The Project Gutenberg EBook of Beginner's Book in Language, by H. Jeschke

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Beginner's Book in Language

A Book for the Third Grade

Author: H. Jeschke

Release Date: November 4, 2012 [EBook #41288]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BEGINNER'S BOOK IN LANGUAGE ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Sue Fleming and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

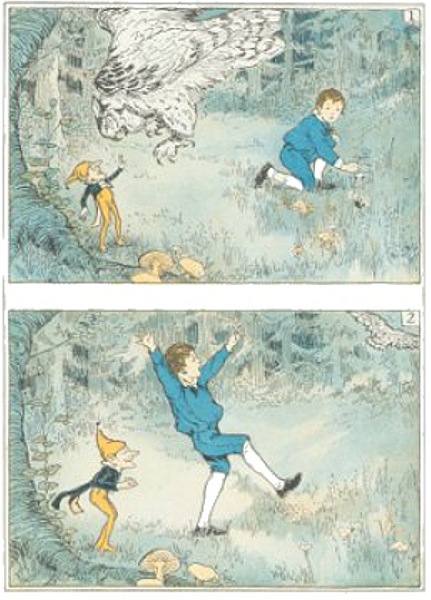

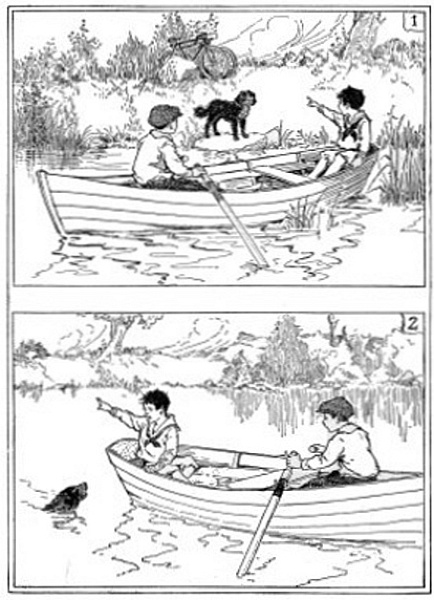

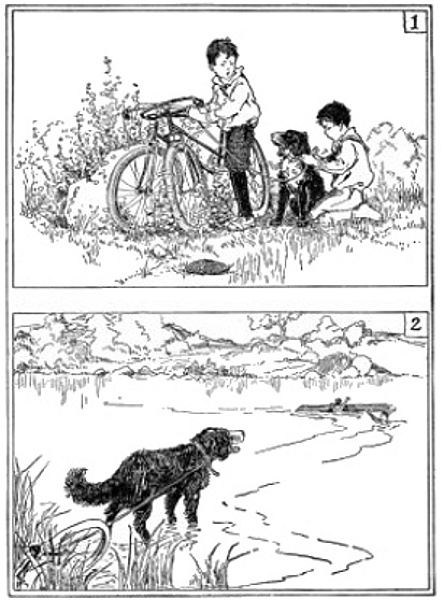

A PICTURE STORY—PARTS 1 AND 2

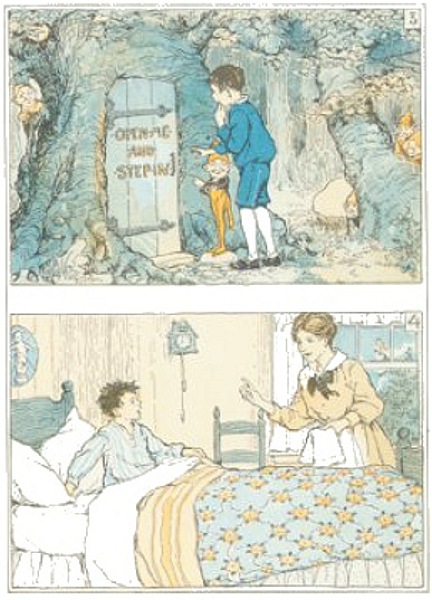

A PICTURE STORY—PARTS 1 AND 2 A PICTURE STORY—PARTS 3 AND 4

A PICTURE STORY—PARTS 3 AND 4

A BOOK FOR THE THIRD GRADE

BY

JOINT AUTHOR OF "ORAL AND WRITTEN ENGLISH"

BOOK ONE AND BOOK TWO

GINN AND COMPANY

BOSTON-NEW YORK-CHICAGO-LONDON

ATLANTA-DALLAS-COLUMBUS-SAN FRANCISCO

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY GINN AND COMPANY

ENTERED AT STATIONERS' HALL

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

622.1

The Athenæum Press

GINN AND COMPANY-

PROPRIETORS BOSTON-U.S.A.

How shall we bring it about that children of the third grade speak as spontaneously in the schoolroom as they do on the playground when the game is in full swing?

How shall we banish their schoolroom timidity and self-consciousness?

How shall we obtain from them a ready flow of thought expressed in fitting words?

How shall we interest them in the improvement of their speech?

How shall we inoculate them against common errors in English?

How shall we displace with natural, correct, and pointed written expression the lifeless school composition of the past, the laborious production of which was of exceedingly doubtful educational value and gave pleasure neither to child nor to teacher?

These are some of the questions to which this new textbook for the third grade aims to give constructive answers. Needless to say, much more is required in the way of answer than a supply of raw material for language work or a graded sequence of formal lessons in primary English.

It is the purpose of the present book to provide a series of schoolroom situations, so built up as to give pupils delightful experiences in speaking and writing good English. Since one can no more teach without the interest of the pupil than see without light, these situations have for their content the natural interests of children. They therefore include child life and the heroic aspects of mature life, fairies and fairyland, and the outer world, particularly animal life. Then, each [iv] situation is considerably extended, not only that interest may be conserved but also that it may be cumulative. Instead of the rope of sand that one finds in the textbook of unrelated assignments, there is offered here an interwoven unity of nearly a dozen inclusive groups of interrelated lessons, exercises, drills, and games. Among these groups are the fairy group, the Indian group, the fable group, the valentine group, and the circus group.

These groups or situations call for much physical activity, pantomime, dramatization. They provide for story-telling of great variety; for instruction and practice in punctuation, capitalization, and other points of form; for habit-creating drills in good English; for correct-usage games; for simple letter writing; for novel exercises in book making; and, second in importance to none of these, for the improvement by the pupils themselves of their oral and written composition,—all the work being socialized and otherwise variously motivated from beginning to end.

Careful experiments made with children of the third grade while these lessons were still in manuscript insure that the book will produce the desired results under ordinary school conditions. Very exceptional work may be expected where teachers conscientiously read the entire book at the beginning of the school year and enter into the spirit of it. That they may do this with the least expenditure of time and energy, the lessons have been provided with cross references and numerous notes.

THE AUTHOR

The four pictures at the beginning of this book tell a story. It is about a boy of your age. His name is Tom. Let us try to read that picture story. Perhaps you have already done so. Perhaps you have already found out what happened to Tom.

Oral Exercise.[2] 1. Look at the first of the four pictures. What is happening?

Perhaps the owl thinks that the little man is a little animal. Perhaps the owl wants to eat him for supper. What might the owl say if it could talk? Say it as if you were the owl.

You know, of course, that the little man is an elf. And of course he does not want to be eaten. What is he doing? Call for help as if you were an elf. Remember that the owl is after you. Call with all your might. Call as if you were frightened.

[A] Note To Teacher. Immediately preceding the Index are the Notes to the Teacher. Cross references to these are given in the text, as on the present page. Note 1 may be found on the page that follows page 168.

See the surprised look on Tom's face. Play that you are picking flowers in a meadow. Suddenly you hear a call for help. Show the class how you look up and about you to see what is the matter. What might you say when you notice the owl and the elf?

2. Look at the brave boy in the second picture. He has dropped his flowers and run over to the elf. What is he doing? What is he shouting? Do these things as if you were Tom in this picture.

Play this part of the story with two classmates.

3. The good elf has taken Tom to a wonderful tree in the woods. What do you think he is saying to Tom? Should you be a little afraid to open the door if you were Tom? Why? What questions might Tom ask before he opens it?

Play that you and a classmate are Tom and the elf in the third picture, standing in front of the door in the tree. Talk together as they probably talked together. Some of your classmates may be other elves, peeking out from behind large trees.

4. Just as Tom reached out his hand to open the door in the tree, what do you think happened? Look at the sleepy but surprised boy in the fourth picture. Why is he surprised?

Play that you are Tom. Show the class how you would look as you awoke from the exciting dream.[3] What should you probably say?

[Pg 3]Play this part of the story with a classmate. The classmate plays that she is the mother. What do you think the mother is saying to Tom? What might Tom answer?

5. Now you and several classmates will wish to play the entire story.[4]

Then it will be fun to see others[5] play it in their way. Perhaps these will play it better. Each group of pupils playing the story tries to show exactly what happened, by what the players say and do and by the way they look.

Tom awoke just as he was opening the door in the tree. We do not know what would have happened next. Perhaps there was a stairway behind the door. Perhaps this led to a beautiful garden in which were flowers of many colors and singing birds. We do not know whom Tom might have met in that garden. We do not know what might have happened there.

