From the Chandos Portrait

Note: Links to MIDI sound files may not work on some devices.

OF no other author, perhaps, has more been written than of Shakespeare. Yet whatever other knowledge his commentators professed, few of them appear to have been naturalists, and none, so far as I am aware, have examined his knowledge of Ornithology.

An inquiry upon this subject, undertaken in the first instance for my own amusement, has resulted in the bringing together of so much that is curious and entertaining, that to the long list of books already published about Shakespeare, I have been bold enough to add yet another. In so doing, I venture to hope that the reader may so far appreciate the result of my labour as not to consider it superfluous.

As regards the treatment of the subject, a word or two of explanation seems necessary. In 1866, from the notes I had then collected, I contributed a series of articles on the birds of Shakespeare to The Zoologist. In these articles, I referred only to such birds as have a claim to be considered British, and omitted all notice of domesticated species. I had not then considered any special arrangement or grouping, but noticed each species seriatim in the order adopted by Mr. Yarrell in his excellent “History of British Birds.” Since that date, I have collected so much additional information on the subject, that, instead of eighty pages (the extent of my first publication), three hundred have now passed through the printers’ hands. With this large accession of material, it was found absolutely necessary to re-arrange and re-write the whole. The birds therefore have been now divided into certain natural groups, including the foreign and domesticated species, to each of which groups a chapter has been devoted; and I have thought it desirable to give, by way of introduction, a sketch of Shakespeare’s general knowledge of natural history and acquaintance with field-sports, as bearing more or less directly on his special knowledge of Ornithology, which I propose chiefly to consider.

After I had published the last of the series of articles referred to, I received an intimation for the first time, that, twenty years previously, a notice of the birds of Shakespeare had appeared in the pages of The Zoologist. I lost no time in procuring the particular number which contained the article, and found that, in December, 1846, Mr. T. W. Barlow, of Holmes Chapel, Cheshire, had, to a certain extent, directed attention to Shakespeare’s knowledge as an Ornithologist. His communication, however, did not exceed half a dozen pages, in which space he has mentioned barely one-fourth of the species to which Shakespeare has referred. From the cursory nature of his remarks, moreover, I failed to discover a reference to any point which I had not already investigated. It would be unnecessary for me, therefore, to allude to this article, except for the purpose of acknowledging that Mr. Barlow was the first to enter upon what, as regards Shakespeare, may be termed this new field of research.

The labour of collecting and arranging Shakespeare’s numerous allusions to birds, has been much greater than many would suppose, for not only have I derived little or no benefit from the various editions of his works which I have consulted, but reference to a glossarial index, or concordance, has, in nine cases out of ten, resulted in disappointment. It is due to Mr. Staunton, however, to state that I have found some of the foot-notes to his library edition of the Plays very useful.

Although oft-times difficult, it has been my endeavour, as far as practicable, to connect one with another the various passages quoted or referred to, so as to render the whole as readable and as entertaining as possible. With this view, many allusions have been passed over as being too trivial to deserve separate notice, but a reference to them will be found in the Appendix at the end of the volume,1 where all the words quoted are arranged, for convenience, in the order in which they occur in the plays and poems.

In spelling Shakespeare’s name, I have adopted the orthography of his friends Ben Jonson and the editors of the first folio.2

As regards the illustrations, it seems desirable also to say a few words.

In selecting for my frontispiece a portrait of Shakespeare as a falconer (a character which I am confident could not have been foreign to him), I have experienced considerable difficulty in making choice of a likeness.

Those who have made special inquiries into the authenticity of the various portraits of Shakespeare, are not agreed in the results at which they have arrived. This is to be attributed to the fact that, with the exception of the Droeshout etching, to which I shall presently state my objection, no likeness really exists of which a reliable history can be given without one or more missing links in the chain of evidence.

There are four portraits which have all more or less claim to be considered authentic. These are “the Jansen portrait,” 1610; “the Stratford bust,” prior to 1623; “the Droeshout etching,” 1623; and “the Chandos portrait,” of which the precise date is uncertain, but which must have been painted some years prior to 1616, the year of Shakespeare’s death.

It would be impossible, within the compass of this preface, to review all that has been said for and against these four portraits. Neither will space permit me to give the history of each in detail. I can only briefly allude to the chief facts in connection with each, and state the reasons which have influenced me in selecting the Chandos portrait.

Mr. Boaden, who was the first to examine into the authenticity of reputed Shakespeare portraits,3 has evinced a preference for the so-called “Jansen portrait,” in the collection of the Duke of Somerset, considering it to have been painted by Cornelius Jansen, in 1610, for Lord Southampton, the great patron, at that date, of art and the drama.

The picture, indeed, bears upon the face of it an inscription—

Æte 46

1610

—which gives much weight to the views

expressed by Mr. Boaden.

It is certain that, in the year mentioned, Jansen was in England, and that he painted several pictures for Lord Southampton; it is equally true, that at that date Shakespeare was in his forty-sixth year. But Mr. Boaden fails to prove that this particular picture was painted by Jansen, and that it was ever in the possession of Lord Southampton, or painted by his order.

As a fine head, and a work of art, it is the one of all others that I should like to think resembled Shakespeare, could its history be more satisfactorily detailed.

Many regard as a genuine portrait, the Bust at Stratford-on-Avon, which is stated to have been executed by Gerard Johnson, and “probably” under the superintendence of Dr. John Hall. The precise date of its erection is not known, but we gather that it was previous to 1623, from the fact that Leonard Digges has referred to it in his Lines to the Memory of Shakespeare, prefixed to the first folio edition of the Plays published in that year. Mr. Wivell relies very strongly on the circumstance of its having been originally coloured to nature.4 Hence tradition informs us that the eyes were hazel, the hair and beard auburn. It must be admitted, however, that a portrait after death can never be so faithful as a picture from the life, while no sculptor who examines this bust can maintain that it was executed from a cast.5

Those who approve of the Droeshout etching, published in 1623, as a frontispiece to the first folio, find a strong argument in favour of its being a likeness in the commendatory lines by Ben Jonson, which accompany it. Jonson knew Shakespeare well, and he says of this picture:—

As a work of art it is by no means skilful, and is confessedly inferior not only to other engravings of that day, but also to other portraits by Martin Droeshout.

That it bore some likeness to Shakespeare as an actor, I do not doubt, but that it resembled him as a private individual when off the stage, I cannot bring myself to believe. The straight hair and shaven chin which are not found in other portraits having good claims to be considered authentic, and the unnaturally high forehead, which would be caused by the actor’s wearing the wig of an old man partially bald, suggest at once that when the original portrait was taken, from which Droeshout engraved, Shakespeare was dressed as if about to sustain a part in which he was thought to excel as an actor.

Boaden has conjectured that this portrait represents Shakespeare in the character of old Knowell, in Ben Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour, a part which he is known to have played in 1598, and this would easily account for Ben Jonson’s commendation.6 This conjecture is so extremely probable, that I have no hesitation in endorsing it.

We come, then, now to “the Chandos portrait.” With the longest pedigree of any, it possesses at least as much collateral evidence of probability, and is, moreover, important as belonging to the nation.7 It has been traced back to the possession of Shakespeare’s godson, William, afterwards Sir William, Davenant, and all that seems to be wanting materially, is the artist’s name. The general opinion is, that it was painted either by Burbage or Taylor, both of whom were fellow-players of Shakespeare. It is styled the Chandos portrait from having come to the trustees of the National Portrait Gallery from the collection of the Duke of Chandos and Buckingham, through the Earl of Ellesmere, by whom it was purchased and presented. The history of the picture, so far as it can be ascertained, is as follows:—

It was originally the property of Taylor, the player (our poet’s Hamlet), by whom, or by Richard Burbage, it was painted.8

Taylor dying about the year 1653, at the advanced age of seventy,9 left this picture by will to Davenant.10 At the death of Davenant, who died intestate in 1663, it was bought, probably at a sale of his effects, by Betterton, the actor.

While in Betterton’s possession, it was engraved by Van der Gucht, for Rowe’s edition of Shakespeare, in 1709. Betterton dying without a will and in needy circumstances, his pictures were sold. Some were bought by Bullfinch, the printseller, who sold them again to a Mr. Sykes. The portrait of Shakespeare was purchased by Mrs. Barry, the actress, who afterwards sold it for forty guineas to Mr. Robert Keck, of the Inner Temple.

While in his possession, an engraving was made from it, in 1719, by Vertue, and it then passed to Mr. Nicholls, of Southgate, Middlesex, who acquired it on marrying the heiress of the Keck family.

The Marquis of Caernarvon, afterwards Duke of Chandos, marrying the daughter of Mr. Nicholls, it then became his Grace’s property. When his pictures were sold at Stowe, in September, 1848, this portrait was purchased for three hundred and fifty-five guineas by the Earl of Ellesmere, who, in March, 1856, presented it to the Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery, in whose hands it still remains.

Notwithstanding this pedigree, the picture has been objected to on the ground that the dark hair and foreign complexion could never have belonged to our essentially English Shakespeare. Those who make this objection, seem to forget entirely the age of the portrait, and the fact that it is painted in oil and on canvas, a circumstance which of itself is quite sufficient, after the lapse of two centuries and a half, to account for the dark tone which now pervades it, to say nothing of the numerous touches and retouches to which it has been subjected at the hands of its various owners.

