| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

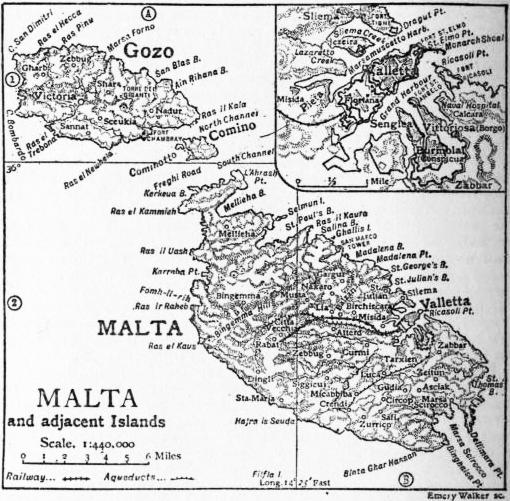

MALTA, the largest of the Maltese Islands, situated between Europe and Africa, in the central channel which connects the eastern and western basins of the Mediterranean Sea. The group belongs to the British Empire. It extends over 29 m., and consists of Malta, 91 sq. m., Gozo (q.v.) 20 sq. m., Comino (set apart as a quarantine station) 1 sq. m., and the uninhabited rocks called Cominotto and Filfla. Malta (lat. of Valletta Observatory 35° 53′ 55″ N., long. 14° 30′ 45″ W.) is about 60 m. from the nearest point of Sicily, 140 m. from the mainland of Europe and 180 from Africa; it has a magnificent natural harbour. From the dawn of maritime trade its possession has been important to the strongest nations on the sea for the time being.

Malta is about 17½ m. long by 8¼ broad; Gozo is 8¾ by 4½ m. This chain of islands stretches from N.E. to S.E. On the S.W. the declivities towards the sea are steep, and in places rise abruptly some 400 ft. from deep water. The general slope of these ridges is towards the N.W., facing Sicily and snow-capped Etna, the source of cool evening breezes. The Bingemma range, rising 726 ft., is nearly at right angles to the axis of the main island. The geological “Great Fault” stretches from sea to sea at the foot of these hills. There are good anchorages in the channels between Gozo and Comino, and between Comino and Malta. In addition to the harbours of Valletta, there are in Malta, facing N.W., the bays called Mellieha and St Paul’s, the inlets of the Salina, of Madalena, of St Julian and St Thomas; on the S.E. there is the large bay of Marsa Scirocco. There are landing places on the S.W. at Fomh-il-rih and Miggiarro. Mount Sceberras (on which Valletta is built) is a precipitous promontory about 1 m. long, pointing N.E. It rises out of deep water; well-sheltered creeks indent the opposite shores on both sides. The waters on the S.E. form the “Grand Harbour,” having a narrow entrance between Ricasoli Point and Fort St Elmo. The series of bays to the N.W., approached between the points of Tigne and St Elmo, is known as the Marsamuscetto (or Quarantine) Harbour.

Mighty fortifications and harbour works have assisted to make this ideal situation an emporium of Mediterranean trade. During the Napoleonic wars and the Crimean campaign the Grand Harbour was frequently overcrowded with shipping. The gradual supplanting of sail by steamships has made Malta a coaling station of primary importance. But the tendency to great length and size in modern vessels caused those responsible for the civil administration towards the end of the 19th century to realize that the harbour accommodation was becoming inadequate for modern fleets and first-class liners. A breakwater was therefore planned on the Monarch shoal, to double the available anchorage area and increase the frontage of deep-water wharves available in all weathers.

The Maltese Islands consist largely of Tertiary Limestone, with somewhat variable beds of Crystalline Sandstone, Greensand and Marl or Blue Clay. The series appears to be in line with similar formations at Tripoli in Africa, Cagliari in Geology and Water Supply. Sardinia, and to the east of Marseilles. To the south-east of the Great Fault (already mentioned) the beds are more regular, comprising, in descending order, (a) Upper Coralline Limestone; (b) Yellow, Black or Greensand; (c) Marl or Blue Clay; (d) White, Grey and Pale Yellow Sandstone; (e) Chocolate-coloured nodules with shells, &c.; (f) Yellow Sandstone; (g) Lower Crystalline Limestone. The Lower Limestone probably belongs to the Tongarian stage of the Oligocene series, and the Upper Coralline Limestone to the Tortonian stage of the Miocene. The beds are not folded. The general dip of the strata is from W.S.W. to E.N.E. North of the Great Fault and at Comino the level of the beds is about 400 ft. lower, bringing (c), the Marl, in juxtaposition with (g), the semi-crystalline Limestone. There is a system of lesser faults, parallel to the Great Fault, dividing the area into a number of blocks, some of which have fallen more than others. There are also indications of another series of faults roughly parallel to the south-east coast, which point to the islands being fragments of a former extensive plateau. The mammalian remains found in Pleistocene deposits are of exceptional interest. Among the more remarkable forms are a species of hippopotamus, the elephant (including a pigmy variety), and a gigantic dormouse. 508 In the Coralline Limestone the following fossils have been noted:—Spondylus, Ostrea, Pecten, Cytherea, Arca, Terebratula, Orthis, Clavagella, Echinus, Cidaris, Nucleolites, Brissus, Spatangus; in the Marl the Nautilus zigzag; in the Yellow, Black and Greensand shells of Lenticulites complanatus, teeth and vertebrae of Squalidae and Cetacea; in the Sandstone Vaginula depressa, Crystallaria, Nodosaria, Brissus, Nucleolites, Pecten burdigallensis, Scalaria, Scutella subrotunda, Spatangus, Nautilus, Ostrea navicularis and Pecten cristatus (see Captain Spratt’s work and papers by Lord Ducie and Dr Adams).

The Blue Clay forms, at the higher levels, a stratum impervious to water, and holds up the rainfall, which soaks through the spongy mass of the superimposed coralline formations. Hence arise the springs which run perennially, several of which have been collected into the gravitation water supplies of the Vignacourt and Fawara aqueducts. The larger part of the water supply, however, is now derived by pumping from strata at about sea-level. These strata are generally impregnated with salt water, and are practically impenetrable to the rain-water of less weight. The honeycomb of rock, and capillary action, retard the lighter fresh-water from sinking to the sea; the soakage from rain has therefore to move horizontally, over the strata about sea-level, seeking outlets. At this stage the rain-water is intercepted by wells, and by galleries hewn for miles in the water-bearing rock. Large reservoirs assist to store this water after it is raised, and to equalize its distribution.

The climate is, for the greater part of the year, temperate and healthy; the thermometer records an annual mean of 67° F. Between June and September the temperature ranges from 75° to 90°; the mean for December, January and Climate and Hygiene. February is 56°; March, May and November are mild. Pleasant north-east winds blow for an average of 150 days a year, cool northerly winds for 31 days, east winds 70 days, west for 34 days. The north-west “Gregale” (Euroclydon of Acts xxvii. 14) blows about the equinox, and occasionally, in the winter months, with almost hurricane force for three days together; it is recorded to have caused the drowning of 600 persons in the harbour in 1555. This wind has been a constant menace to shipping at anchor; the new breakwater on the Monarch Shoal was designed to resist its ravages. The regular tides are hardly perceptible, but, under the influence of barometric pressure and wind, the sea-level occasionally varies as much as 2 ft. The average rainfall is 21 in.; it is, however, uncertain; periods of drought have extended over three years. Snow is seen once or twice in a generation; violent hailstorms occur. On the 19th of October 1898, exceptionally large hailstones fell—one, over 4 in. in length, being brought to the governor, Sir Arthur Fremantle, for inspection. Mediterranean (sometimes called “Malta”) fever has been traced by Colonel David Bruce to a Micrococcus melitensis. The supply of water under pressure is widely distributed and excellent. There is a modern system of drainage for the towns, and all sewerage has been intercepted from the Grand Harbour. There are efficient hospitals and asylums, a system of sanitary inspection, and modernized quarantine stations.

