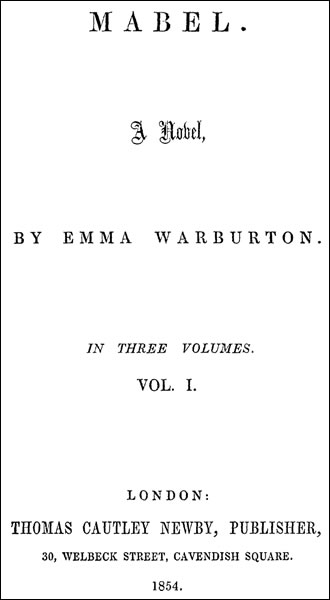

MABEL.

BY EMMA WARBURTON.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

THOMAS CAUTLEY NEWBY, PUBLISHER,

30, WELBECK STREET, CAVENDISH SQUARE.

1854.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mabel, Vol. I (of 3), by Emma Warburton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Mabel, Vol. I (of 3)

A Novel

Author: Emma Warburton

Release Date: December 5, 2012 [EBook #41564]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MABEL, VOL. I (OF 3) ***

Produced by Robert Cicconetti, Veronika Redfern and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

| CHAPTER I. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | 30 |

| CHAPTER III. | 47 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 64 |

| CHAPTER V. | 91 |

| CHAPTER VI. | 109 |

| CHAPTER VII. | 135 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 151 |

| CHAPTER IX. | 176 |

| CHAPTER X. | 187 |

| CHAPTER XI. | 205 |

| CHAPTER XII. | 219 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | 241 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | 276 |

| CHAPTER XV. | 296 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | 307 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | 325 |

TO

MISS EMMA TYLNEY LONG,

THIS WORK

IS INSCRIBED

AS A SLIGHT BUT SINCERE EXPRESSION

OF GRATEFUL ESTEEM.

Oh, timely, happy, timely wise,

Hearts that with rising morn arise,

Eyes that the beam celestial view,

Which evermore makes all things new.

New every morning is the love,

Our waking and uprising prove,

Through sleep and darkness safely brought,

Restored to life, and power, and thought.

Keeble.

One morning, early in the month of August, a few years since, the sun rose lazily and luxuriously over the hills that bounded the little[2] village of Aston, which lay in one of the prettiest valleys of Gloucestershire. The golden beams of that glorious luminary falling first upon the ivy-covered tower of the little church, seemed, to the eye of fancy, to linger with pleasure round the sacred edifice, as if glad to recognize the altar of Him, who, from the beginning, had fixed his daily course through the bright circle of the heavens, then pouring a flood of brilliancy on the simple rectory, danced over the hills, and played with the many windows of the old Manor House, which, situated at a short distance from the church, formed one of the most striking objects of the village.

Only here and there a thick volume of smoke rose from the cottages scattered over the valley, while the only living object visible was a young man, who thus early walked down the steep and winding path, which led from the rectory, and strolled leisurely forward, as if attracted by the beauties of the early morning.[3] The slow pace with which he moved seemed to betoken either indolence or fatigue, while his dress, which was of the latest fashion, slightly contrasted with the ancient-looking simplicity of the place.

Captain Clair, for such was his name, had quitted his regiment, then in India, and returned to England, with the hope of recruiting his health, which had been considerably impaired by his residence abroad.

On the preceding evening, he had arrived at the rectory, upon a visit to his uncle, who wished him to try the bracing air of Gloucestershire as a change from town, where he had been lingering for some little time since his return to England.

In person, the young officer was slight and well made, with a becoming military air; his countenance light and fresh colored, spite of Indian suns, and, on the whole, prepossessing, though not untinged by certain worldly characters,[4] as if he had entered perhaps too thoughtlessly on a world of sin and temptation.

There is, however, something still and holy in the early morning, when the sin and folly of nature has slept, or seemed to sleep, and life again awakes with fresh energy to labor. The dew from heaven has not fallen upon the herb alone, it seems to rest upon the spirit of man which rises full of renewed strength to that toil before which it sank heavily at eve; and as Captain Clair felt the breeze rising with its dewy incense to heaven, his mind seemed to receive fresh impetus, and his thoughts a higher tone. Languidly as he pursued his way, his eye drank in the beauties of a new country, with all the fervour of a poetical imagination.

On the right and left of the village, as he entered it, were high hills, covered with brushwood, a few cottages, with their simple gardens, lay in the hollow, and the church, standing[5] nearly alone, was built a little above these, having the hill on the left immediately behind it. There was great beauty in that simple church, with that thickly covered hill above, and nothing near to disturb its solemnity.

Further on, the hills opened, and gave a view of the whole country beyond, presenting a scene of loveliness very common in our fertile island. A small but beautiful river wound through the valley, carrying life and fertility along its banks. Wide spreading oaks and tall beeches, with the graceful birch and chestnut trees bending their lower branches nearly to the green turf beneath, enclosed the grounds of the Manor House, which, built on a gentle ascent, looked down on the peaceful valley below.

The house, itself, was a fine old building, well suited to the habits of a country gentleman, though not so large as the gardens and plantation surrounding it, might have admitted. These had been gradually acquired by each[6] successive owner of the mansion, who took pleasure in adding to the family estate by purchasing all property immediately adjoining, but had wisely refrained from patching and spoiling the house itself.

Captain Clair was determined to admire every thing; he had got up unusually early, and that in itself was a meritorious action, which put him in perfect good humour with himself. It was a very pleasant morning, too, numbers of insects, he had scarcely ever seen or thought of since he was a boy, attracted his attention, and flew out from the dewy hedges, over which the white lily, or bindweed, hung in careless grace. The butterfly awoke, and sported in the sunshine—and the bee went forth to the busy labors of the day, humming the song of cheerful industry. All combined to bring back long forgotten days of innocent childhood and boyish mirth; the pulse which an Indian clime had weakened, beat quicker, and his spirits revived before the influence of happy memories[7] and the healthy breezes of the Cotswold. Then, as the morning advanced, he lingered to watch the movements of the villagers, and to muse upon the characters of the inmates of the different cottages as he passed them, and to observe that those who dwelt in the neatest were those who stirred the first. The labourers had gone to their work, and now the windows and doors were opened, and children came forth to play.

As he returned again to reach the rectory in time for its early breakfast, he perceived one dwelling much superior in character to those around it, with its antique gable front ornamented with carefully arranged trelliswork, over which creepers twined in flowery luxuriance, and the simple lawn sloping down towards the road, from which a low, sunk fence divided it. Here, careless of observation, a young child had seated herself—her straw hat upon the turf beside her, while she was busily engaged in twining for it a wreath of the wild lily, forgetful that in a few minutes its beauty[8] would perish; she was a lovely child, the outline of her infantine features was almost faultless, and her little face dimpled with smiles as she looked up from her occupation to nod some brief salutation to the poor men as they passed her on their way home.

Arthur Clair could scarcely tell, why, of all the objects he had observed that morning, none should make so deep an impression as the sight of that young child, or why he felt almost sad, as he thought of her twining those fading flowers, and as he strolled on, why, he looked at nothing further, but still found himself musing on the delicate features of that young face.

When he reached the garden gate, he found his uncle strolling about, waiting for him.

Mr. Ware was a fine looking old gentleman, with silver hair curling over a wide and expansive forehead. Though a little under the middle height, there was a gentle dignity in his manner that could scarcely fail to be noticed, or if not noticed, it was sure to be felt. He[9] was neither very witty, nor very learned—yet none knew him very long without liking him. His face, not originally striking, had become more handsome as he had grown older—for the struggle between good and evil, which must be in every well principled mind, a perpetual struggle, had been carried on by him for many years, and so successfully, that each year brought heaven nearer to the good man's thoughts; and now, as the race was so nearly finished, his zeal became more earnest, and his conscience more tender; fearing, lest, after a life spent in his Master's service, he might be found lingering at the last, and lose the prize for which he had been so long striving. In his eye was that look of serenity and peace which seemed to say, "he feared no evil tidings;" for he walked continually under the protection, which only can give that feeling of security which those who have it not would bestow great riches to possess. We have lingered[10] longer than we at first intended in description, but, perhaps not too long.

