the quene,

A Legende, of perfite holynesse,

Of Good Women, to fynd out nynetene

That did excell in bounte and fayrenes;

But for his labour and besinesse

Was importable, his wittes to encombre,

In all this world to fynd so gret a nombre[14].'

Lydgate can hardly be correct in his statement that Chaucer wrote 'at the request' of the queen: for, had our author done so, he would have let us know it. Still, he has seized the right idea, viz. that the queen was, so to speak, the moving cause which effected the production of the poem.

It is, moreover, much to the point to observe that Chaucer's state of delightful freedom did not last long. Owing to a sudden change in the government we find that, on Dec. 4, 1386, he lost his Controllership of the Customs and Subsidies; and, only ten days later, also lost his Controllership of the Petty Customs. Something certainly went wrong, but we have no proof that Chaucer abused his privilege.

On the whole we may interpret ll. 496, 7 (p. 101), viz.

'And whan this book is maad, yive hit the quene,

On my behalfe, at Eltham[15] or at Shene,'

as giving us a date but little later than Feb. 17, 1385, and certainly before Dec. 4, 1386. The mention of the month of May in ll. 36, 45, 108, 176, is probably conventional; still, the other frequent references to spring-time, as in ll. 40-66, 130-147, 171-174, 206, &c., may mean something; and in particular we may note the reference to St. Valentine's day as being past, in ll. 145, 146; seeing that chees (chose) occurs in the past tense. We can hardly resist the conviction that the right date {xxi}of the Prologue is the spring of 1385, which satisfies every condition.

§ 2. The two forms of the Prologue. So far, I have kept out of view the important fact, that the Prologue exists in two distinct forms, viz. an earlier and a revised form. The lines in which 'the queen' is expressly mentioned occur in the later version only, so that some of the above arguments really relate to that alone. But it makes no great difference, as there is no reason to suppose that there was any appreciable lapse of time between the two versions.

In order to save words, I shall call the earlier version the A-text, and the later one the B-text. The manner of printing these texts is explained at p. 65. I print the B-text in full, in the lower half of the page. The A-text appears in the upper half of the same, and is taken from MS. C. (Camb. Univ. Library, Gg. 4. 27), which is the only MS. that contains it, with corrections of the spelling, as recorded in the footnotes. Lines which appear in one text only are marked with an asterisk (*); those which stand almost exactly the same in both texts are marked with a dagger (†) prefixed to them; whilst the unmarked lines are such as occur in both texts, but with some slight alteration. By way of example, observe that lines B. 496, 497, mentioning the queen, are duly marked with an asterisk, as not being in A. Line 2, standing the same in both texts, is marked with a dagger. And thirdly, line 1 is unmarked, because it is slightly altered. A. has here the older expression 'A thousand sythes,' whilst B. has the more familiar 'A thousand tymes.'

The fact that A. is older than B. cannot perhaps be absolutely proved without a long investigation. But all the conditions point in that direction. In the first place, it occurs in only one MS., viz. MS. C., whilst all the others give the B-text; and it is more likely that a revised text should be multiplied than that a first draft should be. Next, this MS. C. is of high value and great importance, being quite the best MS., as regards age, of the whole set; and it is a fortunate thing that the A-text has been preserved at all. And lastly, the internal evidence tends, in my opinion, to shew that B. can be more easily evolved from A. than conversely. I am not aware that any one has ever doubted this result.

We may easily see that the A-text is, on the whole, more general and vague, whilst the B-text is more particular in its references. {xxii}The impression left on my mind by the perusal of the two forms of the Prologue is that Chaucer made immediate use of the comparative liberty accorded to him on the 17th of February, 1385, to plan a new poem, in an entirely new metre, and in the new form of a succession of tales. He decided, further, that the tales should relate to women famous in love-stories, and began by writing the tale of Cleopatra, which is specially mentioned in B. 566 (and A. 542)[16]. The idea then occurred to him of writing a preface or Prologue, which would afford him the double opportunity of justifying and explaining his design, and of expressing his gratitude for his attainment of greater leisure. Having done this, he was not wholly satisfied with it; he thought the expression of gratitude did not come out with sufficient clearness, at least with regard to the person to whom he owed the greatest debt. So he at once set about to amend and alter it; the first draught, of which he had no reason to be ashamed, being at the same time preserved. And we may be sure that the revision was made almost immediately; he was not the man to take up a piece of work again after the first excitement of it had passed away[17]. On the contrary, he used to form larger plans than he could well execute, and leave them unfinished when he grew tired of them. I therefore propose to assign the conjectural date of the spring of 1385 to both forms of the Prologue; and I suppose that Chaucer went on with one tale of the series after another during the summer and latter part of the same year till he grew tired of the task, and at last gave it up in the middle of a sentence. An expression of doubt as to the completion of the task already appears in l. 2457.

§ 3. Comparison of the two forms of the Prologue. A detailed comparison of the two forms of the Prologue would extend to a great length. I merely point out some of the more remarkable variations.

The first distinct note of difference that calls for notice is at line A. 89 (B. 108), p. 72, where the line—

'When passed was almost the month of May'

is altered to—

'And this was now the firste morwe of May.'

This is clearly done for the sake of greater definiteness, and because of the association of the 1st of May with certain national customs expressive of rejoicing. It is emphasized by the statements in B. 114 as to the exact position of the sun (see note to the line). In like manner the vague expression about 'the Ioly tyme of May' in A. 36 is exchanged for the more exact—'whan that the month of May Is comen'; B. 36. In the B-text, the date is definitely fixed; in ll. 36-63 we learn what he usually did on the recurrence of the May-season; in ll. 103-124, we have his (supposed) actual rising at the dawn of May-day; then the manner in which he spent that day (ll. 179-185); and lastly, the arrival of night, his return home, his falling asleep, and his dream (ll. 197-210). He awakes on the morning of May 2, and sets to work at once (ll. 578, 579).

Another notable variation is on p. 71. On arriving at line A. 70, he puts aside A. 71-80 for the present, to be introduced later on (p. 77); and writes the new and important passage contained in B. 83-96 (p. 71). The lady whom he here addresses as being his 'very light,' one whom his heart dreads, whom he obeys as a harp obeys the hand of the player, who is his guide, his 'lady sovereign,' and his 'earthly god,' cannot be mistaken. The reference is obviously to his sovereign lady the queen; and the expression 'earthly god' is made clear by the declaration (in B. 387) that kings are as demi-gods in this present world.

In A., the Proem or true Introduction ends at l. 88, and is more marked than in B., wherein it ends at l. 102.

The passage in A. contained in ll. 127-138 (pp. 75, 76) is corrupt and imperfect in the MS. The sole existing copy of it was evidently made from a MS. that had been more or less defaced; I have had to restore it as I best could. The B-text has here been altered and revised, though the variations are neither extensive nor important; but the passage is immediately followed by about 30 new lines, in which Mercy is said to be a greater power than Right, or strict Justice, especially when Right is overcome 'through innocence and ruled curtesye'; the application of which expression is obvious.

In B. 183-187 we have the etymology of daisy, the declaration {xxiv}that 'she is the empress of flowers,' and a prayer for her prosperity, i.e. for the prosperity of the queen.

In A. 103 (p. 73), the poet falls asleep and dreams. In his dream, he sees a lark (A. 141, p. 79) who introduces the God of Love. In the B-text, the dream is postponed till B. 210 (p. 79), and the lark is left out, as being unnecessary. This is a clear improvement.

An important change is made in the 'Balade' at pp. 83, 84. The refrain is altered from 'Alceste is here' to 'My lady cometh.' The reason is twofold. The poet wishes to suppress the name of Alcestis for the present, in order to introduce it as a surprise towards the end (B. 518)[18]; and secondly, the words 'My lady cometh' are used as being directly applicable to the queen, instead of being only applicable through the medium of allegory. Indeed, Chaucer takes good care to say so; for he inserts a passage to that effect (B. 271-5); where we may remember, by the way, that free means 'bounteous' in Middle-English. We have a few additional lines of the same sort in B. 296-299.

On the other hand, Chaucer suppressed the long and interesting passage in A. 258-264, 267-287, 289-312, for no very obvious reason. But for the existence of MS. C., it would have been wholly lost to us, and the recovery of it is a clear gain. Most interesting of all is the allusion to Chaucer's sixty books of his own, all full of love-stories and personages known to history, in which, for every bad woman, mention was duly made of a hundred good ones (A. 273-277, p. 88)[19]. Important also is his mention of some of his authors, such as Valerius, Livy, Claudian, Jerome, Ovid, and Vincent of Beauvais.

If, as we have seen, Alcestis in this Prologue really meant the queen, it should follow that the God of Love really meant the king. This is made clear in B. 373-408, especially in the comparison between a just king (such as Richard, of course) and the tyrants of Lombardy. In fact, in A. 360-364, Chaucer said {xxv}a little too much about the duty of a king to hear the complaints and petitions of the people, and he very wisely omitted it in revision. In A. 355, he used the unlucky word 'wilfulhed' as an attribute of a Lombard tyrant; but as it was not wholly inapplicable to the king of England, he quietly suppressed it. But the comparison of the king to a lion, and of himself to a fly, was in excellent taste; so no alteration was needed here (p. 94).

In his enumeration of his former works (B. 417-430), he left out one work which he had previously mentioned (A. 414, 415, p. 96). This work is now lost[20], and was probably omitted as being a mere translation, and of no great account. Perhaps the poet's good sense told him that the original was a miserable production, as it must certainly be allowed to be, if we employ the word miserable with its literal meaning (see p. 307).

At pp. 103, 104, some lines are altered in A. (527-532) in order to get rid of the name of Alcestis here, and to bring in a more immediate reference to the Balade. Line B. 540 is especially curious, because he had not, in the first instance, forgotten to put her in his Balade (see A. 209); but he now wished to seem to have done so.

In B. 552-565, we have an interesting addition, in which Love charges him to put all the nineteen ladies, besides Alcestis, into his Legend; and tells him that he may choose his own metre (B. 562). Again, in B. 568-577, he practically stipulates that he is only to tell the more interesting part of each story, and to leave out whatever he should deem to be tedious. This proviso was eminently practical and judicious.

§ 4. The subject of the Legend. We learn, from B. 241, 283, that Chaucer saw in his vision Alcestis and nineteen other ladies, and from B. 557, that he was to commemorate them all in his Legend, beginning with Cleopatra (566) and ending with Alcestis (549, 550). As to the names of the nineteen, they are to be found in his Balade (555).

Upon turning to the Balade (p. 83), the names actually mentioned include some which are hardly admissible. For example, Absalom and Jonathan are names of men; Esther is hardly {xxvi}a suitable subject, whilst Ysoult belongs to a romance of medieval times. (Cf. A. 275, p. 88.) The resulting practicable list is thus reduced to the following, viz. Penelope, Marcia, Helen, Lavinia, Lucretia, Polyxena, Cleopatra, Thisbe, Hero, Dido, Laodamia, Phyllis, Canace, Hypsipyle, Hypermnestra, and Ariadne. At the same time, we find legends of Medea and Philomela, though neither of these are mentioned in the Balade. It is of course intended that the Balade should give a representative list only, without being exactly accurate.

But we are next confronted by a most extraordinary piece of evidence, viz. that of Chaucer himself, when, at a later period, he wrote the Introduction to the Man of Lawes Prologue (see vol. iv. p. 131). He there expressly refers to his Legend of Good Women, which he is pleased to call 'the Seintes Legende of Cupide,' i.e. the Legend of Cupid's Saints. And, in describing this former work of his, he introduces the following lines:—

'Ther may be seen the large woundes wyde

Of Lucresse, and of Babilan Tisbee;

The swerd of Dido for the false Enee;

The tree of Phillis for hir Demophon;

The pleinte of Dianire and Hermion,

Of Adriane and of Isiphilee;

The bareyne yle stonding in the see;

The dreynte Leander for his Erro;

The teres of Eleyne, and eek the wo

Of Brixseyde, and of thee, Ladomea;

The cruelte of thee, queen Medea,

Thy litel children hanging by the hals

For thy Iason, that was of love so fals!

O Ypermistra, Penelopee, Alceste,

Your wyfhod he comendeth with the beste!

But certeinly no word ne wryteth he

Of thilke wikke example of Canacee'; &c.

We can only suppose that he is referring to the contents of his work in quite general terms, with a passing reference to his vision of Alcestis and the nineteen ladies, and to those mentioned in his Balade. There is no reason for supposing that he ever wrote complete tales about Deianira, Hermione, Hero, Helen, Briseis, Laodamia, or Penelope, any more than he did about Alcestis. But it is highly probable that, just at the period of writing his Introduction to the Man of Lawes Prologue, he was seriously intending to take up again his 'Legend,' and was planning how to continue it. But he never did it.

On comparing these two lists, we find that the following names are common to both, viz. Penelope, Helen, Lucretia, Thisbe, Hero, Dido, Laodamia, Phyllis, Canace, Hypsipyle, Hypermnestra, Ariadne, and (in effect) Alcestis. The following occur in the Balade only, viz. Marcia, Lavinia, Polyxena, Cleopatra. And the following are mentioned in the above-quoted passage only, viz. Deianira, Hermione, Briseis, Medea. We further know that he actually wrote the Legend of Philomela, though it is in neither of the above lists; whilst the story of Canace was expressly rejected. Combining our information, and rearranging it, we see that his intention was to write nineteen Legends, descriptive of twenty women, viz. Alcestis and nineteen others; the number of Legends being reduced by one owing to the treatment of the stories of Medea and Hypsipyle under one narrative. Putting aside Alcestis, whose Legend was to come last, the nineteen women can be made up as follows:—

1. Cleopatra. 2. Thisbe. 3. Dido. 4 and 5. Hypsipyle and Medea. 6. Lucretia. 7. Ariadne. 8. Philomela. 9. Phyllis. 10. Hypermnestra (all of which are extant). Next come—11. Penelope: 12. Helen: 13. Hero: 14. Laodamia (all mentioned in both lists). 15. Lavinia: 16. Polyxena[21] (mentioned in the Balade). 17. Deianira: 18. Hermione: 19. Briseis (in the Introduction to the Man of Lawe).

This conjectural list is sufficient to elucidate Chaucer's plan fully, and agrees with that given in the note to l. 61 of the Introduction to the Man of Lawes Tale, in vol. v.

If we next enquire how such lists of 'martyred' women came to be suggested to Chaucer, we may feel sure that he was thinking of Boccaccio's book entitled De Claris Mulieribus, and of Ovid's Heroides. Boccaccio's book contains 105 tales of Illustrious Women, briefly told in Latin prose. Chaucer seems to have partially imitated from it the title of his poem—'The Legend of Good Women'; and he doubtless consulted it for his purpose. But he took care to consult other sources also, in order to be able to give the tales at greater length, so that the traces of his debt to the above work by Boccaccio are very slight.

We must not, however, omit to take notice that, whilst Chaucer {xxviii}owes but little to Boccaccio as regards his subject-matter, it was from him, in particular, that he took his general plan. This is well shewn in the excellent and careful essay by M. Bech, printed in 'Anglia,' vol. v. pp. 313-382, with the title—'Quellen und Plan der Legende of Goode Women und ihr Verhältniss zur Confessio Amantis.' At p. 381, Bech compares Chaucer's work with Boccaccio's, and finds the following points of resemblance.

1. Both works treat exclusively of women; one of them speaks particularly of 'Gode Women,' whilst the other is written 'De Claris Mulieribus.'

2. Both works relate chiefly to tales of olden time.

3. In both, the tales follow each other without any intermediate matter.

4. Both are compacted into a whole by means of an introductory Prologue.

5. Both writers wish to dedicate their works to a queen, but effect this modestly and indirectly. Boccaccio addresses his Prologue to a countess, telling her that he wishes to dedicate his book to Joanna, queen of Jerusalem and Sicily; whilst Chaucer veils his address to queen Anne under the guise of allegory.

6. Both record the fact of their writing in a time of comparative leisure. Boccaccio uses the words: 'paululum ab inerti uulgo semotus et a ceteris fere solutus curis.'

7. Had Chaucer finished his work, his last Legend would have related to Alcestis, i.e. to the queen herself. Boccaccio actually concludes his work with a chapter 'De Iohanna Hierusalem et Sicilie regina.'

See further in Bech, who quotes Boccaccio's 'Prologue' in full.

To this comparison should be added (as Bech remarks) an accidental coincidence which is even more striking, viz. that the work 'De Claris Mulieribus' bears much the same relation to the more famous one entitled 'Il Decamerone,' that the Legend of Good Women does to the Canterbury Tales.

Boccaccio has all of Chaucer's finished tales, except those of Ariadne, Philomela, and Phyllis[22]; he also gives the stories of some whom Chaucer only mentions, such as the stories of Deianira {xxix}(cap. 22), Polyxena (cap. 31), Helena (cap. 35), Penelope (cap. 38); and others. To Ovid our author is much more indebted, and frequently translates passages from his Heroides (or Epistles) and from the Metamorphoses. The former of these works contains the Epistles of Phyllis, Hypsipyle, Medea, Dido, Ariadne, and Hypermnestra, whose stories Chaucer relates, as well as the letters of most of those whom Chaucer merely mentions, viz. of Penelope, Briseis, Hermione, Deianira, Laodamia, Helena, and Hero. It is evident that our poet was chiefly guided by Ovid in selecting stories from the much larger collection in Boccaccio. At the same time it is remarkable that neither Boccaccio (in the above work) nor Ovid gives the story of Alcestis, and it is not quite certain whence Chaucer obtained it. It is briefly told in the 51st of the Fabulae of Hyginus, but it is much more likely that Chaucer borrowed it from another work by Boccaccio, entitled De Genealogia Deorum[23], where it appears amongst the fifty-one labours of Hercules, in the following words:—

'Alcestem Admeti regis Thessaliae coniugem retraxit [Hercules] ad uirum. Dicunt enim, quod cum infirmaretur Admetus, implorassetque Apollinis auxilium, sibi ab Apolline dictum mortem euadere non posse, nisi illam aliquis ex affinibus atque necessariis subiret. Quod cum audisset Alcestis coniunx, non dubitauit suam pro salute uiri concedere, et sic ea mortua Admetus liberatus est, qui plurimum uxori compatiens Herculem orauit, vt ad inferos uadens illius animam reuocaret ad superos, quod et factum est.'— Lib. xiii. c. 1 (ed. 1532).

§ 5. The Daisy. To this story Chaucer has added a pretty addition of his own invention, that this heroine was finally transformed into a daisy. The idea of choosing this flower as the emblem of perfect wifehood was certainly a happy one, and has often been admired. It is first alluded to by Lydgate, in a Poem against Self-Love (see Lydgate's Minor Poems, ed. Halliwell, p. 161):—

'Alcestis flower, with white, with red and greene,

Displaieth hir crown geyn Phebus bemys brihte.'

And again, in the same author's Temple of Glas, ll. 71-74:—

'I mene Alceste, the noble trewe wyf ...

Hou she was turned to a dayesye.'

The anonymous author of the Court of Love seized upon the same fancy to adorn his description of the Castle of Love, which, as he tells us, was—

'With-in and oute depeinted wonderly

With many a thousand daisy[es] rede as rose

And white also, this sawe I verely.

But what tho deis[y]es might do signifye

Can I not tel, saufe that the quenes floure,

Alceste, it was, that kept ther her soioure,

Which vnder Uenus lady was and quene,

And Admete kyng and souerain of that place,

To whom obeied the ladies good ninetene,

With many a thousand other bright of face[24].'

The mention of 'the ladies good ninetene' at once shews us whence this mention of Alcestis was borrowed.

In a modern book entitled Flora Historica, by Henry Phillips, 2nd ed. i. 42, we are gravely told that 'fabulous history informs us that this plant [the daisy] is called Bellis because it owes its origin to Belides, a granddaughter of Danaus, and one of the nymphs called Dryads, that presided over the meadows and pastures in ancient times. Belides is said to have encouraged the suit of Ephigeus, but whilst dancing on the green with this rural deity she attracted the admiration of Vertumnus, who, just as he was about to seize her in his embrace, saw her transformed into the humble plant that now bears her name.' It is clear that the concocter of this stupid story was not aware that Belides is a plural substantive, being the collective name of the fifty daughters of Danaus, who are here rolled into one in order to be transformed into a single daisy; and all because the words bellis and Belides happen to begin with the same three letters! It may also be noticed that 'in ancient times' the business of the Dryads was to preside over trees rather than 'over meadows and pastures.' Who the 'rural deity' was who is here named 'Ephigeus' I neither know nor care. But it is curious to observe the degeneracy of the story for which Chaucer was (in my belief) originally responsible[25]. See Notes and Queries, 7th S. vi. 186, 309.

Of course it is easy to see that this invention on the part of Chaucer is imitated from Ovid's Metamorphoses, where Clytie becomes a sun-flower, Daphne a laurel, and Narcissus, Crocus, and Hyacinthus become, respectively, a narcissus, a crocus, and a hyacinth. At the same time, Chaucer's attention may have been directed to the daisy in particular, as Tyrwhitt long ago pointed out, by a perusal of such poems as Le Dit de la fleur de lis et de la Marguerite, by Guillaume de Machault (printed in Tarbe's edition, 1849, p. 123), and Le Dittié de la flour de la Margherite, by Froissart (printed in Bartsch's Chrestomathie de l'ancien Français, 1875, p. 422); see Introduction to Chaucer's Minor Poems, in vol. i. p. 36. In particular, we may well compare lines 42, 48, 49, 60-63 of our B-text with Machault's Dit de la Marguerite (ed. Tarbé, p. 123):—

'J'aim une fleur, qui s'uevre et qui s'encline

Vers le soleil, de jour quant il chemine;

Et quant il est couchiez soubz sa courtine

Par nuit obscure,

Elle se clost, ainsois que li jours fine.'

And again, we may compare ll. 53-55 with the lines in Machault that immediately follow, viz.

'Toutes passe, ce mest vis, en coulour,

Et toutes ha surmonté de douçour;

Ne comparer

Ne se porroit nulle à li de coulour': &c.[26]

The resemblance is, I think, too close to be accidental.

We may also compare (though the resemblance is less striking) ll. 40-57 of the B-text of the Prologue (pp. 68, 69) with ll. 22-30 of Froissart's poem on the Daisy:—

'Son doulç vëoir grandement me proufite,

et pour ce est dedens mon coer escripte

si plainnement

que nuit et jour en pensant ie recite

{xxxii}les grans vertus de quoi elle est confite,

et di ensi: "la heure soit benite

quant pour moi ai tele flourette eslite,

qui de bonté et de beauté est dite

la souveraine,"' &c.