Oral Exercise. 1. Play that you are Tom. Tell the class your dream. But make believe that you did not wake up just as you were opening the door. Tell your classmates what happened to you after you opened it.

Perhaps you found yourself in a room that was full of elves. Perhaps the king of the elves was there. How did he show that he was glad that you had saved the life of one of his elves? What did he say? Did the elves [Pg 4] clap their hands? Did they play games with you in the woods?

Or perhaps the room was full of playthings, like a large toystore. Perhaps the elf told you to choose and take home what you wanted most.

As you and your classmates tell the dream, it will be fun to see how different the endings are.

2. It may be that the teacher will ask you and some classmates to play the best dream story that is told. The first part of it you have already played. Play it over with the new ending. The pupil who added this may tell his classmates how to play it. Should he not be one of the players? He will know, better than any one else, exactly what should be said and done.[6]

On the morning when Tom awoke from his dream he found his mother at his bedside. The first thing he did was to tell her his strange dream. This is what he said:

Mother, I dreamed about a door. It was in the trunk of a tree. A kind elf showed it to me. I drove away a wicked owl that was trying to carry the elf away.

Oral Exercise. 1. Do you think that Tom told his dream very well? Did he begin at the beginning or at the end of it? Did he leave anything out? [Pg 5]

2. Does Tom's story tell what he was doing when he first saw the elf? Does it tell how the elf looked?[8] How might Tom have begun his story?

3. Does Tom's story tell how he drove the owl away? What might Tom have said about this? Look at the second picture of the story and see what it tells.

4. Tom's story says nothing about going into the woods. It does not tell what was written on the strange door. Look again at the third picture. What does it tell you that Tom left out?

The questions you have been answering are much like the questions that Tom's mother asked him. When he answered them, Tom saw that he had not told his dream very well.

"I left out some of the most interesting things," Tom said, as he thought it over on his way to school.

A few days after this, Tom's teacher asked the pupils whether they remembered any of their dreams. Tom raised his hand. The teacher asked him to tell his dream. This is what he told his classmates:

I dreamed that I was picking flowers. The sun was shining, and the meadow was beautiful. Suddenly I heard a cry. Some one was calling for help. I turned and saw a big owl. Its claws were spread out. It was trying to get hold of a little elf and carry him away.

I ran to help the elf. The owl flew up in the air. I waved my arms and shouted and frightened it away.

The good elf said that I had saved his life. He led me into the woods where there were very large trees. In the side of one of the largest I saw a little door. OPEN ME AND STEP IN was written on it.

At first I was afraid to go near the door. But the good little elf told me to fear nothing. Just as I reached out my hand to open the door, I awoke.

Oral Exercise. Did Tom tell the class the same dream he told his mother? Read again what he told her. Now point out where he made it better. What did he add? Which additions do you like most?

Some say that one of the fairies brings the dreams. They say that it is Queen Mab, a queen of the fairies, who brings them. The following poem tells about this good fairy, who flutters down from the moon. It tells how she waves her silver wand above the heads of boys and girls when they are asleep. Then, at once, they begin to dream. They dream of the pleasantest things. They dream of delicious fruit trees and bubbling [Pg 7] fountains. Sometimes, like Tom, they dream of an elf or a dwarf who leads them over fairy hills to fairyland itself.[9]

QUEEN MAB

Thomas Hood (Abridged)[10]

Oral Exercise. 1. Let us make sure that we understand this poem. Find the following words in it and tell what you think each one means:[11]

| flutters | circle | delicious | dwarfs |

| wand | fountains | branches | dales |

2. Have you ever read about fairies? Tell the class how you think a fairy looks. If you tell it well, you may draw on the board with colored chalk your picture of a fairy. Explain your picture to the class.

3. Play that you are holding a wand in your hand. Wave it as you think the fairy waved it round the head of a sleeping child.

Written Exercise. Copy that part of the poem which you like best. Copy all the little marks that you find. Write capital letters where you find them. Every line of the poem begins with a capital letter. Perhaps you can do this copying without making a mistake.[12] [Pg 9]

Memory Exercise.[13] Read the poem aloud over and over until you can say it without looking at the book. Then stand before the class and recite it. If you make a mistake, you must take your seat. The pupil who saw your mistake may then recite the poem.

Oral Exercise. Think of some dreams you have had. Choose the one that the class would probably like to hear most, but not one that will take long to tell. Explain to the class how the dream began, what came next, what after that, and how it ended.

If you cannot remember any dream, make up one. It may be that you can make up one that will be more wonderful than any real dream of your classmates.[14] But do not make it too long.

Group Exercise.[15] After you have told your dream, your classmates will point out what they liked in the story itself and in your way of telling it. Then they will explain to you how you might have told it better. Perhaps, like Tom, you left out many interesting little points.

Oral Exercise. Make believe you dreamed that, as you were on your way to school one morning, you came upon a big elephant standing on the sidewalk. Tell the class what you did in your dream and how you got to school. [Pg 10]

Or play you dreamed that a smiling elf met you on your way to school. He gave you a pretty box. He told you to open it when you reached the schoolroom. Tell your classmates what you found in it.

Or make believe you dreamed that a lion came into the school. Tell the class what you did. Were you and the teacher the only brave ones in the room? Tell what some of your classmates did in your dream.[2]

Or play you dreamed that you found a gold coin in the schoolyard. When you could not learn who the owner was, you made a plan for spending the money for the school. Tell the class about this plan.

Perhaps the teacher will ask you and the other pupils to play some of these dream stories, if they are very interesting.

Written Exercise. 1. The teacher will write on the board one or more of the stories told by you and the other pupils.[16] The class will read them carefully and point out where each could be made better.[17] Copy one that the teacher has rewritten. The next exercise, which you may read at once, will tell you why you should do this copying without making mistakes.

2. Now the teacher will cover with a map the story on the board that you have copied, and will read it to you, while you write it again.[18] This exercise will show whether you can write a story without making any [Pg 11] mistakes. You will need to know where to put capital letters and the little marks that are placed at the ends of sentences. Besides, you will need to know the spelling of words.

3. Compare what you have written with what is on the board. Look for three things:

(1) Capital letters

(2) The mark at the end of each sentence

(3) The spelling of words

Did you have everything right? If not, correct the mistakes you made.

Some pupils use the word seen when they should use saw. Mistakes of this kind spoil stories, just as a song is spoiled when some one sings wrong notes. Let us begin to get rid of these unpleasant mistakes by learning how to use the word saw correctly.[19]

Oral Exercise. The word saw is used correctly in the three sentences that follow. Read these sentences aloud several times.

1. Tom said he saw an owl in his dream.

2. I saw a pretty dollhouse in my dream last night.

3. I dreamed that I saw a beautiful yellow bird sitting on a fruit tree and singing.

Game. Let all the pupils, except one, play that they have fallen asleep. When they have closed their eyes and rested their heads on their folded arms, the one pupil who plays that she is Queen Mab tiptoes up and down between the rows of seats. With a fairy wand she makes a circle round several heads. Then the fairy disappears, the class wakes up, and each pupil who has had a dream tells his classmates the most interesting one thing that he saw in it. Thus, one pupil might say:

I saw an elf. He was sitting in front of the door of his tree-house. He was making a toy for a little boy.

Another pupil might say:

I saw a dwarf. He was riding over the fruit-tree tops. He was on the back of a beautiful eagle.

Another might say:

I saw an owl. It had big, round, shiny eyes. It looked at me, but I was not afraid.

Still another might say:

I saw a fine white horse. It had a golden harness. A brave soldier sat on its back.

Each pupil begins with the words I saw and tries to say something that is very different from what his classmates say they dreamed, and much more wonderful.[20]

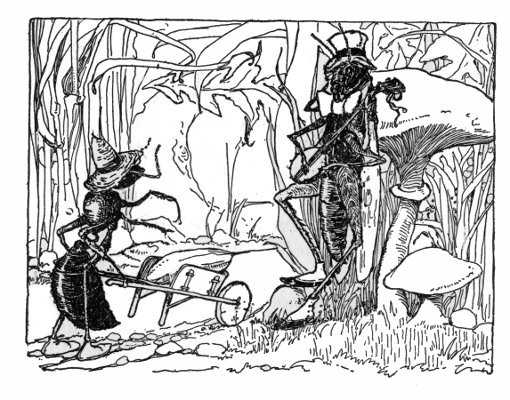

Oral Exercise. Did you ever read the story or fable of the ants and the grasshoppers? Read it carefully as it is told on this and the next pages. See whether you can tell your classmates the lesson that it teaches.

THE ANTS AND THE GRASSHOPPERS

In a field one summer day some ants were busily at work. They were carrying grain into their storehouses. As they plodded steadily to and fro under their loads, they were watched by a number of grasshoppers. The grasshoppers were not working. Instead, they were sunning [Pg 14] themselves by the roadside. Now and then these idle fellows droned out a lazy song, or joined in a dance, or amused themselves by making fun of the ants. But the ants were tireless workers. They kept steadily on. Nothing could take their minds off their business.

"Why don't you come with us and have some fun?" at last called one of the grasshoppers to the ants.

"Oh, stop that work," another cried. "Come and have a good time, as we are doing!"

But the ants kept right on with their work.

"Winter is coming," said an ant. He was busily pushing a rich grain of wheat before him. "We need to get ready for the days when we can gather no food. You had better do the same."

"Ah, let winter take care of itself," the grasshoppers shouted, all together. "We have enough to eat to-day. We are not going to worry about to-morrow."

But the ants kept on with their work. The grasshoppers kept on with their play.

When winter came, the grasshoppers had no food. One after another they died. At last only one was left. Sick with hunger, he went to the house of an ant and knocked at the door.

"Dear ant," he began, "will you not help a poor fellow who has nothing to eat?" [Pg 15]

The ant looked him over a few seconds. "So it is you, is it? As I remember, you are the lazy fellow who did not believe in work. I do not care to have anything to do with you." And he turned his back on the lazy fellow.

Sadly the grasshopper made his way to another door and knocked again.

"You have nothing to eat?" cried the ant that lived here, in great surprise. "Tell me, what were you doing while the weather was warm? Did you lay nothing by?"

"No," replied the grasshopper. "I felt so happy and gay that I did nothing but dance and sing."

"Well, then," answered the ant, "you will have to dance and sing now, as best you can. We ants never borrow. We ants never lend." And he showed the lazy fellow out of the place.

The hungry grasshopper dragged himself to a third house.

"I am sorry," said the ant that opened the door. "I can spare you nothing. All that I have I need for my own family. If you spent the summer without working, you will have to spend the winter without eating." And he shut the door in the grasshopper's face.—Æsop

Oral Exercise. 1. Show the class how you would carry a heavy load. Play that a bag of wheat stood before you. Lift it from the ground, balance it on one [Pg 16] of your shoulders, walk with it across the room, and set it carefully down in the corner. Then go back for another, and another. Let several classmates do the same.

2. Play that you and several classmates are the ants in the fable, busily carrying loads from the field to the storehouses. What might you ants be saying to each other while you work? Should you speak of the sunny day, of the pleasant field, of the fun of working together? Should you probably speak of the pleasure of seeing the grain pile up in the storehouses? Should you be thinking, now and then, of the long, cold winter ahead? What might you say about it? What might you say to each other as you pass the grasshoppers loafing by the roadside?

3. Show the class how you would walk about if you had nothing to do all day long. Would your walk be brisk? Should you look wide-awake? Play that you and several classmates are the grasshoppers in the fable. What will you do? Will you walk lazily to and fro before the class, one of you twanging a guitar, another singing, and the third dancing about? What might you grasshoppers be saying to each other about the weather? What might you say about the busy ants you see passing by with loads on their backs? What might you say about the coming winter?

4. Play the part of the fable that tells what happened in the summer. First the ants will be seen at their [Pg 17] work. They talk with each other as they work. They say what they think about the lazy grasshoppers they see in the distance. Now the grasshoppers slowly come along, humming tunes. They talk about the beautiful summer. They laugh at the hard-working ants. At last they call to the ants and invite these to join them in a dance or in a song. Read the fable to see what each thinks and says and does in this part of the story.

5. Now play that winter has come. You and several classmates may be the grasshoppers. You are shivering in the cold and have no food to eat. Remember, you grasshoppers are not singing and dancing now. What might you say to each other about the summer that is gone? One grasshopper dies of hunger. What might the others say? Another dies. What does the last one say to himself and decide to do?

6. Can you see the last grasshopper going from house to house, begging for food? How does he look? Show the class how he walks and how he talks. What does he say at each door?

7. With three classmates, that will be the three ants, play the last part of the fable,—the part in which the last grasshopper goes from door to door. The fable tells what each ant says and does.

8. Another group of pupils may now play the whole story. Let them do it in their own way.[5] If the story is played well, the class will see everything as it happened.[Pg 18]

The fable of the ants and the grasshoppers may be told in different ways.[21] You could tell it as if you were one of the ants. In that case the story might begin in this way:

I am a busy ant. I really have no time to stop to talk with you. But perhaps a few minutes' rest will do me good. Yes, I will tell you about the grasshoppers.

One day last summer I noticed some of these good-for-nothing fellows near the field where I was working. They were sunning themselves by the roadside. They were too lazy to work.

Or you could tell the fable as if you were one of the grasshoppers. Then it would perhaps begin as follows:

I am a grasshopper. I had a hard time last winter. All my companions died then. I think it is wonderful that I am still alive. But my health has been ruined.

You see, last summer we grasshoppers did not feel like doing any work. We thought it was more fun to dance and sing and to laugh at the ants. We thought they were foolish to work so hard.

Oral Exercise. Tell the fable of the ants and the grasshoppers in your own way. As you speak to your classmates, shall you play that you are an ant or a grasshopper?

Group Exercise. As each pupil tells the fable, the class will listen to see whether any important parts have been left out. The class should tell each speaker where he did well and where the fable might have been told better. There is a good way and a poor way of telling a story. Do you not remember the two ways in which Tom told his dream?

As you know, the fable of the ants and the grasshoppers teaches the lesson that during worktime one should work. The same lesson could be taught by other stories. Let us try to make up a fable of our own. Our fable should show what happens to those who will not work.

Oral Exercise. 1. What animals shall we have in our story to take the place of the ants? They must be very busy animals. They must be good workers. They must not waste their time in idleness. They must not play when they should be going about their business. Would bees do? Now, what animals shall take the place of the grasshoppers? What do you think of butterflies for this part?[Pg 20]

2. Make up a fable about bees and butterflies and tell it to your classmates. Will you tell it as if you were one of the bees? Or will you be a butterfly? Or will you tell the fable as if you were a bird or a field mouse that saw all that happened and heard all that was said?

Group Exercise. After each telling of the fable you and the other pupils should tell the story-teller, first, what things in his story you liked, and, second, what could be made better.

Sometimes pupils do not speak loud enough for the class to hear. Sometimes they do not seem strong enough to stand squarely on their two feet while they are speaking. They seem to need to hold on to a chair or table, so as not to fall. Those who stand well and speak with a clear, ringing voice should be praised for it by their classmates.[22]

Oral Exercise. Read the following ideas for stories. Perhaps you can make up a story from one of them that the class would like to hear. Perhaps you can make up a very interesting story that the class would like to play.

1. There are two dogs living in neighboring houses. One is too lazy to watch his master's house. The other is faithful. When a burglar comes, the faithful dog drives him away. Then the burglar enters the neighbor's house. There he finds the lazy watchdog fast asleep. What [Pg 21] happens next morning when the master of each dog learns what took place during the night?

2. The billboards say that a circus is coming. In a month it will be in a certain city where two boys live. These two boys plan to go. They need to earn the money for the tickets. One of them begins at once and works steadily. The other is unwilling to give up his play.

Some time ago we began to learn about the correct use of the word saw. Some pupils use saw when only seen is correct, and seen when only saw is correct. The following sentences show the correct use of these two troublesome words:

1. I saw some ants busily at work.

2. Have you seen them?

3. Have you ever seen a grasshopper at work?

4. I never saw one.

5. But I have often seen ants at work.

6. Has your brother seen the ant hill in the field?

Oral Exercise. 1. In any of the sentences above do you find saw used with have or has? Do you find seen used in any sentence without have or has? Can you make a rule for the use of saw and seen?[Pg 22]

2. Using what you have just learned about saw and seen, fill the blanks below with the correct one of the two words:

1. The grasshoppers —— the ants, and the ants —— them.

2. I have —— many ants and many grasshoppers.

3. Has any one ever —— this grasshopper doing any work?

4. I once —— two ants carrying a heavy grain of wheat together.

5. I —— them at work.

6. Have you —— the ants carrying grain this summer?

7. My brother once —— a beehive.

8. He —— hundreds of bees.

9. I have never —— butterflies gathering food for the winter.

Game. 1. The teacher sends one of the class from the room. The remaining pupils close their eyes. The teacher tiptoes to one of them and shows him a pencil (or a book or a cap) belonging to the pupil in the hall. When that one returns to the room, he asks each of his classmates in turn, "George (or Fred or Mary), have you seen my pencil?"

The answer is, "No, Tom (or Lucy or John), I have not seen your pencil," until at last the pupil is reached who has seen it. He answers, "Yes, Tom, I have seen it."

Then he in turn leaves the room, and another round of the game begins.

