MEMLINC

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOR

MEMLINC

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOR

MASTERPIECES

IN COLOUR

EDITED BY - -

T. LEMAN HARE

HANS MEMLINC

(?) 1425-1494

| In the Same Series | |

| Artist. | Author. |

| VELAZQUEZ. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| REYNOLDS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| TURNER. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| ROMNEY. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| GREUZE. | Alys Eyre Macklin. |

| BOTTICELLI. | Henry B. Binns. |

| ROSSETTI. | Lucien Pissarro. |

| BELLINI. | George Hay. |

| FRA ANGELICO. | James Mason. |

| REMBRANDT. | Josef Israels. |

| LEIGHTON. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| RAPHAEL. | Paul G. Konody. |

| HOLMAN HUNT. | Mary E. Coleridge. |

| TITIAN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| MILLAIS. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| CARLO DOLCI. | George Hay. |

| GAINSBOROUGH. | Max Rothschild. |

| TINTORETTO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| LUINI. | James Mason. |

| FRANZ HALS. | Edgcumbe Staley. |

| VAN DYCK. | Percy M. Turner. |

| LEONARDO DA VINCI. | M. W. Brockwell. |

| RUBENS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| WHISTLER. | T. Martin Wood. |

| HOLBEIN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| BURNE-JONES. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| VIGÉE LE BRUN. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| CHARDIN. | Paul G. Konody. |

| FRAGONARD. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| MEMLINC. | W. H. J. & J. C. Weale. |

| CONSTABLE. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| In Preparation | |

| J. F. MILLET. | Percy M. Turner. |

| ALBERT DÜRER. | Herbert Furst. |

| RAEBURN. | James L. Caw. |

| BOUCHER. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| WATTEAU. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| MURILLO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| JOHN S. SARGENT, R.A. | T. Martin Wood. |

| And Others. | |

PLATE I.—OUR LADY AND CHILD.

(frontispiece)

Right panel of a diptych, painted in 1487 for Martin van Nieuwenhove. It is now in Saint John’s Hospital, Bruges.

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

IN SEMPITERNUM.

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

NEW YORK: FREDERICK A. STOKES CO.

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | Hans Memlinc | 11 |

| II. | Early Days and Training | 19 |

| III. | Earliest Works | 25 |

| IV. | Characteristics of His Early Works | 31 |

| V. | The Maturity of His Art | 36 |

| VI. | Masterpieces and Death | 53 |

| VII. | Effacement and Vindication of His Types | 66 |

| Plate | Page | |

| I. | Our Lady and Child, 1487 | Frontispiece |

| (Saint John’s Hospital, Bruges) | ||

| II. | Adoration of the Magi, 1479 | 14 |

| (Saint John’s Hospital, Bruges) | ||

| III. | Saints Christopher, Maurus, and Giles, 1484 | 24 |

| (Town Museum, Bruges) | ||

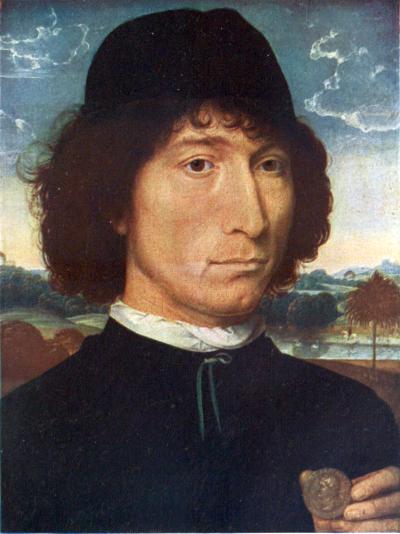

| IV. | Portrait of Nicholas di Forzore Spinelli, holding a medal | 34 |

| (Antwerp Museum) | ||

| V. | Portrait of Martin van Nieuwenhove, 1487 (companion to I.) | 40 |

| (Saint John’s Hospital, Bruges) | ||

| VI. | One Panel of the Shrine of Saint Ursula, 1489 | 50 |

| (Saint John’s Hospital, Bruges) | ||

| VII. | Portrait of an Old Lady | 60 |

| (Louvre, Paris) | ||

| VIII. | The Blessed Virgin and Child, with Saint George and the Donor | 70 |

| (National Gallery, London, No. 686) |

MEMLINC

ALREADY, before the advent of the House of Burgundy, Bruges had attained the height of her prosperity. From a small military outpost of civilisation, built to stay the advance of the ravaging Northmen, she had developed through four short centuries of a strenuous existence into one of the three leading cities of northern Europe. Born to battle, fighting had been her abiding lot with but scant intervals of peace, and as it had been under the rule of her long line of Flemish counts, so it continued with increased vehemence during the century of French domination that followed, the incessant warring of suzerain and vassal being further complicated and embittered by internecine strife with the rival town of Ghent. But she emerged from the ordeal with her vitality unsapped, her industrial capabilities unabated, her commercial supremacy unshaken. Her population had reached the high total of a hundred and fifty thousand; she overlorded an outport with a further thirty thousand inhabitants, a seaport, and a number of subordinate townships. The staple of wool was established at her centre, and she was the chief emporium of the cities of the Hanseatic League. Vessels from all quarters of the globe crowded her harbours, her basins, and canals, as many as one hundred and fifty being entered inwards in the twenty-four hours. Factories of merchants from seventeen kingdoms were settled there as agents, and twenty foreign consuls had palatial residences within her walls. Her industrial life was a marvel of organisation, where fifty-four incorporated associations or guilds with a membership of many thousands found constant employment.

The artistic temperament of the people had necessarily developed on the ruder lines, in the architectural embellishment of the city, the beautifying of its squares and streets, its churches and chapels, its municipal buildings and guild halls, its markets and canal embankments. “The squares,” we are told, “were adorned with fountains, its bridges with statues in bronze, the public buildings and many of the private houses with statuary and carved work, the beauty of which was heightened and brought out by polychrome and gilding; the windows were rich with storied glass, and the walls of the interiors adorned with paintings in distemper, or hung with gorgeous tapestry.” But of the highest forms of Art—of literature, of music, and of painting—there was slender token. The atmosphere in which the Flemings had pursued their destinies was little calculated to develop any other than the harder and more matter-of-fact side of their nature. True, here as elsewhere, and from the earliest period of her history the great monastic institutions which dotted the country had done much for the cultivation of Art, as the remains of wood sculpture, mural paintings, and numerous illuminated manuscripts amply testify. But no great school of painting had arisen or was even possible, so true is it that the development of the artistic instincts of the community require the contemplative repose and fostering inspiration of peace. In the truest sense of the term the Flemings were not a cultured artistic race: they had certainly a high standard of taste, but their artistic sense was appreciative rather than creative—even so, a notable advance for a nation of warriors and merchants.

PLATE II.—ADORATION OF THE MAGI.

This, one of the master’s finest works, was painted in 1479 for Brother John Floreins, Master of Saint John’s Hospital, Bruges, where it may be seen.

With the succession of the House of Burgundy to the French domination an entirely new era was ushered in. If the ambition of this new line of princes was unbounded, equally so was the success which attended its pursuit; their authority increased by leaps and bounds, and soon their court had become the wealthiest and most powerful in Europe. The high notions they entertained of their own dignity brooked no compeer in the pomp and glitter of their state. The display the guild and merchant princes and foreign representatives were capable of they should outdo: the splendour of their sovereignty should blur the brilliancy of mere civic ostentation. But while they revelled in the outward show of their supremacy, they viewed with jealous eye the great wealth and large measure of liberties enjoyed by their subjects. Their needs were great, the resources of the people commensurate; and in the alternate confiscation and resale of these liberties they found a remunerative source of revenue. But if the dukes were arrogant and unscrupulous, their subjects were no cravens, and civic shrewdness often proved more than a match for ducal craft. A fine sense of humour, however, suggested the policy of keeping these lusty burghers fully diverted the while they were not being bled or chastened: hence the constant recurrence of pacifications and triumphal entries, of regal processions and gorgeous tournaments, of public banquets and bewildering revels. It was an era of pomp and pageantry unparalleled in history, the success of which required the services of the highest talents of the day—the foremost artists to enhance its magnificence, the leading writers to chronicle its marvels.

It was Duke Philip III. who requisitioned the services of John van Eyck and showered on him bounty and patronage, and if his reign had proved as uneventful as it was the reverse, Philip’s name would still survive in the reflected glory of this prince of painting. The declining days of the great duke, stricken with imbecility, certainly offered no inducement to foreign artists on the lookout for court patronage. But with his death, on the 15th of June 1467, the entire prospect was changed. Charles the Bold now succeeded to the dukedom: his solemn entry into the Flemish capital took place on Palm Sunday of the year following—an occasion marked by brilliant jousts and tournaments—and his home-coming with his bride, Margaret of York, some three months later. These events, the marriage festivities notably, called for a great array of talent, and among the leading artists engaged in planning and executing the magnificent decorations indulged in we find Peter Coustain and John Hennequart, the ducal painters; James Daret and Philip Truffin of Tournay; Francis Stoc and Livin van Lathem of Brussels; Daniel De Rycke and Hugo Van der Goes of Ghent; Govart of Antwerp; and John Du Château of Ypres. And here Hans Memlinc enters on the scene, already then a master-painter and accomplished artist, but of whom no previous record, of whose lifework no earlier trace, has been discovered.

AS to where and when Memlinc was born, where he served his apprenticeship, and with whom he worked as a journeyman no documentary evidence has yet been discovered, and no one can confidently assert; but there exists a sufficiency of presumptive evidence to warrant certain conclusions with the help of which to construct a working biography. It appears probable that the family came from Memelynck, near Alkmaar, in north Holland, and settled at Deutichem, in Guelderland; and, on the strength of an entry copied from the diary kept by an ecclesiastical notary and clerk of the Chapter of Saint Donatian at Bruges during the years 1491 to 1498, that they subsequently removed to the ecclesiastical principality of Mainz. The subject of this monograph is likely to have been born, at some date between 1425 and 1435, either at some place within that principality, or at Deutichem previous to his parents’ removal. From our knowledge of the guild system which obtained in the middle ages throughout the north of Europe with but slight variation in the conditions of training and apprenticeship, and taking into consideration besides the typical characteristics of Memlinc’s work, it appears probable that he served his apprenticeship at Mainz, and afterwards worked at Cöln as a journeyman, and this opinion is confirmed by the outstanding fact that in all the wealth of architectural embellishment in which his pictures abound the only town outside Bruges whose buildings are faithfully reproduced is this noted centre of art. That he should have travelled thither for the especial purpose of securing an accurate background for the first, fifth, and sixth panels of the Shrine of Saint Ursula, and not have cared to obtain as faithful settings for the incidents of the second and fourth panels ascribed to Basel, or for that of the third panel located at Rome, will scarcely stand the test of criticism. A study of these panels evidences an intimate acquaintance with the architectural beauties of Cöln, a knowledge obviously acquired at first hand during a period of his life devoted to Art. The master under whom he worked was in all probability the Suabian, Stephen Löthener, of Mersburg, near Constance, who had settled in Cöln before 1442, and died there in 1452. It is presumable that Memlinc may not have completed his studies at the time of that painter’s death. In the circumstances one can but conjecture as to where he completed the necessary training before attaining to the rank of a master-painter. Vasari and Guicciardini both assert that Memlinc was at some time or other a pupil of Roger De la Pasture (Van der Weyden), and, as this master returned from Italy in 1450, he may have come across Memlinc at Cöln and engaged him as an assistant. It is, however, quite possible that Memlinc stayed on at Cöln until Löthener’s death in 1452 and then went to Brussels, doubtless passing by Louvain and possibly working for a time under Dirk Bouts. Certain it is, judging from the many points of similarity in their work, that Memlinc came under Roger’s influence for a space sufficiently long to leave a strong impress of that master’s methods on his art. Memlinc’s contemporary, Rumwold De Doppere, has left it on record that he was “then considered to be the most skilful and excellent painter in the whole of Christendom”; and if Memlinc had left nothing to perpetuate his fame but such gems as the Shrine of Saint Ursula, at Bruges, the “Passion of Our Lord,” in the Royal Museum at Turin, that remarkable altarpiece, “Christ the Light of the World,” in the Royal Gallery at Munich, or even, as Fromentin suggests, only those two figures of Saint Barbara and Saint Katherine in the large altarpiece at Bruges, he would need nothing of the reflected glory of his alleged master to enhance his renown. Always assuming Memlinc to have stood in this relation to De la Pasture, Sir Martin Conway came to a happy conclusion when he wrote that Roger’s greatest glory is that he produced such a pupil—“that Memlinc the artist was Roger’s greatest work.”

PLATE III.—SAINTS CHRISTOPHER, MAURUS, AND GILES.

This, the central panel of an altarpiece, painted in 1484 for William Moreel, Burgomaster of Bruges, is now in the Town Gallery at Bruges.

THE first painting to bespeak his industry is now supposed to have been the famous triptych of the Last Judgment in the Church of Saint Mary at Danzig, commenced after 1465 and finished in 1472 or early in 1473.

Few pictures have evoked more controversy or been coupled with the names of more artists than the Danzig triptych. The entry in a local church register of 1616 which asserts that it was painted in Brabant by John and George van Eichen, an ascription varied at a subsequent period by substituting the name of James for John, carries no more weight than usually attaches to popular traditions, and was generally disregarded by the connoisseurs and experts who have debated the question for more than a hundred years. The names of Albert van Ouwater, Michael Wohlgemuth, Hugh Van der Goes, Hubert and John van Eyck, Roger De la Pasture, and Dirk Bouts have all been canvassed with more or less assurance. Memlinc’s name was first associated with the work in 1843, by Hotho, whose opinion met with wide acceptance, a notable convert to his view being Dr. Waagen, who in 1860 declared the triptych to be “not only the most important work by Memlinc that has come down to our time, but also one of the masterpieces of the whole school, being far richer and better composed than the picture of the same subject by Roger De la Pasture at Beaune, though that master’s influence is still perceptible,” though two years later he recognised in the figures the influence of Dirk Bouts; and in 1899 Kämmerer as emphatically declared that “no one who is acquainted with Memlinc’s authentic works can possibly doubt that this picture is the work of his hand.” In the absence of contemporary documentary evidence, and with the donors of the picture still unidentified, confronted moreover with the fact that in its composition the Danzig triptych differs altogether from Memlinc’s authenticated paintings, many experienced judges still hesitated to admit the claim put forward in his behalf. But the recent discoveries made by Dr. A. Warburg leave little room for doubt. In the fifteenth century there was a considerable Italian colony at Bruges, and the powerful Florentine firm of the Medici, whose ramifications extended over all Europe, had a branch establishment there in the name of Piero and Giovanni de’ Medici, the acting manager of which from 1455 to 1466 was Angelo di Jacopo Tani, who, after serving as bookkeeper of the firm’s agency in London, had been transferred to Bruges in 1450. Tani may have taken Memlinc into his household with a view to the production of the triptych under his own eye. The absence of Memlinc’s name from the guild registers of the period lends probability to the theory that he was employed by Charles the Bold, for ducal service exempted painters settling in Bruges from the obligation of purchasing the right of citizenship, and of becoming members of the local guild. It is presumed that Tani engaged Memlinc’s services at some date after 1465 to paint or, if the work had been commenced by some other painter, to complete this picture. While the dexter shutter, representing the reception of the elect by Saint Peter at the gate of Heaven, can only have been designed by a pupil of Löthener, it is equally certain that the upper portion of the central panel must have been designed by some one who had worked under Bouts or De la Pasture. In 1466 Tani visited Florence, and there married Katherine, daughter of William Tanagli. As their portraits and arms are on the exterior of the shutters, these cannot have been commenced before they were both in Bruges, some time in 1467, the date inscribed on the slab covering a tomb on which a woman is seated. The technique and colouring of the entire work are Netherlandish, and in the opinion of the most trustworthy critics are certainly the work of Memlinc. The painting completed, it was, at the commencement of 1473, despatched by sea to Florence, but the vessel bearing it was captured by freebooters, and the picture as part of the prize carried off to Danzig.

The patronage of the agent of the Medici was of course of incalculable advantage to a rising artist, and doubtless it served to secure for Memlinc the interest of Spinelli of Arezzo—whose portrait, now in the van Ertborn collection at the Antwerp Museum, he painted in the latter half of 1467 or the beginning of 1468, when this Italian medallist was in the service of Charles the Bold as seal engraver—and to bring his growing reputation to the notice of the ducal court. The negotiations for the hand of Margaret of York, begun in December 1466, and unduly protracted owing no doubt to the mental incapacity of Duke Philip III., were of course resumed at the expiration of the period of court mourning after his death on 15th June 1467. Following the example of his father, Charles may have commissioned Memlinc to accompany his ambassadors to the English court for the purpose of securing an up-to-date portrait of his intended consort. In the circumstances Memlinc would certainly have made the acquaintance of Sir John Donne, for the Donnes were ardent Yorkists high in the royal favour, and moreover the brother of Sir John’s wife, William, first Lord Hastings, filled the office of Lord Chamberlain to the king. But the triptych in the Chatsworth collection, though the outcome of this meeting, could not have been executed at the time, as the period of Memlinc’s visit would have been restricted to carrying out the ducal instructions. An opportunity for the necessary sittings was afforded later, when Sir John Donne, accompanied by his wife and daughter, journeyed to Bruges in the suite of the princess to assist at the wedding celebrations in July 1468. The omission of the sons from the family group in the triptych is sufficiently accounted for by the fact that they were in Wales at the time.

TO the art student these earliest of Memlinc’s paintings—the Donne triptych in particular—are replete with interest. In the first place, they attest the powers then already at the painter’s command as an exponent of his art, and they further serve as a standard of comparison by which to judge his afterwork. Memlinc was pre-eminently a religious artist, deeply imbued with Scriptural lore and well versed in hagiography, a fund of knowledge sublimated in the beautiful mysticism of the school of Cöln which had early subjugated his poetic temperament. His conception of the Madonna, based on a fervent appreciation of the purity, the tenderness, and the majesty of her nature was deeply rooted, and it led him to evolve the definite type which he presents to us in the Chatsworth picture, to which he faithfully adheres henceforth, at times enhancing its beauty—as witness the triptych in the Louvre and the altarpiece of Saint John’s Hospital at Bruges—until his ideal culminates in that marvellous embodiment of her supreme attributes preserved to us in the Van Nieuwenhove diptych. The Divine Infant, it is true, may not appeal to one in the same way as do the charming pictures of infant life in which the southern artists excelled. Whatever may be said of the fine men and intellectual women of the race, the northern type of babyhood cannot by any stretch of courtesy, apart from a mother’s loving weakness, be described as graceful. Still Memlinc’s conceptions of the Infant Saviour rank high in point of intellectuality, of expressiveness of eye, of grace of movement and charm of expression. The Donne triptych besides, from the point of view from which we are now considering it, is a valuable asset for the study of the impersonations of saints whom we find constantly recurring in his paintings: to wit, Saint Katherine and Saint Barbara—(Fromentin’s enthusiastic appreciation of these figures in the large altarpiece at Bruges has already been quoted)—Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist, and Saint Christopher. The same may be said of his angels. Taken from another standpoint, these early paintings of Memlinc are invaluable testimony of his rare gift for portraiture. It was a gift which may almost be taken as the specific appanage of the fifteenth century painters of the Netherlandish school. Some, like John van Eyck, used it with scrupulous exactitude, scorning to veil the palpable truth that at the moment and usually obtruded itself on his painstaking eye; others, and Memlinc prominently of their number, loved rather to seize on the fitful manifestation of the inner man and to idealise him. Both artists, taking them as types, were honest and true to their art, notwithstanding that the resulting truth in each case is deceiving, except we have very particular information regarding the individual portrayed. In any event, the Tani and Spinelli portraits are fine examples of the class, though perhaps Sir John Donne’s appeals to us more because of the fuller knowledge we have of the man. And finally, both the Antwerp and the Chatsworth paintings afford us beautiful examples of Memlinc’s art as a landscape painter, and in this respect certainly it may be safely asserted that he never produced better work.

PLATE IV.—NICHOLAS SPINELLI OF AREZZO.

Nicholas Spinelli, born 1430, was in 1467-68 in Flanders, in the service of Charles the Bold as seal engraver. He died in 1499 at Lyons, where this portrait was acquired by Denon. He is depicted holding a medal, showing a profile head of the Emperor Nero, with the inscription “NERO CLAVDius CÆSAR AVGustus GERManicus TRibunicia Potestati IMPERator.” It was bought from the heirs of Denon by M. van Ertborn, who bequeathed it to the Museum at Antwerp.

FROM the consideration of these three works executed in the sixties we pass on to a decade of more notable achievement. The public rejoicings which had inaugurated the new reign were already dimmed to recollection in the disquieting civil and national complications that ensued, culminating in the disastrous battle of Nancy on 5th January 1477, in which the ducal troops were put to rout and Charles himself lost his life. He was succeeded by his only daughter, Mary, who on 19th August of the same year by her marriage to Maximilian, son of the Emperor Frederick IV., brought Flanders under the rule of the House of Austria, and thus involved the Flemish burghers in that lamentable struggle which, after many alternations of fortune, was one of the chief causes that led to the downfall of Bruges. Memlinc, as a newcomer without rooted interests or strong political bent, wholly wrapt in his art, naturally steered clear of political entanglements, though ready enough on occasion to take his share of the public burden which the fortune of war imposed, as witness his contribution to the loan raised to cover the expenses of the military operations against France. But his placid disposition shrank from the heat and ferment of public life, though his sympathies no doubt were all with the burghers and guildmen with whom he associated, among whom he found the most liberal supporters of his art to the exclusion of court patronage, and from whose womankind he selected a helpmate. Memlinc married later in life than was the custom of his day, when it was usual for craftsmen to take unto themselves a wife at the expiration of their journeymanship, after they had established their competence, paid the indispensable guild fees, and taken the no less essential vows to bear themselves honestly and to labour their work as in the sight of God; for it was only at some date between 1470 and 1480, when already a man of middle age, that he led Anne, daughter of Louis De Valkenaere, to the altar. It is impossible to determine the year, but on the 10th of December 1495 we find the guardians of the three children of the marriage acting on their behalf in the local courts in the winding-up of their father’s estate, which at any rate proves that the eldest at that time must have been still a minor, or under the age of five-and-twenty. Apart from his wife’s dowry, of which we have no knowledge, Memlinc’s circumstances were then already much above the ordinary, for in 1480 out of the 247 wealthiest citizens only 140 were taxed at higher rates, and it is on record that in the same year he purchased a large stone house and two smaller adjacent ones on the east side of the main street that leads from the Flemish Bridge to the ramparts, in a quarter of the town much affected by artists, and within the Parish of Saint Giles, beneath the spreading trees of whose peaceful God’s acre he was to find an abiding resting-place some fourteen years later, by the side of his old friend the miniaturist William Vrelant, who predeceased him by some thirteen years, to be joined there in after years by many another eminent artist, such as John Prévost, Lancelot Blondeel, Peter Pourbus, and Antony Claeissens.

That he was a busy man the record of works that have come down to us from this decade alone amply testifies. The “Saint John the Baptist,” in the Royal Gallery at Munich (1470); the exquisite little diptych “The Blessed Virgin and Child,” in the Louvre, painted (c. 1475) for John Du Celier, a member of the Guild of Merchant Grocers, whose father was a member of the Council of Flanders; the panel in the National Gallery, which we reproduce; the magnificent altarpiece in the Royal Museum at Turin painted for William Vrelant (1478); the famous triptych executed for the high altar of the church attached to the Hospital of Saint John at Bruges (1479); and the triptych “The Adoration of the Magi” presented to the Hospital by Brother John Floreins (1479), all belong to this period: while with the year 1480 are associated the portraits of William Moreel and his wife, in the Royal Gallery at Brussels; that of one of their daughters as the Sibyl Sambetha, in Saint John’s Hospital; the marvellous composition in the Royal Gallery at Munich, “Christ the Light of the World,” painted to the order of Peter Bultinc, a wealthy citizen of Bruges and a member of the Guild of Tanners; and the triptych “The Dead Christ mourned by His Mother,” in Saint John’s Hospital—let alone the numerous other works attributed to him but not authenticated or which have been lost. The bare record, however, conveys but a feeble idea of the immensity of the labour this output involved.

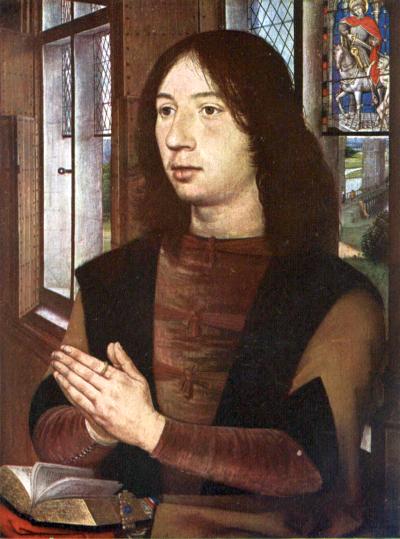

PLATE V.—MARTIN VAN NIEUWENHOVE.

The companion of the painting reproduced in Plate I., and is in the Hospital of Saint John.

The panel in the National Gallery, which may be ascribed to 1475, arrests our attention for the moment. It presents to us the Blessed Virgin and Child in attitudes closely corresponding to those in the earlier Donne triptych, but both are more pleasing figures in respect of pose, the attitude of the Madonna in particular being less constrained and the expression happier and more natural. The figure of the angel too has gained in gracefulness. The donor under the patronage of Saint George appeals to one as a living personality. Of these two figures a lady critic complains that they are “characteristic examples of Memlinc’s inability to depict a really manly man”; and she endeavours to give greater point to this criticism by contrasting the painter’s methods with those of John van Eyck, wholly of course to the disadvantage of the former. In the present case the identity of the donor remains a mystery: he may not have been the really manly man the idealist would require, and also he may have been the man of reverent and sweet disposition revealed to us in this portrait. It is for the softening and idealisation of the face from the reality, however, that fault is commonly found with Memlinc as a portrait-painter. But, after all, what is this idealisation of the subject but the highest aim and truest concept of art? It is no difficult matter for the competent painter to produce a counterpart of the outward flesh with all its peculiarities, even to the last wrinkle and the least significant blemish, and be awarded the palm for “stern realism”; but to conceive the inner soul of the man, to seize and fix that conception on panel or canvas, surely that is the higher art? It is true that in the men whom Memlinc portrayed there is a marked similarity of expression, arising obviously from the fact that they are usually pictured in an attitude of devotion, and that in the frame of mind this attitude imposed they suffered some loss of workaday individuality. But surely it is not to Memlinc’s discredit that his clients were of the devotional order? Nor is the criticism of the Saint George as mild and effeminate any more to the point; for when the appeal is from Memlinc to Van Eyck one is forcibly reminded of the votive picture of the Virgin and Child by that master in the Town Gallery at Bruges, in which we have the donor under the patronage of a Saint George whom for sheer inanity of expression and utter awkwardness of demeanour it would be hard to beat. And yet in neither instance, we may safely assume, was the figure the type the artist would have created for the valiant knight of the legend. Apart from this, a careful study of Memlinc’s many works will reveal to the most exacting a sufficiency of evidence that his art was equal to any demands that might have been made of it; of his preference for the milder and more religious type of man, however, there can be no doubt.

It were idle to speculate as to the length of time Memlinc devoted to the production of his pictures, seeing the meagreness of the data afforded us for the purpose. His peculiar technique, however, which avoided the accentuation of light and shade, and thereby simplified the scheme of colouring, lent itself to rapid execution. Even so, paintings like the altarpiece in the Royal Museum at Turin and that in the Royal Gallery at Munich must have made heavy calls on his time through a number of years. As examples of the powers and wealth of resource of the artist these masterpieces stand almost alone. The architectural setting of the former, a wholly imaginary Jerusalem, is so contrived as to assist in the most natural manner the precession of the Gospel story from the triumphal entry into the Holy City to the Resurrection and the manifestation of Christ to Mary Magdalene. As without conscious effort the eye is guided along the line of route followed by the Redeemer, one treads in imagination in the Divine footsteps through the hosannahing multitude in the extreme background on the right, and turning to the left arrives at the Temple steps in time to witness the casting out of the buyers and sellers; descending thence and bearing gradually towards the right a turn of the street leads one to the scene of the Last Supper, which Judas has already left to confer with the priests under a neighbouring portico as to the betrayal of his Master; and eventually one arrives at the Garden of Olives, to be confronted in rapid succession with the Agony and the picture of the sleeping disciples, the rush of armed men, Judas’ traitorous kiss and Peter in the act of striking at Malchus. Following the multitude for some little distance one reaches the heart of the city, where the successive incidents of the Passion are grouped each under a separate portico showing on to a spacious courtyard in the very centre of the panel—Christ before Pilate and his expostulating wife, the Flagellation, the Crowning with thorns and mocking of Our Lord, Christ before Herod and the Ecce Homo, with the preparations for the Crucifixion going on the while in the open courtyard. These completed, the mournful procession passes under a palace gateway into the forefront of the picture, bears to the left and issues through the city gate, where the Mother of Christ, the beloved disciple, and the holy women have gathered together, into the open country, where at the foot of the hilly way that skirts the city walls Simon of Cyrene comes forward to relieve the fallen Saviour in the burden of the Cross; presently the procession is lost to view at a bend of the road only to reappear on the slopes of Calvary, which is triplicated here for the purpose of re-enacting the three scenes associated with it—of the Nailing to the Cross, of the Death of Our Lord, and of the Descent from the Cross. Lower down on the left we assist at the Entombment and at the Deliverance of the Just from Limbo, and further away we witness the Resurrection and, in the far background, the manifestation of Our Lord to Mary Magdalene. Viewed as a whole it is a marvel of composition enhanced by a brilliancy of colouring, and every scene in it a delicately finished miniature. Apart from the architectural setting, the three Calvaries, and the duplication of the Holy Sepulchre imposed by the necessity of representing both the Entombment and the Resurrection, the most captious can discover nothing to abate the enthusiastic admiration which this altarpiece excites, or one’s wonder at the masterful manner in which Memlinc has succeeded in developing the story of the Passion in some twenty scenes necessitating the introduction of considerably over two hundred figures, apart from the animal and bird life that supplements them, within the narrow compass of a panel only fifty-five centimetres high by ninety centimetres in breadth! The extreme corners of the foreground are filled in with exquisite portraits of the donors, the miniaturist William Vrelant and his wife, for whom one feels that Memlinc has tried to excel himself in this masterwork.

Scarcely less surprising as a composition is the story in bright luminous colours told in the Munich altarpiece, a work of considerably larger dimensions (80 by 180 centimetres), commonly described as “The Seven Joys of Mary,” but for which the more appropriate title has been suggested of “Christ the Light of the World.” It is the story of the manifestation of Our Lord to the Gentile world in the persons of the Wise Men from the East, closely correspondent, as was Memlinc’s wont, to the Gospel narrative and Christian tradition, except perhaps in this one respect, that the artist’s innate love of moving water has suggested to him the original conceit of depicting the departing Magi as setting sail for their distant homes across the boundless waters. This portion of the background and the greater wealth of surrounding landscape greatly relieves the architectural setting, which is not so overpowering as in the Turin altarpiece. The composition too, as becomes the subject, is teeming with the joy of life in varying aspects. Here we have the gay cavalcade with streaming banners galloping along the road to Bethlehem, there the shepherds peacefully tending their flocks on the grassy slope, their watch beguiled by the strains of a bagpipe; here the scene at the Manger, all love and devotion, and the running stream nigh by at which the horses are being watered the while the Magi are making their act of adoration, there the kings with their retinues triumphantly riding away over the rocky heights; anon we have the sequence of miracles that attended the Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt—the wheat that grew and ripened in a day, the date-palm bending to offer its fruit to the Virgin Mother resting beneath its shade while the unsaddled ass grazes as it lists and Joseph fetches water from a neighbouring spring; elsewhere the risen Christ appearing to the fishing apostles, and far beyond across the waters in the background the setting of the sun in all its glory. Every scene that lends itself to the treatment has its beauty enhanced by the beauties of Nature. The one sorrowful incident in the whole story, the Massacre of the Innocents, is a mere suggestion of this cruel episode. Memlinc’s nature shrank from the interpretation of evil, and in this particular instance has admirably succeeded in commemorating the incident of the massacre without involving it in any of its horror. A pleasing innovation may also be noticed in the treatment of his portraits of donors, Peter Bultinc and his son being introduced as devout spectators of the scene presented in the stable at Bethlehem, which they humbly contemplate through an opening in the wall. “The more one examines this picture, the greater one’s astonishment at the amount of work which Memlinc has lavished on it, at the exquisite beauty of the various scenes, the marvellous ingenuity displayed in separating them one from another, and the skill with which they balance and are brought into one harmonious whole.”

PLATE VI.—MARTYRDOM OF SAINT URSULA.

This forms the eighth panel of the famous shrine, completed in 1489 for the Hospital of Saint John at Bruges, where it may be seen. The archer is a portrait of the celebrated Dschem, brother of the Sultan Bajazet, taken prisoner at Rhodes in 1482, copied from a portrait in the possession of Charles the Bold.

The Turin altarpiece was completed not later than 1478, in which year William Vrelant gave it to the Guild of Saint Luke and Saint John (Stationers); the Munich one at any rate some time before Easter 1480, at which date the donor presented it to the Guild of Tanners. But already then Memlinc had undertaken the triptych in the Hospital of Saint John painted to the order of its spiritual master, Brother John Floreins, acknowledged to be technically the most perfect work he completed before the end of 1480; and also the larger triptych for the high altar of the Hospital church.

MEANWHILE the contest in which the burghers of Bruges had become involved through the disputes between the States of Flanders and Maximilian over the guardianship of his son, was precipitating the decay of the town which the relentless forces of Nature had long since decreed. As early as 1410 the navigation of the great haven of the Zwijn had become impeded, and so rapidly had the silting up advanced that before the close of the century no vessel of any considerable draught was able to enter the port of Damme. Entirely engrossed in the safeguarding of the remnant of their privileges, no serious effort was made to combat the mischief, and in the end Bruges found herself absolutely cut off from the sea. On the other hand, in the enjoyment of peace and the greater security it engendered, Antwerp was slowly asserting herself and gradually attracting to her quays the merchant princes from the littoral of the Zwijn; and as commerce imperceptibly gravitated towards the city by the Scheldt the foreign consuls one by one forsook the doomed emporium of the Hanseatic League. Memlinc, pursuing the even tenor of his life, continued to produce with unabated ardour and undiminished skill, and with this period—the last fourteen years of his life—is associated the most celebrated of all his works, the marvellous Shrine of Saint Ursula, the gem of the priceless collection preserved to this day in the old chapter-room of Saint John’s Hospital. When this masterpiece was first undertaken we are not in a position to say, but it was completed in 1489, and on the 21st day of October in that year the relics for whose safe keeping it had been designed were deposited within it. But to the eighties belong other memorable productions. In 1484 was finished the interior of the altarpiece for the Moreel chantry in the Church of Saint James, now housed in the Town Gallery at Bruges; in 1487 was painted the portrait of a man preserved in the Gallery of the Offices at Florence, and also was completed the wonderful diptych for Martin van Nieuwenhove, whose portrait we reproduce as the finest example of Memlinc’s work in that particular department of art; and in 1490 the finishing touches were put to the picture in the Louvre of the Madonna and Child, to whom saintly patrons are presenting the family of James Floreins, a younger brother of the donor of the triptych picturing the Adoration of the Magi which, as we have seen, was completed in 1479.

But work, which always spelt happiness to Memlinc, meant something more to him in this decade of his career. Death in 1487 robbed him of his wife. One pictures to oneself the bereaved artist seeking solace from the grief of his widowed home in intensified application to his art. The refining discipline of sorrow was exercising its softening influence on a nature of whose religious fervour and deep piety his life-work is an abiding testimony. Absorbed in the production of the Shrine of Saint Ursula, does not the instinct of human sympathy suggest to us the artist spending himself in this inimitable work for a monument of his love worthy of the memory of the helpmate who had devoted her life to enhance the happiness of his own, herein seeking and finding surcease of the sorrow that now overshadowed his life, the burden of work balancing the burden of grief? And what a monument! So familiar is the legend and the unique interpretation of it he has left us, one feels it would be a work of supererogation to dwell on the story. But the treatment, viewed by the light of Memlinc’s bereavement, discloses fresh beauties in every panel. Critics have dwelt on the unreality of the death scenes in this shrine. Memlinc, as we have had sufficient occasion to observe, shrank from the painful expounding of evil. But for him death had no terrors: it was but the passing over to the ineffable reward of a well-spent life, and this innate feeling he conveys to us in the placid acceptance of death by Saint Ursula and her virgin band as but a stepping across the threshold to everlasting bliss. These critics, on the contrary, look for the betrayal of fear and anguish, for the manifestation of human suffering: but, like the martyrs of the early Church, we find these victims of the ruthless Huns not alone meeting their death in a spirit of resignation, but welcoming it with abounding peace and a joyful self-surrender, strong in the hope and faith of the hereafter: as the artist himself was wistfully looking forward to the day and the hour that would reunite him there to the one he had loved best on earth.

Turning to the other works of this period which we have mentioned, the Moreel altarpiece arrests our attention. Apart from the particular friendship which linked him with William Vrelant and the brothers Floreins, few men were more likely to attract him than the donor of this painting. The great-grandson of a Savoyard, Morelli, who had settled in Bruges in 1336, William Moreel, a member of the Corporation of Grocers, after filling various civic offices, was elected burgomaster of Bruges in 1478, and again in the troublous days of 1483. His standing is sufficiently attested by the record that in 1491 only ten of his fellow-citizens were taxed at a higher rate. Able and strong-willed, a capable financier and ardent politician, he was ever foremost in defending the rights and liberties of his country, and to such purpose that Maximilian, who had imprisoned him in 1481, refused when he made his peace with the States of Flanders, on 28th June 1485, to include him in the general amnesty. He retired to Nieuport, but returned to Bruges in 1488 and was chosen as treasurer of the town, and in July 1489 was presented by the magistrates with the sum of £100 in recognition of services rendered. Reference has been made to the independent portraits of Moreel, his wife, and one of his daughters. In the triptych under notice the whole family are gathered together, the father and his five sons, his wife Barbara van Vlaenderberch and their eleven daughters. The donor’s head is probably a copy of the Brussels panel, assuming that at the time it was painted, Moreel was still in prison; while that of his wife, more careworn and aged, bears testimony to the anxiety occasioned her by her husband’s confinement. This painting, too, will afford the critics who love to find fault with the Flemish school for its alleged inability to do justice to the winsomeness of child life an opportunity of reconsidering their judgment by the light of the Infant Jesus whom Saint Christopher is bearing across the ferry, and once more we are met in every portion of the picture with brilliant exemplifications of the artist’s special aptitude for interpreting the beauties of Nature.

Scarcely less attractive, and in some respects even more interesting, is the celebrated diptych associated with the name of Martin van Nieuwenhove. Here we have a departure from Memlinc’s usual practice, which was to present the Blessed Virgin and Child in an open portico, the artist picturing them in a room amply lighted by windows, the upper portions of which are adorned with pictures in stained glass, while the lower halves, mostly thrown open, reveal inimitable scenes of country life; moreover, a convex mirror at the back of Our Lady reflects the depicted scene of the interior. The donor belonged to a noble family long settled in Bruges, evidently a man of great promise, for after being elected a member of the Town Council in 1492, he was chosen burgomaster in 1497 at the early age of thirty-three. Unfortunately he passed away in the prime of life a short three years later. The painting dates from 1487, and the portrait is Memlinc’s masterpiece in that branch of art.

PLATE VII.—AN OLD LADY.

This fine portrait, with its companion, was formerly in the Meazza collection at Milan, dispersed in 1884. It was exhibited at Bruges in 1902 (No. 71), since when it has been purchased by the Louvre, where it is now to be seen. The companion portrait is in the Berlin Museum.

The panel in the Louvre ranks equally with this production, its chief feature being the marvellous grouping of the donors and their family. James Floreins, younger brother of John, the spiritual master of Saint John’s Hospital, belonged to one of the wealthiest of the Bruges guilds, the Corporation of Master Grocers, among whose members (John Du Celier and William Moreel to wit) Memlinc found such generous patrons of his art. He had married a lady of the Spanish Quintanaduena family, who bore him nineteen children: the eldest son, a priest, is represented in furred cassock and cambric surplice, and the second daughter in the habit of a Dominican nun. This picture is another but wholly different departure from the setting usually affected by the artist in his presentment of the Virgin and Child. The throne here is erected in the middle of the nave of a round-arched church, a rood-screen of five bays shutting off the choir. The north transept porch, is adorned with statues of the Prophets, the south portal with others of the Apostles. The difficulty of grouping so large a family in the circumscribed space about the throne is obviated with consummate skill, the father and two eldest sons on the one side, and the mother and two eldest daughters on the other, being placed well in the foreground, while the younger members of either sex are disposed in the aisles, the upstanding figures of Saint James the Great and Saint Dominic beside the throne filling the void on either side which this arrangement entailed. Even here, with the limited opportunities the architectural setting affords, Memlinc will not be denied his predilection for landscape ornamentation, two delightful glimpses of country life enchanting the eye as it wanders down the transepts and out on to their porches.

If in these pages attention has perhaps been somewhat too exclusively devoted to the portraits of men left us by Memlinc, obviously enough because of the greater interest they excite by the stories known of their careers, it must not be supposed that he proved himself less skilful as a portrayer of women. As a rule the wives of the donors in his pictures are of the homely type, but they appeal to us none the less as typical examples of the womankind of a burgher community in which the virtues of the home were cherished and sedulously cultivated. Two exceptionally fine specimens of male and female portraiture, which most likely belong to this period, are the bust of an old man in the Royal Museum at Berlin and that of an aged lady, recently acquired by the Louvre for the very substantial sum of 200,000 francs. If, as has been suggested, these are portraits of husband and wife, it is regrettable that they should have strayed so far apart, but the latter we have selected for illustration as perhaps the best available example to demonstrate Memlinc’s aptitude for the interpretation of the dignity of old age in woman.

More amazing perhaps than the magnitude of the work Memlinc achieved is the dearth of information concerning him that has been vouchsafed to us. Until 1860 nothing whatever was known of the story of his life, and what has been since discovered is almost entirely due to the painstaking researches of one or two individuals. These revealed the fact of Memlinc’s marriage, the name of the woman he chose for his wife and that of her father, the fact that she bore him three sons—John, Cornelius, and Nicolas—the year of his wife’s death, the record of house property bought by him, the date of his own death and his place of burial, and this is the sum total of the material at our disposal, apart from his paintings, with which to build up his biography. The Shrine that is his masterpiece once completed, the only other dated work of which we have any knowledge is the polyptych altarpiece which hangs in the Greverade chantry of the Cathedral at Lubeck. This bears on its frame the date 1491; but the execution of the painting is very unequal, and it appears probable that the greater part is the work of pupils. Perhaps Memlinc felt that he had lived his life, and was content to lay aside palette and brush in the consciousness that he had given the world of his best. May-be, too, as the years began to tell, there grew a yearning for the privacy of home life in more intimate communion with the motherless children from whom he himself was soon to be parted. All too speedily the end came, for he passed away on the 11th of August 1494, at a ripe old age considering the average length of days meted out to man in his time.

BRUGES, the scene of his stupendous lifework and his home for nearly the last thirty years of his life, was fast settling down to utter stagnation and the general poverty it superinduced. One needs to realise the measure of her decay to understand the possibility of such a personality as Memlinc’s fading from the public memory. True, he had founded no school to perpetuate his art and cherish his name and reputation. Twice we find mention of apprentices in the register of the Guild of Painters—a John Verhanneman, inscribed on 8th May 1480, and a Passchier Van der Meersch, in 1483. Neither attained the rank of master-painter. Nor is it known that any of the three sons inherited their father’s talent or followed his profession. However, we remember that Rumwold De Doppere, writing of his death in the year it occurred, asserted that he was “then considered to be the most skilful and excellent painter in the whole of Christendom,” while Van Vaernewyck, as late as 1562, tells of the houses of Bruges being still filled with paintings by Memlinc among other great artists. And yet so completely was he forgotten within a century of his death that Van Mander, when preparing his biographies of Netherlandish painters (published in 1604), could only learn that he was in his day “a celebrated master who flourished before the time of Peter Pourbus”—that is, before 1540! Neglect and disdain followed speedily on forgetfulness, and the scattering of his priceless works commenced. The magnificent picture of the Passion of Christ in the Turin Museum, which adorned the altar of the chapel of the Guild of Saint John and Saint Luke in the Church of Saint Bartholomew until 1619, was then removed to a side wall, and five years later sold to make room for an organ! The no less famous painting “Christ the Light of the World,” which graced the altar of the chapel of the Guild of Tanners in the Church of Our Lady until 1764, was then removed to the house of the dean, who a few years later sold it to a picture-dealer at Antwerp for 20 l.! And so these masterpieces were made the sport and spoil of picture-dealers and traffickers in curiosities. Under Spanish rule further toll was levied on the art treasures of Bruges, and of what escaped the vulgar vandalism of the Calvinists, whose utter inability to create was only equalled by their senseless capacity for destruction, the French revolutionaries, whose sense of the beautiful in art not all their irreligion had sufficed to stifle, claimed a considerable share. Fortunately the ultimate defeat of Napoleon made restitution in a measure possible, and so the Moreel triptych, seized on 23rd August 1794, and the Van Nieuwenhove diptych, carried off in the same month, were recovered in 1815. Still the fact remains that Bruges at this date possesses only seven of Memlinc’s works. The remainder are dispersed among the galleries of the Continent—in Brussels and Antwerp; in Paris; in Madrid; in Rome, Florence, Turin, and Venice; in Vienna and Buda-Pesth; in Berlin, Frankfort, Munich, Danzig, Lubeck, Hermannstadt, and Woerlitz; and at the Hague; while England boasts of three pictures, two in the National Gallery and one at Chatsworth.

Although Memlinc founded no school, the masters of his day and others who settled in Bruges in the sixteenth century were to a very appreciable extent influenced by his art. Gerard David, Albert Cornelis, Peter Pourbus, and the Claeissens all felt its impress, and if the traditions of the old school survived in Bruges to a later period than in other centres, and well into the seventeenth century, it was mainly through the instrumentality of these painters. In contrasting the lives of mediæval and modern artists one cannot escape a feeling of regret that the former should so utterly have neglected the literary side of their calling. What a revelation to us would have been the discovery of the personal recollections of but one of these great masters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and what a world of trouble they would have saved the art students of after generations! But seemingly the demand for this class of literature had not then arisen, while the craving for notoriety which would have compelled an effort of this description was altogether foreign to the single-minded nature of a school whose art was to its exponents something more than the realisation of worldly ambition or the satisfaction of a vulgar lust of gain. There could have been no hankering after either in the type of man revealed to us by the lifework of Memlinc. And so it was that with the reawakened interest in mediæval painting which made itself manifest in the nineteenth century the services of the archæologist had to be requisitioned. Difficult indeed would it be to exaggerate the immensity of the task imposed upon him. The sifting from the mass of popular fiction which had gathered round Memlinc’s name the few grains of truth embedded in it, the ceaseless delving among municipal and ecclesiastical archives for a chance record of some incident in his career, the slow process of authenticating the genuine from the ruck of doubtful and spurious works associated with his name, half a century of unswerving devotion to the task has not yet brought us within measurable reach of its accomplishment. Every day, so to speak, brings to light some new fact, often compelling a revision of conclusions which in its absence were sufficiently justified.

PLATE VIII.—OUR LADY AND CHILD, SAINT GEORGE AND THE DONOR.

This painting, formerly in the Gierling collection, was purchased by Mr J. P. Weyer of Cöln for 450 thalers, and at the sale of his pictures in 1862, by Mr O. Mündler for 4600 thalers for the National Gallery.

Thus it happened that the identification of the donors of the “Last Judgment” at Danzig, in 1902, led to the recognition of this earliest example of Memlinc’s art. And so no doubt will it happen again, each fresh discovery amplifying the knowledge necessary to remove doubt as to the authenticity of attributed works. But even so, what an advance from half a century since, when the personality of the painter was but the sport of idle legend, and loomed vaguely on the horizon in the distorted outlines of a loathsome caricature! If dearth of information is a powerful incentive to the imagination, then the evolution of the Memlinc legend goes far to establish its potency. An obscure seventeenth-century tradition had it that Memlinc painted a picture for the Hospital of Saint John in grateful recognition of services rendered to him by the Brethren of that charitable foundation: from which indeterminate report grew a tale of a dissolute soldier of fortune spared from the shambles of the field of Nancy dragging his wounded and diseased body to the Hospital gates, and beguiling the weary hours of a long convalescence there in the production of a masterpiece of painting in token of his gratitude. As an unconnected story for the amusement of simple-minded folk the fable is not without merit of a sort, but what a libel on the Christian artist who transcends all the painters of his age in the interpretation of deep religious feeling, and the shaping of whose whole life must have been a novitiate to this end! We have travelled a long road since the days when this preposterous legend was exploded. True, the exhumation of Memlinc’s individuality from the burial-ground of lost memories has been a slow and arduous process; but the rich store of knowledge now at our command is an abundant testimony to the patience of the experts who have garnered it.

It is not given to us to be all swayed in the same way or to the same extent by Art in any of its forms; but few who have been led to contemplate the masterpieces of the Netherlandish school will fail to pay the tribute of admiration these wonderworks evoke, and bear testimony to their educational value. For Hans Memlinc it is not claimed that he surpassed in each department of his art all the other painters who helped to build up the fame of the Netherlandish school: in some material respects his methods differed widely from theirs, and he elaborated a technique distinctly his own. It is not likely to be imputed that his sedulous avoidance of the marked contrasts of light and shade was a confession of inability to realise their treatment, though possibly he may be thought by some to have weakly followed the line of least resistance. Of course, Memlinc, like every other great artist of his age, had his limitations. His knowledge of anatomy naturally was not equal to the exact requirements of science, the pose of his figures not absolutely conformable to the ideals of the dilettante in respect of grace of carriage or correctness of deportment. Though critics contrast the simplicity of his art with the grandeur of style of Van Eyck, commonly with some predilection for the latter, yet it is possible for one to be subjugated by it and still feel to the full the fascination of the tender beauty inherent in the former. In his conceptions of the great mysteries of the Christian faith, in the characterisation of the many saints he portrayed, and above all in his varied presentation of womanhood he certainly excelled. In the “Last Judgment” at Danzig we have probably the least successful of his great efforts. The conception is not original, though admittedly one of the finest produced up to that time; also it is his earliest extant work, and in the style of a master from whose controlling influence he had not yet emancipated himself. But the fault lies rather with the subject. Many an artist has laboured at it, not always perhaps from choice; but the painter has yet to be born who will produce a convincing picture of that unrealised tragedy. Any attempt that falls short of conveying to the mind and soul of man the awe-full warning it should express necessarily bears the stamp of failure; and when, as too often is the case, it but provokes a smile by reason of its incongruity, the effort it cost stands unjustified. Not that Memlinc’s conception errs conspicuously in this sense: but it lacks conviction, and not all the beautiful work it exhibits can close our eyes to the fact.

To the up-to-date art critic of the weekly press, steeped in modernity, all this grand religious art of the middle ages is but as the dead ashes of a fire that once glowed but has now lost its warmth; or, to vary the simile, he contemptuously relegates it to the scrap-heap of antiquated material as the useless remains of a “dead language”; little bethinking himself of the great underlying truth he was unconsciously voicing. For just as all succeeding literatures found their spring and inspiration in the magnificent literatures enshrined in the great dead languages of Rome and Greece, so likewise has modern art, unconsciously if you will, but none the less assuredly, derived the essence of its loveliness from the mediæval art it affects to despise. Art of any kind to be great must have realised its greatness through the vivifying power of the art that had gone before. Ex nihilo nihil fit. The impellent craving after realism of the materialistic school of to-day is but a perverted form of the love of truth which was the keynote of all mediæval art, its cult of the sensuous but a depraved phase of a love of the beauty in virtue and godliness which characterised the latter: the great touch of faith is wholly wanting. In art as in all things human there is no finality; but the while Bruges subsists, though she were utterly bereft of all her picturesqueness and the wealth of architectural beauty that endears her to the artist mind, so long will that treasure-house of Memlinc’s art, the small chapter-room in the Hospital of Saint John, continue to exercise its educating influence, and so long, because of it, will the old Flemish capital, though shorn of all its pristine glory, continue to be one of the most cherished shrines of the art pilgrims of the world.

The plates are printed by Bemrose & Sons, Ltd., Derby and London

The text at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh