Project Gutenberg's Travels in South Kensington, by Moncure Daniel Conway

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Travels in South Kensington

with Notes on Decorative Art and Architecture in England

Author: Moncure Daniel Conway

Release Date: April 22, 2013 [EBook #42571]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRAVELS IN SOUTH KENSINGTON ***

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

WITH

Notes on Decorative Art and Architecture

in England

BY

MONCURE DANIEL CONWAY

AUTHOR OF

“THE SACRED ANTHOLOGY,” “THE WANDERING JEW,” “THOMAS CARLYLE,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

LONDON

TRÜBNER & CO., LUDGATE HILL

1882

[All rights reserved]

Ballantyne Press

BALLANTYNE, HANSON AND CO.

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

THE SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM

DECORATIVE ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN ENGLAND

BEDFORD PARK

| PAGE | |

| THE SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM | 19 |

| DECORATIVE ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN ENGLAND | 115 |

| BEDFORD PARK | 215 |

| [Some of the illustrations have been moved out of paragraphs for easier reading of the text. (n of t)] | |

| PAGE |

The Statue of His Royal Highness the Prince Consort | Frontispiece |

South Kensington Museum | 21 |

Sir Henry Cole, K.C.B. | 36 |

South Kensington Museum—Ground Plan | 39 |

Diagram showing Glitter Points in a Picture-gallery | 40 |

Sir Philip Cunliffe Owen, Director of South Kensington Museum | 42 |

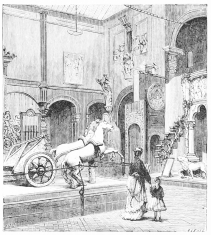

North Court, North-west Corner, Showing Casts of the Biga (or Two-horse Chariot), from the Original in Marble at the Vatican, and of the Pulpit by Giovani Pisano, formerly in the Cathedral at Pisa | 44 |

South Court, Showing the Prince Consort’s Gallery | 45 |

Chinese Potters at Work—Window in the Ceramic Gallery | 47 |

Italian Majolica (Urbino). Sixteenth Century | 51 |

Lamp from an Arabian Mosque. Fourteenth Century | 53 |

Palissy, the Potter—Window in the Ceramic Gallery | 54 |

Sèvres Porcelain Vase. Modern | 55 |

Henri Deux Candlestick | 56 |

Henri Deux Salt-cellar | 58 |

Michael Angelo’s Eros | 62 |

Marble Cantoria. By Baccio D’Agnolo | 65 |

Tabernacle. Andrea Ferrucci | 66 |

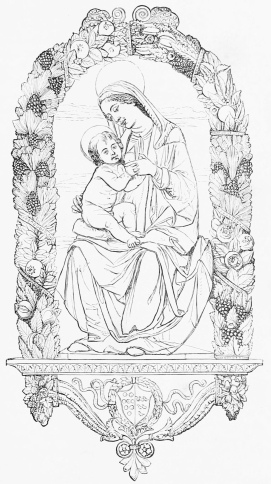

Altar-piece—the Virgin with the Infant Saviour.—Enamelled Terra-cotta, or Della Robbia, in High Relief. By Andrea Della Robbia | 67 |

Hercules, the Duke of Ferrara | 70 |

Ashantee Relics | 72 |

The Cellini Sardonyx Ewer, Mounted in Enamelled Gold, and Set with Gems—Italian. Sixteenth Century | 73 |

Châsse, or Reliquary—Limoges Enamelled. Thirteenth Century | 75 |

Pastoral Staves—Ivory and Enamel. Fourteenth Century | 82 |

Elkington’s Mark | 85 |

Franchi and Son’s Mark | 85 |

Modern Persian Ewer (Copper-coated, with White Metal) | 94 |

Old Persian Earthenware (Water-bottle) | 95 |

Persian Kaliān | 96 |

Ancient Persian Incense-burner (Pierced and Chased Brass) | 97 |

Modern Persian Incense-burner (Brass) | 98 |

Andrea Gritti, Doge of Venice—Italian. Ascribed to Vittore Camelo. Sixteenth Century | 99 |

Tazza—Algerian Onyx and Enamel. Modern French | 100 |

Salt-cellar—Silver Gilt; Italian. Fifteenth Century | 100 |

Ivory Tankard—Augsburg. Seventeenth Century | 101 |

Finest Raised Venetian Point Lace—Floral Design. Italian. Seventeenth Century | 104 |

Nettle in its Natural State | 109 |

Nettle in Geometrical Proportions | 109 |

Plan of Top of Henri Deux Salt-cellar | 111 |

Assize Court, Manchester | 122 |

| 124 | |

Kidderminster Carpet—Fern Design | 127 |

Minton Tiles for Mantel | 129 |

Albert Memorial, Hyde Park | 131 |

Albert Memorial. Europe | 133 |

Albert Memorial—East Front. Painters | 134 |

Albert Memorial—Continuation of East Front. Painters | 136 |

Albert Memorial—South Front. Poets and Musicians | 138 |

Albert Memorial—Continuation of South Front. Musicians | 140 |

Spandrel Picture | 147 |

Owen Jones | 153 |

Ebony Serving-table, Mr. Lehmann’s House | 162 |

Top of Serving-table, Mr. Lehmann’s House | 164 |

Pot Designed by Miss Lévin | 167 |

William Morris | 185 |

Moulding over Dado | 186 |

Chippendale Mahogany Moulding, Belmont House | 187 |

Drawing-room of Bellevue House | 188 |

Library in Bellevue House | 191 |

Drawing-room in Townsend House | 194 |

A Grate of One Hundred Years Ago | 198 |

Grate made for Baron Rothschild | 199 |

Boyd’s Grate | 200 |

L. Alma Tadema.—[From a Bust by J. Dalou] | 207 |

Candelabra, Townsend House | 209 |

View from a Balcony | 217 |

Dining-room in Tower House | 222 |

Queen Anne’s Gardens | 224 |

Co-operative Stores and Tabard Inn | 225 |

Tower House and Lawn-tennis Grounds | 226 |

Reading and Billiard Room, Club-house | 227 |

A Fancy-dress party at the Club | 229 |

An Artist’s Studio | 233 |

HOMELY and Comely were sisters. Their parents were in humble circumstances, and depended mainly on the care and economy of these two daughters—their entire family. They were persons of some social position, and it had constituted a problem how they might preserve some relation to the community and at the same time maintain comfort at home: Youth required the former, Age needed the latter. It was settled in a way which this historian cannot commend: the arrangement was that one of the girls should attend to the external, the other to the internal affairs of the family. So soon as this was resolved, there was no difficulty in determining which of the girls should go out and which stay at home. There was about Comely a certain ease and address, as well as personal attractiveness, which seemed to make society her natural sphere; while the shyness and plainness of Homely made the task of remaining at home congenial. Homely was content with homespun clothes in order that Comely might wear silk. Whenever there was a ball or a festival, Comely was sure to come, and Homely stayed at home.

Gradually, however, this distribution of parts appeared not to have the happiest results. Comely grew so fond of the gay world that her home became distasteful; she demanded, too, more and more of the family resources for her fashionable attire, and the concession deprived the house of everything but the barest utensils. On the other hand, Homely had stayed withindoors so much that she became slovenly, and, as she had to wear her homespun till it was threadbare, in order that her sister might keep up with the fashions, she became unlovely to look upon. Comely came at length to despise her sister. Homely became a peevish drudge. The family by degrees became unhappy, without being very clear as to the cause of their troubles.

One night Comely came home from a ball in unusual agitation. Her sister was aroused to hear the confidence that a lover of rank, handsome and charming, had discovered his interest in Comely. Any differences the sisters may have had were quite forgotten in the renewal of their natural sympathy caused by this incident.