It is hardly possible to differentiate between imported and indigenous plants. Among the marine flora may be mentioned Porphyra laciniata, the edible laver; Codium tomentosum, a coarse species; Padina pavonia, common in shallow Flora. water; Ulva latissima; Haliseris polypodioides; Sargassum bacciferum; the well-known gulf weed, probably transported from the Atlantic; Zostera marina, forming dense beds in muddy bays; the roots are cast up by storms and are valuable to dress the fields. Among the land plants may be noted the blue anemone; the ranunculus along the road-sides, with a strong perfume of violets; the Malta heath, which flowers at all seasons; Cynomorium coccineum, the curious “Malta fungus,” formerly so valued for medicinal purposes that a guard was set for its preservation under the rule of the Knights; the pheasant’s-eye; three species of mallow and geranium; Oxalis cernua, a very troublesome imported weed; Lotus edulis; Scorpiurus subvillosa, wild and cultivated as forage; two species of the horseshoe-vetch; the opium poppy; the yellow and claret-coloured poppy; wild rose; Crataegus azarolus, of which the fruit is delicious preserved; the ice-plant; squirting cucumber; many species of Umbelliferae; Labiatae, to which the spicy flavour of the honey (equal to that of Mt Hymettus) is ascribed; snap-dragons; broom-rape; glass-wort; Salsola soda, which produces when burnt a considerable amount of alkali; there are fifteen species of orchids; the gladiolus and iris are also found; Urginia scilla, the medicinal squill, abounds with its large bulbous roots near the sea; seventeen species of sedges and seventy-seven grasses have been recorded.

There are four species of lizard and three snakes, none of which is venomous; a land tortoise, a turtle and a frog. Of birds very few are indigenous; the jackdaw, blue solitary thrush, spectacled warbler, the robin, kestrel and the herring-gull. Fauna. A bird known locally as Hangi, not met elsewhere in Europe, nests at Filfla. Flights of quail and turtle doves, as well as teal and ducks, stay long enough to afford sport. Of migratory birds over two hundred species have been enumerated. The only wild mammalia in the island are the hedgehogs, two species of weasel, the Norway rat, and the domestic mouse. The Maltese dog was never wild and has ceased to exist as a breed.

Malta has several species of zoophytes, sponges, mollusca and crustacea. Insect life is represented by plant-bugs, locusts, crickets, grasshoppers, cockroaches, dragon-flies, butterflies, numerous varieties of moths, bees and mosquitoes.

Among the fish may be mentioned the tunny, dolphin, mackerel, sardine, sea-bream, dentice and pagnell; wrasse, of exquisite rainbow hue and good for food; members of the herring family, sardines, anchovies, flying-fish, sea-pike; a few representatives of the cod family, and some flat fish; soles (very rare); Cernus which grows to large size; several species of grey and red mullet; eleven species of Triglidae, including the beautiful flying gurnard whose colours rival the angel-fish of the West Indies; and eighteen species of mackerel, all migratory.

The real population of Malta, viz. of the country districts, is to be differentiated from the cosmopolitan fringe of the cities. There is continuous historical evidence that Malta remains to-day what Diodorus Siculus described it in Population and Language. the 1st century, “a colony of the Phoenicians”; this branch of the Caucasian race came down the great rivers to the Persian Gulf and thence to Palestine. It carried the art of navigation through the Mediterranean, along the Atlantic seaboard as far as Great Britain, leaving colonies along its path. In prehistoric times one of these colonies displaced previous inhabitants of Libyan origin. The similarity of the megalithic temples of Malta and of Stonehenge connect along the shores of western Europe the earliest evidence of Phoenician civilization. Philology proves that, though called “Canaanites” from having sojourned in that land, the Phoenicians have no racial connexion with the African descendants of Ham. No subsequent invader of Malta attempted to displace the Phoenician race in the country districts. The Carthaginians governed settlements of kindred races with a light hand; the Romans took over the Maltese as “dedititii,” not as a conquered race. Their conversion by St Paul added difference of religion to the causes which prevented mixture of race. The Arabs from Sicily came to eject the Byzantine garrison; they treated the Maltese as friends, and were not sufficiently numerous to colonize. The Normans came as fellow-Christians and deliverers; they found very few Arabs in Malta. The fallacy that Maltese is a dialect of Arabia has been luminously disproved by A. E. Caruana, Sull’ origine della lingua Maltese.

The upper classes have Norman, Spanish and Italian origin. The knights of St John of Jerusalem, commonly called “of Malta,” were drawn from the nobility of Catholic Europe. They took vows of celibacy, but they frequently gave refuge in Malta to relatives driven to seek asylum from feudal wars and disturbances in their own lands. At the British occupation there were about two dozen families bearing titles of nobility granted, 509 or recognized, by the Grand Masters, and descending by primogeniture. These “privileges” were guaranteed, together with the rights and religion of the islanders, when they became British subjects, but no government has ever recognized papal titles in Malta. High and low, all speak among themselves the Phoenician Maltese, altogether different from the Italian language; Italian was only spoken by 13.24% in 1901. Such Italian as is spoken by the lingering minority has marked divergences of pronunciation and inflexion from the language of Rome and Florence. In 1901, in addition to visitors and the naval and military forces, 18,922 Maltese spoke English, and the number has been rapidly increasing.

In appearance the Maltese are a handsome, well-formed race, about the middle height, and well set up; they have escaped the negroid contamination noticeable in Sicily, and their features are less dark than the southern Italians. The women are generally smaller than the men, with black eyes, fine hair and graceful carriage. They are a thrifty and industrious people, prolific and devoted to their offspring, good-humoured, quick-tempered and impressionable. The food of the working classes is principally bread, with oil, olives, cheese and fruit, sometimes fish, but seldom meat; common wine is largely imported from southern Europe. The Maltese are strict adherents to the Roman Catholic religion, and enthusiastic observers of festivals, fasts and ceremonials.

In 1906 the birth-rate was 40.68 per thousand, and the excess of births over deaths 2637. In April 1907 the estimated population was 206,690 of whom 21,911 were in Gozo. This phenomenal congestion of population gives interest to records of its growth; in the 10th century there were 16,767 inhabitants in Malta and 4514 in Gozo; the total population in 1514 was 22,000. Estimates made at the arrival of the knights (1530) varied from 15,000 to 25,000: it was then necessary to import annually 10,000 quarters of grain from Sicily. The population in 1551 was, Malta 24,000, Gozo 7000. In 1582, 20,000 quarters of imported grain were required to avert famine. A census of 1590 makes the population 30,500; in that year 3000 died of want. The numbers rose in 1601 to 33,000; in 1614 to 41,084; in 1632 to 50,113; in 1667 to 55,155; in 1667 11,000 are said to have died of plague out of the total population. At the end of the rule of the knights (1798) the population was estimated at 100,000; sickness, famine and emigration during the blockade of the French in Valletta probably reduced the inhabitants to 80,000. In 1829 the population was 114,236; in 1836, 119,878 (inclusive of the garrison); in 1873, 145,605; at the census in 1901 the civil population was 184,742. Sanitation decreases the death-rate, religion keeps up the birth-rate. Nothing is done to promote emigration or to introduce manufactures.

Towns and Villages.—The capital is named after its founder, the Grand Master de la Valette, but from its foundation it has been called Valletta (pop. 1901, 24,685); it contains the palace of the Grand Masters, the magnificent Auberges of the several “Langues” of the Order, the unique cathedral of St John with the tombs of the Knights and magnificent tapestries and marble work; a fine opera house and hospital are conspicuous. Between the inner fortifications of Valletta and the outer works, across the neck of the peninsula, is the suburb of Floriana (pop. 7278). To the south-east of Valletta, at the other side of the Grand Harbour, are the cities of Senglea (pop. 8093), Vittoriosa (pop. 8993); and Cospicua (pop. 12,184); this group is often spoken of as “The Three Cities.” The old capital, near the centre of the island is variously called Notabile, Città Vecchia (q.v.), and Medina, with its suburb Rabat, its population in 1901 was 7515; here are the catacombs and the ancient cathedral of Malta. Across the Marsamuscetto Harbour of Valletta is a considerable modern town called Sliema. The villages of Malta are Mellieha, St Paul’s Bay, Musta, Birchircara, Lia, Atterd, Balzan, Naxaro, Gargur, Misida, S. Julian’s, S. Giuseppe, Dingli, Zebbug, Siggieui, Curmi, Luca, Tarxein, Zurrico, Crendi, Micabbiba, Circop, Zabbar, Asciak, Zeitun, Gudia and Marsa Scirocco. The chief town of Gozo is called Victoria, and there are several small villages.

