This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

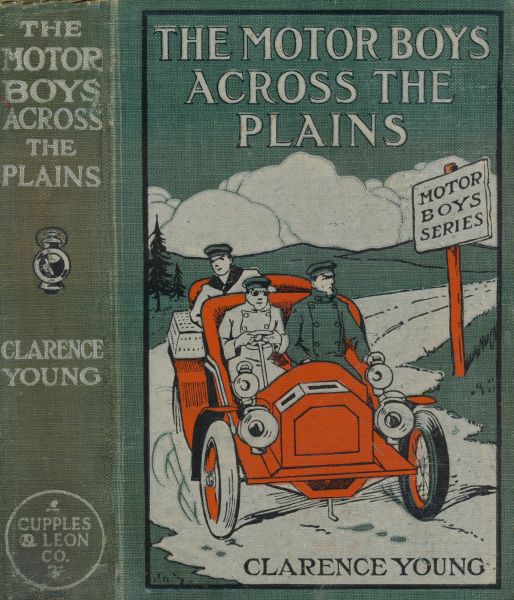

Title: The Motor Boys Across the Plains

or, The Hermit of Lost Lake

Author: Clarence Young

Release Date: August 19, 2013 [eBook #43509]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MOTOR BOYS ACROSS THE PLAINS***

Or

The Hermit of Lost Lake

BY

AUTHOR OF “THE MOTOR BOYS,” “THE MOTOR BOYS OVERLAND,”

“THE MOTOR BOYS IN MEXICO,” “JACK RANGER’S

SCHOOLDAYS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

THE MOTOR BOYS SERIES

(Trade Mark, Reg. U. S. Pat. Of.)

12mo. Illustrated

Price per volume, 60 cents, postpaid

THE MOTOR BOYS

Or Chums Through Thick and Thin

THE MOTOR BOYS OVERLAND

Or A Long Trip for Fun and Fortune

THE MOTOR BOYS IN MEXICO

Or The Secret of the Buried City

THE MOTOR BOYS ACROSS THE PLAINS

Or The Hermit of Lost Lake

THE MOTOR BOYS AFLOAT

Or The Stirring Cruise of the Dartaway

THE MOTOR BOYS ON THE ATLANTIC

Or The Mystery of the Lighthouse

THE MOTOR BOYS IN STRANGE WATERS

Or Lost in a Floating Forest

THE MOTOR BOYS ON THE PACIFIC

Or The Young Derelict Hunters

THE MOTOR BOYS IN THE CLOUDS

Or A Trip for Fame and Fortune

THE JACK RANGER SERIES

12mo. Finely Illustrated

Price per volume, $1.00, postpaid

JACK RANGER’S SCHOOLDAYS

Or The Rivals of Washington Hall

JACK RANGER’S WESTERN TRIP

Or From Boarding School to Ranch and Range

JACK RANGER’S SCHOOL VICTORIES

Or Track, Gridiron and Diamond

JACK RANGER’S OCEAN CRUISE

Or The Wreck of the Polly Ann

JACK RANGER’S GUN CLUB

Or From Schoolroom to Camp and Trail

Copyright, 1907, by

Cupples & Leon Company

The Motor Boys Across the Plains

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Ramming an Ox Cart | 1 |

| II. | A Nest of Serpents | 11 |

| III. | The Deserted Cabin | 20 |

| IV. | News from the Mine | 30 |

| V. | Trouble Ahead | 39 |

| VI. | On a Strange Road | 46 |

| VII. | The Rescue of Tommy Bell | 55 |

| VIII. | Pursued by Enemies | 65 |

| IX. | Into the Cave | 72 |

| X. | Attacked by a Cougar | 81 |

| XI. | A Runaway Auto | 90 |

| XII. | Tommy Finds a Friend | 98 |

| XIII. | The Colored Man’s Ghost | 107 |

| XIV. | Trouble With a Bad Man | 117 |

| XV. | The Story of Lost Lake | 127 |

| XVI. | A Lonely Cabin | 135 |

| XVII. | The Indian and the Auto | 144 |

| XVIII. | Lost Lake Found | 152 |

| XIX. | The Ghost of the Lake | 161 |

| XX. | The Mysterious Woman | 169 |

| XXI. | The Den of the Hermit | 175 |

| XXII. | A Revelation | 185 |

| XXIII. | Searching for the Hermit | 195 |

| XXIV. | The Hermit’s Identity | 203 |

| XXV. | Attacked by the Enemy | 212 |

| XXVI. | On the Road Again | 221 |

| XXVII. | Trouble at the Mine | 227 |

| XXVIII. | All’s Well that Ends Well | 237 |

| THE BEAR WAS TRYING TO CLIMB UP ON THE ENGINE HOOD. |

| THE INDIAN SEEMED TO KNOW HOW TO OPERATE IT. |

| THE NEXT INSTANT THE BOY HAD MADE A FLYING LEAP INTO THE CAR. |

Dear Boys:

Here it is at last—the fourth volume of “The Motor Boys Series,” for which so many boys all over our land have been asking during the past year.

To those who have read the other volumes in this line, this new tale needs no special introduction. To others, I would say that in the first volume, entitled, “The Motor Boys,” I introduced three wide-awake American lads, Ned, Bob and Jerry, and told how they first won a bicycle race and then a great motor cycle contest,—the prize in the latter being a big touring car.

Having obtained the automobile, the lads went west, and in the second volume, called, “The Motor Boys Overland,” were related the particulars of a struggle for a valuable mine, a struggle which tested the boys’ bravery to the utmost.

While in the west the boys heard of a strange buried city in Mexico, and, in company with a learned college professor, journeyed to that locality. The marvellous adventures met with are told in “The Motor Boys in Mexico.”

Leaving the buried city, the boys started again for the locality of the mine, and in the present tale are told the particulars of some strange things that happened on the way. A portion of this story is based on facts, related to me while on an automobiling tour in the west, by an old ranchman who had participated in some of the occurrences.

With best wishes, and hoping we shall meet again, I leave you to peruse the pages which follow.

Clarence Young.

March 1, 1907.

Mingled with the frantic tooting of an automobile horn, there was the shrill shrieking of the brake-band as it gripped the wheel hub in a friction clutch.

“Hi, Bob! Look out for that ox cart ahead!” exclaimed one of three sturdy youths in the touring car.

“I should say so! Jam on the brakes, Bob!” put in the tallest of the trio, while an elderly man, who was in the rear seat with one of the boys, glanced carelessly up to see what was the trouble.

“I have got the brake on, Jerry!” was the answer the lad at the steering wheel made. “Can’t you and Ned hear it screeching!”

The auto was speeding down a steep hill, seemingly headed straight toward a solitary Mexican[2] who was moving slowly along in an antiquated ox-drawn vehicle.

“Then why don’t she slow up? You’ve got the power off, haven’t you?”

“Of course! Do you take me for an idiot!” yelled Bob, or, as his friends sometimes called him, because of his fatness, “Chunky.” “Of course I’ve shut down, but something seems to be the matter with the brake pedal.”

“Have you tried the emergency?” asked Ned.

“Sure!”

Toot! Toot! Toot!

Again the horn honked out a warning to the Mexican, but he did not seem to hear.

The big red touring car was gathering speed, in spite of the fact that it was not under power, and it bore down ever closer to the ox cart.

“Cut out the muffler and let him hear the explosions,” suggested Jerry.

Bob did so, and the sounds that resulted were not unlike a Gatling gun battery going into action. This time the native heard.

Glancing back, he gave a frightened whoop and jabbed the sharp goad into the ox. The animal turned squarely across the road, thus shutting off what small chance there might have been of the auto gliding past on either side.

“We’re going to hit him sure!” yelled Ned. “I say Professor, you’d better hold on to your specimens. There’s going to be all sorts of things doing in about two shakes of a rattlesnake’s tail!”

“What’s that about a rattlesnake?” asked the old man, who, looking up from a box of bugs and stones on his lap, seemed aware, for the first time, of the danger that threatened.

“Hi there! Get out of the way! Move the cart! Shake a leg! Pull to one side and let us have half the road!” yelled Jerry as a last desperate resort, standing up and shouting at the bewildered and frightened Mexican.

“Oh pshaw! He don’t understand United States!” cried Ned.

“That’s so,” admitted Jerry ruefully.

“Vamoose, is the proper word for telling a Mexican to get out of the road,” suggested the professor calmly. “Perhaps if you shouted that at him he might—”

What effect trying the right word might have had the boys had no chance of learning, for, the next instant, in spite of Bob’s frantic working at the brake, the auto shot right at the ox cart. By the merest good luck, more than anything else, for Bob could steer neither to the right nor left, because the narrow road was hemmed in by high[4] banks, the machine struck the smaller vehicle a glancing blow.