At l. 68 of the same poem, as pointed out by M. Sandras (Étude sur G. Chaucer, 1859, p. 58), and more clearly by Bech (Anglia, v. 363), we have a story of a woman named Herés—'une pucelle [qui] ama tant son mari'—whose tears, shed for the loss of her husband Cephëy, were turned by Jupiter into daisies as they fell upon the green turf. There they were discovered, one January, by Mercury, who formed a garland of them, which he sent by a messenger named Lirés to Serés (Ceres). Ceres was so pleased by the gift that she caused Lirés to be beloved, which he had never been before.

This mention of Ceres doubtless suggested Chaucer's mention of Cibella (Cybele) in B. 531. In fact, Chaucer first transforms Alcestis herself into a daisy (B. 512); but afterwards tells us that Jupiter changed her into a constellation (B. 525), whilst Cybele made the daisies spring up 'in remembrance and honour' of her. The clue seems to be in the name Cephëy, representing Cephei gen. case of Cepheus. He was a king of Ethiopia, husband of Cassiope, father of Andromeda, and father-in-law of Perseus. They were all four 'stellified,' and four constellations bear their names even to the present day. According to the old mythology, it was not Alcestis, but Cassiope, who was said to be 'stellified[27].' The whole matter is thus sufficiently illustrated.

§ 6. Agaton. This is, perhaps, the most convenient place for explaining who is meant by Agaton (B. 526). The solution of this difficult problem was first given by Cary, in his translation of Dante's Purgatorio, canto xxii. l. 106, where the original has Agatone. Cary first quotes Chaucer, and then the opinion of Tyrwhitt, that there seems to be no reference to 'any of the Agathoes of antiquity,' and adds: 'I am inclined to believe that Chaucer must have meant Agatho, the dramatic writer, whose name, at least, appears to have been familiar in the Middle Ages; for, besides the mention of him in the text, he is quoted by Dante in the Treatise de Monarchia, lib. iii. "Deus per nuncium facere {xxxiii}non potest, genita non esse genita, iuxta sententiam Agathonis."' The original is to be found in Aristotle, Ethic. Nicom. lib. vi. c. 2:—

Μόνου γὰρ ἀυτοῦ καὶ θεὸς στερίσκεται

Ἀγένητα ποιεῖν ἅσσ' ἄν ᾖ πεπραγμένα.

Agatho is mentioned by Xenophon in his Symposium, by Plato in the Protagoras, and in the Banquet, a favourite book with our author [Dante], and by Aristotle in his Art of Poetry, where the following remarkable passage occurs concerning him, from which I will leave it to the reader to decide whether it is possible that the allusion in Chaucer might have arisen: ἐν ἐνίαις μὲν ἓν ἢ δύο τῶν γνωρίμων ἐστὶν ὀνομάτων, τὰ δὲ ἄλλα πεποιημένα· ἐν ἐνίαις δὲ ὀυθέν· οἷον ἐν τῷ Ἀγάθωνος Ἄνθει. ὁμοίως γὰρ ἐν τούτῳ τά τε πράγματα καὶ τὰ ὀνόματα πεποίηται, καὶ ὀυδὲν ἧττον ἐυφραίνει. Edit. 1794, p. 33. "There are, however, some tragedies, in which one or two of the names are historical, and the rest feigned; there are even some, in which none of the names are historical; such is Agatho's tragedy called 'The Flower'; for in that all is invention, both incidents and names; and yet it pleases." Aristotle's Treatise on Poetry, by Thos. Twining, 8vo. edit. 1812, vol. i. p. 128.'

The peculiar spelling Agaton renders it highly probable that Chaucer took the name from Dante (Purg. xxii. 106), but this does not wholly suffice[28]. Accordingly, Bech suggests that he may also have noticed the name in the Saturnalia of Macrobius, an author whose Somnium Scipionis Chaucer certainly consulted (Book Duch. 284; Parl. Foules, 111). In this work Macrobius mentions, incidentally, both Alcestis (lib. v. c. 19) and Agatho (lib. ii. c. 1), and Chaucer may have observed the names there, though he obtained no particular information about them. Froissart (as Bech bids us remark), in his poem on the Daisy, has the lines:—

'Mercurius, ce dist li escripture,

trouva premier

la belle flour que j'ainc oultre mesure,' &c.

The remark—'ce dist li escripture,' 'as the book says'—may {xxxiv}well have suggested to Chaucer that he ought to give some authority for his story, and the name of Agatho (of whom he probably knew nothing more than the name) served his turn as well as another. His easy way of citing authors is probably, at times, humorously assumed; and such may be the explanation of his famous 'Lollius.' It is quite useless to make any further search.

I may add that this Agatho, or Agathon (Ἀγάθον), was an Athenian tragic poet, and a friend of Euripides and Plato. He was born about B.C. 447, and died about B.C. 400.

Lounsbury (Studies in Chaucer, ii. 402) rejects this explanation; but it is not likely that we shall ever meet with a better one.

§ 7. Chief Sources of the Legend. The more obvious sources of the various tales have frequently been pointed out. Thus Prof. Morley, in his English Writers, v. 241 (1890), says that Thisbe is from Ovid's Metamorphoses, iv. 55-166; Dido, from Vergil and Ovid's Heroides, Ep. vii; Hypsipyle and Medea from Ovid (Met. vii., Her. Ep. vi, xii); Lucretia from Ovid (Fasti, ii. 721) and Livy (Hist. i. 57); Ariadne and Philomela from Ovid (Met. viii. 152, vi. 412-676), and Phyllis and Hypermnestra also from Ovid (Her. Ep. ii. and Ep. xiv). He also notes the allusion to St. Augustine (De Civitate Dei, cap. xix.) in l. 1690, and observes that all the tales, except those of Ariadne and Phyllis[29], are in Boccaccio's De Claris Mulieribus. But it is possible to examine them a little more closely, and to obtain further light upon at least a few other points. It will be most convenient to take each piece in its order. For some of my information, I am indebted to the essay by Bech, above mentioned (p. xxviii).

