Project Gutenberg's The book of the ladies, by Pierre de Bourdeille Brantôme

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The book of the ladies

Illustrious Dames: The Reign and Amours of the Bourbon Régime

Author: Pierre de Bourdeille Brantôme

Release Date: April 12, 2013 [EBook #42515]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOOK OF THE LADIES ***

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

THE BOOK OF THE LADIES

The Reign and Amours of the

Bourbon Régime

A Brilliant Description of

the Courts of Louis XVI,

Amours, Debauchery, Intrigues,

and State Secrets, including

Suppressed and Confiscated MSS.

![]()

BY

Pierre de Bourdeïlle, Abbé de Brantôme

With Introductory Essay By

C.-A. Sainte-Beuve

Unexpurgated Rendition into English

PRIVATELY PRINTED FOR MEMBERS OF THE

VERSAILLES HISTORICAL SOCIETY

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1899.

By H. P. & Co.

——

All Rights Reserved.

| Édition de Luxe This edition is limited to two hundred copies, of which this is Number ............. |

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| DISCOURSE I. Anne de Bretagne, Queen of France | 25 |

| Sainte-Beuve’s remarks upon her | 40 |

| DISCOURSE II. Catherine de’ Medici, Queen, and mother of our last kings | 44 |

| Sainte-Beuve’s remarks upon her | 85 |

| DISCOURSE III. Marie Stuart, Queen of Scotland, formerly Queen of our France | 89 |

| Sainte-Beuve’s essay on her | 121 |

| DISCOURSE IV. Élisabeth of France, Queen of Spain | 138 |

| DISCOURSE V. Marguerite, Queen of France and of Navarre, sole daughter now remaining of the Noble House of France | 152 |

| Sainte-Beuve’s essay on her | 193 |

| DISCOURSE VI. Mesdames, the Daughters of the Noble House of France: | |

| Madame Yoland | 214 |

| Madame Jeanne | 215 |

| Madame Anne | 216 |

| Madame Claude | 219 |

| Madame Renée | 220 |

| Mesdames Charlotte, Louise, Magdelaine, Marguerite | 223 |

| Mesdames Élisabeth, Claude, and Marguerite | 229 |

| Madame Diane | 231 |

| Marguerite de Valois, Queen of Navarre | 234 |

| Sainte-Beuve’s essay on the latter | 243 |

| DISCOURSE VII. Of Various Illustrious Ladies: | |

| Isabelle d’Autriche, wife of Charles IX | 262 |

| Jeanne d’Autriche, wife of the Infante of Portugal | 270 |

| Marie d’Autriche, wife of the King of Hungary | 273 |

| Louise de Lorraine, wife of Henri III | 280 |

| Marguerite de Lorraine, wife of the Duc de Joyeuse | 282 |

| Christine of Denmark, wife of the Duc de Lorraine | 283 |

| Marie d’Autriche, wife of the Emperor Maximilian II | 291 |

| Blanche de Montferrat, Duchesse de Savoie | 293 |

| Catherine de Clèves, wife of Henri I. de Lorraine, Duc de Guise | 297 |

| Madame de Bourdeille | 297 |

| APPENDIX | 299 |

| INDEX | 305 |

| Pierre de Bourdeille, Abbé and Seigneur de Brantôme | Frontispiece | |

| From an old engraving by I. Von Schley. | ||

| Page | ||

| François de Lorraine, Duc de Guise | 8 | |

| By François Clouet; in the Louvre. | ||

| Discourse | ||

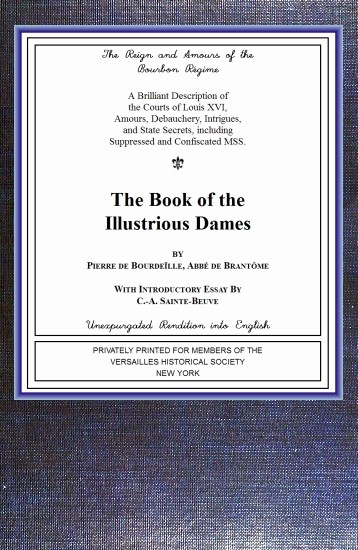

| I. | Tomb of Louis XII. and Anne de Bretagne | 34 |

By Jean Juste, in the Cathedral of Saint-Denis. The king | ||

| II. | Catherine de’ Medici, Queen of France | 44 |

| School of the sixteenth century; in the Louvre. | ||

| II. | Henri II., King of France | 52 |

| By François Clouet; in the Louvre. | ||

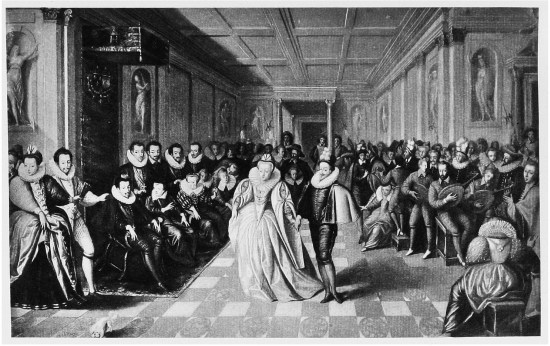

| II. | Ball at the Court of Henri III., with Portraits | 81 |

| Attributed to François Clouet; in the Louvre. See description in note to Discourse VII. | ||

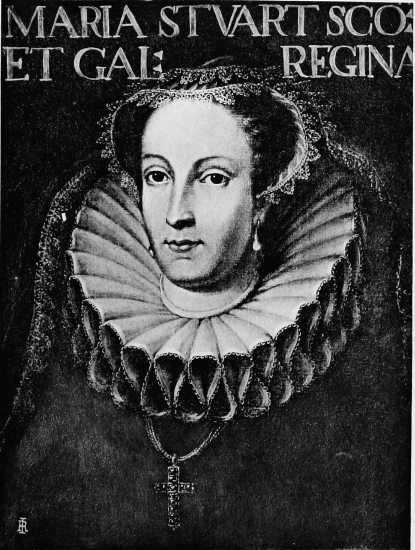

| III. | Marie Stuart, Queen of France and Scotland | 90 |

| Painter unknown; in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. | ||

| III. | The Same | 120 |

| School of the sixteenth century; Versailles. | ||

| V. | Henri IV., King of France | 166 |

| By Franz Pourbus (le jeune); in the Louvre. | ||

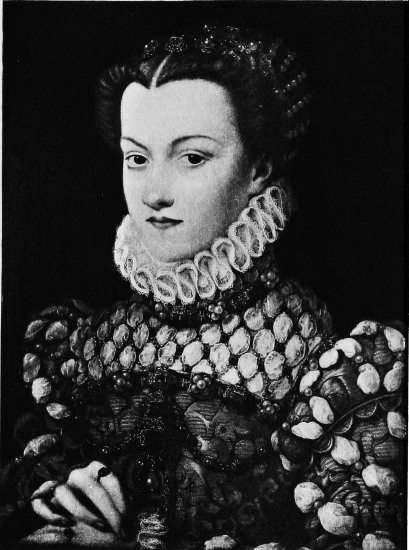

| V. | Élisabeth de France, Queen of Spain | 185 |

| By Rubens; in the Louvre. | ||

| V. | Coronation of Marie de’ Medici, With Portraits | 211 |

| By Rubens (Peter Paul); in the Louvre. See description in note to the Discourse. | ||

| VI. | François I., King of France | 224 |

| By Jean Clouet; in the Louvre. | ||

| VI. | Diane de France, Duchesse d’Angoulême | 232 |

| School of the sixteenth century; in the Louvre. | ||

| VII. | Isabelle d’Autriche, Wife of Charles IX. | 262 |

| By François Clouet; in the Louvre. | ||

| VII. | Charles IX., King of France | 271 |

| By François Clouet; in the Louvre. | ||

| VII. | Louise de Lorraine, Wife of Henri III | 280 |

| School of the sixteenth century; in the Louvre. | ||

| VII. | Henri III., King of France | 286 |

| School of the sixteenth century; in the Louvre. | ||

THE title, “Vie des Dames Illustres,” given habitually to one volume of Brantôme’s Works, is not that which was chosen by its author. It was given by his first editor fifty years after his death; Brantôme himself having called his work “The Book of the Ladies.”

One of his earliest commentators, Castelnaud, almost a cotemporary, says of him in his Memoirs:—

“Pierre de Bourdeille, Abbé de Brantôme, author of volumes of which I have availed myself in various parts of this history, used his quality as one of those warrior abbés who were called Abbates Milites under the second race of our kings; never ceasing for all that to follow arms and the Court, where his services won him the Collar of the Order and the dignity of gentleman of the Bedchamber to the King.

“He frequented, with unusual esteem for his courage and intelligence, the principal Courts of Europe, such as Spain, Portugal (where the king honoured him with his Order), Scotland, and those of the Princes of Italy. He went to Malta, seeking an occasion to distinguish himself, and after that lost none in our wars of France. But, although he managed perfectly all the great captains of his time and belonged to them by alliance of friendship, fortune was ever contrary to him; so that he never obtained a position worthy, not of his merits only, but of a name so illustrious as his.

“It was this that made him of a rather bad humour in his retreat at Brantôme, where he set himself to compose his books in different frames of mind, according as the persons who recurred to his memory stirred his bile or touched his heart. It is to be wished that he had written a discourse on himself alone, like other seigneurs of his time. He would then have shown us much, if nothing were omitted in it; but perhaps he abstained from doing this in order not to declare his inclinations for the House of Lorraine at the very moment of the ruin of all its schemes; for he was greatly attached to that house, and it appears in various places that he had more respect than affection for the House of Bourbon. It was this that made him take part against the Salic law, in behalf of Queen Marguerite, whom he esteemed infinitely, and whom he saw, with regret, deprived of the Crown of France.

“In many other matters he gives out sentiments which have more of the courtier than the abbé; indeed to be a courtier was his principal profession, as it still is with the greater part of the abbés of the present day; and in view of this quality we must pardon various little liberties which would be less pardonable in a sworn historian.

“I do not speak of the volume of the ‘Dames Galantes’ in order not to condemn the memory of a nobleman whose other Works have rendered him worthy of so much esteem; I attribute the crime of that book to the dissolute habits of the Court of his time, about which more terrible tales could be told than those he relates.

“There is something to complain of in the method with which he writes; but perhaps the name of ‘Notes’ may cover this defect. However that may be, we can gather from him much and very important knowledge on our History; and France is so indebted to him for this labour that I do not hesitate to say that the services of his sword must yield in value to those of his pen. He had much wit and was well read in Letters. In youth he was very pleasing; but I have heard those who knew him intimately say that the griefs of his old age lay heavier upon him than his arms, and were more displeasing than the toils and fatigues of war by sea or land. He regretted his past days, the loss of friends, and he saw nothing that could equal the Court of the Valois, in which he was born and bred....”

“The family of Bourdeille is not only illustrious in temporal prosperities, but it is remarkable throughout antiquity for the valour of its ancestors. King Charlemagne held it in great esteem, which he showed by choosing, when the splendid abbey of Brantôme was founded in Périgord, that the Seigneur de Bourdeille should be associated in that pious work and be, with him, the founder of the Monastery. He therefore made him its patron, and obliged his posterity to defend it against all who might molest the monks and hinder them in the enjoyment of their property.

“If we may rely on ancient deeds [pancartes] still in possession of this family, we must accord it a first rank among those which claim to be descended from kings, inasmuch as they carry back its origin to Marcomir, King of France, and Tiloa Bourdelia, daughter of a king of England.

“The same old deeds relate that Nicanor, son of this Marcomir, being appealed to by the people of Aquitaine to assist them in throwing off the Roman yoke, and having come with an army very near to Bordeaux, was compelled to withdraw by the violence of the Romans, who were stronger than he, and also by a tempest that arose in the sea. Nicanor cast anchor at an island, uninhabited on account of the wild beasts that peopled it, and especially certain griffins, animals with four feet, and heads and wings like eagles.

“He had no sooner set foot on land with his men than he was forced to fight these monsters, and after battling with them a long time, not without loss of soldiers, he succeeded in vanquishing them. With his own hand he killed the largest and fiercest of them all, and cut off his paws. This victory greatly rejoiced all the neighbouring countries, which had suffered much damage from these beasts.

“On account of this affair, Nicanor was ever after surnamed ‘The Griffin’ and honoured by every one, like Hercules when he killed the Stymphalides in Arcadia, those birds of prey that feed on human flesh. This is the origin of the arms which the Seigneurs de Brantôme bear to this day, to wit: Or, two griffins’ paws gules, onglée azure, counter barred.”

Pierre de Bourdeille, third son of François, Vicomte de Bourdeille and Anne de Vivonne de la Châtaignerie, was born in the Périgord in 1537, under the reign of François I. The family of Bourdeille is one of the most ancient and respected in the Périgord, which province borders on Gascony and echoes, if we may say so, the caustic tongue and rambling, restless temperaments that flourish on the banks of the Garonne. “Not to boast of myself,” says Brantôme, “I can assert that none of my race have ever been home-keeping; they have spent as much time in travels and wars as any, no matter who they be, in France.”

As for his father, Brantôme gives an amusing account of him as a true Gascon seigneur. He began life by running away from home to go to the wars in Italy, and roam the world as an adventurer. He was, says Brantôme, “a jovial fellow, who could say his word and talk familiarly to the greatest personages.” Pope Julius II. took a fancy to him. “One day they were playing cards together and the pope won from my father three hundred crowns and his horses, which were very fine, and all his equipments. After he had lost all, he said: ‘Chadieu bénit!’ (that was his oath when he was angry; when he was good-natured he swore: ‘Chardon bénit!’)—‘Chadieu bénit! pope, play me five hundred crowns against one of my ears, redeemable in eight days. If I don’t redeem it I’ll give you leave to cut it off, and eat it if you like.’ The pope took him at his word; and confessed afterwards that if my father had not redeemed his ear, he would not have cut it off, but he would have forced him to keep him company. They began to play again, and fortune willed that my father won back everything except a fine courser, a pretty little Spanish horse, and a handsome mule. The pope cut short the game and would not play any more. My father said to him: ‘Hey! Chadieu! pope, leave me my horse for money’ (for he was very fond of him) ‘and keep the courser, who will throw you and break your neck, for he is too rough for you; and keep the mule too, and may she rear and break your leg!’ The pope laughed so he could not stop himself. At last, getting his breath, he cried out: ‘I’ll do better; I’ll give you back your two horses, but not the mule, and I’ll give you two other fine ones if you will keep me company as far as Rome and stay with me there two months; we’ll pass the time well, and it shall not cost you anything.’ My father answered: ‘Chadieu! pope, if you gave me your mitre and your cap, too, I would not do it; I wouldn’t quit my general and my companions just for your pleasure. Good-bye to you, rascal.’ The pope laughed, while all the great captains, French and Italians, who always spoke so reverently to his Holiness, were amazed and laughed too at such liberty of language. When the pope was on the point of leaving, he said to him, ‘Ask what you want of me and you shall have it,’ thinking my father would ask for his horses; but my father did not ask anything, except for a license and dispensation to eat butter in Lent, for his stomach could never get accustomed to olive and nut oil. The pope gave it him readily, and sent him a bull, which was long to be seen in the archives of our house.”

The young Pierre de Bourdeille spent the first years of his existence at the Court of Marguerite de Valois, sister of François I., to whom his mother was lady-in-waiting. After the death of that princess in 1549 he came to Paris to begin his studies, which he ended at Poitiers about the year 1556.

Being the youngest of the family he was destined if not for the Church at least for church benefices, which he never lacked through life. An elder brother, Captain de Bourdeille, a valiant soldier, having been killed at the siege of Hesdin by a cannon-ball which took off his head and the arm that held a glass of water he was drinking on the breach, King Henri II. desired, in recognition of so glorious a death, to do some favour to the Bourdeille family; and the abbey of Brantôme falling vacant at this very time, he gave it to the young Pierre de Bourdeille, then sixteen years old, who henceforth bore the name of Seigneur and Abbé de Brantôme, abbreviated after a while to Brantôme, by which name he is known to posterity. In a few legal deeds of the period, especially family documents, he is mentioned as “the reverend father in God, the Abbé de Brantôme.”

Brantôme had possessed his abbey about a year when he began to dream of going to the wars in Italy; this was the high-road to glory for the young French nobles, ever since Charles VIII. had shown them the way. Brantôme obtained from François I. permission to cut timber in the forest of Saint-Trieix; this cut brought him in five hundred golden crowns, with which he departed in 1558, “bearing,” he says, “a matchlock arquebuse, a fine powder-horn from Milan, and mounted on a hackney worth a hundred crowns, followed by six or seven gentlemen, soldiers themselves, well set-up, armed and mounted the same, but on good stout nags.”

He went first to Geneva, and there he saw the Calvinist emigration; continuing his way he stayed at Milan and Ferrara, reaching Rome soon after the death of Paul IV. There he was welcomed by the Grand-Prior of France, François de Guise, who had brought his brother, the Cardinal of Lorraine, to assist in the election of a new pontiff.

This was the epoch of the Renaissance,—that epoch when the knightly king made all Europe resound with the fame of his amorous and warlike prowess; when Titian and Primaticcio were leaving on the walls of palaces their immortal handiwork; when Jean Goujon was carving his figures on the fountains and the façades of the Louvre; when Rabelais was inciting that mighty roar of laughter which, in itself, is a whole human comedy; when the Marguerite of Marguerites was telling in her “Heptameron” those charming tales of love. François I. dies; his son succeeds him; Protestantism makes serious progress. Montgomery kills Henri II., and François II. ascends the throne only to live a year; and then it is that Marie Stuart leaves France, the tears in her eyes, sadly singing as the beloved shores over which she had reigned so short a while recede from sight: “Farewell, my pleasant land of France, farewell!”

Returning to France without any warrior fame but closely attached by this time to the Guises, Brantôme took to a Court life. He assisted in a tournament between the grand-prior, François de Guise, disguised as an Egyptian woman, “having on her arm a little monkey swaddled as an infant, which kept its baby face there is no telling how,” and M. de Nemours, dressed as a bourgeoise housekeeper wearing at her belt more than a hundred keys attached to a thick silver chain. He witnessed the terrible scene of the execution of the Huguenot nobles at Amboise (March, 1560); was at Orléans when the Prince de Condé was arrested, and at Poissy for the reception of the Knights of Saint-Michel. In short, he was no more “home-keeping” in France than in foreign parts.

Charles IX., then about ten years old, succeeded his brother François II. in December, 1560. The following year Duc François de Guise was commissioned to escort his niece, Marie Stuart, to Scotland. Brantôme went with them, saw the threatening reception given to the queen by her sullen subjects, and then returned with the duke by way of England. In London, Queen Elizabeth greeted them most graciously, deigning to dance more than once with Duc François, to whom she said: “Monsieur mon prieur” (that was how she called him) “I like you very much, but not your brother, who tore my town of Calais from me.”

Brantôme returned to France at the moment when the edict of Saint-Germain granting to Protestants the exercise of their religion was promulgated, and he was struck by the change of aspect presented by the Court and the whole nation. The two armed parties were face to face; the Calvinists, scarcely escaped from persecution, seemed certain of approaching triumph; the Prince de Condé, with four hundred gentlemen, escorted the preachers to Charenton through the midst of a quivering population. “Death to papists!”—the very cry Brantôme had first heard on landing in Scotland, where it sounded so ill to his ears—was beginning to be heard in France, to which the cry of “Death to the Huguenots!” responded in the breasts of an irritated populace. Brantôme did not hesitate as to the side he should take,—he was abbé, and attached to the Guises; he fought through the war with them, took part in the sieges of Blois, Bourges, and Rouen, was present at the battle of Dreux, where he lost his protector the grand-prior, and attached himself henceforth to François de Guise, the elder, whom he followed to the siege of Orléans in 1563, where the duke was assassinated by Poltrot de Méré under circumstances which Brantôme has vividly described in his chapter on that great captain.

In 1564 Brantôme entered the household of the Duc d’Anjou (afterwards Henri III.) as gentleman-in-waiting to the prince, on a salary of six hundred livres a year. But, being seized again by his passion for distant expeditions, he engaged during the same year in an enterprise conducted by Spaniards against the Emperor of Morocco, and went with the troops of Don Garcia of Toledo to besiege and take the towns on the Barbary coast. He returned by way of Lisbon, pleased the king of Portugal, Sebastiano, who conferred upon him his Order of the Christ, and went from there to Madrid, where Queen Élisabeth gave him the cordial welcome on which he plumes himself in his Discourse upon that princess. He was commissioned by her to carry to her mother, Catherine de’ Medici, the desire she felt to have an interview with her; which interview took place at Bayonne, Brantôme not failing to be present.

In that same year, 1565, Sultan Suleiman attacked the island of Malta. The grand-master of the Knights of Saint-John, Parisot de La Valette, called for the help of all Christian powers. The French government had treaties with the Ottoman Porte which did not allow it to come openly to the assistance of the Knights; but many gentlemen, both Catholic and Protestant, took part as volunteers. Among them went Brantôme, naturally. “We were,” he says, “about three hundred gentlemen and eight hundred soldiers. M. de Strozzi and M. de Bussac were with us, and to them we deferred our own wills. It was only a little troop, but as active and valiant as ever left France to fight the Infidel.”

While at Malta he seems to have had a fancy to enter the Order of the Knights of Saint-John, but Philippe Strozzi dissuaded him. “He gave me to understand,” says Brantôme, “that I should do wrong to abandon the fine fortune that awaited me in France, whether from the hand of my king, or from that of a beautiful, virtuous lady, and rich, to whom I was just then servant and welcome guest, so that I had hope of marrying her.”

He left Malta on a galley of the Order, intending to go to Naples, according to a promise he had made to the “beautiful and virtuous lady,” the Marchesa del Vasto. But a contrary wind defeated his project, which he did not renounce without regret. In after years he considered this mischance a strong feature in his unfortunate destiny. “It was possible,” he says, “that by means of Mme. la marquise I might have encountered good luck, either by marriage or otherwise, for she did me the kindness to love me. But I believe that my unhappy fate was resolved to bring me back to France, where never did fortune smile upon me; I have always been duped by vain expectations: I have received much honour and esteem, but of property and rank, none at all. Companions of mine who would have been proud had I deigned to speak to them at Court or in the chamber of the king or queen, have long been advanced before me; I see them round as pumpkins and highly exalted, though I will not, for all that, defer to them to the length of my thumb-nail. That proverb, ‘No one is a prophet in his own country,’ was made for me. If I had served foreign sovereigns as I have my own I should now be as loaded with wealth and dignities as I am with sorrows and years. Patience! if Fate has thus woven my days, I curse her! If my princes have done it, I send them all to the devil, if they are not there already.”

But when he started from Malta Brantôme was still young, being then only twenty-eight years of age. “Jogging, meandering, vagabondizing,” as he says, he reached Venice; there he thought of going into Hungary in search of the Turks, whom he had not been able to meet in Malta. But the death of Sultan Suleiman stopped the invasion for one year at least, and Brantôme reluctantly decided to return to France, passing through Piedmont, where he gave a proof of his disinterestedness, which he relates in his sketch of Marguerite, Duchesse de Savoie.

Reaching his own land he found the war he had been so far to seek without encountering it; whereupon he recruited a company of foot-soldiers, and took part in the third civil war with the title of commander of two companies, though in fact there was but one. Shortly after this he resigned his command to serve upon the staff of Monsieur, commander-in-chief of the royal army. After the battle of Jarnac (March 15, 1569), being sick of an intermittent fever, he retired to his abbey, where his presence throughout the troubles was far from useless. But always more eager for distant expeditions than for the dulness of civil war, Brantôme let himself be tempted by a grand project of Maréchal Strozzi, who dreamed of nothing less than a descent on South America and the conquest of Peru. Brantôme was commissioned in 1571 to go to the port of Brouage and direct the preparations for the armament. It was this enterprise that prevented him from being present at the battle of Lepanto (October 7, 1571). “I should have gone there resolutely, as did that brave M. de Grillon,” he says, “if it had not been for M. de Strozzi, who amused me a whole year with that fine embarkation at Brouage, which ended in nothing but the ruin of our purses,—to those of us at least who owned the vessels.” But if the duties which kept him at Brouage robbed him of the glory of being present at the greatest battle of the age, it also saved him from being a witness of the Saint Bartholomew.

The treaty of June 24, 1573, put an end to the siege of Rochelle and the fourth civil war. Charles IX. died on May 30, 1574. Monsieur, elected the year before to the throne of Poland, was in that distant country when the death of his brother made him king of France. He hastened to return. Brantôme went to meet him at Lyons and was one of the gentlemen of his Bedchamber from 1575 to 1583. During the years just passed Brantôme, besides the principal events already named in which he participated, took part in various little or great events in the daily life of the Court, such as: the quarrel of Sussy and Saint-Fal, the splendid disgrace of Bussy d’Amboise, the death and obsequies of Charles IX., the coronation of Henri III., etc. Throughout them all he played the part of interested spectator, of active supernumerary without importance; discontented at times and sulky, but always unable to make himself feared.

The years went by in this sterile round. He was now thirty-five years old. The hope of a great fortune was realized no more on the side of his king than on that of his beautiful, virtuous, and rich lady. He is, no doubt, “liked, known, and made welcome by the kings, his masters, by his queens and his princesses, and all the great seigneurs, who held him in such esteem that the name of Brantôme had great renown.” But he is not satisfied with the Court small-change in which his services are paid. He is vexed that his own lightheartedness is taken at its word; he would be very glad indeed if that love of liberty with which he decked himself were put to greater trials. Philosopher in spite of himself, he finds his disappointments all the more painful because of his own opinion of his merits. He sees men to whom he believes himself superior, preferred before him. “His companions, not equal to him,” he says in the epitaph he composed for himself, “surpassed him in benefits received, in promotions and ranks, but never in virtue or in merit.” And he adds, with posthumous resignation: “God be praised nevertheless for all, and for his sacred mercy!”

Meantime, perchance a queen, Catherine de’ Medici or Marguerite de Valois, deigns to drop into his ear some trifling word which he relishes with delight. Henri de Guise [le Balafré], who was ten years younger than himself, called him “my son;” and the Baron de Montesquieu, the one that killed the Prince de Condé at Jarnac and was very much older than Brantôme, who had pulled him out of the water during certain aquatic games on the Seine, called him “father.” Such were the familiarities with which he was treated.

He was, it is true, chevalier of the Order of Saint-Michel, but that was not enough to console his ambition. He complained that they degraded that honour, no longer reserved to the nobility of the sword. He thinks it bad, for instance, that it was granted to his neighbour, Michel de Montaigne. “We have seen,” he says, “counsellors coming from the courts of parliament, abandoning robes and the square cap to drag a sword behind them, and at once the king decks them with the collar, without any pretext of their going to war. This is what was given to the Sieur de Montaigne, who would have done much better to continue to write his Essays instead of changing his pen into a sword, which does not suit him. The Marquis de Trans obtained the Order very easily from the king for one of his neighbours, no doubt in derision, for he is a great joker.” Brantôme always speaks very slightingly of Montaigne because the latter was of lesser nobility than his own; but that does not prevent the Sieur de Montaigne from being to our eyes a much greater man than the Seigneur de Brantôme.

Brantôme continued to follow the Court. He accompanied the queen-mother when she went in 1576 to Poitou to bring back the Duc d’Alençon, who was dabbling in plots. He accompanied her again when she conducted in 1578 her daughter Marguerite to Navarre; and at their solemn entry into Bordeaux he had the honour of being near them on the “scaffold,” or, as we should say in the present day, the platform. He had also the luck to hear at Saint-Germain-en-Laye King Henri III. make during his dinner, in presence of the Duc de Joyeuse (on whose nuptials the fluent monarch was destined to spend a million), a discourse worthy of Cato against luxury and extravagance.

In 1582, his elder brother, André de Bourdeille, seneschal and governor of the Périgord, died. He left a son scarcely nine years old. Brantôme had obtained from King Henri III. a promise that he should hold those offices until the majority of his nephew, on condition of transmitting them at that time. The king confirmed this promise on several occasions during the last illness of André de Bourdeille. But at the latter’s death it was discovered that he had bound himself in his daughter’s marriage contract to resign those offices to his son-in-law. The king considered that he ought to respect this family arrangement. Brantôme was keenly hurt. “On the second day of the year,” he says, “as the king was returning from his ceremony of the Saint-Esprit, I made my complaint to him, more in anger than to implore him, as he well understood. He made me excuses, although he was my king. Among other reasons he said plainly that he could not refuse that resignation when presented to him, or he should be unjust. I made him no reply, except: ‘Well, sire, I ought not to have put faith in you; a good reason never to serve you again as I have served you.’ On which I went away much vexed. I met several of my companions, to whom I related everything. I protested and swore that if I had a thousand lives not one would I employ for a King of France. I cursed my luck, I cursed life, I loathed the king’s favour, I despised with a curling lip those beggarly fellows loaded with royal favours who were in no wise as worthy of them as I. Hanging to my belt was the gilt key to the king’s bedroom; I unfastened it and flung it from the Quai des Augustins, where I stood, into the river below. I never again entered the king’s room; I abhorred it, and I swore never to set foot in it any more. I did not, however, cease to frequent the Court and to show myself in the room of the queen, who did me the honour to like me, and in those of her ladies and maids of honour and of the princesses, seigneurs, and princes, my good friends. I talked aloud about my displeasure, so that the king, hearing of what I said, sent me a few words by M. du Halde, his head valet de chambre. I contented myself with answering that I was the king’s most obedient, and said no more.”

Monsieur (the Duc d’Alençon) took notice of Brantôme, and made him his chamberlain. About this time it was that he began to compose for this prince the “Discourses” afterwards made into a book and called “Vies des Dames Galantes,” which he dedicated to the Duc d’Alençon. The latter died in 1584,—a loss that dashed once more the hopes of Brantôme and of others who, like him, had pinned their faith upon that prince. After all, Brantôme had some reason to complain of his evil star.

Then it was that Brantôme meditated vast and even criminal projects, which he himself has revealed to us: “I resolved to sell the little property I possessed in France and go off and serve that great King of Spain, very illustrious and noble remunerator of services rendered to him, not compelling his servitors to importune him, but done of his own free will and wise opinion, and out of just consideration. Whereupon I reflected and ruminated within myself that I was able to serve him well; for there is not a harbour nor a seaport from Picardy to Bayonne that I do not know perfectly, except those of Bretagne which I have not seen; and I know equally well all the weak spots on the coast of Languedoc from Grasse to Provence. To make myself sure of my facts, I had recently made a new tour to several of the towns, pretending to wish to arm a ship and send it on a voyage, or go myself. In fact, I had played my game so well that I had discovered half a dozen towns on these coasts easy to capture on their weak sides, which I knew then and which I still know. I therefore thought I could serve the King of Spain in these directions so well that I might count on obtaining the reward of great wealth and dignities. But before I banished myself from France I proposed to sell my estates and put the money in a bank of Spain or Italy. I also proposed, and I discoursed of it to the Comte de La Rochefoucauld, to ask leave of absence from the king that I might not be called a deserter, and to be relieved of my oath as a subject in order to go wherever I should find myself better off than in his kingdom. I believe he could not have refused my request; because everyone is free to change his country and choose another. But however that might be, if he had refused me I should have gone all the same, neither more nor less like a valet who is angry with his master and wants to leave him; if the latter will not give him leave to go, it is not reprehensible to take it and attach himself to another master.”

Thus reasoned Brantôme. He returns on several occasions to these lawless opinions; he argues, apropos of the Connétable de Bourbon and La Noue, against the scruples of those who are willing to leave their country, but not to take up arms against her. “I’faith!” he cries, “here are fine, scrupulous philosophers! Their quartan fevers! While I hold shyly back, pray who will feed me? Whereas if I bare my sword to the wind it will give me food and magnify my fame.”

Such ideas were current in those days among the nobles, in whom the patriotic sentiment, long subordinated to that of caste, was only developed later. These projects of treachery should therefore not be judged altogether with the severity of modern ideas. Besides, Brantôme is working himself up; it does not belong to every one to produce such grand disasters as these he meditates. Moreover, thought is far from action; events may intervene. People call them fate or chance, but chance will often simply aid the secret impulses of conscience, and bind our will to that it chooses.

“Fine human schemes I made!” Brantôme resumes. “On the very point of their accomplishment the war of the League broke out and turmoiled things in such a way that no one would buy lands, for every man had trouble enough to keep what he owned, neither would he strip himself of money. Those who had promised to buy my property excused themselves. To go to foreign parts without resources was madness,—it would only have exposed me to all sorts of misery; I had too much experience to commit that folly. To complete the destruction of my designs, one day, at the height of my vigor and jollity, a miserable horse, whose white skin might have warned me of nothing good, reared and fell over upon me breaking and crushing my loins, so that for four years I lay in my bed, maimed, impotent in every limb, unable to turn or move without torture and all the agony in the world; and since then my health has never been what it once was. Thus man proposes, and God disposes. God does all things for the best! It is possible that if I had realized my plans I should have done more harm to my country than the renegade of Algiers did to his; and because of it, I might have been perpetually cursed of God and man.”

Consequently, this great scheme remained a dream; no one need ever have known anything about it if Brantôme himself had not taken pains to inform us of it with much complacency.

The cruel fall which stopped his guilty projects must have occurred in 1585. At the end of three years and a half of suffering he met, he tells us, “with a very great personage and operator, called M. Saint-Christophe, whom God raised up for my good and cure, who succeeded in relieving me after many other doctors had failed.” As soon as he was nearly well he began once more to travel. It does not appear that he frequented the Court after the death of Catherine de’ Medici, which took place in January, 1589; but he was present, in that year, at the baptism of the posthumous son of Henri de Guise, whom the Parisians adopted after the father’s murder at Blois, and named Paris. Agrippa d’Aubigné, in his caricature of the Procession of the League, gives Brantôme a small place as bearer of bells. But was he really there? It seems doubtful; he makes somewhere the judicious reflection that: “One may well be surprised that so many French nobles put themselves on the side of the League, for if it had got the upper hand it is very certain that the clergy would have deprived them of church property and wiped their lips forever of it, which result would have cut the wings of their extravagance for a very long while.” The secular Abbé de Brantôme had therefore as good reasons for not being a Leaguer as for not being a Huguenot.

In 1590 he went to make his obeisance to Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, then confined in the Château d’Usson in Auvergne. He presented to her his “discourse” on “Spanish Rhodomontades,” perhaps also a first copy of the life of that princess (which appears in this volume), and he also showed her the titles of the other books he had composed. He was so enchanted with the greeting Queen Marguerite, la Reine Margot, gave him, “the sole remaining daughter of the noble house of France, the most beautiful, most noble, grandest, most generous, most magnanimous, and most accomplished princess in the world” (when Brantôme praises he does not do it by halves), that he promised to dedicate to her the entire collection of his works,—a promise he faithfully fulfilled.

His health, now decidedly affected, confined more and more to his own home this indefatigable rover, who had, as he said, “the nature of a minstrel who prefers the house of others to his own.” Condemned to a sedentary life, he used his activity as he could. He caused to be built the noble castle of Richemont, with much pains and at great expense. He grew quarrelsome and litigious; brought suits against his relations, against his neighbours, against his monks, whom he accused of ingratitude. By his will he bequeathed his lawsuits to his heirs, and forbade each and all to compromise them.

Difficult to live with, soured, dissatisfied with the world, he was not, it would seem, in easy circumstances. He did not spare posterity the recital of his plaints: “Favours, grandeurs, boasts, and vanities, all the pleasant things of the good old days are gone like the wind. Nothing remains to me but to have been all that; sometimes that memory pleases me, and sometimes it vexes me. Nearing a decrepit old age, the worst of all woes, nearing, too, a poverty which cannot be cured as in our flourishing years when nought is impossible, repenting me a hundred thousand times for the fine extravagances I committed in other days, and regretting I did not save enough then to support me now in feeble age, when I lack all of which I once possessed too much,—I see, with a bursting heart, an infinite number of paltry fellows raised to rank and riches, while Fortune, treacherous and blind that she is, feeds me on air and then deserts and mocks me. If she would only put me quickly into the hands of death I would still forgive her the wrongs she has done me. But there is the worst of it; we can neither live nor die as we wish. Therefore, let destiny do as it will, never shall I cease to curse it from heart and lip. And worst of all do I detest old age weighed down by poverty. As the queen-mother said to me one day when I had the honour to speak to her on this subject about another person, ‘Old age brings us inconveniences enough without the additional burden of poverty; the two united are the height of misery, against which there is one only sovereign cure, and that is death. Happy he who finds it when he reaches fifty-six, for after that our life is but labour and sorrow, and we eat but the bread of ashes, as saith the prophet.’”

He continued, however, to write, retracing all that he had seen and garnered either while making his campaigns with the great captains of his time, or in gossiping with idle gentlemen in the halls of the Louvre. It was thus he composed his biographical and anecdotical volumes, which he retouched and rewrote at intervals, making several successive copies. That he had the future of his writings much at heart, in spite of a scornful air of indifference which he sometimes assumed, appears very plainly from the following clause in his will:

“I will,” he says, “and I expressly charge my heirs to cause to be printed my Books, which I have composed from my mind and invention with great toil and trouble, written by my hand, and transcribed clearly by that of Mataud, my hired secretary; the which will be found in five volumes covered with velvet, black, tan, green, blue, and a large volume, which is that of ‘The Ladies,’ covered with green velvet, and another covered with vellum and gilded thereon, which is that of ‘The Rhodomontades.’ They will be found in one of my wicker trunks, carefully protected. Fine things will be found in them, such as tales, discourses, histories, and witticisms; which no one can disdain, it seems to me, if once they are placed under his nose and eyes. In order to have them printed according to my fancy, I charge with that purpose Madame la Comtesse de Duretal, my dear niece, or some other person she may choose. And to do this I order that enough be taken from my whole property to pay the costs of the said printing, and my heirs are not to divide or use my property until this printing is provided for. It is not probable that it will cost much; for the printers, when they cast their eyes upon the books, would pay to print them instead of exacting money; for they do print many gratis that are not worth as much as mine. I can boast of this; for I have shown them, at least in part, to several among that trade, who offered to print them for nothing. But I do not choose that they be printed during my life. Above all, I will that the said printing be in fine, large letters, in a great volume to make the better show, with license from the king, who will give it readily; or without license, if that can be. Care must also be taken that the printer does not put on another name than mine; otherwise I shall be frustrated of all my trouble and of the fame that is my due. I also will that the first book that issues from the press shall be given as a gift, well bound and covered in velvet, to Queen Marguerite, my very illustrious mistress, who did me the honour to read some of my writings, and who thought them fine and esteemed them.”

This will was made about the year 1609. On the 15th of July, 1614, Brantôme died, after living his last years in complete oblivion; he was buried, according to his wishes, in the chapel of his château of Richemont. In spite of his express directions, neither the Comtesse de Duretal nor any other of his heirs executed the clause in his will relating to the publication of his works. Possibly they feared it might create some scandal, or it may be that they could not obtain the royal license. The manuscripts remained in the château of Richemont. Little by little, as time went on, they attracted attention; copies were made which found their way to the cabinets and libraries of collectors. They were finally printed in Holland; and the first volume, which appeared in Leyden from the press of Jean Sambix the younger, sold by F. Foppons, Brussels, 1665, was that which here follows: “The Book of the Ladies,” called by the publisher, not by Brantôme, “Lives of Illustrious Dames.”

It is not easy to distinguish the exact periods at which Brantôme wrote his works. “The Book of the Ladies,” first and second parts,—Dames Illustres and Dames Galantes,—were evidently the first written; then followed “The Lives of Great and Illustrious French Captains,” “Lives of Great Foreign Captains,” “Anecdotes concerning Duels,” “The Rhodomontades,” and “Spanish Oaths.” Brantôme did not write his Memoirs, properly so-called; his biographical facts and incidents are scattered throughout the above-named volumes.

The following translation of the “Book of the Ladies” does not pretend to imitate Brantôme’s style. To do so would seem an affectation in English, and attract attention to itself which it is always desirable to avoid in translating. Wherever a few of Brantôme’s quaint turns of phrase are given, it is only as they fall naturally into English.

INASMUCH as I must speak of ladies, I do not choose to speak of former dames, of whom the histories are full; that would be blotting paper in vain, for enough has been written about them, and even the great Boccaccio has made a fine book solely on that subject [De claris mulieribus].

I shall begin therefore with our queen, Anne de Bretagne, the most worthy and honourable queen that has ever been since Queen Blanche, mother of the King Saint-Louis, and very sage and virtuous.

This Queen Anne was the rich heiress of the duchy of Bretagne, which was held to be one of the finest of Christendom, and for that reason she was sought in marriage by the greatest persons. M. le Duc d’Orléans, afterwards King Louis XII., in his young days courted her, and did for her sake his fine feats of arms in Bretagne, and even at the battle of Saint Aubin, where he was taken prisoner fighting on foot at the head of his infantry. I have heard say that this capture was the reason why he did not espouse her then; for thereon intervened Maximilian, Duke of Austria, since emperor, who married her by the proxy of his uncle the Prince of Orange in the great church at Nantes. But King Charles VIII., having advised with his council that it was not good to have so powerful a seigneur encroach and get a footing in his kingdom, broke off a marriage that had been settled between himself and Marguerite of Flanders, took the said Anne from Maximilian, her affianced, and wedded her himself; so that every one conjectured thereon that a marriage thus made would be luckless in issue.

Now if Anne was desired for her property, she was as much so for her virtues and merits; for she was beautiful and agreeable; as I have heard say by elderly persons who knew her, and according to her portrait, which I have seen from life; resembling in face the beautiful Demoiselle de Châteauneuf, who has been so renowned at the Court for her beauty; and that is sufficient to tell the beauty of Queen Anne as I have heard it portrayed to the queen-mother [Catherine de’ Medici].

Her figure was fine and of medium height. It is true that one foot was shorter than the other the least in the world; but this was little perceived, and hardly to be noticed, so that her beauty was not at all spoilt by it; for I myself have seen very handsome women with that defect who yet were extreme in beauty, like Mme. la Princesse de Condé, of the house of Longueville.

So much for the beauty of the body of this queen. That of her mind was no less, because she was very virtuous, wise, honourable, pleasant of speech, and very charming and subtile in wit. She had been taught and trained by Mme. de Laval, an able and accomplished lady, appointed her governess by her father, Duc François. For the rest, she was very kind, very merciful, and very charitable, as I have heard my own folks say. True it is, however, that she was quick in vengeance and seldom pardoned whoever offended her maliciously; as she showed to the Maréchal de Gié for the affront he put upon her when the king, her lord and husband, lay ill at Blois and was held to be dying. She, wishing to provide for her wants in case she became a widow, caused three or four boats to be laden on the River Loire with all her precious articles, furniture, jewels, rings and money,—and sent them to her city and château of Nantes. The said marshal, meeting these boats between Saumur and Nantes, ordered them stopped and seized, being much too wishful to play the good officer and servant of the Crown. But fortune willed that the king, through the prayers of his people, to whom he was indeed a true father, escaped with his life.

The queen, in spite of this luck, did not abstain from her vengeance, and having well brewed it, she caused the said marshal to be driven from Court. It was then that having finished a fine house at La Verger, he retired there, saying that the rain had come just in time to let him get under shelter in the beautiful house so recently built. But this banishment from Court was not all; through great researches which she caused to be made wherever he had been in command, it was discovered he had committed great wrongs, extortions and pillages, to which all governors are given; so that the marshal, having appealed to the courts of parliament, was summoned before that of Toulouse, which had long been very just and equitable, and not corrupt. There, his suit being viewed, he was convicted. But the queen did not wish his death, because, she said, death is a cure for all pains and woes, and being dead he would be too happy; she wished him to live as degraded and low as he had been great; so that he might, from the grandeur and height where he had been, live miserably in troubles, pains, and sadness, which would do him a hundred-fold more harm than death, for death lasted only a day, and mayhap only an hour, whereas his languishing would make him die daily.

Such was the vengeance of this brave queen. One day she was so angry against M. d’Orléans that she could not for a long time be appeased. It was in this wise: the death of her son, M. le dauphin, having happened, King Charles, her husband, and she were in such despair that the doctors, fearing the debility and feeble constitution of the king, were alarmed lest such grief should do injury to his health; so they counselled the king to amuse himself, and the princes of the Court to invent new pastimes, games, dances, and mummeries in order to give pleasure to the king and queen; the which M. d’Orléans having undertaken, he gave at the Château d’Amboise a masquerade and dance, at which he did such follies and danced so gayly, as was told and read, that the queen, believing he felt this glee because, the dauphin being dead, he knew himself nearer to be King of France, was extremely angered, and showed him such displeasure that he was forced to escape from Amboise, where the Court then was, and go to his château of Blois. Nothing can be blamed in this queen except the sin of vengeance,—if vengeance is a sin,—because otherwise she was beautiful and gentle, and had many very laudable sides.

When the king, her husband, went to the kingdom of Naples [1494], and so long as he was there, she knew very well how to govern the kingdom of France with those whom the king had given to assist her; but she always kept her rank, her grandeur, and supremacy, and insisted, young as she was, on being trusted; and she made herself trusted, so that nothing was ever found to say against her.

She felt great regret for the death of King Charles [in 1498], as much for the friendship she bore him as for seeing herself henceforth but half a queen, having no children. And when her most intimate ladies, as I have been told on good authority, pitied her for being the widow of so great a king, and unable to return to her high estate,—for King Louis [the Duc d’Orléans, her first lover] was then married to Jeanne de France,—she replied she would “rather be the widow of a king all her life than debase herself to a less than he; but still, she was not so despairing of happiness that she did not think of again being Queen of France, as she had been, if she chose.” Her old love made her say so; she meant to relight it in the bosom of him in whom it was yet warm. And so it happened; for King Louis [XII.], having repudiated Jeanne, his wife, and never having lost his early love, took her in marriage, as we have seen and read. So here was her prophecy accomplished; she having founded it on the nature of King Louis, who could not keep himself from loving her, all married as she was, but looked with a tender eye upon her, being still Duc d’Orléans; for it is difficult to quench a great fire when once it has seized the soul.

He was a handsome prince and very amiable, and she did not hate him for that. Having taken her, he honoured her much, leaving her to enjoy her property and her duchy without touching it himself or taking a single louis; but she employed it well, for she was very liberal. And because the king made immense gifts, to meet which he must have levied on his people, which he shunned like the plague, she supplied his deficiencies; and there were no great captains of the kingdom to whom she did not give pensions, or make extraordinary presents of money or of thick gold chains when they went upon a journey; and she even made little presents according to quality; everybody ran to her, and few came away discontented. Above all, she had the reputation of loving her domestic servants, and to them she did great good.

She was the first queen to hold a great Court of ladies, such as we have seen from her time to the present day. Her suite was very large of ladies and young girls, for she refused none; she even inquired of the noblemen of her Court whether they had daughters, and what they were, and asked to have them brought to her. I had an aunt de Bourdeille who had the honour of being brought up by her [Louise de Bourdeille, maid of honour to Queen Anne in 1494]; but she died at Court, aged fifteen years, and was buried behind the great altar of the church of the Franciscans in Paris. I saw the tomb and its inscription before that church was burned [in 1580.]

Queen Anne’s Court was a noble school for ladies; she had them taught and brought up wisely; and all, taking pattern by her, made themselves wise and virtuous. Because her heart was great and lofty she wanted guards, and so formed a second band of a hundred gentlemen,—for hitherto there was only one; and the greater part of the said new guard were Bretons, who never failed, when she left her room to go to mass or to promenade, to await her on that little terrace at Blois, still called the Breton perch, “La Perche aux Bretons,” she herself having named it so by saying when she saw them: “Here are my Bretons on their perch, awaiting me.”

You may be sure that she did not lay by her money, but employed it well on all high things.

She it was, who built, out of great superbness, that fine vessel and mass of wood, called “La Cordelière,” which attacked so furiously in mid-ocean the “Regent of England;” grappling to her so closely that both were burned and nothing escaped,—not the people, nor anything else that was in them, so that no news was ever heard of them on land; which troubled the queen very much.[2]

The king honoured her so much that one day, it being reported to him that the law clerks at the Palais [de Justice] and the students also were playing games in which there was talk of the king, his Court, and all the great people, he took no other notice than to say they needed a pastime, and he would let them talk of him and his Court, though not licentiously; but as for the queen, his wife, they should not speak of her in any way whatsoever; if they did he would have them hanged. Such was the honour he bore her.

Moreover, there never came to his Court a foreign prince or an ambassador that, after having seen and listened to them, he did not send them to pay their reverence to the queen; wishing the same respect to be shown to her as to him; and also, because he recognized in her a great faculty for entertaining and pleasing great personages, as, indeed, she knew well how to do; taking much pleasure in it herself; for she had very good and fine grace and majesty in greeting them, and beautiful eloquence in talking with them. Sometimes, amid her French speech, she would, to make herself more admired, mingle a few foreign words, which she had learned from M. de Grignaux, her chevalier of honour, who was a very gallant man who had seen the world, and was accomplished and knew foreign languages, being thereby very pleasant good company, and agreeable to meet. Thus it was that one day, Queen Anne having asked him to teach her a few words of Spanish to say to the Spanish ambassador, he taught her in joke a little indecency, which she quickly learned. The next day, while awaiting the ambassador, M. de Grignaux told the story to the king, who thought it good, understanding his gay and lively humour. Nevertheless he went to the queen, and told her all, warning her to be careful not to use those words. She was in such great anger, though the king only laughed, that she wanted to dismiss M. de Grignaux, and showed him her displeasure for several days. But M. de Grignaux made her such humble excuses, telling her that he only did it to make the king laugh and pass his time merrily, and that he was not so ill-advised as to fail to warn the king in time that he might, as he really did, warn her before the arrival of the ambassador; so that on these excuses and the entreaties of the king she was pacified.

Now, if the king loved and honoured her living, we may believe that, she being dead, he did the same. And to manifest the mourning that he felt, the superb and honourable funeral and obsequies that he ordered for her are proof; the which I have read of in an old “History of France” that I found lying about in a closet in our house, nobody caring for it; and having gathered it up, I looked at it. Now as this is a matter that should be noted, I shall put it here, word for word as the book says, without changing anything; for though it is old, the language is not very bad; and as for the truth of the book, it has been confirmed to me by my grandmother, Mme. la Seneschale de Poitou, of the family du Lude, who was then at the Court. The book relates it thus:—

“This queen was an honourable and virtuous queen, and very wise, the true mother of the poor, the support of gentlemen, the haven of ladies, damoiselles, and honest girls, and the refuge of learned men; so that all the people of France cannot surfeit themselves enough in deploring and regretting her.

“She died at the castle of Blois on the twenty-first of January, in the year 1513, after the accomplishment of a thing she had most desired, namely: the union of the king, her lord, with the pope and the Roman Church, abhorring as she did schism and divisions. For that reason she had never ceased urging the king to this step, for which she was as much loved and greatly revered by the Catholic princes and prelates as the king had been hated.

“I have seen at Saint-Denis a grand church cope, all covered with pearls embroidered, which she had ordered to be made expressly to send as a present to the pope, but death prevented. After her decease her body remained for three days in her room, the face uncovered, and nowise changed by hideous death, but as beautiful and agreeable as when living.

“Friday, the twenty-seventh of the month of January, her body was taken from the castle, very honourably accompanied by all the priests and monks of the town, borne by persons wearing mourning, with hoods over their heads, accompanied by twenty-four torches larger than the other torches borne by twenty-four officers of the household of the said lady, on each of which were two rich armorial escutcheons bearing the arms emblazoned of the said lady. After these torches came the reverend seigneurs and prelates, bishops, abbés, and M. le Cardinal de Luxembourg to read the office; and thus was removed the body of the said lady from the Château de Blois....

“Septuagesima Sunday, twelfth of February, they arrived at the church of Notre-Dame des Champs in the suburbs of Paris, and there the body was guarded two nights with great quantities of lights; and on the following Tuesday, the devout services having been read, there marched before the body processions with the crosses of all the churches and all the monasteries of Paris, the whole University in a body, the presidents and counsellors of the sovereign court of Parliament, and generally of all other courts and jurisdictions, officers and advocates, merchants and citizens, and other lesser officers of the town. All these accompanied the said body reverentially, with the very noble seigneurs and ladies aforenamed, just as they started from Blois, all keeping fine order among themselves according to their several ranks.... And thus was borne through Paris, in the order and manner above, the body of the queen to be sepulchred in the pious church of Saint-Denis of France; preceded by these processions to a cross which is not far beyond the place where the fair of Landit is held.

“And to the spot where stands the cross the reverend father in God, the abbé, and the venerable monks, with the priests of the churches and parishes of Saint-Denis, vestured in their great copes, with their crosses, came in procession, together with the peasants and the inhabitants of the said town, to receive the body of the late queen, which was then borne to the door of the church of Saint-Denis, still accompanied honourably by all the above-named very noble princes and princesses, seigneurs, dames, and damoiselles, and their train as already stated....

“And all being duly accomplished, the body of the said lady, Madame Anne, in her lifetime very noble Queen of France, Duchesse of Bretagne, and Comtesse d’Étampes, was honourably interred and sepulchred in the tomb for her prepared.

“After this, the herald-at-arms for Bretagne summoned all the princes and officers of the said lady, to wit: the chevalier of honour, the grand-master of the household, and others, each and all, to fulfil their duty towards the said body, which they did most piteously, shedding tears from their eyes. And, this done, the aforenamed king-at-arms cried three times aloud in a most piteous voice: ‘The very Christian Queen of France, Duchesse de Bretagne, our Sovereign Lady, is dead!’ And then all departed. The body remained entombed.

Tomb of Louis XII. and Anne de Bretagne

“During her life and after her death she was honoured by the titles I have before given: true mother of the poor; the comfort of noble gentlemen; the haven of ladies and damoiselles and honest girls; the refuge of learned men and those of good lives; so that speaking of her dead is only renewing the grief and regrets of all such persons, and also that of her domestic servants, whom she loved singularly. She was very religious and devout. It was she who made the foundation of the ‘Bons-Hommes’ [monastery of the order of Saint-François de Paule at Chaillot], otherwise called the Minimes; and she began to build the church of the said ‘Bons-Hommes’ near Paris, and afterwards that in Rome which is so beautiful and noble, and where, as I saw myself, they receive no monks but Frenchmen.”

There, word for word, are the splendid obsequies of this queen, without changing a word of the original, for fear of doing worse,—for I could not do better. They were just like those of our kings that I have heard and read of, and those of King Charles IX., at which I was present, and which the queen, his mother, desired to make so fine and magnificent, though the finances of France were then too short to spend much, because of the departure of the King of Poland, who with his suite had squandered and carried off a great deal [1574].

Certainly I find these two interments much alike, save for three things: one, that the burial of Queen Anne was the most superb; second, that all went so well in order and so discreetly that there was no contention of ranks, as occurred at the burial of King Charles; for his body, being about to start for Notre-Dame, the court of parliament had some pique of precedence with the nobility and the Church, claiming to stand in the place of the king and to represent him when absent, he being then out of the kingdom. [Henri III. was then King of Poland]. On which a great princess, as the world goes, who was very near to him, whom I know but will not name, went about arguing and saying: “It was no wonder if, during the lifetime of the king, seditions and troubles had been in vogue, seeing that, dead as he was, he was still able to stir up strife.” Alas! he never did it, poor prince! either dead or living. We know well who were the authors of the seditions and of our civil wars. That princess who said those words has since found reason to regret them.

The third thing is that the body of King Charles was quitted, at the church of Saint-Lazare, by the whole procession, princes, seigneurs, courts of parliament, the Church, and the citizens, and was followed and accompanied from there by none but poor M. de Strozzi, de Fumel, and myself, with two gentlemen of the bedchamber, for we were not willing to abandon our master as long as he was above ground. There were also a few archers of the guard, quite pitiable to see, in the fields. So at eight in the evening in the month of July, we started with the body and its effigy thus badly accompanied.

Reaching the cross, we found all the monks of Saint-Denis awaiting us, and the body of the king was honourably escorted, with the ceremonies of the Church, to Saint-Denis, where the great Cardinal de Lorraine received it most honourably and devoutly, as he knew well how to do.

The queen-mother was very angry that the procession did not continue to the end as she intended—save for Monsieur her son, and the King of Navarre, whom she held a prisoner. The next day, however, the latter arrived in a coach, with a very good guard, and captains of the guard with him, to be present at the solemn high service, attended by the whole procession and company as at first,—a sight very sad to see.

After dinner the court of parliament sent to tell and to command the grand almoner Amyot to go and say grace after meat for them as if for the king. To which he made answer that he should do nothing of the kind, for it was not before them he was bound to do it. They sent him two consecutive and threatening commands; which he still refused, and went and hid himself that he might answer no more. Then they swore they would not leave the table till he came; but not being able to find him, they were constrained to say grace themselves and to rise, which they did with great threats, foully abusing the said almoner, even to calling him scoundrel, and son of a butcher. I saw the whole affair; and I know what Monsieur commanded me to go and tell to M. le cardinal, asking him to pacify the matter, because they had sent commands to Monsieur to send to them, as representatives of the king, the grand almoner if he could be found. M. le cardinal went to speak to them, but he gained nothing; they standing firm on their opinion of their royal majesty and authority. I know what M. le cardinal said to me about them, telling me not to say it,—that they were perfect fools. The chief president, de Thou, was then at their head; a great senator certainly, but he had a temper. So here was another disturbance to make that princess say again that King Charles, either living or dead, on earth or under it, that body of his stirred up the world and threw it into sedition. Alas! that he could not do.

I have told this little incident, possibly more at length than I should, and I may be blamed; but I reply that I have told and put it here as it came into my fancy and memory; also that it comes in à propos; and that I cannot forget it, for it seems to me a thing that is rather remarkable.

Now, to return to our Queen Anne: we see from this fine last duty of her obsequies how beloved she was of earth and heaven; far otherwise than that proud, pompous queen, Isabella of Bavaria, wife of the late King Charles VI., who having died in Paris, her body was so despised it was put out of her palace into a little boat on the river Seine, without form of ceremony or pomp, being carried through a little postern so narrow it could hardly go through, and thus was taken to Saint-Denis to her tomb like a simple damoiselle, neither more nor less. There was also a difference between her actions and those of Queen Anne: for she brought the English into France and Paris, threw the kingdom into flames and divisions, and impoverished and ruined every one; whereas Queen Anne kept France in peace, enlarged and enriched it with her beautiful duchy and the fine property she brought with her. So one need not wonder that the king regretted her and felt such mourning that he came nigh dying in the forest of Vincennes, and clothed himself and all his Court so long in black; and those who came otherwise clothed he had them driven away; neither would he see any ambassador, no matter who he was, unless he were dressed in black. And, moreover, that old History which I have quoted, says: “When he gave his daughter to M. d’Angoulême, afterwards King François, mourning was not left off by him or his Court; and the day of the espousals in the church of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the bridegroom and bride were vestured and clothed”—so this History says—“in black cloth, honestly cut in mourning shape, for the death of the said queen, Madame Anne de Bretagne, mother of the bride, in presence of the king, her father, accompanied by the princes of the blood and noble seigneurs and prelates, princesses, dames, and damoiselles, all clothed in black cloth made in mourning shape.” That is what the book says. It was a strange austerity of mourning which should be noted, that not even on the day of the wedding was it dispensed with, to be renewed on the following day.

From this we may know how beloved, and worthy to be beloved this princess was by the king, her husband, who sometimes in his merry moods and gayety would call her “his Breton.”

If she had lived longer she would never have consented to that marriage of her daughter; it was very repugnant to her and she said so to the king, her husband, for she mortally hated Madame d’Angoulême, afterwards Regent, their tempers being quite unlike and not agreeing together; besides which, she had wished to unite her said daughter to Charles of Austria, then young, the greatest seigneur of Christendom, who was afterwards emperor. And this she wished in spite of M. d’Angoulême coming very near the Crown; but she never thought of that, or would not think of it, trusting to have more children herself, she being only thirty-seven years old when she died. In her lifetime and reign, reigned also that great and wise queen, Isabella of Castile, very accordant in manners and morals with our Queen Anne. For which reason they loved each other much and visited one another often by embassies, letters, and presents; ‘tis thus that virtue ever seeks out virtue.

King Louis was afterwards pleased to marry for the third time Marie, sister of the King of England, a very beautiful princess, young, and too young for him, so that evil came of it. But he married more from policy, to make peace with the English and to put his own kingdom at rest, than for any other reason, never being able to forget his Queen Anne. He commanded at his death that they should both be covered by the same tomb, just as we now see it in Saint-Denis, all in white marble, as beautiful and superb as never was.

Now, here I pause in my discourse and go no farther; referring the rest to books that are written of this queen better than I could write; only to content my own self have I made this discourse.

I will say one other little thing; that she was the first of our queens or princesses to form the usage of putting a belt round their arms and escutcheons, which until then were borne not inclosed, but quite loose; and the said queen was the first to put the belt.

I say no more, not having been of her time; although I protest having told only truth, having learned it, as I have said, from a book, and also from Mme. la Seneschale, my grandmother, and from Mme. de Dampierre, my aunt, a true Court register, and as clever, wise, and virtuous a lady as ever entered a Court these hundred years, and who knew well how to discourse on old things. From eight years of age she was brought up at Court, and forgot nothing; it was good to hear her talk; and I have seen our kings and queens take a singular pleasure in listening to her, for she knew all,—her own time and past times; so that people took word from her as from an oracle. King Henri III. made her lady of honour to the queen, his wife. I have here used recollections and lessons that I obtained from her, and I hope to use many more in the course of these books.

I have read the epitaph of the said queen, thus made:—

Gui Patin, satirist and jovial spirit of his time [he was born in 1601], attracted to Saint-Denis because a fair was held there, visits the abbey, the treasury, “where” he says, “there was plenty of silly stuff and rubbish,” and lastly the tombs of the kings, “where I could not keep myself from weeping to see so many monuments to the vanity of human life; tears escaped me also before the tomb of the great and good king, François I., who founded our College of Professors of the King. I must own my weakness; I kissed it, and also that of his father-in-law, Louis XII., who was the Father of his People, and the best king we have ever had in France.” Happy age! still neighbour to beliefs, when those reputed the greatest satirists had these touching naïvetés, these wholly patriotic and antique sensibilities.

Mézeray [born ten years later], in his natural, sincere and expressive diction, his clear and full narration, into which he has the art to bring speaking circumstances which animate the tale, says in relation to Louis XII. [in his “History of France”]: “When he rode through the country the good folk ran from all parts and for many days to see him, strewing the roads with flowers and foliage, and striving, as though he were a visible God, to touch his saddle with their handkerchiefs and keep them as precious relics.”

And two centuries later, Comte Rœderer, in his Memoir on Polite Society and the Hôtel de Rambouillet, printed in 1835, tells us how in his youth his mind was already busy with Louis XII., and, returning to the same interest in after years, he made him his hero of predilection and his king. In studying the history of France he thought he discovered, he says, that at the close of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth what has since been called the “French Revolution” was already consummated; that liberty rested on a free Constitution; and that Louis XII., the Father of his People, was he who had accomplished it. Bonhomie and goodness have never been denied to Louis XII., but Rœderer claims more, he claims ability and skill. The Italian wars, considered generally to have been mistakes, he excuses and justifies by showing them in the king’s mind as a means of useful national policy; he needed to obtain from Pope Alexander VI. the dissolution of his marriage with Jeanne de France, in order that he might marry Anne de Bretagne and so unite the duchy with the kingdom. Rœderer makes King Louis a type of perfection; seeming to have searched in regions far from those that are historically brilliant, far from spheres of fame and glory, into “the depths obscure,” as he says himself, “of useful government for a hero of a new species.”

More than that: he thinks he sees in the cherished wife of Louis XII., in Anne de Bretagne, the foundress of a school of polite manners and perfection for her sex. “She was,” Brantôme had said, “the most worthy and honourable queen that had ever been since Queen Blanche, mother of the King Saint-Louis.... Her Court was a noble school for ladies; she had them taught and brought up wisely; and all, taking pattern by her, made themselves wise and virtuous.” Rœderer takes these words of Brantôme and, giving them their strict meaning, draws therefrom a series of consequences: just as François I. had, in many respects, overthrown the political state of things established by Louis XII., so, he believes, had the women beloved of François overturned that honourable condition of society established by Anne de Bretagne. Starting from that epoch he sees, as it were, a constant struggle between two sorts of rival and incompatible societies: between the decent and ingenuous society of which Anne de Bretagne had given the idea, and the licentious society of which the mistresses of the king, women like the Duchesse d’Étampes and Diane de Poitiers, procured the triumph. These two societies, to his mind, never ceased to co-exist during the sixteenth century; on the one hand was an emulation of virtue and merit on the part of the noble heiresses, alas, too eclipsed, of Anne de Bretagne, on the other an emulation with high bidding of gallantry, by the giddy pupils of the school of François I. To Rœderer the Hôtel de Rambouillet, that perfected salon, founded towards the beginning of the seventeenth century, is only a tardy return to the traditions of Anne de Bretagne, the triumph of merit, virtue, and polite manners over the license to which all the kings, from François I., including Henri IV., had paid tribute.