The force of the impact skidded the auto on two wheels up the side of the embankment, where, poking the front axle into a stump served to bring the car to a stop. The car was slewed around to one side, the ox was yanked from its feet, and, as the cart overturned, the Mexican, yelling voluble Spanish, pitched out into the road.

Nor did the boys and the professor come off scathless, for the sudden stopping of their machine piled the occupants on the rear seat up in a heap on the floor of the tonneau, while Bob and Jerry, who were in front, went sprawling into the dust near the native.

For a few seconds there was no sound save the yelling of the Mexican and the bellowing of the ox. Then the cloud of dust slowly drifted away, and Bob picked himself up, gazing ruefully about.

“This is a pretty kettle of fish,” he remarked.

“I should say it was several of ’em,” agreed Jerry, trying to get some of the dust from his mouth, ears and nose. “You certainly hit him, Chunky!”

“It wasn’t my fault! How did I know the brake wasn’t going to work just the time it was most needed?”

“Is anybody killed?” asked the professor, looking up over the edge of the tonneau, and not releasing his hold of several boxes which contained his specimens.

“Don’t seem to be, nor any one badly hurt, unless it’s the ox or the auto,” said Ned, taking a look. “The Mexican seems to be mad about something, though.”

By this time the native had arisen from his prostrate position and was shaking his fist at the Motor Boys and the professor, meanwhile, it would appear from his language, calling them all the names to which he could lay his tongue.

“I guess he wants Bob’s scalp,” said Jerry with a smile.

“It was as much his fault as mine,” growled Chunky. “If he had pulled to one side, I could easily have passed.”

The Mexican, brushing the dust from his clothes, approached the auto party, and continued his rapid talk in Spanish. The boys, who had been long enough in Mexico to pick up considerable of the language, gathered that the native demanded two hundred dollars for the damage to himself, the cart and the ox, as well as for the injury to his dignity and feelings.

“You’d better talk to him, Professor,” suggested[6] Jerry. “Offer him what you think is right.”

Thereupon Professor Snodgrass, in mild terms explained how the accident had happened, saying it was no fault of the auto party.

The Mexican, in language more forcible than polite, reiterated his demand, and announced that unless the money was instantly forthcoming, he would go to the nearest alcade and lodge a complaint.

The travelers knew what this meant, with the endless delays of Mexican justice, the summoning of witnesses and petty officers.

“I wish there was some way out,” said Jerry.

As the Mexican had not been hurt, nor his cart or ox been damaged, there was really no excuse for the boys giving in to his demands.

“Let’s give him a few dollars and skip out,” suggested Ned. “He can’t catch us.”

This was easier said than done, for the auto was jammed up against a tree stump on a bank, and the ox cart, which, the native by this time had righted, blocked the road.

But, all unexpectedly, there came a diversion that ended matters. Professor Snodgrass, with his usual care for his beloved specimens before himself, was examining the various boxes containing[7] them. He opened one containing his latest acquisition of horned toads, big lizards, rattlesnakes and bats. The reptiles crawled, jumped and flew out, for they were all alive.

“Diabalo! Santa Maria! Carramba!” exclaimed the Mexican as he caught sight of the repulsive creatures. “They are crazy Americanos!” he yelled.

With a flying leap he jumped into his ox cart, and with goad and voice he urged the animal on to such advantage that, a few minutes later, all that was to be seen of him was a cloud of dust in the distance.

“Good riddance,” said Bob. “Now to see how much our machine is damaged.”

Fortunately the auto had struck a rotten stump, and though with considerable force, the impact was not enough to cause any serious damage. Under the direction of Jerry the boys managed to get the machine back into the road, where they let it stand while they went to a near-by spring for a drink of water.

While they are quenching their thirst an opportunity will be taken to present them to the reader in proper form.

The three boys were Bob Baker, son of Andrew Baker, a banker, Ned Slade, the only heir of Aaron[8] Slade, a department store proprietor, and Jerry Hopkins, the son of a widow. All three were about seventeen years of age, and lived in the city of Cresville, not far from Boston, Mass. Their companion was Professor Uriah Snodgrass, a learned man with many letters after his name, signifying the societies and institutions to which he belonged.

Those who have read the first book of this series, entitled, “The Motor Boys,” need no introduction to the three lads. Sufficient to say that some time before this story opens they had taken part in some exciting bicycle races, the winning of which resulted in the acquiring of motor cycles for each of them.

On these machines they had had much fun and had also many adventures befall them. Taking part in a big race meet, one of them won an event which gave him a chance to get a big touring automobile, the same car in which they were now speeding through Mexico.

Their adventures in the auto are set forth at length in the second volume of the series entitled, “The Motor Boys Overland,” which tells of a tour across the country, in which they had to contend with their old enemy, Noddy Nixon, and his gang. Eventually the boys and Jim Nestor, a[9] miner whom they befriended, gained some information of a long lost gold mine in Arizona.

They made a dash for this and won it against heavy odds, after a fight with their enemies. The mine turned out well, and the boys and their friends made considerable money.

The spirit of adventure would not drown in them. Just before reaching the diggings they made the acquaintance of Professor Snodgrass, who told a wonderful story of a buried city. How the boys found this ancient town of old Mexico, and the many adventures that befell them there, are told in the third book, called “The Motor Boys in Mexico.”

Therein is related the strange happenings under ground, of the sunken road, the old temples, the rich treasures and the fights with the bandits. Also there is told of the rescue of the Mexican girl Maximina, and how she was taken from a band of criminals and restored to her friends.

These happenings brought the boys and the professor to the City of Mexico, where the auto was given a good overhauling, to prepare it for the trip back to the United States.

The boys and the professor, the latter bearing with him his beloved specimens, started back for civilization, keeping to the best and most frequented[10] roads, to avoid the brigands, with whom they had had more than one adventure on their first trip. It was while on this homeward journey that the incident of the Mexican and the ox cart befell them.

Having slaked their thirst the boys and the professor went back to the auto where, gathering up the belongings that had become scattered from the upset, they prepared to resume their journey.

“Get in; I’ll run her for a while,” said Jerry.

“One minute! Stand still! Don’t move if you value my happiness!” exclaimed the professor suddenly, dropping down on his hands and knees, and creeping forward through the long grass.

“What is it; a rattlesnake?” asked Bob, in a hoarse whisper.

“Or a Gila monster?” inquired Ned.

“Quiet! No noise!” cautioned the professor. “I see a specimen worth ten dollars at the lowest calculation. I’ll have him in a minute.”

“Is it a bug?” asked Chunky.

“There! I have him!” yelled the scientist, making a sudden dive forward, sliding on his face, and clutching his hand deep into the grass.

As it happened there was a little puddle of water at that point, and the professor, in the excess of his zeal, pitched right into it.

“Oh! Oh my! Oh dear! Phew! Wow! Help! Save me!” he exclaimed a moment later, as he tried to get out of the slough.

The boys hurried to his aid, but the mud was soft and the professor had gone head first into the ooze, which held fast to him as though it was quicksand.

“Get him by the heels and yank him out or he’ll smother!” cried Jerry.

The other boys followed his advice, and, in a little while the bug-collector was pulled from his uncomfortable and dangerous position. As he rolled about in the grass to get rid of some of the mud, he kept his right hand tightly closed.

“What’s the matter, are your fingers hurt?” asked Bob.

“No sir, my fingers are not hurt!” snapped the professor, with the faintest tinge of impatience, which might be excused on the part of a man who has just dived into a mud hole. “My fingers are not hurt in the least. What I have here is one of the rarest specimens of the Mexican mosquito I have ever seen. I would go ten miles to get one.”

“I guess you’re welcome to ’em,” commented Jerry. “We don’t want any.”

“That’s because you don’t understand the value of this specimen,” replied the professor. “This mosquito will add to my fame, and I shall devote one whole chapter of my four books to it. This indeed has been a lucky day for me.”

“And unlucky for the rest of us,” said Bob, as he thought of the spill.

It was found that a few minor repairs had to[13] be made to the auto, and when these were completed it was nearly noon.

“I vote we have dinner before we start again,” spoke Bob.

“There goes Chunky!” exclaimed Ned. “Never saw him when he wasn’t thinking of something to eat!”

“Well, I guess if the truth was known you are just as hungry as I am,” expostulated Chunky. “This Mexican air gives me a good appetite.”

Bob’s plan was voted a good one, so, with supplies and materials carried in the auto for camping purposes, a fire was soon built, and hot chocolate was being made.

“I’m sick of canned stuff and those endless eggs, frijoles and tortillas,” complained Bob. “I’d like a good beefsteak and some fish and bread and butter.”

