This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Picturesque Pala

The Story of the Mission Chapel of San Antonio de Padua Connected with Mission San Luis Rey

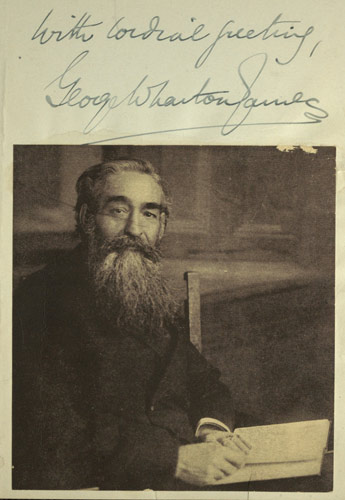

Author: George Wharton James

Release Date: December 5, 2012 [eBook #41561]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PICTURESQUE PALA***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://archive.org/details/picturesquepala00jamerich |

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

Rev. G. D. Doyle

The Story of the

Mission Chapel

of

San Antonio de Padua

Connected with

Mission San Luis Rey

Fully Illustrated

By

GEORGE WHARTON JAMES

Author of

In and Out of the Old Missions of California; The Franciscan

Missions of California; Indian Basketry; Indian

Blankets and Their Makers; The

Indian's Secret of Health;

Etc., Etc.

1916

THE RADIANT LIFE PRESS

Pasadena, California

| Page | ||

| Foreword | 5 | |

| I. | San Luis Rey Mission and Its Founder | 7 |

| II. | The Founding of Pala | 14 |

| III. | Who Were the Ancestors of the Palas | 18 |

| IV. | The Pala Campanile | 23 |

| V. | The Decline of San Luis Rey and Pala | 31 |

| VI. | The Author of Ramona at Pala | 34 |

| VII. | Further Desolation | 37 |

| VIII. | The Restoration of the Pala Chapel | 41 |

| IX. | The Palatingua Exiles | 44 |

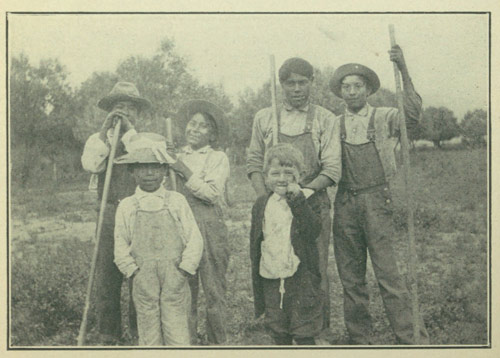

| X. | The Old and New Acqueducts | 55 |

| XI. | The Palas As Farmers | 60 |

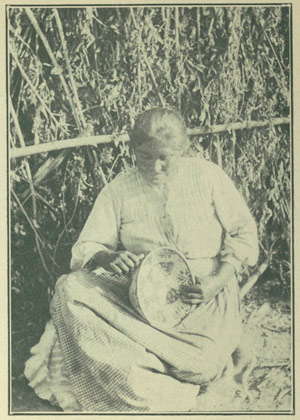

| XII. | With the Pala Basket Makers | 63 |

| XIII. | Lace and Pottery Makers | 68 |

| XIV. | The Religious and Social Life of the Palas | 72 |

| XV. | The Collapse and Rebuilding of The Campanile | 81 |

Copyright, 1916

by

EDITH E. FARNSWORTH

There were twenty-one Missions established by the Franciscan Fathers in California, during the Spanish rule. In connection with these Missions, certain Asistencias, or chapels, were also founded.

The difference between a mission and a chapel is oftentimes not understood, even by writers well informed upon other subjects. A Mission was what might be termed the parent church, while the Chapel was an auxiliary or branch establishment.

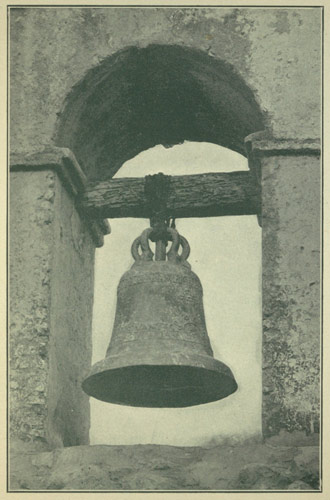

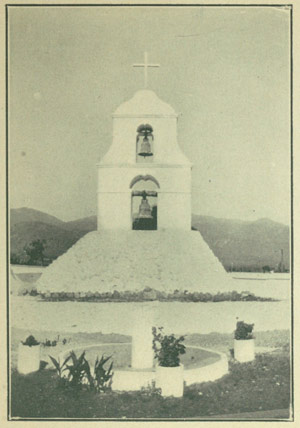

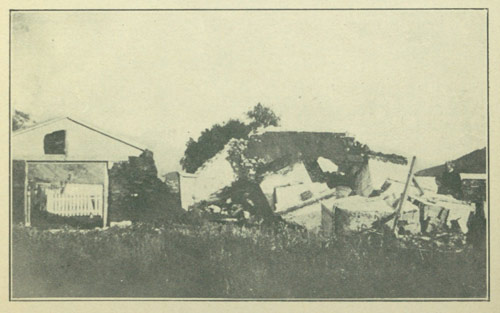

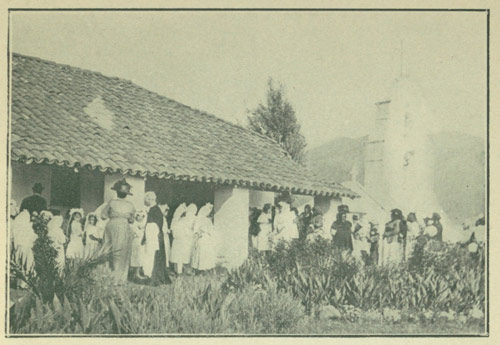

The little mission chapel, or asistencia, of San Antonio de Padua de Pala, has been an increasing object of interest ever since the Palatingua, or Warner's Ranch, Indians, came and settled here, when they were removed from their time-immemorial home, by order of the Supreme Court of California, affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States. A century ago the beautiful and picturesque Pala Valley was inhabited by Indians. To give them the privileges of the Catholic Church and of the arts and crafts of civilization, the padres of San Luis Rey Mission, twenty miles to the west, established this asistencia, and caused the little chapel to be built. The quaint and individualistic bell-tower always was an object of interest to Californians and tourists alike, and thousands visited it. But additional interest was aroused and keenly directed towards Pala, when it was known that the severe storm of January, 1916, which caused considerable damage throughout the whole state—had undermined the Pala Campanile and it had 6 tumbled over, breaking into fragments, but, fortunately, doing no injury to the bells.

With characteristic energy and determination Father George D. Doyle, the pastor, set to work to clear away the ruins, secure the bells from possible injury, and interest the friends of the Chapel to secure funds enough for its re-erection. Citizens of Los Angeles, Pasadena, San Diego, etc., readily and cheerfully responded. The tower was rebuilt, in exactly the same location, and as absolutely a replica of the original as was possible, except that the base was made of reinforced and solid concrete, covered with adobe, and the well-remembered cobble-stones of the original tower-base, with the original building materials, bells, timbers, and rawhide. Even the cactus was replaced. So perfectly was this rebuilding done that I question whether Padre Peyri, its original builder, would realize that it was not his own tower.

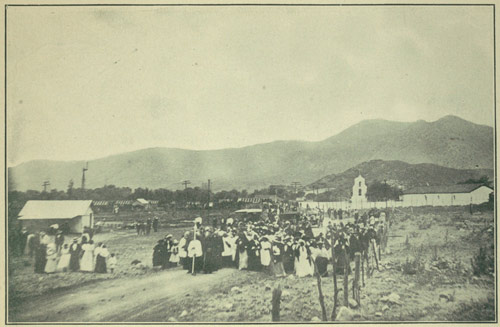

Sunday, June 4, 1916, was selected for the dedication ceremony of the new Campanile, and to give friends of the mission chapel a reasonably full and accurate account of its appearance and history this brochure has been prepared, with the full approbation and assistance of Father Doyle, to whom my sincere thanks are hereby earnestly tendered for his cordial co-operation.

George Wharton James.

Pasadena, California,

May, 1916.

Padre Antonio Peyri, Founder of San Luis Rey and Pala

Picturesque Pala

What a wonderful movement was that wave of religious zeal, of proselyting fervor, that accompanied the great colonizing efforts of Spain in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Conquistadores and friars—one as earnest as the other—swept over the New World. Cortés was no more bent upon his conquests than Ugarte, Kino and Escalante were upon theirs; Coronado had his counterpart in Marcos de Nizza, and Cabrillo in Junipero Serra. The one class sought material conquest, the other spiritual; the one, to amass countries for their sovereign, fame and power for themselves, wealth for their followers; the other, to amass souls, to gain virtue in the sight of God, to build churches and crowd them with aborigines they had "caught in the gospel net." Both were full of indomitable energy and unquenchable zeal, and few epochs in history stand out more wonderfully than this for their great achievements in their respective domains.

Mexico and practically the whole of North and South America were brought under Spanish rule, 8 and the various Catholic orders—Jesuits, Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites—dotted the countries over with churches, monasteries and convents that are today the marvel and joy of the architect, antiquarian and historian.

Alta California felt the power of these movements in three distinct waves. The two first were somewhat feeble,—the discovery by Cabrillo, and rediscovery sixty years later by Vizcaino,—the third powerful and convincing. During this epoch was started and carried on the colonization of California by the bringing in of families from Mexico, and its Christianization by the baptizing of the aborigines of the new land into the Church, the making of them real or nominal Christians, and the teaching of them the arts and crafts of civilization.

