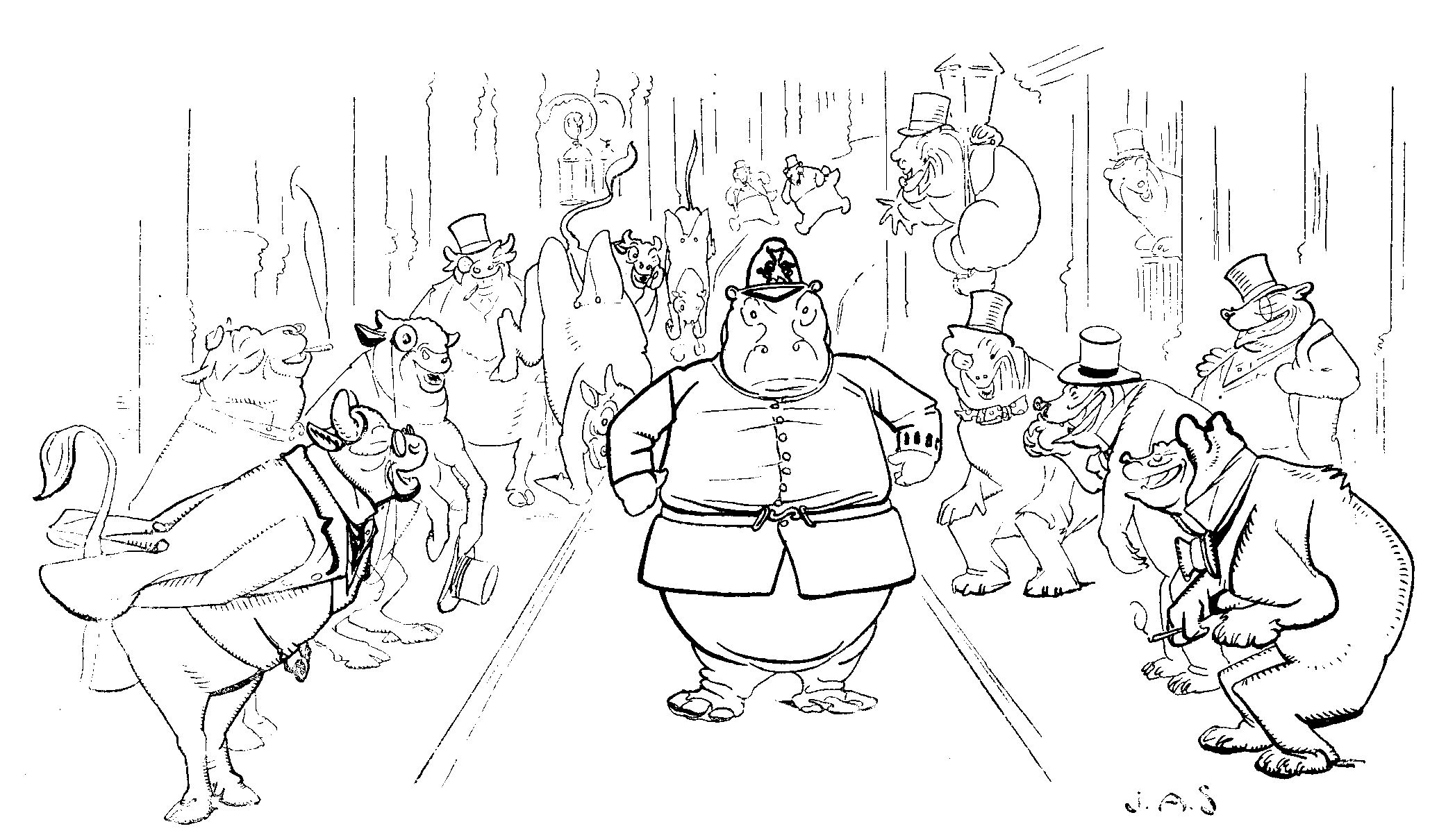

"ANIMAL SPIRITS."

No. IX.—Awkward position of Hippoliceman among the wild Bulls and Bears in Throgmorton Street.

(Vide Papers, March 22.)

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

VOL. 108.

March 30, 1895.

No. IX.—Awkward position of Hippoliceman among the wild Bulls and Bears in Throgmorton Street.

(Vide Papers, March 22.)

[Mr. Rider Haggard has become the accepted Conservative candidate for a Norfolk constituency. The following is understood to be an advance copy of his Address.]

Intelligent electors, may I venture to present

Myself as an aspirant for a seat in Parliament?

The views of those opponents who despise a novelist,

Are but the foggy arguments of People of the Mist!

No writer, I assure you, can produce a better claim,

A greater versatility, a more substantial fame;

My candidature, though opposed by all the yellow gang,

Has won the hearty sympathy of Mr. Andrew Lang.

And if what my opinions are you'd really like to know,

They're issued at a modest price by Longmans, Green, & Co.;

The Eight Hours Bill, for instance, I'm prepared to speak upon

From a practical acquaintance with the Mines of Solomon.

Whatever my intentions as to Woman's Rights may be,

I yield to none in honouring the great immortal She;

While, as to foreign policy, though Blue Books make you yawn,

You'll find the subject treated most attractively in Dawn.

When I am placed in Parliament, I'll speak with fluent skill,

And show (like Mr. Meeson) I've a most effective will;

And if there is a special point for which I mean to fight,

It is for legislation to protect my copyright.

If chance debate to matters in South Africa should tend,

My anecdotes will cause the Speaker's wig to stand on end;

And if an opportunity occurs, I'll rouse the lot

By perorating finely in impassioned Hottentot!

So, Gentlemen, I beg you, let my arguments prevail,

Shame would it be if such a cause through apathy should fail,

Shame on the false elector who his honest duty shirks!

Believe me, Yours.

Suggested Revival of an Old Form of Punishment for Future Obstrutionist Speculators in Throgmortonian Kaffir Land.—"Put 'em in the Stocks."

Last week the Court Theatre was advertised as a "Company, Limited." The cast in the bill was given as Chairman, Arthur W. Pinero; First Director, Sir Arthur Sullivan (with a song?); Second Director, Herbert Bennett (Director also of Harrod's Stores, Limited, the success of which establishment has been so great as to now out-Harrod Harrod); and then Arthur Chudleigh (who was jointly lessee at one time with Mrs. John Wood), as Director and Acting Manager. The Solicitor is down as Arthur B. Chubb ("little fish are sweet"), and the Secretary is Mr. A. (presumably Arthur?) S. Dunn. Most appropriate this name to finish with; "and now my story's Dunn." Fortunate omen, too, that there are two "n's" in Dunn, which otherwise is a word associated with a Court not quite so cheerful as the Court Theatre.

But the curious note about it is the preponderance of "Arthurs." Arthur Pinero, Arthur Sullivan, Arthur Chudleigh, Arthur Chubb, and Arthur (?) Dunn. If they have power to add to their number, why not take in Arthur Jones, Arthur Lloyd, and Arthur Roberts? That would make the Dramatic Arthurs and the Musical Arthurs about equal.