“I don’t know about the other things, but I think we could get some fish over in that little brook,” said the professor, pointing to a stream that wound about the base of a near-by hill.

A minute later the boys had their hooks and lines out. Poles were cut from trees, and, with some pieces of canned meat for bait they went fishing. They caught several large white fish, which[14] the professor named in long Latin terms, and which, he said, were good to eat.

In a little while a savory smell filled the air, for Ned, who volunteered to act as cook, had put the fish on to broil with some strips of bacon, and soon there was a dinner fit for any king that ever wielded a scepter.

Sipping their chocolate, the boys and the professor watched the sun slowly cross the zenith as they reclined in the shade of the big trees on either side of the road. Then each one half fell asleep in the lazy atmosphere.

Jerry was the first to rouse up. He looked and saw it would soon be dusk, and then he awakened the others.

“We’ll have to travel, unless we want to sleep out in the open,” he said.

Thereupon they made preparations to leave, the professor gathering up his specimens, including the Mexican mosquito that had caused him such labor.

“I think we’ll head straight for the Rio Grande,” said Jerry. “Once we get into Texas I expect we’ll have some news from Nestor, as I wrote him to let us know how the mine was getting on, and, also, to inform us if he needed any help.”

“I’ll be glad to see old Jim again,” said Bob.

“So will I,” chimed in Ned.

The auto was soon chug-chugging over the road, headed toward the States, and the occupants were engaged with their thoughts. It was rapidly growing dusk, and the chief anxiety was to reach some town or village where they could spend the night. For, though they were used to staying in the open, they did not care to, now that the rainy season was coming on, when fevers were prevalent.

The sun sank slowly to rest behind the big wooded hills as the auto glided along, and, almost before the boys realized it, darkness was upon them.

“Better light the lamps,” suggested Ned. “No telling what we’ll run into on this road. No use colliding with more ox carts, if we can help it.”

“I’ll light up,” volunteered Bob. “It will give me a chance to stretch my legs. I’m all cramped up from sitting still so long.”

Jerry brought the big machine to a stop while Bob alighted and proceeded to illuminate the big search lamp and the smaller ones that burned oil. He had just started the acetylene gas aglow when, glancing forward he gave a cry of alarm.

“What is it?” cried Jerry, seeing that something was wrong. “Is it a mountain lion?”

“It’s worse!” cried Bob in a frightened voice.

“What?”

“A regular den of snakes! The horrible things are stretched right across the road, and we can’t get past. Ugh! There are some whoppers!”

Bob, who hated, above all creatures a snake, made a jump into the auto.

“There’s about a thousand of ’em!” he cried with a shudder.

“Great!” exclaimed the professor. “I will have a chance to select some fine specimens. This is a rare fortune!”

“Don’t go out there!” gasped Bob. “You’ll be bitten to death!”

Just then there sounded on the stillness of the night a strange, whirring buzz. At the sound of it the professor started.

“Rattlers!” he whispered. “I guess none of us will get out. Probably moccasins, cotton-mouths and vipers! There must be thousands of them!”

As he spoke he looked over the side of the car, and the exclamation he gave caused the boys to glance toward the ground. There they beheld a sight that filled them with terror.

As the professor had said, the ground was literally covered with the snakes. The reptiles seemed to be moving in a vast body to some new location.[17] There were big snakes and little ones, round fat ones, and long thin ones, and of many hues.

“Let’s get out of this!” exclaimed Ned. “Start the machine, Jerry!”

“No! Don’t!” called the professor. “You may kill a few, but the revolving wheels of the auto will fling some live ones up among us, and I have no desire to be bitten by any of these reptiles. They are too deadly. So keep the car still until they have passed. They are probably getting ready to go into winter quarters, or whatever corresponds to that in Mexico.”

“It will be lucky if they don’t take a notion to climb up and investigate the machine and us,” put in Jerry. “I have—”

He gave a sudden start, for, at that instant one of the ugly reptiles, which had twined itself around the wheel spokes, reared its ugly head up, over the side of the front seat, and hissed, right in Jerry’s face.

“Here’s one now!” the boy exclaimed as he made a motion to brush the snake aside.

“Don’t touch it as you value your life!” yelled the professor. “It’s a diamond-backed rattler, and one of the most deadly!”

“Here is another coming up on my side,” called Bob.

“Yes, and there are some coming up here!” shouted Ned. “They’ll overwhelm us if we don’t look out!”

For a time it seemed a serious matter. The snakes began twining up the sides of the car, and, though most of them dropped back to the ground again, a few maintained their position, and seemed to exhibit anger at the sight of the boys and the professor.

“What shall we do?” asked Bob. “We can’t run ahead, or go backward, and, if we stay here we’re likely to be killed by the snakes.”

Jerry, who was feeling around in the bottom of the car for his rifle, gave a cry as his hand came in contact with something.

“Get bitten?” asked the professor in alarm.

“No, but I found this lariat,” said Jerry in excited tones.

“Are you going to lasso the snakes?” asked Ned, wondering if Jerry had gone crazy.

“No, but you see this lariat is made of horse hair, and I think I can keep the snakes away with it.”

“How; by shaking it at ’em?”

“No. I read in some book that snakes hated horse hair, and would never cross even a small ring of it.”

“Well?”

“Well, if I run this lariat all around the auto the snakes will not cross it to come to us. Then we can stay here until they all disappear.”

“Good!” exclaimed Ned. “That’s the ticket!”

The reptiles that had climbed up the wheels had gone from sight. With the help of Ned and Bob, Jerry began to spread the horse-hair lariat in a circle about the car.

In a few minutes the hair rope was all about the auto, spread out on the ground in an irregular circle. As the boys dropped it over the sides of the car the lariat struck several of the big snakes, and the reptiles shrunk away as though scorched by fire.

“They’re afraid of it all right!” exclaimed Ned. “I guess it will do the business.”

Sure enough, there seemed to be a desire on the part of the snakes to clear out of the vicinity of the hair rope. They glided off by scores, and soon there was a clear space all about the car, where, before, there had been hundreds of the crawling things.

“Shake the lasso,” suggested Bob, “and maybe it will scare them farther off.”

“Yes and we might try shooting a few now they are at a safe distance,” put in Ned.

“It’s too bad I can’t get some specimens,” lamented[21] the professor, “but I suppose you had better try to get rid of them.”

So Jerry, who had retained one end of the long lasso vibrated it rapidly, and, as it wiggled in sinuous folds toward the reptiles they made haste to get out of the way. Then Bob and Ned opened fire, killing several. In a little while there were no snakes to be seen.

“I guess we can go ahead now,” said Jerry. “Who’ll crank up the car? Don’t all speak at once.”

“My arm is a bit sore,” spoke Ned, rubbing his elbow.

“Then you do it, Chunky,” asked the steersman.

“I think I have a stone in my foot,” said Bob, making a wry face.

“Ha! Ha!” laughed Jerry. “Why don’t you two own up and say you’re afraid there’s a stray rattler or two under the machine, and you think it may bite you?”

The two boys grinned sheepishly, and both made a motion to get out.

“Stay where you are,” called the professor preparing to leave from the side door of the tonneau. “I’m used to snakes. I don’t believe there are any left, but if there are I want them for specimens. I’ll crank the car.”

So he got out and peered anxiously under the body, while the boys waited in anxiety.

“No,” called the scientist, in discouraged tones, “there are none left.”

He crawled out, covered with dust, which fact he did not seem to mind, and then turned the crank that sent the fly wheel over. Jerry turned on the gasolene and threw in the spark, and, the next instant the familiar chug-chug of the engine told that the auto was ready to bear the boys and Professor Snodgrass on their way.

They were headed on as straight a road as they could find to the Rio Grande, but, because of the conditions of the thoroughfares it would be several days before they could cross the big river and get into Texas. Their main concern now was to reach some place where there was shelter for the night.

“Keep your eyes peeled for villages,” called Ned. “We don’t want to pass any. I think a good bed would go fine now.”

“A supper would go better,” put in Bob.

“Oh, of course! It wouldn’t be Chunky if he didn’t say something about eating,” remarked Jerry with a laugh. “But there seems to be something ahead. It’s a house at all events, and probably is the mark of the outskirts of the village.”

On the left side of the road, about a hundred[23] yards ahead they saw an adobe, or mud hut. They could see no signs of life about in the half-darkness, illuminated as it was by the powerful search light, but this gave them no concern, as they knew the native Mexicans retired early.

When they came opposite the hut Jerry brought the machine to a stop, and he and the other boys jumped out. The professor, who, as usual was arranging some specimens in one of the many small boxes he carried, remained in the car.