2. The teacher points to one pupil after another and asks each, "What did you see on your way to school?" [Pg 23]

The answers come:

1. I saw many children all going in the same direction.

2. I saw a poster of the circus that is coming to town next week.

3. I saw a farmer driving a cow.

4. I saw a policeman.

Each answer begins with the words I saw. After half a dozen pupils have spoken, the one who gave the most interesting reply[23] takes the teacher's place. He asks his classmates a question beginning with the words What did you see? He might say:

1. What did you see at church last Sunday?

2. What did you see when you visited your grandfather?

3. What did you see when you went to the woods?

After half a dozen answers, another pupil becomes the questioner. Each pupil tries to ask interesting questions and to give interesting answers.[20]

It often happens that a story is spoiled because the person who tells it makes mistakes in English. It is as unpleasant to hear a mistake in a speaker's language as it is to see a spot on a picture. You have already learned the proper use of saw and seen. In this lesson we shall take up another matter. Sometimes pupils do not pronounce all their words correctly. We must get rid of mistakes of this kind, too.

Oral Exercise. 1. Pronounce each word in the following list as your teacher pronounces it to you:

| can | when | what | often |

| catch | where | which | three |

| just | why | while | because |

2. Read the entire list rapidly, but speak each word distinctly and correctly.

3. Use in sentences the words in the list above.

Of course you have heard the fable of the foolish little chick. That chick paid no attention to its mother's warning to stay near her. You probably remember that it boldly wandered away from her and was caught by a hawk.

Oral Exercise. 1. If there are any pupils in the class who do not know the fable of the foolish chick, some pupil who remembers it clearly should tell it to them, so that all may know it. What is the lesson of that fable?

2. Make up a short fable like the one of the careless chick and the hawk. Read the following list of ideas for such a fable. Perhaps it will help you to make up an interesting story to tell the class. Perhaps the class will wish to play your story.

The Foolish Lamb and the Wolf

The Bear Cub and the Bear Trap

The Heedless Puppy and the Automobile

The Reckless Mouse and the Cat

Group Exercise. The teacher will write on the board the best of the fables that you and your classmates make. Then you and they may try to improve these fables, as Tom improved the story of his dream. Make each one as interesting as you can.[24] Think of bright things to add to each one.

Written Exercise. Copy from the board one of the fables that the class has improved. Write capital letters and punctuation marks where you find them in the fable. What you write should be an exact copy of what is on the board.[25] Do you think that there is any one in the class who can make such an exact copy? Are you that one?

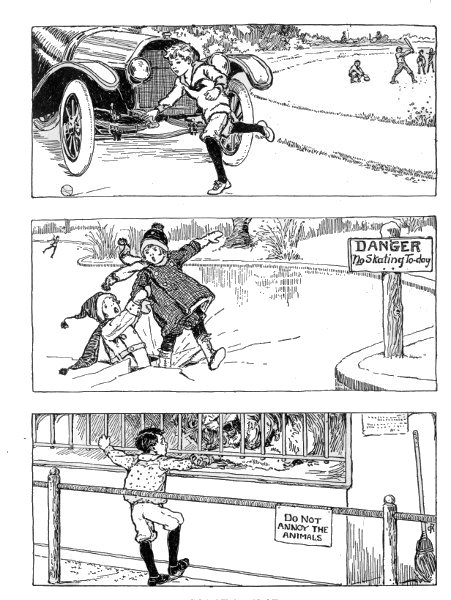

Oral Exercise. Did you ever see a sign with the words SAFETY FIRST? Explain to your classmates what you think it meant.

The three pictures on the opposite page tell three stories. Each story teaches the lesson, "Safety First."

Oral Exercise. 1. Make up a story that you and your classmates may play. Let it fit one of the three pictures. Tell it to the class.

2. Together with two or three classmates, whom you may choose yourself, play your story. Perhaps you and the other players will meet before or after school, and then you can tell them how each one must look, what he must do, and what he must say, in playing his part. Try to do it all without the teacher, but if you need the teacher's help, ask for it. Play the story once or twice before playing it in the presence of the class.

Group Exercise. Other pupils will play their stories. The class will tell what it likes and what it does not like in the playing of each story. These questions will help to show whether a story was well played:

1. Did the players say enough?

2. Did the players speak clearly, distinctly, and loud enough?

3. Did the players look and act like the persons in the story?

4. How might the story have been played better?

SAFETY FIRST

SAFETY FIRST

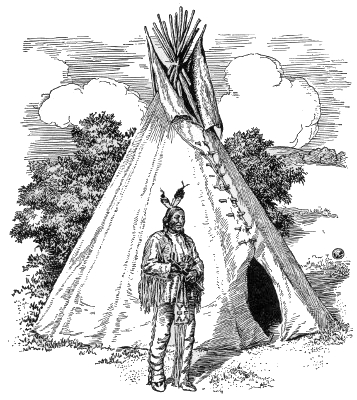

Long ago there were no cities and no railroads in our country. The white men had not yet come. Only Indians lived here. As you probably know, their houses were tents made of skins. They had no guns, but hunted with bows and arrows. Their clothes were very different from those we wear.

Oral Exercise. 1. You have probably read or heard interesting things about the Indians. What can you tell your classmates about them?

2. Of course you know that Indian children were not sent to school as you are. They did not learn to read books. Do you know what they did learn? Tell the class what you know about it.

3. Read what an Indian says in the following true story. When this Indian boy grew to be a young man, he learned English. He has written a number of books about his boyhood. As you read what follows, notice [Pg 29] how many things you are told which you never heard of before. Perhaps you had thought that little Indian boys were never afraid of the dark. This story tells how they get over it. What else does it tell that is interesting to you?

AN INDIAN BOY'S TRAINING [B]

My uncle was my teacher until I reached the age of fifteen years. He was strict and good. When I left the tepee in the morning, he would say: "Boy, look closely at everything you see." At evening, on my return, he used to question me for an hour or so.

He asked me to name all the new birds that I had seen during the day. I would name them according to the color, or the shape of the bill, or their song, or their nest, or anything about the bird that I had noticed. Then he would tell me the correct name.

One day he told me what to do if a bear or a wild-cat should attack me. "You must make the animal fully understand that you have seen him and know what he is planning to do. If you are not ready for a battle, that is, if you are not armed, the only way to make him turn away from you is to take a long, sharp-pointed pole for a spear and rush toward him. No wild beast will face this unless he is cornered and already wounded."

[B] Copyright, 1913, by Little, Brown and Company.

KNIFE IN ITS BEADED CASE

KNIFE IN ITS BEADED CASEWhen I was still a very small boy, my stern teacher began to give sudden war whoops over my head in the morning while I was sound asleep. He expected me to leap up without fear, grasp my bow and arrows or my knife, and give a shrill whoop in reply. If I was sleepy or startled and hardly knew what I was about, he would laugh at me and say that I would never become a warrior. Often he would shoot off his gun just outside the tepee while I was yet asleep, at the same time giving bloodcurdling yells. After a time I became used to this.

My uncle used to send me off after water when we camped after dark in a strange place. Perhaps the country was full of wild beasts. There might be scouts from warlike bands of Indians hiding in that very neighborhood.

Yet I never objected, for that would have shown cowardice. I picked my way through the [Pg 31] woods, dipped my pail in the water, and hurried back. I was always careful to make as little noise as a cat. Being only a boy, I could feel my heart leap at every crackling of a dry twig or distant hooting of an owl. At last I reached the tepee. Then my uncle would perhaps say, "Ah, my boy, you are a thorough warrior." Then he would empty the pail, and order me to go a second time.

Imagine how I felt! But I wished to be a brave man as much as a white boy desires to be a great lawyer or even President of the United States. Silently I would take the pail and again make the dangerous journey through the dark.—Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa), "Indian Child Life" (Adapted)

INDIAN ARROWS

INDIAN ARROWSOral Exercise. 1. Play that you are an Indian boy or girl. Make believe that you are walking through the dark woods. Remember, there may be wild beasts in the woods, or the scouts of warlike Indian bands. Show the class how you would walk and how you would look about you as you picked your way to a spring to fetch water for the camp. Tell the class what you might see and hear on this dangerous trip.

A TEPEE

A TEPEE2. Now let three or four of your classmates be white boys and girls. They are passing carefully through the same woods. Let these white children show the class exactly how they would make their way through the woods. What might they be whispering to each other?[Pg 33]

3. Play that suddenly you and the white hunters meet in these dangerous woods. At first you see them a little distance away. What do you try to do? But they have also seen you. What do they try to do? At length you find that they are friendly, and they see that they need not fear you. When you meet them, what might you say to them? What questions might you ask them? What might they ask you?

4. Make believe that the white boys and girls know very little about Indian boys, and that they wonder why you are not in school studying your lessons. What will you tell them? When they ask you whether you never learn anything, tell them what you have learned in the woods.

5. Now tell them that you know nothing about the schools to which white children go. Ask them to tell you why they go to school and what they do there. Ask them more questions until they have told you all about their school.

When the first white men who came to this country met the Indians, they learned from them some new words. The white men used these Indian words more and more. To-day we think of the words as English words, and we have almost forgotten where we got them. In talking about Indians we shall need these [Pg 34] words. Let us learn them at once. Then we shall make no mistakes when we use them.

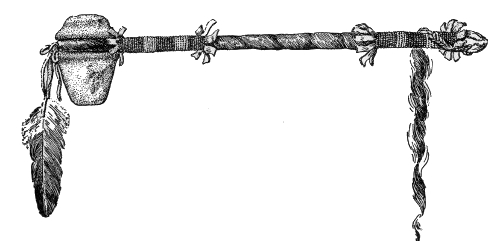

STONE HATCHET

STONE HATCHETOral Exercise. 1. Listen carefully as the teacher pronounces each word in this list of Indian words. Then pronounce it the same way. Then read the entire list distinctly and rapidly without making a single mistake.

| tepee | squaw | wampum | hominy | toboggan |

| wigwam | papoose | moccasin | tomahawk | tobacco |

2. Which of these words do you already know? Make sentences using each of these to show that you know what they mean. Learn the meaning of the others and then use them in sentences.

Group Exercise. With each of the Indian words in the list make one interesting sentence. This the teacher will write on the board. Then the entire class [Pg 35] will make it as much better as possible. The teacher will write the improved sentence on the board under the other one. Thus, with the first word in the list, you might give this sentence:

The hunter saw a tepee.

The class tries to make the sentence more interesting. At last the following sentence is seen on the board:

The brave Indian hunter saw a large new tepee in the woods.

One way of starting fire was for several of the boys to sit in a circle and, one after another, to rub two pieces of dry, spongy wood together until the wood caught fire.—Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa), "Indian Child Life"

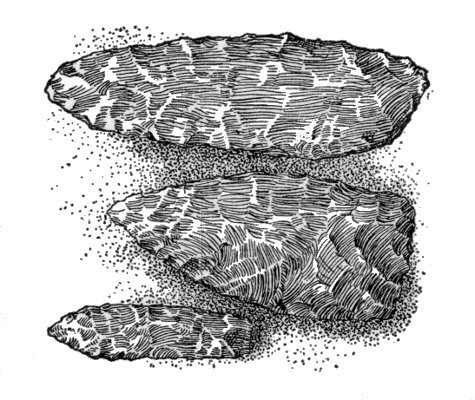

FLINT KNIVES

FLINT KNIVESOral Exercise. 1. Do you know in what kind of houses the Indians lived? Explain to the class how large you think an Indian house was, how it was made, and what kind of door it had. If you can, draw on the board a picture of the tepee about which you are talking.[Pg 36]

2. In which of the following questions are you interested most? You probably know something about it already. Learn as much more as you can. Ask your teacher and your father and mother, and try to find something about it in books. Then tell your classmates what you know. If you can draw on the board[26] a picture of the thing about which you are talking, it may help your classmates to understand you better. Or you may make a drawing on paper with colored crayons.

1. What sort of boat did Indians use and how did they make it?

2. What did the Indians wear?

3. How were the Indian babies taken care of?

4. What did the Indians use for money?

5. How are the Indians of to-day different from the Indians whom the first white men saw?

Group Exercise. 1. After each pupil's talk the class should explain to the speaker, first, what they liked in the talk, and, second, how the talk might have been better.

2. One of these talks the teacher will write on the board.[16] Then the whole class should study it together, improving it as much as possible. The following questions may help in this work:

1. Is anything important left out?

2. What could be added to make the talk more interesting?

Written Exercise. 1. When the talk that you have just been studying has been rewritten on the board in its improved form, copy it. Before doing so, read the exercise that follows. It will show you why it is very important that you try to copy the talk without making a single mistake. Look out for the spelling of words, for the capital letters, and for the punctuation marks. In this way you will be preparing for the battle in the next exercise.

2. The entire class may now be divided into two Indian tribes. The tribes are to have a battle in the schoolroom. The battle will be a writing battle. It will show which tribe can write from dictation[18] with the fewer mistakes. What you have just copied from the board is to be used for this dictation. Before the exercise begins, each tribe may give its war whoop.

WALKING STICKS USED BY THE OLD MEN OF A TRIBE

WALKING STICKS USED BY THE OLD MEN OF A TRIBE 3. Compare what you have written with what is on the board.[12] How many mistakes in spelling have you made? How many times have you written small letters where there should [Pg 38] be capitals? How many punctuation marks have you forgotten? How many mistakes have all the Indians in your tribe made? Did your tribe make fewer mistakes than the other tribe? Then your tribe may give its war whoop as a sign of victory. The losing tribe must remain silent.

What boy would not be an Indian for a while when he thinks of the freest life in the world? This life was mine. Every day there was a real hunt.—Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa), "Indian Child Life"

Oral Exercise. 1. What did Indian boys and girls enjoy that you do not have? What pleasant things do you enjoy that the Indian children had never heard of before the white men came to this country?

2. Make believe that you are an Indian boy or girl. Play that you have been asked by the teacher to visit the school. The teacher asks you to tell about your pleasant life in a tepee in the woods, and why you are glad you are an Indian. The teacher will meet you at the door, lead you before the class, and say something like this:

Boys and girls, I want to introduce you to our visitor. As you see, he is an Indian boy, who has come to us from his home in the woods. He will tell us why he likes the Indian life and why he would not exchange places with us.

What will you say to the class?

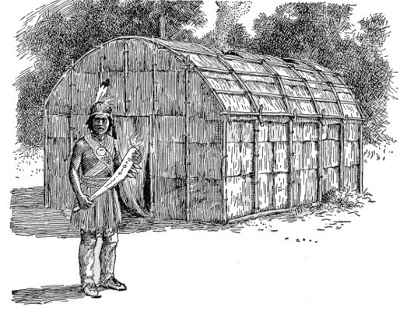

BARK WIGWAM WITH CURVED ROOF

BARK WIGWAM WITH CURVED ROOF

[Pg 39] 3. Now play that the class is a tribe of Indians. You have been captured by them as you were wandering through the woods.[27] They want you to live with them and to grow up with the Indian boys and girls. Stand before this Indian tribe. Tell them bravely why you would rather stay with the white men. Ask them to let you return to your home. Give good reasons why they should do so. Which of the following ideas will you use in your talk?

1. You would rather spend your life in the city than in the woods.

2. You like the white men's houses and ways of living better than those of the Indians.

3. You want to learn to read better so that you may enjoy many storybooks of which you have heard.

A game that Indians often played was called "Finding the Moccasin." The players formed a circle around one who stood in the center and was "it." They passed a small toy moccasin quickly from hand to hand. The one in the center tried to guess who had it. If he guessed right, then the player who had the moccasin became "it" for the next game.

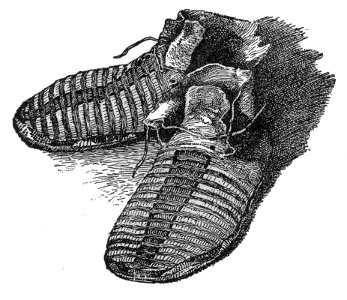

MOCCASINS

MOCCASINSGame. Make believe that you and your classmates are a band of Indians playing "Finding the Moccasin." Make a small moccasin of paper or cloth. Pass it quickly from hand to hand as you stand in a circle. Be careful that the player in the center does not see you passing it. He will ask one after another in the [Pg 41] circle, "Have you the moccasin?" The answer will always be, "No, I haven't (or have not) the moccasin," until the one who does have it answers, "Yes, I have the moccasin." Then this player is "it" for the next game.

Here are two lists of names. The second gives the Indian names for the months. As you see, the Indians use the word moon instead of the word month.

| January | Snow Moon | |

| February | Hunger Moon | |

| March | Crow Moon | |

| April | Wild-Goose Moon | |

| May | Planting Moon | |

| June | Strawberry Moon | |

| July | Thunder Moon | |

| August | Green-Corn Moon | |

| September | Hunting Moon | |

| October | Falling-Leaf Moon | |

| November | Ice-Forming Moon | |

| December | Long-Night Moon |

Oral Exercise. 1. As you read the two lists above, do you see the reason for each Indian name? Do you like the Indian names as well as the names we use? Which Indian name do you like best of all? Which do you think could be improved? Can you make up other names for the twelve months?[29]

2. Can you name the twelve months in order? Remember to pronounce all the r's in February.

3. Let twelve pupils be the twelve months. Let the pupil who is January speak first. He should tell who he is and what he brings. He might speak as follows:

I am January. The Indians call me Snow Moon. I bring cold weather, ice, and snow. Healthy boys and girls like me. When I am here, they can go coasting and skating. When I bring too much cold, they stay indoors by the fire and read books about Indians.

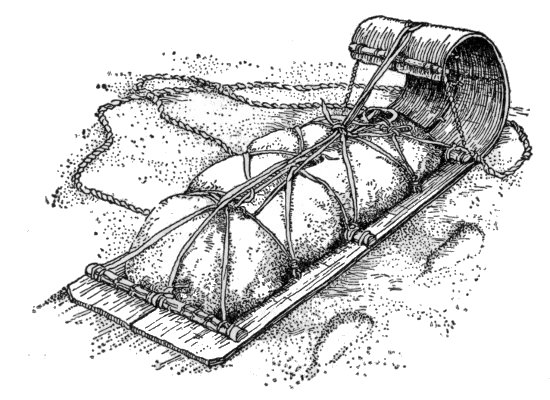

INDIAN SLED, OR TOBOGGAN

INDIAN SLED, OR TOBOGGAN

In this way each of the twelve pupils may tell the class what kind of month he is.

