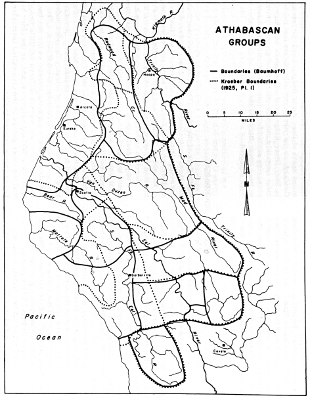

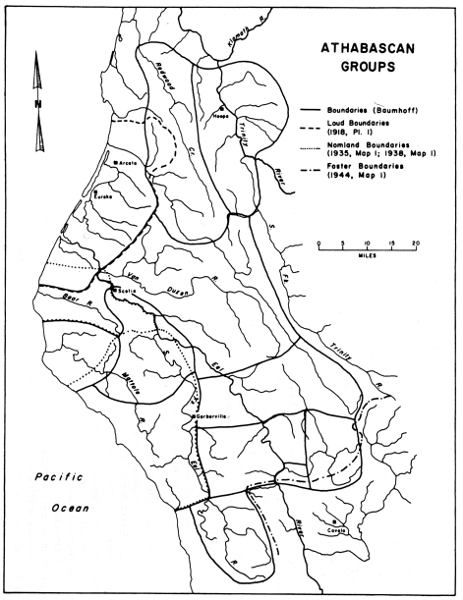

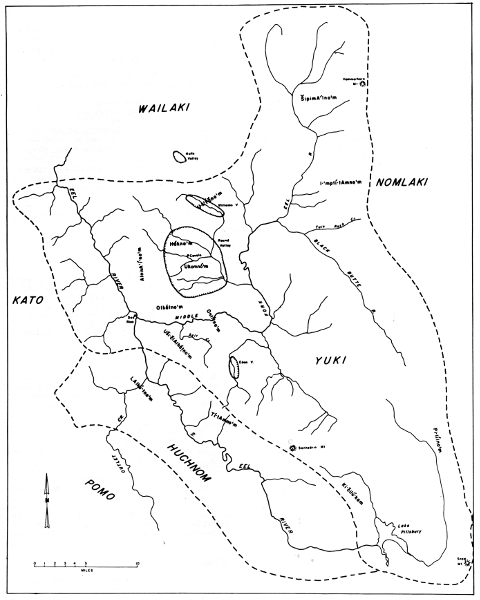

Map 1. Athabascan boundaries: Kroeber vs. Baumhoff.

Project Gutenberg's California Athabascan Groups, by Martin A. Baumhoff This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: California Athabascan Groups Author: Martin A. Baumhoff Release Date: October 3, 2013 [EBook #43876] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CALIFORNIA ATHABASCAN GROUPS *** Produced by Colin Bell, Richard Tonsing, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

MARTIN A. BAUMHOFF

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS

Vol. 16, No. 5

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS

Editors (Berkeley): J. H. Rowe, R. F. Heizer, R. F. Murphy, E. Norbeck Volume 16, No. 5, pp. 157-238, plates 9-11, 2 figures in text, 18 maps

Submitted by editors May 6, 1957 Issued August 1, 1958 Price, $1.50

University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles California

Cambridge University Press London, England

Manufactured in the United States of America

In March, 1950, the University of California assumed custodianship of an extensive collection of original and secondary data referring to California Indian ethnology, made by Dr. C. Hart Merriam and originally deposited with the Smithsonian Institution. Since that time the Merriam collection has been consulted by qualified persons interested in linguistics, ethnogeography, and other specialized subjects. Some of the data have been published, the most substantial publication being a book, Studies of California Indians (1955), which comprises essays and original records written or collected by Dr. Merriam.

The selection and editing of the material for the Studies volume made us aware of the extent of the detailed information on ethnogeography which a thorough survey of the Merriam data would provide. We therefore approached Dr. Leonard Carmichael, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, with the proposal that a qualified graduate student be appointed as research assistant to study and prepare for publication a discrete amount of Merriam record material, remuneration for this work to be paid from the E. H. Harriman fund, administered by the Smithsonian Institution for preparation and publication of Dr. Merriam's ethnological data. This proposal was approved, and Mr. Martin Baumhoff began his one year of investigation on September 15, 1955.

After discussion, we agreed that the area where tribal distributions, village locations, and aboriginal population numbers were least certainly known—and also a field where the Merriam data were fairly abundant—was the territory of the several Athabascan tribes of Northwestern California. Under our direction, Baumhoff patiently assembled all the available material on these tribes, producing what is certainly the most definitive study yet made of their distribution and numbers.

In this monograph the importance of the Merriam data is central, although they are compounded with information collected by other students of the California Athabascans. We believe that the maps showing group distribution represent the closest possible approximation to the aboriginal situation that can now be arrived at.

The Department of Anthropology hopes to be able to continue the work of studying and publishing the Merriam data on tribal distributions. It takes this opportunity to express its appreciation of the co÷peration of the Smithsonian Institution in this undertaking.

A. L. Kroeber

R. F. Heizer

| Page | |

| Preface | iii |

| Introduction | 157 |

| Athabascan culture | 158 |

| Athabascan boundaries | 160 |

| Exterior boundaries | 160 |

| Interior boundaries | 161 |

| Groups | 166 |

| Kato | 166 |

| Wailaki | 167 |

| Pitch Wailaki | 176 |

| Lassik | 178 |

| Nongatl | 181 |

| Sinkyone | 184 |

| Mattole | 195 |

| Bear River | 200 |

| Whilkut | 201 |

| Hupa | 209 |

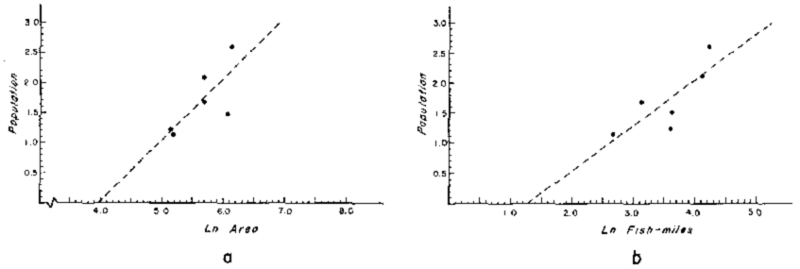

| Population | 216 |

| Sources | 216 |

| Estimates based on village counts | 216 |

| Estimates based on fish resources | 218 |

| Gross estimate | 220 |

| Appendixes | |

| I. The Tolowa: Data from Notes of C. Hart Merriam | 225 |

| II. Notes of Upper Eel River Indians, by A. L. Kroeber | 227 |

| Bibliography | 230 |

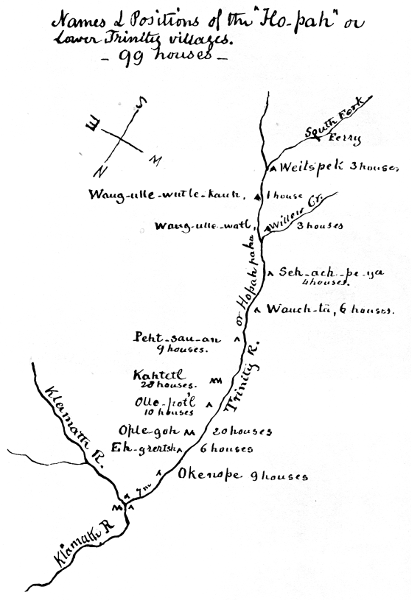

| Plates | 233 |

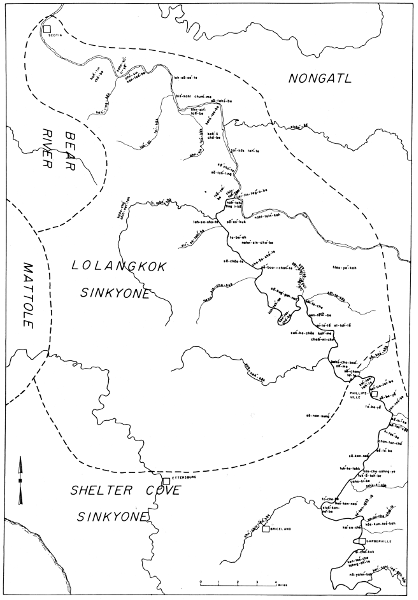

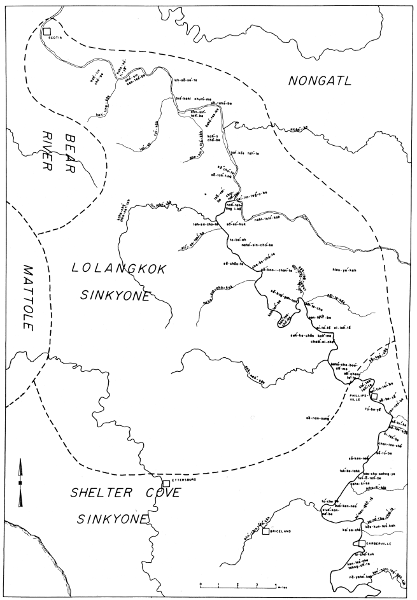

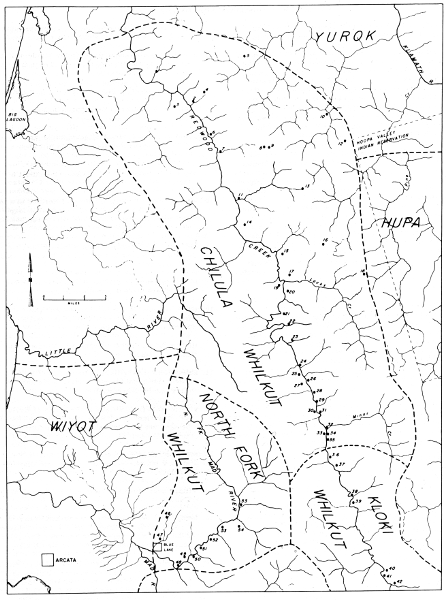

| 1. | Athabascan Boundaries--Kroeber vs. Baumhoff | 162 |

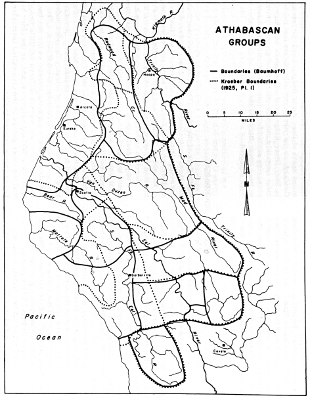

| 2. | Athabascan Boundaries--Baumhoff | 162 |

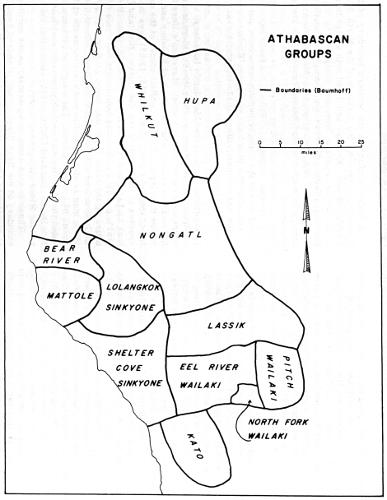

| 3. | Athabascan Boundaries--Merriam vs. Baumhoff | 163 |

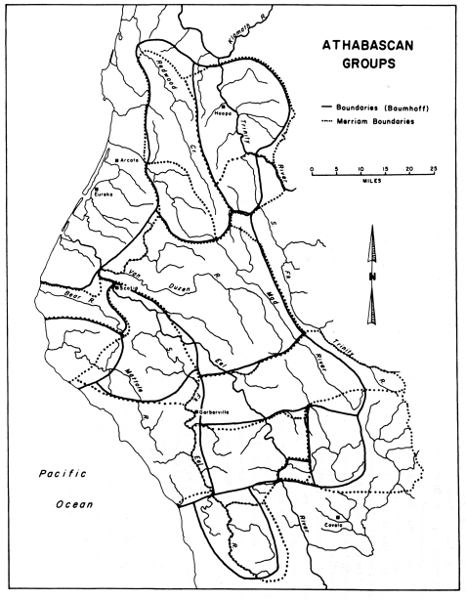

| 4. | Athabascan Boundaries--Various authors vs. Baumhoff | 163 |

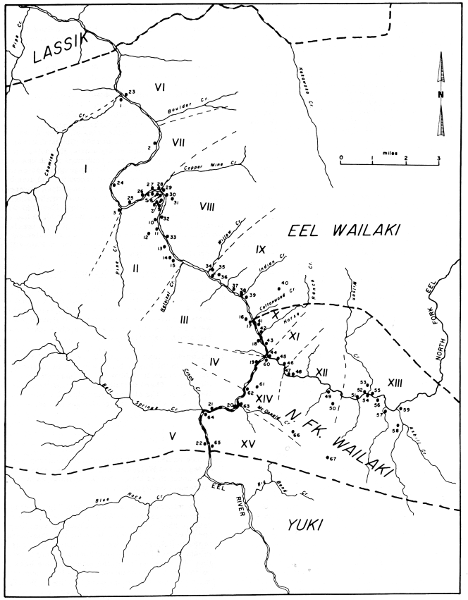

| 5. | Villages and Tribelets of the Eel Wailaki and the North Fork Wailaki | 168 |

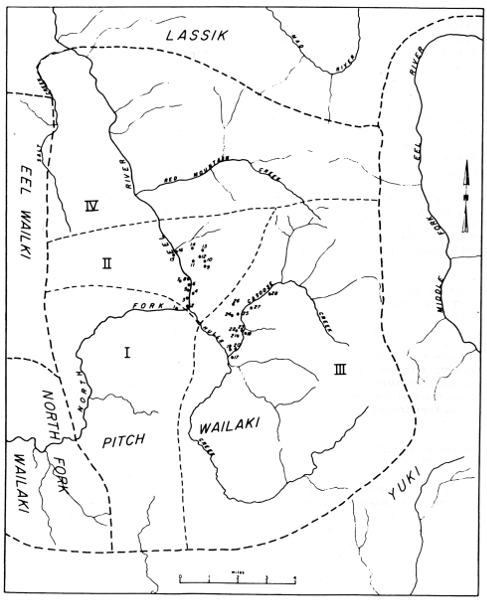

| 6. | Villages and Tribelets of the Pitch Wailaki | 177 |

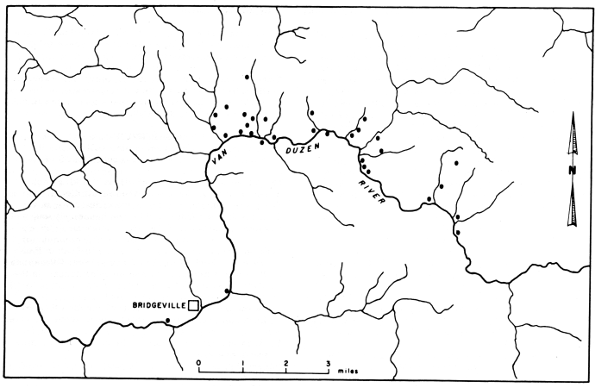

| 7. | Presumed Nongatl Villages in the Bridgeville Region | 180 |

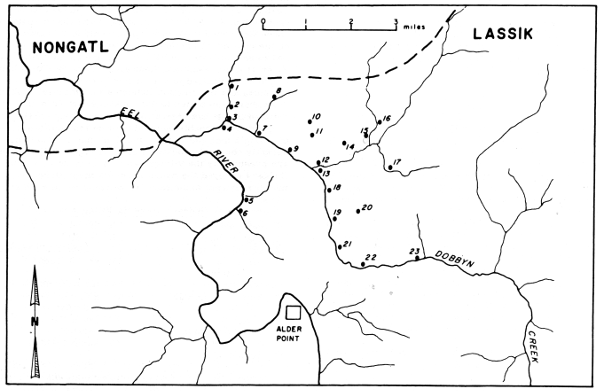

| 8. | Lassik Villages in the Alder Point Region | 180 |

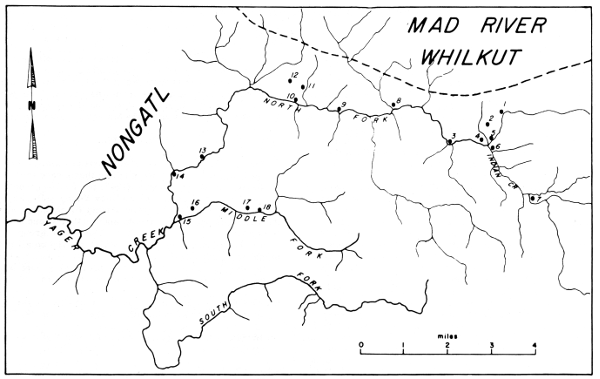

| 9. | Nongatl Villages on Yager Creek | 182 |

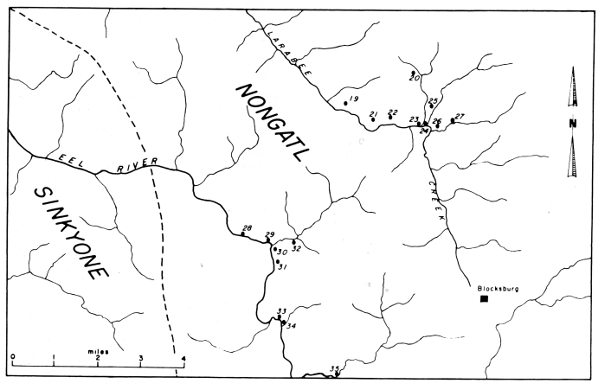

| 10. | Nongatl Villages in the Blocksburg Region | 182 |

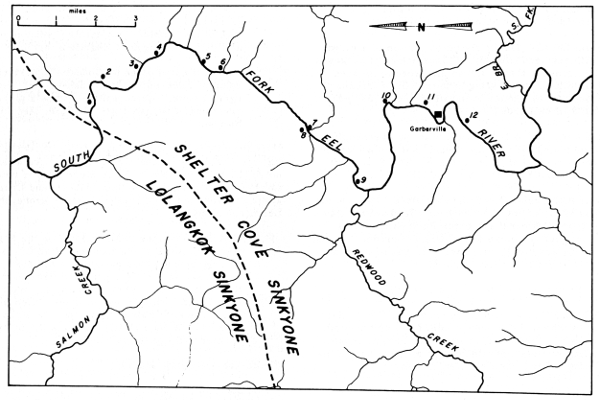

| 11. | Villages of the Lolangkok Sinkyone | 186 |

| 12. | Villages of the Shelter Cove Sinkyone | 190 |

| 13. | Place Names of the Lolangkok Sinkyone | 192 |

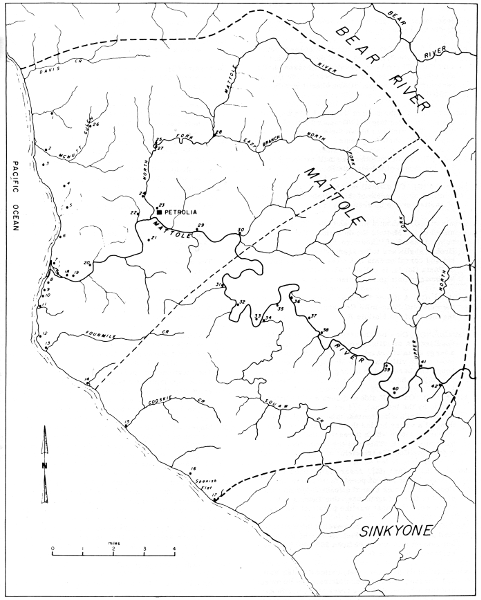

| 14. | Villages and Tribelets of the Mattole | 197 |

| 15. | Villages of the Chilula Whilkut, North Fork Whilkut, and Kloki Whilkut | 204 |

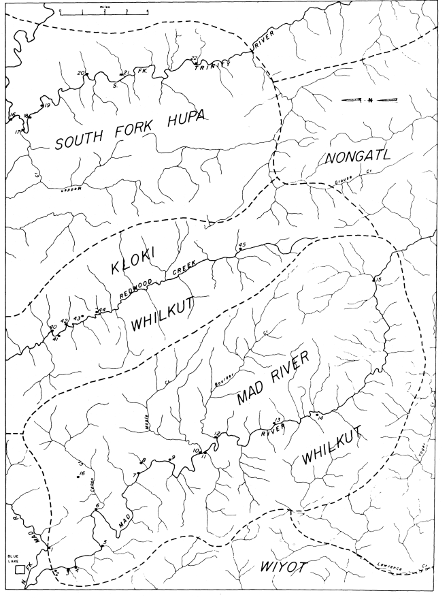

| 16. | Villages of the Mad River Whilkut, the South Fork Hupa, and Kloki Whilkut | 208 |

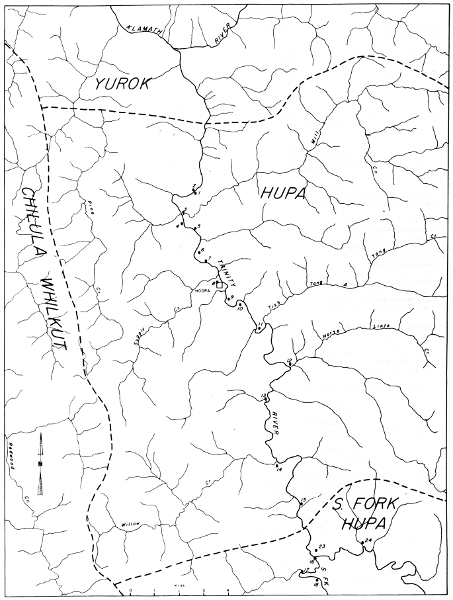

| 17. | Villages of the Hupa and South Fork Hupa | 211 |

| 18. | Yuki "Tribes," according to Eben Tillotson (App. II) | 228 |

CALIFORNIA ATHABASCAN GROUPS

BY

MARTIN A. BAUMHOFF

In 1910 C. Hart Merriam, already well known as a naturalist, came to California and began the study of California ethnography which was to occupy him for the rest of his life. Almost every year from then until his death in 1942 Merriam spent about six months in the field, talking to Indians and recording their memories of aboriginal times. All this field work resulted in an immense collection of data on the California Indians, most of which has never been published (see Merriam's bibliography in Merriam, 1955, pp. 227-229).

