The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Salem witchcraft, The planchette

mystery, and Modern spiritualism, by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Phrenological Journal

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Salem witchcraft, The planchette mystery, and Modern spiritualism

with Dr. Doddridge's dream

Author: Harriet Beecher Stowe

Phrenological Journal

Release Date: March 12, 2013 [EBook #42318]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SALEM WITCHCRAFT ***

Produced by eagkw, Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

HISTORY

OF

Salem Witchcraft:

A REVIEW

OF

CHARLES W. UPHAM’S GREAT WORK.

FROM THE “EDINBURGH REVIEW.”

With Notes,

BY THE EDITOR OF “THE PHRENOLOGICAL JOURNAL.”

NEW YORK:

FOWLER & WELLS CO., PUBLISHERS,

753 BROADWAY.

1886.

BIGOTRY. Obstinate or blind attachment to a particular creed; unreasonable zeal or warmth in favor of a party, sect, or opinion; excessive prejudice. The practice or tenet of a bigot.

PREJUDICE. An opinion or decision of mind, formed without due examination of the facts or arguments which are necessary to a just and impartial determination. A previous bent or inclination of mind for or against any person or thing. Injury or wrong of any kind; as to act to the prejudice of another.

SUPERSTITION. Excessive exactness or rigor in religious opinions or practice; excess or extravagance in religion; the doing of things not required by God, or abstaining from things not forbidden; or the belief of what is absurd, or belief without evidence. False religion; false worship. Rite or practice proceeding from excess of scruples in religion. Excessive nicety; scrupulous exactness. Belief in the direct agency of superior powers in certain extraordinary or singular events, or in omens and prognostics.—Webster.

The object in reprinting this most interesting review is simply to show the progress made in moral, intellectual, and physical science. The reader will go back with us to a time—not very remote—when nothing was known of Phrenology and Psychology; when men and women were persecuted, and even put to death, through the baldest ignorance and the most pitiable superstition. If we were to go back still farther, to the Holy Wars, we should find cities and nations drenched in human blood through religious bigotry and intolerance. Let us thank God that our lot is cast in a more fortunate age, when the light of revelation, rightly interpreted by the aid of Science, points to the Source of all knowledge, all truth, all light.

When we know more of Anatomy, Physiology, Physiognomy, and the Natural Sciences generally, there will be a spirit of broader liberality, religious tolerance, and individual freedom. Then all men will hold themselves accountable to God, rather than to popes, priests, or parsons. Our progenitors lived in a time that tried men’s souls, as the following lucid review most painfully shows.

S. R. W.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The Place | 7 |

| The Salemite of Forty Years Ago | 8 |

| How the Subject was opened | 9 |

| Careful Historiography | 10 |

| The Actors in the Tragedy | 12 |

| Philosophy of the Delusion | 12 |

| Character of the Early Settlement | 13 |

| First Causes | 15 |

| Death of the Patriarch | 16 |

| Growth of Witchcraft | 17 |

| Trouble in the Church | 18 |

| Rev. Mr. Burroughs | 19 |

| Deodat Lawson | 20 |

| Parris—a Malignant | 20 |

| A Protean Devil | 21 |

| State of Physiology | 22 |

| William Penn as a Precedent | 22 |

| Phenomena of Witchcraft | 23 |

| Parris and his Circle | 25 |

| The Inquisitions—Sarah Good | 26 |

| A Child Witch | 27 |

| The Towne Sisters | 28 |

| Depositions of Parris and his Tools | 31 |

| Goody Nurse’s Excommunication | 35 |

| Mary Easty | 36 |

| Mrs. Cloyse | 38 |

| The Proctor Family | 40 |

| The Jacobs Family | 41 |

| Giles and Martha Corey | 42 |

| Decline of the Delusion | 44 |

| The Physio-Psychological Causes of the Trouble | 45 |

| The Last of Parris | 47 |

| “One of the Afflicted”—Her Confession | 49 |

| The Transition | 50 |

| The Fetish Theory Then and Now | 51 |

| The Views of Modern Investigators | 53 |

| Importance of the Subject | 55 |

CONTENTS OF THE PLANCHETTE MYSTERY.

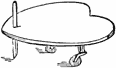

| What Planchette is and does (with review of Facts and Phenomena) | 63 |

| The Press on Planchette (with further details of Phenomena) | 67 |

| Theory First—That the Board is moved by the hands that rest upon it | 70 |

| Theory Second—“It is Electricity or Magnetism” | 71 |

| Proof that Electricity has nothing to do with it | 78 |

| Theory Third—The Devil Theory | 79 |

| Theory of a Floating Ambient Mentality | 81 |

| “To Daimonion”—The Demon | 83 |

| “It is some principle of nature as yet unknown” | 85 |

| Theory of the Agency of Departed Spirits | 85 |

| Planchette’s own Theory | 89 |

| The Rational Difficulty | 92 |

| The Medium—The Doctrine of Spheres | 93 |

| The Moral and Religious Difficulty | 98 |

| What this Modern Development is, and what is to come of it | 102 |

| Conclusion | 105 |

| How to work Planchette | 106 |

SPIRITUALISM.

DR. DODDRIDGE’S DREAM.

The name of the village of Salem is as familiar to Americans as that of any provincial town in England or France is to Englishmen and Frenchmen; yet, when uttered in the hearing of Europeans, it carries us back two or three centuries, and suggests an image, however faint and transient, of the life of the Pilgrim Fathers, who gave that sacred name to the place of their chosen habitation. If we were on the spot to-day, we should see a modern American seaport, with an interest of its own, but by no means a romantic one. At present Salem is suffering its share of the adversity which has fallen upon the shipping trade, while it is still mourning the loss of some of its noblest citizens in the late civil war. No community in the Republic paid its tribute of patriotic sacrifice more generously; and there were doubtless occasions when its citizens remembered the early days of glory, when their fathers helped to chase the retreating British, on the first shedding of blood in the war of Independence. But now they have enough to think of under the pressure of the hour. Their trade is paralyzed under the operation of the tariff; their shipping is rotting in port, except so much of it as is sold to foreigners; there is much poverty in low places and dread of further commercial adversity among the chief citizens, but there is the same vigorous pursuit of intellectual interests and pleasures, throughout the society of the place, that there always is wherever any number of New Englanders have made their homes beside the church, the library, and the school. Whatever other changes may[8] occur from one age or period to another, the features of natural scenery are, for the most part, unalterable. Massachusetts Bay is as it was when the Pilgrims cast their first look over it: its blue waters—as blue as the seas of Greece—rippling up upon the sheeted snow of the sands in winter, or beating against rocks glittering in ice; in autumn the pearly waves flowing in under the thickets of gaudy foliage; and on summer evening the green surface surrounding the amethyst islands, where white foam spouts out of the caves and crevices. On land, there are still the craggy hills, and the jutting promontories of granite, where the barberry grows as the bramble does with us, and room is found for the farmstead between the crags, and for the apple-trees and little slopes of grass, and patches of tillage, where all else looks barren. The boats are out, or ranged on shore, according to the weather, just as they were from the beginning, only in larger numbers; and far away on either hand the coasts and islands, the rocks and hills and rural dwellings, are as of old, save for the shrinking of the forest, and the growth of the cities and villages, whose spires and school-houses are visible here and there.

