Transcriber's Notes

Volume I of this eBook is available at Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41979, eText # 41979.

On some devices, clicking on a blue-bordered image will display a larger version of it.

BY

STEPHEN M. OSTRANDER, M.A.

LATE MEMBER OF THE HOLLAND SOCIETY, THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY, AND THE SOCIETY OF OLD BROOKLYNITES

EDITED, WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES, BY

ALEXANDER BLACK

AUTHOR OF "THE STORY OF OHIO," ETC.

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOLUME II.

BROOKLYN

Published by Subscription

1894

Copyright, 1894,

By ANNIE A. OSTRANDER.

All rights reserved.

This Edition is limited to Five Hundred Copies, of which this is No. 21.

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| BROOKLYN AFTER THE REVOLUTION | ||

| 1784–1810 | ||

| Effect of the British Occupation on Life and Business in the County. Brooklyn particularly disturbed. Town Meetings resumed. The Prison Ships and their Terrible Legacy. Tragedies of the Wallabout. Movement to honor the Dead. Burial of the Remains. The Tammany Enterprise and the Removal of the Bones. Further Removal to Fort Greene. Organization of the Brooklyn Fire Department. The Ferry. The Mail Stage. New Roads. Planning "Olympia." Early Advertisements. Circulating Library and Schools. The Rain-water Doctor. Kings County Medical Society. Flatlands. Gravesend. Flatbush, the County Seat. Mills. Erasmus Hall. New Utrecht. Bushwick, its Church, Tavern, Graveyard, and Mills. The Boundary Dispute. The Beginnings of Williamsburgh. Rival Ferries. "The Father of Williamsburgh" | 1 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| BROOKLYN VILLAGE | ||

| 1811–1833 | ||

| Brooklyn during the "Critical Period" in American History. The Embargo and the War of 1812. Military Preparations. Fortifications. Fort Greene and Cobble Hill. Peace. Robert Fulton. The "Nassau's" First Trip. Progress of Fulton Ferry. The Village incorporated. First Trustees. The Sunday-School Union. Long Island Bank. Board of Health. The [iv] Sale of Liquor. Care of the Poor. Real Estate. Village Expenses. Guy's Picture of Brooklyn in 1820. The Village of that Period. Characters of the Period. Old Families and Estates. The County Courts removed to Brooklyn. Apprentices' Library. Prisoners at the Almshouse. Growth of the Village. The Brooklyn "Evening Star." Movement for Incorporation as a City. Opposition of New York. Passage of the Incorporation Act | 47 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| THE CITY OF BROOKLYN | ||

| 1834–1860 | ||

| Government of the City. George Hall, first Mayor. Plans for a City Hall. Contention among the Aldermen. Albert G. Stevens and the Clerkship. The Jamaica Railroad. Real Estate. The "Brooklyn Eagle." Walt Whitman. Henry C. Murphy. Brooklyn City Railroad. The City Court established. County Institutions. The Penitentiary. Packer Institute and the Polytechnic. Williamsburgh becomes a City. Progress of Williamsburgh. Mayor Wall and the Aldermen. Discussion of Annexation with Brooklyn. The "Brooklyn Times." Consolidation of the Two Cities. Mayor Hall's Address. Nassau Water Company and the Introduction of Ridgewood Water. Plans for New Court House. Proposal to use Washington Park. County Cares and Expenditures. Metropolitan Police | 80 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| THE PERIOD OF THE CIVIL WAR | ||

| 1861–1865 | ||

| Election of Mayor Kalbfleisch. The Call for Troops. The Militia. Filling the Regiments. Money for Equipment. Rebuking Disloyalty. War Meeting at Fort Greene. Work of Women. The County sends 10,000 Men in 1861. Launching of the Monitor at Greenpoint. The Draft Riots. Colonel Wood elected Mayor. Return of the "Brooklyn[v] Phalanx." The Sanitary Fair. Its Features and Successes. The Calico Ball. Significance of the Fair. The Christian Commission. Action of the Supervisors of the County. The Oceanus Excursion. Storrs and Beecher at Sumter. News of Lincoln's Death. Service of the National Guard. The "Fighting Fourteenth." The Newspapers. Court House finished | 117 | |

| CHAPTER XIII | ||

| BROOKLYN AFTER THE WAR | ||

| 1866–1876 | ||

| Administration of Samuel Booth. Metropolitan Sanitary District created. Cholera. Erie Basin Docks. The County Institutions and their Work. The Gowanus Canal and the Wallabout Improvement. The Department of Survey and Inspection of Buildings. Establishing Fire Limits. Building Regulations. Prospect Park. The Ocean Parkway. The Fire Department. The Public Schools. The East River Bridge. Early Discussion of the Great Enterprise. The Construction begun. Death of Roebling. The Ferries. Messages of Mayor Kalbfleisch. Erection of a Brooklyn Department of Police. Samuel S. Powell again Mayor. A New City Charter. Movement toward Consolidation with New York. Henry Ward Beecher. Frederick A. Schroeder elected Mayor | 132 | |

| CHAPTER XIV | ||

| THE MODERN CITY | ||

| 1877–1893 | ||

| Rapid Transit. James Howell, Jr., elected Mayor. Work on the Bridge. Passage of "Single Head" Bill. John Fiske on the "Brooklyn System." Seth Low elected Mayor. His Interpretation of the "Brooklyn System." Reëlection of Low. Opening of the Bridge. Bridge Statistics. Ferries and Water Front. Erie Basin. The Sugar Industry. Navy Yard. Wallabout Market. Development of the City. Prospect Park. Theatres and Public Buildings. National Guard. Public Schools. Brooklyn[vi] Institute. Private Educational Institutions. Libraries. Churches, Religious Societies, Hospitals, and Benevolent Associations. Clubs. Literature, Art, and Music. The Academy of Music. "The City of Homes" | 167 | |

| Appendix | 235 | |

| Index | 271 | |

VOLUME II

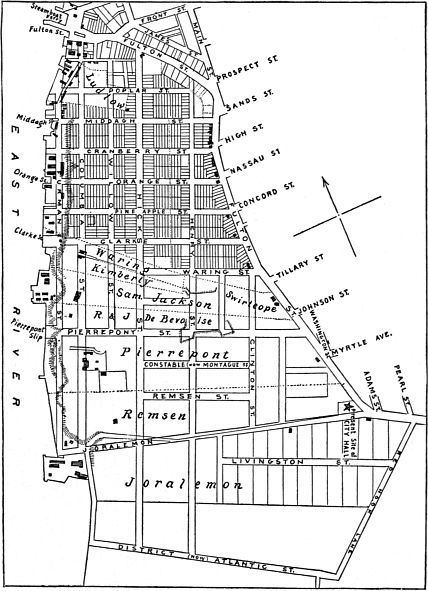

| Village of Brooklyn in 1816. (From the Village Map of Jeremiah Lott, 1816, and the Map by Poppleton and Lott in 1819, showing Pierrepont and adjacent Estates) | Frontispiece | |

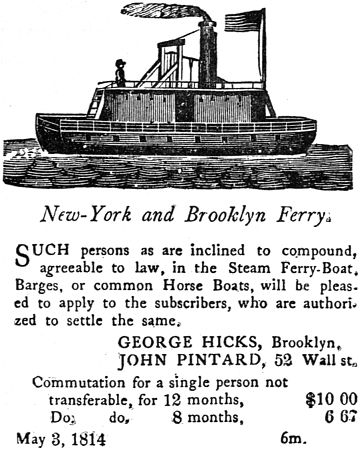

| Early Ferry Advertisement. (From Historical Sketch of Fulton Ferry and its Associated Ferries, 1879) | Facing page | 28 |

| Ferry Passage Certificate, 1816 | 40 | |

| Fulton Ferry Boat Wm. Cutting, built in 1827. (From Historical Sketch of Fulton Ferry) | 62 | |

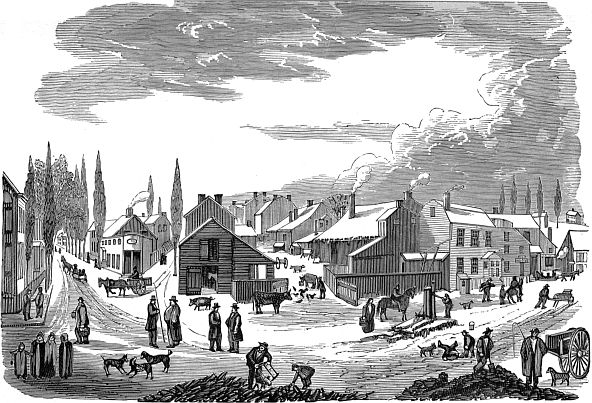

| Guy's Snow Scene in Brooklyn, 1820. (From the Painting owned by the Brooklyn Institute) | 70 | |

