Project Gutenberg's The Secret Cache, by E. C. [Ethel Claire] Brill

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Secret Cache

An Adventure and Mystery Story for Boys

Author: E. C. [Ethel Claire] Brill

Illustrator: W. H. Wolf

Release Date: July 24, 2013 [EBook #43293]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SECRET CACHE ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

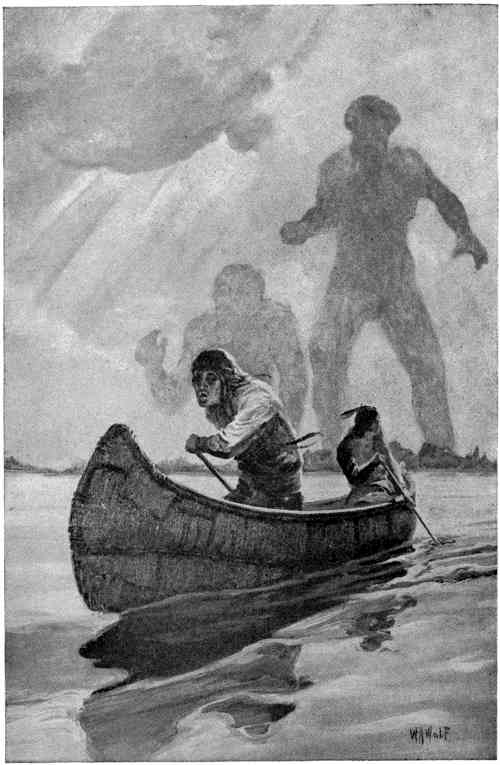

“MONGA LOOKED BACK ONCE JUST IN TIME TO SEE ONE OF THE GIANTS SPRING UP OUT OF THE ROCKS.”

“The Secret Cache.” (See Page 277)

AN ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY

STORY FOR BOYS

BY

E. C. BRILL

ILLUSTRATED

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY

STORIES FOR BOYS

By E. C. BRILL

Large 12 mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

THE SECRET CACHE

SOUTH FROM HUDSON BAY

THE ISLAND OF YELLOW SANDS

Copyright, 1932, by

Cupples & Leon Company

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

On the river bank a boy sat watching the slender birch canoes bobbing about in the swift current. The fresh wind reddened his cheeks and the roaring of the rapids filled his ears. Eagerly his eyes followed the movements of the canoes daringly poised in the stream just below the tossing, foaming, white water. It was the first day of the spring fishing, and more exciting sport than this Indian white-fishing Hugh Beaupré had never seen. Three canoes were engaged in the fascinating game, two Indians in each. One knelt in the stern with his paddle. The other stood erect in the bow, a slender pole fully ten feet long in his hands, balancing with extraordinary skill as the frail craft pitched about in the racing current.

The standing Indian in the nearest canoe was a fine figure of a young man, in close-fitting buckskin leggings, his slender, muscular, bronze body stripped to the waist. Above his black head, bent a little as he gazed intently down into the clear water, gulls wheeled and screamed in anger at the invasion of their fishing ground. Suddenly the fisherman pointed, with a swift movement of his left hand, to the spot where his keen eyes had caught the gleam of a fin. Instantly his companion responded to the signal. With a quick dig and twist of the paddle blade, he shot the canoe forward at an angle. Down went the scoop net on the end of the long pole and up in one movement. A dexterous flirt of the net, and the fish, its wet, silvery sides gleaming in the sun, landed in the bottom of the boat.

The lad on the bank had been holding his breath. Now his tense watchfulness relaxed, and he glanced farther up-stream at the white water boiling over and around the black rocks. A gleam of bright red among the bushes along the shore caught his eye. The tip of a scarlet cap, then a head, appeared above the budding alders, as a man came, with swift, swinging strides, along the shore path.

“Holá, Hugh Beaupré,” he cried, when he was close enough to be heard above the tumult of the rapids. “M’sieu Cadotte, he want you.”

The lad scrambled to his feet. “Monsieur Cadotte sent you for me?” he asked in surprise. “What does he want with me, Baptiste?”

“A messenger from the New Fort has come, but a few moments ago,” Baptiste replied, this time in French.

Hugh, half French himself, understood that language well, though he spoke it less fluently than English.

“From the Kaministikwia? He has brought news of my father?”

“That M’sieu did not tell me, but yes, I think it may be so, since M’sieu sends for you.”

Hugh had scarcely waited for an answer. Before Baptiste had finished his speech, the boy was running along the river path. The French Canadian strode after, the tassel of his cap bobbing, the ends of his scarlet sash streaming in the brisk breeze.

Hastening past the small cabins that faced the St. Mary’s River, Hugh turned towards a larger building, like the others of rough, unbarked logs. Here he knew he should find Monsieur Cadotte, fur trader and agent for the Northwest Fur Company. Finding the door open, the lad entered without ceremony.

Monsieur Cadotte was alone, going through for a second time the reports and letters the half-breed messenger had brought from the Company’s headquarters on the River Kaministikwia at the farther end of Lake Superior. The trader looked up as the boy entered.

“A letter for you, Hugh.” He lifted a packet from the rude table.

“From my father?” came the eager question.

“That I do not know, but no doubt it will give you news of him.”

A strange looking letter Cadotte handed the lad, a thin packet of birch bark tied about with rough cedar cord. On the outer wrapping the name “Hugh Beaupré” was written in a brownish fluid. Hugh cut the cord and removed the wrapper. His first glance at the thin squares of white, papery bark showed him that the writing was not his father’s. The letter was in French, in the same muddy brown ink as the address. The handwriting was good, better than the elder Beaupré’s, and the spelling not so bad as Hugh’s own when he attempted to write French. He had little difficulty in making out the meaning.

“My brother,” the letter began, “our father, before he died, bade me write to you at the Sault de Ste. Marie. In March he left the Lake of Red Cedars with one comrade and two dog sleds laden with furs. At the Fond du Lac he put sail to a bateau, and with the furs he started for the Grand Portage. But wind and rain came and the white fog. He knew not where he was and the waves bore him on the rocks. He escaped drowning and came at last to the Grand Portage and Wauswaugoning. But he was sore hurt in the head and the side, and before the setting of the sun his spirit had left his body. While he could yet speak he told me of you, my half-brother, and bade me write to you. He bade me tell you of the furs and of a packet of value hid in a safe place near the wreck of the bateau. He told me that the furs are for you and me. He said you and I must get them and take them to the New Northwest Company at the Kaministikwia. The packet you must bear to a man in Montreal. Our father bade us keep silence and go quickly. He had enemies, as well I know. So, my brother, I bid you come as swiftly as you can to the Kaministikwia, where I will await you.

Thy half-brother, Blaise Beaupré or Attekonse, Little Caribou.”

Hugh read the strange letter to the end, then turned back to the first bark sheet to read again. He had reached the last page a second time when Cadotte’s voice aroused him from his absorption.

“It is bad news?” the trader asked.

“Yes,” Hugh answered, raising his eyes from the letter. “My father is dead.”

“Bad news in truth.” Cadotte’s voice was vibrant with sympathy. “It was not, I hope, la petite vérole?” His despatches had informed him that the dreaded smallpox had broken out among the Indian villages west of Superior.

“No, he was wrecked.” Hugh hesitated, then continued, “On his spring trip down his boat went on the rocks, and he was so sorely hurt that he lived but a short time.”

“A sad accident truly. Believe me, I feel for you, my boy. If there is anything I can do——” Cadotte broke off, then added, “You will wish to return to your relatives. We must arrange to send you to Michilimackinac on the schooner. From there you can readily find a way of return to Montreal.”

Hugh was at a loss for a reply. He had not the slightest intention of returning to Montreal so soon. He must obey his half-brother’s summons and go to recover the furs and the packet that made up the lads’ joint inheritance. Kind though Cadotte had been, Hugh dared not tell him all. “He bade us keep silence,” Little Caribou had written, and one word in the letter disclosed to Hugh a good reason for silence.

Jean Beaupré had been a free trader and trapper, doing business with the Indians on his own account, not in the direct service of any company. Hugh knew, however, that his father had been in the habit of buying his supplies from and selling his pelts to the Old Northwest Company. Very likely he had been under some contract to do so. Yet in these last instructions to his sons, he bade them take the furs to the New Northwest Company, a secession from and rival to the old organization. He must have had some disagreement, an actual quarrel perhaps, with the Old Company. The rivalry between the fur companies was hot and bitter. Hugh was very sure that if Monsieur Cadotte learned of the hidden pelts, he would inform his superiors. Then, in all probability, the Old Northwest Company’s men would reach the cache first. Certainly, if he even suspected that the pelts were destined for the New Company, Cadotte would do nothing to further and everything to hinder Hugh’s project. The boy was in a difficult position. He had to make up his mind quickly. Cadotte was eying him sharply and curiously.

“I cannot return to Montreal just yet, Monsieur Cadotte,” Hugh said at last. “This letter is from my half-brother.” He paused in embarrassment.

Cadotte nodded and waited for the boy to go on. The trader knew that Jean Beaupré had an Indian wife, and supposed that Hugh had known it also. Part Indian himself, Cadotte could never have understood the lad’s amazement and consternation at learning now, for the first time, of his half-brother.

“My father,” Hugh went on, “bade Blaise, my half-brother, tell me to—come to the Kaministikwia and meet Blaise there. He wished me to—to make my brother’s acquaintance and—and receive from him—something my father left me,” he concluded lamely.

Cadotte was regarding Hugh keenly. The boy’s embarrassed manner was enough to make him suspect that Hugh was not telling the truth. Cadotte shrugged his shoulders. “It may be difficult to send you in that direction. If you were an experienced canoeman, but you are not and——”

“But I must go,” Hugh broke in. “My father bade me, and you wouldn’t have me disobey his last command. Can’t I go in the Otter? I still have some of the money my aunt gave me. If I am not sailor enough to work my way, I can pay for my passage.”

“Eh bien, we will see what can be done,” Cadotte replied more kindly. Perhaps the lad’s earnestness and distress had convinced him that Hugh had some more urgent reason than a mere boyish desire for adventure, for making the trip. “I will see if matters can be arranged.”

His mind awhirl with conflicting thoughts and feelings, Hugh Beaupré left Cadotte. The preceding autumn Hugh had come from Montreal to the Sault de Ste. Marie. Very reluctantly his aunt had let him go to be with his father in the western wilderness for a year or two of that rough, adventurous life. Hugh’s Scotch mother had died when he was less than a year old, nearly sixteen years before the opening of this story. His French father, a restless man of venturesome spirit, had left the child with the mother’s sister, and had taken to the woods, the then untamed wilderness of the upper Great Lakes and the country beyond. In fifteen years he had been to Montreal to see his son but three times. During each brief stay, his stories of the west had been eagerly listened to by the growing boy. On his father’s last visit to civilization, Hugh had begged to be allowed to go back to Lake Superior with him. The elder Beaupré, thinking the lad too young, had put him off. He had consented, however, to his son’s joining him at the Sault de Ste. Marie a year from the following autumn, when Hugh would be sixteen.

Delayed by bad weather, the boy had arrived at the meeting place late, only to find that his father had not been seen at the Sault since his brief stop on his return from Montreal the year before. The disappointed lad tried to wait patiently, but the elder Beaupré did not come or send any message. At last, word arrived that he had left the Grand Portage, at the other end of Lake Superior, some weeks before, not to come to the Sault but to go in the opposite direction to his winter trading ground west of the lake. There was no chance for Hugh to follow, even had he known just where his father intended to winter. By another trader going west and by a Northwest Company messenger, the boy sent letters, hoping that in some manner they might reach Jean Beaupré. All winter Hugh had remained at the Sault waiting for some reply, but none of any sort had come until the arrival of the strange packet he was now carrying in his hand. This message from his younger brother seemed to prove that his father must have received at least one of Hugh’s letters. Otherwise he would not have known that his elder son was at the Sault. But there was no explanation of Jean Beaupré’s failure to meet the boy there.

Hugh was grieved to learn of his parent’s death, but he could not feel the deep sorrow that would have overwhelmed him at the loss of an intimately known and well loved father. Jean Beaupré was almost a stranger to his older son. Hugh remembered seeing him but the three times and receiving but one letter from him. Indeed he was little more than a casual acquaintance whose tales of adventure had kindled a boy’s imagination. It was scarcely possible that Hugh’s grief could be deep, and, for the time being, it was overshadowed by other feelings. He had been suddenly plunged, it seemed, into a strange and unexpected adventure, which filled his mind to the exclusion of all else.

He must find some way to reach the Kaministikwia River, there to join his newly discovered Indian brother in a search for the wrecked bateau and its cargo of pelts. Of that half-brother Hugh had never heard before. He could not but feel a sense of resentment that there should be such a person. The boy had been brought up to believe that his father had loved his bonny Scotch wife devotedly, and that it was his inconsolable grief at her death that had driven him to the wilderness. It seemed, however, that he must have consoled himself rather quickly with an Indian squaw. Surely the lad who had written the letter must be well grown, not many years younger than Hugh himself.

As he walked slowly along the river bank, Hugh turned the bark packet over and over in his hand, and wondered about the half-breed boy who was to be his comrade in adventure. Attekonse had not spent his whole life in the woods, that was evident. Somewhere he had received an education, had learned to write French readily and in a good hand. Perhaps his father had taught him, thought Hugh, but quickly dismissed that suggestion. He doubted if the restless Jean Beaupré would have had the patience, even if he had had the knowledge and ability to teach his young son to write French so well.

Uncertain what he ought to do next, the puzzled boy wandered along, glancing now and then at the canoes engaged in the white-fishing below the rapids. That daring sport had lost its interest for him. At the outskirts of an Indian village, where he was obliged to beat off with a stick a pack of snarling, wolf-like dogs, he turned and went back the way he had come, still pondering over the birch bark letter.

Presently he caught sight once more of Baptiste’s scarlet cap. No message from Cadotte had brought the simple fellow this time, merely his own curiosity. Hugh was quite willing to answer Baptiste’s questions so far as he could without betraying too much. Seated in a sheltered, sunny spot on an outcrop of rock at the river’s edge, he told of his father’s death. Then, suddenly, he resolved to ask the good-natured Canadian’s help.

“Baptiste, I am in a difficulty. My half-brother who wrote this,”—Hugh touched the bark packet—“bids me join him at the Kaministikwia. It was my father’s last command that I should go there and meet this Blaise or Little Caribou, as he calls himself. We are to divide the things father left for us.”

“There is an inheritance then?” questioned Baptiste, interested at once.

“Nothing that amounts to much, I fancy,” the lad replied with an assumption of carelessness; “some personal belongings, a few pelts perhaps. For some reason he wished Blaise and me to meet and divide them. It is a long journey for such a matter.”

“Ah, but a dying father’s command!” cried Baptiste. “You must not disobey that. To disregard the wishes of the dead is a grievous sin, and would surely bring you misfortune.”

“True, but what can I do, Baptiste? Monsieur Cadotte doesn’t feel greatly inclined to help me. He wishes me to return to Montreal. How then am I to find an opportunity to go to the Kaministikwia?”

Baptiste took a long, thoughtful pull at his pipe, then removed it from his mouth. “There is the sloop Otter,” he suggested.

“Would Captain Bennett take me, do you think?”

“I myself go as one of the crew. To-morrow early I go to Point aux Pins. Come with me and we shall see.”

“Gladly,” exclaimed Hugh. “When does she sail?”

“Soon, I think. There were repairs to the hull, where she ran on the rocks, but they are finished. Then there is new rigging and the painting. It will not be long until she is ready.”

That night Hugh debated in his own mind whether he should tell Cadotte of his proposed visit with Baptiste to Point aux Pins. He decided against mentioning it at present. He did not know what news might have come in Cadotte’s despatches, whether the trader was aware of the elder Beaupré’s change of allegiance. At any rate, thought the lad, it would be better to have his passage in the Otter arranged for, if he could persuade her captain, before saying anything more to anyone.

Early the next morning Baptiste and Hugh embarked above the rapids in Baptiste’s small birch canoe. The distance to Point aux Pins was short, but paddling, even in the more sluggish channels, against the current of the St. Mary’s River in spring flood was strenuous work, as Hugh, wielding the bow blade, soon discovered. Signs of spring were everywhere. The snow was gone, and flocks of small, migrating birds were flitting and twittering among the trees and now and then bursting into snatches of song. The leaves of birches, willows and alders were beginning to unfold, the shores showing a faint mist of pale green, though here and there in the quiet backwaters among rocks and on the north sides of islands, ice still remained.

At Point aux Pins, or Pine Point, was the Northwest Company’s shipyard. In a safe and well sheltered harbor, formed by the long point that ran out into the river, the sailing vessels belonging to the company were built and repaired. The sloop Otter, which had spent the winter there, was now anchored a little way out from shore. The repairs had been completed and a fresh coat of white paint was being applied to her hull. Tents and rude cabins on the sandy ground among scrubby jack pines and willows housed the workers, and near by, waiting for the fish cleanings and other refuse to be thrown out, a flock of gulls, gray-winged, with gleaming white heads and necks, rode the water like a fleet of little boats. As the canoe approached, the birds, with a splashing and beating of wings, rose, whirled about in the air, and alighted again farther out, each, as it struck the water, poising for a moment with black-tipped wings raised and half spread.

On a stretch of sand beyond the shipyard, Baptiste and Hugh landed, stepping out, one on each side, the moment the canoe touched, lifting it from the water and carrying it ashore. Then they sought the master of the sloop.

Captain Bennett was personally superintending the work on his ship. To him Baptiste, who had been previously engaged as one of the small crew, made known Hugh’s wish to sail to the Kaministikwia. The shipmaster turned sharply on the lad, demanding to know his purpose in crossing the lake. Hugh explained as well as he could, without betraying more than he had already told Cadotte and Baptiste.

“Do you know anything of working a ship?” Captain Bennett asked.

“I have sailed a skiff on the St. Lawrence,” was the boy’s reply. “I can learn and I can obey orders.”

“Um,” grunted the Captain. “At least you are a white man. I can use one more man, and I don’t want an Indian. I can put you to work now. If you prove good for anything, I will engage you for the trip over. Here, Duncan,” to a strapping, red-haired Scot, “give these fellows something to do.”

So it came about that Hugh Beaupré, instead of going back at once to the Sault, remained at the Point aux Pins shipyard. He returned in the Otter, when, three days later, she sailed down the St. Mary’s to the dock above the rapids where she was to receive her lading. In the meantime, by an Indian boy, Hugh had sent a message to Cadotte informing him that he, Hugh Beaupré, had been accepted as one of the crew of the Otter for her trip to the Kaministikwia. Cadotte had returned no reply, so Hugh judged that the trader did not intend to put any obstacles in the way of his adventure.

The goods the sloop was to transport had been received the preceding autumn by ship from Michilimackinac too late to be forwarded across Superior. They were to be sent on now by the Otter. A second Northwest Company ship, the Invincible, which had wintered in Thunder Bay, was expected at the Sault in a few weeks. When the great canoe fleet from Montreal should arrive in June, part of the goods brought would be transferred to the Invincible, while the remainder would be taken on in the canoes. Hugh was heartily glad that he was not obliged to wait for the fleet. In all probability there would be no vacant places, and if there were any, he doubted if, with his limited experience as a canoeman, he would be accepted. He felt himself lucky to obtain a passage on the Otter.

The sloop was of only seventy-five tons burden, but the time of loading was a busy one. The cargo was varied: provisions, consisting largely of corn, salt pork and kegs of tried out grease, with some wheat flour, butter, sugar, tea and other luxuries for the clerks at the Kaministikwia; powder and shot; and articles for the Indian trade, blankets, guns, traps, hatchets, knives, kettles, cloth of various kinds, vermilion and other paints, beads, tobacco and liquor, for the fur traders had not yet abandoned the disastrous custom of selling strong drink to the Indians.

During the loading Hugh had an opportunity to say good-bye to Cadotte. The latter’s kindness and interest in the boy’s welfare made him ashamed of his doubts of the trader’s intentions.

On a clear, sunny morning of the first week in May, the Northwest Company’s sloop Otter, with a favoring wind, made her way up-stream towards the gateway of Lake Superior. At the Indian village on the curve of the shore opposite Point aux Pins, men, women, children and sharp-nosed dogs turned out to see the white-sailed ship go by. Through the wide entrance to the St. Mary’s River, where the waters of Lake Superior find their outlet, the sloop sailed under the most favorable conditions. Between Point Iroquois on the south and high Gros Cap, the Great Cape, on the north, its summit indigo against the bright blue of the sky, she passed into the broad expanse of the great lake. The little fur-trading vessels of the first years of the nineteenth century did not follow the course taken by the big passenger steamers and long freighters of today, northwest through the middle of the lake. Instead, the Captain of the Otter took her almost directly north.

The southerly breeze, light at first, freshened within a few hours, and the sloop sailed before it like a gull on the wing. Past Goulais Point and Coppermine Point and Cape Gargantua, clear to Michipicoton Bay, the first stop, the wind continued favorable, the weather fine. It was remarkably fine for early May, and Hugh Beaupré had hopes of a swift and pleasant voyage. So far his work as a member of the crew of six was not heavy. Quick-witted and eager to do his best, he learned his duties rapidly, striving to obey on the instant the sharply spoken commands of master and mate.

At the mouth of the Michipicoton River was a Northwest Company trading post, and there the Otter ran in to discharge part of her cargo of supplies and goods. She remained at Michipicoton over night, and, after the unloading, Hugh was permitted to go ashore. The station, a far more important one, in actual trade in furs, than the post at the Sault, he found an interesting place. Already some of the Indians were arriving from the interior, coming overland with their bales of pelts on dog sleds. When the Michipicoton River and the smaller streams should be free of ice, more trappers would follow in their birch canoes.

As if on purpose to speed the ship, the wind had shifted to the southeast by the following morning. The weather was not so pleasant, however, for the sky was overcast. In the air was a bitter chill that penetrated the thickest clothes. Captain Bennett, instead of appearing pleased with the direction of the breeze, shook his head doubtfully as he gazed at the gloomy sky and the choppy, gray water. A sailing vessel must take advantage of the wind, so, in spite of the Captain’s apprehensive glances, the Otter went on her way.

All day the wind held favorable, shifting to a more easterly quarter and gradually rising to a brisk blow. The sky remained cloudy, the distance thick, the water green-gray.

As darkness settled down, rain began to fall, fine, cold and driven from the east before a wind strong enough to be called a gale. In the wet and chill, the darkness and rough sea, Hugh’s work was far harder and more unpleasant. But he made no complaint, even to himself, striving to make up by eager willingness for his ignorance of a sailor’s foul weather duties. There was no good harbor near at hand, and, the gale being still from the right quarter, Captain Bennett drove on before it. After midnight the rain turned to sleet and snow. The wind began to veer and shift from east to northeast, to north and back again.

Before morning all sense of location had been lost. Under close-reefed sails, the sturdily built little Otter battled wind, waves, sleet and snow. She pitched and tossed and wallowed. All hands remained on deck. Hugh, sick and dizzy with the motion, chilled and shivering in the bitter cold, wished from the bottom of his heart he had never set foot upon the sloop. Struggling to keep his footing on the heaving, ice-coated deck, and to hold fast to slippery, frozen ropes, he was of little enough use, though he did his best.

The dawn brought no relief. In the driving snow, neither shore nor sky was to be seen, only a short stretch of heaving, lead-gray water. Foam-capped waves broke over the deck. Floating ice cakes careened against the sides of the ship. On the way to Michipicoton no ice had been encountered, but now the tossing masses added to the peril.

Midday might as well have been midnight. The falling snow, fine, icy, stinging, shut off all view more completely than blackest darkness. The weary crew were fighting ceaselessly to keep the Otter afloat. The Captain himself clung with the steersman to the wheel. Then, quite without warning, out of the northeast came a sudden violent squall. A shriek of rending canvas, and the close-reefed sail, crackling with ice, was torn away. Down crashed the shattered mast. As if bound for the bottom of the lake, the sloop wallowed deep in the waves.

Hugh sprang forward with the others. On the slanting, ice-sheathed deck, he slipped and went down. He was following the mast overboard, when Baptiste seized him by the leg. The dangerous task of cutting loose the wreckage was accomplished. The plucky Otter righted herself and drove on through the storm.

With the setting of the sun, invisible through the snow and mist, the wind lessened. But that night, if less violent than the preceding one, was no less miserable. Armored in ice and frozen snow, the sloop rode heavy and low, battered by floating cakes, great waves washing her decks. She had left the Sault on a spring day. Now she seemed to be back in midwinter. Yet, skillfully handled by her master, she managed to live through the night.

Before morning, the wind had fallen to a mere breeze. The waves no longer swept the deck freely, but the lake was still so rough that the ice-weighted ship made heavy going. Her battle with the storm had sprung her seams. Two men were kept constantly at the pumps. No canvas was left but the jib, now attached to the stump of the mast. With this makeshift sail, and carried along by the waves, she somehow kept afloat.

From the lookout there came a hoarse bellow of warning. Through the muffling veil of falling snow, his ears had caught the sound of surf. The steersman swung the wheel over. The ship sheered off just as the foaming crests of breaking waves and the dark mass of bare rocks appeared close at hand.

Along the abrupt shore the Otter beat her way, her captain striving to keep in sight of land, yet far enough out to avoid sunken or detached rocks. Anxiously his tired, bloodshot eyes sought for signs of a harbor. It had been so long since he had seen sun or stars that he had little notion of his position or of what that near-by land might be. Shadowy as the shore appeared in the falling snow, its forbidding character was plain enough, cliffs, forest crowned, rising abruptly from the water, and broken now and then by shallow bays lined with tumbled boulders. Those shallow depressions promised no shelter from wind and waves, even for so small a ship as the Otter.

No less anxiously than Captain Bennett did Hugh Beaupré watch that inhospitable shore. So worn was he from lack of sleep, exhausting and long continued labor and seasickness, so chilled and numbed and weak and miserable, that he could hardly stand. But the sight of solid land, forbidding though it was, had revived his hope.

A shout from the starboard side of the sloop told him that land had appeared in that direction also. In a few minutes the Otter, running before the wind, was passing between forest-covered shores. As the shores drew closer together, the water became calmer. On either hand and ahead was land. The snow had almost ceased to fall now. The thick woods of snow-laden evergreens and bare-limbed trees were plainly visible.

Staunch little craft though the Otter was, her strained seams were leaking freely, and her Captain had decided to beach her in the first favorable spot. A bit of low point, a shallow curve in the shore with a stretch of beach, served his purpose. There he ran his ship aground, and made a landing with the small boat.

His ship safe for the time being, Captain Bennett’s next care was for his crew. That they had come through the storm without the loss of a man was a matter for thankfulness. Everyone, however, from the Captain himself to Hugh, was worn out, soaked, chilled to the bone and more or less battered and bruised. One man had suffered a broken arm when the mast went over side, and the setting of the bone had been hasty and rough. The mate had strained his back painfully.

All but the mate and the man with the broken arm, the Captain set to gathering wood and to clearing a space for a camp on the sandy point. The point was almost level and sparsely wooded with birch, mountain ash and bushes. Every tree and shrub, its summer foliage still in the bud, was wet, snow covered or ice coated. Birch bark and the dry, crumbly center of a dead tree trunk made good tinder, however. Baptiste, skilled in the art of starting a blaze under the most adverse conditions, soon had a roaring fire. By that time the snow had entirely ceased, and the clouds were breaking.

Around the big fire the men gathered to dry their clothes and warm their bodies, while a thick porridge of hulled corn and salt pork boiled in an iron kettle over a smaller blaze. The hot meal put new life into the tired men. The broken arm was reset, the minor injuries cared for, and a pole and bark shelter, with one side open to the fire, was set up. Before the lean-to was completed the sun was shining. In spite of the sharp north wind, the snow and ice were beginning to melt. A flock of black-capped chickadees were flitting about the bare-branched birches, sounding their brave, deep-throated calls, and a black and white woodpecker was hammering busily at a dead limb.

No attempt was made to repair the ship that day. Only the most necessary work was done, and the worn-out crew permitted to rest. A lonely place seemed this unknown bay or river mouth, without white man’s cabin, Indian’s bark lodge or even a wisp of smoke from any other fire. But the sheltered harbor was a welcome haven to the sorely battered ship and the exhausted sailors. Wolves howled not far from the camp that night, and next morning their tracks were found in the snow on the beach close to where the sloop lay. It would have required far fiercer enemies than the slinking, cowardly, brush wolves to disturb the rest of the tired crew of the Otter. Hugh did not even hear the beasts.

Shortly after dawn work on the Otter was begun. The water was pumped out, most of the cargo piled on the beach, and the sloop hauled farther up by means of a rudely constructed windlass. Then the strained seams were calked and a few new boards put in. A tall, straight spruce was felled and trimmed to replace the broken mast, and a small mainsail devised from extra canvas. The repairs took two long days of steady labor. During that time the weather was bright, and, except in the deeply shaded places, the snow and ice disappeared rapidly.

From the very slight current in the water, Captain Bennett concluded that the place where he had taken refuge was a real bay, not a river mouth. He had not yet discovered whether he was on the mainland or an island. The repairs to his ship were of the first importance, and he postponed determining his whereabouts until the Otter was made seaworthy once more. Not a trace of human beings had been found. The boldness of the wolves and lynxes, that came close to the camp every night, indicated that no one, red or white, was in the habit of visiting this lonely spot.

On the third day the sloop was launched, anchored a little way from shore and rigged. While the reloading was going on, under the eyes of the mate, the Captain, with Baptiste and Hugh at the oars, set out in the small boat for the harbor mouth.

The shore along which they rowed was, at first, wooded to the water line. As they went farther out and the bay widened, the land they were skirting rose more steeply, edged with sheer rocks, cliffs and great boulders. From time to time Captain Bennett glanced up at the abrupt rocks and forested ridges on his right, or across to the lower land on the other side of the bay. Directly ahead, some miles across the open lake, he could see a distant, detached bit of land, an island undoubtedly. Most of the time, however, his eyes were on the water. He was endeavoring to locate the treacherous reefs and shallows he must avoid when he took his ship out of her safe harbor.

An exclamation from Baptiste, who had turned his head to look to the west and north, recalled the Captain from his study of the unfamiliar waters. Beyond the tip of the opposite or northwestern shore of the bay, far across the blue lake to the north, two dim, misty shapes had come into view.

“Islands!” Captain Bennett exclaimed. “High, towering islands.”

Baptiste and Hugh pulled on with vigorous strokes. Presently the Captain spoke again. “Islands or headlands. Go farther out.”

The two bent to their oars. As they passed beyond the end of the low northwestern shore, more high land came into view across the water.

“What is it, Baptiste? Where are we?” asked Hugh, forgetting in his eagerness that it was not his place to speak.

“It is Thunder Cape,” the Captain replied, overlooking the breach of discipline, “the eastern boundary of Thunder Bay, where the Kaministikwia empties and the New Fort is situated.”

“Truly it must be the Cap au Tonnerre, the Giant that Sleeps,” Baptiste agreed, resting on his oars to study the long shape, like a gigantic figure stretched out at rest upon the water. “The others to the north are the Cape at the Nipigon and the Island of St. Ignace.”

“We are not as far off our course as I feared,” remarked the Captain with satisfaction.

Hugh ventured another question. “What then, sir, is this land where we are?”

Captain Bennett scanned the horizon as far as he could see. “Thunder Cape lies a little to the north of west,” he said thoughtfully. “We are on an island of course, a large one. There is only one island it can be, the Isle Royale. I have seen one end or the other of Royale many times from a distance, when crossing to the Kaministikwia or to the Grand Portage, but I never set foot on the island before.” Again he glanced up at the steep rocks and thick woods on his right, then his eyes sought the heaving blue of the open lake. “This northwest breeze would be almost dead against us, and it is increasing. We’ll not set sail till morning. By that time I think we shall have a change of wind.”

Their purpose accomplished, the oarsmen turned the boat and started back towards camp. Hugh, handling the bow oars, watched the shore close at hand. They were skirting a rock cliff, sheer from the lake, its brown-gray surface stained almost black at the water line, blotched farther up with lichens, black, orange and green-gray, and worn and seamed and rent with vertical cracks from top to bottom. The cracks ran in diagonally, opening up the bay. As Hugh came into clear view of one of the widest of the fissures, he noticed something projecting from it.

“See, Baptiste,” he cried, pointing to the thing, “someone has been here before us.”

The French Canadian rested on his oars and spoke to Captain Bennett. “There is the end of a boat in that hole, M’sieu, no birch canoe either. How came it here in this wilderness?”

“Row nearer,” ordered the shipmaster, “and we’ll have a look at it.”

The two pulled close to the mouth of the fissure. At the Captain’s order, Baptiste stepped over side to a boulder that rose just above the water. From the boulder he sprang like a squirrel. His moccasined feet gripped the rim of the old boat, and he balanced for an instant before jumping down. Hugh, in his heavier boots, followed more clumsily. Captain Bennett remained in the rowboat.

The wrecked craft in which the two found themselves was tightly wedged in the crack. The bow was smashed and splintered and held fast by the ice that had not yet melted in the dark, cold cleft. Indeed the boat was half full of ice. It was a crude looking craft, and its sides, which had never known paint, were weathered and water stained to almost the same color as the blackened base of the rocks. The wreck was quite empty, not an oar or a fragment of mast or canvas remaining.

The old boat had one marked peculiarity which could be seen even in the dim light of the crack. The thwart that bore the hole where the mast had stood was painted bright red, the paint being evidently a mixture of vermilion and grease. It was but little faded by water and weather, and on the red background had been drawn, in some black pigment, figures such as the Indians used in their picture writing. Hugh had seen birch canoes fancifully decorated about prow and stern, and he asked Baptiste if such paintings were customary on the heavier wooden boats as well.

“On the outside sometimes they have figures in color, yes,” was the reply, “but never have I seen one painted in this way.”

“I wonder what became of the men who were in her when she was driven on these rocks.”

Baptiste shook his head. “It may be that no one was in her. What would he do so far from the mainland? No, I do not think anyone was wrecked here. This bateau was carried away in a storm from some beach or anchorage on the north or west shore. There is nothing in her, though she was right side up when she was driven in here by the waves. And here, in this lonely place, there has been no one to plunder her.”

“Do no Indians live on this big island?” queried Hugh.

“I have never heard of anyone living here. It is far to come from the mainland, and I have been told that the Indians have a fear of the place. They think it is inhabited by spirits, especially one bay they call the Bay of Manitos. It is said that in the old days the Ojibwa came here sometimes for copper. They picked up bits of the metal on the beaches and in the hills. Nowadays they have a tale that spirits guard the copper stones.”

“If there is copper on the island perhaps this boat belonged to some white prospector,” suggested Hugh.

Baptiste shrugged his shoulders. “Perhaps, but then the Indian manitos must have destroyed him.”

“Well, at any rate the old manitos haven’t troubled us,” Hugh commented.

Again Baptiste shrugged. “We have not disturbed their copper, and—we are not away from the place yet.”

The inspection of the wreck did not take many minutes. When Baptiste made his report, the Captain agreed with him that the boat had probably drifted away from some camp or trading post on the mainland, and had been driven into the cleft in a storm. As nothing of interest had been found in the wreck, he ordered Baptiste and Hugh to make speed back to camp.

By night the reloading was finished and everything made ready for an early start. After sunset, the mate, adventuring up the bay, shot a yearling moose. The crew of the Otter feasted and, to celebrate the completion of the work on the sloop, danced to Baptiste’s fiddle. From the ridges beyond and above the camp, the brush wolves yelped in response to the music.

Baptiste’s half superstitious, half humorous forebodings of what the island spirits might do to the crew of the Otter came to nothing, but Captain Bennett’s prophecy of a change of wind proved correct. The next day dawned fair with a light south breeze that made it possible for the sloop to sail out of harbor. She passed safely through the narrower part of the bay. Then, to avoid running close to the towering rocks which had first appeared to her Captain through the falling snow, he steered across towards the less formidable appearing northwest shore. That shore proved to be a low, narrow, wooded, rock ridge running out into the lake. When he reached the tip of the point, he found it necessary to go on some distance to the northeast to round a long reef. The dangerous reef passed, he set his course northwest towards the dim and distant Sleeping Giant, the eastern headland of Thunder Bay.

To the relief of Hugh Beaupré, the last part of the voyage was made in good time and without disaster. The boy looked with interest and some awe at the towering, forest-clad form of Thunder Cape, a mountain top rising from the water. On the other hand, as the Otter entered the great bay, were the scarcely less impressive heights of the Isle du Paté, called to-day, in translation of the French name, Pie Island. Hugh asked Baptiste how the island got its name and learned that it was due to some fancied resemblance of the round, steep-sided western peak to a French paté or pastry.

By the time the sloop was well into Thunder Bay, the wind, as if to speed her on her way, had shifted to southeast. Clouds were gathering and rain threatened as she crossed to the western shore, to the mouth of the Kaministikwia. The river, flowing from the west, discharges through three channels, forming a low, triangular delta. The north channel is the principal mouth, and there the sloop entered, making her way about a mile up-stream to the New Fort of the Northwest Company.

From the organization of the Northwest Fur Company down to a short time before the opening of this story, the trading post at the Grand Portage, south of the Pigeon River, and about forty miles by water to the southwest of the Kaministikwia, had been the chief station and headquarters of the company. The ground where the Grand Portage post stood became a part of the United States when the treaty of peace after the Revolution established the Pigeon River as the boundary line between the United States and the British possessions. Though the Northwest Company was a Canadian organization, it retained its headquarters south of the Pigeon River through the last decade of the eighteenth century. In the early years of the nineteenth, however, when the United States government proposed to levy a tax on all English furs passing through United States territory, the company headquarters was removed to Canadian soil. Near the mouth of the Kaministikwia River on Thunder Bay was built the New Fort, later to be known as Fort William after William McGillivray, head of the company.

The Northwest Fur Company’s chief post was bustling with activity. The New Fort itself, a stockaded enclosure, had been completed the year before, but work on the log buildings within the walls was still going on. Quarters for the agents, clerks and various employees, storehouses, and other buildings were under construction or receiving finishing touches. When the sloop Otter came in sight, however, work ceased suddenly. Log cabin builders threw down their axes, saws and hammers, masons dropped their trowels, brick makers left the kilns that were turning out bricks for chimneys and ovens, the clerks broke off their bartering with Indians and half-breed trappers, and all ran down to the riverside. There they mingled with the wild looking men, squaws and children who swarmed from the camps of the voyageurs and Indians. When the Otter drew up against the north bank of the channel, the whole population, permanent and temporary, was on hand to greet the first ship of the season.

From the deck of the sloop, Hugh Beaupré looked on with eager eyes. It was not so much of the picturesqueness and novelty of the scene, however, as of his own private affairs that he was thinking. Anxiously he scanned the crowd of white men, half-breeds and Indians, wondering which one of the black-haired, deerskin-clad, half-grown lads, who slipped so nimbly between their elders into the front ranks, was his half-brother. Many of the crowd, old and young, white and red, came aboard, but none sought out Hugh. He concluded that Blaise was either not there or was waiting for him to go ashore.

Hugh soon had an opportunity to leave the ship. He had feared that he might be more closely questioned by Captain Bennett or by some of the crew about what he intended to do at the Kaministikwia, and was relieved to reach shore without having to dodge the curiosity of his companions. Only Baptiste asked him where he expected to meet his brother. Hugh replied truthfully that he did not know.

Unobtrusively, calling as little attention to himself as possible, the boy made his way through the crowd, but not towards the New Fort. No doubt the Fort, with all its busy activity in its wilderness surroundings, was worth seeing, but he did not choose to visit the place for fear someone might ask his business there. He was keenly aware that his business was likely to be, not with the Old Northwest Company, but with its rival, the New Northwest Company, sometimes called in derision the X Y Company. In a quandary where to look for his unknown brother, he wandered about aimlessly for a time, avoiding rather than seeking companionship.

The ground about the New Fort was low and swampy, with thick woods of evergreens, birch and poplar wherever the land had not been cleared for building or burned over through carelessness. Away from the river bank and the Fort, the place was not cheerful or encouraging to a lonely boy on that chill spring day. The sky was gray and lowering, the wind cold, the distance shrouded in fog, the air heavy with the earthy smell of damp, spongy soil and sodden, last year’s leaves. Hugh had looked forward with eager anticipation to his arrival at the Kaministikwia, but now all things seemed to combine to make him low spirited and lonely.

That the X Y Company had a trading post somewhere near the New Fort Hugh knew, but he had no idea which way to go, and he did not wish to inquire. At last he turned by chance into a narrow path that led through the woods up-river. He was walking slowly, so wrapped in his own not very pleasant thoughts as to be scarcely conscious of his surroundings, when a voice sounded close at his shoulder. It was a low, soft voice, pronouncing his own name, “Hugh Beaupré,” with an intonation that was not English.

Startled, Hugh whirled about, his hand on the sheathed knife that was his only weapon. Facing him in the narrow trail stood a slender lad of less than his own height, clad in a voyageur’s blanket coat over the deerskin tunic and leggings of the woods and with a scarlet handkerchief bound about his head instead of a cap. His dark features were unmistakably Indian in form, but from under the straight, black brows shone hazel eyes that struck Hugh with a sense of familiarity. They were the eyes of his father, Jean Beaupré, the bright, unforgettable eyes that had been the most notable feature of the elder Beaupré’s face.

“Hugh Beaupré?” the dark lad repeated with a questioning inflection. “My brother?”

“You are my half-brother Blaise?” Hugh asked, somewhat stiffly, in return.

“Oui,” the other replied, and added apologetically in excellent French, “My English is bad, but you perhaps know French.”

“Let it be French then, though I doubt if I speak it as well as you.”

A swift smile crossed the hitherto grave face. “I was at school with the Jesuit fathers in Quebec four winters,” Blaise answered.

Hugh was surprised. This new brother looked like an Indian, but he was no mere wild savage. The schooling in Quebec accounted for the well written letter. Before Hugh could find words in which to voice his thoughts, Blaise spoke again.

“I was on the shore when the Otter arrived. I thought when I saw you, you must be my brother, though you have little the look of our father, neither the hair nor the eyes.”

“I have been told that I resemble my mother’s people.” Hugh’s manner was still cool and stiff.

Without comment upon the reply, Blaise went on in his low, musical voice with its slightly singsong drawl. “I wished not to speak to you there among the others. I waited until I saw you take this trail. Then, after a little while, I followed.”

“Do you mean you have been following me around ever since I came ashore?” Hugh exclaimed in English.

“Not following.” The swift smile so like, yet unlike, that of Jean Beaupré, crossed the boy’s face again. “Not following, but,”—he dropped into French-“I watched. It was not difficult, since you thought not that anyone watched. We will go on now a little farther. Then we will talk together, my brother.”

Passing Hugh, Blaise took the lead, going along the forest trail with a lithe swiftness that spurred the older lad to his fastest walking pace. After perhaps half a mile, they came to the top of a low knoll where an opening had been made by the fall of a big spruce. Blaise seated himself on the prostrate trunk, and Hugh dropped down beside him, more eager than he cared to betray to hear his Indian brother’s story.

A strange tale the younger lad had to tell. Jean Beaupré had spent the previous winter trading and trapping in the country south of the Lake of the Woods, now included in the state of Minnesota. Blaise and his mother had remained at Wauswaugoning Bay, north of the Grand Portage. Just at dusk of a night late in March, Beaupré staggered into their camp, his face ghastly, his clothes blood stained, mind and body in the last stages of exhaustion. At the lodge entrance he fell fainting. It was some time before his squaw and his son succeeded in bringing him back to consciousness. In spite of his weakness he was determined to tell his story. Mustering all his failing strength, he commenced.

Before the snow had begun to melt under the spring sun, he had started, he told them, with one Indian companion and two dog sleds loaded with pelts, for Lake Superior. Travelling along the frozen streams and lakes, he reached the trading post at the Fond du Lac on the St. Louis River. While he was there, a spell of unusually warm early spring weather cleared the river mouth. The winter had been mild, with little ice in that part of the lake. At Fond du Lac Beaupré obtained a bateau, as the Canadians called their wooden boats, and rigged it with mast and sail. He and his companion put their furs aboard, and started up the northwest shore of Lake Superior.

Thus far he succeeded in telling his story clearly enough, then, worn out with the effort, he lapsed into unconsciousness. Twice he rallied and tried to go on, but his speech was vague and disconnected. As well as he could, Blaise pieced together the fragments of the story. Somewhere between the Fond du Lac and the Grand Portage the bateau had been wrecked in a storm. When he reached this part of his tale, Jean Beaupré became much agitated. He gasped out again and again that he had hidden the furs and the “packet” in a safe cache, and that Blaise and his other son Hugh must go get them. He called the furs his sons’ inheritance, for he was clearly aware that he could not live. The pelts were a very good season’s catch, and the boys must take them to the New Northwest Company’s post at the Kaministikwia. But it was the packet about which he seemed most anxious. Hugh must carry the packet to Montreal to Monsieur Dubois. Blaise asked where his brother was to be found, and received instructions to go or send to the Sault. Before the lad learned definitely where to look for the furs and the packet, Jean Beaupré lapsed once more into unconsciousness. He rallied only long enough for the ministrations of a priest, who happened to be at the Grand Portage on a missionary journey.

Though Hugh had scarcely known his father, he was much moved at the story of his death. He felt a curious mixture of sympathy for and jealousy of his Indian half-brother, when he saw, in spite of the latter’s controlled and quiet manner, how strongly he felt his loss. Hugh respected the depth of the boy’s sorrow, yet he could not but feel as if he, the elder son, had been unrightfully defrauded. The half-breed lad had known their common father so much better than he, the wholly white son. For some minutes after Blaise ceased speaking, Hugh sat silent, oppressed by conflicting thoughts and feelings. Then his mind turned to the present, practical aspect of the situation.

“It will not be an easy search,” he remarked. “Have you no clue to the spot where the furs are hidden?”

“None, except that it is a short way only from the place where the wrecked boat lies.”

“Where the boat lay when father left it,” commented Hugh thoughtfully. “It may have drifted far from there by now.”

“That is possible. I could not learn from him where the wreck happened, though I asked several times. The boat was driven on the rocks. That is all I know.”

“And his companion? Was he drowned?”

Blaise shook his head. “I know not. Our father said nothing of Black Thunder, but I think he must be dead, or our father would not have come alone.”

“How shall we set about the search?”

“We will go down along the shore,” Blaise replied, taking the lead as if by right, although he was the younger by two or three years. “We will look first for the wrecked bateau. When we have found that, we will make search for the cache of furs.”

Hugh’s thoughts turned to another part of his half-brother’s tale. “Tell me, Blaise,” he said suddenly, “what was it caused my father’s death, starvation, exhaustion, hardship? Or was he hurt when the boat was wrecked? You spoke of his blood-stained clothes.”

“It was not starvation and not cold,” the half-breed boy replied gravely. “He was hurt, sore hurt.” The lad cast a swift glance about him, at the still and silent woods shadowy with approaching night. Then he leaned towards Hugh and spoke so low the latter could scarcely catch the words. “Our father was sore hurt, but not in the wreck. How he ever lived to reach us I know not. The wound was in his side.”

“But how came he by a wound?” Hugh whispered, unconsciously imitating the other’s cautious manner.

Blaise shook his black head solemnly. “I know not how, but not in the storm or the wreck. The wound was a knife wound.”

“What?” cried Hugh, forgetting caution in his surprise. “Had he enemies who attacked him? Did someone murder him?”

Again Blaise shook his head. “It might have been in fair fight. Our father was ever quick with word and deed. The bull moose himself is not braver. Yet I think the blow was not a fair one. I think it was struck from behind. The knife entered here.” Blaise placed his hand on a spot a little to the left of the back-bone.

“A blow from behind it must have been. Could it have been his companion who struck him?”

“Black Thunder? No, for then Black Thunder would have carried away the furs. Our father would not have told us to go get them.”

“True,” Hugh replied, but after a moment of thought he added, “Yet the fellow may have attacked him, and father, though mortally wounded, may have slain him.”

A quick, fierce gleam shone in the younger boy’s bright eyes. “If he who struck was not killed by our father’s hand,” he said in a low, tense voice, “you and I are left to avenge our father.” It was plain that Christian schooling in Quebec had not rooted out from Little Caribou’s nature the savage’s craving for revenge. To tell the truth, at the thought of that cowardly blow, Hugh’s own feelings were nearly as fierce as those of his half-Indian brother.

Hugh slept on board the Otter that night and helped with the unloading next day. His duties over, he was free to go where he would. To Baptiste’s queries, he replied that he had seen his half-brother and had arranged to accompany him to the Grand Portage. Later he would come again to the Kaministikwia or return to the Sault by the southerly route. Having satisfied the simple fellow’s curiosity, Hugh went with him to visit the New Fort.