In 1950 the greater part of Merriam's field notes was deposited at the University of California, with the intention of making them available for study and publication. One volume of papers has already appeared (Merriam, 1955), and the present study is part of a continuing program.

The California Athabascans were selected as the first group for study at the suggestion of A. L. Kroeber, the reason being that the Athabascans have been and still remain one of the least known aboriginal groups in the State. This is not because they were conquered early and their culture dissipated, as is true of the Mission Indians; there were scarcely any whites in the California Athabascan area before the 1850's. Indeed, as late as the 1920's and '30's there were many good Athabascan informants still available. The reason for the hiatus in our knowledge lies in an accident in the history of ethnology rather than in the history of California.

The early work among the California Athabascans was done by Pliny Earle Goddard. Goddard began his studies of the Athabascans in 1897 at the Hoopa Indian Reservation, where he was a lay missionary. He stayed there until 1900, when he went to Berkeley to work for his doctorate in linguistics under Benjamin Ide Wheeler, President of the University of California. Between 1900 and 1909 Goddard was associated with the University as student and professor and during this time he visited the Athabascans periodically, until he had worked with virtually all the groups considered in this paper.

During this same period A. L. Kroeber was engaged in gathering material for his classic Handbook of California Indians. Because of the scarcity of ethnographers in those years Kroeber could not afford the time to work in the Athabascan area and duplicate Goddard's investigations. Kroeber did study the Hupa and the Kato at either end of the Athabascan area but, except for a hurried trip through the region in 1902, he did not work with the other groups, and the responsibility for the ethnographic field work therefore devolved upon Goddard.

Goddard, however, was not primarily an ethnographer but a linguist, and he directed his chief efforts toward linguistic investigations. He has published an impressive body of Athabascan texts and linguistic analyses but, except for his Life and Culture of the Hupa (1903a), almost nothing on the culture of the Athabascans.

The net result is that the California Athabascans are virtually unknown, and Merriam's fresh data provide an opportunity to piece together the available evidence.

The Merriam files, deposited at the Department of Anthropology of the University of California, contain information on each of the tribes of California, some of it being information gathered by Merriam himself, the rest clippings and quotations from various historic and ethnographic sources. The primary and secondary materials are easily distinguished, since Merriam gave scrupulous citations to his sources.

Merriam's own data consist of word lists, ethnogeographical material, and random notes on various aspects of native culture. I have not used his word lists, since their usefulness is primarily linguistic and I am not competent to perform the necessary linguistic analysis, but all the random ethnographic notes which he recorded for the Athabascan groups are here included under the discussion of the appropriate tribes.

Most of the Merriam Athabascan material is geographic, consisting of lists of villages and place names, of descriptions and lengthy discussions of tribal boundaries. Obviously Merriam attempted to gather a complete file of this sort of information, and he was largely successful. His work provides a good basis for establishing boundaries and for locating tribelets and villages.

Another important source of information, serving the same purpose, is the Goddard material. Evidently Goddard very much enjoyed the long horseback trips he made with an informant, who could point out the village sites, landmarks, and other points of interest of his native territory. This information, carefully recorded by Goddard, has proved extremely valuable in the present work, the more so since it represents firsthand observation.

Goddard's ethnogeographic work for three of the California Athabascan groups has already been published (1914a; 1923a; 1924). Besides this, the present writer has been fortunate enough to have access to Goddard's unpublished notes, which contain information on several hundred additional villages in the area. These notes were in the possession of Dr. Elsie Clews Parsons, Goddard's literary executor, and on her death they were sent to the University of California by Dr. Gladys Reichard. They remained in the files of the University of California Museum of Anthropology until their use in the present work.

This unpublished material of Goddard's consists of a group of file cards, on each of which is typed the name,[Pg 158] location, and any other pertinent data for a single village. Some of the lists are accompanied by maps, showing precise location of the villages. In the lists for which there are no maps but only verbal descriptions of the sites, the township, range, and quarter section co÷rdinates are given. The township and range co÷rdinates have been changed since Goddard's time, in accordance with the more accurate surveys of the last thirty years, but county maps of the appropriate period provide a perfectly adequate way of locating Goddard's sites within a few hundred yards.

It is clear, on the basis of internal evidence, that there is or was more Goddard material than is now accessible to the present author. For the Kato, for instance, Goddard says that he recorded more than fifty villages (Goddard, 1909, p. 67); all that remain in his notes are two village cards numbered 51 and 52 respectively. There may also be some data, once recorded but now lost, from the Lassik, Nongatl, and Shelter Cove Sinkyone. I have communicated with the American Museum of Natural History, where Goddard was a member of the staff, and with Indiana University, where some of his manuscripts are deposited, but neither of these institutions has any knowledge of the material in question.

The Merriam and Goddard material, taken together, provides a fair amount of information on the geography of the California Athabascan groups. We are now in the position of knowing a great deal about the location of the tribes, tribelets, and villages of these people, while we know very little about their way of life, except what can be gained by inference from the surrounding groups.

The author's thanks are due to Dr. A. L. Kroeber and Dr. R. F. Heizer, who gave their full co÷peration throughout the preparation of the present paper. Dr. Henry SheffÚ was kind enough to advise on the statistics used in the section on population.

The following sketch of Athabascan culture attempts to provide some background for the later discussion of the various groups. In this sketch I have not used the material from the Hupa, since they are virtually identical with the Yurok and not at all typical of the more southern Athabascans.

Subsistence.—For information on Athabascan economy I have relied heavily on Essene's account of the Lassik (1942, p. 84). There was, no doubt, variation among the different groups, but for the most part, they must have followed a similar pattern.

The most difficult time in the annual cycle of food production was winter. There were then few fish and almost no game animals or crops for gathering. From late November to early March people had to rely on food that had been stored the previous year. Essene's informant said that about every four or five years there would be a hard winter, but she could remember only one when people actually starved to death.

In February or March the spring salmon run began, and after that the danger of starvation was past. At about this time the grass began to grow again, and the first clover was eaten ravenously because of the dearth of greens during the winter.

The herb-gathering and salmon-fishing activity lasted until the spring rains ended in April or May, when the people left their villages on the salmon streams and scattered out into the hills for the summer. Usually only a few families would stay together during the summer, while the men hunted deer, squirrels, and other animals and the women gathered clover, seeds, roots, and nuts. Food was most plentiful at this season, and the places visited varied with the abundance of different crops. If a certain crop was good, the Indians would spend more time that summer in the area where the crop grew best. The next year they might go somewhere else. The vegetation of the Athabascan habitat is not well enough mapped to permit a precise delineation of these various summer camping grounds.

In September or October, when the acorns were ripe, the Indians would return to their winter villages and smoke meat for storing and probably store the acorns. Each family built a new house to protect it from the heavy winter rains. After the first rain in the fall the salmon run again in some of the streams of the region and were caught and smoked for winter storage.

It is evident that the crucial factor in the economy was the amount of food stored for winter and that this food supply was a controlling influence on the size of the population, since, in bad years, people starved. At least, this was so for the Lassik, and it was no doubt true among the other groups as well. Salmon, meat, and acorns were doubtless the chief foods stored, and thus population size would have responded quite sensitively to the quantity and condition of the salmon, deer, and oak trees.

Social organization.—For social organization I have had to rely mostly on Nomland's accounts of the Sinkyone and Bear River groups (1935, 1938). The primary social unit among the California Athabascans was the simple family, including a man, his wife, and his children. Although polygyny was known, at least among some groups, it was rare, and the possessor of two wives was reckoned a rich man. Most marriage was by purchase; the levirate and sororate were common. Divorce was also common and might be obtained by a man because of his wife's barrenness, laziness, or infidelity.

The next social group, larger than the family, was the tribelet. Kroeber (1932, p. 258) has defined the tribelet as follows.

Each of these [tribelets] seemed to possess a small territory usually definable in terms of drainage; a principal town or settlement, often with a chief recognized by the whole group; normally, minor settlements which might or might not be occupied permanently; and sometimes a specific name, but more often none other than the designation of the principal town. Each group acted as a homogeneous unit in matters of land ownership, trespass, war, major ceremonies, and the entertainment entailed by them.

This definition, given for the Pomo, fits the Athabascan area very well. Merriam usually refers to these groups as "bands," while Goddard calls them "subtribes." In the body of this paper I use the word "band" when quoting or paraphrasing Merriam, otherwise I call them "tribelets."

The tribelet was the largest corporate group in the area. A larger group, which I call the tribe, has been identified by most ethnographers. This latter group[Pg 159] ordinarily had no corporate functions, unless it happened to be coterminous with, and therefore indistinguishable from, the tribelet. The tribe, as the term is used here, was a group of two or more tribelets—or occasionally one single group—with a single speech dialect, different from that of their neighbors. The tribe was also culturally uniform, but not necessarily distinct from its neighbors in this respect. The similarity between people of a single tribe evidently gave them a feeling of community but had no further effect on their social or political organization.

The following tribes have been identified in the Athabascan area, each including several tribelets, except for the Bear River tribe, which consists of one single tribelet.

Kato: The Kato probably included at least 2 tribelets, but we have no information on this point.

Eel River Wailaki: 9 tribelets.

North Fork Wailaki: 6 tribelets.

Pitch Wailaki: 4 tribelets.

Lassik: Probably several tribelets, but there is no information.

Nongatl: There is evidence of 6 subgroups of the Nongatl. Some of these may be dialect divisions, that is, tribes. The information is not sufficient to permit definition and they have therefore been grouped under Nongatl. The extent of Nongatl territory indicates that there must have been several tribelets.

Lolangkok Sinkyone: There were at least 2, and possibly more, tribelets.

Shelter Cove Sinkyone: There were at least 4 tribelets.

Mattole: 2 tribelets.

Bear River: The Bear River tribe consists of a single tribelet.

Whilkut: The 4 subdivisions of the Whilkut—Chilula Whilkut, Kloki Whilkut, Mad River Whilkut, and North Fork Whilkut—all appear to be tribelets. It is possible that the Mad River Whilkut spoke a different dialect than the other groups and, if so, they should be given tribal status. The evidence is not clear on this point and I have therefore included them simply as a Whilkut tribelet.

Hupa: 2 tribelets are to be distinguished for the Hupa proper. In addition, Merriam distinguishes the South Fork Hupa as a distinct dialect division. The linguistic separation is not supported by Goddard or Kroeber and I have therefore included the South Fork Hupa under the Hupa proper, but as a separate tribelet. This gives a total of 3 tribelets for the Hupa.

