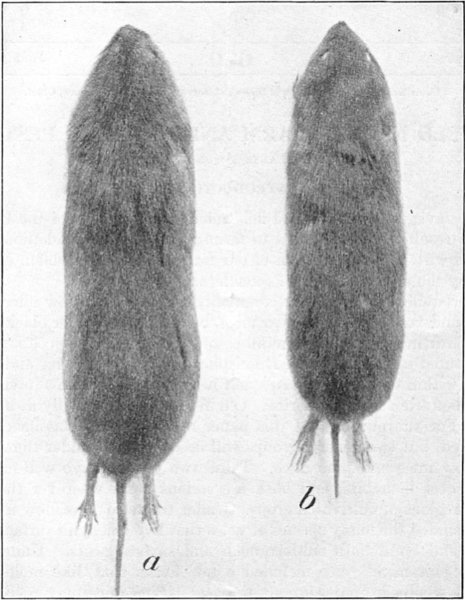

Fig. 1.—Field mice: a, Meadow mouse; b, pine mouse.

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

FARMERS' BULLETIN

Washington, D. C.670June 3, 1915.

Contribution from the Bureau of Biological Survey, Henry W. Henshaw, Chief.

By D. E. Lantz, Assistant Biologist.

Note.—This bulletin describes the habits, geographic distribution, and methods of destroying meadow mice and pine mice, and discusses the value of protecting their natural enemies among mammals, birds, and reptiles. It is for general distribution.

The ravages of short-tailed field mice in many parts of the United States result in serious losses to farmers, orchardists, and those concerned with the conservation of our forests, and the problem of controlling the animals is one of considerable importance.

Short-tailed field mice are commonly known as meadow mice, pine mice, and voles; locally as bear mice, buck-tailed mice, or black mice. The term includes a large number of closely related species widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere. Over 50 species and races occur within the United States and nearly 40 other forms have been described from North America. Old World forms are fully as numerous. For the purposes of this paper no attempt at classification is required, but two general groups will be considered under the names meadow mice and pine mice. These two groups have well-marked differences in habits, and both are serious pests wherever they inhabit regions of cultivated crops. Under the term "meadow mice"[1] are included the many species of voles that live chiefly in surface runways and build both subterranean and surface nests. Under the term "pine mice"[2] are included a few forms that, like moles, live almost wholly in underground burrows. Pine mice may readily be distinguished from meadow mice by their shorter and smoother fur, their red-brown color, and their molelike habits. (See fig. 1.)

[1] Genus Microtus.

[2] Genus Pitymys.

Fig. 1.—Field mice: a, Meadow mouse; b, pine mouse.

Meadow mice inhabit practically the whole of the Northern Hemisphere—America, north of the Tropics; all of Europe, except Ireland;[Pg 2] and Asia, except the southern part. In North America there are few wide areas except arid deserts free from meadow mice, and in most of the United States they have at times been numerous and harmful. The animals are very prolific, breeding several times a season and producing litters of from 6 to 10. Under favoring circumstances, not well understood, they sometimes produce abnormally and become a menace to all growing crops. Plagues of meadow mice have often been mentioned in the history of the Old World, and even within the United States many instances are recorded of their extraordinary abundance with accompanying destruction of vegetation.

The runs of meadow mice are mainly on the surface of the ground under grass, leaves, weeds, brush, boards, snow, or other sheltering litter. They are hollowed out by the animals' claws, and worn hard and smooth by being frequently traversed. They are extensive,[Pg 3] much branched, and may readily be found by parting the grass or removing the litter. The runs lead to shallow burrows where large nests of dead grass furnish winter retreats for the mice. Summer nests are large balls of the same material hidden in the grass and often elevated on small hummocks in the meadows and marshes where the animals abound. The young are brought forth in either underground or surface nests.

Meadow mice are injurious to most crops. They destroy grass in meadows and pastures; cut down grain, clover, and alfalfa; eat grain left standing in shocks; injure seeds, bulbs, flowers, and garden vegetables; and are especially harmful to trees and shrubbery. The extent of their depredations is usually in proportion to their numbers. Thus, in the lower Humboldt Valley, Nevada, during two winters (1906-8) these mice were abnormally abundant, and totally ruined the alfalfa, destroying both stems and roots on about 18,000 acres and entailing a loss estimated at fully $250,000.

When present even in ordinary numbers meadow mice cause serious injury to orchards and nurseries. Their attacks on trees are often made in winter under cover of snow, but they may occur at any season under shelter of growing vegetation or dry litter. The animals have been known almost totally to destroy large nurseries of young[Pg 4] apple trees. It was stated that during the winter of 1901-2 nurserymen near Rochester, N. Y., sustained losses from these mice amounting to fully $100,000.

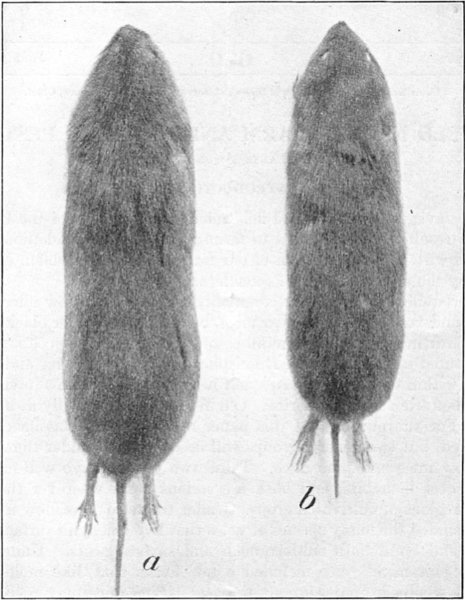

Older orchard trees sometimes are killed by meadow mice. In Kansas in 1903 the writer saw hundreds of apple trees, 8 to 10 years planted, and 4 to 6 inches in diameter, completely girdled by these pests. (Fig. 2.) The list of cultivated trees and shrubs injured by these animals includes nearly all those grown by the horticulturist. The Biological Survey has received complaints of the destruction of apple, pear, peach, plum, quince, cherry, and crab-apple trees, of blackberry, raspberry, rose, currant, and barberry bushes, and of grape vines; also of the injury of sugar maple, black locust, Osage orange, sassafras, pine, alder, white ash, mountain ash, oak, cottonwood, willow, wild cherry, and other forest trees.

Fig. 2.—Apple tree killed by meadow mice.

In the Arnold Arboretum, near Boston, Mass., during the winter of 1903-4, meadow mice destroyed thousands of trees and shrubs, including apple, juniper, blueberry, sumac, maple, barberry, buckthorn, dwarf cherry, snowball, bush honeysuckle, dogwood, beech, and larch. Plants in nursery beds and acorns and cuttings in boxes were especial objects of attack.

The injury to trees and shrubs consists in the destruction of the bark just at the surface of the ground and in some instances for several inches above or below. When the girdling is complete and the cambium entirely eaten through, the action of sun and wind soon completes the destruction of the tree. If the injury is not too extensive prompt covering of the wounds will usually save the tree. In any case of girdling heaping up fresh soil about the trunk so as to cover the wounds and prevent evaporation is recommended as the simplest remedy. To save large and valuable trees bridge grafting may be employed.

Pine mice occur over the greater part of eastern United States from the Hudson River Valley to eastern Kansas and Nebraska and from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. Inhabitants chiefly of for[Pg 5]ested regions, they are unknown on the open plains. Ordinarily they live in the woods, but are partial also to old pastures or lands not frequently cultivated. From woods, hedges, and fence rows they spread into gardens, lawns, and cultivated fields through their own underground tunnels or those of the garden mole. The tunnels made by pine mice can be distinguished from those made by moles only by their smaller diameter and the frequent holes that open to the surface.

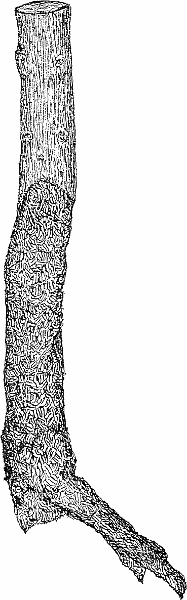

While the mole feeds almost wholly upon insects and earthworms, and seldom eats vegetable substances, pine mice are true rodents and live upon seeds, roots, and leaves. Their harmful activities include the destruction of potatoes, sweet potatoes, ginseng roots, bulbs in lawns, shrubbery, and trees. They destroy many fruit trees in upland orchards and nurseries (fig. 3). The mischief they do is not usually discovered until later, when harvest reveals the rifled potato hills or when leaves of plants or trees suddenly wither. In many instances the injury is wrongly attributed to moles whose tunnels invade the place or extend from hill to hill of potatoes. The mole is seeking earthworms or white grubs that feed upon the tubers, but mice that follow in the runs eat the potatoes themselves.

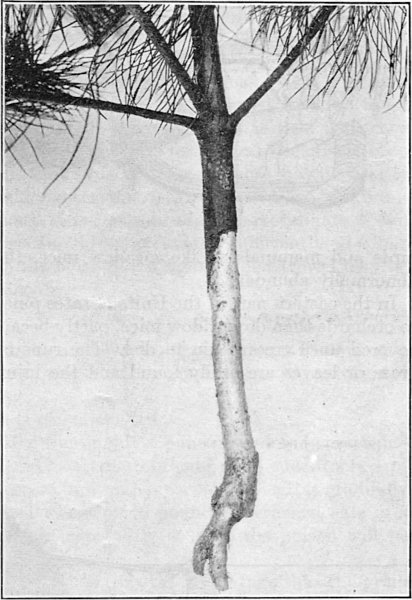

Fig. 3.—Root and trunk of apple tree from Laurel, Md., gnawed by pine mice.

Pine mice feed to some extent outside their burrows, reaching the surface through the small openings made at frequent intervals in the roofs of the tunnels. In their forays they rarely go more than a few feet from these holes. Most of their food is carried under ground, where much is stored for future consumption. While they differ[Pg 6] little from meadow mice in general food habits, their surroundings afford them a larger proportion of mast. They are less prolific than meadow mice, but this is more than made up for in the fact that in their underground life they are less exposed to their enemies among birds and mammals. Like meadow mice, they sometimes become abnormally abundant.

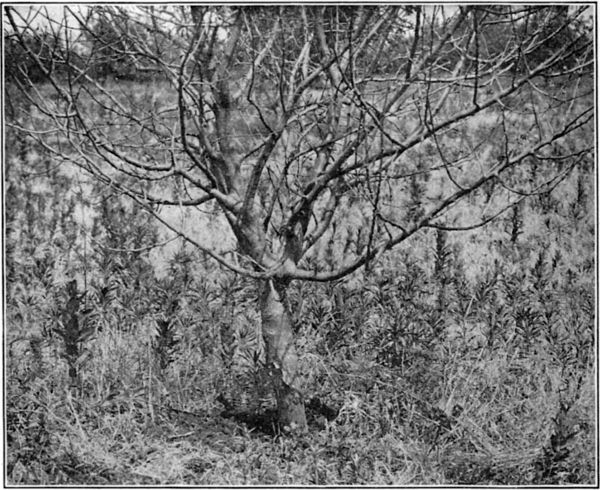

In the eastern part of the United States pine mice do more damage to orchards than do meadow mice, partly because their work is undiscovered until trees begin to die. The runs of meadow mice under grass or leaves are easily found and the injury they do to trees is always visible. On the other hand, depredations by pine mice can be found only after digging about the tree and exposing the trunk below the surface. The roots of small trees are often entirely eaten off by pine mice, and pine trees as well as deciduous forest trees, when young, are frequently killed by these animals (fig. 4).

Fig. 4.—Pine tree killed by pine mice.

Methods of destroying field mice or holding them in check by trapping and poisoning are equally applicable to meadow mice and pine mice.

If mice are present in small numbers, as is often the case in lawns, gardens, or seed beds, they may readily be caught in strong mouse traps of the guillotine type (figs. 5 and 6). These should be baited with oatmeal or other grain, or may be set in the mouse runs without bait.

Fig. 5.—Field mouse caught in baited guillotine trap.

Fig. 6.—Field mouse caught in unbaited guillotine trap.

Trapping has special advantages for small areas where a limited number of mice are present, but it is also adapted to large areas whenever it is undesirable to lay out poison. It is then necessary to use many traps and continue their use for several weeks. If mice are moderately abundant, from 12 to 20 traps per acre maybe used to advantage. These should soon make decided inroads on the numbers of mice in an orchard if not practically to exterminate them. For pine mice the tunnels should be excavated sufficiently to admit the trap on a level with the bottom. A light garden trowel may be used for the necessary digging.

On large areas where mice are abundant, poisoning is the quickest means of destroying them, and even on small areas it has decided advantages over trapping.

The following formula is recommended:

Dry grain formula.—Mix thoroughly 1 ounce powdered strychnine (alkaloid), 1 ounce powdered bicarbonate of soda, and 1⁄8 ounce (or less) of saccharine. Put the mixture in a tin pepper box and sift it gradually over 50 pounds of crushed wheat or 40 pounds of crushed oats in a metal tub, mixing the grain constantly so that the poison will be evenly distributed.

Dry mixing, as above described, has the advantage that the grain may be kept any length of time without fermentation. If it is desired to moisten the grain to facilitate thorough mixing, it would be well to use a thin starch paste (as described below, but without strychnine) before applying the poison. The starch soon hardens and fermentation is not likely to follow.

If crushed oats or wheat can not be obtained, whole oats may be used, but they should be of good quality. As mice hull the oats before eating them, it is desirable to have the poison penetrate the kernels. A very thin starch paste is recommended as a medium for applying poison to the grain. Prepare as follows:

Wet grain formula.—Dissolve 1 ounce of strychnia sulphate in 2 quarts of boiling water. Dissolve 2 tablespoonfuls of laundry starch[Pg 8] in ½ pint of cold water. Add the starch to the strychnine solution and boil for a few minutes until the starch is clear. A little saccharine may be added if desired, but it is not essential. Pour the hot starch over 1 bushel of oats in a metal tub and stir thoroughly. Let the grain stand overnight to absorb the poison.

The poisoned grain prepared by either of the above formulas is to be distributed over the infested area, not more than a teaspoonful at a place, care being taken to put it in mouse runs and at the entrances of burrows. To avoid destroying birds it should whenever possible be placed under such shelters as piles of weeds, straw, brush, or other litter, or under boards. Small drain tiles, 1½ inches in diameter, have sometimes been used to advantage to hold poisoned grain, but old tin cans with the edges bent nearly together will serve the same purpose.

Chopped alfalfa hay poisoned with strychnine was successfully used to destroy meadow mice in Nevada during the serious outbreak of the animals in 1907-8. One ounce of strychnia sulphate dissolved in 2 gallons of hot water was found sufficient to poison 30 pounds of chopped alfalfa previously moistened with water. This bait, distributed in small quantities at a place, was very effective against the mice, and birds were not endangered in its distribution.

For poisoning mice in small areas, as lawns, gardens, seed beds, vegetable pits, and the like, a convenient bait is ordinary rolled oats. This may be prepared as follows: Dissolve 1⁄16 ounce of strychnine in 1 pint of boiling water and pour it over as much oatmeal (about 2 pounds) as it will wet. Mix until all the grain is moistened. Put it out, a teaspoonful at a place, under shelter of weed and brush piles or wide boards.

The above poisons are adapted to killing pine mice, but sweet potatoes cut into small pieces have proved even more effective. They keep well in contact with soil except when there is danger of freezing, and are readily eaten by the mice. The baits should be prepared as follows:

Potato formula.—Cut sweet potatoes into pieces about as large as good-sized grapes. Place them in a metal pan or tub and wet them with water. Drain off the water and with a tin pepper box slowly sift over them powdered strychnine (alkaloid preferred), stirring constantly so that the poison is evenly distributed. An ounce of strychnine should poison a bushel of the cut bait.

The bait, whether of grain or pieces of potato, may be dropped into the pine-mouse tunnels through the natural openings or through holes made with a piece of broom handle or other stick. Bird life will not be endangered by these baits.

Thorough cultivation of fields and the elimination of fence rows between them is the most effective protection against field mice.[Pg 9] Cultivation destroys weeds and all the annual growths that serve as shelter for the animals. This applies equally well to orchards and nurseries. Clean tillage and the removal from adjoining areas of the weeds and grass that provide hiding places for mice will always secure immunity to trees from attacks of the animals.

Field mice are the prey of many species of mammals, birds, and reptiles. Unfortunately, the relation that exists between the numbers of rodents and the numbers of their enemies is not generally appreciated; otherwise the public would exercise more discrimination in its warfare against carnivorous animals. It is the persistent destruction of these, the beneficial and harmful alike, that has brought about the present condition of growing scarcity of predacious mammals and birds and corresponding increase of rodent pests of the farm, especially rats and mice. The relation between effect and cause is obvious.

Among the mammalian enemies of meadow and pine mice are coyotes, wildcats, foxes, badgers, raccoons, opossums, skunks, weasels, shrews, and the domestic cat and dog. Among birds, their enemies include nearly all the hawks and owls, storks, ibises, herons, cranes, gulls, shrikes, cuckoos, and crows. Among their reptilian foes are black snakes and bull snakes. Not all these destroyers of mice are more beneficial than harmful, but the majority are, and warfare against them should be limited to the minority that are more noxious than useful.

Owls as destroyers of mice are deserving of special mention. Not one of our American owls, unless it be the great horned owl, is to be classed as noxious. Especially beneficial are the short-eared, long-eared, screech, and barn owls. All these prey largely upon field mice, and seldom harm birds. Unfortunately, the short-eared and barn owls, which are the more useful species, are not plentiful in the sections most seriously infested by field mice.

The short-eared owl, while widely distributed, is not abundant, except locally, within the United States, but wherever field mice become excessively numerous these owls usually assemble in considerable numbers to prey upon them. Examinations of stomachs of these owls show that fully three-fourths of their food consists of short-tailed field mice.

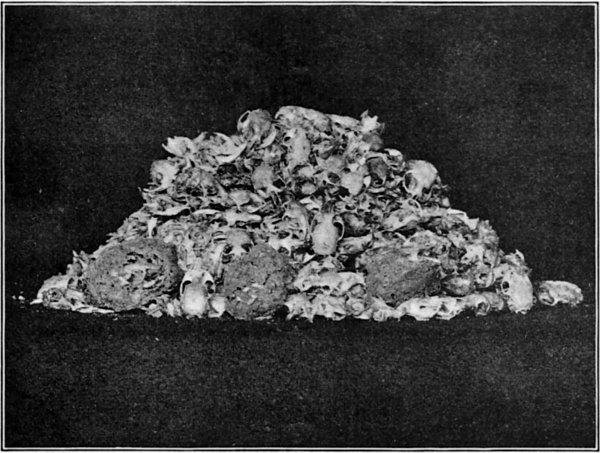

The barn owl is rather common in the southern half of the United States and breeds as far north as the forty-first parallel of latitude. That mice form the chief diet of this bird has been demonstrated by Dr. A. K. Fisher, of the Biological Survey, through examination of stomachs of many barn owls and also of large numbers of pellets (castings from their stomachs) found under their roosts. In 1,247[Pg 10] barn-owl pellets collected in the towers of the Smithsonian Building in Washington, D. C., he found 1,991 skulls of short-tailed field mice, 656 of the house mouse, 210 of the common rat, and 147 of other small rodents and shrews. Very few remains of birds were found. Figure 7 illustrates the contents of some of these pellets.

Fig. 7.—Field-mouse skulls taken from pellets found under owl roost in Smithsonian tower, Washington, D. C.

In 360 pellets of the long-eared owl Dr. Fisher found skulls of 374 small mammals, of which 349 were meadow mice. Stomach examinations give similar testimony to the usefulness of this bird.

The common screech owl, in addition to feeding mainly upon mice, destroys also a good many English sparrows. Its habit of staying in orchards and close to farm buildings makes it especially useful to the farmer in keeping his premises free from both house and field mice.

WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1915

Transcriber's Note:

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible.