A TALE OF RED PEKIN

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: A Tale of Red Pekin

Author: Constancia Serjeant

Release Date: June 08, 2013 [EBook #41951]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A TALE OF RED PEKIN ***

Produced by Al Haines.

A TALE OF

RED PEKIN

BY

CONSTANCIA SERJEANT

AUTHOR OF

"A THREEFOLD MYSTERY," "THE YOUNG ACROBATS," ETC., ETC.

LONDON

MARSHALL BROTHERS

KESWICK HOUSE PATERNOSTER ROW E C

1902

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER.

CHAPTER I.

CECILIA'S STORY.

I can remember quite well when we all came to China. It is four years ago, and I was eight years old, and you can remember when you are three, so father says. I am twelve now, and I feel quite grown up, that is because I am older than any of the others. Most people call me prim and old-fashioned, but mother says I am her right hand. Rachel is the next to me, but she is in a different generation almost, only nine years old, and quite a child. Then there is Jack, he is eight, and Jill, she is seven. Jill is not her name really—they all have Bible names—but we call her that because she and Jack are such friends, and always do everything together. Then there is Tim, he is only five years old, and little baby Anna. Baby Anna is so lovely, and the Chinese women are very fond of her. She has dark eyes, and rings of dark hair all over her head; but somehow she does not look like other children. She smiles, and yet she has a solemn look: that rapt look that the cherubs have, like pictures of the Blessed Lord Himself when He was a little child. Father says so sometimes, but mother does not like it. I never can think why, but she looks so sad, and once I saw her brushing some tears away. I think really, though I have never told anyone else, that mother is afraid baby Anna will not live. I heard the servants talking one day, and nurse said she was sure the baby would never live to grow up.

The Chinese women love her so much, they would like to bind her feet; they think it spoils us all, having such large feet—at least, those who are not Christians do, and even the others—well, it is just the very hardest thing in the world for them to have the bandages taken off their feet, but for the love of Christ they take them off at last, and then they are baptized—father never will baptize them until the bandages are taken off.

The Chinese are dreadfully, dreadfully cruel, and very cunning and deceitful, but father says they make splendid Christians. You see it's not a bit the same as it is in England—they have to go through such dreadful persecution if they become Christians; they have to give up everything for the sake of Christ's love, and you love a person far, far more if you feel you can give up everything, even life itself, for their sake.

When we first came to Cheng-si there was not a single Christian here, and the people did not like us much, but father and mother were so kind, and did so much for them when they were sick, that they got accustomed to us, and now they come from all parts, for miles around, to be healed.

You see, father is not like an ordinary Missionary, he is a doctor, too; he reminds me more of the Lord Jesus than anyone I have ever seen: he goes about doing good and healing the sick—he has such a beautiful expression. I have not seen many men, and I do not know exactly whether he is what people call a handsome man, I rather think not, but it is when he is healing the sick and speaking to them that there is that light on his face which makes me think of what is said about St. Stephen in the Acts: "They saw his face as it had been the face of an angel."

Uncle Lawrence is quite different: he is a soldier, every inch of him, a good soldier of Jesus Christ too. I have heard mother say so many times, and it is that which makes him such a good soldier of the Queen. She says the best soldier is the Christian soldier, and that very few people would contradict that now, because of Lord Roberts; and then there is General Havelock, and Sir Henry Lawrence, and a host of others. But Uncle does not look like father, and he does not speak much; you know what he is by his life more than by what he says. He has only one child, her name is Nina—Nina is three years older than I—she is my bosom friend. I never in my life saw anyone so wonderful as Nina, or anyone half so pretty; Nina is tall and dark, she has beautiful eyes, not at all like baby's, but more like wells of water, where the sunbeams lie; one can never be sad with Nina, she is so bright and sunshiny, like her laughing eyes; she loves me, too, dearly, and calls me St. Cecilia because I am so grave and old beyond my years.

Nina and Uncle Lawrence are always together, and she is the pet of the regiment—yet she is not spoilt. I have not known her long, only since the troubles began in China, and since they have been in Wei-hai-wei, which is about one hundred miles from this place; but our love for each other grew up mushroom-like in a few hours. She says she cares for me more than for any other girl. We write such long letters to each other, and when we meet she tells me stories about the officers, especially one, Uncle Lawrence's greatest friend.

We do not get the news here very fast, as we are quite in the country, but Nina wrote me a long letter yesterday from Pekin, where they are now, and told me what dreadfully cruel things the Chinese had done. She overheard a conversation between Uncle Lawrence and Colonel Taylor. Uncle Lawrence was talking of the risk of being captured, and of the awful peril which so many unprotected Europeans were in—it is far worse than death, for they torture people for days before they kill them.

"They should never capture anyone who belonged to me," said the Colonel, sternly, and he just touched his pistol with a meaning look.

Nina said her father went as white as death; she guessed what was passing through his mind. How could he kill Nina? Would it be right if it came to the worst, and to save her from a lingering death of agony? I told father, and asked him what he thought; for all the Europeans, so it seems, have resolved to kill their dearest and die, rather than fall into the hands of the Chinese. But father—well, father has such a strong, beautiful faith, he does not blame those who would do this, but for himself and for us—I know how he loves us—there were tears in his eyes as he spoke; still, he said he would not feel justified in doing this—he must leave it all with God, and He will take care of His own. I know what it cost father to say this, because I know what we are to him; but I also know that nothing, nothing would ever make him do what he would not think quite right: he does not blame others, but for himself it is different.

He and mother walked up and down for hours last evening, and part of the time I was with them, for they often take me into their confidence, and that is why I am so old for my years, I expect—the eldest in a large family generally is, they say; all father's thoughts were for mother.

"Oh, my dearest," he said—I think they had forgotten me—"I never loved you so well, and yet I am full of regret when I think of that quiet Rectory where you might have been now if it had not been for me. Do you remember it, the first time I saw you? I can see it all again: the Rectory garden, the old-fashioned grey stone house, shadows slanting over the lawn, and underneath the trees you were standing, the only young thing there, shading your eyes with your pretty hands; you were very much like our St. Cecilia, and I saw in a moment, beyond the mere beauty of your face, the Divine touch there, and I knew you were one of the Lord's dear children, and my heart went out to you, and I claimed you in my spirit then and there as my helpmeet, the woman whom God, in His love, had chosen for me. But if I had known what a future I was preparing for you, my beloved, I would never have spoken."

"A dear future," mother answered, gently clasping his arm with both her hands. "Would I have had it any different?"

"Yes, but, my darling—well, this news has unnerved me—Boxers are like devils possessed, and, if they should get hold of you and the children——"

And I saw father shudder; I had never seen him like this before: his faith had always been so strong, and now he seemed quite unnerved.

"They will not," said mother, calmly, and her eyes were soft with unshed tears, and yet had that patient, steadfast look the martyrs have. "But if there is trouble in store for us, oh! my dear husband, I would not have had it any different. God has been so good to us: we have been so happy, so happy together, there is nothing to regret; it was all ordered by a Divine love which never makes any mistakes; and it will be all ordered now," and she laughed a little to make him laugh, I think. "Oh! Paul, fancy my turning comforter!"

"Yes, darling," he replied, hurriedly, "I am ashamed of myself, and, more than all, ashamed of my lack of faith. What is our faith worth if it cannot stand this test? His strength is small indeed who faints in the day of adversity. God remains; He is over all, arranging every step of the way, and I can leave even you in peace now with this thought." And then I heard father say, and his face, which had been so wan and drawn before, was now radiant and bright: "'Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace, whose mind is stayed on Thee; because he trusteth in Thee.'"

But I crept up to bed and thought what dreadful news that must be to make father look and speak as he had done that evening.

CHAPTER II.

THE LETTER FROM PEKIN.

Mr. St. John might well look grave. "Upon the earth distress of nations, men's hearts failing them for fear." Yes, this text was being fulfilled. It was all very well for people in England to read of the awful things that were taking place in China, but to be on the spot—alone. Ah, there it was, therein lay the anguish—for he was not alone, if he had been he would not have cared. But his wife and children! it was the thought of them that caused him such unutterable pain.

Abraham knew something of this agony when he got up early that morning and saddled his ass. What a pathetic story! How difficult to read it without tears. It was just because Abraham felt it down to the very depth of his being, and yet never doubted God's love and God's power, that he was called faithful Abraham—God's friend.

It is easy to talk of faith to others—and to have it ourselves when everything goes well—but the faith which God approves is that which casts its burden on the Lord, that cries, "Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him."

Mr. St. John was a man full of faith. He was also full of love, or his faith could not have been so tried; and he was a man of prayer: that disquieting letter from Pekin had been spread before the Lord, and he got up very early so as to spend the morning hours in communion with Him. He had made great drafts on God's Bank, and his face had regained its usual serenity of expression. His heart, so torn and trembling overnight, was now calm with "the peace of God which passeth all understanding"—the peace which the Lord has promised to those who are stayed on him.