In general, it may be stated that the California Athabascans did not have the strong local organization characteristic of Central California. Emphasis on wealth, although present, was less strongly developed than among the Yurok and therefore did not lead to the fragmented villages and tight family organization of that group. This statement, of course, does not apply to the Hupa, and probably not to the Whilkut, both of which were more like the Yurok.

Religion and the supernatural.—The clearest account of the religious practices of the Athabascans is given by Nomland (1938, pp. 93-98), who obtained her information from the Bear River woman, Nora Coonskin, herself a shaman. The account, however, may not be representative of the Athabascans as a whole.

The Athabascans thought that each person had a spirit which, leaving him when he died, might come back to earth as a small creature about two feet high. This returned spirit could communicate with shamans. When a person had a fainting spell, the spirit departed from the body and a shaman had to be called in order to get the patient's spirit back. If the shaman failed, the patient died. Shamans' spirits went to a special afterworld and were accompanied only by the spirits of other shamans.

Shamans were important among the Bear River people and probably among the other Athabascans as well. They might be either men or women; most often they were women, men being thought less powerful. The first signs of a shaman's power came in childhood, the visible signs being, for example, excessive drooling in sleep. If the childhood omens were proper, the training began about the age of twelve, under the direction of an older shaman, the main ceremony being a series of dances performed on five successive nights. Other ceremonies followed; then the girl was a full-fledged shaman. She was not supposed to use her power for a period of two to five years or it would harm her. The fee for training the initiate was large, 200 to 300 dollars in Indian money (perhaps a 6-8 ft. string of dentalia shells).

There were two types of shamans—curing shamans and sucking shamans. The curing shaman sang and danced for two nights while her spirit searched for the spirit of the patient. A shaman's fee was from five to ten dollars per night; if the patient died within two months, the fee had to be returned.

The sucking shamans could suck out pains which were causing illness. These shamans were paid more because they were more powerful; having greater power, they were in greater danger and had a shorter life expectancy.

Connections with other groups.—The foregoing account of economy, social organization, and religious practices does not by any means make up a complete picture of Athabascan life, but it illustrates certain salient factors. In particular, the connections with Northwestern California are clear. So far as influence from Northwestern California is concerned the Athabascans may be divided into three groups: the Hupa and Whilkut on the north are an integral part of the northwestern culture center; the Wailaki and Kato on the south are essentially Central Californian; and the groups in between are transitional, but more northern than southern in their outlook.

In evaluating boundaries I have relied most heavily on the information of Merriam (map 3) and Kroeber (map 1). Merriam's data are contained in a 1:500,000 map of California, together with a descriptive text. The map and the description were made up by Dr. Merriam's daughter, Mrs. Zenaida Merriam Talbot, during the years 1939 to 1946, from information in Merriam's notes and journals, the latter of which are not accessible to this writer. Often, where Merriam's boundaries disagree with those of Kroeber or other authors, Merriam's line will follow a stream, whereas the alternative follows a ridge or drainage diversion. When the evidence is inconclusive, I have usually followed Kroeber's method and chosen the ridge rather than the stream as the boundary. In this area the streams are small and easily crossed during most of the year and therefore would not constitute a barrier sufficient for the divergence of dialects. On the other hand, the hills were visited only briefly for hunting and gathering; the population depended to a great extent on the products of streams for its subsistence, and consequently all the permanent villages were in the lowlands and canyons. For this reason, the ridges rather than the streams would tend to be boundaries. Kroeber has discussed this point more generally (1939, p. 216) and also in greater detail (1925a, p. 160).

The southern boundary of the Athabascans begins at Usal Creek on the coast and goes eastward for a few miles before swinging south to include the drainages of Hollow Tree Creek and the South Fork of the Eel in Kato territory. It turns north to enclose the headwaters of South Fork and proceeds along the ridge dividing Ten Mile Creek from the main Eel until it reaches the drainage of Blue Rock Creek; it then passes around north of the creek and crosses the Eel near the mouth of the creek. From this point it runs in an easterly direction around the drainage of Hulls Creek.

Kroeber's map in the Handbook shows the southern boundary beginning a few miles south of Usal Creek, but Merriam and Nomland both maintain that the creek itself is the boundary and Gifford (1939, p. 304) says that both Sinkyone and Yuki were spoken in the village situated at the mouth of the creek. The information of all four authors came from either Sally or Tom Bell, wife and husband, who are respectively Shelter Cove Sinkyone and Coast Yuki. I have accepted Merriam's boundary, since it agrees with Nomland's.

Merriam maintains that the western boundary of the Kato runs along the South Fork of the Eel and he is partly supported in this by Barrett (1908, map), whose boundary includes the drainage of South Fork but not the drainage of Hollow Tree Creek. Barrett, however, disavows any certainty on this particular boundary. Kroeber's line, which does include the drainage of Hollow Tree Creek in Kato territory, is supported by a specific statement from Gifford (1939, p. 296) that "Hollow Tree Creek did not belong to the Coast Yuki although they fished there." I have therefore accepted Kroeber's version.

All authorities agree on the southern and eastern boundaries of the Kato as far north as the drainage of Blue Rock Creek. Merriam claims this drainage for the Wailaki, whereas both Kroeber and Foster claim it for the ta'no'm tribelet of the Yuki. It is evident that this territory was disputed, for it was the scene of several of the wars involving the Wailaki, the Kato, and the Yuki (Kroeber, 1925a, p. 165; 1925b). Kroeber obtained a detailed list of place names in this area from a ta'no'm Yuki, whereas Merriam's Wailaki information is only of a most general nature. For this reason I have given the territory to the Yuki.

All the authorities, except Foster, agree on the rest of the southern boundary of the Athabascans. Foster has the Yuki-Wailaki line cross Hulls Creek about five miles from its mouth instead of passing south of its drainage. Both Kroeber and Merriam favor the more southern line, and Goddard (1924, p. 224) says that the Wailaki claimed a fishing spot in the disputed area, so I have accepted this version.

The eastern boundary of the Athabascans runs north along the ridge separating the drainages of the North Fork and Middle Fork of the Eel until it reaches the headwaters of the Mad River. Thence it runs in a northern direction along the ridge that separates the drainage of the Mad River from that of the South Fork of the Trinity until it reaches Grouse Creek, where it turns eastward to cross the South Fork of the Trinity at the mouth of the creek. It continues north on the east side of South Fork, following the crest until it crosses the main Trinity about five miles above its confluence with South Fork, and then follows around the headwaters of Horse Linto Creek and Mill Creek.

Merriam's eastern Athabascan boundary conflicts with the one drawn by Kroeber, Foster, and Goddard in assigning the northern part of the drainage of the Middle Fork of the Eel to the Pitch Wailaki instead of to the Yuki. Merriam is almost certainly wrong here, for Goddard (1924) definitely does not include this area within Wailaki territory and his information in this region appears to have been especially reliable. Moreover, Merriam got his information from natives of the main Eel River, who were evidently not on good terms with their relatives to the east and knew little about them. I have therefore accepted the Kroeber boundary.

The next conflict is to the north of this, where Kroeber's boundary runs up the ridge separating the Mad River from the South Fork of the Trinity, whereas Merriam's runs along South Fork itself in the twenty miles from Yolla Bolly Mountain northwest to Ruth. Essene (1942) agrees with Merriam on this point, but his data add nothing to the argument, since he worked with the same Lassik informant as Merriam. I have accepted Kroeber's version because it is corroborated by both Goddard (1907) and Du Bois (1935, map 1), who agree in assigning the valley of the South Fork of the Trinity to the Wintun.

Kroeber and Merriam agree on the line running north of Ruth as far as a point about fifteen miles south of Grouse Creek, where Merriam's line drifts westward to follow the north-south channel of Grouse Creek for a short distance, whereas Kroeber's line follows due north along the drainage pattern. Essene supports Kroeber, but his informant did not come from this region so her testimony perhaps cannot be relied on heavily. I have accepted Kroeber's line because it follows the drainage pattern.

Kroeber's boundary also conflicts with Merriam's on the east side of South Fork. Kroeber's line runs along the ridge separating South Fork from the main Trinity whereas Merriam's runs along the Trinity itself. The testimony of Dixon on the Chimariko (1910, pp. 295-296) supports Kroeber, so I have accepted the latter's line.

The northern boundary of the Athabascans runs west, parallel to Mill Creek, crossing the Trinity a few miles south of its confluence with the Klamath, and then continues west until it reaches Bald Hills Ridge, which separates Redwood Creek drainage from Klamath River drainage. It continues north along this ridge and then turns east to cross Redwood Creek about ten miles southeast of Orick.

Goddard (1914a, pl. 38) indicates three Athabascan summer camps on the Yurok side of the dividing ridge. This may mean that some Athabascan territory was included in the Klamath drainage, but if so, it would contradict the testimony of the Yurok (Kroeber, 1925a, fig. 1; Waterman, 1920, map 2). However, the land away from the Klamath was little used by the Yurok (Kroeber, 1925a, p. 8), so it may be that this territory was claimed by both groups. I have accepted Kroeber's boundary here. Otherwise there are no conflicts on the northern boundary.

The western boundary of the Athabascans runs due south from Redwood Creek, following the 124th Meridian, crossing the North Fork of the Mad River at Blue Lake and crossing the main Mad River a few miles above the mouth of North Fork. From here the line follows south around the drainage of Humboldt Bay until it crosses the Eel River at the mouth of the Van Duzen, whence it runs south to Bear River Ridge, which it follows west to the ocean.

A major conflict in the western boundary of the Athabascans involves the drainage of the North Fork of the Mad River. Kroeber and Loud both assign this area to the Wiyot, whereas Merriam assigns it to the Athabascans. Neither Kroeber nor Loud gives specific data in support of his contention; thus Merriam's specific local information quoted below, renders his line preferable.

Sunday, August 11, 1918.... I found two old men of the same tribe, who were born and reared at the Blue Lake rancheria 'Ko-tin-net—the westernmost village of the Ha-whil-kut-ka tribe.

I have therefore accepted Merriam's boundary.

From the Mad River south to the Eel there is general agreement except that, as usual, Merriam's lines tend to follow the streams, whereas those of Kroeber and Loud follow the ridges. Another conflict comes at the crossing of the Eel River. Curtis (1924, 13:67) says the line crosses at the mouth of the Van Duzen. Nomland (1938, map 1), Loud, and Merriam all agree with this. Powers (1877, p. 101) and Kroeber both locate the line a few miles up the river from this point at Eagle Prairie, while Nomland's Wiyot informant (Nomland and Kroeber, 1936, map 1) places the line even farther south at the mouth of Larabee Creek. The weight of evidence indicates that the line was probably near the mouth of the Van Duzen; Goddard (1929, p. 292) states that there was a Bear River village near there.