Industry and Trade.—The area under cultivation in 1906 was 41,534 acres. As a rule the tillers of the soil live away from their lands, in some neighbouring village. The fields are small and composed of terraces by which the soil has been walled up along the contours of the hills, with enormous labour, to save it from being washed away. Viewed from the sea, the top of one wall just appearing above the next produces a barren effect; but the aspect of the land from a hill in early spring is a beautiful contrast of luxuriant verdure. It is estimated that there are about 10,000 small holdings averaging about four acres and intensely cultivated. The grain crops are maize, wheat and barley; the two latter are frequently sown together. In 1906, 13,000 acres produced 17,975 quarters of wheat and 12,000 quarters of barley. The principal fodder crops are green barley and a tall clover called “sulla” (Hedysarum coronarum), having a beautiful purple blossom. Vegetables of all sorts are easily grown, and a rotation of these is raised on land irrigated from wells and springs. Potatoes and onions are grown for exportation at seasons when they are scarce in northern Europe. The rent of average land is about £2 an acre, of very good land over £3; favoured spots, irrigated from running springs, are worth up to £12 an acre. Two, and often three, crops are raised in the year; on irrigated land more than twice as many croppings are possible. The presence of phosphates accounts for the fertility of a shallow soil. There is a considerable area under vines, but it is generally more profitable to sell the fruit as grapes than to convert it into wine. Some of the best oranges in the world are grown, and exported; but sufficient care is not taken to keep down insect pests, and to replace old trees. Figs, apricots, nectarines and peaches grow to perfection. Some cotton is raised as a rotation crop, but no care is taken to improve the quality. The caroub tree and the prickly pear are extensively cultivated. There are exceptionally fine breeds of cattle, asses and goats; cows of a large and very powerful build are used for ploughing. The supply of butchers’ meat has to be kept up by constant importations. More than two-thirds of the wheat comes from abroad; fish, vegetables and fruit are also imported from Sicily in considerable quantities. Excellent honey is produced in Malta; at certain seasons tunny-fish and young dolphin (lampuca) are abundant; other varieties of fish are caught all the year round.

About 5000 women and children are engaged in producing Maltese lace. The weaving of cotton by hand-looms survives as a languishing industry. Pottery is manufactured on a small scale; ornamental carvings are made in Maltese stone and exported to a limited extent. The principal resources of Malta are derived from its being an important military station and the headquarters of the Mediterranean fleet. There are great naval docks, refitting yards, magazines and stores on the south-east side of the Grand Harbour; small vessels of war have also been built here. Steamers of several lines call regularly, and there is a daily mail to Syracuse. The shipping cleared in 1905-1906 was 3524 vessels of 3,718,168 tons. Internal communications include a railway about eight miles long from Valletta to Notabile; there are electric tramways and motor omnibus services in several directions. The currency is English. Local weights and measures include the cantar, 175 ℔; salm, one imperial quarter; cafiso, 4½ gallons; canna, 6 ft. 10½ in.; the tumolo (256 sq. ca.), about a third of an acre.

The principal exports of local produce are potatoes, cumin seed, vegetables, oranges, goats and sheep, cotton goods and stone.

To keep alive, in a fair standard of comfort, the population of 206,690, food supplies have to be imported for nine and a half months in the year. The annual value of exports would be set off against imported food for about one month and a half. The Maltese have to pay for food imports by imperial wages, earned in connexion with naval and military services, by commercial services to passing steamers and visitors, by earnings which emigrants send home from northern Africa and elsewhere, and by interest on investments of Maltese capital abroad. A long absence of the Mediterranean fleet, and withdrawals of imperial forces, produce immediate distress.

Finance.—The financial position in 1906-1907 is indicated by the following: Public revenue £513,594 (including £51,039 carried to revenue from capital); expenditure £446,849; imports (actual), £1,219,819; imports in transit, £5,876,981; exports (actual), £123,510; exports in transit £6,127,277; imports from the United Kingdom (actual), £218,461. In March 1907 there were 8159 depositors in the government savings bank, with £569,731 to their credit.

Government.—Malta is a crown colony, within the jurisdiction of a high commissioner and a commander-in-chief, to whom important questions of policy are reserved; in other matters the administration is under a military governor (£3000), assisted by a civil lieutenant-governor or chief secretary. There is an executive council, now comprising eleven members with the governor as president. The legislative council, under letters patent of the 3rd of June 1903, is composed of the governor (president), ten official members, and eight elected members. There are eight electoral districts with a total of about 10,000 electors. A voter is qualified on an income from property of £6, or by paying rent to the same amount, or having the qualifications required to serve as a common juror. There are no municipal institutions. Letters patent, orders in council, and local ordinances have the force of law. The laws of Justinian are still the basis of the common law, the Code of Rohan is not altogether abrogated, and considerable weight is still given to the Roman Canon Law. The principal provisions of the Napoleonic Code and some English enactments have been copied in a series of ordinances forming the Statute Law. Latin was the language of the courts till 1784, and was not completely supplanted by Italian till 1815. The partial use of English (with illogical limitations to the detriment of the Maltese-born British subjects who speak English) was introduced by local ordinances and orders in council at the end of the 19th century. The Maltese, of whom 86% cannot understand Italian, are still liable to be tried, even for their lives, in Italian, to them a foreign language. The endeavour to restrict juries to those who understand Italian reveals glaring incongruities.

Education.—There were, in 1906, 98 elementary day schools, and 33 night schools. The attendance on the 1st of September 1905 was 16,530, the percentage on those enrolled 84.6; the total enrolment was 18,719. The average cost per pupil in these schools was 35s. 11d. a year on daily attendance. There is a secondary school for girls in Valletta, and one for boys in Gozo. A lyceum in Malta had an average attendance of 464. The number of students at the university was about 150. The average cost per student in the lyceum was £8, 0s. 11d.; in the university £26, 10s. 1d. The fees in these institutions are almost nominal, the middle-classes are thus educated at the expense of the masses. In the 18th century the government of the Knights and of the Inquisition did not favour the education of the people, after 1800 British governors were slow to make any substantial change. About the middle of the 19th century it began to be recognized that the education of the people was more conducive to the safety of the fortress than to leave in ignorance congested masses of southern race liable to be swayed spasmodically by prejudice. At first an attempt was made to make Maltese a literary language by adapting the Arabic characters to record it in print. This failed for several reasons, the foremost being that the language was not Arabic but Phoenician, and because professors and teachers, whose personal ascendancy was based on the official prominence of Italian, did not realize that educational institutions existed for the rising generation rather than to provide salaries for alien teachers and men behind the times. Various educational schemes were proposed, but they were easier to propose than to carry into effect: no one, except Mr Savona, had the ability to urge English as the basis of instruction, and he agitated and was installed as director of education and made a member of the Executive. The obstruction which he encountered alarmed him, and he compromised by adopting a mixed system of both English and Italian, pari passu, as the basis of Maltese education; he resigned after a brief effort. Mr Savona’s attempt to teach the Maltese children simultaneously two foreign languages (of which they were quite ignorant, and their teachers only partially conversant) without first teaching how to read and write the native Maltese systematically was continued for some years under an eminent archaeologist, Dr A. A. Caruana, who became Director of Education. He began to give some preference to English indirectly. On his resignation Sir G. Strickland established a new system of education based on the principle of beginning from the bottom, by teaching to read and write in Maltese as the medium for assimilating, at a further stage, either English or Italian, one at a time, and aiming at imparting general knowledge in colloquial English. A series of school books, in the Maltese language printed in Roman characters, with translations in English interlined in different type, was produced at the government printing office and sold at cost price. The parents and guardians were called upon to select whether each child should learn English or Italian next after learning reading, writing and arithmetic in Maltese. About 89% recorded their preference in favour of English at the outset; then, as a result of violent political agitation, this percentage was considerably lowered, but soon crept up again. Teachers and professors who were weak in English, lawyers, newspaper men and others, combined to deprive these reforms of their legitimate consequence, viz. that after a number of years English should be the language of the courts as well as of education, and to protect those belonging to the old order of knowledge from the competition of young Maltese better educated than themselves, whose rapid rise everywhere would be assured by knowing English thoroughly. An order in council was enacted in 1899 providing that no Maltese (except students of theology) should thenceforth suffer any detriment through inability to pass examinations in Italian, in either the schools or university, but the fraction of the Maltese who claim to speak Italian (13.24%) still command sufficient influence to hamper the full enjoyment of this emancipation by the majority. In the university most of the textbooks used are English, nevertheless many of the lectures are still delivered in Italian—for the convenience of some professors or to please the politicians, rather than for the benefit of the students. The number of students who enter the university without passing any examination in Italian is rapidly increasing; the longer the period of transition, the greater the detriment to the rising generation.

