WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

COPYRIGHT.

The right of reproduction is reserved.

London:

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & Co., Limited,

PATERNOSTER ROW.

Devonport:

A. H. SWISS, Printer and Stationer,

111 & 112 Fore Street.

LORAL

LORAL

SPOONER & COMPANY.

FLOOR COVERINGS.

S. & Co. beg to draw the attention of their customers to the large portion of their premises reserved for the exclusive sale of the above, necessitated by the ever increasing variety of

BRITISH & ORIENTAL FLOOR COVERINGS,

and for the development of which Spooner & Co. have given their special attention, resulting in their having always on sale an unrivalled selection of

AXMINSTERS, WILTONS,

BRUSSELS, TAPESTRY CARPETS,

KIDDERMINSTER CARPETS,

FLOOR CLOTHS,

LINOLEUMS, CORK CARPETS.

Fully maintaining their reputation for Superior Designs, Durability, and excellence of Material.

SPOONER & COMPANY,

Complete House Furnishers and Art Decorators,

PLYMOUTH.

The record of the Blizzard of 1891 was undertaken in response to a generally expressed desire on the part of a large number of residents in the Western Counties.

It would have been impossible to compile the work, imperfect as it is, without the assistance and co-operation of the editor and staff of the Western Morning News, who have been most active in its promotion. Assistance has also been kindly rendered by the editor and staff of the Western Daily Mercury.

Thanks are also largely due to many others, who, besides furnishing us with interesting details and views, have offered us every facility for obtaining information.

Valuable particulars in some instances have been afforded by Dr. Merrifield, of Plymouth, and Mr. Rowe, public librarian, of Devonport, who has also sent some of the views appearing in this book.

To the artistic photographic skill of Messrs. Heath and Son, of George Street, Plymouth, Messrs. Denney and Co., of Exeter and Teignmouth, and Messrs. Valentine and Son, of Teignmouth, we are indebted for several of our illustrations. To the amateur photographers in various parts of the West who so kindly sent photographic views we tender our best thanks, and regret that space did not permit us to use a larger number.

Much necessarily remains untold, but we have endeavoured to depict a very remarkable event as fully as the pages at our disposal permitted.

Devonport, April, 1891.

On the morning of the 9th of March, 1891, when inhabitants of the three westernmost counties in England set about preparing for the routine duties of daily life, nothing seemed to indicate that, with the approach of nightfall, the gravest atmospheric disturbance of the century—in that part of the world, at all events—would come to spread terror and destruction throughout town and country. The month, so far, had not been a gentle one. Following in the footsteps of a memorably genial February, March had been somewhat harsh and cold, without yielding the rain that was by this time greatly needed. There were rumours of "a change of some sort," of an approaching "fall of something," and other vaticinations of the same familiar character floating about, but in the west country these wise sayings fall so thick and fast and frequently as to possess little more significance than the most oft-repeated household words. When the day drew on, and signs of a rising gale were uncomfortably apparent on every hand, recollections of a[2] promised storm from the Observatories of the United States began to be awakened, but it was found on sifting the matter, that if this were the disturbance indicated, it had come about a fortnight too soon. Students of "Old Moore's Almanack" were better informed, and it is probable that if this ill wind blew good to anybody, it was in the shape of discovery that by virtue of the truth of his forecast, a favourite and venerable prophet was deserving of honour at the hands of the people of his own country. Unhappily, however, there is nothing to show that advantage had been taken of this warning, in any practical sense. On the contrary, the blast came down swiftly upon a community that was almost wholly unprepared to receive it, and one of the saddest parts of the story of its fury will be the account of the devastation wrought among the unprotected flocks and herds.

On referring to the remarks on the subject of the weather published in the local press, and obtained from official scientific authorities, it will be found that at an early hour on the morning of March 9th the barometer had been rising slightly, and that the day "promised to be fine." Other accounts hinted at the probability of some snow showers, and snow was reported as falling heavily in North Wales, but north and north-easterly winds, light and moderate, were anticipated. Nothing was said about a great fall of snow, accompanied by a hurricane fierce enough to send it down in powder, without even allowing time for the formation of snow-flakes.

According to one Plymouth correspondent, whose observations are both reliable and valuable, the only intimation of the coming storm was by the barometer[3] falling to 29·69 on the evening of the 9th, with an E.N.E. wind. The hygrometer was thick and heavy—a sign of rough weather. During the night the glass fell to 29·39. On Tuesday it fell to 29·180. Another account says that it has not, perhaps, occurred in the experience of many, except those who have known tropical storms, that the movement in an ordinary column barometer might be seen during the progress of a gale. Such, however, was possible in the case under notice. Though the glass had been falling during the day, yet there were no indications of any serious disturbance of the weather. On many occasions there have been greater falls in the barometer than on this occasion. When this storm was at its height, the barometer at Devonport was observed to be at 29·27, but in the course of half an hour pressure was indicated by 29·20, the rise being, of course, a considerable and sudden one. Within an hour of this register being made, a fall had again occurred to 29·25, and even a little below this was marked, at which point the column remained until the early hours of the morning.

It is clear that during the whole progress of the storm the temperature was never very low. The great cold came from the strength of the wind. During the storm, and in the course of the severe days that followed, not more than five or six degrees of frost were registered, and on one day of the week, when there was snow on every hand, the thermometer never rose higher than freezing point. The wind, however, was terrific, its maximum force during the night being 10, and 12 is the highest possible. To this extraordinary velocity is due the fact that the visitation is best describable by the[4] term "blizzard." With a less violent wind, there would have been a great fall of snow, as great probably as that of January, 1881, when difficulties and disasters painfully comparable with those of the present year were spread broadcast over not only the western portion, but the whole of England, but it would have been a snowstorm and not a blizzard, and many of the phenomenal aspects of the visitation under notice would have been absent. In the course of the present narrative many remarkable effects due to the powdery nature of the snow will have to be recorded. Before concluding the meteorological portion of the subject, and getting on with the story, it may be well to observe that according to the best authorities a blizzard is caused by the fierceness of the wind, which blows the cold into the vapour in the atmosphere and consolidates it into fine snow without allowing time for the formation of a snow-flake. We are accustomed to associate ideas of gentleness and beauty and stillness with the fall of snow. The blizzard, which is apparently—but, of course, only in name—a new acquaintance, shews us the reverse side of the picture, and suggests nothing beyond merciless fury and destructiveness.

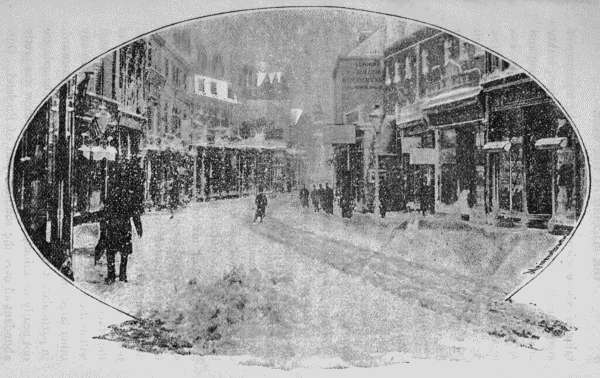

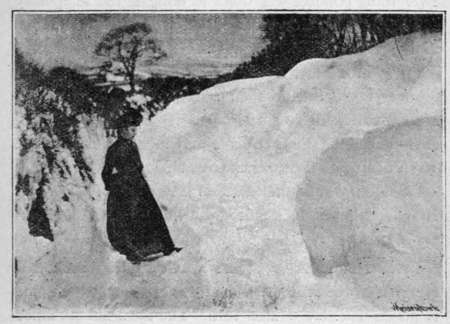

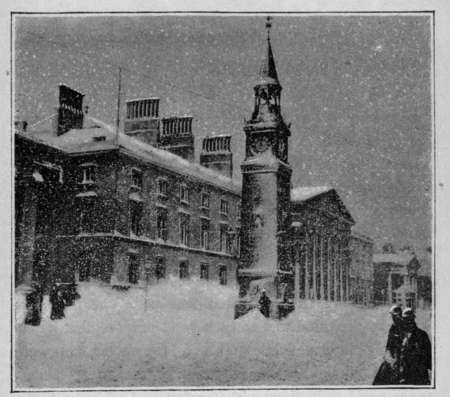

As to the quantity of snow that fell, accounts differ. There were huge drifts in most places; in others there was a comparatively level covering of many feet in thickness. The condition of a part of George Street, Plymouth, which received a very fair quantity, is artistically portrayed in the accompanying illustration, copied from a photograph taken on the morning of Tuesday by Mr. Heath, photographer, of Plymouth. According to observations made by Dr. Merrifield, of Plymouth, the[5] value of whose scientific researches into the mysteries of matters meteorological are beyond question, the quantity of snow and rain that fell between Monday evening and early on Wednesday morning was ·68. This was registered at the doctor's residence, which stands 125 feet above the level of the sea, and faces S.S.E. With the depth of snow in other places, this record will deal in due course.

During the whole time the blizzard was raging, the wind varied from N.E. to S.E. The changes were very rapid, but this was the widest range. Along the coast the greatest severity appears to have been experienced from a point or two eastward of Teignmouth to Falmouth Bay, many towns exposed to the sea having to bear their share of the burden, and unhappily many valuable lives being lost through disastrous wrecks. If a map of the three counties of Devon, Cornwall, and Somerset be consulted, it will be found that, taking this portion of the coast as an opening through which the broad shaft of a hurricane entered, now sweeping in a north-easterly, and now in a south-easterly direction, the area of country that has sustained the heaviest damage will be embraced, the intensity of the violence inflicted gradually diminishing the further one travels towards the east, north, and west. Dartmoor forms a kind of centre of the chief scene of desolation, and Plymouth, being well within the range, has suffered far more severely than any other large town in the three counties. To the eastward, in particular, it is clear that the effects of the gale are not nearly so serious, though the fall of snow was pretty abundant all over the southern part of England. Outside[7] of Devon and West Cornwall there are no great lots of timber down, though here and there a fallen tree is observable.

Unhappily the departure of the storm was not so sudden as its advent. The Tuesday following the night of tempest was an indescribably wretched day, and the barometer fell to 29·180. Wednesday brought sunshine and hope with it, and afforded the one bright spot in this gloomy record by showing up many effects of wonderful beauty in the snow-covered landscapes. Still the wind was never at rest, though the thermometer went up to 120° in the sun. Thursday followed with more snow, and occasional sharp and ominous squalls, and some apprehension was felt that a repetition of Monday's experience was in the air, but fortunately the week wore away without further calamity, and the work of repairing to some extent the damage done, and thereby making existence for man and beast possible, a task hitherto carried on under tremendous difficulties, was vigorously pushed forward.

A letter, which will be found interesting, was, on the day after the storm, written to the editor of the Western Morning News, and published in that paper, by Captain Andrew Haggard, of the King's Own Scottish Borderers, now stationed at Devonport. The writer is a brother of Mr. Rider Haggard, and himself a novelist of repute. This letter was as follows:—

"Sir,—The cyclonic nature of the blizzard that has been annoying us all so much, and causing such a frightful amount of damage during the last two days, may be judged by the following observations taken by several [8]officers in the South Raglan Barracks on the evening of the 9th instant. From these observations it would seem as if for a time the South Raglan Barracks were in the exact centre of the storm, being left for varying periods in a complete calm in consequence. Here are the notes we made:—At 8·12 P.M. the storm was raging so furiously that the solid old Raglan was shaken to its foundations, the fire was roaring up the chimney as if in a blast furnace, and the noise made by the blizzard generally was such that it was difficult to hear one's neighbour speak. But at 8·13 suddenly came a complete lull. The elements ceased to wage war, the fire assumed its normal demeanour, and an officer who went out to see what had happened came in and reported that it was so calm he was able to light matches outside. For thirteen minutes did this calm last. At 8·26 with a roar like thunder, the wind returned, and once more we were dreading that the armies of the chimney pots would fall upon us in their fury. Only for twenty minutes, though, did the hurricane scream and yell, and as before make itself generally obnoxious. At 8·46 there was another absolute cessation of wind until 8·53, when it 'blizzed' worse than before. And shortly afterward everyone started forth to put out fires, when all the amateur meteorologists discovered to their grief that whatever the cyclone might do in the way of lulling occasionally down at the Raglan, on the top of Stoke Hill it blizzed all night with perfect impartiality.

Yours truly,

"Andrew Haggard.

"Devonport, March 10th."

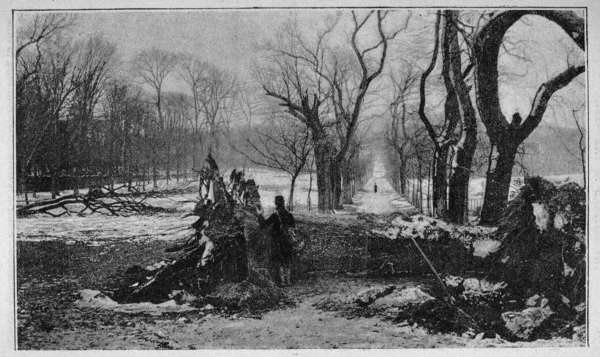

Soon after daylight, on the morning of Monday, March 9th, over the whole of the West of England, the fine weather that had prevailed for several weeks past gave place to a most unpleasant condition of affairs. The temperature fell, almost suddenly, and in the neighbourhood of Plymouth, Devonport, and Stonehouse, snow was falling fitfully from about an hour before noon. There was a gradually rising wind, that assumed menacing proportions as the afternoon wore on, while the snow that had, for the first few hours, thawed as soon as it fell upon the yet warm ground, was rapidly forming a white covering on every position exposed to the sky. At six o'clock, in the three towns some four or five inches of snow lay upon the ground, and the wind had increased to a hurricane. Slates began to start from the roofs of houses, and chimneys to fall, and in a very short time the streets assumed a deserted appearance, and all vehicular traffic was stopped. Advertisement hoardings were hurled from their positions with some terrible crashes, and in many instances the splinters were promptly seized by a thrifty populace and taken away for firewood. Many trees were blown down in the early part of the night. In Buckland Street, Plymouth, a tree[10] of sufficient size to block the roadway fell at about eight o'clock, and not long after another heavy tree fell from Athenæum Garden across Athenæum Street, the main road to the Great Western Railway Station, completely closing the thoroughfare. Our illustration, reproduced from a photograph taken by Mr. Heath of George Street, Plymouth, on the morning after the storm, gives a realistic idea of the condition of Plymouth streets, and of the quantity of snow that was blown about during the night.

On Plymouth Hoe, iron seats were blown from their fastenings and rolled over and over, the ironwork in many instances being curiously bent. The statue of Drake, the Armada Memorial, and the Smeaton Tower looked, however, none the worse for the wild night. Perhaps, when the sun shone upon them on Wednesday they may be described as having looked better for the patches of glistening snow that clung to them in most picturesque form. Strange to say, the Pavilion Pier sustained no damage beyond a smashed pane or two of glass. Exposed as it must have been to the full fury of the gale, it stood the turmoil gallantly, and this fact speaks well for the soundness of the structure, and for the good workmanship and material used in its erection.

Trees were uprooted or snapped short off at Woodside, the residence of Mr. Bewes, at Portland Square, and in many other parts of Plymouth. Of these irreparable losses much more will be said in the course of this record. Concerning the damage wrought among houses and homesteads, and the marvellous escapes from injury to life and limb, our limited pages would not permit of[11] the chronicling of one hundredth part of those that were met with in the Three Towns alone during that night. At Clifton Place, Plymouth, a chimney fell through the roof into a bedroom occupied by three little girls, and completely buried them, two being so badly injured as to necessitate their removal to the hospital. In this instance the staircase was blocked by the débris, and access to the terrified children could only be obtained by means of ladders, and with the greatest difficulty.

On Mutley Plain, one of the most exposed situations in Plymouth, the storm raged with terrific fury, women and children being blown off their feet and half-suffocated with the rush of snow-laden wind, while such cabmen as had ventured abroad with their cabs, made their way back to more sheltered quarters with great difficulty. Numerous instances in this locality of strong men receiving severe contusions through being blown against walls and railings are recorded. At Alexandra Place, Mutley, a terrific gust of wind caught one of the chimneys of the house, sending it through the roof, and the only means of rendering the house habitable for the time was by stretching tarpaulins over the breach. There is no statement accessible of the number of fallen chimneys and damaged roofs that might have been discovered in the Three Towns alone during that night, and even if there were, to recount them all would only be to tell one sad story over and over again with wearisome monotony; but it is probably safe to say that scarcely one street in the whole of the district escaped without some house receiving injury. Fortunately the storm was at its height at about 8 o'clock in the evening, an hour when bedrooms[13] are usually unoccupied. Had the chief fury of the gale been spent some hours later, it is more than likely that numerous fatalities would have had to be recounted.

At a shop in Fore Street, Devonport, a similar accident occurred, two children while lying in bed being badly crushed through a chimney falling. At the Main Guard, at the top of Devonport Hill, the windows were blown in, but the soldiers on duty fortunately escaped without injury, and were removed into the barracks. The roofs of the "Crown and Column," and of the wine and spirit store in the occupation of Messrs. Chubb & Co., both in Devonport, were seriously injured, while at Wingfield Villa, Stoke, the residence of the rector of Stoke Damerel, soon after 8 o'clock, a terrific squall burst upon the house and sent a large chimney stack crashing through the roof into the drawing room, doing great damage to some valuable furniture. Altogether, a lengthy chapter of accidents might be recorded as the result of the gale on Monday evening in Devonport. In a few instances personal injuries of a more or less serious nature were sustained, but it is not a little remarkable, that here, as elsewhere in the immediate neighbourhood, while there were many narrow escapes no case of a fatal character occurred.

Among other narrow escapes at Devonport may be instanced that of a gentleman living in Albert Road, Morice Town. He went to a back bedroom on the top storey to nail up a board to prevent smoke from blowing down the chimney, when a sudden gust struck the stack and precipitated it on to the roof, which fell through[14] the ceiling into the bedroom, burying him and carrying a portion of the floor into the back drawing-room below. The gentleman in question managed to extricate himself from the débris, and escaped with a severe shaking. In another case, a family occupying two rooms at the top of an old house in Cannon Street, nearly lost their lives. The occupier, his wife, and mother-in-law, were sitting around the bedroom fire when the roof fell on them. Their injuries were not of a serious character, but considerable damage was done to their furniture. It is estimated that about £50 worth of damage was done to the buildings at the back of Hope (Baptist) Chapel in Fore Street; a chimney falling bodily crashed through the roof, and carried one of the class-rooms and the gallery of the Sunday-school into the vestry. A chimney stack falling from No. 7, Chapel Street, destroyed a conservatory, and did considerable damage to the roof of the adjoining house, No. 6. A large portion of the roof of the South Devon Sanitary Laundry, Cornwall Street, was blown away, and the work of the establishment was temporarily disarranged in consequence. Extensive damage was also done to property at 10, Stopford-place, Stoke.