There is also some disagreement on the northern boundary of the Bear River group. Nomland says that it is at Fleener Creek, about five miles north of Bear River Ridge, whereas Kroeber indicates a line about two miles north of Bear River Ridge. Loud, Merriam, and Goddard, on the other hand, all indicate that the boundary is Bear River Ridge itself. Nomland's boundary is almost certainly in error, since Loud gives Wiyot villages occurring south of that line. Most of the evidence points to Bear River Ridge as the line, and this version has been accepted.

There is no disagreement on the western boundary of the Hupa. It runs north and south along Bald Hills Ridge, dividing the drainages of Redwood Creek and the Trinity River. Merriam gives the Hupa two divisions—the Tin-nung-hen-na-o, or Hupa proper, and the Ts┤ă-nung-whă, or Southern Hupa. The line dividing these two groups lies just north of the main Trinity to the east of South Fork and along Madden Creek to the west of South Fork. Kroeber (1925a, p. 129) and Goddard (1903a, p. 7) do not give any support for a linguistic division, as indicated by Merriam, but there does seem to have been some cultural difference.

In the division of the territory west of the Hupa Merriam differs radically from Kroeber and Goddard, although all three scholars divide the area between two groups. Kroeber and Goddard call the northernmost group Chilula, an anglicization of the Yurok word tsulu-la meaning "Bald Hills people," and the southern, Whilkut, from the Hupa word hoilkut-hoi meaning "Redwood Creek people" or "upper Redwood Creek people."

Merriam calls the first of his two divisions Hoilkut and says that they lived on Redwood Creek and on the North Fork of the Mad. This group he further subdivides into three parts: one, living on lower Redwood Creek, corresponds to the Chilula of Kroeber and Goddard; another, on upper Redwood Creek, corresponds to part of Kroeber's Whilkut; and a third, on the North Fork of the Mad River, corresponds to a part of Loud's Wiyot.

Merriam calls his second division Ma-we-nok. They live in the drainage of the main Mad River and correspond to a part of Kroeber's Whilkut.

It would appear that, except for Goddard's Chilula information (Goddard, 1914a), Merriam's data are the most detailed and therefore preferable. He had informants from lower Redwood Creek, from the North Fork of the Mad River, and from the main Mad River. For this reason I have accepted his boundaries. I therefore propose that all the peoples previously included under the terms Whilkut or Chilula be called Whilkut. This seems justified by Merriam's statements, on the one hand, that the Mad River Ma-we-nok differed but little in speach from their Whilkut neighbors, and, on the other hand, that the other groups in the area called themselves hoilkut or terms related to this.

Map 1. Athabascan boundaries: Kroeber vs. Baumhoff.

Map 2. Athabascan boundaries: Baumhoff.

Map 3. Athabascan boundaries: Merriam vs. Baumhoff.

Map 4. Athabascan boundaries: various authors vs. Baumhoff.

If this proposal is accepted, the Whilkut may then be divided into four subgroups—the Chilula Whilkut, the Kloki Whilkut, the Mad River Whilkut, and the North Fork Whilkut. The Chilula Whilkut would occupy essentially the territory assigned to the Chilula by Goddard and Kroeber—the drainage of Redwood Creek from about ten miles southeast of Orick to about a mile above the mouth of Minor Creek. Above them are the Kloki Whilkut, occupying the upper drainage of Redwood Creek. The name Kloki Whilkut means "prairie" Whilkut, a name used by these people for themselves, according to Merriam, and derived from the prairies that occur on upper Redwood Creek. The Mad River Whilkut would be the group in the drainage of Mad River from the mouth of North Fork as far up as Bug Creek above Iaqua Buttes. The North Fork Whilkut would then be the group in the entire drainage of the North Fork of the Mad River.

The northern boundary of the Nongatl begins in the west near Kneeland at the Wiyot boundary and runs southeast around Iaqua Buttes and the drainage of the Mad River, then northeast to Grouse Creek. Kroeber and Merriam agree on this boundary east of Iaqua Buttes, but west of that landmark Merriam's line takes a northeast-southwest direction whereas Kroeber's line runs due east-west. I have accepted Merriam's line here because he has more detailed information than Kroeber on the neighboring Whilkut. Neither has much information on the Nongatl themselves.

One of the main interior lines of the Athabascans is the one which, running north and south along the South Fork of the Eel, divides the coastal groups on the west from the interior peoples to the east. It begins at the mouth of the Van Duzen on the main Eel and runs south along the Eel as far as Scotia, dividing the Nongatl from the Bear River group. At Scotia it coincides with the Sinkyone-Nongatl boundary and then continues in a southerly direction but, instead of lying immediately on the river, it drifts slightly to the east to include also the land adjacent to the stream. It continues thus near to, but off, the main Eel until it crosses the river at about McCann, a few miles above the mouth of South Fork. After crossing the main Eel, the line goes south, including the immediate river valley of the South Fork of the Eel in Sinkyone territory, until it turns west to cross South Fork at the mouth of Hollow Tree Creek, continuing to the coast at Usal Creek.

This section of the Athabascan boundary has been much disputed. It seems certain that the western side of the Eel from the mouth of the Van Duzen to Scotia was Bear River territory. This distribution is attested by Powers (1877, p. 107), who says that the Bear River group owned as far south as the mouth of South Fork, by Nomland's Bear River informant (1938, map 1), by Kroeber, and by Goddard, who says (1929, p. 291), "There was, however, one village at the mouth of Van Duzen creek which was allied to Bear River both in its dialect and politically." This evidence is fully in accordance with that of Merriam.

The eastern side of the river along this stretch goes to the Nongatl by default. Kroeber claims it for the Bear River people and Nomland's Wiyot informant claimed it for the Wiyot (Nomland and Kroeber, 1936, map 1) but except for these sources possession is denied by Wiyot, Bear River, and Sinkyone alike.

South of Scotia the area is also in dispute. Nomland and Kroeber claim that the eastern side of the Eel from Scotia to the mouth of South Fork is Nongatl. They say (1936, p. 40):

In any event, Eel river from Scotia to Larrabee was not Mattole, as Kroeber has it in map 1 of his Handbook, nor was it Sinkyone. Nomland's Bear River, Mattole, and Sinkyone informants were positive on the point. If Athabascan, the stretch in question belonged to the Nongatl (Saia). Otherwise it was Wiyot.

Merriam, on the contrary claims that this territory was definitely Sinkyone.

We must evaluate the statements of the informants involved before reaching a decision on this point. Nomland's Bear River informant was evidently not particularly accurate on boundaries, for she placed the northern boundary of the Bear River group at Fleener Creek when it was almost certainly at Bear River Ridge (see p. 163). Therefore her testimony may be questioned on the present point also. Nomland's Sinkyone informants were from the Shelter Cove Sinkyone of the Briceland area to the south, and furthermore only one of them was said to be reliable. Merriam, however, presents detailed evidence in the form of place names obtained from George Burt, a very good informant who was born and raised among the northern Sinkyone at Bull Creek. I have therefore accepted the evidence of George Burt via Merriam, even though several of Nomland's informants deny it.

Actually, I have accepted Merriam's line as far south as Phillipsville on the South Fork of the Eel, even though it conflicts somewhat with the lines of Nomland and Kroeber. Merriam's information for this stretch of South Fork is supported in detail by Goddard's village lists. South of Phillipsville, Merriam's line runs along South Fork itself instead of lying slightly east of it. This line is contradicted by Goddard, whose informant, a native of the region, gave Goddard village names on both sides of the river as far south as Garberville. I have accepted the line indicated by Goddard's information along this stretch.

South of Garberville I have relied heavily on Nomland. She had three informants from the Shelter Cove Sinkyone—Sally Bell, Tom Bell, and Jack Woodman, of whom she considered only the last reliable. Merriam seems to have relied entirely on Sally Bell for information about this group and his information should therefore be somewhat discounted.

The Bear River-Mattole boundary is not disputed. Merriam and Nomland agree that it begins on the coast at Davis Creek and then follows the ridge east to the headwaters of Bear River. The two authors do not agree on the Bear River-Sinkyone line. Nomland's boundary goes due east from Bear River headwaters to strike the South Fork of the Eel a few miles above its mouth. Merriam's line instead goes north to intercept the main Eel at Scotia. I have accepted Merriam's version on the basis of George Burt's evidence, even though Kroeber agrees with Nomland.

The Mattole-Sinkyone boundary begins at Spanish Flat on the coast and goes northeast from there, crossing the Mattole River just above the mouth of Upper North Fork, Mattole River, and continuing in that direction to the headwaters of the Bear River. I have altered Merriam's map on this point. It shows the Mattole-Sinkyone line reaching the coast at Big Flat, a point about six miles down the coast from Spanish Flat. Merriam's notes say, however, that the line ends at Spanish Flat. Merriam's line crosses the Mattole River near the town of Upper Mattole about five miles below the mouth of Upper North[Pg 165] Fork, but Goddard's Mattole informant gave him villages as far up as the mouth of Upper North Fork and I have considered this fact to be decisive. Nomland's Mattole-Sinkyone line reaches the coast at Four Mile Creek, about five miles up the coast from Merriam's line at Spanish Flat. This line of Nomland's is probably a tribelet boundary, which Merriam and Goddard give as occurring at about that point (see Mattole Tribelets). Otherwise Nomland's boundary agrees with that of Merriam.

Merriam's line dividing the northern or Lolangkok Sinkyone from the southern or Shelter Cove Sinkyone begins in the east on South Fork Eel about a mile or two above the mouth of Salmon Creek, runs west from there through Kings Peak, and crosses the Mattole River just north of Ettersberg, intersecting the Mattole line a few miles from the coast. This line as given is the same as Merriam's, except that his begins in the east at Redwood Creek instead of at Salmon Creek. The change here is based on Goddard's village list, which indicates the present line.

The Lassik-Nongatl line begins in the east just below Ruth on the Mad River. It goes west from there around the headwaters of the Van Duzen River until it crosses the Eel at the mouth of Dobbyn Creek and thence west to the Sinkyone line. Kroeber and Merriam agree on the eastern part of this line but Essene disagrees with them, including a much larger portion of the drainage of the Mad and Van Duzen rivers in Lassik territory. I am at a loss to explain this version, since Essene's informant from the Lassik was the same one consulted by Merriam. It is not clear that Essene's boundaries were obtained from his informants, and this fact may explain the discrepancy. I have accepted the Kroeber-Merriam line here. To the west of this, Kroeber's line, instead of crossing the Eel, follows the river toward the northwest, so none of the main Eel River valley falls in Nongatl territory. Goddard gives villages on the main Eel which are said to be allied with others in the Blocksburg region, so the Nongatl must have claimed at least a small section of the Eel. I have therefore accepted the Merriam version.

The Wailaki-Lassik boundary begins in the east at the head of the Mad River and runs west to the North Fork of the Eel, which it crosses at the mouth of Salt Creek. It follows Salt Creek for a short way and then goes west to Kekawaka Creek, which it follows to its mouth on the main Eel. It crosses the Eel here and then goes west to intersect the Sinkyone boundary at the East Branch of the South Fork of the Eel. The boundary as given here is identical with the one given by Merriam, except that he includes part of the drainage of the Mad within Wailaki territory whereas Kroeber does not. I have accepted Kroeber's version, because it is supported in a negative way by Goddard (1924), who fails to include any Mad River drainage in Pitch Wailaki territory.

