IN THE MORNING GLOW

IN THE

MORNING GLOW

SHORT STORIES

By

ROY ROLFE GILSON

AUTHOR OF

"Miss Primrose" "The Flower of Youth"

Etc. Etc.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Published by arrangement with Harper & Brothers

Copyright, 1902, by HARPER & BROTHERS.

All rights reserved.

Published October, 1902.

TO

MY WIFE

Contents

Illustrations

"'WHAT A BEAUTIFUL DREAM!'" . . . . . . Frontispiece

"WHEN GRANDFATHER WORE HIS WHITE VEST YOU WALKED LIKE OTHER FOLKS"

"YOU STOLE SOFTLY TO HIS SIDE"

"WATCHED HIM MAKE THE BLUE FRAGMENTS INTO THE BLUE PITCHER AGAIN"

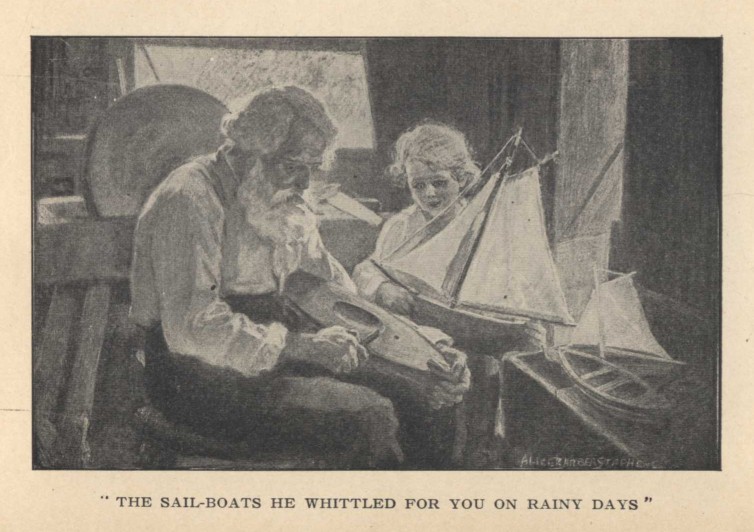

"THE SAIL-BOATS HE WHITTLED FOR YOU ON RAINY DAYS"

"YOU CLUNG TO HER APRON FOR SUPPORT IN YOUR MUTE AGONY"

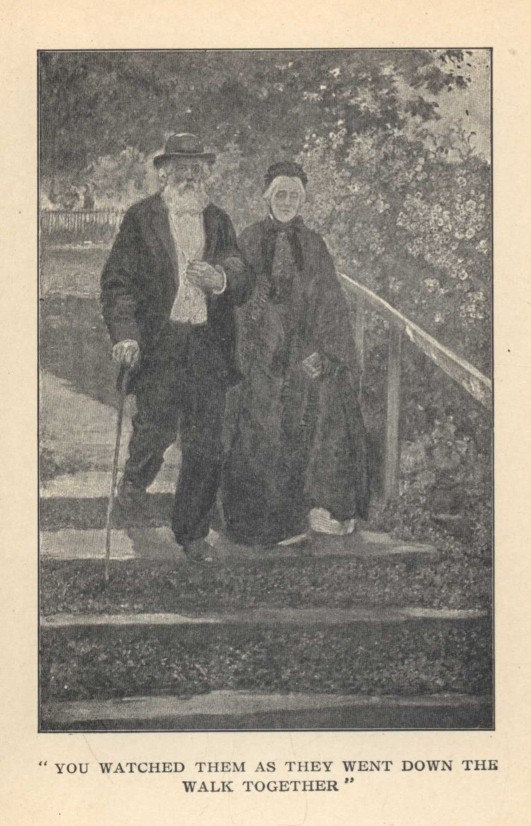

"YOU WATCHED THEM AS THEY WENT DOWN THE WALK TOGETHER"

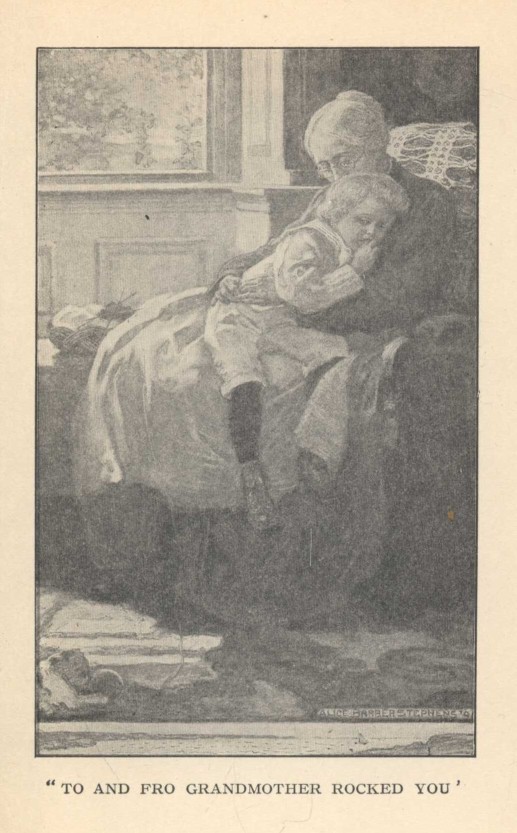

"TO AND FRO GRANDMOTHER ROCKED YOU"

"YOU SAID 'NOW I LAY ME' IN UNISON"

"MOTHER TUCKED YOU BOTH INTO BED AND KISSED YOU"

"THEY TOOK YOU AS FAR AS THE BEDROOM DOOR TO SEE HER"

"'BAD DREAM, WAS IT, LITTLE CHAP?'"

"'FATHER, WHAT DO YOU THINK WHEN YOU DON'T SAY ANYTHING, BUT JUST LOOK?'"

Grandfather

hen you gave Grandfather both your hands and put one foot against his knee and the other against his vest, you could walk right up to his white beard like a fly—but you had to hold tight. Sometimes your foot slipped on the knee, but the vest was wider and not so hard, so that when you were that far you were safe. And when you had both feet in the soft middle of the vest, and your body was stiff, and your face was looking right up at the ceiling, Grandfather groaned down deep inside, and that was the sign that your walk was ended. Then Grandfather crumpled you up in his arms. But on Sunday, when Grandfather wore his white vest, you walked like other folks.

hen you gave Grandfather both your hands and put one foot against his knee and the other against his vest, you could walk right up to his white beard like a fly—but you had to hold tight. Sometimes your foot slipped on the knee, but the vest was wider and not so hard, so that when you were that far you were safe. And when you had both feet in the soft middle of the vest, and your body was stiff, and your face was looking right up at the ceiling, Grandfather groaned down deep inside, and that was the sign that your walk was ended. Then Grandfather crumpled you up in his arms. But on Sunday, when Grandfather wore his white vest, you walked like other folks.

In the morning Grandfather sat in the sun by the wall—the stone wall at the back of the garden, where the golden-rod grew. Grandfather read the paper and smoked. When it was afternoon and Mother was taking her nap, Grandfather was around the corner of the house, on the porch, in the sun—always in the sun, for the sun followed Grandfather wherever he went, till he passed into the house at supper-time. Then the sun went down and it was night.

Grandfather walked with a cane; but even then, with all the three legs he boasted of, you could run the meadow to the big rock before Grandfather had gone half-way. Grandfather's pipe was corn-cob, and every week he had a new one, for the little brown juice that cuddled down in the bottom of the bowl, and wouldn't come out without a straw, wasn't good for folks, Grandfather said. Old Man Stubbs, who came across the road to see Grandfather, chewed his tobacco, yet the little brown juice did not hurt him at all, he said. Still it was not pleasant to kiss Old Man Stubbs, and Mother said that chewing tobacco was a filthy habit, and that only very old men ever did it nowadays, because lots of people used to do it when Grandfather and Old Man Stubbs were little boys. Probably, you thought, people did not kiss other folks so often then.

One morning Grandfather was reading by the wall, in the sun. You were on the ground, flat, peeping under the grass, and you were so still that a cricket came and teetered on a grass-stalk near at hand. Two red ants climbed your hat as it lay beside you, and a white worm swung itself from one grass-blade to another, like a monkey. The ground under the apple-trees was broken out with sun-spots. Bees were humming in the red clover. Butterflies lazily flapped their wings and sailed like little boats in a sea of goldenrod and Queen Anne's lace.

"Dee, dee-dee, dee-dee," you sang, and Mr. Cricket sneaked under a plantain leaf. You tracked him to his lair with your finger, and he scuttled away.

"Grandfather."

No reply.

"Grandfather."

Not a word. Then you looked. Grandfather's paper had slipped to the ground, and his glasses to his lap. He was fast asleep in the sunshine with his head upon his breast. You stole softly to his side With a long grass you tickled his ear. With a jump he awoke, and you tumbled, laughing, on the grass.

"Ain't you 'shamed?" cried Lizzie-in-the-kitchen, who was hanging out the clothes.

"Huh! Grandfather don't care."

Grandfather never cared. That is one of the things which made him Grandfather. If he had scolded he might have been Father, or even Uncle Ned—but he would not have been Grandfather. So when you spoiled his nap he only said, "H'm," deep in his beard, put on his glasses, and read his paper again.

When it was afternoon, and the sun followed Grandfather to the porch, and you were tired of playing House, or Hop-Toad, or Indian, or the Three Bears, it was only a step from Grandfather's foot to Grandfather's lap. When you sat back and curled your legs, your head lay in the hollow of Grandfather's shoulder, in the shadow of his white beard. Then Grandfather would say,

"Once upon a time there was a bear..."

