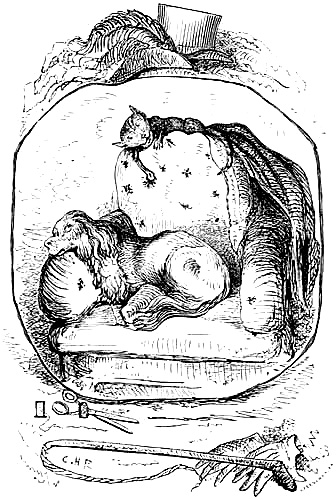

THE DOCTOR’S PET.

Page 48.

LONDON:

GRIFFITH & FARRAN,

CORNER OF ST. PAUL’S CHURCHYARD.

MDCCCLXVIII.

THE

BOOK OF CATS.

A Chit-Chat Chronicle

OF

FELINE FACTS AND FANCIES, LEGENDARY, LYRICAL

MEDICAL, MIRTHFUL AND MISCELLANEOUS.

By Charles H. Ross.

WITH

Twenty Illustrations by the Author.

LONDON:

GRIFFITH AND FARRAN,

(SUCCESSORS TO NEWBERY AND HARRIS),

CORNER OF ST. PAUL’S CHURCHYARD.

MDCCCLXVIII.

LONDON:

WERTHEIMER, LEA AND CO., PRINTERS, CIRCUS PLACE,

FINSBURY CIRCUS.

The Author would thankfully receive any well-authenticated anecdotes respecting Cats, with the view of incorporating them with the work, in the event of a fresh Edition being called for.

Spring Cottage, Fulham.

November, 1867.

| Page | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Of the reason why this Book was written, and of several sorts of Cats which are not strictly Zoological | 3 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Of some Wicked Stories that have been told about Cats | 15 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Of other Wicked Stories, with a few Words in Defence of the Accused | 35 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Of the Manners and Customs of Cats | 59 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Of Whittington’s Cat, and another Cat that visited Strange Countries | 79 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Of various kinds of Cats, Ancient and Modern | 91 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Of some Clever Cats | 111 |

| [Pg viii] | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Of some amiable Cats, and Cats that have been good Mothers | 139 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Of Puss in Proverbs, in the Dark Ages, and in the Company of Wicked Old Women | 159 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Of a certain Voracious Cat, some Goblin Cats, Magical Cats, and Cats of Kilkenny | 185 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Of Pussy poorly, and of some Curiosities of the Cat’s-meat Trade | 207 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Of Wild Cats, Cat Charming, etc. | 229 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Conclusion | 275 |

The Book of Cats.

Of the reason why this Book was written, and of several sorts of Cats which are not strictly Zoological.

ne day, ever so long ago, it struck me that I should like to try and

write a book about Cats. I mentioned the idea to some of my friends: the

first burst out laughing at the end of my opening sentence, so I refrained

from entering into further details. The second said there were a hundred

books about Cats already. The third said, “Nobody would[Pg 4] read it,” and

added, “Besides, what do you know of the subject?” and before I had time

to begin to tell him, said he expected it was very little. “Why not Dogs?”

asked one friend of mine, hitting upon the notion as though by

inspiration. “Or Horses,” said some one else; “or Pigs; or, look here,

this is the finest notion of all:—

ne day, ever so long ago, it struck me that I should like to try and

write a book about Cats. I mentioned the idea to some of my friends: the

first burst out laughing at the end of my opening sentence, so I refrained

from entering into further details. The second said there were a hundred

books about Cats already. The third said, “Nobody would[Pg 4] read it,” and

added, “Besides, what do you know of the subject?” and before I had time

to begin to tell him, said he expected it was very little. “Why not Dogs?”

asked one friend of mine, hitting upon the notion as though by

inspiration. “Or Horses,” said some one else; “or Pigs; or, look here,

this is the finest notion of all:—

‘THE BOOK OF DONKIES,

BY ONE OF THE FAMILY!’”

Somewhat disheartened by the reception my little project had met with, I gave up the idea for awhile, and went to work upon other things. I cannot exactly remember what I did, or how much, but my book about Cats was postponed sine die, and in the meantime I made some inquiries.

I searched high and low; I consulted Lady Cust’s little volume; I bought Mr. Beeton’s book; I read up Buffon and Bell, and Frank Buckland; I eagerly perused the amusing pages of the Rev. Mr. Wood; I looked through two or three hundred works of one sort and another, and as many old newspapers and odd numbers of defunct periodicals, and although I daresay I have overlooked some of the very best, I have really taken a great deal of[Pg 5] trouble, and sincerely hope that I shall be able to amuse you by my version of what other people have had to tell, with a good many things which have not yet appeared in print, that I have to tell myself.

One thing I found out very early in my researches, and that was, that nine out of ten among my authorities were prejudiced against the animal about which they wrote, and furthermore, that they knew very little indeed upon the subject. Take for instance our old friend Mavor, who thus mis-teaches the young idea in his celebrated Spelling Book. “Cats,” says Mr. Mavor, “have less sense than dogs, and their attachment is chiefly to the house; but the dog’s is to the persons who inhabit it.” Need I tell the reader who has thought it worth his while to learn anything of the Cat’s nature, that Mr. Mavor’s was a vulgar and erroneous belief, and that there are countless instances on record where Cats have shown the most devoted and enduring attachment to those who have kindly treated them. Again, nothing can be more unjust than to call Cats cruel. If such a word as cruel could be applied to a creature without reason, few animals could be found more cruel than a Robin Redbreast, which we have all determined to make a pet of[Pg 6] since somebody wrote that pretty fable about the “Babes in the Wood.” And apropos of the Robin, do you remember Canning’s verses?

“Tell me, tell me, gentle Robin,

What is it sets thy heart a-throbbing?

Is it that Grimalkin fell

Hath killed thy father or thy mother,

Thy sister or thy brother,

Or any other?

Tell me but that,

And I’ll kill the Cat.

But stay, little Robin, did you ever spare,

A grub on the ground or a fly in the air?

No, that you never did, I’ll swear;

So I won’t kill the Cat,

That’s flat.”

But all the cruel and unjust things that have been said about poor pussy I will tell you in another chapter. I mean to try and begin at the beginning. In the first place, what is the meaning of the word “Cat.” Let us look in the dictionary. A Cat, according to Dr. Johnson, is “a domestick animal that catches mice.” But the word has one or two other meanings, for instance:—

In thieves’ slang the word “Cat” signifies a lady’s muff, and “to free a cat” to steal a muff. Among soldiers and sailors a “Cat” means something very unpleasant indeed, with nine tingling lashes or tails,[Pg 7] so called, from the scratches they leave on the skin, like the claws of a cat.

A Cat is also the name for a tackle or combination of pulleys, to suspend the anchor at the cat’s-head of a ship.

Cat-harping is the name for a purchase of ropes employed to brace in the shrouds of the lower masts behind their yards.

The Cat-fall is the name of a rope employed upon the Cat-head. Two little holes astern, above the Gun-room ports, are called Cat-holes.

A Cat’s-paw is a particular turn in the bight of a rope made to hook a tackle in; and the light air perceived in a calm by a rippling on the surface of the water, is known by the same name.

A kind of double tripod with six feet, intended to hold a plate before the fire and so constructed that, in whatever position it is placed, three of the legs rest on the ground, is called a Cat, from the belief that however a Cat may be thrown, she always falls on her feet.

Cat-salt is a name given by our salt-workers to a very beautifully granulated kind of common salt.

Cat’s-eye or Sun-stone of the Turks is a kind of gem found chiefly in Siberia. It is very hard and semi-transparent, and has different points from[Pg 8] whence the light is reflected with a kind of yellowish radiation somewhat similar to the eyes of cats.

Catkins are imperfect flowers hanging from trees in the manner of a rope or cat’s-tail.

Cat’s-meat, Cat-thyme, and Cat’s-foot are the names of herbs; Cat’s-head of an apple, and also of a kind of fossil. Cat-silver is a fossil. Cat’s-tail is a seed or a long round substance growing on a nut-tree.

A Cat-fish is a shark in the West Indies. Guanahani, or Cat Island, a small island of the Bahama group, in the West Indies, is supposed to be so called because wild Cats of large size used to infest it, but I can find no particulars upon the subject in the works of writers on the West Indies.