History and Antiquities.—The earliest inhabitants of Malta (Melita) and Gozo (Gaulos) belonged to a culture-circle which included the whole of the western Mediterranean, and to a race which perhaps originated from North Africa; and it is they, and not the Phoenicians, who were the builders of the remarkable megalithic monuments which these islands contain, the Gigantia in Gozo, Hagiar Kim and Mnaidra near Crendi, the rock-cut hypogeum of Halsaflieni,1 and the megalithic buildings on the hill of Corradino in Malta, being the most noteworthy. The contemporaneity of these structures has been demonstrated by the identity of the pottery and other objects discovered in them, including some remarkable steatopygic figures in stone, and it is clear that they belong to the neolithic period, numerous flints, but no metal, having been found. Those that have been mentioned seem to have been sanctuaries (some of them in part dwelling-places), but Halsaflieni was an enormous ossuary, of which others may have existed in other parts of the island; for the numerous rock-cut tombs which are everywhere to be seen belong to the Phoenician and Roman periods. In these buildings there is a great preference for apsidal terminations to the internal chambers, and the façades are as a rule slightly curved. The numerous niches, generally containing sacrificial (?) tables,2 are often approached by window-like openings hewn out of one of the flat slabs by which they are enclosed. The surface of the stones in the interior is often pitted, as a form of ornamentation. Even the barren islet of Comino, between Malta and Gozo, was inhabited in prehistoric times.

To the Phoenician period, besides the tombs already mentioned, belong some remains of houses and cisterns, and (probably) a few round towers which are scattered about the island, while the important Roman house at Cittavecchia is the finest monument of this period in the islands.

The Carthaginians came to Malta in the 6th century B.C., not as conquerors, but as friends of a sister Phoenician colony (Freeman, Hist. Sicily, i. 255): Carthage in her struggle with Rome was at last driven to levy oppressive tribute, whereupon the Maltese gave up the Punic garrison to Titus Sempronius under circumstances described by Livy (xxi. 51). The Romans did not treat the Maltese as conquered enemies, and at once gave them the privileges of a municipium; Cicero (in Verrem) refers to the Maltese as “Socii.” Nothing was to be gained by displacing the Phoenician inhabitants in a country from which any race less thrifty would find life impossible by agriculture. On the strength of a monument bearing his name, it has been surmised that Hannibal was born in Malta, while his father was governor-general of Sicily; he certainly did not die in Malta. There is evidence from Cicero (in Verrem) that a very high stage of manufacturing and commercial prosperity, attained in 511 Carthaginian times, continued in Malta under the Romans. The Phoenician temple of Juno, which stood on the site of Fort St Angelo, is also mentioned by Valerius Maximus. An inscription records the restoration of the temple of Proserpine by Cheriston, a freed-man of Augustus and procurator of Malta. Diodorus Siculus (L. V., c. 4) speaks of the importance and ornamentation of Maltese dwellings, and to this day remains of palaces and dwellings of the Roman period indicate a high degree of civilization and wealth. When forced to select a place of exile, Cicero was at first (ad Att. III. 4, X. i. 8, 9) attracted to Malta, over which he had ruled as quaestor 75 B.C. Among his Maltese friends were Aulus Licinius and Diodorus. Lucius Castricius is mentioned as a Roman governor under Augustus. Publius was “chief of the island” when St Paul was shipwrecked (Acts xxvii. 7); and is said to have become the first Christian bishop of Malta. The site where the cathedral at Notabile now stands is reputed to have been the residence of Publius and to have been converted by him into the first Christian place of worship, which was rebuilt in 1090 by Count Roger, the Norman conqueror of Malta. The Maltese catacombs are strikingly similar to those of Rome, and were likewise used as places of burial and of refuge in time of persecution. They contain clear indication of the interment of martyrs. St Paul’s Bay was the site of shipwreck of the apostle in A.D. 58; the “topon diathalasson” referred to in Acts is the strait between Malta and the islet of Selmun. The claim that St Paul was shipwrecked at Meleda off the Dalmatian coast, and not at Malta, has been clearly set at rest, on nautical grounds, by Mr Smith of Jordanhill (Voyage and Shipwreck of St Paul, London, 1848). According to tradition and to St Chrysostom (Hom. 54) the stay of the apostle resulted in the conversion of the Maltese to Christianity. The description of the islanders in Acts as “barbaroi” confirms the testimony of Diodorus Siculus that they were Phoenicians, neither hellenized nor romanized. The bishopric of Malta is referred to by Rocco Pirro (Sicilia sacra), and by Gregory the Great (Epist. 2, 44; 9, 63; 10, 1). It appears that Malta was not materially affected by the Greek schism, and remained subject to Rome.

On the final division of the Roman dominions in A.D. 395 Malta was assigned to the empire of Constantinople. On the third Arab invasion, A.D. 870, the Maltese joined forces against the Byzantine garrison, and 3000 Greeks were massacred. Unable to garrison the island with a large force, the Arabs cleared a zone between the central stronghold, Medina, and the suburb called Rabat, to restrict the fortified area. Many Arab coins, some Kufic inscriptions and several burial-places were left by the Arabs; but they did not establish their religion or leave a permanent impression on the Phoenician inhabitants, or deprive the Maltese language of the characteristics which differentiate it from Arabic. There is no historical evidence that the domination of the Goths and Vandals in the Mediterranean ever extended to Malta; there are fine Gothic arches in two old palaces at Notabile, but these were built after the Norman conquest of Malta. In 1090 Count Roger the Norman (son of Tancred de Hauteville), then master of Sicily, came to Malta with a small retinue; the Arab garrison was unable to offer effective opposition, and the Maltese were willing and able to welcome the Normans as deliverers and to hold the island after the immediate withdrawal of Count Roger. A bishop of Malta was witness to a document in 1090. The Phoenician population had continued Christian during the mild Arab rule. Under the Normans the power of the Roman Church quickly augmented, tithes were granted, and ecclesiastical buildings erected and endowed. The Normans, like the Arabs, were not numerically strong; the rule of both, in Sicily as well as Malta, was based on a recognition of municipal institutions under local officials; the Normans, however, exterminated the Mahommedans. Gradually feudal customs asserted themselves. In 1193 Margarito Brundusio received Malta as a fief with the title of count; he was Grand Admiral of Sicily. Constance, wife of the emperor Henry IV. of Germany became, in 1194, heiress of Sicily and Malta; she was the last of the Norman dynasty. The Grand Admiral of Sicily in 1223 was Henry, count of Malta. He had led 300 Maltese at the capture of two forts in Tripoli by the Genoese. In 1265 Pope Alexander IV. conferred the crown of Sicily on Charles of Anjou to the detriment of Manfred, from whom the French won the kingdom at the battle of Benevento. Under the will of Corradino a representative of the blood of Roger the Norman, Peter of Aragon claimed the succession, and it came to him by the revolution known as “the Sicilian Vespers” when 28,000 French were exterminated in Sicily. Charles held Malta for two years longer, when the Aragonese fleet met the French off Malta, and finally crushed them in the Grand Harbour. In 1427 the Turks raided Malta and Gozo, they carried many of the inhabitants into captivity, but gained no foothold. The Maltese joined the Spaniards in a disastrous raid against Gerbi on the African coast in 1432. In 1492 the Aragonese expelled the Jews. Dissatisfaction arose under Aragonese rule from the periodical grants of Malta, as a marquisate or countship, to great officers of state or illegitimate descendants of the sovereign. Exemption was obtained from these incidences of feudalism by large payments to the Crown in return for charters covenanting that Malta should for ever be administered under the royal exchequer without the intervention of intermediary feudal lords. This compact was twice broken, and in 1428 the Maltese paid King Alfonso 30,000 florins for a confirmation of privileges, with a proviso that entitled them to resist by force of arms any intermediate lord that his successors might attempt to impose. Under the Aragonese, Malta, as regards local affairs, was administered by a Università or municipal commonwealth with wide and indefinite powers, including the election of its officers, Capitan di Verga, Jurats, &c. The minutes of the “Consiglio Popolare” of this period are preserved, showing it had no legislative power; this was vested in the king, and was exercised despotically in the interests of the Crown. The Knights of St John having been driven from Rhodes by the Turks, obtained the grant of Malta, Gozo and Tripoli in 1530 from the emperor Charles V., subject to a reversion in favour of the emperor’s successor in the kingdom of Aragon should the knights leave Malta, and to the annual tribute of a falcon in acknowledgment that Malta was under the suzerainty of Spain. The Maltese, at first, challenged the grant as a breach of the charter of King Alfonso, but eventually welcomed the knights. The Grand Master de l’Isle Adam, on entering the ancient capital of Notabile, swore for himself and his successors to maintain the rights and liberties of the Maltese. The Order of St John took up its abode on the promontory guarded by the castle of St Angelo on the southern shore of the Grand Harbour, and, in expectation of attacks from the Turks, commenced to fortify the neighbouring town called the Borgo. The knights lived apart from the Maltese, and derived their principal revenues from estates of the Order in the richest countries of Europe. They accumulated wealth by war, or by privateering against the Turks and their allies. The African Arabs under Selim Pasha in 1551 ravaged Gozo, after an unsuccessful attempt on Malta, repulsed by cavalry under Upton, an English knight. The Order of St John and the Christian Maltese now realized that an attempt to exterminate them would soon be made by Soliman II., and careful preparations were made to meet the attack.

