This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Bobs, a Girl Detective

Author: Grace May North

Release Date: February 19, 2013 [eBook #42133]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BOBS, A GIRL DETECTIVE***

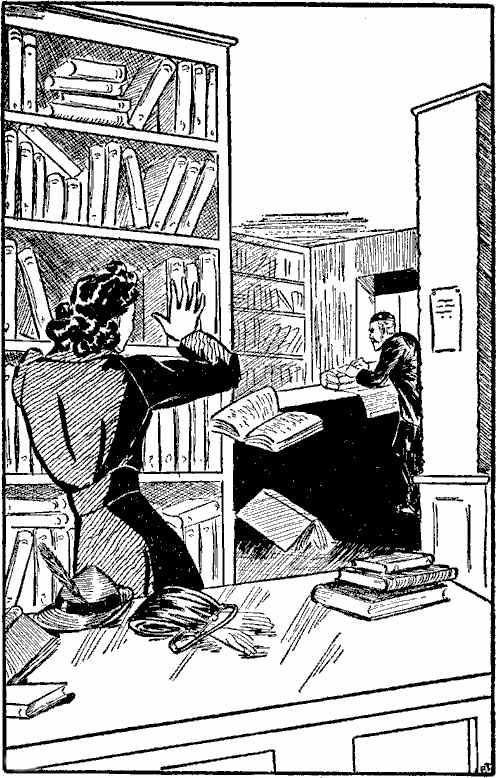

During his absence she went back of the counter.

By CAROL NORTON

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

AKRON, OHIO NEW YORK

Copyright MCMXXVIII

By THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING CO.

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

“Now that the crash is over and the last echo has ceased to reverberate through our ancestral halls, the problem before the house is what shall the family of Vandergrifts do next?”

“Gloria, I do wish you wouldn’t stand there grinning like a Cheshire cat. There certainly is nothing amusing about the whirlwind of a catastrophe that we have just been through and are still in, for that matter.” Gwendolyn tapped her bronze-slippered toe impatiently as she sat in a luxuriously upholstered chair in what, until this past week, had been the library in the Long Island home of the proud family of Vandergrifts.

Gloria, the oldest of the four girls, ceased to smile but the pleasant expression, which was habitual to the blue eyes, did not entirely vanish as she inquired, “What would you have me do, Gwen? Fret and fume as you are doing? That is no way to readjust your life to new and changed conditions. Face the facts squarely, say I, and then try to find some way to surmount your difficulties. Now first of all, we ought——”

The dark, handsome Gwendolyn, whose natural selfishness was plainly portrayed in a drooping mouth and petulant expression, put her fingers in her ears, saying: “If you are going to preach, I can assure you that I am not going to listen; so you might as well save your breath until——”

“Hush. Here comes Lena May in from the garden. Don’t let her hear us scrapping. It effects her sensitive soul as discord effects a true musician.”

Lena May entered through the porch door, her arms filled with blossoming branches.

“Look, sisters, aren’t apple blossoms even sweeter than usual this year?” the slip of a girl began, then paused and glanced from one face to the other. “Gwen, what is wrong?” she asked anxiously.

But it was Gloria who replied, “Nothing at all, Pet. That is, nothing ‘wronger’ than usual, if you will permit my lapse of grammar.”

But the dark-eyed sister threw down the book which she had been trying to read, as she exclaimed, “You both know perfectly well than nothing could be in more of a muddle than our lives are at the present moment and your ‘look for the silver lining,’ philosophy, Gloria Vandergrift, doesn’t help me in the least.”

The fawn-like eyes of the frail, youngest sister turned inquiringly toward the oldest. “Has anything more happened, I mean, anything new?” she asked.

“Yes, dear, we had a letter from Father’s lawyer and he states than beyond a doubt our place here on Long Island does not belong to us and, for that matter, it never did really. Grandfather bought it in good faith, I am sure, but he did not receive a clear title.”

“Then why doesn’t our lawyer clear it up? That’s what I’d like to know,” Gwen said, throwing herself petulantly into another position. “Why did Father employ him, if he cannot attend to our legal matters?”

“But, Gwen, dear, can’t you understand?” Gloria began to explain with infinite patience. “When Father died, leaving four orphaned daughters, we knew that the fortune he had inherited had been lost through unwise investments, but we did think that the income from this vast acreage and the tenants would be sufficient to permit us to live in about the same comfortable way that we always have, but now we find that even this place is not ours and that we are—well, up against it, as Bobs would say.”

“Where is Bobs?” This from Lena May, who was arranging the sprays of apple blossoms in a large pale-green bowl on a low wicker stand.

“Look out of yonder window and you will see the object of your inquiry,” Gloria laughed as she pointed toward the park-like grounds where a hoidenish young girl of 17 could be seen riding astride a slender high-spirited black horse with a white star in his forehead.

“I do wish Roberta wouldn’t wear that outlandish costume,” Gwendolyn began, “and what’s more I can’t see why she wants to be galloping around the country in that fashion when a calamity like this is staring us in the face.”

The horse had disappeared beyond the shrubbery. The sisters supposed that the young rider would go down to the stables and so they were somewhat startled, a second later, by seeing Bobs vault over the sill of an open window and land in their midst.

Gwendolyn, of course, rebuked her. “Roberta Vandergrift, aren’t you ever going to become ladylike?” she admonished.

The newcomer was about to retort that she hoped not if Gwen was a sample, but Gloria intervened. “Don’t be ladylike, Bobs,” she said. “Now, more than ever, we need a man in the family. But come, let’s talk peaceably together and decide what we are to do.”

“All right,” Roberta tossed her hat to one side and sat tailor-wise on the floor, adding: “Fire ahead, I’m present.”

“Such language,” was what Gwendolyn refrained from saying, but Bobs chuckled in wicked glee. She thought it jolly fun to shock “Miss Prunes and Prisms,” as she called the sister but one year her senior.

“Gloria, whatever you suggest, I know will be best,” little Lena May said, as she slipped a trusting hand into that of the oldest sister. “Now, tell us, what is your plan?”

The oldest girl was thoughtful for a moment, then said: “Honestly, I don’t know that I have made one very far ahead, but of course we must leave here. That is the inevitable, and, equally of course, we must find some way of earning our daily bread.”

“Bread, indeed,” sniffed the disdainful Gwendolyn. “You know that I never eat such a plebian thing as bread.”

“Well, you may work to earn cake if you prefer,” Bobs told her, then leaning forward she added eagerly: “I say, Gloria, it’s going to be a great adventure, isn’t it? I’ve always been so envious of people who actually earned their own way in the world. It shows there is something in them. Anyone can be a parasite, but the person who is worth while isn’t contented to be one. Ever since Kathryn De Laney went to little old New York town to take a course in nursing that she might do something big in the world, I’ve had the itch to do likewise. Getting up at noon and then dwaddling away the hours until midnight is all very well for those who like it, but not for mine! I’ve been wishing that something would jar us out of the rut we’re in, and I, for one, am glad that it has come.”

“Kathryn De Laney is a disgrace to her family.” This, scornfully, from Gwen. “A girl with a million in her own name could hire people to do all the nursing she wished done without going into dirty, slummy places herself, and actually waiting on immigrants, the very sight of whom would make me feel ill. I never even permit Hawkins to drive me through the poorer sections of the city and, if I am obliged to pass through the tenement district, I close the windows that I need not breath the polluted air; and I also draw the curtains.”

“I’ve no doubt that you do,” Bobs said, eyeing her sister almost coldly. “I sometimes wonder where our mother got you, anyway. You haven’t one resemblance to that dear little woman who, when the squalid hamlet down by the sound was burned, opened her home and took them all in. We were too small to remember it ourselves, but I’ve heard Father tell about it time and again, and he would always end the story by saying, ‘My dearest wish is that my four girls each grow up to be just such an angel woman as their mother was.’”

“Nor was that all,” Lena May put in, a tender light glowing in her soft brown eyes. “Mother herself superintended the rebuilding of the hamlet which has now grown to be the model town along the sound.” Then, looking lovingly up at the oldest sister, she continued: “I’m glad, Gloria, that you are so like our mother. But you haven’t as yet told me your plan and I am sure that you must at least have the beginning of one.”