There was a slight sound. He looked up quickly; it was Cecilia—St. Cecilia the children called her—coming over the grass to meet him.

"Father, darling," she said, as she twined her arms about his neck, "I do wish I could do something for you."

"But you do, dear child," he answered, tenderly. "Mother's right hand: what more can we ask?"

"Yes, but father, you—you seemed so troubled last night."

"If I did, my darling, it was very wrong," he replied, gravely, "and showed a great want of trust in our Heavenly Father."

"I could not sleep for thinking of you, and wishing I were older, that I might really be able to help you."

"Poor little Cicely," he said, tenderly taking the sweet, earnest face between his hands. "Poor little right hand—old before her time. You must not take up our cares, darling. Indeed, if we older people had more faith we should never fret or worry either, but, instead, cast all our cares upon the Lord who cares for us."

"What are you and father talking about? You are both so grave," said Rachel, as she came running up to them. "Cicely looks just like that picture we have up in our room—St. somebody or other—I can't remember the name. Not anybody in the Bible, you know," said Rachel, garrulously, "but it's just like Cicely, when she is in white and grave, isn't it, father? Only she's got no halo round her head."

"You little chatterbox!" said her father, laughing, "it's a pity someone else has not a little more gravity herself."

"Oh, I can look very grave if I like, father. I practise sometimes in front of the glass, and I make such a long face—really, yards long."

"Did you measure it with your yard measure, Rachel?"

"Oh, no. But you know what I mean—as long as yours, and mother's, and Cicely's."

"Well, I am sure we all feel very flattered," said her father, smiling. "What a little pickle you are."

"A pickle! what is that? I thought it was something to eat. Is it nice?"

"Well, that is a matter of opinion," smiling. "Some people are very fond of pickles; others find them just a little bit too hot and strong."

Rachel was silent for a moment, then she dismissed the subject with a toss of her dark curls. "Father," she said, "do you know I am so glad no one is coming to be healed to-day, so we shall have you all to ourselves, and we can have some round games like Cicely says you had in England."

Mr. St. John's face changed. "Rachel," he inquired, gravely, "how do you know that no one is coming to be healed this morning?"

"Because Seng Mi said so, father. The people are angry about something, I don't know what, but I am so glad. Cicely, why don't you say you're glad, too, instead of looking like St. Cecilia at the piano?"

Cecilia flushed, and the tears came into her eyes. Her father took hold of her hand and pressed it between his own.

"Father, darling," she whispered, "has it come already?"

"God only knows," he replied, sadly, "but we shall be ready, at any rate, darling."

"Yes, father," she said, earnestly, lifting her sweet, grave eyes to his. "Do you know—I have often wished to tell you—Jesus is so precious to me that sometimes I long to suffer for His sake."

"My dearest child, God grant that He may be more exceedingly precious to each one of us every day. God be with you all in the time that is coming, and the dear native Christians. Ah, Cicely, my heart bleeds for them."

"Why, father?" asked Rachel, who had caught the last words.

"Because, Rachel, I am afraid there is a time of great trouble in store for them—terrible persecution. Indeed," he added, "it has begun already; in the letter which I received last night from Pekin, your uncle speaks of the dreadful suffering, not only of Europeans, but also of the native Christians—there have been hundreds of martyrs for Jesus already."

"Have there, father?" Rachel's gentian-blue eyes were very wide open indeed—"I haven't seen anybody being persecuted here yet."

"No; but my dear little Rachel, it has not reached us yet, God be praised for that; but it may come any day—it might even come to-day."

Rachel was silent for a moment, and then suddenly reverted to what had been uppermost in her mind—of paramount interest to her: "About the games, father," she said, coaxingly, "if mother will give us a holiday, will you come and have some games with us? I should like blind man's buff and hide and seek; Cicely and I will hide, and you shall find us."

"Rachel," said her father, gently, "I should like to do what you wish, but first I must tell you a story, and then you shall decide yourself about the games afterwards."

"Oh, a story, father, I shall like that; let's sit down here under this banyan tree, and then we can listen nicely," and Rachel flung off her big, shady hat, and settled herself down by her father's side, prepared to drink in every word. With the dark curls tossed back from her little, eager, upturned face, and her sparkling blue eyes, she made a pretty picture, and formed a pleasing contrast to her equally lovely sister—indeed, Cicely's was the lovelier face of the two, for God Himself had taken up the brush and been the Painter there.

"Once upon a time—that is the correct way to begin, Rachel, is it not?—there lived a very wicked and cruel Emperor, so cruel that his name has become a proverb."

"Nero," exclaimed the children in one breath.

"Yes, that is right," said Mr. St. John, continuing his story; "there were a great many Christians then; they were people who loved the Lord very dearly, for in confessing Him they ran the risk of the most awfully cruel death—Nero had his spies everywhere."

"What is a spy, father?"

"You will see, dear; they were people who pretended to be what they were not; they professed to be friendly with the Christians—even to be Christians themselves sometimes—and they would go to their secret meetings held in the catacombs."

"The what?" said Rachel, "what long words, father."

"The catacombs were vast dark passages underneath the city where the Christians used to meet and worship God; but you ask so many questions, Rachel," said her father, smiling, "that I lose the thread of my story."

"You were explaining about the spies, father," put in, Cicely, gently.

"Oh yes, to be sure; well, these spies got to know all about the meetings, and they came too, pretending that they were Christians themselves, and then denounced everyone who was there to the Emperor."

"How dreadfully mean," said Rachel, her eyes flashing.

"Yes, dear; well on one occasion when a great many of these followers of Christ were taken prisoners, Nero gave a large entertainment, and actually lighted his gardens with their bodies. Now, Rachel, part of my story is true and part is imagination—that part, I grieve to say, is true. Now I want you to think of a man, a Christian man, who lived with his wife and family some miles from Rome in comparative safety; this man knew—his children knew what their fellow Christians were suffering, and yet that very evening they made merry and had games, and a feast in the garden."

Rachel's eyes were full of indignant tears. "How could they, father?" she said, "how could they? I should have cried all the evening! I couldn't have helped it."

"Just so, dear," said Mr. St. John, gently, and he laid his hand tenderly on the child's hair. "Last night I got a letter from your uncle from Pekin—it's a sad letter, Rachel; Christians are being tortured and killed to-day in China, just as they were 2,000 years ago in Rome. And I know my little girl would be the last to wish to make the day that is bringing so much sadness and pain to our brothers and sisters in Christ a gala day with us."

"No," said Rachel, with a great sigh, "of course I shouldn't like that, but oh, how I wish the Christians were not being killed, because it would have been so nice to have had you to ourselves for a whole day, father."

"Now, my dear little girls," said Mr. St. John, rising, "I am going in to get some breakfast, if mother will give me some; you had yours long ago, I know, but I have been out here and not thought much about the time; then I should like to have a big prayer meeting; we must try and get the dear native Christians together—they will need all our love to-day."

"Yes, father," said Rachel, "may we go and ask them to come, I should like that," she added, dancing and skipping about.

"Ask your mother, darling, she must decide. Christine," he said, as his wife came up, "do you think it would be wise for the children to take round the invitations for the prayer meeting?"

"I hardly think so," replied Mrs. St. John. "The village is in the most unsettled state, and there seems to be danger of a general rising."

"I must go and find out what it all means," said Mr. St. John, quietly.

"Oh, my dear husband, do be careful. Do not run into any danger."

"I shall not, my dearest; never fear."

He kissed her and the children tenderly. But even as he spoke, he heard in the distance a murmur like the roar of the sea, and there was Seng Mi standing in the doorway with a white, scared face.

CHAPTER III.

THE RISING IN THE VILLAGE.

"Teacher, they are coming—burning, looting, killing!"

"Not our people, surely?" said Mr. St. John.

"No; but they will join, never fear, when their blood is up; they will forget all your kindness. The lady and the children should retire."

"Yes, yes, Christine," said Mr. St. John, hurriedly; "go into the blue room and remain there with the children until I join you; but if I am not able to do so you know what we arranged—put on the Chinese dress, escape through the house, which will bring you out on the road to Wei-hai-wei, and may God bless and be with my dear wife and children."

"Paul, a wife's place is by her husband's side."

"Yes, yes, my dearest, but the children!"

"Oh, Paul, I am torn in two. I do not know what to choose.

"Darling, you have not to choose, God has chosen for you; only one way lies open."

"Yes, but oh, my dear husband—you must let me weep for one moment—to know that we may never meet again, that you may be going to death—even torture!" She lifted her lovely, agonized eyes to his.

"It is very, very hard to bear, my dearest; the only thing that makes it possible is the love of Christ; but, Christine," he said, hopefully, "I believe we shall meet again in this world; if not, my darling wife, you will know that I shall be with Christ, and be the first to welcome you to the City of the King. All the paths lead there in the end, do they not?"

"Yes, yes, my beloved husband, we shall meet again in glory, even if we may not here. Good-bye, good-bye! Cicely and Rachel, come with me, darlings."

Rachel had been wondering what it was all about; why her mother was crying, and why they were saying good-bye; but she prepared to follow Mrs. St. John, to whom she was very devoted. Cicely still clung to her father.

"Let me stay with you, father, father darling." The little white face raised to his, the gray eyes, so like his wife's, all touched him infinitely; but he loosened her arms gently from about his neck.

"My sweet child, it could not be: you must let me judge, darling. I should love to have you, but it is quite impossible."

"Oh father, do—do let me stay."

"Cicely," said her father, tenderly, "I know you do not wish to unnerve me. I am sure you do not wish to make it harder for me, and, my dear little girl, it would increase my pain and anxiety in a ten-fold degree if I knew you were not in safety. Be my own sweet, brave child. Kiss me and then run up to your mother. I know you will do all you can for her."

"Yes, yes; good-bye, good-bye, father darling."

"Good-bye, my own dear child, my precious Cicely. Please God, we shall meet very soon again."

He watched her as she turned slowly away, weeping quietly.

"The bitterness of death is passed," he said to himself. "Now may the Lord enable me to do His will whatever it may be, and face with courage whatever lies before me."

The room into which Mrs. St. John had retired with the nurse and children opened on to the side of the house, and it was possible to get from the verandah to the Mission-house, and from the Mission-house again to that of one of the native Christians hard by, and so on and so on—from one house to another, if only the people were willing—without ever being seen in the public street for about a mile, till the road to Wei-hai-wei was reached. It had been decided between the husband and wife that if things looked serious they should escape in this way from the house and village to Wei-hai-wei. They were to put on Chinese dresses, so as to court observation as little as possible, and take money and food for the journey.

Mr. St. John moved quickly forward to the front of the house. He was beloved in the village and widely known, and hoped that his influence might prevent further bloodshed; and then he could not leave the native Christians. If only he could persuade the rioters to return, something might still be saved, and he would gain time for his wife and children. He lifted up his heart to God, and walked forward into the courtyard, his head erect, his face lighted up with the courage which God gives to those who put their trust in Him. He needed it all to-day. The sight which met his view, when he turned the corner, was disquieting in the extreme. The din was terrific; the courtyard a mass of howling, frantic rioters. Glancing hastily back to the house to see that all was right there, he suddenly turned pale. On the verandah overlooking the courtyard stood a small, slight figure he knew only too well—the little, white face of the child whom he loved.

"Oh, father, father darling, don't go; oh, come back to us; they will kill you."

"Cicely, for God's sake, my darling, go back to your mother. I must do my duty. You are only increasing my anxiety tenfold; go back at once." The little figure suddenly disappeared, and, with a sigh of relief, Mr. St. John went out and faced the angry crowd. What he saw gave him the keenest pain and apprehension. Their hands were literally red with blood. They had killed several of the native Christians, dragging their bodies along with them in fiendish triumph. One poor fellow lay at Mr. St. John's feet; he was suffering from frightful wounds, but he was still alive, and as for the moment the attention of the crowd was distracted by a fresh disturbance from without, the clergyman managed to draw him into the house, and place him for a moment in a position of safety. He did what he could for the poor fellow; gave him a long draught of water, and staunched the flowing blood, but it was evident to the practised eye of the physician that his life was ebbing fast away. Yet the cross of Christ still triumphed—tortured, wounded, bleeding to death, on his face there lay the light which was not of this world.

"Teacher," he murmured, with a bright smile of recognition, "it is all over, and I am glad. Only a few minutes more and I shall be with Jesus. Do not look sad, I have no pain, and I am going to the land where there is no more weariness, or persecution, or suffering." Suddenly his whole countenance was eradiated with joy. "I see the gates of heaven opened," he cried, with ecstasy, "and Jesus on the right hand of God waiting to receive me. Oh, what a blessed thing to belong to Christ!"

"Dear, dear fellow," said Mr. St. John, tenderly, holding the poor man's hand in a kind, gentle clasp. "How thankful I am that the Lord sent me here. It has made it hard for you in this world, but this 'light affliction, which is but for a moment, worketh for us a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory.'"

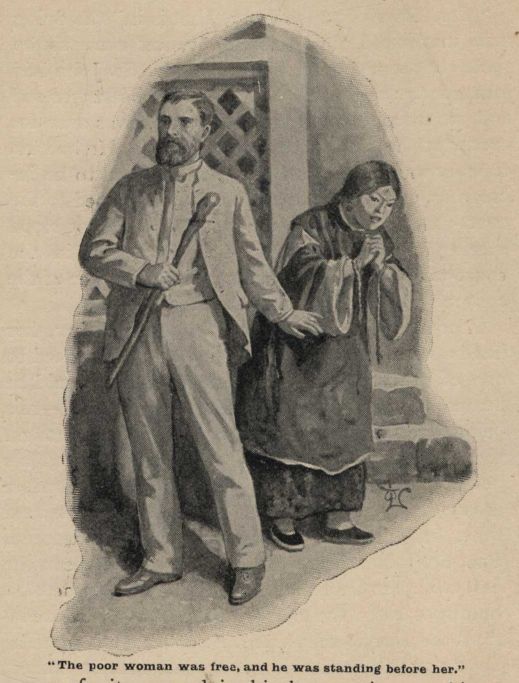

"Yes, the glory; the glory, that is it," the dying man murmured almost inaudibly, and even as he spoke he seemed to pass away. Mr. St. John laid him gently, reverently down. His heart was sad and yet throbbed with joy. The pain was over for ever, and he was at rest with Jesus. He had no time for much thought; the noise seemed to be increasing without, and once more he turned to the court-yard. What he saw there sent the hot blood surging through his veins—tied to a post in the court-yard was a poor woman he knew, one of the converts who had but lately been baptized.

Poor Daig Ong stood there in agony of fear, her hands were tied behind her back, and fastened to one of the posts in the court-yard; she would be beaten to death unless someone interposed—this being a very favourite manner of execution amongst the Chinese. The man nearest to her raised his heavy stick; there was a dull, sickening thud, a groan of pain. The man lifted his stick a second time, but, in a moment, before it could descend, Paul St. John was upon him. He had not been the best athlete at Cambridge for nothing. With one blow he dispossessed the man with the stick, the next instant the poor woman was free, and he was standing before her, his head thrown back, his nostrils dilated, eyes ablaze with righteous indignation. Stern and beautiful he looked as he stood there, yet as he gazed over that sea of cruel yellow faces, more like demons than men, his anger died away, and a vast wave of pity surged in his breast; it was akin to that pity the Christ felt when He gazed at Jerusalem and wept over it. All this hatred and cruelty and hideous passion were the result of devil thraldom—"and such were some of you." Yes, indeed, without Christ, wherein should any of us differ?

How little we in England, who speak of the reproach of Christ, know what it really means in a heathen country. Perhaps we are coldly treated, and we think it hard if we have to put up with a sneer or a few unkind words, and flatter ourselves with the conviction that we are bearing His reproach that we are suffering persecution; but when we look on the other picture our paltry woes dwindle into insignificance. Indeed, when we read, as we did last year, of the awful hardships and privations, the torturing deaths, which our missionaries and the native Christians underwent, then we would sink into the ground for shame. We feel that we can never thank God enough for His mercies to us, the while we look on our fellow Christians over the sea with an admiration a little, maybe, tinged with envy, in that they were accounted worthy to suffer for that beloved Name, dearer and sweeter by far to every Christian than any other on earth.

For a brief moment there was a respite; a mob ever recognizes power, and this was something they could not understand. What if the white man who stood there so fearlessly towering above them were an incarnation of one of the gods? But no, the pictures of their gods were far different from this: they had cruel, wicked faces, like their own. Still they hesitated. They had heard of this man, this great doctor, of his wonderful cures. Suppose, now, he used his magic upon them, inflicting some sore disaster, some awful punishment. Paul St. John noticed their indecision and took advantage of it to whisper to the poor woman behind him to slip back by degrees, and so make good her escape. They were standing together at the entrance of the courtyard; the crowd, for the most part—the mad, surging, bloodthirsty crowd—stood between them and the house. The eyes of the people seemed to be drawn to him as the one central figure; they watched him as a man on guard would watch every movement of his opponent in a deadly duel.

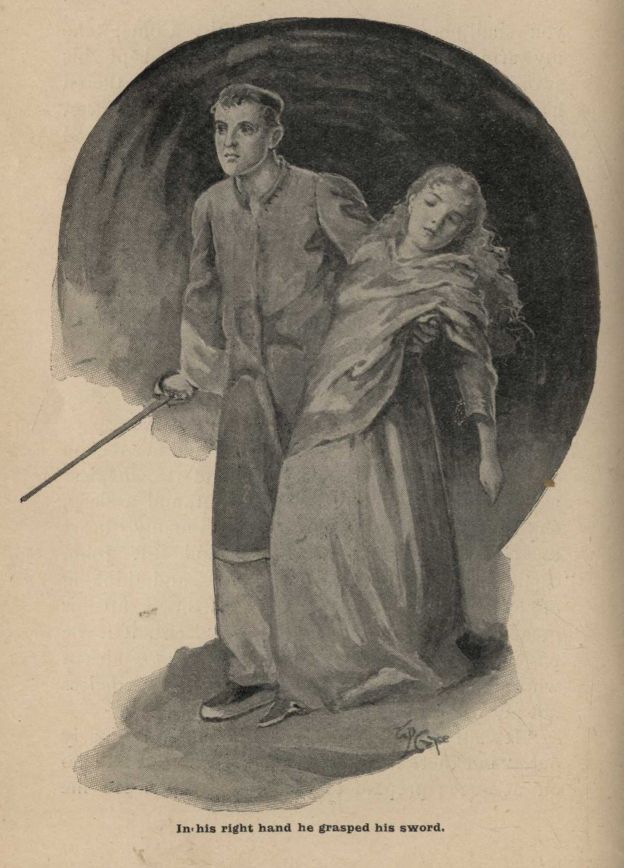

Daig Ong was permitted to pass out unperceived, and found refuge in a house belonging to one of the native Christians. When she was gone Paul St. John breathed more freely. He knew that unless God wrought a special miracle in his favour this could not last long; yet he felt no fear, Jesus had never been so near. It seemed to him that the Lord was actually standing there beside him, and something of the rapturous exaltation of his soul was visible in his countenance. He raised his hand to speak. The spell was broken. With one hideous cry, more dreadful, more cruel in its lust for blood than that of any wild beast, they sprang at him and threw him down and trod him underfoot. It was like a storm picture—you look out and see the gallant little vessel battling with the waves, borne up upon their crested billows, and the next moment they roll over it, and only a ripple, a few bubbles, show the place where it had been. A few minutes since, and Paul St. John had stood before them like a beautiful avenging angel; now he lay there silent and still, with his white face upturned to the pitiless sky.

CHAPTER IV.

CECILIA CONTINUES HER STORY.

So many dreadful things have happened since last I told my story, that if I had not promised Nina, I do not think I could have written any more; but since the troubles began in China, Nina and I agreed to write a little history of what is happening every day, and afterwards we shall compare notes, and then, as Mother says, it will interest our friends at home, and perhaps some of the Missionary papers may like the account for their magazines.

It seems years since last I put down anything, and yet it is only a few weeks ago since that day when we were all together at Cheng-si. How true it is we know not what an hour may bring forth. I remember the day of which I am speaking so well; it began so brightly, such a lovely morning. Rachel and I got up early and went into the garden with father. That hour seemed to me afterwards one of the most precious in my life; it made one understand a little of what the disciples must have felt when the dear Lord Jesus had been laid in the tomb, and they thought of the last time they were with Him. How tenderly they would recall His sweet, gracious words, and His loving looks.

I felt like this about father when he was parted from us. We had been sitting in the garden with him, Rachel and I, and he had been telling us stories, when all of a sudden we heard a noise, almost like the distant roar of the sea, and Seng Mi told us the rioters were coming, and then we had to say good-bye to father. I wished, oh, so much, to stay with him, but I could not disobey him, especially when I knew it would only have increased his pain and anxiety, but I crept out of the room where mother and the others were, and went on to the verandah which overlooks the court-yard. Oh, it was a dreadful sight! I had never seen such fiendish, cruel looking people before. They had got hold of poor Daig Ong and were going to beat her to death. Father did not know anything of what was going on when he first came out, the crowd being so dense between him and Daig Ong, but I was above them, and saw it all. They dragged her along, shrieking for mercy; it was dreadful! I can hear her screams now sometimes! and they tied her to one of the posts at the entrance of the court-yard. I pitied poor Daig Ong with all my heart; I would have done almost anything to save her, but when I saw father I seemed to forget everything else but him. Just then he looked round and saw me, and I cried out to him to come up to us. I could not help it, though all the time I knew it was useless. When I saw that my being there only made him miserable, I slipped back and ran to the room where mother was and begged her to leave the others and come with me, and all the time I cried to the dear Lord Jesus to help us, and protect poor Daig Ong, and to save father from the cruel people outside. Mother turned very white when I spoke to her. She did not know how to leave little baby Anna. It was one of baby's bad days. She did not seem in any pain, but she lay back in Nurse's arms very quiet and still, and looked up at her with intently solemn eyes.

Mother had put on the Chinese dress, and all the others were dressed in the same way; and appeared ready to start at a moment's notice. Mother's face was very pale, but she had that patient, enduring expression with which the martyr saints are always drawn; it was only her eyes that were full of pain. I do not know why I wished her to come, save that I had always been accustomed to think she could do anything, and to save father.

When we got down to the portico he was nowhere to be seen. We stood on the steps and looked out over a vast sea of cruel, wicked faces. At first I felt no fear, partly because I was with mother, and then it was such a relief to me to see that they had left off beating Daig Ong, and that father was not there. I kept on wondering where he was, and felt sure he had escaped with Daig Ong.

Now the great danger seemed to lie in the possibility of their rushing the house. Mother had whispered to Nurse to take the others on the way that had been arranged: through the Mission-house and huts, out of the village, and we were to follow afterwards.

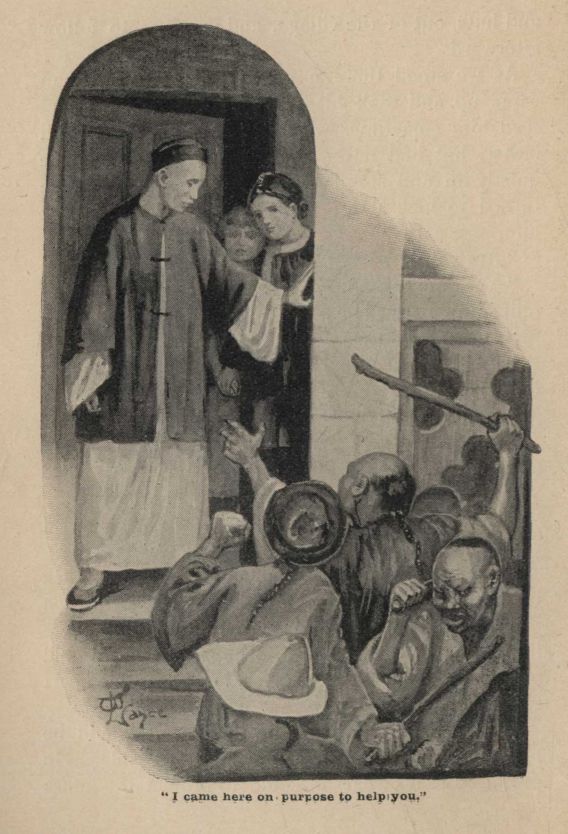

As we stood there a grave Chinese gentleman came up and took his place at our side. I had seen him sometimes when he came to study with father, but had never spoken to him. He came quietly up and stood beside us, but he never once turned to look at us, though mother looked up at him.

"Are you Mr. Li?" I heard her say.

"Yes," he replied, simply. I saw a great wave of relief sweep over her face.

"Do stay with us, do not leave us," she said.

"I intend to remain here," he replied, quietly, but he did not even then turn and look at us.

"And you will do what you can?—My husband?"

He did not reply to the last, but only said very simply—

"Madam, I came here on purpose to help you."

"God bless you," said mother, fervently, and I saw her lips move, and knew that she was praying.

Mr. Li was not a Christian, but he was so struck by mother's wonderful calmness, the peace in which she was kept when so many dreadful things were happening all round her, that he felt he could hold out no longer, and that very day he yielded his heart to Christ.

By-and-by, Mr. Li said he thought it would be best for us to get away as soon as possible. He promised to do what he could to protect the house and the native Christians, and when we again spoke of father, he said he had seen him helping Daig Ong out at the back of the court-yard as he entered.

"I will find him," he added, "and will let him know that I have seen you, and he will soon overtake you."

And so we went away. The others had started, and we hurried after them; but first mother made me put on the Chinese dress, and then, leaving the deafening sounds behind us, we crept on into the Mission-house. We were only just in time. As we left the room, which mother locked behind her, we heard someone trying the other door, and knew that it would not be long before they forced the lock, and then—

Mother hurried me on through the Mission-house, carefully locking the doors behind us, on into the first house, where we saw poor Daig Ong. Mother stopped to say a few words to her, and then we passed on again; we dared not stay, for the rioters might guess at our escape and bring us back again. House after house we passed through safely, for the people in the village knew us and loved us, until at last we reached the road for Wei-hai-wei, and caught a glimpse of Nurse and the others on a-head. They were going very slowly, and we soon overtook them.

CHAPTER V.

A TERRIBLE WALK.

Mother took baby Anna in her arms, and baby smiled and touched mother's face with her little hands, then looked up at the sky again with that solemn, wondering look of hers; and the next day, when the sun was setting, and its glory fell on her little upturned face, Jesus called her to Himself, and the angels carried her away from us to Heaven. It reminded me of a piece of poetry out of a book of mother's, called "Voices of Comfort." I learnt it by heart to repeat to father, and if I can remember it, I will write it down, because it is such a lovely piece:—

They are going—only going—Jesus called them long ago!All the wintry time they're passing,Softly as the falling snow.When the violets in the spring-timeCatch the azure of the sky,They are carried out to slumberSweetly where the violets lie.They are going—only going—When with summer earth is drest,In their cold hand holding roses,Folded to each silent breast.When the autumn hangs red bannersOut above the harvest sheaves,They are going—ever going—Thick and fast, like falling leaves.All along the mighty agesAll adown the solemn time,They have taken up their homewardMarch to that serener clime,Where the watching, waiting angelsLead them from the shadow dim,To the brightness of His presence,Who hath called them unto Him.They are going—only going—Out of pain and into bliss,Out of sad and sinful weakness,Into perfect holiness.Snowy brows—no care shall shade them;Bright eyes—tears shall never dim;Rosy lips—no time shall fade them;Jesus called them unto Him.Little hearts for ever stainless,Little hands as pure as they,Little feet—by angels guidedNever a forbidden way.They are going—ever going—Leaving many a lonely spot;But 'tis Jesus who has called them;Suffer, and forbid them not!

Rachel said baby Anna died because she thought it would be much nicer to go to Heaven than to Wei-hai-wei—but the little ones did not understand it at all, they seemed to imagine she was away on a visit. Tiny Tim said he hoped they would be kind to her where she had gone, and give her a lot of presents; and we all kissed her little white face—it looked like a flower somehow—and folded her sweet hands on her breast, and then the rest went on, all but mother and me, and we laid her gently down, strewing the earth lightly over her, and covering her little grave with flowers. Then we knelt beside her and prayed, and after a little time we walked on and overtook the others. Nurse said it was a good thing baby Anna died, because the poor little thing would have suffered so much, and I knew mother thought so too, but still she could not help quietly crying, because her arms were so very empty. I shall never forget that walk to Wei-hai-wei. Rachel thought it was great fun at first, and so did Jack and Jill. They liked wearing the Chinese dresses and doing no lessons, but they soon got tired of walking, especially Tiny Tim, who kept on calling out for father to come and carry him.

The sun was very hot, but we were obliged to press on, we were so much afraid of being pursued and taken back again. Sometimes we would see a band of rioters coming, and have to leave the road and hide; and once we were overtaken, and the people looked at us very fiercely and called us "foreign devils." Tiny Tim was very frightened, and hid his face in mother's dress, and I thought we should be killed. Somehow I did not feel much fear. I remembered the talk I had with father, and Jesus was very near, and it seemed much better to go to Him and be at rest for ever than to be hungry and faint and tired, and to go through the pain of so many partings as we had gone through lately. But the Chinese did not kill us as they did so many of the missionaries. I think they were afraid to do so, as we were getting nearer every hour to places where English soldiers were; but they took away a great many of our clothes, and stole our money. Nurse had her money in her hand, and they beat her knuckles with a stick till she dropped it, and then they ran away laughing.

When we got to the first village we asked to see the Mandarin, and told him how we had been treated; our clothes and money taken, and how were we to get on, and what should we do for food? But instead of helping us, he was very cruel indeed. He hated the Christians, and said he wished we had come yesterday, as then he would have killed us all, but now he had had orders, owing to the Empress being so merciful, not to do so, but just to send the "foreign devils" away. So he sent us on to the next village, and though we were tired and hungry yet we were glad to go, as he seemed so fierce and cruel. In the next village the Mandarin was kinder, and gave us a little rice to eat, but he said he could not keep us. This happened in all the villages through which we passed.

Sometimes they would give us a little food, but they would not allow us to rest or give us any carts to ride in. They always took us outside the village, and then went away. Mother said afterwards it was because they were afraid of killing us, and yet they did not wish to have us with them. It was a weary, weary time, especially for the little ones, but through it all God never forsook us; indeed we seemed to be kept in constant communion with Him, and as we drew near to Wei-hai-wei a most wonderful thing happened.

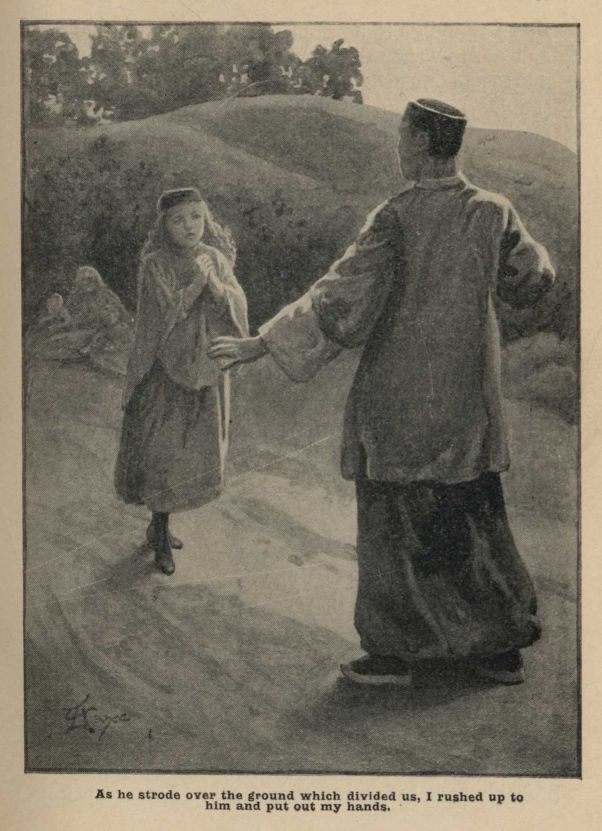

We were very weary, and sat down by the roadside to rest. The children said they could not walk a step farther, and though it was not, of course, quite safe to do so, yet we were so near a place of safety that mother made up her mind to rest there for the night. We went a little off the high road, to a place as much screened from observation as possible. Mother and Nurse sat down and made the little ones as comfortable as they could, and then, as we always did, we asked God to take care of us and be very present with us during the night. We had hardly gone off to sleep when we heard steps approaching Tramp, tramp, came the footsteps, nearer and nearer. I was wide awake in a moment, and my heart stood still, for, in the gathering darkness, I saw plainly a tall Chinaman approaching. He seemed to be alone, but this might not be the case. What if he were the leader of a band of Boxers! I did not mind so much for myself, but I could not bear to think of the others being tortured and killed. He looked terrible in the darkness as he came towards us. I did not know what to do. I only thought, in a wild kind of way, that I would go to him and ask him to take my life and not to waken the others. I could talk Chinese a little, and hoped to be able to make him understand. I got up quickly, without even disturbing mother—she was sleeping heavily, for sorrow, as the disciples of old—and as he strode over the ground which divided us I rushed up to him and put out my hands, and then I remembered nothing more till I heard a voice—a loved voice that I never thought to hear again in this world. I dreamed I was in Heaven with father, and he wore a Chinese dress, but when I came rather painfully back to earth again, the first thing I was conscious of was that I was in the arms of the tall Chinaman I had seen.

"Don't hurt them," I cried out in an agony, "kill me instead, but do not hurt them: they have suffered so much already."

"Cicely, my darling, don't you know me?"

The voice again. I was so weak and unnerved, or I should have recognized before my own precious father. I went off once more then, this time for joy and thankfulness, and woke to feel his strong arms round me, and knew that God was good, and that my pain was over. My care and anxiety was gone, for was not father with us again? Were not his arms round me?

"Humanly speaking," said father, in answer to our breathless questions, "my escape is all owing to Mr. Li. He stood between me and what would probably have been a torturing death. I was struck down, and when they saw I was not dead, their rage knew no bounds—and that noble fellow defended me, and did what he could to protect our property till the Mandarin came. The Mandarin put me in prison, but Mr. Li rescued me, provided me with this dress, gave me food and money for the journey, brought me on my way, and here I am. I often thought of Onesiphorus. 'He oft refreshed me, and was not ashamed of my chain.' Thank God! Our loss has been his unspeakable gain. He told me last Tuesday night that he could hold out no longer. He was full of wonder at the peace in which we were kept whilst death was so near and our property was being destroyed, and especially at your calmness, my darling. Under God it was just the touch that was required. He yielded then and there, and gave himself to Christ. He is anxious to make a public profession of his faith by being baptized as soon as ever the opportunity occurs. He will make a splendid Christian, for he has counted the cost and found Christ worthy."

"Thank God," said mother, fervently, "this one soul saved is worth all the pain."

"I knew you would feel like this, Christine. The Lord has been very good to him and to us. He has brought us all together again. We are all here, are we not, dear wife?"

Mother did not answer, but I saw her bosom heave. Father looked round anxiously, and the tears slowly welled into his eyes. He put his arm round mother.

"It is all right, Christine," I heard him whisper. "He knows best. She has been saved so much pain. When was it, my dearest?"

"Last Wednesday, Paul."

"And to-day is Friday. Three days in heaven beholding the face of the Father. Let us thank Him, dear wife, for this also."

We all knelt down upon the grass, and after that I heard father and mother talking far on into the night, and, looking up, I saw God's stars in His sky, and felt how very near He was, and then I went to sleep, and the next day, towards evening, we met some English soldiers and arrived at Wei-hai-wei.

CHAPTER VI.

NINA'S STORY.

I promised my cousin Cicely St. John that I would write a little history of what took place after we were separated from one another. She is going to do the same; and then some day when we go back to England we shall get it all put together and have it published in one big book. It has always been my ambition to write a book, and I am quite sure that I can write. People all have their particular gifts—writing is one of mine. I was not very good when I was at school, but I never found the essays any trouble at all. And when I was fourteen I got a five-shilling prize in a magazine, and my story was published in the Christmas number. It was illustrated, and the picture in the place of honour on the cover. I was so delighted about it and so was father, but then he always does love everything I do. People say he spoils me, and perhaps he does; all I can say is, it is very nice being spoilt! I am always happier when I am with father and his friends than with girls of my own age.

I never cared much for girls; the little ones talk about their dolls and the big ones about their clothes. I like hearing father and his brother officers talk and tell tales of sport and adventure. Of course I know father would have liked me to have been a boy. He must have been disappointed, though he never said so, because then I should have been a soldier like he is, and gone to the war in South Africa, or perhaps have been here in Pekin, just as we are now.

It is a month since we came to the Celestial City, and such a long time since I stayed with Uncle Paul and Aunt Christine. We went to them when we first came out to China. I had never seen them in my life before.

Cicely is different from other girls, and I love her dearly. She is much younger than I am, two years younger, but she seems almost as old. She is so grave and a little old-fashioned; somehow I feel better when I am with her and Uncle Paul—they make me want to be good. I often wonder where they are, and hope things are not as bad for them as they are with us, for here in the Celestial City things look very black indeed. Father wishes he had left me behind in Wei-hai-wei, but I would much rather be with him, even though the worst comes and he has to kill me himself. Uncle Paul thinks one ought not to do this, but then Uncle Paul is an angel. When I am with him I feel all the time a longing after something better. I told Mrs. Ross about him. Mrs. Ross is my great friend here. She is young and very pretty, and she met Uncle Paul once. When I told her what he made me feel like, she said, "Yes, I know, dear, he makes you feel as if you didn't care how your frock fitted, but when you get away you think to yourself you may as well look as nice as you can." Mrs. Ross has only been married a few months. She came here just after her honeymoon. She has the most wonderful eyes I have ever seen, like the stars in the soft, dark sky. She and I and nearly always together, though she is years older than I am. Still she says she is very glad to have me for her friend, as there are so few girls out here. Captain Ross looks stern and troubled, and very careworn, but all the men have that expression now, and if only you saw the faces of the Chinese you would not wonder much; they are so dreadfully cruel and revengeful, and they look at us as if they hate us and would like to murder us all. If they killed people outright it would not be so dreadful; but they torture a person for days first; they do this to their own people, how much more then to us, if they had us in their power?

It is the cruel Empress who hates the foreigners, and it is her emissaries who have stirred up the people against us. The Boxers are her tools really, and the ignorant people are told all kinds of things which they believe, that the Europeans take their little children and kill them, and that it is our presence here which causes the lack of rain, and then they pretend to see most wonderful apparitions, those who appear always bearing the same message, "Kill! kill!" The other day they declared that a marvellous vision appeared in the sky; it was a spirit girl, they said, with a lamp in her hand. Father and I went out to see it, but of course we did not see the girl, but only a brilliant light in the sky, and the Chinese, who are very superstitious, imagined the rest. But what caused more stir and alarm than anything else was the mysterious Red Hand which suddenly appeared in Pekin. Mrs. Ross and I saw it on a house one day, and then again on another, and as the people caught sight of these dreadful Red Hands they gesticulated wildly, and seemed terribly excited. Mrs. Ross was very frightened, as she thought it meant that the Boxers were going to kill all the inmates of the houses on which the Red Hand appeared, but Captain Ross said he had been told by someone who knew that we, the foreign devils, were accused of marking the houses, and wherever this dreadful mark appeared a curse was sure to follow; in seven days one of the inmates would go mad, or in fourteen days they would die. This was just before a most dreadful event occurred.

CHAPTER VII.

A PAINFUL DISCOVERY.

Several days passed by. One gets accustomed to everything, and we were getting used to the big fires at night and all the mysterious warnings we had had, and I was getting very tired of not being able to run about as in the old days before we came to Pekin. It was a lovely morning, and I made up my mind to go round and see my friend, Mrs. Ross. I was allowed to go and see Mrs. Ross, but when there I was never supposed to be out of her sight. Father was busy when I left, so I did not see him, but Phoebe, our old servant, followed me with a great many injunctions and warnings—at which, I am sorry to say, I only laughed. The sunshine seemed to intoxicate me—I revelled in it—I could no longer feel any fear; afterwards I thought I must have been mad that morning. I turned round in the middle of my flight down the path which led to the house in which Captain and Mrs. Ross lived.

"Phoebe," I cried, shaking back my curls, which, somehow, always would come tumbling about my face, "Phoebe, you may depend upon it the Chinese are not nearly so black as they're painted; anyway, black or yellow, or whatever they are, it's a lovely day, and I'm going to enjoy myself."

"And what am I to tell your pa, Miss Nina?"

"Oh, tell him anything you like—why, tell him the truth to be sure—that I've gone to spend the morning with Mrs. Ross."

"Miss Nina, I don't like the looks of you this morning. When your eyes are as if there was little imps a-dancing in 'em, then I looks out for squalls."

"Thank you, Phoebe," I said, laughing and making her a mocking curtsey. "My eyes feel very flattered, I can assure you."

"Oh, they're well enough, and bright enough," she replied, grudgingly, "but I should like to see a bit more soberness about them; why, when I was your age, miss, I was married. Mr. Larkins—

"Poor man," I ejaculated under my breath.

Phoebe did not hear; she was lost in reminiscences of the past.

"Poor, dear Mr. Larkins, he were took quite sudden like; his mother died of heart complaint, and yet I never thought to say to Larkins, 'Who knows, my dear, but you might be took the same yourself, one day.'"

"I should think not, Phoebe; it would have made poor Mr. Larkins very uncomfortable if you had. I daresay," I added, under my breath, "he was none too happy as it was," but, like all deaf people, the very thing I did not mean her to hear she heard at once, and turned upon me angrily.

"Not happy, miss! As happy as the day was long was Mr. Larkins, and a deal happier if the days be these here days in China."

"Oh, Phoebe, the day is bright enough; there is nothing wrong with that."

"The day is all right for them as wasn't kept awake all night by those bloodthirsty villains."

"I heard nothing, Phoebe; I was asleep."

"It's all very well for them as can sleep; but, there, you're only a child, after all."

"Why, Phoebe, you said a minute ago that I was old enough to be married," and with this parting shot I ran away.

Poor old Phoebe; our troubles pressed sore upon her. I had never seen her so put out before. She had been in our family for forty years, and was, therefore, privileged to be very disagreeable sometimes. As I ran down the path I met Mr. Crawford; he saluted, hesitated, and finally stopped short.

"Whither away, Miss Nina?"

He had such a kind, honest face, one of those you feel instinctively you can trust.

"I am going to see Mrs. Ross."

"All by yourself? Pardon me, does the Colonel know of your intention?"

"Oh, yes—that is, I don't know; father was out when I left, but Phoebe saw me go, and I had to listen to lectures yards long. I hope," I added, saucily, "that I shall not have to listen to any more."

His boyish face had grown quite grave, his honest eyes had a look of apprehension in them, but he spoke lightly.

"I see you are a very determined young lady, but perhaps you will allow me to accompany you so far; then, when I have seen you safe in Mrs. Ross's hands, I can make my report to the Colonel and set his mind at rest."

"Oh, you can come if you like," I replied, grandly. I was accustomed to have a great deal of attention; indeed, I could not have received much more had I been a little princess. "One would think I was the most precious thing in the world."

"Well, are you not?" he asked, gravely.

"It depends what precious means," I replied, sapiently. "If it means very good, I am afraid I am not that—at least, not half so good as Cicely."

"Who is Cicely?"

"Cicely St. John; she is my cousin; she is altogether lovely," I cried, with enthusiasm, "and so is Uncle Paul; he is a missionary out here at Chen-si."

"A missionary—and at Chen-si—then God help him!"

He said the last under his breath, but I heard him.

"Oh, Mr. Crawford," I cried, earnestly, for I love Uncle Paul dearly, "you do not think he is in danger?"

"I should think he probably left, Miss Nina, before the troubles began, and you know," reassuringly, "'Ill news flies apace,' so that, as you have heard nothing to the contrary, you may take it for granted he is all right."

We had got to the end of our walk now, but he opened the gate for me, and still lingered.

"I want to know that you are quite safe," he said, smiling. "You see what a gaoler I am. Ah, there is Mrs. Ross."

I ran to her and kissed her joyfully.

"Nina, darling, how delightful; come to spend a long day with me, I hope?"

"I should like to," I replied, "if Mr. Crawford will let father know."

"Your obedient slave, Miss Nina; I will be sure to acquaint the Colonel, and now I must be going."

"Won't you come in, Mr. Crawford?" said Mrs. Ross.

"I fear I cannot," he replied. "I have to report myself at headquarters. I was on guard last night."

"Any fresh news?" asked Mrs. Ross.

"Nothing but the usual story of the last few days. They have been firing a lot more houses, and the visions and apparitions are as numerous as ever."

"And the Red Hand?" asked Mrs. Ross, shuddering.

"Oh, we have got quite accustomed to it by this time," he replied.

He spoke lightly to reassure us, but it was easy to detect a vein of apprehensiveness behind his light tone.

Mrs. Ross looked pensive, and this pensive look added to her beauty and made her entrancing.

"Well, Nina," she said, when we were alone, "what would you like to do this morning?"

"Anything you like, darling," I replied, eagerly. "I am so tired of doing nothing and sitting in all day. I know what I should like," I cried, excitedly; "I should like to go into the park."

"The park?" said Mrs. Ross, turning her liquid gaze to the window. "Yes, it looks inviting this morning. I wonder if we could. I fear George would not like it—he can't bear me to leave the house; but, really, everything seems very quiet this morning, I don't see why we shouldn't go a little way. One does get so tired, as you say, of sitting in the house. It seems strange," she added, smiling, "the park being such an excitement to us. It was positively none when we could go any day, but 'Circumstances alter cases,' to quote a very trite proverb, and I fear you and I, Nina, are very human, and share the universal longing for what is out of reach."

"Yes. Do you know," I replied, laughing, "father never will forbid me anything, because he says he knows I should want to do it immediately?"

"What a character you are giving yourself," smiling. "At any rate you are true; and, if you loved, you would be easily guided."

"Yes, that is it," I cried. "I would do anything for love's sake; I love father, and so I would not hurt him for the world; his wishes are my law."

"Do you know," said Mrs. Ross, turning her lovely eyes on me with a new expression in their depths, "without meaning it, you have exactly described the relationship which exists between the renewed soul and the Father? I shall never forget that sermon your uncle preached on that subject. 'And because ye are sons, God has sent forth the Spirit of His Son into your hearts, crying, Abba, Father.' I don't know what makes me tell you this, but I have never felt the same since that day."

"No one ever does feel the same after meeting Uncle Paul; but the worst of it is I get so naughty again when I am away from him."

"So very, very naughty," she said, playfully, "and this is one of your wicked deeds I fear, and I am aiding and abetting you."

"You darling," I said, fondly, locking my arms in hers, "I don't know what I should have done in this place without you; and what a nice morning this is, and how pleasant it is here under the trees."

"Yes, but we had better keep the house in view; you see I have the caution which comes with age!"

And so we strolled on under the trees, and forgot our troubles for one short morning. The air seemed deliciously sweet and fresh, though, a few days later, it grew unbearably hot. We were just thinking of returning to the house when in the distance I saw a curious object on the ground; it lay under the trees about 200 yards away, and nothing would content me but that I must go and find out what it was. In vain Mrs. Ross expostulated, and pointed out the danger of going so far and getting out of touch with the houses; the spirit of mischief prompted me, and I ran away laughing. Lilian followed, entreating me to stop, but, I am sorry to say, the more excited she grew the more I laughed and the faster I ran—on and on, until I got quite close to the object which had excited my curiosity. Judge of my horror when, on looking down, I found it was one of our own soldiers lying there, dead; he had evidently been murdered by the Boxers.

I felt sobered in a moment. The beauty of the day had gone, and the sun seemed cruel now, as it blazed pitilessly down on the man's white, upturned face. I recognized him at once, for he had been for years in my father's regiment, and was a great favourite with us all.

And now he lay there in the bright sunshine, dead. I knelt by his side, quite forgetting the danger we were in, until Lilian Ross came up and almost dragged me away.

"Nina," she said, "you must be mad; come back with me this instant. We are out of sight of home, and any moment we may be stopped."

I rose sobbing, and quite subdued now, prepared to follow her quietly, feeling indifferent to everything. It was too late. As we retraced our steps, we heard wild shouting and cries, that awful cry that woke the stillness of the night—"Kill, kill."

Lilian turned as white as snow. I realized that it was through my rashness; we were probably doomed to a cruel death. I felt it keenly, because I saw that I had sacrificed Lilian as well as myself, but she never reproached me.

"Nina," she whispered, hurriedly, "have you got your satchet with you?"

The fear in her lovely eyes was reflected, I know, in mine.

"Yes," I said, fumbling with my hand in the bosom of my dress, "it is here."

"That is right, we may need it. I do not fear death, not since I met Mr. St. John; but torture—" and she shuddered.

"Oh, Lilian, and I have brought you to this. I shall never forgive myself—never."

"You did not mean it, darling."

"No, but it comes to the same thing."

"It may be possible for us to escape, even now; let us take this turn, Nina, it will lead us round by the other entrance."

The horrid sounds were coming nearer—we turned to flee, but it was too late. They caught a glimpse of us as we disappeared, and with wild, horrible cries they came rushing after us. A sensation of cruel fear—the knowledge that certain death stared us in the face—a quick review, as in a mirror, of all my past life—an agonized prayer for help, a sickening sensation of pain—and then a blank. And then——

CHAPTER VIII.

TAKEN PRISONER.

I was in a vast hall, and Lilian Ross stood by my side. How we got there I did not know, I only knew that we were there and still alive, that death was yet to come. At the other end of the hall, upon a kind of red dais, stood a man. I suppose he was a man, but he appeared to me to be more like a personation of the evil one, he had such a cruel, wicked face; and, as he sat glowering there, he looked as if he would like to devour us, so great was his hatred and wrath. One or two men were near him, but, for the most part, they stood in a vast circle, leaving a clear space in the centre for us, and, as they glared at us, they brandished their spears and shrieked for our blood. They seemed more like wild beasts than men. Then one who stood near the throne began to gesticulate, and brandish his horrid, blood-stained spear, but the man on the raised dais smiled. His smile was worse than the other's fury, and then he said a few words. I could not understand it all, but I knew enough of Chinese to guess that we were to die a lingering death of agony. The implements of torture were all round us, and these men thirsted for our blood; indeed, they seemed to be mad with the lust for blood; but there were preliminaries to be gone through; they would not touch us until they had performed their horrid ceremonies. Waving their hands and brandishing their spears, they seemed to be mingling in some kind of weird dance.

In the centre was a blood-stained stone, and, as they sang, they bowed down until their spears touched this stone. They seemed by these terrible orgies to be working themselves up to a still greater pitch of fury. Every moment I expected to be our last, for it seemed as if they would not be able much longer to restrain themselves, but would tear us to pieces in their fury.

I closed my eyes and shuddered. We clung to each other and tried to pray. Then I found out that they were speaking to us. I could not understand all that they said, but I understood enough to know that they wished us to abjure our religion. We were to deny Christ, and fall down and worship their horrible idols. If we did this, they promised us our lives. It was a deadly temptation. Lilian thought of her husband, and I thought of father; and we were young, and life was sweet, and it was so horrible to die without saying good-bye to anyone. Perhaps people in England will wonder and blame us that it was a temptation to us at all, but I heard Uncle Paul say once that temptation was not sin: that it only becomes sin when we yield. They say that times of great persecution are times of decision, too. I had not cared much for Christ in the old days; I had not been like Uncle Paul or Cicely—I had been careless and thoughtless; but now, with a cruel death staring me in the face, now, I chose Him. I turned to Lilian. "Christ for me," I said, in reply to her questioning look, and all my heart seemed on fire and my soul to be full of love. Lilian had made the choice also—I read the answer on her face before she spoke. Terribly frightened as I was, I gazed at her in the keenest admiration; her beautiful hair had become loosened, and now fell over her shoulders in a mass of gold; her lovely starlight eyes, pure and steadfast as those of any pictured saint, were fixed on our persecutors.

"Nina," she said to me in a whisper, "I do not know whether they would allow us to take that poison, but even if it were possible I think it would be better not to do so. We are in God's hands, and they cannot touch a hair of our heads until He gives them permission."

"Yes," I replied, "I agree with you—it's difficult, of course, to know if a thing is right or wrong now, but Uncle Paul would not have done it. I will follow him."

They seemed to be making some horrid preparations at the other end of the room—our time had come; we felt that and prepared to die. It's all very well to read about these things in a story, but unless you have passed through it yourself, you can have no idea of the horror and fear and deadly anticipation of coming woe which we felt. I was positively sick with terror, but I also felt full of an overwhelming love—I knew that Christ was worth all and more than all.

I whispered to Lilian that it would soon be over, and a text came running into my mind, "Our light affliction which is but for a moment, worketh for us a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory."

They seemed to have completed their preparations now, and came toward us with horrid cries.

"Oh, Lilian, do pray that we may be kept."

"Yes, yes, darling, it will soon be over, and then the glory."

I just remember that—I know they seized us; they tore us away from each other. And then I can recall nothing but some awful place of pain—a place of confusion and horrible noise and terrible suffering and then a blank, which seemed to last for years and years—then Lilian's voice, very faint, very far away—then a little nearer, a little louder.

"Are you better, darling?"

"Yes" (my voice was so weak, I could hardly hear it myself), "have I been ill?"

"Very, very ill, but you are better now, thank God, thank God."

"Where are we, Lilian?"

"In a kind of a cave at the back of a house."

"But how did we get here, I want to know all about it."

"I wonder if you are strong enough to hear more now?"

"Yes, yes," I cried, feverishly; "it will make me much worse not to know."

"Well," she replied, soothingly, "I think it would, and you must not agitate yourself. Now I will give you a cooling draught, and then you must lie quite still, and I will tell you everything."

"You won't hide anything, will you? I want to know what happened after that dreadful torture," and I shuddered.

"You were not tortured, darling; what their intentions were I do not know. I think they did mean to put us to a cruel death, but God is over all and prevented it."

"But why have I been ill then, Lilian? I am sure I could not have fancied it all."

"My poor darling, you had a dreadful blow—they pushed us so violently apart that you fell with your head against that platform; it was a horrid cut, but it is healing up nicely now."

"Then what happened?"

"Well, the sight of your blood, instead of calling forth their compassion, only seemed to infuriate them, and as I knelt beside you and tried to staunch the blood, I thought all was lost; but just at that moment a wonderful thing happened: I heard a great noise at the far end of the hall—two men had entered, and one of them was violently gesticulating. It appears that enormous rewards have been promised for our discovery, and this man had undertaken to find us. I could not make out what they said, but, no doubt, you would have been able to do so. The other man, who was scholarly and refined-looking, and altogether of a different type, seemed for some reason or other to have great influence with them. He did not say much, but when he did speak they listened, and gradually they ceased to brandish their spears, and after what seemed an eternity to me, I saw that they had given up the idea of murdering us, at any rate for the present. What arguments these men used, of course, I do not know, but anything like the expression of concentrated disappointment and rage on the faces of those who would have killed us, I have never seen. It makes me shudder to think of it now. An order was then given, and we, or rather, I was marched off, for you, poor darling, were past marching or doing anything. The two strange men picked you up, not un-gently, and we moved off; it seemed to me along, long way. Then there was another altercation, but at last it was decided that we should be taken to this house, and here we have been ever since. These two men guard us; if you look through the room opening out of this into the courtyard, you will see one of them standing there now. I do not know what their intentions are, but I conclude they are friendly—at any rate, we have not been molested by the Boxers since that terrible morning; and they have been kind and attentive in bringing us food; and once, when you were very ill, they brought a Chinese doctor to see you. I think we must either be outside or else very near the walls of the city; at any rate, it's a long, long way from the Legation. Now that you are better and can speak you will be able to talk to them; my great difficulty has been that understanding the language so little I have not been able to converse with them at all."

CHAPTER IX.

A DISCOVERY.

"See," I said, "he is looking our way. I should like to speak to him."

"But, dear child, are you strong enough?"

"Yes, yes," I cried, feverishly. "Do ask him, Lilian, to come here."

Lilian beckoned to him, and he came and stood in the doorway—a tall, imposing-looking figure, with an air of dignity about his dark, intellectual face.

I had talked to him only a few moments when I uttered an exclamation of delight.

Lilian looked at me a little apprehensively, and, catching sight of my face in the mirror opposite, I saw that it was flushed, and that my eyes burnt like diamonds.

"Darling," Mrs. Ross whispered, soothingly, "I fear this will be too much for you."

"Oh, no," I cried, excitedly. "It is joy, Lilian, joy. This man comes straight from Chen-si, from Uncle Paul; he is a convert, and will be baptized soon."

Lilian looked radiant.

"How wonderful it all is!" she said, softly. "How the Lord has overshadowed us! I cannot the least grasp it yet, but no doubt you will find out all about it."

"Yes, just fancy, Lilian; it's Mr. Li. Cicely has so often mentioned him in her letters, he is such a clever man, and used to come to read with Uncle Paul; but I did not know that he had become a Christian."

"I arrived in Pekin," Mr. Li was saying to me, "the very day you were captured. I had some knowledge of the man Wang—indeed, I was able to benefit him once—and he is attached to me in his way, but we must not depend upon him. I fear he is wholly influenced by mercenary motives; it will not be wise to address me when he is here, and I need hardly tell you that he has not the smallest suspicion that I have any knowledge of you. He wants the reward which has been offered; he met me as I was making my way into the city, and, knowing that I had some influence with the soldiers, he asked me to go with him to see if it were possible to save you. Thank God, we arrived at the Hall just in time."

"Thank God," we both said, or, rather, we almost breathed it from the depths of our being.

A moment's silence followed.

"Does my father know that we are safe?" I asked, anxiously.

"Yes," said Mr. Li, soothingly, "and your husband also," and for the first time he turned his grave gaze on Lilian. "And there was another, too, a young man, very young; when he heard that you were prisoners, he begged the Colonel to let him go at once; he said he had the strength of ten men, and that he would fight his way to you or die."

I did not say a word. I turned my head and remained silent, but I saw a young, bronzed face, and a pair of steadfast, blue eyes, that had never been shadowed by fear or indecision.

"Of course, it would have been madness," Mr. Li went on, calmly, "if would simply have meant death to everyone concerned. The Colonel saw that at a glance, as the Legations are fast closed now, and every man is wanted to defend them. Your only hope of deliverance lies in stratagem. This man carried news to the Colonel to-day, and will probably bring you a message, but I have plans," said Mr. Li. "I do not see the least use in returning to Pekin, there is only danger there; on the contrary, I should advise escape."

"Yes," we both said, "if only that were possible, but how?"

"I will tell you," he replied, and, as he spoke, the ghost of a smile lighted up his dark face, "there is a gentleman without the gates whom you both know; he has been making his way from Wei-hai-wei, whither he has conducted his wife and children in safety."

"Uncle Paul?" I cried. "Is he here? Why did he come?"

"He came because he knew you were at Pekin, and guessed you might want him."

"It is just like him; oh, I do hope he is not in danger."

"Rest assured," he replied, gently, "he is in God's hands, and he is doing what is right. He runs less risk than an ordinary foreigner, as he is a doctor as well as a missionary. I think the rioters at Chen-si could hardly have been aware of this fact when they attacked him."

"God keep him safe," we both murmured fervently.

"Amen," said Mr. Li. "How wonderfully God has worked hitherto. I arrived at Pekin the very day I could be of service to you. I knew that Mr. St. John was coming on here, and I have held communication with him already."

"How can he help us?" asked Mrs. Ross.

"In this way," he replied. "You cannot get into the Legation, it is fast closed, and help cannot come from there, for even if it were possible for a man to escape, he would be murdered when he set his foot outside the walls."—Mr. Li little knew of the strength, and courage, and determination of which Englishmen are capable.—"Hope lies in another direction altogether; from this house there are secret passages which lead out of Pekin; the Boxers know nothing of them, for," he added, with a touch of pardonable pride, "they were devised with great care, and were the work of many years."