STORIES OF THE LIFEBOAT

STORIES

OF

THE LIFEBOAT

BY

FRANK MUNDELL

AUTHOR OF "STORIES OF THE VICTORIA CROSS"

"INTO THE UNKNOWN WEST" ETC

FOURTH EDITION

LONDON:

THE SUNDAY SCHOOL UNION

57 AND 59 LUDGATE HILL, E.C.

VOLUMES IN THIS SERIES.

BY FRANK MUNDELL,

AUTHOR OF "THE HEROINES' LIBRARY."

Crown 8vo, cloth boards, 1s. 6d. each.

WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

STORIES OF THE FAR WEST.

STORIES OF THE COAL MINE.

STORIES OF THE ROYAL HUMANE SOCIETY.

STORIES OF THE FIRE BRIGADE.

STORIES OF NORTH POLE ADVENTURE.

STORIES OF THE VICTORIA CROSS.

STORIES OF THE LIFEBOAT.

Of all Booksellers.

LONDON:

THE SUNDAY SCHOOL UNION,

57 AND 59 LUDGATE HILL, E.C.

PREFACE

In sending forth this little work to the public, I desire to acknowledge my obligations to the following:--The Royal National Lifeboat Institution for the valuable matter placed at my disposal, also for the use of the illustrations on pages 20 and 21; to Mr. Clement Scott and the proprietors of Punch for permission to use the poem, "The Warriors of the Sea"; to the proprietors of The Star for the poem, "The Stranding of the Eider"; and to the proprietors of the Kent Argus for so freely granting access to the files of their journal. Lastly, my thanks are due to the publishers--at whose suggestion the work was undertaken--for the generous manner in which they have illustrated the book.

F. M.

LONDON, September, 1894.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

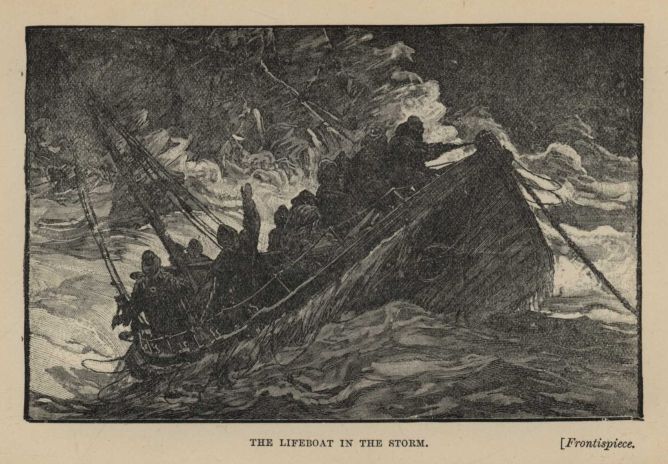

THE LIFEBOAT IN THE STORM . . . . . . Frontispiece

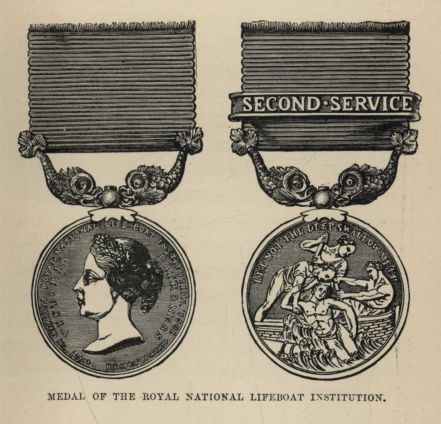

MEDAL OF THE ROYAL NATIONAL LIFEBOAT INSTITUTION

SURVIVORS OF THE "INDIAN CHIEF"

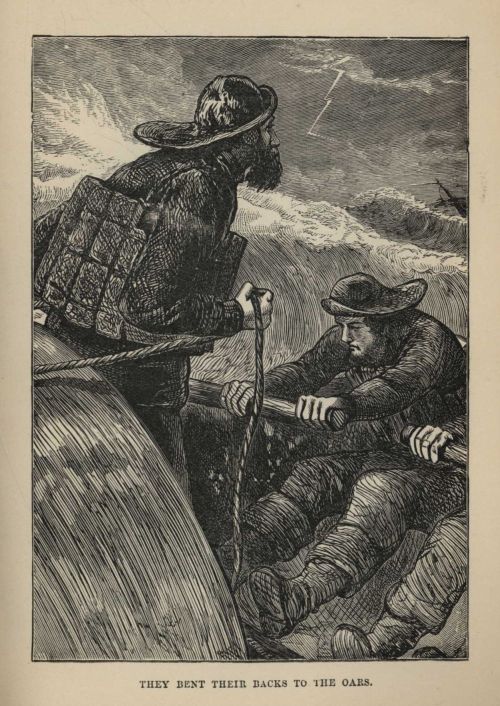

THEY BENT THEIR BACKS TO THE OARS

The Lifeboat! oh, the Lifeboat!We all have known so long,A refuge for the feeble,The glory of the strong.Twice thirty years have vanished,Since first upon the waveShe housed the drowning mariner,And snatched him from the grave,The voices of the rescued,Their numbers may be read,The tears of speechless feelingOur wives and children shed;The memories of mercyIn man's extremest need.All for the dear old LifeboatUniting seem to plead.

STORIES

of

THE LIFEBOAT

CHAPTER I.

MAN THE LIFEBOAT!

o Lionel Lukin, a coachbuilder of Long Acre, London, belongs the honour of inventing the lifeboat. As early as the year 1784 he designed and fitted a boat, which was intended "to save the lives of mariners wrecked on the coast." It had a projecting gunwale of cork, and air-tight lockers or enclosures under the seats. These gave the boat great buoyancy, but it was liable to be disabled by having the sides stove in. Though Lukin was encouraged in his efforts by the Prince of Wales--afterwards George the Fourth--his invention did not meet with the approval of those in power at the Admiralty, and Lukin's only lifeboat which came into use was a coble that he fitted up for the Rev. Dr. Shairp of Bamborough. For many years this was the only lifeboat on the coast, and it is said to have saved many lives.

o Lionel Lukin, a coachbuilder of Long Acre, London, belongs the honour of inventing the lifeboat. As early as the year 1784 he designed and fitted a boat, which was intended "to save the lives of mariners wrecked on the coast." It had a projecting gunwale of cork, and air-tight lockers or enclosures under the seats. These gave the boat great buoyancy, but it was liable to be disabled by having the sides stove in. Though Lukin was encouraged in his efforts by the Prince of Wales--afterwards George the Fourth--his invention did not meet with the approval of those in power at the Admiralty, and Lukin's only lifeboat which came into use was a coble that he fitted up for the Rev. Dr. Shairp of Bamborough. For many years this was the only lifeboat on the coast, and it is said to have saved many lives.

In the churchyard of Hythe, in Kent, the following inscription may be read on the tombstone, which marks the last resting-place of the "Father of the Lifeboat":--

"This LIONEL LUKIN

was the first who built a lifeboat, and was the

original inventor of that quality of safety, by

which many lives and much property have been

preserved from shipwreck, and he obtained for

it the King's Patent in the year 1785."

The honour of having been the first inventor of the lifeboat is also claimed by two other men. In the parish church of St. Hilda, South Shields, there is a stone "Sacred to the Memory of William Wouldhave, who died September 28, 1821, aged 70 years, Clerk of this Church, and Inventor of that invaluable blessing to mankind, the Lifeboat." Another similar record tells us that "Mr. Henry Greathead, a shrewd boatbuilder at South Shields, has very generally been credited with designing and building the first lifeboat, about the year 1789." As we have seen, Lukin had received the king's patent for his invention four years before Greathead brought forward his plan. This proves conclusively that the proud distinction belongs by right to Lionel Lukin.

In September 1789 a terrible wreck took place at the mouth of the Tyne. The ship Adventure of Newcastle went aground on the Herd Sands, within three hundred yards of the shore. The crew took to the rigging, where they remained till, benumbed by cold and exhaustion, they dropped one by one into the midst of the tremendous breakers, and were drowned in the presence of thousands of spectators, who were powerless to render them any assistance.

Deeply impressed by this melancholy catastrophe, the gentlemen of South Shields called a meeting, and offered prizes for the best model of a lifeboat "calculated to brave the dangers of the sea, particularly of broken water." From the many plans sent in, those of William Wouldhave and Henry Greathead were selected, and after due consideration the prize was awarded to "the shrewd boatbuilder at South Shields." He was instructed to build a boat on his own plan with several of Wouldhave's ideas introduced. This boat had five thwarts, or seats for rowers, double banked, to be manned by ten oars. It was lined with cork, and had a cork fender or pad outside, 16 inches deep. The chief point about Greathead's invention was that the keel was curved instead of being straight. This circumstance, simple as it appears, caused him to be regarded as the inventor of the first practicable lifeboat, for experience has proved that a boat with a curved keel is much more easily launched and beached than one with a straight keel.

Lifeboats on this plan were afterwards placed on different parts of the coast, and were the means of saving altogether some hundreds of lives. By the end of the year 1803 Greathead had built no fewer than thirty-one lifeboats, eight of which were sent to foreign countries. He applied to Parliament for a national reward, and received the sum of £1200. The Trinity House and Lloyd's each gave him £105. From the Society of Arts he received a gold medal and fifty guineas, and a diamond ring from the Emperor of Russia.