Group Exercise. After each month has spoken, the class should tell him, first, what was specially good in his talk, and then, what might have been better. These questions will help the class to see how good each talk was:

1. What was the best thing in the talk?

2. Did the speaker leave out anything interesting?

3. Did he use too many and's?[30]

Written Exercise. You and eleven classmates may go to the board. The teacher will name a month for each pupil. Each is to write a sentence that tells what he likes to do in one of the months. If you are to write what you like to do in November, you might write a sentence like the following:

In November I like to read books and play games by the warm fire.

While the twelve pupils are writing on the board, the pupils in their seats will write on paper.

STONE AX

STONE AXDo not forget that the name of every month begins with a capital letter. Do not forget that the word I is always written as a capital letter.

Group Exercise. 1. The class may now point out any mistakes there are in each of the twelve sentences on the board. These questions will help pupils to find mistakes:

1. Is the name of the month spelled correctly? Does it begin with a capital letter?

2. Does the sentence begin with a capital letter?

3. Does the sentence end with a period?

4. If the word I is used, is it written as a capital letter?

2. Now the sentences that pupils wrote at their desks may be read. Those that are very good may be written on the board under the ones about the same months. Then the class will point out mistakes in them, if there are any.

Oral Exercise. 1. Can you guess either one of the following riddles?

I come once in a year. I always bring Santa Claus with me. When I leave, a new year begins at once. What am I?

I come once a year. Turkeys do not like me, but everybody else gives thanks after I have been here several weeks. What am I?

2. Make riddles about the months, for your classmates to guess. Begin your riddles like the two above.

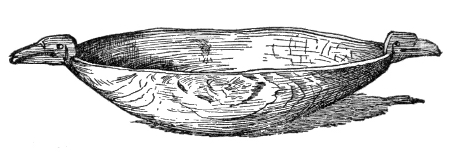

WOODEN BOWL

WOODEN BOWLGame. Twelve pupils stand in a row in front of the class. The teacher whispers to each the name of one of the months. The game is for the class to arrange these pupils in the order of the months of the year. Of course January will be placed at the beginning of the row. December will [Pg 45] be placed at the end. Each pupil in the row makes a riddle about the month he is. The class must guess who is January, who is February, and so on to December.

Those who guess the riddles may be the months in the second game.

Group Exercise. Pupils who make very good riddles may write them on the board. Then the class will try to make them still better.

BUFFALO-HORN SPOONS

BUFFALO-HORN SPOONSWritten Exercise. When the riddles on the board have been corrected, copy the one or two you like best. Take these copies home to show to your parents. Write the name of the month under each riddle you copy. Begin that name with a capital letter. How will you make sure that you have spelled it right?

Some pupils spoil their talks and stories because they make mistakes in using did and done. They say did when they should say done, and done when they should say did. The sentences at the top of the next page show these words used correctly:

1. The Indian boy did a brave deed.

2. He has done deeds of bravery before.

3. I never did anything so daring.

4. Have you done your work?

5. I had done my work long before you spoke.

Oral Exercise. 1. As you read the sentences above, try to find out when it is right to use did and when done.

2. Read the sentences again. Now notice that nowhere is the word done used unless has or have or had is used in the same sentence. Is this true of the word did also?

Let us remember, then, never to use done alone, and never to use did with have or has or had.

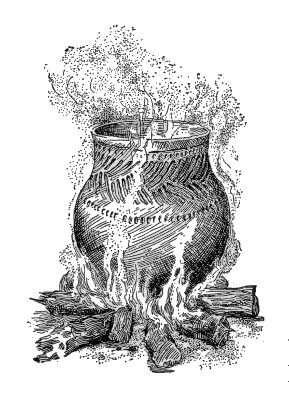

EARTHEN COOKING POT

EARTHEN COOKING POTGame.[31] 1. One of the pupils plays that he or she is an old Indian squaw. All the other pupils are her children. She stands before them and says: "Children, I must go to the river. I must see whether the warriors are catching many fish for supper. I want you all to stay here in the tepee and finish your work." In a little while the squaw returns from the river. She walks up and down the aisles and asks each of her [Pg 47] children this question: "Have you done your work?" Each one answers: "No, I have not done my work, but I think that John (pointing to the next pupil) has done his." The questions and answers go on until every pupil in the class has spoken. Then those who made no mistake in their answers join in an Indian dance. They march up and down the aisles, clapping their hands and chanting, "All good Indians have done their work."

2. The old Indian squaw again leaves and again returns to her children. This time she asks each one, "What were you doing while I was gone?" Each one answers, "I did the work you gave me to do." All those who answer correctly join in an Indian dance, singing, "I did my work yesterday, and I have done my work to-day." [32]

PETER AND THE STRANGE LITTLE OLD MAN[9]

On the edge of a great forest there once lived a toymaker and his little family. Although he worked hard, he was very poor. His wife had to help him whittle and paint the toys, which he sent to the nearest village to be sold.

"Times are hard," the toymaker said one night to his wife, "I cannot save any money. Christmas is near at hand, and I am afraid we shall have no presents for the boys."

They had two boys. These looked as like as two peas from the same pod, but they were very unlike at heart. Peter, the younger one, made his father and mother very happy. Joseph, the elder, caused them much worry.

The toymaker would say: "Put wood on the fire, boys. We cannot work if we are not warm." Peter would go to the shed at once, bring in an armful of wood, put some of it in the stove and the rest in the woodbox. All the while Joseph would stay in the warm room and would not lift a finger to help him.

So it was with everything. Peter worked steadily at his father's side most of the day, whittling and gluing and painting toys, while Joseph slipped away and spent his time in idleness and play. In the evening it was Peter who helped his mother dry the dishes.

One day as the three workers were busily bent over the bench, a knock was heard at the door. They were surprised to see standing outside a strange little old man, no higher than the tabletop.

"Excuse me," he said, lifting his red cap very politely. "I have lost my way. Would one of the boys kindly be my guide through the woods?"

"Yes, of course," answered the toymaker. He looked from one of his sons to the other, wondering which one to send. He hoped that Joseph [Pg 49] would offer to go, because he was the elder. But Joseph was already shaking his head very hard and turning away. Peter caught his father's look and put on his hat and coat.

"I know all the paths," he said to the stranger, "and will help you find your way."

They started off at once. When they had gone a short distance, it began to snow. They trudged along just the same until the ground was covered with a thick white blanket as far as they could see. They talked very little, but kept their eyes open for the way, and hurried along. At last they reached a place where four great oak trees stood in a row, as if some one had planted them so.

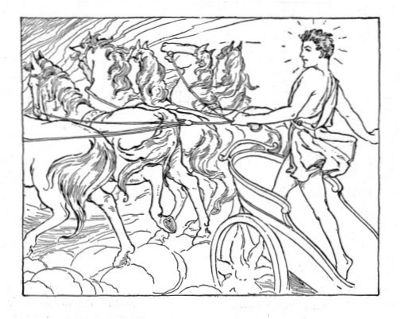

"This is the place," said the little old man. He took a golden whistle from his pocket and blew it. A low sweet tone came from it, that sounded like pleasant music in the silent woods. In a moment a large sleigh, drawn by eight prancing reindeer, appeared before them. The little old man motioned Peter to follow him and jumped in. As soon as Peter had jumped in too, they drove away as fast as they could go, bells ringing, and sparks flying as the reindeer's hoofs struck the ground. Now and then the strange little old man spoke to the reindeer. They seemed to know his voice. He called each by name, "Now, Dasher," and "Now, Dancer," [Pg 50] and "Get up, Prancer." Then they dashed and danced and pranced faster than ever.

They had been moving over the ground in this way for more than an hour. Then Peter saw in the distance a building that was longer and wider and higher than any building he had ever seen or heard about. As they got nearer, a steady buzzing sound was heard. Peter thought it was the sound of machinery. He thought a thousand wheels must be turning and humming within. As he looked and listened, the sleigh suddenly came to a stop. They stood at the entrance to the mighty building.

"What is this building?" asked Peter.

"This is my workshop," said the strange little old man, as he jumped out of the sleigh. "Some day I shall take you inside. You are the kind of boy I like. I know how you help your father and mother. To-day you have helped me. Here is a little present to take home with you."

He placed something in Peter's hand. Then he hurried up the broad stairs and into the workshop. The big door slammed shut behind him, and at that very moment the sleigh, the reindeer, and the workshop itself suddenly disappeared. Much to his surprise Peter found himself alone in the woods and not far from his father's hut.

He wondered whether he had only dreamed all that had happened. No, that could not be, for he [Pg 51] still held in his hand a small leather bag, the present from the little man. Holding this tightly, he hurried to his home.

You may imagine the surprise of his parents and his brother when he told his story. They asked him to tell it again and again. Each one examined the small leather bag. There were two beautiful gold coins in it. Peter gave these to his father and mother.

