There is, of course, to be an Eisteddfod in 1896; and it appears that the Llandudno Executive Committee have been making some revolutionary proposals with reference to it. They have resolved that they "respectfully desire that the Gorsedd will see its way to concur in the subject for the chair being in any metre, and not restricted to an awdl. The Committee are aware that the awdl has antiquity and custom in its favour, but, while calculated to develop skill in metrical composition, the local Committee feel that the necessity of composing in the form of an awdl is fettering to the conception and imagination." I cannot say what an awdl is, but I am dead against fetters, and, therefore, I say, down with the dastardly, fettering awdl.

Swift, strike off the fetters, wherever they're found,

Let the song-loving Welshman go free and unbound.

To the awdl too long has he bended his knee,

But its fate has been sealed, and the Welshman is free;

As free as his ocean, as free as his breezes,

He shall write as he likes, in what metre he pleases;

And he faces his Gorsedd, and vows he won't dawdle

A manacled slave in the train of the awdl.

After this it seems somewhat bald and prosaic to read that

On the recommendation of "Hwfa Mon" (the Archdruid), "Eifionydd" (the registrar), "Cadvan," "Pedrog," "Gwynedd," and "Dyfed," of the Gorsedd Committee, who stated that the subject chosen for the arwrgerdd (heroic poem), for which a prize of £20 and a silver crown is offered, was unsuitable for an arwrgerdd, the subject was changed, "Llewelyn Fawr" being substituted for "St. Tudno."—Instead of the galar-gan, the subject of which was "Clwydfardd," for which £15 was the prize, it was decided to offer a prize of £15 and a gold medal for the best awdl on "Clwydfardd," the Gorsedd stating that an awdl would be much more appropriate, as the late Archdruid was a great admirer of the twenty-four metres. Instead of the hir a thoddaid "Cestyll Cymru" (Castles of Wales) it was decided to offer a prize of £2 2s. for the best hir a thoddaid "Beddargraph 'Elis Wyn o Wyrfai,'" and also £2 2s. for the best hir a thoddaid "Beddargraph 'Tudno.'"

The Bishop of Hereford has requested the parishes in his diocese to send up petitions respecting the Armenian atrocities. One of these parishes is Walford-on-Wye, and I propose to confer immortality upon the reply sent by its Vicar to the Bishop.

"I regret" (says this truly Christian cleric) "having been unable to respond in the way you desired to your appeal respecting the persecution of Christians in Armenia. My not doing so was owing to the circumstance that at the present time a remonstrance from our nation can have no moral weight whatever. We have now in office a Government which is exercising all its ingenuity in plans for the persecution and plunder of Christians here, and so long as we tolerate the continuance of such a Government in office the Turk would be justified in telling us to reform this scandal before we presume to remonstrate with him."

In other words, the Vicar of Walford-on-Wye disapproves of the Welsh Church Disestablishment Bill, and refuses on that account to join in a protest against the torture and murder of his Armenian fellow-creatures. The logic of the Vicar is as convincing as his Christian sympathy is admirable. Let him be known henceforth as the Vicar of Reason Wye.

What on earth is a "Rational Sick and Burial Association?" They possess one at Acton Turville; and, only the other day, it held great junketings. I may possibly have been rationally sick, but I have certainly never yet been rationally, or even irrationally, buried, nor, I take it, have the very vigorous members of the Association. However, they had a procession, which started from the club-room, headed by the Malmesbury band, and then walked to Badminton, calling at the Duke of Beaufort's, where they were all treated with refreshments. Imagine his sporting Grace's feelings at being called upon to treat with refreshments a procession of the rationally sick and buried. They then dined. The menu is not given, but no doubt included bread made from mummy-wheat, Dead-sea fruit, and copious libations of bier (spelling again!).

Close to Bristol, too, there is a place rejoicing in the name of Fishponds, where, at the Full Moon Hotel, the Loyal Pride of Fishponds Lodge of the Bristol Equalised District of the Order of Druids meets for its various celebrations. The members sometimes "perambulate the village, headed by the band of the Mangotsfield detachment of the Bristol Rifles."

Now strike the clashing cymbals, and sound the big bassoon,

The Loyal Pride of Fishponds Lodge has left the old "Full Moon,"

Yet, though their band be warlike, they mean nor war nor pillage,

'Tis charity that bids them thus perambulate the village.

No member of the Order would dare to come too late

When Fishponds calls her Druids out to celebrate a fête.

Then, while with martial music, the left foot on the beat,

The Lodge awakes the echoes loud in every village street,

The villagers of Fishponds forsake their early bed,

And each one at his window displays a nightcapped head,

Salutes the hoary Druids, nor fails to greet with cheers,

The Mangotsfield detachment of Bristol Volunteers.

A Correspondent writes to the Scotsman, protesting against the omission of the grey plover from the list of birds to be protected under the Wild Birds Protection Act. "That the eggs," he adds, "are gathered by keepers and others for sale, should certainly be no argument; and any keeper might well be ashamed to watch a poor harmless bird all day through binoculars for the purpose of making a few shillings by the sale of its eggs." We live and learn. I have been eating plover's eggs for years without the least suspicion that the poor harmless mother-bird had been shamefully watched through binoculars by a keeper in search of shillings. All the same. I heartily indorse the suggestion that the plover should be protected.

Sir Donald Currie must have the eye of an eagle. Speaking at a luncheon held in Newcastle the other day in connection with the Trinity Presbyterian Church, he declared that "nothing had ever charmed him more than to observe at the luncheon that day the marvellous ability, but much more the marvellous unanimity and Christian fellowship manifested by the Nonconformist bodies." I doff my cap to the man who can infer not only marvellous unanimity and Christian fellowship, but also marvellous ability from his observation of bodies at luncheon. After this it must be the merest child's-play to navigate the Tantallon Castle to the Baltic Canal.

At a recent meeting of the Blackrock Town Commissioners, so I gather from the Freeman's Journal, Dr. Kough, the Vice-Chairman, objected to the adoption of a petition in favour of the Intoxicating Liquors (Ireland) Bill. He said the petition had been carried by a side-wind. Obviously, in the Doctor's opinion, the only thing to be done was to Kough-drop it.

["Professor Drummond's 'Ascent of Man' was discussed in the Assembly of the Free Church and very severely handled."—Daily Telegraph.]

What? Sprung frae an ape wi' a danglin' bit tailie?

Evolved by a process o' naiteral law?

What? Me, Sir? An Elder i' Kirk an' a Bailie?

That boast o' the bluid o' the Yellow Macaw?

Ye'd gar be takin' me graunfeyther's Bible

An' write doun "Gorilla" the sire o' us a'?

Na, na! 'Tisna me that's the traitor tae libel

The family tree o' the Yellow Macaw.

We gang straught awa' through the son o' ta Phairshons

Tae Noah an' Adam, and back to the Fa',

An' nane but respectable kirk-gangin' pairsons

Hae place i' the tree o' the Yellow Macaw.

Baboons?—Leave the Sassenach, o'er his Manilla,

Tae boast as he will o' his Puggie*-Papa!

But strike me teetotal if e'er a gorilla

Shall sit i' the tree o' the Yellow Macaw!

*Anglice, Monkey.

Light and Heat; or, in a Concatenation accordingly.—Speaking of "the invisible parts of the solar spectrum," Dr. Huggins tells us the "ultra-red" has been traced to a distance nearly "ten times as long as the whole range of the visible or light-giving region of the spectrum." Nature, indeed, is "all of a piece." In politics, as in optics, the "Ultra-Red" lies beyond the "light-giving region," though, as Science says of its "gamut of invisible rays," they are perceived "by their heating effects." The S. D. F.'s and other wavers of the Red Flag, should study up-to-date optics.

"Sic Itur ad Astra."—The Balloon Society has presented "W. G." with its gold medal. Therefore has he pardonable cause for inflation. It is to be hoped that this will not have the effect of making him hit "skyers." In spite of the aëronaut medal, may we never see "e'er a naught" tacked on to W. G.'s name.

[Mr. Gladstone starts for a trip to the Baltic in the Donald Currie Ship Tantallon Castle, Wednesday, June 12.]

What a charming Surprise it is, to a Man who has looked to his Bicycle for Two Hours' Peace and Liberty a Day, to come down on his Birthday and find that his Wife and his Mother-in-Law have taken Lessons in secret, and will henceforth go with him always and everywhere!

Saturday.—Have just been reading in Temple Bar an article on the influence of sunshine on Shelley, Byron, Keats, Moore, Southey, and other poets. Never thought of that before. There is so little sunshine in London, and when there is one never sits out in it. That is why all the magazines reject my sonnets, and why no one will publish my tragedy in blank verse. Sunshine! Right on the top of one's bare head. That is the cure. The reason is obvious—Phœbus Apollo, the Divine Afflatus, and all that sort of thing. Must go somewhere into the sunshine at once. Brighton is near, Brighton is shadeless, Brighton under the June sunshine is hot. The very place. Shall now at last electrify the world. Go down by an evening train. Somewhat crowded. Whitsuntide, of course.

Sunday.—Glorious morning. Blaze of sunshine. Brighton is not an inspiring place for a poet. Walk along asphalted parade. Extremely hot. But that is just what I want. Still Shelley and the others did not advocate softened asphalte, to which one's boots almost stick. The beach is the right place. Lie down on the dusty shingle above high water mark, take off my hat, and abandon myself to the Divine Afflatus. Wait patiently for inspiration. Can only think how hot it is. Wonder if the Divine Afflatus could get through my hat. Put on my hat. Still no inspiration. Take my hat off again. Begin to become insensible in the warmth. Suddenly feel on the back of my head a sensation as of something striking me. Can it be the inspiration? No, it was a pebble. Jump up. Boys behind, aimlessly throwing stones, have hit me. Sudden inspiration to rush after them with uplifted stick. Sudden flight of boys. Pursue them over uneven shingle. Wonder if Shelley and the others ever did that. At last stop, breathless, hotter than ever. Find, with difficulty, another unoccupied space on beach, and lie down again. Become quite drowsy. Suddenly wake up. Must have been asleep for a long time. Sun going down. No inspiration yet, and no chance of Divine Afflatus to-day. Must wait till to-morrow. Head aching very much. Wonder if Shelley and the others had headaches when the D. A. was coming on. Consult Temple Bar. Apparently not. Very strange.

Monday.—Again blazing sunshine. Hotter than ever. This must bring on the D. A. if anything would. Again lie on beach. More crowded than yesterday. Some of the people seem friendly, and to be interested in my experiment, for they address me and advise me to get my hair cut. Could this possibly be advantageous to admit the D. A.? No. Shelley and the others wore their hair like mine, not cropped like a convict's. Tell this to my new friends. They laugh. I become angry. Then they tell me to keep my hair on. Curious instance of the vacillation of popular opinion. They go away singing. Pain in my head and sleepiness still worse. Can no longer keep awake. Abandon myself to D. A. Am suddenly aroused by someone shaking my arm. Open my eyes. Can hardly see anything. Awful pain in head. Shut my eyes again. My arm again shaken roughly. A voice says, "Now then, get up." Endeavour to lift my head but cannot. Never felt so ill before. Murmur feebly, "I can't. It's the D. A. coming on." Voice answers, "D. T. yer mean. None o' your gammon. You come along o' me." Begin now to understand that it is not Phœbus Apollo who is standing by me in a vision. It is not even a beautiful woman, as in Shelley's Alastor. It is a policeman. Must find precedent for this. Somehow my voice seems changed and uncertain, but I manage to murmur, "Temple Bar." "Oh yes," says the policeman, "you've been enough in the bar. Now yer can try the dock. Come along." He endeavours to raise me, but I again fall insensible.

Wednesday.—Remember dimly the horrible events of the last thirty-six hours. I was taken to the police-station, and brought before the magistrate. He would not even look at Temple Bar, and fined me for being drunk and incapable. I drunk and incapable! Oh heavens! To-day I am back in London. The sky is cloudy. No chance of the D. A. now. Shall give up poetry for ever, and for the future write words for songs.

Scene—An open space near Baymouth, the watering-place at which the County Yeomanry have been going through their annual training. Along one side of the ground is a row of drags and other carriages, occupied by the local magnates; along another, the less distinguished spectators stand in a thin line or occasional groups, waiting for the review to begin. In the centre, the inspecting officer is judging the best turned-out troop, while the remainder of the regiment are doing nothing in particular.

Yeomanry Non-Com. (who is leading an officer's horse and talking to a female friend of his and her brother with the sense of conferring a distinction upon them). Ah, 'tis not all play this yere trainin', I do assure ye. I've been so 'ard-worked all the week, with all the writin' I've had to do at the orderly room and thet, I've 'ardly 'ad time to live! But I like it, mind ye, I like it more every year I come out and so does my old 'errse, a' b'lieve. And there's this about it too—the girls don't come errfter a feller!

The Young Lady. Well, I'm sure! Now I should have thought when you're in the Yeomanry, it was just what——

The Y. N.-C. Tain't so—not in my case—that's all I can tell ye.

The Y. L. (with coquettish incredulity). Oh, I daresay. With that uniform, too! Why, I expect, if the truth was told, you know more than one young lady who's glad enough to be seen about with you.

The Y. N.-C. (complacently). More than one! Why, theer wurr eight I took out in a boat for a moonlight row on'y lawst night—nawn o' my seekin', but they wouldn't take no denial. I didn't want to be bothered with 'en. I've got other things to do besides squirin' a passel o' wimmin folk about, I hev.

The Y. L. You conceited thing, you! If that's the way you go on, I shan't talk to you any more!

The Y. N.-C. Well, you won't hev th' opportunity, for theer's the Captain calling me up. So long—and take care o' yerselves!

[He trots off, feeling that he has sufficiently impressed them.

The Y. L. (to her brother, with the superiority that comes of a finishing school with all the extras). Distinctly "country," isn't he?

Her Brother. Well, he can't help that. And he rides as straight as any chap I know.

The Y. L. Oh, he's a real good fellow, I know that; still he is just a little —— I did hope I'd polished him up a little while we were at the farm last summer; but there, I suppose you can't put refinement into some people!

Another Young Lady (to her Admirer). I can't make George out yet among them all—can you?

Her Admirer (and George's rival). Cawn't say as I've tried, partickler. But there's one there in the rear rank that hes a look of him; that one settin' all humped up nohow on his 'errse.

The Adored One. Oh, of course, if you're going to make out as George can't sit on a horse!

Her Admirer (sulkily). Well, I'd back myself to ride 'cross country agen Garge any day.

The Adored One. Then why don't you join the Yeomanry, like he has?

Her Admirer (who would if he could afford it). Why? 'Cause 'taint worth my while, if you want to know!

The Adored One. I'm sure it's a smart enough uniform—at least George looks quite 'andsome in it.

Her Admirer. He didn't look very 'andsome when I see him on parade this marnin'; the sun had peeled his nose a treat!

The Adored One. It's well there are some who are willing to make sacrifices for their country!

Mrs. Prattleton. Yes, so sad for him, poor dear; but of course whenever his father dies, he'll be quite comfortable. (Recognising a military acquaintance.) Oh, Captain Clinker, do come and tell me what they're supposed to be doing out there, and whether they've begun yet.

Capt. Clinker (R.A.). Nothin' much goin' on at present. Ah, they seem to be wakin' up now a bit. (As the band strikes up.) There's the general salute; now they're goin' to make a start.

Mrs. Pratt. Who is that little man in the baggy black frock, rather like a dressing-gown, and the cocked hat; and why is he galloping out here?

Capt. C. He's the inspectin' officer; takin' up his position for the march past, don't you know.

Mrs. Pratt. Oh; and they're all going to march past him. How nice! But there's another officer in a cocked hat; is he inspecting, too?

Capt. C. Only their tongues; he's the regimental Pill—the doctor, you know.

Mrs. Pratt. (disenchanted). I quite thought he must be a general at least. Dear me, there's one man in a red coat and a helmet. What is he doing here?

Capt. C. That's the adjutant.

Mrs. Pratt. Oh; and the adjutant always wears a helmet. I see. They've hung red silk round the kettledrums; (pleased) that's real soldiering, isn't it?

Officers (as the regiment marches past by squadrons). Right whe-eel! Eyes right! For-ward! Dress up to your leaders there!

Capt. C. (with languid approbation). The dressin's not half bad.

Mrs. Pratt. No, they're dressed very like Hussars—or is it Artillery I mean? I always had an idea the Yeomanry wore comic uniforms—with shirt-collars, you know, and old-fashioned milk-pail hats with feathers and things. But (disappointedly) there's nothing ridiculous about these. What a frisky animal that trumpeter is riding; look at him caracoling about!

Capt. C. Trumpeters and serjeant-majors always the best mounted.

Mrs. Pratt. Are they? I wonder why that is. (As the regiment ranks by in single file.) But they've all got beautiful horses.

Capt. C. (critically). H'm, they're a fair-lookin' lot. Fall off a bit behind, some of 'em.

Mrs. Pratt. Do they? Then they can't be very good riders, can they?

Capt. C. These fellows? They ought to be; most of 'em, you see, hunt their horses regularly.

Mrs. Pratt. (with a mental vision of dismounted troopers chasing their chargers about the ground). What fun! I should like to see them do that. (As the regiment trots past in sections.) But they don't seem to come off over the trotting.

Capt. C. Not quite; the leaders don't keep their distance, so the men can't keep up. Still, considering how short a time they've been out, you can't expect——

Mrs. Pratt. No; and they haven't tried to gallop yet, have they? Some of the horses are cantering now, though; it looks so much nicer than if they all trotted, I think.

Capt. C. Don't fancy their Colonel would agree with you there.

Mrs. Pratt. What a shame to keep those poor soldiers out there all by themselves; they don't have any fun, and they only get in the way of the others when they turn round. Oh, look at them now—they're all coming straight at us, and waving their swords!

Capt. C. Pursuin' practice at the gallop; doin' it rather decently, too.

Mrs. Pratt. But do you think we're safe just here? Suppose they can't stop themselves in time!

Capt. C. No danger of that; too heavily bitted to get out of hand.... There, you see, they're all wheelin' round. That'll be the wind up. Yes, they're drawn up in line; officers called to the front. Now the inspecting officer is makin' a few remarks, butterin' 'em up all round, you know. It's all over.

Mrs. Pratt. Really? It's been a great success, hasn't it? I enjoy a review so much better when they don't have any horrid firing. Don't you?

[Captain Clinker assents, to save trouble.

George's Rival (reflectively). 'Twas onfortnate fur Garge, him bein' th' only man as fell arf, so 'twas.

The Adored One. He didn't fall off—he only fell out. Didn't you hear him tellin' me the buckle of his stirrup broke?

George's Rival. Buckle or nawn, he come arf; that's all I'm sayin'. An' showed his sense, too, by keepin' out o' th' rest on it. But Garge was allays a keerful sart o' chap.

["At the Ludlow County Police Court, on May 27, Sir Charles Rouse Boughton, Baronet, of Downton Hall, a Justice of the Peace, applied for a protection order against Mr. John Baddeley Wood, of Henley Hall, a Justice of the Peace. The parties had a dispute over a waterway, and on leaving Middleton Church on Sunday, Mr. Wood, it was alleged, used coarse language to Sir Charles, and called him a liar three times. Sir Charles said he was in bodily fear of Mr. Wood, and thought if sureties to keep the peace were applied for he should be safer. The Bench granted the summons."—The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent.]

Sure, Wood and Boughton might full well

By closest ties be knit;

But water's caused them both to swell,

And brought about a split.

And now within their bosoms housed

Blind anger courses madly,

Sir Charles's temper has been Roused,

And Wood has lost his, Baddeley.

Mr. T. Dolling Bolton, M.P. for N.E. division of Derbyshire, has been explaining to his constituents at Eckington the reason for his voting against the Government on Mr. Lloyd-George's amendment to the Welsh Church Bill. He was under no obligation to party leaders or party as a party. There was no subsidy by the party, no assistance given by party speakers, and he had to rely upon the electors alone. These elementary political principles endorsed by unanimous vote of continued confidence in esteemed member. Vote moved in eloquent speech by Mr. Boden. No party assistance, no party voting, manly independence the thing for Boden. Leaders say it ought to be a thing "verboten," and Mr. T. E. Ellis filled with foreboding by latest revolt. Bolton voting blue bad enough, but the enthusiastic approval of his constituency quite a bolt from the blue.

Great heav'ns! Here, where's my paper, pen, and ink!

How is it all this while I have omitted you?

For her I've rhymed, and Her, and Her; don't think,

I beg then, that I'll from my duty shrink,

A duty to a lady smart and witty due.

I'm really sorry for this painful lapse

Of etiquette—'twas careless, now you mention it.

I thought—let's see, what did I think?—perhaps

You'd hardly time to read poetic scraps;

Your leisure's precious, and I dared not trench on it!

Then ladies of the Press bar compliments

(At least I seldom find they will permit any!),

So I'm impelled to write plain common sense,

As near as may be, and on no pretence

Aspire to high-flown ode or "lover's litany"!

But still you've asked me, and I'd much regret

Not to oblige you promptly, if I know a way;

The more so, as you've just dropped in to get

A cup of tea and smoke a c-g-r-tte.

(By Jove, I hope I haven't giv'n the show away!)

Well, I've not said much, but I've thought the more:

If I were fulsome in your praise, why, "Drat it!" you'd

Most probably remark, or "What a bore!"

So, therefore, please between the lines explore—

'Twas you who bade me thus descend to platitude!

'Arry says he was "much interested in 'earing of a nartickle in the St. James's Gazette last week, 'eaded The 'Aunt of the Otter. He 'opes the writer will next give us The Uncle of the Coolie."

Saturday.—Production of Harold. New Opera; music by Cowen, book by Sir E. Malet, British Representative man in service of Foreign Office, writing words for diplomatic, and words for musical notes. However good-tempered a composer may be, yet when he wants to write an opera he cannot get on without "having words." No time left to give full criticism on Harold, which achieved sufficient success to satisfy composer and librettist; it may be as well to state that there is nothing "old" in it, except in last syllable of name. Years ago favourite subject with artists was "the finding of the body of Harold." Sir Edward has found body; Cowen clothed it. Albani is its life and soul. Composer conducted. May probably be heard again this season; so no more at present.

My Baronite, constitutionally credulous, on reading the earlier works of John Oliver Hobbes, accepted the masculinity of the author as put forward on the title page. On reading The Gods, Some Mortals, and Lord Wickenham (Henry & Co.), he begins to doubt. No man, not the weakest-minded amongst us, habitually uses italics in writing a book. Moreover, none but a woman could draw such a creature as Mrs. Anne Warre. The more generous masculine nature could not imagine anything so unrelievedly undesirable. Doubtless she is made so bad the more strikingly to compare with Allegra, "whose charm was the charm of springtime and love, all the kind promises of the sunshine, the life, the tenderness, the warmth, the graciousness of nature." The book, the most ambitious, and, in point of length, the most important, that has come from the pen of John Oliver Hobbes, is marked by her gift of keen observation, that sees everything and sees through most people. Dialogue and narrative sparkle with felicitous turns, bubble over with epigram. There are boundless possibilities in John Oliver Hobbes; but she should turn her face more persistently to the sunlight. Dr. Warre and Allegra are so good and so pleasant, that the average reader would like a little more of them, and a little less of the almost impossible Mrs. Warre.

The proper study of mankind is man, and there could not be an apter tutor than Mr. Smalley. His Studies of Men (Macmillan), have, as he tells us in a preface, appeared for the most part in the New York Tribune. Everyone conversant with newspaper work will know that for many years Mr. Smalley's Letter from London to what, take it all in all, is the principal, certainly the weightiest, journal in the United States, has been its most prominent feature. A selection of these contributions have, happily, been rescued from the files of the newspaper, and are here presented. The Studies cover a wide range, but the subjects are all, in diverse fashion, interesting. One is struck with the extreme fairness of judgment displayed in dealing with men who stand so far apart as, for example, Mr. Arthur Balfour, Mr. Parnell, Mr. Spurgeon, Tennyson, Lord Rosebery, Sir William Harcourt, Mr. Froude, Mr. John Walter, and Lord Randolph Churchill. During his long residence in England Mr. Smalley has known these and others, personally and in their public aspect. He has stored a picture gallery in which posterity may see them as they lived, nothing extenuated nor anything set down in malice. By way of redressing afresh the balance between the Old World and the New, Mr. Smalley has turned his back on London, and, having all these years written about Europeans, for the edification of Transatlantic readers, is about to tell Europe, in the columns of the Times, something of the undercurrent of public affairs in the United States. He will find in himself a most damaging rival.

A Home-Cured Tongue.—At a meeting of the "Gaelic League" in Dublin the other day, "the proceedings were conducted exclusively in Irish." Dr. Douglas Hyde, the President, said that the movement was advancing in favour every day, and that, "if this regress continued, the future of the Irish language was assured." But how about the future of those who have to listen to it? He subsequently read a poem called "An Bhainrioghan Aluinn," and, after that had the hardihood to remark that "both young and old take a delight" in speaking the language. As Mr. Pickwick would have said to Dr. Peter Magnus Hyde,—"It is calculated to cause them the highest gratification."

Mem. by an Unlucky Amateur Dabbler in the City.—To go in for "Specs" is short-sighted policy.

"You're not leaving us, Jack? Tea will be here directly!"

"Oh, I'm going for a Cup of Tea in the Servants' Hall. I can't get on without Female Society, you know!"

"You will assist," quoth Mr. Punch to Toby, "in giving the Shahzada a cheery welcome on board the P. and O.'s Caledonia. And these," continued Mr. P., handing Toby a packet and a purse containing untold gold "are your secret instructions."

"They shall be faithfully obeyed," replied the ever-faithful Toby; adding, "À bon Shah, bon hur-rah!"

* * * * * *

Day lovely; voyage perfect. Father Thames at his best. Sir Thomas Sutherland, M.P. and O., and all the goodly company, drank the Shahzada's health most heartily. Then capital short speech from Right Honourable Fowler about India. Shahzada satisfied with dinner, gratified by reception. On deck the Shahzada called Toby aside. Interpreter intervened. "Detnaw ton! Tuoteg!" said the Shahzada, quietly, but authoritatively.

The interpreter retired, muttering to himself "Bow-strings for one." "Look here," said the Shahzada to Toby ... and they discussed affairs (Toby acting as Mr. P.'s representative) of such importance that they cannot be even hinted at in this or any other place. "And now," said the Shahzada, still speaking in his native language, of which this is a translation, "is it not true that one of your national institutions at Greenwich is——"

"The Fair?"

"Bah!" laughed the Shahzada, "that has long since vanished; so have the Pensioners at the Hospital. But——"

"There is still hospitality," murmured Toby, salaaming his very best.

"There is," returned the Shahzada, "and you shall show it."

"What can I do for you, your Royal Highness?" asked Toby.

The Shahzada drew him yet further apart from the envious crowd, and whispered in his ear.

"Your Royal Highness," answered Toby, "it shall be done. Command that the boat be stopped at Greenwich."

So the boat was stopped at Greenwich, and the Shahzada, with Toby, debarked. Great cheering.

* * * * * *

8 P.M.—Telegraphic Message from Toby to Mr. Punch, Fleet Street.

Cannot come to dinner. Shahzada and self enjoying tea and shrimps. All gone—except the shrimps. No money returned. Did it for one-and-ten, shall pocket difference. Shahzada says best entertainment ever had. See you later. Larks.

["The fifty-fifth contest on the cricket field between the rival counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire ended yesterday (June 5) in a victory for the representatives of the Red Rose by 145 runs, and the record now reads—Yorkshire won 23, Lancashire won 23, and 9 drawn."—The Leeds Mercury.]

Red rose and white! A pleasant summer sight,

As a Midsummer Dream may well imagine it!

How different far from the wild wordy fight

'Twixt furious Somerset and fierce Plantaganet!

Bramhall Lane Ground presents a peacefuller scene

Than that once witnessed in the Temple Garden.

Here's war of wickets, on a sward as green

And as unreddened as the glades of Arden.

Ward, not hot Suffolk, fights for the Red Rose,

Jackson, not Vernon, battles for the White One.

True York v. Lancashire are still the foes,

Nor is the issue now at stake a slight one;

But whether Jackson be twice bowled by Mold,

Or twice Peel give young Albert his quietus,

The battle is as friendly as 'tis bold.

Paul, with his eighty-seven, helps defeat us,

But brave Lord Hawke, our Captain, makes his pile,

And there is comfort in the score of Wainwright.

If Sugg and Baker make the Red Rose smile,

Hirst his true "Yorkers" down the pitch will rain right.

Some holiday-makers seek the grassy down,

And some will bask by seashore, or on sunny cliff,

Give me to watch the fine straight bat of Brown,

The bail of Milligan, the catch of Tunnicliffe,

Dead level now are Lancashire and York,

The Red Rose and the White bear equal blossoms.

Now comes the tug of war! Now must we work,

Active as catamounts, and sly as 'possums.

But this we know—that at our noble game,

With Hawke the hearty, and with stout McLaren,

The White Rose shall not have to blush with shame,

Nor the Red Rose, through funk, blanch and grow barren!

His New Title.—Dr. Grace, C.B. ("Companion of the Bat").

John Bull. "LOOK HERE,—WE'VE HAD ENOUGH OF YOUR PALAVER! ARE YOU GOING TO LET THE GIRL GO, OR HAVE WE GOT TO MAKE YOU?"

Ragged Urchin (who has just picked up very short and dirty end of a Cigarette). "Hi, Billy! Look 'ere! See what you've missed!"

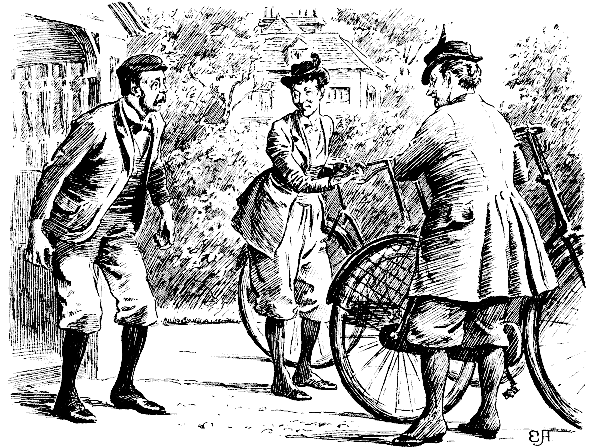

Dear Charlie,—You know I'm a "biker."

I told yer a good bit ago

'Ow I learnt to cavort on the cycle; and now,

from Land's End to Soho,

There isn't a scorchinger Scorcher than

'Arry, when fair on the spin.

Some might do me for pace, but for style,

and for skylark, I'd jest about win.

Lil Johnson—you know little Lil with the

copper-wire fringe and rum lisp!

'Er as flower-mounts Clerkenwell way, an'

wos donah to young Iky Crisp!

She's blue sancho on learnin' to "bike," so I

took 'er to Battersea Park,

As I'd 'eard wos the pitch for a spry lydy

cyclist as longed for a lark.

Larks, Charlie! It's spruce, and no

pickles! You know I fly cool without fidge,

But I wosn't prepared for the toppers as

treddle it nigh Chelsea Bridge.

No slow Surrey-siders, my pippin, but smart

bits o' frock from Mayfair;

It took me aback for a jiff, tho' of course

I wos speedy all there.

"Lor, 'Awwee!" lisped Lil, "thith ith

thplendid! But 'adn't we better sthand by?

Thee 'ow thpiffing they thpinth, thoth sthwell

lydith! No,'Awwee, I don't like ter twy.

Fanthy me in my cotton pwint wobbling

among thuch A-wonnerth ath thoth!

Look at 'er in the kniekerth and gaiterth, and

thpot t'otherth Balbriggan hoth!"

Poor Lil! She's no clarss, not comparative.

Ain't got no savvy, yer see;

And carn't 'old 'er own among quolity, not

with a flyer like me.

Don't like to be done, I don't Charlie; and

so I sez "Jest as yer like.

Ony, if I meant biking, in Battersea, dash it

old girl, I should bike!"

"Oh, 'awwee," sez she, "you're a 'ot 'un!

But let uth look on, dear, thith go;

Yer thee I carn't balanth, or pedal. I don't

want ter myke you no show."

"All right," I sez, 'orty an' airy. But ontry

noo, Charlie, old pal,

When I stocked up them beauties on bikes, I

wos most arf ashymed o' my gal.

One young piece in grey knicks and cream

cloth, and a sort of soft tile called a toke,

Took my fancy perdigious, dear boy. I'd

ha' blued arf-a-bull to 'ave spoke,

But a stiff-bristled swell in a dog-cart 'ad got

a sharp eye upon 'er;

And I couldn't ha' done the perlite without

raising a bit of a stir.

If I could ha' got rid o' Lil, I'd ha' mounted

my wheel, and wired in,

Balloon-tyred smart safety, old man! I'd

ha' showed Miss Grey Knicks 'ow to spin.

One tasty young thing wos in tears, 'cos the

bike she'd bespoke wosn't there,

I hoffered 'er mine, but the arnser I got wos

a freeze-me-stiff stare.

"Thtuck-up cat, my dear 'Awwee!" sez Lil.

"Well," sez I, "she may be a Princess,

As a lot o' them hexercise here. Lydy B.

and a young Marcherness

Do paternise Battersea Park on a bike;

leastways so I've bin told;

And the breakfusts and five-o'clock teas give

by dooks is a sight to behold."

"Garn, 'Awwee," snigs Lil, "you're a

kiddin'. But, thithorth! it ith a rum thing.

To thee Batterthea Park, ath wath onth all

kid-cwicket and kith-in-the ring,

Now the pet-pitch of thwell lydy thyclists!"

"It shows yer," I sez, "'ow things move.

From hansoms and bus-tops to bikes! Oh,

the lydies must keep on the shove.

"They borrow their barnies from hus, arter all,

Lil. Toffs want a new lark,

So they straddle the bike ah lah Brixton, and

tumble to Battersea Park.

'Divideds' and 'Knickers,' my dysy, are

sniffed at out Hislington way,

But when countesses mount 'em at Chelsea,

they're trotty and puffeck O K!"

World shifts it, old man, that's a moral!

We'll soon 'ave some duchess, on wheels,

A-cuttin' all records, and showing young

Zimmy a clean pair of 'eels.

Hadvanced Women? Jimminy-Whizz! With

the spars and the sails they now carry

They'll race us all round, pooty soon, and

romp in heasy winners! Yours,

'Arry.

There seems to be a feeling among lady writers that they also should have been remembered in the Birthday-honour distribution. That is all very well, but quite a new demand has been started by the Cork Constitution, which remarks,—

"It would not of course be regular to bestow a knighthood upon a lady; but the rule in the case of Mrs. Disraeli might be observed, and a Baroness be conferred upon the author of Lady Audley's Secret."

What would Miss Braddon do with a Baroness when she got her? Work her up into her next plot? Peeresses must be "cheap to-day," if they can be given away in this generous style.

(Cheapside, June 6, 1895.)

Oh, princely guest from Afghan clime,

The poet's lot is hard! Ah!

When he would find the proper rhyme,

To balance with Shah-zada!

I see the guardsman ride erect,

The bugle sounds! Aha!

My part should be, in verse correct,

To greet the Shahza-da!

Thy quantities have kill'd my song!

Despair! I'm off to Mada-

gascar, or anywhere! I long

To have it right. Shah-zădă?

A Fair Correspondent adds the letters "L. C. C." after her signature. She is not a member of the London County Council, but of the "Lady Cyclists Club."

Dear Mr. Punch,—A touching epitaph has lately come under my notice. It runs as follows:—

"HIC JACET ANONYMA.

She dwelt among the untrodden ways,

Where yellow asters throve,

A maid whom there were few to praise

And fewer still to love.

She lived unknown, so none can know

The hour she ceased to be,

Enough to know she has, and oh!

Pray, all men, R. I. P."

Is it possible that our old friend, the New Woman, that quite "impossible she," has left us for "another place"? It seems almost too good to be true.

P.S.—You will observe that she died a spinster, of uncertain age.

A sportsman, not particularly literary, but very fond of theatricals, says that he hears there is a play going on called Don Quickshot. He thinks the first syllable may have been accidentally omitted, but feels certain that the London Quickshot ought to make a hit.

Scoring for Dr. Grace.—"A Running Commentary."

(The Judge is not at home, and Brown, Q.C., asks permission to write him a Note.)

Mary Elizabeth Jane. "Would you like this Book, Sir? Master always uses it when he writes Letters!"

[Heavens! it's an English Dictionary!

The Standard, giving its account of "Speeches," at Eton, on Fourth of June, said, "The speakers were attired in Court dress, the Oppidans wearing their black school gowns." Since when have Oppidans worn "gowns," black or otherwise? Those who used to wear gowns were the Collegers. Surely the custom, sanctioned by some centuries, has not been changed. The "Oppidans," or Town Boys, could not possibly be metamorphosed into Gown Boys—at least so writes to us

Good Evans!—The Daily Telegraph reported "The Heroism of a Lady." The act and deed was that of Miss Evans, of Hythe, near Southampton, who, after rescuing a man and a woman from drowning, plunged in again, dived, and rescued a girl, who was sinking for the third and last time. The girl saved will ever gratefully remember Miss Evans as the lady who "brought her up by hand," and in finishing her education she will not neglect the extra-accomplishment of swimming. Honour to Miss Evans, who is a real female champion, not of the Salvation Army, but of a Nautical Salvage Corps!

(What the Heart of the Young Masher said to the Music-hall Singer.)

(A Long Way after Longfellow.)

Air—"The Day is Done."

The day is done, and the darkness

Falls from the brow of night,

Like a crape-mask drifting downward

From a burglar in his flight.

I see the lights of "the village"

Gleam through the evening mist,

And a feeling of dryness comes o'er me,

And a tiddley I can't resist.

A feeling of blueness, and longing

For a spree, and another drain;

It resembles sorrow only

As gooseberry does champagne.

Come, tip me some snappy poem,

Some iky and rorty lay,

That shall banish this chippy feeling,

And drive dull care away.

Not from the slow old stodges,

Not from the smugs sublime,

Who hadn't a notion of patter,

And were slaves to tune and time:

For, like chunks of Wagner's music,

They worrying thoughts suggest,

Dull duty, and dry endeavour,

And to-night I long for rest.

Tip a stave from some Lion Comique,

Whose songs are snide and smart,

And who makes you roar, like Roberts,

Till tears from your optics start.

Who, without thought or labour,

And "on his own," with ease,

Can whack out the ripping chorus

Of music-hall melodies.

Such songs have power to quicken

The pulse that beats low with care;

And come like the "Benedictine"

That follows the bill-of-fare.

So pick from the cad, or the coster,

Some patter—slang for choice;

And lend to the rhymes of the Comique

The tones of a stentor voice.

And our feet shall thump tune to the music,

And the bills that I cannot pay

Shall be folded up, like my brolly,

And as carefully put away.

(A Fable.)

A Goose that had miss-spent a long life, and, in addition to being old and ugly, was of a sour, ill-natured disposition, in despair of rendering herself any longer agreeable to her male acquaintances, conceived the desperate design of emancipating her female friends.

"It is intolerable," she declared to a large assemblage of the latter who flocked together directly the news of her design was noised abroad, "it is intolerable that, whilst all the good things of this life are reserved for the exclusive use and enjoyment of our male tyrants, we poor female creatures should be put off with feeble bodies and dowdy, unattractive plumage. I will go immediately to the King of Birds and demand the instant redress of these grievances under pain of my serious displeasure."

Scarcely had the Goose received the thanks of her audience for this valiant speech, when an Eagle, which chanced to be soaring at that moment in the heavens above them, and was attracted by the clamour that reached him, dropped suddenly to the earth in order to discover the cause of it; to whom the Goose, so soon as she was sufficiently recovered of her fears, humbly addressed her complaint.

"Foolish bird!" exclaimed the Eagle, when the Goose had made an end of her complainings, "know you not that what is fixed by Nature cannot possibly be altered by birds; and that if your sex have weaker bodies and a less attractive plumage than belong to us of the male gender, it is because Nature wills it so, and must be obeyed? Learn to be content with what you have, and cease envying those to whom Nature has been more prodigal of certain favours than she has been to you. Remember, also, foolish bird! that strength of mind is not the same thing with strength of body, and that though you may possess the one and pretend to despise the other, yet is Might the foundation of nearly all Right in the animal world, and must remain so because Nature will have it so and must be obeyed."

Shakspearian Characters at Manchester,—Last Friday H.R.H. the Prince of Wales's horse Florizel II. took the cake, or, rather, the Manchester Cup. Florizel II. is now Florizel I. In this new illustration to a Summer's not A Winter's Tale, Perdita should represent the race from the point of view of those who didn't win.

Another Title!! Supplemental Gazette of Birthday Honours.—Dr. W. G. Grace to be Cricket-Field-Marshal.

"Just look at Mr. Jones over there, flirting with that Girl! I always thought he was a Woman-hater?"

"So he is; but She's not here to-night!"

(A Dramatic Fragment from Drury Lane.)

Scene—The Auditorium of the National Theatre. Present the customary throng. A performance on the stage is occupying the spectators' wrapt attention. Newly-married couple in stalls holding a discussion in undertones.

Angelina. I am so glad, dear, you did not get a book of the words. It will be such a capital exercise for my Italian. I find that I can understand every word.

Edwin (happy to have saved the expense of purchasing a translated libretto). Quite so, dear. You can tell me what they are doing.

Ang. Certainly, dear. Look, they are now having supper. You see, the heroine called for candles, and the waiter put them on the table. And now they are talking about things in general. And that is Armande. And don't you see Marguerite is ill.

Edwin. Yes; she is fainting in front of a window.

Ang. Exactly. Italian is so easy—almost like English. She gives him a flower, and he goes away. He says adieu, and then the curtain falls.

Edwin Was that in Italian too?

Ang. Don't be absurd. (They discuss things in general, until the curtain rises on the Second Act.) Look, it is the same scene. You see, they are engaged. She is making love to him.

Edwin. Is that why he is sitting in a chair with his back to the audience while Marguerite strokes his hair?

Ang. Yes. While she is stroking his hair she is saying how fond she is of him. And now he is telling her how fond he is of her.

Edwin (after a quarter of an hour). What are they saying?

Ang. Oh, just the same thing over and over again. The Italian language is so beautiful. "Oh, Armande!" She calls him by his Christian name. She is so attached to him.

Edwin. But what was the meaning of that?

Ang. (at the end of the Act). Oh, don't you see, he said something that pleased her. Then she kissed him. Really, I had no idea how easy Italian was. Of course, one understands it from knowing French. (Entr'acte passes as before, and curtain rises on Act Three.) Ah, here we are at Auteuil. Yes, and here comes Marguerite with some flowers. Isn't it interesting?

Edwin. Isn't this piece rather like the Traviata?

Ang. I don't know. But I never saw the Opera. And there, that old gentleman has come to call upon Marguerite.

Edwin. Why, of course, like the old chap with the baritone song. Now I begin to understand Italian myself.

Ang. Do you, dear? Well, you see, he was going to be rude, and then they made it up, and she gave him a chair. And there, do you see? she leaves a letter for Armande. It is for him to read. And now she leaves him. And he is reading the letter.

Edwin. And doesn't seem to like it. And there's the old chap (without the song), and he is consoling him.

Ang. (after a glance at her playbill). Yes, because they are father and son. (The Fourth Act passes, and she explains to her husband that Marguerite has been playing at cards, and that Armande is very angry with her.) That's why he throws money at her.

Edwin. Rather a cad—Armande.

Ang. Oh, no. You know we must not judge foreigners by an English standard. (The last Act commences.) You see, she is very ill. That cradle covered with rugs is her bed.

Edwin. Indeed!

Ang. Yes. And that I suppose must be the doctor. I wonder what they are saying! This Act they all seem to be talking faster than they did in the others. That old woman was her friend. I wonder why she has left her like that!

Edwin. Didn't she say something like "What a rum go?" It is the only line I have understood since the commencement of the performance. What is she saying now?

Ang. (hesitating). Well, I am not quite sure. But you see she is very ill. She scarcely recognises Armande.

Edwin. What is he saying? What has he done with his father?

Ang. (perplexed). I can't quite follow this Act—they talk so fast.

Edwin. And, I say, why on earth have these two turned up? A lady in complete bridal costume—wreath, veil, and all—and a chap in evening dress. What on earth have they got to do with the story?

Ang. Don't you think, dear, we had better get a book?

Edwin (ignoring the suggestion). There's the poor thing dead!

Ang. Ah, I understood the last bit quite well. The Italian language is so much more expressive than our own, isn't it, dear?

Edwin. Darling, it is!

[Cigarettes, cabs, and Curtain.

Sundry damages or missing punctuation has been repaired.

Page 277: 'Christain' corrected to 'Christian'. "(says this truly Christian cleric)".

Page 282: 'Plantaganet', retained: perhaps an alternative spelling of

'Plantagenet'.