Notwithstanding the missing links of evidence, it seems to me that, having traced the picture back to the possession of Shakespeare’s godson, we have gone far enough to justify us in accepting it as an authentic portrait in preference to many others. For we cannot suppose that Sir William Davenant would retain in his possession until his death a picture of one with whom he was personally acquainted, unless he considered that it was sufficiently faithful as a likeness to remind him of the original.

On the score of pedigree, then, and because I believe that the only well-authenticated portrait (i.e., the Droeshout) represents Shakespeare as an actor, and not as a private individual, I have selected the Chandos portrait for my frontispiece.

By obtaining a reduced photograph of this upon wood, from the best engraving, and “vignetting” it, I have been enabled to place upon the left hand a hooded falcon, drawn by the unrivalled pencil of Mr. Wolf, and thus to entrust to the engraver, Mr. Pearson, a faithful likeness of man and bird.

As regards the other illustrations, my acknowledgments are due to Mr. J. G. Keulemans for the artistic manner in which he has executed my designs, and to Mr. Pearson for the careful way in which he has engraved them.

With these observations, I conclude an undertaking which has occupied my leisure hours for six years, but which indeed has been, in every sense of the word, “a labour of love.”

Should the reader, on closing this volume, consider its design but imperfectly executed, it is hoped that he will still have gleaned from it enough curious information to compensate him for the disappointment.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION. SHAKESPEARE’S GENERAL KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL HISTORY. |

|

|---|---|

| His Love of Sport.—Hawking.—Fishing.—Hunting.—Fowling.—Deer-Shooting.—Deer-Stealing.—“The Subtle Fox” and “Timorous Hare.”—Coursing.—Coney-Catching.—Wild Animals mentioned by Shakespeare.—His Knowledge of their Habits.—Insects referred to in the Plays.—Shakespeare’s Powers of Observation.—Practical Knowledge of Falconry.—Love of Birds. | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. THE EAGLE AND LARGER BIRDS OF PREY. |

|

| An “Eagle Eye.”—Power of Flight.—A good Omen.—“The Bird of Jove.”—The Roman Eagle.—The “Ensign” of the Eagle.—Habits and Attitudes.—Eagles’ Eggs.—Longevity of the Eagle: its Age computed.—The Eagle trained for Hawking.—The Vulture: its Repulsive Habits.—The Osprey: its Power over Fish.—The Kite.—The Kite’s Nest.—The Buzzard. | 23 |

| CHAPTER II. HAWKS AND HAWKING. |

|

| Explanation of Hawking Terms.—The Falcon and Tiercel.—The Qualities of a good Falconer.—The “Lure” and its Use.—The “Quarry”—The Hawk’s “Trappings.”—Jesses, Bells, and Hood.—An Unmann’d Hawk.—The Cadge—The Hawks Mew.—The Royal Mews.—Origin of the word “Mews.”—Imping.—How to “Seel” a Hawk.—A Hawk for the Bush.—Going “a-birding.”—The “Stanniel” or Kestrel.—Origin of the Two Names.—The “Musket” or Sparrow-Hawk.—Hawk and Hernshaw.—Prices of Hawks.—Hawk’s Furniture.—Hawk’s Meat.—Falconer’s Wages.—Sundries. | 49 |

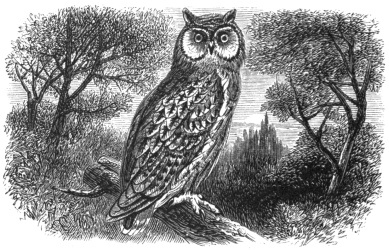

| CHAPTER III. THE OWL AND ITS ASSOCIATIONS. |

|

| “The Bird of Juno.”—“The Favourite of Minerva.”—“The Bird of Wisdom.”—Sacred to Proserpine.—Use in Medicine.—The Bird of Ill-Omen.—Its Appearance by Day.—Its Habits misunderstood.—Its Utility to the Farmer.—A Curious Tradition.—Its Note or Cry.—An Owl Robbing Nests.—Evidence not conclusive.—Its Retiring Habits.—Its “Five Wits.”—Its Fame in Song.—The Owl’s Good Night. | 83 |

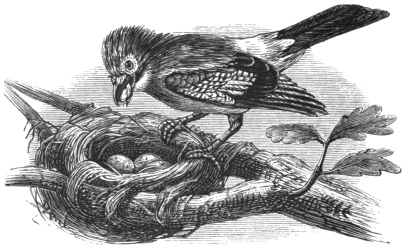

| CHAPTER IV. THE CROWS AND THEIR RELATIONS. |

|

| The Raven: a Bird of Ill Omen.—Its Supposed Prophetic Power.—Its Deep and Solemn Voice.—The Raven’s Croak foreboding Death.—The “Night-Raven” and “Night-Crow.”—The Raven’s Presence on Battlefields.—Its alleged Desertion of its Young.—The Rook and Crow.—The Crow-Keeper, and “Scare-Crow.”—The Chough.—Russet-pated Choughs.—The Daw, Magpie, and Jay. | 99 |

| CHAPTER V. THE BIRDS OF SONG. |

|

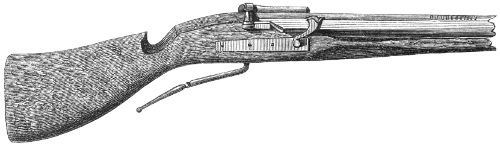

| The Nightingale.—“Lamenting Philomel.”—Singing against a Thorn.—Erroneously supposed to Sing only by Night.—“Recording.”—The Lark.—“The Herald of the Morn.”—Singing at Heaven’s Gate.—Song of the Lark.—Soaring and Singing.—Changing Eyes with Toad.—Lark-Catching.—The Common Bunting.—“The Throstle, with his Note so True.”—Imitation of his Song.—The Ouzel-Cock.—The Robin-Redbreast, or Ruddock.—Covering the Dead with Leaves.—“Redbreast Teacher.”—“The Wren with Little Quill.”—Its Loud Song.—The Sparrow.—“Philip Sparrow.”—Providence in the Fall of a Sparrow.—The Hedge-Sparrow and Cuckoo.—“The Cuckoo’s Bird.”—“Ungentle Gull.”—“The Plain Song Cuckoo Gray.”—The Song of the Cuckoo.—Cuckoo Songs.—The Wagtail, or Dishwasher.—Bird-catching.—Springes.—Gins.—Bat-fowling.—Its Two Significations.—Bird-Lime, Bird-Bolts, and Birding-Pieces. | 123 |

| CHAPTER VI. THE BIRDS UNDER DOMESTICATION. |

|

| Cock.—“Cock-Crow.”—“Cock-shut-time.”—“Cock-a-Hoop.”—“Cock and Pye.”—Cock-Fighting.—Ancestry of the Domestic Cock.—The Peacock.—Its Introduction into Europe, and Ancient Value.—In Request for the Table.—The Turkey.—Date of Introduction into England.—Shakespeare’s Anachronism.—Pigeons.—First used as Letter-Carriers.—A Present of Pigeons.—Meaning of “Pigeon-Liver’d.”—Pigeon-Post.—Mode of Feeding the Young.—The Barbary Pigeon.—The Rock-Dove.—Doves and Dovecotes.—The “Doves of Venus.”—“The Dove of Paphos.”—“As True as Turtle to her Mate:” “as Plantage to the Moon.”—Mahomet’s Dove.—A Dish of Doves.—The Goose.—“Green-Geese,” and “Stubble-Geese.”—“Cackling home to Camelot.”—“The Wild-Goose Chase.”—The Swan.—“The Bird of Apollo.”—Song of the Swan.—Habits of the Swan.—The Swan’s Nest.—As Soft as Swan’s-down.—“Juno’s Swans.”—Cygnets. | 167 |

| CHAPTER VII. THE GAME-BIRDS AND “QUARRY” FLOWN AT BY FALCONERS. |

|

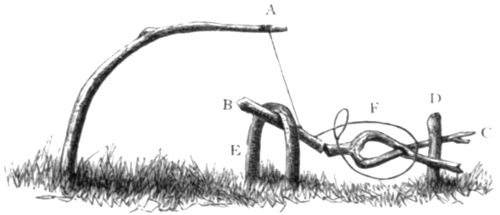

| Sporting in Shakespeare’s Day.—The Pheasant.—Date of its Introduction into Britain.—Ancient Value of Game.—Game-Preserving.—Game-Laws.—Partridge-Hawking.—Anecdote of Charles I.—Quails.—Quail-Fighting.—The Lapwing.—Feigning to be Wounded.—Running as soon as Hatched.—The Heron, or Hernshaw.—Heron-Hawking.—Hawk and Hernshaw—Heron at Table.—The Woodcock.—Springes for Woodcocks.—How to Make a Springe.—A Gin.—“The Woodcock’s Head.”—The Snipe. | 209 |

| CHAPTER VIII. WILD-FOWL AND SEA-FOWL. |

|

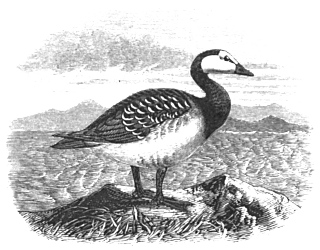

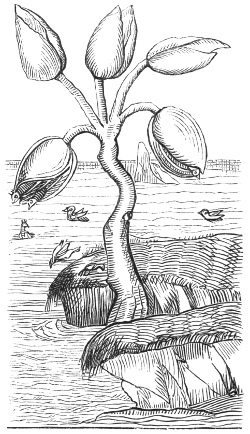

| “A Flight of Fowl.”—Habit of Wounded Birds.—“Duck-Hunting.”—Swimming “like a Duck.”—Wild-fowling in Shakespeare’s Day.—“The Stalking-Horse.”—“The Caliver.”—“The Stale.”—Wild-Geese.—Sign of Hard Weather.—The Barnacle Goose.—Barnacles.—Wild Fowl.—Divers and Grebes.—The “Loon.”—The “Di-dapper.”—The Cormorant.—Its Voracity.—Fishing with Cormorants.—The King’s Cormorants.—Their “Keep” at Westminster.—Fishing at Thetford.—The Master of the Cormorants.—Entries in State Papers.—The Home of the Cormorant.—The Sea-side.—Shakespeare’s Sea-cliffs and “Sea-mells.”—Gulls and Gull-Catchers. | 235 |

| CHAPTER IX. BIRDS NOT INCLUDED IN THE FOREGOING CHAPTERS. |

|

| The Parrot “clamorous against Rain.”—Talking like a Parrot.—A rare “Parrot-Teacher.”—The Popinjay.—The Starling.—Its Talking Powers.—The Kingfisher.—Halcyon Days.—Flight of the Kingfisher.—Estimated Speed.—The Swallow and “Martlet.”—The Swallow’s Herb and Swallow’s Stone.—The “Ostridge.”—“Eating Iron”—Bating with the Wind.—The Pelican.—Feeding its Young with its Blood.—Explanation of the Fable.—Former Existence of a Pelican in the English Fens.—Conclusion. | 271 |

| PAGE | |

| William Shakespeare, adapted from the Chandos Portrait by J. Wolf, engraved by G. Pearson | Frontis. |

| Deer-Shooting, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 1 |

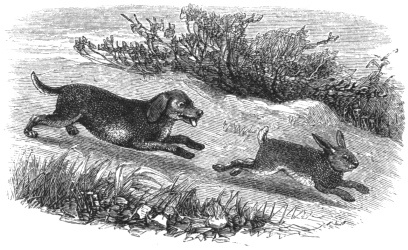

| Rabbit and Beagle, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 22 |

| Goshawk and Hare, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 23 |

| White-tailed Eagle in Trap, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 48 |

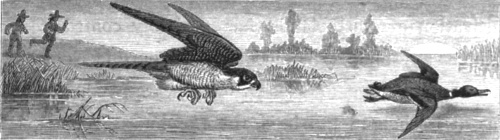

| Falcon and Wild Duck, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 49 |

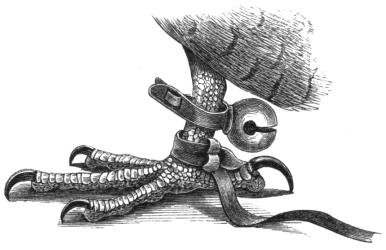

| The Jesses, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 58 |

| The Bells, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 60 |

| The Hood, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 61 |

| The Cadge, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 63 |

| Imping, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 68 |

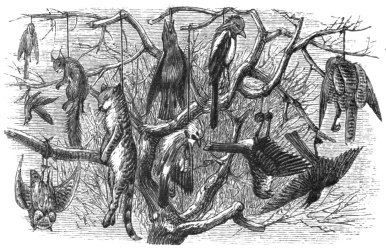

| The Keeper’s Tree, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 82 |

| Owl Mobbed by Small Birds, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 83 |

| Long-eared Owl, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 98 |

| Rooks and Magpies, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 99 |

| Jay Stealing Eggs, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 122 |

| Blackbird, Thrush, Nightingale, and Wren, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 123 |

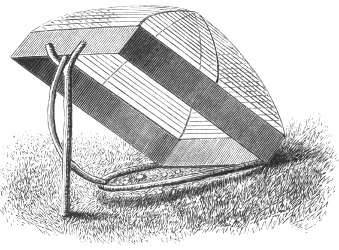

| Bird-Trap, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 162 |

| Birding-Piece of Prince Charles, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 165 |

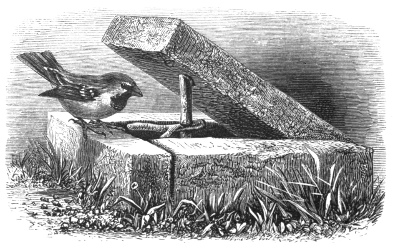

| Sparrow and Trap, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 166 |

| Turkey, Peacock, and Pigeon, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 167 |

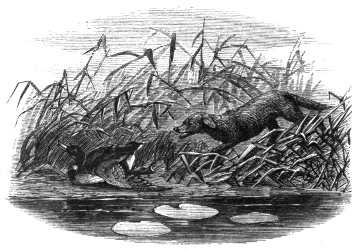

| Dog and Wounded Duck, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 208 |

| Pheasant and Partridges, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 209 |

| A Springe for Woodcocks, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 229 |

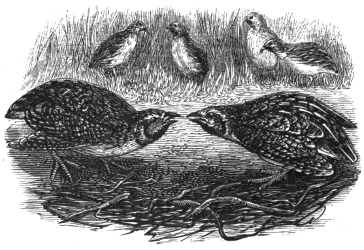

| Quails Fighting, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 234 |

| Wild-Fowl Alighting, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 235 |

| Caliver of the Sixteenth Century, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 242 |

| The Barnacle Goose, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 247 |

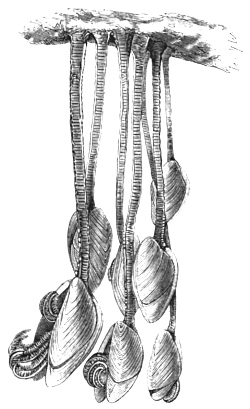

| The Barnacle Goose Tree. From Aldrovandus, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 248 |

| The Barnacle Goose Tree. From Gerard, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 250 |

| Barnacles. From Nature., drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 253 |

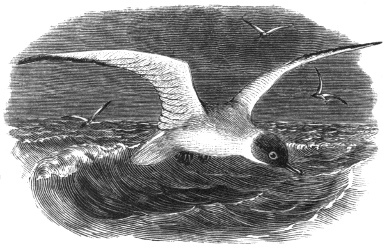

| Black-headed Gull, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 270 |

| Kingfisher and Swallows, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 271 |

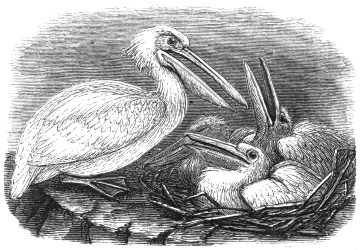

| Pelican and Young, drawn by J. G. Keulemans, engraved by G. Pearson | 298 |

BEFORE proceeding to examine the ornithology of Shakespeare, it may be well to take a glance at his knowledge of natural history in general.

Pope has expressed the opinion that whatever object of nature or branch of science Shakespeare either speaks of or describes, it is always with competent if not with exclusive knowledge. His descriptions are always exact, his metaphors appropriate, and remarkably drawn from the true nature and inherent qualities of each subject. There can indeed be little doubt that Shakespeare must have derived the greater portion of his knowledge of nature from his own observation, and no one can fail to be delighted with the variety and richness of the images which he has by this means produced.

Whether we accompany him to the woods and fields, midst “daisies pied and violets blue,” or sit with him “under the shade of melancholy boughs,” whether we follow him to “the brook that brawls along the wood,” or to that sea “whose rocky shore beats back the envious siege of watery Neptune,” we are alike instructed by his observations, and charmed with his apt descriptions. How often do the latter strike us as echoes of our own experience, sent forth in fitter tones than we could find.

A sportsman is oft-times more or less a naturalist. His rambles in search of game bring him in contact with creatures of such curious structure and habits, with insects and plants of such rare beauty, that the purpose of his walk is for the time forgotten, and he turns aside from sport, to admire and learn from nature.

That Shakespeare was both a sportsman and a naturalist, there is much evidence to show. During the age in which he lived “hawking” was much in vogue. Throughout the Plays, we find frequent allusions to this sport, and the accurate employment of terms used exclusively in falconry, as well as the beautiful metaphors derived therefrom, prove that our poet had much practical knowledge on the subject. We shall have occasion later to discuss his knowledge of falconry at greater length. It will suffice for the present to observe that there are many passages in the Plays which to one unacquainted with the habits of animals and birds, or ignorant of hawking phraseology, would be wholly unintelligible, but which are otherwise found to contain the most beautiful and forcible metaphors. As instances of this may be cited that passage in Othello (Act iii. Sc. 3), where the Moor compares his suspected wife to a “haggard falcon,” and the hawking scene in Act ii. of the Second Part of King Henry VI.11

Shakespeare, although a contemplative man, appears to have found but little “recreation” in fishing, and the most enthusiastic disciple of Izaak Walton would find it difficult to illustrate a work on angling with quotations from Shakespeare. He might refer us to Twelfth Night (Act ii. Sc. 5), where Maria, on the appearance of Malvolio, exclaims, “Here comes the trout that must be caught with tickling;” and to the song of Caliban in The Tempest (Act ii. Sc. 2), “No more dams I’ll make for fish.” Possibly, by straining a point or two, he might ask with Benedick, in Much Ado about Nothing (Act i. Sc. 1), “Do you play the flouting Jack?”

But our poet seems to have considered—

His forte lay more in hunting and fowling than in fishing,13 and in all that relates to deer-stalking (as practised in his day, when the deer was killed with cross-bow or bow and arrow), to deer-hunting with hounds, and to coursing, we find him fully informed.

In the less noble art of bird-catching14 he was probably no mean adept, while the knowledge which he displays of the habits of our wild animals, as the fox, the badger, the weasel, and the wild cat, could only have been acquired by one accustomed to much observation by flood and field.

On each of these subjects a chapter might be written, but it will suffice for our present purpose to draw attention only to some of the more remarkable passages in support of the assertions above made.

Deer-shooting was a favourite sport of both sexes in Shakespeare’s day, and to enable the ladies to enjoy it in safety, “stands,” or “standings,” were erected in many parks, and concealed with boughs. From these the ladies with bow and arrow, or cross-bow, shot at the deer as they were driven past them by the keepers.

Queen Elizabeth was extremely fond of this sport, and the nobility who entertained her in her different progresses, made large hunting parties, which she usually joined when the weather was favourable. She frequently amused herself in following the hounds. “Her Majesty,” says a courtier, writing to Sir Robert Sidney, “is well and excellently disposed to hunting, for every second day she is on horseback, and continues the sport long.”15 At this time Her Majesty had just entered the seventy-seventh year of her age, and was then at her palace at Oatlands. Often, when she was not disposed to hunt herself, she was entertained with a sight of the sport. At Cowdray Park, Sussex, then the seat of Lord Montagu (1591), Her Majesty one day after dinner saw “sixteen bucks, all having fayre lawe, pulled downe with greyhounds in a laund or lawn.”16

No wonder, then, that the ladies of England, with the royal example before their eyes, found such delight in the chase during the age of which we speak, and not content with being mere spectators, vied with each other in the skilful use of the bow.

To this pastime Shakespeare has made frequent allusion.

In Love’s Labour’s Lost, the first scene of the fourth act is laid in a park, where the Princess asks,—

To which the forester replies,—

And in Henry VI. Part III. Act iii. Sc. 1,—

Again, in Cymbeline (Act iii. Sc. 4), “When thou hast ta’en thy ‘stand,’ the elected deer before thee.” Other passages might be mentioned, but it will be sufficient to refer only to The Merry Wives of Windsor (Act v. Sc. 5), and to the song in As You Like It (Act iv. Sc. 2), commencing “What shall he have that kill’d the deer?”

Deer-stealing in Shakespeare’s day was regarded only as a youthful frolic. Antony Wood (“Athen. Oxon.” i. 371), speaking of Dr. John Thornborough, who was admitted a member of Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1570, at the age of eighteen, and who was successively Bishop of Limerick and Bishop of Bristol and Worcester, informs us, that he and his kinsman, Robert Pinkney, “seldom studied or gave themselves to their books, but spent their time in the fencing schools, and dancing schools, in stealing deer and conies, in hunting the hare and wooing girls.”

Shakespeare himself has been accused of this indiscretion. The story is first told in print by Rowe, in his “Life of Shakespeare”:—“He had, by a misfortune common enough to young fellows, fallen into ill company, and amongst them some that made a frequent practice of deer-stealing engaged him more than once in robbing a park that belonged to Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote, near Stratford. For this he was prosecuted by that gentleman, as he thought somewhat too severely; and in order to revenge that ill-usage, he made a ballad upon him. And though this, probably the first essay of his poetry, be lost, yet it is said to have been so very bitter, that it redoubled the prosecution against him to that degree, that he was obliged to leave his business and family in Warwickshire, for some time, and shelter himself in London.”

Mr. Staunton, in his library edition of Shakespeare’s Plays, says: “What degree of authenticity the story possesses will never probably be known. Rowe derived his version of it no doubt through Betterton; but Davies makes no allusion to the source from which he drew his information, and we are left to grope our way, so far as this important incident is concerned, mainly by the light of collateral circumstances. These, it must be admitted, serve in some respects to confirm the tradition. Shakespeare certainly quitted Stratford-upon-Avon when a young man, and it could have been no ordinary impulse which drove him to leave wife, children, friends, and occupation, to take up his abode among strangers in a distant place.

“Then there is the pasquinade, and the unmistakable identification of Sir Thomas Lucy as Justice Shallow, in the Second Part of Henry IV., and in the opening scene of The Merry Wives of Windsor. The genuineness of the former may be doubted; but the ridicule in the Plays betokens a latent hostility to the Lucy family, which is unaccountable, except upon the supposition that the deerstealing foray is founded on facts.”

The more legitimate sport in killing deer was by means of blood-hounds, and in The Midsummer Night’s Dream we are furnished with an accurate description of the dogs in most repute:—

In the Comedy of Errors (Act iv. Sc. 2), Dromio of Syracuse alludes to “a hound that runs counter, and yet draws dry foot well,” and in the Taming of the Shrew we have the following animated dialogue:—

Many more such instances might be adduced, but the reader might perhaps be tempted to exclaim, with Timon of Athens:—

We will therefore only glance at that amusing scene in the Merry Wives of Windsor (Act v. Sc. 5), where Falstaff appears in Windsor Forest, disguised with a buck’s head on. “Divide me,” says he, “like a brib’d-buck, each a haunch: I will keep my sides to myself, my shoulders for the fellow of this walk, and my horns I bequeath your husbands.”

We have here an allusion to the ancient method of “breaking up” a deer.18 “The fellow of this walk” is the forester, to whom it was customary on such occasions to present a shoulder. Dame Juliana Berners, in her “Boke of St. Albans,” 1496, says,—

And in Turbervile’s “Book of Hunting,” 1575, the distribution of the various parts of a deer is minutely described.

The touching description of a wounded stag, in As You Like It, can scarcely escape notice. Alluding to “the melancholy Jaques,” one of the lords says,—

Although the deer, as the nobler animal, has received more attention from our poet than the fox and the hare, yet the two last-named are by no means forgotten:—

who, when he “hath once got in his nose,” will “soon find means to make the body follow” (Henry VI. Part III. Act iv. Sc. 7); and—

receives his share of notice, although it is not always in his praise, and “subtle as the fox” has become a proverb (Cymbeline, Act iii. Sc. 3).

From the “subtle fox” to the “timorous hare,” the transition is easy. What “more a coward than a hare”? (Twelfth Night, Act iii. Sc. 5.)

In Roxburgh and Aberdeen, as we learn from Jamieson’s “Scottish Dictionary,” a hare is termed “a bawd,” and the knowledge of this fact enables us to understand the dialogue in Romeo and Juliet, which would otherwise be unintelligible:—

That coursing was in vogue in Shakespeare’s day, and practised in the same way as at present, we may infer from such expressions as “a good hare-finder” (Much Ado, Act i. Sc. 1), “Holla me like a hare” (Coriolanus, Act i. Sc. 8), and “I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips, straining upon the start” (Henry V. Act iii. Sc. 1).

Rabbits were taken, and no doubt poached, in the same way then as now; for we read of the coney19 “that you see dwell where she is kindled” (As You Like It, Act iii. Sc. 2) struggling “in the net.” (Henry VI. Part III. Act i. Sc. 4.)

The Brock20 or Badger (Twelfth Night, Act ii. Sc. 5); the Wild Cat who “sleeps by day” (Merch. of Venice, Act ii. Sc. 5, and Pericles, Act iii. Intro.); “the quarrelous Weasel” (Cymbeline, Act iii. Sc. 4, and Henry IV. Part I. Act ii. Sc. 3); “the Dormouse of little valour” (Twelfth Night, Act iii. Sc. 1); “the joiner Squirrel” (Romeo and Juliet, Act i. Sc. 4), whose habit of hoarding appears to have been well known to Shakespeare (Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act iv. Sc. 2); and “the blind Mole,” who “casts copp’d hills towards heaven” (Pericles, Act i. Sc. 1);21—all these are mentioned in their turn, while the Bat “with leathern wing,”22 “the venom Toad,” “the thorny Hedgehog,”23 “the Adder blue,” and the “spotted Snake with double tongue,” are all called in most aptly by way of simile or metaphor.

We cannot forget Titania’s directions to her fairies in regard to Bats:—

nor the comfortable seat which Ariel appears to have found “on the bat’s back” (Tempest, Act v. Sc. 1).

The following striking passage must also be familiar to readers of Shakespeare:—

In a printed broadside of the time of Queen Anne, in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries of London, is the following curious fable relating to the Bat:—

“615. The Birds and Beasts. A Fable.“Once the Birds and Beasts strove for the prerogative: the neuter Batt, seeing the Beasts prevail, goes to them and shows them her large forehead, long ears, and teeth: afterwards, when the Birds prevail’d, the Batt flies with the Birds, and sings chit, chit, chat, and shows them her wings.

“Hence Beakless Bird, hence Winged Beast, they cry’d;Hence plumeless wings; thus scorn her either side.“London. Printed for Edw. Lewis,

Flower-de-Luce Court, Fleet Street. 1710.”

In alluding to the “venom toad” as “mark’d by the destinies to be avoided,” Shakespeare probably only treated it as other writers had done before him, and, without any personal investigation of the matter, ranked it with the viper and other poisonous reptiles, when in fact it is perfectly harmless.

The habit which the snake has, in common with other reptiles, of periodically casting its skin or slough, is frequently alluded to in the Plays, where that covering is sometimes called “the enamell’d skin” (Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act ii. Sc. 1); at other times the “casted slough” (Henry V. Act iv. Sc. 1, and Twelfth Night, Act iii. Sc. 4); and the “shining checker’d slough” (Henry VI. Part II. Act iii. Sc. 1).

It is difficult to say why the Adder is supposed to be deaf, unless because it has no visible ears—but then the term would apply to other reptiles. Shakespeare has several times alluded to this. In the Second Part of King Henry VI. Act iii. Sc. 2, Queen Margaret asks the King,—

And in Troilus and Cressida, Act ii. Sc. 2, Hector says to Paris and Troilus,—

Again, in Sonnet CXII., “the adder’s sense” is referred to in such a way as to leave no doubt of the poet’s impression that adders do not hear.

The “eyeless venom’d worm” referred to in Timon of Athens, Act iv. Sc. 3, is of course the Slow-worm (Anguis fragilis).

The observant naturalist must doubtless have remarked the partiality evinced by snakes and other reptiles for basking in the sun. Shakespeare has noticed that—

And—

In Macbeth, Act iii. Sc. 2, allusion is made to the wonderful vitality which snakes possess, and to the popular notion that they are enabled, when cut in two, to reunite the dissevered portions and recover:—

Passing to the insect world, we may well be astonished at the number of species to which Shakespeare has alluded. Although the same attention has not been given to the insects as to the birds, the following have, nevertheless, been noted. Many others, doubtless, have been overlooked.

The Beetle (Macbeth, Act iii. Sc. 2; King Lear, Act iv. Sc. 6; Measure for Measure, Act iii. Sc. 1). The Grasshopper (Romeo and Juliet, Act i. Sc. 4). The Cricket, (Pericles, Act iii. Introduction; Winter’s Tale, Act ii. Sc. 1; Romeo and Juliet, Act i. Sc. 4; Cymbeline, Act ii. Sc. 2). The Glowworm (Hamlet, Act i. Sc. 5); and the Caterpillar (Richard II. Act ii. Sc. 4; Henry VI. Part II. Act iii. Sc. 1; Twelfth Night, Act ii. Sc. 1; Romeo and Juliet, Act i. Sc. 1). The Butterfly (Troilus and Cressida, Act iii. Sc. 3; Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act iii. Sc. 1); and Moth (Merchant of Venice, Act ii. Sc. 9; King John, Act iv. Sc. 1). The House-fly (Titus Andronicus, Act iii. Sc. 2). The small Gilded-fly (King Lear, Act iv. Sc. 6). The Blow-fly (Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act v. Sc. 2; Tempest, Act iii. Sc. 1); and the Gad-fly, or Brize (Troilus and Cressida, Act i. Sc. 3). The Grey-coated Gnat (Romeo and Juliet, Act i. Sc. 4; Comedy of Errors, Act ii. Sc. 2); the Wasp (Taming of the Shrew, Act ii. Sc. 1; Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act i. Sc. 2; Henry VIII. Act iii. Sc. 2); the Drone (Henry V. Act i. Sc. 2); and the Honey-bee (numerous passages).

To three only of these shall we direct further attention: firstly, because a more extended notice of all would be beyond the limits of the present work; and, secondly, because the Entomology of Shakespeare has been already dealt with elsewhere.25

These three are the Bee, the Drone, and the Fly, and we select quotations in reference to these in order to illustrate Shakespeare’s knowledge of the subject on which he wrote; the lessons to be learnt from his allusions; and the sympathy which he has manifested for all living creatures.

What better picture of the interior of a hive can be found than the following? How well are the duties of the inmates described!

“The lazy yawning drone” is frequently alluded to as the type of idleness and inactivity (Pericles, Act ii. Sc. 1; Henry VI. Part II. Act iii. Sc. 2).

And we are counselled—

Who does not remember the scene in which Titus Andronicus reproves his brother Marcus for killing a fly at dinner?—

This is but one of the many lessons taught us by Shakespeare in his allusions to the animal world, and the kindly spirit which characterizes all his dealings with animals is frequently exemplified throughout the Plays; perhaps nowhere so clearly as in Measure for Measure, Act iii. Sc. 1, where we are told—

Probably enough has been said to show the reader that Shakespeare’s knowledge of natural history was by no means slight, and if it be thought to have been only general, it was, at all events, accurate. The use which he has made of this knowledge, throughout his works, in depicting virtue and vice in their true colours, in pointing out lessons of industry, patience, and mercy, and in showing the profit to be derived from a study of natural objects, is everywhere apparent.

The words of the banished Duke, in As You Like It (Act ii. Sc. 1), seem to no one so applicable as to Shakespeare himself. He—

But to come to the Ornithology. The accurate observations on this subject, the apt allusions, and the beautiful metaphors to be met with throughout the Plays, may be said to owe their origin mainly to three causes. Firstly, Shakespeare had a good practical knowledge of Falconry, a pastime which, being much in vogue in his day, brought under his notice, almost of necessity, many wild birds, exclusive of the various species which were hawked at and killed. Secondly, he was a great reader, and, possessing a good memory, was enabled subsequently to express in verse ideas which had been suggested by older authors. Thirdly, and most important of all, he was a genuine naturalist, and gathered a large amount of information from his own practical observations. In all his walks, he evidently did not fail to note even the most trivial facts in natural history, and these were treasured up in his memory, to be called forth as occasion required, to be aptly and eloquently introduced into his works.

Apart from the consideration that a poet may be expected, almost of necessity, to invoke the birds of song, Shakespeare has gone further, and displays a greater knowledge of ornithology, and a greater accuracy in his statements, than is generally the case with poets. How far we shall succeed in proving this assertion, it will be for the reader of the following pages to determine.

AT the head of the diurnal birds of prey, most authors have agreed in placing the Eagles. Their large size, powerful flight, and great muscular strength, give them a superiority which is universally admitted. In reviewing, therefore, the birds of which Shakespeare has made mention, no apology seems to be necessary for commencing with the genus Aquila.

Throughout the works of our great dramatist, frequent allusions may be found to an eagle, but the word “eagle” is almost always employed in a generic sense, and in a few instances only can we infer, from the context, that a particular species is indicated. Indeed, it is not improbable that in the poet’s opinion only one species of eagle existed. Be this as it may, the introduction of an eagle and his attributes, by way of simile or metaphor, has been accomplished by Shakespeare with much beauty and effect. Considered as the emblem of majesty, the eagle has been variously styled “the king of birds,” “the royal bird,” “the princely eagle,” and “Jove’s bird,” while so great is his power of vision, that an “eagle eye” has become proverbial.

The clearness of vision in birds is indeed extraordinary, and has been calculated, by the eminent French naturalist Lacépède, to be nine times more extensive than that of the farthest-sighted man. The opinion that the eagle possessed the power of gazing undazzled at the sun, is of great antiquity. Pliny relates that it exposes its brood to this test as soon as hatched, to prove if they be genuine or not. Chaucer refers to the belief in his “Assemblie of Foules”:—

So also Spenser, in his “Hymn of Heavenly Beauty,”—

It is not surprising, therefore, that Shakespeare has borrowed the idea:—

Again—

But in the same play and scene we are told—

And in this respect Paris was said to excel:—

The supposition that the eye of the eagle is green must be regarded as a poetic license. In all the species of this genus with which we are acquainted, the colour of the iris is either hazel or yellow. But it would be absurd to look for exactness in trifles such as these.

The power of flight in the eagle is no less surprising than his power of vision. Birds of this kind have been killed which measured seven or eight feet from tip to tip of wing, and were strong enough to carry off hares, lambs, and even young children. This strength of wing is not unnoticed by Shakespeare:—

And—

This last line recalls to mind the following allusion to the flight of the Jerfalcon:—“Then prone she dashes with so much velocity, that the impression of her path remains on the eye, in the same manner as that of the shooting meteor or flashing lightning, and you fancy that there is a torrent of falcon rushing for fathoms through the air.”26

Spenser, in the fifth book of his “Faerie Queene” (iv. 42), has depicted the grandeur of an eagle on the wing:—

But notwithstanding his great powers of flight, we are reminded that the eagle is not always secure. Guns, traps, and other engines of destruction are directed against him, whenever and wheresoever opportunity occurs:—

With the Romans, the eagle was a bird of good omen. Josephus, the Jewish historian, says the eagle was selected for the Roman legionary standard, because he is the king of all birds, and the most powerful of them all, whence he has become the emblem of empire, and the omen of victory.27

Accordingly, we read in Julius Cæsar, Act v. Sc. 1:—

This incident is more fully detailed in North’s “Plutarch,” as follows:—“When they raised their campe, there came two eagles, that flying with a marvellous force, lighted upon two of the foremost ensigns, and alwaies followed the souldiers, which gave them meate and fed them, untill they came neare to the citie of Phillipes; and there one day onely before the battell, they both flew away.”

The ensign of the eagle was not peculiar, however, to the Romans. The golden eagle, with extended wings, was borne by the Persian monarchs,28 and it is not improbable that from them the Romans adopted it; while the Persians themselves may have borrowed the symbol from the ancient Assyrians, on whose banners it waved until Babylon was conquered by Cyrus.

As a bird of good omen, the eagle is often mentioned by Shakespeare:—

The name “Puttock” has been applied both to the Kite and the Common Buzzard, and both were considered birds of ill omen.

In Act iv. Sc. 2, of the same play, we read,—

This was said to portend success to the Roman host. In Izaak Walton’s “Compleat Angler,” we are furnished with a reason for styling the eagle “Jove’s bird.” The falconer, in discoursing on the merits of his recreation with a brother angler, says,—“In the air my troops of hawks soar upon high, and when they are lost in the sight of men, then they attend upon and converse with the gods; therefore I think my eagle is so justly styled Jove’s servant in ordinary.”

In a paper “On the Roman Imperial and Crested Eagles,”29 Mr. Hogg says,—“The Roman Eagle, which is generally termed the Imperial Eagle, is represented with its head plain, that is to say, not crested. It is in appearance the same as the attendant bird of the ‘king of gods and men,’ and is generally represented as standing at the foot of his throne, or sometimes as the bearer of his thunder and lightning. Indeed he also often appears perched on the top of his sceptre. He is always considered as the attribute or emblem of ‘Father Jove.’”

A good copy of this bird of Jupiter, called by Virgil and Ovid “Jovis armiger,” from an antique group, representing the eagle and Ganymedes, may be seen in Bell’s “Pantheon,” vol. i. Also “a small bronze eagle, the ensign of a Roman legion,” is given in Duppa’s “Travels in Sicily” (2nd ed., 1829, tab. iv.). That traveller states, that the original bronze figure is preserved in the Museum of the Convent of St. Nicholas d’Arcun, at Catania. This Convent is now called Convento di S. Benedetto, according to Mr. G. Dennis, in his “Handbook of Sicily,” (p. 349); and he mentions this ensign as “a Roman legionary eagle in excellent preservation.”

From the second century before Christ, the eagle is said to have become the sole military ensign, and it was mostly small in size, because Florus (lib. 4, cap. 12) relates that an ensign-bearer, in the wars of Julius Cæsar, in order to prevent the enemy from taking it, pulled off the eagle from the top of the gilt pole, and hid it by placing it under cover of his belt.

In later times, the eagle was borne with the legion, which, indeed, occasionally took its name, “aquila.” This eagle, which was also adopted by the Roman emperors for their imperial symbol, is considered to be the Aquila heliaca of Savigny (imperialis of Temminck), and resembles our golden eagle, Aquila chrysaëtos, in plumage, though of a darker brown, and with more or less white on the scapulars. It differs also in the structure of the foot. It inhabits Southern Europe, North Africa, Palestine, and India. Living examples of this species may be seen at the present time in the Gardens of the Zoological Society.

Sicilius, in Cymbeline (Act v. Sc. 4), speaking of the apparition and descent of Jupiter, who was seated upon an eagle, says,—

“Prune” signifies to clean and adjust the feathers, and is synonymous with plume. A word more generally used, perhaps, than either, is preen.

Cloys is, doubtless, a misprint for cleys, that is, claws. Those who have kept hawks must often have observed the habit which they have of raising one foot, and whetting the beak against it. This is the action to which Shakespeare refers. The same word occurs in Ben Jonson’s “Underwoods,” (vii. 29) thus:—

The verb “to cloy” has a very different signification, namely, “to satiate,” “choke,” or “clog up.” Shakespeare makes frequent use of it.

In “Lucrece” it occurs:—

And again, in Richard II. (Act i. Sc. 3):—

Sometimes the word was written “accloy;” as, for instance, in Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” (ii. 7)—

And in the same author’s “Shepheard’s Calendar” (February, 135)—

It is clear, therefore, that the word occurring in the fourth scene of the fifth act of Cymbeline, should be written cleys, and not cloys.

But to return from this digression; there is a passage in the first act of Henry V. Sc. 2, which seems to deserve some notice while on the subject of eagles, i.e.:—

That the weasel sucks eggs, and is partial to such fare, is very generally admitted. Shakespeare alludes to the fact again in As You Like It (Act ii. Sc. 5), where Jaques says:—“I can suck melancholy out of a song, as a weasel sucks eggs.” But whether the weasel has ever been found in the same situation or at such an altitude as the eagle, is not so certain. A near relative of the weasel, however, namely, a marten-cat, was once found in an eagle’s nest. “The forester, having reason to think that the bird was sitting hard, peeped over the cliff into the eyrie. To his amazement, a marten was suckling her kittens in comfortable enjoyment.”30

The allusion above made to the “princely eggs,” reminds us of the princely bird which laid them, and those who have read the works of Shakespeare—and who has not?—must doubtless remember the beautiful simile uttered by Warwick when dying on the field of Barnet:—

The conscious superiority of the eagle is depicted by Tamora, who tells us:—

The great age to which this bird sometimes attains has been remarked by most writers on Ornithology. The Psalmist has beautifully alluded to it where he says of the righteous man,—“His youth shall be renewed like the eagle’s.” A golden eagle, which had been nine years in the possession of Mr. Owen Holland, of Conway, lived thirty-two years with the gentleman who made him a present of it, but what its age was when the latter received it from Ireland is unknown.31 Another, that died at Vienna, was stated to have lived in confinement one hundred and four years.32 A white-tailed eagle captured in Caithness, died at Duff House in February, 1862, having been kept in confinement, by the late Earl of Fife, for thirty-two years. But even the eagle may be outlived. Apemantus asks of Timon:—

The old text has “moyst trees.” The emendation, however, which was made by Hanmer, is strengthened by the line in As You Like It (Act iv. Sc. 3):—

In an old French “riddle-book,” entitled “Demands Joyous,” which was printed in English by Wynkyn de Worde in 1511 (a single copy only of which is said to be extant), is the following curious “demande” and “response.” It is here transcribed, as bearing upon the subject of the age of an eagle:—

“Dem. What is the age of a field-mouse?

Res. A year. And the life of a hedge-hog is three times that of a mouse; and the life of a dog is three times that of a hedge-hog; and the life of a horse is three times that of a dog; and the life of a man is three times that of a horse; and the life of a goose is three times that of a man; and the life of a swan is three times that of a goose; and the life of a swallow is three times that of a swan; and the life of an eagle is three times that of a swallow; and the life of a serpent is three times that of an eagle; and the life of a raven is three times that of a serpent; and the life of a hart is three times that of a raven; and an oak groweth 500 years, and fadeth 500 years.”

The Rev. W. B. Daniel alludes33 to “the received maxim that animals live seven times the number of years that bring them to perfection,” upon which computation the average life of an eagle would be twenty-one years. But this maxim is founded on a misconception. Fleurens, in his treatise “De la Longévité Humaine,” says that the duration of life in any animal is equal to five times the number of years requisite to perfect its growth, and that the growth has ceased when the bones have finally consolidated with their epiphyses, which in the young are merely cartilages.

Like many other rapacious birds, eagles are very fond of bathing, and it has been found essential to supply them with baths when in confinement, in order to keep them in good health. The freshness and vigour which they thus derive is alluded to in Henry IV. (Part I. Act iv. Sc. 1):—

The larger birds of prey are no less fond of washing, though they care so little for water to drink, that it has been erroneously asserted that they never drink. “What I observed,” says the Abbé Spallanzani,34 “is, that eagles, when left even for several months without water, did not seem to suffer the smallest inconvenience from the want of it, but when they were supplied with water, they not only got into the vessel and sprinkled their feathers like other birds, but repeatedly dipped the beak, then raised the head, in the manner of common fowls, and swallowed what they had taken up. Hence it is evident that they drink.”

In Persia, Tartary, India, and other parts of the East, the eagle was formerly, and is still to a certain extent, used for hunting down the larger birds and beasts. In the thirteenth century, the Khan of Tartary kept upwards of two hundred hawks and eagles, some of which had been trained to catch wolves; and such was the boldness and power of these birds, that none, however large, could escape from their talons.35

Burton, in his “Anatomy of Melancholy,”36 quoting from Sir Antony Shirley’s “Travels,” says: “The Muscovian Emperours reclaim eagles, to let fly at hindes, foxes, &c., and such a one was sent for a present to Queen Elizabeth.”

A traveller to the Putrid Sea, in 1819, wrote: “Wolves are very common on these steppes; and they are so bold that they sometimes attack travellers. We passed by a large one, lying on the ground with an eagle, which had probably attacked him, by his side. Its talons were nearly buried in his back; in the struggle both had died.”37

Owing to the great difficulty in training them, as well as to the difficulty in obtaining them, eagles have rarely been trained to the chase in England. Some years since, Captain Green, of Buckden, in Huntingdonshire, had a fine golden eagle, which he had taught to take hares and rabbits;38 and this species has been found to be more tractable than any other.

Whether Shakespeare was aware of the use of trained eagles or not, we cannot say, but he has in many cases employed hawking terms in connection with this bird:—

The meaning of the word tire is thus explained by falconers. When a hawk was in training, it was often necessary to prolong her meal as much as possible, to prevent her from gorging; this was effected by giving her a tough or bony bit to tire on; that is, to tear, or pull at.

So also, in Timon of Athens (Act iii. Sc. 6), one of the lords says:—

In the following passage, two hawking terms are used in connection with the eagle:—

This passage has been differently rendered, by removing the punctuation between “aiery” and “towers,” and reading the former “airey” or “airy,” and making “towers” a substantive. But the meaning of the passage, as it stands above, seems to us sufficiently clear.

“Aiery” is equivalent to “eyrie,” the nesting-place. The word occurs again in Richard III. (Act i. Sc. 3):—

and,

The verb “to tower,” in the language of falconry, signifies “to rise spirally to a height.” Compare the French “tour.” As a further argument, too, for reading “towers” as a verb, and not as a substantive, compare the following passage from Macbeth, which plainly shows that Shakespeare was not unacquainted with this word as a hawking term:—

The word “souse,” above quoted, is likewise borrowed from the language of falconry, and, as a substantive, is equivalent to “swoop.” It would seem to be derived from the German “sausen,” which signifies to rush with a whistling sound like the wind; and this is certainly expressive of the “whish” made by the wings of a falcon when swooping on her prey.

There is a good illustration of this passage in Drayton’s “Polyolbion,” Song xx., where a description of hawking at wild-fowl is given. After the falconers have put up the fowl from the sedge, the hawk, in the words of the author, having previously “towered,” “gives it a souse.” Beaumont and Fletcher also make use of this word as a hawking term in The Chances, iv. 1; and it occurs in Spenser’s “Faerie Queene,” Book iv. Canto v. 30.

A notice of the various hawks made use of by falconers, and mentioned by Shakespeare, might be here properly introduced, but it will be more convenient to reserve this notice for a separate chapter, and confine our attention for the present to the larger diurnal birds of prey which, like the eagles, are seldom, if ever, reclaimed by man.

Of these, excluding the eagle, Shakespeare makes mention of four—the Vulture, the Osprey, the Kite, and the Buzzard.

Those who are acquainted with the repulsive habits of the Vulture, led as he is by instinct to gorge on carrion, will best understand the allusions to this bird which are to be met with in the works of Shakespeare.

What more forcible expression can be found to indicate a guilty conscience than “the gnawing vulture of the mind”? (Titus Andronicus, Act v. Sc. 2.)

When King Lear would denounce the unkindness of a daughter, which he could never forget, laying his hand upon his heart, he exclaims:—

One of the worst wishes to which Falstaff could give vent when in a bad humour, was:—

And the same idea is expressed in Henry IV. (Part II. Act v. Sc. 4):—

Occasionally we find the word “vulture” employed as an adjective:—

And—

The structure of the Osprey is wonderfully adapted to his habits, and an examination of the feet of this bird will prove how admirably contrived they are for grasping and holding a slippery fish. Mr. St. John, who had excellent opportunities of studying the Osprey in his native haunts, says:39—“I generally saw the osprey fishing about the lower pools of the rivers near their mouths; and a beautiful sight it is. The long-winged bird hovers (as a kestrel does over a mouse), at a considerable distance above the water, sometimes on perfectly motionless wing, and sometimes, wheeling slowly in circles, turning his head and looking eagerly down at the water. He sees a trout when at a great height, and suddenly closing his wings, drops like a shot bird into the water, often plunging completely under, and at other times appearing scarcely to touch the water, but seldom failing to rise again with a good-sized fish in his talons. Sometimes, in the midst of his swoop, the osprey stops himself suddenly in the most abrupt manner, probably because the fish, having changed its position, is no longer within range. He then hovers, again stationary, in the air, anxiously looking below for the re-appearance of the prey. Having well examined one pool, he suddenly turns off, and with rapid flight takes himself to an adjoining part of the stream, where he again begins to hover and circle in the air. On making a pounce into the water, the osprey dashes up the spray far and wide, so as to be seen for a considerable distance.”

After this description, it is easy to understand the allusion of Aufidius, who says:—

Mr. Staunton thinks that the image is founded on the fabulous power attributed to the osprey of fascinating the fish on which he preys. In Peele’s play of The Battle of Alcazar, 1594 (Act i. Sc. 1), we read:—

Another of the birds of prey mentioned by Shakespeare is “the lazar Kite” (Henry V. Act ii. Sc. 1). Although a large bird, and called by some the royal Kite (Milvus regalis), it has not the bold dash of many of our smaller hawks in seizing live and strong prey, but glides about ignobly, looking for a sickly or wounded victim, or for offal of any sort.

From the ignoble habits of the bird, the name “kite” became a term of reproach:—

And—

When pressed by hunger, however, the kite becomes more fearless; and instances have occurred in which a bird of this species has entered the farmyard and boldly carried off a chicken.

The synonym “puttock” is sometimes applied to the kite, sometimes to the common buzzard. In the following passage, where reference is made to the supposed murder of Gloster by Suffolk, it evidently has reference to the former bird:—

With the ancients the kite appears to have been a bird of ill-omen. In Cymbeline (Act i. Sc. 2), Imogen says:—

And the superiority of the eagle is again adverted to by Hastings, in Richard III. (Act i. Sc. 1):—

The intractable disposition of the kite is thus noticed:—

A wild hawk was sometimes tamed by watching it night and day, to prevent its sleeping. In “An approved treatyse of Hawks and Hawking,” by Edmund Bert, Gent., which was published in London in 1619, the author says:—“I have heard of some who watched and kept their hawks awake seven nights and as many days, and then they would be wild, rammish, and disorderly.” This practice is often alluded to by Shakespeare:—

The habit which the kite has, in common with other rapacious birds, of rejecting or disgorging the undigested portions of its food, such as bones and fur, in the shape of pellets, was apparently well known to Shakespeare, for he says:—

And again,—

Another curious fact in the natural history of the kite is adverted to in the Winter’s Tale (Act iv. Sc. 2). It is there said,—

This line may be perhaps best illustrated by giving a description of a kite’s nest which we have seen, and which was taken many years ago in Huntingdonshire. The outside of the nest was composed of strong sticks; the lining consisted of small pieces of linen, part of a saddle-girth, a bit of a harvest glove, part of a straw bonnet, pieces of paper, and a worsted garter. In the midst of this singular collection of materials were deposited two eggs. The kite is now almost extinct in England, and a kite’s nest, of course, is a great rarity. The Rev. H. B. Tristram, speaking of the habits of the Egyptian kite (Milvus Ægyptius), says:40—“Its nest, the marine store-shop of the desert, is decorated with whatever scraps of bournouses and coloured rags can be collected; and to these are added, on every surrounding branch, the cast-off coats of serpents, large scraps of thin bark, and perhaps a bustard’s wing.”

We have alluded to the Buzzard (Buteo vulgaris) in the passage above quoted from Richard III., and also to the synonym “puttock,” which was sometimes applied to this bird, as well as to the kite.

Mr. St. John, who was well acquainted with the common buzzard, thought that in all its habits it more nearly resembled the eagle than any other kind of hawk.41

In the following passage, it seems probable, as suggested by Mr. Staunton, that a play upon the words is intended, and that “buzzard” in the second line means a beetle, so called from its buzzing noise:—

Neither the kite nor the buzzard were ever trained for hawking, being deficient both in speed and pluck.

The former, however, was occasionally “flown at” by falconers, although oftener for want of a better bird, than because he showed much sport.

Both are now far less common than in Shakespeare’s day. The increased number of shooters, and the war of extermination which is carried on by gamekeepers, inevitably seal their doom.

TO those who have ever taken part in a hawking excursion, it must be a matter of some surprise that so delightful a pastime has ceased to be popular. Yet, at the present day, perhaps not one person in five hundred has ever seen a trained hawk flown. In Shakespeare’s time things were very different. Every one who could afford it kept a hawk, and the rank of the owner was indicated by the species of bird which he carried. To a king belonged the gerfalcon; to a prince, the falcon gentle; to an earl, the peregrine; to a lady, the merlin; to a young squire, the hobby; while a yeoman carried a goshawk; a priest, a sparrowhawk; and a knave, or servant, a kestrel. But the sport was attended with great expense, and much time and attention were required of the falconer before his birds were perfectly trained, and he himself a proficient.

This, combined with the increased enclosure and cultivation of waste lands, has probably contributed as much as anything to the decline of falconry in England.

During the age in which Shakespeare lived, the sport was at its height, and it is, therefore, not surprising that he has taken much notice of it in his works, and has displayed a considerable knowledge on the subject.

In the second part of King Henry VI. Act 2, we find a scene laid at St. Alban’s, and the King, Queen, Gloster, Cardinal, and Suffolk appearing, with falconers halloaing. We quote that portion of the scene which refers more particularly to the sport:—

“Flying at the brook” is synonymous with “hawking by the river,” and shows us that the party were in pursuit of water-fowl. Chaucer speaks of

“Point.”—The fluttering or hovering over the spot where the “quarry” has been “put in.”

“Pitch.”—The height to which a hawk rises before swooping.

“Tower.”—A common expression in falconry, signifying to rise spirally to a height. Compare the French “tour.” The word occurs again in Macbeth, Act ii. Sc. 4, with reference to a fact which we might well be excused for doubting, did we not know that it was related as an unusual circumstance:—

Many of the incidents connected with Duncan’s death are not to be found in the narrative of that event, but are taken from the chronicler’s account of King Duffe’s murder. Among the prodigies there mentioned is the one referred to by Shakespeare. “Monstrous sightes also, that were seene without the Scottishe kingdome that year, were these.… There was a sparhauke also strangled by an owle.” We have known a Tawny Owl to kill and devour a Kestrel which had been kept in the same aviary with it.

By “tow’ring in her pride of place,” is here understood to mean circling at her highest point of elevation. So in Massinger’s play of The Guardian, Act i. Sc. 2:—

By the falcon is always understood the female, as distinguished from the tercel, or male, of the peregrine or goshawk. The latter was probably called the tercel, or tiercel, from being about a third smaller than the falcon. Some authorities, however, state that of the three young birds usually found in the nest of a falcon, two of them are females and the third a male; hence the name of tercel.43

By others, again, the term is supposed to have been derived from the French gentil, meaning neat or handsome, because of the beauty of its form.

There appears to be a great deal of confusion in the nomenclature of the hawks used in falconry. The same name has been applied to two distinct species, and the same species, in different states of plumage, has received two or more names. With regard to the “tercel,” as distinguished from the “tercel-gentle,” it would appear that the former name was given to the male goshawk, and the latter to the male peregrine; for the peregrine being a long-winged hawk, and the more noble of the two, the word “gentle,” or “gentil,” was applied to it with that signification.

In this view we are supported to some extent by quaint old Izaak Walton. In his “Compleat Angler,” there is an animated conversation between an angler, a hunter, and a falconer, each of whom in turn commends his own recreation. The falconer gives a list of his hawks, and divides them into two classes, viz.: the long-winged and short-winged hawks. In enumerating each species in pairs, he gives first the name of the female, and then that of the male: among the first class we find—

In the second class we have—

From this we may conclude that the name tercel-gentle was applied to the male peregrine, a long-winged hawk, to distinguish it from the tercel, or male goshawk, a short-winged hawk.

The female falcon, from her greater size and strength, was always considered superior to the male—stronger in flight:—

And possessing more powerful talons:—

She was more easily trained, and capable of being flown at larger game. Hence Shakespeare asserts—

Sometimes we find the word “tercel” written “tassel,” as in Romeo and Juliet (Act ii. Sc. 2):—

Spenser almost invariably spells the word in this way.45 To understand the allusion to the falconer’s voice, it should be observed that after a hawk had been flown, and had either struck or missed the object of her pursuit, the “lure” (which we shall presently describe) was thrown up to entice her back, and at the same time the falconer shouted to attract her attention.

Professor Schneider, in a Latin volume published at Leipsic, in 1788,46 thus enumerates the qualities of a good falconer: “Sit mediocris staturæ; sit perfecti ingenii; bonæ memoriæ; levis auditu; acuti visûs; homo magnæ vocis; sit agilis et promptus; sciat natare,” &c. &c.

Each falconer had his own particular call, but it was generally somewhat like—

The “lure” was of various shapes, and consisted merely of a piece of iron or wood, generally in the shape of a heart or horseshoe, to which were attached the wings of some bird, with a piece of raw meat fixed between them. A strong leathern strap, about three feet long, fastened to it with a swivel, enabled the falconer to swing it round his head, or throw it to a distance. With high-flying hawks, however, it was often found necessary to use a live pigeon, secured to a string by soft leather jesses, in order to recall them.47

The long-winged hawks were always brought to the lure, the short-winged ones to the hand:—

The game flown at was called in hawking parlance the “quarry,” and differed according to the hawk that was used. The gerfalcon and peregrine were flown at herons, ducks, pigeons, rooks, and magpies; the goshawk was used for hares and partridges; while the smaller kinds, such as the merlin and hobby, were trained to take blackbirds, larks, and snipe. The French falconers, however, do not appear to have been so particular:—

“We’ll e’en to ’t like French falconers, fly at anything we see.”—Hamlet, Act ii. Sc. 2.

The word “quarry” occurs in many of the Plays.

In the language of the forest, “quarry” also meant a heap of slaughtered game. So, in Coriolanus (Act iii. Sc. 1), Caius Marcius says:—

The beauty of the following passage, from its being clothed in technicalities, will be likely to escape the notice of those who are not conversant with hawking phraseology; but an acquaintance with the terms employed will elicit admiration at the force and beauty of the metaphor.

Othello, mistrusting the constancy of Desdemona towards him, and comparing her to a hawk, exclaims:—

By “haggard” is meant a wild-caught and unreclaimed mature hawk, as distinguished from an “eyess,” or nestling; that is, a young hawk taken from the “eyrie” or nest.

By some falconers “haggards” were also called “passage hawks,” from being always caught when in that state, at the time of their periodical passage or migration. As will be seen hereafter, the word “haggard” occurs frequently throughout the Plays.

The “jesses” were two narrow strips of leather, fastened one to each leg, the other ends being attached to a swivel, from which depended the “leash.” When the hawk was flown, the swivel and leash were taken off, the jesses and bells remaining on the bird.

Some of the old falconers’ directions on these points are very quaint. Turbervile, in his “Book of Falconrie,” 1575, speaking of the trappings of a hawk, says:—“Shee must haue jesses of leather, the which must haue knottes at the ende, and they should be halfe a foote long, or there about; at the least a shaftmeete betweene the hoose of the jesse, and the knotte at the ende, whereby you tye the hauke.”

In the modern “jesse,” however, there are no knots. It is fastened in this wise. The leg of the hawk is placed against the “jesse,” between the slits A and B. The end A is then passed through the slit B, and the end C in turn through the slit A. The swivel, with its dependent leash, is then attached to slit C; and the same with the other leg.

Othello says:—

Falconers always flew their hawk against the wind. If flown down the wind, she seldom returned. When, therefore, a useless bird was to be dismissed, her owner flew her “down the wind;” and thenceforth she shifted for herself, and was said “to prey at fortune.”

The word “haggard,” as before observed, is of frequent occurrence throughout the Plays of Shakespeare. In the Taming of the Shrew (Act iv. Sc. 2), Hortensio speaks of Bianca as “this proud disdainful haggard.” In Much Ado about Nothing (Act iii. Sc. 1), Hero, alluding to Beatrice, says—

In Twelfth Night (Act iii. Sc. 1), Viola says of the Clown:—

To “check” is a term used in falconry, signifying to “fly at,” although it sometimes meant to “change the bird in pursuit.”49 The word occurs again in the same play (Act ii. Sc. 4), and in Hamlet, Act iv. Sc. 7.

Besides the “jesses,” the “bells” formed an indispensable part of a hawk’s trappings. These were of circular form, from a quarter to a full inch in diameter, and made of brass or silver, and were attached, one to each leg of the bird, by means of small slips of leather called “bewits.” The use of bells was to lead the falconer by their sound to the hawk when in a wood, or out of sight.

“As the ox hath his bow,50 sir, the horse his curb, and the falcon her bells, so man hath his desires.”—As You Like It, Act iii. Sc. 3.

So in Henry VI. Part III. Act i. Sc. 1—

Again—

The “hood,” too, was a necessary appendage to the trained falcon. This was a cap or cover for the head, which was not removed until the “quarry” was started, in order to prevent the hawk from flying too soon.

The Constable of France, speaking of the valour of the Dauphin, says:—

The allusion is to the ordinary action of a hawk, which, when unhooded, bates, or flutters. But a quibble may be here intended between “bate,” the hawking technical, and “bate,” to dwindle or abate. The word occurs again in Romeo and Juliet (Act iii. Sc. 2)—

And to those not conversant with the terms employed in falconry, this line would be unintelligible. An “unmanned” hawk was one not sufficiently reclaimed to be familiar with her keeper, and such birds generally “bated,” that is, fluttered or beat their wings violently in their efforts to escape.

Petruchio, in The Taming of the Shrew, gives us a lesson in reclaiming a hawk when speaking thus of Catherine:—

The word “stoop,” sometimes written “stoup” (Spenser’s “Faerie Queene,” Book I. Canto XI. 18), and “swoop” (Macbeth, “at one fell swoop”), signifies a rapid descent on the “quarry.” It occurs again in Henry V. Act iv. Sc. 1:—

“And though his affections are higher mounted than ours, yet, when they stoop, they stoop with the like wing.”

The hawks, when carried to the field, were borne on “the cadge,” as shown in the engraving; the person carrying it being called “the cadger.” The modern word “cad,” now generally used in an opprobrious sense, is in all probability an abbreviation of “cadger,” and therefore synonymous with “servant” or common fellow.

Florizel, addressing Perdita, in the Winter’s Tale (Act iv. Sc. 3), says,—

for this was the occasion of his first meeting her.

In the following passage from Measure for Measure, (Act iii. Sc. 1), there occurs a word in connection with falconry, which requires some explanation,—

The verb “to mew,” or “enmew,” signifies to enclose or shut up, owing its origin to the word “mews,” the place where the hawks were confined:—

Gremio, speaking of Bianca to Signor Baptista, says,—

A question presently solved by Tranio, who says:—

The word “mew,” derived from the old French “mue,” signifies a change, or moult, when birds and other animals cast their feathers, hair, or horns. Hence Latham observes that “the mew is that place, whether it be abroad or in the house, where you set down your hawk during the time she raiseth or reproduceth her feathers.”

It was necessary to take great care of a hawk in her mewing time. In “The Gentleman’s Academie,” edited by Gervase Markham, 1595, there are several sections on the mewing of hawks, from one of which it may be learnt that the best time to commence is in the beginning of Lent; and if well kept, the bird will be mewed, that is, moulted, by the beginning of August.

The Royal hawks were kept at the mews at Charing Cross during many reigns (according to Stowe, from the time of Richard II., in 1377), but they were removed by Henry VIII., who converted the place into stables. The name, however, confirmed by the usage of so long a period, remained to the building, although, after the hawks were withdrawn, it became inapplicable. But, what is more curious still, in later times, when the people of London began to build ranges of stabling at the back of their streets and houses, they christened those places “mews,” after the old stabling at Charing Cross.