BY

PERCY K. FITZHUGH

Author of

“TOM SLADE, BOY SCOUT OF THE MOVING PICTURES,”

“TOM SLADE AT TEMPLE CAMP” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

WALTER S. ROGERS

PUBLISHED WITH THE APPROVAL OF

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS :: NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1917, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

“But suppose they shouldn’t come.”

“Son, when I wuz out in Colorady, in a place we called Devil’s Pass, I gut a grizzly backed up agin’ a ledge one day ’n’ heving ony one bullet ’twas a case uv me or him, as yer might say. My pardner, Simon Gurthy, who likewise didn’t hev no bullets, ’count uv bein’ stripped b’ the Injins, he says, ‘S’posin’ ye don’t fetch him.’ ’N’ I says, ‘S’posin’ I do.’”

Jeb Rushmore, with methodical accuracy, spat at a sapling near by.

“And did you?” asked his listener.

Jeb spat again with leisurely deliberation. “’N’ I did,” said he.

“You always hit, don’t you, Jeb?”

“Purty near.”

The boy edged along the log on which they were sitting and looked up admiringly into the wrinkled, weatherbeaten face. A smile which did not altogether penetrate through the drooping gray mustache was visible enough in the twinkling eyes and drew the wrinkles about them like sun rays.

“They’ll come,” said he.

The boy was satisfied for he had absolute confidence that his companion could not make a mistake.

“But suppose you hadn’t hit him—I mean fetched him?”

“Son, wot yer got to do, yer do. When I told General Custer onct that we’d get picked off like cherries offen a tree if we tried rushin’ a pack uv Sioux that was in ambush, he says, ‘Jeb, mebbe it cain’t be done, I ain’t sayin’, but jest the same, we got ter do it.’ Some on us got dropped, but we done it.”

“Did General Custer call you by your first name?”

“Same’s you do.”

This was too much for the little fellow. “Gee, it must have been great to have General Custer call you by your first name.”

“Wal, now, I ben thinkin’ ’twas purty fine this winter hevin’ yew call me by my fust name, ’n’ keep me comp’ny here. We’ve got ter be close pards, me an’ you, hain’t we, son?”

“Gee, I’m almost sorry they’re coming—kind of.”

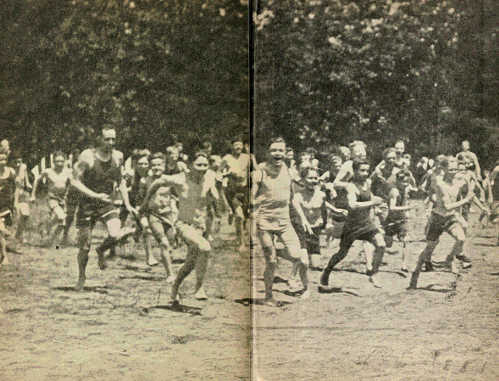

They were certainly coming—“in chunks,” as Roy Blakeley would have said, and before night the camp would be a veritable beehive. All summer troops would be coming and going, but just now the opening rush was at hand, and the exodus from eastern towns and cities, following the closing of schools, would go far to fill the camp even to its generous capacity before this Saturday’s sun had set.

The Bridgeboro Troop, from the home town of the camp’s generous founder, Mr. John Temple, would arrive sometime in the afternoon “with bells on” according to the post card which little Raymond Hollister had brought up from the post office the day before.

They were cruising up the Hudson to Catskill Landing in their cabin launch, the Good Turn, and would hike it up through Leeds to camp. The card was postmarked Poughkeepsie, and read:

Desert Island of Poughkeepsie, Longitude 23, Latitude 40-11.

“Put in here for gasoline and ice-cream soda. Natives friendly. Heavy gales. Raining in sheets and pillow-cases. Mutiny on board. Pee-wee Harris, N. G. Mariner, put in irons for stealing peanuts from galley. Boarded by pirates below Peekskill. Coming north with bells on. Reach camp Saturday late. All’s well with a yo-heave-ho, my lads.”

“That sounds like Roy Blakeley,” Raymond had said to his companion.

“Does sound kinder like his nonsense,” the camp manager had answered.

All through the long winter months Raymond had lived at the big camp with no other companion than Jeb Rushmore. They had made their headquarters in Jeb’s cabin, the other cabins and the big pavilion being shut tight. Raymond had often thought how like the pictures of Valley Forge this vacant clearing in the woods looked in its covering of snow, and sometimes when Jeb was busy writing letters (it was a terrible job for Jeb to write letters) the little fellow had been lonesome, but he had gained in weight, he had slept like a bear, he had ceased entirely to cough, and he ate—there is no way to describe how he ate!

In short, a great fight had been fought out in the lonely camp that winter, and little Raymond Hollister had won it. He could trudge into the village and back without minding it now and he could raise the big flag with one hand. Just the coming summer to top off with and he would be well.

Raymond lived down the Hudson a ways and he had come to Temple Camp with his troop the previous summer. His patrol leader, Garry Everson, had won the Silver Cross, which, according to the rule of the Camp, entitled him and his companions to remain three extra weeks, and when Mr. John Temple had heard of Raymond’s ill health from the Bridgeboro boys on their return from camp, he had called his stenographer and sent a couple of home-runs over the plate in the form of two letters, one to Raymond’s grandmother telling her that she had guessed wrong when she had “guessed that Ray would have to go to an orphan asylum when he came back,” and the other enclosing a check to Jeb Rushmore and telling him that Raymond would stay with him for the winter and to please see to it that he had everything he needed.

That was in the previous autumn. Jeb had gotten out his bespattered, pyramid-shaped ink bottle and his atrocious pen and laboriously scrawled his signature on the back of the check and had it cashed in Leeds. He had kept the little roll of bills carefully in his pocket all winter, buying such things for Raymond as were needed, and as the roll grew thinner Raymond had grown stouter, until now, in the spring, he weighed ninety-one pounds and the roll was all gone except the elastic band.

It seemed a pity that just at the opening of the new season he should have to think of going home and perhaps to an orphan asylum, but if he had entertained any wild hope that some fortunate circumstance might prolong his stay into the open season it had been dissipated when word had come that the Temples had gone to South America. Either John Temple had forgotten about the boy up in the lonely camp or else he felt that he had done as much for him as could be expected. Raymond might still remain for two weeks of the new season as any scout might do, but then he would be at the end of his rope. For the rule of Temple Camp was that any scout or troop of scouts might spend two weeks at the camp free of all cost. If a scout won an honor medal it entitled his whole troop to additional time, the time dependent on the nature of the award. No scout might remain at camp longer than two weeks except in accordance with this provision, but permission might be granted on the recommendation of one of the trustees for a scout to board at camp for a longer time if there were good reason.

One day, however, a registered letter had come for Jeb. It contained fifty dollars and a slip of paper bearing only the words: For Raymond Hollister to stay until September first.

“So he remembered ’baout yer arter all,” Jeb had said, as pleased as Raymond himself. “I kinder knowed he would. If he ain’t a trusty (Jeb always said trusty when he meant trustee) ’n’ got rights, gol, I dunno who has. They wuz jest goin’ on th’boat, I reckon, when it popped inter his head like a dose uv buckshot ’n’ he sent it right from th’wharf.——’ N’ I dun’t hev ter get out my ink bottle ’n’ my old double-barrelled pen ter indorse, neither.”

There they were—two twenties and a ten; to Raymond they seemed like a fortune as he watched Jeb fold them up and slip them into his home-made buckskin wallet.

All this had happened before this auspicious Saturday, but the dispelling of Raymond’s fears had given rise to new apprehensions.

“Even if they come,” said he, “maybe Garry won’t be with them—maybe they won’t stop for him.” Garry Everson was all that was left of the little troop he had striven to keep together the previous summer and the Bridgeboro troop had promised to stop for him and bring him along.

“An’ then agin, mebbe they will,” laughed Jeb.

“Who do you think will be the first to get here, Jeb?”

“Mebbe them lads from South New Jersey, mebbe the Pennsylvany youngsters,” said Jeb, consulting his list from the home-made buckskin wallet. The trustees kept these lists in the neatest and most approved manner, but Jeb had a system of record keeping all his own. “Let’s see, naouw, thar’s thet troop with the red-headed boy from Merryland—’member ’em, don’t ye? They’ll be comin’ all week, more’n like. Seems ony like yist’day, thet that ole hill over thar wuz covered with snow—’member how me an’ you watched it? We had a rough winter of it, didn’t we. Here, lemme feel yer muscle agin now. Gee-williger! Gittin’ ter be a reg’lar Samson, ain’t ye?”

“Now that it’s time for them to come,” said Raymond, slowly, “I’m almost sorry—kind of. It was dandy being alone here with you.”

Jeb slapped him on the shoulder and smiled again that smile that drew the wrinkles like sun rays around his twinkling eyes, and went about his work of preparation. Perhaps he, too, rough old scout that he was, felt that it had been “dandy” having little Raymond alone with him through those long, cold winter months.

All day long Raymond kept his gaze across Black Lake, for he knew that the Bridgeboro boys, hiking it from the Hudson, would come that way; but the hours of the afternoon passed and there were no arrivals. The hills surrounding the camp began to darken in the twilight, save for the crimson tinge upon their summits from the dying sun; the dark waters of the lake grew more sombre in the twilight and the still solemnity of evening, which was nowhere more gloomy and impressive than at this lakeside camp in the hills, fell upon the scene and cast its spell upon the lonely boy as it always did. But no one came.

Jeb Rushmore strolled down to where Raymond sat on the rough bench outside the provision cabin, facing the lake.

“Still watchin’? If yew say so, I’ll light a lantern and we’ll tow a couple uv skiffs across and wait on ’tother side.”

“I wasn’t thinking about them just now, Jeb; I was looking at those birds.”

High up, through the fading twilight, a bird sped above the lake, toward the south. Its course was straight as an arrow. Above it a larger bird hovered and circled but the smaller bird went straight upon its way, as if bent upon some important mission.

Then, suddenly, the larger bird swooped and there was only the one object left in the dim vast sky where, a moment before, there had been two.

“Get me my rifle,” said Jeb.

As Raymond hurried back with it, he could see the wings of the big bird flapping in the fury of its murderous work. What was going on up there he could only picture in his mind’s eye, but the thought of that smaller bird hurrying on its harmless errand—homeward to its nest, perhaps—and waylaid and murdered up there in the lonely half darkness, troubled him and his hand trembled perceptibly as he handed the weapon to Jeb.

“You always hit ’em—fetch ’em—don’t you?” he asked, anxiously.

“Purty near.”

The sharp report rang out and echoed from the surrounding hills. Even before it died away there lay at Raymond’s feet a hawk, quite dead, while through the dim light in a pitiably futile effort to fly, the smaller bird, a vivid speck of white in the fading twilight, fluttered to the ground.

It proved to be a white pigeon, its feathers ruffled and stained with blood and several of the stiffer feathers of the tail were gone entirely. One wing drooped as the bird stumbled weakly about and an area of its neck was bare where the feathers had been torn away. It seemed odd to Raymond that the poor stricken thing should resume its clumsy strut, poking its head this way and that, even in its weakness, and after such a cruel experience.

But what he noticed particularly was a metal ring around the bird’s leg from which hung a little transparent tube, like a large medical capsule, with something inside it.

“Look, Jeb,” said he. “What’s that?”

Jeb lifted the bird carefully, folding the drooping wing into place, and removed the little tube.

“You fetched him anyway, didn’t you, Jeb?”

“’Cause I had ter—see?”

“We won’t have to kill it, will we, Jeb?”

“Reckon not. He don’t seem to be sufferin’ much uv any. Jes’ shook up, as the feller says. Lucky he fell amongst friends. Let’s see wot he’s brought us—he’s one of them carriers, son.”

Raymond said nothing, but watched eagerly as Jeb, leisurely and without any excitement, opened the tiny receptacle and unrolled a piece of paper. The boy knew well enough what carrier pigeons were and he was eager to know the purport of that little roll of script. But even in his excitement there lingered in his mind the picture of that faithful little messenger, intent upon its errand, struck down by the ruthless bandit of the air. He was glad the hawk was dead.

“Let’s hear wot he’s got ter say fer himself, son. You jes’ read it.”

The paper was thin and about the size of a dollar bill; it had been folded lengthwise and then rolled up. It read:

“Come right away. Governor hurt. Serious. Can’t leave. Will try to get to nearest village but am afraid to leave now. He fell and is bleeding bad. Think there’s something else the matter, too. Spotty died or would send.

Jeff.”

Raymond gazed for a moment at Jeb, then down at the dead hawk, then at the pigeon which Jeb still held, stroking it gently.

“It’ll never be delivered now, son, ’cause nobuddy ’cept this here little feller knows whar he come frum nor whar he wuz goin’—do they, Pidge?”

“But somebody’s dying,” said Raymond.

“Sure enough, but we don’t know who ’tis nor whar he is—nor whar his friends is neither. An’ this here messenger here won’t tell us—he’s got his own troubles. That thar hawk done more mischief than he thought for.”

For a few moments there was silence and Raymond gazed up into the trackless, darkening sky through which this urgent call for help had been borne. Where had it come from? For whom was it intended? Then he looked down at the limp body of the bird whose cruel, bloody work had snatched the last faint hope of succor from someone who lay dying.

“I—I’m glad you kil—fetched him, anyway——” said he.

The thought of those two unknown persons, the stricken one and his frightened companion, waiting all in vain for the help which that faithful messenger of the air should summon, and of that steadfast little emissary, on whom so much depended, fallen here into strange hands, sobered and yet agitated the boy, and he was silent in the utter helplessness of doing anything.

“Naow, if yer could ony tell whar yer wuz goin’ or whar yer wuz comin’ frum, Pidge, we’d be much obleeged,” said Jeb; “but you wouldn’t, would yer,” he added, stroking the bird, “’n’ I ain’t much uv a hand at pickin’ trails in th’air, bein’ as I growed up on th’hard ground.”

“Nobody can follow trails in the air,” said Raymond by way of comforting Jeb. “Gee, nobody could do that. But it’s terrible, isn’t it?”

He looked up into the sky again as if he hoped it might still show some sign of path or trail, and as he did so a loud bark, a sort of harsh Haa-Haa, came through the growing darkness from across the lake, and reverberated in swelling chorus from the frowning heights roundabout. Then there was a long, plaintive bellow which died away as softly and as gradually as the day itself dies, and this again was followed, as it seemed, by the happy music of applauding hands, as if in acknowledgment of the long echoed refrain.

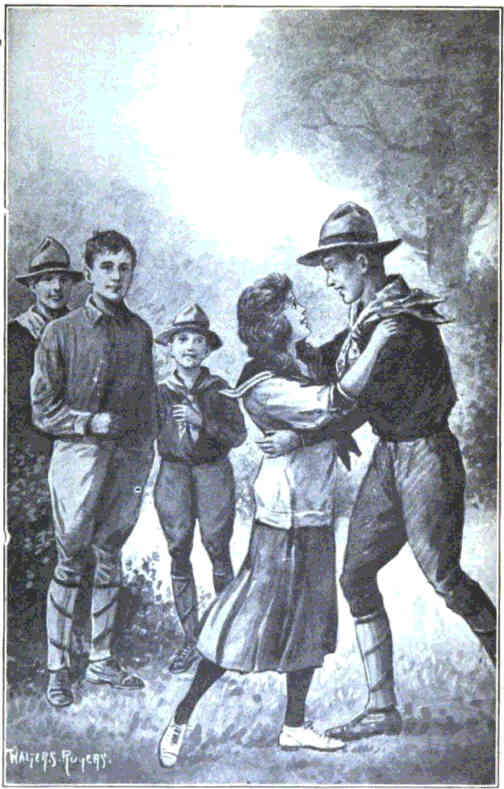

“Oh, they’re here! They’re here!” cried Raymond. “That was the Silver Fox call—and the Elks—and Garry’s with them—he made that Beaver call to let me know——”

Just at that moment the dense brush across the lake parted and a boy, bareheaded and wearing a grey flannel shirt, emerged on the shore.

“Oh, Tom! It’s Tom Slade!” cried Raymond, forgetting all else in his ecstasy. “Hello, Tom, you big—you big——” But he couldn’t think of any epithet to fit the occasion.

“Believe me, it was good to get our feet on terra-cotta—I mean terra firma. I don’t want any more life on the ocean wave for at least two weeks. I’m sorry we didn’t christen that boat the Sardine Box. Good Turn—you can’t even turn around in it!”

“You shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth,” someone laughed.

“You can look a gift boat in the cabin, can’t you,” continued Roy. “We were crowded in the cabin, not a soul would dare to move. That boat is all right for three scouts like last year, but for three patrols—go-o-d night! There wasn’t even room to flop a rice cake over—we had to eat them browned on one side—there was a wrong and a right to them. Never again! What we want is a sump-tu-ous yacht like that one moored at Catskill Landing!”

“Wal, ye did hev quite a crowd aboard, sure enough,” laughed Jeb, who always enjoyed Roy’s nonsense.

“Sure, pick out the one you want and I’ll drown the rest,” said Roy; “except Pee-wee, we’re going to keep him till he gets his eyes open.”

Pee-wee Harris, Silver Fox and troop mascot, splashed the oar from his seat in an adjoining boat, giving Roy a gratuitous bath.

“Did you have any adventures?” Raymond managed to ask.

“Oceans of them—I mean rivers. We got three points out of our course and went twenty miles up a tributary.”

“That’s some word,” someone called.

“That’s a peach of a word, comes from the Greek word Bute, meaning beautiful, and the Irish word Terry. It was all on account of Pee-wee’s ignorance of geography. He thought the Hudson rose in Roseville, Pennsylvania.”

“What!” shouted Pee-wee.

“I’ll leave it to our beloved scoutmaster.”

“Our beloved scoutmaster,” who was rowing one of the skiffs, only smiled.

“I know more about geography than you do,” shouted the irrepressible Pee-wee; “he thought Newburgh was below Peekskill,” he added, contemptuously.

“He thought Sandy Hook was a Scotchman,” retorted Roy. “Well, what’s the news, Jeb, anyway?”

“Yer didn’t give us no chance ter tell yer,” drawled Jeb, as they drew the boats up on shore. “Mebbe yer think yer wuz the fust arrivals, but yer wuzn’t.”

It was good to hear Roy’s familiar nonsense; Raymond, who was quiet and easily amused, saw with joy that the ancient hostilities between Roy and Pee-wee were still in full swing; and for all Roy’s dubious picture of an overcrowded boat (and so it must have been) they had found it possible to stop down the river for Garry Everson and bring him along.

“Last of the Mohicans,” said Roy, as he dragged Garry forward; “all that’s left of the famous Edgevale troop—left over from last summer. The only original has-been. Them wuz the happy days.”

There was Tom Slade, too, quiet and stolid as he always was and with no more sign of the scout regalia than he had shown when he was a hoodlum down in Barrel Alley. His gray flannel shirt and last year’s khaki trousers were in odd contrast to the new outfits which the other members of the Bridgeboro Troop wore. But then Tom was in odd contrast with everything and everybody anyway.

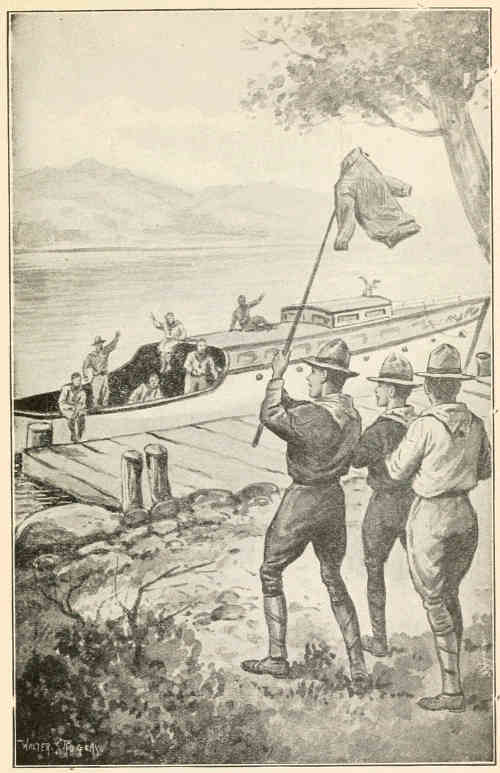

Two troops which had come up by the train had joined them at Catskill Landing so the new arrivals descended like an all-conquering host upon the quiet monotony of the big camp.

“And I’m going to stay till September,” said Raymond, clinging to Garry and talking to both Garry and Roy. “Mr. Temple sent the money. Do you remember how I couldn’t raise the flag last summer?”

“You were about as tough as a Welsbach gas mantel last summer,” laughed Roy.

“Well, now I can raise it with one hand and I can hike to Leeds and back. But listen—listen; we’ve got a mystery—it just happened——”

“Give it to Tom,” laughed Roy. “He’s the fellow for mysteries.”

But in another minute he had abandoned his gay tone as the little company stood gazing down upon the dead hawk, while Jeb held a lantern, and listened to Raymond’s breathless account of what had happened.

It had a sobering effect upon them all, and as Mr. Ellsworth, the Bridgeboro Troop’s scoutmaster, held that pathetic note and read it in the lantern light, with the scouts clustering about him, he shook his head ruefully.

The note was passed about among the boys, who fingered it curiously.

“It’s a stalking blank, isn’t it,” said Tom, as he handed it to Westy Martin, of the Silver Foxes, who wore the stalking badge. “The printed part has been torn off so’s to get it into that little holder. See?” he added, rubbing his finger along the edge, “it came off a pad—a stalking pad—one of——” and he named the sporting goods concern which made them. “It’s the same kind you and I used at Salmon River.”

The announcement, made in Tom’s usual stolid, half-interested way, fell like a bombshell among them.

“Oh, can we find them? Can we find them?” cried Raymond.

“I’m afraid that doesn’t do us much good,” said Mr. Ellsworth. “We already knew that the message was sent from some isolated place or help would have been procurable. That being the case, I don’t see how the sender happened to have a pigeon handy.”

“He had more than one, don’t you see?” said Tom, quietly, “but the other died—Spotty. It must have been sent by some one who’s stalking and a fellow who’s that much interested in birds would be just the kind of a fellow that might have carrier pigeons—it’s good sport.”

“Yes, but where is he—or they? There’s two of them, anyway,” said Doc Carson.

“That’s for us to find out,” said Tom. “I’m not going to sit down here and eat my supper with someone dying.” He kicked the body of the hawk slightly as if to express his disgust that this insignificant creature could cause such trouble and baffle even scouts. “We don’t know much about it but we’ll have to use what little we do know. I know that when people try out carrier pigeons they always get a high ground, and I know that up on that hill over there—in the woods—there were chalk marks on the trees last summer. Maybe someone was stalking there then. Anyway, I’m going to get to the top of that hill and see if I can find anyone up there. I want Doc to go with me. Anybody else can go that wants to. If there’s anybody there we’ll wigwag or [1]smudge it to you in the morning.”

For a moment there was silence. It was exactly like Tom to blurt out his plans with a kind of stolid bluntness, and if he had contemplated a trip to the moon he would have announced it in the same dull way. He seldom asked advice and as seldom asked authority. He was a kind of law unto himself. If anyone knew how to take Tom it was Roy Blakeley, but Roy often threw up his hands in despair and said he gave it up—Tom was a puzzle. He stood there among them now, his face about as expressionless as an Indian’s—coarse gray flannel shirt open halfway down to his waist, a strap by way of a belt, and his shock of thick hair down on his forehead. Why he had eschewed the scout regalia while the others came resplendent in their new outfits was a mystery. What advantage over a belt the thin strap had, no one knew.

“Oh, I’ll go with you! I’ll go with you!” shouted the irrepressible Pee-wee. “I’ll——”

“You’ll just sit down and have some supper,” laughed Mr. Ellsworth.

It is to be feared that the scoutmaster had small hope of anything coming from Tom’s proposed expedition, but he was not the one to discourage his scouts nor obtrude his authority. So the little party was made up (for whatever slight prospect of success it might afford) of Tom, Doc Carson, Raven and First Aid Scout, Connie Bennet of Tom’s patrol, and Garry Everson who, though not a member of the troop, was asked because of his proficiency in signalling. Roy, who would naturally have gone, was asked by Mr. Ellsworth to remain at camp to help him get the troop’s baggage distributed in the several cabins that had been reserved for them.

So the four scouts, having taken a hasty bite of supper, set out in the darkness on their all but hopeless errand. Tom carried a lantern; across Doc Carson’s back was slung the folding stretcher; Connie Bennet carried the bandages and first-aid case, and all wore belt axes, for the hill which they meant to climb was covered with a dense thicket and even in the lower land between it and the camp there was no sign of path or trail after the first mile or so.

“That’s what you get for being small,” sighed Pee-wee to Raymond Hollister, as they strolled about together while waiting for supper. “When you say you want to go with them or tell them about an idea you have, they just laugh at you, or don’t pay any attention. It just goes in one ear and out the other—because there’s nothing to stop it, as Roy says. Gee, you have to laugh at that feller. He makes me awful mad sometimes—when he gets to jollying—but you have to laugh at him.”

“Do you know what he told me last summer?” said Raymond; “he was telling me about the echoes and he said if I called Merry Christmas good and hard it would answer Happy New Year!”

“That’s just like him,” said Pee-wee, “you have to look out for him. When I first joined his patrol he told me a lot of stuff. He said if a feller had a malicious look it was a sign he belonged to the militia. He’ll be jollying you and me all the time we’re here—you see if he isn’t. He calls me a scoutlet. And it’ll be the same with you, only worse, because you’re even smaller than I am. What do you say we stick together?”

“I’ll do it,” said Raymond, “but I like Roy,” he added. “I like him better than any of your patrol—I like him better than Tom Slade—a good deal.”

“Tom isn’t so bad,” said Pee-wee, “but he’s kind of queer.”

“He doesn’t look like a scout at all—not this year,” said Raymond.

“He’s thinking mostly about his patrol,” said Pee-wee, “he’s nutty about his patrol. He needs one more member. Roy and two or three others—Westy, he’s pretty near as bad—they made a big rag doll with a punkin for a head and brought it to scout meeting as a new member for Tom’s patrol. Coming up the river there was a scarecrow in a field and Roy said, ‘There’s your new member for you, Tom.’ Oh, gee, but we did have some fun cruising up. Sometimes I got mad when they kidded me, but most of the time I had to laugh—especially when Roy gave an imitation of a dying radiator—gee, that feller’s the limit!”

Raymond enjoyed these tidbits of gossip about the Bridgeboro Troop, the members of which were all more or less heroes to him.

“I like Garry best of all,” he suddenly announced.

“Everybody likes him,” said Pee-wee.

“He’s just as smart as any scout in your troop,” Raymond added, with the faintest note of challenge in his tone.

The welcome sound of the supper horn brought their talk to an end. It was a merry company that gathered about one of the three long boards (the other two were as yet unused) and to the scouts who were visiting Temple Camp for the first time this late evening meal, served by lantern light under the sombre trees with the still, black lake hard by and the frowning hills encompassing them, was most delightful.

There were few among them (least of all Jeb and the scoutmaster) who believed that anything would be accomplished by Tom’s expedition but even a hopeless enterprise seemed more scoutish than doing nothing and Mr. Ellsworth was certainly not the one to deny his scouts any adventure even though it offered nothing more than a forlorn hope.

After supper some one suggested campfire and soon the cheerful, crackling blaze which seems to typify the very spirit of scouting was luring the boys back from pavilion and cabin and they lolled on the ground about it as it grew in volume and glittered in the black water.

“What d’you say we tell riddles?” suggested Pee-wee.

“All right,” said Roy, who was poking the fire. “Riddle number one, How much is twice?”

“Do you stir your coffee with your left hand?” shouted Pee-wee.

“No, with a spoon,” said Roy; “no sooner said than stung!”

“Tell a story, Roy,” some one called, and half dozen others, who had already fallen under Roy’s spell, chimed in, “Sure, go ahead—story, story!”

“Well,” said Roy, drawing his knees up and clasping his hands about them. “Once there was a scout—anybody got a harmonica for some soft music? No? Well, once there was a scout and he was tracking. He came to a stone wall and in climbing over it he fell.”

“Scouts don’t fall,” shouted the irrepressible Pee-wee.

“Who’s telling this?” said Roy. “As he was climbing over the stone wall he fell. He fell on his face—and hurt his feelings. He was self-conscious—I mean sub-conscious—I mean unconscious. He shouted for help.”

“When he was unconscious?” ventured Raymond.

“Sure. But no help came. The sun was slowly sinking. The scout was a fiend on first-aid. He opened his case and got out a bottle of camphor. He smelled it. He opened his eyes slowly and came to——”

“You make me sick!” shouted Pee-wee.

“There was a big scratch on his knee,” Roy continued. “There was a hole in his stocking—about as big as a seventy-five cent piece. He looked about but could not find the piece of stocking the size of a seventy-five cent piece that had come out of the hole. Where was it? The hole was there—the whole hole; but where was the part of the stocking that had been in the hole? He looked about.”

“Topple him over backwards, will you!” called Pee-wee, in a disgusted appeal to Roy’s nearest neighbor.

“He looked about some more. Then he sat up. Then he sat down. He was a scout—he was resourceful. He happened to remember that once he had eaten a doughnut. The doughnut had a hole in it. The hole disappeared. He said to himself——”

But he was not allowed to go further, for somebody inverted him according to Pee-wee’s suggestion, and when the general laugh had subsided a boy who had said very little spoke up, half laughing but evidently in earnest and greatly interested in Roy.

“While we were rowing across the lake,” he said, “you made some remark about your motor-boat being overcrowded on the trip up and I got an idea from some things that were said that two or three of you came up here alone last year. It struck me that you might have had some interesting experiences from the way you spoke. I wanted to go with your friends off to that hill, but I didn’t just like to ask——”

“That’s the trouble with him,” a smaller boy beside him, who was evidently his friend, piped up. “He doesn’t like to butt in—gee, you’d never think he was a hero from the way he acts—or the way he talks either.”

The older boy took the general laugh good-naturedly. “I was just wondering,” he said, “if you wouldn’t tell us something about your trip.”

“He’s had a lot of adventures, too,” piped up the smaller boy, “and saved people’s lives—and things—and won plaudits——”

“Won what?” someone queried.

“Plaudits,” he repeated; “they are things like—like—well, applause, kind of. But he don’t know very much about girls, though.”

“And what is your name?” asked Mr. Ellsworth, amid the general laughter.

“Gordon Lord—and his is Harry Arnold—he can swim two miles and back and he can—he can—he can make raisin pudding,” he concluded, lamely. “And he’s got a tattoo mark on his arm.”

“Delaware?” Roy queried, smiling across the blaze at Arnold.

“No, New Jersey—Oakwood, New Jersey—First Oakwood Troop—Hawk Patrol, we are. I guess we’re a little bit ashamed of our patrol name just now.”

There was silence for a minute as all thought of the tragic message which had fallen into the camp.

“You should worry about the name,” said Roy.

“I don’t suppose there’s anything we can do,” said Mr. Ellsworth, voicing the thought which held all silent, “but sit here and wait, and if we’re sensible we won’t hope for too much. Come, Roy, let our new friends hear about you boys coming up in the Good Turn.”

“It isn’t that big cruiser down at Catskill Landing, is it?” Arnold inquired. “We saw that as we got off the train.”

“No, that’s the kind of a yacht boys have in twenty-five cent stories,” said Roy; “I saw that one; it’s a pippin, isn’t it? Guess it belongs to a millionaire, hey? No, ours is just a little cabin launch—poor, but honest, tangoes along at about six miles an hour and isn’t ashamed. Do you want the full story?”

“If there aren’t any stockings and stone-walls in it,” someone suggested.

“All right, here goes,” said Roy, settling, himself into his favorite posture before the fire, with his hands clasped about his drawn-up knees and the bright blaze lighting up his face.

“You see, it was this way. Pee-wee Harris is the what’d you say his name is—Lord? Pee-wee Harris over there is the Gordon Lord of our troop. And Tom Slade is our famous detective—Sherlock Nobody Holmes.

“Well, Tom and Pee-wee and I started ahead of the others last summer to hike it up here. Pee-wee got very tired (here he dodged a missile from Pee-wee) and so we were all glad when we got a little above Nyack and things began to happen. They happened in large chunks.

“On the way up Pee-wee captured a pet bird that belonged to a little girl (oh, he’s a regular gallant little lad, he is); he got the bird down out of a tree for her and to show how happy she was she began to cry.”

“Gee, they’re awful funny, ain’t they?” commented Gordon Lord.

“Well, we beat it along till we hit the Hudson, then we started north. The shadows of night were falling.”

“You read that in a book,” interrupted Pee-wee.

Little Raymond was greatly amused. So was Mr. Ellsworth who poked up the fire and resumed his seat on the old bench beside Jeb Rushmore.

“Team work,” someone suggested, slyly, indicating Gordon and Pee-wee.

“The kindergarten class will please be quiet,” said Roy. “I repeat, the shadows of night were tumbling. It began to rain. And it rained, and it rained—and it rained.

“Suddenly, we saw this boat—we thought it was a shanty at first—in the middle of a big marsh. So we plowed our way through the muck and crawled into it. Pity the poor sailors on a night like that!

“Well, believe me, it was too sweet for anything in that old cabin. Pee-wee wasn’t homesick any more (here Roy dodged again) and we settled down for the night. The rain came down in sheets and pillowcases and things and the cruel wind played havoc—I mean it blew—and shook the old boat just as if she’d been in the water. But what cared we—yo, ho, my lads—we cared naught!

“Well, in the morning along came an old codger with a badge and said he was a sheriff. He was looking for an escaped convict and we didn’t suit. He told us the boat was owned by an old grouch in Nyack and said if we didn’t want to be arrested for trespassing and destroying property we’d better beat it. He told us some more about the old grouch, and I guess Pee-wee and I thought the best thing to do was to hike it right along for Haverstraw and not wait for trouble. We had chopped up a couple of old stanchions for firewood—worth about two Canadian dimes, they were, but our friend said old What’s-his-name would be only too glad to call that stealing and send us to jail. Honest, that old hulk was a sight. You wouldn’t have thought anybody would want to admit that he owned such a ramshackle old pile of junk and that’s why we made so free with it.

“Well, zip goes the fillum! Here’s where Tom comes on the scene. He said that if that was the kind of a gink Old Crusty was we’d have to go and see him and tell him what we’d done. He just blurted it out in that sober way of his and Pee-wee was scared out of his——”

This time Pee-wee landed a wad of uprooted grass in Roy’s face.

“Pee-wee, as I said, was—with us (dodging again). The sheriff must have thought Tom was crazy. He gave us a—some kind of a scope—what d’you call it—when they read your fortune?”

“Horoscope?” suggested Arnold, smiling.

“Correct—I thank you. He told us that we’d be in jail by night. You ought to have seen Pee-wee stare. I told him he ought not to kick—he’d been shouting for adventures and here was a good one. So we trotted back to Nyack behind Tom and strode boldly up to Old Crusty’s office and—here’s where the film changes—”

“Go ahead,” said Arnold. “You’ve got me started now.”

“Well, who do you think Old Crusty was?”

“Not the escaped convict!”

“Not on your life! He turned out to be the father of the little girl whose pet bird Pee-wee had captured the day before.”

“The plot grows thinner,” said someone.

“Well, he had all the signs of an old grouch, hair ruffled up, spectacles half-way down his nose—but he fell for Pee-wee, you can bet.

“When he found out who we were (the girl must have told him about us, I suppose) he got kind of interested and when Pee-wee started to explain things he couldn’t keep from laughing. Well, in the end he said the only way we could square ourselves was to take the boat away; he said it belonged to his son who was dead, and that he didn’t want it and we were welcome to it and he’d send us a couple of men to help us launch it. He seemed to feel pretty bad when he mentioned his son and we were so surprised and excited at getting the boat that we just stood there gaping. Gee, how can you thank a man when he gives you a cabin launch?”

Arnold shook his head.

“Well, we spent a couple of days and eight dollars and fifty-two cents fixing the boat up and then, sure enough, along came two men and Mr. Stanton’s chauffeur to jack the boat over and launch her for us. The girl came along, too, in their auto, and oh, wasn’t she tickled! Brought us a lot of eats and a flag she’d made, and stayed to wish us—what do you call it?”

“Bon voyage?”

“Correct—I thank you. Understand, I’m only giving you the facts. We had more fun those three days and that night launching the boat than you could shake a stick at. Well, when we got her in the water I noticed the girl had gone off a little way and kept staring at it. Gee, the boat did look pretty nice when she got in the water. I thought maybe she was kind of thinking about her brother, you know, and it put it into my head to ask one of the men how he died. She didn’t come near us while we talked, but stood off there by herself staring at the launch. You see, it was the first time she’d seen it in the water since he was lost, and she was almost crying—I could tell that.

“Well, this is what the man told me. They said this Harry Stanton and another fellow named Benty Willis were out in the launch on a stormy night. There was a skiff belonging to the launch, and people thought they must have been in that, fishing. Anyway, the next morning, they found the skiff broken and swamped to her gunwale and right near it the body of the other fellow. The launch was riding on her anchor same as the night before. The men said Mr. Stanton was so broken up that he had the boat hauled ashore and a flood carried her up on the marsh where she was going to pieces when we found her. He would never look at her again. They said Harry Stanton could swim and that made some people think that maybe they were run down by one of the big night boats on the Hudson and that Harry was injured—killed that way, maybe.

“Anyway, when the girl got in the auto and said good-bye to us I could see she’d been crying all right, and she said we must be careful and not run at night on account of the big liners.”

“Hmph,” said Arnold, thoughtfully.

“Gee, I’ll never forget that night, with her sitting in the auto ready to start home and the boat rocking in the water and waiting for us. I can’t stand seeing a girl cry, can you? I guess we all felt kind of sober when we said good-bye and she told us to be careful. Tom told her we’d try to do a real good turn some day to pay her back, because we really owed it to her, you know, and there was something in the way he said it—you know how Tom blurts things out—that made me think he had an idea up his sleeve.

“Well, it was about an hour later, while we were sitting on the cabin roof, that Tom sprung it on us. We were going to start up river in the morning; we were just loafing—gee, it was nice in the moonlight!—when he said it would be a great thing for us to find Harry Stanton! Go-o-d ni-i-ght! I was kind of sore at him because I didn’t like to hear him joking, sort of, about a fellow that was dead, especially after what the fellow’s father and sister had done for us, but he came right back at me by pointing to the board we had the oil stove on. What do you think he did? He showed us the letters N Y M P H under the fresh paint and said that board was part of the launch’s old skiff and wanted to know how it got back to the launch. What do you know about that? You see, we had run short of paint and it was thin on that board because we’d mixed gasoline with it. We ought to have mixed it with cod liver oil, hey?

“So there you are,” concluded Roy; “Pee-wee and I just stared like a couple of gumps. Those fellows had been out in the skiff and they couldn’t have used it with that side plank ripped off. And how did it get back to the launch?”

“Sounds as if the man might have been right about the skiff being smashed by a big boat,” said Arnold. “Maybe Harry Stanton was injured and clung to that board. But why should he have pulled it aboard the launch? And what I can’t understand is that nobody should have noticed it except you fellows. Was it in the launch all the time?”

“Yup—right under one of the lockers. Pee-wee and I had hauled it out to make a shelf for the oil stove.”

“But how do you suppose it was no one had noticed it till you fellows got busy with the boat?”

“A scout is observant,” said Roy, laughingly.

“Hmph—it’s mighty interesting, anyway,” mused Arnold. He drummed on a log with his fingers, and for a few moments no one spoke.

“Some mystery, hey?” said Roy, adding a log to the fire.

Several things more or less firmly fixed in his mind had impelled Tom Slade to challenge that wooded hill the dense summit of which was visible by day from Temple Camp.

He knew that high land is always selected for despatching carrier pigeons; a certain book on stalking which he had read contained a chapter on this fascinating and often useful sport and he knew that in a general sort of way there was a connection between carrier pigeons and stalking; one suggested the other—to him, at least. He knew for a certainty that the message had been written on the unprinted part of a stalking blank and he knew also that on the slope of the hill he had seen chalk marks on the trees the previous summer. Tom seldom forgot anything.

All these facts, whether significant or not, were indelibly impressed upon his serious mind, and to him they seemed to bear relation to each other. He believed that the pigeon had been flying homeward, to some town or city not far distant, where the sender perhaps lived and he believed that the pigeon’s use in this emergency had been the happy thought of some person who had taken the bird to the hill only to use for sport. He had no doubt that somewhere in the wilderness of these Catskill hills was a camp where the victim of accident lay, but the weak point was that he was seeking a needle in a haystack.

“I wish we’d brought along the fog horn from the boat,” he said, as they made their way across the open country below the hill; “we could have made a lot of noise with it up there; you can hear a long way in the woods, and it might have helped us to find the place.”

“If the place is up there,” said Doc Carson.

“There’s a trail,” said Tom, “that runs about halfway up but it peters out at a brook and you can’t find any from there on.”

“If we could find the trees where you saw the marks last summer,” said Connie Bennet, “we might get next to some clue there.”

“I can usually find a place where I’ve been before,” said Tom.

“What’s the matter with following the brook when we get to it?” said Garry. “If there’s anyone camping there they’d have to be near water.”

“Good idea,” said Doc.

“That settles one thing I was trying to dope out,” said Tom. “Why should people come as far as that just to stalk?”

“Maybe they’re scouts, camping.”

“They’d have smudged up the whole sky with signals,” said Tom.

“Maybe it’s someone up there hunting.”

“Only it isn’t the season,” laughed Garry. “No sooner said than stung, as Roy would say. Gee, I wish he was along!”

“Same here,” said Doc.

“They’re probably there fishing,” said Tom. “The stalking business is a side issue, most likely.”

“That’s what the little brook whispers to us,” said Doc.

They all laughed except Tom. He was not much on laughing, though Roy could usually reach him.

The woods began abruptly at the foot of the hill and they skirted its edge for a little way holding their lantern to the ground so as to find the trail. But no sign of path revealed itself. Twice they fancied they could see, or sense, as Jeb would have said, an opening into the dense woods and the faintest suggestion of a trail but it petered out in both cases—or perhaps it was imaginary.

“Let’s try what Jeb calls lassooing it,” said Garry.

He retreated through the open field to a lone tree which stood gaunt and spectral in the night like a sentinel on guard before that vast woodland army. Climbing up the tree, he called to Tom:

“Walk along the edge now and hold your lantern low.”

Tom skirted the wood’s edge, swinging his light this way and that as Garry called to him. The idea of trying to discover the trail by taking a distant and elevated view was a good one, but the tree was either too near or too far or the light was too dim, and the four scouts knew not what to do next.

“Climb up a little higher,” called Doc. “They say that when you’re up in an aeroplane you can see all sorts of paths that people below never knew about. I read that in an aviation magazine.”

“The Fly-paper, hey?” ventured Connie. “Look out for rotten branches, Garry.”

Garry wriggled his way up among the small branches, as far as he dared, while Tom moved about at the wood’s edge holding the lantern here and there.

“Nothing doing,” said Garry, coming down.

“We’re up against it, for a fact,” said Doc.

“That’s just what we’re not,” retorted Connie. “It seems we’re nowhere near it.”

“Gee-whillager!” cried Garry as he scrambled down the tree trunk. “Sling me over the peroxide, will you!”

“What’s the matter?” asked Doc, interested at once.

“I’ve got a scratch. What Pee-wee would call an artificial abrasion.”

“Superficial?” laughed Doc, pouring peroxide on a pretty deep scratch on Garry’s wrist.

“See there?” said Garry. “Feel. It’s sticking out from the trunk.”

As Tom held his lantern a small, rusty projection of iron was visible on the trunk of the tree about five feet from the ground.

“Is it a nail?” asked Connie.

“Well-what-do-you-know-about-that?” said Garry. “It’s what’s left of a hook; the tree has grown out all around it, don’t you see?”

It was indeed the rusty remnant of what had once been a hook but the growing trunk had encased all except the end of it and the screws and plate that fastened it were hidden somewhere within the tree.

“That tree has grown about an inch and a half thicker all the way around since the hook was fastened to it,” said Doc.

“It’s an elm, isn’t it?” Garry said.

Tom thought a minute. “Elms, oaks,” he mused, “that means about ten or twelve years ago.”

“There are only two reasons why people put hooks into trees,” said Connie, after a moment’s silence; “for hammocks and to fasten horses to. Nix on the hammocks here,” he added.

“What I was thinking about,” said Tom, “is that if somebody used to tie a horse here it must have been so’s they could go into the woods. The trail goes as far up as the brook. Maybe they used to tie their horses here and go fishing. There ought to be a trail from this tree to where the trail begins in the woods.”

“Probably there was—twelve years ago,” said Doc, dryly.

“The ground where a trail was is never just the same as where one wasn’t,” said Tom, with a clumsy phraseology that was characteristic of him. “It leaves a scar—like. When they started the Panama Canal they found a trail that was used in the Fifteenth Century—an aviator found it.”

“Well, then,” said Garry, cheerfully, “I’ll aviate to the top of this tree again and take a squint straight down.”

“Shut your eyes and keep them shut,” Tom called up to him; “keep them shut till I tell you.”

“Wait till Tom says peek-a-boo!” called Connie.

Tom gathered some twigs that were none too dry, and pouring a little kerosene over them, kindled a small fire about six feet from the tree.

“Can you see down here all right?”

“Not with my eyes shut,” Garry answered.

“Well, open them,” said Tom, “and see if the leaves keep you from seeing.”

“What he means,” called Doc, “is, have you an unobstructed view?”

There was always this tendency to make fun of Tom’s soberness.

“Wait till I look in my pocket,” called Garry. “Sure, I’ve got one.”

“Shut your eyes again and keep them shut,” commanded Tom.

“I have did it,” came from above.

With a couple of sticks which he manipulated like Chinese chopsticks, Tom moved the fire a little to a spot which seemed to suit him better, then retreated with his lantern to the wood’s edge.

“Now,” he called; “quick, what do you see? Quick!” he shouted. “You can’t do it at all unless you do it quick!”

“To your left!” shouted Garry. “Down that way—farther—farther still—go on—more. Hurry up! Just a—there you are!”

The boys ran to the spot where Tom stood and a few swings of the lantern showed an unmistakable something—certainly not a path—hardly a trail—but a way of lesser resistance, as one might say, into the dense wood interior.

“Come on!” said Tom. “I hope the kerosene holds out—I dumped out a lot of it.”

Instinctively, they fell back for him to lead the way and scarcely a tree but he paused to consider whether he should pass to the left or the right of it.

“What did you see?” Connie asked of Garry.

“I couldn’t tell you,” said Garry, still amazed at his own experience, “I don’t know as I saw anything; I suppose I sensed it, as Jeb would say. It was kind of like a little dirty green line from the tree and it kept fading away the longer I had my eyes open. It wasn’t exactly a line, either,” he corrected; “it was—oh, I don’t know what it was.”

“It was a ghost,” said Tom.

“That’s a good name for it,” conceded Garry.

“It’s the right name for it,” said Tom, with that blunt outspokenness which had a savor of reprimand but which the boys usually took in good part.

“That’s just about what I’d say it was,” Garry agreed.

“That’s what you ought to say it was,” said Tom, “because that’s what it was.”

Doc winked at Garry, and Connie smiled.

“We get you, Steven,” he said to Tom.

“Even before there were any flying machines, scouts in Africa knew about trail ghosts,” Tom said. “They’re all over, only you can’t see them—except in special ways—like this. You can only see them for about twenty seconds when you open your eyes. If I’d have told you to look cross-eyed you could have seen it better.”

“Wouldn’t that have been a sight for mother’s boy!” said Garry. “Swinging on a thin branch on the top of a tree and looking cross-eyed at a ghost! I’d have had that Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland beaten a mile.”

“Captain Crawford who died,” said Tom, “picked up a lot of them. The higher up you are the better. In an aeroplane you needn’t even shut your eyes.”

“Well, truth is stranger than friction, as Roy says,” said Connie; “this trail we’re on now is no ghost, anyway—hey, Tomasso?”

Tom did not answer.

“I got a splinter in my finger, too,” said Garry.

“Must have been scratching your head,” said Connie.

“That’s what I get from seein’ things,” said Garry.

“We’ll string the life out of Pee-wee, hey?” said Doc. “Tell him we saw a ghost——”

“We did,” Tom insisted.

“You mean Garry did,” said Doc. “Of course, we have to take his word for it.”

“Buffalo Bill saw them, too,” said Tom, plodding on.

“Not Bill Cody!” ejaculated Doc, winking at Garry.

“Yes,” said Tom.

“Is it possible?” said Doc, “Where’d you read that—in the Fly-paper?”

“There’s a trail ghost a hundred miles long out in Utah that nobody on the ground ever saw. Curtis followed it in his biplane,” said Tom.

“Fancy that!” said Doc.

Tom plodded on ahead of them, in his usual stolid manner. “I don’t say you can always do it,” he said; “it’s kind of—something—there’s a long word—sike——”

“Psychological?” said Doc. “We get you, Tomasso.”

“I bet there are real ghosts in here,” said Garry, as they climbed the slope which became more difficult as they went along.

“Regular ones, hey?” said Doc.

“Sure, the good old-fashioned kind.”

“No peek-a-boo ghosts,” said Garry.

“Well, you can knock ghosts all you want to,” said Connie, “but I always found them white.”

“Slap him on the wrist, will you!” called Doc. “Believe me, this is some impenetrable wilderness!”

“How?”

“Impenetrable wilderness—reduced to a common denominator, thick woods.”

Withal their bantering talk, it seemed indeed as if the woods might be haunted, for with almost every step they took some crackling or rustling sound could be heard, emphasized by the stillness. Now and again they paused to listen to a light patter growing fainter and fainter, or a sudden noise as of some startled denizen of the wood seeking a new shelter. Ghostly shadows flitted here and there in the moonlight; and the night breeze, soughing among the tree tops, wafted to the boys a murmuring as of some living thing whose elusive tones now and again counterfeited the human voice in seeming pain or fear.

The voices of the boys sounded crystal clear in the solemn stillness. Once they paused, trying to locate an owl which seemed to be shrieking its complaint at this intrusion of its domain. Again they stopped to listen to the distant sound of falling water.

“That’s the brook, I guess,” said Tom.

Their approach to it seemed to sober the others, realizing as they did that effort and resourcefulness were now imperative, and mindful, too, though scarcely hopeful, that these might bring them face to face with a tragic scene.

“Pretty tough, being up here all alone with somebody dying,” said Doc.

“You said something,” answered Garry.

They were entering an area of underbrush, where the trail ceased or was completely obscured, so that there wasn’t even a ghost of it, as Doc remarked. But the sound of the water guided them now and they worked their way through such a dense maze of jungle as they had never expected to encounter outside the tropics.

Tom, going ahead, tore the tangled growth away, or parted it enough to squeeze through, the others following and carrying the stretcher and first-aid case with greatest difficulty.

“How long is this surging thoroughfare, I wonder,” asked Garry.

“Don’t know,” said Tom. “I don’t seem to have my bearings at all.”

After a little while they emerged, scratched and dishevelled, at the brook which tumbled over its pebbly bed in its devious path downward.

“We’re pretty high up, do you know that?” Doc observed.

“I don’t see as there’s much use hunting for marked trees,” Tom said. “I must have come another way before. I don’t know where we’re at. What d’you say we all shout together?”

This they did and the sound of their upraised voices reverberated in the dense woods and shocked the still night, but no answering sound could be heard save only the rippling of the brook.

“We stand about as much chance as a snowball in a blast furnace,” said Garry.

“The thing to do,” said Tom, ignoring him, “is to follow this brook, somebody on each side, and look for a trail. If there’s anybody here they’ll be upstream; it’s too steep from here down. And one thing sure—they’d have to have water. Lucky the moon’s out, but I wish we had two lanterns.”

“We’ll be lucky if the oil in this one lasts,” Doc put in.

Following the stream was difficult enough, but it was easier than the forest they had just come through and they picked their way along its edge, Tom and Garry on one bank and Doc and Connie on the other.

“I don’t believe anyone’s been in this place in a thousand years; that’s the way it looks to me,” said Doc.

“I’d say at least three thousand,” said Garry.

Tom paid no attention. He had paused and was holding his lantern over the stream.

“Those four stones are in a pretty straight line,” he said. “Would you say that was a ford?”

“Looks more like a Buick to me,” said Garry, but he added, “They are in a pretty straight line. I guess it’s a flivver, all right.”

“Look on that side,” said Tom, to the others. “Do you see anything over there?”

He was looking carefully along the edge; of the water when Doc called suddenly,

“Come over here with your light, quick!”

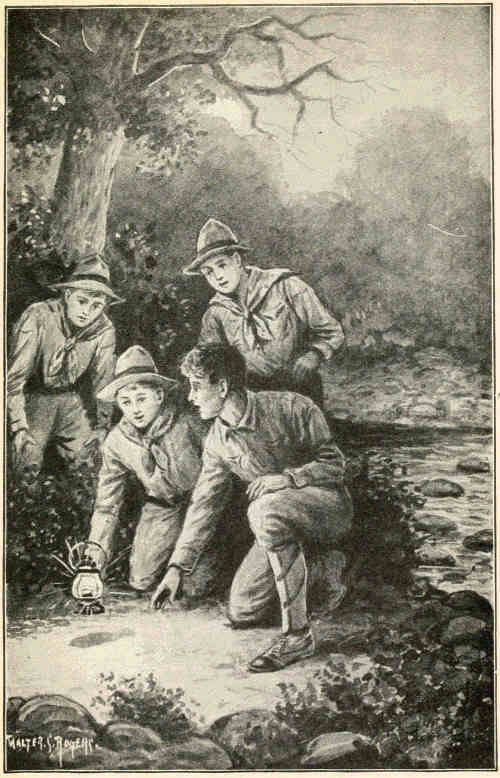

Tom and Garry crossed, stepping from stone to stone, and presently all four were kneeling and examining in the lantern light one of those commonplace things which sometimes send a thrill over the discoverer—a human footprint. There upon that lonesome mountain, surrounded by the all but impenetrable forest, was that simple, half-obliterated but unmistakable token of a human presence. Tom thought he knew now how Robinson Crusoe felt when he found the footprint in the sand.

The exposed roots of a tree formed ridges in the hard bank, where footprints seemed quite impossible of detection, and it was in vain that the boys sought for others. Yet here was this one, and so plain as to show the criss-cross markings of a new sole.

“It’s from a rubber boot,” said Garry.

“There ought to be some signs of others even if they’re not as clear as this one,” said Tom. “Maybe whoever was wearing that boot slipped off one of those stones and got it wet. That’s why it printed, probably. Anyway, somebody crossed here and they were going up that way, that’s sure.”

They stood staring at the footprint, thoroughly sobered by its discovery. They had penetrated into this rugged mountain in the hope of finding some one, but the remoteness and wildness of the place had grown upon them and the whole chaotic scene seemed so ill-associated with the presence of a human being that now that they had actually found this silent token it almost shocked them.

PRESENTLY ALL FOUR WERE EXAMINING—A HUMAN FOOTPRINT.

“Maybe the wind was wrong before,” said Tom. “What d’you say we call again—all together? There don’t seem to be any path leading anywhere.”

They formed their hands into megaphones, calling loud and long, but there was no answer save a long drawn out echo.

“Again,” said Tom, “and louder.”

Once more their voices rose in such stentorian chorus that it left them breathless and Connie’s head was throbbing as from a blow.

“Hark!” said Doc. “Shhh.”

From somewhere far off came a sound, thin and spent with the distance, which died away and seemed to mingle with the voice of the breeze; then absolute silence.

“Did you hear that?”

“Nothing but a tree-toad,” said Garry.

They waited a minute to give the answering call a rest, if indeed it came from human lips, then raised their voices once again in a long Helloo.

“Hear it?” whispered Connie. “It’s over there to the east. That’s no tree-toad.”

Whatever the sound was, the distance was far too great for the sense of any call to be understood. The voice was impersonal, vague, having scarce more substance than a dream, but it thrilled the four boys and made them feel as if the living spirit of that footprint at their feet was calling to them out of the darkness.

“Even still I think it must be near the stream though it sounds way off there,” Tom pointed; “we might head straight for the sound or we might follow the stream up. It may go in that direction up a ways.”

They decided to trust to the brook’s guidance and to the probability of its verging in the direction of the sound. It wound its way through intertwined and over-arching thickets where they were forced to use their belt-axes to chop their way through. Now and again they called as they made their difficult way, challenged almost at every step by obstructions. But they heard no answering voice.

After a while the path became less difficult; the very stream seemed to breathe easier as it flowed through a comparatively open stretch, and the four boys, torn and panting, plodded along, grateful for the relief.

“What’s that?” said Garry. “Look, do you see a streak of white way ahead—just between those trees?”

“Yes,” panted Connie. “It’s a tent, I guess—thank goodness.”

“Let’s call again,” said Tom.

There was no answer and they plodded on, stooping under low-hanging or broken branches, stepping cautiously over wet stones and picking their way over great masses of jagged rock. Never before had they beheld a scene of such wild confusion and desolation.

“Wait a minute,” said Tom, turning back where he stood upon a great rock and holding his lantern above a crevice. “I thought I saw something white down there.”

They gathered about him and looked down into a fissure at a sight which unnerved them all, scouts though they were. For there, wedged between the two converging walls of rock and plainly visible in the moonlight was a skeleton, the few brown stringing remnants depending from it unrecognizable as clothing.

Tom reached down and touched it with his belt-axe, and it collapsed and fell rattling into the bed of the cleft. He held his lantern low for a moment and gazed down into the crevice.

“This is some spooky place, believe me,” shivered Connie. “Who do you suppose it was?”

A little farther on they came upon something which apparently explained the presence of the skeleton. As they neared the spot where they had seen what they thought to be a tent among the trees, they stopped aghast at seeing among the branches of several elms that most pathetic and complete of all wrecks, the tattered, twisted remnants of a great aeroplane. A few silken shreds were blowing about the broken frame and beating against the network of disordered wires and splintered wood.

For a few moments they stared at the wreck and said nothing.

“Maybe it was Kinney,” suggested Doc, at last. “Do you remember about Kinney?”

“Come on,” urged Tom.

Half reluctantly the others followed him, glancing back now and again till the tattered mass became a shadowy speck and faded away in the darkness.

“He started from somewhere above Albany,” said Doc, “and he was never heard of again. I often heard my father speak about it and I read about it in that aviation book that Roy loaned me.”

“He’s going to loan it to me when he gets it back from you,” said Connie; “he says you’re a good bookkeeper.”

“Put away your little hammer,” laughed Garry.

“Some people in Poughkeepsie thought they heard the humming of the engine at night,” said Doc, “and that’s what made people think he had got past that point—but that’s all they ever knew. Some thought he must have gone down in the river.”

“How long ago was it?” Garry asked.

Tom plodded on silently. It was well known of Tom that he could not think of two things at once.

“Five or six years, I think,” said Doc.

“That would be too long a time for the wreck, seeing the condition it’s in,” said Garry, “but anything less than that would be too short a time for the skeleton.”

“Do you mean they were lost here at different times?” Connie asked.

“Looks that way to me.”

“If there are buzzards up here a skeleton might look like that in a month or so,” Connie suggested.

“There aren’t any buzzards around here.”

“Sure there are,” said Doc. “Look at Buzzard’s Bay—it’s named for ’em.”

“It’s named for a man who had it wished on him,” said Garry. “You might as well say that Pike’s Peak was named after the pikers that go there.”

“How long do you suppose that aeroplane’s been there?”

“Five or six years, maybe,” Doc said. “The frame’ll be as good as that for ten years more. There’s nothing more to rot.”

“Well,” said Garry, “it looks to my keen scout eye as if that wreck had been there for about six months and the skeleton for about six years.”

“Maybe if you had tried shutting your keen scout eye and opening it in a hurry—— Hey, Tomasso?” teased Doc.

“Maybe they got here at the same time but the man lived for a while,” Tom condescended to reply.

“You’ve got it just the wrong way round, my fraptious boy,” said Doc. “The skeleton’s been here longer, if anything.”

“Did you see that hickory stick there—all worm-eaten?” Tom asked. “It had some carving on it. None of these trees are hickory trees.”

“I saw it but I didn’t notice the carving,” said Doc, surprised.

“Didn’t you notice there weren’t any hickory trees anywhere around there?” Tom asked.

“No, I didn’t—I’m a punk scout—I must be blind,” said Doc.

“You’re good on first-aid,” said Tom, indifferently.

“How’d you know it was hickory?” Connie asked.

“Because I can tell hickory,” said Tom, bluntly, “and it’s being all worm-eaten proved it—kind of. That’s the trouble with hickory.”

They always had to make the best of Tom’s answers.

“I don’t know where he got the hickory stick,” he said, as he pushed along through the underbrush, “but he didn’t get it anywhere around here, that’s sure.”

“And he probably didn’t sit down that same day and carve things on it, either,” suggested Garry; “Tom, you’re a wonder.”

“He might have lived up here for two or three years after he fell,” said Doc reflectively. “Gee, it starts you thinking, don’t it?”

Connie shook his head. “It’s a mystery, all right,” said he.

The thought of the solitary man, disabled crippled, perhaps, living there on that lonely mountain after the terrible accident which had brought him there lent a new gruesomeness to their discoveries. And who but Tom Slade would have been able to keep an open mind and to see so clearly by the aid of trifling signs as to separate the two apparent catastrophes and see them as independent occurrences?

“Tomasso, you’re the real scout,” said Doc. “The rest of us are only imitations.”

Tom said nothing. He was used to this kind of talk and was about as proof against such praise as a battleship is against a popgun. And just now he was thinking of other things. Yet if he could have looked into the future and seen there the extraordinary explanation of his discovery and known the strange adventures it would lead to, he might have paused, even on that all but hopeless errand of rescue, and looked again at those pathetic remains. But those things were to be reserved for another summer.

“Is there anything we can do? What do you suggest, Tom?” Garry asked, dropping his half flippant manner.

“I say, let’s shout again,” said Tom. “We must be nearly a mile farther on by now, and the brook’s getting around to the east, too.”

“Good and loud,” said Connie.

“All together—now!”

Again their voices woke the mountain echoes. A sudden rustling of the underbrush told of some frightened wood creature. The brook rippled softly as before. There was no other sound, and they waited. Then, from somewhere far off came the faint answering of a human voice. It would never have been distinguishable save in that deathlike stillness and even there it sounded as if it might have come from another world. It seemed to be uttering the letter L in a kind of doleful monotony.

They paused a moment in a kind of awe, even after it had ceased.

“It’s calling help,” said Garry.

“I can go there now,” said Tom. “The brook probably winds around that way, but we can cut across and get there quicker. We’ll chop our way through here. Let him rest his lungs now—I can go right for a ways. I got to admit I was wrong.”

In the dim light of the lantern Garry looked at Tom as he stood there, his heavy, stolid face scratched by the brambly thicket, his coarse shirt torn, his thick shock of hair down over his forehead—no more elated by triumph than he would have been discouraged by defeat, and as the brighter, more vivacious and attractive boy looked at him he was seized with a little twinge of remorse that he had made game of Tom’s clumsy speech and sober ways.

“Got to admit you were wrong how—for goodness’ sake?” he said, almost angrily. “Didn’t you bring us here? Didn’t you bring us all the way from Temple Camp to where we could hear that voice calling for help? Didn’t you?”