Yet there are changes, marked and memorable, both in Salem and its neighborhood, since the date of thirty-seven years ago. There was then an exclusiveness about the place as evident to strangers, and as dear to natives, as the rivalship between Philadelphia and Baltimore, while far more interesting and honorable in its character. In Salem society there was a singular combination of the precision and scrupulousness of Puritan manners and habits of thought with the pride of a cultivated and traveled community, boasting acquaintance with people of all known faiths, and familiarity with all known ways of living and thinking, while adhering to the customs, and even the prejudices, of their fathers. While relating theological conversations held with liberal Buddhists or lax Mohammedans, your host would whip his horse, to get home at full speed by sunset on a Saturday, that the groom’s Sabbath might not be encroached on for five minutes. The houses were hung with odd Chinese copies of English engravings, and furnished with a variety of pretty and useful articles from China, never seen elsewhere, because none but American traders had then achieved any commerce with that country but in tea, nankeen, and silk. The[9] Salem Museum was the glory of the town, and even of the State. Each speculative merchant who went forth, with or without a cargo (and the trade in ice was then only beginning), in his own ship, with his wife and her babes, was determined to bring home some offering to the Museum, if he should accomplish a membership of that institution by doubling either Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope. He picked up an old cargo somewhere and trafficked with it for another; and so he went on—if not rounding the world, seeing no small part of it, and making acquaintance with a dozen eccentric potentates and barbaric chiefs, and sovereigns with widely celebrated names; and, whether the adventurer came home rich or poor, he was sure to have gained much knowledge, and to have become very entertaining in discourse. The houses of the principal merchants were pleasant abodes—each standing alone beside the street, which was an avenue thick-strewn with leaves in autumn and well shaded in summer. Not far away were the woods, where lumbering went on, for the export of timber to Charleston and New Orleans, and for the furniture manufacture, which was the main industry of the less fertile districts of Massachusetts in those days. Here and there was a little lake—a “pond”—under the shadow of the woods, yielding water-lilies in summer, and ice for exportation in winter—as soon as that happy idea had occurred to some fortunate speculator. On some knoll there was sure to be a school-house. Amid these and many other pleasant objects, and in the very center of the stranger’s observations, there was one spectacle that had no beauty in it—just as in the happy course of the life of the Salem community there is one fearful period. That dreary object is the Witches’ Hill at Salem; and that fearful chapter of history is the tragedy of the Witch Delusion.

Our reason for selecting the date of thirty-seven years ago for our glance at the Salem of the last generation is, that at that time a clergyman resident there fixed the attention of the inhabitants on the history of their forefathers by delivering lectures on Witchcraft. This gentleman was then a young man, of cultivated mind and intellectual tastes, a popular preacher, and esteemed and beloved in private life. In delivering those lectures he had no more idea than his audience that he was entering upon the great work and grand intellectual interest of his life. When he concluded the course, he was unconscious of having offered[10] more than the entertainment of a day; yet the engrossing occupation of seven-and-thirty years for himself, and no little employment and interest for others, have grown out of that early effort. He was requested to print the lectures, and did so. They went through more than one edition; and every time he reverted to the subject, with some fresh knowledge gathered from new sources, he perceived more distinctly how inadequate, and even mistaken, had been his early conceptions of the character of the transactions which constituted the Witch Tragedy. At length he refused to reissue the volume. “I was unwilling,” he says in the preface of the book before us, “to issue again what I had discovered to be an insufficient presentation of the subject.” Meantime, he was penetrating into mines of materials for history, furnished by the peculiar forms of administration instituted by the early rulers of the province. It was an ordinance of the General Court of Massachusetts, for instance, that testimony should in all cases be taken in the shape of depositions, to be preserved “in perpetual remembrance.” In all trials, the evidence of witnesses was taken in writing beforehand, the witnesses being present (except in certain cases) to meet any examination in regard to their recorded testimony. These depositions were carefully preserved, in complete order: and thus we may now know as much about the landed property, the wills, the contracts, the assaults and defamation, the thievery and cheating, and even the personal morals and social demeanor of the citizens of Salem of two centuries and a half ago as we could have done if they had had law-reporters in their courts, and had filed those reports, and preserved the police departments of newspapers like those of the present day. The documents relating to the witchcraft proceedings have been for the most part laid up among the State archives; but a considerable number of them have been dispersed—no doubt from their connection with family history, and under impulses of shame and remorse. Of these, some are safely lodged in literary institutions, and others are in private hands, though too many have been lost.

In a long course of years, Mr. Upham, and after him his sons, have searched out all documents they could hear of. When they had reason to believe that any transcription of papers was inaccurate—that gaps had been conjecturally filled up, that dates had been mistaken,[11] or that papers had been transposed, they never rested till they had got hold of the originals, thinking the bad spelling, the rude grammar, and strange dialect of the least cultivated country people less objectionable than the unauthorized amendments of transcribers. Mr. Upham says he has resorted to the originals throughout. Then there were the parish books and church records, to which was committed in early days very much in the life of individuals which would now be considered a matter of private concern, and scarcely fit for comment by next-door neighbors. The primitive local maps and the coast-survey chart, with the markings of original grants to settlers, and of bridges, mills, meeting-houses, private dwellings, forest roads, and farm boundaries, have been preserved. Between these and deeds of conveyance it has been possible to construct a map of the district, which not only restores the external scene to the mind’s eye, but casts a strong and fearful light—as we shall see presently—on the origin and course of the troubles of 1692. Mr. Upham and his sons have minutely examined the territory—tracing the old stone walls and the streams, fixing the gates, measuring distances, even verifying points of view, till the surrounding scenery has become as complete as could be desired. Between the church books and the parish and court records, the character, repute, ways, and manners of every conspicuous resident can be ascertained; and it may be said that nothing out of the common way happened to any man, woman, or child within the district which could remain unknown at this day, if any one wished to make it out. Mr. Upham has wished to make out the real story of the Witch Tragedy; and he has done it in such a way that his readers will doubtless agree that no more accurate piece of history has ever been written than the annals of this New England township.

For such a work, however, something more is required than the most minute delineation of the outward conditions of men and society; and in this higher department of his task Mr. Upham is above all anxious to obtain and dispense true light. The second part of his work treats of what may be called the spiritual scenery of the time. He exhibits the superstition of that age, when the belief in Satanic agency was the governing idea of religious life, and the most engrossing and pervading interest known to the Puritans of every country. Of the young and ignorant in the new settlement beyond the seas his researches have led him to write thus:

“However strange it seems, it is quite worthy of observation, that the actors in that tragedy, the ‘afflicted children,’ and other witnesses, in their various statements and operations, embraced about the whole circle of popular superstition. How those young country girls, some of them mere children, most of them wholly illiterate, could have become familiar with such fancies, to such an extent, is truly surprising. They acted out, and brought to bear with tremendous effect, almost all that can be found in the literature of that day, and the period preceding it, relating to such subjects. Images and visions which had been portrayed in tales of romance, and given interest to the pages of poetry, will be made by them, as we shall see, to throng the woods, flit through the air, and hover over the heads of a terrified court. The ghosts of murdered wives and children will play their parts with a vividness of representation and artistic skill of expression that have hardly been surpassed in scenic representations on the stage. In the Salem-witchcraft proceedings, the superstition of the middle ages was embodied in real action. All its extravagant absurdities and monstrosities appear in their application to human experience. We see what the effect has been, and must be, when the affairs of life, in courts of law and the relations of society, or the conduct or feelings of individuals, are suffered to be under the control of fanciful or mystical notions. When a whole people abandons the solid ground of common sense, overleaps the boundaries of human knowledge, gives itself up to wild reveries, and lets loose its passions without restraint, it presents a spectacle more terrific to behold, and becomes more destructive and disastrous, than any convulsion of mere material nature,—than tornado, conflagration, or earthquake.” (Vol. i. p. 468.)

All this is no more than might have occurred to a thoughtful historian long years ago; but there is yet something else which it has been reserved for our generation to perceive, or at least to declare, without fear or hesitation. Mr. Upham may mean more than some people would in what he says of the new opening made by science into the dark depths of mystery covered by the term Witchcraft; for he is not only the brother-in-law but the intimate friend and associate of Dr.[13] Oliver Wendell Holmes, Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Harvard University, and still better known to us, as he is at home, as the writer of the physiological tales, “Elsie Venner” and the “Guardian Angel,” which have impressed the public as something new in the literature of fiction. It can not be supposed that Mr. Upham’s view of the Salem Delusion would have been precisely what we find it here if he and Dr. Holmes had never met; and, but for the presence of the Professor’s mind throughout the book, which is most fitly dedicated to him, its readers might have perceived less clearly the true direction in which to look for a solution of the mystery of the story, and its writer might have written something less significant in the place of the following paragraph:

“As showing how far the beliefs of the understanding, the perceptions of the senses, and the delusions of the imagination may be confounded, the subject belongs not only to theology and moral and political science, but to physiology, in its original and proper use, as embracing our whole nature; and the facts presented may help to conclusions relating to what is justly regarded as the great mystery of our being—the connection between the body and the mind.” (Vol. i. p. viii.)

The settlement had its birth in 1620, the date of the charter granted by James I. to “the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay in New England.” The first policy of the company was to attract families of good birth, position, education, and fortune, to take up considerable portions of land, introduce the best agriculture known, and facilitate the settling of the country. Hence the tone of manners, the social organization, and the prevalence of the military spirit, which the subsequent decline in the spirit of the community made it difficult for careless thinkers to understand. Not only did the wealth of this class of early settlers supply the district with roads and bridges, and clear the forest; it set up the pursuit of agriculture in the highest place, and encouraged intellectual pursuits, refined intercourse, and a loftier spirit of colonizing enterprise than can be looked for among immigrants whose energies are engrossed by the needs of the day. The mode of dress of the gentry of this class shows us something of their aspect in their new country, when prowling Indians were infesting the woods a stone’s throw from their fences, and when the rulers of the community[14] took it in turn with all their neighbors to act as scouts against the savages. George Corwin was thus dressed:

“A wrought flowing neckcloth, a sash covered with lace, a coat with short cuffs and reaching halfway between the wrist and elbow; the skirts in plaits below; an octagon ring and cane. The last two articles are still preserved. His inventory mentions ‘a silver-laced cloth coat, a velvet ditto, a satin waistcoat embroidered with gold, a trooping scarf and silver hat-band, golden-topped and embroidered, and a silver-headed cane.’” (Vol. i. p. 98.)

This aristocratic element was in large proportion to the total number of settlers. It lifted up the next class to a position inferior only to its own by its connection with land. The farmers formed an order by themselves—not by having peculiar institutions, but through the dignity ascribed to agriculture. The yeomanry of Massachusetts hold their heads high to this day, and their fathers spoke proudly of themselves as “the farmers.” They penetrated the forest in all directions, sat down beside the streams, and plowed up such level tracts as they found open to the sunshine; so that in a few years “the Salem Farms” constituted a well-defined territory, thinly peopled, but entirely appropriated. In due course parishes were formed round the outskirts of “Salem Farms,” encroaching more or less in all directions, and reducing the area to that which was ultimately known as “Salem Village,” in which some few of the original grants of five hundred acres or less remained complete, while others were divided among families or sold. Long before the date of the Salem Tragedy, the strifes which follow upon the acquisition of land had become common, and there was much ill-blood within the bounds of the City of Peace. The independence, the mode of life, and the pride of the yeomen made them excellent citizens, however, when war broke out with the Indians or with any other foe; and the military spirit of the aristocracy was well sustained by that of the farmers.

The dignity of the town had been early secured by the wisdom of the Company at home, which had committed to the people the government of the district in which they were placed; and every citizen felt himself, in his degree, concerned in the rule and good order of the society in which he lived; but the holders of land recognized no real equality between themselves and men of other callings, while the artisans and laborers were ambitious to obtain a place in the higher class.[15] Artisans of every calling needed in a new society had been sent out from England by the Company; and when all the most energetic had acquired as much land as could be had in recompense for special services to the community—as so many acres for plowing up a meadow, so many for discovering minerals, so many for foiling an Indian raid,—and when the original grants had been broken up, and finally parceled out among sons and daughters, leaving no scope for new purchasers, the most ambitious of the adventurers applied for tracts in Maine, where they might play their part of First Families in a new settlement. The weaker, the more envious, the more ill-conditioned thus remained behind, to cavil at their prosperous neighbors, and spite them if they could. Here was an evident preparation for social disturbance, when opportunity for gratifying bad passions should arise.

There had been a preparation for this stage in the temper with which the adventurers had arrived in the country, and the influences which at once operated upon them there. The politics and the religion in which they had grown up were gloomy and severe. Those who were not soured were sad; and, it should be remembered, they fully believed that Satan and his powers were abroad, and must be contended with daily and hourly, and in every transaction of life. In their new home they found little cheer from the sun and the common daylight; for the forest shrouded the entire land beyond the barren seashore. The special enemy, the Red Indian, always watching them and seeking his advantage of them, was not, in their view, a simple savage. Their clergy assured them that the Red Indians were worshipers and agents of Satan; and it is difficult to estimate the effect of this belief on the minds and tempers of those who were thinking of the Indians at every turn of daily life. The passion which is in the far West still spoken of as special, under the name of “Indian-hating,” is a mingled ferocity and fanaticism quite inconceivable by quiet Christians, or perhaps by any but border adventurers; and this passion, kindled by the first demonstration of hostility on the part of the Massachusetts Red Man, grew and spread incessantly under the painful early experiences of colonial life. Every man had in turn to be scout, by day and night, in the swamp and in the forest; and every woman had to be on the watch in her husband’s absence to save her babes from murderers and kidnappers.[16] Whatever else they might want to be doing, even to supply their commonest needs, the citizens had first to station themselves within hail of each other all day, and at night to drive in their cattle among the dwellings, and keep watch by turns. Even on Sundays patrols were appointed to look to the public safety while the community were at church. The mothers carried their babes to the meeting-house, rather than venture to stay at home in the absence of husband and neighbors. One function of the Sabbath patrol indicates to us other sources of trouble. While looking for Indians, the patrol was to observe who was absent from worship, to mark what the absentees were doing, and to give information to the authorities. These patrols were chosen from the leading men of the community—the most active, vigilant, and sensible—and it is conceivable that much ill-will might have been accumulated in the hearts of not only the ne’er-do-weels, but timid and jealous and angry persons who were uneasy under this Sabbath inspection. Such ill-will had its day of triumph when the Salem Tragedy arrived at its catastrophe.

The ordinary experience of life was singularly accelerated in that new state of society, though in the one particular of the age attained by the primitive adventurers, the community may be regarded as favored. Death made a great sweep of the patriarchs at last—shortly before the Tragedy—but an unusual proportion of elders presided over social affairs for seventy years after the date of the second charter. The chief seats in the meeting-house were filled by gray-haired men and women, rich or poor as might happen; and they were allowed to retain their places, whoever else might be shifted in the yearly “seating.” The title “Landlord” distinguished the most dignified, and the eldest of each family of the “Old Planters;” a “Goodman” and “Goodwife” (abbreviated to “Goody”) were titles of honor, as signifying heads of households. The old age of these venerable persons was carefully cherished; and when, as could not but happen, many of them departed near together, the mourning of the community was deep and bitter. Society seemed to be deprived of its parents, and in fear and grief it anticipated the impending calamity. Except in regard to these patriarchs, and their long old age, the pace of events was very rapid. Early marriages might be looked for in a society so youthful; but the[17] rapid succession of second and subsequent marriages is a striking feature in the register. The most devoted affection seems to have had no effect in deferring a second marriage so long as a year. No time was lost in settling in life at first; families were large; and half-brothers and sisters abounded; and as they grew up they married on the portions which were given them, as a matter of course,—each having house, land, and plenishing, until at last the parents gave away all but a sufficiency for their own need or convenience, and went into the town or remained in the central mansion, turning over the land and its cares to the younger generation. When there was a failure of offspring, the practice of adoption seems to have been resorted to almost as a natural process, which, in such a state of society, it probably was.