When we look back to the innocence of childhood, we sigh to think that we can never be children again; we recall that happy time when the world had not written its own characters of sin and falsehood in our hearts; we sigh to think that childhood is gone—but no sigh will recall it. But when we see an old man who has passed the waves of this troublesome world, true to the faith with which he entered life, we feel that here is an example which we may follow. Childhood we have left behind, but old age is before us, and if we live on, must come; and, as the body decays, do we not feel that the spirit should increase in holiness and strength, preparing itself for that beautiful world of light which it must enter or die.

Mr. Ware had resided for many years at Aston; when a younger man, he had been[11] tutor, for a few months, to Colonel Hargrave, the present possessor of the Aston property—and though with his pupil, only during a tour through Italy, the attachment between them was such, that the young man solicited his father to prefer his tutor to Aston, when that living became vacant, partly, he told him, from his wish to secure himself a friend and companion, whenever he visited home. Mr. Ware gratefully accepted an offer which at once placed him in independence; and, as soon as he had settled himself in his new house, he carried one of his favourite projects into execution, by sending for his only sister, who had been obliged to procure her livelihood as a governess; his own small means being, since their father's death, insufficient for both.

It was not then for his own sake entirely that he rejoiced in his improved circumstances. When he drove his neat little carriage to meet his sister, and when he brought her home, and shewed her his house—their house as he called[12] it—with its pretty comfortable sitting-room, looking out upon the garden, and the neat little chamber, where all her old favourite books—recovered from the friend who had taken charge of them during her wanderings—rested upon the neatly arranged shelves, he felt as happy as man can wish to be. And when, with eyes glistening with pleasure, he assured her that it was her home as long as she lived—he said what he never found reason to repent, for the cheerful face of his companion bore perpetual remembrance of his brotherly kindness.

He had once thought of marriage; but the idea had now passed away entirely. In early years, he had been sincerely attached to a school friend of his sister's, whom he had met during one of his Oxford vacations; but she died early, leaving her memory too deeply impressed, to make him wish to replace it by giving his affection to another. His sister, now almost his only near relative, had sympathised,[13] most sincerely, in his loss, and had endeavoured to aid his own manly judgment in regaining that cheerfulness of tone so necessary for the right discharge of the every-day duties of life. She had been rewarded by the more than usual continuation of a brother's early love and esteem, and she had, therefore, no scruple of accepting his offer of protection, and a home.

From that time, she had continued to keep his house with the most cheerful attention to his wishes and whims, and with an evenness of temper which had always been peculiar to her.

There was an air of gaiety about the whole house; the two maid-servants and the old gardener seemed to possess peculiarly good tempers—they were, indeed, scarcely ever disturbed, and we may venture to add, that they were not very much overworked.

There were hives of bees in the garden, chickens in the court-yard, and the gaily-feathered[14] cock strutting about, giving a lazy crow now and then—all seeming to take their ease, and enjoy themselves. In fact, there was a blessing on the good man's home, that was always smiling round it.

It was to this pleasant abode that the young soldier had come down wearied with London amusements, like some strange being who had yet to find a place in its social order.

"You are fortunate, sir," he said, as he strolled down the garden by his uncle's side, "in your neighbourhood. I have seldom seen anything before more comfortably beautiful, if I may use the expression."

"I am glad you like it," replied Mr. Ware, "and I assure you I shall be quite contented if it has the power to make you spend a month or two here agreeably. If you are fond of scenery, there are many places worth seeing, even within a walking distance."

"I suppose the Manor House is amongst the number?" observed his nephew, "I have been[15] admiring it extremely. I cannot think why Hargrave does not come down here. Has he been since he came into the property?"

"Yes—but only once, and then only for a short while; but you speak as if you knew him?"

"A little," replied Clair, "he came home with us from Malta; but friendship, sometimes, ripen fast. He found out my relationship to you, which commenced our acquaintance; I was charmed with him—indeed, I scarcely ever met more variety in any character. Sometimes I could scarcely keep pace with his flow of spirits, and then he would fall into a fit of musing, piquing my curiosity to discover why so great a change should take place, as it were, in an instant—in short, I'd defy any one to get into his confidence. But you know him, sir?"

"Yes," said Mr. Ware, "I knew him very well at one time; his father sent me with him to Italy, and in return, the generous boy obtained[16] me this preferment. But I have not seen him now, I think, for six or seven years—though we write to each other occasionally. You must tell me more about him at your leisure, however, for he is a great favourite with Mary as well as myself; but now, I think, you must be ready for breakfast—Mary is waiting for us, I see. Afterwards, if you are not tired, we will pay a visit to the church—there are two or three monuments of the Hargrave family worth looking at."

"You are very kind," replied Clair, "I am sure I feel better already with the fresh country air—and health after sickness is happiness itself, sometimes."

At this moment, Miss Ware opened the glass door which led into the garden. She was dressed, with studied simplicity, in a black silk gown, with white muslin apron, and her cap, looking as white as snow, fastened round the head by a broad lilac ribbon; but the smile upon her face was the best of all, and was never[17] wanting at the breakfast-table, for she always maintained that no one had a right to be dull after a good night's rest, or to anticipate the troubles of the day before they came.

"Good morning, Edmund," said she to her brother, "and good morning, Arthur," giving her hand to her nephew. "I was just preparing to send your breakfast up-stairs, when I heard you had been out for more than two hours."

"I am not sorry to save you the trouble of nursing me, aunt—I have had enough of that in London," said Clair, gaily, as he followed her to the morning-room, where breakfast waited them. The meal was dispatched with cheerfulness, and he amused his aunt by an account of his walk, and the guesses which it had allowed him to make of the character of their poorer neighbours, with whom she was herself well acquainted.

After breakfast, Mr. Ware invited him to join his morning ramble.

"I shall have an opportunity," he said, as they descended the hill leading to the lower part of the village, "of pointing out to you some of the evils of absenteeism—of which you have, doubtless, heard much. I have always noticed, that what we gain from our own observation is worth much more than the information of others. In this little spot, unhappily, you will see very much to condemn. I have already told you that our landlord, Colonel Hargrave, has not been here for more than six years, and before that visit, which was chiefly occupied in field sports, his sojourn here had been very rare, for his talented mind led him to seek the more extensive knowledge to be gained from foreign travel, even before he entered the army. His father, who has now been dead some years, constantly resided here, till the death of his wife, which made Aston a very different place from what it is at present. Poor Mrs. Hargrave was universally beneficent, and was so much loved and respected by the[19] people in this neighbourhood, rich as well as poor, that her name is scarcely ever mentioned without the title of 'good' being added to it. The time when good Mrs. Hargrave lived is always looked back upon with affectionate regret. When she died, however, her husband, who was passionately fond of her, took a distaste to a place which constantly reminded him of his loss, and he only paid very casual visits to it during the remainder of his life, which did not last long after the domestic blow he had sustained. At present, the estate is in the hands of a rapacious bailiff, who amply fulfils that proverb, which says, 'A poor man that oppresseth the poor is like a sweeping rain which leaveth no food.' Unfortunately, I have no influence with him, and as he has to pay me tithe, he regards me in the light of others who are dependent upon him. It is an unhappy state of things, certainly, for the wages of the poor laborers employed on the estate, are, in some cases, kept back for months[20] together. You may easily fancy how difficult it is for men to live under these circumstances, having no other resource beyond the fruit of their labors."

They had, by this time, reached the hollow between the two hills, where a great many cottages were situated. About them was an appearance of neglect, that is, at all times, disagreeable to contemplate. In most parts, the thatch had become blackened by the weather, and here and there pieces of it had been blown off by the high winds, or were kept in place only by heavy stones laid upon the roof. In some places the walls, which bounded the little gardens, had been suffered to crumble down—loose stones lying in the gaps, but no effort seemed to have been made to replace them. A ditch ran along the road, partially covered with long grass and weeds; but the glimpses here and there afforded of it, told that it was used as a receptacle for the drains of that part of the parish—and a noxious stench arose from it[21] exercising a baneful influence, as might be seen by the pale faces of the children who played about it.

Added to this, there was a desponding tone over the general features of the place, which might have accounted for the wastes of ground which might be seen, here and there, covered with weeds, rather than converted to any useful purpose.

"Surely," said Clair, attracting his uncle's attention, "this self-neglect cannot be attributed to Hargrave?"

"Not altogether," replied Mr. Ware, "this is an evil which I hope time will remedy; there is, indeed, no excuse for it; yet the reason I believe simply to be, that the people, losing their accustomed stimulant, arising from a resident family, and depressed by the low and uncertain wages they receive from an oppressive bailiff, have not yet learned to take care of themselves; but yet I hope, from day to day," said the good man, looking round,[22] "it would not do for me to despond as well as the rest."

Stepping over a small plank that crossed the ditch, they entered one of the cottages. The interior presented a kind of untidy comfort; a large heap of fuel lay in one corner, and a bed was at one side, and seemed used as a substitute for a seat during the day. The windows, where panes had been broken, were filled up with dirty rags; two or three children were playing about with naked feet, and their mother, a remarkably pretty young woman, was working at the darkened window. By the fire was seated a strong hale young man, with his hands upon his knees, contemplating it with gloomy fixedness. A red cap ornamented his head, and partly shaded a pair of dark eyes, and a scowling countenance.

Mr. Ware could not but enter the cottage with the consciousness that he was not particularly welcome; yet this did not render his visits less frequent.

"Well, Martin," said he, "I am sorry to see you at home, for I fear you are out of work."

The man answered, without rising from his seat—

"I am out of work, and so I am likely to remain, I suppose. It is up-hill work to have nothing better to look to than this comes to—and it is very hard to be owed ever so much money, which I have earned by as honest labor as was ever given in exchange for money. I have heard you read—'cursed is he that keepeth a man's wages all night by him until the morning,'—but I don't know what would be said to him that can keep them for months, letting a poor man starve, without thinking of him for a moment. When rent day comes round, then it must be rent, or turn out; we hav'nt got no power in our hands; but I say 'tis a very hard case."

"It is very hard, I allow, Martin," said Mr. Ware, "but the wrong done you does not[24] excuse your sitting here idle; have you been trying for work?"

"Yes, I've been to all the farmers round; but there's none to be got."

"How do you manage to get on then?"

"We live as we can," answered the man, sullenly.

"Well, my good fellow," said Mr. Ware, kindly, "make another effort, and do not sit down here idle all day. I hear that Colonel Hargrave is coming to England shortly, if, indeed, he is not already here."

"We have heard that so often," growled Martin, "that we cannot put any faith in it. He'll never come to do us any good, I reckon."

Mr. Ware offered him a little more advice as to exerting himself, and then, with a small gratuity to his wife, left the cottage with his nephew.

"He is a notorious poacher," said he, as they walked on, "and his excuse is, if they do not give us our own money, we must take an[25] equivalent. It is difficult to preach while poverty and starvation are opposed to the maxims we would wish to inculcate. I wish something could make the Colonel believe the actual state of things; but I do sometimes fear he entirely forgets us. In that neat-looking dwelling," he continued, after a pause, "lives a woman, who has hitherto obtained her livelihood by supplying the poor inhabitants with bread and other necessaries; for some months past, however, Rogers, the bailiff, has found excuses to withhold the wages from most of the workmen engaged in repairing the premises at Aston, and they have been obliged to live upon credit, which this poor woman has been persuaded to give them—in consequence, she tells me, she is nearly ruined; and from the confusion in which her money matters stand, she has fallen quite into a state of melancholy. I went to her yesterday, so that I will not ask you to see her to-day; but we will come in here," he said, at the same time lifting the[26] latch of a door, which opened into a small room, more like some hovel, attached to a tenement which contained several families.

It was a wretched-looking place, and Clair could scarcely suppress a shudder as he entered it. It was but badly lighted from a broken window; an old piece of furniture served, at once, for a table and a sort of cupboard; two chairs, and a stool, completed the furniture, with the exception of a shelf, on which the poverty of the house was displayed, in half a loaf of bread which rested on it. Here an old man sat by the smouldering embers of a wood fire, holding his hands as close to it as possible, as if he hoped to find comfort in the miserable heat it afforded, for his thin hands looked cold, though it was still early in autumn. He welcomed them with pleasure, and offered his two chairs to the gentlemen with ready alacrity, taking possession of the stool for himself.

While Mr. Ware continued talking to the[27] old man, Clair gave a searching glance round the poor dwelling, and trembled to think how the cold December wind would whistle through the old window; but when he thought of asking some questions concerning it, he was checked, by hearing the two old men discourse with such apparent ease and cordiality, as if they had entirely forgotten where they were.

"Is it really possible, sir," said he, when they had left, "that nothing can be done for that poor old man?"

"I fear nothing can be done," returned Mr. Ware, "unless we can persuade Hargrave to return to us."

"But how," enquired Clair, "would his coming remedy the evil."

"It would do so in a great measure," replied Mr. Ware, as they turned homewards. "A man with his wealth could afford to keep all that are now out of labour, well employed. A farmer cannot well afford to pay an old man for the little labour he can give, but a rich[28] landlord can easily find him employment; at a lower rate of wages, of course. Formerly, those who were too old for hard work, were allowed to sweep away the leaves, or clean the weeds from the walks on the estate, which were a few years since beautifully kept. The absence of a rich family in a place where the people have learnt to depend upon them, is a serious loss. You will wonder, perhaps, that I do not instantly, and fully relieve the situation of the old man we visited just now, but the poverty which has prevailed in almost every house during the past year, has been very great; and I have been obliged to divide my charity so as to make it more extensive. Besides, I do not much approve of giving where it can be avoided; and, therefore, husband my means for the scarcity of the coming winter."

"I should have guessed," said his nephew, "that some such motive influenced you, or I know such cases would meet with instant relief—but[29] of one thing, I am certain, Hargrave cannot be aware of this."

"We will hope not," said Mr. Ware, somewhat sadly; "but I have written to him frequently, and if Rogers gave me the proper directions, it is hardly likely my letters have not reached him. It is too probable, that, like many more, he relies too much upon his bailiff."

They had, by this time, reached the rectory, and Clair, exhausted from unusual exercise, threw himself into an arm-chair, and took up a book.

From dream to dream, with her to rove,

Like faery nurse, with hermit child,

Teach her to think, to pray, to love,

Make grief less bitter, joy less wild.

These were thy tasks,—.

Church Poetry.

About a quarter of a mile from the rectory, and close to the Church, was the pretty little residence which had attracted Clair's attention in his morning walk. It was an old fashioned little house, with gable front, and latticed windows, with ivy climbing over the walls, and jasmine and honeysuckle creeping in rich luxuriance over the old porch. In front, the grass-plot sloped down, with a wide gravel walk[31] running round it, to the gate, which shut it in from the high road. At the back lay a spacious vegetable garden, irregularly laid out, and interrupted here and there by a rose-bush, or bed of beautiful carnations, as it suited the old gardener's taste—for he had lived in the family so many years, that no one dared dispute his will in the garden—it was conducted on his most approved style of good gardening; and old John would have defended that style against all the world. To have discharged him from her service would have been one of the last things his mistress would have thought of; therefore, the only alternative was to let him have his own way in every thing. One part of his system was to put every thing in the place best suited to its growth, without much regard to order, and the garden often presented a strange medley in consequence; the hottest corners were shared by early lettuces, and rich double stocks, and radish beds, and so on, throughout the garden; but there was something[32] not unpleasing in the mixture, though it looked a little singular, and the general neatness was not to be found fault with—and the turf walks cutting the garden in many directions, were always smoothly cut and rolled.

The spot where old John was most certain to be found, was just in the middle of the garden, where he had enclosed a small piece of ground by a high and closely clipped yew hedge, to keep out the wind. In this small enclosure, were two or three hot-beds, with cucumbers, melons, or some very early radishes, or cress under glass frames. He had always something to do round these beds, the matting covers were to be put on or taken off, and the glasses opened a little more, and more, as the day advanced, and then, of course, to be closed again, by degrees, towards evening. If any one touched them but himself, he looked as if his whole crop must inevitably be spoilt; but the secret might have been, that, he had always some little surprise to bring out of them, such as[33] a cucumber ten days earlier than could have been expected; or some mustard and cress, before any one else thought of planting any, which, of course, was not to be seen till quite ready for the table.

There was an appearance about the inside of the house, as well as of the garden, as if a great deal of money had been spent upon it formerly, for there were many solid and ornamental comforts in both, which might have been dispensed with if required.

The drawing-room, though small, was substantially and elegantly furnished, though old fashioned; every thing in the room too bore the evidence of refined habits, but nothing told of any present expenditure. Such as it had been ten years before, it very much remained now. The dining-room and usual sitting-room, had much of the same appearance though it did not give quite the same reflective, feeling—ladies' work, and a child's playthings, gave life and animation to it.

Colonel Lesly had lived here for many years since his retirement from the army, having lost a leg during the Peninsular war, where he had served as a brave officer, and only retired from the service when unable to be of further use to it. On his return to England, he, with his wife and child, settled in his native county—and fixed on this cottage for his residence. His wife was most sincerely attached to him, and her society with that of their daughter Mabel, made him scarcely regret, being obliged so soon to retire from a profession so well adapted to his tastes. He had been fond of reading, when a boy, and had not neglected the opportunities presented by his wandering abroad, to cultivate his taste for general information. One of his chief pleasures soon became that of teaching his little Mabel all he knew, and her intelligent questions often led him to take an interest in subjects he might otherwise have neglected.

Since their settling at Aston, Colonel and Mrs.[35] Lesly had had several children, who had all died in infancy, still leaving Mabel as the only object of parental love; fondly did her father guard the young girl's mind, growing in intelligence, and beauty, whilst her speaking features lighted up with smiles whenever he came near. Proudly did he watch her as each year gave her something more soft, more touching, more womanly; and earnestly did he hope that life would be spared him to guide aright a mind of such firmness and power, joined to feelings so warm and eager, that it seemed to him a question which would have the ascendancy, heart or mind. But that wish was not to be granted, and Mabel's first real sorrow, was her father's death. He had gone on a short visit to London, upon some urgent business, and had there taken the typhus fever, which made its appearance soon after his return home, and, acting on an enfeebled constitution, carried him to his grave, after a short illness. A few days after his death, Mabel's youngest sister was born.[36] It was, indeed, to a house of sorrow and mourning, that the little child came, for her mother's constitution never recovered the shock she had sustained in the loss of one, not only most dear, but on whom she had become almost wholly dependent.

It was then that Mabel felt the benefit of her father's lessons so firmly impressed on her mind, and resolved to act as she believed he would have led her to do, could he have been allowed the power of guiding her still. So severely did her mother feel the loss she had sustained, both in health and spirits, that she rather required support herself than felt able to afford it to those dependent on her; Mabel, therefore, soon felt the necessity of exerting herself, as all the family responsibilities seemed left entirely to her care.

As soon then as she could at all recover from the blow occasioned by her father's death, she applied herself to the management of their now reduced income, and busied herself in[37] cutting off all the expenses which the Colonel's liberal habits had rendered almost necessary to his happiness, but which were now quite beyond their means.

In the course of her enquiries, she had no greater opponent than old John; he first insisted that he himself was quite indispensable to the arrangements of the family; and when he had gained that point, he was equally obstinate about the carriage and ponies. But Mabel had the advantage in that particular, at least; the old gardener was left in quiet possession—but the coach-house and stable were shut up—and after many a battle with their old friend, everything else that could be dispensed with, was cut off, till the expenditure was reduced to something within their income. John pined and fretted, but his young mistress had such a winning way, he could not keep his ill-humour long. He had declared, during one of his contests, that she never could be happy without the pretty pony which had carried her[38] up and down the hills so often; but he was obliged to give up the point, when he saw the delight with which she carried her infant sister in her arms and danced her in the sunshine, with half a mother's hope and pride, as if she wanted nothing more to make her perfectly happy.

Sometimes, when the child grew older, she would take her to gather the yellow cress, or the cowslip, and watch her trembling steps with the most careful attention, or lead her to the church-yard, and there, seated on their father's tomb, give her her first lesson in eternal things. And then they would return together to cheer their mother's solitude, and try to divert her from her never ceasing regrets; and thus years passed by, and if sorrow laid again its heavy hand on Mabel's brow, resignation had followed to smooth away its lines, and leave it soft and gentle as before.

On that bright August morning, which we have before described, she was sitting with her[39] little sister, now a beautiful but weak and unhealthy child, of seven or eight, at her lessons in the cheerful little sitting-room. Mabel—with her bright, quick eye, changing color, and speaking countenance over which a thought, perhaps a single shade of mournfulness had been cast, and the little girl by her side looked well together, and they were almost always in company. Amy was at her French lesson, which that morning seemed peculiarly hard to learn, and much as she always tried to please her sister, she could not help turning her wandering eyes rather often to the open window to watch the butterflies flit past in the merry sunshine.

"It is so difficult, Mabel dear," said she, at length, "I learnt it perfectly this morning, but I cannot remember the words now."

"Well, try once more," replied Mabel; "but you must not look out of the window."

"But my head aches so," said Amy, coaxingly,[40] knowing that Mabel could hardly ever resist her plea of illness.

"Well, there is mamma's bell, and while I go to dress her, you can take a run round the garden—but do not be long, or I shall have to call you."

Mabel went up-stairs, and Amy ran off to the garden—her first object was the fruit trees, to see if any were on the ground—she found none—but many beautiful ripe peaches were on one tree, which was carefully trained against the wall, and one finer than the rest, perfectly ready, and peeping out from the leaves, looked peculiarly tempting. She stopped to look, then felt it gently, then tried to see if it were loose, till one unfortunate push, and the peach tumbled to the ground. Amy looked frightened, and gazed round to see if any one was in sight, but seeing no one, she picked it up, and began to eat it.

Suddenly the awful step of old John was heard coming from the cucumber-bed.

"How did you get that peach, miss?" he said, roughly.

The child turned red, but answered quickly,

"I picked it up."

"Well, I would not have lost that peach," said he, "for half-a-dozen others. Miss Mabel told me to save half-a-dozen for Mr. Ware, and this was the best of the lot—I shan't have such another beauty this year. Oh, miss."

"But you said I might have all I picked up," answered Amy, clinging to her subterfuge.

"Yes; but I thought this was too firm to fall, watching it as I did too," said he, as he looked in consternation from the tree to the half eaten peach in Amy's hand.

The child was not long in taking advantage of his silence, and ran into the house just in time to take up the French lesson before Mabel returned.

There was a look of indignation not easily[42] mistaken by Amy on her sister's face, when she entered the room.

"Oh, Amy," she said, in tones of anger and surprise.

Amy looked up, but said nothing—she was frightened, for she knew that she had been doing wrong.

"I did not think," said Mabel, while an expression of contempt curled her beautiful lip, "I did not think you could be so mean as to screen yourself from blame by a falsehood."

Amy was going to speak, but her sister interrupted her.

"I know every word you would say; but it is all, all wrong. I heard every word, and I dare say, guessed every thought. You did not really mean to pick the peach, but you could not resist the temptation to loosen its hold. When it fell, you were surprised and sorry; but you could not resist the temptation to eat, because you were alone, and thought that no[43] one saw you; then, when John came, you turned coward, because you were wrong, and told him you had picked it up—and this was true, though it was also true that you were the means of knocking it down first—so you had neither the courage to speak the truth, nor tell a falsehood."

Mabel spoke quickly and impetuously, and as the whole truth glared on the child's mind, the hot tears fell quickly on her burning cheek.

"You do not love me, Mabel," she said.

"Because I will not let you be mean, deceitful, and wicked. What would papa have said had he seen his child act so?"

"Oh, forgive me, dear Mabel, and do not talk like that," said Amy.

There was a tear in Mabel's eye that softened the severity of her tone, and sitting down by her, she said, more quietly—

"Amy, love, in that little action, I saw[44] enough to make me indignant, and more to make me sorry; for if you do not get rid of that deceit, which has led you wrong now, it will go on, leading you into worse errors, and how can I take care of you if I am not certain you are speaking the truth. Falsehood is the beginning of all sin; and you will learn to deceive me; and when I think my darling is all I wish her, I shall discover something hidden and sinful, that will tell me I am wrong. Oh, I am so vexed."

"Forgive me—oh, do say you forgive me?" cried the punished child.

"Have I the power to forgive what is sinful?" said Mabel, kissing her affectionately.

Amy understood, and running to the chamber where they both slept, she fell upon her knees, and clasped her little hands in prayer.

A child's repentance is not very long, and Amy soon returned, her countenance meek and subdued, and looked timidly at her sister.

"Now then, Amy," said Mabel, "prepare yourself for a difficult duty—come and tell John all you have done."

Amy hesitated and trembled.

"He will be so cross," said she, entreatingly.

"Very likely; but you are not a coward now—you are not afraid to do right. It is difficult, I know, for John will not understand what you feel, and may remember it for a long time; but still you will come."

Amy gave her trembling hand to her sister, and, with a very blank countenance, accompanied her in search of John.

They had to go all over the garden; but found him, at length, standing disconsolate by the peach-tree.

"John," said Amy.

"Yes, miss," replied the old man, gloomily, and half angrily.

"John," she continued, "I touched the peach, and that was why it fell down."

He looked too amazed to answer.

"I am very, very sorry—will you forgive me for telling a falsehood?" murmured Amy, beseechingly.

John looked still very surprised and angry.

"Miss Amy," he began, "I could not have thought you—"

"But forgive her this time," interposed Mabel, "she is very sorry, and it has been a hard struggle to come and tell you how very wrong she has been."

"Bless you, miss," answered the old gardener, quickly, "you are your own father's child, and I know how much you must have suffered when you found any kindred of your'n a telling lies. But I forgive you, Miss Amy, and never you do wrong like that again. Bless you, Miss Mabel, for you be leading the dear young lady in the right path, as well as walking in it yourself."

Love not, love not, the thing you love may change.

What general interest is excited by the arrival of the post. Who ever settled himself in a new place, for the shortest time, without making himself acquainted with its details, the time when it arrives and leaves? And who ever entirely loses this interest, spite of its often more than daily occurrence? There is no sameness in it, because there is no certainty.

Letters only came to Aston twice in a week, and then they were brought by a man—who[48] could hardly be dignified by the title of postman—at some uncertain time in the middle of the day.

On these days the road by which he came was an object of interest to Mabel and her sister, and they often walked in that direction to secure any letters there might be for them, without waiting for their tardy delivery. They were often joined by Mr. Ware on the same errand, and that afternoon they overtook him as he was leisurely mounting the first hill on the road.

"Well, young ladies," said he, greeting them with a smile, "we are all going to meet the postman as usual I suppose?"

"Yes, sir," replied Mabel, "the post always seems to have sufficient interest to make even you choose this road on Tuesdays and Fridays."

"Well, I confess," he replied, "I always have great pleasure in seeing the man turn the[49] corner, besides, as he is so uncertain, one is tempted to take a longer walk, expecting to see him every moment."

"Yes," said Mabel, "we almost always meet him, and yet there is seldom more than the possibility of a letter after all."

"My hopes are not quite so indefinite," said Mr. Ware, "I am always certain of a paper, which is often worth more to me than a letter. I used to think when a person took great interest in the post it was a sign that they were not quite happy at home or in themselves."

"And do you not think so still?" said Mabel.

"Not so much, certainly," he replied, "I think it often arises from the feeling that we are not quite independent of the outer world till the letters of the day have been read. Good and bad news must frequently come by letter, and, therefore, as long as we have any friends separated from us, we must feel a little anxious to know if there be any news at all."

"Do you not think," said Mabel, "that this is sometimes carried too far, and may degenerate into almost a sickly feeling?"

"Yes, certainly; I would not have any one indifferent on common subjects, but too great attention to things of this kind must be wrong."

"I have often thought so," said Mabel, thoughtfully, "when I have felt quite anxious on seeing the man coming, and then when I open my letters, full of the most ordinary business, I feel quite ashamed of myself."

"And what were you really hoping for, dear child?" said Mr. Ware.

The color rose fast over her truthful countenance, but at this moment the postman himself was seen, and saved her the pain of answering.

Mr. Ware soon secured his papers, and one or two letters, and being anxious to convey one home to his nephew, he took leave of them where the road separated.

"Now then," said Mabel, when they had parted from him, "let us see which will get home first, for mamma will be glad to get this letter from aunt Villars."

Amy reached home first, but Mabel quickly followed her to the drawing-room.

"Here, mamma, is a letter from aunt Villars," said Mabel, echoed by Amy.

"From Caroline," said Mrs. Lesly, "I do not think it can be from Caroline, for there is no Bath post-mark, it comes from Cheltenham."

"Do open it mamma, and see if they are at Cheltenham," said Mabel.

"Fetch me my glasses then," returned her mother, "stay—here they are, but you must not hurry me, or my head will begin to ache again, it has been very bad all the morning."

"Oh, yes, mamma, there is plenty of time; come, Amy dear, and take your bonnet off."

Mabel had taken up her work before she again ventured to ask any questions. At length she said—

"Is aunt Villars at Cheltenham, mamma?"

"Yes, my dear, but only for a week or ten days."

"Will she come and see us now she is so near?" she enquired.

"I will read what she says about that, my dear," said Mrs. Lesly, taking up the letter, (some part of the aunt's communications being always mysteriously reserved).

Here it is:—

"I cannot leave Gloucestershire without coming to see you, dear Annie, and your sweet children, and therefore, if you say nothing to the contrary, I will drive over some how on Monday, and remain till Tuesday. If not asking too much of my dear sister, I shall leave Lucy with you; she is not quite well, and a run in the country will do her good, after the heat of Bath. My little girl finds pleasure in anything, and I promise you she shall be very good if you will let her come to you."

"Oh, how nice, mamma," cried Amy.

"Very nice that your aunt is coming, I allow," said Mrs. Lesly, "but I do not know what to say to Lucy, all little girls are not so good as my Amy."

"It would be unkind to refuse her," said Mabel.

"And if she is not well, poor child," added her mother. "I quite forget how old Lucy is, she cannot be so very little after all."

"But," said Amy, "aunt calls her, her little girl, and says she will be very good; if she were grown up like Mabel, of course she would not be naughty."

"I do not know that," said Mrs. Lesly, with a smile, "grown up people are often as naughty as little ones; so either way she was right to promise. Well, we must have the spare room opened, it must be quite damp, I fear, after being shut up so long."

"Oh, no, mamma," said Mabel, "I open[54] the windows every morning, myself, so that I am sure the room is well aired."

"There must be a fire there, however, I suppose," replied her mother, trying to exert herself to think.

"Yes, Betsy shall light a fire there to-day, and I will see that the room is comfortable."

"But stay," said Mrs. Lesly, who was always troubled by anything like arrangements, "who is to sleep in Lucy's room when Caroline is gone. I am afraid we cannot manage it."

"We will see how old she is when she comes," suggested Mabel, "and if she is afraid to sleep by herself Betsy must sleep with her; but from what I remember she cannot be very young."

"Well then, my dear," said her mother, "and so you will promise to contrive to make everything comfortable; now nothing makes me so ill as arranging, and your poor papa never left me anything of that kind to think of. I[55] remember once going down to Weymouth, when you were a baby. I could not tell what I should do there, being obliged to sleep at an hotel, for the first night, for we could not find a lodging, the town was so very full. So when we came there, we could get nothing but a small, uncomfortable room; and some how or other, we could not find any of the baby's things without pulling our boxes all about so, and I was so tired and teased, that I sat down, and—and—

"'Annie,' said he, 'now don't cry—I can bear anything better than your tears—leave everything to me—it will be much the easiest plan.'

"And so I did—and he put my nurse to work so busily, that my baby was asleep before I could think about it; and the next morning he was up early, managed to secure us a lodging, and made us all comfortable. Ah, I am afraid he spoilt me, I do not know how to do anything now, I fear."

"Well, dear mamma," said Mabel, twining her arm round her neck, and kissing her affectionately, "I would not have you miss my dear papa less than you do; but you must not tease yourself about anything. Did I not promise to try and supply his place? I do not mean to let you have any trouble at all. Here is your desk and a new pen—the ink is a little too light, but it writes freely—and now, while you answer my aunt's letter, you will be glad to get rid of us."

"I do not want to drive you away, love," replied her mother; "but you know I can never write if there is the least noise—so, perhaps, you had better go, and take Amy with you. I have not written for such an age, it makes me quite nervous."

"Oh, yes, I know, mamma dear; come, Amy, we will go and look to the spare room. I will seal your letter, mamma, when it is finished."

Mabel was soon busy in thinking over the[57] accommodations necessary for visitors, with Betsy's aid, amidst Amy's incessant questions.

"Do you think, Mabel," she began, "that Lucy is very little?"

"I do not much think she is little at all," replied Mabel.

"But aunt Villars called her, my little girl," persisted Amy.

"Yes, but many mammas talk of grown up children in the same way."

"Do you think," said Amy, after watching her sister for a few minutes in silence, "I had better put some of my books on the shelf for her to read, if she happens to like them?"

"If you have any that will look pretty, you may put them there certainly."

"Do you think she will like the swing at Mr. Ware's?"

"If she is like you, perhaps she may; but whether she be little or not, we must both try and make her pass her time pleasantly, you[58] know," said Mabel, as she glanced round the room with approval.

The chintz curtains had been re-hung—the snow-white coverlet had been placed upon the bed—and the dressing-table arranged with the most careful attention to comfort and convenience. Everything, in the careful arrangement which Mabel had bestowed upon the room, seemed to speak a welcome; and through the open window the fresh breezes of the Cotswold hills passed freely.

"Does it not look comfortable?" said Mabel, appealing to her talkative companion.

"Yes, Mabel, dear, everything looks nice that you manage; but," added she, returning to the former subject, "if she is a great girl, what can I do to amuse her?"

"Oh, many things," returned Mabel; "even you can do, I think, if you try; you must not talk to her very much, and ask her too many questions."

"Do I tease you, Mabel, dear, when I ask you questions?"

"Not often; but then you know I love you," said her sister, "and therefore do not get teased."

"But why do you think she will not love me?"

"I think it very likely she will love you," said Mabel, looking down upon her affectionately, "if you are good; but not till she knows you, not very much, at least. You know, we must buy people's love."

"Do you mean by making them presents?" said Amy, looking a little shocked at the idea.

"Not what you mean by presents certainly," said Mabel, smiling.

"What then?"

"Well then, first, you must give them your love, before you consider what they think of you."

"Is that a certain way of buying love?"

"It will be nearly certain," said Mabel, "to[60] get you good will, at least, from every one, whose esteem is really valuable, for when we love, we try to do everything that is kind; we are not easily offended by little things that might annoy us, if we did not love; and then the wish to avoid giving offence, will lead us to govern our feelings, so that we may not be sullen, or out of temper, which would make us disoblige them by saying anything to wound their feelings."

"Would it do anything else?" said Amy, who always liked to hear her sister talk.

"Yes, I think it would lead us to speak the truth, for fear of encouraging them in any bad thing; for if we must not do wrong, we must not let it be done by others, if we can help it, particularly by those we love."

"But then," said Amy, "if a person is bad, do not you think it would be better to wait and see? We ought not to like a bad person, you said, one day."

"Not exactly that; I told you not to be[61] intimate with Mary Watson, because she did many things I did not like, and knew a good many little girls, who could not teach her any good; but still, I think, if, for some reason, we were obliged to have Mary Watson here, you might love her just as much as I told you to love Lucy, for if you spoke the truth, she could not think you liked any of her naughty ways."

"Then why may I not know her now—could I not speak the truth?"

"Perhaps you might," said Mabel; "but I think, sometimes, that not to avoid temptation, is taking one step to evil; so I thought it best to avoid Mary Watson, as I could scarcely hope you would do her very much good, and she might do you harm."

"You always think of me, Mabel," said Amy; "when do you find time to think of yourself?"

"When I go to bed," she replied, "and then I ask myself if I have been as kind to my little orphan sister as I ought to be?"

"But, Mabel, dear, when you sit alone, sometimes, and look so very sad, and I come in, and see tears on your face, is that about me?"

"No; but it is not often so."

"Not often; but I am so vexed when it is. Why is it, Mabel dear?"

"Because," she said, her eyes filling with tears as she spoke, "somebody loved me once, who does not love me now."

"No, I am sure that is not true—every one loves you; mamma, Mr. Ware, Miss Ware, Betsy, John, every one." "I am sure that can't be true, and it is naughty to fancy unkind things; Mabel, dear, dear, Mabel," said the child, jumping on a stool and throwing her arms lightly round her neck, "and you are never naughty."

"Oh, yes I am, many many times a-day," said Mabel, hiding her face on Amy's shoulder, "my good, good, child, what should I do without you."

"Oh, nothing without me, you could not get on at all without me."

"Not very well, I think, certainly," said Mabel, smiling through her tears at Amy's satisfaction, "but we have been a long time away, and mamma must have finished her letter—come and let us seal it before the man calls again, for if it is not ready, what will become of our visitors."

"But, Amy," said she, sinking her voice almost to a whisper, "never tell mamma or any one that I ever cry, or why I cry."

"Oh, never, you know I can keep a secret."

"You promise," said Mabel.

"Yes, I promise faithfully."

This is a likeness may they all declare,

And I have seen him, but I know not where.

Crabbe.

Mrs. Lesly had been, as a girl, both beautiful and accomplished, gifted with good natural talents, though possessing little perseverance and much indolence of character. Upon her marriage every faculty of her mind became absorbed in devotion to her husband, and an almost indolent dependence on his will. Since his death she had continued so very depressed that, at the time when both Mabel and Amy might have much needed a mother's care, she felt[65] every exertion too great for her weakened nerves and failing health.

She had, by her marriage, entered a family a little above her own, and now suffered the too general consequence, in the neglect of her husband's relations. She felt all things deeply, and this, if possible, aggravated her loss. The Lesly and Hargrave families were closely connected, but the absence of the Colonel, whose family mansion lay so near them, prevented her receiving that attention which the neighbourhood of a rich relation might have procured her. The secluded life to which she now clung so earnestly, only increased the extreme sensitiveness of her feelings. Her mind therefore, suffered to prey upon itself, became a curse instead of a blessing, as it might have been, had it been employed in any useful purpose; and the delicacy and refinement of her nature, now only quickened her perception of the slightest coldness, or unkindness in those around her; spreading about her a kind of atmosphere[66] of refined suffering, which duller eyes would never have discovered.

Yet the indulgence which she claimed from others always rendered her an object of affection, and her devotion to the memory of her husband veiled many failings, and excused her indolence sometimes even in the eyes of the most ascetic. Joined to this weakness of character, however, she possessed many fine qualities. She was generous in the extreme, and liberal to a total forgetfulness of self, and would forgive, where no injury was intended, with a magnanimity, which, applied to a real offence, would have been noble. She was also very patient under the oppression of continual ill health, and though too indolent to exert herself, she was capable of suffering without complaint.

Mabel inherited her mother's intellect and delicacy of feeling, but seconded by a strong will and great common sense. She possessed also beauty equal, if not superior, to hers, though in her face it always seemed secondary to the[67] feelings which were spoken by it. But there was one peculiar charm in her character, which secured the love of those around her as powerfully as an Eastern talisman. It was a reliance on the good will of others, drawn perhaps from the reflection of her own heart—a kind of security in the feeling that there is always good to those who rightly seek it; a trust in the virtue of others which often proves a touchstone to wake its hidden springs, whilst all feel ashamed of disappointing a hope, founded more on the truest feelings of charity, than on weakness or pusillanimity.

Unlike her mother, she scarcely ever suffered from illness, and gratefully used the blessing of strong nerves and untiring strength in aiding the weakness or bearing with the irritability of others.

Happy the child who possessed such a guide and playfellow, to listen to all the questions and trifles so wearisome to the sick or weak.

Mabel's patience was often called in requisition[68] during the few days which passed before the arrival of the aunt and niece from Cheltenham. At least half a dozen questions would be asked almost in the same form, to which she had to give answers.

At length however, the long expected hour arrived, and Amy had seated herself on the lawn to catch the first sight of that corner of the road which was the furthest point visible, and Mabel was frequently sent to the gate to watch for the carriage, by Mrs. Lesly, who was enduring all the discomfort and nervousness of being quite ready to receive them a long while before it was at all probable they would arrive.

Captain Clair, too, who had, as Mr. Ware's nephew, established a kind of intimacy at the cottage, was leaning over the gate, refusing to come in, lest he should disturb the family meeting, yet seeming well inclined to chat away the time with either of the sisters.

"I am sure you are spoiling your sister, Miss[69] Lesly," said he, after hearing the patient answer to the sixth repetition of 'do you think they are coming;' and Amy had ran in to her mamma to report.

"That is a very grave accusation, but I do not think you quite believe it," said Mabel; "indulge, but not spoil."

"Well, indeed," said he, "it would be difficult to find fault with such persevering self-denial, so we will say, indulgence."

"It requires little self-denial," said Mabel; "to be kind to a very young, and very dear sister. No, self-denial will not do, I will not take the praise of a martyr for doing what I love best. Are you certain," she added, "you do not feel the sun too much, where you are standing, had you not better come in and speak to mamma?"

"Not on any account, thank you," he replied, smiling; "I intend to vanish when the carriage comes up, and present only the very[70] interesting appearance of a departing friend, in order to give a little life to such a landscape."

Mabel laughed.

"Here they are, then, now you may look picturesque."

"Not quite yet, wait a bit, I must be a little more prominent first, or they would never see me. Now is the very moment," raising his hat to Mabel, and with these concluding words, he walked slowly away.

Mabel was seized with momentary shyness, and retreated unobserved, to seek Mrs. Lesly, whose head began to ache, from waiting so long—but, as the party took a long time in alighting, and collecting from the vehicle a multiplicity of boxes, she felt ashamed of being afraid of strangers, and ran down again to meet them.

"Oh, my charming niece," exclaimed her aunt, with apparent cordiality, and kissing her warmly; "how do you do, my sweet girl, let me make you acquainted with my Lucy."

Lucy, who, to Amy's disappointed eye, did not look at all little, took Mabel's hand with earnestness, and putting one arm round her neck, kissed her with extreme warmth, exclaiming:—

"We shall be dear friends, I know."

"I hope so," said Mabel, startled alike at her relation's warmth, and her own composure, which appeared something like coldness.

Mrs. Lesly was met by her sister with the same enthusiasm which quite overcame her weak nerves, and she burst into tears; she could not tell why, she thought it might be joy, or that her head was overpowered by the sweet scent on their pocket-handkerchiefs, or the rapidity of her sister's conversation, and expressions of endearment. Mabel looked on in dismay, a scene had been produced which she was puzzled to remove.

"Dear mamma, do not cry," said she, then turning to Mrs. Villars who was overwhelming her with caresses, she added, hastily; "mamma[72] is not quite well to-day, but she will be better presently, if she is quiet a little while. Will you come and take your bonnet off, aunt, for you must be tired after your drive."

"No, my dear, but I think I will venture to leave her a moment while I run down and see if our boxes are all right; an immense deal of luggage, but then, I am going home, you know. I brought my maid too, though I forgot to mention her in my note." Mrs. Lesly looked alarmed. "I really do not know if she has looked to every thing, but I will go and see, I always like to see things right myself," and with an important air, she hurried down stairs.

Mrs. Villars was of imposing appearance, though too bustling in her manners to be altogether dignified, with colour a little too brilliant, and hair a little too stiffly curled, to be quite natural. Yet, whatever was artificial, was very well added to a good figure, and fine face.

Poor Amy was quite awed into a bewildered silence. Mrs. Villars presently bustled back again, telling Mabel she was now quite ready to go to her room.

"This way, then," said Mabel, shewing them to the chamber she had so carefully prepared; "this is your room, and I hope you will find every thing comfortable."

"Oh, I dare say," she said, looking round, as if approving a child's doll's-house; "everything so very neat and nice, and where is Lucy to sleep."

"This is the only spare room we have furnished and fit for sleeping in now; the rest are shut up," said Mabel, a little timidly, "and we thought you would not mind sleeping together for one night, as you say you cannot stay longer, aunt."

"Oh, yes, we will contrive—but what is to be done with our maid."

"I must manage for her presently," said[74] Mabel; "Betsy has been told to make her comfortable for the present."

"What time do you dine, dear," said Mrs. Villars; "the air of these hills makes one hungry. I really could dine unfashionably early to-day."

"I fancied so, and therefore ordered dinner to be ready half an hour after your expected arrival," said Mabel; who tried to keep them in conversation till Mrs. Lesly should have time to recover herself; and this delay so far succeeded, that on their return to the drawing-room, they found her quite composed.

Dinner being soon after announced, Mrs. Villars gave her arm to her sister, in the tenderest manner possible, saying.

"Well, dear, I hoped to find you quite strong, I must not have any more of these naughty hysterics, or I shall think you are not glad to see me."

"Indeed—indeed, Caroline, you mistake my feelings."

"Well, then, smile away, and I shall read them right. What do you think of my Lucy?" she added, in a whisper; "I wish I could shew you all my girls—for admiring beauty, and accomplishments, as you always did—I do not know what you would say, if you saw them all together. Now, in my opinion, Mabel is perfect."

The last speech reached Mabel's ear, and, perhaps, was intended to do so—but quick as she was in the ready perception of virtue, she had never feebly blinded herself to the faults of others. These few words made her feel uncomfortable—for she was immediately aware that there was a want of sincerity in her aunt's manner, which, betraying some latent reason for dissimulation, always produces a feeling of dislike, or fear.

To Mrs. Villars Mabel soon became an object of fear—she could not tell why, but she had scarcely been a few minutes in her company without perceiving that superiority which the[76] weak-minded find it difficult cheerfully to recognise. Superiority in what, she did not stop to analyse—but even while most lavish of her endearments, she was secretly almost uncomfortable in her presence.

Mrs. Villars had given herself a worldly education, which, though it had moulded even her virtues and foibles according to its own fashion, had never yet been able, entirely, to eradicate the sense of right which had been inculcated in earlier years; yet she only preserved it as a continual punishment for every act of dissimulation and wrong, without ever allowing it to regain entire ascendency over her; though it was a conscience to which she felt bound perpetually to excuse herself. So false, indeed, had she turned to herself, that Mabel's open, honest, truth-telling eyes seemed something like a reproach.

Love for her children—one of the greatest virtues of a woman's heart—had become one of her greatest failings. Her natural disposition[77] rendered her love strong and untiring; but worldliness had warped its usefulness, rendering that love, in its foolish extreme, only a means of making herself miserable, without really serving them. She learned to spoil, but had no resolution to reprove; and they had grown up in accordance with such training.

As children they had been coaxed and bribed to appear sweet-tempered and obliging in company—the plan succeeded; but only left them more ill-tempered and unmanageable when the restraint was removed. This system was, however, too readily followed; and as they grew older, their foolish parent saw no other efficient plan for securing their position in society, than that of continuing the same course of indulgence. She now tried, by the most unbounded gratification of their wishes, to secure to herself that love which timely discipline might easily have preserved in tempers not naturally degenerate. But veiling this weakness,[78] she prided herself on the greatness of her parental love, and threatened to weary every one else by the excess to which she carried it.

Glad of an opportunity of touching on her favorite topic, she said to her sister—

"You must come and see us all some day. Mr. Villars would be so glad to see you, and I should have an opportunity of shewing you my pet girls."

"I never stir out now," returned Mrs. Lesly, shaking her head mournfully, "scarcely even beyond my own door. But Lucy will, I dare say, give us a specimen of all your sayings and doings in time. I should much like to see the children; but fear there is but little inducement to ask any of them to a place where there is so very little going on. My Mabel is very fond of the country, or I should often have been vexed at our seeing so little company."

"Oh, you are quite mistaken, my dear," said[79] Mrs. Villars, quickly. "Caroline and Selina are very fond of the country, and so are you, Lucy."

"Yes, I like it very well in the summer," said Lucy, languidly.

"Do you like the snow?" asked Amy, speaking for the first time.

"No, not much; but we had better not talk of snow in August—it is too near to be pleasant," said Lucy, a little impatiently.

"You forget the balls, my dear," said her mama, soothingly, and watchful of her children's tempers as a lover of his mistress.

"No, mama, I was speaking of snow in the country, and there, I suppose, there is not much dancing. Are you fond of balls, Mabel? but I forgot, I need not ask, for, of course, you are."

"I have never been to a public ball," replied Mabel, "but I have often enjoyed a dance at a friend's house."

"Have you really never been to a ball," exclaimed Lucy, opening her pretty blue eyes wide, with half real and half affected astonishment. "You would be enchanted with Bath. We have such delightful balls once a week. The Thursday balls they are called, and then every season—"

"Lucy, love, you will tire your aunt with your prattle," said her mama, "now confess, Annie, does she not make your head ache?"

"A little," replied her sister, "but do not let my weakness interfere with her enjoyment. She will have little else to listen to besides her own voice," Mrs. Lesly added, trying to smile away her sister's chagrin at finding it really possible that she could be tired at hearing Lucy talk.

There was a momentary pause, when Mrs. Lesly, anxious to conciliate by returning to the subject she perceived gave most interest, enquired—

"Is Lucy your eldest?"

"Oh, dear no! Caroline is the eldest, Selina second, and Lucy the youngest."

"But I think you have one more, have you not?" said Mrs. Lesly.

"How can you forget how many children your own sister has?" said Mrs. Villars.

"My memory is getting feeble, and you must excuse me," replied Mrs. Lesly anxiously, "my forgetfulness arises from no want of affection; but I have not seen you for a year or two now."

"I had forgotten," returned Mrs. Villars, "how time flies. I really must write oftener to you, and keep up your knowledge of us. Well, there is my Maria—but, poor child, I am in despair with her—so unfortunate."

"Not ill, I hope?" enquired Mrs. Lesly.

"No, no—that could be cured—a doctor might cure that; but this, nothing can cure. She is ugly—positively ugly—by the side of her sisters at least; and more than that, she is[82] ungraceful. I have tried the best academy in the town, but nothing will do her any good—such a contrast to the rest, she never will settle I fear."

Mabel glanced at Amy, who was drinking in her aunt's words with the eager curiosity natural to a child, and fearing the effects of this worldly conversation upon her young sister, she persuaded Lucy to come with them into the garden.

Lucy put her arm in Mabel's, whilst Amy watched the movement jealously.

"Here is a lovely peep at the hills," said Mabel, leading their guest to one of the prettiest parts of the garden, where a stone seat was placed near a break in the trees, commanding a view of the country beyond.

Here they seated themselves, looking for a short while, in silence, on the landscape, which the setting sun rendered still more lovely. Had Mabel expected any fine remark to follow this momentary pause in the conversation, she[83] would have been disappointed, for Lucy's next enquiry was whether there were many nice people in the neighbourhood.

"Yes," said Mabel. "Mr. and Miss Ware are very nice people."

"Who are they?" asked Lucy.

"Our rector and his sister."

"Is he unmarried?" enquired Lucy, with increasing interest.

"Yes," replied Mabel, smiling, "but not very young."

"But still marriageable, I suppose?"

"Barely," said Mabel, "at least, I do not think he would consider himself so now. Why, he must be nearly seventy."

"Then who was that fine young man that was walking down the road just now, with light whiskers, and a military air. I did not expect to see such a handsome, distingué looking young man down in the country here."

"That is Mr. Ware's nephew," said Mabel.

"Oh! then he does live here—what is his name?"

"Captain Clair; he is only here for a short time, for his health," replied Mabel; "but how could you tell he had light whiskers?"

"Because he passed while we were at dinner, so that I had a good look at him," said Lucy, half blushing.

"Amy," said Mabel, "there is Captain Clair beckoning for you to run to him, and I dare say he will get you the blackberries he promised you."

Amy ran away to the garden-gate, where Captain Clair was waiting for her, and hand in hand they were soon down the blackberry lane that led to the fields.

"What a very fine young man," exclaimed Lucy, as she watched them out of sight; "do you see him often—I suppose he is a beau of yours?"

"No, oh, no," said Mabel; "a sort of friend[85] he has made himself—but certainly not a beau."

"Ah, you say so."

"And I mean so," said Mabel.

"You mean then, that he is free for conquest," laughed Lucy, coquettishly.

"As far as I am concerned, he is as free as air," said Mabel; "but I would not have you attempt such a conquest, I should think he was too easily won to be kept long in subjection."

"Ah, I know what you mean," said Lucy; "a sort of man that falls in love with every tolerable girl he meets—the very thing for a country visit."

"Well, I suppose neither party would be in much danger if those are your real sentiments," said Mabel. "Captain Clair is too discerning to be entangled by a mock feeling, and you are wise enough to think of nothing more."

"Exactly so," replied Lucy; "but oh,[86] whose pretty house is that amongst the trees?"

"Colonel Hargrave's," said Mabel.

"Colonel Hargrave!" cried Lucy, "cousin Henry, as we call him now. Do you know, Mabel, he is just come back to England, and mamma wrote to ask him to come and see us in Bath. I am so longing to meet him; and we have made up in our minds, already, a match between him and Caroline—that you know would do very well, for she is just thirty, and he must be a few years older, must he not?"

"Yes, I think so," said Mabel.

"And that would be a very nice difference, you know. I am quite longing for him to come. I have talked the match over with Selina so often, that I cannot help looking upon it as quite certain; and then we should have such a nice house to come and stay at; and you would be so delightfully near—would it not be pleasant?"

"You will find it cold without your bonnet," said Mabel, evasively, "shall we go in and fetch it."

"No, thank you," said Lucy; "but I see you are not fond of match-making."

"No, I confess I am not," said Mabel; "but I suppose you hear a great deal of it in Bath, where so many matches must be talked over."

"Oh! an immense deal—it is quite amusing to hear of so many projected marriages, and of their coming to nothing after all."

"But that is why I think match-making anything but amusing," said Mabel.

"But then all the éclat of a conquest would be gone," suggested Lucy, "if there were no talking beforehand. I assure you, last year, there were I do not know how many half offers in our family. Selina and I used to walk round the Crescent and count them all up, and they helped us through the dull weather amazingly; something like the nibbling[88] of a trout, which just serves to keep up the hope of ultimately catching one. Mamma talks a great deal about Caroline's beauty, and her charming spirits—but she does not know how to sleep for wishing her married. It would be horrible to have her an old maid—so I hope and trust the good Colonel, with, I dare say, Indian guineas, and an Indian face, will take pity on her, and bring her here."

"Give me a description of Caroline," said Mabel, suddenly. "Is she not very beautiful and accomplished?"

"How you startle me," said Lucy. "Why she is very tall—fine features, people say—she has black hair and black eyes, and dances splendidly—polks to admiration—so very good-natured—and witty before company—and rather the reverse behind the scenes—in short, would do much better for Mrs. Hargrave than for the eldest of four maiden sisters—and so, in all due affection, I should be very glad to see her married."

"Is she clever as well as beautiful?" said Mabel.

"She sings and plays beautifully. Yes, I believe she is clever—knows French well."

Mabel sighed.