The next morning a messenger arrived to announce that his master, Lord Deeplooke, was on his way to visit Comely and the family in their own home, and would arrive in an hour. Here was a sensation! The two sisters set themselves to work—even Comely using her hands for once—to make the chief room of the house neat. But Comely looked on the blank walls with dismay, and said, “Surely there used to be some pictures.” “Yes,” replied Homely, “but you are wearing the last of them now.” Comely blushed—and the blush was becoming—at this; but the sisters gathered some beautiful flowers and decorated the room as well as they could. When this was attended to Comely was about to repair to her room to decorate herself, and called her sister to do the same; but Homely declared she already had on her very best gown. Comely was shocked at this, and entreated her sister to conceal herself during the nobleman’s visit. This Homely was quite willing to do.

When Lord Deeplooke arrived, Comely met him in the finest array she had next to the ball-dress. She introduced him to her venerable parents; but a shade of anxiety passed over her face when she observed his lordship presently looking around as if he expected some one else. She then remembered that the messenger had announced that he was coming to visit not her alone but the family, and that on the evening before, at the ball, she had casually mentioned her sister. With a quick wit Comely anticipated the inquiry she knew would be made and left the room, remarking, as she did so, “I pray your lordship to excuse me while I seek my sister.” Another moment and the two girls were hurriedly investing Homely in Comely’s second-best dress.

It was a novel experience for Homely to be dressed in a pretty gown; it was equally novel for her to be introduced to a gentleman, much less a lord; and the two novelties together had an almost transforming effect upon her. Home-work and early hours had kept her in perfect health; her manners had no chance to be other than simple; and as no experiences of fashionable life had made her blasé, her face was suffused with an exquisite color, and her eye bright with delight, when she entered the room and was introduced to his lordship.

The reader must not be kept in suspense for another instant. It was not Comely but Homely that Lord Deeplooke ultimately married. Homely having discovered the secret that lay in a becoming dress, chiefly from its effect on the feeling of the wearer, stoutly refused to be slovenly any more; and all her serviceable virtues, thus set in a fit frame, were found to have touched her countenance into unconventional beauty. On the other hand, Comely, though at first jealous and angry, gradually appreciated the lesson she had been taught. She did not, indeed, forget the magical effect wrought on her sister by a beautiful dress; but she pondered deeply the qualities fostered at home which she had supposed incongruous with such raiment, but now saw particularly harmonious with it; and thenceforth, even before Homely was married, Comely devoted herself to household work. Need I say that in this Comely was far more successful than her sister had been? All the beauty she had seen in the gay world, an occasional visit to which she still enjoyed, now became available. Pictures reappeared on the walls, which her sister had supposed were just as useful without them. Touches of color, a ribbon on the curtain which had hitherto been tied with a string, a hundred refinements which required only a cultured taste, gradually transformed the house, just as Comely’s dress had transformed Homely. For these improvements Comely had been glad to part with her mere finery, though she never forgot that a slovenly mistress makes a slatternly home.

Comely subsequently married an artist, who, beginning life as a sign-painter, was made a knight for the best example of domestic decoration exhibited at the Great Exposition of 18—, a model which, he frankly confessed, was suggested by the house in which he found his bride.

There are, indeed, few words in our language of more peculiar, or even pathetic, import than the word “homely.” It has gradually come to bear the significance of coarseness or even ugliness, as if these were quite appropriate to the home. It is, indeed, fortunate that the home can supply affection for things and persons not very presentable; but it is none the less true that the word has gradually come to represent the impression that beauty is for outside show, and that anything will do for home purposes.

Decoration (decus) means the bestowal of honor. Beauty followed honor. Because man honored his deity, grand temples and cathedrals arose and altars blazed with gems; and because he honored the prince and the noble, palaces were decked with splendor. All this time the home remained homely, for religion denied its sanctity and aristocracy despised it as the dwelling-place of a serf. The wealthy called their residences palaces, châteaux, castles, villas, seats, anything but “homes.” The “Home” came to mean some common asylum of the poor. But at last two mighty forces invaded Europe—Democracy and Heresy. Sternly they forbade man longer to spend his strength and his honor on allied Tyranny and Superstition. Then the Arts declined, because the convictions which had inspired them were shaken. Several of the grandest cathedrals were struck by a sort of paralysis and could never get finished, and palaces had to continue their grandeur on terra-cotta and tinsel.

And now the cunning workman, having struck work upon shrines and thrones, began to think of his own mind, so long left vacant that temples might be adorned, of his wife and child, so long stinted that palaces might be luxurious. The first expression of this new reflection was not outward: it was in the decoration of men’s minds with furniture of another kind—with science, poetry, and literature. Enamored of these deeper pleasures, man almost despised and hated the outward arts which symbolized his long thraldom. And perhaps it was necessary that the ancient splendors which invested a departed era should fade, and that man should retire as into an ugly shell to mature the pearl of an inner life. The old artists, artisans, potters—the Bellinis, Angelos, Palissys, Della Robbias—reappeared in Rousseau, Milton, Bunyan—artists of an invisible beauty, disowning Art while frescoing the mind with ideals.

For a time the work of imagination went on in humble dwellings amidst Puritan plainness. But finally, even in the beginning of this generation, it began to be asked in England whether the mind and heart thus formed might not be honored with a fit environment of beauty. To this end London established its great School of Design and Decoration. Thereto have gravitated the fragments of a Past that has crumbled—images, altars, shrines, decorations lavished by genius on ideals ere they hardened to idols; imperial services, jewels, sceptres, wrought before kings became survivals and phantasms. It is England, land of beautiful homes, reviving the art of decoration for the Age of Humanity. She will no longer have the home to be homely. Her call has gone round the world, and temples and palaces deliver up their treasures that they may gather in London, there to teach the millions how they may beautify the latter-day temple, which is the Home, and refine the latter-day king, which is Man.

It is said that the Londoner may be known, in any part of the world where he may die, if his lungs are examined—they being of a sooty color. So much of his great metropolis he is doomed to carry with him wherever he may journey. London itself must forever bear, through and through, the effect of its fogs and its climate. Rain was its architect and Smoke its decorator. But let no one hastily conclude that their work has been all unlovely. John Ruskin has pointed it out as a characteristic of the greatest English artist, Turner, that there was nothing so ugly about England but he could bring beauty out of it; but that fine artist, Necessity, worked long before Turner in transmuting apparent disadvantages to advantages. “It is,” said Charles Kingsley, “the hard gray English climate which has made hard gray Englishmen.” There is as little terra-cotta on the Englishman’s house as on his character. It has been determined for him by Rain and Fog that he shall seek his pleasures by the fireside instead of in public gardens and fêtes. What beauty he can afford must be of the interior. Without, gray dirty brick and wall; within, every comfort and refinement: such are the decree of his superficially dismal decorators. Of course the wealthy Londoners have always fought against their hard climatic environment, and against the ever-encroaching ugliness which is the attendant shadow of millions massed together in the struggle for existence on a small island. There are still a few mansions, only a little way from the present centre of London, which attest the fine taste which its wealthy citizens have always tried to cultivate in the direction of architectural beauty. About two hundred and fifty years ago Northumberland House was described as “in the village of Charing.” That is now Charing Cross, the heart of the metropolis; a street runs over the site of Northumberland House. Where once was Charing hermitage is now a huge hotel and railway station. About two hundred years ago, when the Earl of Burlington was building Burlington House on Piccadilly, about half a mile west of Charing Cross, he was asked why he was building so far away in the country, and replied, “I am resolved to have no house beyond me.” The earl’s resolution was not kept. He lived to find himself amidst a noisy thoroughfare, and now one may travel five miles to the westward of his old country-seat without leaving the avenue of brick and mortar which passes its door. This migration of dwellings to ever-extending suburbs is, indeed, traced in much grander buildings than the tasteful old mansions which are being swallowed up because of their uneconomical occupancy of space: so much general stateliness is secured by the vast increase and diffusion of wealth; but the rarity with which the unique beauties of the older mansions are imitated, and the utter absence of any attempt at individuality in even the wealthiest new quarters—such as Belgrave Square—would seem to indicate that the Londoners have finally adopted it as a creed that external architecture and gardens must no longer be sought for by individuals, but possessed by all in communal forms, as public edifices, squares, and parks. It is now usual, in the new parts of London, for the grandest mansions of a terrace to own a large garden in common, to which each has entrance by a back gate, and to whose maintenance and ornamentation each family contributes a small sum per annum.

