| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/misssantaclausof00john |

| Miss Santa Claus | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| "Oh, dear Santa Claus" | 19 |

| "Here!" he said | 29 |

| "Oh, rabbit dravy!" he cried | 57 |

| He pushed aside the red plush curtain and looked in | 69 |

| And ran after the boy as hard as she could go | 77 |

| It was about the Princess Ina | 99 |

| The shower of stars falling on the blanket made her think of the star-flower | 121 |

| "Take it back!" | 165 |

It seemed as if everybody at the Junction wanted something that afternoon; thread or buttons or yarn, or the home-made doughnuts which helped out the slim stock of goods in the little notion store which had once been the parlor. And it seemed as if[4] Grandma Neal never would finish waiting on the customers and come back to tell the rest of the story about the Camels and the Star; for no sooner did one person go out than another one came in. He knew by the tinkling of the bell over the front door, every time it opened or shut.

The door between the shop and sitting-room being closed, Will'm could not hear much that was said, but several times he caught the word "Christmas," and once somebody said "Santa Claus," in such a loud happy-sounding voice that he slipped down from the chair and ran across the room to open the door a crack. It was only lately that he had begun to hear much about Santa Claus. Not until Libby started to school that fall did they know that there is such a wonderful person in the world. Of course they had heard his name, as they had heard Jack Frost's, and had seen his picture in story-books and advertisements, but they hadn't known that he is really true till the other children told Libby. Now nearly[5] every day she came home with something new she had learned about him.

Will'm must have known always about Christmas though, for he still had a piece of a rubber dog which his father had sent him on his first one, and—a Teddy Bear on his second. And while he couldn't recall anything about those first two festivals except what Libby told him, he could remember the last one perfectly. There had been a sled, and a fire-engine that wound up with a key, and Grandma Neal had made him some cooky soldiers with red cinnamon-drop buttons on their coats.

She wasn't his own grandmother, but she had taken the place of one to Libby and him, all the years he had been in the world. Their father paid their board, to be sure, and sent them presents and came to see them at long intervals when he could get away from his work, but that was so seldom that Will'm did not feel very well acquainted with him; not so well as Libby did. She was three years older, and could even remember[6] a little bit about their mother before she went off to heaven to get well. Mrs. Neal wasn't like a real grandmother in many ways. She was almost too young, for one thing. She was always very brisk and very busy, and, as she frequently remarked, she meant what she said and she would be minded.

That is why Will'm turned the knob so softly that no one noticed for a moment that the door was ajar. A black-bearded man in a rough overcoat was examining a row of dolls which dangled by their necks from a line above the show case. He was saying jokingly:

"Well, Mrs. Neal, I'll have to be buying some of these jimcracks before long. If this mud keeps up, no reindeer living could get out to my place, and it wouldn't do for the young'uns to be disappointed Christmas morning."

Then he caught sight of a section of a small boy peeping through the door, for all that showed of Will'm through the crack[7] was a narrow strip of blue overalls which covered him from neck to ankles, a round pink cheek and one solemn eye peering out from under his thatch of straight flaxen hair like a little Skye terrier's. When the man saw that eye he hurried to say: "Of course mud oughtn't to make any difference to Santy's reindeer. They take the Sky Road, right over the house tops and all."

The crack widened till two eyes peeped in, shining with interest, and both stubby shoes ventured over the threshold. A familiar sniffle made Grandma Neal turn around.

"Go back to the fire, William," she said briskly. "It isn't warm enough in here for you with that cold of yours."

The order was obeyed as promptly as it was given, but with a bang of the door so rebellious and unexpected that the man laughed. There was an amused expression on the woman's face, too, as she glanced up from the package she was tying, to explain with an indulgent smile.

"That wasn't all temper, Mr. Woods. It was part embarrassment that made him slam the door. Usually he doesn't mind strangers, but he takes spells like that sometimes."

"That's only natural," was the drawling answer. "But it isn't everybody who knows how to manage children, Mrs. Neal. I hope now that his stepmother when he gets her, will understand him as well as you do. My wife tells me that the poor little kids are going to have one soon. How do they take to the notion?"

Mrs. Neal stiffened a little at the question, although he was an old friend, and his interest was natural under the circumstances. There was a slight pause, then she said:

"I haven't mentioned the subject to them yet. No use to make them cross their bridge before they get to it. I've no doubt Molly will be good to them. She was a nice little thing when she used to go to school here at the Junction."

"It's queer," mused the man, "how she and Bill Branfield used to think so much of each other, from their First Reader days till both families moved away from here, and then that they should come across each other after all these years, from different states, too."

Instinctively they had lowered their voices, but Will'm on the other side of the closed door was making too much noise of his own to hear anything they were saying. Lying full length on the rug in front of the fire, he battered his heels up and down on the floor and pouted. His cold made him miserable, and being sent out of the shop made him cross. If he had been allowed to stay there's no telling what he might have heard about those reindeer to repeat to Libby when she came home from school.

Suddenly Will'm remembered the last bit of information which she had brought home to him, and, scrambling hastily up from the floor, he climbed into the rocking chair as if something were after him:

"Santa Claus is apt to be looking down the chimney any minute to see how you're behaving. And no matter if your lips don't show it outside, he knows when you're all puckered up with crossness and pouting on the inside!"

At that terrible thought Will'm began to rock violently back and forth and sing. It was a choky, sniffling little tune that he sang. His voice sounded thin and far away even to his own ears, because his cold was so bad. But the thought that Santa might be listening, and would write him down as a good little boy, kept him valiantly at it for several minutes. Then because he had a way of chanting his thoughts out loud sometimes, instead of thinking them to himself, he went on, half chanting, half talking the story of the Camels and the Star, which he was waiting for Grandma Neal to come back and finish. He knew it as well as she did, because she had told it to him so often in the last week.

"An' the wise men rode through the night,[11] an' they rode an' they rode, an' the bells on the bridles went ting-a-ling! just like the bell on Dranma's shop door. An' the drate big Star shined down on 'em and went ahead to show 'em the way. An' the drate big reindeer runned along the Sky Road"—he was mixing Grandma Neal's story now with what he had heard through the crack in the door, and he found the mixture much more thrilling than the original recital. "An' they runned an' they runned an' the sleighbells went ting-a-ling! just like the bell on Dranma's shop door. An' after a long time they all comed to the house where the baby king was at. Nen the wise men jumped off their camels and knelt down and opened all their boxes of pretty things for Him to play with. An' the reindeer knelt down on the roof where the drate big shining star stood still, so Santy could empty all his pack down the baby king's chimney."

It was a queer procession which wandered through Will'm's sniffling, sing-song account. To the camels, sages and herald[12] angels, to the shepherds and the little woolly white lambs of the Judean hills, were added not only Bo Peep and her flock, but Baa the black sheep, and the reindeer team of an unscriptural Saint Nicholas. But it was all Holy Writ to Will'm. Presently the mere thought of angels and stars and silver bells gave him such a big warm feeling inside, that he was brimming over with good-will to everybody.

When Libby came home from school a few minutes later, he was in the midst of his favorite game, one which he played at intervals all through the day. The game was Railroad Train, suggested naturally enough by the constant switching of cars and snorting of engines which went on all day and night at this busy Junction. It was one in which he could be a star performer in each part, as he personated fireman, engineer, conductor and passenger in turn. At the moment Libby came in he was the engine itself, backing, puffing and whistling, his arms going like piston-rods, and his pursed[13] up little mouth giving a very fair imitation of "letting off steam."

"Look out!" he called warningly. "You'll get runned over."

But instead of heeding his warning, Libby planted herself directly in the path of the oncoming engine, ignoring so completely the part he was playing that he stopped short in surprise. Ordinarily she would have fallen in with the game, but now she seemed blind and deaf to the fact that he was playing anything at all. Usually, coming in the back way, she left her muddy overshoes on the latticed porch, her lunch basket on the kitchen table, her wraps on their particular hook in the entry. She was an orderly little soul. But to-day she came in, her coat half off, her hood trailing down her back by its strings, and her thin little tails of tightly braided hair fuzzy and untied, from running bare-headed all the way home to tell the exciting news. She told it in gasps.

"You can write letters to Santa Claus—for whatever you want—and put them up[14] the chimney—and he gets them—and whatever you ask for he'll bring you—if you're good!"

Instantly the engine was a little boy again all a-tingle with this new delicious mystery of Christmastide. He climbed up into the rocking chair and listened, the rapt look on his face deepening. In proof of what she told, Libby had a letter all written and addressed, ready to send. One of the older girls had helped her with it at noon, and she had spent the entire afternoon recess copying it. Because she was just learning to write, she made so many mistakes that it had to be copied several times. She read it aloud to Will'm.

"Dear Santa Claus:—Please bring me a little shiny gold ring like the one that Maudie Peters wears. Yours truly, Libby Branfield."

"Now you watch, and you'll see me send it up the chimney when I get my muddy overshoes off and my hands washed. This might be one of the times when he'd be[15] looking down, and it'd be better for me to be all clean and tidy."

Breathlessly Will'm waited till she came back from the kitchen, her hands and face shining from the scrubbing she had given them with yellow laundry soap, her hair brushed primly back on each side of its parting and her hair ribbons freshly tied. Then she knelt on the rug, the fateful missive in her hand.

"Maudie is going to ask for 'most a dozen presents," she said. "But as long as this will be Santy's first visit to this house I'm not going to ask for more than one thing, and you mustn't either. It wouldn't be polite."

"But we can ask him to bring a ring to Dranma," Will'm suggested, his face beaming at the thought. The answer was positive and terrible out of her wisdom newly gained at both church and school.

"No, we can't! He only brings things to people who bleeve in him. It's the same way it is about going to Heaven. Only[16] those who bleeve will be saved and get in."

"Dranma and Uncle Neal will go to Heaven," insisted Will'm loyally, and in a tone which suggested his willingness to hurt her if she contradicted him. Uncle Neal was "Dranma's" husband.

"Oh, of course, they'll go to Heaven all right," was Libby's impatient answer. "They've got faith in the Bible and the minister and the heathen and such things. But they won't get anything in their stockings because they aren't sure about there even being a Santa Claus! So there!"

"Well, if Santa Claus won't put anything in my Dranma Neal's stocking, he's a mean old thing, and I don't want him to put anything in mine," began Will'm defiantly, but was silenced by the sight of Libby's horrified face.

"Oh, brother! Hush!" she cried, darting a frightened glance over her shoulder towards the chimney. Then in a shocked whisper which scared Will'm worse than a[17] loud yell would have done, she said impressively, "Oh, I hope he hasn't heard you! He never would come to this house as long as he lives! And I couldn't bear for us to find just empty stockings Christmas morning."

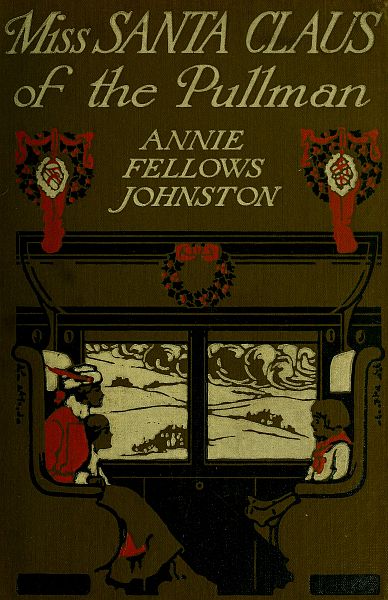

There was a tense silence. And then, still on her knees, her hands still clasped over the letter, she moved a few inches nearer the fireplace. The next instant Will'm heard her call imploringly up the chimney, "Oh, dear Santa Claus, if you're up there looking down, please don't mind what Will'm said. He's so little he doesn't know any better. Please forgive him and send us what we ask for, for Jesus' sake, Amen!"

Fascinated, Will'm watched the letter flutter up past the flames, drawn by the strong draught of the flue. Then suddenly shamed by the thought that he had been publicly prayed for, out loud and in the daytime, he ran to cast himself on the old lounge, face downward among the cushions.

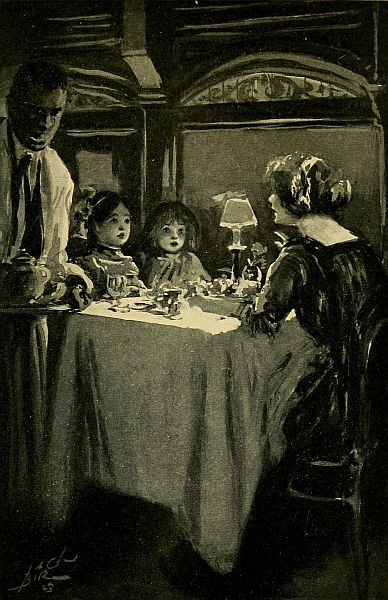

"Oh, dear Santa Claus"

"Oh, dear Santa Claus"

Libby herself felt a trifle constrained after her unusual performance, and to cover her embarrassment seized the hearth broom and vigorously swept up the scraps of half-dried mud which she had tracked in a little while before. Then she stood and drummed on the window pane a long time, looking out into the dusk which always came so surprisingly fast these short winter days, almost the very moment after the sun dropped down behind the cedar trees.

It was a relief to both children when

Grandma Neal came in with a lighted lamp.

Her cheerful call to know who was going to

help her set the supper table, gave Will'm

an excuse to spring up from the lounge

cushions and face his little world once more

in a natural and matter-of-course way. He

felt safer out in the bright warm kitchen.

No stern displeased eye could possibly peer

at him around the bend of that black shining

stove-pipe. There was comfort in the

savory steam puffing out from under the

lid of the stew-pan on the stove. There was[19]

[20]

[21]

reassurance in the clatter of the knives and

forks and dishes which he and Libby put

noisily in place on the table. But when

Grandma Neal started where she had

left off, to finish the story of the Camels and

the Star, he interrupted quickly to ask instead

for the tale of Goldilocks and the

Three Bears. The Christmas Spirit had

gone out of him. He could not listen to

the story of the Star. It lighted the way

not only of the camel caravan, but of the

Sky Road too, and he didn't want to be

reminded of that Sky Road now. He was

fearful that a cold displeasure might be

filling the throat of the sitting-room chimney.

If Santa Claus had happened to be

listening when he called him a mean old

thing, then had he ruined not only his own

chances, but Libby's too. That fear followed

him all evening. It made him

vaguely uncomfortable. Even when they

sat down to supper it did something to his

appetite, for the dumpling stew did not taste

as good as usual.

It is probable, too, that Will'm's state of body helped his state of mind, for about this time his cold was well enough for him to play out of doors, and the thought of stars and angels and silver bells began to be agreeable again. They gave him that big, warm feeling inside again; the Christmas feeling of good-will to everybody.

One morning he was sitting up on a post of the side yard fence, when the passenger train Number Four came rushing in to the station, and was switched back on a side track right across the road from him. It was behind time and had to wait there for orders or till the Western Flyer passed it, or for some such reason. It was a happy morning for Will'm. There was nothing he enjoyed so much as having one of these long Pullman trains stop where he could watch it. Night after night he and Libby had flattened their faces against the sitting-room window to watch the seven o'clock limited pass by. Through its brilliantly lighted windows they loved to see the passengers at[24] dinner. The white tables with their gleam of glass and shine of silver and glow of shaded lights seemed wonderful to them. More wonderful still was it to be eating as unconcernedly as if one were at home, with the train jiggling the tables while it leaped across the country at its highest speed. The people who could do such things must be wonderful too.

There were times when passengers flattening their faces against the glass to see why the train had stopped, caught the gleam of a cheerful home window across the road, and holding shielding hands at either side of their eyes, as they peered through the darkness, smiled to discover those two eager little watchers, who counted the stopping of the Pullman at this Junction as the greatest event of the day.

Will'm and Libby knew nearly every engineer and conductor on the road by sight, and had their own names for them. The engineer on this morning train they called Mr. Smiley, because he always had a cheerful[25] grin for them, and sometimes a wave of his big grimy hand. This time Mr. Smiley was too busy and too provoked by the delay to pay any attention to the small boy perched on the fence post. Some of the passengers finding that they might have to wait half an hour or more began to climb out and walk up and down the road past him. Several of them attracted by the wares in the window of the little notion shop which had once been a parlor, sauntered in and came out again, eating some of Grandma Neal's doughnuts. Presently Will'm noticed that everybody who passed a certain sleeping coach, stooped down and looked under it. He felt impelled to look under it himself and discover why. So he climbed down from the post and trudged along the road, kicking the rocks out of his way with stubby little shoes already scuffed from much previous kicking. At the same moment the steward of the dining-car stepped down from the vestibuled platform, and strolled towards him, with his hands in his trousers' pockets.