The attention thus drawn to the needs of the shipwrecked mariner might have been expected to be productive of good results, but, unfortunately, it was not so. The chief reason for this apathy is probably to be found in the fact that, though the lifeboats had done much good work, several serious disasters had befallen them, which caused many people to regard the remedy as worse than the disease. Of this there was a deplorable instance in 1810, when one of Greathead's lifeboats, manned by fifteen men, went out to the rescue of some fishermen who had been caught in a gale off Tynemouth. They succeeded in taking the men on board, but on nearing the shore a huge wave swept the lifeboat on to a reef of rocks, where it was smashed to atoms. Thirty-four poor fellows--the rescued and the rescuers--were drowned.

It was not until twelve years after this that the subject of the preservation of life from shipwreck on our coast was successfully taken up. Sir William Hillary, himself a lifeboat hero, published a striking appeal to the nation on behalf of the perishing mariner, and as the result of his exertions the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck was established in 1824. This Society still exists under the well-known name of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. It commenced its splendid career with about £10,000, and in its first year built and stationed a dozen lifeboats on different parts of the coast.

For many years the Society did good work, though sadly crippled for want of funds. In 1850 the Duke of Northumberland offered the sum of one hundred guineas for the best model of a lifeboat. Not only from all parts of Great Britain, but also from America, France, Holland, and Germany, plans and models were sent in to the number of two hundred and eighty. After six months' examination, the prize was awarded to James Beeching of Great Yarmouth, and his was the first self-righting lifeboat ever built. The committee were not altogether satisfied with Beeching's boat, and Mr. Peake, of Her Majesty's Dockyard at Woolwich, was instructed to design a boat embodying all the best features in the plans which had been sent in. This was accordingly done, and his model, gradually improved as time went on, was adopted by the Institution for their boats.

The lifeboats now in use measure from 30 to 40 feet in length, and 8 in breadth. Buoyancy is obtained by air-chambers at the ends and on both sides. The two large air-chambers at the stem and stern, together with a heavy iron keel, make the boat self-righting, so that should she be upset she cannot remain bottom up. Between the floor and the outer skin of the boat there is a space stuffed with cork and light hard wood, so that even if a hole was made in the outer covering the boat would not sink. To insure the safety of the crew in the event of a sea being shipped, the floor is pierced with holes, into which are placed tubes communicating with the sea, and valves so arranged that the water cannot come up into the boat, but should she ship a sea the valves open downwards and drain off the water. A new departure in lifeboat construction was made in 1890, when a steam lifeboat, named the Duke of Northumberland, was launched. Since then it has saved many lives, and has proved itself to be a thoroughly good sea boat. While an ordinary lifeboat is obliged to beat about and lose valuable time, the steam lifeboat goes straight to its mark even in the roughest sea, so that probably before long the use of steam in combating the storm will become general.

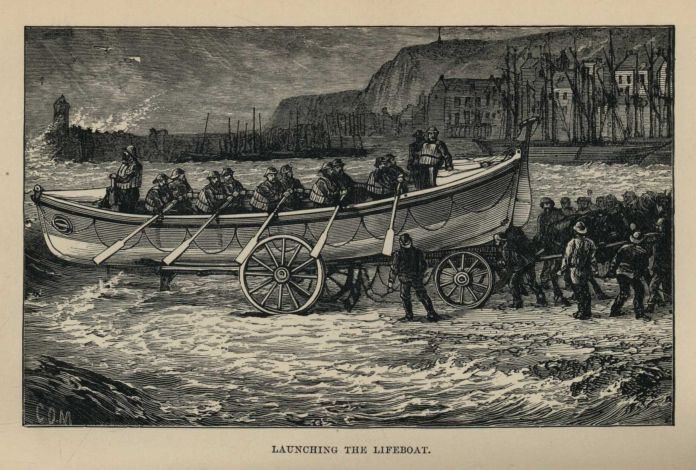

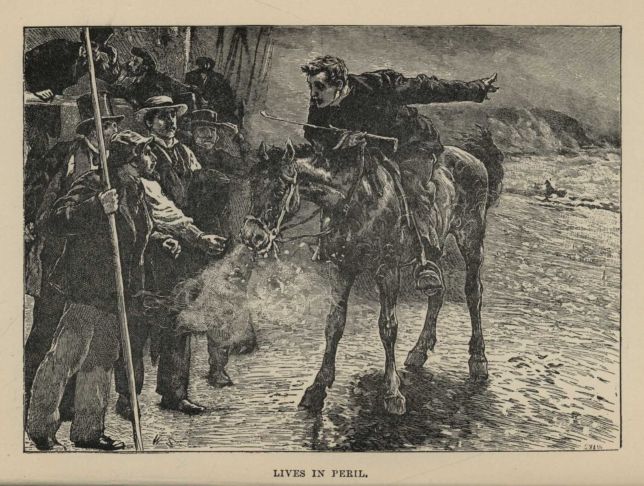

Nearly every lifeboat is provided with a transporting carriage on which she constantly stands ready to be launched at a moment's notice. By means of this carriage, which is simply a framework on four wheels, the lifeboat can be used along a greater extent of coast than would otherwise be possible. It is quicker and less laborious to convey the boat by land to the point nearest the wreck, than to proceed by sea, perhaps in the teeth of a furious gale. In addition to this a carriage is of great use in launching a boat from the beach, and there are instances on record when, but for the carriage, it would have been impossible for the lifeboat to leave the shore on account of the high surf.

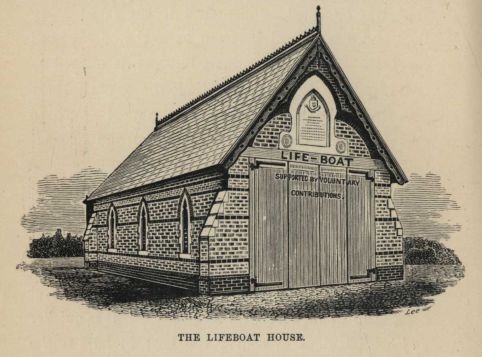

The boats belonging to the National Lifeboat Institution are kept in roomy and substantial boathouses under lock and key. The coxswain has full charge of the boat, both when afloat and ashore. He receives a salary of £8 a year, and his assistant £2 a year. The crew of the lifeboat consists of a bowman and as many men as the boat pulls oars. On every occasion of going afloat to save life, each man receives ten shillings, if by day; and £1, if by night. This money is paid to the men out of the funds of the Institution, whether they have been successful or not. During the winter months these payments are now increased by one half.

The cost of a boat with its equipment of stores--cork lifebelts, anchors, lines, lifebuoys, lanterns, and other articles--is upwards of £700, and the expense of building the boathouse amounts to £300, while the cost of maintaining it is £70 a year. The Institution also awards medals to those who have distinguished themselves by their bravery in saving life from shipwreck. One side of this medal is adorned with a bust of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, who is the patroness of the Institution. The other side represents three sailors in a lifeboat, one of whom is rescuing an exhausted mariner from the waves with the inscription, "Let not the deep swallow me up." Additional displays of heroism are rewarded by clasps bearing the number of the service.

"When we think of the vast extent of our dangerous coasts, and of our immense interest in shipping, averaging arrivals and departures of some 600,000 vessels a year; when we think of the number of lives engaged, some 200,000 men and boys, besides untold thousands of passengers, and goods amounting to many millions of pounds in value, the immense importance of the lifeboat service cannot be over-estimated." Well may we then, "when the storm howls loudest," pray that God will bless that noble Society, and the band of humble heroes who man the three hundred lifeboats stationed around the coasts of the British Isles.

CHAPTER II.

LIFEBOAT DISASTERS.

e have already referred to the numerous disasters which did so much to retard the progress of the lifeboat movement. Now let us see how these disasters were caused. The early lifeboats, though provided with a great amount of buoyancy, had no means of freeing themselves of water, or of self-righting if upset, and the absence of these qualities caused the loss of many lives.

e have already referred to the numerous disasters which did so much to retard the progress of the lifeboat movement. Now let us see how these disasters were caused. The early lifeboats, though provided with a great amount of buoyancy, had no means of freeing themselves of water, or of self-righting if upset, and the absence of these qualities caused the loss of many lives.

Sir William Hillary, who may be regarded as the founder of the National Lifeboat Institution, distinguished himself, while living on the Isle of Man, by his bravery in rescuing shipwrecked crews. It was estimated that in twenty-five years upwards of a hundred and forty vessels were wrecked on the island, and a hundred and seventy lives were lost; while the destruction of property was put down at a quarter of a million. In 1825, when the steamer City of Glasgow went ashore in Douglas Bay, Sir William Hillary went out in the lifeboat and assisted in taking sixty-two people off the wreck. In the same year the brig Leopard went ashore, and Sir William again went to the rescue and saved eleven lives. While he lived on the island, hardly a year passed without him adding fresh laurels to his name, and never did knight of old rush into the fray with greater ardour than did this gallant knight of the nineteenth century to the rescue of those in peril on the sea. His greatest triumph, however, was on the 20th of November 1830, when the mail steamer St. George stranded on St. Mary's Rock and became a total wreck. The whole crew, twenty-two in number, were rescued by the lifeboat. On this occasion he was washed overboard among the wreck, and it was with the greatest difficulty that he was saved, having had six of his ribs broken.

In 1843 the lifeboat stationed at Robin Hood Bay went out to the assistance of the Ann of London. Without mishap the wreck was reached, and the work of rescue was begun. Several of the shipwrecked men jumped into the boat just as a great wave struck her, and she upset. Some of the crew managed to scramble on to the bottom of the upturned boat and clung to the keel for their lives.

The accident had been witnessed by the men on the beach, and five of them immediately put out to the rescue. They had hardly left the shore when an enormous sea swept down upon them, causing the boat to turn a double somersault, and drowning two of the crew. Altogether twelve men lost their lives on this occasion. Those who were saved floated ashore on the bottom of the lifeboat.

The Herd Sand, memorable as the scene of the wreck of the Adventure, witnessed a lamentable disaster in 1849, when the Betsy of Littlehampton went aground. The South Shields lifeboat, manned by twenty-four experienced pilots, went out to the rescue. While preparing to take the crew on board, she was struck by a heavy sea, and before she could recover herself, a second mighty wave threw her over. Twenty out of the twenty-four of her crew were drowned. The remainder and the crew of the Betsy were rescued by two other lifeboats, which put off from the shore immediately upon witnessing what had happened.

The advantages of the self-righting and self-emptying boats may be best judged from the fact, that since their introduction in 1852, as many as seventy thousand men have gone out in these boats on service, and of these only seventy-nine have nobly perished in their gallant attempts to rescue others. This is equal to a loss of one man in every eight hundred and eighty.

During the terrible storm which swept down upon our coast in 1864, the steamer Stanley of Aberdeen was wrecked while trying to enter the Tyne. The Constance lifeboat was launched from Tynemouth, and proceeded to the scene of the wreck. The night was as dark as pitch, and from the moment that the boat started, nothing was to be seen but the white flash of the sea, which broke over the boat and drenched the crew. As quickly as she freed herself of water, she was buried again and again. At length the wreck was reached, and while the men were waiting for a rope to be passed to them, a gigantic wave burst over the Stanley and buried the lifeboat. Every oar was snapped off at the gunwale, and the outer ends were swept away, leaving nothing but the handles. When the men made a grasp for the spare oars they only got two--the remainder had been washed overboard.

It was almost impossible to work the Constance with the rudder and two oars, and while she was in this disabled condition a second wave burst upon her. Four of the crew either jumped or were thrown out of the boat, and vanished from sight. A third mighty billow swept the lifeboat away from the wreck, and it was with the utmost difficulty that she was brought to land. Two of the men, who had been washed out of the boat, reached the shore in safety, having been kept afloat by their lifebelts. The other two were drowned.

Speaking of the attempted rescue, the coxswain of the Constance said: "Although this misfortune has befallen us, it has given fresh vigour to the crew of the lifeboat. Every man here is ready, should he be called on again, to act a similar part."

Thirty-five of those on board the Stanley, out of a total number of sixty persons, were afterwards saved by means of ropes from the shore.

One of the most heartrending disasters, which have befallen the modern lifeboat, happened on the night of the 9th of December 1886. The lifeboats at Southport and St. Anne's went out in a furious gale to rescue the crew of a German vessel named the Mexico. Both were capsized, and twenty-seven out of the twenty-nine who manned them were drowned. It was afterwards found out that the Southport boat succeeded in making the wreck, and was about to let down her anchor when she was capsized by a heavy sea. Contrary to all expectations the boat did not right, being probably prevented from doing so by the weight of the anchor which went overboard when the boat upset.

What happened to the St. Anne's lifeboat can never be known, for not one of her crew was saved to tell the tale. It is supposed that she met with some accident while crossing a sandbank, for, shortly after she had been launched, signals of distress were observed in that quarter. Next morning the boat was found on the beach bottom up with three of her crew hanging to the thwarts--dead.

Such is the fate that even to-day overhangs the lifeboatman on the uncertain sea. Yet he is ever ready on the first signal of distress to imperil his life to rescue the stranger and the foreigner from a watery grave. "First come, first in," is the rule, and to see the gallant lifeboatmen rushing at the top of their speed in the direction of the boathouse, one would imagine that they were hurrying to some grand entertainment instead of into the very jaws of death. It is not for money that they thus risk their lives, as the pay they receive is very small for the work they have to perform. They are indeed heroes, in the truest sense of the word, and give to the world a glorious example of duty well and nobly done.

CHAPTER III.

THE WARRIORS OF THE SEA.

[On the night of the 9th of December 1886, the Lytham, Southport, and St. Anne's lifeboats put out to rescue the crew of the ship Mexico, which had run aground off the coast of Lancashire. The Southport and St. Anne's boats were lost, but the Lytham boat effected the rescue in safety.]

Up goes the Lytham signal!St. Anne's has summoned hands!Knee deep in surf the lifeboat's launchedAbreast of Southport sands!Half deafened by the screaming wind,Half blinded by the rain,Three crews await their coxswains,And face the hurricane!The stakes are death or duty!No man has answered "No"!Lives must be saved out yonderOn the doomed ship Mexico!Did ever night look blacker?Did sea so hiss before?Did ever women's voices wailMore piteous on the shore?Out from three ports of LancashireThat night went lifeboats three,To fight a splendid battle, mannedBy "Warriors of the Sea."Along the sands of SouthportBrave women held their breath,For they knew that those who loved themWere fighting hard with death;A cheer went out from Lytham!The tempest tossed it back,As the gallant lads of LancashireBent to the waves' attack;And girls who dwelt about St. Anne's,With faces white with fright,Prayed God would still the tempestThat dark December night.Sons, husbands, lovers, brothers,They'd given up their all,These noble English womenHeartsick at duty's call;But not a cheer, or tear, or prayer,From those who bent the knee,Came out across the waves to nerveThose Warriors of the Sea.Three boats went out from Lancashire,But one came back to tellThe story of that hurricane,The tale of ocean's hell!All safely reached the Mexico,Their trysting-place to keep;For one there was the rescue,The others in the deepFell in the arms of victoryDropped to their lonely grave,Their passing bell the tempest,Their requiem the wave!They clung to life like sailors,They fell to death like men,--Where, in our roll of heroes,When in our story, when,Have Englishmen been braver,Or fought more loyallyWith death that comes by dutyTo the Warriors of the Sea?One boat came back to LythamIts noble duty done;But at St. Anne's and SouthportThe prize of death was won!Won by those gallant fellowsWho went men's lives to save,And died there crowned with glory,Enthroned upon the wave!Within a rope's throw off the wreckThe English sailors fell,A blessing on their faithful lips,When ocean rang their knell.Weep not for them, dear women!Cease wringing of your hands!Go out to meet your heroesAcross the Southport sands!Grim death for them is stingless!The grave has victory!Cross oars and bear them nobly home,Brave Warriors of the Sea!When in dark nights of winterFierce storms of wind and rainHowl round the cosy homestead,And lash the window-pane--When over hill and tree topWe hear the tempests roar,And hurricanes go sweeping onFrom valley to the shore--When nature seems to stand at bay,And silent terror comes,And those we love on earth the bestAre gathered in our homes,--Think of the sailors round the coast,Who, braving sleet or snow,Leave sweethearts, wives, and little onesWhen duty bids them go!Think of our sea-girt island!A harbour, where aloneNo Englishman to save a lifeHas failed to risk his own.Then when the storm howls loudest,Pray of your charityThat God will bless the lifeboatAnd the Warriors of the Sea!

CLEMENT SCOTT.

(By permission of the Author, and the Proprietors of "Punch.")

CHAPTER IV.

THE GOODWIN SANDS.

bout six miles off the east coast of Kent there is a sandbank known as the Goodwin Sands, extending for a distance of ten miles, between the North Foreland and the South Foreland. No part of our coast is so much dreaded by the mariner, and from early times it has been the scene of many terrible disasters. As Shakespeare says, it is "a very dangerous flat, and fatal, where the carcasses of many a tall ship lie buried."

bout six miles off the east coast of Kent there is a sandbank known as the Goodwin Sands, extending for a distance of ten miles, between the North Foreland and the South Foreland. No part of our coast is so much dreaded by the mariner, and from early times it has been the scene of many terrible disasters. As Shakespeare says, it is "a very dangerous flat, and fatal, where the carcasses of many a tall ship lie buried."

It is said that the site of the Goodwin Sands was at one time occupied by a low fertile island, called Lomea, and here lived the famous Earl Godwin. After the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror took possession of these estates, and bestowed them, as was the custom in those days, upon the Abbey of St. Augustine at Canterbury. The abbot, however, seems to have had little regard for the property, and he used the funds with which it should have been maintained in building a steeple at Tenterden, an inland town near the south-west border of Kent. The wall, which defended the island from the sea, being thus allowed to fall into a state of decay, was unable to withstand the storm that, in 1099, burst over Northern Europe, and the waves rushed in and overwhelmed the island. This gave rise to the saying, "Tenterden steeple was the cause of the Goodwin Sands."

At high tide the whole of this dangerous shoal is covered by the sea to the depth of several feet; but at low water large stretches of sand are left hard and dry. At such a time it is perfectly safe for anyone to walk along this island desert for miles, and cricket is known to have been played in some places. Here and there the surface is broken by large hollows filled with water. Should the visitor, however, attempt to wade to the opposite side, he is glad to beat a hasty retreat, as he finds himself sinking with alarming rapidity into the sand, which the action of the water has rendered soft.

Between the Goodwins and the coast of Kent is the wide and secure roadstead called the Downs. Here, when easterly or south-easterly winds are blowing, ships may ride safely at anchor; but when a storm comes from the west, vessels are no longer secure, and frequently break from their moorings and become total wrecks on the sands. To warn mariners of their danger, four lightships are anchored on different parts of the sands. Each is provided with powerful lanterns, the light of which can be seen, in clear weather, ten miles off. During foggy weather, fog sirens are sounded and gongs are beaten to tell the sailor of his whereabouts. Notwithstanding all these precautions, the number of vessels stranded on the Goodwins every year is appalling; and but for the heroic efforts of the Kentish lifeboatmen, the loss of life would be still more terrible.

The work done by the boatmen all around our coast cannot be too highly estimated, but a special word of praise is due to the Ramsgate men. They have, without doubt, saved more lives than the men of any other port in the kingdom. Being stationed so near to the deadly Goodwins has given them greater opportunities for service, and they have also a steam tug in attendance on the lifeboat to tow her to the scene of disaster. So that, no matter what is the direction of the wind, they can always go out.

Recently, I went down to this "metropolis of the lifeboat service," for the express purpose of interviewing one of those warriors of the sea. The place was crowded with holiday-makers, and the harbour presented a busy scene. Four fine large yachts were getting their passengers on board for "a two-hours' sail." A yellow-painted tug was puffing to and fro, towing coasting vessels and luggers out of the harbour, and threatening to run down several small boats which repeatedly tried to cross her bows. At some distance from where I was standing lay the lifeboat Bradford, motionless and neglected, and looking strangely out of place in such smooth water. How the sight of the boat recalled to my mind all that I had ever read or heard of the perils of "those who go down to the sea in ships"--the storm, the wreck, the dark winter night, the midnight summons to man the lifeboat, the struggle for a place, the sufferings from cold, the happy return with the crew all saved,--these and other similar incidents seemed to pass before my eyes like a panorama--the centre object ever being the blue-painted Bradford.

"Have a boat this morning, sir?" said a thick muffled voice quite close to me. Turning round I saw a little, old man with a bronzed, weather-beaten face.

"Not this morning, thank you," I replied; "unless you will let me have the lifeboat for an hour or two."

He shook his head and turned away. Then it suddenly seemed to strike him that possibly I did not know the uses of the lifeboat, and would be none the worse if I received a little information on the subject.

"The lifeboat's not a pleasure boat, sir," he said, "and never goes out unless in cases of distress. I reckon if you went out in lifeboat weather once, you'd never want to go again."

"I suppose you have heavy seas here at times?" I remarked.

"Nobody that hasn't seen it has any idea of the water here, and the wind is strong enough to blow a man off his feet. Great waves come over the end of the pier, and carry everything, that's not lashed, into the sea. One day, a few winters ago, a perfect wall of water thundered down on the pier and twisted that big iron crane you see out there as if it had been made of wire. The water often comes down the chimneys of the watch-house at the end of the pier and puts out the fires; and every time the sea comes over, the whole building shakes, as if an earthquake was going on. What's worse almost than the sea is the terrible cold. Why, sir, I've seen this pier a mass of ice from end to end, and the masts and shrouds of the vessels moored alongside also covered with ice; so that a rope, which was no thicker than your finger, would look as big as a man's arm. As you know, sir, it's a hard frost that freezes salt water, and yet the lifeboat goes out in weather like that."

"It's a wonder to me," I said, "that under such circumstances the boat is manned."

"No difficulty in that, sir; there are always more men wanting to go out than there's room for. Now suppose a gun was fired at this minute from any of the lightships to tell us that assistance was needed you would see men running from every quarter, all eager for a place. I know how they would scramble across those boats, for I've seen them, and I've done it myself. Many a time have I jumped out of my warm bed in the middle of a winter night when a gun has fired, and rushed down to the harbour with my clothes under my arm; even then I've often been too late."

"What do you consider to be the best piece of service the Bradford has done?" was my next question.

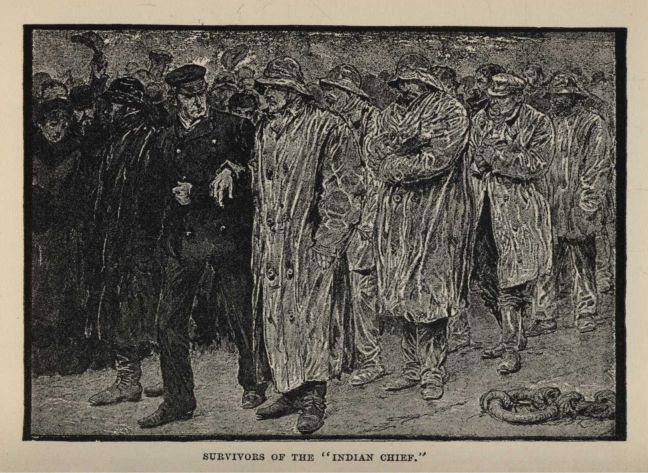

"The rescue of the survivors of the Indian Chief in the beginning of 1881. The men were out for over twenty-four hours in a terrible sea and dreadful cold. I was, unfortunately, away piloting when they started, but returned in time to see them come in. Though I knew all the boatmen well, I could not recognise a single one, the cold had so altered their faces, and the salt water had made their hair as white as wool. I can never forget it. Fish, the coxswain, received a gold medal from the Institution. There was a song made about the rescue, and us Ramsgate boatmen used to sing it. When the coxswain gave up his post, about three years ago, he got a gold second service clasp, the first ever given by the Institution. In twenty-six years he was out in the lifeboat on service nearly four hundred times, and helped to save about nine hundred lives. That's the third Bradford we've had here. The first was presented by the town of Bradford in Yorkshire, the sum for her equipment being collected in the Exchange there in an hour. That's how she got her name, and it's been kept up ever since.

"It's no joke, I can tell you," he continued, "being out in the lifeboat. In a ship you can walk about and do something to keep yourself warm, but in the boat you've got to sit still and hold on to the thwart if you don't want to be washed overboard. Like enough you get wet to the skin before you start, and each wave that breaks over the boat seems to freeze the very blood in your veins. Then, when you reach the wreck, it is low tide, and there you've got to wait till the water rises, for in some places the sands stand as high as seven feet out of the sea when the tide is down. Then, when the lifeboat gets alongside the wreck, every man requires to have his wits about him, watching for big waves, keeping clear of the wreckage, and getting the men on board. Many a time have I gone home, after being out for six or eight hours, and taken off my waterproof, and it has stood upright on the floor as if it had been made of tin. Perfectly true, sir, it was frozen. In a day or two we forget all about the hardships we have suffered, and are as ready as ever to go out when the summons comes. We never stop to ask whether the shipwrecked men are Germans, Frenchmen, or Italians. They must be saved, and we are the men to do it. We get used to the danger in time, and think very little about it."

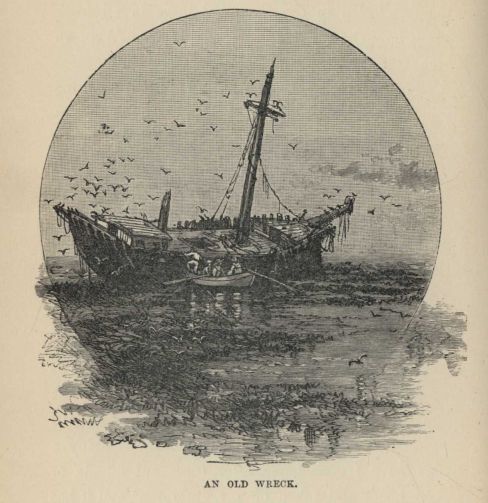

We talked for some time longer about the treacherous nature of the Goodwin Sands, and he told me that vessels are sometimes swallowed up in a few days after they are wrecked, but occasionally they remain visible for a longer period. One large iron vessel, laden with grain, which went ashore nearly four years ago is still standing, and in calm weather the tops of her iron masts may be seen sticking out of the water.

My informant was now wanted to take charge of a party of ladies who were going out for a row, so I said "Good-bye," and came away deeply impressed with the simple heroism of the lifeboatmen, of whom this man is but a type.

CHAPTER V.

THE BOATMEN OF THE DOWNS.

There's fury in the tempest,And there's madness in the waves;The lightning snake coils round the foam,The headlong thunder raves;Yet a boat is on the waters,Filled with Britain's daring sons,Who pull like lions out to sea,And count the minute guns.'Tis Mercy calls them to the work--A ship is in distress!Away they speed with timely helpThat many a heart shall bless:And braver deeds than ever turnedThe fate of kings and crownsAre done for England's glory,By her Boatmen of the Downs.We thank the friend who gives us aidUpon the quiet land;We love him for his kindly word,And prize his helping hand;But louder praise shall dwell aroundThe gallant ones who go,In face of death, to seek and saveThe stranger or the foe.A boat is on the waters--When the very sea-birds hide:'Tis noble blood must fill the pulseThat's calm in such a tide!And England, rich in recordsOf her princes, kings, and crowns,May tell still prouder storiesOf her Boatmen of the Downs.ELIZA COOK.

CHAPTER VI.

A GOOD NIGHT'S WORK.

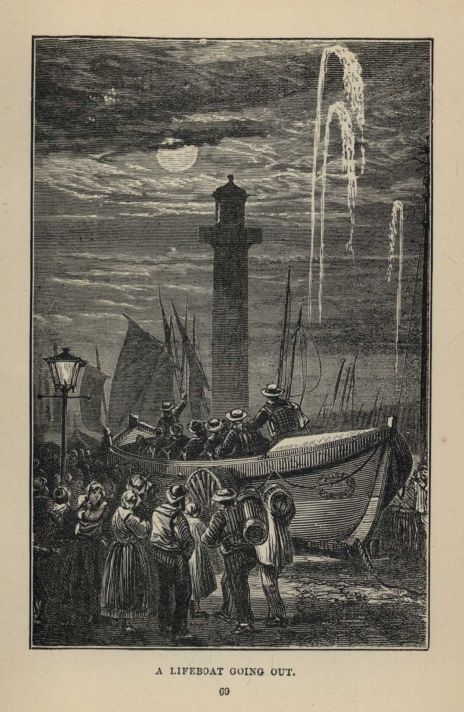

bout a quarter past eight one wintry night, a telegram was received at Ramsgate to say that the lightships west of Margate were sending up rockets and firing guns. Owing to the rough sea and strong wind, the Margate lifeboat had been unable to leave the beach, so the coxswain decided to send news of the disaster to Ramsgate, for he knew that the lifeboat there was able, by the help of the tug, to go out in any weather.

bout a quarter past eight one wintry night, a telegram was received at Ramsgate to say that the lightships west of Margate were sending up rockets and firing guns. Owing to the rough sea and strong wind, the Margate lifeboat had been unable to leave the beach, so the coxswain decided to send news of the disaster to Ramsgate, for he knew that the lifeboat there was able, by the help of the tug, to go out in any weather.

The appeal was not made in vain, and in an astonishingly short space of time the tug and lifeboat were on their way to the Goodwins. For a long time they were unable to find out the position of the wreck, and had begun to fear that they had arrived too late, when suddenly the flare of a tar-barrel lighted up the gloom and showed them a large ship hard and fast upon the sands. The water lashed round her in tremendous surges, and every wave seemed to make her tremble from stem to stern. The boatmen at once prepared for action. The tow rope was cast off, the sail hoisted, and the lifeboat plunged quickly through the broken water.

The shipwrecked people saw her coming, and raised a joyful shout. For hours they had been expecting to meet their awful fate, as each wave rolled towards the ship, and they had prepared for death; but when they saw help so near, the love of life was once more roused within them, and they watched the boat with frantic eagerness. The sail was lowered, the anchor thrown overboard, and the cable was slacked down towards the vessel. Unfortunately, the men had miscalculated the distance, and when all the rope was run out, the boat was not within 60 feet of the wreck. Slowly and laboriously the cable had to be hauled in before another attempt could be made to get alongside. The anchor had taken such a firm hold that it required the utmost exertions of the men to raise it, but at last they succeeded. They then sailed closer to the ship, and heaved the anchor overboard again. This time they had judged the distance correctly, and after they had secured a rope from the bow and another from the stern of the ship they were ready to begin work.

The wrecked vessel was the Fusilier, bound from London to Australia with emigrants. She had on board more than a hundred passengers, sixty of whom were women and children. As soon as the lifeboat got near enough, the captain called out to the men in the boat, "How many can you carry?" They replied that they had a steam tug waiting not far off, and said that they would take the passengers and crew off in parties to her. As the boat rose on the crest of a wave, two of the brave fellows caught the ship's ropes and climbed on board. "Who are you?" shouted the captain as they jumped down on to the deck among the excited passengers. "Two men from the life-boat," and at these words the men and women crowded round them, all eager to seize them by the hand, some even clinging to them in the madness of their terror. For a few moments there was a scene of wild excitement on deck, and it took all the authority of the captain to restore order and quietness.

It was then arranged that the women and children should be saved first. It was indeed a task of no little difficulty, for the lifeboat was pitching and tossing in a most terrible manner. At one time she was driven right away from the ship, then back again she came threatening to dash herself to pieces against the side of the vessel, then almost at the same instant she rose on the top of a wave nearly to the level of the ship's deck.

The first woman was brought to the side, but the moment she saw the frightful swirl of waters she shrank back and declared she would rather perish than make the attempt. There was no time to waste on words. She was taken up and handed bodily to two men suspended by ropes over the vessel's side. The boat rose on a wave, and the men stood ready to catch her. At a shout from them, those who were holding the woman let go, but in her fear she clung to the arm of one of the men. In another moment she would have dropped into the sea had not a boatman caught hold of her heel and pulled her into the boat. So one after another were taken off the wreck, and soon the boat was filled. Just as the ropes were being cast off, a man rushed up to the gangway and handed a bundle to one of the sailors. Thinking that it was only a blanket which the man intended for his wife in the boat, he shouted out, "Here, catch this!" and tossed it to one of the men. Fortunately, he succeeded in catching it, and was astonished to hear a baby cry. The next instant it was snatched from his hand by the mother.

At length the anchor was weighed, the sail hoisted, and the lifeboat headed for the tug. A faint cheer was raised by the remaining passengers, who watched her anxiously as she made her way, half buried in spray, through the sea. As is often the case with those rescued from shipwreck, the emigrants thought they were safer on the wreck than in the lifeboat, and as the huge seas swept over them, they feared that they had only been saved from death in one form to meet it in another.

Soon, however, their hearts were gladdened by the sight of the tug's lights shining over the water, and in a few minutes the boat was alongside. Hastily, yet tenderly, the women were dragged on board the tug. Every moment was precious for the sake of those left behind. One woman wanted to get back to the boat to look for her child, but her voice was drowned in the roar of the storm, and she was taken below. Then, again, the bundle is tossed through the air and caught, and just as it was about to be thrown into a corner, some one shouted, "That's a baby!" It was carried down into the cabin and given to the mother. She received her child with a great outburst of joy, and then fell fainting on the floor.

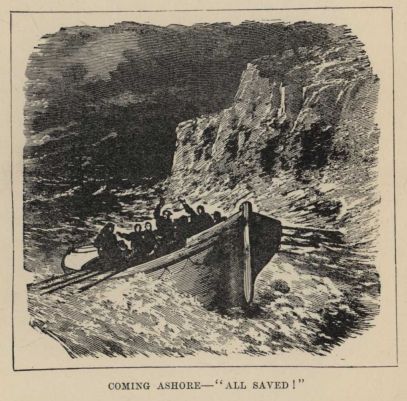

The lifeboat, having discharged her load, set forth again for the wreck. All the former dangers had to be faced and all the former difficulties overcome before the work of rescue could be resumed, but the gallant fellows persevered and were successful. The boat was rapidly filled, and again made for the steamer, to which the rescued people were transferred without mishap. The third and last journey was attended with equal good fortune. All were saved--families were reunited, and friends clasped the hands of friends. Then the lifeboat went back to remain by the wreck, for the captain thought that the ship might be got off with the next high tide.

The tug with her burden of rescued people started for Ramsgate just as day was dawning. As she steamed slowly along, the look-out man noticed a portion of a wreck to which several men were clinging. At once the tug put about to bring the lifeboat to the scene. In a short time she returned with the lifeboat in tow. Having been put in a proper position for the wreck the tow rope was cast off, and the boat advanced to the battle alone. From the position of the wreck the lifeboatmen saw that the only way of rescuing the crew was by running straight into her. This was a course attended with considerable danger, but it was the only one, so the risk had to be taken. Straight in among the floating wreckage dashed the lifeboat, a rope was made fast to the fore-rigging, and the crew, sixteen in number, dropped one by one from the mast into the boat. Then the sail was hoisted, and the lifeboat made for the steamer, the deck of which was crowded with the lately-rescued emigrants, who cheered till they were hoarse, and welcomed the rescued men with outstretched arms.

The poor fellows had a touching story to tell. For hours they had clung to the mast, hearing the timbers cracking and smashing as the heavy sea beat against the wreck, and fearing that they would be swept away every minute. They had seen the steamer's lights as she passed them on her errand of mercy the night before, and had shouted to attract the notice of those on board, but the roar of the wind drowned their voices. When they saw the steamer in the morning they were filled with new hope, and made signals to attract her attention, but to their horror she turned and went back. At first they thought that they were to be abandoned to their fate, and then it dawned upon them that she had gone for the lifeboat. This was, as we know, the case. Their vessel was named the Demerara.

There was a scene of great enthusiasm on Ramsgate pier, when the tug, with the lifeboat in tow, entered the harbour with flags flying to tell the glad news that all were saved; and as the one hundred and twenty rescued men, women, and children were landed, cheer after cheer rent the air. It is interesting to know that the Fusilier was afterwards got off the sands.

CHAPTER VII.

THE "BRADFORD" TO THE RESCUE.

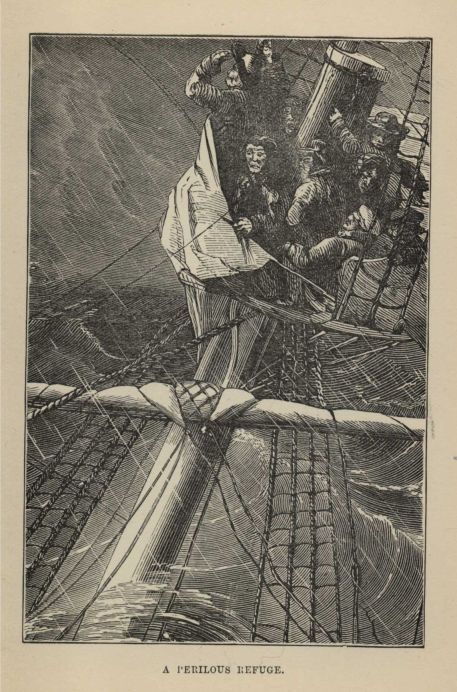

f the many heartrending scenes which have taken place on our coasts, there is perhaps none more calculated to move our sympathies for the imperilled crews, and our admiration for the devotion and unconquerable courage of our noble lifeboatmen, than the wreck of the Indian Chief, which took place on the 5th of January 1881. The vessel stranded at three o'clock in the morning, and the crew almost immediately took to the rigging, where they remained for thirty hours exposed to the raging elements, and in momentary expectation of death. During the night one of the masts fell overboard, and sixteen unfortunate men, who had lashed themselves to it, were drowned in sight of their comrades, who were powerless to afford them any aid.

f the many heartrending scenes which have taken place on our coasts, there is perhaps none more calculated to move our sympathies for the imperilled crews, and our admiration for the devotion and unconquerable courage of our noble lifeboatmen, than the wreck of the Indian Chief, which took place on the 5th of January 1881. The vessel stranded at three o'clock in the morning, and the crew almost immediately took to the rigging, where they remained for thirty hours exposed to the raging elements, and in momentary expectation of death. During the night one of the masts fell overboard, and sixteen unfortunate men, who had lashed themselves to it, were drowned in sight of their comrades, who were powerless to afford them any aid.

Meanwhile, word had reached Ramsgate that a large ship had stranded on the Goodwins. The tug Vulcan, with the lifeboat Bradford in tow, was accordingly sent out to render assistance. There was a strong south-easterly gale blowing, and the sea was running very high. As the boats left the harbour on their noble mission, volumes of water burst over them, and the lifeboat was frequently hidden from the gaze of the hundreds who thronged the pier to witness her departure.

The wind was piercing, and, as one of the crew afterwards declared, it was more like a flaying machine than a natural gale of wind; but it was not until they had got clear of the North Foreland that they experienced the full force of the tempest. The tug was only occasionally visible, and it seemed a perfect miracle that she did not founder. The lifeboat fared no better, for the heavy waves dashed into her as if they would have knocked her bottom out.

The short January day was now drawing rapidly to a close, and still the wreck was not in sight. What was to be done? The question was a serious one, and so the men began to talk the matter over. It was bitterly cold, and if they remained where they were their sufferings would be great; but then they would be on the spot to help their fellow-creatures as soon as another day gave them sufficient light to see where they were.

"We had better stop here and wait for daylight," said one.

"I'm for stopping," said another.

"We're here to fetch the wreck, and fetch it we will, if we wait a week," shouted a third.

Without a murmur of dissent or a moment's hesitation, the brave fellows prepared to pass the night in the open boat. But first they had to communicate with the tug. They hailed her, and when she came alongside they informed the captain of their intention. "All right," he shouted back, and then the steamer took up her position in front, keeping her paddles slowly revolving, so that she should not drift.

Throughout the night these gallant lifeboatmen lay huddled together for warmth in the bottom of the boat. In such weather it required vigorous exercise to keep the blood circulating, and before morning dawned several of the men were groaning with the cold, and pressing themselves against the thwarts to relieve the pain. But even these hardships were borne without complaint, as they thought of the sufferings of the shipwrecked crew, and jokes were not wanting to help to pass the time.

"Charlie Fish," said one of the boatmen, speaking to the coxswain, "what would some of them young gen'l'men as comes to Ramsgate in the summer, and says they'd like to go out in the lifeboat, think of this?" A general roar of laughter was the answer.

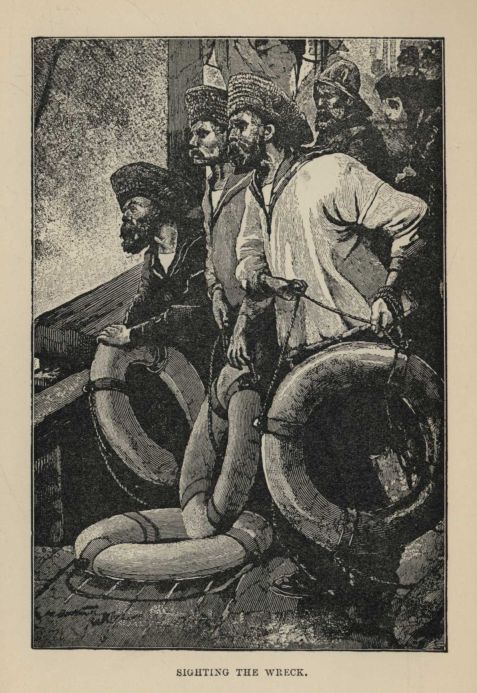

At length the cold grey light of early dawn proclaimed the advent of a new day. Keen eyes gazed anxiously towards the sands for a sight of the wreck. At first nothing was visible but tall columns of whirling spray, then after a time a mast was seen sticking up out of the water about three miles off. The scene was enough to make the stoutest heart quail, and the lifeboatmen held their breath as they looked at the water rushing in tall columns of foam more than half-way up the mast. The roar of the sea could be heard even above the whistling of the wind.

The feeling of fear, however, seems to have no place in the heart of the lifeboatman, and in a few minutes the Bradford was cast loose from the tug, her foresail was hoisted, and away she sped into the surf on her errand of mercy, every man holding on to the thwarts for dear life. As they approached nearer the vessel they could see a number of men dressed in yellow oilskins lashed to the foretop. The sea was fearful, and the poor fellows, who had long since abandoned all hope, were afraid that the lifeboat would be unable to rescue them. Little did they know the heroic natures of the crew of the Bradford. Sooner would every man have gone down to a watery grave than abandon the wreck till all were saved!

The boat came to close quarters, and the anchor was thrown out. The sailors unlashed themselves and scrambled down the rigging to the shattered deck of their once noble ship. The boatmen shouted to them to throw a line. This was done, a rope was passed from the lifeboat to the wreck, and the work of rescue began.

Where the mast had fallen overboard there was a horrible muddle of wreckage and dead bodies. "Take in that poor fellow there," shouted the coxswain, pointing to the body of the captain, which, still lashed to the mizzenmast, with head stiff and fixed eyeballs, appeared to be struggling in the water. The coxswain thought he was alive, and when one of the sailors told him that the captain had been dead four hours, the shock was almost too great to be borne. Little wonder is it that these gallant fellows were haunted by that ghastly spectacle for many a day, and it was no uncommon thing for them to start up from sleep, thinking that these wide-open, sightless eyes were gazing upon them, and the dumb lips were calling for help.

The survivors were taken off the wreck with all speed, and the boat's course was shaped for Ramsgate harbour. Outside the sands the tug was in waiting, a rope was quickly passed on board, and away they steamed. Meanwhile, news had come to Ramsgate that three lifeboats along the coast had gone out and returned without being able to reach the wreck. This naturally caused great anxiety in the town, and it was feared that some accident had befallen the Bradford. From early morning on Thursday, anxious wives and sisters were on the lookout on the pierhead. About two o'clock the Vulcan came in sight with the lifeboat astern. Almost immediately the pier was thronged with a crowd numbering about two thousand persons. At half-past two the tug steamed into the harbour, having been absent upwards of twenty-six hours.

"One by one," writes Clark Russell, "the survivors came along the pier, the most dismal procession it was ever my lot to behold, eleven live but scarcely living men, most of them clad in oilskins, and walking with bowed backs, drooping heads, and nerveless arms. There was blood on the faces of some, circled with a white encrustation of salt, and this same salt filled the hollows of their eyes and streaked their hair with lines which looked like snow. They were all saturated with brine; they were soaked with sea-water to the very marrow of their bones. Shivering, and with a stupefied rolling of the eyes, their teeth clenched, their chilled fingers pressed into the palms of their hands, they passed out of sight. I had often met men newly rescued from shipwreck, but never remember having beheld more mental anguish and physical suffering than was expressed in the countenances and movements of these eleven sailors."

They were taken to the Sailors' Home, and well cared for; the lifeboatmen were escorted home to their families amid the cheers of the spectators. Thus ended a splendid piece of service. "Nothing grander in its way was ever done before, even by Englishmen."

Five days later a most fitting and interesting ceremony took place on the lawn in front of the coastguard station at Ramsgate, when the medals and certificates of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution were awarded to those who had taken part in the rescue. The coxswain of the Bradford received the gold medal, each of the crew of the lifeboat and the captain of the tug received silver medals, the engineer was presented with the second service clasp, and a certificate of thanks was handed to each of the Vulcan's crew. The Duke of Edinburgh, himself a sailor, in distributing the honours, told the men that their heroic conduct had awakened the greatest possible interest and pride throughout England; and he declared his conviction that though they would prize the rewards greatly, they would most value the recollection of having by their pluck and determination saved so many lives.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE LAST CHANCE.

xactly ten years after the events narrated in the previous chapter had taken place, the Ramsgate lifeboatmen were again conspicuous for their gallantry in saving life under the most trying circumstances. About one o'clock on the morning of the 6th of January 1891, the schooner Crocodile, bound for London with a cargo of stone, ran ashore on the Goodwins. Blinding snow squalls prevailed at the time, and the wind blew with the force of a hurricane. Immediately the vessel struck, she turned completely round and went broadside on to the sands. On realising their position, the crew burnt flares, made by tearing up their clothes and soaking the rags in oil, and attracted the attention of those on board the Gull lightship, who immediately fired signal-guns to summon the lifeboat. Scarcely, however, had the flare been burned than the sailors were compelled by the high seas to take to the rigging. Great waves swept the decks, carrying everything before them; even the ship's boats were wrenched from the davits and whirled away as if they had been toys.

xactly ten years after the events narrated in the previous chapter had taken place, the Ramsgate lifeboatmen were again conspicuous for their gallantry in saving life under the most trying circumstances. About one o'clock on the morning of the 6th of January 1891, the schooner Crocodile, bound for London with a cargo of stone, ran ashore on the Goodwins. Blinding snow squalls prevailed at the time, and the wind blew with the force of a hurricane. Immediately the vessel struck, she turned completely round and went broadside on to the sands. On realising their position, the crew burnt flares, made by tearing up their clothes and soaking the rags in oil, and attracted the attention of those on board the Gull lightship, who immediately fired signal-guns to summon the lifeboat. Scarcely, however, had the flare been burned than the sailors were compelled by the high seas to take to the rigging. Great waves swept the decks, carrying everything before them; even the ship's boats were wrenched from the davits and whirled away as if they had been toys.

In answer to the guns the Ramsgate tug and lifeboat were manned and steered in the direction of the flare. Huge seas broke over the lifeboat and froze as they fell on the almost motionless figures of the boatmen. The snow came down in pitiless showers, enveloping them in its white mantle. In a short time the tug had towed the Bradford to windward of the vessel. Then the rope was thrown off, the sail was hoisted, and the boat made for the wreck. She had not gone far before a terrific snow squall overtook her. Fearing that they would be driven past the vessel without seeing her, the coxswain ordered the anchor to be thrown out. This was done, and the boat lay-to till the sudden fury of the gale had spent itself. Then the anchor was hoisted in and all sail made for the wreck.

Again the anchor was let go, just to windward of her, and the lifeboat was veered cautiously down. As they drew nearer, the men could see the crouching figures of the sailors lashed to the rigging. They seemed more dead than alive, and gazed upon the men who were risking their own lives, to save them with the fixed stare of indifference or death. The lifeboat ran in under the stern and was brought up alongside. The grapnel was got out, and one of the men stood up, ready to throw it into the rigging on the first favourable opportunity. Suddenly a mighty billow swooped down upon them. The anchor cable--5 inches thick--was snapped like a thread, and the boat was borne on the crest of the wave far out of reach of the wreck.

As quickly as possible the sail was again set, and the trusty Bradford made for the tug, which was burning blue lights to show where she was. After many attempts a rope was secured on board, and the Aid steamed to windward the second time with the lifeboat in tow. Once more she was in a favourable position for the wreck, the rope was cast off, and the sail hoisted. The second and last anchor was let go, and the cable was slowly slackened. If they failed this time the men must perish. It was a terribly anxious moment, but fortune favoured them, and the lifeboat was successfully brought into her former position alongside.

The hull of the Crocodile was now entirely under water, and her deck was washed by every wave. High up in the rigging, on the side opposite to that on which the lifeboat lay, the crew were huddled. The only way for them to reach the lifeboat was by climbing to the masthead and coming down on the other side. This is a feat which requires no little steadiness of hand and eye, and when we remember that these poor sailors had been exposed for nearly five hours on this January night to the full fury of a wintry storm, we shall be better able to appreciate the terrors through which they passed before they found themselves safe in the lifeboat.

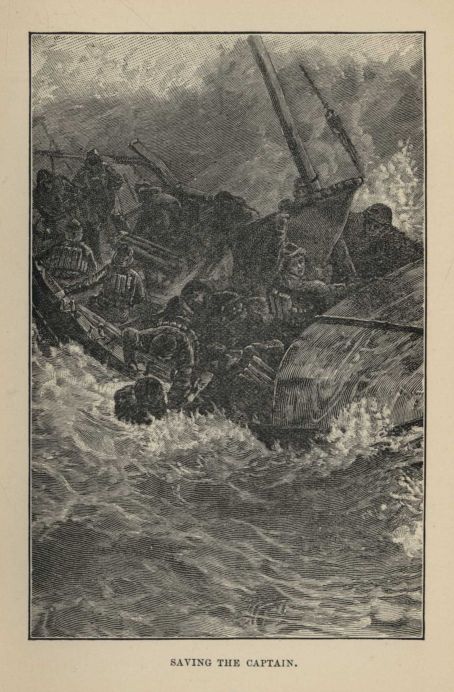

In obedience to the coxswain's order, they unlashed themselves and began to crawl aloft. Every sea shook the vessel, and, as she settled again on the sands, the masts bent almost double. Their progress was slow, but before long they were in a position to be rescued. This was done with great difficulty, for the heavy seas caused the lifeboat to strike against the vessel several times with considerable violence, but her cork fender protected her from injury. At length the whole crew of six men were hauled safely on board. The captain alone remained to be rescued.

High up at the masthead he could be seen preparing to cross from the opposite side. Benumbed by the cold and bewildered by the swaying of the masts, he paused for a moment. The lifeboatmen shouted words of encouragement to him, and he prepared to come on, but he missed his hold and fell into the seething waves eddying round the wreck. As he fell his lifebelt caught on something, and was torn off, and before the boatmen could lay hold of him he was swept out of their sight for ever.

The lifeboat was quickly got clear of the wreck, and proceeded under sail to the tug, which was in waiting some distance off. Ramsgate was reached about eight o'clock in the morning, where the rescued men were supplied with dry clothing and food, of which they stood greatly in need.

There is a circumstance of peculiar interest connected with the wreck of the Crocodile. Two days before she struck on the sands, her sister ship, the Kate, also laden with stone, was stranded on the Goodwins. On that occasion the lifeboat Mary Somerville of Deal went out to assist. The lifeboatmen were employed to throw the cargo overboard and try to get the vessel afloat. This was successfully accomplished, and on the morning of the day on which the Crocodile was wrecked, her sister ship was towed into Ramsgate harbour with her crew of nine men on board.

CHAPTER IX.

HARDLY SAVED.

he first duty of the crew of the lifeboat is to save life, but it frequently happens that a stranded vessel is not so seriously damaged as to hinder her being got afloat again. Under these circumstances the men are at liberty to assist in saving the vessel if the captain is willing to employ them. This is a very dangerous business, and often after long hours of peril and labour the ship is dashed to pieces by the waves, and the men are with difficulty rescued. A splendid example of the risk attending this salvage service occurred several years ago on the Goodwin Sands.

he first duty of the crew of the lifeboat is to save life, but it frequently happens that a stranded vessel is not so seriously damaged as to hinder her being got afloat again. Under these circumstances the men are at liberty to assist in saving the vessel if the captain is willing to employ them. This is a very dangerous business, and often after long hours of peril and labour the ship is dashed to pieces by the waves, and the men are with difficulty rescued. A splendid example of the risk attending this salvage service occurred several years ago on the Goodwin Sands.

In response to signals of distress the tug and lifeboat put out from Ramsgate pier, and found a Portuguese ship on the sands. Her masts and rigging were still standing, and there was every chance of her being saved. The vessel had gone head on to the Goodwins, and the boatmen got an anchor out from the stern as quickly as possible, with the intention of working her off into deep water by the help of the tug; but this attempt had soon to be abandoned. Shortly after midnight the gale increased, and heavy seas began to roll over the sands. The ship, which had all along lain comparatively still, was now dashed about by the waves with terrific violence. The lifeboat remained alongside, and her crew, knowing well that a storm on the Goodwins is not to be trifled with, urged the sailors to come on board. The captain, however, refused to leave his ship, so there was nothing for it but to wait until an extra heavy sea should convince the captain that it was no longer possible to save the vessel.

This happened sooner than could have been expected, for almost the very next instant a wave struck her and smashed several of her timbers. The sailors now begged to be taken on board, and they were told to "Come on, and hurry up." But first of all they had to get their belongings. Though every moment was of consequence, the coxswain had not the heart to forbid them bringing any articles on board, and eight chests were lowered into the lifeboat. Then one by one the crew abandoned the vessel.

All danger was not yet over. The seas dashed over the ship into the lifeboat, blinding and drenching the men, and rendering still more difficult their task of keeping the boat from being crushed under the side of the vessel. Haul at the cable as they would, they were unable to get her out of the basin which the brig had made for herself in the sand. To add to the horror of their position, the wreck threatened to fall over on the top of them every moment.

There was only one way of escape--to wait until the tide rose sufficiently to float them off, but the chances were that when the tide rose it would be too late to save them. They would then have ceased to struggle or to suffer, and the battered remains of their trusty boat would tell those at home what had become of them. Crouching down as low as possible to avoid being struck by the swaying yards and fluttering canvas, the men waited for deliverance--or would it be death?

At length the tide reached her, and the boatmen redoubled their efforts to haul their little vessel away from the ship. Slowly, very slowly, she drew away from that terrible black hull and those swaying yards. But now a new and unforeseen difficulty presented itself. In the face of the wind and tide it was impossible for them to get away from the sands, so in spite of their exhaustion and the black darkness of the night, they determined to beat right across the sands. They hauled hard on the cable again, but the anchor began to drag, and they were drifting back again to the wreck.

"Up foresail!" shouted the coxswain, at the same time giving orders to cut away the anchor. The boat bounded forward for a few yards and then struck on the sands again fearfully near to the wreck. Wave after wave dashed into the boat and nearly washed the wearied men overboard, but they held on like bulldogs. Three times she was driven back to the wreck, and again and again she grounded on the sands.

One of the crew, an old man upwards of fifty years of age, thus described his feelings.

"Perhaps my friends were right when they said I hadn't ought to have gone out, but, you see, when there is life to be saved, it makes a man feel young again; and I've always felt I had a call to save life when I could, and I wasn't going to hang back then. I stood it better than some of them, after all; but when we got to beating and grubbing over the sands, swinging round and round, and grounding every few yards with a jerk, that almost tore our arms out from the sockets; no sooner washed off one ridge, and beginning to hope that the boat was clear, than she thumped upon another harder than ever, and all the time the wash of the surf nearly carrying us out of the boat--it was truly almost too much for any man to stand. I cannot describe it, nor can anyone else; but when you say that you've beat and thumped over these sands, almost yard by yard, in a fearful storm on a winter's night, and live to tell the tale, why it seems to me about the next thing to saying that you've been dead and brought to life again."

At length deep water was reached, and their dangers were over. Quickly more sail was hoisted, and the boat headed for the welcome shelter of Ramsgate pier. All were in good spirits now, even the Portuguese sailors who had lost nearly everything they possessed. On the way home the lifeboatmen noticed that they seemed to be discussing something among themselves. Presently one of them presented the coxswain with all the money they could scrape together, amounting to about £17, to be divided among the crew. "We don't want your money," shouted the hardy fellows, and with many shakings of the head they returned the generous gift. The harbour was soon afterwards reached, where they were landed overjoyed at their miraculous escape, and by every means in their power endeavouring to show the gratitude they felt but could not speak.

CHAPTER X.

A WRESTLE WITH DEATH.

ne bleak December night, a few years ago, word was brought to Ramsgate that a large vessel had gone ashore on the Goodwin Sands. Immediately on receiving the message, the harbour-master ordered the steam tug Aid to tow the lifeboat to the scene of the disaster. The alarm bell was rung, the crew scrambled into their places, a stout hawser was passed on board the tug, and away they went into the pitchy darkness.

ne bleak December night, a few years ago, word was brought to Ramsgate that a large vessel had gone ashore on the Goodwin Sands. Immediately on receiving the message, the harbour-master ordered the steam tug Aid to tow the lifeboat to the scene of the disaster. The alarm bell was rung, the crew scrambled into their places, a stout hawser was passed on board the tug, and away they went into the pitchy darkness.

The storm was at its height, and "the billows frothed like yeast" under the lash of the furious wind. Hardly had the lifeboat left the shelter of the breakwater than a huge wave burst over her, drenching the men to the skin, in spite of their waterproofs and cork jackets, and almost sweeping some of them overboard. At one moment they were tossed upwards, as it seemed to the sky; at another they dropped down into a valley of water with huge green walls on either side. Again and again the spray dashed over them in blinding showers, but no one thought of turning back.

Bravely the stout little tug battled with the waves, and slowly but surely made headway against the storm, dragging the lifeboat after her. As they neared the probable position of the wreck, the men eagerly strained their eyes to gain a sight of the object of their search, but nothing met their gaze save the white waters foaming on the fatal sands. Suddenly, through the flying spray, loomed the hull of a large ship, with the breakers dashing over the bows. Not a single figure was visible in the rigging, and on that desolate, wave-swept deck no mortal man could keep his footing for five seconds.

"All must have perished!" Such was the painful conclusion arrived at by the lifeboatmen as they approached the stranded vessel, but it would never do for them to return and say that they thought all the crew had been swept away; they must go and find out for certain. The tow rope was accordingly thrown off, the sail was hoisted, and the lifeboat darted among the breakers. Suddenly one of the lifeboatmen uttered a cry, and on looking in the direction of his outstretched arm, his companions saw four figures crouching under the lee of one of the deck-houses. The anchor was immediately let go, and the lifeboat was brought up under the stern of the wreck.

To the astonishment of the boatmen the sailors had as yet hardly noticed their presence. They seemed to be deeply absorbed in making something, but what it was could not be seen. Presently one of the men rose up, and coming to the stern of the vessel threw a lifebuoy attached to a long line into the sea. It was afterwards learnt that, from the time their vessel struck, these poor fellows had busied themselves in preparing this buoy to throw to their rescuers when they should arrive.

Borne by the wind and tide the lifebuoy reached the boat, and was at once seized and hauled on board. An endeavour was then made to pull the lifeboat nearer the wreck, but the strength of the men was of no avail against that of the tempest. Great seas came thundering over the wreck and nearly swamped the boat. Several men were shaken from their places, but fortunately none of them were washed overboard. They redoubled their efforts after each repulse, but with no better fortune.

Seeing that the lifeboat could not come to him, the captain of the doomed vessel determined to go to her. Choosing a favourable moment, he abandoned the shelter of the deck-house, threw off his coat, seized hold of the line, and jumped into the sea. The waves tossed him hither and thither as they would a cork, but he held on like grim death. At one moment he hung suspended in mid air; at another he was engulfed by the raging waters. The lifeboatmen, powerless to render any assistance, watched the unequal contest with bated breath. Bravely the captain struggled on, and gradually reduced the distance between himself and the hands stretched out ready to save him. Suddenly a tremendous wave broke over the wreck, and when it passed the men saw that he had been swept from the rope.

With all the might of his strong arm the coxwain hurled a lifebuoy towards the drowning man. Fortunately it reached him, and with feelings of inexpressible relief the men saw him slip his shoulders through the buoy as he rose on the crest of a breaker. "All right," he shouted, as he waved his hand and vanished in the darkness.

Suddenly a terrific crash reminded the lifeboatmen that there were still two men and a boy on the wreck. Turning round they saw that the mainmast had given way and gone crashing overboard. Startled by the suddenness of the shock the survivors supposed that the end had come, and with a blood-curdling scream of despair they rushed to the side of the vessel imploring aid. The chief mate sprang into the water and endeavoured to swim to the lifeboat. The men again laid hold of the rope and tugged with might and main to get nearer the wreck, but the storm mocked their efforts. Then they tried to throw him a line, but it fell short. Again and again they tried, but in vain. The mate battled bravely for life, and as he was a powerful man, all thought that he would succeed, but he was weakened by exposure and want of food, and his strength was rapidly failing. The lifeboatmen exerted themselves to the utmost to reach him, pulling at the rope till every vein in their bodies stood out like whipcord. Not an inch could they move the boat. The man's agonising cries for help nearly drove them mad, but they could do no more. His fate was only a matter of time, and in a few moments he sank into his watery grave, with one long shriek for help.

There were still a man and a boy on the wreck. With heavy hearts, and a dimness about the eyes that was not caused by the flying spray, the lifeboatmen once more vainly attempted to get nearer the wreck. Following the captain's example, the man seized the rope and jumped into the water. Fortune favoured him, and though he was tossed about in a frightful manner he succeeded in pulling himself right under the bows of the lifeboat. Then his strength failed, and he would have been instantly swept away and drowned, had not one of the lifeboatmen flung himself half-way over the bow of the boat and caught the perishing sailor by the collar. Stretched on the sloping foredeck of the boat he could not get sufficient purchase to drag the man on board, and indeed he felt himself slowly slipping into the sea.

"Hold me! hold me!" he cried, and several of his companions at once seized him by the legs. The weight of the man had drawn him over till his face almost touched the sea, and each successive wave threatened to suffocate him. To add to the horror of the situation, a large quantity of wreckage was seen drifting right down upon the bow of the boat towards the spot where the men were struggling. If it touched them it meant death. For a moment it seemed endued with life, and paused as if to consider its course, then just at the last minute it spun round and was borne harmlessly past.

The crew now made a desperate attempt to haul the two men on board. Finding that the height of the bow prevented their success, they dragged them along the side of the boat to the waist, and pulled them in wet and exhausted.

The boy alone remained on the wreck, which was now fast breaking up. How to help him was a question not easily answered, for with all their pulling they could not approach nearer the vessel. Suddenly the difficulty was solved for them in a most unexpected manner. A tremendous sea struck the vessel and swept along the deck. When the spray cleared away the boy was nowhere to be seen. Anxiously every eye watched the water, and presently a black object was seen drifting towards the boat. "There's the boy!" shouted the men in chorus. Slowly, very slowly, as it seemed to them, he drifted nearer and nearer. At length he came within reach of a boat-hook, and was lifted gently on board--unconscious, but still alive. After the usual restoratives had been applied, he revived.

Nothing more could be done at the wreck now, so the sail was hoisted and the boat's head turned towards the harbour. But their work of saving life was not yet done. As they sped along before the blast a dark object was seen tossing up and down upon the waves. They steered the boat towards it, and to their astonishment found the captain with the lifebuoy round him, still battling for life. He was hauled on board in an utterly exhausted condition. Before reaching the shore he revived, and told the men that his vessel was the Providentia, a Finland ship, and that he himself was a Russian Finn. The men were landed at Ramsgate in safety. A few days later, news came from Boulogne that the remainder of the crew, who had left the wreck in a boat, had been blown across the Channel and landed on the French coast.

CHAPTER XI.

A DOUBLE RESCUE.

lang! clash! roar! rings out the bell at the lifeboat-house, its iron voice heard even above the thunder of the surf and the whistling wind, warning the sleeping inhabitants of Deal that a vessel has gone ashore on the Goodwins. A ray of light gleams across the dark street as a door opens and a tall figure rushes out--it is that of a lifeboatman. Presently he is joined by others, and all hurry on as fast as possible, in the face of the furious wind, to reach the boathouse. Each man buckles on his lifebelt, and takes his place in the lifeboat. Those who have failed to get a place help to run it down to the white line of surf, over the well-greased boards laid down on the shingle. The coxswain stands up in the stern with the rudder lines in his hands, watching for a favourable moment to launch. The time has come, the order is given, and away dashes the lifeboat on her glorious errand.

lang! clash! roar! rings out the bell at the lifeboat-house, its iron voice heard even above the thunder of the surf and the whistling wind, warning the sleeping inhabitants of Deal that a vessel has gone ashore on the Goodwins. A ray of light gleams across the dark street as a door opens and a tall figure rushes out--it is that of a lifeboatman. Presently he is joined by others, and all hurry on as fast as possible, in the face of the furious wind, to reach the boathouse. Each man buckles on his lifebelt, and takes his place in the lifeboat. Those who have failed to get a place help to run it down to the white line of surf, over the well-greased boards laid down on the shingle. The coxswain stands up in the stern with the rudder lines in his hands, watching for a favourable moment to launch. The time has come, the order is given, and away dashes the lifeboat on her glorious errand.

Onward she plunged under close-reefed sail in the direction of the flares, which the shipwrecked men were burning to tell the rescuers of their whereabouts. Suddenly the light went out and was seen no more. A shriek echoed over the waves, but none could say whether it was that of "some strong swimmer in his agony," or only the voice of the wind. The lifeboatmen looked around them on every side, but they could see nothing; they listened, and heard nothing; they shouted, but no answer came back. "A minute more and we would have had them," says the coxswain. "Hard lines for all to perish when help was so near."