West of this area, Kroeber's boundary runs considerably north of Merriam's and of the boundary I have accepted. Merriam's line seems preferable because it is supported by Goddard and because Merriam's information is more specific than Kroeber's.

According to the information of Merriam and Goddard, the Wailaki may be divided into three groups—the Eel River Wailaki, the North Fork Wailaki, and the Pitch Wailaki. The eastern group, the Pitch Wailaki, occupy the drainage of North Fork Eel River above Asbill Creek, Hulls Creek, and Casoose Creek. Their western boundary begins in the north on Salt Creek near its confluence with North Fork Eel. It runs south from this point along Salt Creek and beyond it, crossing the North Fork of the Eel just above the mouth of Asbill Creek and intersecting the Yuki-Wailaki line near Summit Valley. The northern border of the North Fork Wailaki begins in the west on the main Eel River at the mouth of Cottonwood Creek, about three miles north of the mouth of North Fork Eel, and runs from there eastward for about six miles, where it hits the western boundary of the Pitch Wailaki. The western boundary of the North Fork Wailaki is the main Eel River from the mouth of Cottonwood Creek south to the Yuki line near Bell Springs Railroad Station.

The Kato-Wailaki line runs from the head of Blue Rock Creek in the east to the mouth of Hollow Tree Creek on the South Fork of the Eel in the west. This is Kroeber's version of the boundary. Merriam's version places the line somewhat south of this, beginning at Rattlesnake Creek in the west and going eastward south of Blue Rock Creek. Since I have ceded the drainage of Blue Rock Creek to the Yuki (see p. 160) in accordance with the views of Kroeber, I must, as a corollary, accept the northern boundary of the Kato as given by him.

The net result of the foregoing discussion is that the line surrounding the Athabascan peoples of Northwestern California remains much the same as Kroeber showed it in 1925, whereas the tribal boundaries are considerably changed. In the north, the Chilula and Whilkut occupy almost entirely different areas and the Hupa have been divided into two subgroups. On the coast, the Bear River and Mattole are divided, but this division had been shown by Goddard and Nomland previously. The Sinkyone have been divided into two subgroups and the Wailaki into three.

A really major difference is the accretion of territory by the Nongatl. This group is one about which least is known and this may be the reason why the map shows their territory as so extensive. It is very likely that data from a few good informants would show that the Nongatl actually comprise several distinct groups. There is a hint of this in Essene's account of Lassik war stories (1942, p. 91). He notes that the Nai'aitci, centering near the town of Bridgeville, were distinct from the Blocksburg people. Both of these groups are placed within the Nongatl area. No doubt more detailed information than we possess would show that the area which we have labeled Nongatl was actually occupied by two, three, or even more distinct groups.

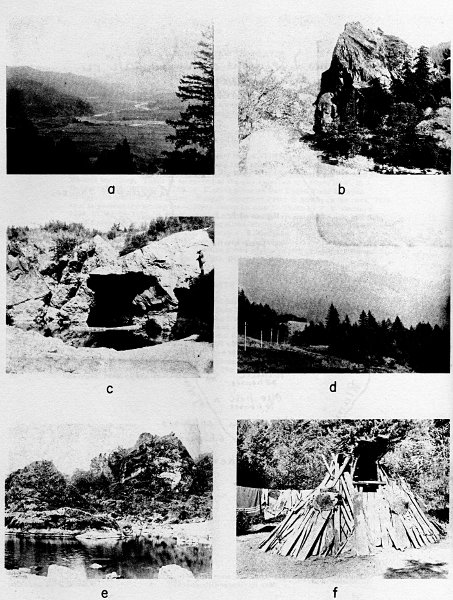

The Kato are the southernmost of the California Athabascans (see pl. 11, e for a view of Kato territory). They are surrounded on three sides by Yukian peoples and consequently resemble culturally the peoples of Central California rather than those of Northwestern California. The name Kato appears to be of Pomo origin and it was first thought that the Kato language was a dialect of Pomo (Powers, 1877, p. 147). It was not until 1903 that Goddard showed their Athabascan affinity (Goddard, 1903b).

Information on the ethnogeography of the Kato is derived from several sources. Merriam's notes contain some information, which seems to have come from a man named Bill Ray, who was living near Laytonville on August 16, 1922. This man had been Goddard's informant in 1906, when Ray was already between sixty and sixty-five years old (Goddard, 1909, p. 68, pl. 9) and he served also as Kroeber's informant in 1923 (Kroeber, 1925b).

The Merriam notes contain, in addition to several village names, a few place and tribal names which I present herewith.

Kato: to-chil┤-pe ke┤-ah-hahng

Jackson V. people (inc. Branscom): sin┤-kōk ke┤-ah-hahng

Wailaki: we┤-tahch

Yuki of Round V.: chinch┤

Coast Yuki: bahng┤-ke┤-ah-hahng

Southern Sinkyone: ketch┤-ing ke┤-ah-hahng

Tribe on the N side of Rattlesnake Cr. and E of South Fork Eel division of Wailaki (?): tek┤ ke┤-ah-hahng

Long V.: kin-tĕhl-pe

Laytonville: ten-tahch-tung

Cahto Pond (now drained): to-chil┤-pa

Long V. Cr.: shah┤-nah

South Fork Eel R.: nahs-ling┤-che

Rattlesnake Cr.: tal-tlōl┤-kwit

Main Eel R.: tah-ke┤-kwit

Blue Rock: seng-chah┤-tung

Bell Springs: sĕch-pis

Round V.: kun-tel-chō-pe

Jackson V.: kus┤-cho-che┤-pe; kas-tos┤ cheek┤-be

Branscomb Mt.: kīk; chīs┤-naw

The villages of this group are mostly taken from Barrett (1908, pp. 280-283) indicated below by (B). Those taken from Merriam's notes are distinguished by (M). The information given with each of the villages is sometimes a direct quotation but most often is paraphrased.

1. netce'līgűt (B). At a point about 9 mi. nearly due W of the town of Laytonville and about 3 mi. SE of the confluence of the E fork of the South Fork of Eel R. with the South Fork of Eel R. This village is on top of the ridge separating these two streams and is on the property of Mr. Jacob Lamb.

2. yictciLti'˝kűt, "wolf something-lying-down creek" (B). On the S bank of Ten Mile Cr. at a point about 5 mi. WNW of the town of Laytonville.

3. sentca'ūkűt, "rock big creek"; or kave'mato (Northern Pomo dialect name), "rock big" (B). On Big Rock Cr. at a point about 1-1/2 mi. from its confluence with Ten Mile Cr., or about 5-1/2 mi. nearly due W of the town of Laytonville.

sen-chow┤-ten (M). Kato name for their village at Big Rock, about 4 mi. N of their present rancheria in Long V.

4. ka'ibi, "nuts in" (B). On the NE bank of Ten Mile Cr. at a point about 3 mi. downstream from the town of Laytonville.

5. nebō'cēgűt, "ground hump on-top" (B). On what is known as the Wilson ranch at a point about 1 mi. W of Laytonville.

6. seLgaitceli'nda, "rock white run-out" (B). About 300 yds. E of the house on what is known as the "old" John Reed ranch about 1 mi. N of Laytonville.

7. bűntcnōndi'lyi, "fly settle-upon under" (B). Just NW of Laytonville and but a short distance from the place now occupied by the Indians near Laytonville.

8. ko'cbi, "blackberry there" (B). About 1-1/2 mi. WSW of Laytonville and on the SW bank of the Ten Mile Cr.

9. tcībē'takűt, "fir tips creek" (B). About a mile SW of the town of Laytonville and about 1/2 mi. up the creek which drains Cahto V. from its confluence with Ten Mile Cr.

che-pa-tah-kut (M). A former village in the northern part of Long V. on the James White place.

10. distēgű'tsīū, "madrona crooked under" (B). On the western side of Long V. at a point about 2 mi. SSE of Laytonville.

11. tōdji'Lbi, "water? ... in" (B). At the site now occupied by the Indians at Cahto. This site is on the W bank of the small creek running from Cahto into Ten Mile Cr.

12. bűntctenōndi'lkűt, "fly low settle-upon creek" (B). On the N bank of the northern branch of the head of the South Fork of the Eel R. at a point about a mile SSW of Cahto.

13. kűcyī'ūyetōkűt, "alder under water creek" (B). On the N bank of the South Fork of Eel R. at a point about 3 mi. SW of Cahto. This site is about 1/2 mi. E of the ranch house on the Clark ranch.

14. ne'īyi, "ground under" (B), probably signifying that the village was situated under a projecting ridge. On the S bank of the South Fork of Eel R. at a point about 3 mi. S of Branscomb.

15. sēne'tckűt, "rock gravel creek" (B). On the NW bank of the small stream known as Mud Springs Cr., which is tributary to the South Fork of Eel R. This site is about 3 mi. a little S of E of Branscomb. There are on this creek, and not far from this village site, several springs which flow a very thin blueish mud, thus giving the creek its name.

16. tontce'kűt, "water bad creek" (B). About 1/4 mi. W of the South Fork of Eel R. and about 1 mi. SW of Branscomb.

17. senansa'nkűt, "rock hang-down creek" (B). On the E bank of the South Fork of Eel R. at a point about 1-1/2 mi. downstream from Branscomb.

In addition to this list, there are two other sources of information on villages. First, Curtis (1924, 14:184) presents a list of six villages, almost all of which it is impossible to locate. None of the names corresponds to any given by either Barrett or Merriam, and they are therefore suspect as village names, though they may be valid place names and are certainly good Athabascan. In the list below Curtis' orthography has been changed slightly. The changes follow the pattern set by Curtis in his Hupa village lists (Curtis, 1924, Vol. 13).

| chunsandung, "tree prostrate place" | 1-1/2 mi. W of Laytonville on the site of the cemetery |

| tsetandung, "trail emerges place" | At the foot of the mountain W of Laytonville |

| totakut, "water center" | N of tsetandung. On a knoll down which water flowed on two sides |

| chekselgindun, "they killed woman place" | N tsetandung |

| yitsche Ltindung, "they found wolf place" | |

| seyuhuchetsdung, "old stone house place" |

The second source is the notes of Goddard, who did extensive work in the area in 1906 (Goddard, 1909), though mostly on language and myth. His notes contain information on two villages, neither of which can be located because the township and range co÷rdinates have been changed since the time of recording and also because the name of the creek mentioned does not appear on maps in my possession. The two cards bearing the information have the penciled notations 51 and 52 written on their corners. This indicates that Goddard had recorded at least 50 other sites for the Kato, a conclusion which is further corroborated by his own statement (Goddard, 1909, p. 67). Our information on Kato villages is therefore correspondingly incomplete.

neεƚsoki, "ground blue tail" SW sec. 26, T. 22 N., R. 15 W. On a flat 200 yds. N of Blue Hill Cr. and 150 yds. W of the river. There are 3 deep pits on the eastern edge of the higher flat. Bill thought there were 3 others 100 yds. S where a white man's house had stood, ne'ƚsōkī kīyahűn.

t'unƚtcintcki, "leaves black tail" W sec. 26, T. 22 N., R. 15 W. On the higher bank 50 yds. N of tűnƚtcintckwōt, the next creek N of Blue Hill Cr. and 400 yds. W of the river. There is timber W. Dr. Wilson used to live there. The site has been plowed. Bill counted six places where he thought houses had been.