"Hullo, son!" he remarked good-humoredly in passing, giving an amused glance at the solemn child stuffed into a gray sweater and blue mittens, with a toboggan cap pulled down over his soft bobbed hair. Usually Will'm responded to such greetings. So many people came into the shop that he was not often abashed by strangers. But this time he was so busy looking at something that dangled from the steward's vest pocket that he failed to say "Hullo" back at him. It was what seemed to be the smallest gold watch he had ever seen, and it impressed him as very queer that the man should wear it on the outside of his pocket instead of the inside. He stopped still in the road and stared at it until the man passed him, then he turned and followed him slowly at a distance.

A few rods further on, the steward stooped and looked under the coach, and spoke to a man who was out of sight, but who was hammering on the other side. A voice called back something about a hot-box and cutting[27] out that coach, and reminded of his original purpose, Will'm followed on and looked, likewise. Although he squatted down and looked for a long time he couldn't see a single box, only the legs of the man who was hammering on the other side. But just as he straightened up again he caught the gleam of something round and shiningly golden, something no bigger than a quarter, lying almost between his feet. It was a tiny baby watch like the one that swung from the steward's vest pocket.

Thrilled by the discovery, Will'm picked it up and fondled it with both little blue mittens. It didn't tick when he held it to his ear, and he couldn't open it, but he was sure that Uncle Neal could open it and start it to going, and he was sure that it was the littlest watch in the world. It never occurred to him that finding it hadn't made it his own to have and to carry home, just like the rainbow-lined mussel shells that he sometimes picked up on the creek bank, or the silver dime he had once found in a wagon rut.

"Here!" he said

"Here!" he said

Then he looked up to see the steward strolling back towards him again, his hands still in his trousers' pockets. But this time no fascinating baby watch bobbed back and forth against his vest as he walked, and Will'm knew with a sudden stab of disappointment that was as bad as earache, that the watch he was fondling could never be his to carry home and show proudly to Uncle Neal. It belonged to the man.

"Here!" he said, holding it out in the blue mitten.

"Well, I vow!" exclaimed the steward, looking down at his watchfob, and then snatching the little disk of gold from the outstretched hand. "I wouldn't have lost that for hardly anything. It must have come loose when I stooped to look under the car. I think more of that than almost anything I've got. See?"

And then Will'm saw that it was not a

watch, but a little locket made to hang from

a bar that was fastened to a wide black ribbon

fob. The man pulled out the fob, and[29]

[30]

[31]

there on the other end, where it had been

in his pocket all the time, was a big watch,

as big as Will'm's fist. The locket flew

open when he touched a spring, and there

were two pictures inside. One of a lady and

one of a jolly, fat-cheeked baby.

"Well, little man!" exclaimed the steward, with a hearty clap on the shoulder that nearly upset him. "You don't know how big a favor you've done me by finding that locket. You're just about the nicest boy I've come across yet. I'll have to tell Santa Claus about you. What's your name?"

Will'm told him and pointed across to the shop, when asked where he lived. At the steward's high praise Will'm was ready to take the Sky Road himself, when he heard that he was to be reported to the Master of the Reindeer as the nicest boy the steward had come across. His disappointment vanished so quickly that he even forgot that he had been disappointed, and when the steward caught him under the arms and swung[32] him up the steps, saying something about finding an orange, he was thrilled with a wild brave sense of adventure.

Discovering that Will'm had never been on a Pullman since he could remember, the steward took him through the diner to the kitchen, showing him all the sights and explaining all the mysteries. It was as good as a show to watch the child's face. He had never dreamed that such roasting and broiling went on in the narrow space of the car kitchen, or that such quantities of eatables were stored away in the mammoth refrigerators which stood almost touching the red hot ranges. Big shining fish from far-off waters, such as the Junction had never heard of, lay blocked in ice in one compartment. Ripe red strawberries lay in another, although it was mid December, and in Will'm's part of the world strawberries were not to be thought of before the first of June. There were more eggs than all the hens at the Junction could lay in a week, and a white-capped, white-jacketed colored-man[33] was beating up a dozen or so into a white mountain of meringue, which the passengers would eat by and by in the shape of some strange, delicious dessert, sitting at those fascinating tables he had passed on his way in.

A quarter of an hour later when Will'm found himself on the ground again, gazing after the departing train, he was a trifle dazed with all he had seen and heard. But three things were clear in his mind. That he held in one hand a great yellow orange, in the other a box of prize pop-corn, and in his heart the precious assurance that Santa Claus would be told by one in high authority that he was a good boy.

So elated was he by this last fact, that he decided on the way home to send a letter up the chimney on his own account, especially as he knew now exactly what to ask for. He had been a bit hazy on the question before. Now he knew beyond all doubt that what he wanted more than anything in the wide world, was a ride on a Pullman car.[34] He wanted to sit at one of those tables, and eat things that had been cooked in that mysterious kitchen, at the same time that he was flying along through the night on the wings of a mighty dragon breathing out smoke and fire as it flew.

He went in to the house by way of the shop so that he might make the bell go ting-a-ling. It was so delightfully like the bells on the camels, also like the bells on the sleigh which would be coming before so very long to bring him what he wanted.

Miss Sally Watts was sitting behind the counter, crocheting. To his question of "Where's Dranma?" she answered without looking up.

"She and Mr. Neal have driven over to Westfield. They have some business at the court house. She said you're not to go off the place again till she gets back. I was to tell you when you came in. She looked everywhere to find you before she left, because she's going to be gone till late in the afternoon. Where you been, anyhow?"

Will'm told her. Miss Sally was a neighbor who often helped in the shop at times like this, and he was always glad when such times came. It was easy to tell Miss Sally things, and presently when a few direct questions disclosed the fact that Miss Sally "bleeved" as he did, he asked her another question, which had been puzzling him ever since he had decided to ask for a ride on the train.

"How can Santa put a ride in a stocking?"

"I don't know," answered Miss Sally, still intent on her crocheting. "But then I don't really see how he can put anything in; sleds or dolls or anything of the sort. He's a mighty mysterious man to me. But then, probably he wouldn't try to put the ride in a stocking. He'd send the ticket or the money to buy it with. And he might give it to you beforehand, and not wait for stocking-hanging time, knowing how much you want it."

All this from Miss Sally because Mrs.[36] Neal had just told her that the children were to be sent to their father the day before Christmas, and that they were to go on a Pullman car, because the ordinary coaches did not go straight through. The children were too small to risk changing cars, and he was too busy to come for them.

Will'm stayed in the shop the rest of the morning, for Miss Sally echoing the sentiment of everybody at the Junction, felt sorry for the poor little fellow who was soon to be sent away to a stepmother, and felt that it was her duty to do what she could toward making his world as pleasant as possible for him, while she had the opportunity.

Together they ate the lunch which had been left on the pantry shelves for them. Will'm helped set it out on the table. Then he went back into the shop with Miss Sally. But his endless questions "got on her nerves" after awhile, she said, and she suddenly ceased to be the good company that she had been all morning. She mended the fire in the sitting-room and told Will'm he'd[37] better play in there till Libby came home. It was an endless afternoon, so long that after he had done everything that he could think of to pass the time, he decided he'd write his own letter and send it up the chimney himself. He couldn't possibly wait for Libby to come home and do it. He'd write a picture letter. It was easier to read pictures than print, anyhow. At least for him. He slipped back into the shop long enough to get paper and a pencil from the old secretary in the corner, and then lying on his stomach on the hearth-rug with his heels in the air, he began drawing his favorite sketch, a train of cars.

All that can be said of the picture is that one could recognize what it was meant for. The wheels were wobbly and no two of the same size, the windows zigzagged in uneven lines and were of varied shapes. The cow-catcher looked as if it could toss anything it might pick up high enough to join the cow that jumped over the moon. But it was unmistakably a train, and the long line of[38] smoke pouring back over it from the tipsy smoke-stack showed that it was going at the top of its speed. Despite the straggling scratchy lines any art critic must acknowledge that it had in it that intangible quality known as life and "go."