In the early days of the arts of life it is usual for the separate transactions of each day to be slow and cumbrous; but the experience of life may be rapid nevertheless. While traveling was a rough jog-trot, and forest-land took years to clear, and the harvest weeks to gather, property grew fast, marriages were precipitate and repeated, one generation trod on the heels of another, and the old folks complained that The Enemy made rapid conquest of the new territory which they had hoped he could not enter. When any work—of house-building, or harvesting, or nutting, or furnishing, or raising the wood-pile—had to be done, it was secured by assembling all the hands in the neighborhood, and turning the toil into a festive pleasure. We have all read of such “bees” in the rural districts of America down to the present day; and we can easily understand how the “goodmen” and “goodies” watched for the good and the evil which came out of such celebrations—the courtship and marriage, and the neighborly interest and good offices on the one hand, and the evil passions from disappointed hopes, envy, jealousy, tittle-tattle, rash judgment, and slander on the other. Much that was said, done, and inferred in such meetings as these found its way long afterward into the Tragedy at Salem. Mr. Upham depicts the inner side of the young social life of which the inquisitorial meeting-house and the courts were the black shadow:

“The people of the early colonial settlements had a private and interior life, as much as we have now, and the people of all ages and countries have had. It is common to regard them in no other light than as[18] a severe, somber, and pleasure-abhorring generation. It was not so with them altogether. They had the same nature that we have. It was not all gloom and severity. They had their recreations, amusements, gayeties, and frolics. Youth was as buoyant with hope and gladness, love as warm and tender, mirth as natural to innocence, wit as sprightly, then as now. There was as much poetry and romance; the merry laugh enlivened the newly opened fields, and rang through the bordering woods as loud, jocund, and unrestrained as in these older and more crowded settlements. It is true that their theology was austere, and their policy, in Church and State, stern; but, in their modes of life, there were some features which gave peculiar opportunity to exercise and gratify a love of social excitement of a pleasurable kind.” (Vol. i. p. 200.)

Except such conflicts as arose about the boundaries of estates when the General Court was remiss in making and enforcing its decisions, the first and greatest strifes related to Church matters and theological doctrines. The farmers had more lively minds, better informed as to law, and more exercised in reasoning and judging than their class are usually supposed to have; for there never was a time when lawsuits were not going forward about the area and the rights of some landed property or other; and intelligent men were called on to follow the course of litigation, if not to serve the community in office. Thus they were prepared for the strife when the operation of the two Churches pressed for settlement.

The farmers in the rural district thenceforward to be called “Salem Village,” desired to have a meeting-house and a minister of their own; but the town authorities insisted on taxing them for the religious establishment in Salem, from which they derived no benefit. In 1670, twenty of them petitioned to be set off as a parish, and allowed to provide a minister for themselves. In two years more the petition was granted, as a compromise for larger privileges; but there were restrictions which spoiled the grace of such concession as there was. One of these restrictions was that no minister was to be permanently settled without the permission of the old Church to proceed to his ordination. Endless trouble arose out of this provision. The men who had contributed the land, labor, and material for the meeting-house, and the[19] maintenance for the pastor, naturally desired to be free in their choice of their minister, while the Church authorities in Salem considered themselves responsible for the maintenance of true doctrine, and for leaving no opening for Satan to enter the fold in the form of heresy, or any kind or degree of dissent. Their fathers, the first settlers, had made the colony too hot for one of their most virtuous and distinguished citizens, because he had views of his own on Infant Baptism; they had brought him to judgment, magistrate and church member as he was, for not having presented his infant child at the font; he had sold his estates and gone away. If such a citizen as Townsend Bishop was thus lost to their society, how could the guardians of religion surrender their control over any church or pastor within their reach? They had spiritual charge of a community which had made its abode on the American shore for the single purpose of living its own religious life in its own way; and no dissent or modification from within could be permitted, any more than intrusion or molestation from without. Between the ecclesiastical view on the one hand, and the civil view on the other, there was small chance of harmony between town and village, or between pastor, flock, and the overseers of both. The great point on which they were all agreed was that they were all in special danger from the extreme malice of Satan, who, foiled in Puritan England, was bent on revenge in America, and was visibly and audibly present in the settlement, seeking whom he might devour.

Quarreling began with the appearance of the first minister, a young Mr. Bayley, who was appointed from year to year, but never ordained the pastor till 1679, when the authorities of Salem tried to force him upon the people of Salem Village in the face of strong opposition. The farmers disregarded the orders issued from the town, and managed their religious affairs by general meetings of their own congregation; and at length Mr. Bayley retired, leaving the society in a much worse temper than he had found on his arrival. A handsome gift of land was settled upon him, in acknowledgment of his services; he quitted the ministry, and practiced medicine in Roxbury till his death, nearly thirty years afterward.

His partisans were enemies of his successor, of course. Mr. Burroughs was a man of even distinguished excellence in the pastoral relation, in days when risks from Indians made that duty as perilous as the[20] career of the soldier in war time; but his flock were divided, church business was neglected, he was allowed to fall into want. He withdrew, was recalled to settle accounts, was arrested for debt in full meeting—the debt being for the funeral expenses of his wife—was absolved from all blame under the cruel neglect he had experienced—and left the Village. Before he could hear in his remote home in Maine what was doing at Salem in the first days of the Witch Tragedy, he was summoned to his old neighborhood, was charged with sorcery on the most childish and absurd testimony conceivable, and executed in August, 1692. One of the witnesses—a young girl morbid in body and mind—poured out her remorse to him the day before his death. He, believing her a victim of Satan, forgave her, prayed with her, and died honored and beloved by all who were not under the curse of the bigotry of the time.

The third minister was one Deodat Lawson, who is notable—besides his learning—for his Sermon on the Devil, and for some mournful mystery about his end. Of his last days there is nothing known but that there was something woeful in them; but his sermon, preached at the commencement of the outbreak in Salem, remains to us. It was published in America, and then widely circulated in England. It met the popular craving for light about Satan and his doings; and thus, between its appropriateness to the time and occasion, and the learning and ability which it manifested, it produced an extraordinary effect in its day. In ours it is an instructive evidence of the extent to which “knowledge falsely so called” may operate on the mind of society, in the absence of science, and before the time has arrived for a clear understanding of the nature of knowledge and the conditions of its attainment. Mr. Lawson bore a part in the Salem Tragedy, and then went to England, where we hear of him from Calamy as “the unhappy Mr. Deodat Lawson,” and he disappears.

The fourth and last of the ministers of Salem Village, before the Tragedy, was the Mr. Parris who played the most conspicuous part in it. He must have been a man of singular shamelessness, as well as remarkable selfishness, craft, ruthlessness, and withal imprudence. He began his operations with sharp bargaining about his stipend, and[21] sharp practice in appropriating the house and land assigned for the use of successive pastors. He wrought diligently under the stimulus of his ambition till he got his meeting-house sanctioned as a true church, and himself ordained as the first pastor of Salem Village. This was in 1689. He immediately launched out into such an exercise of priestly power as could hardly be exceeded under any form of church government; he set his people by the ears on every possible occasion and on every possible pretense; he made his church a scandal in the land for its brawls and controversies; and on him rests the responsibility of the disease and madness which presently turned his parish into a hell, and made it famous for the murder of the wisest, gentlest, and purest Christians it contained. [This man Parris must have had an inferior intellect, small Conscientiousness, Benevolence, and Veneration; large Firmness, Self-Esteem, Combativeness, Destructiveness, and Acquisitiveness.]

Before we look at his next proceeding, however, we must bring into view one or two facts essential to the understanding of the case. We have already observed on the universality of the belief in the ever-present agency of Satan in that region and that special season. In the woods the Red Men were his agents—living in and for his service and his worship. In the open country, Satan himself was seen, as a black horse, a black dog, as a tall, dark stranger, as a raven, a wolf, a cat, etc. Strange incidents happened there as everywhere—odd bodily affections and mental movements; and when devilish influences are watched for, they are sure to be seen. Everybody was prepared for manifestations of witchcraft from the first landing in the Bay; and there had been more and more cases, not only rumored, but brought under investigation, for some years before the final outbreak.

This suggests the next consideration: that the generation concerned had no “alternative” explanation within their reach, when perplexed by unusual appearances or actions of body or mind. They believed themselves perfectly certain about the Devil and his doings; and his agency was the only solution of their difficulties, while it was a very complete one. They thought they knew that his method of working was by human agents, whom he had won over and bound to his service. They had all been brought up to believe this; and they never thought of doubting it.

The very conception of science had then scarcely begun to be formed in the minds of the wisest men of the time; and if it had been, who was there to suggest that the handful of pulp contained in the human skull, and the soft string of marrow in the spine, and cobweb lines of nerves, apparently of no more account than the hairs of the head, could transmit thoughts, emotions, passions—all the scenery of the spiritual world! For two hundred years more there was no effectual recognition of anything of the sort. At the end of those two centuries anatomists themselves were slicing the brain like a turnip, to see what was inside it,—not dreaming of the leading facts of its structure, nor of the inconceivable delicacy of its organization. After half a century of knowledge of the main truth in regard to the brain, and nearly that period of study of its organization, by every established medical authority in the civilized world, we are still perplexed and baffled at every turn of the inquiry into the relations of body and mind. How, then, can we make sufficient allowance for the effects of ignorance in a community where theology was the main interest in life, where science was yet unborn, and where all the influences of the period concurred to produce and aggravate superstitions and bigotries which now seem scarcely credible?

[The reviewer appears to be a half believer in Phrenology, and yet unwilling to acknowledge his indebtedness to its teachers for the light he has received in the organization and phenomena of the brain.]

There had been misery enough caused by persecutions for witchcraft within living memory to have warned Mr. Parris, one would think, how he carried down his people into those troubled waters again; but at that time such trials were regarded by society as trials for murder are by us, and not as anything surprising except from the degree of wickedness. William Penn presided at the trial of two Swedish women in Philadelphia for this gravest of crimes; and it was only by the accident of a legal informality that they escaped, the case being regarded with about the same feeling as we experienced a year or two ago when the murderess of infants, Charlotte Winsor, was saved from hanging by a doubt of the law. If the crime spread—as it usually did—the municipal governments issued an order for a day of fasting and[23] humiliation, “in consideration of the extent to which Satan prevails amongst us in respect of witchcraft.” Among the prosecutions which followed on such observances there was one here and there which turned out, too late, to have been a mistake. This kind of discovery might be made an occasion for more fasting and humiliation; but it seems to have had no effect in inducing caution or suggesting self-distrust. Mr. Parris and his partisans must have been aware that on occasion of the last great spread of witchcraft, the magistrates and the General Court had set aside the verdict of the jury in one case of wrongful accusation, and that there were other instances in which the general heart and conscience were cruelly wounded and oppressed, under the conviction that the wisest and saintliest woman in the community had been made away with by malice, at least as much as mistaken zeal.

The wife of one of the most honored and prominent citizens of Boston, and the sister of the Deputy Governor of Massachusetts, Mrs. Hibbins, might have been supposed safe from the gallows, while she walked in uprightness, and all holiness and gentleness of living. But her husband died; and the pack of fanatics sprang upon her, and tore her to pieces—name and fame, fortune, life, and everything. She was hanged in 1656, and the farmers of Salem Village and their pastor were old enough to know, in Mr. Parris’ time, how the “famous Mr. Norton,” an eminent pastor, “once said at his own table”—before clergymen and elders—“that one of their magistrates’ wives was hanged for a witch, only for having more wit than her neighbors;” and to be aware that in Boston “a deep feeling of resentment” against her persecutors rankled in the minds of some of her citizens; and that they afterward “observed solemn marks of Providence set upon those who were very forward to condemn her.” The story of Mrs. Hibbins, as told in the book before us, with the brief and simple comment of her own pleading in court, and the codicil to her will, is so piteous and so fearful, that it is difficult to imagine how any clergyman could countenance a similar procedure before the memory of the execution had died out, and could be supported in his course by officers of his church, and at length by the leading clergy of the district, the magistrates, the physicians, “and devout women not a few.”

[Here are evidences of large Cautiousness, fear, and timidity, with the vivid imagination of untrained childhood.]

In the interval between the execution of Mrs. Hibbins and the outbreak at Salem an occasional breeze arose against some unpopular member of society. If a man’s ox was ill, if the beer ran out of the cask, if the butter would not come in the churn, if a horse shied or was restless when this or that man or woman was in sight; and if a woman knew when her neighbors were talking about her (which was Mrs. Hibbins’ most indisputable proof of connection with the devil), rumors got about of Satanic intercourse; men and women made deposition that six or seven years before, they had seen the suspected person yawn in church, and had observed a “devil’s teat” distinctly visible under his tongue; and children told of bears coming to them in the night, and of a buzzing devil in the humble-bee, and of a cat on the bed thrice as big as an ordinary cat. But the authorities, on occasion, exercised some caution. They fined one accused person for telling a lie, instead of treating his bragging as inspiration of the devil. They induced timely confession, or discovered flaws in the evidence, as often as they could; so that there was less disturbance in the immediate neighborhood than in some other parts of the province. Where the Rev. Mr. Parris went, however, there was no more peace and quiet, no more privacy in the home, no more harmony in the church, no more goodwill or good manners in society.

As soon as he was ordained he put perplexing questions about baptism before the farmers, who rather looked to him for guidance in such matters than expected to be exercised in theological mysteries which they had never studied. He exposed to the congregation the spiritual conflicts of individual members who were too humble for their own comfort. He preached and prayed incessantly about his own wrongs and the slights he suffered, in regard to his salary and supplies; and entered satirical notes in the margin of the church records; so that he was as abundantly discussed from house to house, and from end to end of his parish, as he himself could have desired. In the very crisis of the discontent, and when his little world was expecting to see him dismissed, he saved himself, as we ourselves have of late seen other persons relieve themselves under stress of mind and circumstances, by a rush into the world of spirits.

Four years previously, a poor immigrant, a Catholic Irishwoman,[25] had been hanged in Boston for bewitching four children, named Goodwin—one of whom, a girl of thirteen, had sorely tried a reverend man, less irascible than Mr. Parris, but nearly as excitable. The tricks that the little girl played the Reverend Cotton Mather, when he endeavored to exorcise the evil spirits, are precisely such as are familiar to us, in cases which are common in the practice of every physician. If we can not pretend to explain them—in the true sense of explaining—that is, referring them to an ascertained law of nature, we know what to look for under certain conditions, and are aware that it is the brain and nervous system that is implicated in these phenomena, and not the Prince of Darkness and his train. Cotton Mather had no alternative at his disposal. Satan or nothing was his only choice. He published the story, with all its absurd details; and it was read in almost every house in the Province. At Salem it wrought with fatal effect, because there was a pastor close by well qualified to make the utmost mischief out of it.

[In cases of hysteria, the phenomena are sometimes so remarkable, that one is disposed to attribute their cause to influences beyond nature.]

Mr. Parris had lived in the West Indies for some years, and had brought several slaves with him to Salem. One of these, an Indian named John, and Tituba his wife, seem to have been full of the gross superstitions of their people, and of the frame and temperament best adapted for the practices of demonology. In such a state of affairs the pastor actually formed, or allowed to be formed, a society of young girls between the ages of eight and eighteen to meet in his parsonage, strongly resembling those “circles” in the America of our time which have filled the lunatic asylums with thousands of victims of “spiritualist” visitations. It seems that these young persons were laboring under strong nervous excitement, which was encouraged rather than repressed by the means employed by their spiritual director. Instead of treating them as the subjects of morbid delusion, Mr. Parris regarded them as the victims of external diabolical influence; and this influence was, strangely enough, supposed to be exercised, on the evidence of the children themselves, by some of the most pious and respectable members of the community.

We need not describe the course of events. In the dull life of the[26] country, the excitement of the proceedings in the “circle” was welcome, no doubt; and it was always on the increase. Whatever trickery there might be—and no doubt there was plenty; whatever excitement to hysteria, whatever actual sharpening of common faculties, it is clear that there was more; and those who have given due and dispassionate attention to the processes of mesmerism and their effects can have no difficulty in understanding the reports handed down of what these young creatures did, and said, and saw, under peculiar conditions of the nervous system. When the physicians of the district could see no explanation of the ailments of “the afflicted children” but “the evil hand,” no doubt could remain to those who consulted them of these agonies being the work of Satan. The matter was settled at once. But Satan can work only through human agents; and who were his instruments for the affliction of these children? Here was the opening through which calamity rushed in; and for half a year this favored corner of the godly land of New England was turned into a hell. The more the children were stared at and pitied, the bolder they grew in their vagaries, till at last they broke through the restraints of public worship, and talked nonsense to the minister in the pulpit, and profaned the prayers. Mr. Parris assembled all the divines he could collect at his parsonage, and made his troop go through their performances—the result of which was a general groan over the manifest presence of the Evil One, and a passionate intercession for “the afflicted children.”

[These afflicted children of Salem, in 1690, were kindred to the numerous “mediums” of 1869. In the former, ignorance ascribed their actions and revelations to the devil, who bewitched certain persons. Now, we simply have the more innocent “communications” from where and from whom you like.]

The first step toward relief was to learn who it was that had stricken them; and the readiest means that occurred was to ask this question of the children themselves. At first, they named no names, or what they said was not disclosed; but there was soon an end of all such delicacy. The first symptoms had occurred in November, 1691; and the first public examination of witches took place on the 1st of March following. We shall cite as few of the cases as will suffice for our[27] purpose; for they are exceedingly painful; and there is something more instructive for us in the spectacle of the consequences, and in the suggestions of the story, than in the scenery of persecution and murder.

In the first group of accused persons was one Sarah Good, a weak, ignorant, poor, despised woman, whose equally weak and ignorant husband had forsaken her, and left her to the mercy of evil tongues. He had called her an enemy to all good, and had said that if she was not a witch, he feared she would be one shortly. Her assertions under examination were that she knew nothing about the matter; that she had hurt nobody, nor employed anybody to hurt another; that she served God; and that the God she served was He who made heaven and earth. It appears, however, that she believed in the reality of the “affliction;” for she ended by accusing a fellow-prisoner of having hurt the children. The report of the examination, noted at the time by two of the heads of the congregation, is inane and silly beyond belief; yet the celebration was unutterably solemn to the assembled crowd of fellow-worshipers; and it sealed the doom of the community, in regard to peace and good repute.

Mrs. Good was carried to jail. Not long after her little daughter Dorcas, aged four years, was apprehended at the suit of the brothers Putnam, chief citizens of Salem. There was plenty of testimony produced of bitings and chokings and pinchings inflicted by this infant; and she was committed to prison, and probably, as Mr. Upham says, fettered with the same chains which bound her mother. Nothing short of chains could keep witches from flying away; and they were chained at the cost of the state, when they could not pay for their own irons. As these poor creatures were friendless and poverty-stricken, it is some comfort to find the jailer charging for “two blankets for Sarah Good’s child,” costing ten shillings.

What became of little Dorcas, with her healthy looks and natural childlike spirits, noticed by her accusers, we do not learn. Her mother lay in chains till the 29th of June, when she was brought out to receive sentence. She was hanged on the 19th of July, after having relieved her heart by vehement speech of some of the passion which weighed upon it. She does not seem to have been capable of much thought.[28] One of the accusers was convicted of a flagrant lie, in the act of giving testimony: but the narrator, Hutchinson, while giving the fact, treats it as of no consequence, because Sir Matthew Hale and the jury of his court were satisfied with the condemnation of a witch under precisely the same circumstances. The parting glimpse we have of this first victim is dismally true on the face of it. It is most characteristic.

“Sarah Good appears to have been an unfortunate woman, having been subject to poverty, and consequent sadness and melancholy. But she was not wholly broken in spirit. Mr. Noyes, at the time of her execution, urged her very strenuously to confess. Among other things, he told her ‘she was a witch, and that she knew she was a witch.’ She was conscious of her innocence, and felt that she was oppressed, outraged, trampled upon, and about to be murdered, under the forms of law; and her indignation was roused against her persecutors. She could not bear in silence the cruel aspersion; and although she was about to be launched into eternity, the torrent of her feelings could not be restrained, but burst upon the head of him who uttered the false accusation. ‘You are a liar,’ said she. ‘I am no more a witch than you are a wizard; and if you take away my life, God will give you blood to drink.’ Hutchinson says that, in his day, there was a tradition among the people of Salem, and it has descended to the present time, that the manner of Mr. Noyes’ death strangely verified the prediction thus wrung from the incensed spirit of the dying woman. He was exceedingly corpulent, of a plethoric habit, and died of an internal hemorrhage, bleeding profusely at the mouth.” (Vol. ii. p. 269.)

When she had been in her grave nearly twenty years, her representatives—little Dorcas perhaps for one—were presented with thirty pounds sterling, as a grant from the Crown, as compensation for the mistake of hanging her without reason and against evidence.

In the early part of the century, a devout family named Towne were living at Great Yarmouth, in the English county of Norfolk. About the time of the King’s execution they emigrated to Massachusetts. William Towne and his wife carried with them two daughters; and another daughter and a son were born to them afterward in Salem. The three daughters were baptized at long intervals, and the eldest, Rebecca, must have been at least twenty years older than Sarah, and a[29] dozen or more years older than Mary. A sketch of the fate of these three sisters contains within it the history of a century.

On the map which Mr. Upham presents us with, one of the most conspicuous estates is an inclosure of 300 acres, which had a significant story of its own—too long for us to enter upon. We need only say that there had been many strifes about this property—fights about boundaries, and stripping of timber, and a series of lawsuits. Yet, from 1678 onward, the actual residents in the mansion had lived in peace, taking no notice of wrangles which did not, under the conditions of purchase, affect them, but only the former proprietor. The frontispiece of Mr. Upham’s book shows us what the mansion of an opulent landowner was like in the early days of the colony. It is the portrait of the house in which the eldest daughter of William Towne was living at the date of the Salem Tragedy.

Rebecca, then the aged wife of Francis Nurse, was a great-grandmother, and between seventy and eighty years of age. No old age could have had a more lovely aspect than hers. Her husband was, as he had always been, devoted to her, and the estate was a colony of sons and daughters, and their wives and husbands; for ‘Landlord Nurse’ had divided his land between his four sons and three sons-in-law, and had built homesteads for them all as they married and settled. Mrs. Nurse was in full activity of faculty, except being somewhat deaf from age; and her health was good, except for certain infirmities of long standing, which it required the zeal and the malice of such a divine as Mr. Parris to convert into “devil’s marks.” As for her repute in the society of which she was the honored head, we learn what it was by the testimony supplied by forty persons—neighbors and householders—who were inquired of in regard to their opinion of her in the day of her sore trial. Some of them had known her above forty years; they had seen her bring up a large family in uprightness; they had remarked the beauty of her Christian profession and conduct; and had never heard or observed any evil of her. This was Rebecca, the eldest.

The next, Mary, was now fifty-eight years old, the wife of “Goodman Easty,” the owner of a large farm. She had seven children, and was living in ease and welfare of every sort when overtaken by the same calamity as her sister Nurse. Sarah, the youngest, had married twice. Her present husband was Peter Cloyse, whose name occurs in[30] the parish records, and in various depositions which show that he was a prominent citizen. When Mr. Parris was publicly complaining of neglect in respect of firewood for the parsonage, and of lukewarmness on the part of the hearers of his services, “Landlord Nurse” was a member of the committee who had to deal with him; and his relatives were probably among the majority who were longing for Mr. Parris’ apparently inevitable departure. In these circumstances, it was not altogether surprising that “the afflicted children” trained in the parsonage parlor, ventured, after their first successes, to name the honored “Goody Nurse” as one of the allies lately acquired by Satan. They saw her here, there, everywhere, when she was sitting quietly at home; they saw her biting the black servants, choking, pinching, pricking women and children; and if she was examined, devil’s marks would doubtless be found upon her. She was examined by a jury of her own sex. Neither the testimony of her sisters and daughters as to her infirmities, nor the disgust of decent neighbors, nor the commonest suggestions of reason and feeling, availed to save her from the injury of being reported to have what the witnesses were looking for.

We have a glimpse of her in her home when the first conception of her impending fate opened upon her. Four esteemed persons, one of whom was her brother-in-law, Mr. Cloyse, made the following deposition, in the prospect of the victim being dragged before the public:

“We whose names are underwritten being desired to go to Goodman Nurse, his house, to speak with his wife, and to tell her that several of the afflicted persons mentioned her; and accordingly we went, and we found her in a weak and low condition in body as she told us, and had been sick almost a week. And we asked how it was otherwise with her; and she said she blessed God for it, she had more of his presence in this sickness than sometimes she have had, but not so much as she desired; but she would, with the Apostle, press forward to the mark; and many other places of Scripture to the like purpose. And then of her own accord she began to speak of the affliction that was among them, and in particular of Mr. Parris his family, and how she was grieved for them, though she had not been to see them, by reason of fits that she formerly used to have; for people said it was awful to behold: but she pitied them with all her heart, and went to God for them. But she said she heard that there was persons spoke of that were as innocent as she was, she believed; and after much to this[31] purpose, we told her we heard that she was spoken of also. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘if it be so, the will of the Lord be done:’ she sat still awhile being as it were amazed; and then she said, ‘Well, as to this thing I am as innocent as the child unborn; but surely,’ she said, ‘what sin hath God found out in me unrepented of, that he should lay such an affliction upon me in my old age?’ and, according to our best observation, we could not discern that she knew what we came for before we told her.

| Israel Porter, | Daniel Andrew, |

| Elizabeth Porter, | Peter Cloyse.” |

On the 22d of March she was brought into the thronged meeting-house to be accused before the magistrates, and to answer as she best could. We must pass over those painful pages, where nonsense, spasms of hysteria, new and strange to their worships, cunning, cruelty, blasphemy, indecency, turned the house of prayer into a hell for the time. The aged woman could explain nothing. She simply asserted her innocence, and supposed that some evil spirit was at work. One thing more she could do—she could endure with calmness malice and injustice which are too much for our composure at a distance of nearly two centuries. She felt the animus of her enemies, and she pointed out how they perverted whatever she said; but no impatient word escaped her. She was evidently as perplexed as anybody present. When weary and disheartened, and worn out with the noise and the numbers and the hysterics of the “afflicted,” her head drooped on one shoulder. Immediately all the “afflicted” had twisted necks, and rude hands seized her head to set it upright, “lest other necks should be broken by her ill offices.” Everything went against her, and the result was what had been hoped by the agitators. The venerable matron was carried to jail and put in irons.

Now Mr. Parris’ time had arrived, and he broadly accused her of murder, employing for the purpose a fitting instrument—Mrs. Ann Putnam, the mother of one of the afflicted children, and herself of highly nervous temperament, undisciplined mind, and absolute devotedness to her pastor. Her deposition, preceded by a short one of Mr. Parris, will show the quality of the evidence on which judicial murder was inflicted:

“Mr. Parris gave in a deposition against her; from which it appears, that, a certain person being sick, Mercy Lewis was sent for. She was struck dumb on entering the chamber. She was asked to hold up her hand if she saw any of the witches afflicting the patient. Presently she held up her hand, then fell into a trance; and after a while, coming to herself, said that she saw the spectre of Goody Nurse and Goody Carrier having hold of the head of the sick man. Mr. Parris swore to this statement with the utmost confidence in Mercy’s declarations.” (Vol. ii. p. 275.)

“The deposition of Ann Putnam, the wife of Thomas Putnam, aged about thirty years, who testifieth and saith, that on March 18, 1692, I being wearied out in helping to tend my poor afflicted child and maid, about the middle of the afternoon I lay me down on the bed to take a little rest; and immediately I was almost pressed and choked to death, that had it not been for the mercy of a gracious God and the help of those that were with me, I could not have lived many moments; and presently I saw the apparition of Martha Corey, who did torture me so as I can not express, ready to tear me all to pieces, and then departed from me a little while; but, before I could recover strength or well take breath, the apparition of Martha Corey fell upon me again with dreadful tortures, and hellish temptation to go along with her. And she also brought to me a little red book in her hand, and a black pen, urging me vehemently to write in her book; and several times that day she did most grievously torture me, almost ready to kill me. And on the 19th of March, Martha Corey again appeared to me; and also Rebecca Nurse, the wife of Francis Nurse, Sr.; and they both did torture me a great many times this day, with such tortures as no tongue can express, because I would not yield to their hellish temptations, that, had I not been upheld by an Almighty arm, I could not have lived while night. The 20th of March, being Sabbath-day, I had a great deal of respite between my fits. 21st of March being the day of the examination of Martha Corey, I had not many fits, though I was very weak; my strength being, as I thought, almost gone; but, on 22d of March, 1692, the apparition of Rebecca Nurse did again set upon me in a most dreadful manner, very early in the morning, as soon as it was well light. And now she appeared to me only in her shift, and brought a little red book in her hand, urging me vehemently to write in her book; and, because I would not yield[33] to her hellish temptations, she threatened to tear my soul out of my body, blasphemously denying the blessed God, and the power of the Lord Jesus Christ to save my soul; and denying several places of Scripture, which I told her of, to repel her hellish temptations. And for near two hours together, at this time, the apparition of Rebecca Nurse did tempt and torture me, and also the greater part of this day, with but very little respite. 23d of March, am again afflicted by the apparitions of Rebecca Nurse and Martha Corey, but chiefly by Rebecca Nurse. 24th of March, being the day of the examination of Rebecca Nurse, I was several times afflicted in the morning by the apparition of Rebecca Nurse, but most dreadfully tortured by her in the time of her examination, insomuch that the honored magistrates gave my husband leave to carry me out of the meeting-house; and, as soon as I was carried out of the meeting-house doors, it pleased Almighty God, for his free grace and mercy’s sake, to deliver me out of the paws of those roaring lions, and jaws of those tearing bears, that, ever since that time, they have not had power so to afflict me until this May 31, 1692. At the same moment that I was hearing my evidence read by the honored magistrates, to take my oath, I was again re-assaulted and tortured by my before-mentioned tormentor, Rebecca Nurse.” “The testimony of Ann Putnam, Jr., witnesseth and saith, that, being in the room where her mother was afflicted, she saw Martha Corey, Sarah Cloyse, and Rebecca Nurse, or their apparitions, upon her mother.”

“Mrs. Ann Putnam made another deposition under oath at the same trial, which shows that she was determined to overwhelm the prisoner by the multitude of her charges. She says that Rebecca Nurse’s apparition declared to her that ‘she had killed Benjamin Houlton, John Fuller, and Rebecca Shepherd;’ and that she and her sister Cloyse, and Edward Bishop’s wife, had killed young John Putnam’s child; and she further deposed as followeth: ‘Immediately there did appear to me six children in winding-sheets, which called me aunt, which did most grievously affright me; and they told me that they were my sister Baker’s children of Boston; and that Goody Nurse, and Mistress Corey of Charlestown, and an old deaf woman at Boston, had murdered them, and charged me to go and tell these things to the magistrates, or else they would tear me to pieces, for their blood did cry for vengeance. Also there appeared to me my own sister Bayley[34] and three of her children in winding-sheets, and told me that Goody Nurse had murdered them.’” (Vol. ii. p. 278.)

All the efforts made to procure testimony against the venerable gentlewoman’s character issued in a charge that she had so “railed at” a neighbor for allowing his pigs to get into her field that, some short time after, early in the morning, he had a sort of fit in his own entry, and languished in health from that day, and died in a fit at the end of the summer. “He departed this life by a cruel death,” murdered by Goody Nurse. The jury did not consider this ground enough for hanging the old lady, who had been the ornament of their church and the glory of their village and its society. Their verdict was “Not Guilty.” Not for a moment, however, could the prisoner and her family hope that their trial was over. The outside crowd clamored; the “afflicted” howled and struggled; one judge declared himself dissatisfied; another promised to have her indicted anew; and the Chief Justice pointed out a phrase of the prisoner’s which might be made to signify that she was one of the accused gang in guilt, as well as in jeopardy. It might really seem as if the authorities were all driveling together, when we see the ingenuity and persistence with which they discussed those three words, “of our company.” Her remonstrance ought to have moved them:

“I intended no otherwise than as they were prisoners with us, and therefore did then, and yet do, judge them not legal evidence against their fellow-prisoners. And I being something hard of hearing and full of grief, none informing me how the Court took up my words, therefore had no opportunity to declare what I intended when I said they were of our company.” (Vol. ii. p. 285.)

The foreman of the jury would have taken the favorable view of this matter, and have allowed full consideration, while other jurymen were eager to recall the mistake of their verdict; but the prisoner’s silence, from failing to hear when she was expected to explain, turned the foreman against her, and caused him to declare, “whereupon these words were to me a principal evidence against her.” Still, it seemed too monstrous to hang her. After her condemnation, the Governor reprieved her; probably on the ground of the illegality of setting aside the first verdict of the jury, in the absence of any new evidence. But the outcry against mercy was so fierce that the Governor withdrew his reprieve.

On the next Sunday there was a scene in the church, the record of which was afterward annotated by the church members in a spirit of grief and humiliation. After sacrament the elders propounded to the church, and the congregation unanimously agreed, that Sister Nurse, being convicted as a witch by the court, should be excommunicated in the afternoon of the same day. The place was thronged; the reverend elders were in the pulpit; the deacons presided below; the sheriff and his officers brought in the witch, and led her up the broad aisle, her chains clanking as she moved. As she stood in the middle of the aisle, the Reverend Mr. Noyes pronounced her sentence of expulsion from the Church on earth, and from all hope of salvation hereafter. As she had given her soul to Satan, she was delivered over to him for ever. She was aware that every eye regarded her with horror and hate, unapproached under any other circumstances; but it appears that she was able to sustain it. She was still calm and at peace on that day, and during the fortnight of final waiting. When the time came, she traversed the streets of Salem between houses in which she had been an honored guest, and surrounded by well-known faces; and then there was the hard task, for her aged limbs, of climbing the rocky and steep path on Witches’ Hill to the place where the gibbets stood in a row, and the hangman was waiting for her, and for Sarah Good, and several more of whom Salem chose to be rid that day. It was the 19th of July, 1692. The bodies were put out of the way on the hill, like so many dead dogs; but this one did not remain there long. By pious hands it was—nobody knew when—brought home to the domestic cemetery, where the next generation pointed out the grave, next to her husband’s, and surrounded by those of her children. As for her repute, Hutchinson, the historian, tells us that even excommunication could not permanently disgrace her. “Her life and conversation had been such, that the remembrance thereof, in a short time after, wiped off all the reproach occasioned by the civil or ecclesiastical sentence against her.” (Vol. ii. p. 292.)

[Great God! and is this the road our ancestors had to travel in their pilgrimage in quest of freedom and Christianity? Are these the fruits of the misunderstood doctrine of total depravity?]

Thus much comfort her husband had till he died in 1695. In a little[36] while none of his eight children remained unmarried, and he wound up his affairs. He gave over the homestead to his son Samuel, and divided all he had among the others, reserving only a mare and her saddle, some favorite articles of furniture, and £14 a year, with a right to call on his children for any further amount that might be needful. He made no will, and his children made no difficulties, but tended his latter days, and laid him in his own ground, when at seventy-seven years old he died.

In 1711, the authorities of the Province, sanctioned by the Council of Queen Anne, proposed such reparation as their heart and conscience suggested. They made a grant to the representatives of Rebecca Nurse of £25! In the following year something better was done, on the petition of the son Samuel who inhabited the homestead. A church meeting was called; the facts of the excommunication of twenty years before were recited, and a reversal was proposed, “the General Court having taken off the attainder, and the testimony on which she was convicted being not now so satisfactory to ourselves and others as it was generally in that hour of darkness and temptation.” The remorseful congregation blotted out the record in the church book, “humbly requesting that the merciful God would pardon whatsoever sin, error, or mistake was in the application of that censure, and of the whole affair, through our merciful High Priest, who knoweth how to have compassion on the ignorant, and those that are out of the way.” (Vol. ii. p. 483.)

Such was the fate of Rebecca, the eldest of the three sisters. Mary, the next—once her playmate on the sands of Yarmouth, in the old country—was her companion to the last, in love and destiny. Mrs. Easty was arrested, with many other accused persons, on the 21st of April, while her sister was in jail in irons. The testimony against her was a mere repetition of the charges of torturing, strangling, pricking, and pinching Mr. Parris’ young friends, and rendering them dumb, or blind, or amazed. Mrs. Easty was evidently so astonished and perplexed by the assertions of the children, that the magistrates inquired of the voluble witnesses whether they might not be mistaken. As they were positive, and Mrs. Easty could say only that she supposed it was “a bad spirit,” but did not know “whether it was witchcraft or not,”[37] there was nothing to be done but to send her to prison and put her in irons. The next we hear of her is, that on the 18th of May she was free. The authorities, it seems, would not detain her on such evidence as was offered. She was at large for two days, and no more. The convulsions and tortures of the children returned instantly, on the news being told of Goody Easty being abroad again; and the ministers, and elders, and deacons, and all the zealous antagonists of Satan went to work so vigorously to get up a fresh case, that they bore down all before them. Mercy Lewis was so near death under the hands of Mrs. Easty’s apparition that she was crying out “Dear Lord! receive my soul!” and thus there was clearly no time to be lost; and this choking and convulsion, says an eminent citizen, acting as a witness, “occurred very often until such time as we understood Mary Easty was laid in irons.”

There she was lying when her sister Nurse was tried, excommunicated, and executed; and to the agony of all this was added the arrest of her sister Sarah, Mrs. Cloyse. But she had such strength as kept her serene up to the moment of her death on the gibbet on the 22d of September following. We would fain give, if we had room, the petition of the two sisters, Mrs. Easty and Mrs. Cloyse, to the court, when their trial was pending; but we can make room only for the last clause of its reasoning and remonstrance.