In its journey of eighteen centuries, from being that small trading-village mentioned by Tacitus—“not yet dignified with the name of colony”—to its present dimensions, covering 125 square miles, London has been formed by forces of use, by world-historical movements—powers not to be criticised. But we may admire in some of the characteristics of its mighty growth some of that beauty which ever works at the heart of the hardest utility. For example, in its expansion London is said to have swallowed up and built over more than three hundred villages; but in every case the village-green has been spared, and these are now represented by those beautiful and embowered squares which everywhere adorn the metropolis, constitute with the seven large parks its lungs, and make it the healthiest city of the world in proportion to its population. Though the ancient houses built by the wealthy were beautiful, and, wherever remaining, bring such large prices that one wonders why they should not be imitated, yet the homes of the lower classes in old times were far uglier than now. Especially were they made dismal by that barbarous “tax on light,” whose monuments may frequently be observed in windows walled up to avoid the window-tax. The poor had to live in houses illuminated from one or two windows, until the clever gentlemen of the Exchequer perceived the costliness of this means of revenue. As the Swiss mountaineers have come to admire goitres, unless belied by rumor, and as the city man, from having to put up with “high” game, has gradually come to prefer it, so the London builders for a long time placed few windows in houses, and seem to have thought the effect solid and “English,” as contrasted with the light and airy style of French houses. The newest streets of London show, however, that light on this subject has dawned upon the English architectural mind, through that into the homes of the people, to such an extent that the tax is now upon darkness. It is now accepted as a principle that as Smoke has had its way with the outside of the London habitation, hereafter the first decorator of the interior is to be—Light.

In these fragmentary first pages of a fragmentary work, it has been the author’s aim to outline certain general ideas and historical facts, which may illustrate their own illustrations as written in the following pages. It will be best seen, when approached from the historical side, what may be regarded as a necessary factor in English art or architecture, and what may be considered as experiment. This is the more important for the American, who is, in an especial sense, “heir of all the ages,” while not limited to the grooves prescribed by any. It is in America that we are to have the great Art of Arts—that whose task is to utilize the Arts of other lands and ages as pigments, to be combined into new proportions for unprecedented effects, and to invest fairer ideals. For America the author has written these contributions toward a knowledge of what has been done, and is being done, in England; but he would prefer now to burn his work rather than have it aid the retrogressive notion that Art in America is to copy the ornamentation or duplicate the work of other countries, much less of other ages. These things can mean for the artists and people of the United States nothing more than culture; and culture means not a mere eclectic importation of select facts and truths, but their recombination, in obedience to a new vital principle related to a further idea and wider purpose.

“COME,” said my friend, Professor Omnium, one clear morning, “let us take an excursion round the world!” My friend is a German, and he has such a calm familiarity with the unconditioned and the impossible, that a suggestion which, coming from another, would appear astounding, from him appears normal. This time, however, I look through his spectacles to see if his eyes have not a merry twinkle: they are quite serene. Visions of the Parisian play entitled Round the World in Eighty Days, thoughts of Puck and excursion tickets, rise before me, and I gravely pronounce the word “Impossible!”

“But,” says the professor, “Kant declares that it is too bold for any man, in the present state of our knowledge, to pronounce that word.”

“My dear friend,” said I, “it is among my dreams one day to visit India, China, Japan, California; but at present you might as well ask me to go with you to the moon.”

“You misunderstand,” replies Professor Omnium: “I do not propose to leave London. We can never go round the world, except in a small limited way, if we leave London. How much does an excursionist in India see of that country? Only a few cities, a few ruins, and the outside of some old temples, and he only sees a little of them. I stayed in Rome three days once—all the time I had there—trying to get a glimpse of some antiquarian treasures in the Bocca della Verita Church: first day, the church was closed to all outsiders by regulation; second day, the building was occupied by a pious crowd, and services were going on from daybreak to midnight; third day was so dark and rainy that I couldn’t see anything. On my way back I met an archæologist who had been in Nuremberg a week trying to scrutinize an old shrine; he had seen many priests, but only caught glimpses through railings of the shrine (St. Sebald’s, which exists in full-sized fac-simile at South Kensington), and the net result of his journey was represented in fifty photographs, just a little inferior to my own collection of the same—bought in Regent Street. I tell you, sir, there are few greater humbugs than this travelling about to see Objects (with a big O) of Interest. It’s expensive. Somebody says most travellers carry ruins to ruins, but the purses they carry away are the worst ruins of all. A man may well travel to see the world of men and women; but so far as art and antiquity are concerned, he who goes away from London shall have the experience of the boy in the fable, who dreamed about the beautiful blue hills on the horizon until he left his own flinty hill-side and journeyed to them; he found them flintier than his own, and, looking back, saw his own hill to be bluest after all.”

“Ah, then,” I put in—when Omnium is talking it is well to put in when one can—“you begin by asking me to go round the world, and end with sneering at all my dreams of India and Japan—”

“Not a bit of it,” cried the professor; “but ten thousand people and a dozen governments have been at infinite pains and expense to bring the cream of the East and of the West to your own doors: you turn your back, and pine for the skim-milk. Yesterday I was talking with Dr. Downingrue, an amiable and learned gentleman, who has been an official in the India House here for twenty years, and was lately given furlough for a year. That year he passed in Turkey and Persia. He told me that he wished to see a certain sacred book, written in ancient Zend, curiously illustrated with the most ancient pictures in the world, one of them possibly a portrait of the great Zoroaster himself. It was, he had heard, kept in the archives of the city of Bam Buzel, and he went a journey of three days and nights in a wagon to see and examine its text. Fancy his disgust at finding only an entry that the volume in question had been removed by order of the Shah in 1855, and that the Keeper of the Archives knew nothing whatever of its whereabouts. I took Downingrue by the hand, led him up one flight of stairs, and took down the old Zend book from its shelf there in Downing Street, where it had remained quietly, twenty feet over his head, while he worked twenty years for freedom to go searching for it in Persia! Now I heard you talking a few evenings ago about your hopes of one day seeing Shiraz and Mecca, the Topes in India, and the great Daiboots Buddha in Japan. I have called this morning to say, firstly, Don’t! secondly, Come, go round the world with me here in London! There is in the South Kensington Museum as noble a Buddha as that at Daiboots, which hundreds of thousands of pilgrims have journeyed for weeks to see: you have only to walk fifteen minutes to see it—not a copy either, but the huge bronze itself. You may travel through Mexico, Peru, and Chili for ten years, and in all that time never see one-hundredth part of the vestiges of their primitive life and history which you shall see in the British Museum. Greece?—and be captured by brigands. Professor Newton has Greece under lock and key, from Diana’s Temple to the private accounts of Pericles. Assyria?—you go, and find that the human heart of it has migrated; you come back, and George Smith reconstructs it for you—”

There was no sign that Omnium was ever coming to an end: the only way of stopping him is surrender; and it was not long before we were making our pilgrimage through Stone Age and Bronze Age, as recovered by the ages of Iron and Gold, and still more by the ages of Art and Science. The professor held a very positive theory that to travel round the world profitably you must first travel up to it, assimilating its past ages. Two recent stories had taken a strong hold on his imagination: one was about a learned historian of his own Germany, who had resolved that it was essential to the complete culture of his little son that the child should begin where the world began, believe implicitly in its fetiches, follow them till they changed to anthropomorphic gods and goddesses, these again till the Christian wand transformed them to fairies and demons, and so on. By this means the historian meant that his boy should bear in his individual periods of life corresponding periods in the growth of the race, and sum up at last the long column in a total of rational philosophy; but the boy is now growing old, and at last accounts had got only as far as Roman Catholicism, and there—stuck! The other story which haunted Omnium’s mind came from California, and was to the effect that upon the head of a woman in mesmeric sleep there was laid the fossil tooth of a mammoth, whereupon she at once gave as graphic a description of the world the extinct animal had inhabited when alive as could have been given by any paleontologist. “Both good stories, eh?” said the professor, with a hearty laugh; “almost as good as Pilpay’s fables: both of them fictitious notions ending in fantasies; but both, so to speak, prophetic types of what real science with real materials enables us to do to-day. We can, indeed, ‘interview’ the mammoth, as you Americans say; we can hang his portrait on our walls along with our other ancestors; and we can assimilate the education of the human race, not by beginning with being assimilated by its embryonic ages, risking failure to pick through the egg-shell at last, but by bringing to bear the lens of imagination, polished by science, and carrying so a cultured human vision through all the buried City of Forms.”

Since the few mornings when I had the pleasure of rambling with my German friend in the museums of London, and listening to his raptures, I have passed a great deal of time in those institutions, and with a growing sense that his enthusiasm was not misplaced. Indeed, so far as the museum at South Kensington is concerned—to which the present paper is especially devoted—to study it with care, and then stand in it intelligently, must, one would say, convey to any man a sense of his own eternity. Vista upon vista! The eye never reaches the farthest end in the past from which humanity has toiled upward, its steps traced in fair victories over chaos, nor does it alight on any historic epoch not related to itself: the artist, artisan, scholar, each finds himself gathering out of the dust of ages successive chapters of his own spiritual biography. And even as he so lives the Past from which he came over again, he finds, at the converging point of these manifold lines of development, wings for his imagination, by which he passes on the aerial track of tendency, stretching his hours to ages, living already in the Golden Year. There is no other institution in which an hour seems at once so brief and so long. A few other European museums may surpass this in other specialties than its own; though, when the natural history collections of the British Museum are transferred to their magnificent abode at South Kensington, one will find at the door of this museum a collection of that kind not inferior to the best with which Agassiz and others have enriched the Swiss establishments; but no other has so well classified and so well lighted an equal variety and number of departments, and objects representing that which is its own specialty—Man, as expressed in the works that embody his heart and genius.

The museum has been in existence about twenty-five years (1882). Its buildings and contents have cost the nation about one million pounds: an auction on the premises to-day could not bring less than twenty millions. Such a disproportion between outlay and outcome has led some to regard South Kensington as a peculiarly fortunate institution; but there has been no luck in its history. Success, as Friar Bacon reminds us, is a flower that implies a soil of many virtues. If magnificent collections and invaluable separate donations have steadily streamed to this museum, so that its buildings are unceasingly expanding for their reception, it is because the law of such things is to seek such protection and fulfil such uses as individuals can rarely provide for them. I remarked once to a gentleman, who did as much as any other to establish this museum, that I had heard with pleasure of various American gentlemen inquiring about it, and considering whether such an institution might not exist in their own country, and he said: “Let them plant the thing and it can’t help growing, and most likely beyond their powers—as it has been almost beyond ours—to keep up with it. What is wanted first of all is one or two good brains, with the means of erecting a good building on a piece of ground considerably larger than is required for that building. The good brains will be sure to recognize the fact that we have been doing a large part of their work for them at South Kensington. It is no longer a matter of opinion or of discussion how a building shall be constructed for the purpose of exhibiting pictures and other articles. The laws of it are as fixed as the multiplication table. Where there have been secured substantial, luminous galleries for exhibition, in a fire-proof building, and these are known to be carefully guarded by night and day, there can be no need to wait long for treasures to flow into it. Above all, let your men take care of the interior, and not set out with wasting their strength and money on external grandeur and decoration. The inward built up rightly, the outward will be added in due season.”

There is no presumption in the high claims of the curators and architects of the South Kensington Museum for the principle and method of their building. For it must be borne in mind that every difficulty that could conceivably present itself had to be solved by them in its extreme form: they had to deal with the gloomiest and dampest climate and the smokiest city in the world, and, a fortiori, they have solved every difficulty that can arise under less dismal skies. Nevertheless, this museum need not rest upon the claims made in its behalf by any authority. No statement can be so instructive and impressive as its own history, so far as that history exists; for, great as is the success it has attained, there is no one aspect of it which, if examined, does not reveal that it is rapidly growing to a larger future. I applied to a man who sells photographs of such edifices for pictures of the main buildings. He had none. “What, no photograph of the South Kensington Museum!” I exclaimed, with some impatience. “Why, sir,” replied the man, mildly, “you see, the museum doesn’t stand still long enough to be photographed.” And so, indeed, it seems; and this constant addition of new buildings, and of new decorations on those already erected, is the physiognomical expression of the rapid growth and expansion of the new intellectual and æsthetic epoch which called the institution into existence, and is through it gradually climbing to results which no man can foresee.

From a valuable paper on local archæological museums, contributed to the Building News, June 11th, 1875, I gather some of the following facts relating to the origin of the chief English museums. In the middle of the seventeenth century there was formed at Lambeth, in London, the first place that could be described as a museum. It was called “Tradescant’s Ark.” It consisted of objects of natural history collected in Barbary and other states by Tradescant, sometime gardener to Queen Elizabeth. This valuable collection was bequeathed, in 1662, by the younger Tradescant to Elias Ashmole, who gave it to Oxford in 1667, and it was the basis of the now valuable Ashmolean Museum of that place. Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, after graduation in 1585, associated with the antiquaries of his day, Joscelin, Lambard, Camden, and Noel, and collected rare books and antiquities, which became the nucleus of the British Museum. Sir Hans Sloane died one hundred and twenty years ago, and by will offered his collection of MSS. and artistic and natural curiosities (for which he had paid £50,000) to the nation for £20,000. In 1753 the Harleian collection was purchased. When a place in which to deposit these treasures was sought, Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace) was offered for £30,000; but an offer by Lord Halifax of Montague House (built by Hooke, the mathematician) for £10,000 was accepted, and so the museum stands at Bloomsbury. The public was first “admitted to view” (the phrase is still used at the museum) the collections in 1759. George II. presented the old Royal Library, founded by Henry VII., containing monastic spoils. The Lansdowne MSS. were bought in 1807 for £4925; the Burney collection, eleven years later, for £13,500; and in 1820 Sir J. Banks bequeathed his library of natural history. At the time of the foundation of the British Archaeological Association in 1844 there were outside of London but three museums, namely, at Oxford, York, and Salisbury. Now nearly every large town has its museum in which to treasure the monumental relics and natural curiosities of its neighborhood. York has the sarcophagi, tessellated pavements, and altars of Eboracum, Salisbury the spoils of Uriconium, Colchester the remains of Camulodunum, Bath those of Aquae Solis, and Cirencester those of Corinium. The Brown Museum at Liverpool is rich in Anglo-Saxon remains, and the important collection described by Wylie in his Fairford Graves is in the Ashmolean at Oxford. The Brown Museum derives its name from Sir W. Brown, who not only added to it a large building, but his collection (which cost him £50,000) of consular diptychs, Etruscan jewelry, Limoges enamels, Wedgwood pottery, and important Roman and Saxon antiquities. The Scarborough Museum has interesting British relics, among them a tree coffin of great rarity. The Exeter Museum has a good set of Celtic pottery, and bronze implements found in Devon. Wisbech possesses superb examples of mediaeval art and important Egyptian antiquities. In the Torquay Museum may be found the vast collection of flint implements found in the famous Kent’s Cavern through the industry of Mr. Pengelly, the geologist, along with remains of extinct animals discovered beside them. The Halifax Museum, in which Professor Tyndall passed his early scientific apprenticeship, is rich in the curiosities of the coal measures, and has important Egyptian as well as Roman remains. There are many other museums in the country—indeed, hardly any important town is without one; but I must not fail to mention a very interesting one at Canterbury. It contains Roman tessellated pavements; a large number of ancient terra-cotta forms, presented by the late Viscount Strangford, who brought them from the Greek isles, Egypt, and Asia Minor; two extremely interesting Runic stones found near Sandwich; and many such interesting antiquities as the “Curfew Bell” and “Couvre Feu;” and some very odd ones—for instance, the severed hand of Sir John Heydon, who was killed by Sir Robert Mansfield in a duel, anno 1600.