It puzzled Will'm at first to know how to introduce himself into the picture so as to show that he was the one wanting a ride. Finally on top of one of the cars he drew a figure supposed to represent a boy, and after long thought, drew one just like it, except that the second figure wore a skirt. He didn't want to take the ride alone. He'd be almost afraid to go without Libby, and he knew very well that she'd like to go. She'd often played "S'posen" they were riding away off to the other side of the world on one of those trains which they watched nightly pass the sitting-room window.

He wished he could spell his name and hers. He knew only the letters with which each began, and he wasn't sure of either unless he could see the picture on the other[39] side of the building block on which it was printed. The box of blocks was in the sitting-room closet. He brought it out, emptied it on the rug and searched until he found the block bearing the picture of a lion. That was the king of beasts, and the L on the other side which stood for Lion, stood also for Libby. Very slowly and painstakingly he copied the letter on his drawing, placing it directly across the girl's skirt so that there could be no mistake. Then he pawed over the blocks till he found the one with the picture of a whale. That was the king of fishes, and the W on the other side which stood for Whale, stood also for William. He tried putting the W across the boy, but as each leg was represented by one straight line only, bent at right angles at the bottom to make a foot, the result was confusing. He rubbed out the legs, made them anew, and put the W over the boy's head, drawing a thin line from the end of the W to the crossed scratches representing fingers. That plainly showed that the Boy and the[40] W were one and the same, although it gave to the unenlightened the idea that the picture had something to do with flying a kite. Then he rubbed out the L on Libby's skirt and placed it over her head, likewise connecting her letter with her fingers.

The rubbing-out process gave a smudgy effect. Will'm was not satisfied with the result, and like a true artist who counts all labor as naught, which helps him towards that perfection which is his ideal, he laid aside the drawing as unworthy and began another.

The second was better. He accomplished it with a more certain touch and with no smudges, and filled with the joy of a creator, sat and looked at it a few minutes before starting it on its flight up the flue towards the Sky Road.

The great moment was over. He had just drawn back from watching it start when Libby came in. She came primly and quietly this time. She had waited to leave her overshoes on the porch, her lunch basket[41] in the kitchen, her wraps in the entry. The white ruffled apron which she had worn all day was scarcely mussed. The bows on her narrow braids stuck out stiffly and properly. Her shoes were tied and the laces tucked in. She walked on tiptoe, and every movement showed that she was keeping up the reputation she had earned of being "so good that nobody could be any better, no matter how hard he tried." She had been that good for over a week.

Will'm ran to get the orange which had been given him that morning. He had been saving it for this moment of division. He had already opened the pop-corn box and found the prize, a little china cup no larger than a thimble, and had used it at lunch, dipping a sip at a time from his glass of milk.

The interest with which she listened to his account of finding the locket and being taken aboard the train made him feel like a hero. He hastened to increase her respect.

"Nen the man said that I was about the nicest little boy he ever saw and he would[42] tell Santa Claus so. An' I knew everything was all right so I've just sended a letter up to tell him to please give me a ride on the Pullman train."

Libby smiled in an amused, big-sister sort of way, asking how Will'm supposed anybody could read his letters. He couldn't write anything but scratches.

"But it was a picture letter!" Will'm explained triumphantly. "Anybody can read picture letters." Then he proceeded to tell what he had made and how he had marked it with the initials of the Lion and the Whale.

To his intense surprise Libby looked first startled, then troubled, then despairing. His heart seemed to drop down into his shoes when she exclaimed in a tragic tone:

"Well, Will'm Branfield! If you haven't gone and done it! I don't know what ever is going to happen to us now!"

Then she explained. She had already written a letter for him, with Susie Peters's help, asking in writing what she had asked[43] before by word of mouth, that he be forgiven, and requesting that he might not find his stocking empty on Christmas morning. As to what should be in it, she had left that to Santa's generosity, because Will'm had never said what he wanted.

"And now," she added reproachfully, "I've told you that we oughtn't to ask for more than one thing apiece, 'cause this is the first time he's ever been to this house, and it doesn't seem polite to ask for so much from a stranger."

Will'm defended himself, his chin tilted at an angle that should have been a warning to one who could read such danger signals.

"I only asked for one thing for me and one for you."

"Yes, but don't you see, I had already asked for something for each of us, so that makes two things apiece," was the almost tearful answer.

"Well, I aren't to blame," persisted Will'm, "you didn't tell me what you'd done."

"But you ought to have waited and asked me before you sent it," insisted Libby.

"I oughtn't!"

"You ought, I say!" This with a stamp of her foot for emphasis.

"I oughtn't, Miss Smarty!" This time a saucy little tongue thrust itself out at her from Will'm's mouth, and his face was screwed into the ugliest twist he could make.

Again he had the shock of a great surprise, when Libby did not answer with a worse face. Instead she lifted her head a little, and said in a voice almost honey-sweet, but so loud that it seemed intended for other ears than Will'm's, "Very well, have your own way, brother, but Santa Claus knows that I didn't want to be greedy and ask for two things!"

William answered in what was fairly a shout, "An' he knows that I didn't, neether!"

The shout was followed by a whisper: "Say, Libby, do you s'pose he heard that?"

Libby's answer was a convincing nod.

She decided not to tell them that they were never coming back to the Junction to live. It would be better for them to think[46] of this return to their father as just a visit until they were used to their new surroundings. It would make it easier for all concerned if they could be started off happy and pleasantly expectant. Then if Molly had grown up to be as nice a woman as she had been a young girl, she could safely trust the rest to her. The children would soon be loving her so much that they wouldn't want to come back.

But Mrs. Neal had not taken into account that her news was no longer a secret. Told to one or two friends in confidence, it had passed from lip to lip and had been discussed in so many homes, that half the children at the Junction knew that poor little Libby and Will'm Branfield were to have a stepmother, before they knew it themselves. Maudie Peters told Libby on their way home from school one day, and told it in such a tone that she made Libby feel that having a stepmother was about the worst calamity that could befall one. Libby denied it stoutly.

"But you are!" Maudie insisted. "I heard mama and Aunt Louisa talking about it. They said they certainly felt sorry for you, and mama said that she hoped and prayed that her children would be spared such a fate, because stepmothers are always unkind."

Libby flew home with her tearful question, positive that Grandma Neal would say that Maudie was mistaken, but with a scared, shaky feeling in her knees, because Maudie had been so calmly and provokingly sure. Grandma Neal could deny only a part of Maudie's story.

"I'd like to spank that meddlesome Peters child!" she exclaimed indignantly. "Here I've been keeping it as a grand surprise for you that your father is going to give you a new mother for Christmas, and thinking what a fine time you'd have going on the cars to see them, and now Maudie has to go and tattle, and tell it in such an ugly way that she makes it seem like something bad, instead of the nicest[48] thing that could happen to you. Listen, Libby!"

For Libby, at this confirmation of Maudie's tale, instead of the denial which she hoped for, had crooked her arm over her face, and was crying out loud into her little brown gingham sleeve, as if her heart would break. Mrs. Neal sat down and drew the sobbing child into her lap.

"Listen, Libby!" she said again. "This lady that your father has married, used to live here at the Junction when she was a little girl no bigger than you. Her name was Molly Blair, and she looked something like you—had the same color hair, and wore it in two little plaits just as you do. Everybody liked her. She was so gentle and kind she wouldn't have done anything to hurt any one's feelings any more than a little white kitten would. Your father was a boy then, and he lived here, and they went to school together and played together just as you and Walter Gray do. He's known her all her life, and he knew very well when[49] he asked her to take the place of a mother to his little children that she'd be dear and good to you. Do you think that you could change so in growing up that you could be unkind to any little child that was put in your care?"

"No—o!" sobbed Libby.

"And neither could she!" was the emphatic answer. "You can just tell Maudie Peters that she doesn't know what she is talking about."

Libby repeated the message next day, emphatically and defiantly, with her chin in the air. That talk with Grandma Neal and another longer one which followed at bedtime, helped her to see things in their right light. Besides, several things which Grandma Neal told her made a visit to her father seem quite desirable. It would be fine to be in a city where there is something interesting to see every minute. She knew from other sources that in a city you might expect a hand-organ and a monkey to come down the street almost any day. And it[50] would be grand to live in a house like the one they were going to, with an up-stairs to it, and a piano in the parlor.

But despite Mrs. Neal's efforts to set matters straight, the poison of Maudie's suggestion had done its work. Will'm had been in the room when Libby came home with her question, and the wild way she broke out crying made him feel that something awful was going to happen to them. He had never heard of a stepmother before. By some queer association of words his baby brain confused it with a step-ladder. There was such a ladder in the shop with a broken hinge. He was always being warned not to climb up on it. It might fall over with him and hurt him dreadfully. Even when everything had been explained to him, and he agreed that it would be lovely to take that long ride on the Pullman to see poor father, who was so lonely without his little boy, the poison of Maudie's suggestion still stayed with him. Something, he didn't know exactly what, but something was going[51] to fall with him and hurt him dreadfully if he didn't look out.

It's strange how much there is to learn about persons after you once begin to hear of them. It had been that way about Santa Claus. They had scarcely known his name, and then all of a sudden they heard so much, that instead of being a complete stranger he was a part of everything they said and did and thought. Now they were learning just as fast about stepmothers. Grandma and Uncle Neal and Miss Sally told them a great deal; all good things. And it was surprising how much else they had learned that wasn't good, just by the wag of somebody's head, or a shrug of the shoulders or the pitying way some of the customers spoke to them.

When Libby came crying home from school the second time, because one of the boys called her Cinderella, and told her she would have to sit in the ashes and wear rags, and another one said no, she'd be like Snow-white, and have to eat poisoned apple,[52] Grandma Neal was so indignant that she sent after Libby's books, saying that she would not be back at school any more.

Next day, Libby told Will'm the rest of what the boys had said to her. "All the stepmothers in stories are cruel like Cinderella's and Snow-white's, and sometimes they are cruel. They are always cruel when they have a tusk." Susie Peters told her what a tusk is, and showed her a picture of a cruel hag that had one. "It's an awful long ugly tooth that sticks away out of the side of your mouth like a pig's."

It was a puzzle for both Libby and Will'm to know whom to believe. They had sided with Maudie and the others in their faith in Santa Claus. How could they tell but that Grandma and Uncle Neal might be mistaken about their belief in stepmothers too?

Fortunately there were not many days in which to worry over the problem, and the few that lay between the time of Libby's leaving school and their going away, were filled with preparations for the journey.[53] Of course Libby and Will'm had little part in that, except to collect the few toys they owned, and lay them beside the trunk which had been brought down from the attic to the sitting-room.

Libby had a grand washing of doll clothes one morning, and while she was hanging out the tiny garments on a string, stretched from one chair-back to another, Will'm proceeded to give his old Teddy Bear a bath in the suds which she had left in the basin. Plush does not take kindly to soap-suds, no matter how much it needs it. It would have been far better for poor Teddy to have started on his travels dirty, than to have become the pitiable, bedraggled-looking object that Libby snatched from the basin some time later, where Will'm put him to soak. It seemed as if the soggy cotton body never would dry sufficiently to be packed in the trunk, and Will'm would not hear to its being left behind, although it looked so dreadful that he didn't like to touch it. So it hung by a cord around its[54] neck in front of the fire for two whole days, and everybody who passed it gave the cord a twist, so that it was kept turning like a roast on a spit.

There were more errands than usual to keep the children busy, and more ways in which they could help. As Christmas drew nearer and nearer somebody was needed in the shop every minute, and Mrs. Neal had her hands full with the extra work of looking over their clothes and putting every garment in order. Besides there was all the holiday baking to fill the shelves in the shop as well as in her own pantry.

So the children were called upon to set the table and help wipe the dishes. They dusted the furniture within their reach and fed the cat. They brought in chips from the woodhouse and shelled corn by the basketful for the old gray hens. And every day they carried the eggs very slowly and carefully from the nests to the pantry and put them one by one into the box of bran on the shelf. Then several mornings, all[55] specially scrubbed and clean-aproned for the performance, they knelt on chairs by the kitchen table, and cut out rows and rows of little Christmas cakes, from the sheets of smoothly rolled dough on the floury cake boards. There were hearts and stars and cats and birds and all sorts of queer animals. Then after the baking there were delightful times when they hung breathlessly over the table, watching while scallops of pink or white icing were zigzagged around the stars and hearts, and pink eyes were put on the beasts and birds. Then of course the bowls which held the candied icing always had to be scraped clean by busy little fingers that went from bowl to mouth and back again, almost as fast as a kitten could lap with its pink tongue.

Oh, those last days in the old kitchen and sitting-room behind the shop were the best days of all, and it was good that Will'm and Libby were kept so busy every minute that they had no time to realize that they were last days, and that they were rapidly coming[56] to an end. It was not until the last night that Will'm seemed to comprehend that they were really going away the next day.

"Oh, rabbit dravy!" he cried

"Oh, rabbit dravy!" he cried

He had been very busy helping get supper, for it was the kind that he specially liked. Uncle Neal had brought in a rabbit all ready skinned and dressed, which he had trapped that afternoon, and Will'm had gone around the room for nearly an hour, sniffing hungrily while it sputtered and browned in the skillet, smelling more tempting and delectable every minute. And he had watched while Grandma Neal lifted each crisp, brown piece up on a fork, and laid it on the hot waiting platter, and then stirred into the skillet the things that go to the making of a delicious cream gravy.

Suddenly in the ecstasy of anticipation Will'm was moved to throw his arms around Grandma Neal's skirts, gathering them in about her knees in such a violent hug that he almost upset her.

"Oh, rabbit dravy!" he exclaimed in a tone[57]

[58]

[59]

of such rapture that everybody laughed.

Uncle Neal, who had already taken his

place at the table, and was waiting too, with

his chair tipped back on its hind legs,

reached forward and gave Will'm's cheek a

playful pinch.

"It's easy to tell what you think is the best tasting thing in the world," he said teasingly. "Just the smell of it puts the smile on your face that won't wear off."

Always when his favorite dish was on the table, Will'm passed his plate back several times for more. To-night after the fourth ladleful Uncle Neal hesitated. "Haven't you had about all that's good for you, kiddo?" he asked. "Remember you're going away in the morning, and you don't want to make yourself sick when you're starting off with just Libby to look after you."

There was no answer for a second. Then Will'm couldn't climb out of his chair fast enough to hide the trembling of his mouth and the gathering of unmanly tears. He[60] cast himself across Mrs. Neal's lap, screaming, "I aren't going away! I won't leave my Dranma, and I won't go where there'll never be any more good rabbit dravy!"

They quieted him after awhile, and comforted him with promises of the time when he should come back and be their little boy again, but he did not romp around as usual when he started to bed. He realized that when he came again maybe the little crib-bed would be too small to hold him, and things would never be the same again.

Libby was quiet and inwardly tearful for another reason. They were to leave the very day on the night of which people hung up their stockings. Would Santa Claus know of their going and follow them? Will'm would be getting what he asked for, a ride on the Pullman, but how was she to get her gold ring? She lay awake quite a long while, worrying about it, but finally decided that she had been so good, so very good, that Santa would find some way to keep his part of the bargain. She hadn't[61] even fussed and rebelled about going back to her father as Maudie had advised her to do, and she had helped to persuade Will'm to accept quietly what couldn't be helped.

The bell over the shop door went ting-a-ling many times that evening to admit belated customers, and as she grew drowsier and drowsier it began to sound like those other bells which would go tinkling along the Sky Road to-morrow night. Ah, that Sky Road! She wouldn't worry, remembering that the Christmas Angels came along that shining highway too. Maybe her heart's desire would be brought to her by one of them!

If Miss Sally had not suggested that something might happen, Libby might not have had her fears aroused, and if they had been allowed to travel all the way in the[63] toilet-room which Miss Sally and Grandma Neal showed them while the train waited its usual ten minutes at the Junction, they could have kept themselves too busy to think about the perils of pilgrimage. Never before had they seen water spurt from shining faucets into big white basins with chained-up holes at the bottom. It suggested magic to Libby, and she thought of several games they could have made, if they had not been hurried back to their seats in the car, and told that they must wait until time to eat, before washing their hands.

"I thought best to tell them that," said Miss Sally, as she and Mrs. Neal went slowly back to the shop. "Or Libby might have had most of the skin scrubbed off her and Will'm before night. And I know he'd drink the water cooler dry just for the pleasure of turning it into his new drinking cup you gave him, if he hadn't been told not to. Well, they're off, and so interested in everything that I don't believe they realized they were starting. There wasn't[64] time for them to think that they were really leaving you."

"There'll be time enough before they get there," was the grim answer. "I shouldn't wonder if they both get to crying."

Then for fear that she should start to doing that same thing herself, she left Miss Sally to attend to the shop, and went briskly to work, putting the kitchen to rights. She had left the breakfast dishes until after the children's departure, for she had much to do for them, besides putting up two lunches. They left at ten o'clock, and could not reach their journey's end before half past eight that night. So both dinner and supper were packed in the big pasteboard box which had been stowed away under the seat with their suitcase.

Miss Sally was right about one thing. Neither child realized at first that the parting was final, until the little shop was left far behind. The novelty of their surroundings and their satisfaction at being really on board one of the wonderful cars which they[65] had watched daily from the sitting-room window, made them feel that their best "S'posen" game had come true at last. But they hadn't gone five miles until the landscape began to look unfamiliar. They had never been in this direction before, toward the hill country. Their drives behind Uncle Neal's old gray mare had always been the other way. Five miles more and they were strangers in a strange land. Fifteen miles, and they were experiencing the bitterness of "exiles from home" whom "splendor dazzles in vain." There was no charm left in the luxurious Pullman with its gorgeous red plush seats and shining mirrors. All the people they could see over the backs of those seats or reflected in those mirrors were strangers.

It made them even more lonely and aloof because the people did not seem to be strangers to each other. All up and down the car they talked and joked as people in this free and happy land always do when it's the day before Christmas and they are[66] going home, whether they know each other or not. To make matters worse some of these strangers acted as if they knew Will'm and Libby, and asked them questions or snapped their fingers at them in passing in a friendly way. It frightened Libby, who had been instructed in the ways of travel, and she only drew closer to Will'm and said nothing when these strange faces smiled on her.

Presently Will'm gave a little muffled sob and Libby put her arm around his neck. It gave him a sense of protection, but it also started the tears which he had been fighting back for several minutes, and drawing himself up into a bunch of misery close beside her, he cried softly, his face hidden against her shoulder. If it had been a big capable shoulder, such as he was used to going to for comfort, the shower would have been over soon. But he felt its limitations. It was little and thin, only three years older and wiser than his own; as a support through unknown dangers not much to depend upon,[67] still it was all he had to cling to, and he clung broken-heartedly and with scalding tears.

As for Libby she was realizing its limitations far more than he. His sobs shook her every time they shook him, and she could feel his tears, hot and wet on her arm through her sleeve. She started to cry herself, but fearing that if she did he might begin to roar so that they would be disgraced before everybody in the car, she bravely winked back her own tears and took an effective way to dry his.

Miss Sally had told them not to wash before it was time to eat, but of course Miss Sally had not known that Will'm was going to cry and smudge his face all over till it was a sight. If she couldn't stop him somehow he'd keep on till he was sick, and she'd been told to take care of him. The little shoulder humped itself in a way that showed some motherly instinct was teaching it how to adjust itself to its new burden of responsibility, and she said in a comforting way,

"Come on, brother, let's go and try what it's like to wash in that big white basin with the chained-up hole in the bottom of it."

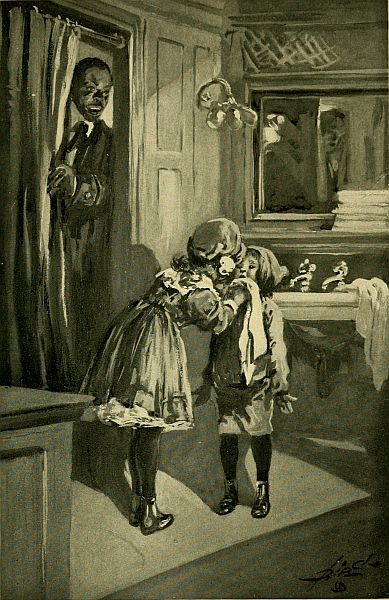

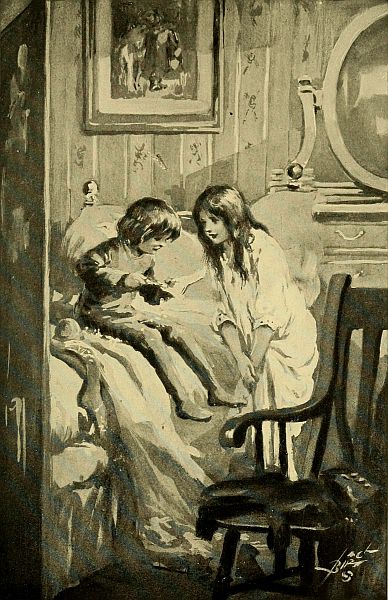

He pushed aside the red plush curtain and looked in

He pushed aside the red plush curtain and looked in

There was a bowl apiece, and for the first five minutes their hands were white ducks swimming in a pond. Then the faucets were shining silver dragons, spouting out streams of water from their mouths to drown four little mermaids, who were not real mermaids, but children whom a wicked witch had changed to such and thrown into a pool. Then they blew soap-bubbles through their hands, till Will'm's squeal of delight over one especially fine bubble, which rested on the carpet a moment, instead of bursting, brought the porter to the door to see what was the matter.

They were not used to colored people.

He pushed aside the red plush curtain and

looked in, but the bubble had vanished, and

all he saw was a slim little girl of seven

snatching up a towel to polish the red cheeks

of a chubby boy of four. When they went

back to their seats their finger tips were curiously[69]

[70]

[71]

wrinkled from long immersion in the

hot soap-suds, but the ache was gone out of

their throats, and Libby thought it might

be well for them to eat their dinner while

their hands were so very clean. It was only

quarter past eleven, but it seemed to them

that they had been traveling nearly a whole

day.

A chill of disappointment came to Will'm when his food was handed to him out of a pasteboard box. He had not thought to eat it in this primitive fashion. He had expected to sit at one of the little tables, but Libby didn't know what one had to do to gain the privilege of using them. The trip was not turning out to be all he had fondly imagined. Still the lunch in the pasteboard box was not to be despised. Even disappointment could not destroy the taste of Grandma Neal's chicken sandwiches and blackberry jam.

By the time they had eaten all they wanted, and tied up the box and washed their hands again (no bubbles and games[72] this time for fear of the porter) it had begun to snow, and they found entertainment in watching the flakes that swirled against the panes in all sorts of beautiful patterns. They knelt on opposite seats, each against a window. Sometimes the snow seemed to come in sheets, shutting out all view of the little hamlets and farm houses past which they whizzed, with deep warning whistles, and sometimes it lifted to give them glimpses of windows with holly wreaths hanging from scarlet bows, and eager little faces peering out at the passing train—the way theirs used to peer, years ago, it seemed, before they started on this endless journey.

It makes one sleepy to watch the snow fall for a long time. After awhile Will'm climbed down from the window and cuddled up beside Libby again, with his soft bobbed hair tickling her ear, as he rested against her. He went to sleep so, and she put her arm around his neck again to keep him from slipping. The card with which Miss Sally had tagged him, slid along its cord and stuck[73] up above his collar, prodding his chin. Libby pushed it back out of sight and felt under her dress for her own. They must be kept safely, "in case something should happen." She wondered what Miss Sally meant by that. What could happen? Their own Mr. Smiley was on the engine, and the conductor had been asked to keep an eye on them.

Then her suddenly awakened fear began to suggest answers. Maybe something might keep her father from coming to meet them. She and Will'm wouldn't know what to do or where to go. They'd be lost in a great city like the little Match Girl was on Christmas eve, and they'd freeze to death on some stranger's doorstep. There was a picture of the Match Girl thus frozen, in the Hans Andersen book which Susie Peters kept in her desk at school. There was a cruel stepmother picture in the same book, Libby remembered, and recollections of that turned her thoughts into still deeper channels of foreboding. What would she be[74] like? What was going to happen to her and Will'm at the end of this journey if it ever came to an end? If only they could be back at the Junction, safe and sound—

The tears began to drip slowly. She wiped them away with the back of the hand that was farthest away from Will'm. She was miserable enough to die, but she didn't want him to wake up and find it out. A lady who had been watching her for some time, came and sat down in the opposite seat and asked her what was the matter, and if she was crying because she was homesick, and what was her name and how far they were going. But Libby never answered a single question. The tears just kept dripping and her mouth working in a piteous attempt to swallow her sobs, and finally the lady saw that she was frightening her, and only making matters worse by trying to comfort her, so she went back to her seat.

When Will'm wakened after a while and sat up, leaving Libby's arm all stiff and prickly from being bent in one position so[75] long, the train had been running for miles through a lonely country where nobody seemed to live. Just as he rubbed his eyes wide awake they came to a forest of Christmas trees. At least, they looked as if all they needed to make them that, was for some one to fasten candles on their snow-laden boughs. Then the whistle blew the signal that meant that the train was about to stop, and Will'm scrambled up on his knees again, and they both looked out expectantly.

There was no station at this place of stopping. Only by special order from some high official did this train come to a halt here, so somebody of importance must be coming aboard. All they saw at first was a snowy road opening through the grove of Christmas trees, but standing in this road, a few rods from the train, was a sleigh drawn by two big black horses. They had bells on their bridles which went ting-a-ling whenever they shook their heads or pawed the snow. The children could not see a trunk being put into the baggage car farther up[76] the track, but they saw what happened in the delay.

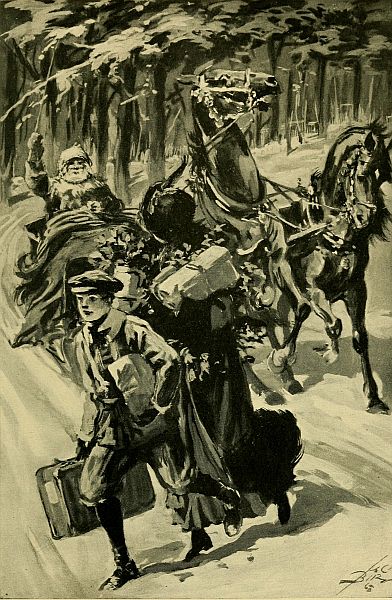

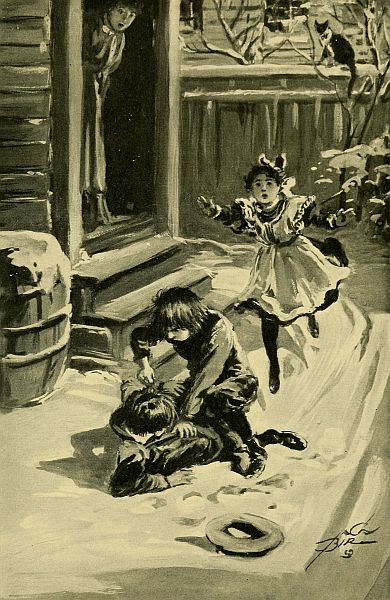

And ran after the boy as hard as she could go

And ran after the boy as hard as she could go

A half-grown boy, a suitcase in one hand and a pile of packages in his arms, dashed towards the car, leaving a furry old gentleman in the sleigh to hold the horses. The old gentleman's coat was fur, and his cap was fur, and so was the great rug which covered him. Under the fur cap was thick white hair, and all over the bottom of his face was a bushy white beard. And his cheeks were red and his eyes were laughing, and if he wasn't Santa Claus's own self he certainly looked enough like the nicest pictures of him to be his own brother.

On the seat beside him was a young girl,

who, waiting only long enough to plant a kiss

on one of those rosy cheeks above the snowy

beard, sprang out of the sleigh and ran after

the boy as hard as she could go. She was

not more than sixteen, but she looked like a

full-grown young lady to Libby, for her

hair was tucked up under her little fur cap[77]

[78]

[79]

with its scarlet quill, and the long, fur-bordered

red coat she wore, reached her

ankles. One hand was thrust through a

row of holly wreaths, and she was carrying

all the bundles both arms could hold.

By the time the boy had deposited his load in the section opposite the children's, and dashed back down the aisle, there was a call of "All aboard!" They met at the door, he and the pretty girl, she laughing and nodding her thanks over her pile of bundles. He raised his hat and bolted past, but stopped an instant, just before jumping off the train, to run back and thrust his head in the door and call out laughingly, "Good-by, Miss Santa Claus!"

Everybody in the car looked up and smiled, and turned and looked again as she went up the aisle, for a lovelier Christmas picture could not be imagined than the one she made in her long red coat, her arms full of packages and wreaths of holly. The little fur cap with its scarlet feather was powdered with snow, and the frosty wind had[80] brought such a glow to her cheeks and a sparkle in her eyes that she looked the living embodiment of Christmas cheer. Her entrance seemed to bring with it the sense of all holiday joy, just as the cardinal's first note holds in it the sweetness of a whole spring.

Will'm edged along the seat until he was close beside Libby, and the two sat and stared at her with wide-eyed interest.

That boy had called her Miss Santa Claus!

If the sleigh which brought her had been drawn by reindeer, and she had carried her pack on her back instead of in her arms, they could not have been more spellbound. They scarcely breathed for a few moments. The radiant, glowing creature took off the long red coat and gave it to the porter to hang up, then she sat down and began sorting her packages into three piles. It took some time to do this, as she had to refer constantly to a list of names on a long strip of paper, and compare them with the names on[81] the bundles. While she was doing this the conductor came for her ticket and she asked several questions.

Yes, he assured her, they were due at Eastbrook in fifteen minutes and would stop there long enough to take water.

"Then I'll have plenty of time to step off with these things," she said. "And I'm to leave some at Centreville and some at Ridgely."

When the conductor said something about helping Santa Claus, she answered laughingly, "Yes, Uncle thought it would be better for me to bring these breakable things instead of trusting them to the chimney route." Then in answer to a question which Libby did not hear, "Oh, that will be all right. Uncle telephoned all down the line and arranged to have some one meet me at each place."

When the train stopped at Eastbrook, both the porter and conductor came to help her gather up her first pile of parcels, and people in the car stood up and craned their necks[82] to see what she did with them. Libby and Will'm could see. They were on the side next to the station. She gave them to several people who seemed to be waiting for her. Almost immediately she was surrounded by a crowd of young men and girls, all shaking hands with her and talking at once. From the remarks which floated in through the open vestibule, it seemed that they all must have been at some party with her the night before. A chorus of good-byes and Merry Christmases followed her into the car when she had to leave them and hurry aboard. This time she came in empty handed, and this time people looked up and smiled openly into her face, and she smiled back as if they were all friends, sharing their good times together.

At Centreville she darted out with the second lot. Farther down a number of people were leaving the day coaches, but no one was getting off the Pullman. She did not leave the steps, but leaned over and called to an old colored-man who stood with[83] a market basket on his arm. "This way, Mose. Quick!"

Then Will'm and Libby heard her say: "Tell 'Old Miss' that Uncle Norse sent this holly. He wanted her to have it because it grew on his own place and is the finest in the country. Don't knock the berries off, and do be careful of this biggest bundle. I wouldn't have it broken for anything. And—oh, yes, Mose" (this in a lower tone), "this is for you."

What it was that passed from the little white hand into the worn brown one of the old servitor was not discovered by the interested audience inside the car, but they heard a chuckle so full of pleasure that some of them echoed it unconsciously.

"Lawd bless you, li'l' Miss, you sho' is the flowah of the Santa Claus fambly!"

When she came in this time, a motherly old lady near the door stopped her, and smiling up at her through friendly spectacles, asked if she were going home for Christmas.

"Yes!" was the enthusiastic answer.[84] "And you know what that means to a Freshman—her first homecoming after her first term away at school. I should have been there four days ago. Our vacation began last Friday, but I stopped over for a house-party at my cousin's. I was wild to get home, but I couldn't miss this visit, for she's my dearest chum as well as my cousin, and last night was her birthday. Maybe you noticed all those people who met me at Eastbrook. They were at the party."

"That was nice," answered the little old lady, bobbing her head. "Very nice, my dear. And now you'll be getting home at the most beautiful time in all the year."

"Yes, I think so," was the happy answer. "Christmas eve to me always means going around with father to take presents, and I wouldn't miss it for anything in the world. I'm glad there's enough snow this year for us to use the sleigh. We had to take the auto last year, and it wasn't half as much fun."

Libby and Will'm scarcely moved after[85] that, all the way to Ridgely. Nor did they take their eyes off her. Mile after mile they rode, barely batting an eyelash, staring at her with unabated interest. At Ridgely she handed off all the rest of the packages and all of the holly wreaths but two. These she hung up out of the way over her windows, then taking out a magazine, settled herself comfortably in the end of the seat to read.

On her last trip up the aisle she had noticed the wistful, unsmiling faces of her little neighbors across the way, and she wondered why it was that the only children in the coach should be the only ones who seemed to have no share in the general joyousness. Something was wrong, she felt sure, and while she was cutting the leaves of the magazine, she stole several glances in their direction. The little girl had an anxious pucker of the brows sadly out of place in a face that had not yet outgrown its baby innocence of expression. She looked so little and lorn and troubled about something, that Miss Santa Claus made up her mind to comfort her as soon as[86] she had an opportunity. She knew better than to ask for her confidence as the well-meaning lady had done earlier in the day.

When she began to read, Will'm drew a long breath and stretched himself. There was no use watching now when it was evident that she wasn't going to do anything for awhile, and sitting still so long had made him fidgety. He squirmed off the seat, and up into the next one, unintentionally wiping his feet on Libby's dress as he did so. It brought a sharp reproof from the overwrought Libby, and he answered back in the same spirit.

Neither was conscious that their voices could be heard across the aisle above the noise of the train. The little fur cap with the scarlet feather bent over the magazine without the slightest change in posture, but there was no more turning of pages. The piping, childish voices were revealing a far more interesting story than the printed one the girl was scanning. She heard her own[87] name mentioned. They were disputing about her.

Too restless to sit still, and with no way in which to give vent to his all-consuming energy, Will'm was ripe for a squabble. It came very soon, and out of many allusions to past and present, and dire threats as to what might happen to him at the end of the journey if he didn't mend his ways, the interested listener gathered the principal facts in their history. The fuss ended in a shower of tears on Will'm's part, and the consequent smudging of his face with his grimy little hands which wiped them away, so that he had to be escorted once more behind the curtain to the shining faucets and the basin with the chained-up hole at the bottom.

When they came back Miss Santa Claus had put away her magazine and taken out some fancy work. All she seemed to be doing was winding some red yarn over a pencil, around and around and around. But presently she stopped and tied two ends with[88] a jerk, and went snip, snip with her scissors, and there in her fingers was a soft fuzzy ball. When she had snipped some more, and trimmed it all over, smooth and even, it looked like a little red cherry. In almost no time she had two wool cherries lying in her lap. She was just beginning the third when the big ball of yarn slipped out of her fingers, and rolled across the aisle right under Libby's feet. She sprang to pick it up and take it back.

"Thank you, dear," was all that Miss Santa Claus said, but such a smile went with it, that Libby, smoothing her skirts over her knees as she primly took her seat again, felt happier than she had since leaving the Junction. It wasn't two minutes till the ball slipped and rolled away again. This time Will'm picked it up, and she thanked him in the same way. But very soon when both scissors and ball spilled out of her lap and Libby politely brought her one and Will'm the other, she did not take them.

"I wonder," she said, "if you children[89] couldn't climb up here on the seat with me and hold this old Jack and Jill of a ball and scissors. Every time one falls down and almost breaks its crown, the other goes tumbling after. I'm in such a hurry to get through. Couldn't you stay and help me a few minutes?"

"Yes, ma'am," said Libby, primly and timidly, sitting down on the edge of the opposite seat with the ball in her hands. Miss Santa Claus put an arm around Will'm and drew him up on the seat beside her. "There," she said. "You hold the scissors, Will'm, and when I'm through winding the ball that Libby holds, I'll ask you to cut the yarn for me. Did you ever see such scissors, Libby? They're made in the shape of a witch. See! She sits upon the handles, and when the blades are closed they make the peak of her long pointed cap. They came from the old witch town of Salem."

Libby darted a half-frightened look at her. She had called them both by name! Had she been listening down the chimney,[90] too? And those witch scissors! They looked as if they might be a charm to open all sorts of secrets. Maybe she knew some charm to keep stepmothers from being cruel. Oh, if she only dared to ask! Of course Libby knew that one mustn't "pick up" with strangers and tell them things. Miss Sally had warned her against that. But this was different. Miss Santa Claus was more than just a person.

If Pan were to come piping out of the woods, who, with any music in him, would not respond with all his heart to the magic call? If Titania were to beckon with her gracious wand, who would not be drawn into her charmèd circle gladly? So it was these two little wayfarers heard the call and swayed to the summons of one who not only shed the influence, but shared the name of the wonderful Spirit of Yule.

"There!" she exclaimed, holding it up for them to admire. "That is to go in the stocking of a poor little fellow no larger than Will'm. He's lame and has to stay in bed all the time, and he asked Santa Claus to bring him something soft and warm to put[92] on when he is propped up in bed to look at his toys."

Out of a dry throat Libby at last brought up the question she had been trying to find courage for.

"Is Santa Claus your father?"

"No, but father and Uncle Norse are so much like him that people often get them all mixed up, just as they do twins, and since Uncle Santa has grown so busy, he gets father to attend to a great deal of his business. In fact our whole family has to help. He couldn't possibly get around to everybody as he used to when the cities were smaller and fewer. Lately he has been leaving more and more of his work to us. He's even taken to adopting people into his family so that they can help him. In almost every city in the world now, he has an adopted brother or sister or relative of some sort, and sometimes children not much bigger than you, ask to be counted as members of his family. It's so much fun to help."

Libby pondered over this news a moment[93] before she asked another question. "Then does he come to see them and tell them what to do?"

"No, indeed! Nobody ever sees him. He just sends messages, something like wireless telegrams. You know what they are?"

Libby shook her head. She had never heard of them. Miss Santa Claus explained. "And his messages pop into your head just that way," she added. "I was as busy as I could be one day, studying my Algebra lesson, when all of a sudden, pop came the thought into my head that little Jamie Fitch wanted a warm red jacket to wear when he sat up in bed, and that Uncle Santa wanted me to make it. I went down town that very afternoon and bought the wool, and I knew that I was not mistaken by the way I felt afterward, so glad and warm and Christmasy. That's why all his family love to help him. He gives them such a happy feeling while they are doing it."

It was Will'm's turn now for a question.[94] He asked it abruptly with a complete change of base.

"Did you ever see a stepmother?"

"Yes, indeed! And Cousin Rosalie has one. She's Uncle Norse's wife. I've just been visiting them."

"Has she got a tush?"

"A what?" was the astonished answer.

"He means tusk," explained Libby. "All the cruel ones have'm, Susie Peters says."

"Sticking out this way, like a pig's," Will'm added eagerly, at the same time pulling his lip down at one side to show a little white tooth in the place where the dreadful fang would have grown, had he been the cruel creature in question.

"Mercy, no!" was the horrified exclamation. "That kind live only in fairy tales along with ogres and giants. Didn't you know that?"

Will'm shook his head. "Me an' Libby was afraid ours would be that way, and if she is we're going to do something to her.[95] We're going to shut her up in a nawful dark cellar, or—or something."

Miss Santa looked grave. Here was a dreadful misunderstanding. Somebody had poisoned these baby minds with suspicions and doubts which might embitter their whole lives. If she had been only an ordinary fellow passenger she might not have felt it her duty to set them straight. But no descendant of the family of which she was a member, could come face to face with such a wrong, without the impulse to make it right. It was an impulse straight from the Sky Road. In the carol service in the chapel, the night before she left school, the dean had spoken so beautifully of the way they might all follow the Star, this Christmastide, with their gifts of frankincense and myrrh, even if they had no gold. Here was her opportunity, she thought, if she were only wise enough to say the right thing!

Before she could think of a way to begin, a waiter came through the car, sounding the first call for dinner. Time was flying.[96] She'd have to hurry, and make the most of it before the journey came to an end. Putting the little crocheted jacket back into her suitcase and snapping the clasps she stood up.

"Come on," she said, holding out a hand to each. "We'll go into the dining-car and get something to eat."

Libby thought of the generous supper in the pasteboard box which they had been told to eat as soon as it was dark, but she allowed herself to be led down the aisle without a word. A higher power was in authority now. She was as one drawn into a fairy ring.

Now at last, the ride on the Pullman blossomed into all that Will'm had pictured it to be. There was the gleam of glass, the shine of silver, the glow of shaded candles, and himself at one of the little tables, while the train went flying through the night like a mighty winged dragon, breathing smoke and fire as it flew.

Miss Santa Claus studied the printed card[97] beside her plate a moment, and then looked into her pocketbook before she wrote the order. She smiled a little while she was writing it. She wanted to make this meal one that they would always remember, and was sure that children who lived at such a place as the Junction had never before eaten strawberries on Christmas eve; a snow-covered Christmas eve at that. She had been afraid for just a moment, when she first peeped into her purse, that there wasn't enough left for her to get them.