The Project Gutenberg EBook of Greater Britain, by Charles Wentworth Dilke

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Greater Britain

A Record of Travel in English-Speaking Countries During 1866-7

Author: Charles Wentworth Dilke

Release Date: January 1, 2013 [EBook #41755]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GREATER BRITAIN ***

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

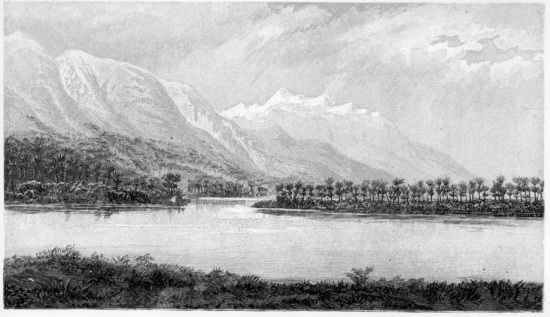

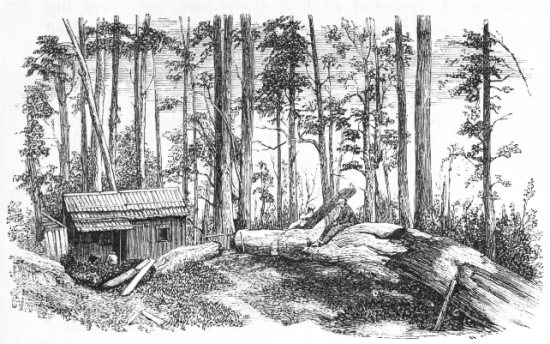

VIEW FROM THE BULLER, NEW ZEALAND.

A RECORD OF TRAVEL

IN

ENGLISH-SPEAKING COUNTRIES

DURING 1866-7.

BY

CHARLES WENTWORTH DILKE.

TWO VOLUMES IN ONE.

W I T H M A P S A N D I L L U S T R A T I O N S.

PHILADELPHIA:

J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO.

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO.

1869.

TO

M Y F A T H E R

I D e d i c a t e

THIS BOOK.

C. W. D.

In 1866 and 1867, I followed England round the world: everywhere I was in English-speaking, or in English-governed lands. If I remarked that climate, soil, manners of life, that mixture with other peoples had modified the blood, I saw, too, that in essentials the race was always one.

The idea which in all the length of my travels has been at once my fellow and my guide—a key wherewith to unlock the hidden things of strange new lands—is a conception, however imperfect, of the grandeur of our race, already girding the earth, which it is destined, perhaps, eventually to overspread.

In America, the peoples of the world are being fused together, but they are run into an English mould: Alfred‘s laws and Chaucer‘s tongue are theirs whether they would or no. There are men who say that Britain in her age will claim the glory of having planted greater Englands across the seas. They fail to perceive that she has done more than found plantations of her own—that she has imposed her institutions upon the offshoots of Germany, of Ireland, of Scandinavia, and of Spain. Through America, England is speaking to the world.

Sketches of Saxondom may be of interest even upon humbler grounds: the development of the England of Elizabeth is to be found, not in the Britain of Victoria, but in half the habitable globe. If two small islands are by courtesy styled “Great,” America, Australia, India, must form a Greater Britain.

C. W. D.

76 Sloane Street, S. W.

1st November, 1868.

| PART I. | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | VIRGINIA | 3 |

| II. | THE NEGRO | 16 |

| III. | THE SOUTH | 27 |

| IV. | THE EMPIRE STATE | 33 |

| V. | CAMBRIDGE COMMENCEMENT | 43 |

| VI. | CANADA | 55 |

| VII. | UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN | 69 |

| VIII. | THE PACIFIC RAILROAD | 78 |

| IX. | OMPHALISM | 86 |

| X. | LETTER FROM DENVER | 91 |

| XI. | RED INDIA | 102 |

| XII. | COLORADO | 110 |

| XIII. | ROCKY MOUNTAINS | 115 |

| XIV. | BRIGHAM YOUNG | 122 |

| XV. | MORMONDOM | 127 |

| XVI. | WESTERN EDITORS | 131 |

| XVII. | UTAH | 144 |

| XVIII. | NAMELESS ALPS | 152 |

| XIX. | VIRGINIA CITY | 166 |

| XX. | EL DORADO | 179 |

| XXI. | LYNCH LAW | 190 |

| XXII. | GOLDEN CITY | 207 |

| XXIII. | LITTLE CHINA | 218 |

| XXIV. | CALIFORNIA | 227 |

| XXV. | MEXICO | 233 |

| XXVI. | REPUBLICAN OR DEMOCRAT | 239 |

| XXVII. | BROTHERS | 249 |

| XXVIII. | AMERICA | 258 |

| PART II. | ||

| I. | PITCAIRN ISLAND | 271 |

| II. | HOKITIKA | 278 |

| III. | POLYNESIANS | 293 |

| IV. | PAREWANUI PAH | 299 |

| V. | THE MAORIES | 319 |

| VI. | THE TWO FLIES | 328 |

| VII. | THE PACIFIC | 334 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| A MAORI DINNER | 339 | |

| PART III. | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

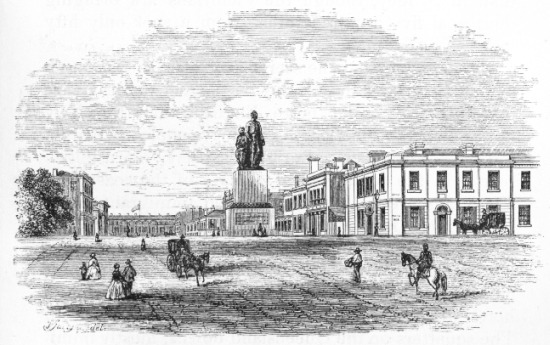

| I. | SYDNEY | 7 |

| II. | RIVAL COLONIES | 15 |

| III. | VICTORIA | 22 |

| IV. | SQUATTER ARISTOCRACY | 38 |

| V. | COLONIAL DEMOCRACY | 44 |

| VI. | PROTECTION | 55 |

| VII. | LABOR | 65 |

| VIII. | WOMAN | 75 |

| IX. | VICTORIAN PORTS | 79 |

| X. | TASMANIA | 83 |

| XI. | CONFEDERATION | 94 |

| XII. | ADELAIDE | 98 |

| XIII. | TRANSPORTATION | 109 |

| XIV. | AUSTRALIA | 123 |

| XV. | COLONIES | 130 |

| PART IV. | ||

| I. | MARITIME CEYLON | 141 |

| II. | KANDY | 154 |

| III. | MADRAS TO CALCUTTA | 161 |

| IV. | BENARES | 171 |

| V. | CASTE | 178 |

| VI. | MOHAMMEDAN CITIES | 191 |

| VII. | SIMLA | 202 |

| VIII. | COLONIZATION | 217 |

| IX. | THE “GAZETTE” | 224 |

| X. | UMRITSUR | 233 |

| XI. | LAHORE | 245 |

| XII. | OUR INDIAN ARMY | 249 |

| XIII. | RUSSIA | 255 |

| XIV. | NATIVE STATES | 267 |

| XV. | SCINDE | 280 |

| XVI. | OVERLAND ROUTES | 289 |

| XVII. | BOMBAY | 298 |

| XVIII. | THE MOHURRUM | 305 |

| XIX. | ENGLISH LEARNING | 312 |

| XX. | INDIA | 320 |

| XXI. | DEPENDENCIES | 333 |

| XXII. | FRANCE IN THE EAST | 339 |

| XXIII. | THE ENGLISH | 346 |

| VOLUME I. | |

| PAGE | |

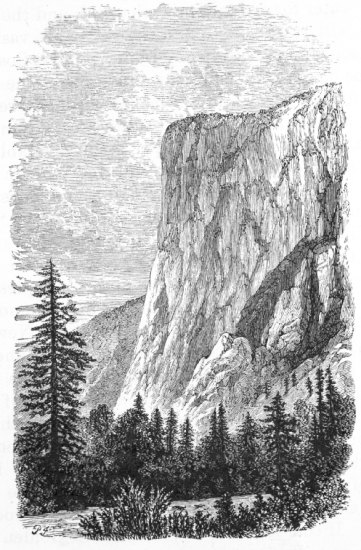

| VIEW FROM THE BULLER | Frontispiece. |

| A CINGHALESE GENTLEMAN | Frontispiece. |

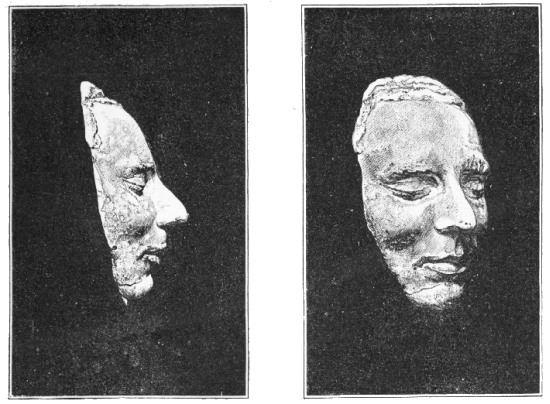

| PROFILE OF “JOE SMITH” | 150 |

| FULL FACE OF “JOE SMITH” | 150 |

| PORTER ROCKWELL | 154 |

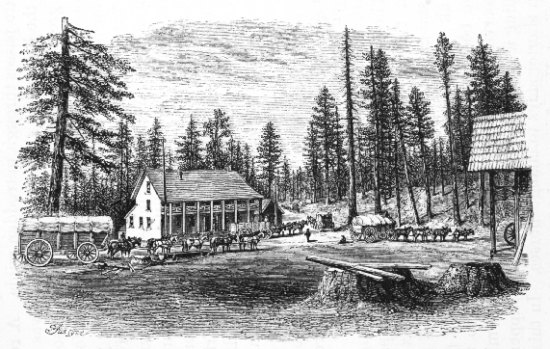

| FRIDAY‘S STATION—VALLEY OF LAKE TAHOE | 176 |

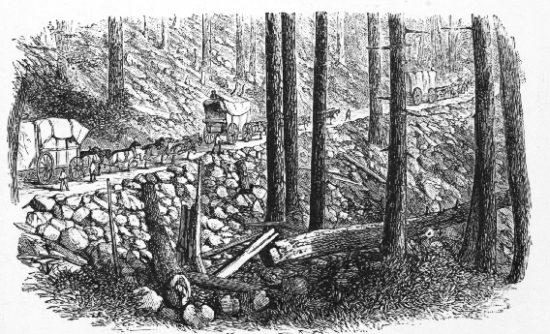

| TEAMING UP THE GRADE AT SLIPPERY FORD, IN THE SIERRA | 178 |

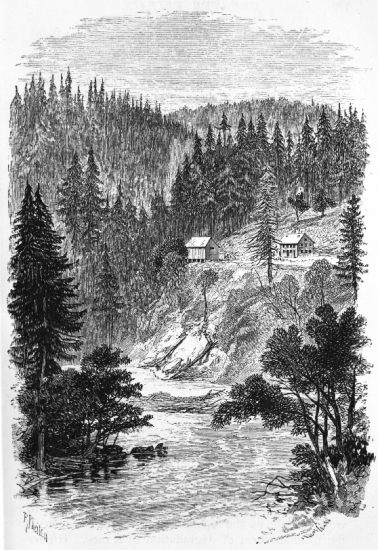

| VIEW ON THE AMERICAN RIVER—THE PLACE WHERE GOLD WAS FIRST FOUND | 180 |

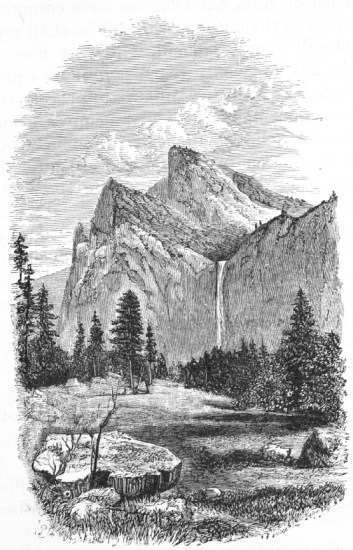

| THE BRIDAL VEIL FALL, YOSEMITE VALLEY | 228 |

| EL CAPITAN, YOSEMITE VALLEY | 228 |

| MAPS. | |

| ATLANTIC AND PACIFIC RAILROAD | 78 |

| LEAVENWORTH TO SALT LAKE CITY | 92 |

| SALT LAKE CITY TO SAN FRANCISCO | 158 |

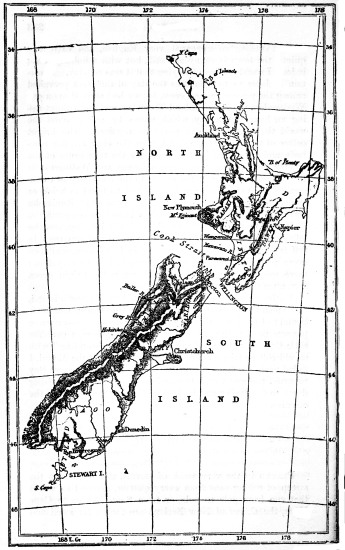

| NEW ZEALAND | 278 |

| VOLUME II. | |

| THE OLD AND THE NEW: BUSH SCENERY—COLLINS STREET EAST, MELBOURNE | 24 |

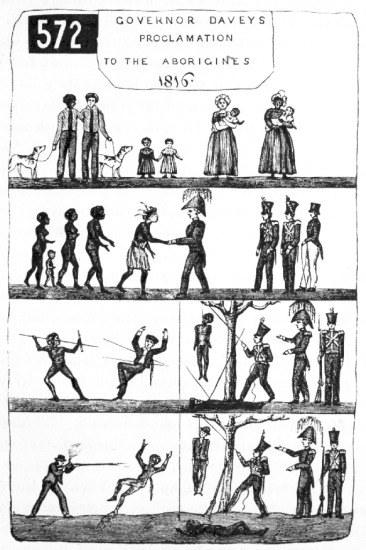

| GOVERNOR DAVEY‘S PROCLAMATION | 86 |

| MAPS. | |

| AUSTRALIA AND TASMANIA | 16 |

| OVERLAND ROUTES1340 | 290 |

G R E A T E R B R I T A I N.

FROM the bows of the steamer Saratoga, on the 20th June, 1866, I caught sight of the low works of Fort Monroe, as, threading her way between the sand-banks of Capes Charles and Henry, the ship pressed on, under sail and steam, to enter Chesapeake Bay.

Our sudden arrival amid shoals of sharks and kingfish, the keeping watch for flocks of canvas-back ducks, gave us enough and to spare of idle work till we fully sighted the Yorktown peninsula, overgrown with ancient memories—ancient for America. Three towns of lost grandeur, or their ruins, stand there still. Williamsburg, the former capital, graced even to our time by the palaces where once the royal governors held more than regal state; Yorktown, where Cornwallis surrendered to the continental troops; Jamestown, the earliest settlement, founded in 1607, thirteen years before old Governor Winthrop fixed the site of Plymouth, Massachusetts.

A bump against the pier of Fort Monroe soon roused us from our musings, and we found ourselves invaded by a swarm of stalwart negro troopers, clothed in the cavalry uniform of the United States, who boarded us for the mails. Not a white man save those we brought was to be seen upon the pier, and the blazing sun made me thankful that I had declined an offered letter to Jeff. Davis.

Pushing off again into the stream, we ran the gantlet of the Rip-Raps passage, and made for Norfolk, having on our left the many exits of the Dismal Swamp Canal. Crossing Hampton Roads—a grand bay with pleasant grassy shores, destined one day to become the best known, as by nature it is the noblest, of Atlantic ports—we nearly ran upon the wrecks of the Federal frigates Cumberland and Congress, sunk by the rebel ram Merrimac in the first great naval action of the war; but soon after, by a sort of poetic justice, we almost drifted into the black hull of the Merrimac herself. Great gangs of negroes were laboring laughingly at the removal, by blasting, of the sunken ships.

When we were securely moored at Norfolk pier, I set off upon an inspection of the second city of Virginia. Again not a white man was to be seen, but hundreds of negroes were working in the heat, building, repairing, road-making, and happily chattering the while. At last, turning a corner, I came on a hotel, and, as a consequence, on a bar and its crowd of swaggering whites—“Johnny Rebs” all, you might see by the breadth of their brims, for across the Atlantic a broad brim denotes less the man of peace than the ex-member of a Southern guerrilla band, Morgan‘s, Mosby‘s, or Stuart‘s. No Southerner will wear the Yankee “stove-pipe” hat; a Panama or Palmetto for him, he says, though he keeps to the long black coat that rules from Maine to the Rio Grande.

These Southerners were all alike—all were upright, tall, and heavily moustached; all had long black hair and glittering eyes, and I looked instinctively for the baldric and rapier. It needed no second glance to assure me that as far as the men of Norfolk were concerned, the saying of our Yankee skipper was not far from the truth: “The last idea that enters the mind of a Southerner is that of doing work.”

Strangers are scarce in Norfolk, and it was not long before I found an excuse for entering into conversation with the “citizens.” My first question was not received with much cordiality by my new acquaintances. “How do the negroes work? Wall, we spells nigger with two ‘g‘s,’ I reckon.” (Virginians, I must explain, are used to “reckon” as much as are New Englanders to “guess,” while Western men “calculate” as often as they cease to swear.) “How does the niggers work? Wall, niggers is darned fools, certain, but they ain‘t quite sich fools as to work while the Yanks will feed ’em. No, sir, not quite sich fools as that.” Hardly deeming it wise to point to the negroes working in the sun-blaze within a hundred yards, while we sat rocking ourselves in the veranda of the inn, I changed my tack, and asked whether things were settling down in Norfolk. This query soon led my friends upon the line I wanted them to take, and in five minutes we were well through politics, and plunging into the very war. “You‘re a Britisher. Now, all that they tell you‘s darned lies. We‘re just as secesh as we ever was, only so many‘s killed that we can‘t fight—that‘s all, I reckon.” “We ain‘t going to fight the North and West again,” said an ex-colonel of rebel infantry; “next time we fight, ’twill be us and the West against the Yanks. We‘ll keep the old flag then, and be darned to them.” “If it hadn‘t been for the politicians, we shouldn‘t have seceded at all, I reckon: we should just have kept the old flag and the constitution, and the Yanks would have seceded from us. Reckon we‘d have let ’em go.” “Wall, boys, s‘pose we liquor?” closed in the colonel, shooting out his old quid, and filling in with another. “We‘d have fought for a lifetime if the cussed Southerners hadn‘t deserted like they did.” I asked who these “Southerners” were to whom such disrespect was being shown. “You didn‘t think Virginia was a Southern State over in Britain, did you? ’cause Virginia is a border State, sir. We didn‘t go to secede at all; it was them blasted Southerners that brought it on us. First they wouldn‘t give a command to General Robert E. Lee, then they made us do all the fighting for ’em, and then, when the pinch came, they left us in the lurch. Why, sir, I saw three Mississippi regiments surrender without a blow—yes, sir: that‘s right down good whisky; jess you sample it.” Here the steam-whistle of the Saratoga sounded with its deep bray. “Reckon you‘ll have to hurry up to make connections,” said one of my new friends, and I hurried off, not without a fear lest some of the group should shoot after me, to avenge the affront of my quitting them before the mixing of the drinks. They were but a pack of “mean whites,” “North Carolina crackers,” but their views were those which I found dominant in all ranks at Richmond, and up the country in Virginia.

After all, the Southern planters are not “The South,” which for political purposes is composed of the “mean whites,” of the Irish of the towns, and of the Southwestern men—Missourians, Kentuckians, and Texans—fiercely anti-Northern, without being in sentiment what we should call Southern, certainly not representatives of the “Southern Chivalry.” The “mean whites,” or “poor trash,” are the whites who are not planters—members of the slaveholding race who never held a slave—white men looked down upon by the negroes. It is a necessary result of the despotic government of one race by another that the poor members of the dominant people are universally despised: the “destitute Europeans” of Bombay, the “white loafers” of the Punjaub, are familiar cases. Where slavery exists, the “poor trash” class must inevitably be both large and wretched: primogeniture is necessary to keep the plantations sufficiently great to allow for the payment of overseers and the supporting in luxury of the planter family, and younger sons and their descendants are not only left destitute, but debarred from earning their bread by honest industry, for in a slave country labor is degrading.

The Southern planters were gentlemen, possessed of many aristocratic virtues, along with every aristocratic vice; but to each planter there were nine “mean whites,” who, though grossly ignorant, full of insolence, given to the use of the knife and pistol upon the slightest provocation, were, until the election of Lincoln to the presidency, as completely the rulers of America as they were afterward the leaders of the rebellion.

At sunset we started up the James on our way to City Point and Richmond, sailing almost between the very masts of the famous rebel privateer the Florida, and seeing her as she lay under the still, gray waters. She was cut out from a Brizilian port, and when claimed by the imperial government, was to have been at once surrendered. While the dispatches were on their way to Norfolk, she was run into at her moorings by a Federal gunboat, and filled and sank directly. Friends of the Confederacy have hinted that the collision was strangely opportune; nevertheless, the fact remains that the commander of the gunboat was dismissed the navy for his carelessness.

The twilight was beyond description lovely. The change from the auks and ice-birds of the Atlantic to the blue-birds and robins of Virginia was not more sudden than that from winter to tropical warmth and sensuous indolence; but the scenery, too, of the river is beautiful in its very changelessness. Those who can see no beauty but in boldness might call the James as monotonous as the lower Loire.

After weeks of bitter cold, warm evenings favor meditation. The soft air, the antiquity of the forest, the languor of the sunset breeze, all dispose to dream and sleep. That oak has seen Powhatan; the founders of Jamestown may have pointed at that grand old sycamore. In this drowsy humor, we sighted the far-famed batteries of Newport News, and turning-in to berth or hammock, lay all night at City Point, near Petersburg.

A little before sunrise we weighed again, and sought a passage through the tremendous Confederate “obstructions.” Rows of iron skeletons, the frame-works of the wheels of sunken steamers, showed above the stream, casting gaunt shadows westward, and varied only by here and there a battered smoke-stack or a spar. The whole of the steamers that had plied upon the James and the canals before the war were lying here in rows, sunk lengthwise along the stream. Two in the middle of each row had been raised to let the government vessels pass, but in the heat-mist and faint light the navigation was most difficult. For five and twenty miles the rebel forts were as thick as the hills and points allowed; yet, in spite of booms and bars, of sunken ships, of batteries and torpedoes, the Federal monitors once forced their way to Fort Darling in the outer works of Richmond. I remembered these things a few weeks later, when General Grant‘s first words to me at Washington were: “Glad to meet you. What have you seen?” “The Capitol.” “Go at once and see the Monitors.” He afterward said to me, in words that photograph not only the Monitors, but Grant: “You can batter away at those things for a month, and do no good.”

At Dutch Gap we came suddenly upon a curious scene. The river flowed toward us down a long, straight reach, bounded by a lofty hill crowned with tremendous earthworks; but through a deep trench or cleft, hardly fifty yards in length, upon our right, we could see the stream running with violence in a direction parallel with our course. The hills about the gully were hollowed out into caves and bomb-proofs, evidently meant as shelters from vertical fire, but the rough graves of a vast cemetery showed that the protection was sought in vain. Forests of crosses of unpainted wood rose upon every acre of flat ground. On the peninsula, all but made an island by the cleft, was a grove of giant trees, leafless, barkless, dead, and blanched by a double change in the level of the stream. There is no sight so sad as that of a drowned forest, with a turkey-buzzard on each bough. On the bank upon our left was an iron scaffold, eight or ten stories high,—“Butler‘s Lookout,” as the cleft was “Butler‘s Dutch Gap Canal.” The canal, unfinished in war, is now to be completed at State expense for purposes of trade.

As we rounded the extremity of the peninsula an eagle was seen to light upon a tree. From every portion of the ship—main deck, hurricane deck, lower deck ports—revolvers, ready capped and loaded, were brought to bear upon the bird, which sheered off unharmed amid a storm of bullets. After this incident, I was careful in my political discussions with my shipmates; disarmament in the Confederacy had clearly not been extended to private weapons.

The outer and inner lines of fortifications passed, we came in view of a many-steepled town, with domes and spires recalling Oxford, hanging on a bank above a crimson-colored foaming stream. In ten minutes we were alongside the wharf at Richmond, and in half an hour safely housed in the “Exchange Hotel,” kept by the Messrs. Carrington, of whom the father was a private, the son a colonel, in the rebel volunteers.

The next day, while the works and obstructions on the James were still fresh in my mind, I took train to Petersburg, the city the capture of which by Grant was the last blow struck by the North at the melting forces of the Confederacy.

The line showed the war: here and there the track, torn up in Northern raids, had barely been repaired; the bridges were burnt and broken; the rails worn down to an iron thread. The joke “on board,” as they say here for “in the train,” was that the engine-drivers down the line are tolerably cute men, who, when the rails are altogether worn away, understand how to “go it on the bare wood,” and who at all times “know where to jump.”

From the window of the car we could see that in the country there were left no mules, no horses, no roads, no men. The solitude is not all owing to the war: in the whole five and twenty miles from Richmond to Petersburg there was before the war but a single station; in New England your passage-card often gives a station in every two miles. A careful look at the underwood on either side the line showed that this forest is not primeval, that all this country had once been plowed.

Virginia stands first among the States for natural advantages: in climate she is unequaled; her soil is fertile; her mineral wealth in coal, copper, gold, and iron enormous, and well placed; her rivers good, and her great harbor one of the best in the world. Virginia has been planted more than two hundred and fifty years, and is as large as England, yet has a free population of only a million. In every kind of production she is miserably inferior to Missouri or Ohio, in most, inferior also to the infant States of Michigan and Illinois. Only a quarter of her soil is under cultivation, to half that of poor, starved New England, and the mines are deserted which were worked by the very Indians who were driven from the land as savages a hundred years ago.

There is no surer test of the condition of a country than the state of its highways. In driving on the main roads round Richmond, in visiting the scene of McClellan‘s great defeat on the Chickahominy at Mechanicsville and Malvern Hill, I myself, and an American gentleman who was with me, had to get out and lay the planks upon the bridges, and then sit upon them, to keep them down while the black coachman drove across. The best roads in Virginia are but ill kept “corduroys;” but, bad as are these, “plank roads” over which artillery have passed, knocking out every other plank, are worse by far; yet such is the main road from Richmond toward the west.

There is not only a scarcity of roads, but of railroads. A comparison of the railway system of Illinois and Indiana with the two lines of Kentucky or the one of Western Virginia or Louisiana, is a comparison of the South with the North, of slavery with freedom. Virginia shows already the decay of age, but is blasted by slavery rather than by war.

Passing through Petersburg, the streets of which were gay with the feathery-brown blooms of the Venetian sumach, but almost deserted by human beings, who have not returned to the city since they were driven out by the shot and shell of which their houses show the scars, we were soon in the rebel works. There are sixty miles of these works in all, line within line, three deep: alternations of sand-pits and sand-heaps, with here and there a tree-trunk pierced for riflemen, and everywhere a double row of chevaux de frise. The forts nearest this point were named by their rebel occupants Fort Hell and Fort Damnation. Tremendous works, but it needed no long interview with Grant to understand their capture. I had not been ten minutes in his office at Washington before I saw that the secret of his unvarying success lay in his unflinching determination: there is pith in the American conceit which reads in his initials, “U. S. G.,” “unconditional-surrender Grant.”

The works defending Richmond, hardly so strong as those of Petersburg, were attacked in a novel manner in the third year of the war. A strong body of Federal cavalry on a raid, unsupported by infantry or guns, came suddenly by night upon the outer lines of Richmond on the west. Something had led them to believe that the rebels were not in force, and with the strange aimless daring that animated both parties during the rebellion, they rode straight in along the winding road, unchallenged, and came up to the inner lines. There they were met by a volley which emptied a few saddles, and they retired, without even stopping to spike the guns in the outer works. Had they known enough of the troops opposed to them to have continued to advance, they might have taken Richmond, and held it long enough to have captured the rebel president and senate, and burned the great iron-works and ships. The whole of the rebel army had gone north, and even the home guard was camped out on the Chickahominy. The troops who fired the volley were a company of the “iron-works battalion,” boys employed at the founderies, not one of whom had ever fired a rifle before this night. They confessed themselves that “one minute more, and they‘d have run;” but the volley just stopped the enemy in time.

The spot where we first struck the rebel lines was that known as the Crater—the funnel-shaped cavity formed when Grant sprang his famous mine: 1500 men are buried in the hollow itself, and the bones of those smothered by the falling earth are working through the soil: 5000 negro troops were killed in this attack, and are buried round the hollow where they died, fighting as gallantly as they fought everywhere throughout the war. It is a singular testimony to the continuousness of the fire, that the still remaining subterranean passages show that in countermining the rebels came once within three feet of the mine, yet failed to hear the working parties. Thousands of old army shoes were lying on the earth, and negro boys were digging up bullets for old lead.

Within eighty yards of the Crater are the Federal investing lines, on which the trumpet-flower of our gardens was growing wild in deep rich masses. The negroes told me not to gather it, because they believe it scalds the hand. They call it “poison plant,” or “blister weed.” The blue-birds and scarlet tannagers were playing about the horn-shaped flowers.

Just within Grant‘s earthworks are the ruins of an ancient church, built, it is said, with bricks that were brought by the first colonists from England in 1614. About Norfolk, about Petersburg, and in the Shenandoah Valley, you cannot ride twenty miles through the Virginian forest without bursting in upon some glade containing a quaint old church, or a creeper-covered roofless palace of the Culpeppers, the Randolphs, or the Scotts. The county names have in them all a history. Taking the letter “B” alone, we have Barbour, Bath, Bedford, Berkeley, Boone, Botetourt, Braxton, Brooke, Brunswick, Buchanan, Buckingham. A dozen counties in the State are named from kings or princes. The slaveowning cavaliers whose names the remainder bear are the men most truly guilty of the late attempt made by their descendants to create an empire founded on disloyalty and oppression; but within sight of this old church of theirs at Petersburg, thirty-three miles of Federal outworks stand as a monument of how the attempt was crushed by the children of their New England brother-colonists.

The names of streams and hamlets in Virginia have often a quaint English ring. On the Potomac, near Harper‘s Ferry, I once came upon “Sir John‘s Run.” Upon my asking a tall, gaunt fellow, who was fishing, whether this was the spot on which the Knight of Windsor “larded the lean earth,” I got for sole answer: “Wall, don‘t know ’bout that, but it‘s a mighty fine spot for yellow-fin trout.” The entry to Virginia is characteristic. You sail between capes named from the sons of James I., and have fronting you the estuaries of two rivers called after the King and the Duke of York.

The old “F. F. V.’s,” the first families of Virginia, whose founders gave these monarchic names to the rivers and counties of the State, are far off now in Texas and California—those, that is, which were not extinct before the war. The tenth Lord Fairfax keeps a tiny ranch near San Francisco; some of the chief Denmans are also to be found in California. In all such cases of which I heard, the emigration took place before the war; Northern conquest could not be made use of as a plea whereby to escape the reproaches due to the slaveowning system. There is a stroke of justice in the fact that the Virginian oligarchy have ruined themselves in ruining their State; but the gaming hells of Farobankopolis, as Richmond once was called, have much for which to answer.

When the “burnt district” comes to be rebuilt, Richmond will be the most beautiful of all the Atlantic cities; while the water-power of the rapids of the James, and a situation at the junction of canal and river, secure for it a prosperous future.

The superb position of the State-house (which formed the rebel capitol), on the brow of a long hill, whence it overhangs the city and the James, has in it something of satire. The Parliament-house of George Washington‘s own State, the State-house, contains the famed statue set up by the general assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia to the hero‘s memory. Without the building stands the still more noteworthy bronze statue of the first President, erected jointly by all the States in the then Union. That such monuments should overlook the battle-fields of the war provoked by the secession from the Union of Washington‘s loved Virginia, is a fact full of the grim irony of history.

Hollywood, the cemetery of Richmond, is a place full of touching sad suggestion, and very beautiful, with deep shades and rippling streams. During the war, there were hospitals in Richmond for 20,000 men, and “always full,” they say. The Richmond men who were killed in battle were buried where they fell; but 8000 who died in hospital are buried here, and over them is placed a wooden cross, with the inscription in black paint, “Dead, but not forgotten.” In another spot lie the Union dead, under the shadow of the flag for which they died.

From Monroe‘s tomb the evening view is singularly soft and calm; the quieter and calmer for the drone in which are mingled the trills of the mocking-bird, the hoarse croaking of the bull-frog, the hum of the myriad fire-flies, that glow like summer lightning among the trees, the distant roar of the river, of which the rich red water can still be seen, beaten by the rocks into a rosy foam.

With the moment‘s chillness of the sunset breeze, the golden glory of the heavens fades into gray, and there comes quickly over them the solemn blueness of the Southern night. Thoughts are springing up of the many thousand unnamed graves, where the rebel soldiers lie unknown, when the Federal drums in Richmond begin sharply beating the rappel.

IN the back country of Virginia, and on the borders of North Carolina, it becomes clear that our common English notions of the negro and of slavery are nearer the truth than common notions often are. The London Christy Minstrels are not more given to bursts of laughter of the form “Yah! yah!” than are the plantation hands. The negroes upon the Virginia farms are not maligned by those who represent them as delighting in the contrasts of crimson and yellow, or emerald and sky-blue. I have seen them on a Sunday afternoon, dressed in scarlet waistcoats and gold-laced cravats, returning hurriedly from “meetin’,” to dance break-downs, and grin from ear to ear for hours at a time. What better should we expect from men to whom until just now it was forbidden, under tremendous penalties, to teach their letters?

Nothing can force the planters to treat negro freedom save from the comic side. To them the thing is too new for thought, too strange for argument; the ridiculous lies on the surface, and to this they turn as a relief. When I asked a planter how the blacks prospered under freedom, his answer was, “Ours don‘t much like it. You see, it necessitates monogamy. If I talk about the ‘responsibilities of freedom,’ Sambo says, ‘Dunno ’bout that; please, mass’ George: me want two wife.’” Another planter tells me, that the only change he can see in the condition of the negroes since they have been free is that formerly the supervision of the overseer forced them occasionally to be clean, whereas now nothing on earth can make them wash. He says that, writing lately to his agent, he received an answer to which there was the following postscript: “You ain‘t sent no sope. You had better send sope: niggers is certainly needing sope.”

It is easy to treat the negro question in this way; easy, on the other hand, to assert that since history fails us as a guide to the future of the emancipated blacks, we should see what time will bring, and meanwhile set down negroes as a monster class of which nothing is yet known, and, like the compilers of the Catalan map, say of places of which we have no knowledge, “Here be giants, cannibals, and negroes.” As long as we possess Jamaica, and are masters upon the African west coast, the negro question is one of moment to ourselves. It is one, too, of mightier import, for it is bound up with the future of the English in America. It is by no means a question to be passed over as a joke. There are five millions of negroes in the United States; juries throughout ten States of the Union are mainly chosen from the black race. The matter is not only serious, but full of interest, political, ethnological, historic.

In the South you must take nothing upon trust; believe nothing you are told. Nowhere in the world do “facts” appear so differently to those who view them through spectacles of yellow or of rose. The old planters tell you that all is ruin,—that they have but half the hands they need, and from each hand but a half day‘s work: the new men, with Northern energy and Northern capital, tell you that they get on very well.

The old Southern planters find it hard to rid themselves of their traditions; they cannot understand free blacks, and slavery makes not only the slaves but the masters shiftless. They have no cash, and the Metayer system gives rise to the suspicion of some fraud, for the negroes are very distrustful of the honesty of their former masters.

The worst of the evils that must inevitably grow out of the sudden emancipation of millions of slaves have not shown themselves as yet, in consequence of the great amount of work that has to be done in the cities of the South, in repairing the ruin caused during the war by fire and want of care, and in building places of business for the Northern capitalists. The negroes of Virginia and North Carolina have flocked down to the towns and ports by the thousand, and find in Norfolk, Richmond, Wilmington, and Fort Monroe employment for the moment. Their absence from the plantations makes labor dear up country, and this in itself tempts the negroes who remain on land to work sturdily for wages. Seven dollars a month—at the rate equal to one pound—with board and lodging, were being paid to black field hands on the corn and tobacco farms near Richmond. It is when the city works are over that the pressure will come, and it will probably end in the blacks largely pushing northward, and driving the Irish out of hotel service at New York and Boston, as they have done in Philadelphia and St. Louis.

Already the negroes are beginning to ask for land, and they complain loudly that none of the confiscated lands have been assigned to them. “Ef yer dun gib us de land, reckon de ole massas ’ll starb de niggahs,” was a plain, straightforward summary of the negro view of the negro question, given me by a white-bearded old “uncle” in Richmond, and backed by every black man within hearing in a chorus of “Dat‘s true, for shore;” but I found up the country that the planters are afraid to let the negroes own or farm for themselves the smallest plot of land, for fear that they should sell ten times as much as they grew, stealing their “crop” from the granaries of their employers.

At a farm near Petersburg, owned by a Northern capitalist, 1000 acres, which before emancipation had been tilled by one hundred slaves, now needed, I was told, but forty freedmen for their cultivation; but when I reached the place, I found that the former number included old people and women, while the forty were all hale men. The men were paid upon the tally system. A card was given them for each day‘s work, which was accepted at the plantation store in payment for goods supplied, and at the end of the month money was paid for the remaining tickets. The planters say that the field hands will not support their old people; but this means only that, like white folk, they try to make as much money as they can, and know that if they plead the wants of their wives and children, the whites will keep their aged people.

That the negro slaves were lazy, thriftless, unchaste, and thieves, is true; but it is as slaves, and not as negroes, that they were all these things; and, after all, the effects of slavery upon the slave are less terrible than its effects upon the master. The moral condition to which the planter class had been brought by slavery, shows out plainly in the speeches of the rebel leaders. Alexander H. Stephens, Vice-President of the Confederacy, declared in 1861 that “Slavery is the natural and moral condition of the negro.... I cannot permit myself to doubt,” he went on, “the ultimate success of a full recognition of this principle throughout the civilized and enlightened world ... negro slavery is in its infancy.”

There is reason to believe that the American negroes will justify the hopes of their friends; they have made the best of every chance that has been given them as yet; they were good soldiers, they are eager to learn their letters, they are steady at their work: in Barbadoes they are industrious and well conducted; in La Plata they are exemplary citizens. In America the colored laborer has had no motive to be industrious.

General Grant assured me of the great aptness at soldiering shown by the negro troops. In battle they displayed extraordinary courage, but if their officers were picked off they could not stand a charge; no more, he said, could their Southern masters. The power of standing firm after the loss of leaders is possessed only by regiments where every private is as good as his captain and colonel, such as the Northwestern and New England volunteers.

Before I left Richmond I had one morning found my way into a school for the younger blacks. There were as many present as the forms would hold—sixty, perhaps, in all—and three wounded New England soldiers, with pale, thin faces, were patiently teaching them to write. The boys seemed quick and apt enough, but they were very raw—only a week or two in the school. Since the time when Oberlin first proclaimed the potential equality of the race by admitting negroes as freely as white men and women to the college, the negroes have never been backward to learn.

It must not be supposed that the negro is wanting in abilities of a certain kind. Even in the imbecility of the Congo dance we note his unrivaled mimetic powers. The religious side of the negro character is full of weird suggestiveness; but superstition, everywhere the handmaid of ignorance, is rife among the black plantation hands. It is thought that the punishment with which the shameful rites of Obi-worship have been visited has proved, even in the City of New Orleans, insufficient to prevent them. Charges of witchcraft are as common in Virginia as in Orissa; in the Carolinas as in Central India the use of poison is often sought to work out the events foretold by some noted sorceress. In no direction can the matter be followed out to its conclusions without bringing us face to face with the sad fact that the faults of the plantation negro are every one of them traceable to the vices of the slavery system, and that the Americans of to-day are suffering beyond measure for evils for which our forefathers are responsible. We ourselves are not guiltless of wrong-doing in this matter: if it is still impossible openly to advocate slavery in England, it has, at least, become a habit persistently to write down freedom. We are no longer told that God made the blacks to be slaves, but we are bade remember that they cannot prosper under emancipation. All mention of Barbadoes is suppressed, but we have daily homilies on the condition of Jamaica. The negro question in America is briefly this: is there, on the one hand, reason to fear that, dollars applied to land decreasing while black mouths to be fed increase, the Southern States will become an American Jamaica? Is there, on the other hand, ground for the hope that the negroes may be found not incapable of the citizenship of the United States? The former of these two questions is the more difficult, and to some extent involves the latter: can cotton, can sugar, can rice, can coffee, can tobacco, be raised by white field hands? If not, can they be raised with profit by black free labor? Can co-operative planting, directed by negro over-lookers, possibly succeed, or must the farm be ruled by white capitalists, agents, and overseers?

It is asserted that the negro will not work without compulsion; but the same may be said of the European. There is compulsion of many kinds. The emancipated negro may still be forced to work—forced as the white man is forced in this and other lands, by the alternative, work or starve! This forcing, however, may not be confined to that which the laws of natural increase lead us to expect; it may be stimulated by bounties on immigration.

The negro is not, it would seem, to have a monopoly of Southern labor in this continent. This week we hear of three shiploads of Chinese coolies as just landed in Louisiana; and the air is thick with rumors of labor from Bombay, from Calcutta, from the Pacific Islands—of Eastern labor in its hundred shapes—not to speak of competition with the whites, now commencing with the German immigration into Tennessee.

The berries of this country are so large, so many, so full of juice, that alone they form a never-failing source of nourishment to an idle population. Three kinds of cranberries, American, pied, and English; two blackberries, huckleberries, high-bush and low-bush blueberries—the latter being the English bilberry—are among the best known of the native fruits. No one in this country, however idle he be, need starve. If he goes farther south, he has the banana, the true staff of life.

The terrible results of the plentiful possession of this tree are seen in Ceylon, at Panama, in the coastlands of Mexico, at Auckland in New Zealand. At Pitcairn‘s Island the plantain grove has beaten the missionary from the field; there is much lip-Christianity, but no practice to be got from a people who possess the fatal plant. The much-abused cocoa-nut cannot come near it as a devil‘s agent. The cocoa-palm is confined to a few islands and coast tracts—confined, too, to the tropics and sea-level; the plantain and banana extend over seventy-degrees of latitude, down to Botany Bay and King George‘s Sound, and up as far north as the Khyber Pass. The palm asks labor—not much, it is true; but still a few days’ hard work in the year in trenching, and climbing after the nuts. The plantain grows as a weed, and hangs down its bunches of ripe tempting fruit into your lap as you lie in its cool shade. The cocoanut-tree has a hundred uses, and urges men to work to make spirit from its juice, ropes, clothes, matting, bags, from its fiber, oil from the pulp; it creates an export trade which appeals to almost all men by their weakest side, in offering large and quick returns for a little work. John Ross‘s “Isle of Cocoas,” to the west of Java and south of Ceylon, yields him heavy gains; there are profits to be made upon the Liberian coast, and even in Southern India and Ceylon. The plantain will make nothing; you can eat it raw or fried, and that is all; you can eat it every day of your life without becoming tired of its taste; without suffering in your health, you can live on it exclusively. In the banana groves of Florida and Louisiana there lurks much trouble and danger to the American free States.

The negroes have hardly much chance in Virginia against the Northern capitalists, provided with white labor; but the States of Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, and South Carolina promise to be wholly theirs. Already they are flocking to places in which they have a majority of the people, and can control the municipalities, and defend themselves, if necessary, by force; but if the Southerners of the coast desert their country, the negroes will not have it to themselves, unless nature declares that they shall. New Englanders will pour in with capital and energy, and cultivate the land by free black or by coolie labor, if either will pay. If they do pay, competition will force the remaining blacks to work or starve.

The friends of the negro are not without a fear that the laborers will be too many for their work, for, while the older cotton States appear to be worn out, the new, such as Texas and Tennessee, will be reserved by public opinion to the whites. For the present the negroes will be masters in seven of the rebel States; but in Texas, white men—English, Germans, Danes—are growing cotton with success; and in Georgia and North Carolina, which contain mountain districts, the negro power is not likely to be permanent.

We may, perhaps, lay it down as a general principle that, when the negro can fight his way through opposition, and stand alone as a farmer or laborer, without the aid of private or State charity, then he should be protected in the position he has shown himself worthy to hold, that of a free citizen of an enlightened and laboring community. Where it is found that when his circumstances have ceased to be exceptional, the negro cannot live unassisted, there the Federal government may fairly and wisely step in and say, “We will not keep you; but we will carry you to Liberia or to Hayti, if you will.”

It is clear that the Southern negroes must be given a decisive voice in the appointment of the legislatures by which they are to be ruled, or that the North must be prepared to back up by force of opinion, or if need be, by force of arms, the Federal Executive, when it insists on the Civil Rights Bill being set in action at the South. Government through the negroes is the only way to avoid government through an army, which would be dangerous to the freedom of the North. It is safer for America to trust her slaves than to trust her rebels—safer to enfranchise than to pardon.

A reading and writing basis for the suffrage in the Southern States is an absurdity. Coupled with pardons to the rebels, it would allow the “boys in gray”—the soldiers of the Confederacy—to control nine States of the Union; it would render the education of the freedmen hopeless. For the moment, it would entirely disfranchise the negroes in six States, whereas it is exactly for the moment that negro suffrage is in these States necessary; while, if the rebels were admitted to vote, and the negroes excluded from the poll, the Southern representatives, united with the Copperhead wing of the Democratic party, might prove to be strong enough to repudiate the Federal debt. This is one of a dozen dangers.

An education basis for the suffrage, though pretended to be impartial, would be manifestly aimed against the negroes, and would perpetuate the antipathy of color to which the war is supposed to have put an end. To education such a provision would be a death-blow. If the negroes were to vote as soon as they could read, it is certain that the planters would take good care that they never should read at all.

That men should be able to examine into the details of politics is not entirely necessary to the working of representative government. It is sufficient that they should be competent to select men to do it for them. In the highest form of representative government, where all the electors are both intelligent, educated, and alive to the politics of the time, then the member returned must tend more and more to be a delegate. That has always been the case with the Northern and Western members in America, but never with those returned by the Southern States; and so it will continue, whether the Southern elections be decided by negroes or by “mean whites.”

In Warren County, Mississippi, near Vicksburg, is a plantation which belongs to Joseph Davis, the brother of the rebel president. This he has leased to Mr. Montgomery—once his slave—in order that an association of blacks may be formed to cultivate the plantation on co-operative principles. It is to be managed by a council elected by the community at large, and a voluntary poor-rate and embankment-rate are to be levied on the people by themselves.

It is only a year since the termination of the war, and the negroes are already in possession of schools, village corporations, of the Metayer system, of co-operative farms; all this tells of rapid advance, and the conduct and circulation of the New Orleans Tribune, edited and published by negroes, and selling 10,000 copies daily, and another 10,000 of the weekly issue, speaks well for the progress of the blacks. If the Montgomery experiment succeeds, their future is secure.

THE political forecasts and opinions which were given me upon plantations were, in a great measure, those indicated in my talk with the Norfolk “loafers.” On the history of the commencement of the rebellion there was singular unanimity. “Virginia never meant to quit the Union; we were cheated by those rascals of the South. When we did go out, we were left to do all the fighting. Why, sir, I‘ve seen a Mississippian division run away from a single Yankee regiment.”

As I heard much the same story from the North Carolinians that I met, it would seem as though there was little union among the seceding States. The legend upon the first of all the secession flags that were hoisted was typical of this devotion to the fortunes of the State: “Death to abolitionists; South Carolina goes it alone;” and during the whole war it was not the rebel colors, but the palmetto emblem, or other State devices, that the ladies wore.

About the war itself but little is said, though here and there I met a man who would tell camp stories in the Northern style. One planter, who had been “out” himself, went so far as to say to me: “Our officers were good, but considering that our rank and file were just ‘white trash,’ and that they had to fight regiments of New England Yankee volunteers, with all their best blood in the ranks, and Western sharpshooters together, it‘s only wonderful how we weren‘t whipped sooner.”

As for the future, the planter‘s policy is a simple one: “Reckon we‘re whipped, so we go in now for the old flag; only those Yankee rogues must give us the control of our own people.” The one result of the war has been, as they believe, the abolition of slavery; otherwise the situation is unchanged. The war is over, the doctrine of secession is allowed to fall into the background, and the ex-rebels claim to step once more into their former place, if, indeed, they admit that they ever left it.

Every day that you are in the South you come more and more to see that the “mean whites” are the controlling power. The landowners are not only few in number, but their apathy during the present crisis is surprising. The men who demand their readmission to the government of eleven States are unkempt, fierce-eyed fellows, not one whit better than the brancos of Brazil; the very men, strangely enough, who themselves, in their “Leavenworth constitution,” first began disfranchisement, declaring that the qualification for electors in the new State of Kansas should be the taking oath to uphold the infamous Fugitive Slave Law.

These “mean whites” were the men who brought about secession. The planters are guiltless of everything but criminal indifference to the deeds that were committed in their name. Secession was the act of a pack of noisy demagogues; but a false idea of honor brought round a majority of the Southern people, and the infection of enthusiasm carried over the remainder.

When the war sprang up, the old Southern contempt for the Yankees broke out into a fierce burst of joy, that the day had come for paying off old scores. “We hate them, sir,” said an old planter to me. “I wish to God that the Mayflower had sunk with all hands in Plymouth Bay.”

Along with this violence of language, there is a singular kind of cringing to the conquerors. Time after time I heard the complaint, “The Yanks treat us shamefully, I reckon. We come back to the Union, and give in on every point; we renounce slavery; we consent to forget the past; and yet they won‘t restore us to our rights.” Whenever I came to ask what they meant by “rights,” I found the same haziness that everywhere surrounds that word. The Southerners seem to think that men may rebel and fight to the death against their country, and then, being beaten, lay down their arms and walk quietly to the polls along with law-abiding citizens, secure in the protection of the Constitution which for years they have fought to subvert.

At Richmond I had a conversation which may serve as a specimen of what one hears each moment from the planters. An old gentleman with whom I was talking politics opened at me suddenly: “The Radicals are going to give the ballot to our niggers to strengthen their party, but they know better than to give it to their Northern niggers.”

D.—“But surely there‘s a difference in the cases.”

The Planter.—“You‘re right—there is; but not your way. The difference is, that the Northern niggers can read and write, and even lie with consistency, and ours can‘t.”

D.—“But there‘s the wider difference, that negro suffrage down here is a necessity, unless you are to rule the country that‘s just beaten you.”

The Planter.—“Well, there of course we differ. We rebs say we fought to take our State out of the Union. The Yanks beat us; so our States must still be in the Union. If so, why shouldn‘t our representatives be unconditionally admitted?”

Nearer to a conclusion we of course did not come, he declaring that no man ought to vote who had not education enough to understand the Constitution, I, that this was good prima facie evidence against letting him vote, but that it might be rebutted by the proof of a higher necessity for his voting. As a planter said to me, “The Southerners prefer soldier rule to nigger rule;” but it is not a question of what they prefer, but of what course is necessary for the safety of the Union which they fought to destroy.

Nowhere in the Southern States did I find any expectation of a fresh rebellion. It is only Englishmen who ask whether “the South” will not fight “once more.” The South is dead and gone; there can never be a “South” again, but only so many Southern States. “The South” meant simply the slave country; and slavery being dead, it is dead. Slavery gave us but two classes besides the negroes—planters and “mean whites.” The great planters were but a few thousand in number; they are gone to Canada, England, Jamaica, California, Colorado, Texas. The “mean whites”—the true South—are impossible in the face of free labor: they must work or starve. If they work, they will no longer be “mean whites,” but essentially Northerners—that is, citizens of a democratic republic, and not oligarchists.

As the Southerners admit that there can be no further war, it would be better even for themselves that they should allow the sad record of their rising to fade away. Their speeches, their newspapers continue to make use of language which nothing could excuse, and which, in the face of the magnanimity of the conquerors, is disgraceful. In a Mobile paper I have seen a leader which describes with hideous minuteness Lincoln, Lane, John Brown, and Dostie playing whist in hell. A Texas cutting which I have is less blasphemous, but not less vile: “The English language no longer affords terms in which to curse a sniveling, weazen-faced piece of humanity generally denominated a Yankee. We see some about here sometimes, but they skulk around, like sheep-killing dogs, and associate mostly with niggers. They whine and prate, and talk about the judgment of God, as if God had anything to do with them.” The Southerners have not even the wit or grace to admit that the men who beat them were good soldiers; “blackguards and braggarts,” “cravens and thieves,” are common names for the men of the Union army. I have in my possession an Alabama paper in which General Sheridan, at that time the commander of the military division which included the State, is styled “a short-tailed slimy tadpole of the later spawn, the blathering disgrace of an honest father, an everlasting libel on his Irish blood, the synonym of infamy, and scorn of all brave men.” While I was in Virginia, one of the Richmond papers said: “This thing of ‘loyalty’ will not do for the Southern man.”

The very day that I landed in the South a dinner was given at Richmond by the “Grays,” a volunteer corps which had fought through the rebellion. After the roll of honor, or list of men killed in battle, had been read, there were given as toasts by rebel officers: “Jeff. Davis—the caged eagle; the bars confine his person, but his great spirit soars;” and “The conquered banner, may its resurrection at last be as bright and as glorious as theirs—the dead.”

It is in the face of such words as these that Mr. Johnson, the most unteachable of mortals, asks men who have sacrificed their sons to restore the Union to admit the ex-rebels to a considerable share in the government of the nation, even if they are not to monopolize it, as they did before the war. His conduct seems to need the Western editor‘s defense: “He must be kinder honest-like, he aire sich a tarnation foolish critter.”

It is clear, from the occurrence of such dinners, the publication of such paragraphs and leaders as those of which I have spoken, that there is no military tyranny existing in the South. The country is indeed administered by military commanders, but it is not ruled by troops. Before we can give ear to the stories that are afloat in Europe of the “government of major-generals,” we must believe that five millions of Englishmen, inhabiting a country as large as Europe, are crushed down by some ten thousand other men—about as many as are needed to keep order in the single town of Warsaw. The Southerners are allowed to rule themselves; the question now at issue is merely whether they shall also rule their former slaves, the negroes.

I hardly felt myself out of the reach of slavery and rebellion till, steaming up the Potomac from Aquia Creek by the gray dawn, I caught sight of a grand pile towering over a city from a magnificent situation on the brow of a long, rolling hill. Just at the moment, the sun, invisible as yet to us below, struck the marble dome and cupola, and threw the bright gilding into a golden blaze, till the Greek shape stood out upon the blue sky, glowing like a second sun. The city was Washington; the palace with the burnished cupola the Capitol; and within two hours I was present at the “hot-weather sitting” of the 39th Congress of the United States.

AT the far southeast of New York City, where the Hudson and East River meet to form the inner bay, is an ill-kept park that might be made the loveliest garden in the world. Nowhere do the features that have caused New York to take rank as the first port of America stand forth more clearly. The soft evening breeze tells of a climate as good as the world can show; the setting sun floods with light a harbor secure and vast, formed by the confluence of noble streams, and girt with quays at which huge ships jostle; the rows of 500-pounder Rodmans at “The Narrows” are tokens of the nation‘s strength and wealth; and the yachts, as well handled as our own, racing into port from an ocean regatta, give evidence that there are Saxons in the land. At the back is the city, teeming with life, humming with trade, muttering with the thunder of passage. Opposite, in Jersey City, people say: “Every New Yorker has come a good half-hour late into the world, and is trying all his life to make it up.” The bustle is immense.

All is so un-English, so foreign, that hearing men speaking what Czar Nicholas was used to call “the American tongue,” I wheel round, crying—“Dear me! if here are not some English folk!” astonished as though I had heard French in Australia or Italian in Timbuctoo.

The Englishman who, coming to America, expects to find cities that smell of home, soon learns that Baker Street itself, or Portland Place, would not look English in the dry air of a continent four thousand miles across. New York, however, is still less English than is Boston, Philadelphia, or Chicago—her people are as little Saxon as her streets. Once Southern, with the brand of slavery deeply printed in the foreheads of her foremost men, since the defeat of the rebellion New York has to the eye been cosmopolitan as any city of the Levant. All nationless towns are not alike: Alexandria has a Greek or an Italian tinge; San Francisco an English tone, with something of the heartiness of our Elizabethan times; New York has a deep Latin shade, and the democracy of the Empire State is of the French, not of the American or English type.

At the back, here, on the city side, are tall gaunt houses, painted red, like those of the quay at Dort or of the Boompjes at Rotterdam, the former dwellings of the “Knickerbockers” of New Amsterdam, the founders of New York, but now forgotten. There may be a few square yards of painting, red or blue, upon the houses in Broadway; there may be here and there a pagoda summer-house overhanging a canal; once in a year you may run across a worthy descendant of the old Netherlandish families; but in the main the Hollanders in America are as though they had never been; to find the memorials of lost Dutch empire, we must search Cape Colony or Ceylon. The New York un-English tone is not Batavian. Neither the sons of the men who once lived in these houses, nor the Germans whose names are now upon the doors, nor, for the matter of that, we English, who claim New York as the second of our towns, are the to-day‘s New Yorkers.

Here, on the water‘s edge, is a rickety hall, where Jenny Lind sang when first she landed—now the spot where strangers of another kind are welcomed to America. Every true republican has in his heart the notion that his country is pointed out by God for a refuge for the distressed of all the nations. He has sprung himself from men who came to seek a sanctuary—from the Quakers, or the Catholics, or the pilgrims of the Mayflower. Even though they come to take the bread from his mouth, or to destroy his peace, it is his duty, he believes, to aid the immigrants. Within the last twenty years there have landed at New York alone four million strangers. Of these two-thirds were Irish.

While the Celtic men are pouring into New York and Boston, the New Englanders and New Yorkers, too, are moving. They are not dying. Facts are opposed to this portentous theory. They are going West. The unrest of the Celt is mainly caused by discontent with his country‘s present, that of the Saxon by hope for his private future. The Irishman flies to New York because it lies away from Ireland; the Englishman takes it upon his road to California.

Where one race is dominant, immigrants of another blood soon lose their nationality. In New York and Boston the Irish continue to be Celts, for these are Irish cities. In Pittsburg, in Chicago, still more in the country districts, a few years make the veriest Paddy English. On the other hand, the Saxons are disappearing from the Atlantic cities, as the Spaniards have gone from Mexico. The Irish here are beating down the English, as the English have crushed out the Dutch. The Hollander‘s descendants in New York are English now; it bids fair that the Saxons should be Irish.

As it is, though the Celtic immigration has lasted only twenty years, the results are already clear: if you see a Saxon face upon the Broadway, you may be sure it belongs to a traveler, or to some raw English lad bound West, just landed from a Plymouth ship. We need not lay much stress upon the fact that all New Yorkers have black hair and beard: men may be swarthy and yet English. The ancestors of the Londoners of to-day, we are told, were yellow-headed roysterers; yet not one man in fifty that you meet in Fleet Street or on Tower Hill is as fair as the average Saxon peasant. Doubtless, our English eastern counties were peopled in the main by low-Dutch and Flemings: the Sussex eyes and hair are rarely seen in Suffolk. The Puritans of New England are sprung from those of the “associated counties,” but the victors of Marston Moor may have been cousins to those no less sturdy Protestants, the Hollanders who defended Leyden. It may be that they were our ancestors, those Dutchmen that we English crowded out of New Amsterdam—the very place where we are sharing the fate we dealt. The fiery temper of the new people of the American coast towns, their impatience of free government, are better proofs of Celtic blood than are the color of their eyes and beard.

Year by year the towns grow more and more intensely Irish. Already of every four births in Boston, one only is American. There are 120,000 foreign to 70,000 native voters in New York and Brooklyn. Montreal and Richmond are fast becoming Celtic; Philadelphia—shades of Penn!—can only be saved by the aid of its Bavarians. Saxon Protestantism is departing with the Saxons: the revenues of the Empire State are spent upon Catholic asylums; plots of city land are sold at nominal rates for the sites of Catholic cathedrals, by the “city step-fathers,” as they are called. Not even in the West does the Latin Church gain ground more rapidly than in New York City: there are 80,000 professing Catholics in Boston.

When is this drama, of which the first scene is played in Castle Garden, to have its close? The matter is grave enough already. Ten years ago, the third and fourth cities of the world, New York and Philadelphia, were as English as our London: the one is Irish now; the other all but German. Not that the Quaker City will remain Teutonic: the Germans, too, are going out upon the land; the Irish alone pour in unceasingly. All great American towns will soon be Celtic, while the country continues English: a fierce and easily-roused people will throng the cities, while the law-abiding Saxons who till the land will cease to rule it. Our relations with America are matters of small moment by the side of the one great question: Who are the Americans to be?

Our kinsmen are by no means blind to the dangers that hang over them. The “Know-Nothing” movement failed, but Protection speaks the same voice in its opposition to commercial centers. If you ask a Western man why he, whose interest is clearly in Free Trade, should advocate Protection, he fires out: “Free Trade is good for our American pockets, but it‘s death to us Americans. All your Bastiats and Mills won‘t touch the fact that to us Free Trade must mean salt-water despotism, and the ascendency of New York and Boston. Which is better for the country—one New York, or ten contented Pittsburgs and ten industrious Lowells?”

The danger to our race and to the world from Irish ascendency is perhaps less imminent than that to the republic. In January, 1862, the mayor, Fernando Wood, the elect of the “Mozart” Democracy, deliberately proposed the secession from the Union of New York City. Of all the Northern States, New York alone was a dead weight upon the loyal people during the war of the rebellion. The constituents of Wood were the very Fenians whom in our ignorance we call “American.” It is America that Fenianism invades from Ireland—not England from America.

It is no unfair attack upon the Irish to represent them as somewhat dangerous inhabitants for mighty cities. Of the sixty thousand persons arrested yearly in New York, three-fourths are alien born: two-thirds of these are Irish. Nowhere else in all America are the Celts at present masters of a city government—nowhere is there such corruption. The purity of the government of Melbourne—a city more democratic than New York—proves that the fault does not lie in democracy: it is the universal opinion of Americans that the Irish are alone responsible.

The State legislature is falling into the hands of the men who control the city council. They tell a story of a traveler on the Hudson River Railroad, who, as the train neared Albany—the capital of New York—said to a somewhat gloomy neighbor, “Going to the State legislatur’?” getting for answer, “No, sir! It‘s not come to that with me yet. Only to the State prison!”

Americans are never slow to ridicule the denationalization of New York. They tell you that during the war the colonel of one of the city regiments said: “I‘ve the best blood of eight nations in the ranks.” “How‘s that?” “I‘ve English, Irish, Welsh, Scotch, French, Italians, Germans.” “Guess that‘s only seven.” “Swedes,” suggested some one. “No, no Swedes,” said the colonel. “Ah! I have it: I‘ve some Americans.” Stories such as this the rich New Yorkers are nothing loth to tell; but they take no steps to check the denationalization they lament. Instead of entering upon a reform of their municipal institutions, they affect to despise free government; instead of giving, as the oldest New England families have done, their tone to the State schools, they keep entirely aloof from school and State alike. Sending their boys to Cambridge, Berlin, Heidelberg, anywhere rather than to the colleges of their native land, they leave it to learned pious Boston to supply the West with teachers, and to keep up Yale and Harvard. Indignant if they are pointed at as “no Americans,” they seem to separate themselves from everything that is American: they spend summers in England, winters in Algeria, springs in Rome, and Coloradans say with a sneer, “Good New Yorkers go to Paris when they die.”

Apart from nationality, there is danger to free government both in the growth of New York City, and in the gigantic fortunes of New Yorkers. The income, they tell me, of one of my merchant friends is larger than the combined salaries of the president, the governors, and the whole of the members of the legislatures of all the forty-five States and territories. As my informant said, “He could keep the governments of half a dozen States as easily as I can support my half dozen children.”

There is something, no doubt, of the exaggeration of political jealousy about the accounts of New York vice given in New England and down South, in the shape of terrible philippics. It is to be hoped that the overstatement is enormous, for sober men are to be found even in New York who will tell you that this city outdoes Paris in every form of profligacy as completely as the French capital outherods imperial Rome. There is here no concealment about the matter; each inhabitant at once admits the truth of accusations directed against his neighbor. If the new men, the “petroleum aristocracy,” are second to none in their denunciations of the Irish, these in their turn unite with the oldest families in thundering against “Shoddy.”

New York life shows but badly in the summer-time; it is seen at its worst when studied at Saratoga. With ourselves, men have hardly ceased to run from business and pleasures worse than toil to the comparative quiet of the country house. Among New Yorkers there is not even the affectation of a search for rest; the flight is from the drives and restaurants of New York to the gambling halls of Saratoga; from winning piles of greenbacks to losing heaps of gold; from cotton gambling to roulette or faro. Long Branch is still more vulgar in its vice; it is the Margate, Saratoga the Homburg of America.

“Shoddy” is blamed beyond what it deserves when the follies of New York society are laid in a body at its door. If it be true that the New York drawing-rooms are the best guarded in the world, it is also true that entrance is denied as rigidly to intellect and eminence as to wealth. If exclusiveness be needed, affectation can at least do nothing toward subduing “Shoddy.” Mere cliqueism, disgusting every where, is ridiculous in a democratic town; its rules of conduct are as out of place as kid gloves in the New Zealand bush, or gold scabbards on a battle-field.

Good meat, and drink, and air, give strength to the men and beauty to the women of a moneyed class; but in America these things are the inheritance of every boy and girl, and give their owners no advantage in the world. During the rebellion, the ablest generals and bravest soldiers of the North sprang, not from the merchant families, but from the farmer folk. Without special merit of some kind, there can be no such thing as aristocracy.

Many American men and women, who have too little nobility of soul to be patriots, and too little understanding to see that theirs is already, in many points, the master country of the globe, come to you, and bewail the fate which has caused them to be born citizens of a republic, and dwellers in a country where men call vices by their names. The least educated of their countrymen, the only grossly vulgar class that America brings forth, they fly to Europe “to escape democracy,” and pass their lives in Paris, Pau, or Nice, living libels on the country they are believed to represent.

Out of these discordant elements, Cubans, Knickerbockers, Germans, Irish, “first families,” “Petroleum,” and “Shoddy,” we are forced to construct our composite idea—New York. The Irish numerically predominate, but we have no experience as to what should be the moral features of an Irish city, for Dublin has always been in English hands; possibly that which in New York appears to be cosmopolitan is merely Celtic. However it may be, this much is clear, that the humblest township of New England reflects more truly the America of the past, the most chaotic village of Nebraska portrays more fully the hopes and tendencies of the America of the future, than do this huge State and city.

If the political figure of New York is not encouraging, its natural beauty is singularly great. Those who say that America has no scenery, forget the Hudson, while they can never have explored Lake George, Lake Champlain, and the Mohawk. That Poole‘s exquisite scene from the “Decameron,” “Philomela‘s Song,” could have been realized on earth, I never dreamt until I saw the singers at a New Yorker‘s villa on the Hudson grouped in the deep shades of a glen, from which there was an outlook upon the basaltic palisades and lake-like Tappan Zee. It was in some such spot that De Tocqueville wrote the brightest of his brilliant letters—that dated “Sing Sing”—for he speaks of himself as lying on a hill that overhung the Hudson, watching the white sails gleaming in the hot sun, and trying in vain to fancy what became of the river where it disappeared in the blue “Highlands.”

That New York City itself is full of beauty the view from Castle Garden would suffice to show; and by night it is not less lovely than by day. The harbor is illuminated by the colored lanterns of a thousand boats, and the steam-whistles tell of a life that never sleeps. The paddles of the steamers seem not only to beat the water, but to stir the languid air and so provoke a breeze, and the lime-lights at the Fulton and Wall Street ferries burn so brightly that in the warm glare the eye reaches through the still night to the feathery acacias in the streets of Brooklyn. The view is as southern as the people: we have not yet found America.

“OLD CAMBRIDGE! Long may she flourish!” proposed by a professor in the University of Cambridge, in America, and drunk standing, with three cheers, by the graduates and undergraduates of Harvard, is a toast that sets one thinking.

Cambridge in America is not by any means a university of to-day. Harvard College, which, being the only “house,” has engrossed the privileges, funds, and titles of the university, was founded at Cambridge, Mass., in 1636, only ninety years later than the greatest and wealthiest college of our Cambridge in old England. Puritan Harvard was the sister rather than the daughter of our own Puritan Emmanuel. Harvard himself, and Dunster, the first president of Harvard‘s College, were among the earliest of the scholars of Emmanuel.

A toast from the Cambridge of new to the Cambridge of old England is one from younger to elder sister; and Dr. Wendell Holmes, “The Autocrat,” said as much in proposing it at the Harvard alumni celebration of 1866.

Like other old institutions, Harvard needs a ten-days’ revolution: academic abuses flourish as luxuriantly upon American as on English soil, and university difficulties are much the same in either country. Here, as at home, the complaint is that the men come up to the university untaught. To all of them their college is forced for a time to play the high-school; to some she is never anything more than school. At Harvard this is worse than with ourselves: the average age of entry, though of late much risen, is still considerably under eighteen.

The college is now aiming at raising gradually the standard of entry: when once all are excluded save men, and thinking men, real students, such as those by whom some of the new Western universities are attended, then Harvard hopes to leave drill-teaching entirely to the schools, and to permit the widest freedom in the choice of studies to her students.

Harvard is not blameless in this matter. Like other universities, she is conservative of bad things as well as good; indeed, ten minutes within her walls would suffice to convince even an Englishman that Harvard clings to the times before the Revolution.

Her conservatism is shown in many trivial things—in the dress of her janitors and porters, in the cut of the grass-plots and college gates, in the conduct of the Commencement orations in the chapel. For the dainty little dames from Boston who came to hear their friends and brothers recite their disquisitions none but Latin programmes were provided, and the poor ladies were condemned to find such names as Bush, Maurice, Benjamin, Humphrey, and Underwood among the graduating youths, distorted into Bvsh, Mavritivs, Beniamin, Hvmphredvs, Vnderwood.

This conservatism of the New England universities had just received a sharp attack. In the Commencement oration, Dr. Hedges, one of the leaders of the Unitarian Church, had strongly pressed the necessity for a complete freedom of study after entry, a liberty to take up what line the student would, to be examined and to graduate in what he chose. He had instanced the success of Michigan University consequent upon the adoption of this plan; he had pointed to the fact that of all the universities in America, Michigan alone drew her students from every State. President Hill and ex-President Walker had indorsed his views.

There is a special fitness in the reformers coming forward at this time. This year is the commencement of a new era at Harvard, for at the request of the college staff, the connection of the university with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has just been dissolved, and the members of the board of overseers are in future to be elected by the university, instead of being nominated by the State. This being so, the question had been raised as to whether the governor would come in state to Commencement, but he yielded to the wishes of the graduates, and came with the traditional pomp, attended by a staff in uniform, and escorted by a troop of Volunteer Lancers, whose scarlet coats and polish recalled the times before the Revolution.