THE INQUISITION OF SPAIN

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

A HISTORY OF THE INQUISITION OF THE MIDDLE AGES. In three volumes, octavo.

A HISTORY OF AURICULAR CONFESSION AND INDULGENCES IN THE LATIN CHURCH. In three volumes, octavo.

AN HISTORICAL SKETCH OF SACERDOTAL CELIBACY IN THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH. Third edition. (In preparation.)

A FORMULARY OF THE PAPAL PENITENTIARY IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY. One volume, octavo. (Out of print.)

SUPERSTITION AND FORCE. Essays on The Wager of Law, The Wager of Battle, The Ordeal, Torture. Fourth edition, revised. In one volume, 12mo.

STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY. The Rise of the Temporal Power, Benefit of Clergy, Excommunication, The Early Church and Slavery. Second edition. In one volume, 12mo.

CHAPTERS FROM THE RELIGIOUS HISTORY OF SPAIN, CONNECTED WITH THE INQUISITION. Censorship of the Press, Mystics and Illuminati, Endemoniadas, El Santo Niño de la Guardia, Brianda de Bardaxí.

THE MORISCOS OF SPAIN. THEIR CONVERSION AND EXPULSION. In one volume, 12mo.

BY

HENRY CHARLES LEA. LL.D.

———

IN FOUR VOLUMES

———

VOLUME I.

———

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1922

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Copyright, 1906,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

——

Set up and electrotyped. Published January, 1906.

IN the following pages I have sought to trace, from the original sources as far as possible, the character and career of an institution which exercised no small influence on the fate of Spain and even, one may say, indirectly on the civilized world. The material for this is preserved so superabundantly in the immense Spanish archives that no one writer can pretend to exhaust the subject. There can be no finality in a history resting on so vast a mass of inedited documents and I do not flatter myself that I have accomplished such a result, but I am not without hope that what I have drawn from them and from the labors of previous scholars has enabled me to present a fairly accurate survey of one of the most remarkable organizations recorded in human annals.

In this a somewhat minute analysis has seemed to be indispensable of its structure and methods of procedure, of its relations with the other bodies of the State and of its dealings with the various classes subject to its extensive jurisdiction. This has involved the accumulation of much detail in order to present the daily operation of a tribunal of which the real importance is to be sought, not so much in the awful solemnities of the auto de fe, or in the cases of a few celebrated victims, as in the silent influence exercised by its incessant and secret labors among the mass of the people and in the limitations which it placed on the Spanish intellect—in the resolute conservatism with which it held the nation in the medieval groove and unfitted it for the exercise of rational liberty when the nineteenth century brought in the inevitable Revolution.

The intimate relations between Spain and Portugal, especially during the union of the kingdoms from 1580 to 1640, has rendered necessary the inclusion, in the chapter devoted to the Jews, of a brief sketch of the Portuguese Inquisition, which earned a reputation even more sinister than its Spanish prototype.

I cannot conclude without expressing my thanks to the gentlemen whose aid has enabled me to collect the documents on which the work is largely based—Don Claudio Pérez Gredilla of the Archives of Simancas, Don Ramon Santa María of those of Alcalá de Henares prior to their removal to Madrid, Don Francisco de Bofarull y Sans of those of the Crown of Aragon, Don J. Figueroa Hernández, formerly American Vice-consul at Madrid, and to many others to whom I am indebted in a minor degree. I have also to tender my acknowledgements to the authorities of the Bodleian Library and of the Royal Libraries of Copenhagen, Munich, Berlin and the University of Halle, for favors warmly appreciated.

Henry Charles Lea.

Philadelphia, October, 1905.

| BOOK I—ORIGIN AND ESTABLISHMENT. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chapter I—The Castilian Monarchy. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Disorder at the Accession of Ferdinand and Isabella | 1 | |