“I said I could find the trees that had the stalking marks last summer,” said Tom, “and I got to admit I was wrong, ’cause I couldn’t.”

“Who was it that wouldn’t sit down and eat supper while somebody was dying?” demanded Doc. “There’s a whole lot of good scouts, believe me, but there’s only one Tom Slade!”

It was always the way—they made fun of him and lauded him by turns.

“There’s a kind of trail here,” said Tom, unmoved, “but it hasn’t been used for a long time—see those spider webs across it? Lend me your axe, will you, mine is all dulled.”

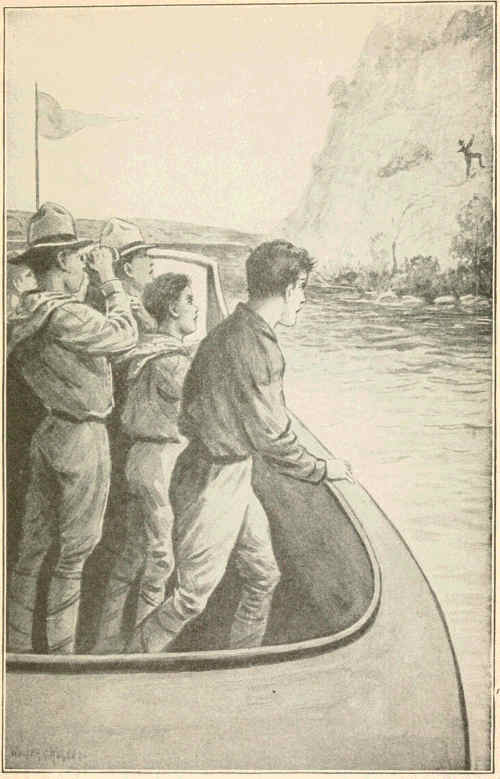

A hand-to-hand combat with more tangled underbrush, which they tore and chopped away, brought them to comparatively open land which must have been very high for they were surprised to see, far below, several twinkling specks of light which they thought to be at Temple Camp. It was the first open view they had had.

They called again, and again the voice answered, clearly audible now, crying, “Help help!” and something more which the boys could not understand. They called, telling the speaker not to come in search of them, that they would come to him, and to answer them for guidance when they called.

They plunged into more thicket, tearing it aside with a will, sometimes going astray, then pausing to listen for the guiding voice, and pushing on again through the labyrinth.

After a little they fell into a path and then could hear the brook rushing over stones not far distant, and knew that it must verge to the east as Tom had said and that the path did lead to it. It would have been a long journey following the stream.

Soon a greater intercourse of speech was possible and they called cheerily that they were scouts and for the waiter to cheer up for they would soon be with him.

Presently, along the path they could hear the sound of footsteps. Tom, who was leading the way, raised his lantern and just beyond the radius of its flickering light they could see a dark figure hurrying toward them; then a face, greatly distraught in the moonlight, and Tom stopped, bewildered. As the stranger grasped his arm he held the light close to the haggard, wild-eyed face.

“Hello,” he said, “I—I guess I know you. Let go—what’s the matter? Weren’t you at Temple Camp last summer?”

The stranger, a young fellow of perhaps eighteen, shook his head.

“With one of the troops from——?”

“No,” said the young man.

“Hmn,” said Tom, still holding the lantern up; “I thought——Don’t you fellows remember him?”

Connie shook his head; Garry also.

“Never saw him in my life,” said Doc.

“Hmn,” said Tom. “Maybe I——just for a minute I thought——I guess you fellows are right.”

The stranger was dressed in the regulation camping outfit—the kind of costume usually seen on dummies in the windows of sporting goods stores in the spring, with a spick and span tent in the background, a model lunch basket near by and a canoe crowded in. His nobby outfit was very much the worse for wear, however, and he looked about as fresh as the immaculate Phoebe Snow would look after a real railroad journey.

“Maybe I can be rescued now,” he said imploringly, clinging to Tom. “I saw the lights way down there. There was only one till tonight and tonight I counted seven—little bits of ones. I tried to get to them, but I got lost. You can’t go to them. It looks as if you can, but you can’t. They’re just as far away, no matter how far you go—they get farther and farther. Nobody can ever get away from here. Are you afraid of dead people?”

“No,” said Doc. “We’re scouts. Is——”

“If a person looks very different, then he’s dead, isn’t he?”

“Come on,” said Doc. “We’ll see.”

“We’ll never get off this hill; I’ve tried every way——”

“Oh, yes, we will,” spoke up Garry, putting his arm over the boy’s shoulder and urging him along.

They could see that he was hardly rational, and Garry, better than any of the others, knew how to handle him.

“It’s terrible without a light,” he said; “I spilled all the oil—I’m glad you’ve got a light.”

“What’s your name?” Garry asked.

“Jeffrey Waring—come on, I’ll show you the place.” He shuddered as he spoke.

Once more Tom held his lantern up to the white, distracted face.

“He was never at camp,” laughed Doc.

“Hmn,” said Tom, apparently but half convinced.

A few steps brought them to a little clearing where stood a rough shack. Outside it, fastened against a tree, was a vegetable crate with bars nailed across it—the silent evidence of departed pets. Several fishing rods lay against a tree. Close by was a makeshift fireplace. On a rough bunk inside the shack lay a man, no longer young, with iron gray hair. His eyes were open and staring and one seemed larger than the other. Doc felt his pulse and found that he was living.

“He fell on the rocks and hurt his arm—I think it’s broken,” said Jeffrey. “It bled and I bandaged it.”

Doc raised the bandaged arm and it fell heavily. Removing the bandage carefully he saw that the cut itself was not dangerous, but from first-aid studies he thought the man was suffering from an apoplectic stroke or something of that nature. He wondered if the injury to the arm had not been incidental to the man’s seizure and sudden fall. People sometimes lingered in an unconscious condition for days, he knew. It was hardly a case for first-aid, but it was certainly a case for skill and resource, for whatever happened the patient, dead or living, would have to be taken away from this mountain camp.

With Garry’s help, he raised the victim into a recumbent posture, piling everything available under the head while Connie hurried back and forth to the brook, bringing wet applications for the head and neck.

There was no sign of returning consciousness and the question was how to get the patient away down to Temple Camp where medical aid might be had, and where any contingency might be best handled.

The four boys, greatly hampered in their discussion by Jeffrey, whose long vigil had brought him to the verge of collapse, decided that it would be quite useless to signal for help, since it would mean another expedition with most of the difficulties of their own, even if attempted after daybreak.

So they decided to wait for dawn, which happily would come soon, and with the first sign of it to send a smudge signal that they were coming and to have a doctor at camp. They believed that in the daylight they could carry the patient back over the same path which they had so laboriously opened and though delay was irksome this plan seemed the only feasible one to follow.

Despite their weariness none could sleep, so they kindled a little fire and sat about it chatting while they counted time, impatiently waiting for the first streak of daylight.

It was then that they learned from the overwrought boy something of his history, but they got it piecemeal and had to patch together as best they could his rather disjointed talk.

“Is he your father?” Doc asked.

“No, he’s my uncle,” said Jeffrey. “He isn’t a real governor; I only call him that. He’s eccentric—know what that is? If we hadn’t come trout fishing it would have been all right. I could have sent my pigeons from the boat—I’ve got a regular coop there—it cost thirty dollars.”

“But you like the stalking, don’t you?” Connie asked.

“Yes, but I can’t be quiet enough—I can’t sneak up to them. You have to be quiet and stealthy when you stalk.”

They made out that Mr. Waring was something of a sportsman and was wealthy and eccentric.

“We live in a big house in Vale Centre,” Jeffrey told them, “and we have fountains and I have twenty-seven pigeons and two dogs—and I can have anything I want except an automobile. I can’t have an automobile because I’m nervous.”

“You don’t mean you live near Edgevale Village, down the Hudson?” Garry asked in surprise. “I live about two miles from the Centre myself.”

“We live in a house that cost thousands and thousands of dollars, but I like our boat best. If there’s a war we’re going to give it to the government, but if there isn’t any war it’s going to be mine some day.”

It appeared that Jeffrey and his uncle lived alone, save for the servants, and had cruised up the Hudson to Catskill Landing in their boat for the trout fishing of which the old gentleman was fond. How the pair had happened to penetrate to this isolated spot was not quite clear, but the boys gathered that it had been a favorite haunt of Mr. Waring’s youthful days.

“He told me he’d bring me and show me,” said Jeffrey, “and that we’d stay here and catch fish and I could send my pigeons back to James—he’s our chauffeur—and I’d get better so’s I could remember things better. Do you think you get better living in the woods?”

“Surest thing you know,” said Garry.

The picture of the kindly old gentleman, bringing his none too robust nephew to this lonely spot, which lingered in his memory perhaps as the scene of woodland sports of his own boyhood, touched the four boys and seemed to bring them in closer sympathy with the figure that lay prone and motionless within the little shack.

“I can have anything I want,” Jeffrey told them again. “Spotty cost fifty dollars, but he died. That’s because I was sick and my brain didn’t work good. My other carrier cost thirty dollars and I sent him to James to tell him the governor was hurt.”

The scouts told him the fate of the pigeon and of how they had received the message.

“But we’ll never get away from here,” Jeffrey said hopelessly. “We’ll never find our way back.”