Matilda Charlotte Wood is mentioned as having had an agreement with one of the Arthurs yclept Chudleigh, and probably also a disagreement too, as their once highly prosperous joint management came to an end. But now "she will return," at least, everyone hopes so, as, after her capital performance of the Sporting Duchess at Drury Lane, she has shown us that she is as fresh and as great an attraction as ever. Some of the Arthurs will write for her, one Arthur will compose for her, two Arthurs will act and sing with her, and Arthur, the managing director, will direct and manage her. May every success attend the venture! But how about authors and composers offering their work to so professional a board of directors? Doesn't Sir Fretful Plagiary's objection to sending his play in to the manager of Drury Lane, namely, that "he writes himself." hold good nowadays? Hum. A difficulty, most decidedly; still, not absolutely insuperable.

Over-enthusiastic Person (speaking confidentially of his absent Friend to the young Lady to whom absent friend is going to propose). Everybody speaks in his praise. He is an exceptionally good man.

Sharp Young Lady. Ah, then he is "too good to be true." I shall refuse him!

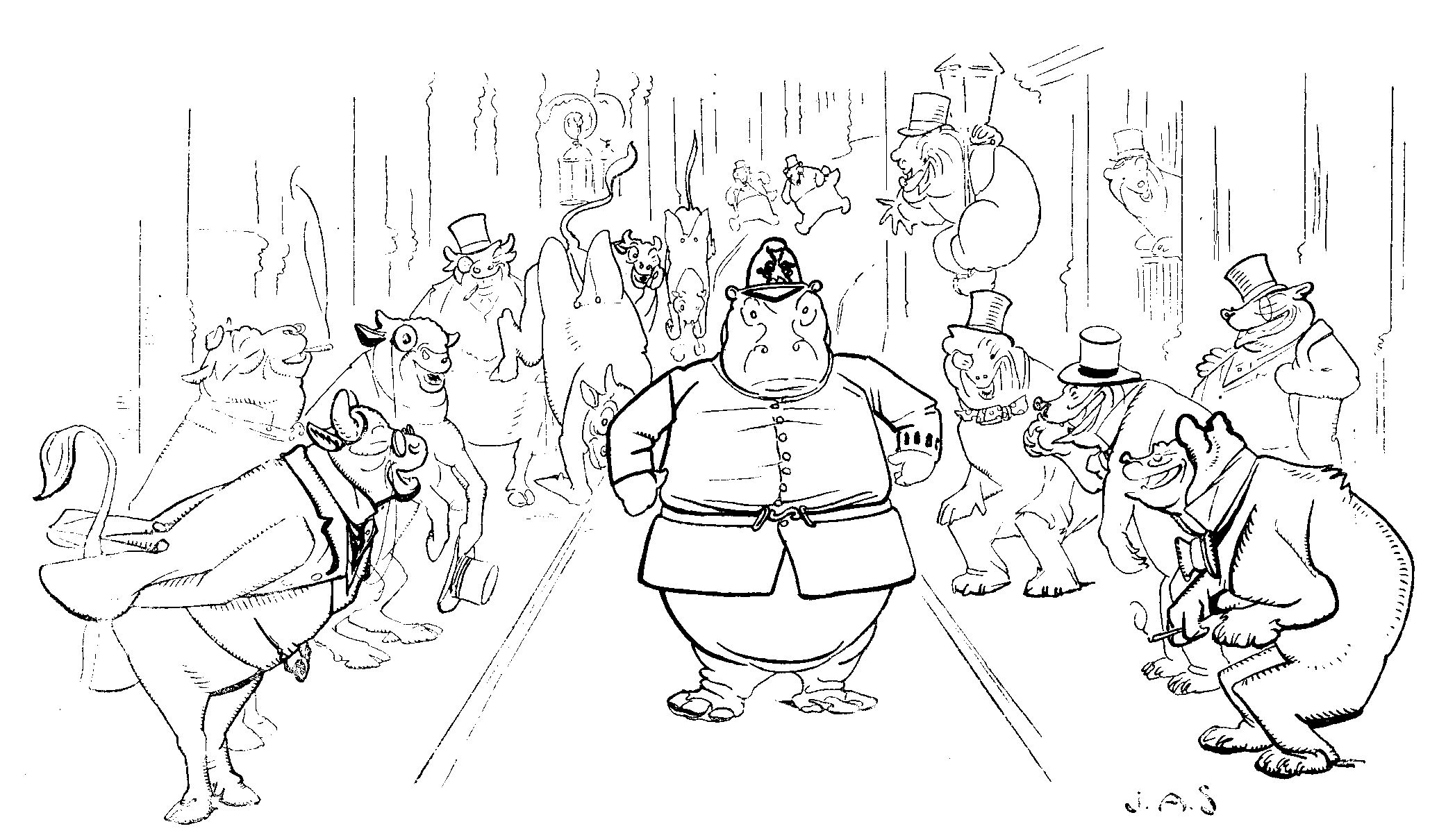

H.R.H. The Duke, accompanied by Drummer-boy Herbert Gladstone, leads the Sunday Park Band.

"The Duke of Cambridge takes the liveliest personal interest in the proposal made by Mr. John Aird, and supported by Mr. Herbert Gladstone, First Commissioner of Works, that military bands should perform in the Royal Parks on suitable occasions during the season."—Daily Telegraph, March 20.

Young Splinter (driving Nervous Old Party to Covert). "Yes, I love a Bargain in Horseflesh! Now, if you believe me, I picked this little Beggar up the other day for a mere Song. Bolted with a Trap—kicked everything to smash. Bid the Fellow a Tenner for her, and there she is!" [Old Party begins to feel that "'E don' know where 'e are," or will be presently.

A Song for a Summer Day, 1895.

(A Very Long Way after Dryden.)

["Mr. Herbert Gladstone, in reply to Mr. Aird, said he was glad to tell the hon. gentleman that he had been informed by his Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge that arrangements were being made for a military band to play in Hyde Park on certain days in summer."—Parliamentary Report.]

I.

In harmony, in public harmony,

This bit of pleasant news began.

St. Stephen's underneath a heap

Of burning questions lay.

When Herbert raised his head

His tuneful voice was heard on high,

And this is what it said:

That Great George Ranger could descry

A chance of making a big leap

To pop-u-lar-i-ty.

That Music's power should have full summer sway,

And the bands begin to play!

With harmony, with general harmony,

Around the information ran

That harmony, sweet harmony,

Should stay mere rumpus with its rataplan,

And make Hyde Park a pleasant place to Man!

II.

What passion cannot Music raise and quell?

When Herbert thumps the side-drum well

The listening nursemaids well may stand around,

A-wondering at that curly swell,

A-worshipping the rattling sound.

Less than a dook they think can hardly dwell

In that drum major's toffy togs.

He startles even the stray dogs!

What passion cannot Music raise and quell?

III.

The brass band's loud clangour

The populace charms,

The kettledrum-banger

The baby alarms.