| Condition of the Church | 8 | |

| Limitation of Clerical Privilege and Papal Claims | 11 | |

| Disputed Succession | 18 | |

| Character of Ferdinand and Isabella | 20 | |

| Enforcement of Royal Jurisdiction | 24 | |

| The Santa Hermandad | 28 | |

| Absorption of the Military Orders | 34 | |

| Chapter II—The Jews and the Moors. | ||

| Oppression of Jews taught as a duty | 35 | |

| Growth of the Spirit of Persecution | 37 | |

| Persecution under the Spanish Catholic Wisigoths | 40 | |

| Toleration under the Saracen Conquest—the Mozárabes | 44 | |

| The Muladícs | 49 | |

| The Jews under the Saracens | 50 | |

| Absence of Race or Religious Hatred | 52 | |

| The Mudéjares—Moors under Christian Domination | 57 | |

| The Church stimulates Intolerance | 68 | |

| Influence of the Council of Vienne in 1312 | 71 | |

| Commencement of repressive Legislation | 77 | |

| Chapter III—The Jews and the Conversos. | ||

| Medieval Persecution of Jews | 81 | |

| Their Wealth and Influence in Spain | 84 | |

| Clerical Hostility aroused | 90 | |

| Popular Antagonism excited | 95 | |

| Causes of Dislike—Usury, Official Functions, Ostentation | 96 | |

| Massacres in Navarre | 100 | |

| Influence of the Accession of Henry of Trastamara | 101 | |

| The Massacres of 1391—Ferran Martínez | 103 | |

| Creation of the Class of Conversos or New Christians | 111 | |

| Deplorable Condition of the Jews | 115 | |

| The Ordenamiento de Doña Catalina | 116 | |

| Utterances of the Popes and the Council of Basle | 118 | |

| Success of the Conversos—The Jews rehabilitate themselves | 120 | |

| Renewed Repression under Ferdinand and Isabella | 123 | |

| The Conversos become the object of popular hatred | 125 | |

| Expulsion of the Jews considered | 131 | |

| Expulsion resolved on in 1492—its Conditions | 135 | |

| Sufferings of the Exiles | 139 | |

| Number of Exiles | 142 | |

| Contemporary Opinion | 143 | |

| Chapter IV—Establishment of the Inquisition. | ||

| Doubtful Christianity of the Conversos | 145 | |

| Inquisition attempted in 1451 | 147 | |

| Alonso de Espina and his Fortalicium Fidei | 148 | |

| Episcopal Inquisition attempted in 1465 | 153 | |

| Sixtus IV grants Inquisitorial Powers to his Legate | 154 | |

| Attempt to convert and instruct | 155 | |

| Ferdinand and Isabella apply to Sixtus IV for Inquisition in 1478 | 157 | |

| They Require the Power of Appointment and the Confiscations | 158 | |

| The first Inquisitors appointed, September 17, 1480 | 160 | |

| Tribunal opened in Seville—first Auto de Fe, February 6, 1481 | 161 | |

| Plot to resist betrayed | 162 | |

| Edict of Grace | 165 | |

| Other tribunals established | 166 | |

| Failure of plot in Toledo—number of Penitents | 168 | |

| Tribunal at Guadalupe | 171 | |

| Necessity of Organization—The Supreme Council—The Inquisitor-general | 172 | |

| Character of Torquemada—His quarrels with Inquisitors | 174 | |

| Four Assistant Inquisitors-general | 178 | |

| Separation of Aragon from Castile | 180 | |

| Autonomy of Inquisition—It frames its own Rules | 181 | |

| It commands the Forces of the State.—Flight of Suspects | 182 | |

| Emigration of New Christians forbidden | 184 | |

| Absence of Resistance to the Inquisition | 185 | |

| Ferdinand seeks to prevent Abuses | 187 | |

| The Career of Lucero at Córdova | 189 | |

| Complicity of Juan Roiz de Calcena | 193 | |

| Persecution of Archbishop Hernando de Talavera | 197 | |

| Córdova appeals to Philip and Juana | 201 | |

| Revolt in Córdova | 202 | |

| Inquisitor-general Deza forced to resign | 205 | |

| Lucero placed on trial | 206 | |

| Inquisitorial Abuses at Jaen, Arjona and Llerena | 211 | |

| Ximenes attempts Reform | 215 | |

| Appeals to Charles V—His futile Project of Reform | 216 | |

| Conquest of Navarre—Introduction of Inquisition | 223 | |

| Chapter V—The Kingdoms of Aragon. | ||

| Independent Institutions of Aragon | 229 | |

| Ferdinand seeks to remodel the Old Inquisition | 230 | |

| Sixtus IV interferes | 233 | |

| Torquemada’s Authority is extended over Aragon | 236 | |

| Assented to by the Córtes of Tarazona in 1484 | 238 | |

| Valencia | ||

| Popular Resistance | 239 | |

| Resistance overcome | 242 | |

| Aragon | ||

| Tribunal organized in Saragossa | 244 | |

| Opposition | 245 | |

| Resistance in Teruel | 247 | |

| Murder of Inquisitor Arbués | 249 | |

| Papal Brief commanding Extradition | 253 | |

| Punishment of the Assassins | 256 | |

| Ravages of the Inquisition | 259 | |

| Catalonia | ||

| Its Jealousy of its Liberties | 260 | |

| Resistance prolonged until 1487 | 261 | |

| Scanty Results | 263 | |

| Oppression and Complaints | 264 | |

| The Balearic Isles | ||

| Inertia of the Old Inquisition | 266 | |

| Introduction of the New in 1488—Its Activity | 267 | |

| Tumult in 1518 | 268 | |

| Complaints of Córtes of Monzon, in 1510 | 269 | |

| Concordia of 1512 | 270 | |

| Leo X releases Ferdinand from his Oath | 272 | |

| Inquisitor-general Mercader’s Instructions | 273 | |

| Leo X confirms the Concordia of 1512 | 274 | |

| Charles V swears to observe the Concordia | 275 | |

| Dispute over fresh Demands of Aragon | 276 | |

| Decided in favor of Aragon | 282 | |

| Catalonia secures Concessions | 283 | |

| Futility of all Agreements—Fruitless Complaints of Grievances | 284 | |

| BOOK II—RELATIONS WITH THE STATE. | ||

| Chapter I—Relations with the Crown. | ||

| Combination of Spiritual and Temporal Jurisdiction | 289 | |

| Ferdinand’s Control of the Inquisition | 289 | |

| Except in Spiritual Affairs | 294 | |

| Gradual Development of Independence | 298 | |

| Philip IV reasserts Control over Appointments | 300 | |

| It returns to the Inquisitor-general under Carlos II | 301 | |

| The Crown retains Power of appointing the Inquisitor-general | 302 | |

| It cannot dismiss him but can enforce his Resignation—Cases | 304 | |

| Struggle of Philip V with Giudice—Case of Melchor de Macanaz | 314 | |

| Cases under Carlos III and Carlos IV | 320 | |

| Relations of the Crown with the Suprema | 322 | |

| The Suprema interposes between the Crown and the Tribunals | 325 | |

| It acquires control over the Finances | 328 | |

| Its Policy of Concealment | 331 | |

| Philip IV calls on it for Assistance | 333 | |

| Philip V reasserts Control | 336 | |

| Pecuniary Penances | 337 | |

| Assertion of Independence | 340 | |

| Temporal Jurisdiction over Officials | 343 | |

| Growth of Bureaucracy limits Royal Autocracy | 346 | |

| Reassertion of Royal Power under the House of Bourbon | 348 | |

| Chapter II—Supereminence. | ||

| Universal Subordination to the Inquisition | 351 | |

| Its weapons of Excommunication and Inhibition | 355 | |

| Power of Arrest and Imprisonment | 357 | |

| Assumption of Superiority | 357 | |

| Struggle of the Bishops | 358 | |

| Questions of Precedence | 362 | |

| Superiority to local Law | 365 | |

| Capricious Tyranny | 366 | |

| Inviolability of Officials and Servants | 367 | |

| Enforcement of Respect | 371 | |

| Chapter III—Privileges and Exemptions. | ||

| Exemption from taxation | 375 | |

| Exemption from Custom-house Dues | 384 | |

| Attempts of Valencia Tribunal to import Wheat from Aragon | 385 | |

| Privilege of Valencia Tribunal in the Public Granary | 388 | |

| Speculative Exploitation of Privileges by Saragossa Tribunal | 389 | |

| Coercive Methods of obtaining Supplies | 392 | |

| Valencia asserts Privilege of obtaining Salt | 394 | |

| Exemption from Billets of Troops | 395 | |

| The Right to bear Arms | 401 | |

| Exemption from Military Service | 412 | |

| The Right to hold Secular Office | 415 | |

| The Right to refuse Office | 420 | |

| The Right of Asylum | 421 | |

| Chapter IV—Conflicting Jurisdictions. | ||

| Benefit of Clergy | 427 | |

| Ferdinand grants to the Inquisition exclusive Jurisdiction over its Officials | 429 | |

| He confines it to Salaried Officials in criminal Actions and as Defendants in civil Suits | 430 | |

| Abusive Extension of Jurisdiction by Inquisitors | 431 | |

| Limitations in the Concordia of 1512 | 432 | |

| Servants of Officials included in the fuero | 432 | |

| Struggle in Castile over the Question of Familiars | 434 | |

| Settled by the Concordia of 1553 | 436 | |

| The Concordia extended to Navarre | 438 | |

| Struggle in Valencia—Concordia of 1554 | 439 | |

| Concordia disregarded—Córtes of 1564 | 441 | |

| Valencia Concordia of 1568 | 442 | |

| Disregard of its Provisions | 445 | |

| Complaints of criminal Familiars unpunished | 446 | |

| Aragon—its Court of the Justicia | 450 | |

| Grievances arising from the Temporal Jurisdiction | 452 | |

| The Concordia of 1568 | 454 | |

| Complaints of its Infraction—Córtes of 1626 | 454 | |

| Case of the City of Huesca | 456 | |

| Córtes of 1646—Aragon assimilated to Castile | 458 | |

| Diminished Power of the Inquisition in Aragon | 461 | |

| Catalonia—Non-observance of Concordias of 1512 and 1520 | 465 | |

| Disorders of the Barcelona Tribunal—Fruitless Complaints | 467 | |

| Catalonia—Hatred of the Tribunal—Catalonia rejects the Concordia of 1568 | 469 | |

| Córtes of 1599—Duplicity of Philip III | 471 | |

| Increasing Discord—Fruitless Efforts of Córtes of 1626 and 1632—Concordia of Zapata | 472 | |

| Rebellion of 1640—Expulsion of Inquisitors—A National Inquisition established | 476 | |

| Inquisition restored in 1652—Renewal of Discord | 479 | |

| War of Succession—Catalan Liberties abolished | 483 | |

| Majorca—Conflicts with the Civil Authorities | 484 | |

| Contests in Castile—Subservience of the Royal Power | 485 | |

| Exemption of Familiars from summons as Witnesses | 491 | |

| Conflicts with the Spiritual Courts | 493 | |

| Cases in Majorca—Intervention of the Holy See | 498 | |

| Conflicts with the Military Courts | 504 | |

| Conflicts with the Military Orders—Project of the Order of Santa María de la Espada Blanca | 505 | |

| Profits of the Temporal Jurisdiction of the Inquisition | 508 | |

| Abuses and evils of the System | 509 | |

| Fruitless Efforts to reform it in 1677 and 1696 | 511 | |

| Repression under the House of Bourbon | 514 | |

| Competencias for Settlement of Disputes | 517 | |

| The Temporal Jurisdiction under the Restoration | 520 | |

| Refusal of Competencias by the Inquisition | 521 | |

| Projects of Relief | 524 | |

| Chapter V—Popular Hostility. | ||

| Causes of Popular Hatred | 527 | |

| Visitations of the Barcelona Tribunal | 528 | |

| Troubles in Logroño | 530 | |

| Preferences claimed in Markets | 533 | |

| Trading by Officials | 534 | |

| Character of Officials | 536 | |

| Grievances of Feudal Nobles | 537 | |

| General Detestation a recognized Fact | 538 | |

| Appendix. | List of Tribunals | 541 |

| List of Inquisitors-general | 556 | |

| Spanish Coinage | 560 | |

| Documents | 567 | |

IT were difficult to exaggerate the disorder pervading the Castilian kingdoms, when the Spanish monarchy found its origin in the union of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon. Many causes had contributed to prolong and intensify the evils of the feudal system and to neutralize such advantages as it possessed. The struggles of the reconquest from the Saracen, continued at intervals through seven hundred years and varied by constant civil broils, had bred a race of fierce and turbulent nobles as eager to attack a neighbor or their sovereign as the Moor. The contemptuous manner in which the Cid is represented, in the earliest ballads, as treating his king, shows what was, in the twelfth century, the feeling of the chivalry of Castile toward its overlord, and a chronicler of the period seems rather to glory in the fact that it was always in rebellion against the royal power.[1] So fragile was the feudal bond that a ricohome or noble could at any moment renounce allegiance by a simple message sent to the king through a hidalgo.[2] The necessity of attracting population and organizing conquered frontiers, which subsequently became inland, led to granting improvidently liberal franchises to settlers, which weakened the powers of the crown,[3] without building up, as in France, a powerful Third Estate to serve as a counterpoise to the nobles and eventually to undermine feudalism. In Spain the business of the Castilian was war. The arts of peace were left with disdain to the Jews and the conquered Moslems, known as Mudéjares, who were allowed to remain on Christian soil and to form a distinct element in the population. No flourishing centres of industrious and independent burghers arose out of whom the kings could mould a body that should lend them efficient support in their struggles with their powerful vassals. The attempt, indeed, was made; the Córtes, whose co-operation was required in the enactment of laws, consisted of representatives from seventeen cities,[4] who while serving enjoyed personal inviolability, but so little did the cities prize this privilege that, under Henry IV, they complained of the expense of sending deputies. The crown, eager to find some new sources of influence, agreed to pay them and thus obtained an excuse for controlling their election, and although this came too late for Henry to benefit by it, it paved the way for the assumption of absolute domination by Ferdinand and Isabella, after which the revolt of the Comunidades proved fruitless. Meanwhile their influence diminished, their meetings were scantily attended and they became little more than an instrument which, in the interminable strife that cursed the land, was used alternately by any faction as opportunity offered.[5]

The crown itself had contributed greatly to its own abasement. When, in the thirteenth century, a ruler such as San Fernando III. made the laws respected and vigorously extended the boundaries of Christianity, Castile gave promise of development in power and culture which miserably failed in the performance. In 1282 the rebellion of Sancho el Bravo against his father Alfonso was the commencement of decadence. To purchase the allegiance of the nobles he granted them all that they asked, and to avert the discontent consequent on taxation he supplied his treasury by alienating the crown lands.[6] Notwithstanding the abilities of the regent, María de Molina, the successive minorities of her son and grandson, Fernando IV and Alfonso XI, stimulated the downward progress, although the vigor of the latter in his maturity restored in some degree the lustre of the crown and his stern justice re-established order, so that, as we are told, property could be left unguarded in the streets at night.[7] His son, Don Pedro, earned the epithet of the Cruel by his ruthless endeavor to reduce to obedience his turbulent nobles, whose disaffection invited the usurpation of his bastard brother, Henry of Trastamara. The throne which the latter won by fratricide and the aid of the foreigner, he could only hold by fresh concessions to his magnates which fatally reduced the royal power.[8] This heritage he left to his son, Juan I, who forcibly described, in the Córtes of Valladolid in 1385, how he wore mourning in his heart because of his powerlessness to administer justice and to govern as he ought, in consequence of the evil customs which he was unable to correct.[9] This depicts the condition of the monarchy during the century intervening between the murder of Pedro and the accession of Isabella—a dreary period of endless revolt and civil strife, during which the central authority was steadily growing less able to curb the lawless elements tending to eventual anarchy. The king was little more than a puppet of which rival factions sought to gain possession in order to cover their ambitions with a cloak of legality, and those which failed to secure his person treated his authority with contempt, or set up some rival in a son or brother as an excuse for rebellion. The work of the Reconquest which, for six hundred years, had been the leading object of national pride was virtually abandoned, save in some spasmodic enterprise, such as the capture of Antequera, and the little kingdom of Granada, apparently on the point of extinction under Alfonso XI, seemed destined to perpetuate for ever on Spanish soil the hateful presence of the crescent.

The long reign of the feeble Juan II, from 1406 to 1454, was followed by that of the feebler Henry IV, popularly known as El Impotente. In the Seguro de Tordesillas, in 1439, the disaffected nobles virtually dictated terms to Juan II.[10] In the Deposition of Ávila, in 1465, they treated Henry IV with the bitterest contempt. His effigy, clad in mourning and adorned with the royal insignia, was placed upon a throne and four articles of accusation were read. For the first he was pronounced unworthy of the kingly station, when Alonso Carrillo, Archbishop of Toledo, removed the crown; for the second he was deprived of the administration of justice, when Álvaro de Zuñiga, Count of Plasencia, took away the sword; for the third he was deprived of the government, when Rodrigo Pimentel, Count of Benavente, struck the sceptre away; for the fourth he was sentenced to lose the throne, when Diego López de Zuñiga tumbled the image from its seat with an indecent gibe. It was scarce more than a continuation of the mockery when they elected as his successor his brother Alfonso, a child eleven years of age.[11]

The lawless independence of the nobles and the effacement of the royal authority may be estimated from a single example. At Plasencia two powerful lords, Garcí Alvárez de Toledo, Señor of Oropesa, and Hernan Rodríguez de Monroy, kept the country in an uproar with their armed dissension. Juan II sent Ayala, Señor of Cebolla, with a royal commission to suppress the disorder. Monroy, in place of submitting, insulted Ayala, who as a “buen caballero” disdained to complain to the king and preferred to avenge himself. Juan on hearing of this summoned to his presence Monroy, who collected all his friends and retainers and set out with a formidable army. Ayala made a similar levy and set upon him as he passed near Cebolla. There was a desperate battle in which Ayala was worsted and forced to take refuge in Cebolla, while Monroy passed on to Toledo and, when he kissed the king’s hands, Juan told him that he had sent for him to cut off his head, but as Ayala had preferred to right himself he gave Monroy a God-speed on his journey home and washed his hands of the whole affair.[12]

The ricosomes who thus were released from all the restraint of law had as little respect for those of honor and morality. The virtues which we are wont to ascribe to chivalry were represented by such follies as the celebrated Passo Honroso of Suero de Quiñones, when that knight and his nine comrades, in 1434, kept, in honor of their ladies, for thirty days against all comers, the pass of the Bridge of Orbigo, at the season of the feast of Santiago and sixty-nine challengers presented themselves in the lists.[13] With exceptions such as this, and a rare manifestation of magnanimity, as when the Duke of Medina Sidonia raised an army and hastened to the relief of his enemy, Rodrigo Ponce de Leon besieged in Alhama,[14] the record of the time is one of the foulest treachery, from which truth and honor are absent and human nature displays itself in its basest aspect. According to contemporary belief, Ferdinand was indebted for the crown of Aragon to the poisoning of his brother, the deeply mourned Carlos, Prince of Viana, while the crown of Castile fell to Isabella through the similar taking off of her brother Alfonso.[15]

A characteristic incident is one involving Doña Maria de Monroy, who married into the great house of Henríquez of Seville, and was left a widow with two boys. When the youths were respectively eighteen and nineteen years old they were close friends of two gentlemen of Seville named Mançano. The younger brother, dicing with them in their house, was involved in a quarrel with them, when they set upon him with their servants and slew him. Then, fearing the vengeance of the elder brother, they sent him a friendly message to come and play with them; when he came they led him along a dark corridor in which they suddenly turned upon him and stabbed him to death. When the disfigured corpses of her boys were brought to Doña María she shed no tears, but the fierceness of her eyes frightened all who looked upon her. The Mançanos promptly took horse and fled to Portugal, whither Doña María followed them in male attire with a band of twenty cavaliers. Her spies were speedily on the track of the fugitives; within a month of the murders she came at night to the house where they lay concealed; the doors were broken in and she entered with ten of her men while the rest kept guard outside. The Mançanos put themselves in defence and shouted for help, but before the neighbors could assemble she had both their heads in her left hand and was galloping off with her troop, never stopping till she reached Salamanca, where she went to the church and laid the bloody heads on the tomb of her boys. Thenceforth she was known as Doña María la Brava, and her exploit led to long and murderous feuds between the Monroyes and the Mançanos.[16]