“Well, as I said before, we must leave here and go to work,” Gloria replied. “I suppose the best thing would be for us to go to New York, where so many varieties of endeavor await us. Mr. Corey thinks that there will be about one hundred dollars a month for us to live on. That will be twenty-five dollars for each of us, and——”

“Twenty-five dollars, indeed? I can’t even get a hat for that, and I certainly shall need one to wear to Phyllis De Laney’s lawn party on the 18th of June if——”

“But you won’t be here then, Gwen, so you might as well not plan to attend,” Gloria said seriously. “We are obliged to vacate this place by the first of June. The Grabbersteins, who claim their ancestors were the original owners, will move in on that day, bag and baggage, and so my suggestion is that we leave the week previous, that we need not meet them.”

“Have you thought what you will do to earn money?” Lena May asked Gloria.

“Yes. Miss Lovejoy of the East Seventy-seventh Street Settlement has asked me to take charge of the girls’ clubs and I have accepted.”

“Gloria Vandergrift; you, a daughter of one of the very oldest families in this country, to work, actually work in those dreadful smelling slums.”

Gloria looked almost with pity at the speaker, who, of course, was Gwendolyn, as she said: “Do you realize that being born an aristocrat is merely an accident? You might have been born in the slums, Gwen, and if you had been, wouldn’t you be glad to have someone come to you and give you a chance?”

There being no reply, Gloria continued: “I take no credit to myself because I happened to be born in luxury and not in poverty, but we’ll have to postpone this conversation, for our neighbors are evidently coming to call.”

Bobs sprang to her feet and leaped to the open window. “Hello there, Phyl and Dick! Come around this way and I’ll open the porch door.”

Gwendolyn shrugged her shoulders. “Why doesn’t Roberta allow Peter to admit our visitors,” she began, but Gloria interrupted: “One excellent reason, perhaps, is that all our servants except the cook left this morning. You, of course, were still asleep and did not know of the exodus.”

The sharp retort on the tongue of Gwendolyn was not uttered, for Phyllis De Laney and her big, good-looking brother, Richard, were entering the library.

“You poor dear girls! Just as soon as I heard the news I came right over,” Phyllis De Laney exclaimed as she sank down in a deep, comfortable chair and looked about at her friends with an expression of frank curiosity on her doll-pretty face. “However, I told Ma Mere that I knew there wasn’t a word of truth in the scandalous gossip, and so I came to hear how it all started that I may be able to contradict it.” Phyllis took a breath and then continued her chatter: “Your maid, Gwen, told my Fanchon, and she said that every servant in your employ had been dismissed with two weeks’ advance pay; and she said a good deal more than that too, which, of course, isn’t true. Just listen to this and then tell me if it isn’t simply scandalous. That maid declared that you girls are going to work, actually work, to earn your own living.”

“I’ll say it’s true!” Roberta put in, grinning with wicked glee. Her good pal, Dick, smiled over at her as he remarked with evident amusement: “You don’t look very miserable about it, Bobs. In fact, quite the contrary, you appear pleased. If the truth were known, I envy you, honestly I do! I’d much rather go to work than go to college. I’m no good at Latin or Greek. If languages are dead, bury them, I say. I’m not a student by nature, so what’s the use pretending; but the pater won’t hear to it. Just because our grandfather left us each a million, we’ve got to dwaddle away our lives spending it. Of course I’m nineteen now, but you wait until I’m twenty-one years old and see what will happen.”

His sister Phyllis lifted her eyebrows ever so slightly and looked her disapproval. “In that time you will have changed your mind,” she remarked. Then turning to her particular friend, she added: “But, Gwen, you aren’t going to work, are you? Pray, what could you do?”

Gwendolyn was in no pleasant frame of mind as her sisters well knew, and her reply was most ungraciously given. Curtly she stated that she did not care to discuss her personal affairs with anyone.

Phyllis flushed and rose at once, saying coldly: “Indeed? Since when have you become so secretive? You always tell me everything you do and so I had no reason to suppose that you would object to my friendly inquiry; but you need have no fear, I shall never again intrude upon your privacy. I will bid you all good afternoon and good-bye, for, of course, since you are going to New York to work, I suppose as clerks in the shops, we will not likely meet again.”

“Aw, I say, Sis, cut it out! What’s the big idea, anyway? A friend is a friend, isn’t he, whether he wears broadcloth or overalls?” Then as his sister continued to sweep out of the room, the lad crossed to the oldest sister and held out his hand, saying, with sincere boyish sympathy, “Gloria, I’m mighty sorry about this—er—this—well, whatever it is, and please let me know where you go, and as soon as you’re settled I’ll run over and play the big brother act, if you’ll let me.”

Then, turning to Bobs, he said: “Go riding with me at sunrise tomorrow morning, will you, like we used to do before I went away to school. There’s a lot I want to say, and the day after I’m going to be packed off to the academy again to be tortured for another month; then, thanks be, vacation will let me out of that prison for a while.” Roberta hesitated, and Dick urged: “Go on, Bob! Be a sport. Say yes.”

“All right. I’ll be at the Twin Oaks, where we’ve met ever since we were little shavers.”

When the door closed behind the departing guests Gloria turned to the sister, who was but one year her junior, and said: “Gwendolyn, I am sorry to say this, but the good of the larger number requires it. If you cannot face the changed conditions cheerfully with us, I shall have to ask you to make your plans independent of us. We three have decided to be brave and courageous, and try to find joy and happiness in whatever may present itself, just as our mother and father would wish us to do, and just as they would have done had similar circumstances overtaken them.”

Gwendolyn rose and walked toward the door, but turned to say, “You need not concern yourselves about me in the least. I shall not go with you to New York. I shall visit my dear friend Eloise Rochester in Newport, as she has often begged me to do.”

“An excellent plan, if——” Gloria began, then paused.

Gwendolyn turned and inquired haughtily, “If what?”

“If Eloise wants you when she hears that you have neither home nor wealth. If I am anything of a character reader, I should say that the invitation about which you have just told was merely a bait, so to speak, for a return invitation. It is quite evident that Eloise has decided to marry Richard De Laney’s million-dollar inheritance, and since Phyllis will not invite her to their home you, as a next-door neighbor, can be used to advantage.”

“Indeed? Well, luckily Miss Vandergrift, you are not a character reader, as you will learn in the near future. You three make whatever plans you wish, but do not include me.” So saying, Gwendolyn left the room and a few moments later the three sisters heard her moving about in the apartment overhead, and they correctly assumed that she was packing, preparatory for her departure to Newport.

Gloria sighed: “I wonder why Gwen is so unlike our mother and father?” she said.

“I have it,” Bobs cried, whirling about with eyes laughingly aglow. “She’s a changeling! A discontented nurse girl wished to wreak vengeance upon Mother for having discharged her, or something like that, and so she stole the child who really was our sister and left this——”

“Don’t, Bobsie!” Lena May protested. “Even if Gwen is selfish, maybe we are to blame. She was ill for so long after Mother died that we couldn’t bear the thought of having two deaths, and so we rather spoiled her. I believe that if we meet her contrariness with love and are very patient we may find the gold that must be in her nature, since she is our mother’s child.”

“You can do it, if it’s do-able, Lena May,” Bobs declared. “Now, Gloria, break the glad news! When do we hit the trail for the big town?”

“I’m going in tomorrow to find a place for us to live. If you girls wish, you may accompany me.”

“Wish? Why, all the king’s oxen and all the king’s men couldn’t keep me from going.”

Gloria smiled at her hoidenish sister but refrained from commenting on her language. She was so thankful that there was only one Gwen in the family that she could overlook lesser failings. Bobs was taking the mishap that had befallen them as a great adventure, but even she did not dream of the truly exciting adventures that lay before them.

Soon after daybreak the next morning, down a deserted country road, two thoroughbred horses were galloping neck and neck.

“Gee along, Star,” Bobs was shouting. She had lost her hat a mile back and her short hair, which would ripple, though she tried hard to brush out the natural curls, was tossed about her head, making her look more hoidenish than ever.

Dick, on his slender brown horse, gradually won a lead and was a length ahead when they reached the Twin Oaks, which for many years had been their trysting place. Roberta and Dick had been playmates and then pals, squabbling and making up, ever since the pinafore days, more, however, like two boys than a boy and a girl. Bobs, in fact, never thought of herself as a young person who in due time would become a marriageable young lady, and so it was with rather a shock of surprise that she heard Dick say, when they had drawn their horses to a standstill in the shade of the wide-spreading trees: “I say, Roberta, couldn’t you cut out this going to work stuff and marry me?”

“Ye gods and little fishes! Me marry you?” Bobs’ remark and the accompanying expression in her round, sunburned face, with its pertly tilting freckled nose, were none too complimentary.