Or, better still,

"Once, when I was a little boy..."

Or, best of all,

"When Grandfather went to the war..."

That was the story where Grandfather lay all day in the tall grass watching for Johnny Reb, and Johnny Reb was watching for Grandfather. When it came to the exciting part, you sat straight up to see Grandfather squint one eye and look along his outstretched arm, as though it were his gun, and say, "Bang!"

But Johnny Reb saw the tip of Grandfather's blue cap just peeping over the tops of the tall grass, and so he, too, went "Bang!"

And ever afterwards Grandfather walked with a cane.

"Did Johnny Reb have to walk with a cane, too, Grandfather?"

"Johnny Reb, he just lay in the tall grass, all doubled up, and says he, 'Gimme a chaw o' terbaccer afore I die.'"

"Did you give it to him, Grandfather?"

"He died 'fore I could get the plug out o' my pocket."

Then Mother would say:

"I wouldn't, Father—such stories to a child!"

Then Grandfather would smoke grimly, and would not tell you any more, and you would play Grandfather and Johnny Reb in the tall grass. Lizzie-in-the-kitchen would give you a piece of brown-bread for the chaw of tobacco, and when Johnny Reb died too soon you ate it yourself, to save it. You wondered what would have happened if Johnny Reb had not died too soon. Standing over Johnny Reb's prostrate but still animate form in the tall grass, with the brown-bread tobacco in your hand, you even contemplated playing that your adversary lived to tell the tale, but the awful thought that in that case you would have to give up the chaw (the brown-bread was fresh that day) kept you to the letter of Grandfather's story. Once only did you play that Johnny Reb lived—but the brown-bread was hard that day, and you were not hungry.

Grandfather wore the blue, and on his breast were the star and flag of the Grand Army. Every May he straightened his bent shoulders and marched to the music of fife and drum to the cemetery on the hill. So once a year there were tears in Grandfather's eyes. All the rest of that solemn May day he marched in the garden with his hands behind him, and a far-away look in his eyes, and once in a while his steps quickened as he hummed to himself,

"Tramp, tramp, tramp, the boys are marching."

And if it so happened that he told you the story of Johnny Reb that day, he would always have a new ending:

"Then we went into battle. The Rebs were on a tarnal big hill, and as we charged up the side, 'Boys,' says the Colonel—'boys, give 'em hell!' says he. And, sir, we just did, I tell you."

"Oh Father, Father—don't!—such language before the child!" Mother would cry, and that would be the end of the new end of Grandfather's story.

On a soap-box in Abe Jones's corner grocery, Grandfather argued politics with Old Man Stubbs and the rest of the boys.

"I've voted the straight Republican ticket all my life," he would say, proudly, when the fray was at its height, "and, by George! I'll not make a darned old fool o' myself by turning coat now. Pesky few Democrats ever I see who—"

Here Old Man Stubbs would rise from the cracker-barrel.

"If I understand you correctly, sir, you have called me a darned old fool."

"Not at all, Stubbs," Grandfather would reply, soothingly. "Not by a jugful. Now you're a Democrat—"

"And proud of it, sir," Old Man Stubbs would break in.

"You're a Democrat, Stubbs, and as such you are not responsible; but if I was to turn Democrat, Stubbs, I'd be a darned old fool."

And in the roar that followed, Old Man Stubbs would subside to the cracker-barrel and smoke furiously. Then Grandfather would say:

"Stubbs, do you remember old Mose Gray?" That was to clear the battle-field of the political carnage, so to speak—so that Old Man Stubbs would forget his grievance and walk home with Grandfather peaceably when the grocery closed for the night.

If it was winter-time, and the snowdrifts were too deep for grandfathers and little boys, you sat before the fireplace, Grandfather in his arm-chair, you flat on the rug, your face between your hands, gazing into the flames.

"Who was the greatest man that ever lived, Grandfather?"

"Jesus of Nazareth, boy."

"And who was the greatest soldier?"

"Ulysses S. Grant."

"And the next greatest?"

"George Washington."

"But Old Man Stubbs says Napoleon was the greatest soldier."

"Old Man Stubbs? Old Man Stubbs? What does he know about it, I'd like to know? He wasn't in the war. He's afraid of his own shadder. U. S. Grant was the greatest general that ever lived. I guess I know. I was there, wasn't I? Napoleon! Old Man Stubbs! Fiddlesticks!"

And Grandfather would sink back into his chair, smoking wrath and weed in his trembling corn-cob, and scowling at the blazing fagots and the curling hickory smoke. By-and-by—

"Who was the greatest woman that ever lived, Grandfather?"

"Your mother, boy."

"Oh, Father"—it was Mother's voice—"you forget."

"Forget nothing," cried Grandfather, fiercely. "Boy, your mother is the best woman that ever lived, and mind you remember it, too. Every boy's mother is the best woman that ever lived."

And when Grandfather leaned forward in his chair and waved his pipe, there was no denying Grandfather.

At night, after supper, when your clothes were in a little heap on the chair, and you had your nighty on, and you had said your prayers, Mother tucked you in bed and kissed you and called Grandfather. Then Grandfather came stumping up the stairs with his cane. Sitting on the edge of your bed, he sang to you,

"The wild gazelle with the silvery feetI'll give thee for a playmate sweet."

And after Grandfather went away the wild gazelle came and stood beside you, and put his cold little nose against your cheek, and licked your face with his tongue. It was rough at first, but by-and-by it got softer and softer, till you woke up and wanted a drink, and found beside you, in place of the wild gazelle, a white mother with a brimming cup in her hand. She covered you up when you were through, and kissed you, and then you went looking for the wild gazelle, and sometimes you found him; but sometimes, when you had just caught up to him and his silvery feet were shining like stars, he turned into Grandfather with his cane.

"Hi, sleepy-head! The dicky-birds are waitin' for you."

And then Grandfather would tickle you in the ribs, and help you on with your stockings, till it was time for him to sit by the wall in the sun.

When you were naughty, and Mother used the little brown switch that hung over the wood-shed door, Grandfather tramped up and down in the garden, and the harder you hollered, the harder Grandfather tramped. Once when you played the empty flower-pots were not flower-pots at all, but just cannon-balls, and you killed a million Indians with them, Mother showed you the pieces, and the switch descended, and the tears fell, and Grandfather tramped and tramped, and lost the garden-path completely, and stepped on the pansies. Then they shut you up in your own room up-stairs, and you cried till the hiccups came. You heard the dishes rattling on the dining-room table below. They would be eating supper soon, and at one end of the table in a silver dish there would be a chocolate cake, for Lizzie-in-the-kitchen had baked one that afternoon. You had seen it in the pantry window with your own eyes, while you fired the flower-pots. Now chocolate cake was your favorite, so you hated your bread-and-milk, and tasted and wailed defiantly. Now and then you listened to hear if they pitied and came to you, but they came not, and you moaned and sobbed in the twilight, and hoped you would die, to make them sorry. By-and-by, between the hiccups, you heard the door open softly. Then Grandfather's hand came through the crack with a piece of chocolate cake in it. You knew it was Grandfather's hand, because it was all knuckly. So you cried no more, and while the chocolate cake was stopping the hiccups, you heard Grandfather steal down the stairs, softly—but it did not sound like Grandfather at all, for you did not hear the stumping of his cane. Next morning, when you asked him about it, his vest shook, and just the tip of his tongue showed between his teeth, for that was the way it did when anything pleased him. And Grandfather said:

"You won't ever tell?"

"No, Grandfather."

"Sure as shootin'?"

"Yes."

"Well, then—" but Grandfather kept shaking so he could not tell.

"Oh, Grandfather! Why didn't the cane sound on the stairs?"

"Whisht, boy! I just wrapped my old bandanna handkerchief around the end."

But worse than that time was the awful morning when you broke the blue pitcher that came over in the Mayflower. An old family law said you should never even touch it, where it sat on the shelf by the clock, but the Old Nick said it wouldn't hurt if you looked inside—just once. You had been munching bread-and-butter, and your fingers were slippery, and that is how the pitcher came to fall. Grandfather found you sobbing over the pieces, and his face was white.

"Sonny, Sonny, what have you done?"

"I—I d-didn't mean to, Grandfather."

In trembling fingers Grandfather gathered up the blue fragments—all that was left of the family heirloom, emblem of Mother's ancestral pride.

"'Sh! Don't cry, Sonny. We'll make it all right again."

"M-Moth—Mother 'll whip me."

"'Sh, boy. No, she won't. We'll take it to the tinker. He'll make it all right again. Come."

And you and Grandfather slunk guiltily to the tinker and watched him make the blue fragments into the blue pitcher again, and then you carried it home, and as Grandfather set it back on the shelf you whispered:

"Grandfather!"

Grandfather bent his ear to you. Very softly you said it:

"Grandfather, the cracks don't show at all from here."

Grandfather nodded his head. Then he tramped up and down in the garden. He forgot to smoke. Crime weighed upon his soul.

"Boy," said he, sternly, stopping in his walk. "You must never be naughty again. Do you hear me?"

"I won't, Grandfather."

Grandfather resumed his tramping; then paused and turned to where you sat on the wheelbarrow.

"But if you ever are naughty again, you must go at once and tell Mother. Do you understand?"

"Yes, Grandfather."

Up and down Grandfather tramped moodily, his head bent, his hands clasped behind him—up and down between the verbenas and hollyhocks. He paused irresolutely—turned—turned again—and came back to you.

"Boy, Grandfather's just as bad and wicked as you are. He ought to have made you tell Mother about the pitcher first, and take it to the tinker afterwards. You must never keep anything from your mother again—never. Do you hear?"

"Yes, Grandfather," you whimpered, hanging your head.

"Come, boy."

You gave him your hand. Mother listened, wondering, while Grandfather spoke out bravely to the very end. You had been bad, but he had been worse, he confessed; and he asked to be punished for himself and you.

Mother did not even look at the cracked blue pitcher on the clock-shelf, but her eyes filled, and at the sight of her tears you flung yourself, sobbing, into her arms.

"Oh, Mother, don't whip Grandfather. Just whip me."

"It isn't the blue pitcher I care about," she said. "It's only to think that Grandfather and my little boy were afraid to tell me."

And at this she broke out crying with your wet cheek against her wet cheek, and her warm arms crushing you to her breast. And you cried, and Grandfather blew his nose, and Carlo barked and leaped to lick your face, until by-and-by, when Mother's white handkerchief and Grandfather's red one were quite damp, you and Mother smiled through your tears, and she said it did not matter, and Grandfather patted one of her hands while you kissed the other. And you and Grandfather said you would never be bad again. When you were good, or sick—dear Grandfather! It was not what he said, for only Mother could say the love-words. It was the things he did without saying much at all—the circus he took you to see, the lessons in A B C while he held the book for you in his hand, the sail-boats he whittled for you on rainy days—for Grandfather was a ship-carpenter before he was a grandfather—and the willow whistles he made for you, and the soldier swords. It was Grandfather who fished you from the brook. Grandfather saved you from Farmer Tompkins's cow—the black one which gave no milk. Grandfather snatched you from prowling dogs, and stinging bees, and bad boys and their wiles. That is what grandfathers are for, and so we love them and climb into their laps and beg for sail-boats and tales—and that is their reward.

One day—your birthday had just gone by and it was time to think of Thanksgiving—you walked with Grandfather in the fields. Between the stacked corn the yellow pumpkins lay, and they made you think of Thanksgiving pies. The leaves, red and gold, dropped of old age in the autumn stillness, and you gathered an armful for Mother.

"Why don't all the people die every year, Grandfather, like the leaves?"

"Everybody dies when his work's done, little boy. The leaf's work is done in the fall when the frost comes. It takes longer for a man to do his work, 'cause a man has more to do."

"When will your work be done, Grandfather?"

"It's almost done now, little boy."

"Oh no, Grandfather. There's lots for you to do. You said you'd make me a bob-sled, and a truly engine what goes, when I'm bigger; and when I get to be a grown-up man like Father, you are to come and make willow whistles for my little boys."

And you were right, for while the frost came again and again for the little leaves, Grandfather stayed on in the sun, and when he had made you the bob-sled he still lingered, for did he not have the truly engine to make for you, and the willow whistles for your own little boys?

Waking from a nap, you could not remember when you fell asleep. You wondered what hour it was. Was it morning? Was it afternoon? Dreamily you came down-stairs. Golden sunlight crossed the ivied porch and smiled at you through the open door. The dining-room table was set with blue china, and at every place was a dish of red, red strawberries. Then you knew it was almost supper-time. You were rested with sleep, gentle with dreams of play, happy at the thought of red berries in blue dishes with sugar and cream. You found Grandfather in the garden sitting in the sun. He was not reading or smoking; he was just waiting.

"Are you tired waiting for me, Grandfather?"

"No, little boy."

"I came as soon as I could, Grandfather."

The leaves did not move. The flowers were motionless. Grandfather sat quite still, his soft, white beard against your cheek, flushed with sleep. You nestled in his lap. And so you sat together, with the sun going down about you, till Mother came and called you to supper. Even now when you are grown, you remember, as though it were yesterday, the long nap and the golden light in the doorway, and the red berries on the table, and Grandfather waiting in the sun.

One day—it was not long afterwards—they took you to see Aunt Mary, on the train. When you came home again, Grandfather was not waiting for you.

"Where is Grandfather?"

"Grandfather isn't here any more, dearie. He has gone 'way up in the sky to see God and the angels."

"And won't he ever come back to our house?"

"No, dear; but if you are a good boy, you will go to see him some day."

"But, oh, Mother, what will Grandfather do when he goes to walk with the little boy angels? See—he's gone and forgot his cane!"

Grandmother

n the days when you went into the country to visit her, Grandmother was a gay, spry little lady with velvety cheeks and gold-rimmed spectacles, knitting reins for your hobby-horse, and spreading bread-and-butter and brown sugar for you in the hungry middle of the afternoon. For a bumped head there was nothing in the bottles to compare with the magic of her lips.

n the days when you went into the country to visit her, Grandmother was a gay, spry little lady with velvety cheeks and gold-rimmed spectacles, knitting reins for your hobby-horse, and spreading bread-and-butter and brown sugar for you in the hungry middle of the afternoon. For a bumped head there was nothing in the bottles to compare with the magic of her lips.

"And what did the floor do to my poor little lamb? See! Grandmother will make the place well again." And when she had kissed it three times, lo! you knew that you were hungry, and on the door-sill of Grandmother's pantry you shed a final tear.

When you arrived for a visit, and Grandmother had taken off your cap and coat as you sat in her lap, you would say, softly, "Grandmother." Then she would know that you wanted to whisper, and she would lower her ear till it was even with your lips. Through the hollow of your two hands you said it:

"I think I would like some sugar pie now, Grandmother."

And then she would laugh till the tears came, and wipe her spectacles, for that was just what she had been waiting for you to say all the time, and if you had not said it—but, of course, that was impossible. Always, on the day before you came, she made two little sugar pies in two little round tins with crinkled edges. One was for you, and the other was for Lizbeth.

After you had eaten your pies you chased the rooster till he dropped you a white tail-feather in token of surrender, and just tucking the feather into your cap made you an Indian. Grandmother stood at the window and watched you while you scalped the sunflowers. The Indians and tigers at Grandmother's were wilder than those in Our Yard at home.

Being an Indian made you think of tents, and then you remembered Grandmother's old plaid shawl. She never wore it now, for she had a new one, but she kept it for you in the closet beneath the stairs. While you were gone, it hung in the dark alone, dejected, waiting for you to come back and play. When you came, at last, and dragged it forth, it clung to you warmly, and did everything you said: stretched its frayed length from chair to chair and became a tent for you; swelled proudly in the summer gale till your boat scudded through the surf of waving grass, and you anchored safely, to fish with string and pin, by the Isles of the Red Geraniums.

"The pirates are coming," you cried to Lizbeth, scanning the horizon of picket fence.

"The pirates are coming," she repeated, dutifully.

"And now we must haul up the anchor," you commanded, dragging in the stone. Lizbeth was in terror. "Oh, my poor dolly!" she cried, hushing it in her arms. Gallantly the old plaid shawl caught the breeze; and as it filled, your boat leaped forward through—

"Harry! Lizbeth! Come and be washed for dinner!"

Grandmother's voice came out to you across the waters. You hesitated. The pirate ship was close behind. You could see the cutlasses flashing in the sun.

"More sugar pies," sang the Grandmother siren on the rocks of the front porch, and at those melting words the pirate ship was a mere speck on the horizon. Seizing Lizbeth by the hand, you ran boldly across the sea.

By the white bowl Grandmother took your chin in one hand and lifted your face.

"My, what a dirty boy!"

With the rough wet rag she mopped the dirt away—grime of your long sea-voyage—while you squinted your eyes and pursed up your lips to keep out the soap. You clung to her apron for support in your mute agony.

"Grand—" you managed to sputter ere the wet rag smothered you. Warily you waited till the cloth went higher, to your puckered eyes. Then, "Grand-m-m—" But that was all, for with a trail of suds the rag swept down again, and as the half-word slipped out, the soap slipped in. So Grandmother dug and dug till she came to the pink stratum of your cheeks, and then it was wipe, wipe, wipe, till the stratum shone. Then it was your hands' turn, while Grandmother listened to your belated tale, and last of all she kissed you above and gave you a little spank below, and you were done.

All through dinner your mind was on the table—not on the middle of it, where the meat was, but on the end of it.

"Harry, why don't you eat your bread?"

"Why, I don't feel for bread, Grandmother," you explained, looking at the end of the table. "I just feel for pie."

It was hard when you were back home again, for there it was mostly bread, and no sugar pies at all, and very little cake.

"Grandmother lets me have two pieces," you would urge to Mother, but the argument was of no avail. Two pieces, she said, were not good for little boys.

"Then why does Grandmother let me have them?" you would demand, sullenly, kicking the table leg; but Mother could not hear you unless you kicked hard, and then it was naughty boys, not Grandmothers, that she talked about. And if that happened which sometimes does to naughty little boys—

"Grandmother don't hurt at all when she spanks," you said.

So there were wrathful moments when you wished you might live always with Grandmother. It was so easy to be good at her house—so easy, that is, to get two pieces of cake. And when God made little boys, you thought, He must have made Grandmothers to bake sugar pies for them.

"Suppose you were a little boy like me, Grandmother?" you once said to her.

"That would be fine," she admitted; "but suppose you were a little grandmother like me?"

"Well," you replied, with candor, "I think I would rather be like Grandfather, 'cause he was a soldier, and fought Johnny Reb."

"And if you were a grandfather," Grandmother asked, "what would you do?"

"Why, if I were a grandfather," you said—"why—"

"Well, what would you do?"

"Why, if I were a grandfather," you said, "I should want you to come and be a grandmother with me." And Grandmother kissed you for that.

"But I like you best as a little boy," she said. "Once Grandmother had a little boy just like you, and he used to climb into her lap and put his arms around her. Oh, he was a beautiful little boy, and sometimes Grandmother gets very lonesome without him—till you come, and then it's like having him back again. For you've got his blue eyes and his brown hair and his sweet little ways, and Grandmother loves you—once for yourself and once for him."

"But where is the little boy now, Grandmother?"

"He's a man now, darling. He's your own father."

Every Sunday, Grandmother went to church. After breakfast there was a flurry of dressing, with an opening and shutting of doors up-stairs, and Grandfather would be down-stairs in the kitchen, blacking his Sunday boots. On Sunday his beard looked whiter than on other days, but that was because he seemed so much blacker everywhere else. He creaked out to the stable and hitched Peggy to the buggy and led them around to the front gate. Then he would snap his big gold watch and go to the bottom of the stairs and say:

"Maria! Come! It's ten o'clock."

Grandmother's door would open a slender crack—"Yes, John"—and Grandfather would creak up and down in his Sunday boots, up and down, waiting, till there was a rustling on the stairs and Grandmother came down to him in a glory of black silk. There was a little frill of white about her neck, fastened with her gold brooch, and above that her gentle Sabbath face. Her face took on a new light when Sunday came, and she never seemed so near, somehow, as on other days. There was a look in her eyes that did not speak of sugar pies or play. There was a little pressure of the thin lips and a silence, as though she had no time for fairy-tales or lullabies. When she set her little black bonnet on her gray hair and lifted up her chin to tie the ribbon strings beneath, you stopped your game to watch, wondering at her awesomeness; and when in her black-gloved fingers she clasped her worn Bible and stooped and kissed you good-bye, you never thought of putting your arms around her. She was too wonderful—this little Sabbath Grandmother—for that.

Through the window you watched them as they went down the walk together to the front gate, Grandmother and Grandfather, the tips of her gloved fingers laid in the hollow of his arm. Solemn was the steady stumping of his cane. Solemn was the day. Even the roosters knew it was Sunday, somehow, and crowed dismally; and the bells—the church-bells tolling through the quiet air—made you lonesome and cross with Lizbeth. Your collar was very stiff, and your Sunday trousers were very tight, and there was nothing to do, and you were dreary.

After dinner Grandfather went to sleep on the sofa, with a newspaper over his face. Then Grandmother took you up into her black silk lap and read you Bible stories and taught you the Twenty-third Psalm and the golden text. And every one of the golden texts meant the same thing—that little boys should be very good and do as they are told.

Grandmother's Sunday lap was not so fine as her other ones to lie in. Her Monday lap, for instance, was soft and gray, and there were no texts to disturb your reverie. Then Grandmother would stop her knitting to pinch your cheek and say, "You don't love Grandmother."

"Yes, I do."

"How much?"

"More'n tonguecantell. What is a tonguecantell, Grandmother?"

And while she was telling you she would be poking the tip of her finger into the soft of your jacket, so that you doubled up suddenly with your knees to your chin; and while you guarded your ribs a funny spider would crawl down the back of your neck; and when you chased the spider out of your collar it would suddenly creep under your chin, or there would be a panic in the ribs again. By that time you were nothing but wriggles and giggles and little cries.

"Don't, Grandmother; you tickle." And Grandmother would pause, breathless as yourself, and say, "Oh, my!"

"Now you must do it some more, Grandmother," you would urge, but she would shake her head at you and go back to her knitting again.

"Grandmother's tired," she would say.

You were tired, too, so you lay with your head on her shoulder, sucking your thumb. To and fro Grandmother rocked you, to and fro, while the kitten played with the ball of yarn on the floor. The afternoon sunshine fell warmly through the open window. Bees and butterflies hovered in the honeysuckles. Birds were singing. Your mind went a-wandering—out through the yard and the front gate and across the road. On it went past the Taylors' big dog and up by Aunty Green's, where the crullers lived, all brown and crusty, in the high stone crock. It scrambled down by the brook where the little green frogs were hopping into the water, leaving behind them trembling rings that grew wider and wider and wider, till pretty soon they were the ocean. That was a big thought, and you roused yourself.

"How big is the ocean, Grandmother?"

"As big—oh, as big as all out-doors."

Your mind waded out into the ocean till the water was up to its knees. Then it scrambled back again and lay in the warm sand and looked up at the sky. And the sand rocked to and fro, to and fro, as your mind lay there, all curled up and warm, by the ocean, watching the butterflies in the honeysuckles and the crullers in the crock. And all the people were singing ... all the people in the world, almost ... and the little green frogs.... "Bye—bye, bye—bye," they were singing, in time to the rocking of the sand ... "Bye—bye" ... "Bye" ... "Bye" ...

And when you awoke you were on the sofa, all covered up with Grandmother's shawl.

So you liked the gay week-day Grandmother best, with her soft lap and her lullabies. Grandfather must have liked her best too, you thought, for when he went away forever and forgot his cane, it was the Sunday Grandmother he left behind—a little, gray Grandmother sitting by the window and gazing silently through the panes.

What she saw there you never knew—but it was not the trees, or the distant hills, or the people passing in the road.

While Aunt Jane Played

unt Jane played the piano in the parlor. You could play, too—"Peter, Peter, Punkin-eater," with your forefinger, Aunt Jane holding it in her hand so that you would strike the right notes. But when Aunt Jane played she used both hands. Sometimes the music was so fast and stirring that it made you dance, or romp, or sing, or play that you were not a little boy at all, but a soldier like Grandfather or George Washington; and sometimes the music was so soft and beautiful that you wanted to be a prince in a fairy tale; and then again it was so slow and grim that you wished it were not Sunday, for the Sunday tunes, like your tight, black, Sunday shoes, had all their buttons on, and so were not comfy or made for fun. You could not march to them, or fight to them, or be a grown-up man to them. Somehow they always reminded you that you were only a pouting, naughty little boy.

unt Jane played the piano in the parlor. You could play, too—"Peter, Peter, Punkin-eater," with your forefinger, Aunt Jane holding it in her hand so that you would strike the right notes. But when Aunt Jane played she used both hands. Sometimes the music was so fast and stirring that it made you dance, or romp, or sing, or play that you were not a little boy at all, but a soldier like Grandfather or George Washington; and sometimes the music was so soft and beautiful that you wanted to be a prince in a fairy tale; and then again it was so slow and grim that you wished it were not Sunday, for the Sunday tunes, like your tight, black, Sunday shoes, had all their buttons on, and so were not comfy or made for fun. You could not march to them, or fight to them, or be a grown-up man to them. Somehow they always reminded you that you were only a pouting, naughty little boy.

The sound of the piano came out to you as you lingered by the table where Lizzie-in-the-kitchen was making pies. You ran into the parlor and sat on a hassock by Aunt Jane, watching her as she played. It was not a fast piece that day, nor yet a slow one, but just in-between, so that as you sat by the piano you wondered if the snow and sloppy little puddles would ever go and leave Our Yard green again. Even with rubber boots now Mother made you keep the paths, and mostly you had to stay in the house. Through the window you could see the maple boughs still bare, but between them the sky was warm and blue. Pretty soon the leaves would be coming, hiding the sky.

"Auntie."

"Yes," though she did not stop playing.

"Where do the leaves come from?"

"From the little buds on the twigs, dearie."

"But how do they know when it's time to come, Auntie Jane? 'Cause if they came too soon, they might catch cold and die."

"Well, the sun tells them when."

"How does the sun tell them, Auntie?"

"Why, he makes the trees all warm, and when the buds feel it, out they come."

"Oh."

Your eyes were very wide. They were always wide when you wondered; and sometimes when you were not wondering at all, just hearing Aunt Jane play would make you, and then your eyes would grow bigger and bigger as you sat on the hassock by the piano, looking at the maple boughs and hearing the music and being a little boy.

It was a beautiful piece that Aunt Jane was playing that March morning. The sun came and shone on the maple boughs.

"And now the sun is telling the little buds," you said to yourself in time to Aunt Jane's music, but so softly that she did not hear.

"And now the little buds are saying 'All right,'" you whispered, more softly still, for the bigger your eyes got, the smaller, always, was your voice.

A little song-sparrow came and teetered on a twig.

"Oh, Auntie, see! The birdie's come, too, to tell the buds, I guess."

Aunt Jane turned her head and smiled at the sparrow, but she did not stop playing. Your heart was beating in time to the music, as you sat on the hassock by the piano, watching the bird and the sun. The sparrow danced like Aunt Jane's fingers, and put up his little open bill. He was singing, though you could not hear.

"But, Auntie."

"Yes."

"Who told the little bird?"

"God told the little bird, dearie—away down South where the oranges and roses grow in the winter, and there isn't any snow. And the little bird flew up here to Ourtown to build his nest and sing in our maple-tree."

Your eyes were so wide now that you had no voice at all. You just sat there on the hassock while Aunt Jane played.

Away down South ... away down South, singing in an orange-tree, you saw the little bird ... but now he stopped to listen with his head on one side, and his bright eye shining, while the warm wind rustled in the leaves ... God was telling him ... So the little bird spread his wings and flew ... away up in the blue sky, above the trees, above the steeples, over the hills and running brooks ... miles and miles and miles ... till he came to Our Yard, in the sun.

"And here he is now," you ended aloud your little story, for you had found your voice again.

"Who is here, dearie?" asked Aunt Jane, still playing.

"Why, the little bird," you said.

The sparrow flew away. The sun came through the window to where you sat on the hassock, by the piano. It warmed your knees and told you—what it told the buds, what God told the little bird in the orange-tree. Like the little bird you could stay no longer. You ran out-of-doors into the soft, sweet wind and the morning.

Aunt Jane gave the keys a last caress. Grandmother turned in her chair by the sitting-room window.

"What were you playing, Janey?"

"Mendelssohn's 'Spring Song,' Mother."

The little gray Grandmother looked out-of-doors again to where you played, singing, in the sun.

"Isn't it beautiful?" she murmured.

You waved your hand to her and laughed, and she nodded back at you, smiling at your fun.

"Bless his heart, he's playing the music, too," she said.

Little Sister

n the daytime she played with you, and believed all you said, and was always ready to cry. At night she slept with you and the four dolls. She was your little sister, Lizbeth.

n the daytime she played with you, and believed all you said, and was always ready to cry. At night she slept with you and the four dolls. She was your little sister, Lizbeth.

"Whose little girl are you?" they would ask her. If she were sitting in Father's lap, she would doubtless reply—

"Father's little girl."

But—

"Oh, Lizbeth!" Mother would cry.

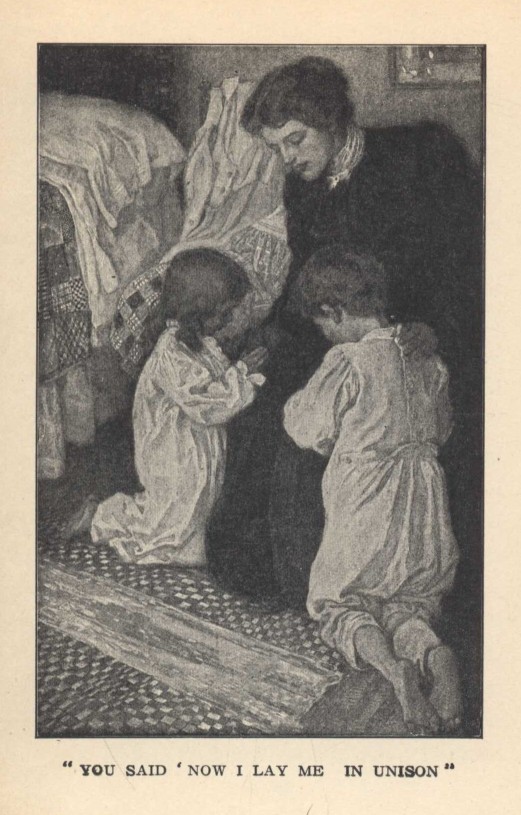

"—and Mother's," Lizbeth would add, to keep peace in the family. Though she never mentioned you at such times, she told you privately that she would marry you when you grew to be a man, and publicly she remembered you in her prayers. Kneeling down at Mother's knee, you and Lizbeth, in your little white nighties, before you went to bed, you said "Now I lay me" in unison, and ended with blessing every one, only at the very end you said:

"—and God bless Captain Jinks," for even a wooden soldier needed God in those long, dark nights of childhood, while Lizbeth said:

"—and God bless all my dollies, and send my Sally doll a new leg."

But though God sent three new legs in turn, Sally was always losing them, so that finally Lizbeth confided in Mother:

"Pretty soon God 'll be tired of sending Sally new legs, I guess. You speak to Him next time, Mother, 'cause I'm 'shamed to any more."

And when Mother asked Him, He sent a new Sally instead of a new leg. It would be cheaper, Mother told Father, in the long-run.

In the diplomatic precedence of Lizbeth's prayers, Father and Mother were blessed first, and you came between "Grandfather and Grandmother" and "God bless my dollies." Thus was your family rank established for all time by a little girl in a white night-gown. You were a little lower than your elders, it is true, but you were higher than the legless Sally or the waxen blonde.

When Lizbeth and you were good, you loved each other, and when you were bad, both of you at the same time, you loved each other too, very dearly. But sometimes it happened that Lizbeth was good and you were bad, and then she only loved Mother, and ran and told tales on you. And you—well, you did not love anybody at all.

When your insides said it would be a long time before dinner, and your mouth watered, and you stood on a chair by the pantry shelf with your hand in a brown jar, and when Lizbeth found you there, you could tell by just looking at her face that she was very good that day, and that she loved Mother better than she did you. So you knew without even thinking about it that you were very bad, and you did not love anybody at all, and your heart quaked within you at Lizbeth's sanctity. But there was always a last resort.

"Lizbeth, if you tell"—you mumbled awfully, pointing at her an uncanny forefinger dripping preserves—"if you tell, a great big black Gummy-gum 'll get you when it's dark, and he'll pick out your eyes and gnaw your ears off, and he'll keep one paw over your mouth, so you can't holler, and when the blood comes—"

Lizbeth quailed before you. She began to cry.

"You won't tell, will you?" you demanded, fiercely, making eyes like a Gummy-gum and showing your white teeth.

"No—o—o," wailed Lizbeth.

"Well, stop crying, then," you commanded, sucking your syrupy fingers. "If you cry, the Gummy-gum 'll come and get you now."

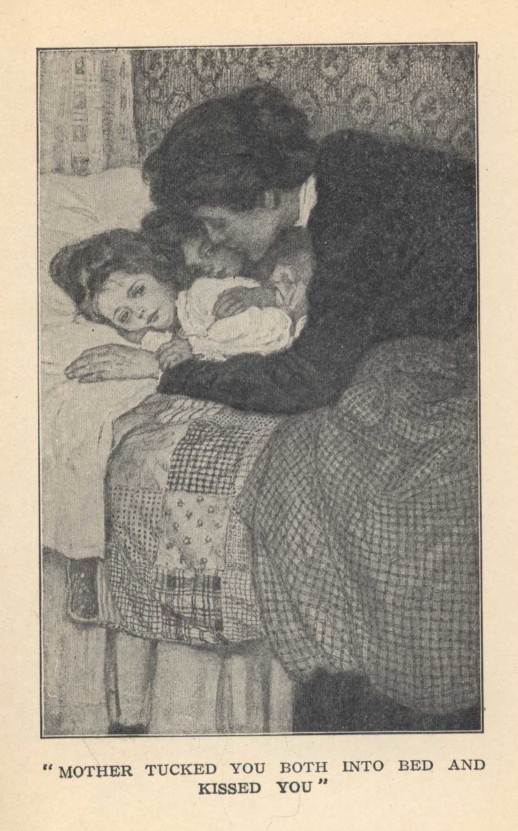

Lizbeth looked fearfully over her shoulder and stopped. By that time your fingers were all sucked, and the cover was back on the jar, and you were saved. But that night, when Mother and Father came home, you watched Lizbeth, and lest she should forget, you made the eyes of a Gummy-gum, when no one but Lizbeth saw. Mother tucked you both into bed and kissed you and put out the light. Then Lizbeth whimpered.

"Why, Lizbeth," said Mother from the dark.

Quick as a flash you snuggled up to Lizbeth's side. "The Gummy-gum 'll get you if you don't stop," you whispered, warningly—but with one dismal wail Lizbeth was out of bed and in Mother's arms. Then you knew all was over. Desperately you awaited retribution, humming a little song, and so it was to the tune of "I want to be an angel" that you heard Lizbeth sob out her awful tale:

"Harry ... he ... he said the Gummy-gum 'd get me ... if I told about the p'serves."

And it was you the Gummy-gum got that time, and your blood, you thought, almost came.

But other nights when you went to bed—nights after days when you had both been good and loved each other—it was fine to lie there in the dark with Lizbeth, playing Make-Believe before you fell asleep.

"I tell you," you said, putting up your foot so that the covers rose upon it, making a little tent—"I tell you; let's be Indians."

"Let's," said Lizbeth.

"And this is our little tent, and there's bears outside what 'll eat you up if you don't look out."

Lizbeth shivered and drew her knees up to her chin, so that she was nothing but a little warm roll under the wigwam.

"And now the bears are coming—wow! wow! wow!"

And as the great hungry beasts pushed their snouts under the canvas and growled and gnashed their teeth, Lizbeth, little squaw, squealed with terror, and seized you as you lay there helpless in your triple rôle of tent and bears and Indian brave; seized you in the ticklish ribs so that the wigwam came tumbling about your ears, and the Indian brave rolled and shrieked with laughter, and the brute bears fled to their mountain caves.

"Children!"

"W-what?"

"Stop that noise and go right to sleep. Do you hear me?"

Was it not the voice of the mamma bear? Stealthily you crept under the fallen canvas, which had grown smaller, somehow, in the mêlée, so that when you pulled it up to your chin and tucked it in around you, Lizbeth was out in the cold; and when Lizbeth tucked herself in, then you were shivering. But by-and-by you huddled close in the twisted sheets and talked low beneath the edge of the coverlet, so that no one heard you—not even the Gummy-gum, who spent his nights on the back stairs.

"Does the Gummy-gum eat little folks while they're asleep?" asked Lizbeth, with a precautionary snuggle-up.

"No; 'cause the Gummy-gum is afraid of the little black gnomes what live in the pillows."

"Well, if the little black gnomes live in the pillows, why can't you feel them then?"

"'Cause, now, they're so teenty-weenty and so soft."

"And can't you ever see them at all?"

"No; 'cause they don't come out till you're asleep."

"Oh ... Well, Harry—now—if a Gummy-gum had a head like a horse, and a tail like a cow, and a bill like a duck, what?"

"Why—why, he wouldn't, 'cause he isn't."

"Oh ... Well, is the Gummy-gum just afraid of the little gnomes, and that's all?"

"Um-hm; 'cause the little gnomes have little knives, all sharp and shiny, what they got on the Christmas-tree."

"Our Christmas-tree?"

"No; the little gnomes's Christmas-tree."

"The little gnomes's Christmas-tree?"

"Um-hm."

"Why?"

"'Cause ... why, there ain't any why ... just Christmas-tree."

"Just ... just Christmas-tree?"

"Um."

"Why ... I thought ... I ..."

And you and Lizbeth never felt Mother smooth out the covers at all, though she lifted you up to straighten them; and so you slept, spoon-fashion, warm as toast, with the little black gnomes watching in the pillows, and the Gummy-gum, hungry but afraid, in the dark of the back stairs.

The pear-tree on the edge of the enchanted garden, green with summer and tremulous with breeze, sheltered a little girl and her dolls. On the cool turf she sat alone, preoccupied, her dress starched and white like the frill of a valentine, her fat little legs straight out before her, her bright little curls straight down behind, her lips parted, her eyes gentle with a dream of motherhood—Mamma Lizbeth crooning lullabies to her four children cradled in the soft grass.

"I'll tell you just one more story," she was saying, "just one, and that's all, and then you children must go to sleep. Sally, lie still! Ain't you 'shamed, kicking all the covers off and catching cold? Naughty girl. Now you must listen. Well ... Once upon a time there was a fairy what lived in a rose, and she had beautiful wings—oh, all colors—and she could go wherever she wanted to without anybody ever seeing her, 'cause she was iwisible, which is when you can't see anybody at all. Well, one day the fairy saw a little girl carrying her father's dinner, and she turned herself into an old witch and said to the little girl, 'Come to me, pretty one, and I will give thee a stick of peppermint candy.' Now the little girl, she just loved candy, and peppermint was her favorite, but she was a good little girl and minded her mother most dut'fly, and never told any lies or anything; so she courtesied to the old witch and said, 'Thank you kindly, but I must hurry with my father's dinner, or he will be hungry waiting.' And what do you think? Just then the old witch turned into the beautiful fairy again, and she kissed the little girl, and gave her a whole bag of peppermint candy, and a doll what talked, and a velocipede for her little brother. And what does this story teach us, children? ... Yes. That's right. It teaches us to be good little boys and girls and mind our parents. And that's all."

The dolls fell asleep. Lizbeth whispered lest they should awake, and tiptoed through the grass. A blue-jay called harshly from a neighboring tree. Lizbeth frowned and glanced anxiously at the grassy trundle-bed. "'Sh!" she said, warningly, her finger on her lip, whenever you came near.

Suddenly there was a rustle in the leaves above, and out of their greenness a little pear dropped to the grass at Lizbeth's feet.

"It's mine," you cried, reaching out your hand.

"No—o," screamed Lizbeth. "It's for my dollies' breakfast," and she hugged the stunted, speckled fruit to her bosom so tightly that its brown, soft side was crushed in her hands. You tried to snatch it from her, but she struck you with her little clinched fist.

"No—o," she cried again. "It's my dollies' pear." Her lip quivered. Tears sprang into her eyes. You straightened yourself.

"All right," you muttered, fiercely. "All right for you. I'll run away, I will, and I'll never come back—never!"

You climbed the stone wall.

"No," cried Lizbeth.

"I'll never come back," you called, defiantly, as you stood on the top.

"No," Lizbeth screamed, scrambling to her feet and turning to you a face wet with tears and white with terror.

"Never, never!" was your farewell to her as you jumped. Deaf to the pitiful wail behind you, you ran out across the meadow, muttering to yourself your fateful, parting cry.

Lizbeth looked for a moment at the wall where you had stood. Then she ran sobbing after you, around through the gate, for the wall was too high for her, and out into the field, where to her blurred vision you were only a distant figure now, never, never to return.

"Harry!" she screamed, and the wind blew her cry to you across the meadow, but you ran on, unheeding. She struggled after you. The daisies brushed her skirt. Creeping vines caught at her little shoes and she fell. Scratched by briers, she scrambled to her feet again and stumbled on, blind with tears, crying ever "Harry, Harry!" but so faintly now in her sobs and breathlessness that you did not hear. At the top of a weary, weary slope she sank helpless and heartbroken in the grass, a little huddle of curls and pinafore, so that your conscience smote you as you stood waiting, half hidden by the hedge.

"Don't be a cry-baby. I was only fooling," you said, and at the sound of your voice Lizbeth lifted her face from the grasses and put out her arms to you with a cry. In one hand was the little pear.

"Oh, I don't want the old thing," you cried, throwing yourself beside her on the turf. Smiling again through her tears, Lizbeth reached out a little hand scratched by briers, and patted your cheek.

"Harry," she said, "you can have all my animal crackers for your m'nagerie, if you want to, and my little brown donkey; and I'll play horse with you any time you want me to, Harry, I will."

So, after all, you did not run away, and you and Lizbeth went home at last across the meadow, hand in hand. Behind you, hidden and forgotten in the red clover, lay your quarrel and the little pear.

When Lizbeth loved you, there were stars in her brown eyes; when you looked more closely, so that you were very near their shining, you saw in their round, black pupils, smiling back at you, the face of a little boy; and then in your own eyes, Lizbeth, holding your cheeks between her hands, found the face of a little girl.

"Why, it's me!" she cried.

And when you looked again into Lizbeth's eyes, you saw yourself; and "Oh, Mother," you said afterwards, for you had thought deeply, "I think it's the good Harry that's in Lizbeth's eyes, 'cause when I look at him, he's always smiling." That was as far as you thought about it then; but once, long afterwards, it came to you that little boys never find their pictures in a sister's eyes unless they are good, and love her, and hold her cheeks between their hands.

Lizbeth's cheeks were softer than yours, and when she played horse, or the day was windy, so that the grass rippled and the trees sang, or when it was tub-day with soap and towels up-stairs, her cheeks were pink as the roses in Mother's garden. That is how you came to tell Mother a great secret, one evening in summer, as you sat with her and Lizbeth on the front steps watching the sun go down.

"I guess it's tub-day in the sky, Mother."

"Tub-day?"

"Why, yes. All the little clouds have been having their bath, I think, 'cause they're all pink and shiny, like Lizbeth."

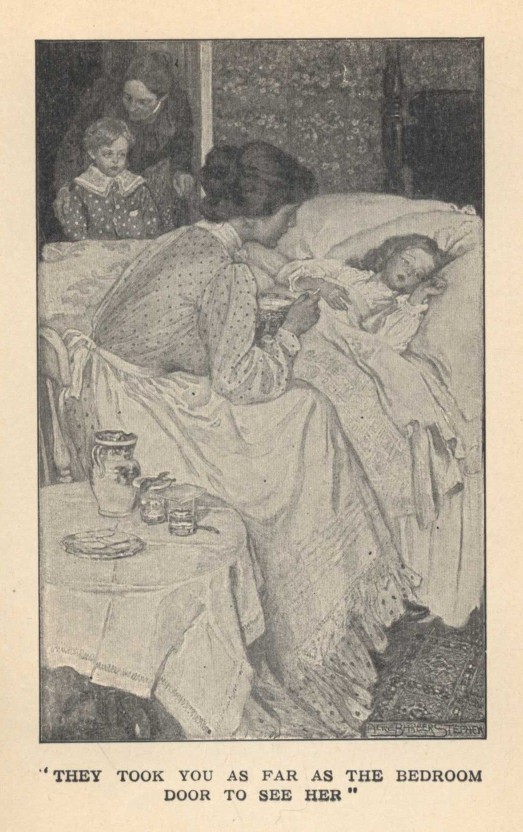

But once Lizbeth's cheeks were white, and she stayed in bed every day, and you played by yourself. Twice a day they took you as far as the bedroom door to see her.

"H'lo," you said, as you peeked.

"H'lo," she whispered back, very softly, for she was almost asleep, and she did not even smile at you, and before you could tell her what the Pussy-cat did they took you away—but not till you had seen the two glasses on the table with the silver spoon on top.

There was no noise in the days then. Even the trees stopped singing, and the wind walked on tiptoe and whispered into people's ears, like you.

"Is it to-day Lizbeth comes down-stairs?" you asked every morning.

"Do you think Lizbeth will play with me to-morrow?" you asked every night. Night came a long time after morning in the days when Lizbeth could not play.

"Oh, dear, I don't think I feel very well," you told Mother. Tears spilled out of your eyes and rolled down your cheeks. Mother felt your brow and looked at your tongue.

"I know what's the matter with my little boy," she said, and kissed you; but she did not put you to bed.

One day, when no one was near, you peeked and saw Lizbeth. She was alone and very little and very white.

"H'lo," you said.

"H'lo," she whispered back, and smiled at you, and when she smiled you could not wait any longer. You went in very softly and kissed her where she lay and gave her a little hug. She patted your cheek.

"I'd like my dollies," she whispered. You brought them to her, all four—the two china ones and the rag brunette and the waxen blonde.

"Dollies are sick," she said. "They 'most died, I guess. Play you're sick, too."

Mother found you there—Lizbeth and you and the four dolls, side by side on the bed, all in a little sick row. And from the very moment that you kissed Lizbeth and gave her the little hug, she grew better, so that by-and-by the wind blew louder and the trees sang lustily, and all Our Yard was bright with flowers and sun and voices and play, for you and Lizbeth and the four dolls were well again.

Our Yard

he breadth of Our Yard used to be from the beehives to the red geraniums. When the beehives were New York, the geraniums were Japan, so the distance is easy to calculate. The apple-tree Alps overshadowed New York then, which seems strange now, but geography is not what it used to be. In the lapse of years the Manhattan hives have crumbled in the Alpine shade, an earthquake of garden spade has wiped Japan from the map, and where the scarlet islands lay in the sun there are green billows now, and other little boys in the grass, at play.

he breadth of Our Yard used to be from the beehives to the red geraniums. When the beehives were New York, the geraniums were Japan, so the distance is easy to calculate. The apple-tree Alps overshadowed New York then, which seems strange now, but geography is not what it used to be. In the lapse of years the Manhattan hives have crumbled in the Alpine shade, an earthquake of garden spade has wiped Japan from the map, and where the scarlet islands lay in the sun there are green billows now, and other little boys in the grass, at play.

In the old days when you sailed away on the front gate, which swung and creaked through storms, to the other side of the sea, you could just descry through a fog of foliage the rocky shores of the back-yard fence, washed by a surf of golden-rod. If you moored your ship—for an unlatched gate meant prowling dogs in the garden, and Mother was cross at that—if you anchored your gate-craft dutifully to become a soldier, you could march to the back fence, but it was a long journey. Starting, a drummer-boy, you could never foretell your end, for the future was vague, even with the fence in view, and your cocked hat on your curls, and your drumsticks in your hand. Lizbeth and the dolls might halt you at the front steps and muster you out of service to become a doctor with Grandmother's spectacles and Grandfather's cane. And if the dolls were well that day, with normal pulses and unflushed cheeks, and you marched by with martial melody, there was your stalled hobby-horse on the side porch, neighing to you for clover hay; and stopping to feed him meant desertion from the ranks, to become a farmer, tilling the soil and bartering acorn eggs and clean sand butter on market-day. And even though you marched untempted by bucolic joys, there lay in wait for you the kitchen door, breathing a scent of crullers, or gingerbread, or apple-pies, or leading your feet astray to the unscraped frosting-bowl or the remnant cookies burned on one side, and so not good for supper, but fine for weary drummer-boys. So whether you reached the fence that day was a question for you and the day and the sirens that beckoned to you along your play.

Across the clover prairie the trellis mountains reared their vine-clad heights. Through their morning-glories ran a little pass, which led to the enchanted garden on the other side, but the pass was so narrow and overhung with vines that when Grandfather was a pack-horse and carried you through on his back, your outstretched feet would catch on the trellis sides. Then the pack-horse would pick his way cautiously and you would dig your heels into his sides and hold fast, and so you got through. Once inside the garden, oh, wonder of pansies and hollyhocks and bachelor's-buttons and roses and sweet smells! The sun shone warmest there, and the fairies lived there, Mother said.

"But when it rains, Mother?"

"Oh, then they hide beneath the trellis, under the honeysuckles."

Mother wore an apron and sun-bonnet, and knelt in the little path, digging with a trowel in the moist, brown earth. You helped her with your little spade. Under a lilac-bush Lizbeth made mud-pies, and the pies of the enchanted garden were the brownest and richest in all Our Yard. They were the most like Mother's, Lizbeth said. Grandfather sat on the wheelbarrow-ship and smoked.

"Do fairies smoke, Grandfather?"

"The old grandfather fairies do," he said.

Of all the flowers in the enchanted garden you liked the roses best, and of all the roses you liked the red. There was a big one that hung on the wall above your head. You could just reach it when you stood on tiptoe, and pulling it down to you then, you would bury your face in its petals and take a long snuff, and say,

"Um-m-m."

And when you let it go, it bobbed and courtesied on its prickly stem. But one morning, very early, when you pulled it down to you, you were rough with it, and it sprinkled your face with dew.

"The rose is crying," Lizbeth said.

"You should be very gentle with roses," Mother told you. "Sometimes when folks are sick or cross, just the sight of a red rose cheers them and makes them smile again."

That was a beautiful thought, and it came back to you the day you left Our Yard and ran away. You were gone a long time. It was late in the afternoon when you trudged guiltily back again, and when you were still a long way off you could see Mother waiting for you at the gate. The brown switch, doubtless, was waiting too. So you stole into Our Yard through the back fence, and hid in the enchanted garden, crying and afraid. It began to rain, a gentle summer shower, and like the fairies you hid beneath the honeysuckles. Looking up through your tears, you saw the red rose—and remembered. The rain stopped. You climbed upon the wheelbarrow-ship and pulled the rose from the vine. Trembling, you approached the house. Softly you opened the front door. At the sight of you Mother gave a little cry. Your lip quivered; the tears rolled down your cheeks; for you were cold and wet and dreary.

"M-mother," you said, with outstretched hand, "here's a r-rose I brought you"; and she folded you and the flower in her arms. It was true, then, what she had told you—that when people are cross there is sometimes nothing in the world like the sight of a sweet red rose to cheer them and make them smile again.

Once in Our Yard, you were safe from bad boys and their fists, from bad dogs and their bites, and all the other perils of the road. Yet Our Yard had its dangers too. Through the rhubarb thicket in the corner of the fence stalked a black bear. You had heard him growl. You had seen the flash of his white teeth. You had tracked him to his lair. Just behind you, one hand upon your coat, came Lizbeth.

"'Sh! I see him," you whispered, as you raised your wooden gun.

Bang! Bang!

And the bear fell dead.

"Don't hurt Pussy," said Mother, warningly.

"No," you said, and the dead bear purred and rubbed his head against your legs. Once, after you had killed and eaten him, he mewed and ran before you to his basket-cave; and there were five little bears, all blind and crying, and you took them home and tamed them by the kitchen fire.

But the bear was nothing to the Wild Man who lived next door. In the barn, close to your fence, he lay in wait for little girls and boys to eat them and drink their blood and gnaw their bones. Oh, you had seen him once yourself, as you peered through a knot-hole in the barn-side. He was sitting on an upturned water-pail, smoking a pipe and muttering.

You and Lizbeth stole out to look at him. Hand in hand you tiptoed across the clover prairie where the red Indians roved. You scanned the horizon, but there was not a feather or painted face in sight to-day—though they always came when you least expected them, popping up from the tall grass with wild, blood-curdling yells, and scalping you when you didn't watch out. Across the prairie, then, you went, silently, hand in hand. The sun fell warm and golden in the open. Birds were singing in the sky, unmindful of the lurking perils among the tall grass and beyond the fence. Back of you were home and Mother's arms, and in the pantry window, cooling, two juicy pies. Before you, across the clover, a great gray dungeon frowned upon you; within its walls a creature of blood and mystery waiting with hungry jaws. Hushed and timorous, you approached.

"Oh, I'm afraid," Lizbeth whimpered. Savagely you caught her arm.

"'Sh! He'll hear you," you hissed through chattering teeth. A cloud hid the sun, and the ominous shadow fell upon you as you crouched, trembling, on the edge of the raspberry wood.

"Sh!" you said. Under cover of the forest shade you crept with bated breath, on all-fours, stealthily. Oh, what was that? That awful sound, that hideous groan? From the barn it came, with a crunching of teeth and a rattle of chain. Lizbeth gave a little cry, seized you, and hid her face against your coat.

"'Sh!" you said. "That's him! Hear him!"

Through wood and prairie rang a piercing cry—

"Mother! I want my mother!"

And Lizbeth fled, wailing, across the plain. You followed—to cheer her.

"Cowardy Calf!" you said, but you did not say it till you had reached the kitchen door. And in hunting the Wild Man you never got farther than his groan.

Mornings in Our Yard the clover prairie sparkled with a million gems. The fairies had dropped them, dancing in the moonbeams, while you slept. Strung on a blade of grass you found a necklace of diamonds left by the queen herself in her flight at dawn, but when you plucked it, the quivering brilliants melted into water drops and trickled down your hand. Then the warm sun came and took the diamonds back to the fairies again—but your shoes were still damp with dew. And by-and-by you would be sneezing, and Mother would be taking down bottles for you, for the things that fairies wear are not good for little boys. And if ever you squash the fairies' diamonds beneath your feet, and don't change your shoes, the fairies will be angry with you, and you will be catching cold; and if you take the queen's necklace—oh, then watch out, for they will be putting a necklace of red flannel on you!

Wide-awake was Our Yard in the morning with its birds and wind and sunshine and your play, but when noonday dinner was over there was a yawning in the trees. The birds hushed their songs. Grandfather dozed in his chair on the porch. The green grass dozed in the sun. And as the shadows lengthened even the perils slept—Indians on the clover prairie, bear in the rhubarb thicket, Wild Man in the barn. In the apple-tree shade you lay wondering, looking up at the sky—wondering why bees purred like pussy-cats, why the sparrows bowed to you as they eyed you sidewise, what they twittered in the leaves, where the clouds went when they sailed to the end of the sky. Three clouds there were, floating above the apple-tree, and two were big and one was little.

"The big clouds are the Mother and Father clouds," you told yourself, for no one was there to hear, "and the little one is the Little Boy cloud, and they are out walking in the sky. And now the Mother cloud is talking to the Little Boy cloud. 'Hurry up,' she says; 'why do you walk so slow?' And the Little Boy cloud says, 'I can't go any faster 'cause my legs are so short.' And then the Father cloud laughs and says, 'Let's have some ice-cream soda.' Then the Little Boy cloud says, 'I'll take vaniller, and make it sweet,' and they all drink. And by-and-by they all go home and have supper, and after supper the Mother cloud undresses the Little Boy cloud, and puts on his nighty, and he kneels down and says, 'Now I lay me down to sleep.' And then the Mother cloud kisses the Little Boy cloud on both cheeks and on his eyes and on his curls and on his mouth twice, and he cuddles down under the moon and goes to sleep. And that's all."

Far beyond the apple-tree, far beyond your ken, the three clouds floated—Father and Mother and Little Son—else your story had been longer; and in the floating of little clouds, in the making of little stories, in the sleeping of little boys, it was always easiest when Our Yard slumbered in the afternoon.

When supper was over a bonfire blazed in the western sky, just over the back fence. The clouds built it, you explained to Lizbeth, to keep themselves warm at night. It was a beautiful fire, all gold and red, but as Our Yard darkened, the fire sank lower till only the sparks remained, and sometimes the clouds came and put the sparks out too. When the moon shone you could see, through the window by your bed, the clover prairie and the trellis mountains, silver with fairies, and you longed to hold one in your hand. But when the night fell moonless and starless, the fairies in Our Yard groped their way—you could see their lanterns twinkling in the trees—and there were goblins under every bush, and, crouching in the black shadows, was the Wild Man, gnawing a little boy's bone. Oh, Our Yard was awful on a dark night, and when you were tucked in bed and the lamp was out and Mother away downstairs, you could hear the Wild Man crunching his bone beneath your window, and you pulled the covers over your head. But always, when you woke, Our Yard was bright and green again, for though the moon ran away some nights, the sun came every day.

With all its greenness and its brightness and its vastness and its enchanted garden, Our Yard bore a heavy yoke. You were not quite sure what the burden was, but it was something about tea. Men, painted and feathered like the red Indians, had gone one night to a ship in the harbor and poured the tea into the sea. That you knew; and you had listened and heard of the midnight ride of Paul Revere. Through the window you saw Our Yard smiling in the morning sun; trees green with summer; flight of white clouds in the sky; flight of brown birds in the bush. Wondering, you saw it there, a fair land manacled by a tyrant's hand, and the blood mounted to your cheeks.

"Mother, I want my sword."

"It is where you left it, my boy."

"And my soldier-hat and drum."

"They are under the stairs."

Over your shoulder you slung your drum. With her own hands Mother belted your sword around you and set your cocked hat on your curls. Then twice she kissed you, and you marched away to the music of your drum. She watched you from the open door.

It was a windy morning, and you were bravest in the wind. From the back fence to the front gate, from the beehives to the red geraniums, there was a scent and stir of battle in the air. Rhubarb thicket and raspberry wood re-echoed with the beat of drums and the tramp of marching feet. Far away beyond the wood-pile hills, behind the trellis mountains where the morning-glories clung, tremulous, in the gale, even the enchanted garden woke from slumber and the flowers shuddered in their peaceful beds. On you marched, through the wind and the morning, on through Middlesex, village and farm, till you heard the cannon and the battle-cries.

"Halt!"

You unslung your drum. Mounting your charger, you galloped down the line.

"Forward!"

And you rode across the blood-stained clover. Into the battle you led them, sword in hand—into the thickest of the fight—while all about you, thundering in the apple-boughs, reverberating in the wood-pile hills, roared the guns of the west wind. Fair in the face of that cannonade you flung the flower of your army. Around you lay the wounded, the dead, the dying. Beneath you your charger fell, blood gushing from his torn side. A thrust bayonet swept off your cocked hat. You were down yourself. Tut! 'Twas a mere scratch—and you struggled on. Repulsed, you rallied and charged again ... again ... again, across the clover, to the mouths of the smoking guns. Afoot, covered with blood, your shattered sword gleaming in the morning sun, you stood at last on the scorched heights. Before your flashing eyes, a rout of redcoats in retreat; behind your tossing curls, the buff and blue.

A cry of triumph came down the beaten wind:

"Mother! Mother! We licked 'em!"

"Whom?"

"The Briddish!"

And Our Yard was free.

The Toy Grenadier

t was a misnomer. He was not a captain at all, nor was he of the Horse Marines. He was a mere private in the Grenadier Guards, with his musket at a carry and his heels together, and his little fingers touching the seams of his pantaloons. Still, Captain Jinks was the name he went by when he first came to Our House, years ago, and Captain Jinks he will be always in your memory—the only original Captain Jinks, the ballad to the contrary notwithstanding.

t was a misnomer. He was not a captain at all, nor was he of the Horse Marines. He was a mere private in the Grenadier Guards, with his musket at a carry and his heels together, and his little fingers touching the seams of his pantaloons. Still, Captain Jinks was the name he went by when he first came to Our House, years ago, and Captain Jinks he will be always in your memory—the only original Captain Jinks, the ballad to the contrary notwithstanding.

It was Christmas Eve when you first saw him. He was stationed on sentry duty beneath a fir-tree, guarding a pile of commissary stores. He looked neither to the left nor to the right, but straight before him, and not a tremor or blink or sigh disturbed his military bearing. His bearskin was glossy as a pussy-cat's fur; his scarlet coat, with the cross of honor on his heart, fitted him like a glove, and every gilt button of it shone in the candlelight; and oh, the loveliness, the spotless loveliness, of his sky-blue pantaloons!

"My boy," said Father, "allow me to present Captain Jinks. Captain Jinks, my son."

"Oh!" you cried, the moment you clapped eyes on him. "Oh, Father! What a beautiful soldier!"

And at your praise the Captain's checks were scarlet. He would have saluted, no doubt, had you been a military man, but you were only a civilian then.

"Take him," said Father, "and give him some rations. He's about starved, I guess, guarding those chocolates."

So you relieved the Captain of his stern vigil—or, rather, the Captain and his gun, for he refused to lay down his arms even for mess call, without orders from the officer of the guard, though he did desert his post, which was inconsistent from a military point of view, and deserved court-martial. And while he was gone the commissary stores were plundered by ruthless, sticky hands.

Lizbeth brought a new wax doll to mess with the Captain. A beautiful blonde she was, and the Captain was gallantry itself, but she was a little stiff with him, in her silks and laces, preferring, no doubt, a messmate with epaulets and sword. So the chat lagged till the Rag Doll came—an unassuming brunette creature—and the Captain got on very well with her. Indeed, when the Wax Doll flounced away, the Captain leaned and whispered in the Rag Doll's ear. What he said you did not hear, but the Rag Doll drew away, shyly—

"Very sudden," she seemed to say. But the Captain leaned nearer, at an angle perilous to both, and—kissed her! The Rag Doll fainted to the floor. The Captain was at his wits' end. Without orders he could not lay aside his gun, for he was a sentry, albeit off his post. Yet here was a lady in distress. The gun or the lady? The lady or the gun? The Captain struggled betwixt his honor and his love. In the very stress of his contending emotions he tottered, and would have fallen to the Rag Doll's side, but you caught him just in time. Lizbeth applied the smelling-bottle to the Rag Doll's nose, and she revived. Pale, but every inch a rag lady, she rose, leaning on Lizbeth. She gave the Captain a withering glance, and swept towards the open door. The Captain did not flinch. Proudly he drew himself to his full height; his heels clicked together; his gun fell smartly to his side; and as the lady passed he looked her squarely in her scornful eyes, and bore their congé like a soldier.

Next morning—Christmas morning—in the trenches before the Coal Scuttle, the Captain fought with reckless bravery. The earthworks of building-blocks reached barely to his cartridge-belt, yet he stood erect in a hail of marble balls.

"Jinks, you're clean daft," cried Grandfather. "Lie down, man!"

But the Captain would not budge. Commies and glassies crashed around him. They ploughed up the earthworks before him; they did great execution on the legs of chairs and tables and other non-combatants behind. Yet there he stood, unmoved in the midst of the carnage, his heels together, his little fingers just touching the seams of his pantaloons. It was for all the world as though he were on dress parade. Perhaps he was—for while he stood there, valorous in that Christmas fight, his eyes were on the heights of Rocking Chair beyond, where, safe from the marble hail, sat the Rag Doll with Lizbeth and the waxen blonde.

There was a rumble—a crash through the torn earthworks—a shock—a scream from the distant heights—and the Captain fell. A monstrous glassy had struck him fairly in the legs, and owing to his military habit of standing with them close together—well, it was all too sad, too harrowing, to relate. An ambulance corps of Grandfather and Uncle Ned carried the crippled soldier to the Tool Chest Hospital. He was just conscious, that was all. The operation he bore with great fortitude, refusing to take chloroform, and insisting on dying with his musket beside him, if die he must. What seemed to give him greatest anguish was his heels, for, separated at last, they would not click together now; and his little fingers groped nervously for the misplaced seams of his pantaloons.

Long afterwards, when the Captain had left his cot for active duty again, it was recalled that the very moment when he fell so gallantly in the trenches that day a lady was found unconscious, flat on her face, at the foot of Rocking Chair Hill.

Captain Jinks was never the same after that. Still holding his gun as smartly as before, there was, on the other hand, a certain carelessness of attire, a certain dulness of gilt buttons, a smudginess of scarlet coat, as though it were thumb-marked; and dark clouds were beginning to lower in the clear azure of his pantaloons. There was, withal, a certain rakishness of bearing not provided for in the regulations; a little uncertainty as to legs; a tilt and limp, as it were, in sharp contrast to the trim soldier who had guarded the commissary chocolates under the Christmas fir. Moreover—though his comrades at arms forbore to mention it, loving him for his gallant service—he was found one night, flat on his face, under the dinner-table. Now the Captain had always been abstemious before. Liquor of any kind he had shunned as poison, holding that it spotted his uniform; and once when forced to drink from Lizbeth's silver cup, at the end of a dusty march, his lips paled at the contaminating touch, his red cheeks blanched, and his black mustache, in a single drink, turned gray. But here he lay beneath the festive board, bedraggled, his nose buried in the soft rug, hopelessly inarticulate—though the last symptom was least to be wondered at, since he had always been a silent man.

You shook him where he lay. There was no response. You dragged him forth in his shame and set him on his feet again, but he staggered and fell. Yet as he lay there in his cups—oh, mystery of discipline!—his heels were close together, his toes turned out, his musket was at a carry, and his little fingers were just touching the seams of his pantaloons.