§ 8. Prologue. Original. Besides mere passing allusions, we find references to the story of Alcestis, queen of Thrace (432[30], 518). As she is not mentioned in Boccaccio's book De Claris Mulieribus, and Ovid nowhere mentions her name, and only alludes in passing to the 'wife of Admetus' in two passages (Ex Ponto, iii. 1. 106; Trist. v. 14. 37), it is tolerably certain that Chaucer must have read her story either in Boccaccio's book De Genealogia Deorum, lib. xiii. c. 1 (see p. xxix), or in the Fables of Hyginus (Fab. 51). A large number of the names {xxxv}mentioned in the Balade (249) were suggested either by Boccaccio's De Claris Mulieribus, or by Ovid's Heroides; probably, by both of these works. We may here also note that the Fables of Hyginus very briefly give the stories of Jason and Medea (capp. 24, 25); Theseus and Ariadne (capp. 41-43); Philomela (cap. 45); Alcestis (cap. 51); Phyllis (cap. 59); Laodamia (cap. 104); Polyxena (cap. 110); Hypermnestra (cap. 168); Nisus and Scylla (cap. 198; cf. ll. 1904-1920); Penelope (cap. 126); and Helena (capp. 78, 92). The probability that Chaucer consulted Machault's and Froissart's poems has already been discussed; see p. xxxi.

It is interesting to note that Chaucer had already praised many of his Good Women in previous poems. Compare such passages as the following:—

'Of Medea and of Iason,

Of Paris, Eleyne, and Lavyne.'

Book of the Duch. 330.

'By as good right as Medea was,

That slow her children for Iason;

And Phyllis als for Demophon

Heng hir-self, so weylaway!

For he had broke his terme-day

To come to her. Another rage

Had Dydo, quene eek of Cartage,

That slow hir-self, for Eneas

Was fals; a! whiche a fool she was!' Id. 726.

—'as moche debonairtee

As ever had Hester in the bible.' Id. 986.

'For love of hir, Polixena— ...

She was as good, so have I reste,

As ever Penelope of Greece,

Or as the noble wyf Lucrece,

That was the beste—he telleth thus,

The Romain, Tytus Livius.' Id. 1071, 1080.

'She passed hath Penelope and Lucresse.'

Anelida; 82.

'Biblis, Dido, Tisbe and Piramus,

Tristram, Isoude, Paris, and Achilles,

Eleyne, Cleopatre, and Troilus.'

Parlement of Foules; 289.

'But al the maner how she [Dido] deyde,

And al the wordes that she seyde,

Who-so to knowe hit hath purpos,

Reed Virgile in Eneidos

{xxxvi}Or the Epistle of Ovyde,

What that she wroot or that she dyde;

And, nere hit to long to endyte,

By god, I wolde hit here wryte.'

House of Fame; 375.

The last quotation proves clearly, that Chaucer was already meditating a new version of the Legend of Dido, to be made up from the Æneid and the Heroides, whilst still engaged upon the House of Fame (which actually gives this story at considerable length, viz. in ll. 140-382); and consequently, that the Legend of Good Women succeeded the House of Fame by a very short interval. But this is not all; for only a few lines further on we find the following passage:—

'Lo, Demophon, duk of Athenis,

How he forswor him ful falsly,

And trayed Phillis wikkedly,

That kinges doghter was of Trace,

And falsly gan his terme pace;

And when she wiste that he was fals,

She heng hir-self right by the hals,

For he had do hir swich untrouthe;

Lo! was not this a wo and routhe?

Eek lo! how fals and reccheles

Was to Briseida Achilles,

And Paris to Oënone;

And Iason to Isiphile;

And eft Iason to Medea;

And Ercules to Dyanira;

For he lefte hir for Iöle,

That made him cacche his deeth, parde!

How fals eek was he, Theseus;

That, as the story telleth us,

How he betrayed Adriane;

The devel be his soules bane[31]!

For had he laughed, had he loured,

He mostë have be al devoured,

If Adriane ne had y-be[32]!' &c. Id. 387.

Here we already have an outline of the Legend of Phyllis; a reference to Briseis; to Jason, Hypsipyle, Medea, and to Deianira; a sufficient sketch of the Legend of Ariadne; and another version of the Legend of Dido.

We trace a lingering influence upon Chaucer of the Roman de la Rose; see notes to ll. 125, 128, 171. Dante is both quoted {xxxvii}and mentioned by name; ll. 357-360. Various other allusions are pointed out in the Notes.

In ll. 280, 281, 284, 305-308 of the A-text of the Prologue (pp. 89, 90), Chaucer refers us to several authors, but not necessarily in connexion with the present work. Yet he actually makes use (at second-hand) of Titus (i.e. Livy, l. 1683), and also further of the 'epistles of Ovyde.' He takes occasion to refer to his own translation of the Roman de la Rose (B. ll. 329, 441, 470), and to his Troilus (ll. 332, 441, 469); besides enumerating many of his poems (417-428).

I. The Legend of Cleopatra. The source of this legend is by no means clear. As Bech points out, some expressions shew that one of the sources was the Epitome Rerum Romanarum of L. Annæus Florus, lib. iv. c. 11; see notes to ll. 655, 662, 679. No doubt Chaucer also consulted Boccaccio's De Claris Mulieribus, cap. 86, though he makes no special use of the account there given. The story is also in the history of Orosius, bk. iv. c. 19; see Sweet's edition of King Alfred's Orosius, p. 247. Besides which, I think he may have had access to a Latin translation of Plutarch, or of excerpts from the same; see the notes.