Dick flushed. “Well, I say! What’s the matter with me, anyhow? Anyone might think, by the way you’re staring, that I had said something dreadful. I’m not deformed, am I? And I’ve got money enough so you wouldn’t have to work ever and——”

Roberta became a girl at once, a girl with a sincere nature and a tender heart. Reaching out a strong brown hand, she placed it kindly on the arm of her friend. “Dicky, boy, forgive me, if—if I was a little astonished and showed it. Truth is, for so many years I’ve thought of you as the playmate I could always count on to fight my battles, that I’d sort of forgotten that we were grown up enough to even think of marrying. Of course we aren’t grown up enough yet to really marry, for you are only nineteen, and I’m worse than that, being not yet seventeen. And as for money, Dick, I’d like you heaps better if you were poor and working your way, but I know that you meant what you said most kindly. You wanted to save me from hard knocks, but, Dick, honest Injun, I revel in them. That is, I suppose I will. Never having had one as yet, I can’t speak from past experience.”

Then they rode slowly back to find the hat that had blown off into the bushes. Dick rescued it, and when he returned it he handed her a spray from a blossoming wild rose vine.

The lad did not again refer to his offer, and the girl, he noted with an inward sigh, had evidently forgotten all about it. She was gazing about her appreciatively. “Dicky boy,” she exclaimed, “there’s nothing much prettier than early morning in the country, is there, with the dew still sparkling—and a meadow lark singing,” she added, for at that moment a joyous song arose from a near-by thicket.

For a time they were silent as they rode slowly back by the way they had come. Then Dick said, “Bobs, since you love the country so dearly, aren’t you afraid you’ll be homesick in that human whirlpool, New York?”

The girl turned toward him brightly. “Perhaps, sometimes,” she replied. “But it isn’t far to the country when I feel the need of a deep breath of fresh air.” Then her face saddened as she continued: “Of course we won’t be coming out here any more.” She waved toward the vast estate which for many years had been the home of Vandergrifts. “We couldn’t stand it, not one of us could, to see strangers living where Mother and Father were so happy. They’ll probably change things a lot.” Then she added almost passionately: “I hope they will. Then, if ever I do see it again, it will not look like the same place.”

Dick did not say what was in his heart, but gloomily he realized that if the girl at his side did not expect ever to return to that neighborhood, it was quite evident that she would not be his wife, for his home adjoined that of the Vandergrifts.

When he spoke, his words in no way betrayed his thoughts. “Have you any idea, Bobs, what you’d like to do, over there in the big city; I mean to make a living?”

The girl laughed; then sent a merry side glance toward her companion. “You never could guess in a thousand years,” she flung at him, then challenged; “Try!”

The boy flicked his quirt at the drooping branches of a willow they were passing, then frankly confessed that he couldn’t picture Roberta in any of the occupations for women of which he had ever heard. Mischievously she queried, “Wouldn’t I make a nice demure saleswoman for ladies’ dresses or——”

“Great guns, No!” was the explosive interruption. “Don’t put such a strain on my imagination.” Then he laughed gaily, for he was evidently trying to picture the hoidenish girl mincing up and down in some fashionable emporium dressed in the latest styles, while women peered at her through lorgnettes. Bobs laughed with him when he told his thoughts, then said:

“I’ll agree, as a model, I won’t do.” Then with pretended thoughtfulness she flicked a fly from her horse’s ear. “Would I make a good actress, Dicky, do you think?”

“You’d make a better circus performer,” the boy told her. “I’ll never forget the antics we used to pull, before——”

“Before I realized that I was a girl and had to be ladylike.” Bobs laughed with him, then added merrily, “If it hadn’t been for my prunes and prisms, Sister Gwendolyn, I might never have ceased to be a tom-boy.”

“I hope you never will become like Gwen,” Dick said almost fiercely, “or like my sister Phyllis, either. They’re not our kind, though I’m sorry to say it.” Then noting a far-away, thoughtful expression which had crept into the girl’s eyes, the lad inquired: “Say, Bobs, have you any idea how Gwyn can earn a living? You’re the sort who can hold your own anywhere. You’d be willing to work, but Gwyn—well, I can’t picture her as a daily-bread earner.”

His companion shook her head; then quite unexpectedly she said: “Dick, why didn’t you fall in love with Gwen? It would have solved her problem to have had someone nice and rich to take care of her.”

“Well, of all the unheard of preposterous suggestions!” The amazed youth was so astonished that he unconsciously drew rein and stared at the girl. He knew by her merry laugh that she had said it but to tease, and so he rode on again at her side. Bobs feared that she had hurt her friend, for his face was still flushed and he did not speak. Reining her horse close to his, she again put a hand on his arm, saying with sincere earnestness: “Forgive me, pal of mine, if I seemed to speak lightly. Honestly, I didn’t mean it—that is, not as it sounded. But I do wish that someone as nice and—yes, I’ll say as rich as you are, would propose to poor Gwen. You don’t know how sorry Gloria and I feel because Gwen has to be poor with the rest of us.” The boy had placed his hand over the one resting on his arm, but only for a moment. “You see,” Bobs explained, “Glow and I honestly feel that an adventure of a new and interesting kind awaits us, and, as for little Lena May, money means nothing to her. If she can just be with Gloria, that is all she asks of Fate.”

They had reached the Vandergrift gate and Bobs, drawing rein, reached out her hand, saying: “Goodbye, Dick.” Then, after a hesitating moment, she added sincerely, “I’m sorry, old pal. I wish I could have said yes—that is, if it means a lot to you.”

The boy held her hand in a firm clasp as he replied earnestly, “I’m not going to give up hoping, Bobsie. I’ll put that question on the table for a couple of years, but, when I am twenty-one, I’m going to hit the trail for wherever you are, and ask it all over again. You see if I don’t.”

“You won’t if Eloise Rochester has anything to say about it,” was the girl’s merry rejoinder. Then as Bobs turned her horse toward the stables, she called over her shoulder: “O, I say, Dick, I forgot to tell you the profession I’ve chosen. I’m going to a girl detective.”

When Roberta entered the breakfast room, she found Gloria and Lena May there waiting for her. In answer to her question, the oldest sister replied that Gwen would not unlock her door. Lena May had left her breakfast on a tray in the hall. “We think she is packing to leave,” Gloria sighed. “The way Gwen takes our misfortune is the hardest thing about it.”

Bobs, who was ravenously hungry after her early morning ride, was eating her breakfast with a relish which contrasted noticeably with the evident lack of appetite shown by her sisters. At last she said: “Glow, I’m not so sure all this is really a misfortune. If something hadn’t happened to jolt us out of a rut, we would have settled down here and led a humdrum, monotonous life, going to teas and receptions, bridge parties and week-ends, played tennis and golf, married and died, and nothing real or vital would have happened. But, now, take it from me, I, for one, am going to really live, not stagnate or rust.”

Gloria smiled as she hastened to assure her sister: “I agree with you, Bobs. I’m glad something has happened to make it possible for me to carry out a long-cherished desire of mine. I haven’t said much about it, but ever since Kathryn De Laney came home last summer on a vacation and told me about the girls of the East Side who have never had a real chance to develop the best that is in them, I have wanted to help them. I didn’t know how to go about doing it, not until the crash came. Then I wrote Kathryn, and you know what happened next. She found a place for me in the Settlement House to conduct social clubs for those very girls of whom she had told me.”

Both of the listeners noted the eager, earnest expression on the truly beautiful face of the sister who had mothered them, but almost at once it had saddened, and they knew that again she was thinking of Gwen. Directly after breakfast Gloria went once more to the upper hall and tapped on a closed and locked door, but there was no response from within. However, the breakfast tray which Lena May had left on a near table was not in sight, and so, at least, Gwendolyn was not going hungry.

It seemed strange to the two younger girls to be clearing away the breakfast things and tidying up the kitchen where, for so many years, a good-natured Chinaman had reigned supreme.

“I’m going to miss Sing more than any servant that we ever had,” Bobs was saying when Gloria entered the kitchen. There was a serious expression on the face of the oldest girl and Bobs refrained from uttering the flippancy which had been on the tip of her tongue. Lena May, having put away the dishes, turned to ask solicitously: “Wouldn’t Gwen let you in, Glow?”

“No, I didn’t hear a sound, but the tray is gone.” The gentle Lena May was pleased to hear that.

“Poor Gwen, she is making it harder for herself and for all of us,” Gloria said; then added, “Are you girls ready to go with me? I’d like to get over to the city early, after the first rush is over and the midday rush has not begun.”

Exultant Bobs could not refrain from waving the dishcloth she still held. “Hurray for us!” she sang out. “Three adventurers starting on they know not what wild escapade. Wait until I change my togs, Glow, and I’ll be with you.” Then, glancing down at her riding habit, “Unless this will do?” she questioned her sister.

“Of course not, dear. We’ll all wear tailored suits.”

It was midmorning when three fashionably attired girls for the first time in their lives ascended to the Third Avenue Elevated, going uptown. At that hour there were few people traveling in that direction and they had a car almost to themselves. As they were whirled past tenements, so close that they could plainly see the shabby furniture in the flats beyond, the younger girls suddenly realized how great was the contrast between the life that was ahead of them and that which they were leaving. The thundering of the trains, the constant rumble of traffic below, the discordant cries of hucksters, reached them through the open windows. “It’s hard to believe that a meadow lark is singing anywhere in the world,” Bobs said, turning to Gloria. “Or that little children are playing in those meadows,” the older girl replied. She was watching the pale, ragged children hanging to railings around fire escapes on a level with the train windows.

“Poor little things!” Lena May’s tone was pitying, “I don’t see how they can do much playing in such cramped, crowded places.”

“I don’t suppose they even know the meaning of the word,” Bobs replied.

They left the train at the station nearest the Seventy-seventh Street Settlement. Since Gloria was to be employed there, she planned starting from that point to search for the nearest suitable dwelling. They found themselves in a motley crowd composed of foreign women and children, who jostled one another in an evident effort to reach the sidewalk where, in two-wheeled carts, venders of all kinds of things salable were calling their wares. “They must sell everything from fish to calico,” Bobs reported after a moment’s inspection from the curbing.

The women, who wore shawls of many colors over their heads and who carried market baskets and babies, were, some of them, Bohemians and others Hungarian. Few words of English were heard by the interested girls. “I see where I have to acquire a new tongue if I am to know what our future neighbors are talking about,” Bobs had just said, when, suddenly, just ahead of them, a thin, sickly woman slipped and would have fallen had not a laboring man who was passing caught her just in time. The grateful woman coughed, her hand pressed to her throat, before she could thank him. The girls saw that she had potatoes in a basket which seemed too heavy for her. The man was apparently asking where she lived; then he assisted her toward a near tenement.

“Well,” Bobs exclaimed, “there is evidently chivalry among working men as well as among idlers.”

At the crossing they were caught in a jam of traffic and pedestrians. Little Lena May clung to Gloria’s arm, looking about as though terrorized at this new and startling experience. When, after some moments’ delay, the opposite sidewalk was reached in safety, Bobs exclaimed gleefully: “Wasn’t that great?” But Lena May had not enjoyed the experience, and it was quite evident to the other two that it was going to be very hard for their sensitive, frail youngest sister to be transplanted from her gardens, where she had spent long, quiet, happy hours, painting the scenes she loved, to this maelstrom of foreign humanity. There was almost a pang of regret in the heart of the girl who had mothered the others when she realized fully, for the first time, what her own choice of a home location might mean to their youngest. Perhaps she had been selfish, because of her own great interest in Settlement Work, to plan to have them all live on the crowded East Side, but her fears were set at rest a moment later when they came upon a group of children, scarcely more than babies, who were playing in a gutter. Lena May’s sweet face brightened and, smiling up at Gloria, she exclaimed: “Aren’t they dears, in spite of the rags and dirt? I’d love to do something for them.”

“I’d like to put them all in a tub of soap-suds and give them a good scrubbing for once in their lives,” the practical Bobs remarked. Then she caught Gloria by the arm, exclaiming, as she nodded toward a crossing, “There goes that chivalrous laboring man. He steps off with too much agility to be a ditch-digger, or anyone who does hard work, doesn’t he, Glow?”

The oldest sister laughed. “Bobs,” she remarked, “I sometimes think that you are a detective by nature. You are always trying to discover by the cut of a man’s hair what his profession may be.”

Bobs’ hazel eyes were merry, though her face was serious. “You’ve hit it, Glow!” she exclaimed. “I was going to keep it a secret a while longer, but I might as well confess, now that the cat is out of the bag.”

“What cat?” Lena May had only heard half of this sentence; she had been so interested in watching the excitement among the children caused by the approach of an organ grinder.

“My chosen profession is the cat,” Bobs informed her, “and I suppose my brain, where it has been hiding, is the bag. I’m going to be a detective.”

Little Lena May was horrified. Detectives meant to her sleuths who visited underground haunts of crooks of all kinds. “I’m sure Gloria will not wish it, will you, Glow?”

Appealingly the soft brown eyes were lifted and met the smiling gaze of the oldest sister. “We are each to do the work for which we are best fitted,” she replied. “You are to be our little housekeeper and that will give you time to go on with your painting. I was just wondering a moment ago if you might not like to put some of these black-eyed Hungarian babies into a picture. If they are clean, they would be unusually beautiful.”

Lena May was interested at once and glanced about for possible subjects, and so for the time being the startling statement of Bobs’ chosen profession was dropped. They were nearing the East River, very close to which stood a large, plain brick building containing many windows. “I believe that is the Settlement House,” Gloria had just said, when Bobs, discovering the name over the door, verified the statement.

A pretty Hungarian girl of about their own age answered their ring and admitted them to a big cheerful clubroom. Another girl was practicing on a piano in a far corner. The three newcomers seated themselves near the door and looked about with great interest. Just beyond were shelves of books. Bobs sauntered over to look at the titles. “It’s a dandy collection for girls,” she reported as she again took her seat.

It was not long before Miss Lovejoy, the matron entered the room and advanced toward them. The three girls rose to greet her.

Miss Lovejoy smilingly held out a hand to the tallest, saying in her pleasant, friendly voice, “I wonder if I am right in believing that you are the Miss Gloria Vandergrift who is coming to assist me.”

“Yes, Miss Lovejoy, I am, and these are my younger sisters, Roberta and little Lena May.” Then she explained: “We haven’t moved into town as yet. I thought best to come over this morning and find a place for us to live; then we will have our trunks sent and our personal possessions.”

“That is a good idea,” the matron said, then asked: “Have you found anything as yet?”

“We thought, since we are strangers in the neighborhood, that you might be able to suggest some place for us,” Gloria told the matron.

After a thoughtful moment Miss Lovejoy replied: “The tenement houses in this immediate neighborhood are most certainly not desirable for one used to comforts. However, on Seventy-eighth Street, there is a new model tenement built by some wealthy women and it is just possible that there may be a vacant flat. You might inquire at the office there. You can take the short-cut path across the playground and it will lead you directly to the model tenement.”

“Thank you, Miss Lovejoy,” Gloria said. “We will let you know the result of our search.”

The model tenement which Miss Lovejoy had pointed out to them was soon reached. A door on the ground floor was labeled “Office,” and so Gloria pushed the electric button.

A trim young woman whose long-lashed, dark eyes suggested her nationality, received them, but regretted to have to tell them that every flat in the model tenement was occupied. She looked, with but slightly concealed curiosity, at these three applicants who, as was quite evident, were from other environments.

Gloria glanced about the neat courtyard and up at windows where flowers were blossoming in bright window boxes, then glowingly she turned back to the girl: “It was a splendid thing for those wealthy society women to do, wasn’t it,” she said, “erecting this really handsome yellow brick building in the midst of so much poverty and squalor. It must have a most uplifting effect on the lives of the poor people to be able to live here where everything is so sweet and clean, rather than there,” nodding, as she spoke, at a building across the street which looked gloomy, crumbling, unsafe and unsanitary.

The office attendant spoke with enthusiasm. “No one knows better than I, for I used to live in the other kind of tenement when I was a child, but Miss Lovejoy’s club for factory girls gave me my chance to learn bookkeeping, and now I am agent here. My name is Miss Selenski. Would you like to see the model apartment?”

“Thank you. Indeed we would,” Gloria replied with enthusiasm; then she added, “Miss Selenski, I am Miss Vandergrift, and these are my sisters, Roberta and Lena May. We hope to be your neighbors soon.”

If there was a natural curiosity in the heart of the dark-eyed girl, she said nothing of it, and at once led the way through the neatly tiled halls and soon opened a door admitting them to a small flat of three rooms, which was clean and attractively furnished. The windows, flooded with sunlight, overlooked the East River.

“This is the apartment that we show,” Miss Selenski explained. “The others are just like it, or were, before tenants moved in,” she corrected.

“Say, this is sure cosy! Who lives in this one?” Bobs inquired.

“I do,” Miss Selenski replied, hurrying to add, “But I did not fit it up. The ladies did that. It has all the modern appliances that help to make housekeeping easy, and once every week a teacher comes here to instruct the neighborhood women how to cook, clean and sew; in fact, how to live. And the lessons and demonstrations are given in this apartment.”

When the girls were again in the office, Gloria turned to their new acquaintance, saying, “Do you happen to know of any place around here that is vacant where we might like to live?”

At first Miss Selenski shook her head. Then she added, with a queer little smile, “Not unless you’re willing to live in the old Pensinger mansion.”

Then she went on to explain: “Long, long ago, when New York was little more than a village, and Seventy-eighth Street was country, all along the East River there were, here and there, handsome mansion-like homes and vast grounds. Oh, so different from what it is now! Every once in a while you find one of these old dwellings still standing.

“Some of them house many poor families, but the Pensinger mansion is seldom occupied. If a family is brave enough to move in, before many weeks the ‘for rent’ sign is again at the door. The rent is almost nothing, but—” the girl hesitated, then went on to say, “Maybe I ought not to tell you the story about the old place if you have any thought of living there.”

“Oh, please tell it! Is it a ghost story?” Bobs begged, and Gloria added, “Yes, do tell it, Miss Selenski. We are none of us afraid of ghosts.”

“Of course you aren’t,” Miss Selenski agreed, “and, for that matter, neither am I. But nearly all of our neighbors are superstitious. Mr. Tenowitz, the grocer at the corner of First and Seventy-ninth has the renting of the place, and he declares that the last tenant rushed into his store early one morning, paid his bill and departed without a word of explanation, but he looked, Mr. Tenowitz told me, as though he had seen a ghost. I don’t think there is anything the matter with the old house,” their informant continued, “except just loneliness.

“Of course, big, barnlike rooms, when they are empty, echo every sound in a mournful manner without supernatural aid.”

“But how did it all start?” Bobs inquired. “Did anything of an unusual nature ever happen there?”

Miss Selenski nodded, and then continued: “The story is that the only daughter of the last of the Pensingers who lived there disappeared one night and was never again seen. Her mother, so the tale goes, wished her to marry an elderly English nobleman, but she loved a poor Hungarian violinist whom she was forbidden to see. Because of her grief, she did many strange things, and one of them was to walk at midnight, dressed all in white, along the brink of the dark swirling river which edged the wide lawn in front of her home. Her white silk shawl was found on the bank one morning and the lovely Marilyn Pensinger was never seen again.

“Her father, however, was convinced that his daughter was not drowned, but that she had married the man she loved and returned with him to his native land, Hungary. So great was his faith in his own theory that, in his will, he stated that the taxes on the old Pensinger mansion should be paid for one hundred years and that it should become the property of any descendant of his daughter, Marilyn, who could be found within that time.

“I believe that will was made about seventy-five years ago and so, you see, there are twenty-five years remaining for an heir to turn up.”

“What will happen if no one claims the old place?” Gloria inquired.

“It is to be sold and the money devoted to charity,” Miss Selenski told them.

“That certainly is an interesting yarn,” Bobs declared; then added gleefully, “I suppose the people around here think that the fair Marilyn returns at midnight, prowling along the shores of the river looking for her white silk shawl.”

Miss Selenski nodded. “That’s about it, I believe.” Then she added brightly, “I’ll tell you what, I’m not busy at this hour and if you wish I’ll take you over to see the old place. Mr. Tenowitz will give me the keys.”

“Thank you, Miss Selenski,” Gloria said. “We would be glad to have you show us the place. There seems to be nothing else around here to rent and we might remain in the Pensinger mansion until you have a model flat unoccupied.”

“That will not be soon,” they were told, “as there is a long waiting list.”

Then, after hanging a sign on the door which stated that she would be gone for half an hour, Miss Selenski and the three interested young people went down Seventy-eighth Street and toward the East River.

Bobs was hilariously excited. Perhaps, after all, she was going to have an opportunity to really practice what she had, half in fun, called her chosen profession, for was there not a mystery to be solved and an heir to be found?

Lena May’s clasp on the hand of her older sister grew unconsciously tighter as they passed a noisy tobacco factory which faced the East River and loomed, smoke-blackened and huge.

The old Pensinger mansion was just beyond, set far back on what had once been a beautiful lawn, reaching to the river’s edge, but which was now hard ground with here and there a half-dead tree struggling to live without care. A wide road now separated it from the river, which was lined as far up and down as one could see with wharves, to which coal and lumber barges were tied.

The house did indeed look as though it were a century old. The windows had never been boarded up, and many of the panes had been broken by stones thrown by the most daring of the street urchins, though, luckily, few dared go near enough to further molest the place for fear of stirring up the “haunt.”

“A noble house gone to decay,” Gloria said. She had to speak louder than usual because of the pounding and whirring of the machinery in the neighboring factory. Lena May wondered if anywhere in all the world there were still peaceful spaces where birds sang, or where the only sound was the murmuring of the wind in the trees.

“Is it never still here?” she turned big inquiring eyes toward their guide.

“Never,” Miss Selenski told her. “That is, not for more than a minute at a time, between shifts, for when the day work stops the night work begins.”

“Many of the workers are women, are they not?” Gloria was looking at the windows of the factory where many foreign women could be seen standing at long tables.

“They leave their children at the Settlement House. They work on the day shift, and the men, if they can be made to work at all, go on at night.”

“Oh, Gloria!” this appealingly from the youngest, “will we ever be able to sleep in the midst of such noise, when we have been used to such silent nights at home?”

“I don’t much wonder that you ask,” Bobs laughingly exclaimed, as she thrust her fingers in her ears, for at that moment a tug on the river, not a stone’s throw away from them, rent the air with a shrill blast of its whistle, which was repeated time and again.

“You won’t mind the noises when you get used to them,” Miss Selenski told them cheerfully. “I lived on Seventy-sixth Street, right under the Third Avenue L, and the only time I woke up was when the trains stopped running. The sudden stillness startles one, I suppose.”

Lena May said nothing, but she was remembering what Bobs had said when they had left the Third Avenue Elevated: “Now we are to see how the ‘other half’ lives.”

“Poor other half!” the young girl thought. “I ought to be willing to live here for a time and bring a little of the brightness I have known into their lives, for they must be very drab.”

“Just wait here a minute,” Miss Selenski was saying, “and I’ll run over to the grocery and get the key.”

She was back in an incredibly short time and found the three girls examining with great interest the heavy front door, which had wide panels, a shapely fan light over them, with beautiful emerald glass panes on each side.

“I simply adore this knocker,” Bobs declared, jubilantly. “Hark, let’s hear the echoes.”

The knocker was lifted and dropped again, but though they all listened intently, a sudden confusion on the river made it impossible to hear aught else.

“My private opinion is that Marilyn’s ghost would much prefer some other spot for midnight prowls,” Bobs remarked, as the old key was being fitted into the queerly designed lock. “Imagine a beautiful, sensitive girl of seventy-five years ago trying to prowl down there where barges are tied to soot-black docks and where derricks are emptying coal into waiting trucks. No really romantic ghost, such as I am sure Marilyn Pensinger must be, would care to prowl around here.”

Miss Selenski smiled at Bobs’ nonsense. “I’m glad you feel that way,” she said, “for, of course, if you don’t believe in the ghost, you won’t mind renting the house.”

At that moment the derrick of which Bobs had spoken emptied a great bucket of coal with a deafening roar, and a wind blowing from the river sent the cloud of black dust hurling toward them.

“Quick! Duck inside!” Bobs cautioned, as they all leaped within and closed the door with a bang.

“Jimminy-crickets!” she then ejaculated, using her favorite tom-boy expression. “The man who has this place to rent can’t advertise it as clean and quiet, a good place for nervous people to recuperate.” Then with a wry face toward her older sister. “I can’t imagine Gwen in this house, can you?”

There was a sudden troubled expression in Gloria’s eyes. “No, dear, I can’t. And I’m wondering, in fact I have often been wondering this morning, if we ought not to select some place where Gwen and little Lena May would be happier, for, of course, Gwen can’t keep on visiting her friends forever. She will have to come home some day.” The speaker felt a hand slip into hers and, glancing down, she saw a pleading in the uplifted eyes of their youngest. “I’d like to live here, Glow, for a while, if you would.”

“Little self-sacrificing puss that you are.” Gloria smiled at Miss Selenski, then said: “May we look over the old house and decide if we wish to take it? Time is passing and we have much packing to do if we are to return in another day or two.”

Although she did not say so, Bobs and Lena May knew that their mothering sister was eager to return to their Long Island home that she might see Gwendolyn before her departure.

The old colonial mansion, like many others of its kind, had a wide hall extending from the front to the back. At the extreme rear was a fireplace with built-in seats. In fact, to the great delight of Bobs, who quite adored them, a fireplace was found in each of the big barren rooms. Four of these were on that floor, with the old kitchen in the basement, and four vast silent rooms above, that had been bed chambers in the long ago. Too, there was an attic, which they did not visit.

When they had returned to the front hall, Bobs exclaimed: “We might rent just one floor of this mansion and then have room to spare.”

But the oldest sister looked dubious. “I hardly think it advisable to attempt to live in this place—” she began. “There is enough room here to home an orphanage, and the kiddies wouldn’t be crowded, either.”

Roberta was plainly disappointed. “Oh, I say, Glow, haven’t you always told us younger girls not to make hasty conclusions, and here you have hardly more than crossed the threshold and you have decided that we couldn’t make the old house livable. Now, I think this room could be made real cozy.”

How the others laughed. “Bobs, what a word to apply to this old high-ceiled salon with its huge chandeliers and——”

“Say, girls,” the irrepressible interrupted, “wouldn’t you like to see all of those crystals sparkle when the room is lighted?” Then she confessed, “Perhaps cozy isn’t exactly the right word, but nevertheless I like the place, and now, with the door closed, it isn’t so noisy either. It’s keen, take it from me.”

“Roberta,” Gloria sighed, “now and then I congratulate myself that you have actually reformed in your manner of speech, when——”

“Say, Glow, I’ll make a bargain,” Bobs again interrupted. “I’ll talk like the daughter of Old-dry-as-dust-Johnson, if you’ll take this place. Now, my idea is that we can just furnish up this lower floor. Make one of the back rooms into a kitchen and dining-room, put in gas and electricity, and presto change, there you are living in a modern up-to-date apartment. Then we could lock up the basement and the rooms upstairs and forget they are there.”

“If you are permitted to forget,” Miss Selenski added, with her pleasant smile. Then, for the first time, the girls remembered that the old house was supposed to be supernaturally occupied.

It was Bobs who exclaimed: “Well, if that poor girl, Marilyn Pensinger, wants to come back here now and then and prowl about her very own ancestral mansion, I, for one, think we would be greatly lacking in hospitality if we didn’t make her welcome.”

Then pleadingly to her older sister: “Glow, be a sport! Take it for a month and give it a try-out.”

Lena May’s big brown eyes wonderingly watched this enthusiastic sister, who was but one year her senior, but whose tastes were widely different. Her gentle heart was already desperately homesick for the old place on Long Island, for the gardens that were a riot of flowers from spring until late fall.

Gloria walked to one of the windows and looked out meditatively. “If this is the only place in the neighborhood in which we can live,” she was thinking, “perhaps we would better take it, and, after all, Bobs may be right: this one floor can be made real homelike with the furniture that we will bring, and what we do not need can be stored in the rooms overhead.”

Bobs was eagerly awaiting her older sister’s decision, and when it was given, that hoidenish girl leaped about the room, staging a sort of wild Indian dance that must have amazed the two chandeliers which had in the long ago looked down upon dignified young ladies who solemnly danced the minuet, and yet, perhaps the lonely old house was glad and proud to think that it had been chosen as a residence for three girls, and that once again its walls would reverberate with laughter and song.

“We must start for home at once,” Gloria said. Then, to Miss Selenski, “We will stop on our way to the elevated and tell Mr. Tenowitz that we will take the place for a time; and thank you so much for having helped us find something. We shall want you to come often to see us.”

Bobs was the last one to leave, and before she closed the heavy old-fashioned door, she peered back into the musty dimness and called, “Good-bye, old house, we’re going to have jolly good times, all of us together.”

Two weeks later many changes had taken place. Mr. Tenowitz had agreed to have one of the two large back rooms transformed into a modern kitchen at one end, and the other end arranged so that it might be used as a dining-room. In that room the early morning sun found its way, and when Lena May had filled the windows with boxes containing the flowering plants brought from the home gardens, it assumed a cheerfulness that delighted the heart of the little housekeeper.

Too, the huge chandeliers in the salon had been wired with electricity, and great was the joy in the heart of Bobs on the night when they were first lighted. The rich furnishings from their own drawing-room were in place and the effect was far more homelike than Gloria had supposed possible.

The two large rooms on the other side of the wide dividing hall had been fitted up as bed chambers and the furniture that they did not need had been stored in the large room over the kitchen.

How Lena May had dreaded that first night they had spent in the old house, not because she believed it to be haunted. Gloria had convinced her that that could not possibly be so, but because of the unusual noises, she knew that she would not be able to sleep a wink. Nor was she, for each time that she fell into a light slumber, a shriek from some passing tug awakened her, and a dozen times at least she seized her roommate, exclaiming, “Glow, what was that?” Sometimes it was a band of hoodlums passing, or again an early milk wagon, or some of the many noises which accompanied the night activities of the factory that was their next-door neighbor.

It was a very pale, sleepy-eyed Lena May who set about getting breakfast the next morning, with Gloria helping, but Bobs looked as refreshed as though she had spent the night in her own room on Long Island, where the whippoorwill was the only disturber of the peace.

“You’ll get used to it soon,” that beaming maiden told Lena May, and then, when the youngest girl had gone with a small watering pot to attend to the needs of her flower gardens at the front of the house, Bobs added softly: “Glow, how have you planned things? It never would do to leave Lena May all alone in the house, would it? And yet you and I must go out and earn our daily bread.”

“I shall take Lena May with me wherever I go; that is, I will at first, until we have things adjusted,” the older sister replied. Then she inquired: “What do you intend to do, Bobsie, or is it a secret as yet?”

“It sure is,” was the laughing reply, “a secret from myself, as well as from everyone else, but I’m going to start out all alone into the great city of New York this morning and give it the once over.”

“Roberta Vandergrift, didn’t you promise me that you would talk like a Johnsonian if we would rent this house?” Gloria reprimanded.

The irrepressible younger girl’s eyes twinkled. “My revered sister,” she said, solemnly, “my plans for the day are as yet veiled in mystery, but, with your kind permission, I will endeavor to discover in this vast metropolis some refined occupation, the doing of which will prove sufficiently remunerative to enable me to at least assist in the recuperation of our fallen fortunes.” Then rising and making a deep bow, her right hand on her heart, that mischievous girl inquired: “Miss Vandergrift, shall I continue conversing in that way during our sojourn in this ancient mansion, or shall I be—just natural?”

Lena May, who had returned, joined in the laughter, and begged, “Do be natural, Bobs, please, but not too natural.”

“Thank you, mademoiselles, for your kind permission, and now I believe I will don my outdoor apparel and go in search of a profession.”

Gloria looked anxiously at the young girl before her, who was of such a splendid athletic physique, whose cheeks were ruddy with health, and whose eyes were glowing with enthusiasm. Ought she to permit Bobs to go alone into the great surging mass of humanity so unprotected?

“Roberta,” she began, “do not be too trusting, dear. Remember that the city is full of dangers that lurk in out-of-the-way places.”

The younger girl put both hands on the shoulders of the oldest sister and, looking steadily into her eyes, she said seriously: “Glow, dear, you have taught us that the greatest thing a parent can do for her daughter is to teach her to be self-reliant that she may stand alone as, sooner or later, she will have to do. I shall be careful, as I do not wish to cause my sisters needless worry or anxiety, but I must begin to live my own life. You really wish me to do this, do you not, Gloria?”

“Yes, dear,” was the reply, “and I am sure the love of our mother will guide and guard you. Good-bye and good luck.”

When Bobs was gone, Lena May slipped up to the older sister, who had remained seated, and, putting a loving arm over the strong shoulders, she said tenderly: “Glow, there are tears in your eyes. Why? Do you mind Bobs’ going alone out into the world?”

“I was thinking of Mother, dear, and wishing I could better take her place to you younger girls, and too, I am worried, just a little, because Gwendolyn does not write. It was a great sorrow to me, Pet, to find that she had left without saying good-bye, and I can’t help but fear that I was hasty when I told her that she must plan her life apart from us if she could not be more harmonious.”

Then, rising, she added: “Ah, well, things will surely turn out for the best, little girl. Come now, let us do our bit of tidying and then go over to the Settlement House and find out what my hours are to be.”

But all that day, try as she might to be cheerful, the mothering heart of Gloria was filled with anxiety concerning her two charges. Would all be well with the venturous Bobs, and why didn’t Gwen write?

There was no anxiety in the heart of Roberta. In her short walking suit of blue tweed, with a jaunty hat atop of her waving brown hair, she was walking a brisk pace down Third Avenue. Even at that early hour foreign women with shawls over their heads and baskets on their arms were going to market. It was a new experience to Roberta to be elbowed aside as though she were not a descendant of a long line of aristocratic Vandergrifts. The fact that she was among them, made her one of them, was probably their reasoning, if, indeed, they noticed her at all, which she doubted. Gwen would have drawn her skirts close, fearing contamination, but not so Bobs. She reveled in the new experience, feeling almost as though she were abroad in Bohemia, Hungary or even Italy, for the dominant nationality of the crowd changed noticeably before she had gone many blocks. How wonderfully beautiful were some of the young Italian matrons, Bobs thought; their dark eyes shaded with long lashes, their natural grace but little concealed by bright-colored shawls.

At one corner where the traffic held her up, the girl turned and looked at the store nearest, her attention being attracted by a spray of lilacs that stood within among piles of dusty old books. It seemed strange to see that fragrant bit of springtime in a gloomy second-hand shop so far from the country where it might have blossomed. As Bobs gazed into the shop, she was suddenly conscious of a movement within, and then, out of the shadows, she saw forms emerging. An old man with a long flowing beard and the tight black skull cap so often worn by elderly men of the East Side was pushing a wheeled chair in which reclined a frail old woman, evidently his wife. In her face there was an expression of suffering patiently borne which touched the heart of the young girl.

The chair was placed close to the window that the invalid might look out at the street if she wished and watch the panorama passing by.

Instantly Bobs knew the meaning of the lilac, or thought that she did, and, also, she at once decided that she wished to purchase a book, and she groped about in her memory trying to recall a title for which she might inquire. A detective story, of course, that was what she wanted. Since it was to be her chosen profession, she could not read too many of them.

The old man had disappeared by this time, but when Bobs entered the dingy shop the woman smiled up at her, and, to Roberta’s surprise, she heard herself saying, “Oh, may I have just one little sniff of your lilac? I adore them, don’t you?”

The woman in the chair nodded, and her reply was in broken English, which charmed her listener. She said that her “good man” bought her a “blossom by the flower shop” every day, though she did tell him he shouldn’t, she knowing that to do it he had to go without himself, but it’s the only “bit of brightness he can be giving me,” my good man says.

Then she was silent, for from a little dark room at the back of the shop the old man, bent with years, shuffled forward. Looking at him, Roberta knew at once why he bought flowers and went without to do it, for there was infinite tenderness in the eyes that turned first of all to the occupant of the wheeled chair.

Then he inquired what the customer might wish. Roberta knew that she had a very small sum in her pocket and that as yet she had not obtained work, but buy something she surely must, so she asked for detective stories.

The old man led her to a musty, dusty shelf and there she selected several titles, paid the small sum asked and inquired if he would keep the parcel for her until she returned later in the day.

Then, with another bright word to the little old woman, the girl was gone, looking back at the corner to smile and nod, and the last thing that she saw was the spray of lilacs that symbolized unselfish love.

With no definite destination in mind, Roberta crossed Third Avenue and walked as briskly as the throngs would permit in the direction of Fourth. In a mood, half amused, half serious, she began to soliloquize: “Now, Miss Roberta Vandergrift, it is high time that you were attempting to obtain employment in this great city. Suppose you go over to Fifth Avenue and apply for a position as sales girl in one of the fine stores where you used to spend money so lavishly?”

But, when the Fourth Avenue corner was reached, Roberta stopped in the middle of the street heedless of the seething traffic and stared at an upper window where she saw a sign that fascinated her:

BURNS FOURTH AVENUE BRANCH

DETECTIVE AGENCY

The building was old and dingy, the stairway rickety and dark, but Roberta in the spirit of adventure climbed to the second floor without a thought of fear. A moment later she was obeying a message printed on a card that hung on the first door in the unlighted hall which bade her enter and be seated.

This she did and admitted herself into a small waiting room beyond which were the private offices, as the black letters on the frosted glass of a swinging door informed her. Roberta sat down feeling unreal, as though she were living in a story book. She could hear voices beyond the door; one was quiet and calm, the other high pitched and excited.

The latter was saying: “I tell you I don’t want no regular detective that any crook could get wise to, I want someone so sort of stupid-looking that a thief would think she wouldn’t get on to it if he lifted something right before her eyes.”

It was harder for Roberta to hear the reply. However she believed that it was: “But, Mr. Queerwitz, we only have one woman in our employ just now, and she is engaged out of town. I——”

The speaker paused and looked up, for surely the door to his private office had opened just a bit. Nor was he mistaken, for Bobs, as usual, acting upon an impulse, stood there and was saying: “Pardon me for overhearing your conversation. I just couldn’t help it. I came to apply for a position and I wondered if I would do.” There was a twinkle in her eyes as she added: “I can look real stupid if need be.”

The good-looking young man in the neat grey tweed, arose, and his expression was one of appreciative good humor.

“This is not exactly according to Hoyle,” he remarked in his pleasant voice, “but perhaps under the circumstances it is excusable. May I know your name and former occupation?”

Roberta did a bit of quick mental gymnastics. She did not wish to give her real name. A Vandergrift in a Fourth Avenue detective agency! Even Gloria might not approve of that. Almost instantly and in a voice that carried conviction, at least to the older man, the girl said: “Dora Dolittle.”

Were the gray-blue eyes of the younger man laughing? The girl could not tell, for his face was serious and he continued in a more business-like manner: “Miss Dolittle, I am James Jewett. May I introduce Mr. Queerwitz, who has a very fine shop on Fifth Avenue, where he sells antiques of great value? Although he has lost nothing as yet, he reports that neighboring shops have been visited, presumably by a woman, who departs with something of value, and he wishes to be prepared by having in his employ a clerk whose business it shall be to discover the possible thief. Are you willing to undertake this bit of detective work? If, at the end of one week you have proved your ability in this line, I will take you on our staff, as we are often in need of a wide-awake young lady.”

It was difficult for Roberta not to shout for joy.

“Thank you, Mr. Jewett,” she replied as demurely as a gladly pounding heart would permit. “Shall I go with Mr. Queerwitz now?”

“Yes, and report to me each morning at eight o’clock.”

The two departed, although it was quite evident that the merchant was not entirely pleased with the arrangement.

“Mr. Queerwitz! What a name!” Bobs was soliloquizing as she sat on the back seat of the big, comfortable limousine, and now and then glanced at her preoccupied companion. He was very rich, she decided, but not refined, and yet how strange that a man with unrefined tastes should wish to sell rarely beautiful things and antiques. Mr. Queerwitz was not communicative. In fact, he had tried to protest at the suddenly made arrangement and had declared to Mr. Jewett, in a brief moment when they were alone, that he shouldn’t pay a cent of salary to that “upstart of a girl” unless she did something to really earn it. Mr. Jewett had agreed, saying that he would assume the responsibility; but of this Roberta knew nothing.

They were soon riding down Fifth Avenue in the throng of fine equipages with which she was most familiar, as often the handsome Vandergrift car had been one of the procession.

Bobs felt that she would have to pinch herself as she followed her portly employer into an exclusive art shop to be sure that she was that same Roberta Vandergrift. Then she reminded herself that she must entirely forget her own name if she were to be consistently Dora Dolittle.

How Bobs hoped that she would be successful on this, her first case, that she might be permanently engaged by that interesting looking young man who called himself James Jewett.

At that early hour there were no customers in the shop, but Roberta saw three young women of widely varying ages who were dusting and putting things in order for the business of the day. Mr. Queerwitz went at once to a tall, spare woman of about fifty whose light, reddish hair suggested that the color had been applied from without.

“Miss Peerwinkle,” he said rather abruptly, “here’s the new clerk I was telling you about. You’d better show her the lay of things before it gets busy.”

Miss Peerwinkle turned, and her washed-out blue eyes seemed to look down at Roberta from the great height where, at least, she believed that her position as head saleslady at the Queerwitz antique shop had placed her.

“Your name, Miss?” she inquired when the proprietor had departed toward a rear door labeled “No admittance.”

Bobs had been so amused by all that she had seen that she hardly heard the inquiry, and when at last she did become conscious of it, for one wild moment she couldn’t recall her new name, and so she actually hesitated. Luckily just then one of the girls called to Miss Peerwinkle to ask her about a tag, and in that brief moment Bobs remembered.

When the haughty “head lady” turned her coldly inquiring eyes again toward the new clerk, Roberta was able to calmly reply, “Dora Dolittle.”

Miss Peerwinkle sniffed. Perhaps she was thinking it a poor name for an efficient clerk to possess. Bobs’ sense of humor almost made her exclaim: “I ought to have chosen Dora Domuch.” Then she laughingly assured herself that that wouldn’t have done at all, as she did not believe that there was such a name and surely she had heard of Dolittle.

Bobs’ soliloquy was broken in upon by a strident voice calling: “Miss Dolittle, you’re not paying any attention to what I am saying. Right here and now, let me tell you day-dreaming isn’t permitted in this shop. I was telling you to go with Nell Wiggin to the cloakroom, and don’t be gone more’n five minutes. Mr. Queerwitz don’t pay salaries for prinking.”

Bobs was desperately afraid that she wouldn’t be able to get through the morning without laughing, and yet there was something tragic about the haughtiness of this poor Miss Peerwinkle.

Meekly she followed a thin, pale girl of perhaps twenty-three. The two who were left in the shop at once began to express their indignation because a new clerk had been brought in for them to train.

“If ever anybody looked the greenhorn, it’s her,” Miss Peerwinkle exclaimed disdainfully, and Miss Harriet Dingley agreed.

They said no more, for the new clerk, returning, said, “What am I to do first?” Unfortunately Roberta asked this of the one nearest, who happened to be Miss Harriet Dingley. That woman actually looked frightened as she said, nodding toward her companion, “Don’t ask me. I’m not head lady. She is.”

Again Bobs found it hard not to laugh, for Miss Peerwinkle perceptibly stiffened and her manner seemed to say, “You evidently aren’t used to class if you can’t tell which folks are head and which aren’t.” But what she really said was: “Nell Wiggin will show you around, and do be careful you don’t knock anything over. If you do, your salary’s docked.”

“I’ll be very careful, Miss Peerwinkle,” the new clerk said, but she was thinking, “Docked! My salary docked. I know what it is to dock a coal barge, for I have one in front of my home, but——”

“Oh, Miss Dolittle, please do watch where you go. You almost ran into that Venetian vase.” There was real kindness and concern in the voice of the pale, very weary-looking young girl at her side, and in that moment Bobs knew that she was going to like her. “Poor little thing,” Bobs thought. “She looks as though some unkind Fate had put out the light that ought to be shining in her heart. I wish that I might find a way to rekindle it.”

Very patiently Miss Nell Wiggin explained the different departments in the antique shop. Suddenly she began to cough and sent a frightened glance toward the closed door that bore the sign “No Admittance,” then stifled the sound in her handkerchief. Nothing was said, but Roberta understood.

The old furniture greatly interested Bobs. In her own home there were many beautiful antiques. Casually she inquired, “How does Mr. Queerwitz manage to obtain so much rare old furniture?”

To her surprise, Nell Wiggin looked quickly around to be sure that no one was near, then she said: “I’d ought not to tell you, but I will if you’ll keep it dark.”

“Dark as the deepest dungeon,” Roberta replied, much puzzled by her comrade’s mysterious manner. The slight girl drew close. “He makes it behind that door that nobody’s allowed to go through,” she said in a low voice; then added, evidently wishing to be fair, “but that’s nothing unusual. Lots of dealers make their antiques and the public goes on buying them knowing they may not be as old as the tags say. Here, now, are the old books, and at least they are honest.”

Bobs uttered a cry of joy. “Oh, how I do wish I could have charge of this department,” she said. “I adore old books.”

There was a light in the pale face of little Miss Wiggin. “I do, too,” she said. “That is, I love Dickens; I never read much else.” Then, almost wistfully, she added: “I didn’t have much chance to go to school, but once, where I went to live, I found an old set of Dickens’ books that someone had left, and I’ve just read them over and over. I never go out nights and the people living in those books are such a lot of company for me.”

Again Bobs felt a yearning tenderness for this frail girl, who was saying, “They’re all the friends I’ve ever had, I guess.”

Impulsively the new clerk exclaimed, “I’ll be your friend, if you’ll let me.” Just then a strident voice called, “Miss Wiggin, forward!”

“You stay with the books,” Nell said softly, “and I’ll do the china.”

Bobs watched the slight figure that was hurrying toward the front, and she sighed, with tears close to the hazel eyes, and in her heart was a prayer, “May I be forgiven for the selfish, heedless years I have lived. But perhaps now I can make up for it. Surely I shall try.”

Roberta had been told by Mr. Jewett that she must not reveal to anyone her real reason for being at the antique shop, and, as Mr. Queerwitz had no faith in the girl’s ability to waylay a pilferer, he did not care to have Miss Nell Wiggin devote more time to teaching her the business of selling antiques. This information was conveyed by Miss Peerwinkle to Nell, who was told to stay away from the new clerk, with the added remark: “If she didn’t get on to the ropes with one hour’s showing, she’s too stupid for this business, anyhow.”

Why the head lady had taken such a very evident dislike to her, Bobs could not understand, for surely she was willing to do whatever she was told. Ah, well, she wasn’t going to worry. “Worrying is what makes one old,” she thought, as she mounted a small step-ladder on casters that one could push along the shelves. From the top of it she examined the books that were highest. Suddenly she uttered an exclamation of delight, then looked about quickly to be sure that she had not been heard. Customers in the front part of the store occupied the attention of the three clerks, so Roberta reached for a volume that had attracted her attention. It was indeed rare and old, so very old that she wondered that the covers did not crumble, and it had illumined letters. “Perhaps they were made by early monks,” Bobs was thinking. She sat down on the ladder and began turning the fascinating pages that were yellow with age. Suddenly she was conscious that someone stood near her. She looked up to find the accusing gaze of the head clerk fixed upon her.

Bobs was startled into exclaiming: “Say, Miss Peerwinkle, a cat has nothing on you when it comes to walking softly, has it?”

The reply was frigidly given: “Miss Do-little,” with emphasis, “you are supposed to dust the books, not read them; and what’s more, that particular book is the rarest one in the whole collection. There’s a mate to it somewhere, and when Mr. Queerwitz finds it, he can sell the two of them to Mr. Leonel Van Loon for one thousand dollars in cool cash.”

Roberta was properly impressed, and replaced the book; then, taking a duster, she proceeded to tidy her department.

At eleven o’clock Bobs wondered if she ought to wander about the shop and watch the occasional customer. This she did, and was soon in the neighborhood of Miss Wiggin. “You’re to go out to eat when I do,” Nell told her.

“I’m glad to hear it,” was the reply.

Promptly at noon Miss Wiggin beckoned and said: “Come, Miss Dolittle, be as quick as you can. We only have half an hour nooning, and every minute counts. I go around to my room. You might buy something, then come with me and eat it.”

Roberta could hardly believe what she had heard. “Only half an hour to wash, go somewhere, eat your lunch and get back?

“Why the mad rush?” she exclaimed. “Doesn’t Mr. Queerwitz know there’s all eternity ahead of us?”

A wan smile was the only answer. Miss Nell Wiggin was not wasting time. She led the way to the cloakroom, donned her outdoor garments, and then, taking her new friend by the hand, she said: “Hold fast to me. We’ll take a short cut through the back stockroom. It’s black as soot in there when it isn’t lit up. Mr. Queerwitz won’t let us burn lights except for business reasons.”

Bobs found herself being led through a room so dark that she could barely see the two walls of boxes that were piled high on either side, with a narrow path between.

They soon emerged upon a back alley, where huge cans of refuse stood, and where trucks were continually passing up and down or standing at the back entrances of stores loading and unloading.

“Now walk as fast as you can,” little Miss Wiggin said, as away she went toward Fourth Avenue, with Roberta close behind her. If Bobs had known what was going to happen that noon, she would not have left the shop.

Fourth Avenue having been reached, Miss Wiggin darted into a corner delicatessen store. “What will you have for your lunch?” she turned to ask of her companion. “I’m going to get five cents’ worth of hot macaroni and a dill pickle.”

“Double the order,” Bobs said, and then she added to the man who stood behind the counter: “I’ll also take two ham sandwiches and two chocolate eclairs.”

“Oh, Miss Dolittle, isn’t that too much for you to spend at noon?” This anxiously from pale, starved-looking little Miss Wiggin.