His father patted him on his curly head.

"We shall spend these for Christmas," he said.

Oral Exercise. 1. Which part of this story do you like best? Tell your classmates what sort of picture you would make with colored crayons for this part of the story. Explain exactly what will be in the picture. Then make the picture.

2. Why did the strange little old man help Peter? Do you know any story in which a fairy helps good people?

3. Think of the fairy stories that you have heard or read. What is the name of the one you like best? Would it not be fun for each pupil to tell the class his favorite fairy story? When you tell yours, do not let it be too long. Tell only the important parts of it.[22]

Group Exercise. After each story, you and your classmates should tell the speaker what you liked in his story and in his telling of it. Then tell what you did not like.

Oral Exercise. 1. Tell your classmates how you think fairies look. How tall do you think they are? What kind of clothes do they wear? After you have answered these questions, draw on the board or on paper, with colored chalks or crayons, a picture of a fairy.

2. Do fairies always walk or run, or can they fly, or have they tiny horses and wagons?

3. Can you see the picture of the fairies in the following lines? What do those lines tell you about fairies that you did not know before?

4. Where do you think the fairies live? What do they eat? The following poem gives one answer to these questions, and tells us still more about fairies. What is the name of the poem? The child that sings it is afraid of fairies. Do you know any other children that are afraid of them?

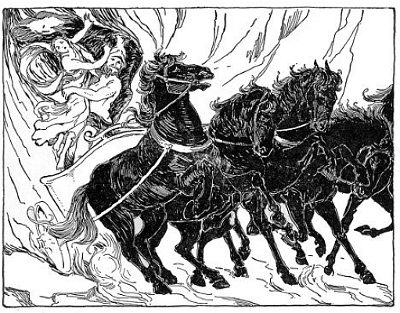

"AND RIDING ON THE CRIMSON MOTHS"

"AND RIDING ON THE CRIMSON MOTHS"A CHILD'S SONG

Oral Exercise. 1. Let us make sure that we understand every line of this pretty poem or song. In the first line, why is the mountain called airy? A rushy glen is a narrow valley in which many rushes or swamp reeds grow. Have you ever seen such a place? Draw a picture of a rushy glen.

2. Which lines in the first part of the poem tell about fairies? These fairies go in a troop or band or company. Which line tells us that? With colored crayons draw a picture of a fairy wearing a green jacket, a red cap, and a white owl's feather.

3. The second part, or stanza, of the poem tells where some of these fairies live. What do some of them do all the night? As they watch, who keeps them company?

4. When you read this poem, does it seem to be a song? Do you like the way it reads? Which part do you like best? Draw with colored crayons a picture for this part. Before you draw, explain how the picture looks in your mind. Perhaps you will draw a picture of a troop of fairies, or of a fairy in the reeds with fairy watchdogs near by.

Memory Exercise. Which do you like better, this poem you have just studied or the part of another poem about fairies that is printed before this? Read aloud, several times, the one you like better, until you can say it without once looking at the book.

PETER VISITS THE STRANGE LITTLE OLD MAN'S WORKSHOP

Over a week had passed since Peter's ride in the strange little old man's sleigh, but the little man had not come again. Peter was beginning to fear that he might never return. One afternoon, however, just as the early winter twilight began to darken the great forest, the jingling of sleighbells was heard in front of the toymaker's hut.

"Whoa, Dasher! Steady, Dancer! Whoa, Prancer!" was what Peter heard as he pressed his face against the windowpane. Yes, there were the reindeer, and there, bundled up to his chin in furs, was the strange little old man. He saw Peter at once and made signs to the boy to come along with him. Peter could not put on his cap and coat fast enough. In less than a minute he had climbed into the sleigh, tucked himself in snugly, and was flying over the frozen, snow-covered ground by the side of his strange companion. Soon they had left the lighted hut far behind them and were making their way through the woods on an old logging road that Peter knew. After a while, however, they reached parts of the forest that Peter had never seen. Here grew trees whose names he [Pg 57] had never heard. Now and then he caught glimpses of animals that were unlike any of those with which he was familiar. Peter was so much interested in these that he hardly noticed the great building, the little man's workshop, until the sleigh had stopped before the main door of it. But then he forgot everything else. The big shop was brightly lighted in every story, and the steady hum of machinery filled the evening air.

"We're working overtime now," explained the little man. "You see, Christmas is near."

The humming grew louder and the lights seemed a great deal brighter, as they entered the building. Peter was much excited. When the inner doors were opened, and Peter stood in the great roaring workshop itself, he could hardly believe his eyes. Before him, in long rows, he saw a thousand pounding and buzzing machines, all running at full speed. Ten thousand workbenches stood in orderly rows beyond the machines. The unending room fairly swarmed with busy workmen, like a hive over-flowing with bees. And such workmen! Each wore a green coat and a red cap, decorated with a white owl's feather. Each was no higher than Peter's knee. They were fairies.

As he stood there, trying to understand it all, troop after troop of the fairies passed him.[Pg 58] They were pushing long, high baskets, that stood on wheels. Down the long room they rolled these and through a great double swinging door at the other end. These baskets were filled to the top with playthings. Some held dolls, some sleds, some drums. Others were full of various kinds of musical instruments. Still others gave forth the pleasantest smells. They contained cookies and ginger snaps and all sorts of Christmas goodies.

"Why, they are all Christmas things!" cried Peter in great surprise, turning to the strange little old man at his side. But the strange little [Pg 59] old man was gone, and Peter stood alone in the doorway of this wonderful Christmas workshop.

Before he could decide what to do, a group of little workmen called him by name, as pleasantly as if they had known him all his life.

"Peter, come and help us with this basket!"

"I will," answered Peter.

He was glad to join in the work. Hanging coat and cap on a near-by hook, he put his shoulder against one of the heavy baskets. Soon he had it rolling merrily down the long aisle. Past machines that sawed boards he pushed it, past planing wheels, past long rows of benches where the workers were hammering or gluing or painting, past wide ovens where the little bakers were busy over hundreds of pans of frosted gingerbread—on and on, down the great room he pushed it so fast that his wee comrades were almost left behind. As he passed machines and benches and ovens, the workmen looked up from their work an instant. They smiled at the newcomer.

"When you get through with that," shouted the workmen at the saws, "come and help us with these boards."

"All right, I will," said Peter as he moved along with his basket.

"When you get through with the sawing," cried the planers, "come and help us."

Peter smiled at them. "I will," he shouted back as loud as he could, so as to be heard above the noise of the machinery.

"When you finish planing," the painters called to him next, "come and help us."

"I will," Peter replied. "I like to paint, anyway."

Now he passed the bakers. They tossed him a cooky. "When you finish painting," they said, "perhaps you will come and help us."

"That I gladly will," answered Peter in his pleasantest tone. It was quieter here, and he did not need to shout.

At last he reached the double swinging door. Through this he had seen basket after basket disappear before him. Here was the storeroom. It was even larger than the workroom. The walls were lined with shelves, on which were placed the Christmas things. This was an interesting place, but Peter had no time to stay. He was eager to help at the machine saws, at the planing machines, at the workbenches, and in the bakeshop. So he hurried back to these. He did first one thing, then another, as he was needed. He was used to work and liked to help.

The fairies were careful workers and jolly comrades. Now and then they sang as they worked. Then the machines themselves, like the fingers and arms and legs of the workmen, seemed to move faster and the work to be easier.

Suddenly a loud but very pleasant whistle sounded through the mighty workshop. It was the signal for a recess. The machines stopped. The fairies laid down their tools and brushes. All was quiet for a time. Now another kind of fun began. The fairies started various games. They formed rings and danced round and round as they sang:

They played at guessing riddles. These were about toys.

"You see," whispered a fairy who explained everything to Peter, "when the snow comes, and Christmas is near, we leave our homes in the woods and spend our winters making toys for all the good children in the world. Sometimes we cannot make all the toys we need, but we do not wish a single child anywhere to be without a Christmas."

Peter soon learned that the fairies took pride in speaking correctly. Those who sometimes made mistakes played special games to help themselves get over bad speaking habits. At one place they stood like soldiers in a row and pronounced words that were printed on the board.

"Don't you sometimes wish for the woods and moonlight nights?" asked Peter.

He could not hear the answer. At a signal the machinery had started again. The fairies were hurrying back to their places. Peter took his place with the rest. He worked steadily at one job and another. The time flew by. Another whistle blew, and it was time to stop for the day. Then the strange little old man appeared.

"It's time for you to go back home," he said. "Should you like to be here always?"

"Oh, yes," answered Peter. "But I have pleasant work to do at home too."

The strange little old man took a ring from his pocket and held it up before the boy's eager face.

"You are the kind of boy I like," he said. "You are willing to help and work. Take this ring home with you. I give it to you. It is a magic ring. Wear it on Christmas Day. On that day wish any one thing you please. The ring will get it for you."

