STEPHEN R. RIGGS, D.D., LL.D.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Mary and I

Forty Years with the Sioux

Author: Stephen Return Riggs

Release Date: May 25, 2013 [eBook #42806]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARY AND I***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/maryandi00riggrich |

STEPHEN R. RIGGS, D.D., LL.D.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

BY

REV. S. C. BARTLETT, D.D.

PRESIDENT OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

BOSTON

Congregational Sunday-School and Publishing Society

CONGREGATIONAL HOUSE

Copyright, 1880, by Stephen R. Riggs.

Copyright, 1887, by Congregational S. S. and Publishing Society.

Electrotyped by C. J. Peters and Son, Boston.

To My Children,

ALFRED, ISABELLA, MARTHA, ANNA, THOMAS,

HENRY, ROBERT, CORNELIA,

AND EDNA;

TOGETHER WITH ALL THE GRANDCHILDREN GROWING

UP INTO THE MISSIONARY INHERITANCE

OF THEIR FATHERS AND

MOTHERS,

THIS BOOK IS INSCRIBED BY

THE AUTHOR.

This book I have inscribed to my own family. It will be of interest to them, as, in part, a history of their father and mother, in the toils and sacrifices and rewards of commencing and carrying forward the work of evangelizing the Dakota people.

Many others, who are interested in the uplifting of the Red Men, may be glad to obtain glimpses, in these pages, of the inside of Missionary Life in what was, not long since, the Far West; and to trace the threads of the in-weaving of a Christ-life into the lives of many of the Sioux nation.

“Why don’t you tell more about yourselves?” is a question which, in various forms, has been often asked me, during these last four decades. Partly as the answer to questions of that kind, this book assumes somewhat the form of a personal narrative.

While I do not claim, even at this evening time of my life, to be freed from the desire that good Christian readers will think favorably of this effort of mine, I can not expect that the appreciation with which my Dakota Grammar and Dictionary was received, by the literary world, more than a quarter of a century ago, will be surpassed by this humbler effort.

Moreover, the chief work of my life has been the part I have been permitted, by the good Lord, to have in giving[Pg 6] the entire Bible to the Sioux Nation. This book is only “the band of the sheaf.” If, by weaving the principal facts of our Missionary work, its trials and joys, its discouragements and grand successes, into this personal narrative of “Mary and I,” a better judgment of Indian capabilities is secured, and a more earnest and intelligent determination to work for their Christianization and final Citizenship, I shall be quite satisfied.

Since the historical close of “Forty years with the Sioux,” some important events have transpired, in connection with our missionary work, which are grouped together in an Appendix, in the form of Monographs.

Beloit, Wis., January, 1880.

Note:—This book, first published by the author, though with the imprint of W. G. Holmes, Chicago, has met with such favor as to indicate that it should be brought out under auspices that would give it to a larger circle of those interested in Indian missions. And to carry on the life of its author to its close, and give a more complete view of the progress of the work, another chapter has been added, making the “Forty Years” Fifty Years with the Sioux.

The churches owe a great debt of gratitude to their missionaries, first, for the noble work they do, and, second, for the inspiring narratives they write. There is no class of writings more quickening to piety at home than the sober narratives of these labors abroad. The faith and zeal, the wisdom and patience, the enterprise and courage, the self-sacrifice and Christian peace which they record, as well as the wonderful triumphs of grace and the simplicity of native piety which they make known, bring us nearer, perhaps, to the spirit and the scenes of Apostolic times than any other class of literature. How the churches could, or can ever, dispense with the reactionary influence from the Foreign Mission field, it is difficult to understand. Doubtless, however, when the harvest is all gathered, the Lord of the Harvest will, in his wisdom, know how to supply the lack.

Some narratives are valuable chiefly for their interest of style and manner, while the facts themselves are of minor account. Other narratives secure attention by the weight of their facts alone. The author of “Mary and I; Forty Years with the Sioux” has our thanks for giving us a story attractive alike from the present significance of its theme and from the frank and fresh simplicity of its method.

It is a timely contribution. Thank God, the attention of the whole nation is at length beginning to be turned in[Pg 8] good earnest to the chronic wrongs inflicted on the Indian race, and is, though slowly and with difficulty, comprehending the fact, long known to the friends of missions, that these tribes, when properly approached, are singularly accessible and responsive to all the influences of Christianity and its resultant civilization. Slowest of all to apprehend this truth, though with honorable exceptions, are our military men. The officer who uttered that frightful maxim, “No good Indian but a dead Indian,”—if indeed it ever fell from his lips,—needs all the support of a brilliant and gallant career in defence of his country to save him from a judgment as merciless as his maxim. Such principles, let us believe, have had their day. They and their defenders are assuredly to be swept away by the rising tide of a better sentiment slowly and steadily pervading the country. The wrongs of the African have been, in part, redressed, and now comes the turn of the Indian. He must be permitted to have a home in fee-simple, a recognized citizenship, and complete protection under a settled system of law. The gospel will then do for him its thorough work, and show once more that God has made all nations of one blood. He is yet to have them. It is but a question of time. And the Indian tribes are doubtless not to fade away, but to be rescued from extinction by the gospel of Christ working in them and for them.

The reader who takes up this volume will not fail to read it through. He will easily believe that Anna Baird Riggs was “a model Christian woman,”—the mother who could bring up her boy in a log cabin where once the bear looked in at the door, or in the log school-house with its newspaper windows, “slab benches,” and drunken teacher, and could train him for his work of faith and perseverance[Pg 9] in that dreary and forbidding missionary region, and in what men thought that forlorn hope. And he will learn—unless he knew it already—that a lad who in early life hammered on the anvil can strike a strong and steady stroke for God and man.

The reader will also recognize in the “Mary” of this story, now gone to her rest, a worthy pupil of Mary Lyon and Miss Z. P. Grant. With her excellent education, culture, and character, how cheerfully she left her home in Massachusetts to enter almost alone on a field of labor which she knew perfectly to be most fraught with self-sacrifice, least attractive, not to say most repulsive, of them all. How hopefully she journeyed on thirteen days, from the shores of Lake Harriet, to plunge still farther into the wilderness of Lac-qui-parle. How happily she found a “home” for five years in the upper story of Dr. Williamson’s log house, in a room eighteen feet by ten, occupied in due time by three children also. How quietly she glided into all the details and solved all the difficulties of that primitive life, bore with the often revolting habits of the aborigines, taught their boys English, and persevered and persisted till she had taught their women “the gospel of soap.” How bravely she bore up in that terrible midnight flight from Hazelwood, and the long exhausting journey to St. Paul, through the pelting rains and wet swamp-grass, and with murderous savages upon the trail. But it was the chief test and glory of her character to have brought up a family of children, among all the surroundings of Indian life, as though amid the homes of civilization and refinement. All honor to such a woman, wife, and mother. Her children rise up and call her blessed. Forty-one years after her departure from the station at Lake Harriet,[Pg 10] the present writer stood upon the pleasant shore where the tamarack mission houses had long disappeared, and felt that this was consecrated ground.

The other partner in this firm of “Mary and I” needs no words of mine. He speaks here for himself, and his labors speak for him. His Dakota Dictionary and Bible are lasting monuments of his persevering toil, while eleven churches with a dozen native preachers and eight hundred members, and a flourishing Dakota Home Missionary Society, bear witness to the Christian work of himself and his few co-laborers. “Forty Years Among the Sioux,” he writes. “Forty years in the Turkish Empire,” was the story of Dr. Goodell. Fifty Years in Ceylon, was the life-work of Levi Spalding. What records are these of singleness of aim, of energy, of Christian work, and of harvests gathered and gathering for the Master. Would that such a holy ambition might be kindled in the hearts of many other young men as they read these pages. How invigorating the firm assurance: “During the years of my preparation there never came to me a doubt of the rightness of my decision. At the end of forty years’ work I am abundantly satisfied with the way in which the Lord has led me.” How many of those who embark in other lines of life and action can say the same?

And how signally was the spirit of the parents transmitted to the children. Almost a whole family in the mission work: six sons and daughters among the Dakotas, the seventh in China. I know not another instance so marked as this. And what a power for good to the Dakota race, past, present, and future, is gathered up in one undaunted, single-hearted family of Christian toilers. A part of this family it has been the writer’s[Pg 11] privilege to know, and of two of the sons he had the pleasure to be the teacher in the original tongues of the Word of God. And he deems it an additional pleasure and privilege thus to connect his name with theirs and their mission. For not alone the dusky Dakotas, but all the friends of the Indian tribes and lovers of the Missionary cause, are called on to honor the names of Pond, Williamson, and Riggs.

Dartmouth College.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Page | |

| 1837.—Our Parentage.—My Mother’s Bear Story.—Mary’s Education.—Her First School Teaching.—School-houses and Teachers in Ohio.—Learning the Catechism.—Ambitions.—The Lord’s Leading.—Mary’s Teaching in Bethlehem.—Life Threads Coming Together.—Licensure.—Our Decision as to Life Work.—Going to New England.—The Hawley Family.—Marriage.—Going West.—From Mary’s Letters.—Mrs. Isabella Burgess.—“Steamer Isabella.”—At St. Louis.—The Mississippi.—To the City of Lead.—Rev. Aratus Kent.—The Lord Provides.—Mary’s Descriptions.—Upper Mississippi.—Reaching Fort Snelling | 23 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| 1837.—First Knowledge of the Sioux.—Hennepin and Du Luth.—Fort Snelling.—Lakes Harriet and Calhoun.—Three Months at Lake Harriet.—Samuel W. Pond.—Learning the Language.—Mr. Stevens.—Temporary Home.—That Station Soon Broken Up.—Mary’s Letters.—The Mission and People.—Native Customs.—Lord’s Supper.—“Good Voice.”—Description of Our Home.—The Garrison.—Seeing St. Anthony.—Ascent of the St. Peters.—Mary’s Letters.—Traverse des Sioux.—Prairie Travelling.—Reaching Lac-qui-parle.—T. S. Williamson.—A Sabbath Service.—Our Upper Room.—Experiences.—Church at Lac-qui-parle.—Mr. Pond’s Marriage.—Mary’s Letters.—Feast | 38 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| 1837-1839.—The Language.—Its Growth.—System of Notation.—After Changes.—What We Had to Put into the Language.—Teaching English and Teaching Dakota.—Mary’s Letter.—Fort Renville.—Translating the Bible.—The Gospels of Mark and John.—“Good Bird” Born.—Dakota Names.—The Lessons We Learned.—Dakota Washing.—Extracts from Letters.—Dakota Tents.—A Marriage.—Visiting the Village.—Girls, Boys, and Dogs.—G. H. Pond’s Indian Hunt.—Three Families Killed.—The Village Wail.—The Power of a Name.—Post-Office Far Away.—The Coming of the Mail.—S. W. Pond Comes Up.—My Visit to Snelling.—Lost my Horse.—Dr. Williamson Goes to Ohio.—The Spirit’s Presence.—Prayer.—Mary’s Reports | 58 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| 1838-1840.—“Eagle Help.”—His Power as War Prophet.—Makes No-Flight Dance.—We Pray Against It.—Unsuccessful on the War-Path.—Their Revenge.—Jean Nicollet and J. C. Fremont.—Opposition to Schools.—Progress in Teaching.—Method of Counting.—“Lake That Speaks.”—Our Trip to Fort Snelling.—Incidents of the Way.—The Changes There.—Our Return Journey.—Birch-Bark Canoe.—Mary’s Story.—“Le Grand Canoe.”—Baby Born on the Way.—Walking Ten Miles.—Advantages of Travel.—My Visit to the Missouri River.—“Fort Pierre.”—Results | 76 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| 1840-1843.—Dakota Braves.—Simon Anawangmane.—Mary’s Letter.—Simon’s Fall.—Maple Sugar.—Adobe Church.—Catharine’s Letter.—Another Letter of Mary’s.—Left Hand’s Case.—The Fifth Winter.—Mary to Her Brother.—The Children’s Morning Ride.—Visit to Hawley and Ohio.—Dakota Printing.—New Recruits.—Return.—Little Rapids.—Traverse des Sioux.—Stealing Bread.—Forming a New Station.—Begging.—Opposition.—Thomas L. Longley.—Meeting Ojibwas.—Two Sioux Killed.—Mary’s Hard Walk. | 89 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| 1843-1846.—Great Sorrow.—Thomas Drowned.—Mary’s Letter.—The Indians’ Thoughts.—Old Gray-Leaf.—Oxen Killed.—Hard Field.—Sleepy Eyes’ Horse.—Indian in Prison.—The Lord Keeps Us.—Simon’s Shame.—Mary’s Letter.—Robert Hopkins and Agnes.—Le Bland.—White Man Ghost.—Bennett.—Sleepy Eyes’ Camp.—Drunken Indians.—Making Sugar.—Military Company.—Dakota Prisoners.—Stealing Melons.—Preaching and School.—A Canoe Voyage.—Red Wing. | 104 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| 1846-1851.—Returning to Lac-qui-parle.—Reasons Therefor.—Mary’s Story.—“Give Me My Old Seat, Mother.”—At Lac-qui-parle.—New Arrangements.—Better Understanding.—Buffalo Plenty.—Mary’s Story.—Little Samuel Died.—Going on the Hunt.—Vision of Home.—Building House.—Dakota Camp.—Soldier’s Lodge.—Wakanmane’s Village.—Making a Presbytery.—New Recruits.—Meeting at Kaposia.—Mary’s Story.—Varied Trials.—Sabbath Worship.—“What is to Die?”—New Stations.—Making a Treaty.—Mr. Hopkins Drowned.—Personal Experience. | 123 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| 1851-1854.—Grammar and Dictionary.—How It Grew.—Publication.—Minnesota Historical Society.—Smithsonian Institution.—Going East.—Mission Meeting at Traverse des Sioux.—Mrs. Hopkins.—Death’s Doings.—Changes in the Mode of Writing Dakota.—Completed Book.—Growth of the Language.—In Brooklyn and Philadelphia.—The Misses Spooner.—Changes in the Mission.—The Ponds and Others Retire.—Dr. Williamson at Pay-zhe-hoo-ta-ze.—Winter Storms.—Andrew Hunter.—Two Families Left.—Children Learning Dakota.—Our House Burned.—The Lord Provides | 141 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| 1854-1856.—Simon Anawangmane.—Rebuilding after the Fire.—Visit of Secretary Treat.—Change of Plan.—Hazelwood Station.—Circular Saw Mill.—Mission Buildings.—Chapel.—Civilized Community.—Making Citizens.—Boarding-School.—Educating our own Children.—Financial Difficulties.—The Lord Provides.—A Great Affliction.—Smith Burgess Williamson.—“Aunt Jane.”—Bunyan’s Pilgrim in Dakota | 153 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| 1857-1862.—Spirit Lake.—Massacres by Inkpadoota.—The Captives.—Delivery of Mrs. Marble and Miss Gardner.—Excitement.—Inkpadoota’s Son Killed.—United States Soldiers.—Major Sherman.—Indian Councils.—Great Scare.—Going Away.—Indians Sent After Scarlet End.—Quiet Restored.—Children at School.—Quarter-Century Meeting.—John P. Williamson at Red Wood.—Dedication of Chapel | 162 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| 1861-1862.—Republican Administration.—Its Mistakes.—Changing Annuities.—Results.—Returning from General Assembly.—A Marriage in St. Paul.—D. Wilson Moore and Wife.—Delayed Payment.—Difficulty with the Sissetons.—Peace Again.—Recruiting for the Southern War.—Seventeenth of August, 1862.—The Outbreak.—Remembering Christ’s Death.—Massacres Commenced.—Capt. Marsh’s Company.—Our Flight.—Reasons Therefor.—Escape to an Island.—Final Leaving.—A Wounded Man.—Traveling on the Prairie.—Wet Night.—Taking a Picture.—Change of Plan.—Night Travel.—Going Around Fort Ridgely.—Night Scares.—Safe Passage.—Four Men Killed.—The Lord Leads Us.—Sabbath.—Reaching the Settlements.—Mary at St. Anthony | 171 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| 1862.—General Sibley’s Expedition.—I Go as Chaplain.—At Fort Ridgely.—The Burial Party.—Birch Coolie Defeat.—Simon and Lorenzo Bring in Captives.—March to Yellow Medicine.—Battle of Wood Lake.—Indians Flee.—Camp Release.—A Hundred Captives Rescued.—Amos W. Huggins Killed.—We Send for His Wife and Children.—Spirit Walker Has Protected Them.—Martha’s Letter | 188 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| 1862-1863.—Military Commission.—Excited Community.—Dakotas Condemned.—Moving Camp.—The Campaign Closed.—Findings Sent to the President.—Reaching My Home in St. Anthony.—Distributing Alms on the Frontier.—Recalled to Mankato.—The Executions.—Thirty-eight Hanged.—Difficulty of Avoiding Mistakes.—Round Wind.—Confessions.—The Next Sabbath’s Service.—Dr. Williamson’s Work.—Learning to Read.—The Spiritual Awakening.—The Way It Came.—Mr. Pond Invited Up.—Baptisms in the Prison.—The Lord’s Supper.—The Camp at Snelling.—A Like Work of Grace.—John P. Williamson.—Scenes in the Garret.—One Hundred Adults Baptized.—Marvelous in Our Eyes | 206 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| 1863-1866.—The Dakota Prisoners Taken to Davenport.—Camp McClellan.—Their Treatment.—Great Mortality.—Education in Prison.—Worship.—Church Matters.—The Camp at Snelling Removed to Crow Creek.—John P. Williamson’s Story.—Many Die.—Scouts’ Camp.—Visits to Them.—Family Threads.—Revising the New Testament.—Educating Our Children.—Removal to Beloit.—Family Matters.—Little Six and Medicine Bottle.—With the Prisoners at Davenport | 220 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| 1866-1869.—Prisoners Meet their Families at the Niobrara.—Our Summer’s Visitation.—At the Scouts’ Camp.—Crossing the Prairie.—Killing Buffalo.—At Niobrara.—Religious Meetings.—Licensing Natives.—Visiting the Omahas.—Scripture Translating.—Sisseton Treaty at Washington.—Second Visit to the Santees.—Artemas and Titus Ordained.—Crossing to the Head of the Coteau.—Organizing Churches and Licensing Dakotas.—Solomon, Robert, Louis, Daniel.—On Horseback in 1868.—Visit to the Santees, Yanktons, and Brules.—Gathering at Dry Wood.—Solomon Ordained.—Writing “Takoo Wakan.”—Mary’s Sickness.—Grand Hymns.—Going through the Valley of the Shadow.—Death! | 230 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| 1869-1870.—Home Desolate.—At the General Assembly.—Summer Campaign.—A. L. Riggs.—His Story of Early Life.—Inside View of Missions.—Why Missionaries’ Children Become Missionaries.—No Constraint Laid on Them.—A. L. Riggs Visits the Missouri Sioux.—Up the River.—The Brules.—Cheyenne and Grand River.—Starting for Fort Wadsworth.—Sun Eclipsed.—Sisseton Reserve.—Deciding to Build There.—In the Autumn Assembly.—My Mother’s Home.—Winter Visit to Santee.—Julia La Framboise | 244 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| 1870-1871.—Beloit Home Broken Up.—Building on the Sisseton Reserve.—Difficulties and Cost.—Correspondence with Washington.—Order to Suspend Work.—Disregarding the Taboo.—Anna Sick at Beloit.—Assurance.—Martha Goes in Anna’s Place.—The Dakota Churches.—Lac-qui-parle, Ascension.—John B. Renville.—Daniel Renville.—Houses of Worship.—Eight Churches.—The “Word Carrier.”—Annual Meeting on the Big Sioux.—Homestead Colony.—How it Came about.—Joseph Iron Old Man.—Perished in a Snow Storm.—The Dakota Mission Divides.—Reasons Therefor | 256 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| 1870-1873.—A. L. Riggs Builds at Santee.—The Santee High School.—Visit to Fort Sully.—Change of Agents at Sisseton.—Second Marriage.—Annual Meeting at Good Will.—Grand Gathering.—New Treaty Made at Sisseton.—Nina Foster Riggs.—Our Trip to Fort Sully.—An Incident by the Way.—Stop at Santee.—Pastor Ehnamane.—His Deer Hunt.—Annual Meeting in 1873.—Rev. S. J. Humphrey’s Visit.—Mr. Humphrey’s Sketch.—Where They Come From.—Morning Call.—Visiting the Teepees.—The Religious Gathering.—The Moderator.—Questions Discussed.—The Personnel.—Putting up a Tent.—Sabbath Service.—Mission Reunion. | 270 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| 1873-1874.—The American Board at Minneapolis.—The Nidus of the Dakota Mission.—Large Indian Delegation.—Ehnamane and Mazakootemane.—“Then and Now.”—The Woman’s Meeting.—Nina Foster Riggs and Lizzie Bishop.—Miss Bishop’s Work and Early Death.—Manual Labor Boarding-School at Sisseton.—Building Dedicated.—M. N. Adams, Agent.—School Opened.—Mrs. Armor and Mrs. Morris.—“My Darling in God’s Garden.”—Visit to Fort Berthold.—Mandans, Rees, and Hidatsa.—Dr. W. Matthews’ Hidatsa Grammar.—Beliefs.—Missionary Interest in Berthold.—Down the Missouri.—Annual Meeting at Santee.—Normal School.—Dakotas Build a Church at Ascension.—Journey to the Ojibwas with E. P. Wheeler.—Leech Lake and Red Lake.—On the Gitche Gumme.—“The Stoneys.”—Visit to Odanah.—Hope for Ojibwas | 288 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| 1875-1876.—Annual Meeting of 1875.—Homestead Settlement on the Big Sioux.—Interest of the Conference.—Iapi Oaye.—Inception of Native Missionary Work.—Theological Class.—The Dakota Home.—Charles L. Hall Ordained.—Dr. Magoun of Iowa.—Mr. and Mrs. Hall Sent to Berthold by the American Board.—The Word Carrier’s Good Words to Them.—The Conference of 1876.—In J. B. Renville’s Church.—Coming to the Meeting from Sully.—Miss Whipple’s Story.—“Dakota Missionary Society.”—Miss Collins’ Story.—Impressions of the Meeting | 308 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| 1871-1877.—The Wilder Sioux.—Gradual Openings.—Thomas Lawrence.—Visit to the Land of the Teetons.—Fort Sully.—Hope Station.—Mrs. General Stanley in the Evangelist.—Work by Native Teachers.—Thomas Married to Nina Foster.—Nina’s First Visit to Sully.—Attending the Conference and American Board.—Miss Collins and Miss Whipple.—Bogue Station.—The Mission Surroundings.—Chapel Built.—Mission Work.—Church Organized.—Sioux War of 1876.—Community Excited.—Schools.—“Waiting for a Boat.”—Miss Whipple Dies at Chicago.—Mrs. Nina Riggs’ Tribute.—The Conference of 1877 at Sully.—Questions Discussed.—Grand Impressions | 325 |

