The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Cruise of a Schooner, by Albert W. Harris This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Cruise of a Schooner Author: Albert W. Harris Release Date: March 17, 2013 [EBook #42351] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CRUISE OF A SCHOONER *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

SUNSET ON THE MOJAVE DESERT

PREFACE

Years ago, no matter how many, my head was filled with queer notions. Probably there are still a few queer thoughts and notions left there. I refer to them as queer from the point of view from which the reader will look at them. Personally, I have considered them very sane and serious, and quite worth working out.

To begin with, when a boy, I had a great yearning for a pony. I had all sorts of notions about ponies, but when I didn’t get one as a boy, I planned to have more ponies when I grew up, and better ones, than any one ever had before. In fact, I built a “pony” castle in the air.

I had another notion that I wanted to be a farmer, and have a big ranch with horses and cattle, but when I could not, as a boy, see any chance to work this out at once, I proceeded in my mind to make it come true, and pictured and planned it all out, and built such a fine castle of a farm that I could see it almost as plainly in my mind’s eye as though it were a reality.

The nearest I ever got to my castle for many years was when riding over the plains on a cow pony, the cattle and the pony belonging to some one else; the fun, however, was all mine. I still worked on my castles and added another. I pictured myself some time riding or driving overland to California, crossing the plains and mountains with a party of congenial spirits, and following the old Santa Fe trail to the Pacific Ocean.

When I talked seriously of these things to ordinary mortals, they smiled, and said, “You think you will do these things some day, but you never will; they are all air castles.” Similar expressions greeted any reference to ponies, farms, or overland trips, as the years went by, till they began to take some such place in my own mind, and I found myself saying, “Air Castles, nothing but Air Castles.” Still, as these castles began to crumble and grow mossy with years, I resolved to repair them, and in so doing awoke to the fact that two of my castles had materialized. They had come to earth, so to speak, and I found myself actually possessed of the farm and the ponies; the identical ponies, it seemed to me, I had seen in my mind’s eye when a boy. It took me some time to actually realize that the farm and the ponies were really mine, but, when I finally came to accept them as realities, I knew my other castle could not be far off, and I began again planning to take the overland trip.

I had planned this trip in my mind so many times and in so many ways that the only new sensation was that now it would surely come true, but I kept on planning it annually for five years before I actually started on the trip itself, and then I started from the Pacific Ocean and drove east.

The following account of this trip may be of sufficient interest to make it worth reading, at least, and if any one who reads it feels more hopeful of finishing the building of the castles he is now engaged upon, it will have answered its purpose.

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

In planning an extended trip in this country, or Europe, the first thing one usually does is to consult, if convenient, friends who have been there before. After deciding when you will start, you look up time-tables or the departure of boats, reserve accommodations for your party, pack your grips or trunks, and you are ready to start. In driving overland it is different; you may find some one to consult with who has made the trip before you,--but the chances are that all those who have done so are dead. You will have no time-tables to consult and, if you go as we did, no reservations to make.

It all looked so easy, while I was only thinking about it, that it seemed simplicity itself. Just get a team of horses and a wagon, and start. Incidentally, I would have plenty of company,--so many folks had said they would like to go. We would have a tent, cots, cook, guide, and all the necessary outfit.

As a matter of fact, this is what really happened. When approached on the subject, my friends, who had talked about going with me, were one by one unexpectedly prevented from making the trip. They either had to go to Europe or had such pressing business duties that they could not possibly get away; every one of them, however, said something that sounded as if they were very sorry they could not go, but which really meant that they had drummed up this excuse on purpose.

As a result, I found I had only myself to consult, and so I set a date on which I was sure I could start. It was only after this date was set that I was sure I was going to get away. May 1, 1910, was the time decided upon, but, as the roads in and around Chicago are not very good at that season, I concluded that this would be the best time of the year to cross the desert. After some planning I decided to tackle the worst part of the trip first, while my enthusiasm lasted, and so, I concluded, I would go to California, get my outfit together, and start from there.

I had another reason besides the time of the year and the condition of the roads for starting from California, which was that I would get away where my friends could not talk me out of starting by telling me how hard the trip was, how foolish I was, how tired I would be of it all before I finished, and that I would sell the outfit and come back before I had been gone a month. In view of the above practical as well as precautionary reasons, I left Chicago for Los Angeles. All I took with me was a few old clothes and my Chesapeake dog Tuck, planning to outfit in full at Los Angeles, and start from there as soon as I could possibly get ready. At the last moment I received word from my old hunting partner, Dr. Lancaster, of Nevada, Missouri, that he and his brother Robert would make the trip with me and would meet me at Los Angeles on May the fifth. This was especially gratifying news, as I had been rather afraid I might have to make the trip all alone.

Arriving at Los Angeles, May fifth, I met the Doctor and Bob, who had come down from San Francisco, and we at once proceeded to get together a suitable outfit for the trip. It took us ten days to do this, as we had a wagon to buy and fit up with bows and overjets, together with a platform for the water barrels; besides horses and provisions, a wagon sheet, tarpaulin, stove, tent, and a lot of other things we thought we needed.

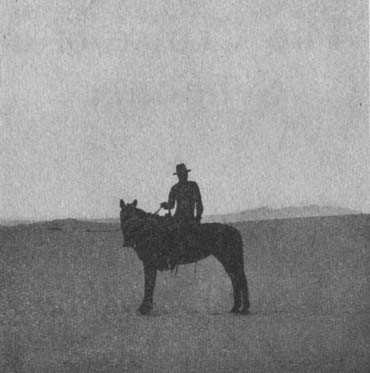

While assembling the outfit we spent considerable time looking over a line I had drawn on the map before leaving Chicago, and which we aimed to follow as closely as possible in going east to Chicago.

This line was drawn without regard to roads, mountains, or desert, and represented as short a line as I thought the lay of the land would permit. It was so straight and looked so easy on the map that we wondered why the Forty-niners went so far south, and the Mormons so far north. We planned how many miles we could make in a day, and made a schedule of where we would be on certain dates, so that our families might communicate with us if necessary.

Although our maps showed towns here and there in the desert, we began to consider our undertaking quite seriously when the old-timers, who were familiar with the desert, began to ask concerning our route. On looking at the line on our map they began to make predictions, such as, “You will never get across the Mojave so late in the season without mules,” “No wagon can follow the route you have mapped out,” “If you get through to Las Vegas without leaving your outfit strung along the trail, you will be lucky.” Such remarks set us to thinking a little hard, but as the Doctor and I were not exactly “tenderfeet,” having camped and hunted together under all sorts of conditions and in nearly all parts of the United States, we resolved to stick to our plans and go over the route as laid out, even if no one else had ever gone that way. We would demonstrate that it could be done, but we would prepare for any emergency and go as light as possible.

First, we decided to do without a guide (a good resolution, seeing there was none to be had), and next, to do without a cook. This saved provisions and water, and made it possible to travel with less baggage. Having advised our families where we would be at various times, and having collected our outfit at the barns of the Southern California Edison Company, we were ready to start Saturday morning, May the fourteenth.

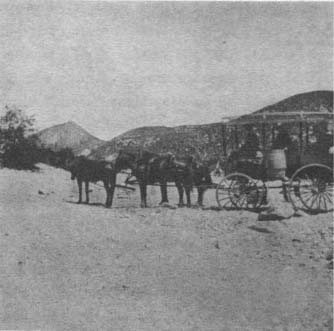

In order that the reader may have in his mind’s eye a picture of the outfit, including the members of the party, not omitting the dog, I will try to paint a word-picture of it.

Imagine that you see coming out of a side street into Peco Street, a team of medium-sized horses wearing a set of heavy tin-bespangled harness, attached to a regulation wide-tread ranch wagon with canvas top, with a water barrel on each side. A bale of alfalfa hay is seen on the carrier behind, and a lantern swings from one of the bows. Inside are two spring seats, the second being occupied by a large, brown, yellow-eyed dog, and the front seat by two very ordinary-looking individuals of uncertain age. Following the wagon is a tall slim man on a bay mare. There you have a mental picture of our outfit as seen by the inhabitants of Los Angeles that May morning as we started on our long journey.

The two men on the front seat were Robert Lancaster and the writer; the tall man on the bay mare was Doctor Lancaster. We had stored inside the wagon our provisions, bedding, tools, tent, cots, horse feed, etc. We also carried an extra single-tree and clevis, together with a single harness for use in case it should become necessary to use all three horses.

Our exit was anything but spectacular. We said good-bye to three or four friends, feeling ourselves somewhat conspicuous on account of our brand-new appearance, but were soon lost in the crowd of a large city, and forgot we were on anything but a morning’s drive in a rather slow coach through a busy town, until we found ourselves well out in the country, with an appetite for dinner.

We were taking what is called the “Lower Road,” from Los Angeles to San Bernardino, and had arrived at a grove of eucalyptus, affording shade and a place to tie and feed the horses, so we pulled out to the side of the road and made our first stop. Here we found a place to water the horses, and after eating a cold lunch and giving the horses plenty of time to eat, we interviewed our neighbors--a man and his wife and boy--camped near us, who had come from the north by wagon and were going down into Mexico. They had a team of horses and a saddle pony. They were just seeing the country, and had camped here near Los Angeles to rest up their stock and see the town. They seemed to have done nothing else all their lives but drive about, always looking for a good place to locate, but never finding one to their satisfaction; so they only stopped here and there to earn enough money to carry them to the next place.

Having satisfied our curiosity regarding our neighbors, and picked up a few bits of valuable advice about camping in the desert country, we started on, driving to within about nine miles of Pomona, where we camped alongside of the road--which was also by the side of the railroad track--having made about twenty-five miles the first day.

The Doctor and Bob had taken turns riding Dixie, and I had done the driving. This was to be our regular procedure. During this, our first day out, we had put into working operation our plans for the trip. Bob was to do the cooking and I was to do the driving and take care of the horses. We had also begun to get acquainted with the horses. It is a good deal of a lottery to pick, out of a strange bunch, suitable horses for such a trip, and as so much of the success of the journey depended upon our motive power, and so much of my reputation as a horseman on the horses themselves, I was especially interested in learning their weak points as early as possible. So far they had proved to be fearless, and as the night camp alongside of the railroad track with trains passing under their very noses, so to speak, had failed to arouse signs of nervousness in any of them, I began to feel that they could be depended upon not to stampede. Whether they could be relied upon in a pinch to pull us out of a bad place, and if they had good tempers or not, we had yet to learn.

At this camp we tried for the first time our coal oil stove, and pronounced it a decided success. Our bed was made upon the ground by putting down our tarpaulin beside the wagon. Upon it we rolled ourselves in our blankets, Tuck, the dog, sleeping at our feet and watching the camp and horses, giving us notice if anything went wrong.

Our bill of fare was to consist principally, when we could get them, of bacon and eggs, and bread and butter. Our staples were canned beans, prunes, apricots, oatmeal, rice, and crackers, in addition to which we carried, of course, salt, pepper, sugar, and condensed cream--and honey also, when we could get it. We did not take any coffee and confined ourselves to tea for a beverage, except when we made lemonade. This first camp was rather impromptu, so to speak, as we had not yet become accustomed to our outfit and had not arranged our belongings so as to get at things quickly, but before many days we had a place for everything and could find what we wanted in the dark.

Sunday morning, May fifteenth, our first morning in camp, was without any special interest. It seemed better to go on than to stay in such a bare spot beside the railroad track on the public highway, so we packed up and moved on, driving through Pomona and Ontario, then going north to what is called the “Upper Road,” through Highlands and Cuycamonga, and about 6 P. M. camped among some pepper trees, opposite a winery. The roads up to this point were good, but as we were going up grade all the time we did not drive very fast; in fact, with the load we had, the horses walked most of the time. We made about twenty-five miles this day. Our stop was again near a camp wagon, but this time we did not feel enough interest in our neighbors to visit them, and after an early supper and seeing that the horses were securely fastened for the night, we turned in, planning to get an early start in the morning.

Monday morning, the sixteenth, found us up early, as planned. We expected to drive to San Bernardino, which we figured was about twelve miles, and buy a few provisions and then start north for Cajon Pass, expecting to make our noon camp somewhere near the mountains. Usually we were able to make our camps about as planned, but this morning we were delayed.

Our start was made auspiciously, a beautiful morning with everybody, including the dog, in good spirits. Our first four miles were through vineyards just coming into full leaf, and we had been wondering how grapes could be raised in sand, and how few years it had been since this particular piece of ground was a veritable sandy desert, when a puff of wind nearly capsized the wagon, and it seemed to be getting foggy over the valley. Next I realized that the air was full of sand, and to keep the wagon from blowing over we had to take the sheet off. Before we had time to turn around and drive back to the protection of the trees on the highland, which we had just left, a sand storm was upon us, or what they call in that country a “Santa Anna.” The horses insisted on turning their backs to the wind and Bob, who was only fifty feet ahead on Dixie, could not be seen. He rode back alongside the wagon and after a parley lasting about thirty seconds we decided to push on, and, if possible, to reach the higher ground and the protection of the trees on the other side rather than go back.

Having spent some time in this vicinity a few years before, I knew there was no probability of the storm abating for hours, and that we would have to drive only about four miles to get out of its path, for it was coming out of the mouth of a canyon to the north of us. So we pushed on, blinded and choked with sand, forcing the horses to keep the road, and finally, after what seemed like hours, we drove up and out of the storm, and could catch our breath and look around.

Not having a mirror handy we could not tell how sandy we looked, but we knew how sandy we felt, and laughed at each other’s appearance until we cried the sand out of our eyes, and then decided to stop at the first convenient place and clean up before going into town. This cleaning-up process took so long that it was noontime before we reached San Bernardino, and we pitched camp that night about where we had expected to stop for lunch. “If we are to encounter a sand storm on the desert worse than this one,” we said, “we shall feel sorry for ourselves.”

The country we have come through thus far, from Los Angeles to San Bernardino, about sixty-two or sixty-three miles, is doubtless the most thickly settled valley of California, and probably has the most valuable improvements. Outside the towns and villages, the land is completely taken up by orange, lemon, and walnut groves, besides vineyards, interspersed with fields of alfalfa. Nearly every one has electric light and telephone, and ample transportation is furnished by three steam roads and many street railway and interurban lines.

From where we camped to-night we could look down over this valley, from which, as it grew dark, the lights came out like so many stars, and we realize that it will be many days before we will again be in sight of green fields and civilization, for to-morrow we are to leave all this behind and cross the San Bernardino range of mountains on our way to Daggett in the Mojave Desert.

Tuesday, May seventeenth, our first morning in a real camp “away from anywhere,” as the Doctor said, was started in true camping style. We were up at four-thirty, each busy at his particular work, Bob getting breakfast, the Doctor packing the wagon, preparatory to starting, and greasing the axles (this was done regularly every other day), and I had the horses to look after. Then came breakfast, and after that, while the dishes were being washed and odds and ends put into the wagon, I harnessed the horses, hitched them to the wagon, put the lead harness on Dixie, and we were ready to start.

We had been traveling east, but here we were to turn north across the mountains, through Hesperia and Victor to Daggett. As yet we had not had the harness on Dixie, although we had been assured that she was broken to drive, but whether she would work in the lead and pull was a question which was soon to be answered. Climbing into my seat and picking up the lines, I let off a whoop and the brake at the same time, while the Doctor let fly a handful of pebbles, and we were off. We got into the road safely and by the time we had made a few miles up the mountain trail we concluded our lead horse would do.

The road followed a mountain stream, winding ever upward, sometimes on a level with the stream, but usually cut out of the side of the mountain. Behind us we caught glimpses of mountains and valleys, and realized we were climbing up rapidly, but finally we got so far into the mountains that we could see very little, and our attention was given up entirely to the road and the horses. Bob and the Doctor walked ahead to lighten the load and signal back if any teams were coming down, so that we could pick out a safe place to pass. Noon brought us to a sandy place beside the stream, here only a rivulet, where we stopped for lunch.

While smoking our pipes in the shade, an automobile went by, going up. The ladies waved their handkerchiefs at us and, as they disappeared around a bend in the road, some one remarked, “That looks easy; I guess the road ahead must be good.” We promptly forgot the incident until the Doctor said, “I can still hear that machine. I wonder why they are not farther away by this time.” After listening a few minutes we decided something was wrong with the machine, so we all went up the road and soon found the party in the sand, where the auto had stuck in crossing the stream, and they were unable to get it up the bank. As we came up we found all four of the ladies pushing and the man working with the engine, while a baby was peacefully asleep in the tonneau. We went promptly to the rescue and after a few minutes had them out on solid ground again. The man then asked us how much he owed us. The Doctor told him in his dry way, “About a thousand dollars, but if you do not happen to have anything as small as that about you, you can settle the next time you see us.” The expression on the young man’s face for a minute was quite laughable, but he seemed to sense the situation finally, for a smile broke over his face, and with many thanks and “Good luck!” from everybody they were off.

We went back to the wagon, and, the horses having had sufficient rest, started on with all three of them in harness, and reached the summit at 3:30 P. M. Here we had a magnificent view of the mountains, some of which were snow-capped, and after a few minutes we started on again, driving down to Hesperia, through a miniature forest composed of giant cacti and juniper. On the way down we saw several pair of valley quail, some doves, and a few rabbits, which was all the game we had seen.

At Hesperia, which is on the railroad, we filled our water barrels and camped alongside of the trail, about a mile from the station and eight miles from Victor. As near as we could figure we had driven twenty-five miles, which we considered a very good day’s work in view of the long climb we had made.

CACTI FOREST

The next morning we were up at four-thirty and off at six-forty-five, arriving at Victorville at eight-thirty. The first person I saw as we drove into the little railroad town was the young man who had driven the auto we had helped out of the sand the day before. He hailed us gayly and insisted on our climbing down and “going inside,” which we promptly did. Later we repaired to the general store, where we purchased a canteen, having accidentally run the wagon over ours the evening before, and also some baled hay and grain. Then we mailed our letters and half filled our water barrels before starting on to Daggett, forty miles away over the desert.

As we understood there was a good water hole and camp site about half way, we thought it unnecessary to take any more water. We reached the water without difficulty by 6 P. M., although we met no one on the trail and were in doubt once or twice as to which fork to take. We found it a good place to camp on account of the water, but that was all. There was just a small covered tank over a spring in a bare little desert valley, without even a tree or a bush in sight. It had one advantage over previous camps, however. Doves by the hundred came here to drink and in a short time we shot all we wanted for breakfast.

The next morning we had a comparatively easy road down grade into Daggett, twenty-two miles, where we arrived at 11:30 A. M.

There was nothing especially interesting about these towns through which we had passed; Hesperia was merely a handful of people; Victorville had a few more and seemed quite prosperous. It is on the banks of the Mojave River, which at this point is fully a hundred yards wide, but shallow and muddy, with a considerable fringe of trees in places along the banks. At Daggett, however, the river had about disappeared, and a few miles farther east was entirely lost in the sand.

Here at Daggett we decided to rest our horses and take stock, so to speak. We found among our luggage a tent and two cots which we apparently would have no need of until we reached Grand Junction, Colorado, where we expected to have an addition of four to our party, so we decided to send them on to this point by freight and thus lighten our load by seventy-five pounds.

Having put our horses and wagon in a corral, we began to make inquiries regarding the road to Las Vegas, Nevada, but could get no definite information. We were told we could not cross the desert directly, but would have to go around the south end. This meant going in a circle and, as the line we had drawn on the map went straight, we declined to go around, and were conferring with some old prospectors on the feasibility of crossing the desert when we heard of a man who had just come in from Las Vegas. We did not bother to make any more inquiries then and decided to interview the man from Las Vegas the first thing in the morning. I slept in the wagon at night, but being in town the Doctor and Bob thought it would be a good idea to try beds, to see if they were softer than the sand, but the next morning they pronounced them not much of an improvement.

We found the man we were looking for shortly after breakfast at the corral, where we had left our horses. He told us his name was Knowles. He certainly looked as if he had been through something strenuous. His eyes were bloodshot and he was a nervous wreck. He said he had come from Las Vegas and had driven across en route to Los Angeles. He had a good team, a light farm wagon, but nothing in it save a water barrel, some bedding, and a dog. He seemed so mixed in his dates that it was hard to get any reliable information from him. He said it was just an accident he had got through. He had been lost and stuck in the sand and forced to abandon his load, when by good luck he came to the Salt Lake Railroad. Here the sand was so deep that his horses could not pull the empty wagon, so he drove up to the railroad track, and, as there were no trains running (the road having been washed out for eighty miles above Las Vegas early in the Spring), he drove on the track until he reached Daggett, a distance of about sixty miles. He did not dare to leave the railroad for fear that he would get lost, and he found water at the little deserted section houses he passed every twenty or thirty miles. He said that with a big wagon and load we could not get through, and advised us not to try.

We concluded that if he had got through alone we could go through, even with a heavier load, and in return for the questionable information he had given us we told him how to get to Los Angeles, and assured him that his troubles were over. He gave as much heed to our directions as we gave to his, as we afterwards found out, but we parted without disclosing our incredulity to each other.

The Doctor and I rode a freight train down to Barstow to get our mail and a few provisions that we could not get at Daggett, and while there who should we see driving up the main street but Knowles, our desert traveller! We hailed him and asked him why he had come to Barstow. He seemed quite ashamed at being discovered, but reluctantly admitted that he had intended heeding our instructions and had followed the road along the railroad track as directed, until he came to the left-hand fork which went south over the desert hills to Victor. He could not, however, trust himself to leave the railroad track for fear of getting lost again and perhaps running out of water. He said that he knew the railroad went to Victor and he had decided finally to follow it even if it was a longer route. We saw our word wouldn’t go so we called some natives into the conference, and they assured him we were right. They told him he could not follow the railroad as there was no wagon bridge across the river except at Victor, and that even if he could get across here at Barstow he would have a long weary route ahead of him, and would not reach Victor for at least two days. So he reluctantly turned about and went back to the south fork in the road, and we presume he went that way as we never saw him again, but it must have taken a great deal of fortitude on his part. Lose a man in the desert and, I imagine, he won’t want to try another stretch of desert in the same week, especially alone; so we did not blame him very much for insisting on following the railroad track.

We got back to Daggett shortly after noon on a passenger train and hunted up the old prospectors again. They were the sort who had always been in the desert and knew all about it, to hear them tell it, but for the past twenty years had probably sat around the corner store and saloon and told stories to tenderfeet about its mysteries. When we told them of Knowles’ experience and asked their advice they looked very solemn, and each in turn took refuge behind the other by asking him which of the many routes we ought to take, until they had gone the rounds and got back to the first old party again, who in desperation referred us to some one else who wasn’t there.

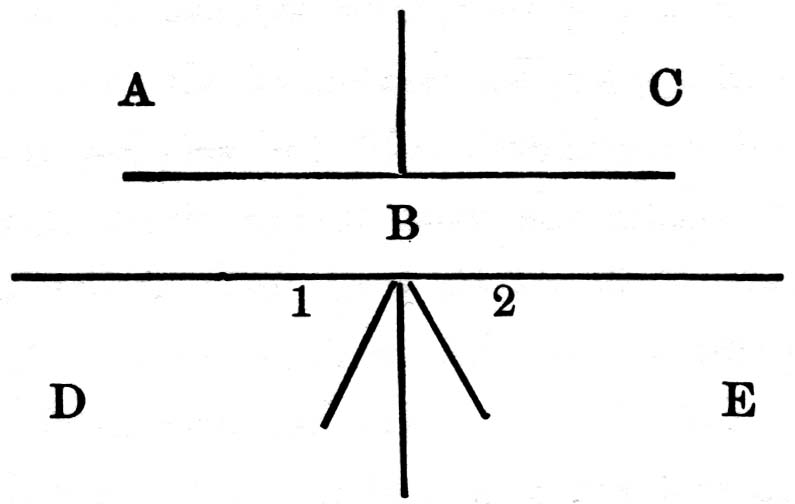

This was so amusing that we forgot we were wasting time and went prospecting around town for the man who knew, and finally located him and told our story. He assured us Knowles had taken the wrong road; he should have stayed away from the railroad because it went through the worst sand and had no feed anywhere along the line. He then drew a diagram showing how we should go east through the Mojave Canyon, then northeast and skirt the foot of the Soda Mountains to a spring on Soda Lake, and then follow the old prospectors’ trail east to Good Springs, from where we could follow the railroad to Las Vegas, Nevada. He said we could not lose the trail and that it had several springs and water holes, so that we could get through safely. He wound up, however, by saying that he had not been over this trail for ten or fifteen years, but that it was a good trail the last time he went over it.

This information, while not especially reassuring, we thought sufficient to at least make a start, as we would no doubt find some one on the trail who could put us right if we went wrong, so at 3:30 P. M. we hitched up and started on a leg of our journey that came near being our Waterloo.

It is almost impossible to describe the country we found ourselves in as we started out from Daggett on the afternoon of May twentieth, because, to use a home-made expression, “it does not sound at all as it looks.” We are to follow the Mojave River Valley until we get through the Mojave Canyon, then go north around the base of the Soda Mountains, etc., as per directions. Now the above sounds easy. It makes one think of water running down hill, and with water the mountains should have trees among the rocks, as a canyon suggests a rocky country.

PROVISIONED FOR THE DESERT

The real picture, however, which presented itself to us that afternoon was a desolate, wind-swept country; the valley looked like a wide rolling stretch of desert, flanked by bare hills, with no sign of a river. It was so cold that even with our coats on we were none too comfortable. The wind blew so hard we had to take the canvas off the wagon, and after going about ten miles we made camp for the night at a place where the trail took us close to a deserted railroad section house, which had a well. These railroad wells are really cisterns, but instead of being built to catch rain water, are designed to hold the water that the Salt Lake R. R. hauls in tank cars and distributes regularly to the section men. These section houses were located about twenty or thirty miles apart and about every other one had a well. The others had a few barrels, so, as we afterwards found out, if one came to the railroad track he knew that by following it fifteen or twenty miles he would probably find a deserted section house with a few pails of water left in a barrel, or perhaps a well with a few barrels of water, and possibly a section crew that had not been laid off. In the latter case you could find out how far it was to the next water. The water in the railroad wells was very good, but where the company found enough water to fill the big tank cars they evidently sent over the line when the road was running, no one seemed to know. We concluded, however, that it came from Kelso, California, or Las Vegas, Nevada, where we found out later they had water tanks and plenty of good water. We had met no one since leaving Daggett who could tell us about the trail ahead, but with plenty of water we felt cheerful enough and expected to make a good many miles the next day, so turned in to get an early start.

Saturday morning, May twenty-first, we found we had lost our canteen. It was so cold and windy the afternoon before that we hadn’t needed the canteen and in taking the sheet off the wagon we must have pulled it off, but where and when we didn’t know. Having plenty of water to start with we concluded we could pick up another canteen or improvise one, so we did not go back far to look for it, but started out to get over as much ground as possible.

There was no air stirring; it warmed up early and later got hot. The sand made it hard pulling and finally, at 11 A. M., we reached another deserted section house. There was a well and bucket, and, while there was no shade and the heat was intense, we managed to keep fairly comfortable by lying under the wagon and recalling how cool it had been the day before. Our dog, Tuck, seemed to feel the heat more than we did, or the horses, but it was principally because we had hard work keeping him in the wagon. If he saw anything move, from a coyote to a lizard, he would jump out of the wagon and undertake to catch it. The lizards would disappear in the sand and the coyotes in the distance, and Tuck would be hot for an hour or two afterward.

About 2 P. M. we started on again, this time driving spike, as the sand was getting harder to pull through and it took all three horses to do it. By evening we had reached what is called the canyon of the Mojave River. Here we camped in the bed of the river, which at this place was a mere rivulet. The river bed, however, was about two hundred yards wide, full of gravel and stones, with occasionally a big boulder. Willows grew in patches on the banks, and here and there a cottonwood. On each side the bare mountains had edged up to the bank, and we had a shut-in feeling. The river, however, small as it was at this time, no doubt rushed through here at times, carrying a large volume of water out into the desert beyond.

Having picked out a place to camp, where there were no rocks, we proceeded to get supper, while Tuck raced up and down in what little water there was in the river and had a glorious time. We were tired with the heat and sand, and so were the horses, but after supper we decided to take a swim; at least that is what we said, but the reader can imagine we did not swim much in a stream four feet wide and three inches deep. It was quite a grotesque sight to see three men trying to take a bath in such a stream by the light of the moon. In fact we laughed a great deal ourselves, but we were so long at it, and it grew cold so fast, that we were shivering before we got back to the wagon. Such is the difference in temperature between night and day in this country.

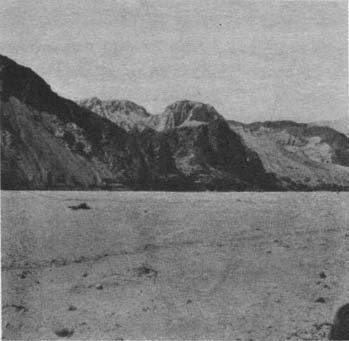

ENTERING THE MOJAVE CANYON

Sunday, the twenty-second, we started early so as to get through the canyon and out into the open desert before it should get too hot. It was a hard drive of six miles over rocks and through sand down the river bed, which, very soon after starting, we found had lost even the small stream of water which had been so welcome at our camp site. The walls of the canyon became quite rocky and in spots sheer walls of stone, and in the narrowest place we found the railroad track above us passing through tunnels and over bridges, as this canyon through which the river flows (when it does flow) is the only way the railroad could get through these mountains at this point. We supposed they were part of what is called the Soda Mountains.

At this point in the canyon we saw a section house and climbed up to see if they had any water. We found a man and his wife and daughter. They had only about half a barrel of water fit to drink, but allowed us what we wanted for that purpose. They also had two canteens, and after a parley sold us one. After our previous experience in losing two canteens, we were careful not to lose this one and luckily brought it all the way through. Besides being kind enough to let us have the canteen, they told us that the Company was now running a train each day between Las Vegas and Daggett, and that there was a tank car containing a little water on a spur track in the desert about five miles from there, so we started on much encouraged. We had a canteen and were only five miles from a tank car with water in it!

Within a mile we emerged from the canyon, the mountains receded to the north and south, and we surveyed a vast plain of sand. There was no sign of a trail, however, so we pushed out into the sand, which seemed to have no bottom. The wheels of the wagon, although having wide tires, sank to such a depth that at times we were “four spokes in the sand,” and a hundred yards was about as far as the horses could pull the wagon at a time. The Doctor and Bob walked to lighten the load, and it wasn’t very long before we began to realize that we were up against it hard. The heat was intense, and the sun on the white sand would have blinded us soon if we had not put on our smoked glasses.

EMERGING INTO THE DESERT

After plodding along at a snail’s pace for an hour or two, the Doctor said, “Well, I can see our finish unless we get out of this pretty soon,” and Bob suggested that we turn back. To turn back, however, meant miles to water, and we had just sighted the tank car. It lay off south of us about a mile and, although we still had some water in our barrels, we needed more if we were to go back or forward, either one. It was cruel to ask the horses to pull the wagon even two miles farther than necessary, through heat and sand, so the Doctor and I volunteered to take two pails each and see if there really was any water in the car. It seemed foolish to expect to find water in that car out there in the burning sandy waste, and the nearer we came to it the more unreasonable it appeared. We did find water in it, however, and although it was hot, it was good water, and after filling our four pails we managed to get back to the wagon and add this much to our supply.

From here we were supposed to follow the trail north around the base of the Soda Mountains, but as yet there was no trail, so we had to decide on some plan at once. There seemed to be three things we might do: The first was to go back. This we refused to do. The second was to go south to the Salt Lake Railroad and follow it east. This was Knowles’ advice to us and, as we had declined to take it before, we stood pat. The third and only thing left for us to do was to go north, which we did, looking for the trail the old prospector told us was there somewhere, and which would take us around to a spring above Soda Lake.

So slow was our progress through the sand that we soon grew nervous over it. In fact, I think we all became somewhat alarmed over the situation. It was very hot and we seemed getting farther from anywhere, so that when we stopped for lunch and had not yet found any signs of a trail, we decided to make a “B” line for the mountains with the hope that we might at least find better going, if we didn’t find the trail.

Before starting, however, I decided to go over and climb the nearest foothill and see if I could see Soda Lake. It was probably only a mile, but I had to stop several times and lie down to get my head in the shade of a bush, of which there were quite a number growing in the sand near the mountains. Arriving at a small sand hill, I climbed up to where a bush was growing and lay down with my head under it, and surveyed the mountains ahead and the desert at the south, but no sign of a lake or trail did I see. Then I saw through a gap in the mountains a valley, with a lake in the centre and two tents on the bank. This, I concluded, was a mirage. I looked away and tried to assure myself that when I should look again the valley would be gone; but it was still there when I looked again, and I could see a trail winding down to it. I went to examine the trail, which was real enough, so I was sure I had seen Soda Lake, although it seemed to be in the wrong place. I immediately returned to the wagon to find I had been gone two hours and the boys were afraid I was overcome by the heat and were coming to look me up.

Cheered with my report of water and camps in sight, we all felt encouraged, and pushed the horses as fast as possible through the gap and down to the lake, where we found a man, a few chickens, a dog, and a mule. The man was raising vegetables. Just think of it, in a valley in the Soda Mountains! The lake was not Soda Lake after all, but Lake Crucero. He told us Soda Lake was dry, that it was seven miles east, and that there was no way to get there except through the deep sand, and that when we got there we would be nowhere.

When we asked him about the trail the prospector had told us of he said that it had been abandoned years ago; the water holes had dried up and, unless we were camels, we could never get through that way to Las Vegas. We were not surprised at this; in fact, we had begun to think that something was wrong with our old prospector’s directions, as it did not seem possible any sane person would ever attempt such a desert. This man was not very talkative, but on being pressed to advise us how he would go to Las Vegas he answered that he wouldn’t go, which reminded me very much of the old saying, “If you ever go to Arkansas, don’t go.” We tried another more sensible question and asked him how it would be possible to go by wagon, and in reply he said that it would be possible, if our team held out, to drive southeast about seven miles to the Salt Lake Railroad and follow it to Kelso, about thirty miles. We could get water at the section houses and if we could make thirty miles he thought we would be through the worst of the sand. As there was nothing else to do, unless we went back, we took his advice, and, after watering the horses and filling our barrels, we retraced our trail about three miles and camped at 7 P. M. in the open desert again, under a full moon. If we had not been so tired we could have enjoyed the night, but we were worn out by the heat and sand, and, thankful for the cool evening, we turned in and slept soundly.

Monday morning, May twenty-third. “Seven miles southeast over the sand to a section house on the railroad,” were our last instructions of the night before, and I am sure it was all of that, for although we started early, it was noon before we got there. The horses were worn out, our water was gone, and yet it was surprising how we cheered up when we came in sight of the section house, and how soon we forgot all our troubles after we had filled ourselves and animals with water and eaten our lunch.

After filling our barrels with water and looking at the railroad track and section house, we felt we were safe for the time being at least. Then it was we thought of Knowles and his advice to stick by the railroad track and if we could not pull through the sand to drive on the railroad track. Should we try it? There seemed to be no other alternative. It was about twenty-three miles to Kelso and our team was tired out. The last day and a half had taken all the life out of them. Our feed was running short and we couldn’t possibly get to the next water station unless we did try it.

Up we went, and an odd sight we must have presented driving over the ties, bumping along at a snail’s pace, but at that we managed to make about five miles when we came to a few bunches of Grama grass growing in the sand, and we promptly drove off the track. We had two reasons for doing this. One was on account of the feed this afforded the horses, and the other was that we figured the train we had been told of was due about this time, as it went up to Las Vegas at night and back in the morning, and we had to pick out a favorable place to get off the track, which was more desirable than being pushed off by the cars.

Here we turned our horses loose for the first time, thinking they were too tired and hungry to leave the bunch grass, and we were right. They didn’t leave that grass, and when it came time to turn in I just hobbled Dixie to be on the safe side. After this we hardly ever tied up our horses unless we were near a town or in a stock country where they might be enticed away by other horses, but before our trip was over even this was unnecessary, as we found they could not be driven very far away from the wagon. In fact, any horse we were not using would follow the wagon like a dog.

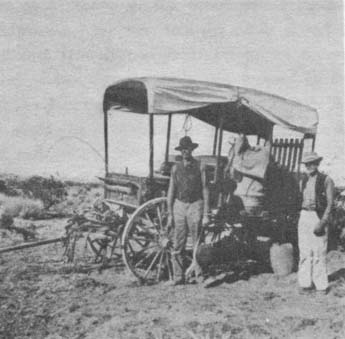

A DESERT CAMP

Our camp was in sight of three immense sand hills in a section of the desert called the Devil’s Playground. We were told these hills moved about and that sand storms were of frequent occurrence here. After supper, although it was nearly as light as day, the wind sprung up and we were doubtful about the advisability of turning in, but finally did so.

The heavens were a wonderful sight. The stars seemed to hang low and were more brilliant than usual. A comet with a long tail was plainly seen in the west, and the moon was rising over the sand hills. We began to speculate on the comet and, as the moon got above the sand hills and the wind freshened, the most remarkable thing happened--the sand hill began to move toward us! It kept getting closer, obscuring the moon, until it had moved up far enough to shut the moon from our sight entirely. We jumped up and each one of us was about to take a horse and ride for his life, when the Doctor laughed and said, “It is an eclipse of the moon. Don’t you see it’s coming out on the lower side again?” and we rolled over laughing at our fright, each claiming that he had known it was an eclipse all the time.

Later we found the comet we had seen was the famous Halley’s Comet and were sorry some of our astronomers had not been with us, as probably very few of them had an opportunity of seeing both the eclipse of the moon and the comet under such favorable circumstances.

We go to sleep looking at the heavens and in the morning, after the train has gone by, we start east again. We come to a section house about a mile down the track, at which we find a section foreman. He tells us it is twenty miles to Kelso, and the sand is “just as deep as you can stick down a cane.” This is not very encouraging, but we keep on the track, and finally, near time to make camp for the night, we reach Glasgow, another section house, where we find a water car.

We had to drive off the track here to get by the switches, and pulled through the sand up to the water car in front of the section house. We very nearly put the horses out of business, so to speak, pulling only a hundred yards at a time, but got all the water we wanted.

The foreman told us we could not drive on the track any farther as we were cutting up the ties and the oil which held the sand down. We told him that suited us; we wanted to be boarded until he could get a car and haul us out, and that we were about out of horse feed. He admitted that we could not pull through the sand and if we could not drive on the track we would have to stay there, but, as the railroad was not open for regular business and he had no facilities for feeding us, he changed the subject by asking us if we had got what water we wanted. When we told him we had, he said, “Why don’t you fellows go on then?” which we promptly did, after thanking him for the water.

We made only about two miles more before camping for the night, and were still thirteen miles from Kelso. It did not seem possible that we could have made only about eight miles that day, but as I looked back over the road and remembered the number of times we had driven off the track to get around trestle work, and how hard we had labored to get back on again, and how slow we had to go to keep from jolting our wagon to pieces, I concluded that there was sufficient excuse and only hoped the horses’ shoulders would not get sore with the jerking before we could get off the railroad for good. Besides, we must get to a town soon as we are about out of feed for the horses. With a firm determination to reach Kelso the next day we rolled up in our blankets and went to sleep looking at the stars.

Wednesday, May twenty-fifth. We were ready to make an early start this morning, but did not dare drive on the railroad track until after the train had gone by, and so had to wait until 8 A. M. Then we started out and luckily met a section foreman who gave us some good advice. He told us we would soon come to a wash on the north side of the track where we would probably find easier pulling than on the track, and he told us just how to get to it. He also told us we were only three and a half miles from his section house and that from there the going was better, and we would be within five miles of Kelso.

Incidentally, he said the Superintendent had dropped him a note telling him to get our names and to order us off the track. He said he would do neither. He was glad to see we had come that far alive and hoped we would get through O. K. He said the first chance he had to get out himself he would go too, and if any one had been kind enough to tell him about the country first, he never would have come.

Thanking him for his advice we drove along until we came to the jumping-off-place he had indicated, and after a hard pull found ourselves in the wash where it was possible for the horses to make fairly good headway, and soon reached Flynn, the section house. Here, after eating lunch and while the horses rested, Doc and I did some prospecting to find the best way into Kelso.

To follow the railroad was impossible on account of the sand, and we could not drive on the track on account of trestle work, so we went north to a mesa and discovered a trail coming down from above, the first trail we had seen in about sixty miles. Climbing up we found it well-defined, leading off down grade to Kelso, with the town itself in sight. A hard trail, and Kelso, for a minute, was enough to make us forget our troubles, but I knew how tired the horses were and I said, “Doc, we can never pull that wagon over here and up this hill.” Doc didn’t agree with me. He thought we could do it. We did by slow stages reach the foot of the hill and, with Doc and Bob pushing, got up and on to the trail. Here we took Dixie out of harness, as all Kate and Bess would have to do was to walk leisurely into town (about five miles), mostly down grade.

“Well, Doc,” I said, “you won; we got up.”

“Yes,” said Doc, still a little out of breath, “but I am not making any more bets on this mare”--holding Kate by the head--“she is bleeding at the nose and I believe she is going blind. What are we going to do?”

“Any danger of her bleeding to death?” I inquired.

Now Doc is not especially strong on horse diseases but he knows symptoms, and when he looked up and said, “No, she is just naturally done,” I felt relieved.

“What are we going to do,” I repeated, “going to Kelso, Doc? Better climb up and ride for a change.”

The drive into Kelso the afternoon of May twenty-fifth was especially fascinating. We were on a good hard trail and had only a few miles to go, and cares seemed to have rolled away. We could look at the scenery and talk intelligently about it; we became wildly enthusiastic over the Granite Mountains to the south of us, and the big sand hills to the southwest,--called “The Devil’s Playground,”--under which we had camped a few nights before, and where we had seen the total eclipse of the moon. Just beyond the Granite Peak was Old Dad Mountain. Our trail lay down the middle of this wide valley, flanked by the Providence Mountains on the south, and desert hills on the north. The colors were changing all the time and the air was so clear that we could see as far as--well, you could see as far as you could see. That is a safe statement and saves mileage, which every traveling man will appreciate. We had seen some wonderful views during the past few days, but perspiration and scenery did not create enthusiasm; besides, we were worried then. But I think as we rode quietly down upon this little desert town, the spirit of the desert must have taken possession of us, and things looked different to us from that time on.

I think we were all somewhat surprised not to see a delegation coming out to meet us, but, after we got acquainted with the town, we found the reason easy enough to explain. The little town had grown smaller from the time we saw it, five miles away, until we got into it. If it had been any farther away when we first saw it, I doubt if we could have discovered it when we got there. This phenomenon may be of some use in determining the causes of mirages.

There were apparently only two men in town; the hotel keeper and saloon man, who greeted us from the shady end of the porch, advised us that the storekeeper, who had a bale of alfalfa hay in the freight house of the railroad, might be persuaded to let us have it if properly interviewed. We interviewed him properly and procured it. He was the second man. He was also the postmaster and sheriff and game warden. He had married a Los Angeles girl and they had a bungalow next to the store, some flowers and some fruit trees, and a shed and a corral behind, making four buildings on the north side of the railroad track. This was the town proper. The balance of the town on the other side of the railroad track did not count for much in a desert scene. There was, in addition to the railroad station, an eating house, a repair shop, water tank, and a few railroad houses for the employees to live in.

This was Kelso as we saw it, a desert water station at the foot of the grade on the Salt Lake Railroad. There were eighty miles of sand and desert west of it that we knew, and we concluded there could be nothing worse east of it, so we were prepared to take things easy for a day or two and rest up our horses before going on.

We patronized the railroad lunch counter and visited with Fred Rickett, the postmaster, who gave us a great deal of interesting information about the country. He told us about a spring of water he had about six miles from town, up in the mountains, and how the mountain sheep came there to drink, as it was the only water for miles. He expects some time to pipe it down to town and irrigate a tract of land. At present he raises his vegetables up there. He took quite a fancy to Tuck, who never left the wagon all the time we were in town. I find the following memo in my diary for the day spent in Kelso, which shows how exciting the day really was:

THE BUSINESS SECTION OF KELSO, CALIFORNIA

“Thursday, the twenty-sixth. Put in day here in Kelso talking to Rickett, making a few repairs to wagon, tightening screws, etc. Have no grain, but put all alfalfa we could inside the horses. Doctored Kate’s shoulder, neck, and foot. Wrote a few letters and postals. Rickett, who has prospected all over this part of the country, says the best way to get here from Daggett is via the Santa Fe Railroad to Amboy and then up over the mountains between Granite and Old Dad, on horseback. A light wagon could make it. It is not so very much better than the way we came. A prospector came in with two burros from twelve miles up in the mountains for mail and supplies. Rickett says he has the only store for eighty miles west, forty miles south, thirty miles north, and twenty miles east.

“He told us he had two brothers in the war and how one of them came very near shooting the other; one was on the North and the other on the South. The one under Lee was a sharpshooter and one night killed four sentries at a single post, but got so hungry he could not wait for the fifth to show himself so called out to him for something to eat. The reply came back: ‘Can of lard and some corn meal,’ in a voice he recognized as his brother’s. So he went back and got Lee to transfer him. (You may have heard this story before, but you appreciate the significance of it more when you hear it told by one of the brothers.)

“Got all of our meals at the restaurant here at thirty-five cents per. Turned in early, all ready for an early start. So far, since leaving San Bernardino, we have met no one on the road. One auto passed us going into Hesperia and we met one auto going out of Victorville. Not a snake sighted, a very few small jacks, and a few very large land tortoises. During the early spring or winter one can get through here better, although, of course, the weather is not so good. Rickett said last winter a young lad came through driving a buggy and a two-year-old colt, with only a dog for company. He assumed he got through, but he never had heard.”

This extract from my diary would seem to show that the only item of news which a newspaper correspondent could have wired his home paper as happening that day (supposing there had been any newspaper correspondent), would have been about as follows:

“Kelso, May 26. We were interrupted to-day by Bill Baxter who came down from his mine over in the Providence Mountains for mail and supplies. Bill says it is mighty dry this year in the mountains. Providence, Bill said, didn’t do as much this year as usual. ‘Come again, Bill, we don’t mind being interrupted.’”

We leave town early with a new arrangement of horses--Dixie beside Bess, and Kate walking behind. Doctor questions how long Dixie, who is so much smaller than Bess and not of the work-horse type, will be able to pull her end, but we leave that question; in fact, we haven’t decided it yet. We are off for Las Vegas, Nevada. We have a road to follow among desert hills and valleys, up and down hill, but find no water except at a railroad water car or cistern. The first day we pass Cima, where we got a bale of wheat hay and water. We make about twenty-two miles, which seems more like progress, especially after using up six days to come eighty miles. Here there are more rocks in the hills and more vegetation. Forests of Joshua Palms (giant cacti) grow on the higher slopes on the north side. We never saw them growing on land sloping to the south or at low altitude.

Our first camp was among the giant cacti, which we used as hitching posts for the horses while feeding. That night we heard a mountain lion squall, but Tuck evidently did not think he was near enough to worry about. Tuck is getting to be an ideal camp dog. He can be trusted to stay around camp and will not leave the wagon on any excuse if we are not about, so we feel perfectly safe, no matter where we are, in the belief that our tools, harness, and odds and ends (so essential to us on this sort of a trip) will not be mislaid by visitors or stolen.

The next morning we were at Leastalk, thirteen miles, by 9 A. M., and Kate was feeling so good we let her pack the saddle and Bob rode her. Here at Leastalk we got half a sack of grain (all they had) and started up the Ivanpah Valley to Ivanpah, seven miles. We reached there at noon. How any one can reach a place that isn’t, I can’t say, but as I said before, we got to the place which, on the map, said “Ivanpah,” but which there, said nothing.

On looking at the map I saw that a railroad track ran from here by various crooks and turns to Bengal on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. We finally discovered the track, and also a few work cars, and met the foreman and his crew of Mexicans working on the right-of-way.

JOSHUA PALM OR GIANT CACTUS

“What are you going to do?” said I to the foreman, thinking he might be the forerunner of a building gang who were to build a town here or extend the railroad.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Don’t know? Haven’t you any orders?” I asked, surprised.

“Won’t get any until they pull me back to-morrow. This is the end of the road, isn’t it?” he asked.

I was about to remark, “It certainly is,” when it occurred to me that I wasn’t supposed to know as much about a railroad as a real railroad man like the foreman of a gang of Mexicans, so I replied cautiously, “Well, I don’t know. I thought this might be the beginning of a railroad; if this is the end of one, what was the use of building it?”

He looked at me curiously for a minute. It certainly was hot there in the sun and he had no way of knowing we had just been to water, so he said, “You had better take a drink. You can have what you want from my tank car; and you had better fill your barrels too; no knowing when you will get any more.”

After filling our barrels we ate lunch and tried to get a shot at a coyote that had crossed the trail just below us, but we would have been cooler if we had let him go without trying. From about noon to four o’clock it is pretty hot in the sun, but we were now where we could ride,--Doc and I and Tuck in the wagon under the canvas top, and Bob on Kate. Sometimes during the middle of the day we would all ride in the wagon, and at other times would take turns riding the saddle, so as to make it easier on the team horses.

We had come twenty miles before lunch so did not start very early. When we did, however, we headed right northeast for Dry Lake and got nearly across before we decided to camp, Kate having lost a shoe. We saw another coyote just before reaching the lake, but as usual our 30-30 wasn’t handy to the fellow who saw him first, and that is sufficient explanation in that country where everything is the same color as the coyote and little draws and gulches are handy.

This Dry Lake was just that and nothing more. At times during the year, or some years, there must be water here, but I guess it is not often. It was really a wonderful place to look at, flat as a floor, almost as smooth as a tennis court, hard as a board, creamy white in color, and I should say seven miles long and about two and a half miles across at the widest part, surrounded by sage brush and grease-wood. I should hate to cross it in the middle of the day--it must be awfully hot; but at night it would make a racecourse for horses or automobiles, if one could only scrape up an audience.

We camped at 6:30 P. M. that evening on the lake bed, where it was smooth and cool. Our coal oil stove was proving a great success in a land without wood, and even where there was any, it saved time, as did our water barrels, and our fireless cooker saved coal oil, and gave us better oatmeal, prunes, and rice than we could have had at home.

The next morning before starting we put a new shoe on Kate; that is, Doc blacksmithed an old one we had on hand and I nailed it on, and the surprising thing about it was that it stayed on.

We got off the lake bottom and on towards Jean, Sunday morning, May twenty-ninth. We had made thirty miles Saturday, but that was an easy day, which, with the level lake bed to walk over in the evening, was like driving on Michigan Avenue. No such good fortune awaited us from now on. It was up grade and hard pulling all the way to Jean, but here we got grain and wheat hay, so, pulling out from the store about a mile, we fed grain and hay, and then turned the horses loose to graze until they were completely filled up before we started on.

Kate’s shoulder is better and her cracked heel is about well. The film is going off her eye and I think very soon she will be able to take her place with Bess again and let Dixie pack the saddle. Dixie has pulled her end so far very well, although not being used to a collar her neck is getting sore, and I can see Kate will not be well enough to wear a collar any too soon.

At night we conclude we have made about twenty-two miles up grade, and at a guess figure we are twenty-three miles from Las Vegas, mostly a downhill pull, so we think it will be an easy trip for the morrow.

It had not been unbearably hot up to this time and the nights were simply glorious--clear and cool--and we were congratulating ourselves on having such fine traveling weather. My memorandum book notes a change in the weather the next day, May 30, Decoration Day, and I give my memorandum here verbatim:

“Started from camp at 5:45 A. M. for Las Vegas, the last lap of our first real desert experience. We have been ten days in crossing from Daggett, California, to Las Vegas, Nevada, probably one hundred and fifty miles, so we have averaged fifteen miles, including stop of a day at Kelso and going up to Lake Crucero by mistake, which put us back two days, so we could have made it in seven days if we had not got lost and pulled down the team in getting out. We drive up dry rivers and down dry rivers, over sand and rocks, mostly up hill, because the sand is usually so deep the wagon pulls on the team going down grade. We have found no cows and believe, with the old pioneer, that this country contains more rivers and less water, and you can see farther and see less, than any other part of the United States.

“Coming into Las Vegas this morning we saw our first artesian well, forty inches, and learned they were now going to have one on each section of this desert slope. Some time we are going back to see if they do and how much good it does them. The soil looked too full of alkali to suit me. However, while this well made quite a stream, it mostly evaporated or sunk into the ground, as it seemed to do very little good.

“We reached the end of the down grade part of the trip at 11 A. M., stayed near this well for lunch, and then at 1:30 made a start on the eight-mile pull up through the sand, arriving at Las Vegas at 4:45 P. M., after the hardest eight miles we ever made, on account of heat. The wind was in our faces, but how hot it was we did not know. It most blistered us--probably about 115 to 120 degrees, as we found it 107 in the hotel after we arrived.

“It certainly was hot. We took a drink every fifteen minutes and watered the horses every hour, besides putting water on Tuck’s head and back to keep him from being overcome. We put team in shed of livery, the only one in town, and went to a hotel.

“No mail, as Decoration Day was a holiday and postoffice closed.”

The above memorandum says nothing about scenery, nothing about Las Vegas itself, and nothing even about the road, so I guess we were not long on enthusiasm about that time. We slept in beds that night, but hot ones, and we laid the heat to the town and the hotel. The next day we got our mail, wrote home, and after getting off all the letters we went over and, as Doc said, “patched up the horses.” We got a hose and soaked their feet, and after a general clean-up I think they felt better. It was no cooler, however.

In the afternoon I took all the horses around to be shod. The blacksmith said if I would help him, he would shoe them, but not otherwise, as it was too hot. I told him it was not very hot, but I would help him just the same, so we went at it. Before long the canteen ran dry, so I went and filled it and hung it in the shade in a handy place. The blacksmith kept complaining about the heat. He said it was just as hot every year there, but hotter when you had to work. He wanted me to go into the next building and look at a spirit thermometer and let him know how hot it really was. I did go, and looked at the thermometer, but when I found it registered 126° over there in the shade I concluded I best keep it to myself or the blacksmith would quit work, so when I got back I said, “Well, it is pretty hot; it is 120.”

He didn’t say anything for a few minutes, but finally as he held a shoe in a tub of water to cool he looked over at me and said, “Guess this country is getting me down. I didn’t use to mind 120 before. When it gets up to 130 and 135 I just lay off. About 120,--well, I guess I will take a drink and go look at that thermometer.”

I could see myself finishing that job alone and watched him narrowly as he went over to take a look at the thermometer. On his way back I could see he was not feeling as bad as I had expected he would, and was surprised to hear him say, in a more cheerful tone than I had been able to get out of him before, “Well, I thought it must be over 120; why, it is 126--no wonder I was hot. Guess you can’t fool me on weather in this country. Now let’s finish this job before it gets any hotter. I bet I don’t work to-morrow.” And we kept at it until all the horses were shod.

Doc came over for a few minutes to see how we were getting on. He picked up a horseshoe from the floor with his bare hand, and dropped it as if it were red hot. He seemed to think we were putting up a job on him, and when I said it was a cold one he said I was joking, but after testing a few more he said that a blacksmith shop was no place to loaf in, and started back to the hotel. We finished the shoeing and returning to the hotel talked over things, especially the heat, and decided we had rather be out on the desert than in town. We concluded it must be cooler at night out there and not so dusty during the day.

Las Vegas ordinarily would have about fifteen hundred people when the railroad is running, but now, I should say, had only about eight hundred. They have a nice railroad station, but that is about all. The stores are not especially interesting and the whole town is on the main street, facing the railroad station, and one other street running at right angles to it.

Through the ownership of the old Stewart Ranch the railroad company owns the water and all the irrigatable land about Las Vegas, except what may be developed from a recent discovery of water, eight miles below town, by sinking of wells. This, however, I don’t have much faith in as being of sufficient flow to any more than raise garden truck, but why anybody should want to live in a place that on provocation can get as hot as 135 degrees in the shade (and no shade), simply because they could possibly raise garden truck, I am unable to see.

We have decided to start out again. We have our grub box filled, and our oil can; also grain for the horses and some alfalfa hay. It did not cool off much last night and is still hot to-day, a good stiff breeze blowing, but in spite of the breeze, it is 105 in the shade and, if you open your mouth, it dries out before you get a chance to close it. We have faith that the desert is better than the town, and not knowing the character of the country ahead (no one being able to enlighten us), we take a chance and start, leaving town at 3 P. M., June 1, having spent practically two days here. We are bound for Bunkerville by way of Moapa.

WE STOP FOR WATER

Leaving Las Vegas at 3 P. M., with a hot wind at our back, we drove through the Stewart Ranch, which, with its cottonwood trees, patches of alfalfa, and running water, looked awfully good to us. Leaving the ranch we nearly drove over a bobcat, but we were too hot to take much interest in any game at that time. Immediately after we had reached the long valley running north from Las Vegas, it began to get cooler, and that night we slept under blankets again.

We got an early start the next morning and by 8:30 A. M. had driven the twelve miles to the top of the divide, and by noon reached a railroad water well at Dry Lake. The accompanying picture shows the spot. There is nothing here; in fact, if we had not had explicit directions from a railroad man we wouldn’t have found the well. We lunched, and then at 4 P. M., having found some bunch grass, we camped and turned the horses loose.

We are glad we did not stay at Las Vegas any longer. It may be cooler there now, but we know it is here, and we are happy. Dixie still holds out, so have not tried Kate in harness yet. We are in a bare mountainous country of the same desert variety which we have been traveling through for so long, but in spots the trail is good and in others it is bad. It seems strange not to meet a soul driving through the country. Still, as there does not seem to be any people in the country, I assume there is no one to travel.

We were computing to-day how much weight we have in our wagon, including water barrels, half full, hay and grain and two people, and set it down as fifteen hundred pounds, which, with the wagon, springs and cover added, makes a good load for two ordinary horses, but we are beginning to think that our horses are more than that.

OUR FIRST CAMP EAST OF LAS VEGAS

The next morning we were off for Moapa. We had another divide to cross and then down into California Wash for eight miles to the Big Muddy. This California Wash was a terror. I can’t forget its heat and its sand and rocks, and while we started in cheerfully enough, before we got out the boys were both walking and I was driving the team fifty yards only to a stop. We came out suddenly on to the banks of a clear little stream running out of Meadow Valley, and forgot about our troubles, or those other people had had at the time of the Meadow Valley massacre, and turned everything loose.

We had a fine camp here, the first stream of water since leaving Daggett on the Mojave three weeks ago. We boys washed up, including our clothes, and shortly after lunch, while the wash was on the line, I rode Kate up to Moapa, two miles, and got a sack of feed, as we found we could save four miles by not going into Moapa.

We hit the stage road near our camp that evening and started east for Bunkerville. Tuck never had so much fun as he seemed to have in that little stream, and on his account, as well as our own, we hated to leave, but at 5 P. M. we moved on to a ranch house at the foot of a range of mountains we had to go over, and camped there for the night, so as to be ready to make the climb in the morning before it should get too hot. These mountains, I think, were the south end of a small range called the Mormon Mountains, although everything in this country seems to be either hills or mountains, but they haven’t been discovered yet or else the folks who made up the maps were out of names. They seem to be long on country and short on names.

At this ranch house, which was occupied by a new man, or tenderfoot, we found an old man lying on a bed by the window and a young man fanning him to keep away the flies. On inquiring as to whether he was sick, we were informed he had been hurt in a runaway the night before, so while Bob and I were unpacking, Doc took his bag and went up to see what he could do for him, and we were left to speculate on the case and get supper while he was gone. Doc has a way of making friends whether they are sick or well, and we usually send him out for a parley in any emergency. This, however, was his first case of personal injury on the trip, so I knew he would not be back very soon.

It was late, as I expected, when he returned and we got the whole story while eating supper. It seems the old fellow lived about eight miles down the Muddy River, had been to Moapa with a load of stuff and had stayed too long, so that he was a little the worse for whiskey. It was dark when he started for home and he had a mean team, which, when his brake guard came off and he fell on them, promptly kicked him into insensibility and ran off, leaving him to come to during the night, unable to see or tell where he was. He had wandered about until he came to the ranch fence and was found about daylight by one of the boys of this ranch, who took him in, and when they found out who he was they sent for his son-in-law, the man we saw fanning him, and the doctor who lived at Logan. They had come up and taken him in charge, but the doctor evidently had come unprepared or else, as Doc said, never was prepared, and he had done poorly by him and left, promising to be back as soon as he could get some necessary medicine and bandages. Doc said if we hadn’t just happened along the man would have died of blood poisoning, sure. Doc had cleaned him up, dressed his wounds, and left him asleep.

We filled our water barrels just half full that night and the next morning were off up the mountain, driving spike team for Bunkerville, thirty miles away, and twenty-seven miles to water. Before leaving Doc made a call on his patient; refused any compensation for his services, as usual, and tried to satisfy the son-in-law by telling him it was against the rules of the profession for a doctor to collect from another doctor’s patient. He would collect from the doctor himself. I couldn’t hear exactly what the man said in reply and did not ask Doc, but thought he said something like this: “Well, you fellows are a queer bunch, but I sure am thankful and wish you luck.”

It was Saturday morning, June fourth, when we left the ranch camp on the Muddy River, and we had a three-mile pull nearly straight up before reaching the mesa. From here we had a grand view, which reminded me somewhat of the view at the Grand Canyon in miniature. The valley of the Muddy lay beneath us and had widened out in green spots here and there, where the ranchers were raising alfalfa, but the spots were so far below they didn’t look bigger than flower beds. Behind us stretched the dry, hard mesa, over which our road led to Bunkerville, a Mormon settlement on the Virgin River.

There was nothing of interest in going over this stretch of about twenty-five miles except the stage which we met, carrying the mail to Moapa. We could see the dust raised by the horses a long way off and finally hailed the driver as he passed. Not that we had anything to say to him, but as the Irishman would say, “just for conversation.” He drove two horses and led one; had a two-seated, canopy-topped wagon, no merchandise or passengers, just a mail bag and a bundle of alfalfa hay. He said he came over one day and went back the next. Told us to make the ford before dark and to make it quick, and then he drove on. This was quite an event for us as it was the first vehicle we had met on the desert highway, so I made a note of it.

After that nothing happened until we came to the edge of the mesa and started down again. This took some careful driving to get down safely with so heavy a wagon, but our brake, of which up to date we had had little use, worked admirably, although I concluded I could adjust it a little better, and did so later on.