In a graphic article published some years ago Sir Henry Cole described (what it is almost impossible for the Londoner of to-day to realize) the condition of this metropolis at the beginning of the century. The only institution which then existed for preserving any object of art or science was the British Museum, which was founded in 1753, in which year a sum of £300,000 was raised by lottery to purchase certain collections—as that of Sir Hans Sloane, and the Cotton MSS.—over the drawing of which lottery (100,000 tickets at three pounds each), at Guildhall, the Lord Chancellor, the Speaker of the House of Commons, and the Archbishop of Canterbury presided! But this sole institution excited the very smallest interest in the country, and so late as forty years ago Croker jeered in Parliament at Bloomsbury as a terra incognita, and Carlyle’s brilliant friend and pupil, Charles Buller, wrote an article describing a voyage of exploration he had made to that region, with some account of the curious manners and customs of the inhabitants. “About a hundred visitors a day on an average,” says Sir Henry Cole (there are now as many visitors to the British Museum per hour), “in parties of five persons only, were admitted to gape at the unlabelled ‘rarities and curiosities’ deposited in Montague House. The state of things outside the British Museum was analogous. Westminster Abbey was closed except for divine service, and to show a closet of wax-work. Admittance to the public monuments in St. Paul’s and other churches was irksome to obtain, and costly: even the Tower of London could not be seen for less than six shillings. The private picture-galleries were most difficult of access, and, for those not belonging to the upper ten thousand, it might be a work of years to get a sight of the Grosvenor and Stafford collections. No national gallery existed, and Lord Liverpool’s government refused to accept the pictures now at Dulwich, offered by Sir Francis Bourgeois, even on condition of merely housing them. The National Portrait Gallery, the South Kensington Museum, and the Geological Museum were not even conceived. Kew Gardens were shabby and neglected, and possessed no museum. Hampton Court Palace was shown, by a fee to the house-keeper, one day in the week. No public schools of art or science existed in the metropolis or the seats of manufacture. The Royal Academy had its annual exhibition on the first and second floors of Somerset House, in rooms now used by the Registrar-general, whose functions then had no existence. It was only at the British Institution or at Christie’s auction-rooms that a youthful artist like Mulready could chance to see the work of an old master, as he has often told us. Dr. Birkbeck had not founded the present Mechanics’ Institute in Southampton Buildings, and the first stone of the London University, in Gower Street, was not laid. Not a penny of the public taxes was devoted to national education. Hard drinking was as much a qualification for membership of the Dilettanti Society as the nominal one of a tour in Italy. Men’s minds were more anxiously engaged with bread riots and corn laws, Thistlewood’s conspiracy and Peterloo massacres, Catholic emancipation and rotten boroughs, than with the arts and sciences, for the advancement of which, in truth, there was hardly any liking, thought, or opportunity.”

This being the condition of London, the state of things in other parts of the United Kingdom may easily be inferred. There are now fifteen important public museums and art galleries in or near London. The ancient buildings of interest are shown without fees. More than a million people visited a single one of these museums last year. There are seven large schools for art training in London alone, and 151 in the whole country, with 30,239 pupils. The number of pupils at South Kensington Art School for the scholastic year ending July, 1880, was 824. These numbers refer exclusively to those who mean to devote their lives to art. The official report for 1881 gives 4758 as the number of elementary schools in which art is taught, 768,661 as the number of children instructed, the total amount of the grants in aid of them being £43,203 in the same year.

Public interest in the treasures of art and science in London—whose extent was unknown to any one—first manifested itself in 1835, when Parliament caused an inquiry to be made into the state of the British Museum; a second committee inquired in 1847, a third in 1859. The result of these inquiries was a series of ponderous Blue-books, which few ever saw, but which that few studied very carefully. It finally burst upon the country that the British Museum and its collections had, up to 1860, cost three millions of pounds, and that it was “in hopeless confusion, valuable collections wholly hidden from the public, and great portions of others in danger of being destroyed by damp and neglect.” The commissioners of 1859 who made this report also pointed out the cause of the evils they recognized. The museum was in the hands of forty-seven trustees, each of whom seemed to think that there were plenty to manage the affair without his concerning himself individually in the matter. Never was costlier broth so near being spoiled by multiplicity of cooks, when Panizzi, by a sort of coup d’état, brought a strong executive control to bear upon it. It is a singular fact that even now the British government does not formally adopt the British Museum. The vote for supplies of its ways and means is given each year on a motion made by a member sitting on the opposition benches. During Mr. Gladstone’s administration it was made by the Right Hon. S. Walpole, a trustee of the museum; when Lord Beaconsfield was in power it was made by the Right Hon. Robert Lowe, also a trustee. The money is supplied grudgingly. There can hardly be found elsewhere men of such eminence in their own departments as Professor Newton, Reginald Stuart Poole, and Story-Maskelyne (the mineralogist); there can be found none who have done such enormous work in bringing order out of chaos in the British Museum; yet they receive salaries of six hundred and fifty pounds each for labors that deserve a thousand. The condition of this museum has much improved of late. The vast growth of its collections had crowded its literary and scientific employés into miserable unventilated cells, and their murmurings of years have until now been unheeded. When the first victim, the Talmudic scholar, Emanuel Deutsch, was dying, he said, “Perhaps when I am gone they will do something.” This was the hope of the thirty-eight scholars buried alive in the printed-book department. He died, and nothing was done. Then fell the second victim, Mr. Warren, head of the transcribing department. This caused a panic. The readers of the reading-room, many of whom suffer from the now medically recognized “Museum headache,” took the matter up. The trustees visited the room where the two scholars had perished, and condemned it. But several rooms only a little better were still used, and another able assistant, an eminent author, barely saved his life by resigning a post he had held in the museum for over twenty years. The principal librarian, Bond, and keeper of printed books, Bullen, have done much to improve the state of things: but there is still a great want of private rooms for the assistant librarians, who generally have to sit in draughty galleries, where no open fires are to be got at. That this huge building should have become absurdly inadequate for its contents and its original purpose indicates the vast progress of English science in recent years. The keepers of antiquities felt themselves bound to declare that there were valuable Egyptian, Assyrian, and Greek monuments and inscriptions, in the crypts and corners of the museum, quite as useless for scientific purposes as if they had remained buried in the lands where they were exhumed. Much relief, both to the assistants and to the scholars who have had to dig like Schliemann for some of the museum’s treasures, will follow the removal of the vast zoological collections to South Kensington. The final result will be that the British Museum will be specialized, and become the treasury of the national archives and the national library.

As for the matter of payment, it certainly constitutes the gravest problem besetting institutions of this character. The best work done for literature, art, and science (so far as they are connected with the state) is done on small salaries, a thousand pounds being considered a vast sum for great men. Even such men as Tyndall and Lockyer get less than that by their official positions. But these gentlemen all feel the danger that might arise if such work became so well paid as to allure the incompetent, and its offices become objects of political intrigue. At present no country is better served in such matters than England, such men as those mentioned being content with small salaries because of the ample means of research afforded them. And indeed it would appear enough to prevent the offices for scientific and other work of an intellectual character being sought for gain, if some clever statesman would invent a way of paying the additional sums needed “in kind,” but in some kind, also, not transmutable into values for other than the learned. It must be admitted that thus far no English minister has appreciated the necessity that scholars should have salaries sufficiently large to raise them above anxiety, and to render unnecessary the too frequent frittering away of invaluable time and power in a multiplicity of extraneous and lucrative employments.