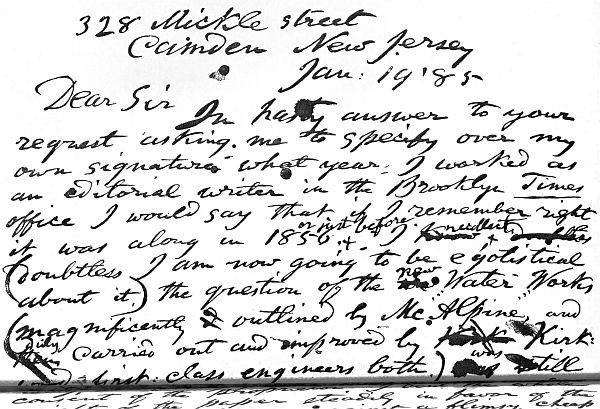

| Fac-Simile (same size) of Letter by Walt Whitman in Possession of Charles M. Skinner, Esq., Brooklyn | 90 | |

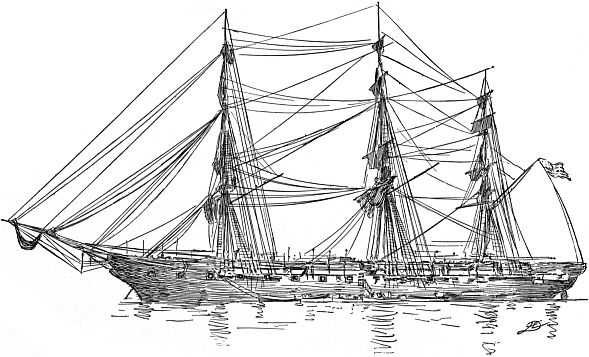

| Cruiser Brooklyn, built in 1858 | 122 | |

| Statue of Henry Ward Beecher in front of City Hall. (From a Drawing by H. D. Eggleston) | 140 | |

| Statue of J. S. T. Stranahan at the Entrance to Prospect Park. (From a Drawing by H. D. Eggleston) | 180 | |

| Statue of Alexander Hamilton in front of Hamilton Club House | 200 | |

| APPENDIX | ||

| Chart showing East River Soundings and Pier Lines | 262 | |

Effect of the British Occupation on Life and Business in the County. Brooklyn particularly disturbed. Town Meetings resumed. The Prison Ships and their Terrible Legacy. Tragedies of the Wallabout. Movement to honor the Dead. Burial of the Remains. The Tammany Enterprise and the Removal of the Bones. Further Removal to Fort Greene. Organization of the Brooklyn Fire Department. The Ferry. The Mail Stage. New Roads. Planning "Olympia." Early Advertisements. Circulating Library and Schools. The Rain-water Doctor. Kings County Medical Society. Flatlands. Gravesend. Flatbush, the County Seat. Mills. Erasmus Hall. New Utrecht. Bushwick, its Church, Tavern, Graveyard, and Mills. The Boundary Dispute. The Beginnings of Williamsburgh. Rival Ferries. "The Father of Williamsburgh."

During the whole period of the Revolution Brooklyn had been peculiarly disturbed. More than any other of the county towns, it had been distracted and prostrated. Farms had been pillaged and the property of exiled Whigs[2] given over to Tory friends of the Governor. Military occupation naturally resulted in great damage to property. "Farmers were despoiled of their cattle, horses, swine, poultry, vegetables, and of almost every necessary article of subsistence, except their grain, which fortunately had been housed before the invasion. Their houses were also plundered of every article which the cupidity of a lawless soldiery deemed worthy of possession, and much furniture was wantonly destroyed. At the close of this year's campaign, De Heister, the Hessian general, returned to Europe with a shipload of plundered property."1 While the other towns were receiving pay for the board of prisoners, and thus being justified in maintaining their crops, Brooklyn remained a garrison town until the end.

After the evacuation, Brooklyn's farmers and tradesmen at once turned their attention to the restoration of the orderly conditions existing before the war. It also became necessary to reorganize the local government. In April, 1784, was held the first town meeting since April, 1776. Jacob Sharpe was chosen town clerk, and Leffert Lefferts, the previous clerk, was called upon to produce the town[3] records. The result of this demand has already been described in the reference to the missing records.

Before proceeding further with the narrative of Brooklyn's growth after the Revolution, it will be necessary to return for a moment to certain sad circumstances that followed the battle of Brooklyn and other successes of the British. The battle of Long Island was fought August 27, 1776, and Fort Washington was captured in November. These victories gave the British between 4000 and 5000 prisoners. At that time there were only two small jails in New York city. One was called the Bridewell, and was situated in Broadway near Chambers Street, and the other was known as the New Jail. These prisons could not accommodate the daily increasing number of prisoners. It was a dark hour in American history; success seemed to perch upon the banners of the enemy. Large accessions of prisoners were made, and quarters had to be provided for them. The churches were taken without ceremony and converted into receptacles for the captives. The sugar-houses were used for the same purpose. One of these was situated in Liberty Street, adjoining the old Middle Dutch Church. That church was also used. Within its walls[4] thousands of prisoners were placed, regardless of comfort or sanitary rules. If its walls could speak they would tell a tale which would make a sad record.

The old North Dutch Church on the corner of Fair Street and Horse and Cart Lane (now Fulton and William streets) was also used as a prison pen, and within its walls a thousand persons were held. Within a few years this venerable landmark has succumbed to the march of progress.

The infamous Cunningham was at this time provost marshal of the city. He possessed the instincts of a brute, and often seemed to own the spirit of a demon. The sick and dying received no sympathy or care from him. Healthy men were placed in the same room with those having the smallpox and other maladies. Prisoners were not allowed sufficient food or bedding, and their clothes were scanty. The food was not fit to give to the beasts. The men must have reached the verge of starvation to induce them to partake of the unwholesome mess of wormy and mouldy food dealt out to them. The allowance made to the men was a loaf of bread, one quart of peas, half a pint of rice, and one and a half pounds of pork for six days. Large numbers[5] died from want, privation, and exhaustion. So crowded were these prisons that there was no room to lie down and rest. The impure atmosphere engendered disease. Every morning the cry was heard, "Rebels, bring out your dead." All who had died during the night were carelessly thrown into the dead-cart and carried to the trenches in the neighborhood of Canal Street, and buried without a vestige of ceremony.

But the horrors of the city prisons were more than repeated in the tragedies of the prison ships in the bend of the Wallabout. The first vessels used were the freight transports which had been employed in conveying troops to Staten Island in 1776. These transports were for a short time anchored in Gravesend Bay, and received the prisoners taken on Long Island. When New York was conquered they were removed to the city. The Good Hope and Scorpion for a while were anchored off the Battery, and subsequently were taken to Wallabout Bay, and with other vessels were used as prisons. Two vessels at a time were kept in this service. Among the vessels thus used were the Whitley, Falmouth, Prince of Wales, Scorpion, Bristol, and Old Jersey.

[6] In 1780 one of the vessels was burned by the unhappy captives, who hoped thereby to regain their liberty. The effort was unsuccessful, and the prisoners were removed to the Old Jersey, which continued in service until the end of the war.

Wallabout Bay had the shape of a horse-shoe. The Jersey was anchored at a point which is now represented by the west end of the Cob Dock. If Cumberland Street were continued in a straight line to a point between the Navy Yard proper and the Cob Dock, it would pass over the spot where this vessel was anchored.

Historians agree in saying that the treatment on all these vessels was alike, and that the Jersey was not exceptional. The Jersey was the largest of all, and having remained in service for so long a time had the most prisoners. On that account she has attracted the most attention.