The Wailaki, the southernmost group of Athabascans on the Eel River, are as little chronicled as most of the Athabascan groups. As far as geography and language are concerned we have very good information (Goddard, 1923a; 1923b), but there is very little general ethnography. Kroeber was able to devote to them only a little more than three pages in the Handbook (1925, pp. 151-154), and we know scarcely more today.

The territory of the Wailaki lies for the most part outside the redwood forest (pls. 11b, c) and for that reason they had access to a more abundant supply of the food, particularly acorns, used by the interior peoples than did most of the Athabascan groups. Perhaps for this reason, or perhaps simply because of proximity, the culture of the Wailaki shows considerable affinity with the culture of Central California and correspondingly less with that of Northwestern California. This affinity is particularly evident in their tribelet organization, which obtrudes itself in the accounts of both Goddard and Merriam. In the groups farther north such organization receives little attention.

Merriam's information on the Wailaki consists for the most part of ethnogeography, including villages, tribelets, and place names. His informants in this group were Fred Major and Wylakki Tip. I have been able to find out nothing about Fred Major, but Merriam gives the following statement on Wylakki Tip.

My informant, known as Wylakki Tip, a full blood Tsennahkennes [Eel R. Wailaki, but see Kroeber's data, p. 229], whose father and mother were born and lived at Bell Springs, tells me that they belonged to the Bell Springs Canyon band known as Tsi-to-ting ke-ah, named from the neighboring mountain tsi-to-ting. He adds that from the mouth of Blue Rock Creek northward the Tsennahkennes owned the country to the main Eel, and that the present location of Bell Springs Station, on the west side of the river, is in their territory but that the east side of the river from Bell Springs Station to the mouth of Blue Rock Creek was held by a so-called Yukean tribe.

In Merriam's notes there is no general statement on the Bahneko or North Fork Wailaki; he was evidently somewhat undecided whether they were truly a distinct group. However, he comments on the Tsennahkennes, or Eel River Wailaki, as follows.

Map 5. Villages and tribelets of the Eel Wailaki and the North Fork Wailaki. Roman numerals indicate tribelets, arabic numerals village sites.

Tsennahkennes ... A Nung-gahhl Athabascan tribe in north-central Mendocino County, California, occupying the greater part of the mountainous country on both sides of main Eel River from Red Mountain and the upper waters of East Branch South Fork Eel easterly to Salt Creek, and from a few miles south of Harris southerly to Rattlesnake Creek. Their territory thus includes the major part of Elkhorn Creek, the headwaters of East Branch South Fork Eel, Milk Ranch Creek, and Red Mountain Creek, practically all of Cedar Creek, and the whole of Bell Springs and Blue Rock Creeks. The old stage road from Cummings north to Harris, passing Blue Rock and Bell Springs, traverses their territory.

It is clear that in recording Wailaki words Merriam followed the same principles that guided him in his published works on other Californian languages. In transcribing the Achomawi language he said (1928, p. vi), "All Indian words are written in simple phonetic English, the vowels having their normal alphabetic sounds." For a more precise determination I have made a comparison of words recorded by both Merriam and Goddard. The values of the symbols used by Goddard are taken from a list he gives in his Wailaki Texts (1923b, p. 77) together with Phonetic Transcription of American Indian Languages (Amer. Anthro. Assoc., 1916), a report which Goddard helped prepare.

A total of twenty-eight words recorded by both Merriam and Goddard were found. Although the discrepancies seem great, this is because Merriam used Webster's English orthography whereas Goddard used a technical one modified from the old Smithsonian system. Whatever the limitations of Merriam's orthography for considerations of grammar (which he did not try to obtain), his recordings consistently check Goddard's independent information and serve as complete identifications of places and ethnographic facts.

| Labial | Apical | Frontal | Dorsal | ||

| Stops | fully voiced | g | |||

| medium voiced | b | d | G | ||

| voiceless non-glottalized | t | k | |||

| voiceless glottalized | t' | k' | |||

| Affricates | non-glottalized | ts | tc | ||

| glottalized | ts' | tc' | |||

| Spirants | voiceless | s | c | ||

| voiced | |||||

| Nasals | n | ˝ | |||

| Semivowels | w | y | |||

| Laterals | voiced | l | |||

| voiceless | ƚ | ||||

Goddard gives the following vowels.

i as in pique (written with an iota by Goddard)

e as a in fate

E as in met (written with an epsilon by Goddard)

a as in father

A as u in but (written with an alpha by Goddard)

o as in note

Following is a rough correspondence between Goddard's and Merriam's orthographies.

| Goddard | Merriam |

| a | ah (occasionally a or e) |

| A | ah, e, u, i (in order of frequency) |

| ai | a, i |

| Ai | i |

| b | b |

| c | s (once sh) |

| d | d, t |

| e | e |

| E | e, ā |

| g | ƚg written as sk |

| G | does not occur |

| h | h |

| i | ē, ĕ (oi written i) |

| I | i, u |

| k | k (ky written ch) |

| k' | k |

| l | does not occur |

| ƚ | kl, often not recorded at all (ƚ written sk) |

| m | n (Goddard says n sometimes becomes m by assimilation. Evidently it is n phonemically) |

| n | n (occasionally ng, once not recorded at all) |

| ˝ | ng (occasionally n, twice not recorded at all) |

| o | o (occasionally u) |

| s | s |

| t | t |

| t' | does not occur |

| tc | ch (once tch) |

| tc' | does not occur |

| ts | does not occur |

| ts' | does not occur |

| u | does not occur |

| w | does not occur |

| y | y, ky written ch, kiyah always written ke-ah or ka-ah |

The subgroups of the Wailaki (map 5) are called bands by Merriam and subtribes by Goddard but it is clear that they correspond precisely to the definition of tribelet given by Kroeber (1932, pp. 258-259), a fact which Kroeber noted at the time (p. 257). Goddard says (1923a, p. 95):

[They] had definite boundaries on the river as well as delimited hunting grounds on an adjoining ridge. In the summer and fall they appear to have been under the control of one chief, and to have camped together for gathering nuts and seeds and for community hunting. In winter they lived in villages and were further subdivided.

I. There is close agreement on the boundaries of the northernmost Wailaki tribelet on the western side of the Eel. Merriam gives the names kun-nun┤-dung ke┤-ah-hahng, ki┤-kot-ke-ah-hahng, ki-ketch-e kā-ah-hahng, and ki-ke┤-che ke┤-ah-hahng as designations for the group. He says the territory of this group runs from Chamise Creek in the north to Pine Creek in the south. Goddard gives the same name (rendered kaikitcEkaiya) and the same boundaries for the group.

The territory north of Chamise Creek on the west side of the river is assigned by Merriam to the taht┤-so ke┤ah tribelet of the Lassik. This attribution would seem to indicate that Merriam has put his northern Wailaki boundary too far north, that it should hit the Eel at Chamise Creek rather than at Kekawaka Creek. Goddard calls these people the daƚsokaiya, "blue ground people," which no doubt corresponds to taht┤-so ke┤ah. He says, "It is doubtful that they should be counted as Wailaki, but they were not Lassik and probably spoke the same dialect as the Wailaki."

II. This tribelet is called sĕ-tah┤-be ke┤-ah-hahng or sā-tah┤-ke-ahng by Merriam. In one place his notes say that the territory includes land on both sides of the Eel, running south of Indian Creek on the western side. This is clearly not so, for he refers several times to a different tribelet occupying that area. That the tribelet was confined to the east side of the river is further indicated by Goddard, who gives Pine Creek on the north and Natoikot Creek on the south as the boundaries. Goddard's name for the tribelet is sEtakaiya.

III. Goddard says that there was a tribelet on the west side of the Eel whose territory was bounded on the north by Natoikot Creek and extended south to a point opposite the mouth of North Fork. His name for this group is taticcokaiya. Merriam's name for the group in this general area is tah-chis┤-tin ke-ah-hahng. He does not give any boundaries for them.

IV. and V. Merriam gives the following names for the tribelet occupying the territory around Blue Rock and Bell Springs Creeks: tsi-to┤-ting ke┤-ah, from the name of Bell Springs Mountain; sen-chah┤-ke┤-ah; sĕ-so ke┤-ah-hahng, "Blue Rock Band"; then┤-chah-tung kā┤-ah, "Blue Rock Band." On the other hand, he gives the following names for the people who occupied the west bank of the Eel for a mile or more south of the mouth of North Fork: nin-ken-nētch kā-ah-hahng; nung-ken-ne-tse┤ ke┤-ah; nĕ-tahs┤ ke-ah-hahng. Goddard says that the entire stretch from the mouth of North Fork south to Blue Rock Creek on the west bank of the river was occupied by a single tribelet called nI˝kannitckaiya, a name clearly corresponding to Merriam's names for the people on the west bank of the Eel, south of North Fork. I am inclined to think that Merriam is correct and that there were two tribelets in this area. Merriam's notes include five different references to the southern tribelet as a separate group, so there is a distinct impression of autonomy. If Merriam is correct in separating the two groups, the division line no doubt falls a mile or two north of Bell Springs Creek.

VI. On the eastern side of the river Merriam gives two names for the tribelet holding the land south from Kekawaka Creek. He says the yu-e-yet┤-te ke┤-ah was the tribelet north of Chamise Creek. Their southernmost village, called sko┤-teng, was on the east side of the river a half-mile or a mile south of Kekawaka Creek. The sko┤-den ke┤-ah Merriam gives as the name of the tribelet on the east side of the Eel River and about a half-mile south of Kekawaka Creek. Goddard gives iƚkodA˝kaiya, corresponding to Merriam's sko┤-den ke┤-ah, as the name of the group extending from about two miles south of the mouth of Chamise Creek nearly to the mouth of Kekawaka Creek. Both Merriam and Goddard indicate some doubt whether these people were Wailaki.

VII. Merriam gives the names chēs-kot kē-ah-hahng, chis┤-ko-ke┤-ah, and tōs-ahng┤-kut for the tribelet living in Horseshoe Bend. The first two names come from the word chis-kot, the name for Copper Mine Creek. Goddard also gives these last two names for the group (written tciskokaiya and tosA˝kaiya, "water stands people"), and he says their territory includes the land between Copper Mine Creek on the south and a point a mile or two south of Chamise Creek on the north.

VIII. Goddard says that a tribelet named slakaiya or sEyadA˝kaiya occupied the territory between Copper Mine Creek in the north and Willow Creek in the south. Merriam gives the name nung-ken-ne-tse┤ ke┤-ah to this group, which he locates on the east side of the Eel River at Island Mountain. He gives no boundaries for the group.

IX. Merriam gives two names for the tribelet occupying the Indian Creek region. The chen-nes┤-no-ke┤-ah was the band on chen-nes-no┤-kot Creek (Indian Cr.) from Lake Mountain to the Eel River; he also writes this name ken-nis-no-kut ke-ah-hahng. His other name for the group has the variants bas-kā┤-ah-hahng, bas-ki┤-yah, bus-kā-ah-hahng. This group is said to have been on the east side of the Eel River a mile or two north of Indian Creek (in the Fenton Range country). Goddard gives the name bAskaiya, "slide people," corresponding to the last of Merriam's names, for the tribelet from Willow Creek south to Cottonwood Creek. The name refers to a hillside, usually of clay, which has broken loose and has slid down.

X. Merriam identifies no group as occupying the land from Cottonwood Creek south to the mouth of North Fork. Goddard says the region was occupied by a tribelet called sEƚtchikyokaiya, "rock red large people."

XI. Merriam says the sā┤-tan-do┤-che ke┤-ah-hahng was the name of a tribelet on the north side of North Fork and about a half-mile from its junction with the main Eel. The name means "rock reaching into the water." Goddard's name for this same group is sEtando˝kiyahA˝, a clear correspondence, and he indicates that their land was on about the last mile of North Fork.

XII. According to Merriam the next group up North Fork was named sĕ-cho ke┤-ah-hahng. Its land was on the north side of North Fork a mile or more above its mouth. Goddard has the same name for the group, sEtcokiyahA˝; he says the people occupied both the north and south sides of a one-mile stretch of North Fork beginning a little way below the mouth of Wilson Creek and extending downstream from there.

XIII. Merriam says ki┤-ye ke┤-ah-hahng was the name of the tribelet on both sides of North Fork at the mouth of Wilson Creek. This is in accord with Goddard's data. He gives the name as kAiyEkiyahA˝. Neither Goddard nor Merriam gives the limits of this group up North Fork. Presumably they coincide with the tribal boundary.

XIV. According to Goddard a tribelet called nEƚtcikyokaiya was in possession of the territory on the east bank of the Eel from McDonald Creek northward to the mouth of North Fork. Merriam does not record this group.

XV. The southernmost tribelet on the eastern side of the Eel is called sEƚgAikyokaiya, "rock white large people," by Goddard. They are said to have occupied the territory from McDonald Creek south to Big Bend Creek. This group is not recorded by Merriam.

The list of villages which follows includes all those contained in Merriam's notes and also all those given by Goddard (1923a) that could be located with accuracy (map 5). Occasionally there is a conflict between Merriam and Goddard and then it has usually seemed best to accept Goddard's information, since he actually visited the sites of most of the villages he mentions.

All the data are either from Merriam or Goddard, as indicated by (M) or (G). Ancillary comment by myself is placed in square brackets. The notations (Tip) and (Maj) refer to Merriam's informants (see p. 167). The arabic numbers correspond with those on map 5, indicating separate villages. These run consecutively from north to south, first on the west side of the Eel (1-22) and then on the east side (23-67).

1. The main village of the ki-ketch-e tribelet is said to have been on the S side of the mouth of Chamise Cr. (M).

kAntEltcEk'At, "valley small on" (G). The most northern village of the kaikitcEkaiya, whose northern boundary was Chamise Cr.

[Both Merriam and Goddard give this as the native village of the wife of Wylakki Tip so there is no doubt that they are referring to the same village.]

2. kun-tes-che┤-kut (M). Said to have been a Wailaki village on the W side of the Eel R. a half-mile N of Horseshoe Bend Tunnel, probably nearly opposite Horseshoe Bend Cr. (Tip).

[Horseshoe Bend Tunnel cuts out the meander of Horseshoe Bend. Horseshoe Bend Cr. appears to enter the Eel from the E about a mile S of Boulder Cr. If Goddard's kAntEltcEk'At is really kAntEƚtcEk'At, with the bar on the "l" dropped in error, then these names are nearly the same. If so, kun-tes-che┤-kut might be the name of village no. 1 even though the location differs slightly.]

3. basEtcEƚgalk'At, "throw stone outside on" (G). On the western side of the Eel, just N of the mouth of Pine Cr.

4. sEdAkk'a˝dA˝, "rock ridge place" (G). On the point of the ridge around which the Eel turns toward the W at Horseshoe Bend.

5. kit-te-ken-nĕ┤-din (Tip), kit-ken-nĕ-tung (Maj) (M). At or near the S end of Horseshoe Bend Tunnel. It was the biggest village of the tribelet and was said to have been the native village of the father of Wylakki Tip.

sĕ-tah┤-be (M). A large village on the W side of the Eel River just S of Horseshoe Bend Tunnel near Island Mt. Station. It was nearly opposite the mouth of Copper Mine Cr.

tcInnaga˝tcEdai, "eye closed door" (G). At the base of the ridge described in no. 4. It was said to have been the home of Captain Jim.

[These names may or may not refer to the same village. If they do, it is likely that Merriam's kit-te-ken-nĕ┤-din is the correct one. His sĕ-tah┤-be evidently refers to the name of the tribelet, sEtakaiya, given by both him and Goddard. Goddard's designation looks as though it might very well refer to the tunnel and thus would be very modern.]

6. lacEƚkotcEdA˝, "buckeye small hole place" (G). This seems to have been only a few hundred yards S of Horseshoe Bend.

7. kaigAntcik'At, "wind blows up on" (G). A big winter camp about 1/4 mi. S of Horseshoe Bend.

8. sait'otcEdadA˝, "sand point on" (G). Also about 1/4 mi. S of Horseshoe Bend but was about 500 ft. above the river near a big spring.

9. tcIbbEtcEki, "gather grass tall" (G). A little more than a mile S of Horseshoe Bend a very small stream runs into the Eel from the W. On the N side of the mouth of this stream was this house site where Captain Jim's father used to build his house some winters and live by himself.

10. sEnanaitAnnik'At, "stone trail across on" (G). About a mile S of Horseshoe Bend.

11. Isgaikyoki (G). About 1-1/2 mi. S of Horseshoe Bend a small creek called Isgaikyokot enters the Eel from the W. The village with this name was situated on the N side of the mouth of this creek. It was the home of the father of the wife of Wylakki Tip.

12. IsgaidadAbbI˝lai (G). N of the creek mentioned in no. 11 but on higher ground away from the river.

13. ƚtAgtcEbi', "black oaks in" (G). About a mile N of Natoikot Cr. on a flat above the river.

14. sEnagatcEdA˝, "stones walk around place" (G). About 200 yds. N of no. 15.

15. sEƚsokyok'At, "stone blue large on" (G). About 1/2 mi. N of the mouth of Natoikot Cr. There was said to have been a pond here.

16. ƚtcicsEyEbi', "ashes rock shelter in" (G). This shelter was under a large rock which stood on the hillside a short distance downstream from no. 17. Two or three families used to spend the winter in it.

17. bantcEki, "war [ghosts] cry" (G). On the W side of the Eel a little more than a mile N of the mouth of North Fork and opposite the mouth of Cottonwood Cr. It was close to a fishing place that the tribelet shared with the bAskaiya tribelet.

18. tah-tēs-cho┤-tung, tah-tēs-cho┤-ting, tah-chis┤-ting (M). 1/2 mi. or more N of the mouth of North Fork on the W side of the main Eel.

taticcodA˝ (G). In a grove of oaks about 1/4 mi. downstream from the mouth of North Fork on the W side of the Eel.

19. ne┤-tahs, ning-ken-ne┤-tset (M). Ne┤-tahs is the name of the town on a rocky stretch of the river. The town ran for a mile or more S of the mouth of North Fork (Maj). Ning-ken-ne┤-tset was the name of the village which was at the fishing place opposite the mouth of North Fork and extending S. It was also called "fishtown." Tip's mother lived there (Tip).

nEtacbi', "land slide in" (G). About a mile S of the mouth of North Fork on the W side of the Eel. It was a noted fishing place. Goddard says: "There is no mention in the notes of a village at this point, but several Wailaki were spoken of at times as belonging to the nEtacbi'."

20. sEƚtcabi' (G). Nearly opposite the mouth of McDonald Cr. It was named for the large rock beneath which it stood.

21. tcoƚAttcik'At, "graveyard on" (G). A large village on the western side of the river a few hundred yards downstream from the mouth of djo˝kot.

[The stream that Goddard calls djo˝kot seems to be the one that appears on the modern maps as Cinch Cr.; that is the only one in the vicinity. On his map it is shown entering the Eel about a mile downstream from the mouth of Bell Springs Cr. but it is actually a tributary of Bell Springs Cr., joining that stream a scant hundred yards from its mouth. On the assumption that Cinch Cr. is, in fact, the stream that Goddard meant to indicate I have moved the village about a mile to the S.]

22. sa'kAntEƚdA˝, "beaver valley place" (G). About midway between the mouth of Blue Rock Cr. and Bell Springs Cr. on a fine large flat.

23. sEƚkaibi, "make a noise in the throat" (G). Opposite the mouth of Chamise Cr.

24. tcadEtokInnEdA˝ (G). Located only approximately—in Horseshoe Bend at the point where the river turns toward the NE.

25. k'AcsAndA˝, "alder stands place" (G). About a mile downstream from the point where the river turns W at Horseshoe Bend.

26. sEtcokInnEdA˝, "rock large its base place" (G). About 1/2 mi. downstream from the point where the river turns toward the W at Horseshoe Bend.

27. nEtcEdEtcA˝k'At, "ground rolling on" (G). A short distance W of the mouth of Copper Mine Cr. (Tunnel Cr.).

28. dAndaitcAmbi, "flint hole in" (G). On the downstream side of the mouth of Copper Mine Cr. (Tunnel Cr.).

29. taht-aht (M). On the E side of the Eel R. at Horseshoe Bend and opposite sĕ-tah┤-be. It was a big town (Tip).

kaitcIlI˝tadA˝, "Christmas berries among place" (G). There was a graveyard about 1/4 mi. N of the village and just beyond the graveyard was Copper Mine Cr.

30. to-chĕ┤-ting (M). A big village on the E side of the Eel R. at Horseshoe Bend (opposite sĕ-tah┤-be), only a short distance S of taht-aht (Tip). It was probably less than 1/4 mi. S of Island Mt. Station on the opposite side of the river.

kaslInkyodA˝. "spring large place" (G). On the E bank of the river about 300 yds. S of kaitcIlI˝tadA˝, or about 1/2 mi. S of Copper Mine Cr.

[The names of these two villages are not the same at all and since Goddard gives many villages in the near vicinity the chances are good that the names do not represent the same village.]

31. kaslInkyobi, "spring large in" (G). A rock shelter near Goddard's kaslInkyodA˝. A family used to spend the winter here. Captain Jim's father-in-law was left here to die after he had been wounded by the whites.