It is worth while to note here that Gower (ed. Pauli, iii. 361) has the following lines:—

'I sigh [saw] also the woful quene

Cleopatras, which in a cave

With serpents hath her-self begrave

Al quik, and so was she to-tore,

For sorwe of that she hadde lore

Antonie, which her love hath be.

And forth with her I sigh Thisbe'; &c.

It is clear that he here refers to Chaucer's Legend of Good Women, because he actually repeats Chaucer's very peculiar account of the manner of Cleopatra's death. See § 9, p. xl. Compare L. G. W. ll. 695-697; and note that, both in Chaucer and Gower, the Legend of Thisbe follows that of Cleopatra; whilst the Legend of Philomela immediately follows that of Ariadne. This is more than mere coincidence. See Bech's essay; Anglia, v. 365.

II. The Legend of Thisbe. This is from Ovid's Metamorphoses, iv. 55-166, and from no other source. Some of the lines are closely translated, but in other places the phraseology is entirely recast. The free manner in which Chaucer treats {xxxviii}his original is worthy of study; see, as to this, the excellent criticism of Ten Brink, in his Geschichte der Englischen Litteratur, ii. 117. Most noteworthy of all is his suppression of the mythological element. The story gains in pathos in a high degree by the omission of the mulberry-tree, the colour of the fruit of which was changed from white to black by the blood of Pyramus; see note to l. 851. This is the more remarkable, because it was just for the sake of this very metamorphosis that Ovid admitted the tale into his series. See also notes to ll. 745, 784, 797, 798, 814, 835, 869, &c.; and cf. Gower's Confessio Amantis, ed. Pauli, i. 324.

III. The Legend of Dido. Chiefly from Vergil's Aeneid, books i-iv. (see note to l. 928, and compare the notes throughout); but ll. 1355-1365 are from Ovid's Heroides, vii. 1-8, quoted at length in the note to l. 1355. And see, particularly, the House of Fame, ll. 140-382. Cf. Gower, C. A. ii. 4-6[33].

IV. The Legends of Hypsipyle and Medea. The sources mentioned by Morley are Ovid's Metamorphoses, bk. vii., and Heroides, epist. vi.; to which we must add Heroides, epist. xii. But this omits a much more important source, to which Chaucer expressly refers. In l. 1396, all previous editions have the following reading—'In Tessalye, as Ovyde telleth us'; but four important MSS. read Guido for Ovyde, and they are quite right[34]. The false reading Ovyde is the more remarkable, because all the MSS. have the reading Guido in l. 1464, where a change would have destroyed the rime. As a matter of fact, ll. 1396-1461 are from Guido delle Colonne's Historia Troiana, book i. (see notes to ll. 1396, 1463); and ll. 1580-3, 1589-1655 are also from the same, book ii. (see notes to ll. 1580, 1590). Another source which Chaucer may have consulted, though he made but little use of it, was the first and second books of the Argonautica of Valerius Flaccus, expressly mentioned in l. 1457 (see notes to ll. 1457, 1469, 1479, 1509, 1558)[35]. The use made of Ovid, Met. vii., {xxxix}is extremely slight (see note to l. 1661). As to Ovid, Her. vii., xii., see notes to ll. 1564, 1670. The net result is that Guido is a far more important source of this Legend than all the passages from Ovid put together. Chaucer also doubtless consulted the fifth book of the Thebaid of his favourite author Statius; see notes to ll. 1457, 1467. Perhaps he also consulted Hyginus, whose 14th Fable gives the long list of the Argonauts, and the 15th, a sketch of the story of Hypsipyle. Compare also Boccaccio, De Claris Mulieribus, capp. 15, 16; and the same, De Genealogia Deorum, lib. xiii. c. 26. Observe also that Gower gives the story of Medea, and expressly states that the tale 'is in the boke of Troie write,' i.e. in Guido. See Pauli's edition, ii. 236.

V. The Legend of Lucretia. Chaucer refers to Livy's History (bk. i. capp. 57-59); and to Ovid (Fasti, ii. 721-852). With a few exceptions, the Legend follows the latter source. He also refers to St. Augustine; see note to l. 1690[36]. Cf. Boccaccio, De Claris Mulieribus, cap. 46, who follows Livy. Several touches are Chaucer's own; see notes to ll. 1812, 1838, 1861, 1871, 1881.

Gower has the same story (iii. 251), and likewise follows Ovid and Livy.

VI. The Legend of Ariadne. From Ovid, Met. vii. 456-8, viii. 6-182; Her. Epist. x. (chiefly 1-74); cf. Fasti, iii. 461-516. But Chaucer consulted other sources also, probably a Latin translation of Plutarch's Life of Theseus; Boccaccio, De Genealogia Deorum, lib. xi. capp. 27, 29, 30; also Vergil, Aen. vi. 20-30; and perhaps Hyginus, Fabulae, capp. 41-43. Cf. House of Fame, 405-426; and Gower, ii. 302[37].

VII. The Legend of Philomela. Chiefly from Ovid, Met. vi. 424-605; and perhaps from no other source, though the use of the word radevore in l. 2352 is yet to be accounted for. Cf. Boccaccio, De Genealogia Deorum, lib. ix. c. 8; and Gower, Conf. Amantis, ii. 313, who refers us to Ovid.

VIII. The Legend of Phyllis. Chiefly from Ovid, Her. {xl}Epist. ii.; cf. Remedia Amoris, 591-608. But a comparison with the story as told by Gower (C. A. ii. 26) shews that both poets consulted some further source, which I cannot trace. The tale is told by Hyginus (Fab. capp. 59, 243) and Boccaccio in a few lines. Cf. House of Fame, 388-396. A few lines are from Vergil, Æn. i. 85-102, 142; iv. 373. And see notes to Lydgate's Temple of Glas, ed. Schick, p. 75.

IX. The Legend of Hypermnestra. Chiefly from Ovid, Her. Epist. xiv. But Ovid calls her husband Lynceus, whereas Chaucer calls him Lino. Again, Ovid does not give the name of Lynceus' father. Chaucer not only transposes the names of the two fathers[38], but calls Ægyptus by the name of Egiste or Egistes. Hence we see that he also consulted Boccaccio, De Genealogia Deorum, lib. ii. c. 22, where we find the following account: 'Danaus Beli Prisci fuit filius, ut asserit Paulus[39], et illud idem affirmat Lactantius, qui etiam et ante Paulum Orosium, dicit Danaum Beli filium ex pluribus coniugibus .l. filias habuisse, quas cum Ægistus frater eius, cui totidem erant melioris sexus filii, postulasset in nurus, Danaus oraculi responso comperto se manibus generi moriturum, uolens euitare periculum, conscensis nauibus in Argos uenit.... Ægistus autem, quod spretus esset indignans, ut illum sequerentur filiis imperauit, lege data ut nunquam domum repeterent, ni prius Danaum occidissent. Qui cum apud Argos oppugnarent patruum, ab eo diffidente fraude capti sunt. Spopondit enim se illis iuxta Ægisti uotum filias daturum in coniuges, nec defuit promisso fides. Subornatae enim a patre uirorum intrauere thalamos singulis cultris clam armatae omnes, et cum uino laetitiaque calentes iuuenes facile in soporem iuissent, obedientes patri uirgines, captato tempore iugulauerunt uiros, unaquaeque suum, Hypermestra excepta, quae Lino seu Linceo uiro suo miserta pepercit.' We may note, by the way, that Chaucer's spelling Hypermistre is nearer to Boccaccio's Hypermestra than to the form in Ovid.

§ 9. Gower's Confessio Amantis. The relationship of {xli}Gower's Confessio Amantis to Chaucer's Legend has been investigated by Bech; in Anglia, v. 365-371. His conclusion is, that the passages in Gower which resemble Chaucer are only three at most; and I am here concerned to shew that, in two of these, the supposed resemblance is delusive.

1. In Gower's introduction, at the very beginning, ed. Pauli, i.4, we are told that, but for books, the renown of many excellent people would be lost. This seems to be copied from Chaucer's Prologue to the Legend, ll. 17-28. I have no doubt that such is the case; but we must be careful to remember that these lines by Gower form part of the prologue to his second edition, and were not written till 1393; by which time Chaucer's lines were common property, and could be imitated by any one who chose to do it; so we really learn nothing at all from this comparison.

2. In Gower, i. 45-48, there is a passage which bears some resemblance to Chaucer's Prologue to the Legend. But if it be considered impartially, I believe it will be found that the resemblance is too vague to be of any value, and cannot be relied upon. We really must not set much store by such generalities as the mention of the month of May; the address of the poet to Cupid and Venus; the wrathful aspect of Cupid; and the graciousness of Venus, who bids him disclose his malady and shrive himself. If Gower could not 'invent' such common poetical talk, he had small business to write at all. I would rather conclude, that Gower had no opportunity of seeing Chaucer's poem till somewhat later; for it is a striking fact, that, whereas Gower seized the opportunity of copying some of Chaucer's phrases in the Tale of Constance (see this discussed at p. 415), he tells several of Chaucer's Legends, such as those of Thisbe, Dido, Medea, Lucrece, Ariadne, Philomela, and Phyllis in a wholly independent manner; and, when telling the tale of Alcestis (iii. 149), he had no idea that she was ever transformed into a daisy. Moreover, if he had been able to refer to the Legend, l. 1355-6, he would hardly have translated 'Maeandri' by 'king Menander' (ii. 5).

Without hesitation, I dismiss these alleged resemblances as trifling, and the deduction from them as misleading.

3. But when we come to the very end of Gower's work (iii. 357-367), the case is entirely altered, and the resemblances are striking and irrefragable. This is best seen by comparing the whole passage. Gower is in the midst of lamenting his old age, {xlii}a subject to which he afterwards returns, when he suddenly introduces a digression, in which he sees

'Cupide with his bowe bent;

And, like unto a parlement

Which were ordeined for the nones,

With him cam al the world atones

Of gentil folk, that whilom were

Lovers; I sigh hem alle there'....

'Garlondes, nought of o colour,

Some of the lefe, som of the flour,

And some of grete perles were.'

After which we are introduced to Tristram and Isolde, Jason and Hercules, Theseus and Phedra, Troilus and Criseide and Diomede, Pyramus, Dido, Phyllis, Adriane, Cleopatra, Tisbe, Progne and Philomene and Tereus, Lucrece, Alcestis; and even Ceyx and Alcyone (cf. Chaucer's youthful poem). The matter is put beyond doubt by Gower's adoption of Chaucer's peculiar account of Cleopatra's death, as already noted above; see p. xxxvii.

The conclusion to be drawn from these facts is obvious. We see that, in the year 1385, Gower had almost completed his long poem, and communicated the fact to his friend Chaucer; and Chaucer, in return, told him of the new poem (the Legend) upon which he was then himself engaged, so planned as to contain nineteen tales or sections, and likely to extend to some 6,000 lines. Moreover, it was written in a new metre, such as no Englishman had ever employed before. Gower was allowed to see the MS. and to read a considerable portion of it. He was so struck with it as to make room for some remarks about it; and even went out of his way to introduce a personal reference to his friend. He makes Venus say to himself (iii. 374):—

'And grete wel Chaucer, whan ye mete,

As my disciple and my poete....

Forthy now, in his dayes olde[40],

Thou shall telle him this message,

That he, upon his later age[40],

{xliii}To sette an ende of alle his werke,

As he, which is myn owne clerke,

Do make his testament of love,

(As thou hast do thy shrift above),

So that my court it may recorde.'