At the double, double, double beat

Of young Gladstone's drum

The Socialist spouters from back street and slum

Cry, "Hark! our foes come!

Way oh! We'ad better retreat!"

IV.

The shrill and sprightly flute

Startles the seculurist spouts and shovers.

The crowds of music-lovers

Flock to its sound and leave tub-thumpers mute.

V.

Dark Anarchists proclaim

Their jealous pangs and desperation,

Fury, frantic indignation,

Depths of spite and heights of passion.

Music mars their little game.

VI.

Yes, Music's art can teach

Better than savage ungrammatic speech.

Young Herbert let us praise,

"The dear Dook" let us love.

The weary wayfarer, the wan-faced slummer,

Beneath the spell of Music and the Drummer,

Feel rataplans and rubadubs to raise

Their souls sour spleen above.

VII.

"Orpheus could lead the savage race,

And trees uprooted left their place,

Sequacious of the lyre."—

Precisely, Glorious John! Yet 'twere no lark

To see the trees cavorting round the Park.

No! Our Cecilia's aim is even higher.

To soothe the savage (Socialistic) breast,

Set Atheist and Anarchist at rest,

And to abate the spouting-Stiggins pest

Young Herbert and grey George may well aspire.

The "Milingtary Dook"'s permission's given

That the Park-Public's breast, be-jawed and beered,

May by the power of harmony be cheered,

And lifted nearer heaven!

Grand Chorus.

(By a Grateful Crowd.)

"This 'ere's the larkiest of lays!

Things do begin to move!

'Erbert and Georgy let us praise,

And all the powers above.

We've spent a reglar pleasant 'our

Music like this the Mob devour.

Yah! Anerchy is all my heye.

That cornet tootles scrumptiously.

Go it, young Gladsting! Don't say die

Dear Dook, but 'ave another try.

'Armony makes disorder fly

And Music tunes hus to the sky!

Mr. Pinero's new play at the Garrick Theatre is a series of scenes in dialogue with only one "situation," which comes at the end of the third act, and was evidently intended to be utterly unconventional, dreadfully daring, and thrillingly effective. "Unconventional?" Yes. "Daring?" Certainly; for to burn a bible might have raised a storm of sibilation. But why dare so much to effect so little? For at the reading, or during rehearsal, there must have been very considerable hesitation felt by everybody, author included, as to the fate of this risky situation—this "momentum unde pendet"—and for which nothing, either in the character or in the previous history of the heroine, has prepared us. Her earliest years have been passed in squalor; she has made a miserable marriage; then she has become a Socialist ranter, and hopes to achieve a triumph as a Socialist demagogue. Like Maypole Hugh in Barnaby Rudge she would go about the world shrieking "No property! No property!" and when, in a weak moment, she consents to temporarily drop her "mission," she goes to another extreme and comes out in an evening dress—I might say almost comes out of an evening dress, so egregiously décolleté is it—to please the peculiar and, apparently, low taste of her lover, who is a married man,—"which well she knows it," as Mrs. Gamp observes,—but with whom she is living, and with whom, like Grant Allen's The Woman who did (a lady whom in many respects Mr. Pinero's heroine closely resembles), and who came to grief in doing it, she intends to continue living. This man, her paramour, she trusts will be her partner in the socialistic regeneration of the human race. At the close of the third act Mrs. Ebbsmith, being such as the author of her being has made her, is presented with a bible, and, in a fit of ungovernable fury, she pitches it into the stove "with all her might and main"; and then it suddenly occurs to her that she has committed some terrible crime (more probably it occurred to the author that he had committed the unpardonable sin of offending his audience)—and so she shoots out her arm into a nice, cool-looking stove (suggestive of no sort of danger to her or the book), and drags out the pocket volume apparently quite as uninjured as is her own hand at the moment, though this is subsequently carefully bound up with a white handkerchief in the last act. Well—that's all. There is the situation. The Key-note-orious Mrs. Ebbsmith is supposed to repent of her sins against society; and off she goes to become the companion of the unmarried parson and of the lively widow his sister. What the result of this arrangement will be is pretty clear. The Key-note-orious One will soon be the parson's bride; but "that is another story."

To carry out this drama of inaction, as it is schemed, should occupy eight persons something under two hours; but it takes thirteen persons three hours to carry it along. Five of these dramatis personæ are superfluous; and much time is wasted on dialogues in Italian and French that could be "faked up" from any conversation-book in several languages, and evidently only lugged in under the mistaken impression that thereby a touch of "local colour" is obtained.

As it is the audience wearies of the long speeches, and there is nothing in the action that can rouse them as there was in The Second Mrs. Tanqueray, a play that Mr. Pinero has not yet equalled, much less surpassed.

But what is a real pleasure, and what will attract all lovers of good acting, is, first of all, Mr. Forbes Robertson's admirable impersonation of the difficult, unsympathetic rôle of a despicably selfish, self-conceited, cowardly prig; and, secondly, to a certain extent, the rendering of the heroine by Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who, however, does not come within measurable distance of her former self as Mrs. Tanqueray—her "great stove scene" being about the weakest point in her performance. But there cannot be a divided opinion as to the perfect part given to Mr. John Hare, and as to the absolutely perfect manner in which it is played by this consummate artist in character. All the scenes in which he appears are admirably conceived by the author, and as admirably interpreted by the actor.

Mr. Hare's performance of the Duke of St. Olpherts is a real gem, ranking among the very best things he has ever done, and I may even add "going one better." It is on his acting, and on the acting of the scenes in which he appears, that the ultimate popularity of the piece must depend. The theatrical stove-cum-book situation may tell with some audiences better than with others, but it is not an absolute certainty; while every scene in which the Duke of St. Olpherts takes part, as long as this character is played by Mr. Hare, is in itself an absolute isolated triumph. Mr. Aubrey Smith, as the modern young English moustached parson, en voyage, with his pipe, and bible in his pocket (is he a colporteur of some Biblical Society, with a percentage on the sale? otherwise the book is an awkward size to carry about, especially if he has also a Murray with him), is very true to life, at all events in manner and appearance; and Miss Jeffreys, as his sister, who looks just as if she had walked out of a fashion-plate in The Gentlewoman, or some lady's journal, plays discreetly and with considerable self-repression. Of course it will remain one of the notable pieces of the year; but what will keep it green in the memory of playgoers is not the story, nor its heroine, nor its hero, but the captivating impersonation of the Duke of St. Olpherts by Mr. John Hare.