MONOGRAPHS.

| Mrs. Nina Foster Riggs | 345 |

| Rev. Gideon H. Pond | 361 |

| Solomon | 374 |

| Dr. T. S. Williamson | 382 |

| A Memorial | 399 |

| The Family Reunion | 408 |

MARY AND I.

FORTY YEARS WITH THE SIOUX.

1837.—Our Parentage.—My Mother’s Bear Story.—Mary’s Education.—Her First School Teaching.—School-houses and Teachers in Ohio.—Learning the Catechism.—Ambitions.—The Lord’s Leading.—Mary’s Teaching in Bethlehem.—Life Threads Coming Together.—Licensure.—Our Decision as to Life Work.—Going to New England.—The Hawley Family.—Marriage.—Going West.—From Mary’s Letters.—Mrs. Isabella Burgess.—“Steamer Isabella.”—At St. Louis.—The Mississippi.—To the City of Lead.—Rev. Aratus Kent.—The Lord Provides.—Mary’s Descriptions.—Upper Mississippi.—Reaching Fort Snelling.

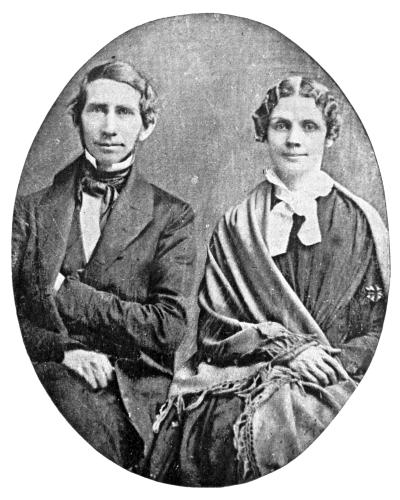

Forty years ago this first day of June, 1877, Mary and I came to Fort

Snelling. She was from the Old Bay State, and I was a native-born

Buckeye. Her ancestors were the Longleys and Taylors of Hawley and

Buckland, names honorable and honored in the western part of

Massachusetts. Her father, Gen. Thomas Longley, was for many years a

member of the General Court and had served in the war of 1812, while

her grandfather, Col. Edmund Longley, had been a soldier of the

Revolution, and had served under Washington. Her maternal grandfather,

Taylor, had held a civil commission under[Pg 23]

[Pg 24] George the Third. In an

early day both families had settled in the hill country west of the

Connecticut River. They were the true and worthy representatives of

New England.

As it regards myself, my father, whose name was Stephen Riggs, was a blacksmith, and for many years an elder in the Presbyterian church of Steubenville, Ohio, where I was born. He had a brother, Cyrus, who was a preacher in Western Pennsylvania; and he traced his lineage back, through the Riggs families of New Jersey, a long line of godly men, ministers of the gospel and others, to Edward Riggs,[1] who came over from Wales in the first days of colonial history. My mother was Anna Baird, a model Christian woman—as I think, of a Scotch Irish family, which in the early days settled in Fayette County, Pa. Of necessity they were pioneers. When they had three children, they removed up into the wild wooded country of the Upper Alleghany. My mother could tell a good many bear stories. At one time she and those first three children were left alone in an unfinished log cabin. The father was away hunting food for the family. When, at night, the fire was burning in the old-fashioned chimney, a large black bear pushed aside the quilt that served for the door, and, sitting down on his haunches, surveyed the scared family within. But, as God would have it, to their great relief, he retired without offering them any violence.

