The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Four Corners Abroad, by Amy Ella Blanchard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Four Corners Abroad Author: Amy Ella Blanchard Release Date: February 27, 2014 [EBook #45026] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE FOUR CORNERS ABROAD *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

| I. | The Fourth in Paris | 7 |

| II. | The Day of Bastille | 25 |

| III. | Housekeeping | 43 |

| IV. | A Glimpse of Spain | 65 |

| V. | A Fiesta | 87 |

| VI. | Spanish Hospitality | 105 |

| VII. | Across the Channel | 125 |

| VIII. | In London Town | 145 |

| IX. | Work | 165 |

| X. | A Night Adventure | 187 |

| XI. | Settling Down | 209 |

| XII. | All Saints | 229 |

| XIII. | The Fairy Play and Its Consequences | 247 |

| XIV. | "Stille Nacht" | 267 |

| XV. | In the Mountains | 289 |

| XVI. | Herr Green-Cap | 313 |

| XVII. | Good-bye Munich | 335 |

| XVIII. | Jack as Champion | 357 |

| XIX. | A Youthful Guide | 377 |

| XX. | Toward the Toe | 397 |

| Jean with a pigeon on each shoulder was perfectly happy | Frontispiece | ||

| Nan volunteered to go for supplies | Facing | page | 52 |

| Mary Lee was snapping her fingers and taking her steps | " | " | 96 |

| Jo managed to get next to the driver | " | " | 150 |

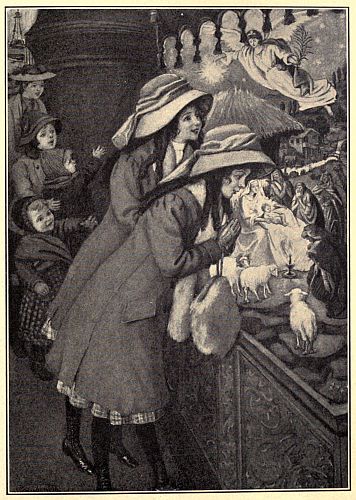

| The children stood in awe and delight at the Krippen | " | " | 270 |

It was at Passy that a little party of American girls were discussing the afternoon's plans one day in July. The three older girls were most interested; the two younger were too much engrossed in a game of Diabolo to notice very much what the others were talking about.

"You see it's raining," said Nan Corner, a tall girl with dark hair, "so we can't go in the Bois as we intended."

"Neither do we want to follow Aunt Helen's example and go hunting for antiques," put in Nan's sister, Mary Lee. "What do you say we do, Jo?"

Jo Keyes was drumming on the window-pane and looking out at the rather unpromising weather. "I see an American flag, girls," she said. "Hail to you, Old Glory!—Goodness me!" She turned around. "Do you all know what day it is? Of course we must do something patriotic."

"It's the Fourth of July!" exclaimed Nan, "and we never thought of it. For pity's sake! Isn't it ridiculous? We never made very much[10] of it at home, but over here I feel so American when I remember Bunker Hill and Yorktown and our own Virginia Washington, that I could paint myself red, white and blue, and cry 'Give me liberty or give me death,' from out the front window."

"I beg you'll do no such thing," said Mary Lee, the literal.

Nan laughed. The twins stopped their play and began to take an interest in what was being said. "Do paint your face red, white and blue and lean out the front window, Nan," said Jack; "it would be so funny."

"Let Mary Lee do it," said Nan, putting her arm around her little sister; "she's already red, white and blue."

"Let me see, Mary Lee, let me see," said Jack, eagerly.

The others laughed. "Blue eyes, white nose, red lips," said Nan, touching with her finger these features of Mary Lee's.

"You fooled me," said Jack disgustedly. "I thought she might have lovely stripes or something on her face."

"Foolish child," returned Nan, giving her a squeeze. "We must do something, girls, and look 'how it do rain,' as Mitty would say."

"Can't we have torpedoes or firecrackers or some kind of fireworks?" asked Jean.

"The gendarmes might come and rush us all off to the police court if we did," Jo told her. "They're so terribly particular here in Paris, that if a cab or an auto runs over you, you have to pay damages for getting in the way."

"Thank heaven we're Americans," said Nan fervently. "I am more eager than ever to flaunt my colors. Of all unjust things I ever heard it is to run you down and make you pay for it. They needn't talk to me about their liberté, fraternité, and egalité. I'll give a centime to the first one who thinks a happy thought for celebrating, myself included."

Jo was the first with a suggestion. "Let's have a tea and invite the grown-ups, your mother and Miss Helen. We might ask that nice Miss Joyce, too. We can have red, white and blue decorations and dress ourselves in the national colors, and it will be fine."

"The centime is yours," cried Nan. "You always were a good fellow with ideas, Jo. Now let's set our wits to work. Who dares brave the elements with me? I shall have to go foraging in the neighborhood."

"I'll go," cried Jack.

"I'd love to go foraging," said Jean.

"If you want any assistance in carrying bundles, I'm your man," said Jo.

"Then you twinnies would better stay at home with Mary Lee," said Nan.

"But we do want to go, too," begged the two.

"I don't see why you want to get yourselves all drabbled, and very likely you'd take cold," remarked Mary Lee. "For my part I'd much rather stay in."

This quite satisfied Jean, but Jack still pouted until Nan suggested that she help Mary Lee arrange the room and think up their costumes; then the two oldest girls with umbrellas, rubbers and waterproofs set out. Mrs. Corner and Miss Helen had gone to the city to attend to some business at their banker's and would not return till later, therefore, the girls concluded, it would be an excellent time to try their ingenuity; they had been accustomed to do such things before now and their imaginations, never rusty at any time, were in good working order.

"I know what I shall do," said Mary Lee, as soon as the door closed after Nan and Jo. "I shall sew red stripes on one of my white frocks. I have some Turkey red I was going to make into a bag; I'll use that."

"What can we do?" queried Jean.

"We shall have to get the room ready first," Mary Lee told her, "and then we'll think of our dresses. Go into Aunt Helen's room, Jack, and[13] get all the red Baedekers you can find, and if you see any blue books, bring them, too. Jean, go into all our rooms and bring any red-border towels you see."

"What are you going to do with them?" asked Jean, pausing at the door.

"You'll see. Trot along, for we haven't any too much time."

Jean ran off and presently came back with a lot of towels hanging over her arm. These Mary Lee disposed over the largest sofa pillow so as to give the effect of a series of red and white stripes, setting a blue covered cushion above the first. When Jack returned with the books, which she managed to drop at intervals between the door and the lounge, Mary Lee made neat piles on the table of the red and blue covered volumes, the white edges giving the required combination of color.

"There are a great many more red than blue ones," remarked Jack, watching the effect of Mary Lee's work. "I know what we can do, Mary Lee, we can cover some of the books. I saw some blue wrapping-paper in Aunt Helen's room."

"A good idea. Great head. Bring it along, Jack." And again Jack scampered off to return in a few minutes with the blue paper which Mary Lee used to cover the books needed.

"That does very well," she commented, surveying her work with pleased eyes. "Now we'll have to wait till Nan comes before we can finish up here. Fortunately Aunt Helen has blue and white tea things, and they will need only to be set on a red covered tray. I won't do that yet before I see what Nan and Jo bring back with them. Now, I'm going to sew the stripes on my skirt. We will see about you chicks when Nan comes."

She went off bent upon carrying out her design of wearing a red striped frock and blue tie. "I've a lovely idea," Jack whispered to her twin. "Let's go into mother's room and I'll show you." And the two disappeared closing the door behind them.

Half an hour later Nan and Jo returned. Mary Lee met them, red striped skirt in hand. "Well," she exclaimed eagerly, "did you manage to get anything?"

"Indeed we did," Jo replied. "Look at these flowers. Aren't they just the thing? We found an old woman around the corner with a cart full of flowers and we took our pick." She held up a bunch of red and white carnations with some blue corn-flowers.

"Perfect," agreed Mary Lee. "What else did you get?"

"Some red candies." Nan produced them.[15] "We shall put them in that little blue and white Japanese dish of mother's. We have a beautiful sugary white cake, and I am going to make a little American flag to stand up in the middle of it. We have some lady-fingers which we shall tie up with red, white and blue ribbons, and with bread and butter I think that will do. My, Mary Lee! you've done beautifully. It looks fine. Who thought of the red Baedekers and the blue books?"

"I did, or at least Jack helped out the idea with the blue paper covers."

"Where are the kiddies?"

"In mother's room getting ready. I've been basting these red stripes on this skirt. I've the last one nearly finished. What are you going to wear, Nan?"

"I'd copy-cat your red stripes if I had time, but I can cut out some stars and paste them on a blue belt, maybe, and wear a white shirt-waist and a red skirt. Jo has a striped red and white waist she can wear with a blue tie. We must hurry up, for time is flying and I have still the flag to make."

They skurried around and soon had everything arranged to their taste. "Now I'll make the flag," said Nan, "though I'll never get as many stars as I need on such a tiny blue ground, for there are such a number of states. Perhaps[16] I can find a scrap of that dark blue challis with the tiny white stars on it; that would do very well to paste in one corner."

Mary Lee and Jo followed her to the room which the three shared in common. The twins had a little room adjoining and from this issued a murmur of voices.

"Who has taken my paint box?" cried Nan diving down into her trunk. "I've looked everywhere for it. I was sure I left it on this table."

"I'll bet that scamp Jack has it," declared Mary Lee.

Nan opened the door leading to the next room and there beheld the two sitting on the floor, the color box between them. A mug of water stood near. Jack had just painted a series of ragged stripes across her white shoes and was regarding this decoration with much complacency. Jean was about to emulate her twin by similarly adorning the white stockings upon her slim little legs. She had carefully begun at the very top and had just made her first brush mark.

"Do you think there should be thirteen stripes?" she was asking Jack when Nan opened the door.

"You wretches!" cried the latter. "What are you doing with my paints?"

"We're just fixing up for Fourth of July," responded Jack thrusting out a brilliantly striped foot for Nan's inspection, and in consequence upsetting the mug of water over the color box.

"I should think you were just fixing up," returned Nan. "Just look at my color box. You've nearly used up a whole pan of vermilion, and now look what you have done. Get a towel, Jean, and sop it up. You've spoiled your shoes, Jack. They'll never be fit to wear again."

Jack looked ruefully at the feet in which she had taken such pride.

"Mayn't I stripe my stockings, Nan?" asked Jean looking up from her task of mopping up the water.

"No, chickie, I think you'd better not."

"But Jack has such beautiful stripes," said Jean regretfully.

"I'll tell you what you can have," said Nan. "I've a lot of red ribbons and I'll wind your sweet little pipe-stems with those."

Jean was so pleased with this idea that she did not mind the aspersions cast upon her slim legs. "That will be lovely," she agreed, "and it will save the trouble of painting. I saw it was going to be crite hard to have exactly thirteen stripes and all the same width."

Nan picked up the sloppy looking color box. "I've got to make a little flag," she said, "and as soon as that is done I'll get the ribbons for you." She bore off the colors into the next room and proceeded hastily to make her flag, sticking a bit of the starred challis in one corner for the field. When it was completed she looked around for a proper staff, and finally settled on one of her paint brushes whose pointed handle served excellently well to stick in the centre of the cake.

Having put it in place, Nan stood off to see the effect. "It doesn't look quite right," she observed. "What is the matter with it, girls?"

"You've made thirteen red stripes instead of having thirteen in all, red and white included," Mary Lee told her. She was always an exact person.

"Dear me, that's just the thing," said Nan. "Why didn't I know enough to do it right?"

"Never mind," said Jo. "Nobody will notice it, and I am sure it looks very well. Isn't the table lovely? I wish they would come."

"Oh, but I don't," returned Nan. "I've yet to dike, and I promised Jean to wind her legs for her. They will look like barbers' poles, but she'll never think of that, so please don't any one suggest it. It is so late I'll have to fling on any red, white and blue doings I can find."

"I'll wind the legs," volunteered Jo. "I'm all ready as you see, and you've had the most to do."

"Good for you," responded Nan. "I'll get the ribbons."

"Don't you think," said Jo, "that we ought to have speeches or something?" Jo was always great at that sort of thing.

"It wouldn't be bad." Nan was quick to accept the suggestion. "You get up a speech, Jo. We'll sing Yankee Doodle and Dixie to comb accompaniments, and I'll recite that poem of Emerson's about the firing of the shot heard round the world. What will you do, Mary Lee?"

"I might give a cake-walk," she replied; "that would be truly American."

"Let's all do a cake-walk," Nan suggested. "We have the cake, you see, and you can dance a breakdown, Mary Lee, and sing a plantation song."

"The programme is rolling up splendidly," said Jo. "Go along, Nan, and get dressed. If you stand here talking the guests will be here before you are ready."

Nan rushed off and, in her usual direct and expeditious manner, soon had herself arrayed. Her blue skirt, white shirt-waist and red sash gave the foundation of her costume which was[20] further enlivened by a red, white and blue cockade, made hastily of tissue-paper snatched out of various places. This she wore in her dark hair while she had put on a pair of red stockings with white shoes, the latter made resplendent by huge blue bows.

"Your get-up is fine," cried Jo, regarding her admiringly. "You always outdo every one else, Nan, and with the least fussing and the slightest amount of material. Here I've taken the trouble to put these white stars on a blue belt, and Mary Lee has basted all those stripes around her skirt, yet look at you with that dandy little cockade and those fetching blue bows which didn't take you five minutes to make."

"There they come," cried Mary Lee.

"Start the teakettle, somebody, while I go tell Miss Joyce. I hope she has not gone out." She rushed off leaving the others to begin the tea-making. On the way from Miss Joyce's room, where she fortunately found the young lady, Nan encountered Mrs. Corner and Miss Helen. "Happy Fourth of July," cried the girl. "Get your things off, please, and come right in to tea; it's all ready."

"Good child," answered Miss Helen. "We are ready for tea, for we are both tired out. There was so much red tape connected with[21] this morning's business. We'll be right in, Nan."

"You didn't get wet?"

"Fortunately we didn't, for we had a cab."

"Good! then you won't have to change your gowns. Don't stop to prink, mother dear, and come as soon as you can." She stopped to snatch a kiss from her mother and hurried back. Her costume had indicated that something out of the ordinary was going on, but the grown-ups were not prepared for what met their eyes when they entered the little sitting-room.

"Well, if this isn't just like you children," exclaimed Mrs. Corner when she saw the array.

"Is it just like them?" Miss Joyce turned with an appreciative smile. "Then all I have to say is that you have the dearest children in the world."

The entertainment began with Jo's patriotic speech which was given while the ladies drank their tea. There were sly hits at the rights and wrongs of foot passengers in Paris, references to the difficulties of the French language, to the law forbidding anything to be placed on the window-sills, to the lack of sweet potatoes and green corn, to the small portions of ice-cream served, and the whole oration was full of such humor as brought much laughter and applause. Jo was always happiest in such impromptu[22] speeches. Next each girl provided with a comb covered with tissue-paper gave a shrill rendering of Yankee Doodle and Dixie, then followed Mary Lee's breakdown, and next Nan's recitation. After this the twins, not to be outdone, sang a ridiculous negro song, patting juba as they did it. The whole performance ended with a cake-walk in which Nan and Jack surpassed themselves, taking the cake amid much laughter and applause.

"I haven't laughed so much for a year," said Miss Joyce, wiping her eyes. "I must confess to having felt rather blue this gloomy day, but you dear things have driven my homesickness so far away that I don't believe there is any danger of its coming back for a long time, certainly not while you are in the house. How did you think of all this?"

"Oh, we often do such things on the spur of the moment," Nan told her. "It's much more fun than to plan a long time ahead. We never realized what day it was till Jo chanced to see an American flag hanging from a window near by. You know down in Virginia we don't make much ado over the Fourth, but here in Paris somehow it seemed quite different, and we suddenly felt wildly patriotic, so we had to let off the steam in some way, and this idea of Jo's was very easy to carry out."

"It's been an immense success," Miss Joyce assured her. "The decorations are so original, and such costumes, I don't see how you managed to get them up in such a short time."

Nan looked down at her flaunting blue bows. "It's nothing when you're used to depending upon whatever comes handy. This blue paper happened to came around a package, and one can pinch up a couple of bows in no time; as for the other things, it just means a little ingenuity. When we were out in California we used to have a different kind of tea every week, and it was lots of fun to think up something new."

"We like to encourage our girls to exercise imagination and invention," Miss Helen remarked. "Nowadays when children are not encouraged to read the old-fashioned fairy tales, and have so many toys that they never have a chance to invent any plays for themselves, there is danger of certain fine qualities of mind being left out of the composition of the coming generation."

"I quite agree with you," said Miss Joyce. "Creatures of 'fire and dew and spirit' must feed on different mental food from the ordinary, and I'm sure your girls will always possess individuality."

"That is what we are aiming for," returned Miss Helen.

Jack's intention was so good, that she was spared a scolding on account of the shoes, and the afternoon ended happily though it continued to rain dismally. Jack, it may be said in passing, seldom allowed an occasion to go by without getting into some sort of scrape, and that she had done nothing worse than spoil a pair of inexpensive white shoes was really to her credit. Jean admired her own red strappings so unreservedly that she continued to wear the decorations till bedtime, while Nan's cockade still adorned her head at the dinner table.

"We shall pass but one more national holiday over here," she remarked, "and what's the sense of being in a foreign country if you can't remember your own sometimes! To be sure the tri-color is French, too, but it means the United States to us." So ended this Fourth of July which was a day long remembered.

Madame Lemercier smiled indulgently when the afternoon's celebration was described to her. "Ah, but you will be here on our great day," she said. "And then, my friends, you will see. Paris is gay like that upon our holiday. If you have your Forrs July, and your great Vashington, we have our Fourteen July, our day of Bastille. We must zen see ze city, ze illumination, ze dance, ze pyrotechnic at night. You will allow, madame," she turned to Mrs. Corner, "that your demoiselles have ze freedom not encouraged at ozzer time. Ve are a free peoples more as before, upon zat day. Each does as he will, but we do not abuse, no, we do not take advantage of ze liberte, for zough we rejoice we do not forget our native politeness. It will be perfectly safe, zough a gentleman escort or two will not be of objection."

"What does Bastille mean, anyway?" whispered Jack to Jean as they left the dining-room together. "Is it anything like pastilles, those funny sweet-smelling things we had in California?[28] Maybe she said Pastille, though it sounded more like Bas than Pas."

"I don't know which it was," confessed Jean. "I wasn't thinking much about anything she was saying. You'd better ask Nan; she'll know."

"Did Madame say Bas or Pas?" Jack put her question.

"She said Bastille," Nan told her, "and it isn't a bit like the pastilles you have in mind. In fact there isn't any more Bastille at all. Do you remember when we went to Mt. Vernon that we saw the big key there?"

"I believe I do remember something like a big key. What was it the key of? I forget."

"The Bastille was a great big fortress or castle, and was where they used to imprison nobles and other people who had offended the government or whom the kings wanted to get rid of. It was a very massive and strong place. Its walls were ten feet thick, and it had eight great towers. It was a terrible place, and when the Revolution began one of the first things the Revolutionists wanted to destroy was the great fortress, so they cried, 'Down with the Bastille!' Then they had a tremendous fight over it, for to the mass of people it represented the power of the monarchy, and to the monarchy and the[29] nobles it meant their greatest stronghold. At last the Revolutionists got in, and it was destroyed, blown to pieces. The fight took place on the fourteenth of July and that is why they celebrate the day as we do our Fourth. It will be good fun to see what they do, I think."

"But it is ten days off. What are we going to do till then?"

"Lawsee, you silly child, there will be plenty to do. We're going to Versailles and to St. Cloud, to the Museé de Cluny, to Père le Chaise, to the Louvre, and dozens of other places."

"I want to go up the tour Eiffel," said Jack, who delighted in such performances, the higher up the better.

"I suppose you'll not rest till you get there," returned Nan laughing.

Indeed, there was enough to do in the next ten days to keep every one busy, for each had some special wish to be fulfilled and where there were five youngsters to satisfy, there was little danger of time hanging heavily on their hands. Mary Lee loved the Jardin des Plantes, Jo never tired of the boulevards, and delighted in riding on the tops of the omnibuses. Nan reveled in the Louvre and the Museé de Cluny, Jean liked the Luxembourg gardens, the Tuilleries and the river, Jack wanted to climb to the top of every accessible steeple and tower in the city. Whenever[30] a church was being discussed her first inquiry was always, "Has it a tower?"

Paris was too full of opportunities for Jack to miss anything that was in the least feasible, and she was always so innocently unconscious of doing anything out of the way that it was hard to make her realize that she must be censured. As Miss Helen said, it was all the point of view, and from Jack's standpoint, if you did but tell the truth, did no one harm, and pursued what seemed a rational and agreeable course, why stand on the manner of doing it? She and Jean were allowed to play in the Bois within certain limits, for it was very near to their pension, and they could be found readily by one of their elders if they were wanted.

"But," said Mrs. Corner, "you must not go further without some older person with you." This order the children always fulfilled to the letter and Mrs. Corner felt perfectly safe about them.

But one morning, Jean chose to go back to the house for something she wanted, and on her return Jack was nowhere in sight. Jean waited patiently for a while, and then not daring to go beyond bounds, she returned to the house to report. Nan immediately left her practicing to go in search of her little sister. She ventured, herself, further than ever before, but after a long[31] and fruitless hunt came back to where Jean had been left as sentry, this being the spot where she had parted from her twin.

Nan was not easily scared about Jack, but this time she felt there was cause for anxiety. Suppose she had fallen into the lake; suppose she had been beguiled away by some beggar who would strip her of her clothes and hold her for a ransom. Nan had heard of such things. "I hate to go back and tell mother," she murmured.

Jean began to cry. "Oh, Nan, do you think she could have been run over by an automobile?" she asked.

Nan shook her head gravely. "I'm sure I don't know, Jean. She always manages to turn up all right, and has the most plausible reasons for doing as she does, but this time I cannot imagine where she could have gone. Mother and Aunt Helen are both at home and so are Jo and Mary Lee, so she could not have gone anywhere with one of them." She again looked anxiously up the road.

"Oh, there she is," suddenly cried Jean in joyful tones.

"Where? Where?" cried Nan grasping Jean's shoulder.

"In that cab coming this way. Don't you see her?"

Nan waited till the cab stopped, then she rushed forward to see Jack clamber down from the side of the red-faced cocher, shake hands with two gaudily dressed women of the bourgeois class, and walk calmly off while the cab drove on.

"Jack Corner!" cried Nan, not refraining from giving the child a little shake, "where have you been? Do you know you have scared Jean and me nearly to death? Poor little Jean has been crying her eyes out about you."

"What for?" asked Jack with a look of surprise.

"Because she was afraid you had been run over or had fallen in the lake. Where have you been?"

"Just taking a ride around," said Jack nonchalantly. "You might have known, Nan," she went on in a tone of injured innocence, "that I wouldn't go anywhere without an older person when mother said we were not to, and there were three older persons with me."

"But didn't you realize that Jean wouldn't know where you had gone, and that she would be frightened about you?"

"I didn't think we would be gone so long," returned Jack. "You see I know the cocher quite well. He has a dear little dog he lets me[33] play with sometimes. Aunt Helen always tries to have this man when she can, so to-day when he asked me if I didn't want to ride back with him, he was going back to the stand, you see, I said, Oui, monsieur, de tout mon cœur, and so I got up. Then just as we were going to start those two ladies came along."

"Ladies!" exclaimed Nan contemptuously.

"One of them had beautiful feathers in her hat," returned Jack defiantly.

"Well, never mind. Go on."

"They wanted to take a drive, but they wanted to pay very little for it, and finally the cocher said if I could go, too, he would take them for a franc and a half. So they went and they stopped quite a time; we had to wait, the cocher and I."

"Where was the place?"

"I don't know. It was somewhere that you get things to eat and drink. They didn't ask me to take any of what they were having."

"I should hope not. So then you waited, and the cocher brought you back?"

Jack nodded. "Hm, hm. He was going to take the ladies further, so when I saw you and Jean I said I would get down, and here I am all safe and sound," she added cheerfully.

"You ought to be spanked and put to bed," said Nan severely.

Jack looked at her with wide-eyed reproach. "Why, Nan," she said, "I didn't do a thing to make you say that. He is a very nice cocher; his name is François, and I am sure I minded mother. It would have been quite different if I had gone off anywhere alone. Mother said an older person, and François is very old; he must be forty."

"Well," returned Nan, "mother will tell you that you are not to go anywhere with strange cochers, or strange any other persons, and that will be the last of that sort of performance."

Jack gave a deep sigh, as of one misunderstood. It was very hard to keep up with the exactions of her family who were continually hedging her about with some new condition.

After this the days passed quietly till the fourteenth came around. Madame Lemercier pronounced the city deserted, while Miss Joyce declared it might be by Parisians, but was taken possession of by American tourists. The Corners, however, wondered whether it could be possible that it ever held any more than those who crowded the streets that evening when they all set out to see the sights. Along the Seine they concluded they would be able to see more than elsewhere, so they made the Louvre and the Palais Royal their destination. The streets were full of a good-natured, jostling throng.[35] Every now and then the party would come upon some dancers footing it gaily in some "place" or at some street corner. The cafés were thronged, and there were venders of all sorts driving a thriving trade. From the bridges ascended splendid fireworks which were continually cheered by the gaping spectators. Illuminations brightened the entire way. No one forbade joking, singing students to walk abreast so they would take up the entire sidewalk, for no one minded walking around them.

"One can scarcely imagine what it must have been during that dreadful Reign of Terror," said Nan to her aunt when they reached the "Place de la Concorde." "This jolly, contented crowd of people is very different from the bloodthirsty mob that gloried in the guillotine then. Just over there the guillotine was set up, wasn't it? And, somewhere near, those horrible fishwives sat knitting and telling of the number of the poor victims. I think this 'Place de la Concorde' is one of the most splendid spots in Paris, but I can never pass it without a shudder."

"Too much imagination on this occasion, Nan," said her aunt. "You must not let your mind dwell upon such things when you are trying to have a good time. One could be miserable[36] anywhere, remembering past history. I am sure to-night doesn't suggest an angry mob. Don't let us lose our party. We must keep an eye on them. I thought I saw Jack wriggle ahead, through the crowd, by herself."

"I'll dash on and get her," said Nan, "and stand still till you all come up." She managed to get hold of Jack before the child was wholly swallowed up in the crowd, and cautioned her to keep close to the others if she would not lose them.

But Jack was always resourceful and independent. "It wouldn't make any difference if I did lose you all," she declared. "I could find my way back, and the concierge would let me in."

"That cross old creature? I shouldn't like to bother him," returned Nan. "He is an old beast."

"Oh, no, he isn't always. If you call him monsieur often enough he gets quite pleasant," Jack assured her.

"I'll be bound for you," Nan answered. "We must stand here, Jack, till the others come up. Don't you think it is fun? I can't imagine where so many people came from, all sorts and conditions."

"I think it is very nice," returned Jack, "but[37] I wish Carter were here with his automobile, and I wish he were here anyhow, so he could dance with me. I'd love to go dance out in the street with the rest of the people. Won't you come dance with me, Nan?"

"I'd look pretty, a great long-legged girl like me in a crowd of French 'bonnes' and 'blanchisseuse,' wouldn't I? Suppose we should be seen by some of our friends, what would they think to see me twirling around in the midst of such a gang as this?"

But in spite of this scoffing on Nan's part, Jack was not easily rid of her desire, and looked with longing eyes upon each company of dancers they passed. Nan managed to keep a pretty strict lookout for her little sister, but finally she escaped in an unguarded moment, and was suddenly missed.

"She is the most trying child," said Mary Lee, who had experienced no difficulty in keeping the tractable Jean in tow.

"Jack gets so carried away by things of the moment," said Nan, always ready to make excuses for her little sister. "She gets perfectly lost to everything but what is interesting her at the time, and forgets to keep her mind on anything else. I'll go ahead as I did before, and probably I shall find her."

But no Jack was to be discovered. Mary[38] Lee scolded, Jean began to cry and Mrs. Corner looked worried.

"We can't leave the child by herself in the streets of Paris on such a night as this," she said anxiously. "There is no telling what might happen to her."

"Don't bother, mother dear," said Nan. "I'm sure she can't be a great way off. You and some of the others stand here, and I'll go ahead with Aunt Helen. We'll come back to you in a few minutes."

"I verily believe I caught a glimpse of her," suddenly exclaimed Jo.

"Where?" asked Nan, craning her neck.

"Over there where you hear the music."

"She's possessed about the dancing in the streets, and very likely she is watching the dancing."

They all moved over in the direction from which the music came, and there, sure enough, in the centre of a company of dancers, was Jack with a round black-whiskered Frenchman, whirling merrily to the strains of a violin.

Nan and her Aunt Helen edged their way to the outskirts of the circle of onlookers, and then Nan forced herself nearer. "Jack," she called. "Jack, come right here."

Jack cast a glance over her shoulder, gave several more twirls, and was finally surrendered[39] to her proper guardians by the rotund Frenchman who made a low bow with heels together as he bade adieu to his little partner.

"I did it, Nan, I did it," announced Jack joyfully. "He was a nice man and he called me la petite Americaine. He has a brother in New York and was so pleased when I told him I had been there. He is a barber and he gave me a flower." She produced a rose proudly.

"Come right over here to mother," said Nan, paying small attention to what Jack was saying. "She is worried to death about you."

"Why?" asked Jack in her usual tone of surprise when such a condition of affairs was mentioned. "Madame Lemercier said on Bastille day every one could do just what she wanted, and I am sure I was only doing what dozens and hundreds of other people were doing. What was there wrong about it, Aunt Helen?"

She looked so aggrieved and innocent, that Miss Helen, between smiles and frowns, could only ejaculate, "Oh, Jack, Jack, there is no doing anything with you."

Even after she had joined her mother and had been told how alarmed Mrs. Corner had been, Jack could not see the least indiscretion in joining in the dance. "Anybody could do it," she said, "and you didn't have to pay a cent."

"It is the question of Jack's point of view again," said Miss Helen to Mrs. Corner. "Jack has been told that every one in Paris does as he or she chooses upon the fourteenth of July, and why not she with the rest? She could understand Nan's not caring to dance because she objected to being conspicuous; as to any other reason, it never entered the child's head." So, as usual, Jack got off with a mild reproof, and the party went on their way without further trouble, Miss Helen and Nan keeping Jack between them, and Nan never letting go for one instant her hold upon Jack's arm.

To the two youngest of the company there was a great excitement in being up so late in the Paris streets, and when they stopped at a café, less crowded than most, and in a quiet street, to have limonade gaseuze, their satisfaction was complete.

After this there was less sightseeing, for Miss Helen and Mrs. Corner had shopping to do, and Nan had an object in making the most of her time in Paris, as she was anxious to add to her knowledge of French, intending to specialize in languages when she entered college. Mary Lee, with not so correct an ear, acquired facility less easily, and Jo declared that it would be impossible for herself ever to get rid of her American accent. But it was Jack who soon picked[41] up a surprising vocabulary which she used to the utmost advantage, jabbering away with whomsoever she came in contact, be it some cocher or the learned professor who sat next her at table, the chambermaids or Madame Lemercier herself, with whom the girls had lessons. Jack had not the least self-consciousness, and never feared ridicule. Jean, more timid, would have learned little, if her twin had not urged her to exert herself, forcing her to speak when they encountered some little French girls in the Bois.

These little girls came every day for an orderly walk with their governess, and for a discreet hour of play. Jack liked their looks, and was determined to make their acquaintance. She accordingly smiled most beguilingly upon them but for some time could win no more than shy smiles in return.

"I mean to make them speak to me," she told Jean.

"How are you going to do it?" asked Jean. "Maybe their governess won't let them speak to strangers. She looks very prim."

"I reckon she only looks that way because she is French," returned Jack, nothing daunted. "I saw her watch me playing Diabolo, and I know she thinks I do it well."

"You're awfully stuck up about it," replied Jean, herself less expert.

"No, I'm not. I can play much better than some of those great big girls, and I know I can, so what is the use of pretending I don't?"

However, it was not this which won the response Jack hoped for, but it was because chance gave her the opportunity of returning a book which the governess left on a bench one day. Jack saw it after the demure little girls had gone, and she pounced upon it, carrying it triumphantly home and presenting it the next day to the owner with a polite little speech. The thanks she received made a sufficient wedge for Jack and she was soon talking affably to the little girls as well as to the governess. Jack could be the most entertaining of persons, and it was no time before she had an absorbed audience. After this it was a common occurrence for the twins to meet Paulette and Clemence in the Bois, and the little French girls were never refused permission to play with the two Americans.

"It is certainly a question which is hard to settle," said Mrs. Corner one morning to her sister-in-law. "I've just been talking to Madame, and she thinks she must go."

"Go where? What's a hard question?" asked Nan looking up from a page of translating.

"I am afraid we shall have to make a change," her mother told her. "Madame Lemercier has decided that she must close her house for the remainder of the summer and go to her sister who has taken a villa in Switzerland, filled it with demoiselles and has now fallen ill."

"There are loads and loads of pensions," returned Nan.

"Yes, but we want just the right one. This suits us in so many particulars that I am afraid we shall never chance upon its like again. Here we have pleasant, airy rooms, an adequate table, and good service. We are near the Bois, and the trams, yet we escape the noise of the city. To be sure it would be more convenient to be nearer the shops and some other things,[46] but, take it all in all, I am afraid we are going to find it hard to select. I do so hate to go the rounds; it is so very exhausting."

"Aunt Helen and I will do it. Mother must not think of wearing herself out in that way, must she, Aunt Helen?"

"Of course not," replied Miss Helen. "There is one thing you must consider, Mary, and that is your health before anything else, and we shall all raise a protest against your doing any tiring thing like hunting up pensions."

"You make me feel that I am a very worthless, doless creature," returned Mrs. Corner.

"We want to keep you right along with us wherever we are," Nan remarked. "I, for one, have no idea of having you rush off to Lausanne or some such place and leave us to our own devices here in Paris, and that is what it will amount to if you don't take care of yourself."

"Hear the child," exclaimed Mrs. Corner. "You would think she was the mother and I the daughter. I dare say you are right, Nan, and I meekly accept the situation, in spite of your superior manner."

"Nan's had so much responsibility with the younger children," put in Miss Helen, "that it comes quite natural to her to bring any one to task."

"Was I superior?" asked Nan, going over to her mother and caressing her. "I didn't mean to be. You are so precious, you see, that I have to think about what you ought and what you oughtn't to do."

"I quite understand, dear child, though it does make me feel ashamed of myself to have to give up my duties."

"Your duty is to coddle yourself all that is necessary," Miss Helen told her, "and this matter of changing our pension is to be left to Nan and me."

"Bravo!" cried Nan. "When you use that authoritative manner, Aunt Helen, we all of us have to give in, don't we, mother?"

"I know I do," laughed Mrs. Corner.

"How should you like to take a furnished apartment?" asked Miss Helen after a moment's thought. "I shouldn't be at all surprised but that my friend, Miss Selby, could tell us of one. You could have a maid who would relieve you of all care, and Paris is full of French teachers, so the children could go on with their lessons. We have not much more shopping to do, so you could sit back and rest."

"I believe I should like that plan," answered Mrs. Corner. "It has been so long since we had anything like a home that it would be a very pleasant change."

"I think it would be perfectly lovely," declared Nan. "I've always longed for an apartment in Paris, since I heard Miss Dolores tell about the way her cousins used to live here. By the way, we ought to be hearing from Mr. St. Nick. And what about England, Aunt Helen?"

"We'll get this other matter settled first, and then we'll see what is to be done next. Your mother declares she wants no more of England after her last rainy, chilly experience there, and I am not sure it would be best for her to venture. She is tired, and I think a rest is desirable for her." Mrs. Corner had left the room to speak again to Madame Lemercier.

"Shall we go at once to see Miss Selby?" asked Nan. "She has such a dear little studio, and has been in Paris so long that I am sure she can help us out, Aunt Helen."

"We may as well start at once," agreed Miss Helen. "Go get on your things, and I will be ready in a few minutes."

"I was thinking," said Nan when she returned, a little later, "that Miss Joyce might like to come and help to overlook the children, when we older ones are not on hand. She will be adrift after Madame goes, and she is not well off, you know. She speaks French like a native, and she might relieve mother of some[49] care. She is fond of the kiddies and if we should happen to take that trip to England, we would feel more comfortable about leaving mother here."

"That isn't a bad idea," returned Miss Helen, "and we may be able to follow it up if the apartment becomes a fixed fact."

The two started off, and were gone all morning, not even appearing at the midday meal. Early in the afternoon they came back looking rather tired, but triumphant. "We've found it," cried Nan; "the dearest place."

"What have you found?" asked Mary Lee, who, with Jo and Mrs. Corner, was in the sitting-room.

"Haven't you told her, mother?" said Nan. "Good! then I'll have all the fun of breaking the news. We're going from here. Madame Lemercier's going. We are all going."

"Are you trying to conjugate is going?" asked Mary Lee.

"No. Wait a minute and I'll tell you. Madame Lemercier has to close this house because her sister is ill in Switzerland. Result, the Corners are thrown out upon the wide wide world. Aunt Helen and I have been to see Miss Selby—you know Miss Selby, Mary Lee, the one who has that pretty studio, and is so entertaining—well, my child, listen; she knew[50] of exactly what we want in the apartment-house where she is. Another artist has an apartment there, a big one, and he is very eager to rent it because he wants to go to Brittany. We looked at it and it will be all right, I think, though it has one bedroom short. However, we can eat in the living-room, and put up a cot in the dining-room for me or somebody. There is a femme de menage who goes with the apartment, and we can rent everything, even the table linen, the Huttons say. It's awfully cheap, too."

"Where is it?" asked Mrs. Corner.

"Over in the Luxembourg quarter, mother mine, convenient to everything. Do let's go."

"It sounds all right," said Mrs. Corner. "What did you think of it, Helen?"

"It seemed just the thing to me, and we were most lucky to find it, I think. The Huttons go out on Monday, and we can move right in, bag and baggage, as soon after as we choose. Of course it is very artistic with sketches and studies on the walls, but it looked comfortable, and Mrs. Hutton seems to be a good housekeeper."

"It would be better if we could remain this side the river," said Mrs. Corner doubtfully. "I am afraid it will be rather hot over there."

"It is quite near the Luxembourg Gardens,[51] and I noticed the rooms appeared airy and well ventilated. We are hardly likely to have warmer weather than that of the past week."

"True. July is the hottest month. I'll go to-morrow and look at the place, if you can go with me, Helen. We may as well settle it at once if it is satisfactory."

"I shall be delighted to go with you, my dear," returned Miss Helen.

Jo, listening, looked rather subdued and thoughtful.

"Won't it be fun?" said Nan in an aside.

"For you, yes."

"And why not for Miss Josephine Keyes, pray?"

"I shall have to rejoin Miss Barnes and her girls. You know it was just because we rearranged the schedule so I'd have the chance to stay longer and give more time to French and German, that I was allowed to slip out of the party while they were doing Holland and Belgium."

"But it will be some time before they come to snatch you, and you surely will not desert us."

Jo brightened visibly. "Oh, would you really take me in, too? I thought maybe I would have to do something else; go into a school or something. I'm here for study, you see."

"You don't mean to say that you thought[52] we would leave a single lamb to the ravening wolves of Paris?" said Nan. "I thought better of you, Jo."

"But I would be perfectly safe in a convent or somewhere."

"Naturellement, but you don't go there unless you have a distinct yearning to do it. You are in mother's charge and she means to keep you under her eye."

"Then I must be the one to sleep in the dining-room."

"I've staked out that claim myself. You are to room with Mary Lee; we have settled it all."

The visit to the apartment was made by Mrs. Corner the next day, and resulted as Nan hoped it would, so the following Monday saw them move in with their belongings. Miss Joyce, upon being interviewed, was delighted to accept the proposition made her, but as there was not room in the apartment for her, Miss Selby, across the hall, offered her spare room for the time being, and so Miss Joyce became one of them, going on with her own studies and assisting the others in theirs.

"It is the greatest help in the world to me," she confided to the always sympathetic Miss Helen, "for I have to pinch and screw to make both ends meet. Madame Lemercier let me have my little room with her in consideration of[53] my helping her with beginners, and with the prospect of being deprived of that source of supply, I was feeling rather blue, and pictured myself subsisting upon crusts in a garret. You dear people are so intuitive and have come to my rescue in such a sweet way, as if the favor were all on your side."

The femme de menage failed to appear at the appointed hour, not quite understanding when she was expected, and Nan, who delighted in rising to occasions, volunteered to go forth for supplies. "There is a fascinating market not far off," she said. "We passed it the other day when we were coming here. And as for crêmeres and boulângeries, and all those, there is no end to them. I'll interview Miss Selby and get her to tell me the best places to order regularly. Who'll go to market with me?"

"I will, I will," came the chorus.

"Jack spoke first," said Nan, "so come on, sinner. Don't tell me what to get, mother. If I forget anything I'll go again, or the maid can when she comes. I am just longing for some of the things we can't get at a pension table. I am going to carry a net, just as the working people do. I don't care a snap who sees; it is only for once, anyhow. There is a nice smiling concierge lady down-stairs, very different from that vinegar jug at Madame Lemercier's. You[54] might give a list of groceries, mother. I am not so well up on those, and I can order them from Potin's."

She and Jack started out gleefully, returning with their supplies after some time. Then the three older girls set to work to cook the second breakfast on the gas-range. The kitchen was a tiny one and the three quite filled it, but they managed very well and their efforts were received with great applause.

"Of all things," cried Mrs. Corner; "fried eggplant; my favorite dish."

"And sliced tomatoes with mayonnaise," said Miss Helen. "How delicious."

"Strawberries and cream! Strawberries and cream!" sang out Jean delightedly.

"And actually liver and bacon, a real home dish," said Miss Joyce. "Nan, you are a jewel."

"It's the best little market," said Nan. "There is everything under the shining sun to be found there. I never saw so many kinds of fruits and vegetables, and they are really very cheap. Some of the things, the eggplants, for instance, look different from ours; they are a different shape and much smaller, but I saw most of the vegetables we are used to having at home, except green corn and sweet potatoes. As for the fruits, there are not only the home varieties but others, such as figs and some other queer things[55] I don't know the name of. I bought the most delicious sort of canteloupe for to-morrow's breakfast, but it was more expensive than those we have at home."

"I almost wish we were to have no maid," said Mrs. Corner.

Nan laughed. "If you could see the array of pots and pans there are to wash you wouldn't wish. I hope Marie or Hortense or whatever her name may be, will soon appear, for I am tired." She fanned her hot face with a newspaper.

"You poor child; you have worked too hard," said her mother sympathetically. "We will have the concierge lady, as you call her, come in and do the dishes. That is one of the advantages of being here; there is never any trouble in getting a person in to do whatever you may wish to have done. This is delicious bread, Nan, better than we had at Passy."

"Miss Selby told me where to get it. They call these lovely yard long two-inch-diametered sticks, baguettes. Aren't they nice and crusty?"

Mrs. Corner ate her meal with more relish than she had shown for some time and Nan was satisfied that the move was a good one.

The maid did not appear till the next morning, so the whole party dined at a queer little restaurant near by, staying to listen to the music[56] and to watch the people come and go. Nan prepared the morning coffee which was pronounced the best since the home days, and as the baker had not failed to leave an adequate number of baguettes, and the milk and cream were promptly served, there was no need to go forth for the early meal.

Jack sighed over leaving her friend, the cocher, and the two little playmates, Clemence and Pauline, but she soon became interested in a beautiful cat, called Mousse, which lived in the drug store below, and who played a number of clever tricks, these being displayed by his master with great pride. Jack discovered, too, that the concierge had a parrot, so the child found her entertainment here as easily as she had done elsewhere. Jean was satisfied with dolls and books in any place, and moreover, being very fond of good things, thought the change from Madame Lemercier's rather frugal table one to be approved. Mary Lee and Jo found plenty to do in watching the life which went on in the streets, while Nan liked to go further afield to the market which she declared was as amusing as a farce. "I wish you could see the bartering for a piece of meat," she told the family. "There is one butcher I could watch all day. I never saw such expressive contortions, such gesturings, such rollings of eyes and puffings[57] out of cheeks, and then to see a scrap of a Frenchwoman wriggle her fingers contemptuously under his very nose, while he looks fierce enough to bite them off, is as funny a performance as I ever beheld. Then after they have squabbled, and shrieked and abused each other long enough they end up with such smiles and polite airs as you never saw. You should hear Hortense answer the market people. She always has just the smartest and sauciest things to say, and how they do enjoy that sort of thing. Besides the market itself is really a sight to see. Even a stall with nothing but artichokes on it will be made attractive by a fringe of ferns, and as to the hand-carts piled with flowers, they ought to be a joy to any artist. I counted twenty different varieties of vegetables to-day, and as many kinds of fruit. We can scarcely do better than that in America at the same time of year. Oh, no, I wouldn't miss going to market for anything. I feel so important with Hortense walking respectfully behind me, ready with advice and polite attentions."

Tall, slight, dark-haired Nan was nearly sixteen. "My girl is growing up," sighed her mother. "She has the nest-building instinct, Helen. We shall not have her as a little girl much longer."

"She has still some years left," returned Miss Helen. "She has many childish ways at times, in spite of her being the eldest, and of having had more responsibility than the others. When she enters college it will be time enough to think that womanhood is not far off."

Nan, Mary Lee and Jo had just set to work at their French history. Nan was discoursing fluently, flourishing her book as she talked. "And here in these very streets it went on," she said. "Can you realize, girls? Fancy the Louvre seeing so many wonderful historical events. It was from there that the order went forth for the massacre of the Huguenots on that dreadful night of St. Bartholomew, and——"

"I don't want to fancy," Jo interrupted. "It is bad enough if you don't try to. It's too grewsome, Nan, to talk about."

"But it impresses it on one so vividly to talk about it, and we shall remember it so much better; besides I like to imagine."

"I don't see the good of it when it is all over and gone," said Mary Lee. "There is no use shedding tears over people who have been dead and in their graves a hundred years. That is just like you, Nan, to get all worked up over things that are past and forgotten."

"They never will be forgotten," maintained Nan, "unless you forget them, which you are[59] very liable to do, if you take no more interest. Well, then, if you must be slicked up and smoothed down by something sweet and agreeable, pick it out for yourself; I am going to study to learn and not because I want to feel comfortable."

"There's the facteur," interrupted Jo. "Let's see who has letters." She rushed to the door to be the first to receive the postman's sheaf of mail. "One for you, Nan," she sang out; "another for Mrs. Corner; one for me,—that's good,—and actually one for Jack. Two for you, Nan, for here's another."

Nan had already torn open the envelope of her first letter and was eagerly scanning the contents. "Just wait a minute," she said. "This is exciting. Please put the other letter somewhere, Jo, till I get through with this. Oh, I do wonder——"

"What is it, Nan?" asked Mary Lee, seeing Nan's excitement.

"Wait one minute. It's——"

"You're so exasperating," said Mary Lee. "You just jerk out a word and then stop without giving a body an inkling of what you mean."

"I'll tell you in one minute. I must finish reading."

Seeing there was no getting at facts till Nan[60] had come to the end of her letter, Mary Lee gave up in despair and went off to deliver the other mail. But before she returned Nan had rushed wildly to her mother, and Mary Lee found the two in lively conversation. "Oh, but can't we?" she heard as she opened the door of her mother's room.

"Can't we? What we?" she asked.

"You and I, anyhow," returned Nan. "It is a letter from Mr. St. Nick. He and Miss Dolores are at San Sebastian. Tell her, mother. Oh, do say we can go."

"There, Nan, dear, don't be so impatient," returned Mrs. Corner. "Just wait till we can talk it over. It cannot be decided all in one minute, besides, I have not had time to read my own letter yet. I see it is from Mr. Pinckney, and I have no doubt but that it is upon the same subject."

"I wish you would tell me what it is all about," said Mary Lee despairingly.

Nan thrust her letter into her sister's hand. "There," she said, "read it for yourself."

This Mary Lee proceeded to do while Nan hovered near, trying to gather from her mother's expression what she thought of the proposition which Mr. Pinckney had made.

"It is out of the question for us all to go," said Mrs. Corner as she laid down her letter.[61] "We have taken this apartment and have made all our arrangements, and to allow even you and Mary Lee to take that long journey alone is something I could not think of."

"Oh, mother!" Nan's voice expressed bitter disappointment.

"If there is any one country above another that I do want to see, it is Spain," said Mary Lee sighing as she handed back the letter she had been reading.

"I am sorry, but I don't see how it can be managed," returned Mrs. Corner. "However, I will talk to your Aunt Helen about it and——"

"If there can be a way managed you'll let us go, won't you?" Nan put in impatiently. "If we should happen to find any one going that way who would chaperon us it would be all right, wouldn't it? Mr. St. Nick said he would meet us anywhere the other side of Bordeaux. He suggested Biarritz and there must be thousands of people going there."

"There may be thousands, and doubtless are, but if we don't know any one of them it would not do any good."

"We surely must know one," replied Nan still hopeful.

"Let's go and watch for Aunt Helen," said Mary Lee, as eager as Nan for once. She adored Miss Dolores and had looked forward to[62] meeting her with her grandfather, so now to have the opportunity thrown at them, as Nan said, and not to be able to take advantage of it seemed a cruel thing. They went back to the living-room to pour out their enthusiasm to Jo, who looked a little wistful though she was greatly interested.

"I should miss you awfully," she said, "though Miss Barnes and the other girls will be coming along soon, and I should have to go anyhow, I suppose."

"It won't be so very long even if we do go," Nan assured her; "not more than a month."

"Oh, I shall keep busy improving each shining hour," said Jo cheerfully, "and it will be so good to have you back again."

"That's one way of looking at it," laughed Nan. "Oh, I do hope we can go."

"Go where?" asked Jack who had just come in.

"To Spain," Nan told her. "Mr. St. Nick has written to say that he will not take no for an answer. He wanted the whole Corner family to come, but mother says it is out of the question, so it has dwindled down to Mary Lee and I, if any one goes at all. Who's your letter from?"

"Carter."

"Carter? Well, he is nice not to forget us. What does he say?"

"Read it." Jack handed over her letter which Nan must have found not only interesting but amusing, as she laughed many times before she had finished reading. "Cart is a nice boy," she said as she folded up the sheet. "I shall be glad to see him again."

"It will be many a long day before you do," remarked Mary Lee.

"Not so long as you think, maybe," returned Nan. "He may come abroad in the spring, and says perhaps we can meet in Italy if we are there then."

"We're pretty sure to be, for we shall not leave Munich before March, Aunt Helen says."

"There's Aunt Helen now," exclaimed Jack who was watching from the window. And the appearance of Miss Corner put an end to all thoughts of Carter Barnwell for the time being.

Nan projected herself so suddenly upon the little figure that it staggered under the onslaught. "Oh, Aunt Helen," she cried, "blessed and always helpful godmother, the fairest of fairy godmothers, we do so want to go to Spain and you must use your fairy wand to create a chaperon for us. Make her out of anything, old rags, toads, anything, anything, so we get her. Please do."

"What are you talking about, you catapult. You have nearly knocked the breath out of[64] me, you great big Newfoundland dog trying to be a terrier pup. You forget I am not your superior in size if I am in years. Let me get off my hat and give me breathing space, then tell me what the excitement is."

Nan released her aunt and allowed her to collect her senses before she told her tale which was listened to attentively. "I'd love to have you go," said Miss Helen.

"Of course you would. You are always that sort of dear thing."

"But just at present I don't see how it is to be managed. However, I will put on my thinking-cap and perhaps the next twenty-four hours will bring me an idea."

"When Aunt Helen puts on her thinking-cap a thing is as good as done," declared Nan to Mary Lee, and both felt quite sure that the journey to Spain would be undertaken.

Sure enough the faith Nan had in her aunt was not without foundation, for that very evening Miss Helen learned from her friend, Miss Selby, that the next week an acquaintance was going as far as Poitiers, and that there would probably be no difficulty in arranging to have her act as chaperon to Nan and Mary Lee as far as that city.

"And really," Miss Selby assured Miss Corner, "it will be perfectly safe to allow them to go on alone as far as Biarritz, for it is not a long journey, and their friend will meet them. They can both speak French fluently enough to get along perfectly, and I have several safe addresses which I can give them in case their train should be delayed, or in case their friend fails to arrive on time. I have an acquaintance at Bordeaux and another at Biarritz, so in case of delay all they will have to do will be to take a cab to either address. I will give them notes of introduction so they will have no trouble whatever."

Miss Helen was enough of a traveler herself to feel that this would be sufficient precaution,[68] but Mrs. Corner demurred, and at first could not be persuaded to give her consent to the girls traveling any of the distance alone, but at last she yielded and wrote to Mr. Pinckney that he might expect her two elder daughters to arrive at Biarritz on a certain day, and the two set off in high spirits.

"It's such fun to go bobbing along the streets of Paris in a cab," said Nan, "to take your luggage along with you and not to have to bother about street-cars or anything. I wish we had such nice cheap cab service at home, don't you, Aunt Helen?"

"That is one of the advantages upon which I am afraid I do set a higher value than my friends at home would have me. There are several things on this side the water which I claim are advances upon our system at home, and because I say so my friends often think I am unpatriotic. But never mind. There is the Gare d'Orsay where we are to find Miss Cameron. Look out for your pocketbook, Nan, and be sure not to lose your ticket."

Miss Cameron was found promptly and in a few minutes the girls were established in their train. They were glad to be able to whisper together for Miss Cameron had a friend who was going as far as Orleans, and who shared the compartment with them, therefore, Mary Lee[69] and Nan were not called upon to take part in the conversation.

It was still light when they reached the pretty town of Poitiers which, set upon a hill, looked picturesque and interesting as the travelers left the train and were borne up a steep incline to their hotel.

"It is a perfectly dear place," decided Nan enthusiastically. "We must get some post-cards, Mary Lee, and send them off to mother and the rest of the family."

"We mustn't forget poor old Jo," said Mary Lee. "I know she is missing us this blessed minute."

"Who is Jo?" asked Miss Cameron.

"One of our school friends who came over with us. She won the prize of a trip to Europe and has been with us right along." Nan gave the information. "Tell us something about Poitiers, Miss Cameron."

There was nothing Miss Cameron would like better to do. She was a teacher who was spending her vacation abroad and was enjoying it hugely. She was neither young nor beautiful, but had a way with her, Nan confided to Mary Lee, and both girls liked her. "I should like to go to her school," Nan said to her sister.

"So should I," Mary Lee whispered in return.[70] So they asked many things about the school which was in Washington, and by the time they had learned all they wanted to know, the top of the hill was reached and they turned into a winding street which led to the quiet hotel where they were to stay over night.

"When we have had dinner," said Miss Cameron, "we can go to the Parc de Blossac where we shall see the people and hear the band. I'd like you to see something of the town before we leave to-morrow. There are two or three nice old churches and the little baptistry of St. Jean is said to be the oldest Christian edifice still existing in France."

"I am sure I shall like to see that," declared Nan, who loved things old and romantic. "I like the looks of this place, anyhow," she went on. "It is perched so high and has an interesting air as if it had looked out of its windows and had seen things. Then the people are nice, wholesome appearing men and women, quite different from those you see in Paris. Their faces are more earnest and good, somehow."

Miss Cameron looked pleased. "You are quite a critical observer, Nan," she said. "I quite agree with you, for I haven't a doubt but that your impressions are correct. But here we are. We will not make toilettes, but will only brush off the dust and have our dinners."

The dining-room was airy and pleasant, and the dinner good; after it was over there was still daylight enough for them to find the way easily to the Parc de Blossac. They discovered this to be a pretty, restful spot, as they hoped it would be, and the hour they spent there added to their pleasant impression of the little city.

They were up betimes the next morning for they wanted to make the most of the few hours they should have. To the consternation of all three it was ascertained that Miss Cameron, who was going in a different direction, would be obliged to take an earlier train than the girls would.

"I am so sorry," she said. "I was sure there would be a train south before so late in the day, but as my friends, who are to meet me, will have to drive some distance, I don't see very well how I can fail to keep my promise of arriving on time."