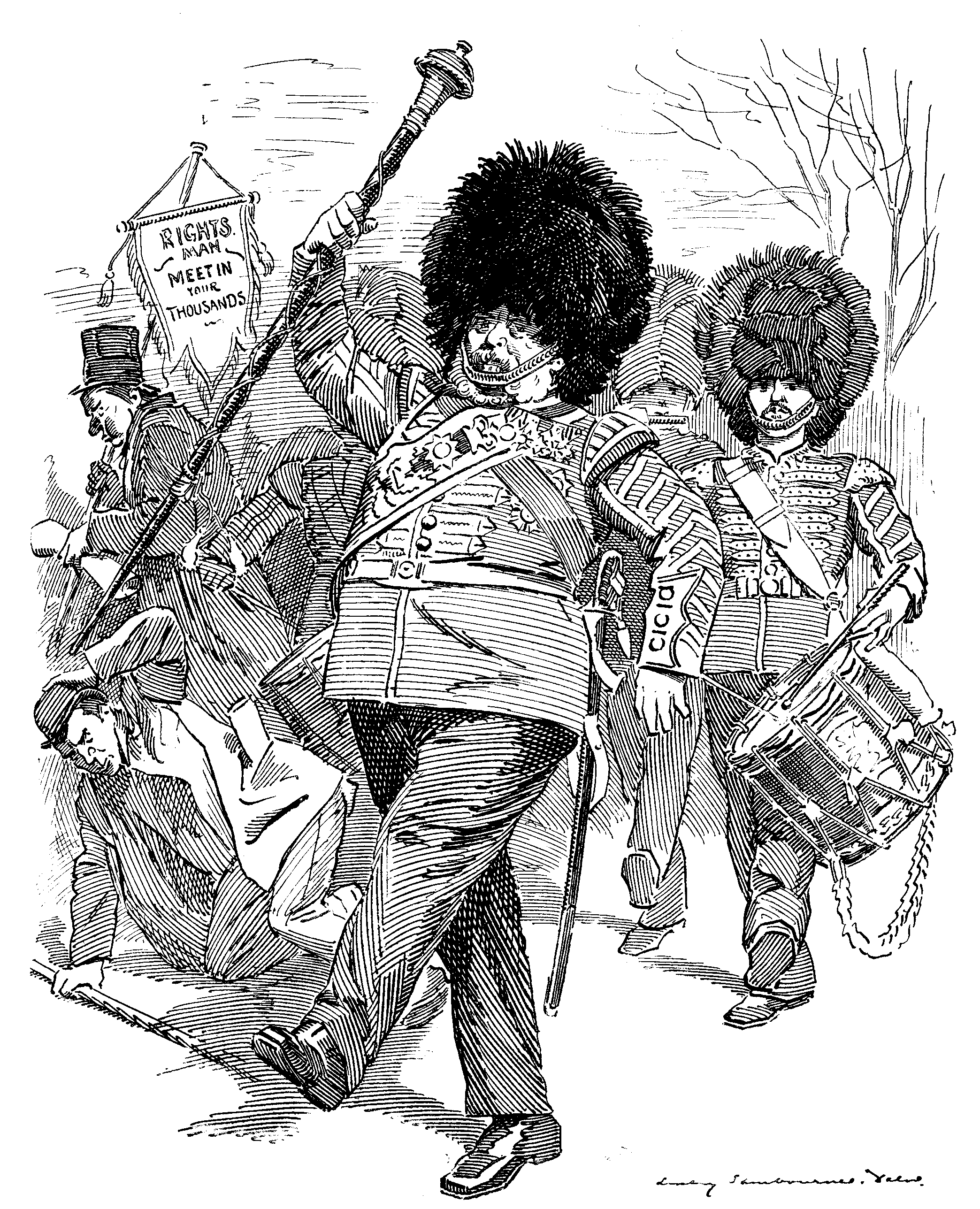

Scene—Bar of a Railway Refreshment Room.

Barmaid. "Tea, Sir?"

Mr. Boosey. "Tea!!! ME!!!!"

(By One who has Played it.)

Assume that I am living in Yokohama Gardens (before the pleasant change from winter to spring), and that I am conscious of the near approach of the North Pole. The fires in the grates seem to be lukewarm, and even the coals are frozen. My servants have told me that the milk had to be melted before it could adorn the breakfast-table; and as for the butter, it is as hard as marble. There is only one thing to do, to send for that worthy creature Mr. Lopside, an individual "who can turn his hand to anything."

"Well Sir," Mr. Lopside arrives and observes after a few moments spent in careful consideration of the subject from various points of view, "of course you feel the cold because there is five-and-twenty degrees of frost just outside."

I admit that Mr. Lopside's opinion is reasonable; and call his attention to the fact that a newspaper which is lying on the floor some five yards from a closed door is violently agitated.

"I see Sir," says he promptly. "If you will wait a moment I will tell you more about it."

He takes off his coat, throws down a bag of tools (his chronic companion), and lies flat on the floor. Then he places his right ear to the ground and listens intently, pointing the while to the newspaper that has now ceased to suffer from agitation.

"There you are, Sir!" he exclaims triumphantly. "There's a draught there. I could feel it distinctly."

He rises from the ground, reassumes his overcoat, and once more possesses himself of his bag of useful instruments.

"Well, what shall I do?" I ask.

"Well, you see Sir, it's not for the likes of me to advise gentry folk like you. I wouldn't think of presuming upon such a liberty."

"Not at all, Mr. Lopside," I explain with some anxiety.

"Then Sir—mind you, if it's not taking too much of a liberty—I would, having draughts, get rid of them. And you have draughts about, now haven't you?"

I hasten to assure him that I am convinced that my house is a perfect nest of draughts.

"Don't you be too sure until I have tested them," advises Mr. Lopside.

Then the ingenious creature again divests himself of his overcoat and workman's bag and commences his labours. He visits every door in the house and tries it. He assumes all sorts of attitudes. Now he appears like Jessie Brown at Lucknow listening to the distant slogan of the coming Highlanders. Now like a colleague of Guy Fawkes noting the tread of Lord Monteagle on the road to the gunpowder cellar beneath the Houses of Parliament. His attitudes, if not exactly graceful, are full of character.

"There are draughts everywhere," says Mr. Lopside, having come to the end of his investigations.

"And what shall I do?" I ask for the second time. Again my worthy inspector spends a few minutes in self-communing.

"It's not for the likes of a poor man like me, Sir, to give advice; but if I were you, Sir, I would say antiplutocratic tubing."

"What is antiplutocratic tubing?"

"Well, Sir, it's as good a thing as you can have, under all the circumstances. But don't have antiplutocratic tubing because I say so. I may be wrong, Sir."

"No, no, Mr. Lopside," I reply, in a tone of encouragement. "I am sure you are right. Do you think you could get me some antiplutocratic tubing, and put it up for me?"

"Why, of course I could, Sir!" returns my worthy helper, in the tone of a more than usually benevolent Father Christmas. Then he seems to lose heart and become despondent. "But there, Sir, it's not for the likes of me to say anything."

However, I persuade Mr. Lopside to take a more cheerful view of his position, and to undertake the job.

For the next three hours there is much hammering in all parts of the house. My neighbours must imagine that I have taken violently to spiritual manifestations. Wherever I wander I find my worthy assistant hard at work covering the borders of the doors with a material that looks like elongated eels in a condition of mummification—if I may be permitted to use such an expression. Now he is standing on a ledge level with the hall lamp; now he is reclining sideways beside an entrance-protecting rug; now he is hanging by the bannisters midway between two landings. The day grows apace. It is soon afternoon, and rapidly becomes night. When the lights are beginning to appear in the streets without, Mr. Lopside has done. My house is rescued from the draughts.

"You won't be troubled much more, Sir," says he, as he glances contemptuously at a door embedded in antiplutocratic tubing. "Keep those shut and the draughts won't get near you—at least so I think, although I may be wrong. Thank you, Sir. Quite correct. Good evening."

And he leaves me, muffled up in his overcoat, and still clinging to his basket, with its burden of saws, hammers, chisels, and nails of various dimensions. I enter the dining-room with an air of satisfaction as I hear his echoing footsteps on the pavement without, and attempt to close the door. It will do almost everything, but it won't shut. I give up the dining-room, and enter my study. Again, I try to close the door. But no; it has caught the infection of its neighbour and also declines to close. I try the doors of the drawing-room, bedroom, and the dressing-room. But no, my efforts are in vain. None of them will close. The wind howls, and the draughts rush in with redoubled fury. They triumph meanly in my despair.

There is only one thing to do, and I determine to do it. I must send for Mr. Lopside to take away as soon as possible his antiplutocratic tubing. After all he was right when he had those, alas! unheeded misgivings. He said "he might be wrong"—and was!

"I'm so sorry you've had to come and Dine with us without your Husband, Lizzy. I suppose the real truth is that, being Lent, he's doing Penance by dining at home!"

"Oh, no! I assure you! He thinks it a Penance to dine out!"

Resentful Ratepayer loquitur:—

"Demand and Supply!" So economists cry,

And one, they assure us, must balance the other.

I fancy their doctrines are just all my eye,

But then I'm a victim of bad times and bother.

At least, friend Aquarius, you'll understand

That Jack Frost and you have between you upset me.

You are down on me—ah! like a shot—with Demand,

But as to Supply—ah! that's just where you get me.

Water? You frosty old fraud, not a drop,

Save what I have purchased from urchins half frozen,

I've had for six weeks for my house and my shop,

And they tell me the six weeks may swell to a dozen!

Call that Water-Supply, Mister Mulberry Nose?

Why, your oozy old eyelids seem winking in mockery,

My cisterns are empty, my pipes frozen close,

I've nothing for washing my hands, clothes or crockery.

As to flushing my drain-pipes, or sinks, why you know,

I might as well trust the Sahara for sluicing.

A bath? Yes, at tuppence a pailful or so.

Good gracious! we grudge every tumbler we're using.

Your stand-pipes and tanks compensate for such pranks?

Get out! You are playing it low down, Aquarius.

Be grateful for mercies so small, Sir? No thanks!

My wrongs at your hands have been many and various.

But these last six weeks, Sir, are just the last straw

That break the strong back of the rate-paying camel,

I do not quite know what's the state of the law,

But if yours is all freedom, and mine is all trammel,

If yours is Demand, and mine is not Supply,

As 'twould seem by the look of that precious rate-paper,

Aquarius, old boy, I have plans in my eye

For checking your pretty monopolist caper.

Pay up, and look pleasant? Ah yes, that's my rule

For every impost, from Poor Rate to Income.

But paying for what you don't get fits a fool,

Besides, you old Grampus-Grab, whence will the tin come?

Supply discontinued? Aquarius, that threat,

Is losing its terrors. I don't care a penny,

'Twon't frighten me now into payment, you bet,

When for the last six weeks I haven't had any.

Whose fault? Well, we'll see. But at least you'll agree

When Supply's undertaken, and paid, in advance, for,

A man expects something for his L. S. D.

Then what have you led me this doose of a dance for?

That question, old Snorter, demands a prompt answer,

And Taurus expects it of you, my Aquarius,

Or else, Sir, by Gemini, I shall turn Cancer,

And then the monopolists mayn't look hilarious.

How do the Water Rates come to my door?

'Twould furnish a subject for some brand-new Southey.

Your dunning Demand Notes are always a bore,

But when one is grubby, half frozen and drouthy,

When cisterns are empty and sinks are unflushed,

And staircases sloppy, and queer smells abounding,

To be by an useless Aquarius rushed

For "immediate payment" is—well, it's astounding.

How will the water come down through the floor

When mains are unfrozen and pipes are all "busting"?

Why spurting and squirting, with rush and with roar,

The wall-papers staining, the fire-irons rusting,

And rushing, and gushing, and flashing and splashing,

And making a sort of Aix douche of the bedroom,

And comfort destroying, and every hope dashing,

And leaving one scarce a square yard of dry head-room.

'Twill leak, spirt and trickle, and, oh such a pickle

Will make of my dwelling, from garret to basement,

Well, that's after thaw. But, by Jove, it does tickle

My fancy, and fill me with angry amazement,

To see you mere standing ice-cool, and demanding

Prompt payment—for what? Why, long waterless worry!

Aquarius, we must have a fresh understanding;

Till then—"Call again!" and don't be in a hurry!

Motto for Stockbrokers.—A mine in the Randt is worth two in the Bush.

(She-Note Series.)

The two were seated in an untrammelled Bohemian sort of way on the imperturbable expanse of the South Downs. Beneath them was a carpet of sheep-sorrel, its orbicular perianth being slightly depressed by their healthy weight. In the distance they noticed thankfully the saucer-shaped combes of paludina limestone rising in pleasant strata to the rearing scarp of the Weald. Perugino Allan was the gentleman's name. He had only met Pseudonymia Bampton the day before, but already from mere community of literary instincts they were life-long friends. She had reached the trysting-place first. All true modest women do this.

"Pseudonymia!" said Perugino, blushing easily to his finger-tips.

"Perugino!" said Pseudonymia, blushing to hers. It was early, of course, for Christian names, but then the Terewth had made them Free-and-Easy.

"Perugino!" said Pseudonymia, bringing her eyes back from the infinite to rest without affectation on her simple Greek chiton, "I have often wanted to meet a real man who had written a book with a key to it on the back of the cover. Now tell me frankly some more beautiful things about our present loathsome system of chartered monogamy, so degrading to my sex. Talk straight on, please, pages at a time. Never mind about Probability. Terewth is stranger than Probability; and the Terewth, you know, shall make you Free!"

Perugino sank back into the spongy turf, leaning his cheek against an upright spike of summer furze of the genus Ulex Europæus. "Some men," he began, "ignoble souls, 'look about' them before they marry. Such are calculating egoists. Pure souls, of finer paste, are, so to speak, born married. Others hesitate and delay. The difficulties of teething, a paltry desire to be weaned before the wedding, reluctance to being married in long clothes, the terrors of croup during the honeymoon—these and other excuses, thinly veiling hidden depths of depravity, are employed to defer the divine moment. I have known men to reach the preposterously ripe age of one-and-twenty unwedded, protesting that they dare not risk their prospects at the Bar. These men can never mate like the birds, never be guide-posts to point humanity along the path of Terewth."

"But," interrupted Pseudonymia, rose-red to her quivering finger-tips with shame at the bare mention of marriage; "but I thought you disapproved of the debasing principle of wedlock."

"Do not interrupt," said Perugino, kindly; "I will come to that two or three pages later on. To be prudent, I was going to say, is to be vicious and cruel. Of course it is not given to all to be born married. But this natal defect one can easily remedy. I knew a young fellow who did. The indispensable complement crossed his path before it was too late. He was still at his preparatory school; he married the matron. True, there was disparity of age, but it was a step in the right direction; though the head-master, a man of common conventional ideas, gave the boy a severe rebuke.

"But to push on at once to contradictions. Marriage, I have said elsewhere, is a degrading system, nurtured under the purple hangings of the tents of iniquity. In my gospel Love, like Terewth, should be Free; ever moving on, moving on. Now, Italy is the home——"

"Ah!" cried Pseudonymia, "Italy! That reminds me of sunburnt Siena. What a wonderful Peruguinesque chapter that was in your book. Like a leaf torn out of the live heart of Baedeker!"

"Italy," continued Perugino doggedly, "is the home of backgrounds. I would like everyone to have a background—a past; the more pasts the better. Is not that a beautiful thought? Ever moving on to something different!"

"That has been the dream of my childhood," said Pseudonymia, her white Cordelia-like soul thrilled through and through with sacred convictions. A ripe gorse-pod burst in the basking sunlight. ("I never remember seeing sunlight bask before," she thought.) A bumble-bee said something inaudible. "But why," she added, "did you never give this pure sentiment to the world before? You who have written so many many books?"

"My child," replied the artist, "I was compelled to write down to the public taste. One must consider one's prospects. This, you will say, seems to clash with what I said before about calculating egoists. But profession and practice are ever divorced under our depraved system of civilisation. At last, having established myself, I rose superior to sordid avarice, and wrote for once solely to satisfy my own taste and conscience."

"A noble sacrifice!" said Pseudonymia, suppressing her dimples for the moment. "As the physically weaker vessel, I could only have done it under an assumed name. But tell me of one difficulty which you have so cleverly avoided in your book. This question of the family. Will not a confusion arise in another generation when nobody quite knows who and how many his or her half-brothers and half-sisters are?"

"Pseudonymia!" said Perugino, and his voice broke in two places, "I am pained. I had thought that you, so pure, so emancipate, would have had a soul above blithering detail. Besides, do you not see that in this way the whole world will eventually become one family? We may not live to see this Millennium, but future Fabians may. What we want is a protomartyr in the cause. Shelley promised well, but he ultimately reverted to legal wedlock. As for me, I have been deemed unworthy of the crown. I am, alas! happily married. But you, you are single; why should you not set to all your sister-slaves a high example of that martyrdom of which the glory, as well as the inconvenience, has been denied to me?"

"Ah, dear Perugino!" she cried, visibly affected for the third time to her finger-tips, "must it ever be so? Profession, as you say, divorced from practice? Must one more noble name be added to the list of those that shock the world so fearlessly with their books and live such despicably blameless lives? I myself, too, am misleading in print. You judged me by my pseudonymous publications to be single and unscrupulous. But you were wrong. I also am unequal to the weight of that crown. How can I be your martyr in the cause—I who these many years have worshipped the very dust on which my husband deigns to tread? Can you and I ever be forgiven for thus sinning against the light?"

Perugino rose to go, indignant, disillusioned. "Et tu, Pseudonymia?" he bitterly cried. (She had been at Girton and could follow the original.) "Then I give you up. You are, I grieve to think, a woman who won't do." And he made a she-note of it.

[A porpoise has been seen gambolling in the Thames at Putney.]

Such a sea on at the North Foreland! Glad to get out of it. Nice river coming down from somewhere. Must explore it.

Near some town. No end of oysters about. Oysters say it's Whitstable. Seem dreadfully depressed. Ask them if the late cold was too much for them? No, it's not that, they say, but injurious stories have been circulated about them by medical men. Been called "typhoidal." Nobody patronises them, and they've "lost their season in town." What do they mean?

Off Southend. Friendly sole advises me not to venture further. "Tempt not the Barking Outfall," he says, and adds that the "water at London will poison me, and I shall be made into boots." London! Always wanted to see it. What's the good of being called "a kind of gregarious whale" by the dictionaries if I avoid society?

Got past Barking safely! Who is it—Browning I think—wrote a poem about "Sludge, the Medium." Must have written it near Barking. Arrived off Wanstead Flats. See a respectable man on banks being chivied by a mob. Told (by a sprat) that "it's Mr. Hills, of the Thames Ironworks, who's been helping the unemployed." Now the unemployed seem helping him! Tower Bridge rather fine.

Westminster. Big building. Curious scent in air. Told it's the Houses of Parliament, and scent is eucalyptus, "because of the influenza." Curious word—wonder what it means.

Up at Putney. See University Boat-Race, if I can stay long enough. Feel sleepy. Must be the amount of bad water I've drunk. Knock up against an ice-floe. Two men in boat try to shoot me. They seem unemployed. Do they want to make me into soup for the poor? Not if I know it. Trundle back seawards. Meet a sea-gull. Says somebody tried to hook him from embankment. Says he "doesn't like London." Rather inclined to agree with him.

Back at sea. Know now what influenza means—because I've caught it! Awful pains in my hide! Must consult a leech.

Persistent self-analysis,

Perfected more and more,

The mirror to my spirit is,

Which it performs before.

For "progress" let reformers pine,

Let merchants toil for pelf—

The study of a soul like mine

Is certainly Itself!

For girls who at my shrine will burn

An incense delicate,

I'll lightly probe the problems stern

Of Love, and Life, and Fate;

And as their darkness I disperse,

I mark with interest

The diverse chords that girls diverse

Awaken in my breast.

Not having known a broken heart,

Nor any scathing pain,

I can afford, in life and art,

The pessimistic vein.

In many a literary gem,

Polished with care supreme,

Mildly, but firmly, I condemn

So poor a mundane scheme.

And yet, a modest competence

My pensive mood provides,

My sentiments—like specimens

On microscopic slides—

When I on woven paper fair,

In woven words illume,

I make a kind of subtle, rare,

And Esoteric Boom!

Police Charge against Excited Throgmortonian Jobber.—"He jobbed me in the eye."

Minister (who has exchanged pulpits—to Minister's Man). "Do you come back for Me after taking up the Books?"

Minister's Man. "Ou ay, Sir, I comes back for ye, and ye follows Me at a respectful distance!"

(By a disappointed Western Wire-puller.)

After a conflict such as this,

Some moralising's due;

And we in Bristol of the fight

Can take a "bird's-eye" view.

The poll we cannot truly call

The pleasantest of pills;

It's really rather sad our "won'ts"

Should come so near our "Wills."

Yet there's some comfort in the fact,

Some salve for spirits sore,

That Bristol nobly has not shrunk

From spilling of its "Gore."

A Balfourian Query.—"No possibility of any return to the shareholders," was, in the Pall Mall Gazette, the heading of a report of a meeting of the members of the "Liberator Company." What! no possibility of any return? Yes, surely, the return of Jabez. But even then—cui bono? or Cui Buenos Ayres? Who of the unfortunate losers would not far rather get back something than get back somebody, and that somebody Jabez.

The Early Bird.—Mr. Gosling, British Minister, has demanded an indemnity from the Nicaraguans of £15,000 for the expulsion of Mr. Hatch, British Vice-Consul at Bluefields. Gosling is no goose, that's clear. He offers the Nicaragamuffins a Hatch-way out of the difficulty of their own making.

"What so interests you?" asked the visitor. Replied the Baron, "Japhet in Search of a Father. I have not read it since my school days." "You find it old-fashioned, eh?" "Well," answered the Baron, "the first few chapters are certainly old-fashioned, and recall to my memory the italicised, punning style of Theodore Hook and of Tom and Jerry. But Captain Marryat soon gets away from this sort of thing; and when he has once fairly started his hero and his companion on their adventures, the interest of the story is never allowed to flag for a minute. I may add that I have not enjoyed any modern story of adventure so much as I have this one—always barring the romances of Rider Haggard, Stephenson, 'Q.,' Shorthouse, and Parker—as there is about it an old Georgian-era flavour, with its duels, its gambling-houses, its Tom-and-Jerry episodes, its occasional drop into melodrama, its varied characters of the period, its animal spirits and 'go,' that makes it—to me, at least—thoroughly fascinating." The illustrations, by H. M. Brock—which are specified as separately the property of Messrs. Macmillan—bring vividly before the reader the manners and customs of the time. "In these days of morbid yellow-jaundiced sensationalism, and of 'The New Woman,' I am delighted," quoth the Baron, "to recommend, and strongly, too, this first of the series of Captain Marryat's works, now in course of republication chez Macmillan." The visitor thanked his noble friend, and withdrew. Then the Baron finished the novel. "Good!" quoth the Baron, closing the book with regret at parting with a long-forgotten but now recovered friend; "but 'tis odd how one lives and learns. I do not remember having ever heard that Bottom the weaver had been christened 'William' by Shakspeare. Nor can I find that bully Bottom was so addressed by his friends. And if I have missed it, how came William to be the prénom of the Athenian weaver in the time of Theseus and Hippolyta! I should as soon expect to discover that Hercules was known to his companions as Henry Hercules. However, this by the way, and only à propos of a remark as to William Bottom, the weaver, made by Marryat. I anticipate with pleasure re-making the acquaintance of Jacob Faithful and Midshipman Easy."

The Banishment of Jessop Blythe, written by Joseph Hatton, and published by Hutchinson, belongs to the Yellow Book series, only that is as far as the cover is concerned, which is of a startlingly jaundiced tone and does not in the least represent the kindly author's views of life. The story is about the ropemakers by one who clearly "knows the ropes." This industry, as will be gathered from the present romance, is not confined to Ropemaker's Walk, E.C., but was for two centuries carried on by Troglodytes or Cave-dwellers in Derbyshire. The hero Blythe is turned out from the roping community as a thriftless drunkard, emigrates, is poor and wretched, but returns Blythe and gay, with a lot of money to find.... "But here," quoth the Baron, "I must pause, or the surprise will be heavily discounted, and the reader's pleasure spoilt. Thus far, no farther. 'Tolle; lege.'" So recommended the

Divine Williams knew the kind of unwholesome woman above mentioned. In Love's Labour's Lost he makes Biron say—

"A whitely wanton with a velvet brow,

With two pitch balls stuck in her face for eyes;

Ay, and, by heaven, one that will do the deed,

Though Argus were her eunuch and her guard."

Is not this the living picture of the woman who would, or could, but who shouldn't and oughtn't?

Choosing the Speaker.—A suggestion was made last week that the competitors for the Speakership should draw lots. Now, if it came to "drawing lots," all in the House and out of the House, having seen "lots" of Sir Frank Blookwood's drawing, would of course place him first. So the drawing lots plan was abandoned.

Our Minor Poet. "I believe I should enjoy my Holidays much more if I went Incognito."

Friend. "Travel under your Nom de Plume, Old Man!"

A Poem of Common Sense.

Dear Sir, I've read through your delectable lines—

Though the cap doesn't fit, I will wear it;

And hope (though I don't know your private designs)

You regret that such verses were e'er writ!

There's flirting and flirting, you don't seem to know,

Nor need a young woman be heartless,

Who thinks that, by having five strings to her bow,

The four she rejects will thus smart less.

Pray how can I help, if my features attract

And my sympathy wins each fond lover?

Alas, when they're conquered, I own 'tis the fact

That their weak points I sadly discover!

It may be, in spite of your captious alarm,

I shall yet enjoy bliss hymeneal;

If this is my aim, not to jilt, where's the harm

In my search for a husband ideal?

[A] See page 141

In "Dick Grain" all have lost a "fellow of infinite jest" and a friendly critic who scourged our pleasant vices with such genial criticism that everyone, hearing him, charitably applied the moral to his, or her, neighbour. With Mrs. German Reed, the Miss Priscilla Horton of the stage, and her son "Taff Reed," the old Gallery of Illustration Company comes to an end. Corney Grain successfully succeeded John Parry.

"C. G." Ci gît.

(A Topical Explanation.)

Your dark blue eyes are doubtless very sweet,

And I could hear without the least surprise

That connoisseurs declare it hard to beat

Your dark blue eyes.

How is it if so much of magic lies

In your two "orbs" I deem them incomplete?

Why with disdain—I'm going to poetise—

Do I your "heavenly windows" ever treat?

The explanation Saturday supplies.

I'm Cambridge. That's why I'm so loth to meet

Your dark blue eyes.

Note.—"Dark blue." In view of the coming Boat Race this may be taken as a prophecy, or tip.

Sir,—The following may be of service to your non-mathematical readers:—

Q. "The hands of a clock are between 2 and 3; and in ten minutes' time the minute hand will be as much in front of the hour hand as it is now behind it. What is the time?"

A. "Ask Policeman X."

The crass mediævalism of the Oxbridge don, I regret to say, failed to see this solution, and I am again coaching with old Drummer.—Yours theoretically and problematically,

Change of Name.—In consequence of recent events crowded into one place, the name of Throgmorton Street shall be changed into Throngmorton Street.

Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.

House of Commons, Monday, March 18.—Navy Estimates on again, with the First Lord listening patiently from otherwise empty Peers' Gallery, and Robertson making admirable play from Treasury Bench. Chivalrous soul of Cap'en Tommy Bowles moved to admit that, after all, there had been worse First Lords than Spencer, and more uncivil Lords than Robertson. Private Hanbury thinks this is weakness. If his colleague in charge of the Navy is to talk like that, he (the Private) will be expected, when the Army Estimates came on, to say something nice about Cawmell-Bannerman, to acknowledge Woodall's keen grip over the business of his department, and the courtesy with which he discharges his Ministerial duties.

Allan o'Gateshead on again with more "Rough Castings." Last time House in Committee on Navy Estimates he spread feeling of genuine alarm by denouncing the British boiler. "Who," he thundered, "is responsible for the engines of the Royal Navy? Where is the Hornet you trumpeted so loudly a year ago? Where," he continued, bending beetling brows on Civil Lord of the Admiralty, "are her boilers?"

"Bust," said Gorst, with guilty look. Not that he had had anything to do with the business, but because at this moment Allan o'Gateshead chanced to fix a pair of flaming eyes upon his shrinking figure, seated almost immediately opposite at end of Front Bench.

"Where is the Hornet now? Why, lying in Portsmouth Yard, with her boilers out of her, a useless hulk."

Allan is so big, so burly, wears so much hair, writes poetry, is understood to be in the boiler business himself, and, withal, addresses the Chairman with such terrific volume of voice, that a panic might have ensued only for John Penn. Penn head of great engineering firm of old standing and high repute. Understood to have engined fleet of five ships [pg 156] with which Drake made things hot for Spain along the coasts of Chili and Peru. However that be, Penn now made it hot for Allan o'Gateshead. Showed in quite business-like fashion that Allan's poetic fancy had run away with him. Convinced grateful Committee that British boiler, on which safety of State may be said to rest, is all right. A model speech, brief, pointed. A man with something to say, who straightway sits down when he's said it. As the poet (not Allan o' Gateshead) says,

He came as a boon and a blessing to men,

The modest, the lucid, clear-pointed J. Penn.

Business done.—Committee voted trifle over four millions as wages for Jack.

Tuesday.—Alderman Cotton, once Lord Mayor of London, a prominent and popular member of the Disraeli Parliament, left behind him the memory of one of those things we all would like to say if we could. In the long series of debates on resolutions moved from Front Opposition Bench challenging Jingo policy of the day, the Alderman interposed. "Sir," he said, "this is a solemn moment. Looking towards the East we perceive the crisis so imminent that it requires only a spark to let slip the dogs of war."

That was, and remains, inimitable. But to-night the MacGregor came very near its supreme excellence. Stirred to profoundest depths by demands upon Naval Expenditure. Popping up and down like piston in the engine-room of Clyde steamer; wrath grew as Mellor, failing to see him, called on other speakers. The MacGregor knew all about that; a reckless corrupt Government, afraid of hearing the voice of honest criticism, had suborned Chairman of Committees to prevent his speaking. But they didn't know the MacGregor. After something like two hours physical exercise in the way of jumping up and down he caught the Chairman's eye, and (in Parliamentary sense, of course) punched it. Then "passing from point to point," as he airily put it, he went for Robertson. Asked the appalled Civil Lord of the Admiralty what he supposed his constituents in Dundee would say when they read his speech, in which bang went millions as if they were saxpences? "What will the worthy citizens say, Mr. Mellor?" he repeated. "Why they will say, 'Ma conscience!'"

Never since Dominie Sampson made this remark has so much fervour and good Scotch accent been thrown in. "Where's the Chancellor of the Exchequer?" MacGregor presently asked, evidently eager for fresh blood.

"That has nothing to do with the question," said the Chairman, severely.

"Oh, hasn't it?" jeered the MacGregor. "I want to ask him what he has done with our money?"

Vision instantly conjured up before eyes of Committee of Squire of Malwood prowling about town with his pockets loaded with £4,132,500. voted to defray the charge for wages in the Navy, flinging the cash about like Jack ashore, making the most of his time before Local Veto became the law of the land.

It was later that the MacGregor came in unconscious competition with Alderman Cotton. Leaving the Navy for a moment he surveyed the Continent of Europe peopled with armed men. "Why!" he cried with comprehensive sweep of his arm, "these great armies are like fighting cocks. The least spark blows them up like magazines of powder."

Not quite so good it will be seen as the Alderman, but good enough for these degenerate days. Effect on Admiral Field so exciting that he was presently discovered chasing the Sage of Queen Anne's Gate all over House, desiring, as he said, to "pin him to his words."

Business done.—Supplementary Estimates voted.

Thursday.—Curious to note the coyness with which House approaches real business. To-day Welsh Disestablishment Bill comes on for Second Reading. Its passing this stage a foregone conclusion. The work of criticism, correction, possible re-moulding, will be done in Committee. Committee is the Providence that shapes the ends of Bills, rough hew them how we may in the draughtsman's hands or on the second reading. For all practical purposes second-reading debate might be concluded at to-night's sitting. It extended over seven clear hours. Given twenty minutes per speech, the maximum length for useful purposes, twenty-one members, more than the House cares to hear, might have spoken. The time saved, if necessary, added on to opportunity in Committee.

That, however, not the way we do business here. Disestablishment Bill a measure of first importance; must be treated accordingly. So after Asquith talks for an hour and a quarter, Hicks-Beach caps him by speech hour and half long, which nearly empties House. Afterwards a dreary night. Papers on subject read by Members, who rise alternately from either side. Few listen; newspaper reports cruelly curt; nevertheless, it's the thing to do, and will go on through at least four sittings. On last night men whom House want to hear will speak, as they might have spoken on first night. Then the division, and minor Members who have missed their chance will endeavour to work off their paper in Committee.

Business done.—Second reading Welsh Church Disestablishment Bill moved.

Friday.—Shall M.P.'s be paid out of public purse? Dividing to-night 176 say Yes, 158 stern patriots say No. George Curzon, fresh from the Pamirs and still later from a sick bed, leads opposition. Squire of Malwood is in favour of payment: darkly hints that when the time comes he will find the cash. This, though a little obscure, looks like business.

"I expect," said the Member for Sark, "we shall live to see the day when, on Friday afternoons, Palace Yard will be crowded with Members waiting to take their weekly money. Suppose they'll go the whole hog, give us what the navvies call a 'sub,' that is, let us draw in middle of the week something on account. Of course we shall have the full privilege of strikes. We'll 'go out' if we think our wages should be raised. Sure to be some blacklegs who will skulk in by central lobby and offer to do a day's talking on the old terms. But we'll have pickets and all that sort of thing. Sometimes we'll march in a body to Hyde Park, and Baron Ferdy will address us from a waggon on the rights of man and the iniquity of underpaying M.P.'s. I see a high old time coming. Shall put in early claim for a secretaryship. Always a good billet."

Business done.—Welsh Disestablishment Bill threw a gloom over morning sitting. George Osborne Morgan, supporting Bill, mentioned that in episcopal circles he is regarded as "a profligate"! There is, sometimes, a naughty look about him. But this is really going too far, even for a bishop.

Throughout the dialogues, there were words used to mimic accents of the speakers. Those words were retained as-is.

Errors in punctuations and inconsistent hyphenation were not corrected unless otherwise noted.

On page 149, "convined" was replaced with "convinced".

On page 149, "wont" was replaced with "won't".

On page 156, a period was added after "Tuesday".

On page 156, "covness" was replaced with "coyness".

On page 156, the period after "Sark" was replaced with a comma.