Twenty-one missions were established, reaching from San Diego on the south, to Sonoma on the north, and great mission churches and establishments rose up in the land, of which the padres, in the main, were the architects and the Indians the builders.

Second in this chain—the next mission establishment north of the parent mission of San Diego—was San Luis Rey, dedicated to St. Louis IX, the king of France, who reigned from 1226 to 1270, renowned for his piety at home and abroad, and who was especially active in the Crusades. He was canonized by Pope Boniface VIII, in 1297, in the reign of his grandson, Phillip the Fair, and his day is observed on the 25th of August.

The Mission of San Luis Rey was the eighteenth to be founded and Junipero Serra, the venerable leader of the zealous band of Franciscans, had 9 passed to his reward fourteen years before, his mantle descending in turn to Francisco Palou, and then to Fermin Francisco de Lasuen, under whose regime as Padre Presidente it was established. The friar put in charge of the work was one of the most energetic, capable, competent and lovable geniuses the remarkable system of the Franciscan Order ever produced in California. He was zealous but practical, dominating but kindly, a wonderful organizer yet great in attending to detail, gifted with tremendous energy, a master as an architect, and withal so lovable in his nature as to win all with whom he came in contact, Indians as well as Spaniards and Mexicans. The Mission was founded on the 13th of June, 1798, and yet so willingly did the Indians work for him, that on the 18th of July six thousand adobes were already made for the new church. It was completed in 1802. For over a century it has stood, the wonder, amazement and delight of all who have seen it.

Alfred Robinson, the Boston merchant, who came to California in 1828 and settled here, engaging in business for many years, visited San Luis Rey in 1829, and has left us a graphic picture of the buildings of San Luis Rey and the life of its Indians. Riding over the barren and hilly back country from San Diego he discants upon the weariness of the forty-mile journey until the Mission is perceived from the top of an eminence in the center of a rich and cultivated valley. He continues:

It was yet early in the afternoon when we rode up to the establishment, at the entrance of which many Indians had congregated to behold us, and as we dismounted, some stood ready to take off our spurs, whilst others unsaddled the 10 horses. The Reverend Father was at prayers, and some time elapsed ere he came, giving us a most cordial reception. Chocolate and refreshments were at once ordered for us, and rooms where we might arrange our dress, which had become somewhat soiled by the dust.

This Mission was founded in the year 1798, by its present minister, Father Antonio Peyri, who had been for many years a reformer and director among the Indians. At this time (1829) its population was about three thousand Indians, who were all employed in various occupations. Some were engaged in agriculture, while others attended to the management of over sixty thousand head of cattle. Many were carpenters, masons, coopers, saddlers, shoemakers, weavers, etc., while the females were employed in spinning and preparing wool for their looms, which produced a sufficiency of blankets for their yearly consumption. Thus every one had his particular vocation, and each department its official superintendent, or alcalde; these were subject to the supervision of one or more Spanish mayordomos, who were appointed by the missionary father, and consequently under his immediate direction.

The building occupies a large square, of at least eighty or ninety yards each side; forming an extensive area, in the center of which a fountain constantly supplies the establishment with pure water.

The front is protected by a long corridor, supported by thirty-two arches, ornamented with latticed railings, which, together with the fine appearance of the church on the right, presents an attractive view to the traveller; the interior is divided into apartments for the missionary and mayordomos, store-rooms, workshops, hospitals, rooms for unmarried males and females, while near at hand is a range of buildings tenanted by the families of the superintendents. There is also a guard-house, where were stationed some ten or a dozen soldiers, and in the rear spacious granaries stored with an abundance of wheat, corn, beans, peas, etc., also large enclosures for wagons, carts, and the implements of agriculture. In the interior of the square might be seen the various trades at work, presenting a scene not dissimilar to some of the working departments of our state prisons. Adjoining are two large gardens, which supply the table with fruit and vegetables, and two or three large "ranchos" or farms are 11 situated from five to eight leagues distant, where the Indians are employed in cultivating and domesticating cattle.

The church is a large, stone edifice, whose exterior is not without some considerable ornament and tasteful finish; but the interior is richer, and the walls are adorned with a variety of pictures of saints and Scripture subjects, glaringly colored, and attractive to the eye. Around the altar are many images of the saints, and the tall and massive candelebra, lighted during mass, throw an imposing light upon the whole.

Mass is offered daily, and the greater portion of the Indians attend; but it is not unusual to see numbers of them driven along by alcaldes, and under the whip's lash forced to the very doors of the sanctuary. The men are placed generally upon the left, and the females occupy the right of the church, so that a passage way or aisle is formed between them from the principal entrance to the altar, where zealous officials are stationed to enforce silence and attention. At evening again, "El Rosario" is prayed, and a second time all assemble to participate in supplication to the Virgin.

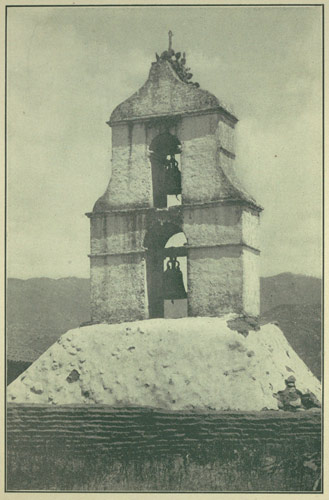

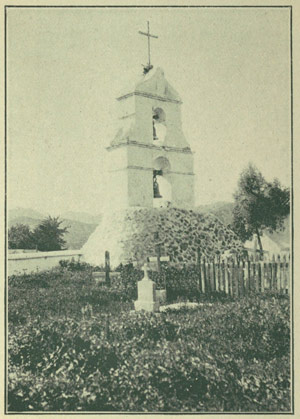

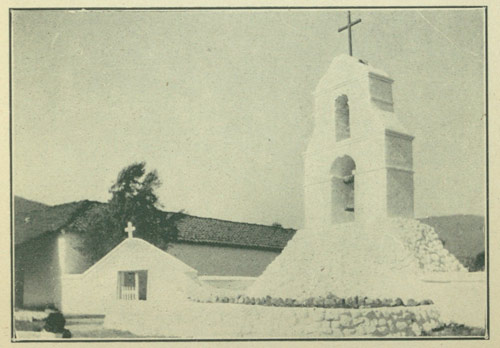

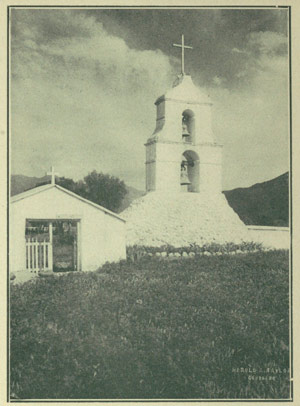

The Pala Campanile, Showing the Cactus Growing by the Side of the Cross.

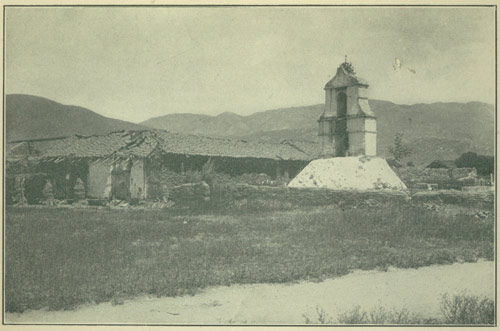

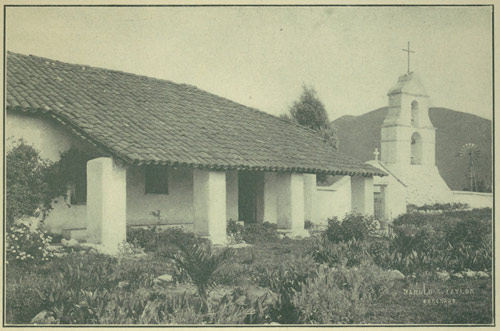

The Pala Chapel and Campanile Before the Restoration.

In this earlier account he adds comment upon the treatment some of the Indians received at the hands of their superiors which would lead one to infer that the rule of the padres was one of harsh severity rather than of affection and wise discipline. Later, however, he writes more moderately, as follows:

On the inside of the main building it formed a large square, where he found at least one or two hundred young Indian girls busily employed spinning, each one with her spinning wheel, and the different apartments around were occupied with the different trades, such as carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, tailors, most useful for the establishment. There were also weavers, busily at work weaving blankets, all apparently contented and happy in their vocation. Passing out of the square, he strolled towards the garden, where he entered and found, much to his surprise, a great variety of fruit trees—pears, apples, peaches, plums, figs, oranges and lemons, besides a large vineyard, bearing the choicest grapes.

While it is very possible the Mission of San Juan Capistrano—the next one further north—was 12 the most imposing, architecturally, of all the California Missions in its prime, it was not allowed to stand long enough for us to know its glory, the earthquake of 1812 destroying its tower, after which time it remained in ruins. San Luis Rey suffered materially from the hands of the spoilers during the sad epoch of Secularization and when I first saw it, some thirty years ago, nearly all its outbuildings were destroyed. Yet even in its ruined condition it exercised great fascination over all who viewed it, and careful study revealed that, architecturally, it was the most perfect Mission of the whole chain. While not as solidly built as either Santa Barbara, San Carlos at Monterey or San Carlos in the Carmelo Valley, it was architecturally more perfect. Indeed it was the only Mission that combined within itself all the elements of the so-called Mission Style of architecture.

To those unfamiliar with the history of California and the Missions the question naturally arises, when they find the buildings in ruins, the Indians scattered, and all traces of the establishments' former glory gone, "Whence and Why this ruin?"

To answer fully would require more space than this brochure affords, and for further information those interested are referred to my larger work.[A] In brief it may be stated that the decline of the Missions came about through the cupidity of Mexican politicians, who deprived the padres of their temporal control, released the Indians from their parental care, committed the property of the 13 Missions into the latter's hands and then deliberately and ruthlessly robbed them on every hand. The work of demoralizing the Indians was followed by the Americans who took possession of California soon after the Mexican act of secularization of the Missions was passed, and the days of the gold excitement which came soon after pretty nearly completed the sad work.

Hence it is only since the later growth of population in California that a desire to preserve these old Missions has arisen. Under the energetic direction of Dr. Charles F. Lummis, the Landmarks Club has done much needed work in preserving them from further ruin, and at San Luis Rey the Franciscans themselves have systematically carried on the work of restoration until, save that the Indians are gone and the outbuildings are less extensive, one might deem himself at the Mission soon after its original erection. 14

Many a time when I have been journeying between Pala and San Luis Rey, pictures have arisen in my mind of the energetic Peyri. I imagined him at his multifarious duties as architect, master builder, director, priest officiating at the mass, preacher, teacher of Indians, settler of disputes between them, administrator of justice, etc., etc. But no picture has been more persistent and pleasing than when I imagined him reaching out after more heathen souls to be garnered for God and Mother Church. I have pictured him inquiring of his faithful Indians as to the whereabouts and number of other and heathen Indians, in outlying districts. He soon learned of Pala, but his great organizing and building work at San Luis Rey prevented for some time his going to see for himself. Then I pictured him walking down the quiet valley of the San Luis Rey River, talking to himself of his plans, listening to the singing of the birds which ever cheerily caroled in that picturesque vale, sometimes questioning the Indian who accompanied him as guide and interpreter.

Then I saw him on his arrival at Pala. His meeting with the chiefs, his forceful, pleasing and dominating personality at once taking hold of the aboriginal mind. Then I heard—in imagination—the 15 herald give notice of the meeting to be held next day, perhaps, and the rapid gathering of the interested Indians. Then I felt the urge of this devoted man's soul as he spoke, through his interpreter, to the dusky crowd of men, women, and children as he bade them sit upon the ground, while he unfolded his plan to them. He had come from the God of the white men, the God who loved all men and wished to save them from the inevitable consequences of their natural wickedness. With deep fervor he expounded the merciless theology of his Church and the time, tempered, however, with the redeeming love of the Christ, and the fact that through and by his ministrations they could be eternally saved.

Then, possibly, with the touch of the practical politician, he showed how, under the hands of the Spaniards, they would be trained in many ways and become superior to their hereditary enemies, the Cahuillas, and the Indians of the desert and of the far-away river that flowed from the heart of the Great Canyon down to the wonderful Great Sea (the Gulf of California). After this he expounded his plan of building a mission chapel and then—

And here I have often wondered. Did he ask for co-operation, gladly, willingly, freely accorded, or did he authoritatively announce that, on such a day work would begin in which they were expected, and would absolutely be required, to take a part? Diplomacy, persuasion, zealous love that was so urgent and insistent as to be irresistible, or manifested power, command and rude control?

Testimonies differ, some saying one thing, some another. Personally I believe the former was the 16 chief and prevailing spirit. I hope it was. I freely confess I desire to believe it was.

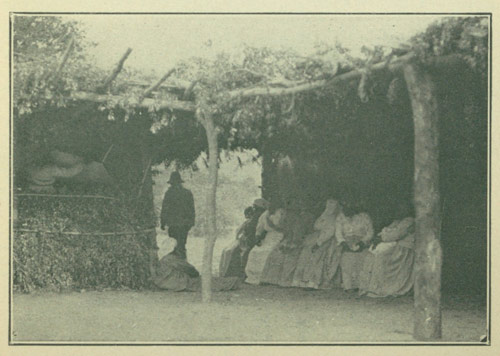

Anyhow, whichever way the influence or power was exercised, the end was gained, and in 1816, the Indians were set to work, bricks and tiles were made, lime burned, cement and plaster prepared, bands of stalwarts sent to the Palomar mountains to cut down logs for beams, which patient oxen slowly dragged down the mountain sides, through the canyons and valleys to the spot, and maidens and women, doubtless, were sent to pick up boulders out of the rocky stream bed for the covering of the base of the Campanile. In the meantime a ramada was erected (a shelter made of poles and boughs) in which morning mass was regularly held. Trained Christian Indians came over from San Luis Rey to assist in the work, and also to guide the Palas in the Christian life and the ceremonies of the Church.

What an active bustling little valley it suddenly became. Like magic the chapel was built, then the bell-tower sprang into existence, and finally, one bright morning, possibly with a thousand or more gathered from San Luis Rey to add to the thousand of Palas already assembled, the dedication of the chapel took place, named after Peyri's beloved Saint, Anthony, the miracle worker of Padua.

It was a populous valley, and the Indians were soon absorbed in the life taught them by the brown and long-gowned Franciscans. Mass every morning. Then, after breakfast, dispersion, each to his allotted toil. Year after year this continued until the Mexican diputacion, or house of legislature, passed the infamous decree of Secularization, 17 which spelled speedy ruin to every Mission of California.

Some writers, with more imagination than desire for ascertaining the facts, have asserted that the name Pala, comes from pala, Spanish for shovel, owing to the shovel or spade-like shape of the valley. The explanation is purely fanciful. It has no foundation in fact. Pala is Indian of this region for water. These were the water Indians, to differentiate them from the Indians who lived on the other side of the mountains in the desert. The Indians of Warner's Ranch, speaking practically the same language, and, therefore, evidently the same people, called themselves Palatinguas,—the hot-water Indians,—from the fact that their home was closely contiguous to some of the most remarkable hot springs of Southern California. 18

The study of the ancestors of our present-day Amerind has occupied the time and attention of many scholars with small results. Only when the ethnologist and antiquarian began to take due cognizance of language, tradition, and the physical configuration of skull and body did he begin to make due progress.

Dr. A. L. Kroeber, of the University of California, affirms that the Palas belong to what is now generally called the Uto-Aztecan stock. Distant relatives of theirs are the Shoshones, of Idaho and Wyoming; so the general name "Shoshonean" was long since applied to them. But more recent investigations have shown that the great group of Shoshonean tribes are only a part of a still larger family, all related among each other, as shown by their speech. In this grand assemblage belong the Utes of Utah, the famous snake-dancing Hopi, and the pastoral Pimas, of Arizona, the Yaki of Sonora, and, most important of all, the Aztecs of Mexico. The name Uto-Aztecan, therefore, is rapidly coming into use as the most appropriate for this family, which was and still is numerically the largest and historically the most important on the American continent. Whether the Aztecs are an offshoot from the less 19 civilized tribes in the United States, or the reverse, is not yet determined.

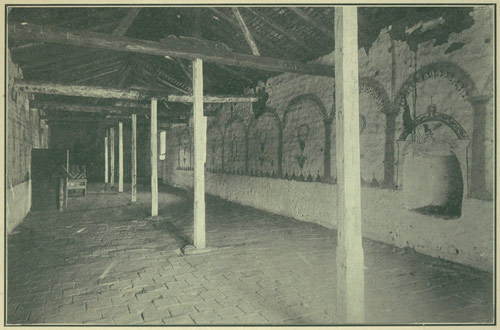

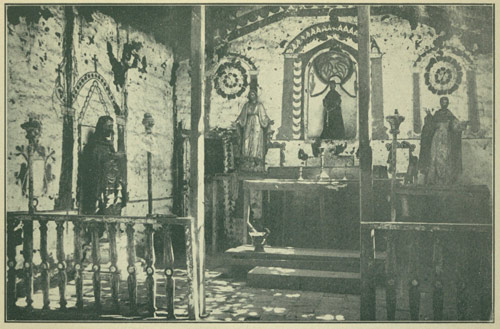

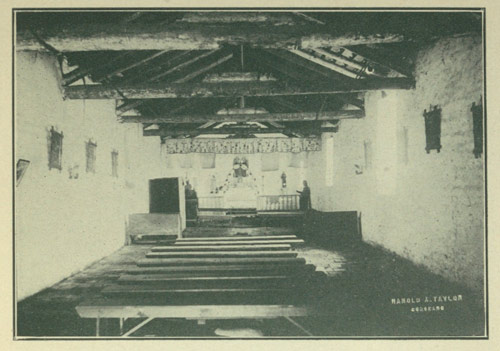

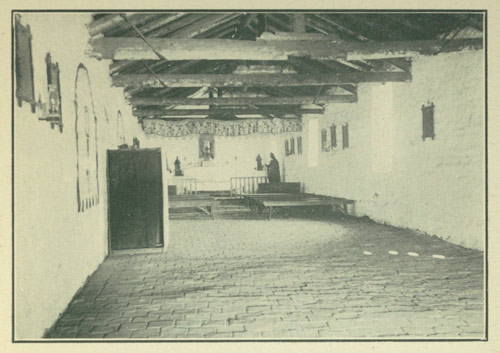

Interior of Pala Chapel Before the Restoration, Showing the Old Indian Mural Decorations.

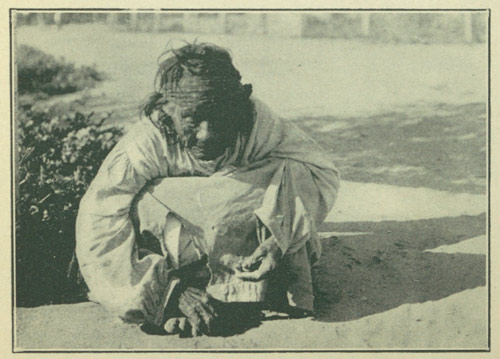

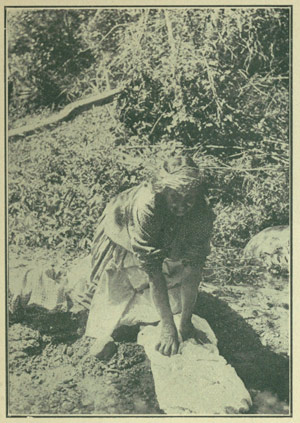

An Old San Luis Rey Mission Indian.

Statue of San Luis Rey Which Stands at the Right of the Altar in Pala Chapel.

The most conspicuous of the Uto-Aztecan tribes in San Diego County are the Indians formerly connected with the Mission of San Luis Rey, and who are called, therefore Luiseños. They know nothing of their kinship with the Aztecs but believe that they originated in Southern California. They tell a migration legend, however, of how their ancestors, led by the Eagle and their great hero, Uuyot, sometimes spelled Wiyot, journeyed by slow stages from near Mt. San Bernardino to their present homes. Uuyot was subsequently poisoned by the witchcraft of his enemies and passed away, but not until he had ordained the law and customs which the older Indians used to follow.

Old Pedro Lucero, at Saboba, years before his death told me of the earlier history of his people, and of their coming to this land. I transcribe it here exactly as I wrote it at his dictation:

Before my people came here they lived far, far away in the land that is in the heart of the setting sun. But Siwash, our great god, told Uuyot, the warrior captain of my people, that we must come away from this land and sail away and away in a direction that he would give us. Under Uuyot's orders my people built big boats and then, with Siwash himself leading them, and with Uuyot as captain, they launched them into the ocean and rowed away from the shore. There was no light on the ocean. Everything was covered with a dark fog and it was only by singing, as they rowed, that the boats were enabled to keep together.

It was still dark and foggy when the boats landed on the shores of this land, and my ancestors groped about in the darkness, wondering why they had been brought hither. Then, suddenly, the heavens opened, and lightnings flashed and thunders roared and the rains fell, and a great earthquake shook all the earth. Indeed, all the elements of earth, ocean and heaven seemed to be mixed up together, and with 20 terror in their hearts, and silence on their tongues my people stood still awaiting what would happen further. Though no one had spoken they knew something was going to happen, and they were breathless in their anxiety to know what it was. Then they turned to Uuyot and asked him what the raging of the elements meant. Gently he calmed their fear and bade them be silent and wait. As they waited, a terrible clap of thunder rent the very heavens and the vivid lightning revealed the frightened people huddling together as a pack of sheep. But Uuyot stood alone, brave and fearless, and daring the anger of 'Those Above.' With a loud voice he cried out: 'Wit-i-a-ko!' which signified 'Who's there;' 'What do you want?' There was no response. The heavens were silent! The earth was silent! The ocean was silent! All nature was silent! Then with a voice full of tremulous sadness and loving yearning for his people Uuyot said: 'My children, my own sons and daughters, something is wanted of us by Those Above. What it is I do not know. Let us gather together and bring pivat, and with it make the big smoke and then dance and dance until we are told what is required of us.'

So the people brought pivat—a native tobacco that grows in Southern California—and Uuyot brought the big ceremonial pipe which he had made out of rock, and he soon made the big smoke and blew the smoke up into the heavens while he urged the people to dance. They danced hour after hour, until they grew tired, and Uuyot smoked all the time, but still he urged them to dance.

Then he called out again to 'Those Above:' 'Witiako!' but could obtain no response. This made him sad and disconsolate, and when the people saw Uuyot sad and disconsolate they became panic-stricken, ceased to dance and clung around him for comfort and protection. But poor Uuyot had none to give. He himself was the saddest and most forsaken of all, and he got up and bade the people leave him alone, as he wished to walk to and fro by himself. Then he made the people smoke and dance, and when they rested they knelt in a circle and prayed. But he walked away by himself, feeling keenly the refusal of 'Those Above' to speak to him. His heart was deeply wounded.

But, as the people prayed and danced and sang, a gentle light came stealing into the sky from the far, far east. Little by little the darkness was driven away. First the light was 21 grey, then yellow, then white, and at last the glittering brilliancy of the sun filled all the land and covered the sky with glory. The sun had arisen for the first time, and in its light and warmth my people knew they had the favor of 'Those Above,' and they were contented and happy.

But when Siwash, the god of earth, looked around and saw everything revealed by the sun, he was discontented, for the earth was bare and level and monotonous and there was nothing to cheer the sight. So he took some of the people and of them he made high mountains, and of some smaller mountains. Of some he made rivers and creeks and lakes and waterfalls, and of others, coyotes, foxes, deer, antelope, bear, squirrel, porcupines and all the other animals. Then he made out of other people all the different kinds of snakes and reptiles and insects and birds and fishes. Then he wanted trees and plants and flowers, and he turned some of the people into these things. Of every man or woman that he seized he made something according to its value. When he had done he had used up so many people he was scared. So he set to work and made a new lot of people, some to live here and some to live everywhere. And he gave to each family its own language and tongue and its own place to live, and he told them where to live and the sad distress that would come upon them if they mixed up their tongues by intermarriage. Each family was to live in its own place and while all the different families were to be friends and live as brothers, tied together by kinship, amity and concord, there was to be no mixing of bloods.

Thus were settled the original inhabitants on the coast of Southern California by Siwash, the god of the earth, and under the captaincy of Uuyot.

The language of the Palas is simple, easy to pronounce, regular in its grammar, and much richer in the number of its words than is usually believed of Indian idioms. It comprises nearly 5,000 different words, or more than the ordinary vocabulary of the average educated white man or newspaper writer. The gathering of these words was done by the late P. S. Spariman, for years Indian trader and storekeeper, at Rincon, who was 22 an indefatigable student of both words and grammar. His manuscript is now in the keeping of Professor Kroeber, and will shortly be published by the University of California. Dr. Kroeber claims that it is one of the most important records ever compiled of the thought and mental life of the native races of California. 23

Every lover of the artistic and the picturesque on first seeing the bell-tower of Pala stands enraptured before its unique personality. And this word "personality" does not seem at all misapplied in this connection. Just as in human beings we find a peculiar charm in certain personalities that it is impossible to explain, so is it with buildings. They possess an individuality, quality, all their own, which, sometimes, eludes the most subtle analysis. Pala is of this character. One feels its charm, longs to stand or sit in contemplation of it. There is a joy in being near to it. Its very proximity speaks peace, contentment, repose, while it breathes out the air of the romance of the past, the devoted love of its great founder, Peyri, the pathos of the struggles it has seen, the loss of its original Indians, its long desertion, and now, its rehabilitation and reuse in the service of Almighty God by a band of Indians, ruthlessly driven from their own home by the stern hand of a wicked and cruel law to find a new home in this gentle and secluded vale.

As far as I know or can learn, the Pala Campanile, from the architectural standpoint, is unique. Not only does it, in itself, stand alone, but in all architecture it stands alone. It is a free building, unattached to any other. The more one 24 studies the Missions from the professional standpoint of the architect the more wonderful they become. They were designed by laymen—using the word as a professed architect would use it. For the padres were the architects of the Missions, and when and where and how could they have been trained technically in the great art, and the practical craftsmanship of architecture? Laymen, indeed, they were, but masters all the same. In harmonious arrangement, in bold daring, in originality, in power, in pleasing variety, in that general gratification of the senses that we feel when a building attracts and satisfies, the priestly architects rank high. And, as I look at the Pala Campanile, my mind seeks to penetrate the mind of its originator. Whence conceived he the idea of this unique construction? Was it a deliberate conception, viewed by a poetic imagination, projected into mental cognizance before erection, and seen in its distinctive beauty as an original and artistic creation before it was actually visualized? Or was it mere accident, mere utilitarianism, without any thought of artistic effect? We must remember that, to the missionary padres, a bell-tower was not a luxury of architecture, but an essential. The bells must be hung up high, in order that their calling tones could penetrate to the farthest recesses of the valley, the canyons, the ravines, the foothills, wherever an Indian ear could hear, an Indian soul be reached. Indians were their one thought—to convert them and bring them into the fold of Mother Church their sole occupation. Hence with the chapel erected, the bell-tower was a necessary accompaniment, to warn the Indian of services, to attract, allure and 25 draw the stranger, the outsider, as well as to remind those who had already entered the fold. In addition its elevation was required for the uplifting of the cross—the Emblem of Salvation.

It is evident, from the nature of the case, that here was no great and studious architectural planning, as at San Luis Rey. This was merely an asistencia, an offshoot of the parent Mission, for the benefit of the Indians of this secluded valley, hence not demanding a building of the size and dignity required at San Luis. But though less important, can we conceive of it as being unimportant to such a devoted adherent to his calling as Padre Peyri? Is it not possible he gave as much thought to the appearance of this little chapel as he did to the massive and kingly structure his genius created at the Mission proper? I see no reason to question it. Hence, though it does sometimes occur to me that perhaps there was no such planning, no deliberate intent, and, therefore, no creative genius of artistic intuition involved in its erection, I have come to the conclusion otherwise. So I regard Pala and its free-standing Campanile as another evidence of devoted genius; another revelation of what the complete absorption of a man's nature to a lofty ideal—such, for instance, as the salvation of the souls of a race of Indians—can enable him to accomplish. One part of his nature uplifted and inspired by his passionate longings to accomplish great things for God and humanity, all parts of his nature necessarily become uplifted. And I can imagine that the good Peyri awoke one morning, or during the quiet hours of the night, perhaps after a wearisome day with his somewhat wayward charges, or 26 after a sleep induced by the hot walk from San Luis Rey, with the picture of this completed chapel and campanile in his mind. With joy it was committed to paper—perhaps—and then, hastily was constructed, to give joy to the generations of a later and alien race who were ultimately to possess the land.

On the other hand may it not be possible that the Pala Campanile was the result of no great mental effort, merely the doing of the most natural and simple thing?

Many a man builds, constructs, better than he knows. It has long been a favorite axiom of my own life that the simple and natural are more beautiful than the complex and artificial. Just as a beautiful woman, clothed in dignified simplicity, in the plainest and most unpretentious dress, will far outshine her sisters upon whose costumes hours of thought in design and labor, and vast sums for gorgeous material and ornamentation have been expended, so will the simply natural in furniture, in pottery, in architecture make its appeal to the keenly critical, the really discerning.

Was Peyri, here, the inspired genius, fired with the sublime audacity that creates new and startling revelations of beauty for the delight and elevation of the world, or was he but the humble, though discerning, man of simple naturalness who did not know enough to realize he was doing what had never been done before, and thus, through his very simplicity and naturalness, stumbling upon the daring, the unique, the individualistic and at the same time, the beautiful, the artistic, the competent? 27

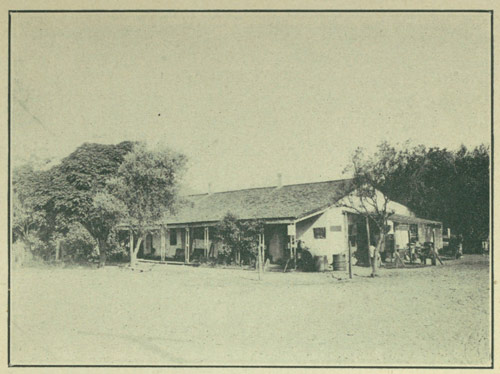

The Store and Ranch-House at Pala.

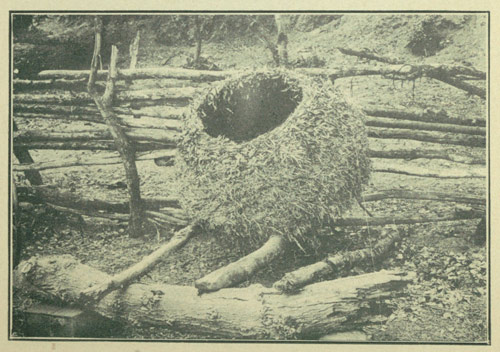

A Suquin, or Acorn Granary, Used by the Pala Indians.

The Old Altar at Pala Chapel, Before the Restoration.

In either case the effect is the same, and, whether built by accident or design, the result of mere utilitarianism or creative genius, the world of the discerning, the critical, and the lovers of the beautifully unique, the daringly original, or the simply natural, owe Padre Peyri a debt of gratitude for the Pala Campanile.

The height of the tower above the base was about 35 feet, the whole height being 50 feet. The wall of the tower was three feet thick.

A flight of steps from the rear built into the base, led up to the bells. They swung one above another, and when I first saw them were undoubtedly as their original hangers had placed them. Suspended from worm-eaten, roughly-hewn beams set into the adobe walls, with thongs of rawhide, one learned to have a keener appreciation of leather than ever before. Exposed to the weather for a century sustaining the heavy weight of the bells, these thongs still do service.

One side of the larger bell bears an inscription in Latin, very much abbreviated, as follows:

Stus Ds Stus Ftis Stus Immortlis Micerere Nobis. An. De 1816 I. R.

which being interpreted means, "Holy Lord, Holy Most Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, Pity us. Year of 1816. Jesus Redemptor."

The other side contains these names in Spanish: "Our Seraphic Father, Francis of Asissi. Saint Louis, King. Saint Clare, Saint Eulalia. Our Light. Cervantes fecit nos—Cervantes made us."

The smaller bell, in the upper embrasure, bears the inscription: "Sancta Maria ora pro nobis"—Holy Mary, pray for us. 28

The Campanile stands just within the cemetery wall. Originally it appeared to rest upon a base of well-worn granite boulders, brought up from the river bed, and cemented together. The revealing and destroying storm of 1916 showed that these boulders were but a covering for a mere adobe base, which—as evidenced by its standing for practically a whole century—its builders deemed secure enough against all storms and strong enough to sustain the weight of the superstructure. Resting upon this base which was 15 feet high, was the two-storied tower, the upper story terraced, as it were, upon the lower, and smaller in size, as are or were the domes of the Campaniles of Santa Barbara, San Luis Rey, San Buenaventura and Santa Cruz. But at Pala there were no domes. The wall was pierced and each story arched, and below each arch hung a bell. The apex of the tower was in the curved pediment style so familiar to all students of Mission architecture, and was crowned with a cross. By the side of this cross there grew a cactus, or prickly pear. Though suspended in mid-air where it could receive no care, it has flourished ever since the American visitor has known it, and my ancient Indian friends tell me it has been there ever since the tower was built. This assertion may be the only authority for the statement made by one writer that:

One morning just about a century ago, a monk fastened a cross in the still soft adobe on the top of the bell tower and at the foot of the cross he planted a cactus as a token that the cross would conquer the wilderness. From that day to this this cactus has rested its spiny side against that cross, and together—the one the hope and the inspiration of the ages, and the other a savage among the scant bloom of the desert—they 29 have calmly surveyed the labor, the opulence, the decline, and the ruin of a hundred years.

One writer sweetly says of it:

It is rooted in a crack of the adobe tower, close to the spot where the Christian symbol is fixed, and seemed, I thought, to typify how little of material substance is needed by the soul that dwells always at the foot of the cross.

Another story has it that when Padre Peyri ordered the cross placed, it was of green oak from the Palomar mountains. Naturally, the birds came and perched on it, and probably nested at its foot, using mud for that purpose. In this soft mud a chance seed took lodgment and grew.

Be this as it may the birds have always frequented it since I have known it, some of them even nesting in the thorny cactus slabs. On one visit I found a tiny cactus wren bringing up its brood there, while on another occasion I could have sworn it was a mocking-bird, for it poured out such a flood of melody as only a mocking-bird could, but whether the nest there belonged to the glorious songster, or to some other feathered creature, I could not watch long enough to tell.

Other birds too, have utilized this tower from which to launch forth their symphonies and concertos. In the early mornings of several of my visits, I have gone out and sat, perfectly entranced, at the rich torrents of exquisite and independent melody each bird poured forth in prodigal exuberance, and yet which all combined in one chorus of sweetness and joy as must have thrilled the priestly builder, if, today, from his heavenly home he be able to look down upon the work of his hands.

It must not be forgotten, in our admiration for the separate-standing Campanile of Pala, and the 30 general belief that it is the only example in the world, that others of the Franciscan Missions of California practically have the same architectural feature. While the well-known campanile of the Mission San Gabriel is not, in strict fact, a separate standing one, the bell-tower itself is merely an extension of the mission wall and practically stands alone. The same method of construction is followed at Mission Santa Inés. The fachada of the church is extended, to the right, as a wall, which is simply a detached belfry. And, as is well known, the campanile of San Juan Capistrano, erected after the fall of the bell-tower of the grand church in the earthquake of 1812, is a mere wall, closing up a passage between two buildings, with pierced apertures in which the bells are hung. 31

The original purpose of the Spanish Council, as well as of the Church, in founding the Missions of California, was to train the Indians in the ways of Christianity and civilization, and, ultimately, to make citizens of them when it was deemed they had progressed far enough and were stable enough in character to justify such a step.

How long this training period would require none ventured to assert, but whether fifty years, a hundred, or five hundred, the Church undertook the task and was prepared to carry it out.

When, however, the republic of Mexico fell upon evil days and such self-seekers as Santa Anna became president, the greedy politicians of Mexico and the province of California saw an opportunity to feather their own nests at the expense of the Indians. Let the reader for a few moments picture the general situation. Here, in California, there were twenty-one Missions and quite a number of branches, or asistencias. In each Mission from one to three thousand Indians were assembled, under competent direction and business management. It can readily be seen that fields grew fertile, flocks and herds increased, and possessions of a variety of kinds multiplied under such conditions. All these accumulations, however, it must not be forgotten, were not regarded by the padres as their own property, or that of the 32 Church. They were merely held in trust for the benefit of the Indians, and, when the time eventually arrived, were to be distributed as the sole and individual property of the Indians.

Had that time arrived? There is but one opinion in the minds of the authorities, even those who do not in all things approve of the missionaries and their work. For instance, Hittell says:

In other cases it has required hundreds of years to educate savages up to the point of making citizens, and many hundreds to make good citizens. The idea of at once transforming the idle, improvident and brutish natives of California into industrious, law-abiding and self-governing town people was preposterous.

Yet this—the making of citizens of the Indians—was the plea under which the Missions were secularized. The plea was a paltry falsehood. The Missions were the plum for which the politicians strove. Here is what Clinch writes of San Luis Rey:

Under Peyri's administration, despite its disadvantages of soil, San Luis Rey grew steadily in population and material prosperity. In 1800 cattle and horses were six hundred and sheep sixteen hundred. The wheat harvest gave two thousand bushels, but corn and beans were failures and barley only gave a hundred and twenty fanegas. Ten years later 11,000 fanegas of all kinds of grain were gathered as a crop. Cattle had grown to ten thousand five hundred and sheep and hogs nearly ten thousand. The Indians had increased to fifteen hundred. Fourteen hundred and fifty had been baptized while there had been only four hundred deaths recorded. By 1826 the parent mission counted nearly three thousand Christian Indians and nearly a thousand gathered at Pala, six leagues from the central establishment. A church was built there and a priest usually resided at it. At its best time San Luis Rey counted nearly thirty thousand cattle, as many sheep and over two thousand horses as the property of its three thousand Indians. Its average grain crop was about thirteen thousand bushels. San Gabriel surpassed it in farming prosperity with a crop which reached 33 thirty thousand bushels in a year, but in population, in live stock, in the low death rate among its Indians and in the character of its church and buildings, San Luis Rey continued to the end first among the Franciscan missions.

It can well be imagined, therefore, that when the Mexican politicians decided that the time had arrived to secularize the Missions, San Luis Rey would be one of the first to be laid hold of. Pablo de la Portilla and later, Pio Pico, were appointed the commissioners, and it seems to be the general opinion that they were no better than those who operated at the other Missions, and of whom Hittell writes:

The great mass of the commissioners and their officials, whose duty it became to administer the properties of the missions, and especially their great numbers of horses, cattle, sheep and other animals, thought of little else and accomplished little else than enriching themselves. It cannot be said that the spoliation was immediate; but it was certainly very rapid. A few years sufficed to strip the establishments of everything of value and leave the Indians, who were in contemplation of law the beneficiaries of secularization, a shivering crowd of naked, and, so to speak, homeless wanderers upon the face of the earth.

It is almost impossible for one who has not given the matter due study to realize the demoralizing effect upon the Indians and the Mission buildings of this infamous course of procedure. The Indians speedily became the prey of the vicious, the abandoned, the hyenas and vultures of so-called civilization. Deprived of the parental care of the fathers, and led astray on every hand, their corruption spelt speedy extinction, and two or three generations saw this largely accomplished. Only those Indians who were too far away to be easily reached escaped, or partially escaped, the general destruction. The processes were swift, the results lamentably certain. 34

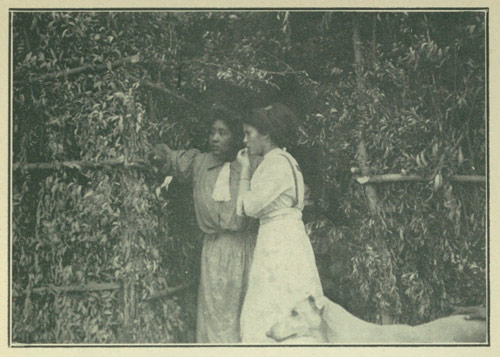

When Helen Hunt Jackson, the gifted author of the romance Ramona—over which hundreds of thousands of Americans have shed bitter tears in deep sympathy with the wrongs perpetrated upon the Indians—was visiting the Mission Indians of California, in 1883, she wrote the following sketch of Pala. This is copied from her California and the Missions, by kind permission of the publishers, Little, Brown & Co., of Boston:

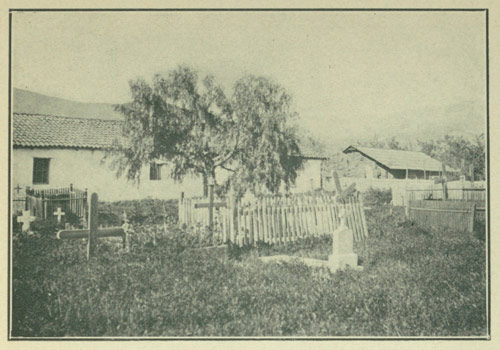

One of the most beautiful appanages of the San Luis Rey Mission, in the time of its prosperity, was the Pala Valley. It lies about twenty-five miles east (twenty miles, Ed.) of San Luis, among broken spurs of the Coast Range, watered by the San Luis River, and also by its own little stream, the Pala Creek. It was always a favorite home of the Indians; and at the time of the secularization, over a thousand of them used to gather at the weekly mass in its chapel. Now, on the occasional visits of the San Juan Capistrano priest, to hold service there, the dilapidated little church is not half filled, and the numbers are growing smaller each year. The buildings are all in decay; the stone steps leading to the belfry have crumbled; the walls of the little graveyard are broken in many places, the paling and the graves are thrown down. On the day we were there, a memorial service for the dead was going on in the chapel; a great square altar was draped with black, decorated with silver lace and ghostly funereal emblems; candles were burning; a row of kneeling black-shawled women were holding lighted candles in their hands; two old Indians were chanting a Latin hymn from a tattered missal bound in rawhide; the whole place was full of chilly gloom, in sharp contrast to the bright valley 35 outside, with its sunlight and silence. This mass was for the soul of an old Indian woman named Margarita, sister of Manuelito, a somewhat famous chief of several bands of the San Luiseños. Her home was at the Potrero,—a mountain meadow, or pasture, as the word signifies,—about ten miles from Pala, high up the mountainside, and reached by an almost impassable road. This farm—or "saeter" it would be called in Norway—was given to Margarita by the friars; and by some exceptional good fortune she had a title which, it is said, can be maintained by her heirs. In 1871, in a revolt of some of Manuelito's bands, Margarita was hung up by her wrists till she was near dying, but was cut down at the last minute and saved.

One of her daughters speaks a little English; and finding that we had visited Pala solely on account of our interest in the Indians, she asked us to come up to the Potrero and pass the night. She said timidly that they had plenty of beds, and would do all that they knew how to do to make us comfortable. One might be in many a dear-priced hotel less comfortably lodged and served than we were by these hospitable Indians in their mud house, floored with earth. In my bedroom were three beds, all neatly made, with lace-trimmed sheets and pillow-cases and patchwork coverlids. One small square window with a wooden shutter was the only aperture for air, and there was no furniture except one chair and a half-dozen trunks. The Indians, like the Norwegian peasants, keep their clothes and various properties all neatly packed away in boxes or trunks. As I fell asleep, I wondered if in the morning I should see Indian heads on the pillows opposite me; the whole place was swarming with men, women, and babies, and it seemed impossible for them to spare so many beds; but, no, when I waked, there were the beds still undisturbed; a soft-eyed Indian girl was on her knees rummaging in one of the trunks; seeing me awake, she murmured a few words in Indian, which conveyed her apology as well as if I had understood them. From the very bottom of the trunk she drew out a gilt-edged china mug, darted out of the room, and came back bringing it filled with fresh water. As she set it in the chair, in which she had already put a tin pan of water and a clean coarse towel, she smiled, and made a sign that it was for my teeth. There was a thoughtfulness and delicacy in the attention which lifted it far beyond the level of its literal value. The gilt-edged mug was her most 36 precious possession; and, in remembering water for the teeth, she had provided me with the last superfluity in the way of white man's comfort of which she could think.

The food which they gave us was a surprise; it was far better than we had found the night before in the house of an Austrian colonel's son, at Pala. Chicken, deliciously cooked, with rice and chile; soda-biscuits delicately made; good milk and butter, all laid in orderly fashion, with a clean tablecloth, and clean, white stone china. When I said to our hostess that I regretted very much that they had given up their beds in my room, that they ought not to have done it, she answered me with a wave of her hand that "It was nothing; they hoped I had slept well; that they had plenty of other beds." The hospitable lie did not deceive me, for by examination I had convinced myself that the greater part of the family must have slept on the bare earth in the kitchen. They would not have taken pay for our lodging, except that they had had heavy expenses connected with Margarita's funeral.... We left at six o'clock in the morning; Margarita's husband, the "captain," riding off with us to see us safe on our way. When we had passed the worst gullies and boulders, he whirled his horse, lifted his ragged old sombrero with the grace of a cavalier, smiled, wished us good-day and good luck, and was out of sight in a second, his little wild pony galloping up the rough trail as if it were as smooth as a race-course.

Between the Potrero and Pala are two Indian villages, the Rincon and Pauma. The Rincon is at the head of the valley, snugged up against the mountains, as its name signifies, in a "corner." Here were fences, irrigating ditches, fields of barley, wheat, hay and peas; a little herd of horses and cows grazing, and several flocks of sheep. The men were all away sheep-shearing; the women were at work in the fields, some hoeing, some clearing out the irrigating ditches, and all the old women plaiting baskets. These Rincon Indians, we were told, had refused a school offered them by the Government; they said they would accept nothing at the hands of the Government until it gave them a title to their lands.

An Old San Luis Rey Mission Indian.

The Pala Campanile from the Graveyard.

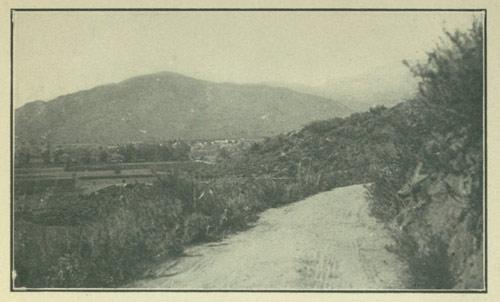

Just Entering Pala Valley on the Road from Oceanside.

An Ancient Pala Indian.

Cursed by the common fate of the Missions Pala suffered severely. In thirty years all its glory had departed as Mrs. Jackson graphically pictures in the preceding chapter. But Pala was destined to receive another blow. This is explained by Professor Frank J. Polley, formerly President of the Southern California Historical Society. In the early 'nineties he visited Pala and from an article published by him in 1893 the following accompanying extracts are quoted:

Mr. Viele, the present owner of most of the old Mission property, is the only white man residing nearby. His store and dwelling is a long, low adobe, opposite the church. Nearby is his blacksmith shop, and in the open space between the church ruins and the river are the remains of the brush booths used by the people at the yearly festival, and these, with the remnants of the mission buildings, corral walls, and the quaint Indian church with its beautiful bell tower, constitute the Pala of today.

The question naturally arises: How did Mr. Viele gain possession and ownership of the Mission property? In the course of his narrative Professor Polley gives the answer:

Trading with the Indians is a slow but simple process. An uncouth Indian figure in strange garb will silently enter the store, and, with hat in hand, stand motionless in the center of the room until Mrs. Viele chooses to recognize him. Then follow rapid sentences in the guttural tone, she executes 38 her judgment in supplying his wants and hands out the parcel, but the figure stands silently and motionless as before. Time passes, and soon the Indian is leaning against the center post. A little later the position is swiftly changed, and next when one thinks of him the figure has vanished and rejoined the group who are smoking their cigarettes by the fence. Money is seldom paid until after their crops are sold. With the squaw the transaction is different in this respect. Like her European sister, every piece of cloth has to be unrolled before purchasing; otherwise it is much the same as with the men. Both men and women are very coarse, education and morality are on a very low plane, the marital vow seems to be but little regarded, and it is no uncommon thing to see, within the shadow of the mission walls, five or six couples living in common in one room. The race is fast dying out from disease, for which the white people are largely responsible. Unable to cope with these new ills, suspicious of the government doctor, and treated like common property by the lower white element in the mountain regions, the Indians are jealous and distrustful of all; even the sick, instead of being brought to the settlement for treatment, are secreted in the hills. One old squaw of uncertain age came each day in a clumsy shuffle to the gate, and there sank her fat body into an almost indistinguishable heap of rags and flesh. The gift of a cigarette would temporarily arouse her to animation; otherwise she would sit there for hours, apparently oblivious to all that was passing, and certainly ignored by all in the house except myself. The education of the Indian here is a serious problem. They do not attend the county school, nor are they encouraged to come, as their morals are demoralizing to the rest of the class. The chief, or captain, is elected by the tribe, and, though only about 30 years of age, the present one has had his position a long time. His duties are light, and he is careful in executing his authority. He is a reasonably bright fellow, speaks English fairly well and often succeeds in securing justice for his tribe in the way of government supplies. The balance of his time he cultivates a little patch of garden, and seems to enjoy life after the Indian fashion.

Procuring the church keys was not so simple a matter, as the building is now closed and services are held at very rare intervals. This is the result of litigation. The law has invaded this sheltered haven. Years ago, when times were different and the mission was making some pretense to be a 39 living church, in the course of their duties a party of government surveyors came here. As a result of their surveys one of them told Mr. Viele in confidence that the entire mission holdings, olive orchards and lands were all on government property. Mr. Viele at once took steps to claim all, and did so. The secret leaked out, and others came in and attempted to settle on parts of the property under various claims of title, and soon the Catholic church and the claimants were engaged in a long lawsuit, which proved the death struggle of the church's interests. Mr. Viele emerged victorious, sole owner of the church, the orchard, the bells, and even the graveyard. Afterward, by deed of gift, he gave the church authorities the tumble-down ruin of the church, the dark adobe robing room, the bells and the graveyard, but, because Mr. Viele still withheld the valuable lands from the church, no services are held there, and the quarrel has gone on year by year. Mr. Viele clings to what he terms his legal rights, and the church is locked up and the Indian left largely to his own devices. Once in possession of the keys, we found them immense pieces of iron, and it took some time to unlock the door. The services of one of the Indian pupils materially assisted us in our investigations. The church is a veritable curiosity, narrow, long, low and dark, with adobe walls and heavy beams roughly set in the sides to furnish support for the roof. Canes and tules constitute this part of the structure. The earthen walls are covered with rude paintings of Indian design and of strange coloring that have preserved their tone very well indeed. Great square bricks badly worn pave the floor, and, set in deep niches along the walls at intervals, are various utensils of battered copper and brass that would arouse the cupidity of a collector of bric-a-brac. The door is strongly barred and has iron plates set with large rivets. The strange light that comes through the narrow windows and broken roof sheds an unnatural glow on the paintings upon the walls and puts into strange relief the ruined altar far distant in the church. Three wooden images yet remain upon the altar, but they are sadly broken and their vestments are gone. One is a statue of St. Louis, and is held in great veneration by the Indians. They say it was secretly brought from the San Luis Rey Mission and placed here for safe keeping. When the annual reunion of the Indians takes place this image is decorated in cheap trappings and occupies the post of honor 40 in the procession. The robing room is a small, dark apartment behind the altar, where not a ray of light could enter. We dragged a trunkful of altar trappings and saints' vestments out into the light. The dust lay thickly upon the garments in these old chests, and it is to be hoped that no one with a shade less of morality than we had will ever explore their treasures, or the church may be robbed and the images suffer much loss of their decorative attire. Undoubtedly everything of value has long since been removed, but what remains is very quaint and odd, being largely of Indian workmanship. Everything about this simple structure spoke of slow and patient work by the native workmen, and it needed but little imaginative power to conjure up the scene when men were hauling trees from the mountains, making the shallow, square bricks, preparing the adobe, and later painting these walls as earnestly perhaps as did some of the greater artists in the gorgeous chapels of cultivated Rome. The hinges creaked loudly and the great key grated harshly in the rusty lock as we spent some time in securing the fastenings at our departure. The beauty of the valley and the bright sunlight were in great contrast to the cool shadows of the dimly-lighted church. Once outside, we again made the circuit of the outlying walls, where birds sing and grasses grow from the ruined walls of the adobes. Through gaps in them we passed from one enclosure to another, this one roofless, that one nearly so, and a third so patched up as to hold a few Indians who make it their home, and in tiny gardens cultivate a few flowers or vegetables and prepare their food in basins sunken in the firm earth. A few baskets are yet left in this community, but of poor quality, the more valuable ones having been long since gathered by collectors, or sold and gambled by the Indians themselves. Many curious relics still exist, however, for those who are willing to pay several times the value of each article.

Pala remained in much the same condition described above, its Indians slowly decreasing in numbers, until the events occurred described in the following chapters. 41

In the restoration of Pala chapel the Landmarks Club of Los Angeles, incorporated "to conserve the Missions and other historic landmarks of Southern California," under the energetic presidency of Charles F. Lummis, did excellent work. November 20 to 21, 1901, the supervising committee, consisting of architects Hunt and Benton and the president, visited Pala to arrange for its immediate repair. The following is a report of its condition at the time:

The old chapel was found in much better condition for salvage than had been feared. The earthquake of two years ago—which was particularly severe at this point—ruined the roof and cracked the characteristic belfry, which stands apart. But thanks to repairs to the roof made five or six years ago by the unassisted people, the adobe walls of the chapel are in excellent preservation. Even the quaint old Indian decorations have suffered almost nothing. The tile floor is in better condition than at any of the other Missions, but hardly a vestige of the adobe-pillared cloister remains. Tiles are falling into the chapel through yawning gaps, and it is really dangerous to enter. It will be necessary to re-roof the entire structure. The sound tiles will be carefully stacked on the ground, the timbers removed, and a solid roof-structure built, upon which the original tiles will be replaced. The original construction will be followed; and round pine logs will be procured from Mt. Palomar to replace those no longer dependable. The cloisters will be rebuilt precisely as they were, and invisible iron bands will be used to strengthen the campanile against possible later earthquakes.

Then follows an interesting account of a small gathering, after the committee had formulated its plans, which took place in the little store. Here is Mr. Lummis's account of it:

The immediate valley contains about a dozen "American" families, and about as many more Mexicans and Indians, and about 15 heads of these families were present. After a brief statement of the situation, the Paleños were asked if they would help. "I will give 10 days' work," said John A. Giddens, the first to respond. "Another ten," said Luis Carillo. And so it went. There was not a man present who did not promise assistance. The following additional subscriptions were taken in ten minutes: Ami V. Golsh, 25 days' work; Luis Soberano, 15 days; Isidoro Garcia, 10 days; Teofilo Peters and Louis Salmons, 5 days each with team (equivalent to 10 days for a man); Dolores Salazar, Eustaquio Lugo, Tomas Salazar, Ignacio Valenzuela, 6 days each; Geo. Steiger and Francisco Ardillo, 5 days each. These subscriptions amount to at least $1.75 a day each, so the Pala contribution in work is full $217. Besides this Mr. Frank A. Salmons subscribed $10; and other contributions are expected. It is also fitting that the Club acknowledge gratefully the courtesies which gave two days of Mr. Golsh's time to bringing the committee from and back to Fallbrook, and the charming entertainment provided by Mr. and Mrs. Salmons. The entire trip was heart-warming; and the liberal spirit of this little settlement of American ranchers and Indians and Mexicans surpasses all records in the Club's history. For that matter, while Mr. Carnegie is better known, he has never yet done anything so large in proportion.

In July, 1903, Out West, an account was given of the repairs accomplished. The chapel, a building 144×27 feet, and rooms to its right, 47×27 feet, were reroofed with brick tiles; the broken walls of the entire front built up solidly and substantially to the roof level, the ugly posts from the center of the chapel taken out and the trusses strengthened by the addition of the tension members which the 43 original builders had failed to supply. This greatly improved the appearance of the chapel.

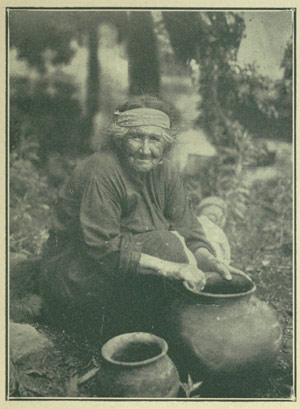

A Pala Pottery Maker.

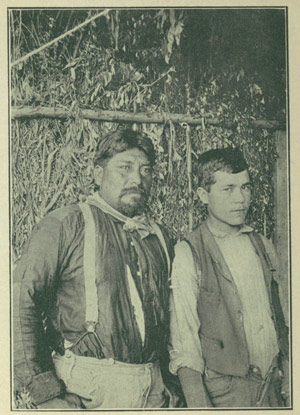

Two Palatingua Exiles, Father and Son.

The Lower Bell in the Pala Campanile.

Another beneficial service rendered was the securing of a deed from the squatter, whose story is told in another chapter, to the picturesque ruins and thus transfering them back to their rightful owners—the Catholic church, in trust for the Indians.

Unfortunately, soon after the Palatinguas came here, the resident priest, whom Bishop Conaty appointed to minister to them, did not understand Indians, their childlike devotion to the things hallowed by association with the past, and their desire to be consulted about everything that concerned their interests. Therefore, being suspicious, too, on account of their recent eviction, they were outraged to find the chapel interior freshly whitewashed so that all its ancient decorations were covered. This was another white man's affront which caused irritation and bitterness that it required months to assuage. 44

States and nations, even as individuals, are often tempted in diverse ways to forsake the path of rectitude, and, for material gain, territorial acquisition, or other supposed good, to do dishonorable things. To my mind one of the chief blots on the escutcheon of the United States is its treatment of the Indians, and California, as a sovereign state, cannot escape its individual responsibility for its utterly reprehensible treatment of its dusky "original inhabitants."

When the Spaniards seized the land their laws were clean-cut and clear in regard to the confiscation of the lands of the Indians. It was made the duty of certain officials, under direct penalties, to see that they were never, under any excuse, pretense, or even legal process, deprived of the lands they had held from time immemorial. The Mexicans, in the main, effectually carried out the same just and equitable laws. But when the United States took possession of California and the new state government was formally organized, a new idea was interjected. The California law proclaimed its intention to protect the rights of the Indians, but it made it the duty of the Indians, within a certain specified time, to come before a duly authorized officer and declare what lands were theirs and that they intended to claim and 45 use. Now while on the face of it this law seems reasonable and just, in actual practice it is as cruel, wicked, and surely confiscating as is the "stand and deliver!" of the highwayman. How were the Indians to know what was required of them? What did they know of the white man and his laws? As well pass a law that all the birds who do not declare their intention of using the branches of certain trees will be shot if they appear there, as pass laws requiring Indians, ignorant of our language, our methods of procedure, to appear and declare that they intend to continue to use lands they had had uninterrupted possession of for unknown centuries. In other words, the law fiction was a deliberate and definite scheme of dishonest men to make legal the dispossession of the Indians, whenever it was found desirable. Such a case in due time arose at Warner's Ranch. Other cases innumerable might be cited, but this is the one that particularly concerns Pala.

Warner's Ranch was named after Jonathan Trumbull Warner, popularly known to the Mexicans as Juan José Warner, who came from Lyme, Conn., by way of St. Louis, Santa Fe and the Gila River, to California, in 1831. In 1834 he settled down in Los Angeles, marrying, in 1837, at San Luis Rey Mission, Anita Gale, the daughter of Capt. W. A. Gale, of Boston. The maiden, however, had been in California ever since she was five years old, her father having placed her in the home of Doña Eustaquia Pico, the widowed mother of Pio Pico, the last Mexican Governor of California. In due time he (Warner) was naturalized as a Mexican citizen and received from the 46 Mexican Governor in 1844 the grant of an immense tract of land in San Diego County, long known as El Valle de San José. It was fine pasture land, but it was especially noted for its hot springs—Agua Caliente—near which the Indians had had their village from time immemorial. According to Spanish and Mexican law, it must be remembered, their right to their homes and adjacent pasture lands was inalienable without their own consent. Hence under Warner's regime they lived content and happy, uninterfered with, and never worried that a grant—of which they knew nothing—had been made of their lands without any clause of exemption preserving to them their time-honored rights.

Then came Fremont, Sloat and Kearny. California became a state of the United States and among other laws passed the one referring to the lands of the Indians noted above. As he passed by Palatingua, Genl. Kearny, according to the oldest man of the village, Owlinguwush, who acted as his guide, solemnly pledged his government not to remove the Indians from their lands, provided they would be friends of the new people.

This the Indians were. The white people soon learned the value of the hot springs, and flocked thither in great numbers to drink and bathe in the waters. The Indians charged them a small fee for the use of the bath-houses and tubs they had prepared. This added to their modest income, gained from their industries as cattle-men, hunters, farmers, basket and pottery-makers. They were happy, healthy, fairly prosperous and contented.

But in time Warner died. His grant was duly 47 confirmed by the United States Land Courts, but no one cared enough to see that the rights of the Indians were guarded, hence the confirmation and deed of grant contained no exemption of the Indians' lands.

The ownership changed until it came into the hands of a well-known California capitalist. He was not interested in Indians, had no particular sympathy with or for them, and did not see why they should remain on his land. Several times he vigorously intimated that he wanted them to "clear off," he needed the land, and especially he needed the hot springs. There was a strongly expressed desire that a health and pleasure resort be established at this charming place, but, of course, it was impossible so long as the Indians were there. Each time removal was intimated to the Indians they laughed—as children laugh if you tell them you are going to buy them from their parents. Had they not lived here long before a white man had ever set foot on the continent? Were they not born here, raised, married, had their children, died and were buried here for centuries? Had not Spaniards, Mexicans, and even General Kearny assured them they were secure in their possession? Of course they laughed! Who wouldn't?

But the owner of the land grew tired of their smiles. He wanted the place, so his lawyers ordered the Indians to vacate, and the papers were served in such manner that even the childlike aborigines were compelled to realize that something serious was going to happen. But that they should be compelled to leave! Ah, impossible! No one possibly could be so cruel and wicked as that.

The courts were appealed to, and finally the 48 State Supreme Court decided against the Indians, by a vote of four to three—a decision so contrary to the spirit of honor and justice that it aids in making anarchists and revolutionists of good and law-abiding men. Confident in the right of the Indians' cause their faithful friends took the case up to the United States Supreme Court, and again, this time purely on the plea of precedent—that it was contrary to rule for the United States Supreme Court to interfere in any case that was purely domestic to one State—the judgment ousting the Indians was confirmed.

Things now began to look serious. Some of the Indians were crushed by the decision, others were ugly and wanted to fight. Various people of various temperaments interfered, and each one denounced the others as trouble-makers and brewers of mischief. Council after council was held, and at each one the Indians stedfastly refused to leave their homes.

In the meantime, realizing that the suit for eviction most probably would go against the Indians, certain societies and individuals, prompted by their interest in them and by their inherent sense of justice, appealed to Congress to find a new home for these people if they were dispossessed.

For the first time in its history, Congress voted $100,000 to give to these Indians a better home than the one they were to be evicted from. A special inspector was sent out to determine where this new home should be. He reported favorably upon a site, which, however, better informed people in the state, considered altogether unsuitable. Protests immediately were lodged with the Indian Department and as the result a Commission was 49 appointed to investigate conditions, and find the most suitable place to which the Palatinguas could be transferred. This Commission was composed of Charles F. Lummis, Russell C. Allen, and Chas. L. Partridge.

After weeks of careful and patient investigation, criticized on every hand by those who were anxious to sell any kind of an acreage to the Indians, it was finally decided to recommend the purchase of the Pala Valley. Few seemed to see the irony of this decision. The land once had belonged to the Pala Indians. Less than a century before a thousand of them were regular attendants at the little Mission Chapel and devoted friends of Padre Antonio Peyri. Whence had these and their descendants gone? How had they been deprived of their lands? In another chapter I have quoted from Frank J. Polley, how our California laws aided and abetted the spoliators and how Pala unjustly came into the possession of a white man.

Now it must be bought back again. There were 3,500 acres, with a large amount of hilly government land that would be of use for pasturage and that could be added to the full purchased land as a reservation. The Commission claimed, and doubtless believed, there was plenty of water, but it was not long before the supply was found to be so inadequate that something had to be done to add to it. This has been done, as is elsewhere related.

Congress passed the appropriation bill, made the purchase, May 27, 1902, setting the land aside as a permanent reservation. The Indian Department, therefore, ordered the immediate transfer of the 50 Indians from Palatingua, as well as small bands from Puerta de la Cruz, Puerta Chiquita, San José, San Felipe and Mataguaya—tiny settlements on the fringe of Warner's Ranch and who were made parties to the ejectment suit—to Pala.

Serious trouble was feared. Mr. Lummis wired for troops to aid in the removal, although his duties as head of the Commission to choose a home for the Indians gave him no authority to act in the matter. He was thereupon ordered from the ranch, and the work of removal committed to the care of a special agent, as Dr. L. A. Wright, the regular Indian Agent, confessed his inability to cope with the situation. Mrs. Babbitt, for many years the teacher at Warner's Ranch, and other friends of the Indians counselled acquiescence to the law's demand. I was invited both by the Indians and the Indian Commissioner to be present at the removal, but I knew that it would be too much for my equanimity, so I kept away. My friend Grant Wallace, however, was present, and in Out West magazine, for July, 1903, gave the following pathetic account:

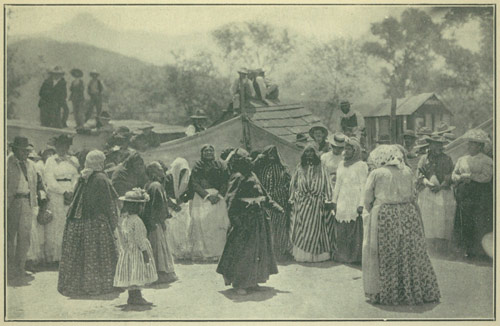

Night after night, sounds of wailing came from the adobe homes of the Indians. When Tuesday (May 12) came, many of them went to the little adobe chapel to pray, and then gathered for the last time among the unpainted wooden crosses within the rude stockade of their ancient burying ground, a pathetic and forlorn group, to wail out their grief over the graves of their fathers. Then hastily loading a little food and a few valuables into such light wagons and surreys as they owned, about twenty-five families drove away for Pala, ahead of the wagon-train. The great four and six-horse wagons were quickly loaded with the home-made furniture, bedding and clothing, spotlessly clean from recent washing in the boiling springs; stoves, ollas, stone mortars, window sashes, boxes, baskets, bags of dried fruit and acorns, and coops of chickens and ducks. 51