While he was talking they had walked to the main door of the building. Peter had put on his cap and coat. Now the door stood open, and they said good-bye. Peter walked slowly down the steps, staring at the magic ring on his finger. When he reached the last step, he turned and looked back. In the doorway stood the strange little old man, watching him. Peter thought he looked different. Yes, he seemed taller and [Pg 63] stouter than before. He seemed jollier. Peter glanced at the red cap, red coat, and leather leggings he wore. He noticed the laughing face, the twinkling eyes, rosy cheeks, and white beard.

"Can this be Santa Claus?" he thought.

Instantly the great workshop disappeared. Peter found himself, as before, not far from his father's house. His parents and brother caught sight of him as he came out of the forest, and they ran out to meet him. They listened in astonishment to what he told them he had seen. They could not admire enough the magic ring on his finger.

Oral Exercise.[34] 1. What interested you most as you read the story about Peter? What kind of picture should you make with colored crayons for the part of the story you liked best? Draw the picture after you have told your classmates about it.

2. Do you remember what kind of boy Peter's brother, Joseph, was? What do you think he would have done if he, instead of Peter, had been in that workshop? What might have happened to him?

3. Play the part of the story about Peter that tells of Peter and the fairies as they worked together in the great toyshop. Who shall be Peter? Who shall be the fairies at the saws? Who shall be the bakers? Who shall be the painters? What toys and things will you make?

4. Play the same part of the story but as it would have happened if Joseph had been there instead of Peter.

5. Make believe that, as you awoke one Saturday morning, you found a letter on your pillow. When you read it, you learned that it was from a fairy. This fairy invited you to meet him at the old tree near the school-house. When you met him there, you and he went off into the woods. Tell your classmates what happened. It may be that your story will be somewhat like that of Peter. Still, you may have seen and heard and done things that were very different.

You remember that during the recess in Santa Claus's workshop some of the fairies made riddles. Peter said that these were about toys. Here are two they might have made:

It has two arms, two legs, and a head, like a human being, but it cannot walk or work or talk. What is it?

I spend most of my life in a little wooden box. I press against its cover day and night. I want to get out. Oh, how I leap when some one opens the box! Oh, how frightened little girls and boys look when they first see me! What am I?

Oral Exercise. 1. Of course you have guessed the first of these two riddles. But can you guess the second one?

2. Make riddles for your classmates to guess, about toys and other things that are suitable for Christmas presents.

A schoolgirl once made this riddle:

It makes beautiful colors. Children like it. What is it?

The answer is, a box of crayons.

Oral Exercise. Do you think this riddle can be made better? Is anything important left out? Is it bright enough? Try to make a better riddle about the box of crayons.

A schoolmate changed the riddle of the box of crayons. He thought this was better:

We are twelve little men in a little tight box. Each one of us writes his name in a different color. What are we?

Oral Exercise. Which of the two riddles do you like better? Can you tell why? Does the first riddle say anything about the box? Does it tell that anything is in a box?

Three other schoolmates made up other riddles about the box of crayons. Here they are:

We are a band of fairies living in our cozy little home. Each of us wears in his cap a feather of a different color. What are we?

I am a piece of the rainbow caught and put in a little tight jail. A little schoolgirl uses parts of me when she draws pictures. What am I?

We are a company of soldiers. Each of us wears a cap of a different color. We spend most of our time in a small pasteboard fort. When we go out, we are sure to make our mark. What are we?

Oral Exercise. 1. Of all the riddles of the box of crayons, which do you think is the best? Which is the second best? Which is the poorest?

2. Now again make riddles about toys and Christmas presents. But you should now be able to make better ones than you did before.

Group Exercise. 1. The class, after a riddle has been guessed, should point out what is good in it and then should tell how it might be made better. Should it be made shorter? Should it be made longer? How could it be made brighter?

2. The best riddles should be repeated slowly, so that the teacher may write them on the board. Now these may be read over, and the class may try to make each one better.[20] The teacher will rewrite each in its improved form.[35]

Written Exercise. 1. Copy the riddle that the class likes best. As you copy, notice the spelling of the words, the capital letter at the beginning of each sentence, and the mark at the end of each sentence. This careful copying will prepare you for the next exercise.

2. Write from dictation the riddle that you have copied. Then correct any mistakes.[36] These questions will help you to find out whether you have made any:

1. Is every word spelled correctly?

2. Does every sentence begin with a capital letter?

3. Is every sentence followed by the right kind of punctuation mark?

You read in the story of Peter's visit to Santa Claus's workshop that the fairy workers sometimes sang while they worked. At recess too they had songs. One of these you will probably enjoy very much. As you read it you can see the fairies dancing in a ring in the moonlight.

THE LIGHT-HEARTED FAIRY

Would it not be pleasant to dance in a ring with your classmates? You might play that you are all fairies, and you might say this poem while you dance. Each pupil could make a red cap of paper. He might stick a white owl's or a white chicken's feather in it as fairies do. He could wear it while reciting the poem. But, first of all, you must make sure that you understand every line of the song, else you cannot say it well.

Oral Exercise.[37] 1. What do you like about this poem? Have you noticed that the fairy is called light-hearted in the first stanza of the poem, but light-headed in the second and light-footed in the third?

2. What do fairies drink? The second stanza tells. They find this delicious sweet drink in the cups of flowers.

3. As you know, fairies are rarely, if ever, seen in the daytime. The night is their day, when they dance and sing and do good deeds. What is meant in the poem by the line, The night is his noon? What is the fairies' sunlight?

Memory Exercise. 1. Read this poem aloud a number of times. You will not have to read it often before you will be able to say it without the book. When you know it, recite it to the class as well as you can. Wear your red cap and think of the merry, airy, light-hearted fairy as you recite it. That will help you to say it in a lively way.[Pg 70]

2. Perhaps the teacher will permit the five or six pupils who have recited best to form a ring in front of the class and dance round and round as they recite the poem. Then the class may point out what might have been done better. Perhaps other bands of fairies will recite, each trying to recite best.

The story about Peter does not tell us the words with which some of the fairies had trouble. If some fairies are like some pupils, then they need to learn how to use the words rang, sang, and drank correctly.

Oral Exercise. 1. As you read the following sentences, notice that rang, sang, and drank are not used with have or has or had. Are rung, sung, and drunk used with have or has or had?

1. I rang the bell for the teacher.

2. Have you ever rung it?

3. I sang the Christmas song.

4. Have you ever sung it?

5. I drank the grape juice.

6. Have you ever drunk apple juice?

7. The fairies danced and sang, and drank nectar.

8. They had rung the bell.

9. They had sung that song before.

10. He has never drunk nectar.

2. Which of the six words that you have been studying in this lesson are used with have or has or had? Which are not used with them? Make these two lists. Would it be right to make the following rule?

Never use rang or sang or drank with have or has or had.

3. Using what you have just learned, fill the blanks in the following sentences with the right words, rang or rung, sang or sung, drank or drunk:

1. The strange little old man had already —— his morning coffee.

2. He —— an old song that he had —— many times before.

3. When he had —— a silver bell, a troop of fairies appeared.

4. Peter is not a fairy. He has never —— nectar.

5. But he has often —— the song he heard the fairies sing.

6. He has never —— a silver bell.

7. Have you ever —— the school bell?

8. Have you ever —— spring water?

Game. Let the girls of the class, working together in a group, write on the board six sentences in which rang, sang, and drank are used correctly. Let the boys in the same way write six sentences in which rung, sung, and drunk are used correctly. The boys will correct the girls' sentences, and the girls the boys'. The teacher will decide whether the boys or the girls made fewer mistakes, and which group wrote the more interesting sentences. Then all the sentences may be read aloud by several groups of pupils in turn, each trying to read the most clearly.

The magic ring that Santa Claus gave Peter would bring him any one thing that he might wish. When Christmas morning came, he had only to say his wish, and it would be fulfilled.[38]

Oral Exercise. 1. Suppose that you had such a magic ring. What would be your one big wish? It will be fun to see whether you and your classmates have the same wish.

2. What do you think Peter himself wished when Christmas morning came? What happened then? Tell your classmates the story of Peter's wish on Christmas Day, exactly as you think everything happened.

Group Exercise. One or two of the best stories about Peter's wish should be told a second time. This time the teacher will write them on the board. Now you and the other pupils should read them carefully to see where they can be made better.[20] These questions may help in this work:

1. Can better words be used for some of those in the story?

2. Should some of the and's be left out?

3. Can anything be added to make the story interesting?

Written Exercise. Silently read one of the improved stories, perhaps more than once, noticing the spelling of the words, the capital letter at the beginning of each [Pg 73] sentence, and the mark at the end of each sentence. Write it from dictation. Then compare your paper with what is written on the board, and correct any mistakes you may have made.

Oral Exercise. Suppose that Peter lost the magic ring before Christmas came. Who might have found it? What might have happened then? Make up a story to tell this. You might call it "The Lost Magic Ring." Try to make up a fairy story that your classmates will be very glad to hear. Try to think of some wonderful happenings for it. Perhaps the following ideas will help you to begin your story: