This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Ravenshoe

Author: Henry Kingsley

Release Date: December 16, 2012 [eBook #41636]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAVENSHOE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/ravenshoe00kingiala |

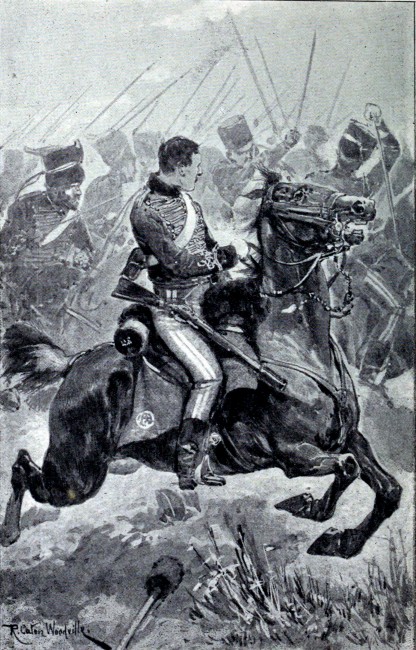

CHARLES IN THE BALACLAVA CHARGE.

CHARLES IN THE BALACLAVA CHARGE.

LONDON

WARD, LOCK AND BOWDEN, LIMITED

WARWICK HOUSE, SALISBURY SQUARE, E.C.

NEW YORK AND MELBOURNE

1894

[All rights reserved]

To

MY BROTHER,

CHARLES KINGSLEY,

I DEDICATE THIS TALE,

IN TOKEN OF A LOVE WHICH ONLY GROWS STRONGER

AS WE BOTH GET OLDER.

The language used in telling the following story is not (as I hope the reader will soon perceive) the Author's, but Mr. William Marston's.

The Author's intention was, while telling the story, to develop, in the person of an imaginary narrator, the character of a thoroughly good-hearted and tolerably clever man, who has his fingers (as he would say himself) in every one's pie, and who, for the life of him, cannot keep his own counsel—that is to say, the only person who, by any possibility, could have collected the mass of family gossip which makes up this tale.

Had the Author told it in his own person, it would have been told with less familiarity, and, as he thinks, you would not have laughed quite so often.

PAGE

CHAPTER I

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FAMILY OF RAVENSHOE 1

CHAPTER II.

SUPPLEMENTARY TO THE FOREGOING 10

CHAPTER III.

IN WHICH OUR HERO'S TROUBLES BEGIN 14

CHAPTER IV.

FATHER MACKWORTH 20

CHAPTER V.

RANFORD 23

CHAPTER VI.

THE "WARREN HASTINGS" 34

CHAPTER VII.

IN WHICH CHARLES AND LORD WELTER DISTINGUISH

THEMSELVES AT THE UNIVERSITY 44

CHAPTER VIII.

[Pg x]JOHN MARSTON 50

CHAPTER IX.

ADELAIDE 57

CHAPTER X.

LADY ASCOT'S LITTLE NAP 63

CHAPTER XI.

GIVES US AN INSIGHT INTO CHARLES'S DOMESTIC RELATIONS,

AND SHOWS HOW THE GREAT CONSPIRATOR

SOLILOQUISED TO THE GRAND CHANDELIER 69

CHAPTER XII.

CONTAINING A SONG BY CHARLES RAVENSHOE, AND ALSO

FATHER TIERNAY'S OPINION ABOUT THE FAMILY 79

CHAPTER XIII.

THE BLACK HARE 86

CHAPTER XIV.

LORD SALTIRE'S VISIT, AND SOME OF HIS OPINIONS 92

CHAPTER XV.

CHARLES'S "LIDDELL AND SCOTT" 99

CHAPTER XVI.

MARSTON'S ARRIVAL 104

CHAPTER XVII.

IN WHICH THERE IS ANOTHER SHIPWRECK 107

CHAPTER XVIII.

MARSTON'S DISAPPOINTMENT 114

CHAPTER XIX.

[Pg xi]ELLEN'S FLIGHT 121

CHAPTER XX.

RANFORD AGAIN 124

CHAPTER XXI.

CLOTHO, LACHESIS, AND ATROPOS 131

CHAPTER XXII.

THE LAST GLIMPSE OF OXFORD 139

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE LAST GLIMPSE OF THE OLD WORLD 142

CHAPTER XXIV.

THE FIRST GLIMPSE OF THE NEW WORLD 146

CHAPTER XXV.

FATHER MACKWORTH BRINGS LORD SALTIRE TO BAY, AND WHAT CAME OF IT 152

CHAPTER XXVI.

THE GRAND CRASH 160

CHAPTER XXVII.

THE COUP DE GRACE 167

CHAPTER XXVIII.

FLIGHT 176

CHAPTER XXIX.

CHARLES'S RETREAT UPON LONDON 180

CHAPTER XXX.

MR. SLOANE 185

CHAPTER XXXI.

[Pg xii]LIEUTENANT HORNBY 190

CHAPTER XXXII.

SOME OF THE HUMOURS OF A LONDON MEWS. 194

CHAPTER XXXIII.

A GLIMPSE OF SOME OLD FRIENDS 200

CHAPTER XXXIV.

IN WHICH FRESH MISCHIEF IS BREWED 203

CHAPTER XXXV.

IN WHICH AN ENTIRELY NEW, AND, AS WILL BE SEEN

HEREAFTER, A MOST IMPORTANT CHARACTER IS

INTRODUCED 211

CHAPTER XXXVI.

THE DERBY 219

CHAPTER XXXVII.

LORD WELTER'S MÉNAGE 227

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

THE HOUSE FULL OF GHOSTS 235

CHAPTER XXXIX.

CHARLES'S EXPLANATION WITH LORD WELTER 242

CHAPTER XL.

A DINNER PARTY AMONG SOME OLD FRIENDS 246

CHAPTER XLI.

CHARLES'S SECOND EXPEDITION TO ST. JOHN'S WOOD 252

CHAPTER XLII.

RAVENSHOE HALL, DURING ALL THIS 261

CHAPTER XLIII.

[Pg xiii]THE MEETING 270

CHAPTER XLIV.

ANOTHER MEETING 275

CHAPTER XLV.

HALF A MILLION 285

CHAPTER XLVI.

TO LUNCH WITH LORD ASCOT 288

CHAPTER XLVII.

LORD HAINAULT'S BLOTTING-BOOK 302

CHAPTER XLVIII.

IN WHICH CUTHBERT BEGINS TO SEE THINGS IN A NEW LIGHT 309

CHAPTER XLIX.

THE SECOND COLUMN OF "THE TIMES" OF THIS DATE, WITH OTHER MATTERS 317

CHAPTER L.

SHREDS AND PATCHES 320

CHAPTER LI.

IN WHICH CHARLES COMES TO LIFE AGAIN 327

CHAPTER LII.

WHAT LORD SALTIRE AND FATHER MACKWORTH SAID

WHEN THEY LOOKED OUT OF THE WINDOW 335

CHAPTER LIII.

CAPTAIN ARCHER TURNS UP 343

CHAPTER LIV.

CHARLES MEETS HORNBY AT LAST 349

CHAPTER LV.

[Pg xiv]ARCHER'S PROPOSAL 358

CHAPTER LVI.

SCUTARI 369

CHAPTER LVII.

WHAT CHARLES DID WITH HIS LAST EIGHTEEN SHILLINGS 374

CHAPTER LVIII.

THE NORTH SIDE OF GROSVENOR SQUARE 379

CHAPTER LIX.

LORD ASCOT'S CROWNING ACT OF FOLLY 391

CHAPTER LX.

THE BRIDGE AT LAST 400

CHAPTER LXI.

SAVED 411

CHAPTER LXII.

MR. JACKSON'S BIG TROUT 415

CHAPTER LXIII.

IN WHICH GUS CUTS FLORA'S DOLL'S CORNS 420

CHAPTER LXIV.

THE ALLIED ARMIES ADVANCE ON RAVENSHOE 423

CHAPTER LXV.

FATHER MACKWORTH PUTS THE FINISHING TOUCH ON

HIS GREAT PIECE OF EMBROIDERY 427

CHAPTER LXVI.

GUS AND FLORA ARE NAUGHTY IN CHURCH, AND THE

WHOLE BUSINESS COMES TO AN END 438

I had intended to have gone into a family history of the Ravenshoes, from the time of Canute to that of her present Majesty, following it down through every change and revolution, both secular and religious; which would have been deeply interesting, but which would have taken more hard reading than one cares to undertake for nothing. I had meant, I say, to have been quite diffuse on the annals of one of our oldest commoner families; but, on going into the subject, I found I must either chronicle little affairs which ought to have been forgotten long ago, or do my work in a very patchy and inefficient way. When I say that the Ravenshoes have been engaged in every plot, rebellion, and civil war, from about a century or so before the Conquest to 1745, and that the history of the house was marked by cruelty and rapacity in old times, and in those more modern by political tergiversation of the blackest dye, the reader will understand why I hesitate to say too much in reference to a name which I especially honour. In order, however, that I may give some idea of what the hereditary character of the family is, I must just lead the reader's eye lightly over some of the principal events of their history.

The great Irish families have, as is well known, a banshee, or familiar spirit, who, previous to misfortune or death, flits moaning round the ancestral castle. Now although the Ravenshoes, like all respectable houses, have an hereditary lawsuit; a feud (with the Humbys of Hele); a ghost (which the present Ravenshoe claims to have repeatedly seen in early youth); and a buried treasure: yet I have never heard that they had a banshee. Had such been the case, that unfortunate spirit would have had no[Pg 2] sinecure of it, but rather must have kept howling night and day for nine hundred years or so, in order to have got through her work at all. For the Ravenshoes were almost always in trouble, and yet had a facility of getting out again, which, to one not aware of the cause, was sufficiently inexplicable. Like the Stuarts, they had always taken the losing side, and yet, unlike the Stuarts, have always kept their heads on their shoulders, and their house over their heads. Lady Ascot says that, if Ambrose Ravenshoe had been attainted in 1745, he'd have been hung as sure as fate: there was evidence enough against him to hang a dozen men. I myself, too, have heard Squire Densil declare, with great pride, that the Ravenshoe of King John's time was the only Baron who did not sign Magna Charta; and if there were a Ravenshoe at Runnymede, I have not the slightest doubt that such was the case. Through the Rose wars, again, they were always on the wrong side, whichever that might have been, because your Ravenshoe, mind you, was not bound to either side in those times, but changed as he fancied fortune was going. As your Ravenshoe was the sort of man who generally joined a party just when their success was indubitable—that is to say, just when the reaction against them was about to set in—he generally found himself among the party which was going down hill, who despised him for not joining them before, and opposed to the rising party, who hated him because he had declared against them. Which little game is common enough in this present century among some men of the world, who seem, as a general rule, to make as little by it as ever did the Ravenshoes.

Well, whatever your trimmers make by their motion nowadays, the Ravenshoes were not successful either at liberal conservatism or conservative liberalism. At the end of the reign of Henry VII. they were as poor as Job, or poorer. But, before you have time to think of it, behold, in 1530, there comes you to court a Sir Alured Ravenshoe, who incontinently begins cutting in at the top of the tune, swaggering, swearing, dressing, fighting, dicing, and all that sort of thing, and, what is more, paying his way in a manner which suggests successful burglary as the only solution. Sir Alured, however, as I find, had done no worse than marry an old maid (Miss Hincksey, one of the Staffordshire Hinckseys) with a splendid fortune; which fortune set the family on its legs again for some generations. This Sir Alured seems to have been an audacious rogue. He made great interest with the king, who was so far pleased with his activity in athletic sports that he gave him a post in Ireland. There our Ravenshoe was so fascinated by the charming manners of the[Pg 3] Earl of Kildare that he even accompanied that nobleman on a visit to Desmond; and, after a twelvemonth's unauthorised residence in the interior of Ireland, on his return to England he was put into the Tower for six months to "consider himself."

This Alured seems to have been a deuce of a fellow, a very good type of the family. When British Harry had that difference we wot of with the Bishop of Rome, I find Alured to have been engaged in some five or six Romish plots, such as had the king been in possession of facts, would have consigned him to a rather speedy execution. However, the king seems to have looked on this gentleman with a suspicious eye, and to have been pretty well aware what sort of man he was, for I find him writing to his wife, on the occasion of his going to court—"The King's Grace looked but sourly upon me, and said it should go hard, but that the pitcher which went so oft to the well should be broke at last. Thereto I making answer, 'that that should depend on the pitcher, whether it were iron or clomb,' he turned on his heel, and presently departed from me."

He must have been possessed of his full share of family audacity to sharpen his wits on the terrible Harry, with such an unpardonable amount of treason hanging over him. I have dwelt thus long on him, as he seems to have possessed a fair share of the virtues and vices of his family—a family always generous and brave, yet always led astray by bad advisers. This Alured built Ravenshoe House, as it stands to this day, and in which much of the scene of this story is laid.

They seem to have got through the Gunpowder Plot pretty well, though I can show you the closet where one of the minor conspirators, one Watson, lay perdu for a week or so after that gallant attempt, more I suspect from the effect of a guilty conscience than anything else, for I never heard of any distinct charge being brought against him. The Forty-five, however, did not pass quite so easily, and Ambrose Ravenshoe went as near to lose his head as any one of the family since the Conquest. When the news came from the north about the alarming advance of the Highlanders, it immediately struck Ambrose that this was the best opportunity for making a fool of himself that could possibly occur. He accordingly, without hesitation or consultation with any mortal soul, rang the bell for his butler, sent for his stud-groom, mounted every man about the place (twenty or so), armed them, grooms, gardeners, and all, with crossbows and partisans from the armoury, and rode into the cross, at Stonnington, on a market-day, and boldly proclaimed the Pretender king. It soon got about that "the squire" was making a fool of himself, and that[Pg 4] there was some fun going; so he shortly found himself surrounded by a large and somewhat dirty rabble, who, with cries of "Well done, old rebel!" and "Hurrah for the Pope!" escorted him, his terror-stricken butler and his shame-stricken grooms, to the Crown and Sceptre. As good luck would have it, there happened to be in the town that day no less a person than Lord Segur, the leading Roman Catholic nobleman of the county. He, accompanied by several of the leading gentlemen of the same persuasion, burst into the room where the Squire sat, overpowered him, and, putting him bound into a coach, carried him off to Segur Castle, and locked him up. It took all the strength of the Popish party to save him from attainder. The Church rallied right bravely round the old house, which had always assisted her with sword and purse, and never once had wavered in its allegiance. So while nobler heads went down, Ambrose Ravenshoe's remained on his shoulders.

Ambrose died in 1759.

John (Monseigneur) in 1771.

Howard in 1800. He first took the Claycomb hounds.

Petre in 1820. He married Alicia, only daughter of Charles, third Earl of Ascot, and was succeeded by Densil, the first of our dramatis personæ—the first of all this shadowy line that we shall see in the flesh. He was born in the year 1783, and married, first in 1812, at his father's desire, a Miss Winkleigh, of whom I know nothing; and second, at his own desire, in 1823, Susan, fourth daughter of Lawrence Petersham, Esq., of Fairford Grange, county Worcester, by whom he had issue—

Cuthbert, born 1826;

Charles, born 1831.

Densil was an only son. His father, a handsome, careless, good-humoured, but weak and superstitious man, was entirely in the hands of the priests, who during his life were undisputed masters of Ravenshoe. Lady Alicia was, as I have said, a daughter of Lord Ascot, a Staunton, as staunchly a Protestant a house as any in England. She, however, managed to fall in love with the handsome young Popish Squire, and to elope with him, changing not only her name, but, to the dismay of her family, her faith also, and becoming, pervert-like, more actively bigoted than her easy-going husband. She brought little or no money into the family; and, from her portrait, appears to have been exceedingly pretty, and monstrously silly.

To this strong-minded couple was born, two years after their marriage, a son who was called Densil.

This young gentleman seems to have got on much like other[Pg 5] young gentlemen till the age of twenty-one, when it was determined by the higher powers in conclave assembled that he should go to London, and see the world; and so, having been cautioned duly how to avoid the flesh and the devil, to see the world he went. In a short time intelligence came to the confessor of the family, and through him to the father and mother, that Densil was seeing the world with a vengeance; that he was the constant companion of the Right Honourable Viscount Saltire, the great dandy of the Radical Atheist set, with whom no man might play picquet and live; that he had been upset in a tilbury with Mademoiselle Vaurien of Drury-lane at Kensington turnpike; that he had fought the French émigré, a Comte de Hautenbas, apropos of the Vaurien aforementioned—in short, that he was going on at a deuce of a rate: and so a hurried council was called to deliberate what was to be done.

"He will lose his immortal soul," said the priest.

"He will dissipate his property," said his mother.

"He will go to the devil," said his father.

So Father Clifford, good man, was despatched to London, with post horses, and ordered to bring back the lost sheep vi et armis. Accordingly, at ten o'clock one night, Densil's lad was astounded by having to admit Father Clifford, who demanded immediately to be led to his master.

Now this was awkward, for James well knew what was going on upstairs; but he knew also what would happen, sooner or later, to a Ravenshoe servant who trifled with a priest, and so he led the way.

The lost sheep which the good father had come to find was not exactly sober this evening, and certainly not in a very good temper. He was playing écarté with a singularly handsome, though supercilious-looking man, dressed in the height of fashion, who, judging from the heap of gold beside him, had been winning heavily. The priest trembled and crossed himself—this man was the terrible, handsome, wicked, witty, Atheistical, radical Lord Saltire, whose tongue no woman could withstand, and whose pistol no man dared face; who was currently believed to have sold himself to the deuce, or, indeed, as some said, to be the deuce himself.

A more cunning man than poor simple Father Clifford would have made some common-place remark and withdrawn, after a short greeting, taking warning by the impatient scowl that settled on Densil's handsome face. Not so he. To be defied by a boy whose law had been his word for ten years past never entered into his head, and he sternly advanced towards the pair.

Densil inquired if anything were the matter at home. And Lord Saltire, anticipating a scene, threw himself back in his chair, stretched out his elegant legs, and looked on with the air of a man who knows he is going to be amused, and composes himself thoroughly to appreciate the entertainment.

"Thus much, my son," said the priest; "your mother is wearing out the stones of the oratory with her knees, praying for her first-born, while he is wasting his substance, and perilling his soul, with debauched Atheistic companions, the enemies of God and man."

Lord Saltire smiled sweetly, bowed elegantly, and took snuff.

"Why do you intrude into my room, and insult my guest?" said Densil, casting an angry glance at the priest, who stood calmly like a black pillar, with his hands before him. "It is unendurable."

"Quem Deus vult," &c. Father Clifford had seen that scowl once or twice before, but he would not take warning. He said—

"I am ordered not to go westward without you. I command you to come."

"Command me! command a Ravenshoe!" said Densil, furiously.

Father Clifford, by way of mending matters, now began to lose his temper.

"You would not be the first Ravenshoe who has been commanded by a priest; ay, and has had to obey too," said he.

"And you will not be the first jack-priest who has felt the weight of a Ravenshoe's wrath," replied Densil, brutally.

Lord Saltire leant back, and said to the ambient air, "I'll back the priest, five twenties to one."

This was too much. Densil would have liked to quarrel with Saltire, but that was death—he was the deadest shot in Europe. He grew furious, and beyond all control. He told the priest to go (further than purgatory); grew blasphemous, emphatically renouncing the creed of his forefathers, and, in fact, all other creeds. The priest grew hot and furious too, retaliated in no measured terms, and finally left the room with his ears stopped, shaking the dust off his feet as he went. Then Lord Saltire drew up to the table again, laughing.

"Your estates are entailed, Ravenshoe, I suppose?" said he.

"No."

"Oh! It's your deal, my dear fellow."

Densil got an angry letter from his father in a few days, demanding full apologies and recantations, and an immediate return home. Densil had no apologies to make, and did not[Pg 7] intend to return till the end of the season. His father wrote declining the honour of his further acquaintance, and sending him a draft for fifty pounds to pay outstanding bills, which he very well knew amounted to several thousands. In a short time the great Catholic tradesmen, with whom he had been dealing, began to press for money in a somewhat insolent way; and now Densil began to see that, by defying and insulting the faith and the party to which he belonged, he had merely cut himself off from rank, wealth, and position. He had defied the partie prêtre, and had yet to feel their power. In two months he was in the Fleet prison.

His servant (the title "tiger" came in long after this), a half groom, half valet, such as men kept in those days—a simple lad from Ravenshoe, James Horton by name—for the first time in his life disobeyed orders; for, on being told to return home by Densil, he firmly declined doing so, and carried his top boots and white neckcloth triumphantly into the Fleet, there pursuing his usual avocations with the utmost nonchalance.

"A very distinguished fellow that of yours, Curly" (they all had nicknames for one another in those days), said Lord Saltire. "If I were not Saltire, I think I would be Jim. To own the only clean face among six hundred fellow-creatures is a pre-eminence, a decided pre-eminence. I'll buy him of you."

For Lord Saltire came to see him, snuff-box and all. That morning Densil was sitting brooding in the dirty room with the barred windows, and thinking what a wild free wind would be sweeping across the Downs this fine November day, when the door was opened, and in walks me my lord, with a sweet smile on his face.

He was dressed in the extreme of fashion—a long-tailed blue coat with gold buttons, a frill to his shirt, a white cravat, a wonderful short waistcoat, loose short nankeen trousers, low shoes, no gaiters, and a low-crowned hat. I am pretty correct, for I have seen his picture, dated 1804. But you must please to remember that his lordship was in the very van of the fashion, and that probably such a dress was not universal for two or three years afterwards. I wonder if his well-known audacity would be sufficient to make him walk along one of the public thoroughfares in such a dress, to-morrow, for a heavy bet—I fancy not.

He smiled sardonically—"My dear fellow," he said, "when a man comes on a visit of condolence, I know it is the most wretched taste to say, 'I told you so;' but do me the justice to allow that I offered to back the priest five to one. I had been coming to you all the week, but Tuesday and Wednesday I was[Pg 8] at Newmarket; Thursday I was shooting at your cousin Ascot's: yesterday I did not care about boring myself with you; so I have come to-day because I was at leisure and had nothing better to do."

Densil looked up savagely, thinking he had come to insult him: but the kindly compassionate look in the piercing grey eye belied the cynical curl of the mouth, and disarmed him. He leant his head upon the table and sobbed.

Lord Saltire laid his hand kindly on his shoulder, and said—

"You have been a fool, Ravenshoe; you have denied the faith of your forefathers. Pardieu, if I had such an article I would not have thrown it so lightly away."

"You talk like this? Who next? It was your conversation led me to it. Am I worse than you? What faith have you, in God's name?"

"The faith of a French Lycée, my friend; the only one I ever had. I have been sufficiently consistent to that, I think."

"Consistent indeed," groaned poor Densil.

"Now, look here," said Saltire; "I may have been to blame in this. But I give you my honour, I had no more idea that you would be obstinate enough to bring matters to this pass, than I had that you would burn down Ravenshoe House because I laughed at it for being old-fashioned. Go home, my poor little Catholic pipkin, and don't try to swim with iron pots like Wrekin and me. Make submission to that singularly distingué-looking old turkey-cock of a priest, kiss your mother, and get your usual autumn's hunting and shooting."

"Too late! too late, now!" sobbed Densil.

"Not at all, my dear fellow," said Saltire, taking a pinch of snuff; "the partridges will be a little wild of course—that you must expect; but you ought to get some very pretty pheasant and cock-shooting. Come, say yes. Have your debts paid, and get out of this infernal hole. A week of this would tame the devil, I should think."

"If you think you could do anything for me, Saltire."

Lord Saltire immediately retired, and re-appeared, leading in a lady by her hand. She raised the veil from her head, and he saw his mother. In a moment she was crying on his neck; and, as he looked over her shoulder, he saw a blue coat passing out of the door, and that was the last of Lord Saltire for the present.

It was no part of the game of the priests to give Densil a cold welcome home. Twenty smiling faces were grouped in the porch to welcome him back; and among them all none smiled more brightly than the old priest and his father. The dogs went wild[Pg 9] with joy, and his favourite peregrine scolded on the falconer's wrist, and struggled with her jesses, shrilly reminding him of the merry old days by the dreary salt marsh, or the lonely lake.

The past was never once alluded to in any way by any one in the house. Old Squire Petre shook hands with faithful James, and gave him a watch, ordering him to ride a certain colt next day, and see how well forward he could get him. So next day they drew the home covers, and the fox, brave fellow, ran out to Parkside, making for the granite walls of Hessitor. And, when Densil felt his nostrils filled once more by the free rushing mountain air, he shouted aloud for joy, and James's voice alongside of him said—

"This is better than the Fleet, sir."

And so Densil played a single-wicket match with the Holy Church, and, like a great many other people, got bowled out in the first innings. He returned to his allegiance in the most exemplary manner, and settled down to the most humdrum of young country gentlemen. He did exactly what every one else about him did. He was not naturally a profligate or vicious man; but there was a wild devil of animal passion in him, which had broken out in London, and which was now quieted by dread of consequences, but which he felt and knew was there, and might break out again. He was a changed man. There was a gulf between him and the life he had led before he went to London. He had tasted of liberty (or rather, not to profane that Divine word, of licentiousness), and yet not drunk long enough to make him weary of the draught. He had heard the dogmas he was brought up to believe infallible turned to unutterable ridicule by men like Saltire and Wrekin; men who, as he had the wit to see, were a thousand times cleverer and better informed than Father Clifford or Father Dennis. In short, he had found out, as a great many others have, that Popery won't hold water, and so, as a pis aller, he adopted Saltire's creed—that religion was necessary for the government of States, that one religion was as good as another, and that, cæteris paribus, the best religion was the one which secured the possessor £10,000 a year, and therefore Densil was a devout Catholic.

It was thought by the allied powers that he ought to marry. He had no objection and so he married a young lady, a Miss Winkleigh—Catholic, of course—about whom I can get no information whatever. Lady Ascot says that she was a pale girl, with about as much air as a milkmaid; on which two facts I can build no theory as to her personal character. She died in 1816, childless; and in 1820 Densil lost both his father and[Pg 10] mother, and found himself, at the age of thirty-seven, master of Ravenshoe and master of himself.

He felt the loss of the old folks most keenly, more keenly than that of his wife. He seemed without a stay or holdfast in the world, for he was a poorly educated man, without resources; and so he went on moping and brooding until good old Father Clifford, who loved him dearly, got alarmed, and recommended travels. He recommended Rome, the cradle of the faith, and to Rome he went.

He stayed at Rome a year; at the end of which time he appeared suddenly at home with a beautiful young wife on his arm. As Father Clifford, trembling and astonished, advanced to lay his hand upon her head, she drew up, laughed, and said, "Spare yourself the trouble, my dear sir; I am a Protestant."

I have had to tell you all this, in order to show you how it came about that Densil, though a Papist, bethought of marrying a Protestant wife to keep up a balance of power in his house. For, if he had not married this lady, the hero of this book would never have been born; and this greater proposition contains the less, "that if he had never been born, his history would never have been written, and so this book would have had no existence."

The second Mrs. Ravenshoe was the handsome dowerless daughter of a Worcester squire, of good standing, who, being blessed with an extravagant son, and six handsome daughters, had lived for several years abroad, finding society more accessible, and consequently, the matrimonial chances of the "Petersham girls" proportionately greater than in England. She was a handsome proud woman, not particularly clever, or particularly agreeable, or particularly anything, except particularly self-possessed. She had been long enough looking after an establishment to know thoroughly the value of one, and had seen quite enough of good houses to know that a house without a mistress is no house at all. Accordingly, in a very few days the house felt her presence, submitted with the best grace to her not unkindly rule, and in a week they all felt as if she had been there for years.

Father Clifford, who longed only for peace, and was getting[Pg 11] very old, got very fond of her, heretic as she was. She, too, liked the handsome, gentlemanly old man, and made herself agreeable to him, as a woman of the world knows so well how to do. Father Mackworth, on the other hand, his young coadjutor since Father Dennis's death, an importation of Lady Alicia's from Rome, very soon fell under her displeasure. The first Sunday after her arrival, she drove to church, and occupied the great old family pew, to the immense astonishment of the rustics, and, after afternoon service, caught up the old vicar in her imperious off-hand way, and will he nil he, carried him off to dinner—at which meal he was horrified to find himself sitting with two shaven priests, who talked Latin and crossed themselves. His embarrassment was greatly increased by the behaviour of Mrs. Ravenshoe, who admired his sermon, and spoke on doctrinal points with him as though there were not a priest within a mile. Father Mackworth was imprudent enough to begin talking at him, and at last said something unmistakably impertinent; upon which Mrs. Ravenshoe put her glass in her eye, and favoured him with such a glance of haughty astonishment as silenced him at once.

This was the beginning of hostilities between them, if one can give the name of hostilities to a series of infinitesimal annoyances on the one side, and to immeasurable and barely concealed contempt on the other. Mackworth, on the one hand, knew that she understood and despised him, and he hated her. She on the other hand knew that he knew it, but thought him too much below her notice, save now and then that she might put down with a high hand any, even the most distant, approach to a tangible impertinence. But she was no match for him in the arts of petty, delicate, galling annoyances. There he was her master; he had been brought up in a good school for that, and had learnt his lesson kindly. He found that she disliked his presence, and shrunk from his smooth, lean face with unutterable dislike. From that moment he was always in her way, overwhelming her with oily politeness, rushing across the room to pick up anything she had dropped, or to open the door, till it required the greatest restraint to avoid breaking through all forms of politeness, and bidding him begone. But why should we go on detailing trifles like these, which in themselves are nothing, but accumulated are unbearable?

So it went on, till one morning, about two years after the marriage, Mackworth appeared in Clifford's room, and, yawning, threw himself into a chair.

"Benedicite," said Father Clifford, who never neglected religious etiquette on any occasion.

Mackworth stretched out his legs and yawned, rather rudely, and then relapsed into silence. Father Clifford went on reading. At last Mackworth spoke.

"I'll tell you what, my good friend, I am getting sick of this; I shall go back to Rome."

"To Rome?"

"Yes, back to Rome," repeated the other impertinently, for he always treated the good old priest with contemptuous insolence when they were alone. "What is the use of staying here, fighting that woman? There is no more chance of turning her than a rock, and there is going to be no family."

"You think so?" said Clifford.

"Good heavens, does it look like it? Two years, and not a sign; besides, should I talk of going, if I thought so? Then there would be a career worthy of me; then I should have a chance of deserving well of the Church, by keeping a wavering family in her bosom. And I could do it, too: every child would be a fresh weapon in my hands against that woman. Clifford, do you think that Ravenshoe is safe?"

He said this so abruptly that Clifford coloured and started. Mackworth at the same time turned suddenly upon him, and scrutinised his face keenly.

"Safe!" said the old man; "what makes you fear otherwise?"

"Nothing special," said Mackworth; "only I have never been easy since you told me of that London escapade years ago."

"He has been very devout ever since," said Clifford. "I fear nothing."

"Humph! Well, I am glad to hear it," said Mackworth. "I shall go to Rome. I'd sooner be gossiping with Alphonse and Pierre in the cloisters than vegetating here. My talents are thrown away."

He departed down the winding steps of the priest's turret, which led to the flower garden. The day was fine, and a pleasant seat a short distance off invited him to sit. He could get a book he knew from the drawing-room, and sit there. So, with habitually noiseless tread, he passed along the dark corridor, and opened the drawing-room door.

Nobody was there. The book he wanted was in the little drawing-room beyond, separated from the room he was in by a partly-drawn curtain. The priest advanced silently over the deep piled carpet and looked in.

The summer sunlight, struggling through a waving bower of climbing plants and the small panes of a deeply mullioned window,[Pg 13] fell upon two persons, at the sight of whom he paused, and, holding his breath, stood, like a black statue in the gloomy room, wrapped in astonishment.

He had never in his life heard these twain use any words beyond those of common courtesy towards one another; he had thought them the most indifferent, the coldest pair, he had ever seen. But now! now, the haughty beauty was bending from her chair over her husband, who sat on a stool at her feet; her arm was round his neck, and her hand was in his; and, as he looked, she parted the clustering black curls from his forehead and kissed him.

He bent forward and listened more eagerly. He could hear the surf on the shore, the sea-birds on the cliffs, the nightingale in the wood; they fell upon his ear, but he could not distinguish them; he waited only for one of the two figures before him to speak.

At last Mrs. Ravenshoe broke silence, but in so low a voice that even he, whose attention was strained to the uttermost, could barely catch what she said.

"I yield, my love," said she; "I give you this one, but mind, the rest are mine. I have your solemn promise for that?"

"My solemn promise," said Densil, and kissed her again.

"My dear," she resumed, "I wish you could get rid of that priest, that Mackworth. He is irksome to me."

"He was recommended to my especial care by my mother," was Densil's reply. "If you could let him stay I should much rather."

"Oh, let him stay!" said she; "he is too contemptible for me to annoy myself about. But I distrust him, Densil. He has a lowering look sometimes."

"He is talented and agreeable," said Densil; "but I never liked him."

The listener turned to go, having heard enough, but was arrested by her continuing—

"By the by, my love, do you know that that impudent girl Norah has been secretly married this three months?"

The priest listened more intently than ever.

"Who to?" asked Densil.

"To James, your keeper."

"I am glad of that. That lad James stuck to me in prison, Susan, when they all left me. She is a fine, faithful creature, too. Mind you give her a good scolding."

Mackworth had heard enough apparently, for he stole gently away through the gloomy room, and walked musingly upstairs to Father Clifford.

That excellent old man took up the conversation just where it had left off.

"And when," said he, "my brother, do you propose returning to Rome?"

"I shall not go to Rome at all," was the satisfactory reply, followed by a deep silence.

In a few months, much to Father Clifford's joy and surprise, Mrs. Ravenshoe bore a noble boy, which was named Cuthbert. Cuthbert was brought up in the Romish faith, and at five years old had just begun to learn his prayers of Father Clifford, when an event occurred equally unexpected by all parties. Mrs. Ravenshoe was again found to be in a condition to make an addition to her family.

If you were a lazy yachtsman, sliding on a summer's day, before a gentle easterly breeze, over the long swell from the Atlantic, past the south-westerly shores of the Bristol Channel, you would find, after sailing all day beneath shoreless headlands of black slate, that the land suddenly fell away and sunk down, leaving, instead of beetling cliffs, a lovely amphitheatre of hanging wood and lawn, fronted by a beach of yellow sand—a pleasing contrast to the white surf and dark crag to which your eye had got accustomed.

This beautiful semicircular basin is about two miles in diameter, surrounded by hills on all sides, save that which is open to the sea. East and west the headlands stretch out a mile or more, forming a fine bay open to the north; while behind, landward, the downs roll up above the woodlands, a bare expanse of grass and grey stone. Half way along the sandy beach, a trout-stream comes foaming out of a dark wood, and finds its way across the shore in fifty sparkling channels; and the eye, caught by the silver thread of water, is snatched away above and beyond it, along a wooded glen, the cradle of the stream, which pierces the country landward for a mile or two, till the misty vista is abruptly barred by a steep blue hill, which crosses the valley at right angles. A pretty little village stands at the mouth of the stream, and straggles with charming irregularity along the shore for a considerable distance westward; while behind, some little[Pg 15] distance up the glen, a handsome church tower rises from among the trees. There are some fishing boats at anchor, there are some small boats on the beach, there is a coasting schooner beached and discharging coal, there are some fishermen lounging, there are some nets drying, there are some boys bathing, there are two grooms exercising four handsome horses; but it is not upon horses, men, boats, ship, village, church, or stream, that you will find your eye resting, but upon a noble, turreted, deep-porched, grey stone mansion, that stands on the opposite side of the stream, about a hundred feet above the village.

On the east bank of the little river, just where it joins the sea, abrupt lawns of grass and fern, beautifully broken by groups of birch and oak, rise above the dark woodlands, at the culminating point of which, on a buttress which runs down from the higher hills behind, stands the house I speak of, the north front looking on the sea, and the west on the wooded glen before mentioned—the house on a ridge dividing the two. Immediately behind again the dark woodlands begin once more, and above them is the moor.

The house itself is of grey stone, built in the time of Henry VIII. The façade is exceedingly noble, though irregular; the most striking feature in the north or sea front being a large dark porch, open on three sides, forming the basement of a high stone tower, which occupies the centre of the building. At the north-west corner (that towards the village) rises another tower of equal height; and behind, above the irregular groups of chimneys, the more modern cupola of the stables shows itself as the highest point of all, and gives, combined with the other towers, a charming air of irregularity to the whole. The windows are mostly long, low, and heavily mullioned, and the walls are battlemented.

On approaching the house you find that it is built very much after the fashion of a college, with a quadrangle in the centre. Two sides of this, the north and west, are occupied by the house, the south by the stables, and the east by a long and somewhat handsome chapel, of greater antiquity than the rest of the house. The centre of this quad, in place of the trim grass-plat, is occupied by a tan lunging ring, in the middle of which stands a granite basin filled with crystal water from the hills. In front of the west wing, a terraced flower-garden goes step by step towards the stream, till the smooth-shaven lawns almost mingle with the wild ferny heather turf of the park, where the dappled deer browse, and the rabbit runs to and fro busily. On the north, towards the sea, there are no gardens; but a noble gravel[Pg 16] terrace, divided from the park only by a deep rampart, runs along beneath the windows; and to the east the deer-park stretches away till lawn and glade are swallowed up in the encroaching woodland.

Such is Ravenshoe Hall at the present day, and such it was on the 10th of June, 1831 (I like to be particular), as regards the still life of the place; but, if one had then regarded the living inhabitants, one would have seen signs of an unusual agitation. Round the kitchen door stood a group of female servants talking eagerly together; and, at the other side of the court, some half-dozen grooms and helpers were evidently busy on the same theme, till the appearance of the stud-groom entering the yard suddenly dispersed them right and left; to do nothing with superabundant energy.

To them also entered a lean, quiet-looking man, aged at this time fifty-two. We have seen him before. He was our old friend Jim, who had attended Densil in the Fleet prison in old times. He had some time before this married a beautiful Irish Catholic waiting-maid of Lady Alicia's, by whom he had a daughter, now five years old, and a son aged one week. He walked across the yard to where the women were talking, and addressed them.

"How is my lady to-night?" said he.

"Holy Mother of God!" said a weeping Irish housemaid, "she's worse."

"How's the young master?"

"Hearty, a darling; crying his little eyes out, he is, a-bless him."

"He'll be bigger than Master Cuthbert, I'll warrant ye," said a portly cook.

"When was he born?" asked James.

"Nigh on two hours," said the other speaker.

At this conjuncture a groom came running through the passage, putting a note in his hat as he went; he came to the stud-groom, and said hurriedly, "A note for Dr. Marcy at Lanceston, sir. What horse am I to take?"

"Trumpeter. How is my lady?"

"Going, as far as I can gather, sir."

James waited until he heard him dash full speed out of the yard, and then till he saw him disappear like a speck along the mountain road far aloft; then he went into the house, and, getting as near to the sick room as he dared, waited quietly on the stairs.

It was a house of woe, indeed! Two hours before, one feeble,[Pg 17] wailing little creature had taken up his burthen, and begun his weary pilgrimage across the unknown desolate land that lay between him and the grave—for a part of which you and I are to accompany him; while his mother even now was preparing for her rest, yet striving for the child's sake to lengthen the last few weary steps of her journey, that they two might walk, were it never so short a distance, together.

The room was very still. Faintly the pure scents and sounds stole into the chamber of death from the blessed summer air without; gently came the murmur of the surf upon the sands; fainter and still fainter came the breath of the dying mother. The babe lay beside her, and her arm was round its body. The old vicar knelt by the bed, and Densil stood with folded arms and bowed head, watching the face which had grown so dear to him, till the light should die out from it for ever. Only those four in the chamber of death!

The sighing grew louder, and the eye grew once more animated. She reached out her hand, and, taking one of the vicar's, laid it upon the baby's head. Then she looked at Densil, who was now leaning over her, and with a great effort spoke.

"Densil, dear, you will remember your promise?"

"I will swear it, my love."

A few more laboured sighs, and a greater effort: "Swear it to me, love."

He swore that he would respect the promise he had made, so help him God!

The eyes were fixed now, and all was still. Then there was a long sigh; then there was a long silence; then the vicar rose from his knees, and looked at Densil. There were but three in the chamber now.

Densil passed through the weeping women, and went straight to his own study. There he sat down, tearless, musing much about her who was gone.

How he had grown to love that woman, he thought—her that he had married for her beauty and her pride, and had thought so cold and hard! He remembered how the love of her had grown stronger, year by year, since their first child was born. How he had respected her for her firmness and consistency; and how often, he thought, had he sheltered his weakness behind her strength! His right hand was gone, and he was left alone to do battle by himself!

One thing was certain. Happen what would, his promise[Pg 18] should be respected, and this last boy, just born, should be brought up a Protestant as his mother had wished. He knew the opposition he would have from Father Mackworth, and determined to brave it. And, as the name of that man came into his mind, some of his old fierce, savage nature broke out again, and he almost cursed him aloud.

"I hate that fellow! I should like to defy him, and let him do his worst. I'd do it, now she's gone, if it wasn't for the boys. No, hang it, it wouldn't do. If I'd told him under seal of confession, instead of letting him grab it out, he couldn't have hung it over me like this. I wish he was—"

If Father Mackworth had had the slightest inkling of the state of mind of his worthy patron towards him, it is very certain that he would not have chosen that very moment to rap at the door. The most acute of us make a mistake sometimes; and he, haunted with vague suspicions since the conversation he had overheard in the drawing-room before the birth of Cuthbert, grew impatient, and determined to solve his doubts at once, and, as we have seen, selected the singularly happy moment when poor passionate Densil was cursing him to his heart's content.

"Brother, I am come to comfort you," he said, opening the door before Densil had time, either to finish the sentence written above, or to say "Come in." "This is a heavy affliction, and the heavier because—"

"Go away," said Densil, pointing to the door.

"Nay, nay," said the priest, "hear me—"

"Go away," said Densil, in a louder tone. "Do you hear me? I want to be alone, and I mean to be. Go!"

How recklessly defiant weak men get when they are once fairly in a rage? Densil, who was in general civilly afraid of this man, would have defied fifty such as he now.

"There is one thing, Mr. Ravenshoe," said the priest, in a very different tone, "about which I feel it my duty to speak to you, in spite of the somewhat unreasonable form your grief has assumed. I wish to know what you mean to call your son."

"Why?"

"Because he is ailing, and I wish to baptise him."

"You will do nothing of the kind, sir," said Densil, as red as a turkey-cock. "He will be baptised in proper time in the parish church. He is to be brought up a Protestant."

The priest looked steadily at Densil, who, now brought fairly to bay, was bent on behaving like a valiant man, and said slowly—

"So my suspicions are confirmed, then, and you have determined to hand over your son to eternal perdition" (he didn't say[Pg 19] perdition, he used a stronger word, which we will dispense with, if you have no objection).

"Perdition, sir!" bawled Densil; "how dare you talk of a son of mine in that free-and-easy sort of way? Why, what my family has done for the Church ought to keep a dozen generations of Ravenshoes from a possibility of perdition, sir. Don't tell me."

This new and astounding theory of justification by works, which poor Densil had broached in his wrath, was overheard by a round-faced, bright-eyed, curly-headed man about fifty, who entered the room suddenly, followed by James. For one instant you might have seen a smile of intense amusement pass over his merry face; but in an instant it was gone again, and he gravely addressed Densil.

"My dear Mr. Ravenshoe, I must use my authority as doctor, to request that your son's spiritual welfare should for the present yield to his temporal necessities. You must have a wet-nurse, my good sir."

Densil's brow had grown placid in a moment beneath the doctor's kindly glance. "God bless me," he said, "I never thought of it. Poor little lad! poor little lad!"

"I hope, sir," said James, "that you will let Norah have the young master. She has set her heart upon it."

"I have seen Mrs. Horton," said the doctor, "and I quite approve of the proposal. I think it, indeed, a most special providence that she should be able to undertake it. Had it been otherwise, we might have been undone."

"Let us go at once," said the impetuous Densil. "Where is the nurse? where is the boy?" And, so saying, he hurried out of the room, followed by the doctor and James.

Mackworth stood alone, looking out of the window, silent. He stood so long that one who watched him peered from his hiding-place more than once to see if he were gone. At length he raised his arm and struck his clenched hand against the rough granite window-sill so hard that he brought blood. Then he moodily left the room.

As soon as the room was quiet, a child about five years old crept stealthily from a dark corner where he had lain hidden, and with a look of mingled shyness and curiosity on his face, departed quietly by another door.

Meanwhile, Densil, James, and the doctor, accompanied by the nurse and baby, were holding their way across the court-yard towards a cottage which lay in the wood beyond the stables. James opened the door, and they passed into the inner room.

A beautiful woman was sitting propped up by pillows, nursing a week-old child. The sunlight, admitted by a half-open shutter, fell upon her, lighting up her delicate features, her pale pure complexion, and bringing a strange sheen on her long loose black hair. Her face was bent down, gazing on the child which lay on her breast; and at the entrance of the party she looked up, and displayed a large lustrous dark blue eye, which lighted up with infinite tenderness, as Densil, taking the wailing boy from the nurse, placed it on her arm beside the other.

"Take care of that for me, Norah," said Densil. "It has no mother but you, now."

"Acushla ma chree," she answered; "bless my little bird. Come to your nest, alanna, come to your pretty brother, my darlin'."

The child's wailing was stilled now, and the doctor remarked, and remembered long afterwards, that the little waxen fingers, clutching uneasily about, came in contact with the little hand of the other child, and paused there. At this moment, a beautiful little girl, about five years old, got on the bed, and nestled her peachy cheek against her mother's. As they went out, he turned and looked at the beautiful group once more, and then he followed Densil back to the house of mourning.

Reader, before we have done with those three innocent little faces, we shall see them distorted and changed by many passions, and shall meet them in many strange places. Come, take my hand, and we will follow them on to the end.

I have noticed that the sayings and doings of young gentlemen before they come to the age of, say seven or eight, are hardly interesting to any but their immediate relations and friends. I have my eye, at this moment, on a young gentleman of the mature age of two, the instances of whose sagacity and eloquence are of greater importance, and certainly more pleasant, to me, than the projects of Napoleon, or the orations of Bright. And yet I fear that even his most brilliant joke, if committed to paper, would fall dead upon the public ear; and so, for the present, I shall[Pg 21] leave Charles Ravenshoe to the care of Norah, and pass on to some others who demand our attention more.

The first thing which John Mackworth remembered was his being left in the loge of a French school at Rouen by an English footman. Trying to push back his memory further, he always failed to conjure up any previous recollection to that. He had certainly a very indistinct one of having been happier, and having lived quietly in pleasant country places with a kind woman who talked English; but his first decided impression always remained the same—that of being, at six years old, left friendless, alone, among twenty or thirty French boys older than himself.

His was a cruel fate. He would have been happier apprenticed to a collier. If the man who sent him there had wished to inflict the heaviest conceivable punishment on the poor unconscious little innocent, he could have done no more than simply left him at that school. We shall see how he found out at last who his benefactor was.

English boys are sometimes brutal to one another (though not so often as some wish to make out), and are always rough. Yet I must say, as far as my personal experience goes, the French boy is entirely master in the art of tormenting. He never strikes; he does not know how to clench his fist. He is an arrant coward, according to an English schoolboy's definition of the word: but at pinching, pulling hair, ear pulling, and that class of annoyance, all the natural ingenuity of his nation comes out, and he is superb; add to this a combined insolent studied sarcasm, and you have an idea of what a disagreeable French schoolboy can be.

To say that the boys at poor John Mackworth's school put all these methods of torture in force against him, and ten times more, is to give one but a faint idea of his sufferings. The English at that time were hated with a hatred which we in these sober times have but little idea of; and, with the cannon of Trafalgar ringing as it were in their ears, these young French gentlemen seized on Mackworth as a lawful prize providentially delivered into their hands. We do not know what he may have been under happier auspices, or what he may be yet with a more favourable start in another life; we have only to do with what he was. Six years of friendless persecution, of life ungraced and uncheered by domestic love, of such bitter misery as childhood alone is capable of feeling or enduring, transformed him from a child into a heartless, vindictive man.

And then, the French schoolmaster having roughly finished the piece of goods, it was sent to Rome to be polished and turned out[Pg 22] ready for the market. Here I must leave him; I don't know the process. I have seen the article when finished, and am familiar with it. I know the trade mark on it as well as I know the Tower mark on my rifle. I may predicate of a glass that it is Bohemian ruby, and yet not know how they gave it the colour. I must leave descriptions of that system to Mr. Steinmetz, and men who have been behind the scenes.

The red-hot ultramontane thorough-going Catholicism of that pretty pervert, Lady Alicia, was but ill satisfied with the sensible, old English, cut and dried notions of the good Father Clifford. A comparison of notes with two or three other great ladies, brought about a consultation, and a letter to Rome, the result of which was that a young Englishman of presentable exterior, polite manners, talking English with a slight foreign accent, made his appearance at Ravenshoe, and was installed as her ladyship's confessor, about eighteen months before her death.

His talents were by no means ordinary. In very few days he had gauged every intellect in the house, and found that he was by far the superior of all in wit and education; and he determined that as long as he stayed in the house he would be master there.

Densil's jealous temper sadly interfered with this excellent resolution; he was immensely angry and rebellious at the slightest apparent infringement of his prerogative, and after his parents' death treated Mackworth in such an exceedingly cavalier manner, that the latter feared he should have to move, till chance threw into his hand a whip wherewith he might drive Densil where he would. He discovered a scandalous liaison of poor Densil's, and in an indirect manner let him know that he knew all about it. This served to cement his influence until the appearance of Mrs. Ravenshoe the second, who, as we have seen, treated him with such ill-disguised contempt, that he was anything but comfortable, and was even meditating a retreat to Rome, when the conversation he overheard in the drawing-room made him pause, and the birth of the boy Cuthbert confirmed his resolution to stay.

For now, indeed, there was a prospect open to him. Here was this child delivered over to him like clay to a potter, that he might form it as he would. It should go hard but that the revenues and county influence of the Ravenshoes should tend to the glory of the Church as heretofore. Only one person was in his way, and that was Mrs. Ravenshoe; after her death he was master of the situation with regard to the eldest of the boys. He had partly guessed, ever since he overheard the conversation of[Pg 23] Densil and his wife, that some sort of bargain existed between them about the second child; but he paid little heed to it. It was, therefore, with the bitterest anger that he saw his fears confirmed, and Densil angrily obstinate on the matter; for supposing Cuthbert were to die, all his trouble and anxiety would avail nothing, and the old house and lands would fall to a Protestant heir, the first time in the history of the island. Father Clifford consoled him.

Meanwhile, his behaviour towards Densil was gradually and insensibly altered. He became the free and easy man of the world, the amusing companion, the wise counsellor. He saw that Densil was of a nature to lean on some one, and he was determined it should be on him; so he made himself necessary. But he did more than this; he determined he would be beloved as well as respected, and with a happy audacity he set to work to win that poor wild foolish heart to himself, using such arts of pleasing as must have been furnished by his own mother wit, and could never have been learned in a hundred years from a Jesuit college. The poor heart was not a hard one to win; and, the day they buried poor Father Clifford in the mausoleum, it was with a mixture of pride at his own talents, and contemptuous pity for his dupe, that Mackworth listened to Densil as he told him that he was now his only friend, and besought him not to leave him—which thing Mackworth promised, with the deepest sincerity, he would not do.

Master Charles, blessed with a placid temper and a splendid appetite, throve amazingly. Before you knew where you were, he was in tops and bottoms; before you had thoroughly realized that, he was learning his letters; then there was hardly time to turn round, before he was a rosy-cheeked boy of ten.

From the very first gleam of reason, he had been put solely and entirely under the care of Mr. Snell, the old vicar, who had been with his mother when she died, and a Protestant nurse, Mrs. Varley. Faithfully had these two discharged their sacred trust; and, if love can repay such services, right well were they repaid.

A pleasant task they had, though, for a more lovable little lad than Charles there never was. His little heart seemed to have an infinite capacity of affection for all who approached him. Everything animate came before him in the light of a friend, to whom he wished to make himself agreeable, from his old kind tutor and nurse down to his pony and terrier. Charles had not arrived at the time of life when it was possible for him to quarrel about women; and so he actually had no enemies as yet, but was welcomed by pleasant and kind faces wherever he went. At one time he would be at his father's knee, while the good-natured Densil made him up some fishing tackle; next you would find him in the kennel with the whipper-in, feeding the hounds, half-smothered by their boisterous welcome; then the stables would own him for a time, while the lads were cleaning up and feeding; then came a sudden flitting to one of the keeper's lodges; and anon he would be down on the sands wading with half a dozen fisher-boys as happy as himself—but welcome and beloved everywhere.

Sunday was a right pleasant day for him. After seeing his father shave, and examining his gold-topped dressing-case from top to bottom—amusements which were not participated in by Cuthbert, who had grown too manly—he would haste through his breakfast, and with his clean clothes hurry down the village towards the vicarage, which stood across the stream near the church. Not to go in yet, you will observe, because the sermon, he well knew, was getting its finishing touches, and the vicar must not be disturbed. No, the old stone bridge would bring him up; and there he would stay looking at the brown crystal-clear water rushing and seething among the rocks, lying dark under the oak-roots, and flashing merrily over the weir, just above the bridge; till "flick!" a silver bar would shoot quivering into the air, and a salmon would light on the top of the fall, just where the water broke, and would struggle on into the still pool above, or be beaten back by the force, to resume his attempt when he had gained breath. The trout, too, under the bridge, bless the rogues, they knew it was Sunday well enough—how they would lie up there in the swiftest places, where glancing liquid glorified the poor pebbles below into living amber, and would hardly trouble themselves to snap at the great fat, silly stoneflies that came floating down. Oh! it was a terrible place for dawdling was that stone bridge, on a summer sabbath morn.

But now would the country folks come trooping in from far and near, for Ravenshoe was the only church for miles, and however many of them there were, every one had a good hearty West-country[Pg 25] greeting for him. And, as the crowd increased near the church door, there was so much to say and hear, that I am afraid the prayers suffered a little sometimes.

The villagers were pleased enough to see the lad in the old carved horsebox (not to be irreverent) of a pew, beneath the screen in the chancel, with the light from the old rose window shining on his curly brown hair. The older ones would think of the haughty beautiful lady who sat there so few years ago, and oftentimes one of the more sagacious would shake his head and mutter to himself, "Ah! if he were heir."

Any boy who reads this story, and I hope many will read it, is hereby advertised that it is exceedingly wrong to be inattentive in church in sermon time. It is very naughty to look up through the windows at the white clouds flying across the blue sky, and think how merrily the shadows are sweeping over the upland lawn, where the pewits' nests are, and the blackcock is crowing on the grey stones among the heather. No boy has any right to notice another boy's absence, and spend sermon-time in wondering whether he is catching crabs among the green and crimson seaweed on the rocks, or bathing in the still pool under the cliff. A boy had better not go to church at all if he spends his time in thinking about the big trout that lies up in one of the pools of the woodland stream, and whether he will be able to catch a sight of him again by creeping gently through the hazel and king fern. Birds' nests, too, even though it be the ringousel's, who is to lay her last egg this blessed day, and is marked for spoliation to-morrow, should be banished from a boy's mind entirely during church time. Now, I am sorry to say, that Charley was very much given to wander in church, and, when asked about the sermon by the vicar next day, would look rather foolish. Let us hope that he will be a warning to all sinners in this respect.

Then, after church, there would be dinner, at his father's lunch time, in the dark old hall, and there would be more to tell his father and brother than could be conveniently got through at that meal; then there was church again, and a long stroll in the golden sunshine along the shore. Ah, happy summer sabbaths!

The only two people who were ever cold to Charley, were his brother and Mackworth. Not that they were openly unkind, but there was between both of them and himself an indefinable gulf, an entire want of sympathy, which grieved him sometimes, though he was as yet too young to be much troubled by it. He only exhausted all his little arts of pleasing towards them to try and win them; he was indefatigable in running messages for Cuthbert[Pg 26] and the chaplain; and once, when kind grandaunt Ascot (she was a Miss Headstall, daughter of Sir Cingle Headstall, and married Lord George Ascot, brother of Lady Alicia, Densil's mother) sent him a pineapple in a box, he took it to the priest and would have had him take it. Mackworth refused it, but looked on him not unkindly for a few minutes, and then turned away with a sigh. Perhaps he was trying to recall the time so long, long ago, when his own face was as open and as innocent as that. God knows! Charles cried a little, because the priest wouldn't take it, and, having given his brother the best slice, ate the rest in the stable, with the assistance of his foster brother and two of the pad grooms. Thereby proving himself to be a lad of low and dissipated habits.

Cuthbert was at this time a somewhat good-looking young fellow of sixteen. Neither of the brothers was what would be called handsome, though, if Charley's face was the most pleasing, Cuthbert certainly had the most regular features. His forehead was lofty, although narrow, and flat at the sides; his cheek bones were high, and his nose was aquiline, not ill-formed, though prominent, starting rather suddenly out below his eyes; the lips were thin, the mouth small and firmly closed, and the chin short and prominent. The tout ensemble was hardly pleasing even at this youthful period; the face was too much formed and decided for so young a man.

Cuthbert was a reserved methodical lad, with whom no one could find fault, and yet whom few liked. He was studious and devout to an extent rare in one so young; and, although a capital horseman and a good shot, he but seldom indulged in those amusements, preferring rather a walk with the steward, and soon returning to the dark old library to his books and Father Mackworth. There they two would sit, like two owls, hour after hour, appearing only at meals, and talking French to one another, noticing Charley but little; who, however, was always full of news, and would tell it, too, in spite of the inattention of the strange couple. Densil began to respect and be slightly afraid of his eldest son, as his superior in learning and in natural abilities; but I think Charles had the biggest share in his heart.

Aunt Ascot had a year before sent to Cuthbert to pay her a visit at Ranford, her son's, Lord Ascot's place, where she lived with him, he being a widower, and kept house for him. Ranford, we all know, or ought to know, contains the largest private racing stud in England, and the Ascot family for many generations had given themselves up entirely to sporting—so much so, that their marriages with other houses have been to a certain extent influenced by it; and so poor Cuthbert, as we may suppose,[Pg 27] was quite like a fish out of water. He detested and despised the men he met there, and they, on their parts, such of them as chose to notice him, thought him a surly young bookworm; and, as for his grandaunt, he hated the very sound of that excellent lady's voice. Her abruptness, her homœopathic medicines, her Protestantism (which she was always airing), and her stable-talk, nearly drove him mad; while she, on the other hand, thought him one of the most disagreeable boys she had ever met with in her life. So the visit was rather a failure than otherwise, and not very likely to be repeated. Nevertheless, her ladyship was very fond of young faces, and so in a twelvemonth, she wrote to Densil as follows:—

"I am one mass of lumbago all round the small of my back, and I find nothing like opodeldoc after all. The pain is very severe, but I suppose you would comfort me, as a heretic, by saying it is nothing to what I shall endure in a few years' time. Bah! I have no patience with you Papists, packing better people than yourselves off somewhere in that free-and-easy way. By-the-bye, how is that father confessor of yours, Markworth, or some such name—mind me, Ravenshoe, that fellow is a rogue, and you being, like all Ravenshoes, a fool, there is a pair of you. Why, if one of Ascot's grooms was to smile as that man does, or to whine in his speech as that man does, when he is talking to a woman of rank, I'd have him discharged on the spot, without warning, for dishonesty.

"Don't put a penny on Ascot's horse at Chester; he will never stay over the Cup course. Curfew, in my opinion, looks by no means badly for the Derby; he is scratched for the Two Thousand—which was necessary, though I am sorry for it, &c., &c., &c.

"I wish you would send me your boy, will you? Not the eldest: the Protestant one. Perhaps he mayn't be such an insufferable coxcomb as his brother."

At which letter Densil shook his honest sides with uproarious laughter. "Cuthbert, my boy," he said, "you have won your dear aunt's heart entirely; though she, being determined to mortify the flesh with its affection, does not propose seeing you again, but asks for Charley. The candour of that dear old lady increases with her age. You seem to have been making your court, too, father; she speaks of your smile in the most unqualified terms."

"Her ladyship must do me the honour to quiz me," said Mackworth. "If it is possible to judge by her eye, she must like me about as well as a mad dog."

"For my part, father," said Cuthbert, curling up the corners[Pg 28] of his thin lips sardonically, "I shall be highly content to leave my dear aunt in the peaceable enjoyment of her favourite society of grooms, horse-jockeys, blacklegs, dissenting ministers, and such-like. A month in that house, my dear Charley, will qualify you for a billiard-marker; and, after a course of six weeks, you will be fit to take the situation of croupier in a low hell on a race-course. How you will enjoy yourself, my dear!"

"Steady, Cuthbert steady," said his father; "I can't allow you to talk like that about your cousin's house. It is a great house for field sports, but there is not a better conducted house in the kingdom."

Cuthbert lay over the sofa to fondle a cat, and then continued speaking very deliberately, in a slightly louder voice,—

"I will allow my aunt to be the most polite, intellectual, delicate-minded old lady in creation, my dearest father, if you wish it; only, not having been born (I beg her pardon, dropped) in a racing stable, as she was herself, I can hardly appreciate her conversation always. As for my cousin, I consider him a splendid sample of an hereditary legislator. Charley, dear, you won't go to church on Sunday afternoon at Ranford; you will go into the croft with your cousin Ascot to see the chickens fed. Ascot is very curious in his poultry, particularly on Sunday afternoon. Father, why does he cut all the cocks' tails square?"

"Pooh, pooh," said Densil, "what matter? many do it, besides him. Don't you be squeamish, Cuthbert—though, mind you, I don't defend cock-fighting on Sunday."

Cuthbert laughed and departed, taking his cat with him.

Charles had a long coach journey of one day, and then an awful and wonderful journey on the Great Western Railway as far as Twyford—alighting at which place, he was accosted by a pleasant-looking, fresh-coloured boy, dressed in close-fitting cord trousers, a blue handkerchief, spotted with white, and a Scotch cap; who said—

"Oh! I'm your cousin Welter. I'm the same age as you, and I'm going to Eton next half. I've brought you over Tiger, because Punch is lame, and the station-master will look after your things; so we can come at once."

The boys were friends in two minutes; and, going out, there was a groom holding two ponies—on the prettiest of which Charley soon found himself seated, and jogging on with his companion towards Henley.

I like to see two honest lads, just introduced, opening their hearts to one another, and I know nothing more pleasant than to see how they rejoice as each similarity of taste comes out. By[Pg 29] the time these two had got to Henley Bridge, Lord Welter had heard the name of every horse in the Ravenshoe stables, and Charley was rapidly getting learned in Lord Ascot's racing stud. The river at Henley distracted his attention for a time, as the biggest he had seen, and he asked his cousin, "Did he think the Mississippi was much bigger than that now?" and Lord Welter supposed, "Oh dear yes, a great deal bigger," he should say. Then there was more conversation about dogs and guns, and pleasant country places to ride through; then a canter over a lofty breezy down, and then the river again, far below, and at their feet the chimneys of Ranford.

The house was very full; and, as the boys came up there was a crowd of phaetons, dog-carts, and saddle-horses, for the people were just arriving home for dinner after the afternoon drive; and, as they had all been to the same object of attraction that afternoon, they had all come in together and were loitering about talking, some not yet dismounted, and some on the steps. Welter was at home at once, and had a word with every one; but Charles was left alone, sitting on his pony, feeling very shy; till, at last, a great brown man with a great brown moustache, and a gruff voice, came up to him and lifted him off the horse, holding him out at arm's length for inspection.

"So you are Curly Ravenshoe's boy, hey?" said he.

"Yes, sir."

"Ha!" said the stranger, putting him down, and leading him towards the door; "just tell your father you saw General Mainwaring, will you? and that he wanted to know how his old friend was."

Charles looked at the great brown hand which was in his own, and thought of the Affghan war, and of all the deeds of renown that that hand had done, and was raising his eyes to the general's face, when they were arrested half-way by another face, not the general's.

It was that of a handsome, grey-headed man, who might have been sixty, he was so well conservé, but who was actually far more. He wore his own white hair, which contrasted strongly with a pair of delicate thin black eyebrows. His complexion was florid, with scarcely a wrinkle, his features were fine and regular, and a pair of sparkling dark grey eyes gave a pleasant light to his face. His dress was wondrously neat, and Charles, looking on him, guessed, with a boy's tact, that he was a man of mark.

"Whose son did you say he was, general?" said the stranger.

"Curly's!" said Mainwaring, stopping and smiling.

"No, really!" said the other; and then he looked fixedly at[Pg 30] Charles, and began to laugh, and Charley, seeing nothing better to do, looked up at the grey eyes and laughed too, and this made the stranger worse; and then, to crown the joke, the general began to laugh too, though none of them had said a syllable more than what I have written down; and at last the ridiculous exhibition finished up by the old gentleman taking a great pinch of snuff from a gold box, and turning away.

Charles was much puzzled, and was still more so when, in an hour's time, having dressed himself, and being on his way downstairs to his aunt's room, who had just come in, he was stopped on a landing by this same old gentleman, beautifully dressed for dinner, who looked on him as before.

He didn't laugh this time, but he did worse. He utterly "dumbfoundered" Charley, by asking abruptly—

"How's Jim?"

"He is very well, thank you, sir. His wife Norah nursed me when mamma died."

"Oh, indeed," said the other; "so he hasn't cut your father's throat yet, or anything of that sort?"

"Oh dear no," said Charles, horrified; "bless you, what can make you think of such things? Why, he is the kindest man in the world."

"I don't know," said the old gentleman, thoughtfully; "that excessively faithful kind of creature is very apt to do that sort of thing. I should discharge any servant of mine who exhibited the slightest symptoms of affection as a dangerous lunatic;" with which villainous sentiment he departed.

Charles thought what a strange old gentleman he was for a short time, and then slid down the banisters. They were better banisters than those at Ravenshoe, being not so steep, and longer: so he went up, and slid down again;[1] after which he knocked at his aunt's door.

It was with a beating heart that he waited for an answer. Cuthbert had described Lady Ascot as such a horrid old ogress, that he was not without surprise when a cheery voice said, "Come in;" and entering a handsome room, he found himself in presence of a noble-looking old lady, with grey hair, who was netting in an upright, old-fashioned chair.