“Hello!” shouted Bob. “Is any one home? Show a light. Can we get a supper here?”

“Why don’t you ask for a bed too?” inquired Ned.

“Supper first,” replied Chunky, rubbing his stomach with a reflective air.

No replies came to the hail of the boys, and, in some wonder they approached nearer to the hut. Then they saw that the door was ajar, and that the cabin bore every appearance of being deserted.

“Nobody home, I guess,” said Jerry.

“No, and there hasn’t been for some time,” added Ned.

“Maybe there’s a place to build a fire where we can cook a good meal,” put in Bob, whereat his companions laughed.

They went into the hut, and found, that, while[24] it was in good condition, and furnished as well as the average native Mexican’s abode, there was no sign of life.

“Might as well make ourselves to home,” said Ned. “Come on in, professor,” he called. “We’ll stay here all night. No use traveling further when there is such a good shelter right at hand.”

It was now quite dark, and the boys brought in the two oil lamps from the auto, as well as a lantern, to illuminate the place. As they did so they disturbed a colony of bats which flew out with a great flutter of wings.

“There’s a charcoal stove, and plenty of fuel,” said Bob, as he looked at the hearth. “Now we can cook something.”

“Well, seeing you are so fond of eating, we’ll let you get the meal,” said Jerry, and it was voted that Chunky should perform this office.

Meanwhile the others brought in blankets to make beds on the frame work of cane that formed the sleeping quarters of whoever had last lived in the hut.

“Rather queer sort of a shack,” remarked Jerry, as he sat down in a corner on a pile of rugs. “Seems to have been left suddenly. They didn’t even stop to take the dishes, and here is the remains[25] of a meal,” and he pointed to some dried frijoles in one corner of the main room or kitchen.

“Perhaps the people who lived here were frightened away,” came from Ned.

“Well I’m tired enough not to let anything short of a regiment of soldiers in action scare me awake to-night,” said Jerry.

Under Bob’s direction supper was soon ready, and the travelers sat down to a good, if rather limited meal as far as variety went. There were no dishes to be washed, for they ate off wooden plates, of which they had a quantity and which they threw away after each meal. Then, after a good fire had been built on the hearth—for the night was likely to be chilly—the boys and the professor wrapped themselves up in their blankets and soon fell asleep.

Jerry must have been slumbering for several hours when he suddenly awakened as he heard a loud noise.

“Who’s there?” he called involuntarily, sitting up.

It was so dark that at first he could distinguish nothing, but, as his eyes became used to the blackness he managed to make out, by the glow of the fire, a shadowy figure gliding toward the door.

“Who’s there?” called the boy sharply, feeling[26] under the rolled up blanket that served for a pillow, for his revolver. “Stop or I’ll fire!”

The shadowy figure halted. Then Jerry saw it drop down on all fours and begin to creep toward him. Though he was not a coward the boy felt his heart beating strangely, and he had a queer, creepy sensation down his spine.

“What’s the matter?” asked Ned, who was awakened by Jerry’s voice.

“Get your revolver, quick!” called Jerry. “There is some one in the hut besides ourselves! Look over by the fire!”

“I see it! Shall I shoot?” asked Ned.

There came a sudden crash, followed by a wild yell.

“Help! Help! I’m killed! They are murdering me!” shouted Bob’s voice. “They are choking me to death!”

Bang! went Ned’s gun.

Fortunately it was aimed at the ceiling, or some one might have been hurt.

“What’s the trouble?” inquired the professor, who only just then awoke.

“Robbers!” yelled Bob.

“Brigands!” exclaimed Ned.

“Some one is in the cabin!” cried Jerry.

By this time he had managed to creep over[27] toward the fire, on which he threw some light wood. The glowing embers caught it, and as the blaze flared up it revealed a big monkey tangled up amid the folds of Bob’s blanket, while Chunky was buried somewhere beneath the pile. The beast was struggling wildly to escape, but Bob, in his terror, had grabbed it by a leg.

“Stop your noise!” commanded Jerry. “You’re not hurt, Chunky!”

“Are you sure they haven’t killed me?” asked Bob, releasing his hold on the beast, which, with a wild chatter of fear, fled from the hut.

“You ought to be able to give the best evidence on that score,” said Jerry, as he lighted one of the lamps.

“The fellow tried to choke me,” sputtered Bob.

“I guess the poor beast was as badly scared as you were,” remarked the professor. “It was probably attracted in here by the light and warmth. Well, we seem bound to run up against excitement, night as well as day.”

“The monkey must have knocked something over,” said Jerry. “I was awakened by the sound of something falling.”

They looked and saw that the beast had tried to eat the remains of the supper, and had upset a big pot.

“I was sure it was a man, at first,” explained Jerry, “and when I saw it go down and start over toward me I was afraid it was some of those Mexican brigands that traveled with Vasco Bilette and Noddy Nixon, when those rascals were on our trail.”

It was some time before the excitement caused by the monkey’s visit died down sufficiently to allow the travelers to go to sleep again. It was morning when they awoke, and prepared to get breakfast.

“We need some water to make coffee,” said Jerry, who had agreed to get the morning meal. “As chief cook and bottle washer I delegate Bob to find some. Take the pail in the auto.”

Bob started for the receptacle, and, as he reached the door of the hut he gave a cry.

“What’s the matter?” called Jerry and Ned.

“There’s a man out here,” replied Bob.

“Well, he won’t bite you,” said Jerry. “Who is he?”

“Pardon, senors,” called a voice, and then, into the hut staggered a Mexican, who bore evidences of having passed through a hard fight. His face was cut and bruised, one arm hung limply at his side, and his clothing was torn.

“What’s the matter?” cried Jerry.

Before the stranger could reply he had fallen forward in a faint.

“Bring some water! Quick!” called Ned.

“Let me see to him! I have a little liquor here!” exclaimed the professor, kneeling down beside the prostrate form.

By the use of the strong stimulant the Mexican was revived. His eyes opened, and he sat up, muttering something in Spanish which the boys could not catch.

The professor, however, made reply, and, at the words the stranger seemed to brighten up. He drank some water, and then, at the suggestion of Mr. Snodgrass the boys brought him some food, which the native ate as if he had fasted for a week.

His hunger satisfied, he began to talk rapidly to the professor, who listened attentively.

“What’s the trouble?” asked Jerry at length.

“It seems that the poor man lives in this hut,” explained the scientist. “Night before last some robbers came in, took nearly everything he had and beat him. Then, driving him into the forest they left him. Only just now did he dare to venture back, fearing to find his enemies in possession of his home. He is weak from lack of food and from the treatment he received.”

The boys felt sorry for the Mexican, and, at Jerry’s suggestion they gave him a sum of money, which, while it was small enough to the travelers, meant a great deal to the native. He poured forth voluble thanks.

As the boys and the professor were anxious to get under way, a start was made as soon as it was found that the native was not badly hurt, and that he was able to summon help from friends in a near-by village if necessary. With final leave-takings the travelers started off.

For several days and nights they journeyed north, toward the Rio Grande, which river separated them from the United States. Once they crossed that they would be in Texas.

“And we can’t get there any too soon,” remarked Bob, one morning after a sleepless night, passed in the open, during which innumerable fleas attacked the travelers.

It was toward dusk, one evening, about a week after having left the City of Mexico that the boys and the professor found themselves on a road, which, upon inquiry led to a small Mexican town, on the bank of the Rio Grande, nearly opposite Eagle Pass, Texas.

“Shall we cross over to-night or wait until morning?” asked the professor of the boys. “Probably[32] it would be better to wait until daylight. I could probably gather a few more specimens then.”

This was something of which the scientist, who rejoiced in such letters as A.M.; Ph.D.; M.D.; F. R. G. S.; A. G. S., etc., after his name, all indicating some college honor conferred upon him, never seemed to tire. He was making a collection for his own college, as well as gathering data for four large books, which, some day, he intended to issue.

“I’d rather get over on our land if we can,” said Ned, and he seemed to voice the sentiments of the others.

So it was decided, somewhat against the professor’s wish, to run the automobile on the big flat-bottomed scow, which served as a ferry, and proceed across the stream.

Quite a crowd of villagers came out to see the auto as it chug-chugged up to the ferry landing, and not a few of the children and dogs were in danger of being run over until Ned, who was steering, cut out the muffler, and the explosions of the gasolene, unconfined by any pipes, made so much noise that all except the grown men were frightened away.

There was no one at the ferry house, and after diligent inquiries it was learned that the captain[33] and crew of the boat had gone off to a dance about five miles away.

“I guess we’ll have to stay on this side after all,” remarked the professor. “I think—”

What he thought he did not say, for just then he happened to catch sight of something on the shoulder of one of the Mexicans, who had gathered in a fringe about the machine.

“Stand still, my dear man!” called the professor, as with cat-like tread he crept toward the native.

“Diabalo! Santa Maria! Carramba!” muttered the man, thinking, evidently, that the old scientist was out of his wits.

“Don’t move! Please don’t move!” pleaded Mr. Snodgrass, forgetting in his excitement that his hearer could not understand his language. “There is a beautiful specimen of a Mexican katy-did on your coat. If I get it I will have a specimen worth at least thirty dollars!”

He made a sudden motion. The Mexican mistook the import of it, and, seemingly thinking he was about to be assaulted, raised his hand in self defense, and aimed a blow at the professor.

It was only a glancing one, but it knocked the scientist down, and he fell into the road.

“There, the katy-did got away after all,” Mr.[34] Snodgrass exclaimed, not seeming to mind his personal mishap in the least.

This time the professor spoke in Spanish. The Mexican understood, and was profuse in his apologies. He conversed rapidly with his companions, and, all at once there was a wild scramble after katy-dids. So successful was the hunt that the professor was fairly burdened with the insects. He took as many as he needed, and thanked his newly found friends for their efforts.

Matters quieted down after a bit. Darkness fell rapidly and, the Mexican on whom the professor had seen the katy-did invited the travelers to dine with him.

He proved to be one of the principal men of the village, and his house, though not large, was well fitted up. The boys and the professor enjoyed the best meal they had eaten since leaving the City of Mexico.

“Do me the honor to spend the night here,” said the Mexican, after the meal.

“Thank you, if it will not disturb your household arrangements, we will,” replied the professor. “We must make an early start, however, and cross the river the first thing in the morning.”

“It will be impossible,” replied Senor Gerardo, their host.

“Why so?”

“Because to-morrow starts the Feast of San Juarez, which lasts for three days, and not a soul in town, including the ferry-master, will work in that time.”

“What are we to do?” asked Mr. Snodgrass.

“If you do not cross to-night you will not be able to make the passage until the end of the week,” was the answer.

“Then let’s start to-night,” spoke Jerry. “We went over the Rio Grande after dark once before.”

“Yes, and a pretty mess we made of it,” said Ned, referring to the collision they had with the house-boat, as told of in “The Motor Boys in Mexico.”

“But I thought they said the ferry-master was away to a dance,” put in Bob.

“He is, Senor,” replied their host, who managed to understand the boy’s poor Spanish. “However, if he knew the Americanos wanted him, and would go for him in their big marvelous—fire-spitting wagon, and—er—that is if they offered him a small sum, he might be prevailed upon to leave the dance.”

“Let’s try it, at all events,” suggested Jerry. “I’m anxious to get over the line and into the United States. A stay of several days may mean[36] one of a week. When these Mexicans get feasting they don’t know when to stop.”

He spoke in English, so as not to offend their kind friend.

It was arranged that Jerry and Senor Gerardo should go in the auto for the ferry-master, and summon him to the river with his men, who could come on their fast ponies.

This was done, and, though the master of the boat demurred at leaving the pleasures of the dance, he consented when Jerry casually showed a gold-piece. He and his men were soon mounted and galloped along, Jerry running the auto slowly to keep pace with them. The five miles were quickly covered and, while half the population of the village came out to see the strange machine ferried over, the boys and the professor bade farewell to the country where they had gone through so many strange adventures.

It was nearly ten o’clock when the big flat-bottomed boat grounded on the opposite shore of the Rio Grande.

“Hurrah for the United States!” exclaimed Bob. “Now I can get a decent meal without having to swallow red peppers, onions and chocolate!”

“There goes Chunky again,” laughingly complained Ned. “No sooner does he land than he[37] wants to feed his stomach. I believe if he had been with Christopher Columbus the first thing he would have inquired about on landing at San Salvador would be what the Indians had good to eat.”

“Oh you’re as bad as I am, every bit!” said Bob.

Eagle’s Pass, where the travelers landed, was a typical Texas town, with what passed for a hotel, a store and a few houses where the small population lived. It was on the edge of the border prairies and the outlying districts were occupied by cattle ranches.

Nearly all, if not quite all, of the male population came down to the dock to see the unusual sight of a big touring automobile on the ferry boat. Many were the comments made by the ranchmen and herders.

After much pulling and hauling the car was rolled from the big scow, and the travelers, glad to feel that they were once more in their own country, began to think of a place to spend the night.

“Where is the nearest hotel?” asked Jerry of a man in the crowd.

“Ain’t but one, stranger, an’ it’s right in front of you,” was the reply, as the cowboy pointed to a[38] small, one story building across the street from the river front.

“Is Professor Driedgrass in that bunch?” asked a voice as the travelers were contemplating the hostelry. “If he is I have a letter for him.”

“I am Professor Snodgrass,” replied the scientist, looking toward the man who had last spoken.

“Beg your pardon, Professor Snodgrass. I kinder got my brands mixed,” the stranger went on. “Anyhow I’m th’ postmaster here, an’ I’ve been holdin’ a letter for ye most a week. It says it’s to be delivered to a man with three boys an’ a choo-choo wagon, an’ that description fits you.”

“Where’s it from?” asked Mr. Snodgrass.

“Come in a letter to me, from a feller named Nestor, up at a place in the mining section,” was the reply. “Th’ letter to me said you might likely pass this way on your journey back.”

“I remember now, I did write to Nestor, telling him we were about to start back, and would probably cross the river at this place,” spoke the professor. “I had forgotten all about it.”

“Well, here’s your letter,” said the postmaster. “Now allow me to welcome you to our city, which I do in the name of the Mayor—which individual you see in me—and the Common Council, which consists of Pete Blaston, only he ain’t here, in consequent of bein’ locked up for disturbin’ th’ peace an’ quiet of the community by shootin’ a Greaser.”

“Glad to meet you, I am sure,” replied the scientist politely, as he received the letter from the dual official.

“What is the news from Nestor?” asked Jerry anxiously. “Is the mine all right?”

“I’ll tell you right away,” replied Mr. Snodgrass, as, by the light of the gas lantern on the auto he read the letter.

As he glanced rapidly over the pages his face took on an anxious look.

“Is there anything wrong?” asked Ned.

“There is indeed,” replied the professor gravely. “The letter was written over a week ago, and, among other things Nestor says there is likely to be trouble over the mine.”

“What kind? Is Noddy Nixon trying to get it away from us again?” asked Jerry.

“No,” replied Mr. Snodgrass. “It appears our title is not as good as it might be. There is one of the former owners of the land where the mine is located who did not sign the deed. He was missing when the transfer was made, but Nestor did not know this, so there is a cloud on our title.”

“But I thought we claimed the land from the government, and were the original owners,” put in Ned.

“It seems that a company of men owned the mine before we did, but they sold out to Nestor and some of his friends. They all signed the deed but this one man, and now some one has learned of this, and seeks to take the mine, on the theory that they have as good a claim to the holding as we have.”

“I should say that was trouble,” sighed Bob.[41] “To think of losing what we worked so hard to get!”

“Well, there’s no use crossing a bridge until you come to it,” Professor Snodgrass went on. “Nestor and his friends are in possession yet, and that, you know, is nine of the ten points of the law.”

“Then if we can’t do anything right away I move we have something to eat,” suggested Bob.

“It’s a good suggestion,” agreed the scientist.

They had drawn a little to one side from the crowd of townspeople while talking about the letter from Nestor, but, having decided there was nothing to be done at present, they moved toward the hotel.

“I reckon I’ve got some more mail for your outfit, Professor Hayseed—er I beg yer pardon—Snodgrass,” said the postmaster-mayor. “There’s letters fer chaps named Baker, Slade and Hopkins. Nestor sent ’em along with that other,” and the dual official handed over three envelopes.

“They’re from home!” cried the boys in a chorus. And in the glare of oil lamps on the porch of the hotel they read the communications.

The missives contained nothing but good news, to the effect that all the loved ones were well. Each one inquired anxiously how much longer the[42] travelers expected to stay away, and urged them to come home as soon as they could.

“Now for that supper!” exclaimed Bob, as he put his letter away.

If the meal was a rough one, prepared as it was by the Chinese cook, it was good, and the travelers enjoyed it thoroughly. As they rose from the table a cowboy entered the dining room and drawled out:

“I say strangers, be you th’ owners of that there rip-snortin’ specimen of th’ lower regions that runs on four wheels tied ’round with big sassages?”

“Do you mean the automobile?” asked Jerry.

“I reckon I do, if that’s what ye call it.”

“Yes, it’s our machine,” replied Jerry.

“Then if ye have any great love for th’ workin’ of it in the future, an’ any regard or consideration for it’s feelin’ ye ought t’ see to it.”

“Why so?”

“Nothin’,” drawled the cowboy as he carefully pared his nails with a big bowie knife; “nothin’ only Bronco Pete is amusin’ his self by tryin’ t’ see how near he can come to stickin’ his scalpin’ steel inter th’ tires!”

“Great Scott! We must stop that!” exclaimed Jerry, running from the hotel toward[43] where the auto had been left in the street. The other boys and the professor followed.

They found the machine surrounded by quite a crowd that seemed to be much amused at something which was taking place in its midst. Making their way to the inner circle of spectators the boys beheld an odd sight.

A big cowboy, who, from appearances had indulged too freely in something stronger than water, was unsteadily trying to stick his big knife into the rubber tires.

“Here! You mustn’t do that,” cried Jerry, sharply, laying his hand on the man’s shoulder.

“Look out for him! He’s dangerous!” warned some of the bystanders.

“I can’t help it if he is,” replied Jerry. “We can’t let him ruin the tires.”

“This is the time I do it!” cried Bronco Pete, as he made a lunge for the front wheel. Jerry sprang forward and the crowd held its breath, for it seemed as if the boy was right in the path of the knife.

But Jerry knew what he was about. With a quick motion he kicked the cowboy lightly on the wrist, the blow knocking the knife from his hand, and sending it some distance away.

“Look out now, sonny!” called a man to[44] Jerry. “No one ever hit Pete an’ lived after it.”

It seemed that Jerry was in a dangerous position. Pete, enraged at being foiled of his purpose, uttered a beast-like roar, and reached back to where his revolver rested at his hip in a belt. Jerry never moved an inch, but looked the man straight in the eye.

“Here! None of that Pete!” called a voice suddenly, and a big man pushed his way through the crowd, and grabbed the cowboy’s arm before he had time to draw his gun. “If you don’t want to get into trouble move on!”

“All right, Marshall; all right,” replied Pete, the desire of shooting seeming to die out as he looked at the newcomer. “I were only havin’ a little fun with th’ tenderfoot.”

“You didn’t appear to scare him much,” remarked the town marshall, who had seen the whole thing. “You had your nerve with you all right, son,” he added, to Jerry.

“That’s what he had,” commented Pete. “There ain’t many men would have done what he did, an’ I admire him for it. Put it there, stranger,” and Pete, all the anger gone from him, extended a big hand, which Jerry grasped heartily.

“Three cheers for the ‘tenderfoot,’” called some one, and they were given with a will for[45] Jerry, as Pete, under the guidance of the marshall, moved unsteadily away.

“I wouldn’t have been in your boots one spell there, for a good bit,” observed the postmaster as he came up. “Pete’s about as bad as they come.”

“I didn’t stop to think of the danger, or maybe I wouldn’t have done as I did,” said Jerry. “All I thought of was that he would spoil the tire, and it would take a long while to fix it.”

“Yes, and we don’t want to delay any longer than we can help,” spoke Ned in a low voice. “I’m anxious to get back to the mine and see what we can do to perfect our title.”

For several days they made good progress, for the roads were in fair condition. The machine was kept headed as nearly as possible toward Arizona, though they often had to go some distance out of their way to get rid of bad places, or find a ford or bridge to cross a stream.

“We’ll soon be out of Texas,” remarked Bob one afternoon, when they had passed through a small ranch town where they had dinner.

“And I think we’re going to get a wetting before we leave the big state,” put in Ned.

“I think you’re right,” agreed the professor, as he turned and looked at a bank of ugly dark clouds in the southwest. “A thunder shower is coming up, if I’m any judge. There doesn’t seem to be any shelter, either.”

As far as they could see there was nothing but a vast stretch of wild country, though, far to the north, there was a dark patch which looked as if it was a forest.

“It’s coming just at the wrong time,” remarked Jerry, who was steering. “I was in hopes the storm would hold off a bit. Well, we shan’t melt if it does rain.”

And that it was soon going to pour in the proverbial buckets full was evident. The wind began to blow a half gale, and the clouds, from which angry streaks of jagged lightning leaped, scurried forward. At the same time low mutterings of thunder were heard.

“We’re in for it,” cried Bob.

The next instant the storm broke, and the whole landscape was blotted out in a veil of mist and rain which came down in sheets of water. Now and then the darkness would be illuminated by a vivid flash of fire from the sky artillery, and the thunder seemed to shake the earth.

Jerry could barely see where to steer, so fiercely did the rain beat down. Fortunately they had time to put on their raincoats before the deluge hit them.

The provisions and other things in the auto had, likewise, been covered up with canvas, so little damage would result from the downpour.

“Look out!” yelled Ned suddenly to Jerry. “There’s something ahead of us!”

Jerry partially shut off the power, and, as the[48] machine slowed down, he and the others peered forward to see what the object was.

“It’s some sort of an animal!” cried Bob, who had sharp eyes. “It’s running along on four legs, right in front of the car!”

“It’s a bear, that’s what it is!” shouted Ned. “A big black bear!”

“Let me get it for a specimen!” exclaimed the professor, in his enthusiasm, not considering the size of the animal, nor the difficulties in the way of capturing it. “Let me get out! It’s worth forty dollars if it’s worth a cent!”

At the sound of the excited voices, which the animal must have heard above the roar of the storm, the bear turned suddenly and faced the occupants of the car. So quickly was it done that Jerry had barely time to jam on the brakes in order to avoid a collision.

“Why didn’t you run him down, and we could have some bear steaks for supper?” asked Bob.

“Because I don’t think it’s just healthy to run into a three hundred and fifty pound bear with a big auto,” replied Jerry. “We might kill the bear, but we’d be sure to damage the car.”

The beast did not appear to be frightened at the sight of his natural enemies. Raising on its haunches the animal slowly ambled toward the[49] stalled machine, growling in a menacing manner.

“I believe he’s going to attack us!” exclaimed the professor. “Let me get out my rifle!”

But this was easier said than done. The weapons and ammunition were all under the canvas, and it would require several minutes to get at them.

In the meanwhile the bear, showing every indication of rage was trying to climb up on the engine hood, despite the throbbing of the engine, which was going, though the gears were not thrown in.

“Start the car and run over him!” exclaimed Bob.

“Back up and get out of his way!” was Ned’s advice to Jerry.

“I’ve got to do something,” muttered the steersman.

Matters were getting critical. The storm was increasing in violence, with the wind lashing the rain into the faces of the travelers. The growls of the angry beast mingled with the rumble and rattle of thunder, and the machine was shaking under the efforts Bruin made to climb over the hood and into the front seat.

“Hold on tight! I’m going to start!” yelled Jerry suddenly.

He threw in the intermediate gear and opened wide the gasolene throttle. The car sprang forward like a thing alive. But the bear had too good a hold with his long sharp claws sticking in the ventilator holes of the hood, to be shaken off.

“I should think he’d burn on the water radiator,” said Ned.

“His fur’s too thick I guess,” was Bob’s reply.

On went the auto, the boys and the professor clinging to it for dear life, while Bruin hung on, half crazed with fear and anger.

“How you going to get rid of him?” shouted Ned above the roar of the storm.

“I’ll show you,” replied Jerry grimly.

Some distance ahead the steersman had seen a sharp curve in the road. It was dimly discernible through the mist of water.

“Hold tight everybody!” shouted Jerry a second or two before the turn was reached.

Then, suddenly swinging around it, at as sharp an angle as he dared to make and not overturn the car, Jerry sent the auto skidding. The next instant, unable to stand the impetus of the turn, the bear lost its hold on the hood, and was flung, like a stone from a catapult, far off to the left, rolling over and over on the muddy ground.

“There, I guess it will be quite a while before[51] he tries to eat up another live automobile,” remarked Jerry as he slowed up a bit.

Off in the distance they heard a sort of reproachful whine, as if Bruin objected to such treatment. Then the rain came down harder than ever, and all sight of the bear was lost.

“Let’s get out of this!” exclaimed Ned, as he felt a small stream of water trickling down his back. “Can’t we strike for those woods we saw a while ago?”

“I’m headed for them,” spoke Jerry. “I just want to get my bearings. Guess we’d better light up, as it will soon be dusk.”

After some difficulty in getting matches to burn in the wind and rain, the big search lights and the oil lanterns were lighted, and then, with four shafts of light cutting the misty darkness ahead of them the travelers proceeded.

The roads seemed to be getting worse, but there was nothing to do except to keep on. Every now and then the machine would lurch into some hollow with force enough to almost break the springs.

“Hello!” cried Jerry suddenly. “Here are two roads. Which shall we take?”

“The right seems to go a little more directly north,” said the professor, peering forward. “Suppose we take that?”

“Especially as it seems to be the better road,” added Jerry.

He turned the machine into it, and, to the surprise of all they felt the thoroughfare become hard and firm as the auto tires rolled over it. It was almost as smooth as asphalt, and the travelers were congratulating themselves on having made a wise choice.

All at once the rain, which had been coming down in torrents, seemed to let up.

“I believe it’s clearing up,” said Bob.

“No, it’s because we’ve run into a dense forest, and the trees above keep the rain off,” spoke the professor.

The others looked about them and saw that this was so. On every side the glare of the lamps showed big trunks and leafy branches, while ahead more trees could be observed.

“Why it’s just like a tunnel in the woods,” said Bob. “See, the trees seem to meet in an arch overhead.”

“And what a fine road it is,” put in Ned.

“An altogether strange sort of road,” agreed Jerry. “Suppose we stop and look about before we go any further? I don’t like the looks of it.”

Accordingly the machine was brought to a halt, and the travelers alighted. They found it just[53] as Bob had said, almost exactly like an immense tunnel in the forest. Beneath their feet the road was of the finest Macadam construction.

“And to think of finding this in the midst of Texas,” observed Jerry.

“Some one built this road, and cut the trees to make this tunnel,” remarked the professor. “I wonder what sort of a place we have stumbled into.”

“At all events it doesn’t rain anything to speak of in here,” said Bob, “and it’s a good place to stay until the storm is over.”

Jerry, in the meanwhile had walked on ahead some distance. In a few minutes he came hurrying back. His manner showed that he had seen something.

“What is it?” asked the professor.

“Don’t make any noise, but follow me,” replied the lad.

In silence, and wondering what was about to happen, Bob, Ned and the scientist trailed after Jerry. He led them several hundred feet ahead of the automobile, and away from the glare of the lamps, the tunnel curving somewhat.

“See!” whispered Jerry, hoarsely.

“Well, I never!”

“That’s queer!”

There, about three hundred feet to the left of the main road and on a sort of side path, the travelers saw a small hut, brilliantly lighted up. Through an open window, a room could be seen, and several figures moving about in it.

“I wonder who they can be, to hide off in the woods this way,” whispered Bob.

The next instant there floated out from the hut a cry of anguish. It was the voice of a boy, seemingly in great pain or fear, and the travelers heard the words:

“Oh don’t! Please don’t! You are killing me! I don’t know! I can’t tell you, for I would if I could! Oh! Oh! Please don’t burn me again!”

“It’s a gang torturing some one!” almost shouted Ned. “Let’s go to the rescue!”

He would have sprung forward had not Jerry laid a detaining hand on his arm.

“Wait, Ned,” counseled Jerry. “Some one there evidently needs our help, but we must go with caution. First we must get our guns. We may need them!”

Once more the appealing cry burst out.

“Quick!” whispered Jerry. “Professor, you[56] and Bob go back for the rifles, and bring the bulls-eye lantern that has the dark slide to it. Ned and I will stay here and watch!”

Mr. Snodgrass and Bob lost no time. In less than five minutes they had rejoined Ned and Jerry.

“Has anything happened?” asked Bob.

“Nothing since,” whispered Jerry. “Now we will go forward. Every one have his gun ready. I will carry the lantern.”

Almost as silently as shadows the four figures stole forward, Jerry showing a cautious gleam now and then to guide them on their way. They found there was a fairly good path leading up to the hut.

They had covered half the distance when once more the cries of anguish burst out. This time they were followed by angry shouts, seemingly from several men, and voices in dispute could be heard.

“One of us had better creep forward and see what is going on inside the cabin,” whispered Jerry. “We must know what sort of enemies we have to meet.”

“I’ll go,” volunteered Bob.

“Better let me,” suggested the professor. “I have had some experience in stalking animals, and[57] I can probably advance more quietly than you can.”

They all saw the reasonableness of this and the scientist started off. Like a cat he made an advance until he was so close to the hut that he could peer into the uncurtained window. What he saw made him start back in terror.

In the room were half a dozen roughly dressed men, all armed, and with brutal faces. The room was filled with smoke from cigars and pipes, and cards were scattered over a rough table in the middle of the apartment.

But what attracted the attention of the professor and made his heart beat fast in anger, was the sight of a small, pale boy, bound with ropes up against a big stone fireplace, on the hearth of which logs were burning.

In front of the lad stood one of the largest and strongest of the tough gang, and in his hand he held a redhot poker, which, as the scientist watched, he brought close to the bare legs of the terror-stricken lad.

Then came again those heart-rending cries:

“Oh don’t! Please don’t! I would tell you where he is if I knew! Please don’t burn me again!”

The professor’s blood boiled.

“We’ll soon put a stop to this horrible work!” he exclaimed to himself as he glided back to where the boys were and quickly made them acquainted with what he had seen.

“Come on!” cried Jerry. “We must rescue that boy!”

As softly as they could, the travelers advanced toward the hut. They found the door and, while the others with rifles in readiness stood in a semi-circle about it, Jerry made ready to knock and demand admittance.

“If they don’t open the door we must burst it in,” said the boy. “The professor and I will look to that, while you and Ned, Bob, must stand ready to rush in right after us with your guns ready. But don’t shoot unless your life is in danger, and then fire not to kill, but to wound.”

There was a minute of hesitation, for they all realized that it was taking a desperate chance to tackle such a rough gang in the midst of woods, far from civilization. But the sound of the poor boy’s cries nerved them on as, once more, the pitiful appeal for mercy rang out.

Jerry sprang forward and gave several vigorous blows on the door with the butt of his gun. All at once silence took the place of the confusion inside the hut.

“Who’s there? What do you want?” asked a gruff voice.

“Open the door! We want that boy!” cried Jerry.

Confused murmurs from within told that the gang had been taken by surprise.

“I don’t know who you are, but whoever you are you had better move on, if you don’t want a bullet through you,” called the man who had first answered the knock. “This is none of your affair.”

“Open the door or we’ll burst it in!” cried Jerry, knowing the best way to be successful in the fight was to act quickly and take the men by surprise.

There was a laugh from within the hut. It was answered by a rending, crashing splintering sound as Jerry and the professor, using the stocks of their guns, began a vigorous attack on the portal. The door was strong enough, but the hinges were not, and, in less than half a minute the barrier had given way and, with a bound the travelers found themselves tumbling into the hut.

Instantly confusion reigned. The men shouted hoarsely, and several tried to reach their guns, which were stacked in one corner.

“Hands up!” commanded Jerry sharply, leveling[60] his gun at the man who seemed to be the leader.

“Why, they’re nothing but boys! Knock ’em out of the way!” cried one of the gang. At the same time another began creeping up behind Jerry, his intention being to grab the lad from the back and disarm him.

But Bob saw the movement, and, leveling his rifle at the fellow, told him to halt.

“I guess you’ve got the drop on us,” growled the man whom Jerry was covering with the gun. “What’s the game anyhow? Are you stage robbers?”

“We want you to stop torturing that boy,” cried Jerry.

“Why, that’s my kid, and I was only givin’ him a taste of the rod because he wouldn’t mind me; ‘spare the rod and spoil the child,’ is a good saying, you know.”

“Not from you!” snapped the professor. “Is this man your father?” the scientist asked the bound boy.

“Speak up now! Ain’t I your daddy?” put in the leader, scowling at the boy.

“Tell the truth! Don’t let him scare you!” said the professor reassuredly. “We are in charge here now. Is he your father?”

“No—no—sir,” stammered the poor little lad, and then he burst into tears.

“I thought so!” commented the scientist. “Now you scoundrels clear out of here before we cause your arrest!”

“You’re talkin’ mighty high,” sneered the leader, “but look out! This matter is none of your affair, and that boy belongs to us!”

“Take me away! Oh, please take me away! They’ll kill me!” sobbed the lad.

There was such a fiery look in the professor’s eye as he leveled his gun at the gang of men that they started back, evidently fearing to be fired upon.

“Come on!” called one. “We’ll get some of the Mexicans and then we’ll see who’s runnin’ things around here!”

With that the gang sneaked out of the door, leaving the boys and the professor master of the situation. Their first act was to unbind the lad, who was almost fainting from pain and fear.

“Are there any more of them?” asked Jerry.

“Yes,” said the boy faintly. “There are a lot of half-breed Mexicans in the gang. They are in a hut about a mile farther up the road, where they keep a lot of horses on a ranch.”

“Then perhaps we’d better get out of here[62] while we have a chance,” said the professor. “We can’t fight a score or more. Let’s take the boy and hurry away.”

“Come on then,” said Jerry. “We’ll get back to the auto. I only hope these men don’t discover it and damage the car.”

But when an attempt to start was made it was found that the boy, who said, in response to an inquiry from Ned, that his name was Tommy Bell, was unable to walk. The ropes bound about his legs had caused the blood to stagnate in the veins.

“Here!” exclaimed Jerry. “Bob, you and Ned go ahead with the lantern, and the professor and I will carry Tommy. Step lively now!”

Moving in that order the procession started, and in a few minutes the travelers were back at the machine, which did not seem to have been disturbed. There was no sight or sound of the gang.

Tommy was made as comfortable as possible, and then there was a brief consultation.

“Which way had we better go?” asked Jerry.

“I think it would be best to turn around,” said Bob. “We’ll run up against the gang if we go ahead.”

“The best road is straight ahead through this[63] woods,” spoke Tommy. “If you take the other your machine will get stuck.”

“Then we’ll take this one, and trust to luck not to have any trouble with the gang,” decided Jerry, as he cranked up the car.

Just as they started the moon came out from the clouds, for the rain had ceased, and, though not many of the silver beams shone through the thick foliage, it was much lighter than it had been. Jerry threw in the gear and the next instant the car glided forward and shot along the tunnel of trees, leaving the hut where Tommy Bell had been a prisoner.

“Is the Mexican camp near this main road?” asked the professor of Tommy.

“About three hundred feet in,” answered the boy, who was feeling much better.

“How many men are at it?”

“About one hundred, I guess, from what I heard them say.”

“Then I guess we’d better go past it on the fly,” muttered Jerry, as he speeded up the machine until it was skimming along at a fast rate. In a little while there was a gleam of light through the trees ahead.

“There’s the camp!” exclaimed Tommy.

A minute later the travelers were made well[64] aware of it, for, as they whizzed past in the auto, they heard shouts of anger, mingling with the sounds of rushing feet, while an occasional pistol shot rang out, the flash of fire cutting the darkness.

“They saw us,” spoke Bob. “Lucky it was pretty dark, or they might have damaged the auto.”

“To say nothing of ourselves,” added Ned.

As the auto sped along, Professor Snodgrass asked Tommy Bell how he had come to the hut in the forest.

“Those men took me there,” replied the boy.

“And what did they try to make you do?” asked Jerry.

“They wanted me to tell them where my father was,” went on Tommy. “I could not because I did not know, and they burned me, because they did not believe I was telling the truth.”

“What did they want of your father?” inquired Mr. Snodgrass.

“They want him to sign some papers connected with some property,” went on Tommy. “I don’t know much about it, except that father used to work with those men developing a mine. It didn’t pay, and they left it, after selling it to some other men. I lived with my father, and my mother was alive then.”

The boy stopped, and, at the mention of his mother’s name began to cry softly.

“Poor little lad,” muttered the professor, putting his arm, with a sort of caressing motion about Tommy. “Don’t cry, lad,” the scientist went on, in what seemed a sort of husky voice, for he was very fond of children; “don’t worry, we’ll look out for you; won’t we, boys?”

“You bet!” exclaimed Jerry, Ned and Bob in one voice.

The auto was slowed down now, as there seemed to be no danger of pursuit.

“After mother died,” Tommy resumed, “and the mine did not pay, father started prospecting with Nat Richards and the others in that crowd. But they were bad men, and soon got the better of my dad, taking away what little money he had left.

“This ruined my father, and he grew discouraged, for he was old, and in poor health. He wandered away and I haven’t seen him for nearly a year. I traveled about, doing what little work I could get to do, until I struck Texas. One day, about a week ago, I passed a ranch, the same one we just came by. I asked for work, and got it. Then I found the same men owned it that had ruined my father.

“As soon as Nat Richards saw me he demanded to know where dad was. I couldn’t tell, and then he promised me one hundred dollars if I would tell. He said they needed my father’s signature to a paper.

“I don’t know as I would have told them where dad was if I did know. When I kept on refusing to give them the information, Nat Richards grew ugly. He had me taken off to the hut where you found me, and said he’d starve me to death if I didn’t tell.

“I almost did die from hunger,” Tommy went on with a catch in his voice. “Then they tried torture. They burned me on the legs with a hot poker. That’s what they were doing when you came in,” and, overcome again by the thought of all he had suffered Tommy cried bitterly.

The boys and the professor did all they could to comfort the friendless lad, and, soon Tommy’s grief wore off.

“We’ll take you along with us,” said Jerry heartily, “and we’ll try to help you find your father. Where did you see him last?”

“He was in Arizona,” answered Tommy.

“That’s just where we’re headed for,” exclaimed Bob. “We’ll take you there all right.”

Jerry leaned forward to throw in the higher[68] speed gear when there was a sudden ripping, breaking sound, and the auto began to slow up.

“What’s the matter?” asked Ned.

“Stripped the gear, I’m afraid,” replied the steersman. “This is a nice pickle to be in.”

“Won’t it run on the low or intermediate gear?” asked Bob.

Jerry tried them, and found they were all right.

“I guess we’d better stop here for the night,” he said. “We may need the high gear any minute, and perhaps I can fix it in the morning. I have a spare wheel.”

“Then let’s camp and have supper,” said Bob eagerly. “I haven’t eaten in a week by the way I feel.”

“Same here! I agree with you for once, Chunky,” spoke Jerry. “It has been a long time since dinner, but with the excitement of the storm, the bear, and rescuing Tommy I didn’t notice it before.”

In a little while the camping outfit was taken from the automobile, and a fire started in the sheet-iron stove, with the charcoal that was carried to be used in emergencies, such as being unable to find dry wood after a rain.

Ned ground the coffee, while Bob went in search of water, using the lantern to aid him in[69] the somewhat dim forest, though the moon helped some. He found a spring close at hand, and soon a fragrant beverage was steaming under the trees. Then some bacon was placed in the frying pan, and the hard tack was taken from the tin and other things prepared.

“Fall to!” commanded Ned, who was acting as cook, and fall to they all did, with a will.

“Do you often camp out and eat in the woods like this?” asked Tommy. “I think it’s jolly fun,” and the lad, who was about twelve years old, laughed for the first time since his rescue. He, too, was eating with an appetite that showed he needed the food.

Jerry briefly related some of their travel adventures, at which Tommy opened his eyes to their widest extent.

“Cracky! But you have had stunning times!” he exclaimed.

The meal having been finished, they began to think of getting some sleep. Blankets were brought out, and rolling themselves up in them the boys and the professor were soon in the land of nod.

It was nearly dawn when Jerry was suddenly awakened by the far off baying of a dog. At first he could not imagine what the sound was, and[70] sat up to listen more intently. Then a long, mournful howl was borne to him on the wind.

“That’s strange,” he muttered. “There are very few dogs about here. I wonder what it is.”

At the same time Tommy Bell roused up, and he, too, heard the sound.

“It’s the gang after us!” he exclaimed. “They have a lot of hounds on the ranch! Hurry up! Let’s get out of this!”

“Hark!” exclaimed Jerry, raising his hand.

Then the boys heard, faint and far off, the sound of galloping horses.

“They’re coming!” cried Jerry.

His cry awakened the others, who sat up bewildered and heavy from sound sleep.

“Lively’s the word!” called Jerry. “They’re after us!”

No further explanation was needed, for all knew what Jerry meant. There was a hasty piling of blankets into the auto; the stove was packed up, and, while the travelers jumped into the car, Jerry went in front to crank it up. The cheerful chug-chug told that the machinery was in good working order, and then, the boy, leaping into the steersman’s seat, threw in the low gear for the start.

As he did so Ned glanced back and saw, coming[71] around the bend of the forest road a score of horsemen and a pack of dogs.

“Speed her up, Jerry!” called Bob.

“I will!” was the exclamation, as Jerry leaned forward to throw in the high gear. A mournful screeching of the engine was the only response.

“I forgot! The high gear is broken!” the steersman cried. “We can only use the intermediate, and that is not very fast!”

“It’s the best we can do, though!” said Bob. “We may get away from them!”

On the intermediate cogs the auto made good speed, and, for a while, distanced the gang, the members of which, with shouts of rage, put their horses to their best effort.

The sun began to peep up from beneath the eastern hills, throwing a rosy light over the earth. The woods began to thin out, and the sides of the “tunnel,” which had been dense, became more open, so that glimpses of the country could be seen now and then.

The chase was now on in earnest. For some time, however, the auto kept well in advance of the horsemen, for Jerry used all the power possible on the differential gear. If the high speed one had been in working order there would have been no question of the outcome, but, for once, luck was against the boys.