Doña María was but a type of the unsexed women, mugeres varoniles, common at the time, who would take the field or maintain their place in factious intrigue with as much ferocity and pertinacity as men. Ferdinand could well look without surprise on the activity in court and camp of his queen Isabella, when he remembered the prowess of his mother, Juana Henríquez, who had secured for him the crown of Aragon. Doña Leonora Pimentel, Duchess of Arévalo, was one of these; of the Countess of Medellin it was said that no Roman captain could get the better of her in feats of arms, and the Countess of Haro was equally noted. The Countess of Medellin, indeed, kept her own son in prison for years while she enjoyed the revenues of his town of Medellin and, when Queen Isabella refused to confirm her possession of the place, she transferred her allegiance to the King of Portugal to whom she delivered the castle of Merida. At the same time the Moorish influence, which was so strong in Castile, occasionally led to the opposite extreme. The Duke of Najera kept his daughters in such absolute seclusion that no man, not even his sons, was permitted to enter the apartments reserved for the women, and the reason he alleged—that the heart does not covet what the eye does not see—was little flattering to either sex.[17]

The condition of the common people can readily be imagined in this perpetual strife between warlike, ambitious and unprincipled nobles, now uniting in factions which involved the whole realm in war, and now contenting themselves with assaults upon their neighbors. The land was desolated; the husbandman scarce could take heart to plant his seed, for the harvest was apt to be garnered with the sword and thrust into castles to provision them against siege. As a writer of the period tells us, there was neither law nor justice save that of arms.[18] In a letter describing the universal anarchy, written by Hernando del Pulgar from Madrid, in 1473, he says that for more than five years there has been no communication from Murcia, where the family of Fajardo reigned supreme—it is, he says, as foreign a land as Navarre.[19] That the roads were unsafe for trade or travel was a matter of course; every petty hidalgo converted his stronghold into a den of robbers, and what these left was swept away by bands of Free Companions.[20] Disorder reigned supreme and all-pervading. The crown was powerless and the royal treasury exhausted. Improvident grants of lands and revenues and jurisdictions, to bribe the treacherous fidelity of faithless nobles, or to gratify worthless favorites, were made, till there was nothing left to give, and then Henry IV bestowed licenses for private mints, until there were a hundred and fifty of them at work, flooding the land with base money, to the unutterable confusion of the coinage and the impoverishment of the people.[21] The Córtes of Madrid, in 1467, and of Ocaña in 1469, called on Henry to resume his improvident grants, and those of Madrigal, in 1476, repeated the urgency to Ferdinand and Isabella, who had been forced to follow his example. To this the sovereigns replied thanking the Córtes and postponing the matter. They did not feel themselves strong enough until 1480, when at the Córtes of Toledo, they resumed thirty million maravedís of revenue which had been alienated during the troubles, and this after an investigation which left untouched the gifts to loyal subjects and only withdrew such as had been extorted.[22] Respect for the crown had fallen as low as its revenues. A story told of the Count of Benavente shows how difficult it was, even after the accession of Isabella, for the nobles to recognize that they owed any obedience to the sovereign. He was walking with the queen when a woman came weeping and begging justice, saying that he had had her husband slain in spite of a royal safe-conduct. She showed the letter which her husband had carried in his breast, pierced by the blow which had ended his life, when the count jeeringly remarked “A cuirass would have been of more service.” Piqued by this Isabella said “Count do you then not wish there was no king in Castile?” “Rather,” said he, “I wish there were many.” “And why?” “Because then I should be one of them.”[23]

In such a chaos of lawless passion it is not to be supposed that the Church was better than the nobles who filled its high places with worthless scions of their stocks, or than the lower classes of the laity who sought in it provision for a life of idleness and licence. The primate of Castile was the Archbishop of Toledo, who was likewise ex officio chancellor of the realm and whose revenues were variously estimated at from eighty to a hundred thousand ducats, with patronage at his disposal amounting to a hundred thousand more.[24] The occupant of this exalted position, at the accession of Isabella, was Alonso Carrillo, a turbulent prelate, delighting in war, foremost in all the civil broils of the period, who, not content with the immense income of his see, lavished extravagant sums in alchemy. Hernando del Pulgar, in a letter of remonstrance, said to him, “The people look to you as their bishop and find in you their enemy; they groan and complain that you use your authority not for their benefit and reformation but for their destruction; not as an exemplar of kindness and peace but for corruption, scandal, and disturbance.” When, in 1495, the puritan Ximenes was appointed to the archbishopric, one of his first acts is said to have been the removal, from near the altar of the Franciscan church of Toledo, of a magnificent tomb which Carrillo had erected to his bastard, Troilo Carrillo.[25]

His successor in the see of Toledo has a special interest for us in view of his labors to purify the faith which culminated in establishing the Inquisition. Pero González de Mendoza was one of the notable men of the day, whose influence with Ferdinand and Isabella won for him the name of “the third king.” While yet a child he held the curacy of Hita; at twelve he had the archdeaconry of Guadalajara, one of the richest benefices in Spain, which he retained during the successive bishoprics of Calahorra and Sigüenza and the archbishopric of Seville; the see of Sigüenza he kept during the whole tenure successively of the archiepiscopates of Seville and Toledo, in addition to which he was a cardinal and titular Patriarch of Alexandria. With his kindred of the powerful house of Mendoza he adhered to Henry IV, until they effected the sale of the hapless Beltraneja, who was in their hands, to her father, Henry, for certain estates and the title of Duke del Infantado for Diego Hurtado, the head of the family, after which Pero González and his kinsmen promptly transferred their allegiance to Isabella. His admiring biographer assures us that he was more ready with his hands than with his tongue, that he was a gallant knight and that there was never a war in Spain during his time in which he did not personally take part or at least have his troops engaged. Though he had no leisure to attend to his spiritual duties, he found time to yield to the temptations of the flesh. When, in 1484, he led the army of invasion into Granada he took with him his bastard, Rodrigo de Mendoza, a youth of twenty, who was already Señor del Castillo del Cid, and who, in 1492, was created Marquis of Cenete on the occasion of his marriage, amid great rejoicings, in the presence of Ferdinand and Isabella, to Leonor de la Cerda, daughter and heiress of the Duke of Medina Celi and niece of Ferdinand himself. This was not the only evidence of his frailty of which he took no shame, for he had another son named Juan, by a lady of Valladolid, who was married to Doña Ana de Aragon, another niece of Ferdinand.[26]

With such men at the head of the Church it is not to be expected that the lower orders of the clergy should be models of decency and morality, rendering Christianity attractive to Jew and Moslem. Alonso Carrillo, the archbishop of Toledo, can scarce be regarded as a strict disciplinarian, but even he felt obliged, when holding the council of Aranda in 1473, to endeavor to repress the more flagrant scandals of the clergy. As a corrective of their prevailing ignorance it was ordered that in future none should be ordained who could not speak Latin—the language of the ritual and the foundation of all instruction, theological and otherwise. They were forbidden to wear silk or gaily colored garments. As their licentiousness rendered them contemptible to the people, they were commanded to part with their concubines within two months. As their fondness for dicing led to perjuries, scandals and homicides, they were required thereafter to abstain from it, privately as well as publicly. As many priests disdained to celebrate mass, they were ordered to do so at least four times a year; bishops, moreover, were urged to celebrate at least thrice a year, under pain of severe penalties to be determined at the next council. The absurdities poured forth in their sermons by wandering priests and friars were to be repressed by requiring examinations prior to issuing licenses to preach, and the scandals of the pardon-sellers were to be diminished by subjecting them to the bishops. The bishops were also urged to make severe examples of offenders in the lower orders of the clergy, when delivered to them by the secular courts, and not to allow their enormities to enjoy continued immunity. The bishops, moreover, were commanded to make no charge for conferring ordinations; they were exhorted, and all other clerics were required, not to lead a dissolute military life or to enter the service of secular lords excepting of the king and princes of the blood. As duels were forbidden, both laity and clergy were warned that if slain in such encounters they would be refused Christian burial.[27] That this effort at reform was, as might be expected, wholly abortive is evidenced from the description of the vices of the ecclesiastical body when Ferdinand and Isabella subsequently endeavored to correct its more flagrant scandals.[28] It was wholly secularized and only to be distinguished from the laity by the sacred functions which rendered its vices more abhorrent, by the immunities which fostered and stimulated those vices and by the intolerance which, blind to all aberrations of morals, proclaimed the stake to be the only fitting punishment for aberration in the faith. While powerless to reform itself it yet had influence enough to educate the people up to its standard of orthodoxy in the ruthless persecution of all whom it pleased to designate as enemies of Christ.