The crew on board each ship consisted of a captain, mates, steward, a few sailors and marines, and about thirty soldiers. Each prisoner on his arrival was carefully searched for arms and valuables. His name and rank were duly registered. He was allowed to retain his clothing and bedding, and to use these,[7] but during confinement was supplied with nothing additional. The examination having been completed, he was conducted to the hold of the vessel, to become the companion of a thousand other patriots, many of whom were covered with rags and filth, and pale and emaciated from the constant inhalation of the pestiferous and noxious atmosphere which impregnated the vessel. Strong men could not long resist inroads of sickness and disease. Many were taken down with typhus fever, dysentery, and smallpox. The vessel was filled continually with the vilest malaria. The guns were removed, portholes securely fastened, and in their place were two tiers of lights to admit air. Each of these air holes was about twenty inches square, and fastened by cross-bars to prevent escape. The steward supplied each mess with a daily allowance of biscuit, pork or beef, and rancid butter. The food was of the poorest which could be obtained, and of itself was sufficient to breed disease. The biscuits were mouldy and worm-eaten, the flour was sour, and the meat badly tainted. It was cooked in a common kettle, which was never cleaned, with impure water, and became a slow but sure poison. The prisoners were kept in the holds between the two decks, and the[8] lower dungeon was used for the foreigners who had enlisted in freedom's cause. Here again the morning salutation was, "Rebels, bring out your dead." The command was obeyed, and all who had found relief in death were brought upon deck. Prisoners were allowed to sew a blanket over the remains of their dead companions before burial. The dead were taken in boats to the shore, put in holes dug in the sand, and carelessly covered. Frequently they were washed from their resting place by the incoming tide. Often while walking along the old Wallabout road, between Cumberland Street and the Navy Yard, I have seen the remains of the gallant patriots who lost their lives on the Jersey. In the "'fifties" of the present century it was no uncommon thing for pieces of bone and human skulls to be dug up on the borders of the old road.

The only relief the prisoners had was permission to remain on deck until sunset. When the golden orb of day sunk beneath the horizon, the ears of all were saluted with the obnoxious cry, "Down, rebels, down." When all had retired to the hold, the hatchway was closed, leaving only a small trap open to admit air. At this trapdoor a sentinel was placed, with instructions to allow but one man[9] to ascend at a time during the night. The sentinels possessed the same cruel spirit as their masters. A prisoner who had been confined on the Jersey for fourteen months said that, on occasions when the prisoners gathered at the hatchway to obtain fresh air, the sentinel repeatedly thrust his bayonet among them and killed several. These acts created a desire for revenge. Many of the men were enabled to endure their trials by the thought that the night of darkness would soon pass away, and the day dawn when they could take vengeance on the scoundrels who had treated them with so much brutality.

An instance of this determination to be revenged is narrated in the life of Silas Talbot. It appears that two brothers belonging to the same rifle corps were made prisoners and sent on board the Jersey. The elder was attacked with fever and became delirious. One night, as his end was fast approaching, reason resumed its sway, and, while lamenting his sad fate and breathing a prayer for his mother, he begged for a little water. His brother entreated the guard to give him some, but the request was brutally refused. The sick boy drew near to death, and his last struggle came. The brother offered the guard a guinea for an[10] inch of candle to enable him to behold the last gasping smile of love and affection. This request was refused. "Now," said he, "if it please God that I ever regain my liberty, I'll be a most bitter enemy." He soon after became a free man, and, to show how well he kept his word, it is only necessary to say that when the war closed "he had 8 large and 127 small notches in his rifle stock." These notches probably represented 8 officers and 127 privates.

On one occasion 130 men were brought to the Jersey by the villain Sprout, who was commissary of prisoners. As he approached the black unsightly hulk, he pointed to her sardonically, and told his captives, "There, rebels, there is the cage for you."

The same bitter round was the daily portion of the men,—during the day a little air and sunlight, and being compelled to listen to the curses and imprecations of their captors, while at night they had to breathe the stifling air between decks, and listen to the groans of the sick and dying, without the power to give them any relief.

Some of the men were assigned to wash and scrub the decks. This of itself was a great blessing, as it gave them occupation and[11] additional rations. During the night watches it was as dark as Egypt between decks, for no sort of light was allowed. Delirious men would wander about and stumble over their fellows. Sometimes the warning shout would be heard, that a madman was creeping in the darkness with a knife in his hand. At times a soldier would wake up to find that the brother at his side had become a corpse. The soldiers in charge of the prisoners were mostly Hessians, and were universally hated as mercenaries.

Yet no amount of cruelty could drive patriotism from the hearts of the captives. On the 4th of July, 1782, they determined to celebrate the anniversary in a fitting manner. On the morning of that day, they came on deck with thirteen national flags, fastened on brooms. The flags were seized, torn, and trampled under foot by the guards, who looked upon the act as an insult. Nothing daunted, the men determined to have their pleasure, and began to sing national melodies. The guards became enraged, considered themselves insulted, and drove the prisoners below at an early hour, at the point of the bayonet, and closed the hatches. The prisoners again commenced to sing. At nine o'clock in the evening an[12] order was given requiring them to cease. This order not being instantly complied with, the animosity of the guards was aroused, and they descended with lanterns and lances. Terror and consternation at once reigned supreme. The retreating prisoners were sorely pressed by the guards, who unmercifully cut and slashed away, wounding every one within their reach, and inflicting in many instances deadly blows. They then returned to the deck, leaving the wounded to suffer, without the means to have their wounds properly dressed. In consequence of this explosion of patriotism, a new torture was devised. The men, as a punishment, were kept below on the following day until noon, and thus were prevented from the enjoyment of the sun and air for six long weary hours. During this time they were also deprived of rations and water. As a result of the night's diabolism ten dead bodies were brought on deck in the morning.

To show the heartlessness of the guards, an incident is narrated of a man who was supposed to be dead, and had been sewed up in his hammock and carried on deck preparatory to burial. He was observed to move, and the attention of the officer in charge was called to the fact that he was still living. "In with[13] him," said the officer; "if he is not dead, he soon will be." The sailor took a knife, cut open the hammock, and discovered that the man was still alive. Doubtless many men who had swooned away were buried alive.

At the time of these occurrences, the government did not possess the ability to make exchanges. The captives on the prison ships were mostly privateersmen, and, not being in the regular Continental service, Congress was unwilling to restore healthy soldiers to the ranks of the enemy, thereby adding to their strength without a full and exact equivalent.

The Americans had entered into an agreement to exchange officer for officer and soldier for soldier. They had but few naval prisoners, and thus could make no exchange for the unfortunate ones on these ships. Our authorities were compelled to let their captives on the water go at large, for want of suitable places to keep them. Washington took a lively interest in the matter, and entered into a correspondence with Henry Clinton and Admiral Digby on the subject, threatening retaliation. He, however, threatened and expostulated in vain.

The American rebels were urged by the British officers to enter their service. Some did enlist, with the hope uppermost in their minds that they would be able to desert.

[14] The prisoners were released at the close of the war. The old Jersey was destroyed, and its decaying timbers became buried in the mud.

The bones of the prison-ship martyrs lay for many years bleaching on the banks of Wallabout Bay, where they had been rudely buried by the British. The action of the tide upon the sandy banks gradually washed away the little earth which had been thrown over them, thereby causing the sacred relics to become exposed to view. The attention of Congress was frequently called to the necessity of providing a suitable resting place for these honored remains. The sight of these bones strewn upon the banks of the bay was enough to awaken the interest of the nation. At last the citizens of Brooklyn became aroused, and at a town meeting held in 1792, a resolution was passed requesting John Jackson, who had collected a large number of the bones on his farm, which then included the land now used by the Navy Yard, to allow the relics in his possession and under his control to be removed to the Reformed Dutch Church graveyard for burial, and a monument erected over them. General Jeremiah Johnson was the chairman of the committee. The application was refused, Jackson having other intentions as to[15] their interment. Jackson was a blunt man, and a firm believer in the principles of Democracy as enunciated by Jefferson. He was one of the sachems of the Tammany Society or Columbian Order.

He had several hogsheads full of bones which he had collected upon the beach. To consummate his plan he offered to the Tammany Society a plot in his farm for land whereon a suitable monument might be erected.

Tammany accepted the trust, and in February, 1803, entered actively upon the work. The society at once proposed and caused to be presented to Congress a stirring and forcible memorial on the subject. Congress, however, came to no determination in the matter, and the matter remained quiescent until 1808. Between the time of the acceptance of the offer by Tammany and the action by Congress in 1808, Benjamin Aycrigg, a prominent and influential citizen, became greatly interested in the measure. In the summer of 1805, noticing the exposed condition of these remains on the beach of the bay, his patriotic heart was horrified by the sight; his soul was filled with indignation that steps had not been taken to have them decently interred. He, in the same year, made a contract with an Irishman living at[16] the Wallabout to collect all the exposed bones. The remains thus collected formed a part of those subsequently placed in the vault erected on the Jackson lot by the Tammany Society.

In 1808 Tammany again renewed its labors. At a meeting of the society a committee was appointed, called the Wallabout Committee, consisting of Jacob Vandervoort, John Jackson, Burdett Stryker, Issachar Cozzens, Robert Townsend, Jr., Benjamin Watson, and Samuel Coudrey. This committee was deeply interested in the work, and used every available means to enlist public sympathy and assistance. Memorials were prepared and circulated, and appeals made through the press and otherwise, urging the citizens to come forward and aid the sacred cause. In their efforts they did not confine themselves to New York, but sought to create a national interest in the undertaking. The patriotism of the people was appealed to, and the effort was crowned with success. When the subject was thus forcibly presented, the citizens of the young republic realized their obligation to provide a proper burial place for the dust and bones of her brave sons, through whose death the nation rose into existence. The measure was presented in a way which could not be resisted.[17] The inhabitants of all sections became greatly interested, and nobly responded to the call, and the committee, finding so many ready to aid, assist, and approve, were enabled to commence the erection of the structure much sooner than they had at first anticipated.

The spot given was situated in Jackson Street (now Hudson Avenue), near York Street, abutting the Navy Yard wall. The street was named after the owner of the land. The name was afterward changed to Hudson Avenue.

The land was formally deeded by Jackson to the Tammany Society in 1803. When all things were ready the society caused the remains collected by Jackson, with all the bones found upon the beach, to be committed to the tomb with appropriate ceremonies.

The arrangements for laying the corner-stone were completed, and the 13th of April, 1808, fixed for that interesting ceremony. The order of exercises was as follows: At eleven o'clock the procession formed at the ferry, foot of Main Street, marched through that street to Sands Street, thence to Bridge Street, along Bridge to York Street, through York Street to Jackson, and thence to the ground.

As Major Aycrigg had ever manifested unabated interest in this labor of love, he was properly selected as grand marshal of the day.

[18] The first division of the procession consisted of a company of United States marines, under command of Lieutenant-Commandant Johnson. The second division was composed of citizens of New York and Brooklyn. The third division embraced the committees of the various civic societies. The fourth division contained the Grand Sachem of the Tammany Society, Father of the Council, and orator of the day. The fifth division carried the corner-stone with the following inscription:—

In the Name of

the Spirits of the Departed Free.

Sacred to the memory of that portion of

American Freemen, Soldiers and Citizens,

who perished on board the

Prison Ships of the British

at the Wallabout during the

Revolution.

This corner-stone of the vault erected by the

Tammany Society

or Columbian OrderNassau Island, Season of Blossoms, year of the discovery the 316th, of the institution the 19th, and of the American Independence the 22d.

Jacob Vandervoort, } Wallabout

CommitteeJohn Jackson, } Burdett Stryker, } Issachar Cozzens, } Robert Townsend, Jr., } Benjamin Watson, } Samuel Coudrey, } Daniel and William Campbell, builders, April 6, 1808.

[19] The sixth division was composed of a detachment of artillery under command of Lieutenant Townsend.

The procession having reached the ground, the artillery were stationed upon a neighboring hill, and the various divisions took the positions assigned them.

The oration, which was a brilliant effort, was delivered by Joseph D. Foy. The stone was then lowered to its place and duly laid by Benjamin Romaine, Grand Sachem of the Tammany Society, assisted by the committee, after which a grand salute was fired, and the band discoursed sweet and solemn notes.

The vault was completed in May, 1808. Arrangements were made for an imposing display, and no pains were spared in preparation. The various societies and public bodies were ready and anxious to do all in their power to render the occasion impressive and memorable. The citizens turned out en masse on the 26th of May, 1808, to bear testimony to the worth of these brave men whose obsequies were to be celebrated. They assembled at ten o'clock in the park in front of the City Hall, New York, under command of Brigadier Generals Morton and Steddiford, Garret Sickels, Grand Marshal, assisted by twelve aides.

[20] The inscription on the pedestal was as follows:—

[Front.]

Americans remember the British.

[Right side.]

Youth of my Country

Martyrdom Preferred to Slavery.

[Left side.]

Sires of Columbia

transmit to posterity the cruelties practiced on board the

"British Prison Ships."

[Rear.]

"Tyrants dread the gathering storm

While Freemen, Freemen's Obsequies perform."

The orator of the day was Dr. Benjamin DeWitt, who delivered an able and patriotic address to the assembled multitude. He feelingly depicted the sufferings endured in British dungeons, and drew tears to many eyes by his eloquent and touching remarks, referring to the tyranny of the oppressors and the patience of the patriots. The oration concluded, in painful silence the coffins were committed to their resting place. Rev. Mr. Williston then pronounced the benediction, "To the King, Immortal, Invisible, the All-wise God, be glory everlasting, amen." The occasion was one long remembered in both cities.

During many years these relics remained forgotten in their sepulchre. The grade of[21] Jackson Street was altered so as to take a part of the sacred ground. Jackson, when he gave the land, was not far-sighted enough to have secured the passage of an act to preserve its precincts intact, free from invasion by streets, and exempt from taxation. The land at one time was sold for taxes. It seemed as if the past had been forgotten. Then it was that Benjamin Romaine came forward and purchased the lot. In order to preserve it from desecration, he adopted it as his family burial plot. He resolved to be buried there himself, and placed within the vault a coffin designed for his mortal remains. He constructed the ante-chamber over the tomb. Upon the property he placed the following inscription:—

First—The portal to the tomb of 11,500 patriot prisoners of war who died in dungeons and pestilential prison ships in and about the City of New York during the war of our Revolution. The top is capped with two large urns in black, and a white globe in the centre.

Second—The interior of the tomb contains thirteen coffins assigned in the order as observed in the Declaration of Independence, and inserted thus—New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

[22] Third—Thirteen beautifully turned posts, painted white, and capped with a small urn in black, and between the posts the above-named States are fully lettered.

Fourth—In 1778, the Colonial Congress promulgated the Federal League compact, though it was not finally ratified until 1781, only two years before the peace of 1783.

Fifth—In 1789, our General National Convention, to form a more perfect unison, did ordain the present Constitution of the United States of America, to be one entire Sovereignty, and in strict adhesion to the equally necessary State rights. Such a republic must endure forever.

In 1842, a large number of citizens applied to the Legislature for permission to remove the remains to a more private place. Romaine vigorously and eloquently objected to the proposed change, and the matter was permitted to rest quietly until after his death in 1844. During the following year attention was again called to the forlorn and neglected condition of the sepulchre. Henry C. Murphy was then in Congress, representing Kings and Richmond counties. The abject condition of the vault was brought to the notice of Congress, and action taken. The military committee recommended an appropriation of $20,000 to[23] secure a permanent tomb and monument. The report was drawn by Henry C. Murphy, whose exertions in this behalf were untiring. The effort, however, was not successful.

Samuel Boughton, John T. Hildreth, John H. Baker, and other public-spirited men, holding diverse political views, started subscription papers, and published articles in the papers urging the importance of immediate action to accomplish the praiseworthy object.

In 1855, a meeting was held and a Martyrs' Monument Association formed. This association intended to have representatives from each State and Territory. The committee started with commendable energy. They early took the ground that Fort Greene was the proper site. Plans were proposed and subscriptions solicited. For a long time nothing more was done. The Common Council agreed to permit the use of Fort Greene. It was not until June, 1873, that the remains of the prison-ship martyrs were carried to the vault on the face of Fort Greene.2

The narrative here concluded has passed far[24] beyond the limits of the period to which this chapter is devoted. Turning to the post-Revolutionary period, we find the county towns resuming a normal course of life. The Dutchmen who gathered at the Brooklyn church ceased to talk of war. The Episcopalians, who worshiped in John Middagh's barn, at the corner of Henry and Poplar streets, turned from politics to denominational questions, and the "Independents" built a meeting-house on the Fulton Street ground afterwards taken by St. Anne's Buildings.

We learn from the "Corporation Manual" (1869) that the first step toward a fire department within the limits of the present city was taken in April, 1785, by the organization of a fire-company. At a meeting of the freeholders of the town, held at the house of Widow Moser, in Fulton Street, near the ferry, it was agreed that the company should be composed of seven members, who should be commissioned as firemen for one year. They selected the following persons as the members of the company: Henry Stanton, captain; Abraham Stoothoof, John Doughty, Jr., Thomas Havens, J. Van Cott, and Martin Woodward. They also voted to raise by tax the sum of £150 for the purchase of a fire-engine. Among the[25] regulations agreed upon for the government of the new company was a requirement that the members should meet on the first Saturday of each month, to play, clean, and work their engine, and that in case of their non-attendance, upon notification from their captain, a fine of eight shillings should be imposed upon them, and that upon the captain, in the event of his neglecting properly to notify the members, a fine of sixteen shillings should be imposed. The engine was in due time procured. It was constructed by Jacob Boome, of New York city, who had just then commenced business as the first engine-builder ever located in that city. Previous to his time, the fire-engines had generally been imported from England. The company adopted the name of "Washington Engine Company No. 1," and was, up to the time of dissolution of the Volunteer Department, still in active existence. Their engine-house was situated in a lane, now called Front Street, near its junction with Fulton Street.

The firemen continued to be chosen annually in town meeting, and the appointment was much sought after as conferring respectability of position in the community. On the 30th of April, 1787, the number of firemen[26] was increased to eleven, and it was resolved that each fireman should take out a license, for which he should pay a fee of four shillings, the sums thus accruing being appropriated to the ordinary expenses of the company.

On the 15th of March, 1788, came the first state legislation relative to the firemen of Brooklyn. In 1794 there were about fifty families residing within the limits of the fire district; the entire population, including some 100 slaves, numbering 350 souls. There were about seventy-five buildings in the district, mainly located between what is now called Henry Street and the ferry. Those devoted to business purposes were generally near the ferry, where a supply of water from the river could readily and easily be obtained. Although fires were of exceedingly rare occurrence, and trivial in their character, yet nine years of use, or rather disuse and decay and rust, had rendered the engine unserviceable. In view of this fact, on the first Tuesday of April, 1794, it was resolved in town meeting that a subscription should be authorized to raise the funds necessary for the purchase of a new engine. The sum of £188 19s. was speedily collected, and a new and more powerful engine was procured. In 1795 the Legislature[27] extended the limits of the fire district, and increased the volunteer force to thirty men. In town meeting it was resolved that each house should be provided with two fire-buckets, under a penalty of two shillings for every neglect so to provide after due notification. In 1796 a fire-bell was purchased by popular subscription, and set up in the storehouse of Jacob Remsen, at Fulton and Front streets, in sight of the ferry.

In the awarding of the ferry lease in 1789, it was ordered "that the boats, together with their masts and sails, be of such form and dimensions as the wardens of the port of New York should approve; that each boat be constantly worked and managed by two sober, discreet, and able-bodied experienced watermen; that each boat be always furnished with four good oars and two boat-hooks."3 A new ferry at Catherine Street was established in 1795.

Although the ferry was in active operation, traveling by land was by exceedingly primitive stages. As late as 1793, according to Furman, there was no post-office on any part of Long Island, and no mail carried on it. It was not until about the opening of the present[28] century that the first post-route was started. As late as 1835 "the regular mail stage left Brooklyn once a week, on Thursday, having arrived from Easthampton and Sag Harbor the afternoon of the previous day; and this was the only conveyance travelers could then have through this Island, unless they took a private carriage." The practice was to leave Brooklyn about nine in the morning, to dine at Hempstead, and then "jog on to Babylon, where they put up for the night."4

By the enterprise of the Flushing Bridge and Road Company, incorporated in 1802, the distance between Flushing and Brooklyn was shortened about four miles. Three years later the Wallabout and Brooklyn Toll Bridge Company laid out a road extending from the Cripplebush road to the easterly side of the Wallabout mill pond, over which a bridge connected with Sands Street.

Within the limits of the town5 the spirit of real estate enterprise appeared in various quarters, but perhaps the most ambitious undertaking was that of the holders of the Sands and Jackson tract, surveyed in 1787, and lying on the East River between the Wallabout and[29] the Brooklyn ferry. To the prospective village planned for this region was given the name of Olympia, after the habit of bestowing classical names which began to appear in post-Revolutionary days. In 1801 John Jackson sold forty acres of Wallabout lands to the United States for $40,000.

The columns of the "Long Island Weekly Intelligencer," published by Roberson & Little, booksellers and stationers, at the corner of Old Ferry and Front streets, give interesting glimpses of this period. In 1806 Henry Hewlet dealt in "general merchandise" near the Old Ferry; John Cole was coach-maker; Dr. Lowe's office was "at the Rev. Mr. Lowe's, corner of Red Hook Road." There was demand for five apprentices at Amos Cheney's shipyard. Benjamin Hilton sold china, glass, and earthenware, "at New York prices," in Old Ferry Street. Postmaster Bunce had fifty-three letters that had not been called for.

In a later issue of the "Intelligencer" the editor remarks that he has been "requested to suggest the propriety of each family placing lights in front of their houses, not having the advantage of lamps, as great inconvenience and loss of time arises from the neglect, particularly on dark nights."

[30] In 1808 the town appropriated $1500 for the erection of a new "poor house." The county court house of this period was at Flatbush, then the county seat. The old court house had been burned in 1758. The money required to build the new court house was raised by an assessment upon the inhabitants of the county. This building continued in use thirty-four years, when, by reason of its dilapidated condition, a new court house and jail were built in 1792. The court house cost $2944.71. The contractor was Thomas Fardon, and the plans for the building were furnished by Messrs. Stanton, Newton, and James Robertson. In referring to the court house, Furman says that "in 1800 the court house was let to James Simson for one year at £3 in money." In this agreement "the justices reserved for themselves the chamber in the said house called the court chamber, at the time of their publique sessions, courts of common pleas, and private meetings; as also the room called the prison, for the use of the sheriff if he had occasion for it." The building stood for forty years, when it was destroyed by fire.

Meanwhile the hamlet of Brooklyn took on many of the characteristics of a maturing[31] village. Joseph B. Pierson removed from New York to Brooklyn in 1809, and opened a circulating library on Main Street, two doors from Sands Street. In the "Long Island Star" of June, 1809, George Hamilton advertised a select school where "students were taught to make their own pens." Hamilton was succeeded by John Gibbons, who in September announced the opening of an academy for both sexes, where the various educational branches are "taught on unerring principles." Mrs. Gibbons was to "instruct little girls in Spelling, Reading, Sewing, and Marking." To the notice of an evening school for young men is appended: "N. B. Good pronunciation."

Two years later there was a private school opposite the post office; John Mabon taught the Brooklyn Select Academy; and at the inn of Benjamin Smith, on Christmas-eve, an exhibition was given by the pupils of Platt Kennedy. At this time the town had a floor-cloth factory, eight or ten looms were at work in Crichton's cotton goods manufactory, and over one hundred people worked in rope-walks. Abraham Remsen kept the one dry goods store at Fulton and Front streets.

Over the Black Horse tavern lived for a[32] time the "Rain-water Doctor," who was consulted by people coming great distances. This strange man dealt mostly in herbs and simples, but his specialty was rain water, which he praised as containing power to cure all manner of ills. He often signed himself, "Sylvan, Enemy of Human Diseases." Sylvan was evidently the first of a long list of "rain-water" quacks, against whom the regular practitioners of this and later periods had occasion to contend.6

[33] At the time when the census of Long Island (in 1811) estimated the population of Brooklyn at 4402, rapid progress had also been made by other towns in the county. Flatlands, which does not seem to have been particularly disturbed by the British occupation,—the church and schools continuing their regular sessions throughout the period,—built a new church in 1794, which was painted red and sanded, and had Lombardy poplars in front and rear. Church-going was a cold experience in those days, the new church, like its predecessors, being without means of heating, save the foot-stoves carried by women. It was not until 1825 that a large wood-stove was introduced. The schoolhouse stood within the original lines of the graveyard.

Gravesend, which had passed through an active early period, had in 1810 a population of 520. The hamlet was conservative in its habits of life and slow in numerical growth. To reach Coney Island from Gravesend at[34] this time, it was necessary to ford the creek at low tide. The Coney Island Bridge and Road Company was organized in 1823. To get their letters the Gravesend people were obliged to go to Flatbush.7 The old schoolhouse, after being in service for sixty years, was in 1788 succeeded by a larger building, which was in service for half a century. The Reformed Church records were still kept in the Dutch language. The church was a long low building with a gallery, under which, on the west side, were the negro quarters.

Flatbush had had a taste of the Revolutionary fighting, and suffered considerably during the British occupation.8

The mill finished in 1804, on John C. Vanderveer's farm, is described as the first mill on the island. The mills became a prominent feature of Flatbush scenery. Clustered near them were some of the quaintest examples of Dutch and colonial architecture that were to be found in this country. The examples surviving to-day give a distinctive charm to this village. In due time the stocks which had stood in front of the court house, the near-by[35] whipping-post,9 and the public brew-house all disappeared.

On the 2d of July, 1791, public notice was given of the plan for building a county court house and jail at Flatbush. The notice stated that the conditions would be made known by application to Charles Doughty, Brooklyn Ferry, and that propositions in writing would be received until July 15 by him and Johannes E. Lott, of Flatbush, and Rutgert Van Brunt of Gravesend.

Cruger, while mayor of New York city, had his residence within the village. Generals Howe, Clinton, and other leading Tories had their headquarters within its limits subsequent to the battle of Brooklyn.

Erasmus Hall, at Flatbush, was erected in 1786, its charter bearing the same date as that of the Easthampton Academy. The first public exhibition of Erasmus Hall was held September 27, 1787, "and the scene," says Stiles, "was graced by the presence of the Governor of the State, several members of the Assembly, and a large concourse of prominent gentlemen of the vicinity." The subject of public instruction continued to be agitated in the public prints and the pulpit, and the[36] attention of the Legislature was repeatedly called by the Governor's messages to the paramount need of having a regular school system throughout the State. Finally, in 1795, that body passed "an act for the encouragement of schools," and made an appropriation of $50,000 per annum for five years "for the purpose of encouraging and maintaining schools in the several cities and towns in this State in which children of the inhabitants residing in the State shall be instructed in the English language or be taught English grammar, arithmetic, mathematics, and such other branches of knowledge as are most useful and necessary to complete a good English education."

The Rev. Dr. John H. Livingston, who, with Senator John Vanderbilt, brought about, the establishment of the academy, was succeeded as principal by Dr. Wilson, who also held a professorship at Columbia College. The records of the academy reveal an interesting list of names, and the institution has held an important relation to the educational interests of Flatbush.

New Utrecht, where the first resistance to the British forces had been offered, and whose church had been used as a hospital and also as a riding-school by the British officers, was[37] quick to assume its wonted ways after the departure of the troops when peace with England had been declared. During the period between 1787 and 1818 the Rev. Petrus Lowe was the pastor.10

The progress of Bushwick after the Revolution was noteworthy. The old Dutch church had been built early in the last century. The dominies from Brooklyn and Flatbush had previously ministered to the people when occasion called. The old octagonal church received a new roof in 1790, a front gallery five years later, and so it remained until 1840. Stiles11 mentions Messrs. Freeman and Antonides as the earliest pastors, and Peter Lowe as serving here until 1808. A regiment of Hessians had their winter quarters here in 1776, barracks being put up on the land of Abraham Luqueer, and free use being made of wood from the Wallabout swamp. The case of Hendrick Suydam[38] was typical. Suydam had to give quarters in his house,12 and the filthy habits of these unsavory mercenaries were shockingly characteristic of this unhappy period. Stiles mentions, among the "patriots of Bushwick," John Provost, John A. Meserole, John I. Meserole, Jacob Van Cott, David Miller, William Conselyea, Nicholas Wyckoff, and Alexander Whaley, but no such list gives due honor to the service of all the Bushwick patriots.

After the Revolution Bushwick had "three distinct settlements or centres of population." These were "Het Dorp," the original town plot at the junction of North Second Street and Bushwick Avenue; "Het Kivis Padt," on the cross-roads at the junction of Bushwick Avenue and the Flushing Road; and "Het Strand," along the East River shore. The first mentioned was the centre of village activity, with the old church for chief landmark.

Of the town house with its tall liberty pole, Field13 writes: "Long after the Revolution the old town house continued to be the high seat of justice, and to resound with the republican roar of vociferous electors on town meeting days. The first Tuesday in April and the[39] fourth of July, in each succeeding year, found Het Dorp suddenly metamorphosed from a sleepy Dutch hamlet into a brawling, swaggering country town, with very debauched habits. Our Dutch youth had a most enthusiastic tendency, and ready facility in adopting the convivial customs and uproarious festivity of the loud-voiced and arrogant Anglo-American youngers.14 One day the close-fisted electors of Bushwick devised a plan for easing the public burdens by making the town house pay part of the annual taxes, and accordingly it was rented to a Dutch publican, who afforded shelter to the justices and constables, and by his potent liquors contributed to furnish them with employment.

"In this mild partnership, so quietly aiding to fill each others' pockets, our old friend Chas. Zimmerman had a share, until he was ousted, because he was a better customer than landlord. The services of the church were conducted in the Dutch language until about the year 1830. The clergyman had the care of five churches, each of which received his spiritual services in turn. The homely but pious[40] men who performed these duties were sometimes learned and dignified gentlemen, always a little aristocratic in their ways, for the dominie of a Dutch colony was an important functionary, whom the Governor-General himself could not snub with impunity. One of their self-indulgent customs would strike a modern community with horror. On arriving at the church, just before the time for Sunday service, the good dominie was wont to refresh himself from the fatigue of his long ride with a glass of some of the potent liquors of the time at the bar of the town house.

"At last the electors of Bushwick got tired of keeping a hotel, and unanimously quit-claimed their title to the church. Some time after the venerable structure [the town house] was sold to an infidel Yankee, at whose bar the good dominie could no longer feel free to take an inspiriting cup before entering the pulpit, and the glory of the town house of Bushwick departed."

The graveyard of the original Dutch settlement lay in sight of the church, and the last remains within its borders were not disturbed until 1879, when the bones were removed in boxes and placed under the Bushwick Church. Not far distant were the De Voe, De Bevoise,[41] and Wyckoff houses, the last named built by Theodorus Polhemus, of Flatbush.15

On the river front was the famous tavern of "Charlum" Titus. Toward Bushwick Creek was the Wartman homestead. On Division Avenue was the Boerum house; the Remsen house was on Clymer Street. Peter Miller, Frederic De Voe, and William Van Cott were prominent residents.

On Newtown Creek stood Luqueer's mill, built in 1664, by Abraham Jansen, and the second to be erected within the limits of the present city of Brooklyn. Freekes' mill at Gowanus was the oldest, a pond being formed by damming the head of Gowanus Kill. Remsen's mill was at the Wallabout. It was built in 1710, and it was from the vantage ground of his residence here that Rem Remsen witnessed so many of the prison-ship horrors. Remsen performed many humane acts toward the unfortunates of the floating dungeons.

The boundary dispute between Newtown and Bushwick—a wrangle beginning in Stuyvesant's day and lasting until 1769—forms one of the most picturesque features of political life[42] in the history of the two towns. "Arbitration Rock," as a famous landmark in the survey was called, having been destroyed, a new rock was placed in position by Nicholas Wyckoff, with the permission of the Commissioners appointed to resurvey the line in 1880, and still remains.

We have seen that one section of the town of Bushwick, or rather an outlying group of farms and houses, lay on the river front. Traffic to and from New York naturally passed through this river section of the settlement. At the beginning of the century Richard M. Woodhull, a New York merchant, established a horse-ferry from Corlaer's Hook, close to the foot of the present Grand Street, New York, to the foot of the Long Island road, now bearing the name of North Second Street.

The New York landing-place of the ferry was then considerably above the settled part of the town. In New York at this period the tendency of development still was along the eastern side of the island. "The seat of the foreign trade," says Mr. Janvier, "was the East River front; of the wholesale domestic trade, in Pearl and Broad streets, and about Hanover Square; of the retail trade, in William, between[43] Fulton and Wall. Nassau Street and upper Pearl Street were places of fashionable residence; as were also lower Broadway and the Battery. Upper Broadway, paved as far as Warren Street, no longer was looked upon as remote and inaccessible; and people with exceptionally long heads were beginning, even, to talk of it as a street with a future; being thereto moved, no doubt, by consideration of its magnificent appearance as the great central thoroughfare of the city upon Mangin's prophetic map."

Notwithstanding the development of New York on the East River side, there were two miles of travel between Woodhull's ferry and the business part of the city. Woodhull bought and "boomed" property in the vicinity of the ferry road on the Long Island side, then known as Bushwick Street, and to the settlement in this region he gave the name of Williamsburgh, "in compliment to his friend, Colonel Williams, U. S. engineer, by whom it was surveyed." A ferry-house, a tavern, a hay-press, appeared on the scene.

"An auction was held," writes John M. Stearns,16 "at which a few building lots were[44] disposed of. But the amount realized came far short of restoring to Woodhull the money he had thus prematurely invested. His project was fully a quarter of a century too soon. It required half a million of people in the city of New York, before settlers could be induced to move across the East River away from the attractions of a commercial city. Woodhull found that notes matured long before he could realize from the property; and barely six years had passed before he was a bankrupt, and the site of his new city became subject to sale by the sheriff. By divers shifts the calamity was deferred until September 11, 1811, when the right, title, and interest of Richard M. Woodhull in the original purchase, and in five acres of the Francis J. Titus estate, purchased by him in 1805, near Fifth Street, was sold by the sheriff in favor of one Roosevelt. James H. Maxwell, the son-in-law of Woodhull, became the purchaser of Williamsburgh; but not having the means to continue his title thereto, it again passed under the sheriff's hammer, although a sufficient number of lots had by this time been sold to prevent its re-appropriation to farm and garden purposes."

Then came Thomas Morrell, of Newtown, who bought the Titus homestead farm of[45] twenty-eight acres, prepared a map, and set down Grand Street as a dividing line. In 1812, Morrell obtained from New York city a grant for a ferry from Grand Street, Bushwick, to Grand Street, New York.

This new town site, extending between North Second Street as far over as the present South First Street, received the name of Yorkton. The rivalry between the Morrell and the Woodhull ferry became very heated. "While Morrell succeeded as to the ferry," writes Mr. Stearns, "Woodhull managed to preserve the name Williamsburgh; which applied at first to the thirteen acres originally purchased, and had extended itself to adjoining lands so as to embrace about thirty acres, as seen in Poppleton's map in 1814, and another in 1815, of property of J. Homer Maxwell. But the first ferry had landed at Williamsburgh, and the turnpike went through Williamsburgh out into the island. Hence, both the country people and the people coming from the city, when coming to the ferry, spoke of coming to Williamsburgh. Thus Yorkton was soon unknown save on Loss's map, and in the transactions of certain land-jobbers. Similarly the designations of old farm locations, being obsolete to the idea of a city or a village, grew into[46] disuse; and the whole territory between Wallabout Bay and Bushwick Creek became known as Williamsburgh."

At this time the owners of shore property refused to have a road opened through their property or along the shore. The two ferries were not connected by shore road, nor with the Wallabout region, and neither ferry prospered during the lifetime of either Woodhull or Morrell. General Johnson, in going from his Wallabout farm to Williamsburgh, "had to open and shut no less than seventeen barred gates within a distance of a mile and a half along the shore." The owners opposed Johnson's movement for a road, but with the aid of the Legislature the road was opened, business at the ferries immediately improved, and Williamsburgh began to grow. A Methodist congregation built a church in 1808; a hotel appeared at about the same time, and in 1814 there were 759 persons in the town. Noah Waterbury, by the building of a distillery at the foot of North Second Street and other enterprises, earned the title of "The Father of Williamsburgh."

Brooklyn during the "Critical Period" in American History. The Embargo and the War of 1812. Military Preparations. Fortifications. Fort Greene and Cobble Hill. Peace. Robert Fulton. The "Nassau's" First Trip. Progress of Fulton Ferry. The Village Incorporated. First Trustees. The Sunday-School Union. Long Island Bank. Board of Health. The Sale of Liquor. Care of the Poor. Real Estate. Village Expenses. Guy's Picture of Brooklyn in 1820. The Village of that Period. Characters of the Period. Old Families and Estates. The County Courts removed to Brooklyn. Apprentices' Library. Prisoners at the Almshouse. Growth of the Village. The Brooklyn "Evening Star." Movement for Incorporation as a City. Opposition of New York. Passage of the Incorporation Act.

As the hamlet of Brooklyn waxed in size and took on the characteristics of an organized community, with a formulated political plan, a fire department, a commercial nucleus that justified a petition17 to the Legislature for the establishment of a local bank, and a population of nearly 5000 people, it began to feel[48] more directly and inevitably than it ever had theretofore the effect of political and commercial movements in the State, and in the nation as a whole.

The early years of the present century, during which Napoleon was terrorizing Europe, were years of formative uncertainties to the young United States. John Fiske has called this time "the critical period" of American history. Speaking of the extraordinary commercial manifestations of the post-Revolutionary period, Mr. Fiske says: "Meanwhile, the different States, with their different tariff and tonnage acts, began to make commercial war upon one another. No sooner had the other three New England States virtually closed their ports to British shipping than Connecticut threw hers wide open, an act which she followed up by laying duties upon imports from Massachusetts. Pennsylvania discriminated against Delaware, and New Jersey, pillaged at once by both her greater neighbors, was compared to a cask tapped at both ends.

"The conduct of New York became especially selfish and blameworthy. That rapid growth, which was so soon to carry the city and the State to a position of primacy in the Union, had already begun. After the departure of[49] the British the revival of business went on with leaps and bounds. The feeling of local patriotism waxed strong, and in no one was it more completely manifested than in George Clinton, the Revolutionary general, whom the people elected Governor for nine successive terms. From a humble origin, by dint of shrewdness and untiring push, Clinton had come to be for the moment the most powerful man in the State of New York. He had come to look upon the State almost as if it were his own private manor, and his life was devoted to furthering its interests as he understood them. It was his first article of faith that New York must be the greatest State in the Union. But his conceptions of statesmanship were extremely narrow. In his mind, the welfare of New York meant the pulling down and thrusting aside of all her neighbors and rivals. He was the vigorous and steadfast advocate of every illiberal and exclusive measure, and the most uncompromising enemy to a closer union of the States. His great popular strength and the commercial importance of the community in which he held sway made him at this time the most dangerous man in America."

The relations of the States became more[50] amicable in the early years of the century, the rival commonwealths being drawn together by a general obligation of self-defense as against England. In 1808 had come Jefferson's Embargo Act, of whose influence in New York John Lambert writes: "Everything wore a dismal aspect at New York. The embargo had now continued upwards of three months, and the salutary check which Congress imagined it would have upon the conduct of the belligerent powers was extremely doubtful, while the ruination of the commerce of the United States appeared certain if such destructive measures were persisted in. Already had 120 failures taken place among the merchants and traders, to the amount of more than 5,000,000 dollars; and there were above 500 vessels in the harbor which were lying up useless, and rotting for want of employment. Thousands of sailors were either destitute of bread, wandering about the country, or had entered the British service. The merchants had shut up their counting-houses and discharged their clerks; and the farmers refrained from cultivating their land; for if they brought their produce to market they could not sell it at all, or were obliged to dispose of it for only a fourth of its value."

[51] Elsewhere in his journal, Lambert writes: "The amount of tonnage belonging to the port of New York in 1806 was 183,671 tons, and the number of vessels in the harbor on the 25th of December, 1807, when the embargo took place, was 537. The moneys collected in New York for the national treasury, on the imports and tonnage, have for several years amounted to one fourth of the public revenue. In 1806 the sum collected was 6,500,000 dollars, which, after deducting the drawbacks, left a net revenue of 4,500,000 dollars, which was paid into the treasury of the United States as the proceeds of one year. In the year 1808 the whole of this immense sum had vanished!"

In June, 1812, came the declaration of war with Great Britain. The news occasioned considerable excitement in Brooklyn, whose middle-aged men retained a lively recollection of the British occupation. In the "Star" of July 8 appeared this announcement: "A new company of Horse or Flying Artillery is lately raised in this vicinity, under the command of Captain John Wilson. This company promises, under the able management of Captain Wilson, to equal, if not excel, any company in the State. The Artillerists of Captain Barbarin[52] are fast progressing in a system of discipline and improvement, which can alone in the hour of trial render courage effectual. We understand this company have volunteered their services to Government, and are accepted. The Riflemen of Captain Stryker and the Fusileers of Captain Herbert are respectable in number and discipline. The county of Kings is in no respect behind her neighbors in military patriotism."

The Fusileers wore green "coatees" and Roman leather caps. The green frocks of the Rifles were trimmed with yellow fringe, a feature of the costume which is reputed to have originated the appellation "Katydids." In August the Artillery practiced at a target, and John S. King won a medal.

Two years elapsed before Brooklyn was actually threatened with war. In 1814 the fear that the British fleet might, as in the Revolutionary descent, land at Gravesend, was naturally entertained. The committee of defense decided to build two fortified camps on Brooklyn Heights and on the heights of Harlem. Volunteers for labor on local and suburban defenses were called for, and there was a patriotic response. A company of students from Columbia Academy, Bergen, N. J.,[53] performed work on the Brooklyn Heights fortifications.18 The Long Island defenses extended from the Wallabout to Fort Greene, to Bergen's Heights (on Jacob Bergen's property), and to Fort Lawrence.

On the 9th of August, 1814, General Mapes, of New York, with a body of volunteers, broke ground for the intrenchments at Fort Greene. The work was carried on day by day by a different corps of volunteers. One day the labor would be performed by the tanners and curriers and the veteran corps of artillery; on another day, in happy unison, would be seen working, side by side, a brigade of infantry, a military association of young men, the Hamilton Society, and students of medicine; on another, a delegation from Flatbush would be seen engaged earnestly on the work; on another, the people of Flatlands would be armed with pick and shovel; then Gravesend dug in the trenches. Irishmen were not to be outdone; they proved their patriotism and love of liberty by volunteering, 1200 strong, to labor in the cause. Then the burghers from New Utrecht gave a helping hand. The free colored people gladly gave their aid. Jamaica came, headed by Dominie Schoonmaker, and[54] with them came the principal of the academy, with his pupils. Workmen came from New York, Newark, Paulus Hook, and Morris County, N. J. A company came from Hanover Township, headed by their pastor, Rev. Dr. Phelps, and labored for a day upon these fortifications. So, too, the members of the Baptist Church in New York came, with their pastor, Rev. Dr. Archibald Macloy, and did a day's work. Rev. Dr. Macloy was the father of Congressman Macloy, who ably represented the seventh ward of New York and a part of Kings County before the late civil war.

The erection of the defenses of Brooklyn was thus not a local affair. It was one in which the neighboring cities, towns, and States took part. The people were enthusiastic. The Grand Lodge of Masons enlisted in the service, and the watchword of the day was: "The Master expects every Mason to do his duty." Old Fortitude Lodge, which still exists, rendered a day's service. A company of ladies came from New York, forming a procession, with music, marched to Fort Greene, and used the shovel and the spade for several hours. The people had one mind and were actuated by one purpose. The work advanced rapidly, for, as in the days of Nehemiah,[55] the "people had a mind to work," and their efforts were crowned with success. These were the times when the people willingly gave their money for the good of the country, without expecting to receive it again with compound interest.

Early in September the works were completed. The Twenty-second Brigade of Infantry, composed of 1750 men, was stationed within the lines. Heavy artillery was mounted. Brigadier General Jeremiah Johnson was in command. He was a natural soldier, and possessed every element of character necessary to lead a brigade. Stern and unflinching in the performance of duty, he yet had a warm and generous heart, which led him to take an active interest in the welfare of the men in his command. The soldiers loved him, and rendered willing obedience to his orders. Being a resident of Brooklyn, he knew or was known by most of his men personally.

At the fort on Cobble Hill worked military companies under command of Captains Stryker, Cowenhoven, and Herbert, the "exempts" of Bedford and the Wallabout, Fire Company No. 2 of Brooklyn, and a company of Bushwick people headed by Pastor Bassett. "Next to the duties which we owe to Heaven,"[56] said the Bushwick people at their meeting, "those which belong to our country demand our chief attention."

The volunteers worked with the utmost zeal, laboring by moonlight when sunset still left work to do. The Sixty-fourth Regiment, of Kings County, was commanded by Francis Titus, with Albert C. Van Brunt as second major, and Daniel Barre as adjutant. New Utrecht's company was headed by Captain William Dewyre; Brooklyn's company was headed by Captain Joseph Dean; the Wallabout and Bushwick company, by Captain Francis Stillman; the Gowanus company, by Captain Peter Cowenhoven, and later by Captain John T. Bergen; the Gravesend and Flatbush companies, by Captain Jeremiah Lott.

Brooklyn was, indeed, ready, but fortunately the crisis for which it prepared did not appear. On the evening of February 11, 1815, came the news of peace with Great Britain. On the evening of the 21st Brooklyn was illuminated in a spirit of rejoicing, and the band of the Forty-first Regiment, then stationed in the village, voiced the delight of the people.

Meanwhile, various important advances had been made by Brooklyn and her neighbors. In 1812, Robert Fulton having made a successful[57] experiment with his first steamboat, the Clermont, a steam ferry was opened between New York City and Paulus Hook, Jersey City. In that year Fulton and his "backer," Robert R. Livingston, offered to the corporation of the city of New York a proposition to establish a steam ferry from Fly Market Slip to Brooklyn.19 The proposition was accepted, and it was decided to run the boats from Burling Slip. "As, however, the slip was not then filled in, and the cost of filling was estimated at $30,000, it was finally concluded to establish the ferry at Beekman Slip (present Fulton Street, New York), which was accordingly purchased for that purpose by the corporation from Mr. Peter Schermerhorn. Beekman Slip at that time extended only to Pearl Street. Fair Street, which then ran from Broadway to Cliff Street, was extended through the block between Cliff and Pearl streets to join Beekman Slip. To this newly extended Fair Street, from the East River to Broadway, and to Partition Street, which then extended from Broadway to the Hudson River, was given the name of Fulton Street, in honor of the distinguished inventor, in consequence of the[58] establishing of whose steam ferry this street was about to become a great highroad of travel and traffic. The ferry from Fly Market Slip was discontinued.

"The lease of the ferry was granted to Robert Fulton and William Cutting (his brother-in-law), for twenty-five years,—from the 1st of May, 1814, to May, 1839,—at an annual rental of $4000 for the first eighteen years, and $4500 for the last seven years. The lessees were to put on the ferry one steamboat similar to the Paulus Hook ferry-boat; to run once an hour from each side of the ferry, from half an hour before sunrise to half an hour after sunset; to furnish in addition such barges, etc., as were required by previous acts of the Legislature; and on or before the 1st of May, 1819, they were to provide another steamboat in all respects equal to the first, and when that was done a boat should start from each side of the river every half hour. As a compensation to the lessees for the increase of expense which would be incurred in conducting the ferry upon such an enlarged scale, the corporation covenanted to apply to the Legislature for a modification and increase in the rates of ferriage; and in case the bill passed before May 1, 1819, Messrs. Fulton[59] and Cutting agreed to put on their second boat at the earliest possible date thereafter. In case of its failing to pass, they were to be permitted to receive four cents for each and every passenger who might choose to cross the river in the steamboat, but the fare in barges was to remain as it had been, viz., two cents."20

The proposed bill successfully passed the Legislature, and Fulton and Cutting formed a stock company, called the New York and Brooklyn Steamboat Ferry Association, with a capital of $68,000. The first steam ferry-boat, called the Nassau, began running on Sunday, May 10, 1814. "This noble boat," said the Long Island "Star," "surpassed the expectations of the public in the rapidity of her movements. Her trips varied from five to twelve minutes, according to tide and weather.... Carriages and wagons, however crowded, pass on and off the boat with the same facility as in passing a bridge. There is a spacious room below the deck where the passengers may be secure from the weather, etc." On one of the first day's trips an engineer was fatally hurt.

The Nassau made forty trips on the following[60] Sunday, and became a useful and popular institution. She was used after business hours for pleasure excursions on the river. The plan of construction was that of a double boat, with the wheel in the centre, the engine-house on deck and the passenger cabin in one of the hulls. Peter Coffee, the first pilot, died in 1876, aged ninety-nine years. One end of the deckhouse of the Nassau was occupied by a pensioner of Fulton's, who sold candies and cakes.

While the Nassau was in operation the horse ferry-boats were also used on the Fulton Ferry. These horse ferry-boats were peculiar craft. The first horse-boats were single-enders, and were compelled to turn around in crossing the river. Subsequently double-enders were used. All these boats had two hulls, about twenty feet apart and covered over by a single deck. Between these hulls were placed the paddle-wheels, working upon the shafting propelled by horses.

"By an invention of Mr. John G. Murphy, father of ex-Senator Henry C. Murphy, the managers of these boats were enabled to reverse their machinery without changing the position of the horses. The steamboat was very popular with the public. Owing to its[61] success there was soon a very marked desire in both cities for the addition of the second steamboat, in accordance with the terms of the contract made by the lessees with the city of New York. Objection was made by the lessees on the ground of additional expense, and boats run by horse power were substituted. In 1815 Robert Fulton died. Mr. Cutting, who had lived in New York, removed to Brooklyn, and died at his residence on the Heights in 1821. The winter of 1821–22 was one of the most severe in the history of the country. The ferries were obstructed by enormous quantities of floating ice. Great cakes became jammed between the double hulls, and travel was practically suspended. Brooklyn had grown rapidly, and an uproar arose in which the ferry management was roundly assailed. Who can tell but it was here that the original idea of the East River Bridge was first born? In 1827 a steamboat similar to the Nassau, and called the William Cutting, was put on the ferry, but even this did not satisfy the public, who were eagerly seeking more extended accommodations. In 1833 Messrs. David Leavitt and Silas Butler secured a controlling interest in the stock of the company, and sought to meet the anticipations[62] of the people by adding two new steamboats, the Relief and the Olive Branch. Unlike their predecessors, these boats had single hulls and side wheels. Subsequently agitation in the southern part of Brooklyn led to the establishment of the South Ferry."

In 1817, the Loisian Academy, which had been started four years before, received a salaried teacher, and was removed to the small frame house on Concord and Adams streets, where Public School No. 1 was afterward built.

Brooklyn began soon after the Revolution to think seriously of the matter of incorporation as a village. On January 8, 1816, a public meeting was held at the public house of Lawrence Brown, "to take into consideration the proposed application for an incorporation of Brooklyn. A committee, consisting of Thomas Everit, Alden Spooner, Joshua Sands, the Reverend John Ireland, and John Doughty, met the following day at the house of H. B. Pierrepont. On April 12th the act incorporating the village passed the Legislature."

Built in 1827