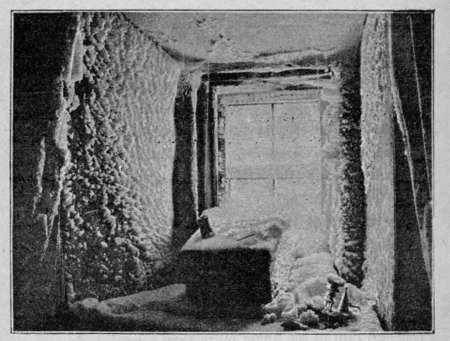

One of the most miraculous escapes that occurred was that at the residence of Mr. Perkins (Lord Mount-Edgecumbe's surveyor) in Emma Place, Stonehouse. During the hurricane Mrs. Perkins heard the windows and doors rattling, and rushed up to the nursery to see that the windows were closed and doors fastened. The servant was closing the window, her mistress standing near the chimney breast, when there was a sudden crash. The servant clung to the framework of the window, but[15] Mrs. Perkins immediately found herself buried in bricks and mortar. She was sitting on a portion of the floor near the window, with her legs dangling over an abyss; the floors having been carried away, with the exception of two floor boards, upon which, happily, she had been deposited. The snow found its way into the house, and although no one could distinguish her or the servant, she seems to have grasped the situation and called to her husband to bring a ladder to release her and the girl. This eventually was done, but the intense excitement of the moment may be well imagined. Mr. Perkins, having obtained a ladder and a light had the greatest difficulty in discovering the position of those above, but having done so, he released both from their perilous position, little thinking that the ladder was resting on fallen rubbish, the slightest shock to which would have precipitated all to the basement.

During this night of disaster, probably the most calamitous incident that occurred on land, was a fire which broke out at about 8 o'clock at 4, Wingfield Villas, Stoke, the residence of Mr. Venning, Town Clerk of Devonport, and which resulted in the total destruction of the house and its contents, as well as in material damage to the adjoining villa. A chimney-stack facing the direction from which the wind blew gave way and, crashing through the roof of the nursery, carried with it a quantity of débris through the floor of the nursery into the drawing-room below. Through the aperture thus made the fire from the nursery grate, and it is supposed also a lamp, were carried, and speedily ignited the contents of the drawing-room. The[16] fire, being fanned by the fierce gale, just then at its height, increased rapidly, and the premises were soon in a blaze.

Owing to the elevated position in which the house stood the conflagration was visible at a great distance, and in spite of the weather, large numbers of people visited the spot, although the journey thither, under the circumstances, was one of the most difficult it is possible to conceive. To those who ventured on the walk, however, the sight presented was an extraordinarily impressive one. The flames raged like the blast of a furnace, and the mingling of smoke, sparks and snow-dust produced an effect that was as novel as it was terrible. Sparks from the burning building were carried immense distances, and beaten, with the snow-powder, against the windows of houses that faced the burning villa. Standing at a distance of nearly a mile, with eyes fixed on the blaze, it was impossible to believe that the roar of the fire could not be heard, so nearly did the howling and surging of the wind resemble the roar caused by a great volume of rushing flame.

In connection with the fire several narrow escapes are recorded. Mr. Venning's daughter, about six years of age, had a perilous experience. She had been put to bed by her nurse, and, during the absence of the latter from the room for a few minutes, the chimney clashed through the roof into the drawing-room. Fortunately Mr. Venning's daughter received nothing worse than a severe fright, and she was quickly removed to a neighbouring house. The ladies who were in the drawing-room at the time of the crash were also greatly alarmed, and made a[17] hasty exit from the building, being hospitably sheltered at Wingfield House by Colonel Goodeve, R.A., and also at the house of a relative, in Godolphin Terrace.

The efforts of the firemen to prevent the spread of the flames, under circumstances of great difficulty, were crowned with a well-merited success. Water was not readily available, and when obtained was not abundant, but notwithstanding this a gallant fight was made, and although to save the one dwelling was impossible, the contents of the adjoining one were safely removed, and the structure itself was snatched from total demolition. In addition to the West of England and Devonport Fire Brigades, and a large staff of constables under the charge of Mr. Evans, the Chief Constable of Devonport, there were present Colonel Liardet, R.M.L.I., the field officer of the day, and a detachment of men belonging to the King's Own Scottish Borderers, under Captain Haggard. Several manual engines from the troops in garrison were taken to the scene of the fire, but, with one exception, they were not brought into use. A number of civilians were conspicuous for their energy in performing voluntary salvage duty. The damage resulting from this fire has been estimated at something like £7,000.

On their way to and from the scene of the fire by way of Millbridge, many pedestrians from Plymouth had narrow escapes from being blown over the parapet of the bridge into the Deadlake. About half-past eight, when the fire had somewhat abated, the majority of the Plymouth spectators moved back with the intention of re-crossing the bridge, but the wind had increased in[18] violence, and the water in the lake was so disturbed that the waves could be heard lashing against the bridge and on the shores. Some who ventured on the bridge were driven back, and consternation began to spread among the crowd, many women screaming loudly. To proceed to Plymouth by way of Pennycomequick was also a matter of difficulty, as the full fury of the gale blowing down the valley had to be faced. Many waited on the Devonport side until there was a lull, when some of them linked their arms in those of their friends for safety's sake and so crossed to Plymouth.

During the whole of Monday night Her Majesty's vessels in the Hamoaze were in positions of great peril, and those holding responsible posts in connection with them underwent great anxiety. The Lion and Implacable, anchored just above Torpoint, which form an establishment for training boys, under the command of Commander Morrison, dragged their moorings during the evening. The vessels were moored stern to stern, and connected by a covered gangway. The cause of the mishap was the parting of the starboard bridle of the Implacable. At about half-past nine signals of distress were made to the shore, and it was stated that the two ships had been driven ashore, and were in the mud off Thanckes. This, however, proved not to be the case, as the vessels never even touched the ground. As soon as the danger was known all available tugs at Devonport Dockyard were despatched with a view to taking off, if necessary, the hundreds of boys who were on board. At midnight, however, all apprehension for the safety of the vessels had been practically removed, although as[19] the storm had by no means abated, the tugs were ordered to stand by all night in order to give any assistance that might be required.

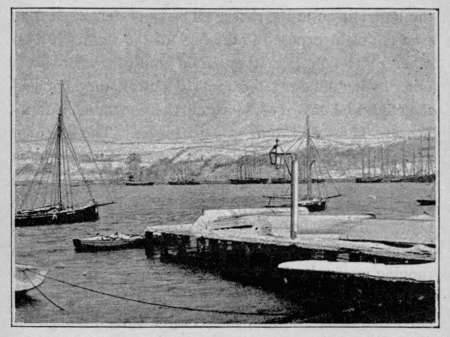

In the meantime there was great excitement in Sutton Harbour. Between eight and nine o'clock several of the trading vessels, trawlers, and fishing craft lying at anchor began to drag, and extra warps had to be got out, and the vessels secured. The sea in the harbour was very heavy, and at one time some fear was felt for the buildings along the quay, but no damage of this nature occurred. Some of the stores along the North quay were roughly handled by the wind, the roof of the new coal store of Messrs. Hill and Co. was blown off, and a similar accident occurred to the premises in the occupation of Messrs. Vodden and Johns, but generally speaking the damage on the quays was satisfactorily light. A good deal of anxiety was expressed as to the welfare of trawlers who were known to be in the channel, and, as a subsequent chapter will show, these fears were by no means groundless. The cutter of the harbourmaster, lying in Plymouth Sound was reported to be in a sinking condition during the night, and a tug was sent to her assistance. She had four men on board, who were removed for safety, but ultimately the cutter weathered the storm, and is still afloat.

Under conditions like these the night of the ninth of March wore away in the Three Towns. To many the night was a long one, and crowded with all sorts of apprehensions. The wind, never for a moment silent, rose again and again to hurricane force, and the fine snow so swiftly covered the window panes that to look[20] out upon the night soon became a matter of difficulty. There was no great feeling of security indoors, but to remain out for long was a matter of impossibility, and the imperfect and disconnected rumours of disaster that were disseminated created all the more alarm from the fact that they could not be investigated. Hundreds of households did not go to bed at all, while very many sat up all night because their bedrooms were in a state of hopeless confusion, or of absolute wreck. Some were without fire, through a defect having been brought about in the chimney, or through the chimney having fallen in altogether; and in those localities where the buildings were of the dilapidated or frail order the wretchedness for the night, and, indeed, for the week throughout, was very great.

Not the least serious part of the gale was the number of friends missing from the Plymouth district. Quite early there was a breakdown of the telegraph wires, which made all telegraphic communication with other parts of the country impossible, and the late arrival of many trains into the west, and the non-arrival of others, led to much anxious conjecture as to the fate of those whose appearance in Plymouth during the night had been confidently expected. The first indications of telegraphic interruption were observed as early as half-past four on Monday afternoon, when communication with Tavistock was suspended. Following this, the reports of breakdowns from all parts of the two counties became very frequent until about seven o'clock, when communication with London and all places above Plymouth ceased. Penzance, and one or two Cornish[21] towns could be communicated with for some time longer, but soon all operations were suspended, and no messages were received at the Plymouth office after eight o'clock. As a general rule the breakdown was caused by trees falling across the wires, or by the telegraph posts having been brought bodily to the ground. As will be subsequently seen, this condition of things prevailed to a great extent, and in some cases the telegraph wires and posts got upon the railway lines and prevented the progress of the trains.

The interruption of the local train service commenced early on Monday. Trains due at North Road Station, Plymouth, between mid-day and eight o'clock in the evening were all considerably behind time, and the telegraphic and telephonic instruments being rendered useless, thus making communication with other stations impossible, the officials had an anxious period of waiting for information of belated trains. At about nine o'clock the "Jubilee," which left London at one o'clock, and should have reached North Road, Plymouth, at 7·30, came into the station. With the remarkable experiences of passengers by this, one of the last trains that reached Plymouth by either the London and South Western or Great Western lines from Monday night to Saturday, and other trains that failed to reach Plymouth at all, a subsequent chapter will deal, should space permit. A train from Tavistock, due at 8·40, did not appear until eleven o'clock, and the eight o'clock train from Launceston did not come at all. The "Alexandra," a train that left Waterloo Station at 2·40 arrived at nine o'clock, the driver stating that near Okehampton he had to drive[22] through three feet of snow. These, however, are the trains that did arrive. There were many that did not, and in many scores of instances a member of a family was not heard of for days, although, happily, in the majority of cases, the missing one ultimately turned up with nothing worse than a severe cold and a great distaste for winter life in small Devonshire or Cornish towns.

So far the state of affairs in the Three Towns only has been dealt with, but it will be readily surmised that adjacent towns, and more especially those in the neighbourhood of Dartmoor, and the more open parts of Cornwall, suffered very considerably. Generally speaking, the damage to house property was nowhere so great as in Plymouth and Devonport. In the country districts, as a matter of course, calamities of a most serious and special character were met with, and trees were felled, sheep buried, and oxen frozen in enormous quantities,—in some instances, also, human life was sacrificed, but in none of the other larger towns was the devastation so widespread as in the Three Towns. At Exeter, the fall of snow was said to be the heaviest for years, and by reason of its suddenness, even more severe than the storm of 1881. The drifts of snow in some places were of great depth. As at Plymouth, traffic as well as business was suspended, but there were no serious mishaps, the force of the wind, though great, being evidently not so fierce as was the case further west. Railway communication between Exeter and Plymouth was of course impossible, but there were on Tuesday four trains trying to run between Exeter and Taunton. The North of[23] England mail, which should have arrived at Exeter at half-past eight was four hours late, but it did put in an appearance. The trains of the London and South Western Railway ran to Exeter from the North just as usual, throughout the week.

At Torquay the storm was the severest experienced there for many years. There was a heavy fall of snow on the night of Monday, and on the following morning the ground was covered to the depth of a foot. A strong easterly wind was also blowing, and trees were uprooted in every part of the district. At the Recreation Grounds the roof was blown off the grand stand, and a huge tree blew across the railway at Lowes Bridge, near Torre Station. An engine of the up-train cut through this and traffic was suspended until the line was cleared by a breakdown gang on Tuesday. The trains from London and Plymouth failing to run, Torquay soon became isolated, and telegraph and telephone communication was early interfered with in consequence of the poles being blown down and the wires broken by the burden of snow. Considerable damage was done to the New Pier works by the heavy gale. Plant for moulding the concrete was washed away, as was also a portion of the masonry, while parts of the sea-wall were damaged, and a flight of stone steps leading to the sea-wall were swept completely away. Street traffic was so much impeded by the snow that on the Tuesday after the storm the Town Surveyor constructed a wooden snow-plough, and with this, drawn by two horses, the roads were cleared. All the public clocks in the town were stopped by the snow.

Tavistock was one of the towns that had the severest experiences. The barometer fell rapidly on Monday morning, and at about eleven o'clock snow began to fall; while, as the day advanced, it was accompanied by a high wind, that, towards seven o'clock in the evening, increased to a hurricane. In Tavistock, and all along the Tavy Valley, the full force of the storm was felt, large trees being uprooted, houses unroofed, and chimney-stacks blown down in every direction. One of the latter instances occurred in West Street, where the occupant, a lady, had been suffering from a serious illness. The chimney-stack being blown over, the débris fell through the roof into the bedroom where the invalid was lying. Her attendant received some cuts on the head, but the invalid escaped the falling masonry, although she received a severe shock to the system through the incident. A waggoner employed at the Phœnix Mills, Horrabridge, was returning to Tavistock from Lifton on Monday night, in charge of an empty waggon and three horses, and when within two miles of his destination, found that through the violence of the storm he was unable to continue his journey. He took the horses out of the waggon, and made an ineffectual attempt to drive them home. Failing in this the waggoner walked into Tavistock, and at about ten o'clock returned to the spot where he had left his horses. By this time the snow was so deep that the horses could not be seen, and it was necessary to leave them until the following morning. Eventually they were dug out, and driven home, not much the worse, to all appearance, for their night in the snow. Tavistock being an important market town, and[25] the centre of a large district, experienced great inconvenience through the interruption in railway traffic, and the impassable state of the roads. Wednesday, March 11th, was the monthly cattle fair day, but not a single animal was brought in. At the Fitzford Church the window was blown in. Like many other towns in the Dartmoor vicinity, Tavistock received more than one disastrous visitation during this memorable week, and its record of lost sheep and cattle, to which more extended reference will be made further on, is a very serious one.

At Bideford, and in the surrounding country, the weather was more severe than any experienced since the winter of 1881. The barometer had been steadily going back all day on Sunday, and on Monday a cutting east wind blew with considerable force. Snow commenced falling at noon, and continued until the evening, when the streets and roads were covered to some depth. Then the wind rose to half a gale, whirling the snow into little clouds, which filled both doors and windows. All through the night the wind increased in force, until it blew a perfect hurricane. Icicles hung inches long from windowsills and launders of the houses. In the country, traffic was completely suspended, the snowdrifts being as high as the hedges. Farmers were consequently unable to get into market, and provisions went up considerably in price. The mail coach started for Clovelly and Hartland as usual on Tuesday morning, and managed to reach Clovelly. There, however, the horses had to be taken out, and the driver rode through the deep drifts to Hartland on horseback. The return journey was performed[26] by another man in a similar way. All the mails were delayed, and rural postmen's districts were mostly impassable.

At Teignmouth, Exmouth, Dawlish, and most other seaside places from the estuary of the Exe to the Start, the effects of the gale were severely felt on Monday night. At the former place the sea ran high, and the breakers fell with great force close to the landwash and over the promenade. Opposite Den House the roadway was undermined and washed away, and had it not been for the fact that an hitherto existing stone wall lay buried beneath the surface, which acted as a breakwater against the heavy sea, it is almost certain that Den House and Bella Vista would have been washed away. As soon as the tide ebbed, the wind veered towards the northward, and the sea went down. A gang of men were at once set to work to shore up the embankment, and fill in the cavity made by the sea. The Promenade towards the East Cliff was also washed up in several places. In the Exeter Road and at Brimley a large number of trees were blown down, and traffic was generally suspended.

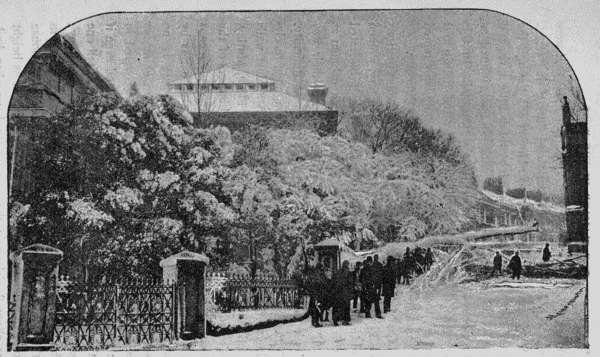

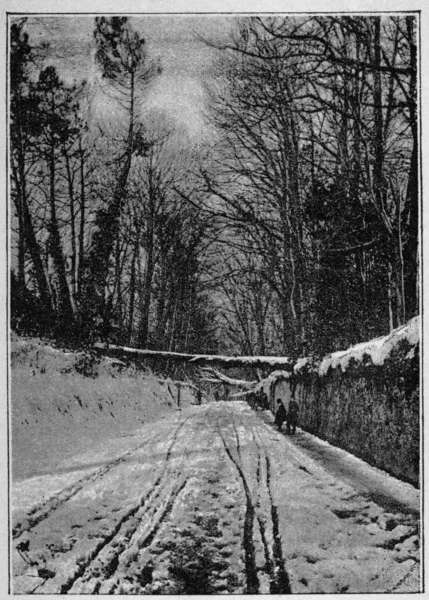

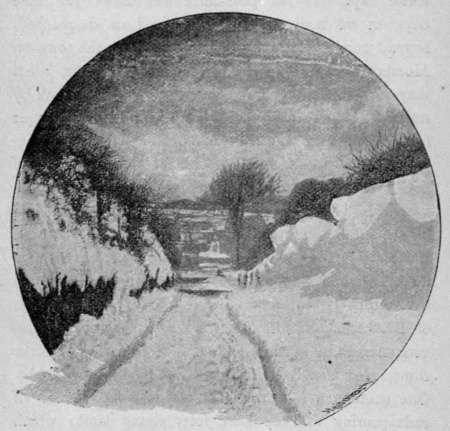

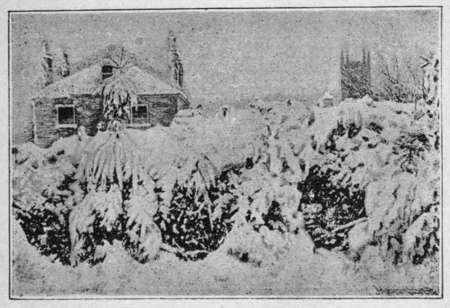

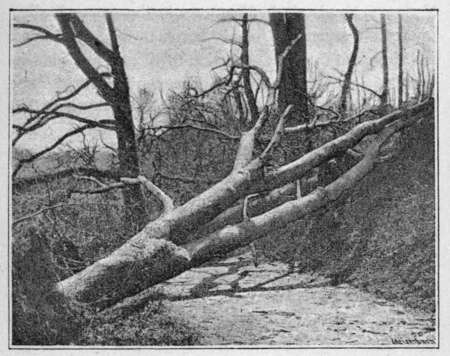

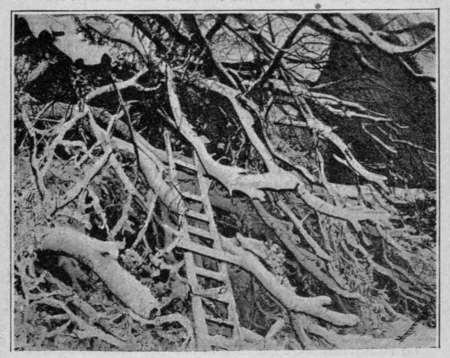

An illustration from a photograph by Messrs. G. Denney & Co., photographers, of Exeter and Teignmouth, portrays one of the scenes in Exeter Road, which was impassable for a day or two.

At Totnes, Brent, and in fact every town in Devonshire, damage of a more or less severe character was sustained. Space will not allow of a separate reference to each locality in the present chapter, but in dealing with occurrences that took place after the early force of the blizzard had been exhausted on that memorable[27] Monday night and Tuesday morning, there will be found few districts that necessity will not compel us to bring under notice.

Reference has already been made to some towns in the North of Devon. Throughout the whole of this district the storm raged furiously, rendering communication with many parts impossible. Although snow did not commence to fall until Monday afternoon, by the evening of that day the drifts had reached a depth of several feet. The train which left Barnstaple for Ilfracombe at about half-past eight on Monday evening became embedded just below Morthoe station. At Ilfracombe a strong gale raged throughout Monday night, and the brigantine Ethel, of Salcombe, 180 tons went ashore at Combemartin, but in this instance no lives were lost, the crew having taken to their boats. In North Cornwall, a terrible snowstorm raged for twenty-four hours, resembling in many respects the great storm of the 18th and 19th January, 1881. The atmospheric pressure was about the same as then, and the storm burst from the same point. On the first day of the great storm in 1881, the temperature varied from 26 to 30 and on the second from 25 to 30. On the 9th of March in the present year it varied from 29 to 31½. The roads were soon blocked in all directions, trains on the lines ceased running, and no mails could be sent or received. Bude was cut off from the outside world, except by telegraphic communication. In the roads around Bude the snow was quickly as high as the hedges, so that traffic, even on foot, was rendered impracticable. Falmouth, Liskeard, Camborne, and indeed all other Cornish towns, had a rough night,[29] and before our story is finished, like many towns in Devonshire, they will be found to have suffered severely. To approach them with any hope of successfully relating how they all fared on the night of Monday and on the Tuesday following, we must deal with the railways, for from railway travellers who were detained in certain places on the course of their journeys, and from the energetic officials who after heavy and anxious toil succeeded in releasing them, many of the most thrilling narratives have been obtained.

Some incidents in connection with the suspension of the railway service on every line connecting Plymouth with the rest of the world have already been related. It is unnecessary to dwell at further length on the terrible mental and physical suffering entailed by this state of things. Facts need no comment that tell of passengers being snowed up in a train for thirty-six hours on a stretch, and others being unable to communicate with their friends for nearly a week, to say nothing of all that the engine-drivers and other officials had to endure.

One of the first expeditions that set out into the dreary night in search of the cause of delay was undertaken by Mr. C. E. Compton, the divisional superintendent of the Great Western Railway Co., and other gentlemen, who went out on a pilot engine as far as Camel's Head Bridge between eight and nine o'clock on Monday night. The cause of the interruption in the telegraph system was here ascertained, the poles being blown down and lying across the line. Later in the evening Mr. Compton pushed on as far as Hemerdon, on the main line, where a similar state of things was encountered, and it was learned that at Kingsbridge Road and at Brent Station the snow had drifted to such an[31] extent as to block the line. A train due from Penzance was known to be somewhere on the Plymouth side of Truro, but its exact whereabouts could not be discovered. There was some anxious looking out for the "Zulu" express from Paddington, due at Plymouth early in the evening, but the train was at Brent, with about ten feet of snow on the line, between it and Plymouth, and, as will be presently seen, the passengers were meeting with some novel and undesirable experiences.

The mail train from Plymouth for London left Millbay Station at the usual time, 8·20, and Hemerdon Junction was reached with much difficulty. Here the first deep cutting had to be encountered, and the driver, approaching it at a reduced speed, observed that the drifting snow had practically blocked the entrance. The seriousness of the situation was realized by one and all of the passengers, and, although there was an anxiety on their part to get to their destination as soon as possible, they agreed that there was no alternative but to either remain where they were or return to Plymouth. The latter course was decided upon, and shunting was at once proceeded with. The drifts of snow rendered this work very difficult, and the frequent jerkings caused the passengers much inconvenience. Eventually the driver, after most skilful handling of the locomotive, succeeded in reversing the position of the engine, and a start was made for Plymouth. Much to the relief of the passengers, the latter place was reached, after a slow but sure journey, about half-past one next morning. The utmost consideration was shown the passengers by the station officials, and accommodation[32] was found them for the night at the "Duke of Cornwall" Hotel and in the station waiting-room.

All traffic on the London and South Western Railway below Okehampton ceased soon after eight o'clock on Monday night. One of the slow passenger trains from Okehampton was snowed up in a deep cutting between Meldon Viaduct and Bridestowe, one of the bleakest spots on the South Western system. The express due at North Road Station at 11·4 on the same night was stopped at Okehampton. The ordinary seven o'clock up-train was despatched on Tuesday morning from Mutley Station, and was drawn by three engines. Considerable danger attended railway travelling in consequence of the jolting and straining that occurred when the numerous obstructions were met with. All the points at the Tavistock Station were completely choked, and though for some hours a number of men were employed in an effort to keep them clear, the task was found impossible, and as a result the train that might have proceeded in the direction of Plymouth remained where it was as the engine could not be shunted to the Plymouth end of the train. The last up South Western train on Monday night was snowed up at Lidford, but the passengers were released. One of the vans of a goods train proceeding to Tavistock early on Monday evening was blown away.

Serious as was the condition of things on all the railways on Monday night, on Tuesday matters became worse. During that day only two trains reached Millbay Station, Plymouth, and these, which came from Cornwall, should have arrived on Monday night. One[33] account, of experiences as unique as they were unpleasant, is thus given by the Western Daily Mercury:—"The mail train from Cornwall, due at Plymouth at 8·10 on Monday night, reached Millbay at 9·30 A.M., bringing some eighty passengers; amongst whom were Mr. Bolitho, banker, of Penzance, and Mrs. Bolitho, who were wishful of getting to Ivybridge to attend the hunt, and Mr. J. H. Hamblyn, of Buckfastleigh, who was en route from Liskeard to Bristol Fair. All went well with the mail until St. Germans was reached at about 8 P.M. It was found that no further progress was possible, and that there was no help for it but to pass the night in the carriages under the shelter of the station. Mr. Gibbons, one of the assistant-engineers of the line, and Inspector Scantlebury, who were travelling in the train, resolved to walk to Saltash. The snow was not so very deep at this time, and the block was due principally to the wholesale destruction of telegraph poles. After a rough time of it the two officials reached Saltash, and afterwards pushed on to Camel's Head, where was the biggest block of all, fir trees and telegraph poles and wires being scattered about broadcast. Meanwhile at St. Germans the station-master (Mr. Priest) was doing his best to make the passengers as comfortable as possible. In fact, all of those who reached Plymouth after the night's adventure are loud in their praises of Mr. Priest. Messengers were despatched by him to the village, and loaves, butter, tea, and coffee were speedily bought up. At the station fires were lit in all the available grates, and very soon the passengers were in possession of hot tea and coffee, as well as bread and butter. This modest fare was repeated[34] at intervals during the night, and it goes without saying was most welcome.

"After spending something like ten hours at St. Germans the mail was able to leave at eight o'clock on Tuesday morning for Saltash, but here another delay of nearly two hours took place, in consequence of the block on the Devonport side of the Camel's Head bridge. To remove this a breakdown train had been sent out from Plymouth at 6 A.M. in charge of Mr. H. Quigley, the assistant divisional-superintendent. This train got as far as Keyham Viaduct without much interruption. Here an array of prostrate poles and fir-trees required removing, and then the breakdown train forged ahead slowly to the Weston Mills Viaduct, where there was a confused mass of poles and wires stretching from one side of the creek to the other. This accomplished, a move was made to Saltash, where the mail was met and safely escorted to Plymouth, which all were glad to reach, after a novel but most unpleasant night's adventure."

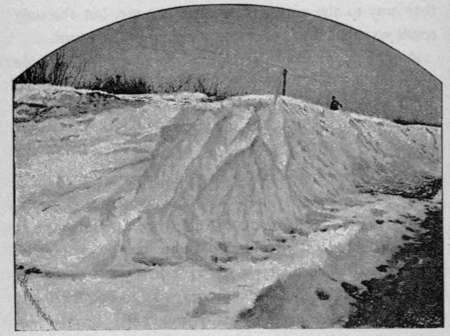

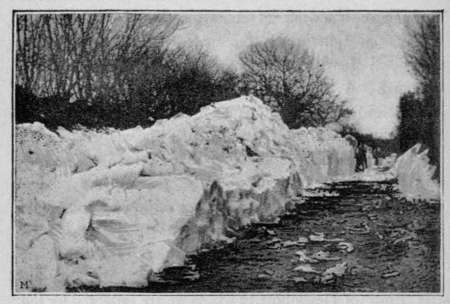

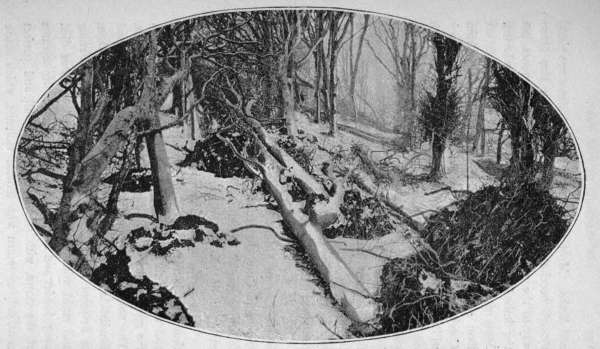

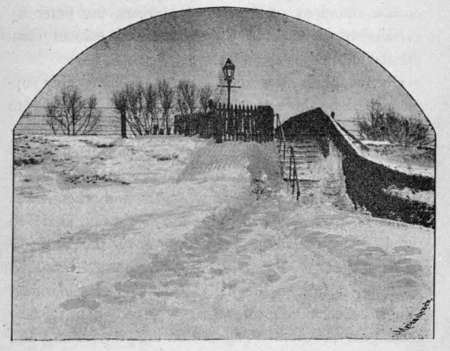

The difficulty that beset those that attempted to travel by road the above view indicates, and is from a photograph by A. Leamon, Esq., of Liskeard.

One of the passengers in the train snowed up between Princetown and Plymouth in the evening mail has related the following experiences:—"We left Princetown at 6·30 P.M. on Monday—the regular time—with five bags of mails. The snow beat in our compartment through closed doors, ventilators, and windows so much, that in a few minutes I had two inches of snow on my umbrella. We stuffed paper, handkerchiefs, and cloth into every hole or crevice we could find, and this remedied matters a little. The coach we were in was a composite one—of four third-class compartments, one second class, one first class, and one guard's, and we were all in one compartment. Well, the wind was blowing great guns, and we passed through two large drifts just after leaving Princetown, but it required some heavy pulling. We had just been congratulating ourselves on having been lucky in getting so nicely through the storm, when we suddenly stopped, and we knew we had stuck in the snow. The engine driver came and said, 'I was afraid of it; we have got over a bar, and we cannot go on. We ought not to have started.' The ladies became alarmed, and with that the driver, fireman, and guard went to the front of the train with shovels to try and dig a way for her, but it was no good. It is true that the place where we stopped is on a bit of decline, but the engine was choked with snow. The guard, having told us that we could not get on without assistance, proceeded in the direction of Dousland to get help. He had been gone about an hour, when he returned with the mournful intelligence that he had lost his way, and that it was no use for him to attempt to reach Dousland, as the snow blinded him. We decided to make ourselves as comfortable as we possibly could under the painful conditions to which we were subjected—six men and two ladies huddled together in one compartment—the cold being most bitter, and none of us having anything to eat or drink. We lived the night through, but in what way I can hardly tell.

"In the morning the wind was blowing as strong as ever, and the snow as it fell melted on the window panes,[37] and the lamp—our only light—was extinguished at 7 A.M. Just at this time the guard and fireman left us, saying they were going to try and reach Dousland with the 'staff,' so as to let them know of the disaster, and see what help could be rendered. It is true that the fireman was lame, but I understand they had fearful trouble, as he was sadly knocked up and his foot badly lacerated. Some little time afterwards the driver, who has, I believe, been seriously ill, announced his intention of going to Dousland. We then felt in a particularly sad condition, feeling our only hope was gone now that the driver had abandoned us. The storm was raging as fiercely as on the previous night, but at 3 P.M. we were agreeably surprised to find three packers, who had tramped up from Dousland with refreshments for us, knock at our door. We were heartily glad to receive the refreshments, which, I believe, were sent from the railway company to us in our forlorn position—although it only consisted of cocoa, bread and butter, and cake, with a bottle of well-watered brandy to follow. We found there was enough for us to have one piece of bread and butter and one piece of cake each. This was not a very substantial bill of fare for people who had had nothing to eat for over twenty hours, but we were thankful for small mercies. There is one thing I forgot: the packers were very kind, and brought us out the guard's lamp from his van, which we afterwards lit. One of the party, I think Palk, asked if the packer thought we could weather the journey back. The packer replied, 'It will take you about two hours.' This was enough for Palk, who said he thought he was better where he was. Besides, we asked him to stay and not desert us in the time of trouble.

"We then awaited the result of events. The wind was fearful, and we were all bitterly cold. We were nearly dead in the afternoon, and drank all the brandy by eight o'clock. If it had not been for that some of us would have given way. The weather was milder after midnight. About seven o'clock this morning one of us looking out of the window saw Mr. Hilson, of Horsford, farmer, whose farm is only about 250 yards from where our train was lying, picking sheep out of the snow. We whistled to him, and on his coming to us he was told of our predicament. He expressed his astonishment that he knew nothing of the accident. We do not see how he could have, because the snow had been so blinding in character until that day that it was impossible to see anyone ahead. He offered us the use of his farm, and we joyfully accepted the same, leaving the train after being in her for 36 hours. Poor Mrs. Watts was much distressed and we had to assist her down. We had breakfast at Mr. Hilson's, and then four of us—Hancock, Viggers, Palk and Worth—started to walk to Dousland, which we could see ahead of us. We got on fairly well over the snow, which was very deep in some places. We could not keep our eyes open owing to the snow when we left Princetown, and when we asked the station-master for tickets he said, 'You can have them, but I cannot promise you will get there.' It did not strike me at the time, but if a station-master had any doubts as to the safety or otherwise of a train he should not allow the train to travel. It is true the wind was in our favour when we started. Mrs. Watts is very bad indeed, and also the engine-driver and stoker. The engine of the[39] train when we left was completely covered with snow, and the snow had drifted as high as the carriage, with a blank space between the body and the wheels. All the compartments into which I looked before I left her—although the windows and ventilators were closed and doors locked—were full of snow above the hat-racks. It was the most horrible experience of my life."

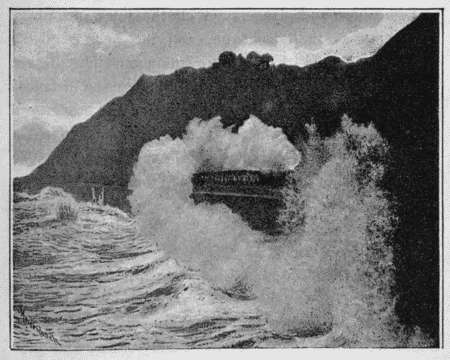

Great anxiety was felt in Exeter and Plymouth on account of the sea wall which carries the line of the Great Western Railway Company from Dawlish to Teignmouth. In past years this piece of line has suffered very severely, and rumours were in circulation that it had been washed away in some places. Happily, however,[40] it was found, as soon as communication became opened up once more, that the line remained intact, the damaged portion of the sea wall being a carriage-drive close to the town. One of our views, from a photograph by Messrs. Denney & Co., photographers, of Exeter and Teignmouth, gives an admirable idea of the force of the sea in this district, during the progress of a gale from the south-east.

Difficulties and dangers on all the lines of railway multiplied as time went on, and the horrors of the Monday night, of which the foregoing narratives present only a partial view, were succeeded by some sad instances of loss of life, besides great damage to the property of the respective companies, and as a matter of course, a heavy falling off in their traffic returns. The returns for the week, following March 9th, on the Great Western system, showed a decrease of £12,980 as compared with the corresponding week of the previous year, and the South-Western Railway's decrease amounted to £3,662—all but £650 of which was lost from the non-conveyance of passengers and parcels. This was regarded as especially unfortunate in the case of the South-Western Railway, as its traffic returns had previously been going up week by week, and in the eleven weeks of the year had increased by £12,120, as compared with the first eleven weeks of 1890. In addition to these losses heavy expenses were incurred by all the companies by the efforts made to clear away the snow, by means of snow ploughs, and the employment of large gangs of men. The inadequacy of the snow ploughs, which dated in England from the time of the heavy[41] snow-fall in the early part of 1881, for clearing away heavy drifts, has been generally admitted. The ploughs are quite competent to get rid of from 4 to 5 feet of snow, but their capacity is not equal to depths ranging as high as 18 feet, such as were dealt with in some places between Newton Abbott and Plymouth, on the Great Western system, to say nothing of other sections and branches. The ploughs, which are kept at Swindon, have an iron ram in front, projecting like that of an ironclad, with a "cutter." The attention of engineers has, however, been now directed to a new kind of machine, with a revolving, spade-like apparatus, having a powerful shaft, and a propeller that is designed to scatter the snow with which it is brought into contact, and throw it clear of the rails on which the engine is travelling. The work of cutting out engines that had been absolutely embedded was very arduous, and in one case, lamentable loss of life accompanied the other misfortunes brought about by the storm.

One or two instances of striking and unprecedented experiences of the night of Monday must be recorded before this part of the subject, which is, in itself, enough to fill a volume, is dismissed.

Passengers by the train which left Queen Street Station, Exeter, on Monday evening at 6·38, and was in connection with the 2·20 from Waterloo, had an exceptionally rough time. The train, a slow one, had to make its way across Dartmoor from Okehampton to Tavistock, and on starting, the guard, Mr. Moore, had orders to proceed as far as he could. After cutting through the snow for some miles the train reached Okehampton, and then[42] attempted to brave the force of the storm that was sweeping down from the Dartmoor hills. It got over the Meldon Viaduct safely, and then it was attempted to go on over Sourton Down, but in going through Youlditch cutting it ran into a snow-drift, and about three miles to the west of Okehampton it was brought to a stop. Efforts were made to run back to Okehampton, but the rapid drifts of snow, which were from ten to twenty feet in height, prevented this being done, and it was soon seen that there was nothing left but to remain until help of some kind could be obtained. There were only eleven passengers, including two ladies and two children. The ladies and children, who were well supplied with wraps, were bestowed as comfortably as circumstances would permit in a first-class carriage, the male portion of the party, with the guard, Mr. Moore, the driver, Mr. Bennett, and the fireman, Mr. Oates, trying to find some warmth in the guard's van. This, however, was a matter of impossibility, the bitter wind and the fine snow finding its way into the compartment, to the great discomfort of the occupants. The engine fire was kept alight, but was useless to impart warmth to the unfortunate party. It was only on the following day, and just before relief arrived, that Mr. Bennett had succeeded in getting a fire in the van by means of boring holes in one of the engine-buckets, filling the bucket with coal and, after much difficulty, kindling a flame, which the draught obtained through the holes soon increased into a most welcome blaze. Mr. John Powlesland, auctioneer, of Bow, was one of the belated travellers, and was especially assiduous in his efforts to do all he could for his fellow-sufferers.

When the train first showed signs of becoming embedded, a telegram was sent from the nearest signal-box to Exeter for assistance, and two engines were sent down. These approached within three-quarters of a mile of the snowed-up train, but could not be taken nearer on that line. They were then, with some difficulty, shunted on the up-line, with the view of pushing their way to the carriages in that manner, but the only result was that they became snowed-up in their turn.

As day approached Mr. Moore and Mr. Oates made their way to the Sourton Inn, which stood at no great distance, for the purpose of obtaining food, but their endeavour met with but slight success, the inn being also snowed-up, and the occupants having but little in the way of provisions that they could spare. No help arrived until Tuesday, at mid-day, when a search-party, headed by Mr. Prickman, the Mayor of Okehampton, and consisting of some half-a-dozen gentlemen of that locality, succeeded, after a difficult journey, in reaching the train. They took with them food and liquid refreshment, and were most heartily welcomed by the imprisoned travellers. By this time the train was entirely buried on one side, the engine having forced the snow on the left side up to a height of fully twenty feet. Only a small portion of the engine and carriages was visible, and the scene is described as a remarkable one.

The travellers were at once conducted by their rescuers to Youlditch Farm, where Mr. Gard treated them with much kindness, and took care of the ladies and children. The gentlemen subsequently made their way on to Okehampton, where they were detained for[44] several days. The guard, engine-driver, and fireman were not able to leave the train until the following day, when a breakdown gang was employed to cut a passage for the train through the snow—a task that occupied nearly the whole of the week.

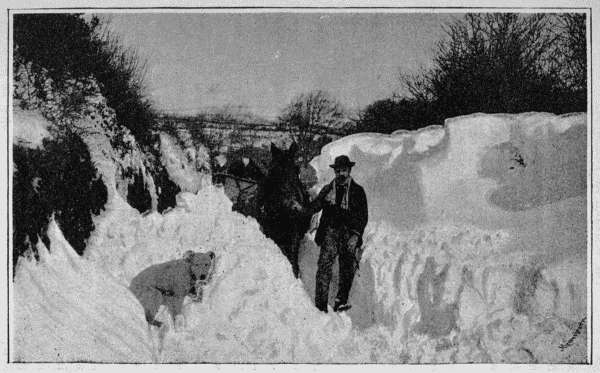

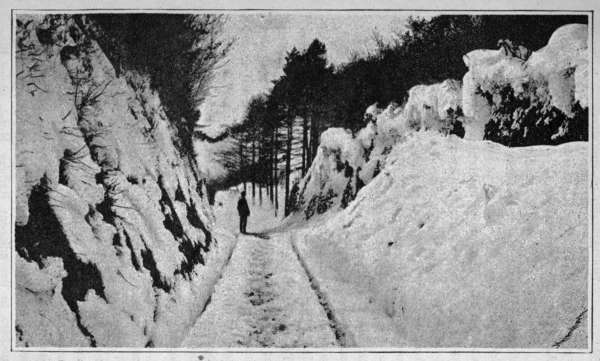

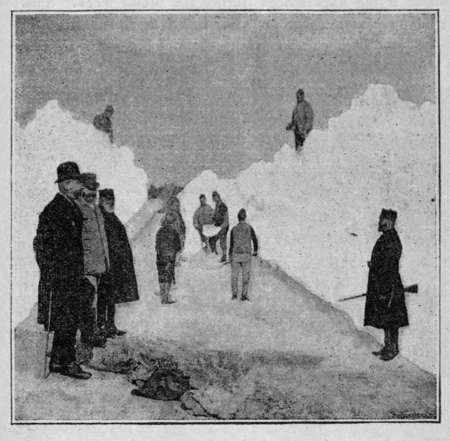

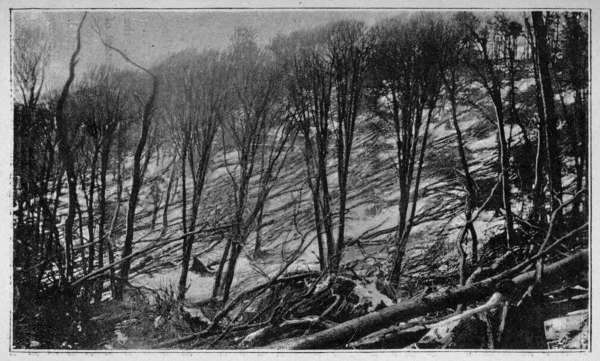

On the Launceston branch of the Great Western Railway, the down-train, which left Tavistock at seven o'clock on Monday evening, remained embedded in the snow outside Horrabridge for several days. Between the Walkham Viaduct and Grenofen tunnel very heavy work had to be done, a deep cutting being not only choked by the snow, but quite a score of trees having been blown across the rails. The accompanying illustration, depicting a snow-drift in this locality, from a[45] photograph by Mr. Sheath, of George-street, Plymouth, conveys an excellent picture of the heavy masses of snow that had accumulated on this part of Dartmoor.

A passenger by the train which left Penzance at 6·25 P.M. on Monday and arrived at Plymouth at 3 P.M. on Tuesday, has supplied an interesting account of the blockage near Grampound Road. The train, containing about a dozen passengers, was only a quarter of a mile above Grampound Road Station when it encountered a drift of snow fully twenty feet high. It was impossible to proceed or to retreat, for the blinding storm had drifted more snow on to the line behind, so that passengers left the train and crossed some fields back to the village, and found shelter at the Grampound Road Hotel. It was then about 10·30 P.M. The guard Kelly remained on the train, and the under-guard Hammett walked back to Grampound Road and wired to Liskeard for a relief engine. He then walked on to meet an engine which had been sent for from Truro, and returned to the train on it. A relief gang arrived from Lostwithiel under engine-driver Harris, and the men dug at the drift until eleven A.M. on Tuesday, when the train was able to proceed. One of the workers described the cold as so intense that the snow froze on the men's clothes, practically encasing them in ice, and the under-guard Hammett, who had been at the work for over twenty years, said he never had such an experience, and even in the terrific storm of 1881 the snow was not so blinding.

Another passenger who travelled by the 6·50 Great Western up-train from Plymouth on Monday returned by a somewhat roundabout route, and he thus described his[46] experiences: Hemerdon was reached without any delay on the journey, but at that point the train was drawn up for about three-quarters of an hour, to allow a down train to pass. It then proceeded slowly in face of a terrific gale, accompanied by blinding snow. After leaving Cornwood, a grating sound on the roof of the carriage suggested broken wires, and this was followed by a jerk and a stoppage, and the interesting announcement that one coach and the engine were off the rails, and embedded in a snowdrift. There was nothing for it but to wait, and the "wait" lasted the whole night. There was nothing to eat for anybody, and the forty or more passengers (amongst whom were several ladies) had to make their night watches as comfortably as was possible under the circumstances in the Langham cutting! It seems that the driver and one of the guards succeeded in reaching Ivybridge, about a mile away, in the late evening, but no notice of the proximity of the village was given to the passengers. On Tuesday morning a small party from Ivybridge, under Messrs. Brown and Greenhough, two engineers superintending the alterations to the line in the neighbourhood, came to the rescue of all who were willing to face the blinding storm. Only four consented to go, and they were very thankful to exchange the cold comfort of the railway carriage for the hearty hospitality offered by these gentlemen in Ivybridge.

The officials here do not seem generally to have been equal to the exigencies of the situation, no notice of their whereabouts being given to the passengers, nor any organised attempt made at rescue or provisioning, but a porter and a packer from Ivybridge station arrived about daybreak with whisky and brandy. When the four[47] passengers referred to were leaving at about 9·30 on the Tuesday morning, bread and butter and tea were being dispensed. Many of the remaining passengers were hospitably accommodated by Miss Glanville at her house close to the half-buried train, the ladies being assisted thither by the engineers and their party. Another train was detained at Ivybridge Station, and the passengers from it were lodged in the village.

In West Cornwall three trains were snowed up. The train which left Plymouth at five o'clock on Monday night and should have reached Penzance at 8·45, arrived there at eleven. The "Dutchman" which should have, in the ordinary course of things, followed within fifteen minutes of this train, did not arrive at all, and news soon reached Penzance that the fast train was snowed up, but in what spot was only ascertained with much difficulty. A train was at once got ready, and on it Mr. Blair, the station-master, Mr. Ivey, the superintendent of the locomotive department, Mr. Glover, and a breakdown gang, proceeded to Camborne, which was reached about noon on Tuesday, it having taken about nine hours to accomplish a journey of thirteen miles. All the way along huge drifts of snow were met with, completely blocking the passage, and at frequent intervals the way had to be literally cut through the drifts by the men of the breakdown gang. Thus, with great difficulty, Hayle was reached, and from thence to Camborne the task became almost overpowering. Here the open country favoured the accumulation of snow, and the drifts were immense. In a deep cutting, close to Gwinear Station, was encountered a drift of about eighty yards long and nine feet deep.

On at length reaching Camborne it was discovered that the missing 8·45 train had left Redruth at about ten o'clock on Monday night—an hour and a half late. The storm was then at its height, and the snow was driving with such force that only very slight progress could be made. The train passed Carn Brea safely, but when within sight of Camborne Station, close to Stray Park, the engine left the metals, running on the south side, and finally bringing up at a hedge against which it lay on its side. Fortunately, at the time of the occurrence, speed was slow, and nothing more serious than some damage to the rolling stock, and the inconvenient detention of the twenty or thirty passengers occurred. These included five ladies, who were taken to the house of Mr. Maurice Reed, the Station Master at Camborne, the gentlemen of the party having good opportunities of finding comfortable quarters in the hotels of the town. Another train was embedded in fifteen feet of snow on the Helston branch line from Gwinear Road to Helston, and the guard, engine-driver, and stoker, with their one passenger, were compelled to abandon the train and seek shelter in a neighbouring farm-house.

While great inconvenience and discomfort was caused by the blizzard on the Cornish railways as a whole, no fatalities were reported, and the work of clearing the lines, great and arduous as it was, was accomplished in less time than in the districts above Plymouth, and in the vicinity of Dartmoor. Communication between Plymouth and Cornwall was opened up some days earlier than that with Totnes, Exeter, and other towns. The scene here depicted shows the depth of[49] snow in this neighbourhood, and is from a photograph by A. Leamon, Esq., of Liskeard.

Above Exeter things were not so bad. In the Tiverton district the effects of the blizzard were rather severely felt, and communication between some towns was for the time cut off. The railway authorities were very active, and gangs of men were sent up from Exeter on Tuesday to clear the lines, but they could do little more than keep the points clear for shunting, watch the signals, and fix detonators where required, the driving snow being so blinding, and the coldness of the bitter wind so intense. The difficulties of the neighbourhood commenced on Monday evening at the Whitehall tunnel, when the pilot, in front of the express, got off the line. Daylight came before a gang of packers sent from Taunton could effect a clearance, and instead of passing at ten o'clock on Monday night, the express only struggled into Tiverton Junction, with two engines attached, at half-past six on Tuesday morning. The night mail, and the North mail followed some hours after, and managed to get through to Exeter, but after that, until Wednesday morning at eleven o'clock, no train could leave the junction.

After being snowed up for some hours at Burlescombe, the first part of the newspaper train reached Tiverton at half-past ten on Tuesday night. The train was stopped at the home signal, and so intense was the cold that the machinery was, in a few minutes, frozen, and the train could not enter the station. The ladies—mostly for Plymouth—who were in the train, were carried on chairs by porters and packers to the adjacent Railway Hotel, where they, and some of the male passengers, were able to obtain[51] beds for the night. The train remained in the same position until Wednesday morning. In a siding also stood a slow train, which should have reached Tiverton on Tuesday at ten in the morning, but which did not get in until the afternoon. The passengers by this train were transferred to the first down-train that was got out from Tiverton on Wednesday. The second part of the newspaper train remained at Burlescombe all Monday night. The store of provisions in the hamlet was already exhausted, and although as much as a guinea was offered for a bed by some of the passengers, neither food nor sleeping accommodation could be obtained. A very uncomfortable night was passed in consequence, and many of the ladies suffered severely from hunger and exposure.

H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh, on his way to Devonport, was snow-bound at Taunton on Tuesday night, but with about two hundred other passengers, was able to proceed on his journey at the end of the week.

His Royal Highness afterwards conveyed to the Directors of the Company his appreciation of the courtesy and attention he received from the officials and servants of the Great Western Railway, on his journey during the gale and snowstorm, and during his detention at Taunton, on March 11th and 12th, and particularly thanked the Taunton station-master for his services.

At Brent, one of the most exposed railway towns on Dartmoor, the Zulu, from London, which was due at Plymouth at 8·55 on Monday night, came to grief, and a number of passengers spent several days of that week in this very bleak locality. Especial discomfort appears to have prevailed here, probably on account of the difficulty of obtaining assistance or information from any neighbouring[52] town, and from the limited resources for personal comfort that the town afforded. There can be no doubt that the experiences of the first two days and nights must have been wretched in the extreme. After two hours waiting in the carriages, in a state of considerable doubt as to what was to happen, the travellers found themselves at length at the Brent station. Here there was neither refreshment nor accommodation, but the hotels of the town were made for. Quarters were difficult to obtain, however, as a large number of contractors men working on the new line of railway were residing in the place. On Monday night many passengers lay upon the floor, using their overcoats for pillows, and their rugs for coverings. A Mr. Stumbles, a commercial traveller, who was one of the Brent unfortunates, gave an account of his experiences to a representative of the Western Morning News, which has led to much subsequent controversy, and to a shower of letters, conveying many diverse opinions, being sent in to the editor of that paper. It appears that there were about forty passengers in the train, and that many of these remained at the station all night, either in the train or in the waiting-room. Next day Brent was visited, and refreshments were bought at, as Mr. Stumbles says, famine prices.

The account referred to goes on to say:—"One gentleman bought a bottle of brandy, for which he had to pay 6s., the inns charged us double price for ordinary meals, and some establishments refused to supply us at all, probably thinking that a famine was impending. We returned to the station as best we could, through the great drifts of snow, and, with such provisions as we could buy, did the best we could, cooking such things as[53] bloaters in the station waiting-room. Our scanty supply, I must say, was most generously supplemented from the small stores which the railway officials, such as signalmen and others, had with them. There were a number of sailors and soldiers amongst the passengers, and most of them were without means. One gentleman gave them a sovereign, and ladies from Brent also brought them money, tobacco, and provisions during our stay. On the following monotonous days we spent our time in smoking and in conversation, and also in 'chaffing' the station-master, whom we christened 'Dr. Parr.' On Wednesday an enterprising amateur photographer from Brent took several views of our snowed-up train, with the eighteen or twenty passengers who stuck by it perched in various prominent positions upon it. We all united in praising the minor officials, and the men in charge of the train, for remaining faithful to us, and excused the want of sympathy of 'Dr. Parr' on account of his age. The driver kept the fires of his engine going all the time, but his boilers had to be filled with water by hand, and in this work valuable assistance was readily given by the soldiers and marines in the train. Just before we were enabled to leave Brent, we were visited for the first time by the clergyman of the parish, and our final leave-taking was celebrated by three sarcastic cheers for 'Dr. Parr' and for 'Brent.' The passengers in this train included Lieutenant Rice, of the Essex Regiment; Mr. R. Bayly, J.P., of Plymouth (who succeeded in getting through to his home on Wednesday) Miss Sykes, and a nurse who was travelling from Scarborough to the South Devon and East Cornwall Hospital, Plymouth."

It is only fair to the station-master at Brent, and to the residents of the town generally, to repeat that this description has been extensively contradicted, and among others, by Mr. Robert Bayly, of Plymouth, who was another of the detained passengers. Mr. Stumbles, however, has adhered to his description, and in more than one instance his version has been supported. Among other interesting details of the week in Brent, is the account of the arrival of the first newspaper, a copy of the Western Morning News, which was brought over from Totnes on the Thursday morning by an adventurous policeman, who successfully undertook the dangerous walk. This paper was eagerly sought after, it having been the first account of the doings in the outer world seen since Monday, and one of the enforced sojourners in Brent is said to have paid five shillings for the use of the paper for one hour. The fortunate possessor of the journal declared that he had been offered two pounds for it, and had declined to trade.

At Totnes a number of passengers were detained, among them being a reporter of the Western Morning News, who went to the town on Monday to report a meeting, and was only released on the following Friday night. A number of passengers who left Friary Station, Plymouth, by the 3·47 P.M. South Western train on Thursday, were taken into Tavistock on the following day, after having spent the night at Lydford. Instances innumerable of the same character occurring on the Launceston and other lines could be related, but as their points of interest bear such a strong resemblance to each other, it is unnecessary to proceed further with them.