Yet in Spain the immunities and privileges of the Church were less than elsewhere throughout Christendom. The independence which the secular power in Castile had always manifested toward the Holy See and its disregard of the canon law are points which will occasionally manifest themselves hereafter and are worthy of a moment’s consideration here. I have elsewhere shown that, alone among the Latin nations, Castile steadily refused to admit the medieval Inquisition and disregarded completely the prescriptions of the Church regarding heresy.[29] In the twelfth century the popular feeling toward the papacy is voiced in the ballads of the Cid. When a demand for tribute to the Emperor Henry IV is said to be made through the pope, Ruy Diaz advises King Fernando to send a defiance from both of them to the pope and all his party, which the monarch accordingly does. So when the Cid accompanies his master to a great council in Rome and kicks over the chair prepared for the King of France, the pope excommunicates him, whereupon he kneels before the holy father and asks for absolution, telling him it will be the worse for him if he does not grant it, which the pope promptly does on condition of his being more self-restrained during the remainder of his stay.[30] There is no trace of the veneration for the vice-gerent of God which elsewhere was inculcated as an indispensable religious duty.

When such was the popular temper it is easy to understand that the prohibition to carry money out of the kingdom to the pope was even more emphatic than in England.[31] The claim to control the patronage of the Church, which was so prolific a source of revenue to the curia, met throughout Spain a resistance as sturdy as in England, though the troubled condition of the land interfered with its success. In Catalonia, the Córtes, in 1419, adopted a law in which, after alluding to the scandals and irreparable injuries arising from the intrusion of strangers, it was declared that none but natives should hold preferment of any kind and that all papal letters and bulls contravening this should be resisted in whatever way was necessary.[32] In Castile the Córtes of 1390 forcibly represented to Juan I the evils resulting from this foisting of strangers on the Spanish Church, but his speedy death prevented action. The remonstrance was renewed to the tutors of the young Henry III, who promptly placed an embargo on the revenues of foreign benefice-holders and forbade the admission of subsequent appointees. This led to a compromise, in 1393, by which the Avignonese curia secured the recognition of existing incumbents by promising that no more such nominations should be made.[33] The promise made by the Avignonese antipope was not binding on the Roman curia and the quarrel continued. Even if the recipient was a native there was little ceremony in dealing with papal grants of benefices when occasion prompted, as was shown in the affair which first revealed the unbending character of the future Cardinal Ximenes. During his youthful sojourn in Rome Ximenes procured papal “expectative letters” granting him the first preferment that should fall vacant in the diocese of Toledo. On his return he made use of these letters to take possession of the arciprestazgo of Uceda, but it happened that Archbishop Carrillo simultaneously gave it to one of his creatures and, as Ximenes refused to surrender his rights, he was thrown into a tower in Uceda—a tower he subsequently, when himself Archbishop of Toledo, used as a treasury. As he continued obstinate, Carrillo transferred him to the Pozo de Santorcas, a harsh dungeon used for clerical malefactors, where he lay for six years, resolutely refusing to abandon his claim, until released at the intercession of the wife of a nephew of Carrillo.[34] Evidently the Castilian prelates had slender respect for papal diplomas. About the same time, during the civil war between Henry IV and his brother Alfonso, when Hernando de Luxan, Bishop of Sigüenza, died, the dean, Diego López, obtained possession of the castles and the treasure of the see, joined the party of Alfonso, and, with the aid of Archbishop Carrillo, caused himself to be elected bishop. Meanwhile Paul II gave the see to Juan de Maella, Cardinal-bishop of Zamora, but Diego López refused to obey the bulls and appealed to the future council against the pope and all his censures. He disregarded an interdict launched against him and was supported by all his clergy. Maella died and Paul II gave the bishopric to the Bishop of Calahorra, requesting Henry IV to place him in possession. So secure did Diego López feel that he rejected a compromise offering him the see of Zamora in exchange, but the possession of Sigüenza happened to be of importance in the war; by bribery a troop of royalist soldiers obtained admittance to the castle and carried off López as a prisoner.[35]

It was the same even with so pious a monarch as Ferdinand the Catholic. When, in 1476, the archiepiscopal see of Saragossa became vacant by the death of Juan of Aragon, Ferdinand, with his father, Juan II, asked Sixtus IV to appoint his natural son, Alfonso, a child six years of age. The claim of the papacy to archiepiscopal appointments, based on the necessity of the pallium, was of ancient date and had become incontestable. In the thirteenth century Alfonso X had admitted it in the case of the archbishops, but when Isabella appointed Ximenes to the see of Toledo in 1495 the proceedings showed that the post was considered to be in the gift of the crown and the papal confirmation to be a matter of course.[36] So in the present case the request was a mere form, as was seen when Sixtus refused. The defect of birth could be dispensed for, but the youth of Alfonso was an insuperable objection, and Sixtus appointed Ansias Dezpuch, then Archbishop of Monreal, thinking that the services rendered by him and by his uncle, the Master of the Order of Montesa, would induce the king to assent. Dezpuch accepted, but Ferdinand at once sequestrated all the revenues of Monreal and the priory of Santa Cristina and ordered him to resign. On his hesitating, Ferdinand threatened to seize all the castles and revenues of the mastership of Montesa, which was effectual, and Sixtus compromised by making the boy perpetual administrator of Saragossa.[37]

Isabella, despite her piety, was as firm as her husband in defending the claim of the crown in these matters against the papacy. When, in 1482, the see of Cuenca became vacant and Sixtus IV appointed a Genoese cousin to the position, Ferdinand and his queen energetically represented that only Spaniards should have Spanish bishoprics and that the selection should be made by them. Sixtus retorted that all benefices were in the gift of the pope and that his power, derived from God, was unlimited, whereupon they ordered home all their subjects resident in the papal court and threatened to take steps for the convocation of a general council. These energetic proceedings brought Sixtus to terms and he sent to Spain a special nuncio, but Ferdinand and Isabella stood on their dignity and refused even to receive him. Then the Cardinal of Spain, Pero González de Mendoza, intervened and, on Sixtus withdrawing his pretensions, they allowed themselves to be reconciled.[38] They alleged that whatever might be the papal rights in other countries, in Spain the patronage of all benefices belonged to the crown because they and their predecessors had wrested the land from the infidel.[39] So jealous, indeed, were they of the papal encroachments that among the subjects which they submitted to the national synod assembled by them in Seville, June, 1478, was how to prevent the residence of papal legates and nuncios, who not only carried off much money from the kingdom, but threatened the royal pre-eminence, to which the synod replied that this rested with the sovereigns to do as their predecessors had done.[40] It is easy thus to understand why, in the organization of the Inquisition, they insisted that all appointments should be made by the throne.

In other ways the much-prized superiority of the canon over secular law was disregarded in Spain. The Córtes and the monarch had never hesitated to legislate on ecclesiastical affairs, and the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts was limited with a jealousy which paid scant respect to canon and decretal. Nothing, for instance, was better settled than the spiritual cognizance of all matters respecting testaments, yet when, in 1270, the authorities of Badajoz complained of the interference of the bishop’s court with secular judges in such affairs, proceeding to the excommunication of those who exercised jurisdiction over them, Alfonso X expressed surprise and gave explicit commands that such cases should be decided by the lay courts exclusively.[41] So little respect was felt for the immunity of ecclesiastics from secular law, in defence of which Thomas à Becket had laid down his life, that, as late as 1351, an ordenamiento of Pedro the Cruel concedes to them that they shall not be cited before secular judges except in accordance with law.[42] On the other hand, laymen were jealously protected from the ecclesiastical courts. The crown was declared to be the sole judge of its own jurisdiction, and no appeal from it was allowed. In the exercise of this supreme power laws were repeatedly enacted providing that a layman, who should cite another layman before a spiritual judge, not only lost his cause but incurred a heavy fine and disability for public office. The spiritual judge could not imprison a layman or levy execution on his property, and he who attempted it or any other invasion of the royal jurisdiction forfeited his benefices and became a stranger in the kingdom, thus rendering him incapable of preferment. The ecclesiastic who cited a layman before a spiritual judge lost any privileges or graces which he might hold of the crown. The layman who attempted to remove a cause from a lay court to a spiritual one was punished with confiscation of all his property, while any vassal who claimed benefit of clergy and declined the jurisdiction of a royal court forfeited his fief. In re-enacting these laws in the Córtes of Toledo, in 1480, Ferdinand and Isabella complained of their inobservance and ordered their strict enforcement.[43] No other nation in Christendom dared thus to infringe on the sacred limits of spiritual jurisdiction.

Yet even this was not all, for the secular power asserted its right to intervene in matters within the Church itself. Elsewhere the ineradicable vice of priestly concubinage was left to be dealt with by bishops and archdeacons. The guilty priests themselves, even in Castile, were exempt from civil authority, but Ferdinand and Isabella had no hesitation in invading their domiciles and, by repeated edicts in 1480, 1491, 1502, and 1503, endeavored to cure the evil by fining, scourging, and banishing their partners in sin.[44] It is true, as we have seen above, that these laws were eluded, but there was at least a vigorous attempt to enforce them for, in 1490, the clergy of Guipuzcoa complained that the officers of justice visited their houses to see whether they kept concubines (which of course they denied) and carried off their women to prison, where they were forced to confess themselves concubines, to the great dishonor of the Church, whereupon the sovereigns repressed the excessive zeal of their officials and ordered them in future to interfere only when the concubinage was notorious.[45] A yet more significant extension of royal authority was exercised when, in 1490, the people of Lequeitio (Biscay) complained that, though there were twelve mass-priests in the parish church, they all celebrated together and at uncertain times, so that the pious were unable to be present. This was a matter belonging exclusively to the diocesan authority, yet the appeal was made to the crown, and the Royal Council felt no scruple in ordering the priests to celebrate in succession and at reasonable hours, under pain of banishment and forfeiture of temporalities, thus disregarding even the imprescriptible immunities of the priesthood.[46] So slender, indeed, was the respect paid to these immunities that the Council of Aranda, in 1473, complained that magistrates of cities and other temporal lords presumed to banish ecclesiastics holding benefices in cathedral churches, and it may well be doubted whether the interdict with which the council threatened to punish this infraction of the canons was effective in its suppression.[47]

One of the most deplorable abuses with which the Church afflicted society was the admission into the minor orders of crowds of laymen who, without abandoning worldly pursuits, adopted the tonsure in order to enjoy the irresponsibility afforded by the claim acquired to spiritual jurisdiction, whether as criminals or as traders. The Córtes of Tordesillas, in 1401, declared that the greater portion of the rufianes and malefactors of the kingdom wore the tonsure; when arrested by the secular officials the spiritual courts demanded them and enforced their claims with excommunication, after which they freely discharged the evil doers. This complaint was re-echoed by almost every subsequent Córtes, with an occasional allusion to the stimulus thus afforded to the evil propensities of those who were really clerics. The kings in responding to these representations could only say that they would apply to the Holy Father for relief, but the relief never came.[48] The spirit in which these claims of clerical immunity were advanced as a shield for criminals and the resolute firmness with which they were met by Ferdinand and Isabella are illustrated by an occurrence in 1486, in Truxillo, where a man committed a crime and was arrested by the corregidor. He claimed to wear the tonsure and, as the officials delayed in handing him over to the ecclesiastical court, some clerics who were his kinsmen paraded the streets with a cross and proclaimed that religion was being destroyed. They succeeded thus in arousing a tumult in which the culprit was liberated. The sovereigns were in Galicia, but they forthwith despatched troops to the scene of disturbance; severe punishment was inflicted on the participants in the riot, and the clerics who had provoked it were deprived of citizenship and were banished from Spain.[49] Less serious but still abundantly obnoxious were the advantages which these tonsured laymen possessed in civil suits by claiming the privilege of ecclesiastical jurisdiction. To meet this was largely the object of the laws in the Ordenanzas Reales described above, and these were supplemented, in 1519, by an edict of Charles V forbidding episcopal officials from cognizance of cases where such so-called clerics engaged in trade sought the spiritual courts as a defence against civil suits. A similar abuse, by which such clerics in public office evaded responsibility for wrong-doing by pleading their clergy, he remedied by reviving an old law of Juan I declaring them ineligible to office.[50] Thus the royal power in Spain asserted its authority over the Church after a fashion unknown elsewhere. We shall see that, so long as it declined to persecute Moors and Jews, Rome could not compel it to do so. When its policy changed under Isabella it was inevitable that the machinery of persecution should be under the control, not of the Church, but of the sovereign. We shall also see that, when the Inquisition inflicted similar wrongs by the immunities claimed for its own officials and familiars, the sovereigns customarily turned a deaf ear to the complaints of the people.

Such was the condition of Castile when the death of the miserable Henry IV, December 12, 1474, cast the responsibility of royalty on his sister Isabella and her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon. The power of the crown was eclipsed; the land was ravaged with interminable war between nobles who were practically independent; the sentiment of loyalty and patriotism seemed extinct: deceit and treachery, false oaths—whatever would serve cupidity and ambition—were universal; justice was bought and sold; private vengeance was exercised without restraint; there was no security for life and property. The fabric of society seemed about to fall in ruins.[51] To evolve order out of this chaos of passion and lawlessness was a task to test to the uttermost the nerve and capacity of the most resolute and sagacious. To add to the confusion there was a disputed succession, although, in 1468, the oath of fidelity had been taken to Isabella, with the assent of Henry IV, in the Contract of Perales, by which he, for the second time, acknowledged his reputed daughter Juana not to be his. He was popularly believed to be impotent, and when his wife Juana, sister of Affonso V of Portugal, bore him a daughter, whom he acknowledged and declared to be his heir, her paternity was maliciously ascribed to Beltran de la Cueva, and she was known by the opposite party as La Beltraneja. Though Henry had been forced by his nobles to set aside her claims in favor of his brother Alfonso in the Declaration of Cabezon, in 1464, and, after Alfonso’s death, in favor of Isabella, in 1468, the latter’s marriage, in 1469, with Ferdinand of Aragon so angered him that he betrothed Juana to Charles Duke of Guienne, brother of Louis XI of France, and made the nobles of his faction swear to acknowledge her. At his death he testified again to her legitimacy and declared her to be his successor in a will which long remained hidden and finally in 1504 fell under the control of Ferdinand, who ordered it burnt.[52] There was a powerful party pledged to support her rights, and they were aided on the one hand by Affonso of Portugal and on the other by Louis of France, each eager to profit by dismembering the unhappy land. Some years of war, more cruel and bloody than even the preceding aimless strife, were required to dispose of this formidable opposition—years which tried to the utmost the ability of the young sovereigns and proved to their subjects that at length they had rulers endowed with kingly qualities. The decisive victory of Toro, won by Ferdinand over the Portuguese, March 1, 1476, virtually settled the result, although the final treaty was not signed until 1479. The Beltraneja was given the alternative of marrying within six months Prince Juan, son of Ferdinand and Isabella, then but two years old, or of entering the Order of Santa Clara in a Portuguese house. She chose the latter, but she never ceased to sign herself Yo la Reina, and her pretensions were a frequent source of anxiety. She led a varied life, sometimes treated as queen, with a court around her, and sometimes as a nun in her convent, dying at last in 1531, at the age of seventy.[53]

Isabella was queen in fact as well as in name. Under the feudal system, the husband of an heiress was so completely lord of the fief that, in the Capitulations of Cervera, January 7, 1469, which preceded the marriage, the Castilians carefully guarded the autonomy of their kingdom and Ferdinand swore to observe the conditions.[54] Yet, on the death of Henry IV, he imagined that he could disregard the compact, alleging that the crown of Castile passed to the nearest male descendant, and that through his grandfather, Ferdinand of Antequera, brother of Henry III, he was the lawful heir. The position was, however, too doubtful and complicated for him to insist on this; a short struggle convinced his consummate prudence that it was wisdom to yield, and Isabella’s wifely tact facilitated submission. It was agreed that their two names should appear on all papers, both their heads on all coins, and that there should be a single seal with the arms of Castile and Aragon. Thereafter they acted in concert which was rarely disturbed. The strong individuality which characterized both conduced to harmony, for neither of them allowed courtiers to gain undue influence. As Pulgar says “The favorite of the king is the queen, the favorite of the queen is the king.”[55]

Ferdinand, without being a truly great man, was unquestionably the greatest monarch of an age not prolific in greatness, the only contemporary whom he did not wholly eclipse being Henry VII of England. Constant in adversity, not unduly elated in prosperity, there was a stedfast equipoise in his character which more than compensated for any lack of brilliancy. Far-seeing and cautious, he took no decisive step that was not well prepared in advance but, when the time came, he could strike, promptly and hard. Not naturally cruel, he took no pleasure in human suffering, but he was pitiless when his policy demanded. Dissimulation and deceit are too invariable an ingredient of statecraft for us to censure him severely for the craftiness in which he surpassed his rivals or for the mendacity in which he was an adept. Cold and reserved, he preferred to inspire fear rather than to excite affection, but he was well served and his insight into character gave him the most useful faculty of a ruler, the ability to choose his instruments and to get from them the best work which they were capable of performing, while gratitude for past services never imposed on him any inconvenient obligations. He was popularly accused of avarice, but the empty treasury left at his death showed that acquisitiveness with him had been merely a means to an end.[56] His religious convictions were sincere and moreover he recognized wisely the invaluable aid which religion could lend to statesmanship at a time when Latin Christianity was dominant without a rival. This was especially the case in the ten years’ war with Granada, his conduct of which would alone stamp him as a leader of men. The fool-hardy defiance of Abu-l-Hacan when, in 1478, he haughtily refused to resume payment of the tribute which for centuries had been imposed on Granada, and when, in 1481, he broke the existing truce by surprising Zahara, was a fortunate occurrence which Ferdinand improved to the utmost. The unruly Castilian nobles had been reduced to order, but they chafed under the unaccustomed restraint. By giving their warlike instincts legitimate employment in a holy cause, he was securing internal peace; by leading his armies personally, he was winning the respect of his Castilian subjects who hated him as an Aragonese, and he was training them to habits of obedience. By making conquests for the crown of Castile he became naturalized and was no longer a foreigner. It was more than a hundred years since a King of Castile had led his chivalry to victory over the infidel, and national pride and religious enthusiasm were enlisted in winning for him the personal authority necessary for a sovereign, which had been forfeited since the murder of Pedro the Cruel had established the bastard line upon the throne. It was by such means as this, and not by the Inquisition that he started the movement which converted feudal Spain into an absolute monarchy. His life’s work was seen in the success with which, against heavy odds, he lifted Spain from her obscurity in Europe to the foremost rank of Christian powers.

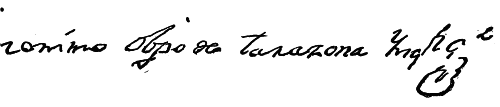

Yet amid the numerous acts of cruelty and duplicity which tarnish the memory of Ferdinand as a statesman, examination of his correspondence with his officials of the Inquisition, especially with those employed in the odious business of confiscating the property of the unhappy victims, has revealed to me an unexpectedly favorable aspect of his character. While urging them to diligence and thoroughness, his instructions are invariably to decide all cases with rectitude and justice and to give no one cause of complaint. While insisting on the subordination of the people and the secular officials to the Holy Office, more than once we find him intervening to check arbitrary action and to correct abuses and, when cases of peculiar hardship arising from confiscations are brought to his notice, he frequently grants to widows and orphans a portion of the forfeited property. All this will come before us more fully hereafter and a single instance will suffice here to illustrate his kindly disposition to his subjects. In a letter of October 20, 1502, he recites that Domingo Muñoz of Calatayna has appealed to him for relief, representing that his little property was burdened with an annual censal or ground-rent of two sols eight dineros—part of a larger one confiscated in the estate of Juan de Buendia, condemned for heresy—and he orders Juan Royz, his receiver of confiscations at Saragossa, to release the ground-rent and let Muñoz have his property unincumbered, giving as a reason that the latter is old and poor.[57] It shows Ferdinand’s reputation among his subjects that such an appeal should be ventured, and the very triviality of the matter renders it the more impressive that a monarch, whose ceaseless personal activity was devoted to the largest affairs of that tumultuous world, should turn from the complicated treachery of European politics to consider and grant so humble a prayer.

In his successful career as a monarch he was well seconded by his queen. Without deserving the exaggerated encomiums which have idealized her, Isabella was a woman exactly adapted to her environment. As we have seen, the muger varonil was a not uncommon development of the period in Spain, and Isabella’s youth, passed in the midst of civil broils, with her fate more than once suspended in the balance, had strengthened and hardened the masculine element in her character. Self-reliant and possessed of both moral and physical courage, she was prompt and decided, bearing with ease responsibilities that would have crushed a weaker nature and admirably fitted to cope with the fierce and turbulent nobles, who respected neither her station nor her sex and could be reduced to obedience only by a will superior to their own. She had the defects of her qualities. She could not have been the queen she was without sacrifice of womanly softness, and she earned the reputation of being hard and unforgiving.[58] She could not be merciful when her task was to reduce to order the wild turmoil and lawlessness which had so long reigned unchecked in Castile, but in this she shed no blood wantonly and she knew how to pardon when policy dictated mercy. How she won the affection of those in whom she confided can be readily understood from the feminine grace of her letters to her confessor, Hernando of Talavera.[59] A less praiseworthy attribute of her sex was her fondness for personal adornment, in which she indulged in spite of a chronically empty treasury and a people overwhelmed with taxation. We hear of her magnifying her self-abnegation in receiving the French ambassador twice in the same gown, while an attaché of the English envoy says that he never saw her twice in the same attire, and that a single toilet, with its jewels and appendages must have cost at least 200,000 crowns.[60] She was moreover rigidly tenacious of the royal dignity. Once when Ferdinand was playing cards with some grandees, the Admiral of Castile, whose sister was Ferdinand’s mother, addressed him repeatedly as “nephew”; Isabella was undressed in an inner room and heard it; she hastily gathered a garment around her, put her head through the door and rebuked him—“Hold! my lord the king has no kindred or friends, he has servants and vassals.”[61] She was deeply and sincerely religious, placing almost unbounded confidence in her spiritual directors, whom she selected, not among courtly casuists to soothe her conscience, but from among the most rigid and unbending churchmen within her reach, and to this may in part be attributed the fanaticism which led her to make such havoc among her people. She was scrupulously regular in all church observances; in addition to frequent prayers she daily recited the hours like a priest, and her biographer tells us that, in spite of the pressing cares of state, she seemed to lead a contemplative rather than an active life.[62] She was naturally just and upright, though, in the tortuous policy of the time, she had no hesitation in becoming the accomplice of Ferdinand’s frequent duplicity and treachery. With all the crowded activity of her eventful life, she found time to stimulate the culture despised by the warlike chivalry around her, and she took a deep interest in an academy which, at her instance, was opened for the young nobles of her court by the learned Italian, Peter Martyr of Anghiera.[63]

Isabella recognized that the surest way to curb the disorders which pervaded her kingdom was the vigorous enforcement of the law and, as soon as the favorable aspect of the war of the succession gave leisure for less pressing matters, she set earnestly to work to accomplish it. The victory of Toro was followed immediately by the Córtes of Madrigal, April 27, 1476, where far-reaching reforms were enacted, among which the administration of justice and the vindication of the royal prerogatives occupied a conspicuous place.[64] It was not long before she gave her people a practical illustration of her inflexible determination to enforce these reforms. In 1477 she visited Seville with her court and presided in public herself over the trial of malefactors. Complaints came in thick and fast of murders and robberies committed in the bad old times; the criminals were summarily dispatched, and a great fear fell upon the whole population, for there was scarce a family or even an individual who was not compromised. Multitudes fled and Seville bade fair to be depopulated when, at the supplication of a great crowd, headed by Enrique de Guzman, Duke of Medina Sidonia, she proclaimed an amnesty conditioned on the restitution of property, making, however, the significant exception of heresy.[65]