The great siege of Malta which made the island and its knights famous, and checked the advance of Mahommedan power in southern and western Europe, began in May 1565. The fighting men of the defenders are variously recorded between 6100 and 9121; the roll comprises one English knight, Oliver Starkey. The Mahommedan forces were estimated from 29,000 to 38,500. Jehan Parisot de la Valette had participated in the defence of Rhodes, and in many naval engagements. He had been taken prisoner by Dragut, who made him row for a year as a galley slave till ransomed. This Grand Master had gained the confidence of Philip of Spain, the friendship of the viceroy of Sicily, of the pope and of the Genoese admiral, Doria. The Sultan placed his troops under the veteran Mustapha, and his galleys under his youthful relative Piali, he hesitated to make either supreme and ordered them to await the arrival of Dragut with 512 his Algerian allies, before deciding on their final plans. Meanwhile, against Mustapha’s better judgment, Piali induced the council of war to attack St Elmo, in order to open the way for his fleet to an anchorage, safe in all weathers, in Marsamuscetto harbour. This strategical blunder was turned to the best advantage by La Valette, who so prolonged the most heroic defence of St Elmo that the Turks lost 7000 killed and as many wounded before exterminating the 1200 defenders, who fell at their post. In the interval Dragut was mortally wounded, the attack on Notabile was neglected, valuable time lost, and the main objective (the Borgo) and St Angelo left intact. The subsequent siege of St Angelo, and its supporting fortifications, was marked by the greatest bravery on both sides. The knights and their Maltese troops fought for death or victory, without asking or giving quarter. The Grand Master proved as wise a leader as he was brave. By September food and ammunition were getting scarce, a large relieving force was expected from Sicily, and Piali became restive, on the approach of the equinox, for the safety of his galleys. At last the viceroy of Sicily, who had the Spanish and allied fleets at his disposal, was spurred to action by his council. He timidly landed about 6000 or 8000 troops at the north-west of Malta and withdrew. The Turks began a hurried embarcation and allowed the Christians to join forces at Notabile; then, hearing less alarming particulars of the relieving force, Mustapha relanded his reluctant troops, faced his enemies in the open, and was driven in confusion to his ships on the 8th of September.

The Order thus reached the highest pinnacle of its fame, and new knights flocked to be enrolled therein from the flower of the nobility of Europe; La Valette refused a cardinal’s hat, determined not to impair his independence. He made his name immortal by founding on Mt Sceberras “a city built by gentlemen for gentlemen” and making Valletta a magnificent example of fortification, unrivalled in the world. The pope and other sovereigns donated vast sums for this new bulwark of Christianity, but, as its ramparts grew in strength, the knights were slow to seek the enemy in his own waters, and became false to their traditional strategy as a naval power. Nevertheless, they harassed Turkish commerce and made booty in minor engagements throughout the 16th and 18th centuries, and they took part as an allied Christian power in the great victory of Lepanto. With the growth of wealth and security the martial spirit of the Order began to wane, and so also did its friendly relations with the Maltese. The field for recruiting its members, as well as its landed estates, became restricted by the Reformation in England and Germany, and the French knights gradually gained a preponderance which upset the international equilibrium of the Order. The election of elderly Grand Masters became prevalent, the turmoil and chances of frequent elections being acceptable to younger members. The civil government became neglected and disorganized, licentiousness increased, and riots began to be threatening. Expenditure on costly buildings was almost ceaseless, and kept the people alive. In 1614 the Vignacourt aqueduct was constructed. The Jesuits established a university, but they were expelled and their property confiscated in 1768. British ships of war visited Malta in 1675, and in 1688 a fleet under the duke of Grafton came to Valletta. The fortifications of the “Three Cities” were greatly strengthened under the Grand Master Cotoner.

In 1722 the Turkish prisoners and slaves, then very numerous, formed a conspiracy to rise and seize the island. Premature discovery was followed by prompt suppression. Castle St Angelo and the fort of St James were, in 1775, surprised by rebels, clamouring against bad government; this rising is known as the Rebellion of the Priests, from its leader, Mannarino. The last but one of the Grand Masters who reigned in Malta, de Rohan, restored good government, abated abuses and promulgated a code of laws; but the ascendancy acquired by the Inquisition over the Order, the confiscation of the property of the knights in France on the outbreak of the Revolution, and the intrigues of the French made the task of regenerating the Order evidently hopeless in the changed conditions of Christendom. On the death of Rohan the French knights disagreed as to the selection of his successor, and a minority were able to elect, in 1797, a German of weak character, Ferdinand Hompesch, as the last Grand Master to rule in Malta. Bonaparte had arranged to obtain Malta by treachery, and he took possession without resistance in June 1798; after a stay of six days he proceeded with the bulk of his forces to Egypt, leaving General Vaubois with 6000 troops to hold Valletta. The exiled knights made an attempt to reconstruct themselves under the emperor Paul of Russia, but finally the Catholic parent stem of the Order settled in Rome and continues there under papal auspices. It still comprises members who take vows of celibacy and prove the requisite number of quarterings.

Towards the close of the rule of the knights in Malta feudal institutions had been shaken to their foundations, but the transition to republican rule was too sudden and extreme for the people to accept it. The French plundered the churches, abolished monks, nuns and nobles, and set up forthwith the ways and doings of the French Revolution. Among other laws Bonaparte enacted that French should at once be the official language, that 30 young men should every year be sent to France for their education; that all foreign monks be expelled, that no new priests be ordained before employment could be found for those existing; that ecclesiastical jurisdiction should cease; that neither the bishop nor the priests could charge fees for sacramental ministrations, &c. Stoppage of trade, absence of work (in a population of which more than half had been living on foreign revenues of the knights), and famine, followed the defeat of Bonaparte at the Nile, and the failure of his plans to make Malta a centre of French trade. An attempt to seize church valuables at Notabile was forcibly resisted by the Maltese, and general discontent broke out into open rebellion on the 2nd of September 1798. The French soon discovered to their dismay that, from behind the rubble walls of every field, the agile Maltese were unassailable. The prospect of an English blockade of Malta encouraged the revolt, of which Canon Caruana became the leader. Nelson was appealed to, and with the aid of Portuguese allies he established a blockade and deputed Captain Ball, R. N. (afterwards the first governor) to assume, on the 9th of February 1799, the provisional administration of Malta and to superintend operations on land. Nelson recognized the movement in Malta as a successful revolution against the French, and upheld the contention that the king of Sicily (as successor to Charles V. in that part of the former kingdom of Aragon) was the legitimate sovereign of Malta. British troops were landed to assist in the siege; few lives were lost in actual combat, nevertheless famine and sickness killed thousands of the inhabitants, and finally forced the French to surrender to the allies. Canon Caruana and other leaders of the Maltese aspired to obtain for Malta the freedom of the Roman Catholic religion guaranteed by England in Canada and other dependencies, and promoted a petition in order that Malta should come under the strong power of England rather than revert to the kingdom of the two Sicilies.

The Treaty of Amiens (1802) provided for the restoration of the island to the Order of St John; against this the Maltese strongly protested, realizing that it would be followed by the re-establishment of French influence. The English flag was flown side by side with the Neapolitan, and England actually renewed war with France sooner than give up Malta. The Treaty of Paris (1814), with the acclamations of the Maltese, confirmed Great Britain in the aggregation of Malta to the empire.

A period elapsed before the government of Malta again became self-supporting, during which over £600,000 was contributed by the British exchequer in aid of revenue, and for the importation of food-stuffs. The restoration of Church property, the re-establishment of law and administration on lines to which the people were accustomed before the French invasion, and the claiming for the Crown of the vast landed property of the knights, were the first cares of British civil rule. As successor to the Order, the Crown claimed and eventually established (by the negotiations in Rome of Sir Frederick Hankey, Sir Gerald Strickland and 513 Sir Lintorn Simmons) with regard to the presentation of the bishopric (worth about £4000 a year) the right to veto the appointment of distasteful candidates. This right was exercised to secure the nomination of Canon Caruana and later of Monsignor Pace. When the pledge, given by the Treaty of Amiens, to restore the Order of St John with a national Maltese “langue,” could not be fulfilled, political leaders began demanding instead the re-establishment of the “Consiglio Popolare” of Norman times (without reflecting that it never had legislative power); but by degrees popular aspirations developed in favour of a free constitution on English lines. The British authorities steadily maintained that, at least until the mass of the people became educated, representative institutions would merely screen irresponsible oligarchies. After the Treaty of Paris stability of government developed, and many important reforms were introduced under the strong government of the masterful Sir Thomas Maitland; he acted promptly, without seeking popularity or fearing the reverse, and he ultimately gained more real respect than any other governor, not excepting the marquess of Hastings, who was a brilliant and sympathetic administrator. Trial by jury for criminal cases was established in 1829. A council of government, of which the members were nominated, was constituted by letters patent in 1835, but this measure only increased the agitation for a representative legislature. Freedom of the press and many salutary innovations were brought about on a report of John Austin and G. C. Lewis, royal commissioners, appointed in 1836. The basis of taxation was widened, sinecures abolished, schools opened in the country districts, legal procedure simplified, and Police established on an English footing. Queen Adelaide visited Malta in 1838 and founded the Anglican collegiate church of St Paul. Sir F. Hankey as chief secretary was for many years the principal official of the civil administration. In 1847 Mr R. Moore O’Ferrall was appointed civil governor. In June 1849 the constitution of the council was altered to comprise ten nominated and eight elected members.

The revolutions in Italy caused about this time many, including Crispi and some of the most intellectual Italians, to take refuge in Malta. These foreigners introduced new life into politics and the press, and made it fashionable for educated Maltese to delude themselves with the idea that the Maltese were Italians, because a few of them could speak the language of the peninsula. A clerical reaction followed against new progressive ideas and English methods of development. After much unreasoning vituperation the Irish Catholic civil governor, who had arrived amidst the acclamations of all, left his post in disgust. His successor as civil governor was Sir W. Reid, who had formerly held military command. His determined attempts to promote education met with intense opposition and little success. At this period the Crimean War brought great wealth and commercial prosperity to Malta. Under Sir G. Le Marchant, in 1858, the nominal rule of military governors was re-established, but the civil administration was largely confided to Sir Victor Houlton as chief secretary, whilst the real power began to be concentrated in the hands of Sir A. Dingli, the Crown advocate, who was the interpreter of the law, and largely its maker, as well as the principal depository of local knowledge, able to prevent the preferment of rivals, and to countenance the barrier which difference of language created between governors and governed. The civil service gravitated into the hands of a clique. At this period much money was spent on the Marsa extension of the Grand Harbour, but the rapid increase in the size of steamships made the scheme inadequate, and limited its value prematurely. The military defences were entirely remodelled under Sir G. Le Marchant, and considerable municipal improvements and embellishments were completed. But this governor was obstructed and misrepresented by local politicians as vehemently as his predecessors and his successors. Ministers at home have often appeared to be inclined to the policy of pleasing by avoiding the reforming of what might be left as it was found. Sir A. Dingli adapted a considerable portion of the Napoleonic Code in a series of Malta Ordinances, but stopped short at points likely to cause agitation. Sir P. Julyan was appointed royal commissioner on the civil establishments, and Sir P. Keenan on education; their work revived the reform movement in 1881. Mr Savona led an agitation for a more sincere system of education on English lines. Fierce opposition ensued, and the pari passu compromise was adopted to which reference is made in the section on Education above; Mr Savona was an able organizer, and began the real emancipation of the Maltese masses from educational ignorance; but he succumbed to agitation before accomplishing substantial results.

An executive council was established in 1881, and the franchise was extended in 1883. A quarter of a century of Sir Victor Houlton’s policy of laissez-faire was changed in 1883 by the appointment of Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson as chief secretary. An attempt was made to utilize fully the abilities of this eminent administrator by creating him civil lieutenant-governor, in whom to concentrate both the real and the nominal power of detailed administration; but the military authorities objected to his corresponding directly with the Colonial Office; and a political deadlock began to develop. Sir A. Dingli was transferred from an administrative office to that of chief justice. With the continuance of military power over details, the public could not understand where responsibility really rested. The elected members under the leadership of Dr Mizzi clamoured for more power, opposed reforms and protested against the carrying of government measures by the casting vote of a military governor as president of the council. To force a crisis, abstention of elected members from the council was resorted to, together with the election of notoriously unfit candidates. Under these circumstances a constitution of a more severe type was recommended by those responsible for the government of Malta and was about to be adopted, as the only alternative to a deadlock, by the imperial authorities.

A regulation excluding Maltese from the navy (because of their speaking on board a language that their officers did not understand) provoked from Trinity College, Cambridge, the Strickland correspondence in The Times on the constitutional rights of the Maltese, and a leading article induced the Colonial Office to try an experiment known as the Strickland-Mizzi Constitution of 1887. This constitution (abolished in 1903) ended a period of government by presidential casting votes and official ascendancy. For the first time the elected members were placed in a majority; they were given three seats in the executive council; in local questions the government had to make every effort to carry the majority by persuasion. When persuasion failed and imperial interests, or the rights of unrepresented minorities, were involved the power of the Crown to legislate by order in council could be (and was) freely used. This system had the merit of counteracting any abuse of power by the bureaucracy. It brought to bear on officials effective criticism, which made them alert and hard-working. Governor Simmons eventually gave his support to the new constitution, which was received with acclamation. Strickland, who had been elected while an undergraduate on the cry of equality of rights for Maltese and English, and Mizzi, the leader of the anti-English agitation, were, as soon as elected, given seats in the executive council to cooperate with the government; but their aims were irreconcilable. Mizzi wanted to undo the educational forms of Mr Savona, to ensure the predominance of the Italian language and to work the council as a caucus. Strickland desired to replace bureaucratic government by a system more in touch with the independent gentlemen of the country, and to introduce English ideas and precedents. Friction soon arose. Mizzi cared little for a constitution that did not make him complete master of the situation, and resigned his post in the government.

Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson left Malta in March 1889, and was succeeded by Sir Gerald Strickland (Count Delia Catena), who lost no time in pushing, and carrying with a rapidity that was considered hasty, reforms that had been retarded for years. The majorities behind the government began to dwindle and agitation to grow. Meanwhile the Royal Malta Militia was established as a link between the Maltese and the garrison. The police were reorganized with proper pay, criminal laws were rigorously 514 enforced. A naval officer was placed over the police to diminish difficulties with the naval authorities and sailors. A marine force was raised to stop smuggling; and the subtraction of coal during coaling operations was stopped by drastic legislation. The civil service was reorganized so as to reward merit and work by promotion. Tenders were strictly enforced in letting government property and contracts; a largely increased revenue was applied on water supply, drainage and other works. Lepers were segregated by law.

The Malta marriage question evoked widespread agitation; Sir A. Dingli had refrained from making any provision in his code as to marrying. The Maltese relied on the Roman Canon Law, the English on the common law of England, Scots or Irish had nothing but the English law to fall back upon. Maltese authorities were ignorant of the disabilities of British Nonconformists at common law, and they had not perceived that persons with a British domicile could not evade their own laws by marrying in Malta, e.g. that an English girl up to the age of 21 required the father’s or guardian’s consent from which a Maltese was legally exempt at 18. Sir G. Strickland preferred legislation to the covering up of difficulties by governors’ licences and appeals to incongruous precedents. Sir Lintorn Simmons was appointed envoy to the Holy See, to ascertain how far legislation might be pushed in the direction of civil marriage without justifying clerical agitation and obstruction in the council. He succeeded in coming to an agreement with Rome. Nevertheless Sir A. Dingli and ecclesiastics of all denominations, for conflicting reasons, swelled the opposition against the liberal concessions obtained from Leo XIII. The legal necessity for legislation in accordance with the agreement was, nevertheless, on a special reference, submitted to the privy council, whose decision affirmed the advisability of legislation and the need for validating retrospectively marriages not supported by either Maltese or English common law. Agitation in the imperial parliament stopped government action, but the publicity of the finding of the privy council warned all concerned against the risk of neglecting the common law of the empire whenever they were not prepared to follow the lex loci contractus.

Since the British occupation it was disputed whether the military authorities had the right to alienate for the benefit of the imperial exchequer fortress sites no longer required for defence. The reversion of such property was claimed for the local civil government, and the principles governing these rights were ultimately laid down by an order in council, which also determined military rights to restrict buildings within the range of forts. The co-operation of naval and military authorities was obtained for the construction, at imperial expense, of the breakwater designed to save Malta from being abandoned by long and deep draft modern vessels. British-born subjects were given the right to be tried in English. The new system of education (already described) was set up, and many new schools were built with funds provided by order in council against the wishes of the elected majority.

An order in council (1899) making English the language of the courts after fifteen years (by which the Maltese would have obtained the right to be tried in English) was promulgated at a time when the system of taxation was also being revised; henceforth agitation in favour of Italian and against taxation attained proportions unpleasant for those who preferred popularity to reform and progress. The elected members demanded the recall of Sir G. Strickland on his refusing to change his policy. The military governor gave way, as regards making English the language of the courts on a fixed date, but educational reforms and the imposition of new taxes (those in Malta being 27s. 6d. per head, against 93s. in England) were enacted by an order in council notwithstanding the agitation. Mr Mereweather was appointed chief secretary and civil lieutenant-governor in 1902, and Sir Gerald Strickland became governor and commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands. Governor Sir F. Grenfell was created a peer. Strenuous efforts were made to placate the Italian party in the administration of the educational reforms; but, as these were not repealed, elected members refused supply, and kept away from the council. Persistence in this course led to the repeal by letters-patent of 1903 of the Strickland-Mizzi Constitution of 1887. In place of occasional orders in council for important matters in urgent cases, bureaucratic government with an official majority was again, with its drawbacks, fully re-established for all local affairs great and small. The representatives of the people were repeatedly re-elected, only to resign again and again as a protest against a restricted constitution.

Authorities.—Kenrick’s Phoenicia (1855); A. A. Caruana’s Reports on Phoenician and Roman Antiquities in Malta (1881 and 1882); Albert Mayr, Die Insel Malta im Altertum (1909); James Smith, Voyage and Shipwreck of St Paul (1866); R. Pirro, Sicilia sacra; T. Fazello, Storia di Sicilia (1833); C. de Bazincourt, Histoire de la Sicile (1846); G. F. Abela, Malta illustrata (1772); J. Quintin, Insulae Melitae descriptio (1536); G. W. von Streitburg, Reyse nach der Inselmalta (1632); R. Gregoria, Considerazioni sopra la storia di Sicilia (1839); F. C. A. Davalos, Tableau historique de Malte (1802); Houel, Voyage pittoresque (vol. iv., 1787); G. P. Badger, Description of Malta and Gozo (1858); G. N. Goodwin, Guide to and Natural History of Maltese Islands (1800); Whitworth Porter, History of Knights of Malta (1858); A. Bigelow, Travels in Malta and Sicily (1831); M. Miège, Histoire de Malte (1840); Parliamentary Papers, reports by Mr Rownell on Taxation and Expenditure in Malta (1878), by Sir F. Julyan on Civil Establishments (1880); and Mr Keenan on the Educational System (1880), (the last two deal with the language question); F. Vella, Maltese Grammar for the Use of the English (1831); Malta Penny Magazine (1839-1841); J. T. Mifsud, Biblioteca Maltese (1764); C. M. de Piro, Squarci di storia; Michele Acciardi, Mustafa bascia di Rodi schiavo in Malta (1761); A. F. Freiherr, Reise nach Malta in 1830 (Vienna, 1837); B. Niderstedt, Malta vetus et nova, 1660; F. Panzavecchia, Storia dell’ isola di Malta; N. W. Senior, Conversations on Egypt and Malta (1882); G. A. Vassallo, Storia di Malta (1890); H. Felsch, Reisebeschreibung (1858); W. Hardman, Malta, 1798-1815 (1909); A. Nieuterberg, Malta (1879); Terrinoni, La Presa di Malta (1860); Azzopardi, Presa di Malta (1864); Castagna, Storia di Malta (1900); Boisredon, Ransijat, Blocus et siège de Malte (1802); Buchon, Nouvelles recherches historiques; C. Samminniateli, Zabarella, L’ Assedio di Malta del 1565 (1902); Professor G. B. Mifsud, Guida al corso di Procedura Penale Maltese (1907); P. de Bono Debono, Storia della legislazione in Malta (1897); Monsignor A. Mifsud, L’Origine della sovranità della Grand Brettagna su Malta (1907); A. A. Caruana, Frammento critico della storia di Malta (1899); Ancient Pagan Tombs and Christian Cemeteries in the Island of Malta, Explored and Surveyed from 1881 to 1897; Strickland, Remarks and Correspondence on the Constitution of Malta (1887); A. Mayr, Die vorgeschichtlichen Denkmäler von Malta (1901); A. E. Caruana, Sull’ origine della lingua Maltese (1896); J. C. Grech, Flora melitensis (1853); Furse, Medagliere Gerosolimitano; Pisani, Medagliere; Galizia, Church of St John; J. Murray, “The Maltese Islands, with special reference to their Geological Structure,” Scottish Geog. Mag. (vol. vi., 1890); J. W. Gregory, “The Maltese Fossil Echinoidea and their evidence on the correlation of the Maltese Rocks,” Trans. Roy. Soc. Edin. (vol. xxxvi., 1892); J. H. Cook, The Har Dalam Cavern, Malta, Evidences of Prehistoric Man in Malta; Collegamento geodetico delle isole maltesi con la Sicilia (1902); A. Zeri, I porti delle isole del gruppo di Malta (1906); G. F. Bonamico, Delle glossipietre di Malta (1688).

Brydone, Teonge, John Dryden jun., W. Tallack, Rev. H. Seddall, Boisgolin, Rev. W. K. Bedford, W. H. Bartlett, St Priest. Msgr. Bres, M. G. Borch, Oliver Drapper, John Davy, G. M. Letard, Taafe, Busuttil, T. MacGill, J. Quintana, have also written on Malta. For natural science see the works of Dr A. L. Adams, Professor E. Forbes, Captain Spratt, Dr G. Gulia, C. A. Wright and Wood’s Tourist Flora.

For the language question, see Mr Chamberlain’s speech in the House of Commons, on the 28th of January 1902. Also parliamentary papers for Grievances of the Maltese Nobility, and Constitutional Changes.

1 See T. Zammit, The Halsaflieni prehistoric hypogeum at Casal Paula, Malta (Malta, 1910).

2 Sometimes the pillar which represents the baetylus, which seems to have been the object of worship, (see A. J. Evans in Journal of Hellenic Studies, xxi., 1901) stands free sometimes it serves as support to the table stone which covers the niche, and sometimes again monolithic tables occur. Conical stones (possibly themselves baetyli) are also found.