[1] Heretofore, we have supposed the first progenitor of the Riggs Family in America was Miles; but the investigations of Mr. J. H. Wallace of New York show that it was Edward, who settled in Roxbury, Mass., about the year 1635. The name of Miles comes in later. He was the progenitor of one branch of the family.

Mary’s education had been carefully conducted. She had not only the advantages of the common town school and home culture, but was a pupil of Mary Lyon, when she taught in Buckland, and afterward of Miss Grant, at Ipswich. At the age of sixteen she taught her first school, in Williamstown, Mass. As she used to tell the story, she taught for a dollar a week, and, at the end of her first quarter, brought the $12 home and gave it to her father, as a recognition of what he had expended for her education.

It was a joy to me to meet, the other day in Chicago, Mrs. Judge Osborne, who was one of the scholars in this school, as it was in her father’s family; and who spoke very affectionately of Mary Ann Longley, her teacher.

Contrasted with the present appliances for education in all the towns, and many of the country districts also, the common schools in Ohio, when I was a boy, were very poorly equipped. My first school-house was a log cabin, with a large open fireplace, a window with four lights of glass where the master’s seat was, while on the other two sides a log was cut out and old newspapers pasted over the hole through which the light was supposed to come, and the seats were benches made of slabs. One of my first teachers was a drunken Irishman, who often visited the tavern near by and came back to sleep the greater part of the afternoon. This gave us a long play spell. But he was a terrible master for the remainder of the day. Notwithstanding these difficulties in the way of education, we managed to learn a good deal. Sabbath-schools had not reached the efficiency they now have; but we children were taught carefully at home. We were obliged to commit to memory the[Pg 26] Shorter Catechism, and every few months the good minister came around to see how well we could repeat it. All through my life this summary of Christian doctrine—not perfect indeed, and not to be quoted as authority equal to the Scriptures, as it sometimes is—has been to me of incalculable advantage. What I understood not then I have come to understand better since, with the opening of the Word and the illumination of the Holy Spirit. If I were a boy again, I would learn the Shorter Catechism.

My ambition was to learn some kind of a trade. But I had wrought enough with my father at the anvil not to choose that. It was hard work, and not over-clean work. Something else would suit me better, I thought. About that time my sister Harriet married William McLaughlin, who was a well-to-do harness-maker in Steubenville. This suited my ideas of life better. But that sister died soon after her marriage, and my father removed from that part of the country to the southern part of the State. There in Ripley a Latin school was opened about that time, and the Lord appeared to me in a wonderful manner, making discoveries of himself to my spiritual apprehension, so that from that time and onward my path lay in the line of preparation for such service as he should call me unto. My father, as he said many years afterward, had intended to educate my younger brother James; but he was taken away suddenly, and I came in his place. Thus the Lord opened the way for a commencement, and by the help of friends I was enabled to continue until I finished the course at Jefferson College, and afterward spent a year at the Western Theological Seminary at Alleghany.

Mary had been educated for a teacher. She was well[Pg 27] fitted for the work. And while she was still at Ipswich, a benevolent gentleman in New York City, who had interested himself in establishing a seminary in Southern Indiana, sent to Miss Grant for a teacher to take charge of the school near Bethlehem, in the family of Rev. John M. Dickey. It was far away, but it seemed just the opening she had been desiring. But a young woman needed company in travelling so far westward. It was at the time of the May meetings in New York. Clergymen and others were on East from various parts of the West. In several instances, however, she failed of the company she hoped for, by what seemed singular providences. And at last it was her lot to come West under the protection of Rev. Dyer Burgess, of West Union, Ohio. Mr. Burgess was what was called in those days “a rabid abolitionist,” and had taken a fancy to help me along, because, as he said, I was “of the same craft.” And so it was that during his absence I was living in his family. This is the way in which the threads of our two lives, Mary’s and mine, were brought together. A year and a half after this I was licensed to preach the gospel by the Chillicothe Presbytery, and we were on our way to her mountain home in Massachusetts.

Before starting for New England, the general plan of our life-work was arranged. Early in my course of education, I had considered the claims of the heathen upon us Christians, and upon myself personally as a believer in Christ; and, with very little hesitation or delay, the decision had been reached that, God willing, I would go somewhere among the unevangelized. And, during the years of my preparation, there never came to me a doubt of the rightness of my decision. Nay, more, at the end of forty years’ work, I am abundantly satisfied[Pg 28] with the way in which the Lord has led me. If China had been then open to the gospel, as it was twenty years afterward, I probably should have elected to go there. But Dr. Thomas S. Williamson of Ripley, Ohio, had started for the Dakota field the same year that I graduated from college. His representations of the needs of these aborigines, and the starting out of Whitman and Spalding with their wives to the Indians of the Pacific coast, attracted me to the westward. And Mary was quite willing, if not enthusiastic, to commence a life-work among the Indians of the North-west, which at that time involved more of sacrifice than service in many a far-off foreign field. Hitherto, the evangelization of our own North American Indians had been, and still is, in most parts of the field, essentially a foreign mission work. It has differed little, except, perhaps, in the element of greater self-sacrifice, from the work in India, China, or Japan. And so, with a mutual good understanding of the general plan of life’s campaign, with very little appreciation of what its difficulties might be, but with a good faith in ourselves, and more faith in Him who has said, “Lo, I am with you all days,” Mary left her school in Bethlehem, to which she had become a felt necessity, and I gathered up such credentials as were necessary to the consummation of our acceptance as missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and we went eastward.

Railroads had hardly been thought of in those days, and so what part of the way we were not carried by steamboats, we rode in stages. It was only the day before Thanksgiving, and a stormy evening it was, when we hired a very ordinary one-horse wagon to carry us and our baggage from Charlemont up to Hawley. I need[Pg 29] not say that in the old house at home the sister and the daughter and granddaughter found a warm reception, and I, the western stranger, was not long overlooked. It was indeed a special Thanksgiving and time of family rejoicing, when the married sister and her family were gathered, with the brothers, Alfred and Moses and Thomas and Joseph, and the little sister Henrietta, and the parents and grandparents, then still living. Since that time, one by one, they have gone to the beautiful land above, and only two remain.

Well, the winter, with its terrible storms and deep snows, soon passed by. It was all too short for Mary’s preparation. I found work waiting for me in preaching to the little church in West Hawley. They were a primitive people, with but little of what is called wealth, but with generous hearts; and the three months I spent with them were profitable to me.

On the 16th of February, 1837, there was a great gathering in the old meeting-house on the hill; and, after the service was over, Mary and I received the congratulations of hosts of friends. Soon after this the time of our departure came. The snow-drifts were still deep on the hills when, in the first days of March, we commenced our hegira to the far West. It was a long and toilsome journey—all the way to New York City by stage, and then again from Philadelphia across the mountains to Pittsburg in the same manner, through the March rains and mud, we travelled on, day and night. It was quite a relief to sleep and glide down the beautiful Ohio on a steamer. And there we found friends in Portsmouth and Ripley and West Union, with whom we rested, and by whom we were refreshed, and who greatly forwarded our preparations for life among the Indians.

Of the journey Mary wrote, under date City of Penn, March 3, 1837: “We were surprised to find sleighing here, when there was little at Hartford and none at New Haven and New York. We expect to spend the Sabbath here; and may the Lord bless the detention to ourselves and others. Oh, for a heart more engaged to labor by the way—to labor any and everywhere.”

In West Union, Ohio, she writes from Anti-Slavery Palace, April 5: “Brother Joseph Riggs made us some valuable presents. His kindness supplied my lack of a good English merino, and Sister Riggs had prepared her donation and laid it by, as the Apostle directs,—one pair of warm blankets, sheets and pillow-cases. My new nieces also seemed to partake of the same kind spirit, and gave us valuable mementos of their affection.

“We found Mrs. Burgess not behind, and perhaps before most of our friends, in her plans and gifts. Besides a cooking-stove and furniture, she has provided a fine blanket and comforter, sheets, pillow-cases, towels, dried peaches, etc. Perhaps you will fear that with so many kind friends we shall be furnished with too many comforts. Pray, then, that we may be kept very humble, and receive these blessings thankfully from the Giver of every good and perfect gift.”

Mrs. Isabella Burgess, the wife of my friend Rev. Dyer Burgess, we put into lasting remembrance by the name we gave to our first daughter, who is now living by the great wall of China. By and by we found ourselves furnished with such things as we supposed we should need for a year to come, and we bade adieu to our Ohio friends, and embarked at Cincinnati for St. Louis.

“Steamer Isabella, Thursday Eve, May 4.