From Seville she went, accompanied by Ferdinand, to Córdova. There they executed malefactors, compelled restitution of property, took possession of the castles of robber hidalgos, and left the land pacified. As opportunity allowed, in the busy years which followed, Isabella visited other portions of her dominions, from Valencia to Biscay and Galicia, on the same errand and, when she could not appear in person, she sent judges around with full power to represent the crown, the influence of which was further extended when, in 1480, the royal officers known as corregidores were appointed in all towns and cities.[66] One notable case is recorded which impressed the whole nobility with salutary terror. In 1480 the widow of a scrivener appealed to her against Alvar Yáñez, a rich caballero of Lugo in Galicia, who, to obtain possession of a coveted property, caused the scrivener to forge a deed and then murdered him to insure secrecy. It was probably this which led Ferdinand and Isabella to send to Galicia Fernando de Acuña as governor with an armed force, and Garcí López de Chinchilla as corregidor. Yáñez was arrested and finally confessed and offered to purchase pardon with 40,000 ducats to be applied to the Moorish wars. Isabella’s counsellors advised acceptance of the tempting sum for so holy a cause, but her inflexible sense of justice rejected it; she had the offender put to death, but to prove her disinterestedness she waived her claim to his forfeited estates and gave them to his children. Alvar Yáñez was but a type of the lawless nobles of Galicia who, for a century, had been accustomed to slay and spoil without accountability to any one. So desperate appeared the condition of the land that when, in 1480, the deputies of the towns assembled to receive Acuña and Chinchilla they told them that they would have to have powers from the King of Heaven as well as from the earthly king to punish the evil doers of the land.[67] The example made of Yáñez brought encouragement, but the work of restoring order was slow. Even in 1482 the representatives of the towns of Galicia appealed to the sovereigns, stating that there had long been neither law nor justice there and begging that a justizia mayor be appointed, armed with full powers to reduce the land to order. They especially asked for the destruction of the numerous castles of those who, having little land and few vassals to support them, lived by robbery and pillage, and with them they classed the fortified churches held by prelates. At the same time they represented that homicide had been so universal that, if all murderers were punished, the greater part of the land would be ruined, and they suggested that culprits be merely made to serve at their own expense in the war with Granada.[68] With the support of the well-disposed, however, the royal power gradually made itself felt; they lent efficient support to the royal representatives; forty-six robber castles were razed and fifteen hundred robbers and murderers fled from the province, which became comparatively peaceful and orderly—a change confirmed when, in 1486, Ferdinand and Isabella went thither personally to complete the work. Yet it was not simply by spasmodic effort that the protection of the laws was secured for the population. Constant vigilance was exercised to see that the judges were strict and impartial. In 1485, 1488 and 1490 we hear of searching investigations made into the action of all the corregidores of the kingdom to see that they administered justice without fear or favor. Juezes de Residencia, as they were called, armed with almost full royal authority, were dispatched to all parts of the kingdom, as a regular system, to investigate and report on the conduct of all royal officials, from governors down, with power to punish for injustice, oppression, or corruption, subject always to appeal in larger cases to the royal council, and the detailed instructions given to them show the minute care exercised over all details of administration. Bribery, also, which was almost universal in the courts, was summarily suppressed and all judges were forbidden to receive presents from suitors.[69] To maintain constant watchfulness over them a secret service was organized of trustworthy inspectors who circulated throughout the land in disguise and furnished reports as to their proceedings and reputation.[70] Attention, moreover, was paid to the confused jurisprudence of the period. Since the confirmation of the Siete Partidas of Alfonso X, in 1348, and the issue at the same time of the Ordenamiento de Alcalá, there had been countless laws and edicts published, some of them conflicting and many that had grown obsolete though still legally in force. The greatest jurist of the day, Alfonso Diaz de Montalvo, was employed to gather from these into a code all that were applicable to existing conditions and further to supplement their deficiencies, and this code, known as the Ordenanzas Reales, was accepted and confirmed by the Córtes of Toledo in 1480.[71] This reconstruction of Castilian jurisprudence was completed for the time when, in 1491, Montalvo brought out an edition of the Siete Partidas, noting what provisions had become obsolete and adding what was necessary of the more modern laws. The result of all these strenuous labors is seen in the admiring exclamation of Peter Martyr, in 1492, “Thus we have peace and concord, hitherto unknown in Spain. Justice, which seems to have abandoned other lands, pervades these kingdoms.”[72] The inestimable benefits resulting from this are probably due more especially to Isabella.

Yet I have been led to the conviction that her share in the administration of her kingdom has been exaggerated. The chroniclers of the period were for the most part Castilians who would naturally seek to subordinate the action of the Aragonese intruder, and subsequent writers, in their eagerness to magnify the reputation of Isabella, have followed the example. In the copious royal correspondence with the officials of the Inquisition the name of Isabella rarely appears. To those in Castile as in Aragon Ferdinand mostly writes in the first person singular, without even using the pluralis majestatis; the receiver of confiscations is mi receptor, the royal treasury is mi camera e fisco; the Council of the Inquisition is mi consejo. In spite of the agreement of 1474, the signature Yo la Reina rarely appears alongside of Yo el Rey, and still rarer are Ferdinand’s allusions to la Serenissima Reina, mi muy cara e muy amada muger, while in the occasional letters issued by Isabella during her husband’s absence, she is careful to adduce his authority as that of el Rey mi señor.[73] It is scarce likely that this preponderance of Ferdinand was confined to directing the affairs of the Holy Office.

There has been a tendency of late to regard the Inquisition as a political engine for the conversion of Spain from a medieval feudal monarchy to one of the modern absolute type, but this is an error. The change effected by Ferdinand and Isabella and confirmed by their grandson Charles V was almost wholly wrought, as it had been two centuries earlier in France, by the extension and enforcement of the royal jurisdiction, superseding that of the feudatories.[74] In Castile the latter had virtually ceased to be an instrument of good during the long period of turbulence which preceded the accession of Isabella; something evidently was needed to fill the gap; the zealous and efficient administration of justice, which I have described, not only restored order to the community but went far to exalt the royal power, and, while it abased the nobles, it reconciled the people to possible usurpations which were so beneficent. In the consolidation and maintenance of this no agency was so effective as the institution known as the Santa Hermandad.

Hermandades—brotherhoods or associations for the maintenance of public peace and private rights—were no new thing. In the troubles of 1282, caused by the rebellion of Sancho IV against his father, the first idea of his supporters seems to have been the formation of such organizations.[75] In these associations, however, the police functions were subordinated to the political object of supporting the pretensions of Sancho IV and, recognizing their danger, he dissolved them as soon as he felt the throne assured to him. After his death, his widow the regent Doña María de Molina, organized them anew for the protection of her child, Fernando IV, and again in 1315, when she was a second time regent in the minority of her grandson, Alfonso XI.[76]

The idea was a fruitful one and speedily came to be recognized as a potent instrumentality in the struggle with local disorder and violence. Perhaps the earliest Hermandad of a purely police character, similar to the later ones, was that entered into in 1302 between Toledo, Talavera and Villareal to repress the robberies and murders committed by the Golfines in the district of Xara. Fernando IV not only confirmed the association but ordered the inhabitants to render it due assistance, and subsequent royal letters of the same purport were issued in 1303, 1309, 1312 and 1315.[77] In 1386 Juan I framed a general law providing for the organization and functions of Hermandades, but if any were formed under it at the time they have left no traces of their activity. In 1418 this law was adopted as the constitution of one which organized itself in Santiago, but this accomplished little and, in 1421, the guilds and confraternities of the city united in another for mutual support and succor.[78] There was, in fact, at this time, at least nominally, a general Hermandad, probably organized under the statute of Juan I and possessing written charters and privileges and customs and revenues, with full jurisdiction to try and condemn offenders. It commanded little respect, however, for it complained, in 1418, to Juan II of interference with its revenues and work, in response to which Juan vigorously prohibited all royal and local judges and officials from impeding the Hermandades in any manner. The continuity, nominal at least, of this with subsequent organizations is shown by the confirmation of this utterance by Juan II in 1423, by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1485, by Juana la Loca in 1512 and 1518, by Philip II in 1561, by Philip III in 1601 and by Philip IV in 1621.[79] In the increasing disorder of the times, however, it was impossible, at that period, to maintain the efficiency of the body. In 1443 an attempt was made to reconstruct it, but as soon as it endeavored to repress the lawless nobles and laid siege to Pedro López de Ayala in Salvatierra its forces were cut to pieces and dispersed by Pedro Fernández de Velasco.[80] Some twenty years later, in 1465, when the disorders under Henry IV were culminating, another effort was made. The suffering people organized and taxed themselves to raise a force of 1800 horsemen to render the roads safe, and they endeavored to bring the number up to 3000. It was a popular movement against the nobles and the king hailed it as the work of God who was lifting up the humble against the great. He empowered them to administer justice without appeal except to himself, he told them that they had well earned the name of Santa Hermandad and he urged them earnestly to go forward in the good work. The attempt had considerable success for a time, but it soon languished and was dissolved for lack of the means required to carry it on.[81] Again, in 1473, there was another endeavor to form a Hermandad, but the anarchical forces were too dominant for its successful organization.[82]