Baptiste had a great admiration for the Fort. Proudly he called Hugh’s attention to the strong wooden walls, flanked with bastions. He obtained permission to take his friend through the principal building and display to him the big dining hall. There, later in the year, at the time of the annual meeting, partners, agents and clerks would banquet together and discuss matters of the highest import to the fur trade. He also showed Hugh the living quarters of the permanent employees of the post, the powder house, the jail, the kilns and forges. When the Fort should be completed, with all its storehouses and workshops, it would be almost a village within walls. Outside the stockade was a shipyard and a tract of land cleared for a garden. Hugh, who had lived in the city of Montreal, was less impressed with the log structures, many of them still unfinished, than was the voyageur who had spent most of his days in the wilds. Nevertheless the lad wondered at the size and ambitiousness of this undertaking and accomplishment in the wilderness. Far removed from the civilization of eastern Canada, the trading post was forced to be a little city in itself, dependent upon the real cities for nothing it could possibly make or obtain from the surrounding country.

To tell the truth, however, Hugh found more of real interest and novelty without the walls than within. There, Baptiste took him through the camps of Indians, voyageurs and woodsmen or coureurs de bois, where bark lodges and tents and upturned canoes served as dwellings. In one of the wigwams Blaise was living, awaiting the time when he and his elder brother should start on their adventurous journey.

Already Blaise had provided himself with a good birch canoe, ribbed with cedar, and a few supplies, hulled corn, strips of smoked venison as hard and dry as wood, a lump of bear fat and a birch basket of maple sugar. He also had a blanket, a gun and ammunition, an iron kettle and a small axe. Hugh had been able to bring nothing with him but a blanket, his hunting knife and an extra shirt, but, as he had worked his passage, he still possessed a small sum of money. Now that he was no longer a member of the crew of the Otter, he had no place to sleep and wondered what he should do. Blaise solved the problem by taking him about a mile up-river to the post of the New Northwest or X Y Company, a much smaller and less pretentious place than the New Fort, and introducing him to the clerk in charge. Blaise had already explained that he and Hugh were going to get the elder Beaupré’s furs and would bring them back to the New Company’s post. So the clerk treated Hugh in a most friendly manner, invited him to share his own house, and even offered to give him credit for the gun, canoe paddle and other things he needed. Hugh, not knowing whether the search for the furs would be successful, preferred to pay cash.

From the X Y clerk the lad learned that his father, always proud and fiery of temper, had, the summer before, taken offence at one of the Old Company’s clerks. The outcome of the quarrel had been that Beaupré had entered into a secret agreement with the New Company, promising to bring his pelts to them. The clerk warned both boys not to let any of the Old Company’s men get wind of their undertaking. The rivalry between the two organizations was fierce and ruthless. Both went on the principle that “all is fair in love or war,” and the relations between them were very nearly those of war. If the Old Company learned of the hidden furs, they would either send men to seek the cache or would try to force the boys to bring the pelts to the New Fort. The X Y clerk even hinted that Jean Beaupré had probably been the victim of some of the Old Company’s men who had discovered that he was carrying his furs to the rival post. Hugh, during his winter at the Sault, had heard many tales of the wild deeds of the fur traders and had listened to the most bitter talk against the X Y or New Northwest company. Accordingly he was inclined to believe there might be some foundation for the agent’s suspicions. Blaise, however, took no heed of the man’s hints. When Hugh mentioned his belief that his father had been murdered because of his change of allegiance, the younger boy shrugged his shoulders, a habit caught from his French parent.

“That may be,” he replied, “but it is not in that direction I shall look for the murderer.” And that was the only comment he would make.

To avoid curiosity and to keep their departure secret if possible, the boys decided not to go down the north branch of the Kaministikwia past the New Fort, but upstream to the dividing point, then descend the lower or southern channel. Early the third morning after Hugh’s arrival, they set out from the New Northwest post. Up the river against the current they paddled between wooded shores veiled by the white, frosty mist. Without meeting another craft or seeing a lodge or tent or even the smoke of a fire, they passed the spot where the middle channel branched off, went on to the southern one, down that, aided by the current now, and out upon the fog-shrouded waters of the great bay. Hugh could not have found his way among islands and around points and reefs, but his half-brother had come this route less than two weeks before. With the retentive memory and excellent sense of direction of the Indian, he steered unhesitatingly around and among the dim shapes. When the sun, breaking through the fog, showed him the shore line clearly, he gave a little grunt of satisfaction. He had kept his course and was just where he had believed himself to be.

This feat of finding his way in the fog gave the elder brother some respect for the younger. Before the day was over, that respect had considerably increased. As the older boy was also the heavier, he had taken his place in the stern, kneeling on his folded blanket. Wielding a paddle was not a new exercise to Hugh. He thought that Blaise set too easy a pace, and, anxious to prove that he was no green hand, he quickened his own stroke. Blaise took the hint and timed his paddling to his brother’s. Hugh was sturdy, well knit and proud of his muscular strength. For a couple of hours he kept up the pace he had set. Then his stroke grew slower and he put less force into it. After a time Blaise suggested a few minutes’ rest. With the stern blade idle and the bow one dipped only now and then to keep the course, they floated for ten or fifteen minutes.

Refreshed by this brief respite and ashamed of tiring so soon, Hugh resumed work with a more vigorous stroke, but it was Blaise who set the pace now. In a clear, boyish voice, which gave evidence in only an occasional note of beginning to break and roughen, he started an old French song, learned from his father, and kept time with his paddle.

“Je n’ai pas trouvé personne

Que le rossignol chantant la belle rose,

La belle rose du rosier blanc!”

Roughly translated:

“Never yet have I found anyone

But the nightingale, to sing of the lovely rose,

The lovely rose of the white rose tree!”

At first Hugh, though his voice broke and quavered, attempted to join in, but singing took breath and strength. He soon fell silent, content to dip and raise his blade in time to the younger lad’s tune. An easy enough pace it seemed, but the half-breed boy kept it up hour after hour, with only brief periods of rest.

Hugh began to feel the strain sorely. His arms and back ached, his breath came wearily, and the lower part of his body was cramped and numb from his kneeling position. He had eaten breakfast at dawn and, as the sun climbed the sky and started down again, he began to wonder when and where his Indian brother intended to stop for the noon meal. Did Blaise purpose to travel all day without food, Hugh wondered. He opened his lips to ask, then, through pride, closed them again. Blaise, just fourteen, was nearly three years younger than Hugh. What Blaise could endure, the elder lad felt he must endure also. He did not intend to admit hunger or weariness, so long as his companion appeared untouched by either. With empty stomach and aching muscles, the white boy plied his paddle steadily and doggedly in time to the voyageur songs and the droning, monotonous Indian chants, the constantly repeated syllables of which had no meaning for him.

It was the weather that came to Hugh’s rescue at last. After the lifting of the chill, frosty, morning fog, the day was bright. The waters of Thunder Bay were smooth at first, then rippled by a light north breeze. As the day wore on, the breeze came up to a brisk blow. Partly protected by the islands and points of the irregular shore, the two lads kept on their way. The wind increased. It roughened every stretch of open water to waves that broke foaming on the beaches or dashed in spray against the gray-brown rocks. Paddling became more and more difficult. Blaise ceased his songs. As they rounded a low point edged with gravel and sand, and saw before them a stretch of green-blue water swept by the full force of the wind into white-tipped waves, the half-breed boy told Hugh to steer for the beach. A few moments later he gave his elder brother a quick order to cease paddling.

Realizing that Blaise wished to take the canoe in alone, Hugh, breathing a sigh of relief, laid down his paddle. The muscles of his back and shoulders were strained, it seemed to him, almost to the breaking point, and he felt that, in spite of his pride, he must soon have asked for rest. Without disturbing the balance of the wobbly craft, he tried to rub his cramped leg muscles. He feared that in trying to rise and step out, he might overturn the boat, to the mirth and disgust of his Indian brother.

With a few strong and skillful strokes, Blaise shot the canoe into the shallow water off the point. When the bow struck the sand, with a sharp command to Hugh, he rose and stepped out. As quickly as he could, Hugh got to his feet, and managed to step over the opposite side without stumbling or upsetting the canoe. Raising the light bark craft, the two carried it up the shelving shore, to the bushes that edged the woods, well beyond the reach of the waves.

The canoe carefully deposited in a safe spot, Hugh turned to Blaise. “Shall we be delayed long, do you think?” he asked.

Blaise gave his French shrug. “It may be that the wind will go down with the sun.”

“Then, if we are to stay here so long, a little food wouldn’t come amiss.”

The younger boy nodded and began to unlash the packages which, to distribute the weight evenly, were securely tied to two poles lying along the bottom of the canoe. Hugh sought dry wood, kindled it with sparks from his flint and steel, and soon had a small fire on the pebbles. From a tripod of sticks the iron kettle was swung over the blaze, and when the water boiled, Blaise put in corn, a little of the dried venison, which he had pounded to a powder on a flat stone, and a portion of fat. He had made no mention of hunger, but when the stew was ready, Hugh noticed that he ate heartily. Meanwhile the elder boy, tired and sore muscled, watched for some sign of weariness in his companion. If Blaise was weary he had too much Indian pride to admit the fact to his new-found white brother.

The open lake was now rich blue, flecked with foamy whitecaps, the air so clear that the deep color of the water formed a sharp cut line against the paler tint of the sky at the horizon. The May wind was bitterly cold, so the lads rigged a shelter with the poles of the canoe and a blanket. The ground was so hard the poles could not be driven in. Three or four inches down, it was either frozen or composed of solid rock. The boys were obliged to brace each pole with stones and boulders. The blanket, stretched between the supports, kept off the worst of the wind, and between the screen and the fire, the two rested in comfort. Hugh soon fell asleep, and when he woke he was pleased to find that Blaise had dropped off also. Perhaps the latter was wearier than he had chosen to admit.

The wind did not go down with the sun, and the adventurers made camp for the night. Both blankets would be needed for bedding, so the screen was taken down and the canoe propped up on one side. Then a supply of wood was gathered and balsam branches cut for a bed. After a supper of corn porridge and maple sugar, the two turned in. Blaise went to sleep as soon as he was rolled in his blanket, but Hugh was wakeful. He lay there on his fragrant balsam bed in the shelter of the canoe, watching the flickering light of the camp fire and the stars coming out in the dark sky. Listening to the rushing of the wind in the trees and the waves breaking on the pebbles and thundering on a bit of rock shore near at hand, surrounded on every side by the strange wilderness of woods and waters, the boy could not sleep for a time. He kept thinking of his roving, half-wild father, and of the strange legacy he had left his sons. Twice Hugh rose to replenish the fire, when it began to die down, before he grew drowsy and drifted away into the land of dreams.

Hugh woke chilled and stiff, to find Blaise rekindling the fire. The morning was clear and the sun coming up across the water. Winds and waves had subsided enough to permit going on with the journey.

Cutting wood limbered Hugh’s sore muscles somewhat, and a hot breakfast cheered him, but the first few minutes of paddling were difficult and painful. With set teeth he persisted, and gradually the worst of the lameness wore off.

Skirting the shore of Lake Superior in a bark canoe requires no small amount of patience. Delays from unfavorable weather must be frequent and unavoidable. On the whole, Hugh and Blaise were lucky during the first part of their trip, and they reached the Pigeon River in good time. Rounding the long point to the south of the river mouth, they paddled to the north end of Wauswaugoning Bay.

Hugh was gaining experience and his paddling muscles were hardening. He would soon be able, he felt, to hold his own easily at any pace his half-brother set. So far Blaise had proved a good travelling companion, somewhat silent and grave to be sure, but dependable, patient and for the most part even tempered. His lack of talkativeness Hugh laid to his Indian blood, his gravity to his sorrow at the loss of the father he had known so much better than Hugh had known him. Blaise, the older boy decided, was, in spite of his Quebec training and many civilized ways, more Indian than French. Only now and then, in certain gestures and quick little ways, in an unexpected gleam of humor or sudden flash of anger, did the lad show his kinship with Jean Beaupré.

Satisfactory comrade though the half-breed boy seemed, Hugh was in no haste to admit Blaise to his friendship. Since first receiving his letter, Hugh had felt doubtful of this Indian brother, inclined to resent his very existence. Their relations from their first meeting had been entirely peaceful but somewhat cool and stiff. As yet, Hugh was obliged to admit to himself, he had no cause for complaint of his half-brother’s behavior, but he felt that the real test of their companionship was to come.

The search for the cache of pelts had not yet begun, but was to begin soon. It was into his wife’s lodge at Wauswaugoning Bay that Jean Beaupré had stumbled dying. Somewhere between Grand Portage Bay, which lies just to the west and south of Wauswaugoning, and the Fond du Lac at the mouth of the St. Louis River, the bateau must have been wrecked and the furs hidden.

The two boys landed on a bit of beach at the north end of the bay, hid the canoe among the alders, and set out on foot. Blaise fully expected to find his mother awaiting him, but the cleared spot among the trees was deserted. Of the camp nothing remained but the standing poles of a lodge, from which the bark covering had been stripped, and refuse and cast-off articles strewn upon the stony ground in the untidy manner in which the Indians and most of the white voyageurs left their camping places. With a little grunt, which might have meant either disappointment or disgust, Blaise looked about him. He noticed two willow wands lying crossed on the ground and pegged down with a crotched stick.

“She has gone that way,” said the boy, indicating the longest section of willow, pointing towards the northeast.

“If she travelled by canoe, it is strange we did not meet her,” Hugh remarked.

Blaise shrugged. “Who knows how long ago she went? The ashes are wet with rain. I cannot tell whether the fire burned two days ago or has been out many days. There is another message here.” He squatted down to study the shorter stick. At one end the bark had been peeled off and a cross mark cut into the wood. The marked end pointed towards a thick clump of spruces.

The boy rose and walked towards the group of trees, Hugh following curiously. Blaise pushed his way between the spruces, and, before Hugh could join him, came out again carrying a mooseskin bag. In the open space by the ashes of the fire, he untied the thong and dumped the contents. There was a smaller skin bag, partly full, a birch bark package and a bundle of clothing. Tossing aside the bundle, Blaise opened the small bag, thrust in his hand, then, with the one word “manomin,” passed the bag to Hugh. It was about half full of wild rice grains, very hard and dry. The bark package Blaise did not open. He merely sniffed at it and laid it down. Hugh, picking it up and smelling of it, recognized the unmistakable odor of smoked fish. The bundle, which the younger boy untied next, contained two deerskin shirts or tunics, two pairs of leggings of the same material and half a dozen pairs of moccasins. All were new and well made, the moccasins decorated with dyed porcupine quills, the breasts of the tunics with colored bead embroidery.

The lad’s face lighted with a look of pleasure, and he glanced at Hugh proudly. “They are my mother’s work,” he said, “made of the best skins, well made. Now we have strong new clothes for our journey.”

“We?” replied Hugh questioningly.

“Truly. There are two suits and six pairs of moccasins. Look.” He held up one of the shirts. “This she made larger than the other. She knows you are the elder and must be the larger.” He handed the shirt to Hugh, following it with a pair of the leggings. Looking over the moccasins, he selected the larger ones and gave them also to his white brother. “They are better to wear in a canoe than boots,” he said.

For a moment Hugh was silent with embarrassment. He was touched by the generosity of the Indian woman, who had put as much time and care on these clothes for her unknown stepson as upon those for her own boy. He flushed, however, at the thought of accepting anything from the squaw who had taken his mother’s place in his father’s life. Yet to decline the gift would be to offer a deadly insult not only to the Indian woman but to her son as well.

“I am obliged to your mother,” Hugh stammered. “It was—kind of her.”

Blaise made no other reply than a nod. He appeared pleased with the appearance and quality of the clothes, but took it as a matter of course that his mother should make them for Hugh as well as for himself.

“I wish she had left more food,” he said after a moment, “but at this time of the year food is scarce. That manomin is all that remained of the harvest of the autumn. We have eaten much of our food. We must fish when we can.”

“Can’t we buy corn and pork from the traders at the Grand Portage?” Hugh inquired.

Blaise shook his head doubtfully. “We will try,” he said.

He put the food back in the mooseskin bag and hung it on a tree. Then he turned to Hugh and said softly and questioningly, “You wish to see where we laid him?”

Hugh nodded, a lump rising in his throat, and followed his brother. Beyond the clump of spruces, in a tiny clearing, was Jean Beaupré’s grave. Hugh was surprised and horrified to see that it was, in appearance, an Indian grave. Poles had been stuck in the ground on either side, bent over and covered with birch bark. The boy’s face flushed with indignation.

“Why,” he demanded, “did you do that?” He pointed to the miniature lodge.

Blaise looked puzzled. “It is the Ojibwa custom.”

“Father was not an Ojibwa. He was a white man and should have been buried like a white man and a Christian,” Hugh burst out.