“We have been highly favored thus far on our way down the Ohio. We took a last look of Indiana about noon, and saw the waters of the separating Wabash join those of the Ohio, and yet flow on without commingling for ten or twelve miles, marking their course by their blue tint and purer shade. The banks are much lower here than nearer the source, sometimes gently sloping to the water’s edge, and bearing such marks of inundation as trunks and roots of trees half imbedded in the sand, or cast higher up on the shore. At intervals we passed some beautiful bluffs, not very high, but very verdant, and others more precipitous. Bold, craggy rocks, with evergreen-tufted tops, and a few dwarf stragglers on their sides. One of them contained a cave, apparently dark enough for deeds of darkest hue, and probably it may have witnessed many perpetrated by those daring bandits that prowled about these bluffs during the early settlement of Illinois.

“Friday Eve.—This morning, when we awoke, we found ourselves in the muddy waters of the broad Mississippi. They are quite as muddy as those of a shallow pond after a severe shower. We drink it, however, and find the taste not quite as unpleasant as one might suppose from its color, though quite warm. The river is very wide here, and beautifully spotted with large islands. Their sandy points, the muddy waters, and abounding snags render navigation more dangerous than on the Ohio. We have met with no accident yet, and I am unconscious of fear. I desire to trust in Him who rules the water as well as the lands.”

“St. Louis, May 8, 1837.

“Had you been with us this morning, you would have sympathized with us in what seemed to be a detention in the journey to our distant unfound home in the wilderness, when we heard that the Fur Company’s boat left for Fort Snelling last week. You can imagine our feelings, our doubts, our hopes, our fears rushing to our hearts, but soon quieted with the conviction that the Lord would guide us in his own time to the field where he would have us labor. We feel that we have done all in our power to hasten on our journey and to gain information in reference to the time of leaving this city. Having endeavored to do this, we have desired to leave the event with God, and he will still direct. We now have some ground for hope that another boat will ascend the river in a week or two, and, if so, we shall avail ourselves of the opportunity. Till we learn something more definitely in regard to it, we shall remain at Alton, if we are prospered in reaching there.”

In those days the Upper Mississippi was still a wild and almost uninhabited region. Such places as Davenport and Rock Island, which now together form a large centre of population, had then, all told, only about a dozen houses. The lead mines of Galena and Dubuque had gathered in somewhat larger settlements. Above them there was nothing but Indians and military. So that a steamer starting for Fort Snelling was a rare thing. It was said that less than half a dozen in a season reached that point. Indeed, there was nothing to carry up but goods for the Indian trade, and army supplies. Some friends at Alton invited us to come and spend the intervening time. There we were kindly entertained in the[Pg 33] family of Mr. Winthrop S. Gilman, who has since been one of the substantial Christian business men in New York City. On our leaving, Mr. Gilman bade us “look upward,” which has ever been one of our life mottoes.

At that time, a steamer from St. Louis required at least two full weeks to reach Fort Snelling. It was an object with us not to travel on the Sabbath, if possible. So we planned to go up beforehand, and take the up-river boat at the highest point. It might be, we thought, that the Lord would arrange things for us so that we should reach our mission field without travelling on the Day of Rest. With this desire we embarked for Galena. But Saturday night found us passing along by the beautiful country of Rock Island and Davenport. In the latter place Mary and I spent a Sabbath, and worshipped with a few of the pioneer people who gathered in a school-house. By the middle of the next week we had reached the city of lead. There we found the man who had said to the Home Missionary Society, “If you have a place so difficult that no one wants to go to it, send me there.” And they sent the veteran, Rev. Aratus Kent, to Galena, Illinois.

Some of the scenes and events connected with our ascent of the Mississippi are graphically described by Mary’s facile pen:

“Steamboat Olive Branch, May 17.

“We are now on our way to Galena, where we shall probably take a boat for St. Peters. We pursue this course, though it subjects us to the inconvenience of changing boats, that we may be able to avoid Sabbath travelling, if possible. One Sabbath at least will be rescued in this way, as the Pavilion, the only boat for [Pg 34]St. Peters at present, leaves St. Louis on Sunday! This we felt would not be right for us, consequently we left Alton to-day, trusting that the Lord of the Sabbath would speed us on our journey of 3000 miles, and enable us to keep his Sabbath holy unto the end thereof.

“Of the scenery we have passed this afternoon, and are still passing, I can give you no just conceptions. It beggars description, and yet I wish you could imagine the Illinois semi-circular shores lined with high rocks, embosomed by trees of most delicate green, and crowned with a grassy mound of the same tint, or rising more perpendicularly and towering more loftily in solid columns, defying art to form or demolish works so impregnable, and at the same time so grand and beautiful. I have just been gazing at these everlasting rocks mellowed by the soft twilight. A bend in the river and an island made them apparently meet the opposite shore. The departing light of day favored the illusion of a splendid city reaching for miles along the river, built of granite and marble, and shaded by luxuriant groves, all reflected in the quiet waters. This river bears very little resemblance to itself (as geographies name it) after its junction with the Missouri. To me it seems a misnomer to name a river from a branch which is so dissimilar. The waters here are comparatively pure and the current mild. Below, they are turbid and impetuous, rolling on in their power, and sweeping all in their pathway onward at the rate of five or six miles an hour.

“Just below the junction we were astonished and amused to see large spots of muddy water surrounded by those of a purer shade, as if they would retain their distinctive character to the last; but in vain, for the lesser was contaminated and swallowed up by the greater.[Pg 35] I might moralize on this, but will leave each one to draw his own inferences.”

“Stephenson (now Davenport), May 22.

“We left the Olive Branch between 10 and 11 on Saturday night. The lateness of the hour obliged us to accept of such accommodations as presented themselves first, and even made us thankful for them, though they were the most wretched I ever endured. I do not allude to the house or table, though little or nothing could be said in their praise, but to the horrid profanity. Connected with the house and adjoining our room was a grocery, a devil’s den indeed, and so often were the frequent volleys of dreadful oaths that our hearts grew sick, and we shuddered and sought to shut our ears. Notwithstanding all this, we were happier than if we had been travelling on God’s holy day. Our consciences approved resting according to the commandment, though they did not chide for removing, even on the Sabbath, to a house where God’s name is not used so irreverently—so profanely.”

“Galena, May 23.

“This place, wild and hilly, we reached this afternoon, and have been very kindly received by some Yankee Christian friends, where we feel ourselves quite at home, though only inmates of this hospitable mansion a few hours. Surely the Lord has blessed us above measure in providing warm Christian hearts to receive us. Mr. and Mrs. Fuller, where we are, supply the place of the Gilmans of Alton. We hope to leave in a day or two for Fort Snelling.”

“Galena, Ill., May 25, 1837.

“A kind Providence has so ordered our affairs that we are detained here still, and I hope our stay may promote[Pg 36] the best interests of the mission. It seems desirable that Christians in these villages of the Upper Mississippi should become interested in the missionaries and the missions among the northern Indians, that their prejudices may be overcome and their hearts made to feel the claims those dark tribes have upon their sympathies, their charities, and their prayers.”

“Steamer Pavilion, Upper Mississippi, May 31.

“We are this evening (Wednesday) more than 100 miles above Prairie du Chien, on our way to St. Peters, which we hope to reach before the close of the week, that we may be able to keep the Sabbath on shore. You will rejoice with us that we have been able, in all our journey of 3000 miles, to rest from travelling on the Sabbath. Last Saturday, however, our principles and feelings were tried by this boat, for which we had waited three weeks, and watched anxiously for the last few days, fearing it would subject us to Sabbath travelling. Saturday eve, after sunset, when our wishes had led us to believe it would not leave, if it should reach Galena until Monday, we heard a boat, and soon our sight confirmed our ears. Mr. Riggs hastened on board and ascertained from the captain that he should leave Sabbath morning. The inquiry was, shall we break one command in fulfilling another? We soon decided that it was not our duty to commence a journey under these circumstances even, and retired to rest, confident the Lord would provide for us. Notwithstanding our prospects were rather dark, I felt a secret hope that the Lord would detain the Pavilion until Monday. If I had any faith it was very weak, for I felt deeply conscious we were entirely undeserving such a favor. But judge of[Pg 37] our happy surprise, morning and afternoon, on our way to and from church, to find the Pavilion still at the wharf. We felt that it was truly a gracious providence. On Monday morning we came on board.”

This week on the Upper Mississippi was one of quiet joy. We had been nearly three months on our way from Mary’s home in Massachusetts. God had prospered us all the way. Wherever we had stopped we had found or made friends. The Lord, as we believed, had signally interfered in our behalf, and helped us to “remember the Sabbath day,” and to give our testimony to its sacred observance. The season of the year was inspiring. A resurrection to new life had just taken place. All external nature had put on her beautiful garments. And day after day—for the boat tied up at night—we found ourselves passing by those grand old hills and wonderful escarpments of the Upper Mississippi. We were in the wilds of the West, beyond the cabins of the pioneer. We were passing the battle-fields of Indian story. Nay, more, we were already in the land of the Dakotas, and passing by the teepees and the villages of the red man, for whose enlightenment and elevation we had left friends and home. Was it strange that this was a week of intense enjoyment, of education, of growth in the life of faith and hope? And so, as I said in the beginning, on the first day of June, 1837, Mary and I reached, in safety, the mouth of the Minnesota, in the land of the Dakotas.

1837.—First Knowledge of the Sioux.—Hennepin and Du Luth.—Fort Snelling.—Lakes Harriet and Calhoun.—Three Months at Lake Harriet.—Samuel W. Pond.—Learning the Language.—Mr. Stevens.—Temporary Home.—That Station Soon Broken Up.—Mary’s Letters.—The Mission and People. Native Customs.—Lord’s Supper.—“Good Voice.”—Description of Our Home.—The Garrison.—Seeing St. Anthony.—Ascent of the St. Peters.—Mary’s Letters.—Traverse des Sioux.—Prairie Travelling.—Reaching Lac-qui-parle.—T. S. Williamson.—A Sabbath Service.—Our Upper Room Experiences.—Church at Lac-qui-parle.—Mr. Pond’s Marriage.—Mary’s Letters.—Feast.

About two hundred and forty years ago, the French voyagers and fur traders, as they came from Nouvelle, France, up the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes, began to hear, from Indians farther east, of a great and warlike people, whom they called Nadouwe or Nadowaessi, enemies. Coming nearer to them, both trader and priest met, at the head of Lake Superior, representatives of this nation, “numerous and fierce, always at war with other tribes, pushing northward and southward and westward,” so that they were sometimes called the “Iroquois of the West.”

But really not much was known of the Sioux until the summer of 1680, when Hennepin and Du Luth met in a camp of Dakotas, as they hunted buffalo in what is now north-western Wisconsin. Hennepin had been captured by a war-party, which descended the Father of Waters in[Pg 39] their canoes, seeking for scalps among their enemies, the Miamis and Illinois. They took him and his companions of the voyage up to their villages on the head-waters of Rum River, and around the shores of Mille Lac and Knife Lake. From the former of these the eastern band of the Sioux nation named themselves Mdaywakantonwan, Spirit Lake Villagers; and from the latter they inherited the name of Santees (Isanyati), Dwellers on Knife.

These two representative Frenchmen, thus brought together, at so early a day, in the wilds of the West, visited the home of the Sioux, as above indicated, and to them we are indebted for much of what we know of the Dakotas two centuries ago.

The Ojibwas and Hurons were then occupying the southern shores of Lake Superior, and, coming first into communication with the white race, they were first supplied with fire-arms, which gave them such an advantage over the more warlike Sioux that, in the next hundred years, we find the Ojibwas in possession of all the country on the head-waters of the Mississippi, while the Dakotas had migrated southward and westward.

The general enlistment of the Sioux, and indeed of all these tribes of the North-west, on the side of the British in the war of 1812, showed the necessity of a strong military garrison in the heart of the Indian country. Hence the building of Fort Snelling nearly sixty years ago. At the confluence of the Minnesota with the Mississippi, and on the high point between the two it has an admirable outlook. So it seemed to us as we approached it on that first day of June, 1837. On our landing we became the guests of Lieutenant Ogden and his excellent wife, who was the daughter of Major Loomis. To Mary and me, every thing was new and strange. We knew[Pg 40] nothing of military life. But our sojourn of a few days was made pleasant and profitable by the Christian sympathy which met us there—the evidence of the Spirit’s presence, which, two years before, had culminated in the organization of a Christian church in the garrison, on the arrival of the first missionaries to the Dakotas.

The Falls of St. Anthony and the beautiful Minnehaha have now become historic, and Minnetonka has become a place of summer resort. But forty years ago it was only now and then that the eyes of a white man, and still more rarely the eyes of a white woman, looked upon the Falls of Curling Water;[2] and scarcely any one knew that the water in Little Falls Creek came from Minnetonka Lake. But nearer by were the beautiful lakes Calhoun and Harriet. On the first of these was the Dakota Village, of which Claudman and Drifter were then the chiefs; and on whose banks the brothers Pond had erected the first white man’s cabin; and on the north bank of the latter was a mission station of the American Board, commenced two years before by Rev. Jedediah D. Stevens.

[2] Minnehaha means “Curling Water,” not “Laughing Water,” as many suppose.

Here we were in daily contact with the Dakota men, women, and children. Here we began to listen to the strange sounds of the Dakota tongue; and here we made our first laughable efforts in speaking the language.

We were fortunate in meeting here Rev. Samuel W. Pond, the older of the brothers, who had come out from Connecticut three years previous, and, in advance of all others, had erected their missionary cabin on the margin of Lake Calhoun. Mr. Pond’s knowledge of Dakota was [Pg 41]quite a help to us, who were just commencing to learn it. Before we left the States, it had been impressed upon us by Secretary David Greene that whether we were successful missionaries or not depended much on our acquiring a free use of the language. And the teaching of my own experience and observation is that if one fails to make a pretty good start the first year in its acquisition, it will be a rare thing if he ever masters the language. And so, obedient to our instructions, we made it our first work to get our ears opened to the strange sounds, and our tongues made cunning for their utterance. Oftentimes we laughed at our own blunders, as when I told Mary, one day, that pish was the Dakota for fish. A Dakota boy had been trying to speak the English word. Mr. Stevens had gathered, from various sources, a vocabulary of five or six hundred words. This formed the commencement of the growth of the Dakota Grammar and Dictionary which I published fifteen years afterward.

Mr. and Mrs. Stevens were from Central New York, and were engaged as early as 1827 in missionary labors on the Island of Mackinaw. In 1829, Mr. Stevens and Rev. Mr. Coe made a tour of exploration through the wilds of Northern Wisconsin, coming as far as Fort Snelling. For several years thereafter, Mr. Stevens was connected with the Stockbridge mission on Fox Lake; and in the summer of 1835 he had commenced this station at Lake Harriet. At the time of our arrival he had made things look quite civilized. He had built two houses of tamarack logs, the larger of which his own family occupied; the lower part of the other was used for the school and religious meetings. Half a dozen boarding scholars, chiefly half-breed girls, formed the nucleus[Pg 42] of the school, which was taught by his niece, Miss Lucy C. Stevens, who was afterward married to Rev. Daniel Gavan, of the Swiss mission to the Dakotas.

As the mission family was already quite large enough for comfort, Mary and I, not wishing to add to any one’s burdens, undertook to make ourselves comfortable in a part of the school-building. Our stay there was to be only temporary, and hence it was only needful that we take care of ourselves, and give such occasional help in the way of English preaching and otherwise as we could. The Dakotas did not yet care to hear the gospel. The Messrs. Pond had succeeded in teaching one young man to read and write, and occasionally a few could be induced to come and listen to the good news. It was seed-sowing time. Many seeds fell by the wayside or on the hard path of sin. Most fell among thorns. But some found good ground, and, lying dormant a full quarter of a century, then sprang up and fruited in the prison at Mankato. Also of the girls in that first Dakota boarding-school quite a good proportion became Christian women and the mothers of Christian families.

But the mission at Lake Harriet was not to continue long. In less than two years from the time we were there, two Ojibwa young men avenged the killing of their father by waylaying and killing a prominent man of the Lake Calhoun Village. A thousand Ojibwas had just left Fort Snelling to return to their homes by way of Lake St. Croix and the Rum River. Both parties were followed by the Sioux, and terrible slaughter ensued. But the result of their splendid victory was that the Lake Calhoun people were afraid to live there any longer, and so they abandoned their village and plantings and settled on the banks of the Minnesota.

During our three months’ stay at Lake Harriet, every thing we saw and heard was fresh and interesting, and Mary could not help telling of them to her friends in Hawley. The grandfather was ninety years old, to whom she thus wrote:—

“Lake Harriet, June 22, 1837.

“We are now on missionary ground, and are surrounded by those dark people of whom we often talked at your fireside last winter. I doubt not you will still think and talk about them, and pray for them also. And surely your grandchildren will not be forgotten.

“We reached this station two weeks since, after enjoying Lieutenant Ogden’s hospitality a few days, and were kindly welcomed by Mr. Stevens’ family, with whom we remain until a house, now occupied by the school, can be prepared, so that we can live in a part of it. Then we shall feel still more at home, though I hope our rude habitation will remind us that we are pilgrims on our way to a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.

“The situation of the mission houses is very beautiful,—on a little eminence, just upon the shore of a lovely lake skirted with trees. About a mile north of us is Lake Calhoun, on the margin of which is an Indian village of about twenty lodges. Most of these are bark houses, some of which are twenty feet square, and others are tents, of skin or cloth. Several days since I walked over to the village, and called at the house of one of the chiefs. He was not at home, but his daughters smiled very good-naturedly upon us. We seated ourselves on a frame extending on three sides of the house, covered with skins, which was all the bed, sofa, and chairs they had.

“Since our visit at the village, two old chiefs have called upon us. One said, this was a very bad country,—ours was a good country,—we had left a good country, and come to live in his bad country, and he was glad. The other called on Sabbath evening, when Mr. Riggs was at the Fort, where he preaches occasionally. He inquired politely how I liked the country, and said it was bad. What could a courtier have said more?

“The Indians come here at all hours of the day without ceremony, sometimes dressed and painted very fantastically, and again with scarcely any clothing. One came in yesterday dressed in a coat, calico shirt, and cloth leggins, the only one I have seen with a coat, excepting two boys who were in the family when we came. The most singular ornament I have seen was a large striped snake, fastened among the painted hair, feathers, and ribbons of an Indian’s head-dress, in such a manner that it could coil round in front and dart out its snake head, or creep down upon the back at pleasure. During this the Indian sat perfectly at ease, apparently much pleased at the astonishment and fear manifested by some of the family.”

“June 26.

“Yesterday Mr. Riggs and myself commemorated a Saviour’s love for the first time on missionary ground. The season was one of precious interest, sitting down at Jesus’ table with a little band of brothers and sisters, one of whom was a Chippewa convert, who accompanied Mr. Ayer from Pokeguma. One of the Methodist missionaries, Mr. King, with a colored man, and the members of the church from the Fort and the mission, completed our band of fifteen. Two of these were received on this occasion. Several Sioux were present, and gazed on the[Pg 45] strange scene before them. A medicine man, Howashta by name, was present, with a long pole in his hand, having his head decked with a stuffed bird of brilliant plumage, and the tail of another of dark brown. His name means ‘Good Voice,’ and he is building him a log house not far from the mission. If he could be brought into the fold of the Kind Shepherd, and become a humble and devoted follower of Jesus, he might be instrumental of great good to his people. He might indeed be a Good Voice bringing glad tidings to their dark souls.”

TO HER MOTHER.

“Home, July 8, 1837.

“Would that you could look in upon us; but as you can not, I will try and give you some idea of our home. The building fronts the lake, but our part opens upon the woodland back of its western shore. The lower room has a small cooking-stove, given us by Mrs. Burgess, a few chairs and a small table, a box and barrel containing dishes, etc., a small will-be pantry, when completed, under the stairs, filled with flour, corn-meal, beans, and stove furniture. Our chamber is low, and nearly filled by a bed, a small bureau and stand, a table for writing, made of a box, and the rest of our half-dozen chairs and one rocking-chair, cushioned by my mother’s kind forethought.

“The rough, loose boards in the chamber are covered with a coarse and cheap hair-and-tow carpeting, to save labor. The floor below will require some cleaning, but I shall not try to keep it white. I have succeeded very well, according to my judgment, in household affairs,—that is, very well for me.

“Some Indian women came in yesterday bringing strawberries, which I purchased with beans. Poor crea[Pg 46]tures, they have very little food of any kind at this season of the year, and we feel it difficult to know how much it is our duty to give them.

“We are not troubled with all the insects which used to annoy me in Indiana, but the mosquitoes are far more abundant. At dark, swarms fill our room, deafen our ears, and irritate our skin. For the last two evenings we have filled our house with smoke, almost to suffocation, to disperse these our officious visitors.”

“July 31.

“Until my location here, I was not aware that it was so exceedingly common for officers in the army to have two wives or more,—but one, of course, legally so. For instance, at the Fort, before the removal of the last troops, there were but two officers who were not known to have an Indian woman, if not half-Indian children. You remember I used to cherish some partiality for the military, but I must confess the last vestige of it has departed. I am not now thinking of its connection with the Peace question, but with that of moral reform. Once, in my childhood’s simplicity, I regarded the army and its discipline as a school for gentlemanly manners, but now it seems a sink of iniquity, a school of vice.”

With the month of September came the time of our departure for Lac-qui-parle. But Mary had not yet seen the Falls of St. Anthony. And so we harnessed up a horse and cart, and had a pleasant ride across the prairie to the government saw-mill, which, with a small dwelling for the soldier occupant, was then the only sign of civilization on the present site of Minneapolis. Then we had our household goods packed up and put on board Mr. Prescott’s Mackinaw boat, to be carried up to Traverse[Pg 47] des Sioux. Mr. Prescott was a white man with a Dakota wife, and had been for years engaged in the fur trade. He had on board his winter outfit. Mary and I took passage with him and his family, and spent a week of new life on what was then called the Saint Peter’s River. The days were very enjoyable, and the nights were quite comfortable, for we had all the advantages of Mr. Prescott’s tent and conveniences for camp life. His propelling force was the muscles of five Frenchmen, who worked the oars and the poles, sometimes paddling and sometimes pushing, and often, in the upper part of the voyage, wading to find the best channel over a sand-bar. But they enjoyed their work, and sang songs by the way.

FROM MARY’S LETTERS

“Sept. 2, 1837.

“Dr. Williamson arrived at Lake Harriet after a six days’ journey from home, and assured us of their kindest wishes, and their willingness to furnish us with corn and potatoes, and a room in their house. We have just breakfasted on board our Mackinaw, and so far on our way have had cause for thankfulness that God so overruled events, even though some attendant circumstances were unpleasant. It is also a great source of comfort that we have so good accommodations and Sabbath-keeping company. You recollect my mentioning the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Prescott, and of his uniting with the church at Lake Harriet, in the summer.

“Perhaps you may feel some curiosity respecting our appearance and that of our barge. Fancy a large boat of forty feet in length, and perhaps eight in width in the middle, capable of carrying five tons, and manned by five men, four at the oars and a steersman at the stern. Near[Pg 48] the centre are our sleeping accommodations nicely rolled up, on which we sit, and breakfast and dine on bread, cold ham, wild fowl, etc. We have tea and coffee for breakfast and supper. Mrs. Prescott does not pitch and strike the tent, as the Indian women usually do; but it is because the boatmen can do it, and her husband does not require as much of her as an Indian man. They accommodate us in their tent, which is similar to a soldier’s tent, just large enough for two beds. Here we take our supper, sitting on or by the matting made by some of these western Indians, and then, after worship, lie down to rest.”

“Monday, Sept. 4.

“Again we are on our way up the crooked Saint Peter’s, having passed the Sabbath in our tent in the wilderness, far more pleasantly than the Sabbath we spent in St. Louis. Last Saturday I became quite fatigued sympathizing with those who drew the boat on the Rapids, and with following my Indian guide, Mrs. Prescott, through the woods, to take the boat above them. The fall at this stage of water was, I should think, two feet, and nearly perpendicular, excepting a very narrow channel, where it was slanting. The boat being lightened, all the men attempted to force it up this channel, some by the rope attached to the boat, and others by pulling and pushing it as they stood by it on the rocks and in the water. Both the first and second attempts were fruitless. The second time the rope was lengthened and slipped round a tree on the high bank, where the trader’s wife and I were standing. Her husband called her to hold the end of the rope, and, as I could not stand idle, though I knew I could do no good, I joined her, watching the slowly ascending boat with the deepest[Pg 49] interest. A moment more and the toil would have been over, when the rope snapped, and the boat slid back in a twinkling. It was further lightened and the rope doubled, and then it was drawn safely up and re-packed, in about two hours and a half from the time we reached the Rapids.”

“Tuesday, Sept. 5.

“In good health and spirits, we are again on our way. As the river is shallow and the bottom hard, poles have been substituted for oars; boards placed along the boat’s sides serve for a footpath for the boatmen, who propel the boat by fixing the pole into the earth at the prow and pushing until they reach the stern.

“At Traverse des Sioux our land journey, of one hundred and twenty-five miles to Lac-qui-parle, commenced. Here we made the acquaintance of a somewhat remarkable French trader, by name Louis Provencalle, but commonly called Le Bland. The Indians called him Skadan, Little White. He was an old voyager, who could neither read nor write, but, by a certain force of character, he had risen to the honorable position of trader. He kept his accounts with his Indian debtors by a system of hieroglyphics.

“For the next week we were under the convoy of Dr. Thomas S. Williamson and Mr. Gideon H. Pond, who met us with teams from Lac-qui-parle. The first night of our camping on the prairie, Dr. Williamson taught me a lesson which I never forgot. We were preparing the tent for the night, and I was disposed to let the roughness of the surface remain, and not even gather grass for a bed, which the Indians do; on the ground, as I said, that it was for only one night. ‘But,’ said the doctor,[Pg 50] ‘there will be a great many one nights.’ And so I have found it. It is best to make the tent comfortable for one night.”

This was our first introduction—Mary’s and mine—to the broad prairies of the West. At first, we kept in sight of the woods of the Minnesota, and our road lay among and through little groves of timber. But by and by we emerged into the broad savannahs—thousands of acres of meadow unmowed, and broad rolling country covered, at this time of year, with yellow and blue flowers. Every thing was full of interest to us, even the Bad Swamp,—Wewe Shecha,—which so bent and shook under the tramp of our teams, that we could almost believe it would break through and let us into the earth’s centre. For years after, this was the great fear of our prairie travelling, always reminding us very forcibly of Bunyan’s description of the “Slough of Despond.” The only accident of this journey was the breaking of the axle of one of Mr. Pond’s loaded carts. It was Saturday afternoon. Mr. Pond and Dr. Williamson remained to make a new one, and Mary and I went on to the stream where we were to camp, and made ready for the Sabbath.

“On the Broad Prairie of ‘the Far West.’

“Saturday Eve., Sept. 9, 1837.

“My Ever Dear Mother:—

“Just at twilight I seat myself upon the ground by our fire, with the wide heavens above for a canopy, to commune with her whose yearning heart follows her children wherever they roam. This is the second day we have travelled on this prairie, having left Traverse des Sioux[Pg 51] late Thursday afternoon. Before leaving that place, a little half-Indian girl, daughter of the trader where we stopped, brought me nearly a dozen of eggs (the first I had seen since leaving the States), which afforded us a choice morsel for the next day. To-morrow we rest, it being the Sabbath, and may we and you be in the Spirit on the Lord’s day.”

“Lac-qui-parle, Sept. 18.

“The date will tell you of our arrival at this station, where we have found a home. We reached this place on Wednesday last, having been thirteen days from Fort Snelling, a shorter time than is usually required for such a journey, the Lord’s hand being over us to guide and prosper us on our way. Two Sabbaths we rested from our travels, and the last of them was peculiarly refreshing to body and spirit. Having risen and put our tent in order, we engaged in family worship, and afterward partook of our frugal meal. Then all was still in that wide wilderness, save at intervals, when some bird of passage told us of its flight and bade our wintry clime farewell.

“Before noon we had a season of social worship, lifting up our hearts with one voice in prayer and praise, and reading a portion of God’s Word. It was indeed pleasant to think that God was present with us, far away as we were from any human being but ourselves. The day passed peacefully away, and night’s refreshing slumbers succeeded. The next morning we were on our way before the sun began his race, and having ridden fifteen or sixteen miles, according to our best calculations, we stopped for breakfast and dinner at a lake where wood and water could both be obtained, two essentials which frequently are not found together on the prairie.

“Thus you will be able to imagine us with our two one-ox carts and a double wagon, all heavily laden, as we have travelled across the prairie.”

Thomas Smith Williamson had been ten years a practising physician in Ripley, Ohio. There he had married Margaret Poage, of one of the first families. One after another their children had died. Perhaps that led them to think that God had a work for them to do elsewhere. At any rate, after spending a year in the Lane Theological Seminary, the doctor turned his thoughts toward the Sioux, for whom no man seemed to care. In the spring of 1834 he made a visit up to Fort Snelling. And in the year following, as has already been noted, he came as a missionary of the A. B. C. F. M., with his wife and one child, accompanied by Miss Sarah Poage, Mrs. Williamson’s sister, and Mr. Alexander G. Huggins and his wife, with two children.

This company reached Fort Snelling a week or two in advance of Mr. Stevens, and were making preparations to build at Lake Calhoun; but Mr. Stevens claimed the right of selection, on the ground that he had been there in 1829. And so Dr. Williamson and his party accepted the invitation of Mr. Joseph Renville, the Bois Brule trader at Lac-qui-parle, to go two hundred miles into the interior. All this was of the Lord, as it plainly appeared in after years. At the time we approached the mission at Lac-qui-parle, they had been two full years in the field, and, under favorable auspices, had made a very good beginning. About the middle of September, after a pretty good week of prairie travel, we were very glad to receive the greetings of the mission families....

A few days after our arrival, Mary wrote: “The evening we came, we were shown a little chamber, where we spread our bed and took up our abode. On Friday, Mr. Riggs made a bedstead, by boring holes and driving slabs into the logs, across which boards are laid. This answers the purpose very well, though rather uneven. Yesterday was the Sabbath, and such a Sabbath as I never before enjoyed. Although the day was cold and stormy, and much like November, twenty-five Indians and part-bloods assembled at eleven o’clock in our school-room for public worship. Excepting a prayer, all the exercises were in Dakota and French, and most of them in the former language. Could you have seen these Indians kneel with stillness and order, during prayer, and rise and engage in singing hymns in their own tongue, led by one of their own tribe, I am sure your heart would have been touched. The hymns were composed by Mr. Renville the trader, who is probably three-fourths Sioux.”

Doctor Williamson had erected a log house a story and a half high. In the lower part was his own living-room, and also a room with a large open fire-place, which then, and for several years afterward, was used for the school and Sabbath assemblies. In the upper part there were three rooms, still in an unfinished state. The largest of these, ten feet wide and eighteen feet long, was appropriated to our use. We fixed it up with loose boards overhead, and quilts nailed up to the rafters, and improvised a bedstead, as we had been unable to bring ours farther than Fort Snelling.

That room we made our home for five winters. There were some hardships about such close quarters, but, all in all, Mary and I never enjoyed five winters better than[Pg 54] those spent in that upper room. There our first three children were born. There we worked in acquiring the language. There we received our Dakota visitors. There I wrote and wrote again my ever growing dictionary. And there, with what help I could obtain, I prepared for the printer the greater part of the New Testament in the language of the Dakotas. It was a consecrated room.

Well, we had set up our cooking-stove in our upper room, but the furniture was a hundred and twenty-five miles away. It was not easy for Mary to cook with nothing to cook in. But the good women of the mission came to her relief with kettle and pan. More than this, there were some things to be done now which neither Mary nor I had learned to do. She was not an adept at making light bread, and neither of us could milk a cow. She grew up in New England, where the men alone did the milking, and I in Ohio, where the women alone milked in those days. At first it took us both to milk a cow, and it was poorly done. But Mary succeeded best. Nevertheless, application and perseverance succeeded, and, although never boasting of any special ability in that line of things, I could do my own milking, and Mary became very skilful in bread-making, as well as in other mysteries of housekeeping.

The missionary work began now to open before us. The village at Lac-qui-parle consisted of about 400 persons, chiefly of the Wahpaton, or Leaf-village band of the Dakotas. They were very poor and very proud. Mr. Renville, as a half-breed and fur-trader, had acquired an unbounded influence over many of them. They were willing to follow his leading. And so the young men of[Pg 55] his soldiers’ lodge were the first, after his own family, to learn to read. On the Sabbath, there gathered into this lower room twenty or thirty men and women, but mostly women, to hear the Word as prepared by Dr. Williamson with Mr. Renville’s aid. A few Dakota hymns had been made, and were sung under the leadership of Mr. Huggins or young Mr. Joseph Renville. Mr. Renville and Mr. Pond made the prayers in Dakota. Early in the year 1836, a church had been organized, which at this time contained seven native members, chiefly from Mr. Renville’s household. And in the winter which followed our arrival nine were added, making a native church of sixteen, of which one half were full-blood Dakota women, and in the others the Dakota blood greatly predominated.

One of the noted things that took place in those autumn days was the marriage of Mr. Gideon Holister Pond and Miss Sarah Poage. That was the first couple I married, and I look back to it with great satisfaction. The bond has been long since sundered by death, but it was a true covenant entered into by true hearts, and receiving, from the first, the blessing of the Master. Mr. Pond made a great feast, and “called the poor, and the maimed, and the halt, and the blind,” and many such Dakotas were there to be called. They could not recompense him by inviting him again, and it yet remains that “he shall be recompensed at the resurrection of the just.”

Nov. 2.

“Yesterday the marriage referred to was solemnized. Could I paint the assembly, you would agree with me that it was deeply and singularly interesting. Fancy, for a moment, the audience who were witnesses of the scene.[Pg 56] The rest of our missionary band sat near those of our number who were about to enter into the new and sacred relationship, while most of the room was filled with our dark-faced guests, a blanket or a buffalo robe their chief ‘wedding garment,’ and coarse and tawdry beads, brooches, paint, and feathers their wedding ornaments. Here and there sat a Frenchman or half-breed, whose garb bespoke their different origin. No turkey or eagle feathers adorned the hair, or parti-colored paint the face, though even their appearance and attire reminded us of our location in this wilderness.

“Mr. Riggs performed the marriage ceremony, and Dr. Williamson made the concluding prayer, and, through Mr. Renville, briefly explained to the Dakotas the ordinance and its institution. After the ceremony, Mr. Renville and family partook with us of our frugal meal, leaving the Indians to enjoy their feast of potatoes, turnips, and bacon, to which the poor, the lame, and the blind had been invited. As they were not aware of the supper that was provided, they did not bring their dishes, as is the Indian custom, so that they were scantily furnished with milk-pans, etc. This deficiency they supplied very readily by emptying the first course, which was potatoes, into their blankets, and passing their dishes for a supply of turnips and bacon.