In the North of England, a common expression of contempt is to call a person Cat-faced. Artists call portraits containing two-thirds of the figure Kit-cat size. With little boys in the street a Cat is a dreadfully objectionable plaything, roughly cut out of a stick or piece of wood, and sharpened at each end. Those whose way to business lies through low neighbourhoods, and who venture upon short cuts, well know from bitter experience that at a certain period of the year the tip-cat season sets in with awful severity, and then it is not safe for [Pg 9]such as have eyes to lose, to wander where the epidemic rages.

TIP-CAT.

Page 8.

In the North, however, the same game is called “Piggie.” I learn by the newspaper that a young woman at Leeds nearly lost her eye-sight by a blow from one of these piggies or cats, and the magistrates sent the boy who was the cause of it to an industrial school, ordering his father to pay half-a-crown a week for his maintenance.

The shrill whistle indulged in upon the first night of a pantomime by those young gentlemen with the figure six curls in the front row of the gallery are denominated cat-calls. This is, I am given to understand, a difficult art to acquire—I know I have tried very hard myself and can’t; and to arrive at perfection you must lose a front tooth. Such a thing has been known before this, as a young costermonger having one of his front teeth pulled out to enable him to whistle well. Let us hope that his talent was properly appreciated in the circles in which he moved.

With respect to cat-calls or cat-cals, also termed cat-pipes, it would appear that there was an instrument by that name used by the audiences at the theatre, the noise of which was very different to that made by whistling through the fingers, as now[Pg 10] practised. In the Covent Garden Journal for 1810 the O. P. Riots are thus spoken of:—“Mr. Kemble made his appearance in the costume of ‘Macbeth,’ and, amid vollies of hissing, hooting, groans, and cat-calls, seemed as though he meant to speak a steril and pointless address announced for the occasion.”

In book iii. chap. vi. of Joseph Andrews, occurs this passage:—“You would have seen cities in embroidery transplanted from the boxes to the pit, whose ancient inhabitants were exalted to the galleries, where they played upon cat-calls.”

In Lloyd’s Law Student we find:—

“By law let others strive to gain renown!

Florio’s a gentleman, a man o’ th’ town.

He nor courts clients, or the law regarding,

Hurries from Nando’s down to Covent Garden.

Zethe’s a scholar—mark him in the pit,

With critic Cat-call sound the stops of wit.”

In Chetwood’s History of the Stage (1741), there is a story of a sea-officer who was much plagued by “a couple of sparks, prepared with their offensive instruments, vulgarly termed Cat-calls;” and describes how “the squeak was stopped in the middle by a blow from the officer, which he gave with so strong a will that his child’s trumpet was struck through his cheek.”

[Pg 11]The Cat-call used at theatres in former times was a small circular whistle, composed of two plates of tin of about the size of a half-penny perforated by a hole in the centre, and connected by a band or border of the same metal about one-eighth of an inch thick. The instrument was readily concealed within the mouth, and the perpetrator of the noise could not be detected.

There used to be a public-house of some notoriety at the corner of Downing-street, next to King-street, called the “Cat and Bagpipes.” It was also a chop house used by many persons connected with the public offices in the neighbourhood. George Rose, so well known in after life as the friend of Pitt, Clerk of the Parliament, Secretary of the Treasury, etc., and executor of the Earl of Marchmont, but then “a bashful young man,” was one of the frequenters of this tavern.

Madame Catalini is thus alluded to with disrespectful abbreviation of her name in a new song on Covent Garden Theatre, printed and sold by J. Pitts, No. 14, Great St. Andrew-street, Seven Dials.

“This noble building, to be sure, has beauty without bounds,

It cost upwards of one hundred and fifty thousand pounds;

They’ve Madame Catalini there to open her white throat,

But to hear your foreign singers I would not give a groat;

[Pg 12]So haste away unto the play, whose name has reached the skies,

And when the Cati ope’s her mouth, oh how she’ll catch the flies!”

It was once upon a time the trick of a countryman to bring a Cat to market in a bag, and substitute it for a sucking pig in another bag, which he sold to the unwary when he got the chance. If the trick was discovered prematurely, it was called letting the cat out of the bag—if not—he that made the bad bargain was said to have bought a pig in a poke. To turn the Cat in the pan, according to Bacon, is when that which a man says to another he says it as if another had said it to him.

There is a kind of ship, too, called a Cat, a vessel formed on the Norwegian model, of about 600 tons burthen. That was the sort of cat that brought the great Dick Whittington, of “turn again” memory, his fortune. Do you remember how sorry you were to find out the truth? Do you recollect what a pang it cost you when first you heard that Robinson Crusoe was not true? I shall never forget how vexed and disappointed I was at hearing that Dick Turpin never did ride to York on his famous mare Black Bess, and that no such person as William Tell ever existed, and that that beautiful story about the apple was only a beautiful story after all.

Of some Wicked Stories that have been told about Cats.

do not love a Cat,” says a popular author, often quoted; “his

disposition is mean and suspicious. A friendship of years is cancelled in

a moment by an accidental tread on the tail. He spits, twirls his tail of

malignity, and shuns you, turning back as he goes off a staring vindictive

face full of horrid oaths and unforgiveness, seeming to say, ‘Perdition

catch you! I hate you for ever.’ But the Dog is my delight. Tread[Pg 16] on his

tail, he expresses for a moment the uneasiness of his feelings, but in a

moment the complaint is ended: he runs round you, jumps up against you,

seems to declare his sorrow for complaining, as it was not intentionally

done,—nay, to make himself the aggressor, and begs, by whinings and

lickings, that the master will think of it no more.” No sentiments could

be more popular with some gentlemen. In the same way there are those who

would like to beat their wives, and for them to come and kiss the hand

that struck them in all humility. It is not only when hurt by accident

that the dog comes whining round its master. The lashed hound crawls back

and licks the boot that kicked him, and so makes friends again. Pussy will

not do that though. If you want to be friendly with a cat on Tuesday, you

must not kick him on Monday. You must not fondle him one moment and

illtreat him the next, or he will be shy of your advances. This really

human way of behaving makes Pussy unpopular.

do not love a Cat,” says a popular author, often quoted; “his

disposition is mean and suspicious. A friendship of years is cancelled in

a moment by an accidental tread on the tail. He spits, twirls his tail of

malignity, and shuns you, turning back as he goes off a staring vindictive

face full of horrid oaths and unforgiveness, seeming to say, ‘Perdition

catch you! I hate you for ever.’ But the Dog is my delight. Tread[Pg 16] on his

tail, he expresses for a moment the uneasiness of his feelings, but in a

moment the complaint is ended: he runs round you, jumps up against you,

seems to declare his sorrow for complaining, as it was not intentionally

done,—nay, to make himself the aggressor, and begs, by whinings and

lickings, that the master will think of it no more.” No sentiments could

be more popular with some gentlemen. In the same way there are those who

would like to beat their wives, and for them to come and kiss the hand

that struck them in all humility. It is not only when hurt by accident

that the dog comes whining round its master. The lashed hound crawls back

and licks the boot that kicked him, and so makes friends again. Pussy will

not do that though. If you want to be friendly with a cat on Tuesday, you

must not kick him on Monday. You must not fondle him one moment and

illtreat him the next, or he will be shy of your advances. This really

human way of behaving makes Pussy unpopular.

I am afraid that if it were to occur to one of our legislators to tax the Cats, the feline slaughter would be fearful. Every one is fond of dogs, and yet Mr. Edmund Yates, travelling by water to Greenwich last June, said that the journey was[Pg 17] pleasingly diversified by practical and nasal demonstrations of the efficient working of the Dog-tax. “No fewer than 292 bodies of departed canines, in various stages of decomposition, were floating off Greenwich during the space of seven days in the previous month, seventy-eight of which were found jammed in the chains and landing-stages of the “Dreadnought” hospital ship, thereby enhancing the salubrity of that celebrated hothouse for sick seamen.” And I cannot venture to repeat the incredible stories of the numbers said to have been taken from the Regent’s Canal.

There are some persons who profess to have a great repugnance to Cats. King Henry III. of France, a poor, weak, dissipated creature, was one of these. According to Conrad Gesner, men have been known to lose their strength, perspire violently, and even faint at the sight of a cat. Others are said to have gone even further than this, for some have fainted at a cat’s picture, or when they have been in a room where such a picture was concealed, or when the picture was as far off as the next room. It was supposed that this sensitiveness might be cured by medicine. Let us hope that these gentlemen were all properly physicked. I myself have often heard men express similar sentiments of aversion[Pg 18] to the feline race; and sometimes young ladies have done so in my hearing. In both cases I have little doubt but that the weakness is easily overcome. As for a hidden and unheard Cat’s presence affecting a person’s nerves, I beg to state my conviction that such a story is utterly ridiculous; and I was vastly entertained by the following narrative, written by a lady for a Magazine for Boys, and given as a truth. Such a valuable fact in natural history should not be allowed to perish; she calls it, A TALE OF MY GRANDMOTHER.

My maternal grandmother had so strong an aversion to Cats that it seemed to endow her with an additional sense. You may, perhaps, have heard people use the phrase, that they were “frightened out of their seven senses,” without troubling yourselves to wonder how they came to have more than five. But the Druids of old used to include sympathy and antipathy in the number, a belief which has, no doubt, left its trace in the above popular and otherwise unmeaning expression; and this extra sense of antipathy my grandmother certainly exhibited as regarding Cats.

When she was a young and pretty little bride, dinner parties and routs, as is usual on such occasions, were given in her honour. In those days,[Pg 19] now about eighty years ago, people usually dined early in the afternoon, and you may imagine somewhere in Yorkshire, a large company assembled for a grand dinner by daylight. With all due decorum and old-fashioned stately politeness, the ladies in rustling silks, stately hoops, and nodding plumes, are led to their seats by their respective cavaliers, in bright coloured coats with large gilt buttons.

With dignified bows and profound curtsies, they take their places, the bride, of course, at her host’s right hand. The bustle subsides, the servants remove the covers, the carving-knives are brandished by experienced hands, and the host having made the first incision in a goodly sirloin or haunch, turns to enquire how his fair guest wishes to be helped.

To his surprise, he beholds her pretty face flushed and uneasy, while she lifts the snowy damask and looks beneath the table.

“What is the matter, my dear madam? Have you lost something?”

“No, sir, nothing, thank you;—it is the Cat,” replied the timid bride, with a slight shudder, as she pronounced the word.

“The Cat?” echoed the gentleman, with a puzzled[Pg 20] smile; “but, my dear Mrs. H——, we have no Cat!”

“Indeed! that is very odd, for there is certainly a Cat in the room.”

“Did you see it then?”

“No, sir, no: I did not see it, but I know it is in the room.”

“Do you fancy you heard one then?”

“No, sir.”

“What is the matter, my dear?” now enquires the lady of the house, from the end of the long table; “the dinner will be quite cold while you are talking to your fair neighbour so busily.”

“Mrs. H—— says there is a Cat in the room, my love; but we have no Cat, have we?”

“No, certainly!” replied the lady tartly. “Do carve the haunch, Mr.——.”

The footman held the plate nearer, a due portion of the savoury meat was placed upon it.

“To Mrs. H——,” said the host, and turned to look again at his fair neighbour; but her uneasiness and confusion were greater than ever. Her brow was crimson—every eye was turned towards her, and she looked ready to cry.

“I will leave the room, if you will allow me, sir, for I know that there is a Cat in the room.”

[Pg 21]“But, my dear madam—”

“I am quite sure there is, sir; I feel it—I would rather go.”

“John, Thomas, Joseph, can there be a Cat in the room?” demanded the embarrassed host of the servants.

“Quite impossible, sir;—have not seen such a hanimal about the place since I comed, any way.”

“Well, look under the table, at any rate; the lady says she feels it; look in every corner of the room, and let us try to convince her.”

“My dear, my dear!” remonstrated the annoyed bridegroom from a distant part of the table; “what trouble you are giving.”

“Indeed, I would rather leave the room,” said the little bride, slipping from her chair. But, meanwhile, the servants ostentatiously bustled in their unwilling search for what they believed to be a phantom fancy of the young lady’s brain; when, lo! one of the footmen took hold of a half-closed window-shutter, and from the aperture behind out sprang a large cat into the midst of the astonished circle, eliciting cries and exclamations from others than the finely organised bride, who clasped her hands rigidly, and gasped with pallid lips.

[Pg 22]Such facts as this are curious, certainly, and remain a puzzle to philosophers.

This habit of hiding itself in secret places is one of the most unpleasant characteristics of the Cat. I know many instances of it—especially of a night alarm when we were children, ending in a strange cat being found in a clothes bag.

Here, indeed, we have truth several degrees stranger than fiction; but this is not the only wonderful story the authoress has to tell. I will give you some others very slightly abridged.

“A year or two ago, a man in the south of Ireland severely chastised his cat for some misdemeanour, immediately after which the animal stole away, and was seen no more.

“A few days subsequently, as this man was starting to go from home, the Cat met and stood before him in a narrow path, with rather a wicked aspect. Its owner slashed his handkerchief at her to frighten her out of the way, but the Cat, undismayed, sprang at the hand, and held it with so ferocious a gripe, that it was impossible to make it open its jaws, and the creature’s body had actually to be cut from the head, and the jaws afterwards to be severed, before the mangled hand could be extricated. The man died from the injuries.”

[Pg 23]The jaws of a Cat are comparatively strong, and worked by powerful muscles; it has thirty-four teeth, but they are for the most part very tiny teeth, like pin’s points. What, I wonder, were the dimensions of this ferocious animal with the iron jaws; and how many courageous souls were engaged in its destruction. If this story is, however, rather hard to swallow, the next is not less so. Says our authoress:—

“I also know an Irish gentleman, who being an only son without any playmates, was allowed, when he was a child, to have a whole family of Cats sleeping in the bed with him every night.

“One day he had beaten the father of the family for some offence, and when he was asleep at night, the revengeful beast seized him by the throat, and would probably have killed him had not instant help been at hand. “The Cat sprang from the window, and was never more seen.” (Probably went away in a flash of blue fire.)

What do you think of these very strange stories? If they surprise you, however, what will you say to this one? “Dr. C——, an Italian gentleman still living in Florence (the initial is just a little unsatisfactory), who knew at least one of the parties, related to the authoress the following singular story.[Pg 24] A certain country priest in Tuscany, who lived quite alone with his servants, naturally attached himself, in the want of better society, to a fine he-cat, which sat by his stove in winter, and always ate from his plate.

One day a brother priest was the good man’s guest, and, in the rare enjoyment of genial conversation, the Cat was neglected; resenting this, he attempted to help himself from his master’s plate, instead of waiting for the special morsels which were usually placed on the margin for his use, and was requited with a sharp rap on the head for the liberty. This excited the animal’s indignation still more, and springing from the table with an angry cry, he darted to the other side of the room. The two priests thought no more of the Cat until the cloth was about to be removed; when the master of the house prepared a plateful of scraps for his forward favourite, and called him by name to come and enjoy his share of the feast. No joyful Cat obeyed the familiar call: his master observed him looking sulkily from the recess of the window, and rose, holding out the plate, and calling to him in a caressing voice. As he did not approach, however, the old gentleman put the platter aside, saying he might please himself, and sulk instead of dine,[Pg 25] if he preferred it; and then resumed his conversation with his friend. A little later the old gentleman showed symptoms of drowsiness, so his visitor begged that he would not be on ceremony with him, but lie down and take the nap which he knew he was accustomed to indulge in after dinner, and he in the meantime would stroll in the garden for an hour. This was agreed to. The host stretched himself on a couch, and threw his handkerchief over his face to protect him from the summer flies, while the guest stepped through a French window which opened on a terrace and shrubbery.

An hour or somewhat more had passed when he returned, and found his friend still recumbent: he did not at first think of disturbing him, but after a few minutes, considering that he had slept very long, he looked more observantly towards the couch, and was struck by the perfect immobility of the figure, and with something peculiar in the position of the head over which the handkerchief lay disordered. Approaching nearer he saw that it was stained with blood, and hastily removing it, saw, to his unutterable horror, that his poor friend’s throat was gashed across, and that life was already extinct.

He started back, shocked and dismayed, and for[Pg 26] a few moments remained gazing on the dreadful spectacle almost paralysed. Then came the speculation who could have done so cruel a deed? An old man murdered sleeping—a good man, beloved by his parishioners and scarcely known beyond the narrow circle of his rural home. It was his duty to investigate the mystery, so he composed his countenance as well as he was able, and going to the door of the room, called for a servant.

The man who had waited at table presently appeared, rubbing his eyes, for he, too, had been asleep.

“Tell me who has been into this room while I was in the garden.”

“Nobody, your reverence; no one ever disturbs the master during his siesta.”

He then asked the servant where he had been, and was told in the ante-room. He next enquired whether any person had been in or out of the house, or if he had heard any movement or voice in the room, and also how many fellow-servants the man had. He was told that he had heard no noise or voices, and that he had two fellow-servants—the cook and a little boy. His reverence demanded that they should be brought in, that he might question them.

[Pg 27]They came, and were cross-questioned as closely as possible, but they declared that they had not been in that part of the house all day long, and that nobody could possibly get into the house without their knowledge, unless it was through the garden. The priest had been walking all the time in view of the house, and he felt convinced that the murderer could not have passed in or out on that side without his knowledge.

“Listen to me; some person has been into that room since dinner, and your master is cruelly murdered.”

“Murdered!” cried the three domestics in tones of terror and amazement; “did your reverence say ‘murdered’?”

“He lies where I left him, but his throat is gashed from ear to ear—he is dead. My poor old friend!”

“Dead! the poor master dead, murdered in his own house.”

They wrung their hands, tore their hair, and wept aloud.

“Silence! I command you; and consider that every one of us standing here is liable to the suspicion of complicity in this foul deed; so look to it. Giuseppe was asleep.”

[Pg 28]“But I sleep very lightly, your reverence.”

“Come in and see your master,” said the priest solemnly.

They crept in, white with fear and stepping noiselessly. They gazed on the shocking spectacle transfixed with horror. Then a cry of “Who can have done it?” burst from all lips.

“Who, indeed?” repeated the cook.

The priest desired Giuseppe to look round the premises, and count the plate, and ascertain if there had been a robbery, or if any one was concealed about the house. The man returned without throwing any new light upon the mystery; but, in his absence, while surveying the room more carefully than he had previously done, the priest’s eye met those of the Cat glowing like lurid flames, as he sat crouching in the shade near a curtain. The orbs had a fierce malignant expression, which startled him, and at once recalled to his recollection the angry and sullen demeanour of the creature during dinner.

“Could it possibly be the Cat that killed him?” demanded of the cook the awe-struck priest.

“Who knows?” replied he; “the beast was surly to others, but always seemed to love him fondly; and then the wound seems as though it were made with a weapon.”

A TALE OF TERROR.

Page 29.

[Pg 29]“It does, certainly,” rejoined the priest; “yet I mistrust that brute, and we will try to put it to the proof, at any rate.”

After many suggestions, they agreed to pass cords round the neck and under the shoulders of the deceased, and carried the ends outside the room door, which was exactly opposite the couch where he lay. They then all quietly left the apartment, almost closing the door, and remained perfectly still.

One of the party was directed to keep his eye fixed on the Cat, the others after a short delay slowly pulled the cords, which had the effect of partially raising the head of the corpse.

Instantly, at this apparent sign of life, the savage Cat sprang from its corner, and, with a low yell and a single bound, fastened upon the mangled neck of its victim.

At once the sad mystery was solved, the treacherous, ungrateful, cowardly, and revengeful murderer discovered! and all that remained to be done was to summon help to destroy the wild beast, and in due time to bury the good man in peace.

Well, to such stories as these I have no particular objection, under certain circumstances. They are[Pg 30] well enough, for instance, to fill up the odd corners of a weekly newspaper in the dull season, and are a pleasant relief to the ‘enormous gooseberry’; but I have my doubts whether they should be given as facts for the instruction of youth, though I am not much surprised that the editor should have admitted them into his pages, when he speaks of them in another part of the magazine as “delightful papers.” When children’s minds are thus filled with absurd falsehoods, it is not to be wondered at if, when the child grows up into a man, the man should express himself somewhat in the words of this instructor of youth, who says, “I must confess, on my own part, an aversion to the feline race, which, with the best intentions, I am unable entirely to conquer. I have occasionally become rather fond of an individual Cat, but never encounter one, unexpectedly, without a feeling of repugnance; and, as I like, or feel an interest in, every other animal, I regard this peculiarity as hereditary.”

I suppose, however, that there are few of my fair readers who have not a feeling somewhat akin to repugnance towards snakes, black-beetles, earwigs, spiders, rats, and even poor little, harmless mice; yet ladies have been known to keep white mice, and make pets of them after a time, when the first[Pg 31] timidity was overcome. There was a captive once, you may remember, who tamed a spider. A man, about ten years ago, who used to go about the streets, got his living by pretending to swallow snakes. He allowed them, while holding tight on their tails, to crawl half-way down his throat and back again. He said they were nice clean animals, and good company. Little boys at school often swallow frogs. An earwig probably has fine social qualities, which only want bringing out: naturalists tell us they make the best of mothers. The black beetle has always been a maligned insect: it is a sort of nigger among insects, apparently born only to be poisoned, drowned, or smashed; but some one ought, decidedly, to take the race in hand and see of what it is capable. I have, myself, a horror of most of the creatures I have named, but happen not to have been reared with an aversion for Cats, and I have a strong belief that if I tried hard (which I am not going to do) I might get upon friendly relations with the other animals named above, which, I suppose, most of us are taught, when children, to dislike; and as our fathers and mothers have entertained the same feeling, perhaps, as my authoress says, we may “regard this peculiarity as hereditary.”

[Pg 32]Probably a good many ladies reading these lines will endorse my authoress’s opinions. For the most part these will be married ladies with large families; and it will be found upon enquiry, I feel certain, that ladies who have many children will have a dislike for the feline race.

Of other Wicked Stories, with a few Words in Defence of the Accused.

told you awhile ago what good Mr. Mavor says of Cats. “La défiance que

cet animal inspire,” says another instructor of youth, M. Pujoulx, in his

Livre du Second Age, “est bien propre à corriger de dissimulation et de

l’hypocrisie.” I have nothing to say of poor Pujoulx, whose books and

opinions are by this time well nigh forgotten; but what am I to think of

two other authors, whose words should be law,[Pg 36] but of the value of which

I leave you to judge for yourself. I need not, I think, remind you that

there is a natural history written by one Monsieur Buffon, “containing a

theory of the earth, a general history of man, of the brute creation, and

of vegetables, minerals, etc.,” of which Mr. Barr published an English

translation in ten goodly volumes. Thus, in this work of world-wide

celebrity, is the feline race discussed. I give the author’s words as I

find them:—

told you awhile ago what good Mr. Mavor says of Cats. “La défiance que

cet animal inspire,” says another instructor of youth, M. Pujoulx, in his

Livre du Second Age, “est bien propre à corriger de dissimulation et de

l’hypocrisie.” I have nothing to say of poor Pujoulx, whose books and

opinions are by this time well nigh forgotten; but what am I to think of

two other authors, whose words should be law,[Pg 36] but of the value of which

I leave you to judge for yourself. I need not, I think, remind you that

there is a natural history written by one Monsieur Buffon, “containing a

theory of the earth, a general history of man, of the brute creation, and

of vegetables, minerals, etc.,” of which Mr. Barr published an English

translation in ten goodly volumes. Thus, in this work of world-wide

celebrity, is the feline race discussed. I give the author’s words as I

find them:—

“The Cat is a faithless domestic, and only kept through necessity to oppose to another domestic which incommodes us still more, and which we cannot drive away; for we pay no respect to those, who, being fond of all beasts, keep Cats for amusement. Though these animals are gentle and frolicksome when young, yet they, even then, possess an innate cunning and perverse disposition, which age increases, and which education only serves to conceal. They are, naturally, inclined to theft, and the best education only converts them into servile and flattering robbers; for they have the same address, subtlety, and inclination for mischief or rapine. Like all knaves, they know how to conceal their intentions, to watch, wait, and choose opportunities for seizing their prey; to fly[Pg 37] from punishment, and to remain away until the danger is over, and they can return with safety. They readily conform to the habits of society, but never acquire its manners; for of attachment they have only the appearance, as may be seen by the obliquity of their motions, and duplicity of their looks. They never look in the face those who treat them best, and of whom they seem to be the most fond; but either through fear or falsehood, they approach him by windings to seek for those caresses they have no pleasure in, but only to flatter those from whom they receive them. Very different from that faithful animal the dog, whose sentiments are all directed to the person of his master, the Cat appears only to feel for himself, only to love conditionally, only to partake of society that he may abuse it; and by this disposition he has more affinity to man than the dog, who is all sincerity.”

So much for M. Buffon: though he is sadly mistaken on the subject of which he writes, these were probably his honest opinions; but what can be said for a writer in the Encyclopædia Britannica, who holds forth as follows, and is not only ignorant of what he talks about, but steals Buffon’s absurd prejudices, and passes them off as his own. In his[Pg 38] opinion the cat “is a useful but deceitful domestic. Although when young it is playful and gay, it possesses at the same time an innate malice and perverse disposition, which increases as it grows up, and which education learns it to conceal, but never to subdue. Constantly bent upon theft and rapine, though in a domestic state, it is full of cunning and dissimulation: it conceals all its designs, seizes every opportunity of doing mischief, and then flies from punishment. It easily takes on the habits of society, but never its manners; for it has only the appearance of friendship and attachment. This disingenuity of character is betrayed by the obliquity of its movements and the ambiguity of its looks. In a word, the Cat is totally destitute of friendship.”

Here, I think, are some pretty sentiments and some valuable information about the Cat-kind. Let us hope that the other contributors to the Encyclopædia knew something more of what they wrote about than the gentleman above quoted. And these opinions are not uncommon; for instance, allow me to quote from an article in a popular miscellany:—

“No! I cannot abide Cats,” says the writer. “Pet Cats, wild Cats, Tom Cats, gib Cats, Persian[Pg 39] Cats, Angora Cats, tortoiseshell Cats, tabby Cats, black Cats, Manx Cats, brindled Cats, mewing once, twice, or thrice, as the case may be,—none of these Cats delight me; they are associated in my mind with none but disagreeable objects and remembrances—old maids, witchcraft, dreadful sabbaths, with old women flying up the chimney upon broom-sticks, to drink hell-broth with the evil one, charms, incantations, sorceries, sucking children’s breaths, stopping out late on the tiles, catterwauling and molrowing in the night season, prowling about the streets at unseasonable hours, and a variety of other things, too numerous and too unpleasant to mention.”

Upon the other hand, Puss has had her defenders, and Miss Isabel Hill writes thus:—

“Poor Pinkey, I can scarce dare a word in praise of one belonging to thy slandered sisterhood; yet a few good examples embolden me to assert that I have rarely known any harm of Cats who were given a fair chance, though I own I have seldom met with any that have enjoyed that advantage. Is it their fault that they are born nearly without brains, though with all their senses about them, and of a tender turn? That they want strength, both of body and instinct, are dependant, and ill[Pg 40] educated? No! their errors are thrust upon them; they become selfish per force, cowards from their tenacious regard for that personal neatness which they so labour to preserve. Oh! that all females made such good use of their tongues! Cross from sheer melancholy, reflecting, in their starved and persecuted maturity, on the fondness lavished over the days in which they were pet useless toys; as soon as they can deserve and may require kind treatment, they are as ill-used as if they were constant wives—rather unfair on ladies of their excessive genius. Could every Cat, like Whittington’s, catch fortunes for her master as well as mice, we should hear no more said against the species. Suppose they only fawn on us because we house and feed them, they have no nobler proofs of friendship with which to thank us; and if their very gratitude for this self-interested hire be adduced as a crime, alas! poor Pussies! Had Minette been a Thomas, a whiskered fur-collared Philander, he would most probably have surmounted that unmanly weakness, and received all favours as but his due. I never see a Mrs. Mouser rubbing her soft coat against me, with round upturned eyes, but I translate her purr into words like these:—‘I can’t swim; I can neither fetch and carry, nor guard the house; I can[Pg 41] only love you, mistress; pray accept all I have to offer.’”

An anonymous writer says: “We may learn some useful lessons from Cats, as indeed, from all animals. Agur, in the book of Proverbs, refers to some; and all through Scripture we find animals used as types of human character. Cats may teach us patience, and perseverance, and earnest concentration of mind on a desired object, as they watch for hours together by a mouse-hole, or in ambush for a bird. In their nicely calculated springs, we are taught neither to come short through want of mercy, or go beyond the mark in its excess. In their delicate walking amidst the fragile articles on a table or mantel-piece, is illustrated the tact and discrimination by which we should thread rather than force our way; and, in pursuit of our own ends, avoid the injuring of others. In their noiseless tread and stealthy movements, we are reminded of the frequent importance of secresy and caution prior to action, while their promptitude at the right moment, warns us, on the other hand, against the evils of irresolution and delay. The curiosity with which they spy into all places, and the thorough smelling which any new object invariably receives from them, commends to us the pursuit of knowledge, even under[Pg 42] difficulties. Cats, however, will never smell the same thing twice over, thereby showing a retentive as well as an acquiring faculty. Then to speak of what may be learned from their mere form and ordinary motions, so full of beauty and gracefulness. What Cat was ever awkward or clumsy? Whether in play or in earnest, Cats are the very embodiment of elegance. As your Cat rubs her head against something you offer her, which she either does not fancy or does not want, she instructs you that there is a gracious mode of refusing a thing; and as she sits up like a bear, on her hind legs, to ask for something (which Cats will often do for a long time together), you may see the advantage of a winning and engaging way, as well when you are seeking a favour as when you think fit to decline one. If true courtesy and considerateness should prevent you not merely from positively hurting another, but also from purposely clashing, say, with another’s fancies, peculiarities, or predilections, this too, may be learned from the Cat, who does not like to be rubbed the wrong way (who does like to be rubbed the wrong way?), and who objects to your treading on her tail. Nor is the soft foot, with its skilfully sheathed and ever sharp claws, without a moral too; for whilst there is nothing[Pg 43] commendable in anything approaching to spite, passion, or revenge, a character that is all softness is certainly defective. The velvety paw is very well, but it will be the better appreciated when it is known that it carries within it something that is not soft, and which can make itself felt, and sharply felt, on occasion. A cat rolled up into a ball, or crouched with its paws folded underneath it, seems an emblem of repose and contentment. There is something soothing in the mere sight of it. It may remind one of the placid countenance and calm repose with which the sphynx seems to look forth from the shadow of the Pyramids, on the changes and troubles of the world. This leads to the remark, that Cats, after all, are very enigmatical creatures. You never get to the bottom of Cats. You will never find any two, well known to you, that do not offer marked diversities in ways and dispositions; and, in general, the combination they exhibit of activity and repose, and the rapidity with which they pass from the one to the other, their gentle aspects and fragile form, united with strength and pliancy, their sudden appearances and disappearances, their tenacity of life, and many escapes from dangers (“as many lives as a Cat”), their silent and rapid movements, their sometimes[Pg 44] unaccountable gatherings, and strange noises at night—all contribute to invest them with a mysterious fascination, which reaches its culminating point in the (not very frequent) case of a completely black cat.”

Instances are frequent, I am happy to tell Cat-haters, of illustrious persons who have been attached to the feline race, and of Cats who have merited such attachment.

Mahomet would seem to have been very fond of Cats, for it is said that he once cut off the sleeve of his robe rather than disturb his favourite while sleeping on it. Petrarch was so fond of his Cat that when it died he had it embalmed, and placed in a niche in his apartment; and you ought to read what Rousseau has to say in favour of the feline race. M. Baumgarten tells us that he saw a hospital for Cats at Damascus: it was a large house, walled round very carefully, and said to be full of patients. It was at Damascus that the incident above related occurred to Mahomet. His followers in this place ever afterwards paid a great respect to Cats, and supported the hospital in question by public subscriptions with much liberality.

When the Duke of Norfolk was committed to the Tower, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, a[Pg 45] favourite Cat made her way into the prison room by getting down the chimney.

“The first day,” says Lady Morgan, in her delightful book, “we had the honour of dining at the palace of the Archbishop of Toronto, at Naples, he said to me, ‘You must pardon my passion for Cats, but I never exclude them from my dining-room, and you will find they make excellent company.’ Between the first and second course, the door opened, and several enormously large and beautiful Angora Cats were introduced by the names of Pantalone, Desdemona, Otello, etc.: they took their places on chairs near the table, and were as silent, as quiet, as motionless, and as well behaved as the most bon ton table in London could require. On the bishop requesting one of the chaplains to help the Signora Desdemona, the butler stepped up to his lordship, and observed, ‘My lord, La Signora Desdemona will prefer waiting for the roasts.’”

Gottfried Mind, the celebrated Swiss painter, was called the “Cat Raphael,” from the excellence with which he painted that animal. This peculiar talent was discovered and awakened by chance. At the time when Frendenberger painted his picture of the “Peasant Clearing Wood,” before his cottage, with[Pg 46] his wife sitting by, and feeding her child out of a basin, round which a Cat is prowling, Mind, his new pupil, stared very hard at the sketch of this last figure, and Frendenberger asked with a smile whether he thought he could draw a better. Mind offered to show what he could do, and did draw a Cat, which Frendenberger liked so much that he asked his pupil to elaborate the sketch, and the master copied the scholar’s work, for it is Mind’s Cat that is engraved in Frendenberger’s plate. Prints of Mind’s Cats are now common.

Mind did not look upon Cats merely as subjects for art; his liking for them was very great. Once when hydrophobia was raging in Berne, and eight hundred were destroyed in consequence of an order issued by the civic authorities, Mind was in great distress on account of their death. He had, however, successfully hidden his own favourite, and she escaped the slaughter. This Cat was always with him when he worked, and he used to carry on a sort of conversation with her by gesture and signs. It is said that Minette sometimes occupied his lap, while two or three kittens perched on his shoulders; and he was often known to remain for an hour together in almost the same attitude for[Pg 47] fear of disturbing them; yet he was generally thought to be a passionate, sour-tempered man. It is said that Cardinal Wolsey used to accommodate his favourite Cat with part of his regal seat when he gave an audience or received princely company.

There is a funny story told of Barrett, the painter, another lover of Cats. He had for pets a Cat and a kitten, its progeny. A friend seeing two holes in the bottom of his door, asked him for what purpose he made them there. Barrett said it was for the Cats to go in and out.

“Why,” replied his friend, “would not one do for both?”

“You silly man,” answered the painter, “how could the big Cat get into the little hole?”

“But,” said his friend, “could not the little one go through the big hole?”

“Dear me,” cried Barrett, “so she could; well, I never thought of that.”

M. Sonnini had an Angora Cat, of which he writes: “This animal was my principal amusement for several years. How many times have her tender caresses made me forget my troubles, and consoled me in my misfortunes. My beautiful companion at length perished. After several days of suffering,[Pg 48] during which I never forsook her, her eyes constantly fixed on me, were at length extinguished; and her loss rent my heart with sorrow.”

You have heard, of course, of Doctor Johnson’s feline favourite, and how it fell ill, and how he, thinking the servants might neglect it, himself turned Cat-nurse, and having found out that the invalid had a fancy for oysters, daily administered them to poor Pussy until she had quite recovered. I like to picture to myself that good old grumpy doctor nursing Pussy on his knee, and wasting who shall say how many precious moments which otherwise might have been devoted to his literary avocations. I dare say now, in that tavern parlour where the lexicographer held forth so ably after sun-set, he made but scant allusion to his nursing feats, lest some mad wit might have twitted him upon the subject, for you may be sure that the wits of those days, as of ours, could have been mighty satirical on such a theme.

Madame Helvetius had a Cat that used to lie at its mistress’s feet, scarcely ever leaving her for five minutes together. It would never take food from any other hand, and it would allow no one but its mistress to caress it; but it would obey her commands in everything, fetching objects she[Pg 49] wanted in its mouth, like a dog. During Madame Helvetius’s last illness, the poor animal never quitted her chamber, and though it was removed after her death, it returned again next morning, and slowly and mournfully paced to and fro in the room, crying piteously all the time. Some days after its mistress’s funeral, it was found stretched dead upon her grave, having, it would seem, died of grief.

There is a well-authenticated story of a Cat which having had a thorn taken out of her foot by a man servant, remembered him, and welcomed him with delight when she saw him again after an absence of two years.

As a strong instance of attachment, I can quote the case of a she Cat of my own, which always waited for me in the passage when I returned home of an evening, and mounted upon my shoulder to ride upstairs. Returning home once after an absence of six weeks, this Cat sat on the corner of the mantel-piece, close by the bed, all night, and as it would appear wide awake, keeping a sort of guard over me, for being very restless I lay awake a long while, and then awoke again, several times, after dozing off, to find upon each occasion Miss Puss, with wide open eyes, purring loudly. I may add, that although, when we have gone away from home,[Pg 50] the Cats have taken their meals and spent most of their time with the servants, yet upon our return they have immediately resumed their old ways, and cut the kitchen dead.

By the report of a police case at Marlborough Street, on the 28th of June last, it appeared that a husband, brutally ill-using his wife, flung her on the ground, and seizing her by the throat, endeavoured to strangle her. While, however, she lay thus, a favourite Cat, named “Topsy,” suddenly sprang upon the man, and fastened her claws and teeth in his face. He could not tear the Cat away, and was obliged to implore the woman he had been ill-using to take the Cat from him to save his life.

The Cat is reproached with treachery and cruelty, but Bigland argues that the artifices which it uses are the particular instincts which the all-wise Creator has given it, in conformity with the purposes for which it was designed. Being destined to prey upon a lively and active animal like the mouse, which possesses so many means of escape, it is requisite that it should be artful; and, indeed, the Cat, when well observed, exhibits the most evident proofs of a particular adaptation to a particular purpose, and the most striking example of a peculiar instinct suited to its destiny.

[Pg 51]Every animal has its own way of killing and eating its prey. The fox leaves the legs and hinder parts of a hare or rabbit; the weasel and stoat eat the brains, and nibble about the head, and suck the blood; crows and magpies peck at the eyes; the dog tears his prey to pieces indiscriminately; the Cat always turns the skin inside out like a glove.

Mr. Buckland relates the case of a gamekeeper who bought up all the Cats in the neighbouring town, cut off their heads, and nailed them up as trophies of veritable captures in the woods. In a gamekeeper’s museum, visited by the same writer, were no less than fifty-three Cats’ heads staring hideously down from the shelves. There was a story attached to each head. One Cat was killed in such a wood; another in such a hedge-row; some in traps, some shot, some knocked on the head with a stick; but what was most remarkable was the different expression of countenance observable in each individual head. One had died fighting desperately to the last, and giving up its nine lives inch by inch. Caught in a trap, it had lingered the night through in dreadful agony, the pain of its entrapped limb causing it to make furious efforts to free itself, each effort but lending another torment to the wound.[Pg 52] In the morning the gamekeeper had released the poor exhausted creature for the dogs to worry out what little life was left in its body. The head dried by the heat of two summers, the wrinkled forehead, the expanded eyelids, the glary eyeballs, the whiskers stretched to their full extent, the spiteful lips, exposing the double row of tiger-like teeth, envenomed by agony, told all this. The hand of death had not been powerful enough to relax the muscles racked for so many hours of pain and terror.

Another Cat’s head wore a very different expression; she had neither been worried nor tortured. Creeping, stealthily, on the tips of her beautifully padded feet, behind some overhanging hedge, the hidden gamekeeper had suddenly shot her dead. In death her face was calm; no expression of fear ruffled her features; she had been shot down and died instantly at the moment of anticipated triumph.

A third head belonged to a poor little Puss that had died before it had attained the age of cathood; her young life had been knocked out of her with a stick: her head still retained the kitten’s playful look, and there was an appealing expression about it as though it had died quickly, wondering in what it had done wrong.

[Pg 53]I find a writer upon Cats who speaks thus in their praise:—

“It has been said that the Cat is one of those animals which has made the least return to man for his trouble by its services; but it is certain that it renders very essential service to man.”

And another says:—

“Authors seem to delight in exaggerating the good qualities of the Dog, while they depreciate those of the Cat; the latter, however, is not less useful, and certainly less mischievous, than the former.”

Indeed, it would be unfair not to state that Pussy has had many able defenders, who have argued her case in verse as well as prose; for example, in Edmond Moore’s fable of “The Farmer, the Spaniel and the Cat” the Spaniel, when Puss drew near to eat some of the fragments of a feast, repelled her, saying she does nothing to merit being fed, etc.:—

“‘I own’ (with meekness Puss replied)

‘Superior merit on your side;

Nor does my breast with envy swell

To find it recompens’d so well.

Yet I, in what my nature can,

Contribute to the good of man.

Whose claws destroy the pilf’ring mouse?

Who drives the vermin from the house?

[Pg 54]Or, watchful for the lab’ring swain,

From lurking rats secures the grain?

For this, if he rewards bestow,

Why should your heart with gall o’erflow?

Why pine my happiness to see,

Since there’s enough for you and me?’

‘Thy words are just,’ the Farmer cried,

And spurned the Spaniel from his side.”

And, again, the same idea occurs in Gay’s fable of the “Man, the Cat, the Dog, and the Fly.” The Cat solicits aid from the Man in the social state.

“‘Well, Puss,’ says Man, ‘and what can you

To benefit the public do?’

The Cat replies, ‘These teeth, these claws,

With vigilance shall serve the cause.

The Mouse, destroy’d by my pursuit,

No longer shall your feasts pollute;

Nor Rats, from nightly ambuscade,

With wasteful teeth your stores invade.’

‘I grant,’ says Man, ‘to general use

Your parts and talents may conduce;

For rats and mice purloin our grain,

And threshers whirl the flail in vain;

Thus shall the Cat, a foe to spoil,

Protect the farmers’ honest toil.’”

Mr. Ruskin says, “There is in every animal’s eye a dim image and gleam of humanity, a flash of strange life through which their life looks at and up to our great mystery of command over them, and[Pg 55] claims the fellowship of the creature, if not of the soul!”

Poor Pussy! on the whole she has had but few champions in comparison to the number of her foes. Let us see what anecdotes we can find which will show her in a favourable light; but my chapter is long enough, and I will conclude it with the epitaph placed over a favourite French Puss:—

“Ci repose pauvre Mouton,

Qui jamais ne fût glouton;

J’espère bien que le roi Pluton,

Lui donnera bon gîte et crouton.”

Of the Manners and Customs of Cats.

et us see though, before we try our anecdotes, what is known of the Cat’s

peculiarities. I rather like this quaint description of the domestic

Pussy, which occurs in an old heraldic book, John Bossewell’s “Workes of

Armorie,” published in 1597:—

et us see though, before we try our anecdotes, what is known of the Cat’s

peculiarities. I rather like this quaint description of the domestic

Pussy, which occurs in an old heraldic book, John Bossewell’s “Workes of

Armorie,” published in 1597:—

“The field is of the Saphire, on a chief Pearle, a Masion Cruieves. This beaste is called a ‘Masion,’ for that he is enimie to Myse and Rattes. He is[Pg 60] slye and wittie, and seeth so sharpely that he overcommeth darkness of the nighte by the shyninge lyghte of his eyne. In shape of body he is like unto a Leoparde, and hathe a greate mouthe. He doth delighte that he enjoyeth his libertie; and in his youth he is swifte, plyante, and merye. He maketh a rufull noyse and a gastefulle when he profereth to fighte with another. He is a cruell beaste when he is wilde, and falleth on his owne feete from moste highe places: and never is hurt therewith. When he hathe a fayre skinne, he is, as it were, proude thereof, and then he goethe muche aboute to be seene.”

It is commonly supposed that a Cat’s scratch is venomous, because a lacerated wound oftener festers than a smooth cut from a sharp knife.

It is erroneously said that Cats feel a cutaneous irritation at the approach of rain, and offer sensible evidence of uneasiness: allusion may be found to this in “Thomson’s Seasons.” Virgil has also made the subject a theme for poetic allusion.

The Chinese look into their Cat’s eyes to know what o’clock it is; and the playfulness of Cats is said to indicate the coming of a storm. I have noticed this often myself, and have seen them rush about in a half wild state just before windy weather.[Pg 61] I think it is when the wind is rising that they are most affected.

It is stated in a Japanese book that the tip of a Cat’s nose is always cold, except on the day corresponding with our Midsummer-day. This is a question I cannot say I have gone into deeply. I know, however, that Cats always have a warm nose when they first awaken from sleep. All Cats are fond of warmth. I knew one which used to open an oven door after the kitchen fire was out, and creep into the oven. One day the servant shut the door, not noticing the Cat was inside, and lighted the fire. For a long while she could not make out whence came the sounds of its crying and scratching, but fortunately made the discovery in time to save its life. A Cat’s love of the sunshine is well known, and perhaps this story may not be unfamiliar to the reader:—

One broiling hot summer’s day Charles James Fox and the Prince of Wales were lounging up St. James’s street, and Fox laid the Prince a wager that he would see more Cats than his Royal Highness during their promenade, although the Prince might choose which side of the street he thought fit. On reaching Piccadilly, it turned out that Fox had seen thirteen Cats and the Prince none. The[Pg 62] Prince asked for an explanation of this apparent miracle.

“Your Royal Highness,” said Fox, “chose, of course, the shady side of the way as most agreeable. I knew that the sunny side would be left for me, and that Cats prefer the sunshine.”

Cats usually, but not always, fall on their feet, because of the facility with which they balance themselves when springing from a height, which power of balancing is in some degree produced by the flexibility of the heel, the bones of which have no fewer than four joints. Cats alight softly on their feet, because in the middle of the foot is a large ball or pad in five parts, formed of an elastic substance, and at the base of each toe is a similar pad. No mechanism better calculated to break the force of a fall could be imagined.

A Cat, when falling with its head downwards, curls its body, so that the back forms an arch, while the legs remain extended. This so changes the position of the centre of gravity, that the body makes a half turn in the air, and the feet become lowest.

In the inside of a Cat’s head there is a sort of partition wall projecting from the sides, a good way inwards, towards the centre, so as to prevent the brain from suffering from concussion.

[Pg 63]There is a breed of tail-less white Cats in the Isle of Man, and also in Devonshire. These are not the sort of animals with which, on shipboard, the “stow-aways” are made acquainted.

A great many Cats in the Isle of Man are said to be deaf. Thus, “As deaf as a Manx Cat.” There is an idea that white Cats with blue eyes are always deaf, but a correspondent of Notes and Queries says, “I am myself possessed of a white Cat which, at the advanced age of upwards of seventeen years, still retains its hearing to great perfection, and is remarkably intelligent and devoted, more so than Cats are usually given credit for. Its affection for persons is, indeed, more like that of a dog than of a Cat. It is a half-bred Persian Cat, and its eyes are perfectly blue, with round pupils, not elongated, as those of Cats usually are. It occasionally suffers from irritation in the ears, but this has not at all resulted in deafness.”

Do you know why Cats always wash themselves after a meal? A Cat caught a sparrow, and was about to devour it, but the sparrow said,

“No gentleman eats till he has first washed his face.”

The Cat, struck with this remark, set the sparrow down, and began to wash his face with his paw, but[Pg 64] the sparrow flew away. This vexed Pussy extremely, and he said,

“As long as I live I will eat first and wash my face afterwards.”

Which all Cats do, even to this day.

A French writer says, the three animals that waste most time over their toilet are cats, flies, and women.

The attitudes and motions of a Cat are very graceful, because she is furnished with collar-bones. She can, therefore, carry food to her mouth like a monkey, can clasp, can climb, and can strike sideways, and seat herself at a height upon a very narrow space.

The lateral movements of the head in Cats are not so extensive as in the owl, but are, nevertheless, considerable. A cat can look round pretty far behind it without moving its body, which might be apt to startle its prey. The spine of the Cat is very full and loose, in order that all its movements in all possible directions and circumstances may be free and unrestrained. For this purpose, too, all the joints which connect its bones together are extremely loose and free. Thus, the Cat is enabled to get through small apertures, to leap from great heights, and even to fall in an unfavourable posture[Pg 65] with little or no injury to itself. Its ears are not so moveable as those of some other animals, but are more so than in very many animals. The shape of the external ear, or rather cartilaginous portion, is admirably adapted to intercept sounds. The natural posture is forward and outward, so as to catch sounds proceeding from the front and sides. The upper half, however, is moveable, and by means of a thin layer of muscular fibres, it is made to curve backwards and receive sounds from the rear. Although a Cat cannot lick its face and head, it nevertheless cleans these parts thoroughly; in fact, as we often observe, a Cat licks its right paw for a long time, and then brushes down the corresponding side of the head and face; and when this is accomplished, it does the same with the other paw and corresponding side.

“‘A May kitten makes a dirty Cat,’ is a piece of Huntingdonshire folk-lore,” says Mr. Cuthbert Bede, “quoted to me in order to deter me from keeping a kitten that had been born in May.”

Dr. Turton says, “The Cat has a more voluminous and expressive vocabulary than any other brute; the short twitter of complacency and affection, the purr of tranquility and pleasure, the mew of distress, the growl of anger, and the horrible[Pg 66] wailing of pain.” For myself, I seldom hear a catawauling without thinking of that droll picture in Punch of the old lady sitting up in bed and pricking up her ears to the music of a mewing Cat.

“Oh, ah! yes, it’s the waits,” says she, with a delighted chuckle; “I love to listen to ’em. It may be fancy, but somehow they don’t seem to play so sweetly as they did when I was a girl. Perhaps it is that I am getting old, and don’t hear quite so well as I used to do.”

Few, even amongst Pussy’s most ardent admirers, who possess the faculty of hearing, and have heard the music of Cats, would desire the continuance of their “sweet voices”; yet a concert was exhibited at Paris, wherein Cats were the performers. They were placed in rows, and a monkey beat time to them, as the Cats mewed; and the historian of the facts relates that the diversity of the tones which they emitted produced a very ludicrous effect. This exhibition was announced to the Parisian public by the title of “Concert Miaulant.”

This would seem to prove that Cats may be taught tricks, which is not generally believed, but is nevertheless the case.

In Pool’s Twists and Turns about the Streets of[Pg 67] London, mention is made of “a poor half-naked boy, strumming a violin, while another urchin with a whip makes two half-starved Cats go through numerous feats of agility.”

De Roget says, that in animals that graze and keep their heads for a long time in a dependent position, the danger from an excessive impetus in the blood flowing towards the head is much greater than in other animals; and we find that an extraordinary provision is made to obviate this danger. The arteries which supply the brain on their entrance into the basis of the skull suddenly divide into a great number of minute branches, forming a complicated network of vessels, an arrangement which, on the well known principle of hydraulics, must greatly check the velocity of the blood conducted through them. That such is the real purpose of this structure, which has been called the rete mirabile, is evident from the branches afterwards uniting into larger trunks when they have entered the brain, through the substance of which they are then distributed exactly as in other animals, where no such previous subdivision takes place. The rete mirabile is much developed in the sheep, but scarcely perceptible in the Cat.

Being an animal which hunts both by day and[Pg 68] night, the structure of its visual organs is adjusted for both. The retina, or expansion of the optic nerve, is most sensitive to the stimulus of light; hence, a well-marked ciliary muscle contracts the pupil to a mere vertical fissure during the day, while in the dark, the pupil dilates enormously, and lets in as much light as possible. But even this would be insufficient, for Cats have to look for their prey in holes, cellars, and other places where little or no light can penetrate. Hence, the Cat is furnished with a bright metal-like, lustrous, membrane, called the Tapetum, which lines part of the hollow globe of the eye, and sheds considerable light on the image of an object thrown on the retina. This membrane is, we are told, common to all vertebrated animals, but is especially beautiful and lustrous in nocturnal animals. The herbivora, such as the ox and sheep, have the tapetum of the finest enamelled green colour, provided probably to suit the nature of their food, which is green. The subject, however, of the various colours of the tapetum in different animals is not yet understood. The sensibility of the retina in Cats is so great that neither the contractions of the pupil nor the closing of the eye-lids would alone afford them sufficient protection from the action of the light. Hence,[Pg 69] in common with most animals, the Cat is furnished with a nictitating membrane, which is, in fact, a third eyelid, sliding over the transparent cornea beneath the common eyelids. This membrane is not altogether opaque, but translucent, allowing light to fall on the retina, and acting, as it were, like a shade. The nictitating membrane is often seen in the Cat when she slowly opens her eyes from a calm and prolonged sleep: it is well developed in the eagle, and enables him to gaze steadfastly on the sun’s unclouded disk.

The illumination of a Cat’s eye in the dark arises from the external light collected on the eye and reflected from it. Although apparently dark, a room is penetrated by imperceptible rays of external light from lamps or other luminiferous bodies. When these rays reach the observer direct, he sees the lamps or luminiferous bodies themselves, but when he is out of their direct sight, the brightness of their illumination only becomes apparent, through the rays being collected and reflected by some appropriate substance.

The cornea of the eye of the Cat, and of many other animals, has a great power of concentrating the rays and reflecting them through the pupil. Professor Bohn, at Leipsic, made experiments[Pg 70] proving that when the external light is wholly excluded, none can be seen in the Cat’s eye. For the same reason, the animal, by a change of posture or other means, intercepting the rays, immediately deprives the observer of all light otherwise existing in, or permeating, the room. In this action, when the iris of the eye is completely open, the degree of brilliancy is the greatest; but when the iris is partly contracted, which it always is when the external light, or the light in the room, is increased, then the illumination is more obscure. The internal motions of the animals have also great influence over this luminous appearance, by the contraction and relaxation of the iris dependent upon them. When the animal is alarmed, or first disturbed, it naturally dilates the pupil, and the eye glares; when it is appeased or composed, the pupil contracts, and the light in the eye is no longer seen.

A German savant says, that at the end of each hair of a Cat’s whiskers is a sort of bulb of nervous substance, which converts it into a most sensitive feeler. The whiskers are of the greatest use to her when hunting in the dark. The nervous bulbs at the ends of a lion’s whiskers are as large as a small pea.

[Pg 71]But an English writer differs from him; thus:—

“Every one must have observed what are usually called the “whiskers” on a Cat’s upper lip. The use of these, in a state of nature, is very important. They are organs of touch; they are attached to a bed of close glands under the skin; and each of these long and stiff hairs is connected with the nerves of the lip. The slightest contact of these whiskers with any surrounding object is thus felt most distinctly by the animal, although the hairs are of themselves insensible. They stand out on each side in the lion, as well as in the common Cat; so that, from point to point, they are equal in width to the animal’s body. If we imagine, therefore, a lion stealing through a covert of wood in an imperfect light, we shall at once see the use of these long hairs. They indicate to him, through the nicest feeling, any obstacle which may present itself to the passage of the body: they prevent the rustle of boughs and leaves, which would give warning to his prey if he were to attempt to pass through too dense a bush, and this, in conjunction with the soft cushions of his feet, and the fur upon which he treads (the retractable claws never coming in contact with the ground), enable him to move towards his victim with a stillness even[Pg 72] greater than that of the snake, who creeps along the grass, and is not perceived till he is coiled round his prey.”

Black Cats especially are said to be highly charged with electricity, which, when the animal is irritated, is easily visible in the dark. Here are directions I have for producing the effect:—Lay one hand upon the Cat’s throat, and slightly press its shoulder bones. If the other hand be drawn gently along its back, electric shocks will be felt in the hand upon the Cat’s throat. If the tips of the ears be touched after the back has been rubbed, shocks of electricity may also be felt, or they may be obtained from the foot. Lay the animal upon your knees, and apply the right hand to the back, the left fore paw resting on the palm of your left hand, apply the thumb to the upper side of the paw, so as to extend the claws, and by this means bring your fore finger in contact with one of the bones of the leg, where it joins the paw; when from the knob or end of this bone, the finger slightly pressing on it, you may feel distinctly successive shocks similar to those obtained from the ears. The Reverend Mr. Wood expresses an opinion, that on account of the superabundance of electricity which is developed in the Cat, the animal is found[Pg 73] very useful to paralysed persons, who instinctively encourage its approach, and from the touch derive some benefit. Those who suffer from rheumatism often find the presence of a Cat alleviate their sufferings. The same gentleman, writing of a favourite Cat, says, that if a hair of her mistress’s head were laid upon the animal’s back it would writhe as though in agony, and rolling on the floor, would strive to free herself from the object of her fears. The pointing of a finger at her side, at a distance of half a foot, would cause her fur to bristle up and throw her into a violent tremour.