"We shall do very well," Nan assured her. "We will ask very particularly before we get on the train if it is the one for Biarritz, and there will not be a bit of trouble, I am sure. We have very little luggage, you know."

"And I am sure I can see that it gets on all right," said Mary Lee.

"I am so sorry," repeated Miss Cameron[72] looking quite worried. "It never seemed within the bounds of possibility that there should be no train before that hour. If my friends were near telegraph offices and such things I could wire them, but a French chateau near only to a small village is too unget-at-able for words."

The girls continued to protest that they would have no difficulty at all, and finally Miss Cameron yielded to their protests that she must leave them to take care of themselves, and at last waved them a farewell from her car window. "Be sure you send me a card that I may know you have arrived safely," were her last words, and they promised.

But it must be confessed that when they faced each other, two strangers far from home and mother, they felt a little sinking at heart.

"Do you think we need sit here in this station for a mortal hour and a half?" asked Mary Lee. "Couldn't we walk about a little?"

"I suppose so," Nan responded a little doubtfully, "but we must be sure to come back in time. We've seen the cathedral and the baptistry. We have seen the outside of St. Hilaire-le Grand, and the inside of St. Radegunde and Notre-Dame la-Grande. We have been to the Parc de Blossac and up and down a number of the streets. I wonder what else there is to see that we could do in an hour."

"It is an awful walk up that hill and it is warm."

"I should say it was in a noonday sun. We might go a little way very slowly. I have been longing to go up on that nice craggy place and look down. When we get back we will buy some post-cards and send them off; that will pass away the time."

They mounted the steep hill for a short distance, stood for a while looking up and looking down, then returned to the station and started toward the little stand where they had seen some post-cards. As Nan opened the small bag she carried, she gave an exclamation of dismay. "Mary Lee," she cried, "have you my pocketbook?"

"No," was the answer.

"It's gone." Nan looked hurriedly through her larger bag which held their toilet articles, Mary Lee watching her anxiously. "It's gone," she repeated, "clean gone, and there is no time to go back and look for it."

"Do you think you could have left it at the hotel?" Mary Lee asked. "We could write and get them to send it if it is found."

"No, I am sure it is not there. I had it when we stopped to buy the chocolate. I paid for that, you know. After we left that shop I remember that the catch of my little wrist bag[74] came unfastened; it caught in something. I shut it up without looking, but the pocketbook must have fallen out then, for it was right on top. Of course some one picked it up and there is no use hunting for it; we haven't time. Thank fortune! the tickets are safe, and the bulletin, or whatever they call it, for the baggage."

"Had you much money in it?"

"About twenty-five francs and some loose change. Mother said I'd better not carry more. I have a check which I am to get Mr. Pinckney to have cashed for us, and if we need more it is to be sent, though mother thought the amount of the check would be ample. How much have you, Mary Lee?"

Mary Lee opened her purse and counted. "About ten francs and a few centimes."

"That ought to take us through, if we don't have any delays or accidents," said Nan, though she looked a little worried. "Fortunately we have paid our hotel bill here, and we have those notes of introduction that Miss Selby gave us. I have no doubt but that at one of those places they would cash our check even if Mr. Pinckney should fail to meet us, so it isn't quite as bad as it might be." She spoke reassuringly, though she was in some doubt about the matter. "I am glad we have that chocolate," she went on.[75] "We won't get the post-cards, for we have already sent one to mother from the hotel. When we get to Bordeaux, instead of having a hearty meal, we can get some rolls or something and save the money in case of an emergency."

Mary Lee said nothing, though she felt that Nan had been careless. It was very like her not to look in her bag to see if all were safe after it became unfastened. She was always so absorbed in what was going on around her, and had not the exact and precise ways of her younger sister. Mary Lee would never have budged till she was certain that every article she carried was in place. Nan was grateful for her sister's silence, for Mary Lee was not given to holding her tongue on such occasions.

"I think that must be our train," remarked the latter. "I am sure one is coming." She looked sharply to see that the umbrellas and bags were not left, and followed the trunks till she saw them safely on the train, then she climbed into place by Nan's side, breathing a sigh of relief.

The two girls were silent for some time after the train began to move. They felt rather depressed. All sorts of possibilities loomed up before them. Presently Nan said, "I wonder if we have to change cars. I saw that this train was[76] marked Bordeaux, but I didn't see any Biarritz on it."

"We'd better ask at the next stop. You do it, Nan; you are so much more glib with your French than I am."

Nan made her inquiry in due course of time and found that the change must be made. "But it is in the same station," she told Mary Lee, "and our baggage is booked through, so there will be no trouble, the guard says."

"I hope it won't be dark when we get to Biarritz," said Mary Lee after a while.

"I am afraid it will be, but I am sure Mr. St. Nick will be on hand. You know Miss Cameron telegraphed to him as soon as we knew what train we should take. I had no idea that the train would take so many hours, though, and neither did she. However, he will be there all right."

But in spite of her show of confidence, the elder girl did have her misgivings, and the two were rather quiet as the daylight faded. They ate their chocolate and rolls pensively, feeling rather ashamed at having so frugal a meal till they saw two of their fellow passengers, well-dressed personages, cheerfully supping upon like fare which they, too, had providently carried with them.

"I don't believe it makes a bit of difference[77] about doing such things in France, at least," Nan whispered. "You know the French are very frugal, and even well-to-do people practice economies we would never think of."

It was dark indeed when they left their train at Biarritz and Mary Lee kept very close to her tall sister as they stood waiting on the platform. "Suppose he isn't here," she said tremulously.

"Then we will take a cab to that address Miss Selby gave us," said Nan bravely, though feeling a sinking of heart as she thought of doing even that.

But at that moment a portly form approached and a hearty voice called out, "There you are, you poor little chicks. I am glad to see you."

"You aren't half as glad to see us as we are to see you," returned Mary Lee fervently.

"Your train was an hour late," Mr. Pinckney told them; "but what can you expect in this country?" he added.

"Oh, they are never late in ours, are they?" laughed Nan. "It is good to see you, Mr. St. Nick. When I beheld your dear big round self coming toward us I could have shouted with joy, for we were feeling a little bit scared."

"Tut, tut, how was that? You don't mean to say you came from Paris alone?"

"Oh, no, mother would never have allowed that, and she would never have allowed us to[78] venture anyhow, if she had known how things really did turn out." She gave him an account of their journey ending with the tale of her lost pocketbook. "And so, you see," she said, "we were a little bit afraid we might not have enough to get through on, and we hated to go to a strange pension and not have enough money to pay our way."

"Too bad, too bad," said Mr. Pinckney. "I ought to have come all the way to get you."

"But that wasn't necessary," Nan told him, "and it is all over now. It was only a scare and not a real danger, you see, for we had a most quiet and uneventful journey from Poitiers. An infant in arms could have taken it with perfect propriety."

"Especially if it had been in arms," put in Mary Lee.

"That sounds just like Miss Propriety, Prunes and Prisms," said Mr. Pinckney. "Well, my dears, your rooms are all ready, and you have nothing more to bother about from this time on."

"And is Miss Dolores with you?" asked Mary Lee.

"Left her at San Sebastian. It is nothing of a run there, you know. You will see her to-morrow."

After this there was no more trouble, and the girls gave themselves up to listening to the[79] plans made for their pleasure. They were too tired to lie awake long, but they awoke in the morning full of enthusiasm, ready to enjoy the dainty breakfast prepared for them and served in loveliest of gardens. Mr. Pinckney would not hurry them away before they had seen the beautiful coast of the famous watering-place, and insisted upon their having a little drive around before their train should leave.

"And this is where the young King of Spain used to come to see the queen when she was Princess Ena," Nan told Mary Lee.

"I wish they were here now," returned Mary Lee.

"You may have a chance to see them before you leave Spain," Mr. Pinckney told her, "for they travel about a good deal."

"Before we leave Spain! Doesn't that sound fascinating?" cried Mary Lee.

"What! You think it will be fascinating to leave us?" said Mr. Pinckney in pretended surprise.

"Oh, dear, it did sound so. No, indeed. I never want to be long away from you and dear Miss Dolores, Mr. St. Nick," Mary Lee hastened to say.

"That sounds more like it," he answered.

"Are we going to stay right in San Sebastian?" asked Nan.