The redemption of the British Museum, so far as it has proceeded, as well as the establishment of nearly every institution of importance to art or science in the country, was largely due to the instruction by example represented in the South Kensington Museum. This institution, it is important to remember, did not grow out of any desire to heap curiosities together or to make any popular display; it grew out of a desire for industrial art culture, and the germ of it was the School of Design which opened in a room of Somerset House, June 1st, 1837. This poor little school is now a thing to make fun of. It took over a month for it to obtain the eight pupils with which it began. The first act of its regulators seems to have been a rule that “drawing the human figure shall not be taught to the students.” Haydon insisted that there could be no training without the human figure. The government did not want artists, but men who could draw such patterns as should render it no longer necessary for English manufacturers to go to Lyons and Paris for such. Etty and Wilkie sat in the council beside silk-weavers and portly warehousemen. Fine-art students were actually excluded—this mainly because of the cry that the government would otherwise be taking bread out of the mouths of private teachers—and the School of Design in 1842 consisted of 178 pattern-drawers. Schools of a similar character were gradually established in some of the provincial manufacturing cities. And there had been about ten years of this sort of thing when the great Exhibition of 1851-52 took place.

Queen Victoria has described the May day when the Palace of Glass was opened in Hyde Park as the happiest of her life. She had witnessed one of those noble victories which leave no tears behind but such as may welcome glad tidings of good-will, and she had seen her hero wearing the only crown he coveted—that of success in a great achievement for European civilization. It is sad indeed that only as a widow does she live to realize the latest results of that day on her country.

The great Exhibition may be termed, so far as English art is concerned, the great revolution. Such a display of “florid and gorgeous tinsel,” to use Redgrave’s description, was never seen, unless in the realms of King Coffee. The articles from the Continent were glittering and showy enough, but those of Great Britain outglittered all, exciting the laughter of cultivated foreigners to such an extent that English gentlemen were scandalized and abashed without knowing precisely what was the matter. The Prince Consort, who was especially ashamed at the general disgust manifested for this tawdry English work, had brought with him from his careful training in Germany and at Brussels one excellent habit—that of deferring to the judgment of accomplished men in matters relating to their own specialties. When he found himself, as Chief Commissioner of the great Exhibition, the hero of a great aesthetic failure and of a great financial success—blushing for the fame of the country which had bestowed its highest honor upon him, and at the same time contemplating a net surplus of £170,000—the idea took possession of him that the least the money could do would be to begin the task of raising English work from the abyss of ugliness which had been so admirably disclosed; and that idea led him to consult artists of ability and men of taste, and to mediate between them and her Majesty’s complacent ministers, whom he managed to rouse into a happy state of bewilderment, which resulted in action.

The Prince Consort was, during his brief life, a fortunate man in many respects, but in nothing was he so fortunate as when, inspired by the best artistic minds in England, he induced the Queen to set apart some rooms at Marlborough House (now the residence of the Prince of Wales) for an industrial art collection and for art training, and when he persuaded her ministers to devote £5000 to the same purpose. He has thus made the great head-quarters of British art in some sense his monument. In 1852 the small collection of the School of Design in Somerset House was removed to Marlborough House, and the Board of Trade confided to Owen Jones, R. Redgrave, and Lyon Playfair the work of reorganizing the whole art training of the country. The collection transferred from Somerset House was trifling enough, but now there were added a number of articles that had been purchased from the Exhibition, and a still more remarkable collection, which has a curious history. After the French Revolution, when the infuriated people were prepared to destroy not only the noblesse, but the works associated with them, fine cabinets and beautiful china vanished out of Paris. At this time George IV.’s French cook gathered up a superb collection of old Sèvres china. This had long been distributed through the English palaces, and was even used for ordinary table service; it was now, by the Queen’s order, removed from the various palaces to Marlborough House, where it was at once recognized as the finest existing collection of a class of articles which was already exciting that competition among collectors which at present amounts to a mania. But the Queen’s best loan was her example. Ministers took up the matter with unwonted courage. Mr. Henley, of the Board of Trade, secured the Bandiuell pottery, Mr. Gladstone the Gherardini models, and the precedent was set which has since added the Bernal, Soulages, Soltikoff, Pourtalès, and other collections—one of the most curious being that of the Rev. Dr. Bock, a collection of mediaeval religious vestments. There is a myth still current that in one or two cases the secret agent of the British Museum had been bidding for some treasure against the secret agent of South Kensington; but it has no foundation. Once upon a time the British Museum and the Tower of London found themselves bidding against each other for a piece of old armor; but no similar accident could have occurred under the keen eye of Sir Henry Cole, who from first to last has been felt in the progress of this museum. Sir Henry developed a power of getting money for the museum, from the stingiest chancellors, unknown in the history of the English exchequer. He, with Mr. Richard Redgrave, explored Italy, and brought back many valuable treasures of early art.

In 1854 the first report of the newly-established Department of Science and Art was laid before Parliament. It was a Blue-book of 642 pages—so much being required for those interests of the country to which the Board of Trade had, in 1836, devoted the half of one page. This report and those which followed bore witness that a new enthusiasm had arisen in England for recovering its lost arts; but they increasingly proved also that the collections evoked from their hiding-places were already overflowing Marlborough House. In one sense this overflowing was of signal advantage, for it enabled the department to send a collection of four hundred beautiful specimens as a circulating museum through the provincial cities and towns—a plan which has been maintained by the museum, and also by the National Gallery of Fine Arts, with excellent results. The commissioners had not at that time, so far as their reports show, any notion of localizing the various schools of science and art at South Kensington. Indeed, no such expression as “South Kensington” had existed until 1856, when Earl Granville so christened the “Brompton Boilers,” which the government had empowered Mr. Cole to prepare for the transfer of the Marlborough House collection (voting £10,000 for the purpose), and which, with their three boiler-shaped tops, still stand as the seed-shell of the museum. It was little supposed then that the “Mr. Huxley” whom the report of 1856 speaks of as employed to collect specimens on the coast would ever be seated as he is now in a palatial science school at Kensington. There must, however, have been some very far-seeing eyes looking at things in those days, for the commissioners of the great Exhibition of 1851 persuaded the government to add to the Exhibition surplus of £170,000 enough to make £300,000, and to invest the sum in the vast Kensington Gore estate. This estate comprised between twenty-five and thirty acres of land, twelve of which belong to the museum, and has become the site of a great metropolis of science and art. The museum was opened on June 22d, 1857, by the Queen, accompanied by the Prince Consort and the Heir Apparent.

The removal of the collections of Marlborough House to South Kensington, and the establishment of the new movement in a centre of its own, with room to grow, was speedily followed by a grand event, namely, the donation by Mr. Sheepshanks of his superb collection of pictures to the nation. Mr. Sheepshanks supplies to gentlemen who wish to benefit the public about as good an example as they can find in modern annals. For many years he had welcomed artists to study and copy in the gallery opening from his dining-room, which so many of them now remember as an oasis in the wilderness which surrounded them in the last generation. But the owner of this gallery had observed that the Philistines of Parliament were still very strong: they had once refused to accept even a valuable collection of pictures (as already stated) from unwillingness to house them; and although they had got beyond that, and thankfully accepted the Vernon Gallery, he saw that the arrangements for giving shelter to this gallery were made very slowly. The National Gallery had a large portion of its Turner and its Vernon bequests housed at South Kensington, and a much larger portion of them hid away in its crypt, for twenty-five years, awaiting the hour when England should find out the magnificent works of which it is the heir, by seeing them on the new walls completed in 1876. Mr. Sheepshanks resolved to see his gallery—which was worth even then a hundred thousand pounds—attended to while he was yet alive. He offered his pictures to the country on the following conditions: that a suitable building should be erected at Kensington (which would remove them from the dust and smoke of the city); that they should never be sold; must be open to art students, and at times to the public; and that the public, especially the working-classes, should be permitted to view the same on Sunday afternoons. The government assented to all of these conditions except the last, and Mr. Sheepshanks was reluctantly compelled to add to that provision the words, “it being, however, understood that the exhibition of the collection on Sundays is not to be considered one of the conditions of my gift.”

Having thus summed up the history of the museum, it remains for me to consider its three aspects: (1) as to architecture and decoration; (2) its collections of objects; (3) its educational or art training method and character.

The accompanying map will show the series of buildings at South Kensington. There exists to the west of Exhibition Road a park of about ten acres, holding at the north the Royal Albert Hall, at the south the Museum of Natural History, and between these, on either side, the long line of arcade buildings containing the National Portrait Gallery, the Indian section, Naval Museum, Patent Office, the Museum of Scientific Apparatus, and, in addition, spacious halls for the display of machinery during exhibitions, for horticultural shows, and Mr. Frank Buckland’s methods of pisciculture. Such a collection of museums, answering the varied needs of science and art, cannot be found elsewhere—even within the limits of a nation. The gardens adjoining this series of buildings are beautifully adorned with statues and fountains, and will remain in the future, as they have been in the past, a favorite promenade, entered from Albert Hall and its extended galleries, in summer always bright with flowers, with music, and gay companies.

The building containing the courts was designed by the late Captain Fowke, of the Royal Engineers, and, I believe, there is no other building in this country more adapted to its purpose. The task assigned Captain Fowke was to build a picture-gallery eighty-seven feet long by fifty wide, with two floors, the upper to be lighted from above, and the lower open to the light from side to side, and to make the whole as near fire-proof as possible. The building is thirty-four feet above the ground-line to the eaves, and fifty to the ridge, and consists of seven equal bays, twelve feet in length and of the width of the building. The upper floor contains four separate rooms, two of forty-six by twenty feet, the others of thirty-five by twenty feet, lighted entirely from the roof, and giving a wall space of 4340 square feet available for hanging pictures. The lower floor is thrown into two unequal rooms of forty-six by forty-four feet and thirty-five by forty-four feet, each having a row of piers along the centre, the play of light from side to side being thus nearly unimpeded. Thus the upper floor has no windows, but as much wall space as possible, while the lower has no walls, but piers, as is demanded for the exhibition of objects in cases. The roof is double glazed, and the rule of lighting is that the height and width of the gallery should be the same, and the skylight half of the same. This renders it always easy for the spectator to avoid the glitter point on a picture, as may be seen by the accompanying diagram. The glitter point, altering with the position of the beholder, is at B, nine feet from the floor, when the beholder is at E2, or five feet from the wall; and the glitter descends to C, seven feet from the floor, when the beholder advances to E3. But if the spectator can recede to fifteen feet, the wall has no glitter up to thirteen feet. The skylight at South Kensington is brought as near as is consistent with avoiding glitter, and is twenty feet nine and a half inches from the floor. Just below the skylight run horizontal gas-pipes, with fish-tail burners projecting on two-inch brass elbows, and the light at night is as nearly as possible the same as in the day. When the gas was first put in this building there occurred an interesting controversy concerning the effect of gas on pictures, which elicited a valuable statement, jointly signed by Faraday, Hofmann, Tyndall, Redgrave, and Fowke, who had been appointed as a commission of inquiry, to the effect that coal-gas is innocuous as an illuminator of any pictures, if kept at a sufficient distance above them to avoid bringing into contact with the pictures the sulphuric acid caused by its combustion (22½ grains per 100 cubic feet of London gas).

In the large courts electric lamps are now used with much success. It is wonderful to note the beauty of porcelain and all objects of delicate decoration under the new light; it brings out the minute traceries better than daylight.

Security from fire here has been made as nearly absolute as possible, and Sir Philip Cunliffe Owen believes it impossible by any device to fire the museum; yet the water arrangements and vigilance at South Kensington are as complete as if the building were built of the ordinary materials. As a matter of fact, the choice of materials was made after long and patient scientific experiments. The main material is the best gray stock brick, with ornamental work of certain blue, red, and cream-colored bricks peculiar to some English counties. Some iron it was, of course, necessary to use for joists and girders, but in every case this iron has been isolated by being surrounded with a thick fire-proof concrete. The floor is of Minton tiles imbedded in Roman cement. The double roof is Mansard, and covered with a French tile (tuile courtois), selected at the Paris Exhibition of 1855.

The picture-gallery described above, made to hold the Sheepshanks collection, has had additions made behind it, in accordance with the original plan, of three large rooms, which contain various collections of pictures, and near the back entrance to these is the gallery of Raphael’s cartoons. All this series of picture-galleries constitutes an upper floor of a wing to two vast double show-rooms. One of these is a large square apartment, in which large numbers of marble and other antique monuments are displayed. The other, connected with it, is architecturally divided by slender pillars—between which, as an avenue, are show-cases, above and below—into two noble rooms with splendid arched ceilings. The first-named of these rooms (that which is without division, and single-roofed) has not yet received its wall decorations, which are to be a distemper half-way up, and above, a frieze of frescoes large as Raphael’s cartoons. The other show-room—with the double-arched ceiling—furnishes, as may be imagined, fine opportunities for wall decoration, as also for the ornamentation of floor and ceilings. The decoration here has not been completed, but it has gone far enough for the scheme to be judged by its effect.

And it is just here that a careful criticism is necessary. While the purely architectural work merits all the praise that can be claimed for it, securing an admirable play of light, making each division add its light to the other, and reducing the space occupied by pillars and other accessories to a minimum, the decorations are but measurably successful. The faults are due, I think, to the intention that the ornaments themselves should present some of the features of a collection of styles. The result proves that it would be better if the varied styles were exhibited in a court set apart for the purpose. The floor, for example, is rich in its varieties of tiles, there being some five or six of different designs and shades. It is true that the great central floors are made of tiles of uniform design and color, and that these—a deep brick red, with small green spots at the corners of each tile—are grave and good; but all around, where we pass through arch or door, there is a deep fringe of brilliant tiles, which are reflected into the glass cases nearest them, to the injury of the objects shown; and in the series of “cloisters,” as the spaces beneath the picture-gallery may be called, there are further experiments in floor tiles which militate against the effect of the articles exhibited in them. The ceilings in these cloisters, or side spaces, have been covered with Oriental decorations by the late Owen Jones; they are Indian, Persian, moresque, and of the greatest beauty, each coffer in the ceiling and each archway presenting a new design, and yet all in harmony: these being too far above the show-cases to affect any objects in them, are rightly placed; but the floor, as the necessary background to many objects in the rooms—many of which depend on delicate shades of color for their effect—will eventually, I suspect, have to be reconstructed, and made entirely of the grave hue which has happily been already adopted for the greater part of it. Ascending a little above the floor, it must be said also that there is too much brilliancy about the lower arches and their spandrels—too much white and gold. It is not only that this does not give a sufficiently subdued background for the bright glass or chased metals in the upper parts of the cases (on the ground-floor), but they are by no means the best supports for the grand series of life-sized figures in mosaic, on deep gold surfaces, which make the magnificent frieze of the upper wall.

NORTH COURT, NORTH-WEST CORNER, SHOWING CASTS OF THE BIGA (OR TWO-HORSE CHARIOT), FROM THE ORIGINAL IN MARBLE AT THE VATICAN, AND OF THE PULPIT BY GIOVANI PISANO, FORMERLY IN THE CATHEDRAL AT PISA.

It is these superb figures, representing the great artists of the past, which constitute the most salient feature of decoration in the museum. In this case (as in so many others in the museum) the scheme—due to the late Mr. Godfrey Sykes—of combining the purposes of general decoration with subjects of special interest in a museum, has been most fortunate: the general effect is noble, the figures interesting as portraits and as representations of costume, the varieties of mosaic in which they are produced being of value for comparison. There are thirty-six flat alcoves—eighteen on each side—and the figures in them are those of the chief artists in ornamentation, with the names of their designers beneath: Phidias (by Poynter); Apelles (Poynter); Nicola Pisano (Leighton); Cimabue (Leighton); Torel, the English goldsmith, d. 1300 (Burchett); William of Wykeham, bishop and architect of Winchester Cathedral, d. 1404 (Burchett); Fra Angelico (Cope); Ghiberti (Wehnert); Donatello (Redgrave); Gozzoli, one of whose Florentine frescoes, containing his own portrait, is in the museum, d. 1478 (E. Armitage); Luca della Robbia, specimens of whose terra-cotta work in the museum show him to have been a man of genius, d. 1481 (Moody); Mantegna (Pickersgill); Giorgione (Prinsep); Giacomo da Ulma, friar at Bologna and painter on glass, d. 1517 (Westlake); Leonardo da Vinci (J. Tenniel); Raphael (G. Sykes); Torrigiano (Yeames); A. Dürer (Thomas); P. Vischer (W. B. Scott); Holbein (Yeames); Giorgio, painter in majolica, d. 1552 (Hart); Michael Angelo (Sykes); Primaticcio, the Italian who made the decorations at Fontainebleau, d. 1570 (O’Neil); Jean Goujon, to whom is attributed the old carving in the Louvre, d. 1572 (Bowler); Titian (Watts); Palissy (Townroe); François du Quesnoy, Flemish ivory carver, d. 1546 (Ward); Inigo Jones (Morgan); Grinling Gibbons (Watson); Wren (Crowe); Hogarth (Crowe); Sir J. Reynolds (Phillips); Mulready (Barwell). The only very modern artist in this list is Mulready, and he is certainly unfortunate, looking as if Mr. Punch’s most cynical artist had been employed to depict him. The late Mr. Owen Jones has been well represented in a mosaic set in the wall near a staircase leading from the Oriental Court decorated by him. Mulready is the only bit of really ugly work in the series, although, of course, the merits of the others are unequal. The artists have evidently given careful archæological study to the costumes of each period, and in some cases—as Prinsep’s Giorgione, Scott’s Vischer, and Pickersgill’s Mantegna—the work is such as the grand old workers around need not be ashamed of. Of great interest, too, are the varieties of material of which the mosaics are composed, concerning which I can only say here that the Italian glass appears to me incomparably superior to the experiments in English ceramic wares.

The shape of this double room, it will be borne in mind, implies four large lunettes, one, that is, at each end of the two large roof-spans. One of these has been already filled by Sir Frederick Leighton, P.R.A., with an admirable allegorical painting representing the “Arts of War.” Here we see workmen forging every variety of armor, shields, weapons, and women buckling them on to knights, as is written in fabliaux of the Round Table. Sir Frederick has put his most graceful drawing and purest colors into this fine work. There is also in the gallery a design for a companion picture of the “Arts of Peace,” wherein the ladies are engaged in the pleasanter work of adorning themselves, and utilizing mirrors, while the men are toiling to provide the sinews for the gentler siege in which their own hearts are liable to capture. These works are scholarly, almost hypercritically exact in archæological details, and when the second is completed the court will be greatly improved.

To Mr. F. W. Moody, one of the most energetic and accomplished teachers at the museum, the institution is indebted for many instructive experiments and designs in the way of decoration. No one should fail to observe the very remarkable exterior wall decoration covering one entire side of the new School of Science, which is a most complete revival of the sgraffito work of the fifteenth century. This experiment by Mr. Moody of the high Renaissance in Italy has been placed on a wall of the building not visible from the streets, but only from the windows of the museum. It is analogous to the niello, which was graven in silver and the lines filled in with carbon, making a black picture on a white ground. (There is a good account of this ornamentation, said to be the origin of all engraving for printed work, in W. B. Scott’s Half-hour Lectures.) Mr. Moody’s experiment is made by filling in the hollows of the cement, presenting a multiplicity of scrolls, symbols, allegorical figures—Natura, Scientia, etc.—and portraits of scientific men. The stairway from which this vast work—covering the wall for four or five stories—can best be seen is another interesting experiment of Mr. Moody’s. As befits a stairway leading to the Ceramic Gallery, its ornaments are made of Minton porcelain. The steps and facings of the steps are a kind of mosaic made of hexagon pellets painted; the walls are panelled with white porcelain; and their effect under the light falling through large figured windows, toned rather than colored, is very good indeed.

Entering now the Ceramic Gallery, we find its contents illustrated by a very ingeniously devised series of window etchings (as they may be called), which are probably unique in the history of work on glass. The windows on one side of this room, fifteen in number, each double, were intrusted to Mr. William B. Scott, who as an archaeologist in art has few superiors. Mr. Scott designed no fewer than forty-eight large pictures, representing the history of ceramic art from the most ancient Chinese, Egyptian, Indian, and Persian down to Wedgwood; and these he has placed in the fifteen windows, where, unhappily, they are little observed, being without mention, much less description, in any work except that now before the reader. They are for the most part in black and white, colors being introduced only once or twice, and then but slightly. The first and second windows are devoted to the Chinese, their work being, if not the earliest, the most ancient in porcelain, and that which has most influenced the European art. Here is shown their whole method, from the preparation of the clay, the half-naked natives bringing the kaolin from caves in panniers, others steeping it in water, refining it in large mortars, and kneading it on tables. The potter is seen before his rude wheel, and forming the vessel by hand-pressure. And after this we trace his work to the furnace, and on to its place in the shop. This work implies the most patient study of original Chinese models. One window represents characteristic Chinese ornamentation—such as the royal dragon and the bird of paradise, and a bazar at Pekin. The third window represents early Egyptian art. The upper part shows the casting of brick by packing in boxes, and then turning it out, all under the whip of the taskmaster, the work and the whip being but little different to-day from what they were in the ancient days whose relics have been so diligently studied by Mr. Scott on the papyri of the British Museum. Beneath, a skilled workman is painting a large Canopus: he is on his knees, with his feet doubled behind him. One page, so to speak, of this window represents Assyrian art by a triumphal procession, in which immense vases are carried on ox trucks, and smaller ones on the heads of prisoners—a design based upon discoveries in Nineveh which show the great importance that people ascribed to earthenware. The fourth window is Greek and Etruscan. The Greek legend of the origin of painting—the daughter of the potter of Sicyon tracing on the wall the shadow of her lover on his leaving her for a journey—is exquisitely done. Next we see the girl applying her plan to her father’s vases. We have also depicted with learning the honorary uses of pottery among the Greeks, the vases given as prizes in public games, or as votive offerings for the dead, by which custom the finest examples we have were transmitted; and, finally, there is the genius of Death holding in her hand the cinerary urn. The fifth window is Hispano-Moresque. The earliest ware in Europe after the Samian of which we have any examples was that made by the Moors, who brought the art of making it from east of the Mediterranean. This was the famous “lustre-ware” which was supplied from Spain, which is now so eagerly sought by collectors, both on account of its beauty and as the origin of the Italian majolica. Specimens of this kind of pottery have been found by Layard at Nineveh and at Ephesus. There appears to be little doubt that it is of Persian origin. It must have been always very difficult to make; in the modern manufacture about fifty per cent. of the pieces come out of the furnace dull and worthless. The fine specimens seem to the workmen happy accidents rather than the steady results of any normal process upon which they can depend. The first design in this window of Mr. Scott’s represents the master-potter amidst his swarthy workmen watching the hour-glass beside the fire. This wonderful lustre was the result of some utilization of smoke in modifying the copper glaze, and was probably discovered by accident, as so many fine effects in the ceramic art have been. This beautiful ware has lately attracted especial attention in England because of the experiments which Mr. De Morgan, son of the late mathematician of University College, is making. He has tried nearly every kind of smoke influence upon copper and silver pigments, in contact with glaze and his success has been remarkable. These lustre-wares are still, I believe, made in some parts of Spain in a small way; also at Gubbio, in Italy; but the furnace of Mr. De Morgan at Chelsea is the most active and successful in bringing out such wares in all their varieties.