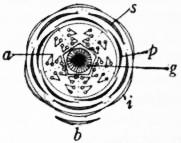

MALTA (or Mediterranean) FEVER, a disease long prevalent of Malta and formerly at Gibraltar, as well as other Mediterranean centres, characterized by prolonged high temperature, with anaemia, pain and swelling in the joints, and neuritis, lasting on an average four months but extending even to two or three years. Its pathology was long obscure, but owing to conclusive research on the part of Colonel (afterwards Sir) David Bruce, to which contributions were made by various officers of the R.A.M.C. and others, this problem had now been solved. A specific micro-organism, the Micrococcus melitensis, was discovered in 1887, and it was traced to the milk of the Maltese goats. A commission was sent out to Malta in 1904 to investigate the question, and after three years’ work its conclusions were embodied in a report by Colonel Bruce in 1907. It was shown that the disappearance of the disease from Gibraltar had synchronized with the 515 non-importation of goats from Malta; and preventive measures adopted in Malta in 1906, by banishing goats’ milk from the military and naval dietary, put a stop to the occurrence of cases. In the treatment of Malta fever a vaccine has been used with considerable success.

MALTE-BRUN, CONRAD (1755-1826), French geographer, was born on the 12th of August 1755 at Thisted in Denmark, and died at Paris on the 14th of December 1826. His original name was Malte Conrad Bruun. While a student at Copenhagen he made himself famous partly by his verses, but more by the violence of his political pamphleteering; and at length, in 1800, the legal actions which the government authorities had from time to time instituted against him culminated in a sentence of banishment. The principles which he had advocated were those of the French Revolution, and after first seeking asylum in Sweden he found his way to Paris. There he looked forward to a political career; but, when Napoleon’s personal ambition began to unfold itself, Malte-Brun was bold enough to protest, and to turn elsewhere for employment and advancement. He was associated with Edme Mentelle (1730-1815) in the compilation of the Géographie mathématique ... de toutes les parties du monde (Paris, 1803-1807, 16 vols.), and he became recognized as one of the best geographers of France. He is remembered, not only as the author of six volumes of the learned Précis de la géographie universelle (Paris, 1810-1829), continued by other hands after his death, but also as the originator of the Annales des voyages (1808), and one of the founders of the Geographical Society of Paris. His second son, Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun (1816-1889), followed his father’s career of geographer, and was a voluminous author.

MALTHUS, THOMAS ROBERT (1766-1834), English economist, was born in 1766 at the Rookery, near Guildford, Surrey, a small estate owned by his father, Daniel Malthus, a gentleman of good family and independent fortune, of considerable culture, the friend and correspondent of Rousseau and one of his executors. Young Malthus was never sent to a public school, but received his education from private tutors. In 1784 he was sent to Cambridge, where he was ninth wrangler, and became fellow of his college (Jesus) in 1797. The same year he received orders, and undertook the charge of a small parish in Surrey. In the following year he published the first edition of his great work, An Essay on the Principle of Population as it affects the Future Improvement of Society, with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other Writers. The work excited a good deal of surprise as well as attention; and with characteristic thoroughness and love of truth the author went abroad to collect materials for the verification and more exhaustive treatment of his views. As Britain was then at war with France, only the northern countries of Europe were quite open to his research at that time; but during the brief Peace of Amiens Malthus continued his investigations in France and Switzerland. The result of these labours appeared in the greatly enlarged and more mature edition of his work published in 1803. In 1805 Malthus married happily, and not long after was appointed professor of modern history and political economy in the East India Company’s College at Haileybury. This post he retained till his death suddenly from heart disease on the 23rd of December 1834. Malthus was one of the most amiable, candid and cultured of men. In all his private relations he was not only without reproach, but distinguished for the beauty of his character. He bore popular abuse and misrepresentation without the slightest murmur or sourness of temper. The aim of his inquiries was to promote the happiness of mankind, which could be better accomplished by pointing out the real possibilities of progress than by indulging in vague dreams of perfectibility apart from the actual facts which condition human life.

Malthus’s Essay on Population grew out of some discussions which he had with his father respecting the perfectibility of society. His father shared the theories on that subject of Condorcet and Godwin; and his son combated them on the ground that the realization of a happy society will always be hindered by the miseries consequent on the tendency of population to increase faster than the means of subsistence. His father was struck by the weight and originality of his views, asked him to put them in writing, and then recommended the publication of the manuscript. It was in this way the Essay saw the light. Thus it will be seen that both historically and philosophically the doctrine of Malthus was a corrective reaction against the superficial optimism diffused by the school of Rousseau. It was the same optimism, with its easy methods of regenerating society and its fatal blindness to the real conditions that circumscribe human life, that was responsible for the wild theories of the French Revolution and many of its consequent excesses.

The project of a formal and detailed treatise on population was an afterthought of Malthus. The essay in which he had studied a hypothetic future led him to examine the effects of the principle he had put forward on the past and present state of society; and he undertook an historical examination of these effects, and sought to draw such inferences in relation to the actual state of things as experience seemed to warrant. In its original form he had spoken of no checks to population but those which came under the head either of vice or of misery. In the 1803 edition he introduced the new element of the preventive check supplied by what he calls “moral restraint,” and is thus enabled to “soften some of the harshest conclusions” at which he had before arrived. The treatise passed through six editions in his lifetime, and in all of them he introduced various additions and corrections. That of 1816 is the last he revised, and supplies the final text from which it has since been reprinted.

Notwithstanding the great development which he gave to his work and the almost unprecedented amount of discussion to which it gave rise, it remains a matter of some difficulty to discover what solid contribution he has made to our knowledge, nor is it easy to ascertain precisely what practical precepts, not already familiar, he founded on his theoretic principles. This twofold vagueness is well brought out in his celebrated correspondence with Nassau Senior, in the course of which it seems to be made apparent that his doctrine is new not so much in its essence as in the phraseology in which it is couched. He himself tells us that when, after the publication of the original essay, the main argument of which he had deduced from David Hume, Robert Wallace, Adam Smith and Richard Price, he began to inquire more closely into the subject, he found that “much more had been done” upon it “than he had been aware of.” It had “been treated in such a manner by some of the French economists, occasionally by Montesquieu, and, among English writers, by Dr Franklin, Sir James Steuart, Arthur Young and Rev. J. Townsend, as to create a natural surprise that it had not excited more of the public attention.” “Much, however,” he thought, “remained yet to be done. The comparison between the increase of population and food had not, perhaps, been stated with sufficient force and precision,” and “few inquiries had been made into the various modes by which the level” between population and the means of subsistence “is effected.” The first desideratum here mentioned—the want, namely, of an accurate statement of the relation between the increase of population and food—Malthus doubtless supposed to have been supplied by the celebrated proposition that “population increases in a geometrical, food in an arithmetical ratio.” This proposition, however, has been conclusively shown to be erroneous, there being no such difference of law between the increase of man and that of the organic beings which form his food. When the formula cited is not used, other somewhat nebulous expressions are sometimes employed, as, for example, that “population has a tendency to increase faster than food,” a sentence in which both are treated as if they were spontaneous growths, and which, on account of the ambiguity of the word “tendency,” is admittedly consistent with the fact asserted by Senior, that food tends to increase faster than population. It must always have been perfectly well known that population will probably (though not necessarily) increase with every augmentation of the supply of subsistence, and may, in some instances, inconveniently press upon, or even for a certain time exceed, the number properly corresponding to that supply. Nor could it ever have been doubted that war, disease, poverty—the 516 last two often the consequences of vice—are causes which keep population down. In fact, the way in which abundance, increase of numbers, want, increase of deaths, succeed each other in the natural economy, when reason does not intervene, had been fully explained by Joseph Townsend in his Dissertation on the Poor Laws (1786) which was known to Malthus. Again, it is surely plain enough that the apprehension by individuals of the evils of poverty, or a sense of duty to their possible offspring, may retard the increase of population, and has in all civilized communities operated to a certain extent in that way. It is only when such obvious truths are clothed in the technical terminology of “positive” and “preventive checks” that they appear novel and profound; and yet they appear to contain the whole message of Malthus to mankind. The laborious apparatus of historical and statistical facts respecting the several countries of the globe, adduced in the altered form of the essay, though it contains a good deal that is curious and interesting, establishes no general result which was not previously well known.

It would seem, then, that what has been ambitiously called Malthus’s theory of population, instead of being a great discovery as some have represented it, or a poisonous novelty, as others have considered it, is no more than a formal enunciation of obvious, though sometimes neglected, facts. The pretentious language often applied to it by economists is objectionable, as being apt to make us forget that the whole subject with which it deals is as yet very imperfectly understood—the causes which modify the force of the sexual instinct, and those which lead to variations in fecundity, still awaiting a complete investigation.