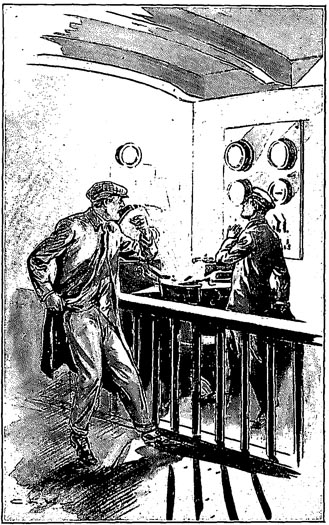

There was a sudden blinding flash from the instruments and

a blaze of blue, hissing fire filled the room.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Ocean Wireless Boys and the Lost Liner, by Wilbur Lawton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Ocean Wireless Boys and the Lost Liner Author: Wilbur Lawton Illustrator: Charles Wrenn Release Date: November 2, 2012 [EBook #41265] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OCEAN WIRELESS BOYS AND LOST LINER *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

There was a sudden blinding flash from the instruments and

a blaze of blue, hissing fire filled the room.

THE OCEAN WIRELESS BOYS

AND THE LOST LINER

BY

CAPTAIN WILBUR LAWTON

AUTHOR OF “THE BOY AVIATORS’ SERIES,”

“THE DREADNOUGHT BOYS’ SERIES,”

“THE OCEAN WIRELESS BOYS ON THE ATLANTIC,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY CHARLES L. WRENN

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1914,

BY HURST & COMPANY

CONTENTS

The West Indian liner, Tropic Queen, one of the great vessels owned by the big shipping combine at whose head was Jacob Jukes, the New York millionaire, was plunging southward through a rolling green sea about two hundred miles to the east of Hatteras. It was evening and the bugle had just sounded for dinner.

The decks were, therefore, deserted; the long rows of lounging chairs were vacant, while the passengers, many of them tourists on pleasure bent, were below in the dining saloon appeasing the keen appetites engendered by the brisk wind that was blowing off shore.

In a small steel structure perched high on the boat deck, between the two funnels of the Tropic Queen, sat a bright-faced lad reading intently a text-book on Wireless Telegraphy. Although not much more than a schoolboy, he was assistant wireless man of the Queen. His name was Sam Smalley, and he had obtained his position on the ship—the crack vessel of the West Indies and Panama line—through his chum, Jack Ready, head operator of the craft.

To readers of the first volume of this series, “The Ocean Wireless Boys on the Atlantic,” Jack Ready needs no introduction.

Here he comes into the wireless room where his assistant sits reading in front of the gleaming instruments and great coherers. Jack has been off watch, lying down and taking a nap in the small sleeping cabin that, equipped with two berths, opens off the wireless room proper, thus dividing the steel structure into two parts.

“Hello, chief,” said Sam Smalley, with a laugh, as Jack appeared; “glad you’re going to give me a chance to get to dinner at last. I’m so hungry I could eat a coherer.”

“Skip along then,” grinned Jack; “but it’s nothing unusual for you to be hungry. I’ll hold down the job till you get through, but leave something for me.”

“I’ll try to,” chuckled Sam, as he hurried down the steep flight of steps leading from the wireless station up on the boat deck to the main saloon.

“Well, this is certainly a different berth from the one I had on the old Ajax,” mused Jack, as he looked about him at the well-equipped wireless room; “still, somehow, I like to look back at those days. But yet this is a long step ahead for me. Chief wireless operator of the Tropic Queen! Lucky for me that the uncle of the fellow who held down the job before me left him all that money. Otherwise I might have been booked for another cruise on the Ajax, although Mr. Jukes promised to give me as rapid promotion as he could.”

Readers of the first volume, dealing with Jack Ready and his friends, will recall how he lived in a queer, floating home with his uncle, Cap’n Toby. They will also recollect that Jack, who had studied wireless day and night, was coming home late one afternoon, despondent from a fruitless hunt for a job, when he was enabled to save the little daughter of Mr. Jukes from drowning. The millionaire’s gratitude was deep, and Jack could have had anything he wanted from him.

All he asked, though, was a chance to demonstrate his ability as a wireless man on the Ajax, a big oil tanker which had just been equipped with such an outfit. He got the job, and then followed many stirring adventures. He took part in a great rescue at sea, and was able to frustrate the schemes of some tobacco smugglers who formed part of the crew of the “tanker.” This task, however, exposed him to grave danger and almost resulted in his death.

At sea once more, after the smugglers had been apprehended and locked up, Jack’s keen wireless sense enabled him to solve a problem in surgery. The Ajax carried no doctor, and when one of the men in the fireroom was injured, and it appeared that a limb would have to be amputated, a serious question confronted the captain, who, like most of his class, possessed a little knowledge of surgery, but not enough to perform an operation that required so much skill.

The injured man was a chum of Jack’s, and he did not want to see him lose a limb if it could be helped, or have his life imperiled by unskillful methods. Yet what was he to do? Finally an idea struck him. He knew that the big passenger liners all carried doctors. He raised one by means of the wireless and explained the case. The injured man was carried into the wireless cabin and laid close to the table. Then, while the liner’s doctor flung instructions through space, Jack translated them to the captain. The result was that the man was soon out of danger, but Jack kept in touch with doctors of other liners till everything was all right beyond the shadow of a doubt.

This feat gained him no little commendation from his captain and the owners. Next he was instrumental in saving Mr. Jukes’ yacht which was on fire at sea. In the panic Mr. Jukes’ son Tom, who was the apple of the ship-owning millionaire’s eye, was lost. By means of wireless, Jack located him and reunited father and son.

His promotion was the result, when the regular operator of the Tropic Queen went west to receive a big legacy left him. As the services of the retiring operator’s assistant had been unsatisfactory, Jack was asked to find a successor to him. He selected an old school chum, Sam Smalley, who had owned and operated a small station in Brooklyn and was an expert in theory and practice. The ship had now been at sea two days, and Sam had shown that he was quite capable of the duties of his new job.

An old quartermaster passed the door of the wireless cabin. He poked his head in.

“Goot efenings, Yack,” he said, with easy familiarity. “How iss der birdt cage vurking?”

This was Quartermaster Schultz’s term for the tenuous aërials swung far aloft to catch wide-flung, whispered space messages and relay them to the operator’s listening ears.

“The bird cage is all right,” laughed Jack. “Dandy weather, eh?”

The old man, weather-beaten and bronzed by the storms and burning suns of the seven seas, shook his head.

“Idt is nice now, all righdt,” he said, “but you ought to see der glass.”

“The barometer? What is the matter with it?”

“Py gollys, I dink der bottom drop oudt off idt. You may have vurk aheadt of you to-night.”

“You mean that we are in for a big storm?”

“I sure do dot same. Undt ven it comes idt be a lollerpaloozitz. Take my vurd for dat. Hark!”

The old quartermaster held up a finger.

Far above him in the aërials could be heard a sound like the moaning bass string of a violin as the wind swept among the copper wires.

“Dot’s der langwitch of Davy Chones,” declared Schultz. “Idt says, ‘Look oudt. Someding didding.’ I’fe heardt idt pefore, undt I know.”

The old man hurried off on his way forward, and Jack emitted a long whistle.

“My, won’t there be a lot of seasick passengers aboard to-night! The company will save money on breakfast to-morrow.”

Just then Sam came back from dinner and Jack was free to go below to his meal. He was about to relinquish the instruments when there came a sudden call.

“To all ships within three hundred miles of Hatteras: Watch out for storm of hurricane violence.

“Briggs, Operator Neptune Beach U. S. Wireless Service.”

Sam was looking over Jack’s shoulder as the young wireless chief of the Tropic Queen rapidly transcribed the message on a blank.

“Phew! Trouble on the way, eh?” he asked.

“Looks like it. But we need not worry, with a craft like this under our feet.”

But Sam looked apprehensive.

“What is the trouble? Not scared, are you?” asked Jack, who knew that, excellent operator though he had shown himself to be, this was Sam’s first deep-sea voyage.

“N-no. Not that,” hesitated Sam, “but seasickness, you know. And I ate an awful big dinner.”

“Well, don’t bother about that now. Lots of fellows who have never been to sea before don’t get sick.”

“I hope that will be my case,” Sam replied, without much assurance in his voice.

“Here, take this to the captain; hurry it along now,” said Jack, handing him the dispatch. “I guess he’ll be interested. Wait a minute,” he added suddenly. “There’s the Tennyson of the Lamport & Holt line talking to the Dorothea of the United Fruit, and the battleship Iowa is cutting in. All talking weather.”

It was true. From ship to ship, borne on soundless waves, the news was being eagerly discussed.

“Big storm on the way,” announced the Tennyson.

“We should worry,” came flippantly through the ether from the Dorothea.

“You little fellows better take in your sky-sails and furl your funnels; you’ll be blown about like chicken feathers in a gale of wind,” came majestically from Uncle Sam’s big warship.

Then the air was filled with a clamor for more news from the Neptune Beach operator.

“You fellows give me a pain,” he flashed out, depressing and releasing his key snappily. “I’ve sent out all I can. Don’t you think I know my job?”

“Let us know at once when you get anything more,” came commandingly from the battleship.

“Oh, you Iowa, boss of the job, aren’t you?” remarked the flippant Dorothea.

“M-M-M!” (laughter) in the wireless man’s code came from all the others, Jack included. The air was vibrant with silent chuckles.

“Say, you fellows, what is going on?” came a fresh voice. Oh, yes, every wireless operator has a “voice.” No two men in the world send alike.

“Hello, who are you?” snapped out Neptune Beach.

“British King, of the King Line, Liverpool for Philadelphia. Let us in on this, will you? What you got?”

“Big storm. Affect all vessels within three hundred miles of Hatteras. This is Neptune Beach.”

“Thanks, old chap. Won’t bother us, don’t you know,” came back from the British King, whose operator was English. “Kind regards to you fellows. Hope you don’t get too jolly well bunged up if it hits you.”

“Thanks, Johnny Bull,” from the Dorothea. “I reckon we can stand anything your old steam tea-kettle can.”

The wireless chat ceased. Sam hastened forward to the sacred precincts of the captain’s cabin, while Jack went below to his belated dinner. As he went he noticed that the sea was beginning to heave as the dusk settled down, and the ship was plunging heavily. The wind, too, was rising. The social hall was brilliantly lighted. From within came strains of music from the ship’s orchestra. Through the ports, as he passed along to the saloon companionway, Jack could see men and women in evening clothes, and could catch snatches of gay conversation and laughter.

“Humph,” he thought, “if you’d just heard what I have, a whole lot of you would be getting the doctor to fix you up seasick remedies.”

In the meantime Sam, cap in hand, presented the message to the captain. The great man took it and read it attentively.

“This isn’t a surprise to me,” said Captain McDonald, “the glass has been falling since mid-afternoon. Stand by your instruments, lad, and let me know everything of importance that you catch.”

“Very well, sir.” Sam, who stood in great awe of the captain, touched his cap and hastened back. He adjusted his “ear muffs,” but could catch no floating message. The air was silent. He sent a call for Neptune Beach, but the operator there told him indignantly not to plague him with questions.

“I’ll send out anything new when I get it,” he said. “Gimme a chance to eat. I’m no weather prophet, anyhow. I only relay reports from the government sharps, and they’re wrong half the time. Crack!”

Sam could sense the big spark that crashed across the instruments at Neptune Beach as the indignant and hungry operator there, harassed by half a dozen ships for more news, smashed down his sending key.

When Jack came on deck again, he thought to himself that it was entirely likely that the warning sent through space from Neptune Beach would be verified to the full by midnight. The merriment in the saloon appeared to be much subdued. The crowd had thinned out perceptibly and hardly anybody was dancing.

The ship was rolling and plunging like a porpoise in great swells that ran alongside like mountains of green water. Although it was dark by this time, the gleam of the lights from the brilliantly illuminated decks and saloon showed the white tops of the billows racing by.

Just as Jack passed the door leading from the social hall to the deck, a masculine figure emerged. At the same instant, with a shuddering, sidelong motion, the Tropic Queen slid down the side of a big sea. The man who had just come on deck lost his balance and went staggering toward the rail. The young wireless man caught and steadied him.

In the light that streamed from the door that the man had neglected to close, Jack saw that he was a thickset personage of about forty, black-haired and blue-chinned, with an aggressive cast of countenance.

“What the dickens——” he began angrily, and then broke off short.

“Oh! It’s you, is it? The wireless man?”

“The same,” assented Jack.

“Well, this is luck. I was on my way up to your station. On the boat deck, I believe it is. This will save me trouble.”

The man’s manner was patronizing and offensive. Jack felt his pride bridling, but fought the feeling back.

“What can I do for you, Mr.—Mr.——”

“Jarrold’s the name; James Jarrold of New York. Have you had any messages from a yacht—the Endymion—for me?”

“Why, no, Mr. Jarrold,” replied Jack wonderingly. “Is she anywhere about these waters?”

“If she isn’t, she ought to be. How late do you stay on watch?”

“Till midnight. Then my assistant relieves me till eight bells of the morning watch.”

Mr. Jarrold suddenly changed the subject as they stood at the rail on the plunging, heaving deck. Somebody had closed the door that he had left open in his abrupt exit, and Jack could not see his face.

“We’re going to have bad weather to-night?” he asked.

“So it appears. A warning has been sent out to that effect, and the sea is getting up every moment.”

Mr. Jarrold of New York made a surprising answer to this bit of information.

“So much the better,” he half muttered. “You are, of course, on duty every second till midnight?”

“Yes, I’m on the job till my assistant relieves me,” responded the young wireless chief of the Tropic Queen.

“Do you want to make some money?”

“Well, that all depends,” began Jack doubtfully. “You see, I——”

He paused for words. He didn’t want to offend this man Jarrold, who, after all, was a first-cabin passenger, while he was only a wireless operator. Yet somehow the man’s manner had conveyed to Jack’s mind that there was something in his proposal that implied dishonesty to his employers. Except vaguely, however, he could not have explained why he felt that way. He only knew that it was so.

Jarrold appeared to read his thoughts.

“You think that I am asking you to undertake something outside your line of duty?”

“Why, yes. I—must confess I don’t quite understand.”

“Then I shall try to make myself clear.”

“That will be good of you.”

The man’s next words almost took Jack off his feet.

“When you hear from the Endymion, let me know at once. That is all I ask you.”

“Then you are expecting to hear from the yacht to-night?” asked Jack wonderingly. It was an unfathomable puzzle to him that this somewhat sinister-looking passenger should have so accurate a knowledge of the yacht’s whereabouts; providing, of course, that he was as certain as he seemed.

“I am expecting to hear from her to-night. Should have heard before, in fact,” was the brief rejoinder.

“There are friends of yours on board?” asked Jack.

“Never mind that. If you do as I say—notify me the instant you get word from her, you will be no loser by it.”

“Very well, then,” rejoined Jack. “I’ll see that you get first word after the captain.”

Jarrold took a step forward and thrust his face close to the boy’s.

“The captain must not know of it till I say so. That is the condition of the reward I’ll give you for obeying my instructions. When you bring me word that the Endymion is calling the Tropic Queen, I shall probably have some messages to send before the captain of this ship is aroused and blocks the wire with inquiries.”

“What sort of messages?” asked Jack, his curiosity aroused to the utmost. He was now almost sure that his first impression that Jarrold was playing some game far beyond the young operator’s ken was correct.

Jarrold tapped him on the shoulder in a familiar way.

“Let’s understand each other,” he said. “I know you wireless men don’t get any too big money. Well, there’s big coin for you to-night if you do what I say when the Endymion calls. I want to talk to her before anyone else has a chance. As I said, I want to send her some messages.”

“And as I said, what sort of messages?” said Jack, drawing away.

“Cipher messages,” was the reply, as Jarrold glanced cautiously around over his shoulder.

The door behind them had opened and a stout, middle-aged man of military bearing had emerged. He had a gray mustache and iron-gray hair, and wore a loose tweed coat suitable for the night. Jack recognized him as a Colonel Minturn, who had been pointed out to him as a celebrity the day the ship sailed. Colonel Minturn, it was reported, was at the head of the military branch of the government attending to the fortifications of the Panama Canal. The colonel, with a firm stride, despite the heavy pitching of the Tropic Queen, walked toward the bow, puffing at a fragrant cigar.

When Jack turned again to look for Jarrold, he had gone.

But the young wireless boy had no time right then to waste in speculation over the man’s strange conduct. It was his duty to relieve Sam, who would not come on watch again till midnight.

As he mounted the steep ladder leading to the “Wireless Hutch,” he could feel the ship leaping and rolling under his feet like a live thing. Every now and then a mighty sea would crash against the bow and shake the stout steel fabric of the Tropic Queen from stem to stern.

The wind, too, was shrieking and screaming through the rigging and up among the aërials. Jack involuntarily glanced upward, although it was too dark to see the antennæ swaying far aloft between the masts.

“I hope to goodness they hold,” he caught himself thinking, and then recalled that, in the hurry of departure from New York, he had not had a chance to go aloft and examine the insulation or the security of their fastenings himself.

In the wireless room he found Sam with the “helmet” on his head. The boy was plainly making a struggle to stick it out bravely, but his face was pale.

“Anything come in?” asked Jack.

“Not a thing.”

“Caught anything at all from any other ship?”

Sam’s answer was to tug the helmet hastily from his head. He hurriedly handed it to Jack, and then bolted out of the place without a word.

“Poor old Sam,” grinned Jack, as he sat down at the instruments and adjusted the helmet that Sam had just discarded; “he’s got his, all right, and he’ll get it worse before morning.”

Sam came back after a while. He was deathly pale and threw himself down on his bunk in the inner room with a groan. He refused to let Jack send for a steward.

“Just leave me alone,” he moaned. “Oh-h, I wish I’d stayed home in Brooklyn! Do you think I’m going to die, Jack?”

“Not this trip, son,” laughed Jack. “Why, to-morrow you will feel like a two-year-old.”

“Yes, I will—not,” sputtered the invalid. “Gracious, I wish the ship would sink!”

After a while Sam sank into a sort of doze, and Jack, helmet on head and book in hand, sat at the instruments, keeping his vigil through the long night hours, while the storm shrieked and rioted about the ship.

The boy had been through too much rough weather on the Ajax to pay much attention to the storm. But as it increased in violence, it attracted even his attention. Every now and then a big sea would hit the ship with a thundering buffet that sent the spray flying as high as the loftily perched wireless station.

The wind, too, was blowing as if it meant to blow the ship out of the water. Every now and then there would come a lambent flash of lightning.

“It’s a Hatteras hummer for sure,” mused the boy.

The night wore on till the clock hands above the instruments pointed to twelve.

Above the howling and raging of the storm Jack could hear the big ship’s bell ring out the hour, and then, faint and indistinct, came the cry of the bow watch, “All’s well.” It was echoed boomingly from the bridge in the deep voice of the officer who had the watch.

“Well, nothing doing on that Endymion yet,” pondered Jack.

He fell to musing on Jarrold’s strange conduct. Why had the man suddenly vanished when Colonel Minturn appeared? What was his object in the strange proposal he had made to the young wireless man? What manner of craft was this Endymion, and how was it possible that she could live in such a sea and storm?

These, and a hundred other questions came crowding into his dozing brain. They performed a sort of mental pin-wheel, revolving over and over again without the lad’s arriving at any conclusion.

That some link existed between Jarrold and the Endymion was, of course, plain. But just why he should have vanished so quickly when the Panama official appeared, was not equally evident. Jack had a passenger list in front of him, stuck in the frame designed for it.

He ran his eyes over it. Yes, there was the name:

Mr. James Jarrold, N. Y.—Stateroom 44.

Miss Jessica Jarrold, N. Y.—Stateroom 56.

Suddenly Jack’s roving glance caught the name of Colonel Minturn, U. S. A., stateroom 46. So the colonel’s stateroom adjoined that of the man who appeared to be so anxious to avoid him! Another thing that Jack noted was that, although the ship was crowded and a stateroom for a single passenger called for a substantial extra payment, both Mr. Jarrold and the army man had exclusive quarters. In the case of Colonel Minturn this was, of course, understandable, but Jarrold? Jack looked at the latter’s name again, and now he noticed something else that had escaped him before.

Stateroom 44, the room occupied by Jarrold and adjoining Colonel Minturn’s, had evidently been changed at the last moment, for originally, as a crossed-out entry showed, Jarrold had been given stateroom 53. A pen line had been drawn through this entry by the purser evidently, when Jarrold had changed his room.

Jack happened to know that Colonel Minturn had come on board at the last moment, so, then, Jarrold had changed his stateroom only when he had found out definitely that Colonel Minturn’s room was No. 46. There must be something more than a mere coincidence in this, thought Jack, but, puzzle as he would, he could not arrive at what it meant.

He was still trying to piece it all out when suddenly the door, which he had closed to bar out the flying spray, was flung open.

A gust of wind and a flurry of spume entered, striking him in the face like a cold plunge.

“Bother that catch,” exclaimed Jack, swinging round; “I’ll have to get the carpenter to fix it to-morrow, I——”

But it was not a weakened catch that had given way. The door had been opened by the hand of a man, who, enveloped in a raincoat and topped by a golf cap, now stood in the doorway.

The man was James Jarrold.

Jack sprang to his feet, but the other held out a withholding hand.

“Stay right where you are, Mr. Ready,” he said. “I couldn’t sleep and I decided to sit out your watch up here with you. You’ve no objection?”

“I’m sorry,” said Jack, for after all Jarrold was a passenger and it would not do to offend him if he could help it, “but it is against the rules for passengers to linger about the wireless room.”

“Well, I can write a message, then. You have no objection to that?”

Jack was in a quandary. He knew perfectly well that Jarrold was there for some purpose of his own, but what it was—except that its aim was sinister—he could not hazard a conjecture.

“Of course the office is always open for business,” he rejoined, pushing a stack of sending blanks toward Jarrold.

“Of course,” replied Jarrold, sinking into a chair beside the young operator. “By the way, nothing from the Endymion yet?”

“That is the business of the line so far, sir,” replied Jack. “If it is anything of general interest, you will find the notice posted on the bulletin board at the head of the saloon stairs in the morning.”

Jarrold made no reply to this, but sat absent-mindedly tapping his gleaming white teeth with a gold-cased pencil as if considering what he should write on the blank paper before him. He appeared to be in no hurry to begin, but fumbling for his cigar case, produced a big black weed and leisurely lighted it, puffing out the heavy smoke with an abstracted air.

“Sorry, sir,” struck in Jack sharply, “but you can’t smoke in here, sir.”

“Why not?”

“It is against the rules.”

“Where do you see such a rule? Reckon you made it, eh? Too much of a molly-coddle to smoke, hey?”

The man’s tone was aggressive, offensive. The subtle objection to him that Jack had felt when they first met was growing with every minute. But he kept his temper. It was with an effort, however.

“There are the rules on the wall,” he said.

“Humph,” said Jarrold, with a disgusted grunt. “In that case I’ll throw my cigar away. But one always helps me to think.”

“Personally, I’ve always heard that tobacco dulls the brain,” retorted Jack, “but never having tried it, and not wanting to, I don’t know how true it is.”

Jarrold made no reply to this, but a contemptuous snort. He unfolded his big, loose-knit frame from the chair and went toward the door. He flung the cigar into the night. As he did so, there was a blinding flash of lightning. The rain was coming in torrents now, but the wind and sea were dying down.

The man came back to his chair and again appeared to be considering the message he should send out.

“I have my doubts about getting a message through to-night at all,” hinted Jack. “The rain doesn’t always interfere with the Hertzian waves but sometimes it does. Maybe you would better wait till morning.”

“I’ll send it when I choose,” was the growled reply.

At that instant Jack’s hand suddenly shot out across the desk in front of him and turned the switch that sent the current into the detectors. Faintly, out of the storm, some whispered dots and dashes had breathed against his ear-drums. Somebody was trying to send a radio.

Jarrold’s lounging figure stiffened up quickly. He had seen Jack’s sudden motion and guessed its meaning. He leaned forward eagerly while the young operator tuned his instruments till the message beat more strongly on his ears.

Through the storm the message came raggedly but it was intelligible.

“Tropic Queen! Tropic Queen! Tropic Queen!”

“Yes! Yes! Yes!” flung back the boy at the liner’s key. “Who is that?”

“Are you the Tropic Queen?”

The sending of the call across the storm was uncertain and hesitating; not the work of a competent operator, but still understandable.

“Yes, this is the Tropic Queen.”

The answer that came made Jack thrill up and down his spine.

“This is the Endymion!”

Then came a pause that vibrated. Jack pounded his key furiously. The sending on the other craft was bad, and the waves that were beating against the aërials of the Tropic Queen were weak. Although rain does not necessarily hamper the power of the Hertzian billows, and all things being equal the transmission of messages is clearer at night, yet certain combinations may result in poor service.

The spark writhed and squealed and glared with a lambent blue flame as it leaped like a serpent of fire between the points.

But even above its loud, insistent voice calling into the tempest-ridden night could be heard the deep, quick breathing of Jarrold as he leaned forward to catch every move of the young operator’s fingers.

“This is the Endymion,” came again.

“Yes! Yes!” flashed back Jack.

“Have you a passenger named Jarrold on board?”

Jack’s heart and pulses gave a bound. Jarrold was leaning forward till his bristling chin almost touched Jack’s cheek. The man’s hand stole back toward his hip pocket and stayed there.

“Yes, what do you want with him?”

“We—have—a—message—for him,” came the halting reply.

Jack’s fingers were on the key to reply when the quick, harsh voice of Jarrold came in his ear.

“That’s the Endymion. No monkey business now. Send what I tell you. I——”

There was a sudden blinding flash from the instruments and a blaze of blue, hissing fire filled the wireless room.

Jarrold and the young wireless man staggered back, their hands flung across their faces to shield their eyes from the scorching glare. It was all over in an instant—just one flash and that upheaval of light.

“The aërials have gone!” cried Jack.

He darted from the wireless room, leaving Jarrold alone, a look of frustrated purpose in his eyes.

Out along the wet and slippery decks, spray-dashed and awash, rushed the boy. He was headed for the bridge. He found the first officer, Mr. Metcalf, on duty.

The officer was shrouded in gleaming oil-skins and sou’wester. Spray glistened on his cheeks and big mustache as the dim light from the binnacle revealed his features. Ahead of them Jack could make out dimly the big, plunging forepart of the ship as it rushed up a water mountain with glowing phosphorescent head, and then with a swirling roar went sliding down the other side.

“Well, Ready, what’s the trouble?” boomed out Mr. Metcalf good-naturedly. “You seem excited.”

“Yes, sir. I’ve just had a message.”

The officer was alert in a moment.

“A vessel in distress?”

“No, sir. Although——”

“Well, well, be quick. On a night like this any call may be urgent.”

“This was from a yacht. The Endymion, she said her name was.”

“And she’s in trouble?”

Mr. Metcalf was one of those men who leap to instant conclusions. Already he was considering the best method of proceeding to the distressed—as he thought—ship’s assistance.

“No, in no trouble, sir. She had a message for a passenger, but in the middle of it something happened to our aërials.”

“They’ve parted?”

“I don’t know, sir. Anyhow, I’m going aloft to see. I came to report to you.”

“Nonsense, Ready, you can’t go aloft to-night. I’ll send a man.”

“Pardon me, Mr. Metcalf,” broke in Jack. “I don’t want to be disrespectful, but there’s not a man on this ship who could repair those aërials but myself.”

“But you are not used to going aloft,” protested Mr. Metcalf.

“I’ve been up on the Ajax’s masts in worse weather than this to fix anything that was wrong,” he said. “I’ll be all right. And besides, I must go. It’s my duty to do so.”

“Very well, then, but for heaven’s sake be careful. You’ve no idea what the trouble is?”

“No, sir, but I’m inclined to think it is the insulation that has worn and caused a short circuit somewhere. That could easily happen on a night like this.”

“Well, be off with you, Ready,” said the officer, not without reluctance. “Good luck.”

Jack descended from the bridge deck to the main deck. The ship was plunging and jumping like a race-horse. He could catch the wild movement of the foremast light as it swung in crazy arcs against the dark sky.

“Not a very nice night to go aloft,” thought the boy, with a shrug, “but it must be done.”

Temporarily he had forgotten all about Jarrold. All that lay in front of him was his duty, the stern necessity of repairing the aërials upon which it was possible human lives might depend. In the event of accident to the Tropic Queen, the existence of all on board might hang on the good condition of those slender strands of copper wire which alone connected the ship with other craft and dry land.

The wind screamed across the exposed main deck with locomotive-like velocity. Big waves, nosed aside by the bow, viciously took their revenge by sweeping like waterfalls across the ship’s stem. Jack was drenched through before he had fought his way to the weather shrouds, by which slender ladder he had to climb to the top of the swaying steel fore-mast, fully fifty feet above the lurching decks.

He had not put on oil skins and his blue serge uniform, soaked through, clung to his body like an athlete’s tights. But he was not thinking of this as he grabbed the lower end of the shrouds and prepared to mount aloft. A big sea swept across the exposed foredeck, almost beating the breath out of his body. But he clung with the desperation of despair to the steel rigging, and the next moment, taking advantage of a momentary lull, he began to mount.

Long before he reached the cross-trees, his hands were cut and sore and every muscle in his body taut as fiddle strings. About him the confusion and the noise of the storm shrieked and tore like Bedlam let loose.

But stubbornly the figure of the young wireless boy crept upward, flattened out by the wind at times against the ratlines to which he clung, and again, taking every fighting chance he could seize, battling his way up slowly once more. The cross-trees gained, Jack paused to draw breath. He looked downward. He could see, amid the inferno of raging waters, the dim outline of the hull. From that height it looked like a darning needle. As the mast swung, it appeared that with every dizzy list of the narrow body of the ship beneath, she must overturn.

Jack had been aloft often and knew the curious feeling that comes over a novice at the work: that his weight must overbalance the slender hull below. But never had he experienced the sensation in such full measure as he did that night, clinging there panting, wet, bruised, half-exhausted, but yet with the fighting spirit within him unsubdued and still determined to win this furious battle against the elements.

As he clung there, catching his breath and coughing the salt water from his lungs, he recollected with a flash of satisfaction that he had his rubber gloves in his pocket. These gloves are used for handling wires in which current might be on, and are practically shock-proof. Jack knew that he would have to handle the aërials when he got aloft, and if he had not his gloves with him, he would have stood the risk of getting a severe shock.

With one more glance down, in which he could perceive a dim, wet radiance surrounding the ship like a halo, proceeding from such lights as still were aglow on board, the boy resumed his climb.

The most perilous part of it still lay before him. So far, he had climbed a good broad “ladder”—the ratlines stretched between the three stout steel shrouds. From the cross-trees to the top of the slender mast, there was but a single-breadth foothold between the two shrouds running from the tip of the foremast to the cross-trees.

Far above him, cut off from his vision by darkness and flying scud, Jack knew that the footpath he had to follow narrowed to less than a foot in breadth. At that height the vicious kicking of the mast must be tremendous.

It was equivalent to being placed on the end of a giant, pliable whip while a Gargantuan Brobdingnagian driver tried to flick you off.

But Jack gritted his teeth, and through the screeching wind began the last lap of his soul-rasping ascent.

He was flung about till his head swam. His ascent was pitifully slow and tortuous. The reeling mast seemed to have a vicious determination to hurtle him through space into the vortex of waters below him, over which he was swung dizzily hither and yon.

But at last, somehow, with reeling brain, cut and bleeding hands and exhausted limbs, he reached the summit and stretched out cramped fingers for the aërials.

With the other hand he clung to the shrouds, and with legs wrapped round them in a death-like grip, he was dashed back and forth through midair like a shuttle-cock.

Clinging with his interlocked lower limbs, Jack managed to draw on his insulated rubber gloves. Then he fumbled, with fear gripping at his cold heart, for his electric torch, which every wireless man carries for just such emergencies.

He pressed the button and a small, pitifully small, arc of light fell on the aërials where they were secured to the mast. Far beneath him on the bridge, the first officer and the wondering captain—who had been summoned from his berth—watched the infinitesimal fire-fly of light as it flickered and swayed at the top of the mast.

The storm wrack flew low and at times it was shut out from their gaze altogether. At such times both men gripped the rail with a dreadful fear that the brave lad, working far above them, had paid the penalty of his devotion to duty with his life.

But every time that they looked up after such a temporary extinguishment of the flickering light, they saw it still winking like the tiny night-eye of a gnome above them in dark space.

With fingers dulled by the thick rubber covering which he dared not remove, Jack worked among the aërial terminals. One by one he counted the strands.

One, two, three, four, five.

Yes, they were all there. But he did not count them as fast as that. Instead, between the fingering of one and another an interval of ten minutes might elapse, during which time he was flung from pole to pole, dry mouthed and dizzy.

Then came a sudden flash of lightning outlining the rigging, the steel hull far below him, the anxious figures on the bridge and the angry heavens in blue, glaring flame. But Jack had no eye for this. The sudden light had shown him a jagged rip in the insulation of the wires where they were joined to the mast rigging. Through this, current had been leaking into the mast and robbing the aërials of their power of sending or receiving, short circuiting the Hertzian waves.

Jack waited for a lull and then, almost dead with nausea and brain sickness from his wild buffeting, he reached for his electrician’s tape and began making hasty repairs on the electric leak. He bound coil after coil of the adhesive stuff around the exposed wire, till it was blanketed beyond chance of “spilling” into the rain.

Then, his work done, he rested for an instant to steady his whirling senses, and then began the long descent.

Now that the job was over, he felt that he could never live to reach the deck, miles and miles—hundreds and hundreds of miles—below him. Step by step, though, he descended, fighting for his life against the sense numbness that was creeping over him. Limbs and intelligence seemed equally absent. He felt as if he were a disembodied being, floating through space on the wings of the storm.

He appeared to have no weight. Like a thistle bloom he thought that he might be blown where the winds wished. Conquering this feeling, it was succeeded by a leaden one. He was too heavy to move. His feet felt enormous, and heavy as a deep-sea diver’s weighted boots. His head was balloon-like and appeared to sway crazily on his shoulders.

But he still descended. Step by step, painfully, semi-consciously, the brain-sick, nauseated boy clung to the ratlines. On his grip depended his life, and this, in a dim, stupid sort of way, he realized.

If he could only reach the cross-trees! Here he could rest in comparative security for a while.

He must reach them, he must! He wasn’t going to die like this. A furious fighting spirit came over him. His head suddenly cleared; the deadly nausea left him; his limbs grew light.

Jack shouted aloud and came swiftly down. He called out defiantly at the storm. He raved, he yelled in wild delirium.

All at once he felt the cross-trees under his feet. With a last loud cry of triumph he sank down on the projecting steel pieces that formed, at any rate, a resting place.

Then came another wild swing of the ship, and a vicious gust.

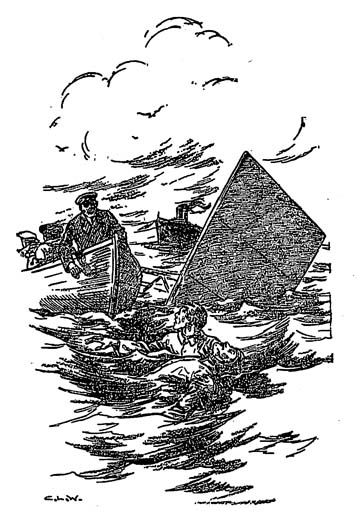

Jack felt himself flung from the cross-trees and out into the dark void of the storm.

Down, down, down he went, straight as a stone toward the dark, black, raging vortex through which the ship was fighting.

He felt rather than heard a despairing cry; but did not know whether it had come from his lips or not.

Then a rushing dark cloud enveloped him, and with a fearful roaring in his ears, Jack’s senses swam out to sea.

“The light has disappeared, Metcalf. Do you think the poor lad is lost?”

Far below on the bridge, Captain McDonald, oil-skinned like his officer, peered upward.

“The good Lord alone knows, sir,” was the fervent reply. “It was a madcap thing to do. I should never have let him go.”

“It’s done now,” muttered the captain. “Though, had you consulted me, I should have forbidden it. That boy is the bravest of the brave.”

“He is, sir. You may well say that. A seasoned sailorman might have hesitated to go aloft to-night.”

“I wish to heaven I knew what had become of him and if he is safe, yet I wouldn’t order another man up there in this inferno.”

There was a voice behind him.

“Vouldt you accepdt idt a volunteer, sir?”

“You, Schultz?” exclaimed the captain, turning around to the old quartermaster who was just going off his trick of duty at the wheel. “Why, man, you’d be taking your life in your hands.”

“I’ve been up der masts of sheeps off der Horn on vorse nights dan dees,” was the calm reply. “Ledt me go, sir.”

“You go at your own responsibility, then,” was the reply. “I ought not to let you up at all, and yet that boy—go ahead, then.”

The old German quartermaster saluted and was gone.

From the bridge they saw him for a moment, in the gleam of light from a porthole, crossing the wet deck.

He clambered into the shrouds and then began climbing upward along the perilous path Jack had already traveled.

“Pray Heaven we have not two deaths to our account to-night, Metcalf,” said the captain earnestly to his first officer.

“Amen to that, sir,” was the reply.

And then there was nothing but the shriek of the wind and the beat of the waves, while the two officers gazed piercingly upward into the darkness where they knew not what tragedies might be taking place.

Suddenly Captain McDonald had an inspiration.

“Metcalf!” he cried, above the storm.

“Sir!” was the alert response of the Tropic Queen’s chief officer.

“Order the searchlight turned on that mast!”

One of the two quartermasters, struggling with the bucking, kicking wheel, was ordered to get the apparatus ready and focus it on the foremast.

The canvas hood was taken off the big light and then a switch snapped, sputtering bluely. A radiant spear of light pierced the night. It hovered vaguely for a few instants and then settled on the foremast.

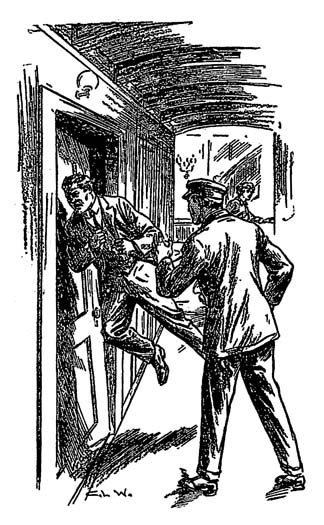

It revealed a thrilling scene. Schultz had clasped in his arms the unconscious form of Jack Ready. For the young wireless man, when he collapsed, had been caught by a stay and held in position on the cross-trees.

Slowly, and with infinite caution, the old quartermaster began to descend the shrouds. It was a nerve-racking task to those looking on. Jack was not a light-weight, and the descent of his rescuer, clasping the boy with one arm while he held on with all his strength, was painfully slow.

But at last they reached the deck in safety, and Captain McDonald was there in person to meet them. He wrung Schultz’s hand in a tight grip as the old seaman stood pantingly before him.

“That was as brave a bit of work as I’ve seen done since I’ve been going to sea, Schultz,” he exclaimed. “I’ll see to it that the company gives you recognition. But now let us take this lad to my cabin. He’s opening his eyes and the doctor can give him something that will soon set him on his feet again.”

And so it proved. Half an hour after Jack had been laid on a lounge in the skipper’s cabin and restoratives had been administered by Dr. Flynn, he was feeling almost as hale and hearty as ever, although his terrible ordeal when he was flung back and forth pendulum-wise had left him with a racking headache.

The captain showered congratulations on him, but reminded him that never again must he risk his life in such a perilous way.

“The job could have waited till daylight, anyhow,” he said.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said Jack, firmly but respectfully, “it could not. You know that I was in communication with a ship—the yacht Endymion—when the insulation wore away and my ‘juice’ began to leak?”

“No, I knew no such thing,” said the captain.

“Mr. Metcalf knew of it, sir.”

“In all the excitement caused by your exploit, young man, he must have forgotten to tell me.”

“That was probably the reason, sir. But the Endymion——” The captain broke in as if struck by some sudden thought.

“Jove, lad, the Endymion, you say?”

“Yes, sir, do you know her?”

“I know of her. She bears no good reputation. Once she was chartered to the Haytian government and was used as a war ship; then she was in the smuggling trade along the coast. The last I heard of her she was laid up in the marine Basin at Ulmer Park. Her history has been one of troubles. Do you feel strong enough to go back to your key?”

“Yes, sir,” exclaimed Jack eagerly. “Young Smalley, my assistant, is too seasick to work to-night. I’ll take the trick right through.”

“Good for you, my boy. I’ll see that you are no sufferer by it. By the way, did the Endymion have any message? Was she in trouble?”

“No, sir, but they wished to give some sort of a radio to a Mr. James Jarrold, one of the first-class passengers.”

The captain tapped his foot musingly on the polished wood floor of his cabin.

“Odd,” he mused, “I wonder what possible communication they could have to make to him. Is Jarrold a heavy-set man with a blue, square jaw and bristly, black hair?”

“Yes, sir, that is the man to the dot.”

“I have noticed him at dinner. He sits at the first officer’s table. Back in my head I’ve got a sort of indefinable idea that I’ve seen him somewhere before, but just where I cannot, for the life of me, call to mind just now.”

“It is too bad that the aërials went out of commission just as that other operator was starting to give the message.”

“It was, indeed, but you must try now to pick up this Endymion again. I’m curious to know more of her and of our mysterious passenger.”

“I’ll report to you the instant I get anything, sir,” Jack assured him, and hurried off.

On the way he passed Schultz and put out his hand with direct, sailor-like bluntness.

“You saved my life to-night, Schultz. I’ll never forget it,” he said simply, but there was a wealth of feeling behind the quiet words.

“Oh, dot makes it no nefer mindt, Yack,” said the old German. “Don’t get excitedt ofer idt. Idt vos just a yob dot hadt to be done und I didded idt.”

“It was a great deal more than that,” said Jack, with warmth. “I hope some day I will get a chance to repay you.”

But Schultz, embarrassed and red as a beet under his tan, had hurried off. Like most sailors, Schultz hated sentiment. To him, his daring deed of saving Jack from his perilous perch in the cross-trees had been all in the line of duty.

Back in the wireless room once more, Jack looked in on Sam. The boy was sitting up in bed staring feverishly out into the wireless room.

“Oh, Jack, I’m glad you have come back!” he exclaimed. “Where have you been?”

“Fixing a little job of work, youngster. Something was wrong with the wireless. How do you feel?”

“Better, but oh, what a head! It’s the worst feeling I ever knew!”

“Like something to eat?”

“For heaven’s sake, don’t mention it! The mere thought makes me feel bad again. But, listen, Jack, I’ve something to tell you. I wakened about half an hour ago and there was a man out there in the wireless room.”

“What?”

Jack had temporarily forgotten all about Jarrold. Now Sam’s remark brought the earlier scene back to him. What had Jarrold been doing in the wireless room while he was absent?

“He was stooping over the desk, rummaging about the papers and dispatches,” said Sam in response to Jack’s eager questions.

“Did he take anything?” asked Jack.

“I don’t know. I called out to him and asked him what he was doing.”

“Yes; what did he say?”

“He didn’t say a word. Just hurried out. Who was he?”

“A man named Jarrold. He’s a first-cabin passenger. He came in here this evening and was much interested in getting first news of a yacht called the Endymion.”

“I don’t like his looks.”

“Frankly, neither do I, and yet one cannot let a man’s appearance count against him. But if he was rummaging about that desk, that is another matter.”

“I think he knows something about wireless himself. I saw him fiddling with the key.”

“At any rate, I’ll keep a close eye on Mr. Jarrold,” Jack promised himself. “I don’t quite know what all this means, but I bet I’ll find out before it’s over!”

There was not much more sleep for Sam that night. He fought bravely against his seasickness and took the key for a time while Jack stole a catnap. Both boys worked hard to get in touch with the Endymion once more, but they failed to raise her operator. So far as Jack could make out, nothing had been taken from the desk by Jarrold; and the boy came to the conclusion that the man, disbelieving his word, had searched the desk for some evidence of a previous message from the Endymion.

At breakfast the next morning Jarrold, cleanly shaven around his blue chin, appeared in the saloon of the ship accompanied by a very pretty young lady, who, Jack learned, was his niece, Miss Jessica Jarrold. The man did not raise his glance to Jack, although the latter eyed him constantly. The young woman, though, regarded Jack with a somewhat curious gaze from time to time. He was pretty sure in his own mind that she knew of the events of the night.

In fact, she made it a point to leave the table at the same time as did Jack. As they both emerged on deck through the companionway she addressed him.

“Have you heard anything more of the Endymion?” she asked.

Although the sea was still running high, the sky was clear and the weather good. She steadied herself against a stanchion as the ship pitched, and Jack found himself thinking that she made a pretty picture there. She was clad in a loose, light coat, and bareheaded, except for a scarf passed over a mass of auburn hair, from which a few rebellious wind-blown curls escaped.

Jack raised his uniform cap.

“Nothing, Miss Jarrold,” he said. “Your——”

“My uncle,” she continued for him, “is very anxious to be informed as soon as you do hear.”

“Of course, the captain will have to be told first,” he said. Her dark eyes snapped and she bit her lip with a row of perfectly even, gleaming little teeth.

“Can’t it be arranged so that my uncle can know first about it?” she said, breaking into a smile after her momentary display of irritation. “Suppose you told—well, me, for instance.”

“I would be only too glad to do anything to oblige you, Miss Jarrold,” said Jack deferentially, “but that is out of the question.”

“But why?” she demanded.

“It’s a rule,” responded Jack.

“Oh, dear, what is a stupid old rule! My uncle is rich and would pay you well for any favor you did him, and then I should be awfully grateful.”

“I’m just as sorry as you are,” Jack assured her, “but I simply could not do it.”

“Well, will you let my uncle and myself sit up in your wireless room and wait any word you happen to catch?”

“That, too, I am afraid I shall have to refuse to do,” said Jack. “Such a procedure would also be against the rules; and especially after something that happened last night, I am determined to enforce the order to the letter.”

“What happened last night?” she asked, quizzically eying him through narrowed lids.

“I am afraid you will have to ask your uncle about that, Miss Jarrold. No doubt he will tell you.”

Eight bells rang out, and Jack, raising his cap, said:

“That’s my signal to go on duty. Depend upon it, though, Miss Jarrold, if I get any word from the Endymion which I can give you without violation of the rules, or if any message comes for either yourself or your uncle, you will be the first to get it.”

She made a gesture of impatience and turned to meet her uncle, who was just emerging from the companionway. Jarrold glared at Jack with an antagonism he did not take much trouble to conceal.

“Any news of the Endymion?” he growled out in his deep, rumbling bass.

“As I just told Miss Jarrold, there isn’t,” said Jack. “And, by the way, I hope you had a pleasant evening in my cabin last night.”

“I left there as soon as you did, right after the short circuit,” said Jarrold, turning red under Jack’s direct gaze.

“I’m sorry to contradict you, Mr. Jarrold,” replied Jack, holding the man with keen, steady eyes that did not waver under the other’s angry glare. “You were in there quite a time after I left.”

“I was not, I tell you,” blustered Jarrold. “You are an impudent young cub. I shall report you to the captain.”

“I would advise you not to,” said Jack calmly. “If you did, I might also have to turn in a report from Assistant Sam Smalley, who was in the other room all the time and saw almost every move you made.”

“What! there was someone there?” blurted out Jarrold. And then, seeing the error he had made, he turned to his niece. “Come, my dear, let us take a turn about the decks. I refuse to waste more time arguing with this young jackanapes.”

Later that morning something happened which caused Jack to cudgel his brain still further to explain the underlying mystery that he was sure encircled the girl and Jarrold, and in which Colonel Minturn was in some way involved.

He was sitting at the key with the door flung open to admit the bright sunshine which sparkled on a sea still rough, but as a mill pond compared with the tumult of the night before, when there came a sudden call.

“Tropic Queen. Tropic Queen. Tropic Queen.”

“Yes, yes, yes,” flashed back Jack.

He turned around to Sam.

“I’ll bet a million dollars that it is a navy or an army station calling,” he said. “You can’t mistake the way those fellows send. It is quite different from a commercial operator’s way of pounding the brass.”

A moment later he was proved to be right.

“This is the Iowa,” came the word. “We are relaying a message from Washington to Colonel Minturn on board your ship. Are you ready?”

“Let her come,” flashed back Jack.

He drew his yellow pad in front of him and sat with poised pencil waiting for the message to come through the air from a ship that he knew was at least two hundred miles from him by this time.

“It is in code; the secret government code,” announced the naval man.

“That makes no difference to me,” rejoined Jack. “Pound away.”

“All right, old scout,” came through the air, and then began a topsyturvy jumble of words utterly unintelligible to Jack, of course.

The message was a long one, and about the middle of it came a word that made Jack jump and almost swallow his palate.

The word was Endymion, the name of the yacht that had sent out a call for Jarrold through the storm.

Then, closely following, came a name that seemed to be corelated to every move of the yacht: James Jarrold!

At last the message, about two hundred words long, was complete. It was signed with the President’s name, so Jack knew that it must be of the utmost importance. He turned in his chair as he felt someone leaning over him and noticed a subtle odor of perfume. Miss Jarrold, with parted lips, was scanning the message eagerly. He caught her in the act.

But the young woman appeared to be not the least disconcerted by the fact. With a wonderful smile she extended a sheet of paper.

“Will you send this message for me as soon as you can, please?” she asked.

Jack was taken aback. He had meant to accuse her point blank of trying to read off a message which was clearly of a highly important nature. But her clever ruse in providing herself with the scribbled message that she now held out to him had quite taken the wind out of his sails.

“Here, Sam, take this message to Colonel Minturn at once,” he said, thrusting the paper into Sam’s hands and carefully placing his carbon copy of it in a drawer.

“Now, Miss,” he said, looking the girl full in the eyes, “I’ll take your message.”

“Oh, I’ve changed my mind now,” said the girl suddenly turning. “Sorry to have troubled you for nothing. Don’t forget about the Endymion now.”

And she was gone.

“Well, what do you know about that?” muttered Jack. “A woman is certainly clever. Of course, she merely came in here to see what was going on, and, by Jove, she came in at just the right time, too. Lucky the message was in code. And then she was foxy enough to have that message of hers all ready so that I couldn’t say a thing. Oh, she’s smart all right! I wish I knew what game was up. I was right about Colonel Minturn playing some part in it, judging from that dispatch, but for the life of me I can’t make out what is up.”

He was still reflecting over this when Colonel Minturn, with Sam close on his heels, entered.

Jack saluted him.

“Good morning,” said the colonel, introducing himself, “I am Colonel Minturn. I have just received a cipher dispatch and want to send a reply.”

“I guess I’ll have to relay it through the Iowa if it is for Washington,” said Jack.

“That is just its destination,” was the rejoinder. “By the way, I hear from the captain that you did a very brave act last night in climbing the foremast in the storm and repairing the wireless. That was nervily done and I want to compliment you on it.”

“Glory! And he didn’t even breathe a word of it to me!” muttered Sam under his breath.

Jack got red in the face. “Why, that was nothing, Colonel,” he said. “It had to be done, and nobody but I could have done it.”

“You are as modest as all true heroes,” said the colonel approvingly. “But, now, here is the dispatch I want you to send. You see, like the other, it is in cipher. The government’s secrets have to be closely guarded.”

Jack took the message and filed it and then proceeded to raise the Iowa again.

Before long came a reply to his insistent calls.

“Here is the Iowa. What is it?”

Something peculiar about the sending struck Jack, but he went ahead.

“This is the Tropic Queen. I have a message from Colonel Minturn to Washington. It must be rushed through.”

“Very well, transmit,” came the answer; but once more the curious ending of the other wireless man struck him forcibly.

“I don’t believe that is the Iowa at all,” he muttered to himself. “I never heard a man-o’-war operator sending like that. It sounds more like—like—by hookey! I’ve got it. It’s that fellow on the Endymion,—the craft that Jarrold is so much interested in.”

Just then, winging through the air, came the short, sharp, powerful sending of the Iowa.

“Hullo, there, Tropic Queen, this is the Iowa. Who is that fellow butting in?”

“I don’t know,” Jack flashed back. “Re-tune your instruments so that he can’t crib this message I’m going to send you. Tune them to man-of-war pitch. From what I heard of his sending, his batteries are too weak to reach such high power.”

“All right,” was the brief reply.

The two instruments were then run up to a pitch which only the most powerful supply of “juice” could give them. Then came the test and everything was found to be working finely.

Jack at once rattled off the message. In it he noticed that the name Jarrold recurred, also the Endymion. Colonel Minturn stood close beside him and watched him with interest as Jack worked his key in crisp, snappy, expert fashion.

“You are a very good operator, my boy,” he said when Jack had flashed out good-by with the squealing, crackling spark. “I may have government work for you some day. Should you like it?”

“Oh, Colonel!” cried the boy, his face lighting up, “I’d rather work for Uncle Sam than for anyone else in the world.”

“Then some day you may have that opportunity. In the meantime I want you, without saying a word to anybody, to inform me of any suspicious moves on the part of this man Jarrold.”

“Why, is he—is he an enemy of Uncle Sam’s?” Jack ventured.

“He is probably the most dangerous rascal in existence,” was the staggering reply.

Jack looked the astonishment he felt. While he had sensed something of sinister import about Jarrold right along, still he had never guessed the man could merit such a sweeping description of bad character.

“The most dangerous rascal in existence,” he repeated.

“Yes, I called him that and I mean it,” was the reply. “What he is doing on this boat, I don’t know. But I have a guess and am prepared for him.”

He drew from his hip pocket a wicked looking automatic.

“Is it as bad as that?” asked Jack.

“I don’t know. But, at any rate, I am prepared. Jarrold has been mixed up in desperate enterprises in a score of countries. He is a diplomatic free lance of the worst character. It was Jarrold who stole the documents relating to the Russian navy, which it cost that country so much time and trouble to recover before they found their way into the hands of another power.”

“And the young lady—his niece?”

“She has been implicated in most of his plots. They are a dangerous pair. You will do me and the government a great favor by keeping an eye on them. You will be able to do this, as I understand they are trying hard to establish communication with a yacht called the Endymion.”

“Yes; both the man and the girl appear very anxious to do that,” rejoined Jack.

“Jarrold has the stateroom next to mine. In my possession are documents that would be of immense value to a certain far eastern power that wishes the United States no good.”

“You think that Jarrold is after these?” asked Jack.

“It is the only supposition I can go upon. That cipher message from the government warned me to be careful of the man, as his errand had been surmised by the Secret Service men. They also found out about the Endymion, which fact I did not know before.”

“And he is, apparently, an American, too,” exclaimed Jack.

The colonel nodded.

“Yes, he is a westerner by birth, I believe, but that makes little difference to men of his type. The only country they know is the one that gives the biggest price for their rascalities.”

“He ought to be shot for trying to betray the country he owes his birth to,” said Jack hotly.

The colonel smiled and laid a hand on the excited lad’s shoulder.

“You feel about it as I do, lad,” he said. “But remember we have nothing to go upon as yet. Absolutely nothing.”

Jack agreed that this was so, and after some more conversation, the colonel left the wireless room, first warning the young operator that their talk must be held absolutely confidential.

Of course Jack promised this, and so did Sam. But both lads felt that they were playing parts in a big game, the nature of which was an absolute mystery so far.

“It’s like sitting on a keg of dynamite,” said Sam.

“Yes; I have a feeling that there is something electrical in the air,” said Jack, “besides wireless waves. It may break at any minute, too.”

“If it does, I hope we get a chance to help out the colonel.”

“Yes, he is a fine man, a splendid type of soldier. I don’t wonder the government chose him for this Panama errand.”

“It’s a mighty responsible job,” agreed Sam.

“And particularly when such a clever rascal as Jarrold, with unlimited power at his back, is hanging about.”

But then it was dinner time, and Sam, whom even the most engrossing conversation could not keep from his meals, hastened below. When he came back, he had an important look on his face.

“I stopped on deck for a breath of fresh air,” he said, “and stood out of the wind behind a big ventilator. Jarrold and his niece came along.”

“Didn’t they see you?”

“No; they were talking too earnestly; besides, the ventilator hid me, anyhow.”

“Did you hear what they said?”

“I couldn’t catch much of it.”

“Well, let’s hear what you were able to pick up.”

“Well, the man appeared to be urging something that the girl objected to. ‘I tell you it is too dangerous,’ I heard her say.

“Then the man, in a rough voice, told her she was a foolish woman and that he was going ‘to do it to-night at all costs.’

“‘You may ruin everything,’ she said, but he only laughed and said that if he failed this time, he would succeed later on, anyway.”

“Hum, that’s a mighty interesting scrap of conversation,” mused Jack, “I wonder what the old fox is up to now.”

“Maybe we’d better inform the colonel,” suggested Sam.

“Hardly. Not with the meager information we’ve got. He would only laugh at us. No, we’ll have to wait and see what the event will be. But depend upon it, there is something in the wind.”

Jack was right. What that something was, he was not to learn till later, but it was far more startling and was to involve him more deeply than he imagined.

At midnight, while the Tropic Queen was plying ever southward through smooth seas and under a dark canopy of sky lit by countless stars, Jack left his key and, calling Sam, whose turn it was on watch, went below for his customary midnight “snack.” A sleepy-eyed steward served him in the big saloon, which looked empty and desolate with only one light in all its vastness.

Jack ate heartily and then prepared to go on deck again. He had reached the foot of the saloon stairs when a sudden sound made him pause.

It was the rustle of skirts. Jack drew back into the shadow which hung thickly over that part of the saloon. To his astonishment, for he thought that all the passengers—except a belated party in the smoking-room—were in bed, he saw that the figure which passed swiftly through the corridor beyond the staircase was that of Miss Jarrold.

She wore a white dress which showed ghost-like through the gloom, although the corridor was dimly lighted. But there was no mistaking her slender, graceful outlines and quick, panther-like walk.

Suddenly the conversation that Sam had repeated to him flashed across Jack’s mind. It had appeared to foreshadow some desperate attempt to gain whatever the pair had set their minds on. Almost beyond a doubt, these were the papers and plans relating to the Panama Canal. Jack knew that Colonel Minturn’s cabin was in the direction the girl was following.

Could it be possible that——

Suddenly a piercing shriek came, followed by cry after cry.

Jack’s heart stood still. His scalp tightened.

The cry was the most blood-chilling that can be heard at sea.

The cry was the most blood-chilling that can be heard at sea.

“Fire! Fire! Fire!”

Jack dashed down the passage. From every stateroom now, shouts of men and screams of women were coming. Warned by he knew not what instinct, he made for Colonel Minturn’s cabin.

It lay just around a corner of the passage. He had just gained it, when he saw a bulky figure, that of Jarrold, hurl itself against the door and go smashing through it. Jack rushed up.

Jarrold turned on him with a savage growl.

“Get away from here, boy. I’ll save Colonel Minturn. You go and warn the other passengers.”

But Jack made no move to go. Instead, he stepped into the cabin. In his bunk lay the colonel, apparently sleeping deeply. Jack shook him, but he did not move, only lay there, breathing heavily.

“This man has been drugged,” he exclaimed half aloud.

At the same instant he felt the hulking form of Jarrold fling itself at him.

“You infernal, interfering young spy,” he snarled. “Get out of here. Get back to your post. Send out an alarm of fire.”

He seized Jack with his big hands. The boy’s blood boiled. Big as Jarrold was, and powerful, too, Jack was, he thought, a match for him.

Jarrold aimed a fierce blow at him. Jack dodged it and parried it with one of his own. Then the two clinched. Jarrold’s powerful arms encompassed the boy, squeezing the breath out of him.

Outside the cabin, people in all stages of dress and undress were rushing about screaming and shouting. The whole ship was in pandemonium. Within the cabin, for Jarrold had closed the door when he followed Jack in, the two combatants, the boy and the man, fought in desperate silence for the mastery, while the man in the bunk lay with closed eyes, breathing heavily.

Back and forth they swayed till Jack suddenly wrenched himself loose. He delivered a powerful blow and stopped a bull-like rush from Jarrold. The fire, everything, was forgotten before his desire to overcome the man who had attacked him.

Jarrold was, as has been said, a bull of a man. Thick-necked, powerful and possessed of no little science, he could have torn Jack to pieces if he could have gripped him right. But Jack, once free of his clutches, was careful to avoid this.

Jack possessed no little of the science of the gymnasium, too. He fought coolly, taking every advantage of his skill. Again and again he dodged Jarrold’s mad rushes, and again and again he landed blows which seemed heavy enough to fell an ox.

But they did not appear to have any effect on Jarrold’s big frame. A mere grunt was the only sign that he had noticed them. Jack began to despair of handling his man after all.

In the struggle, furniture was smashed, Jarrold’s coat torn, and both combatants’ faces were cut and bruised. Gasping for breath, dizzy from the thundering shock of the few blows Jarrold had driven home like flesh and blood sledge hammers, Jack was about to give up, when suddenly he noticed that no one was facing him. Jarrold, breathing heavily, his face purple, lay stretched across a lounge as he had fallen.

A terrible thought flashed through Jack’s mind. Suppose he had killed him?

Jack rushed out into the hallway. It was not, as he had expected, smoke-filled, nor was there any odor of fire in the air. Somewhere he could hear the voices of officers shouting above the distant hub-bub in the saloon: “Keep your heads! There is no fire.”

Doctor Flynn, the ship’s surgeon, came hurrying by. Jack stopped him and explained what had occurred in Colonel Minturn’s cabin.

“We must send for help and carry them both out of danger at once,” he said.

“Danger? But there is no danger,” exclaimed the doctor.

“But the fire?” gasped the boy.

“There is none. It was either the overwrought nerves of a silly woman that started the panic, or else there was some malicious design underlying the whole thing.”

The thought of what he had seen as he stood in the shadow of the saloon stairway rushed across Jack’s mind: Miss Jarrold’s sudden appearance and then the scream of fire. Could it have been possible that this was the thing that Sam had overheard her and her uncle debating? That, taking advantage of the panic they knew would be caused by such an alarm in the dead of night, Jarrold had schemed a way to enter Colonel Minturn’s cabin?

“Will you come into Colonel Minturn’s cabin with me at once, doctor?” asked Jack.

“Certainly, my boy. But,” and the doctor stared at him in amazement, “what has happened to you? Your face is bruised and marked. Have you been fighting?”

“A little bit,” said Jack grimly.

“With whom?”

“With a man I believe to be a consummate scoundrel. By the merest accident on earth, I happened along here just in time to frustrate what I believe to be a plot against Colonel Minturn.”

All this Jack explained hastily as they retraced their way down the corridor to Colonel Minturn’s cabin. The panic had died down, and the passengers, reassured now, were making their divers ways back to their cabins. Some tried to turn the whole matter into a joke. Others looked sheepish over the panic-stricken way in which they had behaved.

But when the two entered the colonel’s cabin a surprise awaited them.

Jarrold was not there.

Jack rubbed his mental eyes. He could have sworn he had left the man lying across the lounge, to all appearances stunned. Now, in the brief interval that the boy had been out of the cabin, the man had gone.

“He must have been playing ’possum,” said the surgeon, when Jack had briefly explained the circumstances; “but now let us see to Colonel Minturn.”

The doctor bent over the officer’s form as it lay in the bunk. The colonel was breathing heavily, his pulse was slow, his face gray.

“Run to my cabin for my medicine bag,” ordered the doctor to Jack. “You will find it on my lounge. Hurry back.”

Jack waited to ask no questions but sped off. The corridors were still choked with passengers discussing the fire scare. Most of them appeared to think it had been a grim and criminal form of joke on somebody’s part. There was talk of offering a reward for the discovery of the culprit.

But Jack, knowing what he did, placed, as we know, a more sinister construction on the midnight alarm. He was soon back with the doctor’s bag. The surgeon took out of it a small syringe and injected some sort of solution into the unconscious man’s arm.

“What is the matter with him, sir, do you think?” ventured Jack, as the doctor, his hand on Minturn’s pulse, sat by the side of the bunk.

“He has been drugged. That much is plain. Although what the agency was, I cannot guess,” was the rejoinder.

A small glass article lying on the floor caught Jack’s eye. It was an atomizer, such as are used for perfumes. But this was filled with a gray powder. He pressed the rubber bulb and an impalpable cloud of the powder was sprayed into the air. He immediately felt sick and dizzy.

“Look here, sir, what do you make of this?” he cried excitedly, handing it to the doctor. “I found it on the floor. It must have dropped from Jarrold’s pocket while we were struggling. I’m sure that that powder in it is some sort of drug. When I sprayed it out, it made me feel weak and faint.”

The doctor took the glass vessel, unscrewed the top and shook out a small quantity of the powder on his palm.

“This is an important discovery, indeed,” he exclaimed. “It is a sleeping powder used by a certain South African tribe. A sufficient quantity sprayed into the atmosphere would send anyone into a coma. It is not poisonous, merely sleep producing.”

“Then you think that some of it was sprayed into this room, possibly through the transom, by Jarrold before——”

“We’ll leave Mr. Jarrold’s name out of this for the present,” said the doctor shortly. “Remember, we have no proof against him. For all you know, and for all that appears, he broke in here to try to save the colonel when the cry of fire occurred.”

“But he attacked me,” protested Jack.

“His answer to that would be that you were not at your post, where you should have been.”

Jack colored. This was true. Jarrold had indeed a rejoinder to everything he might say against the man. When it came to a point, the lad had plenty of suspicions and theories, but absolutely no proofs to offer. He couldn’t even state positively that the atomizer full of the sleeping powder was Jarrold’s.

The colonel moved uneasily and opened his eyes. In a few moments he was able to talk.

“Why, what has happened?” he asked drowsily, looking first at the doctor and then at Jack.

“First, will you tell us the last thing you recollect, Colonel?”

“Most assuredly. I came to bed early. Before turning in, I examined certain papers of mine and found they were all in perfect order. This done, I lay down with a book. Suddenly I felt unaccountably drowsy, and—and that’s all. But what has occurred in the meantime? I can tell by your presence in the cabin that something out of the ordinary is up.”

“Will you first oblige me by making sure your papers are safe?” asked the doctor.

“Certainly; they are in this box under my pillow. Ah yes, everything is in perfect order. As you see, this is a combination lock. I could tell in an instant if it had been tampered with.”

“Then, Colonel, I think that you should thank this young man here for saving you from a theft that might have cost you dearly,” said the doctor, indicating Jack.

“I—I must confess I don’t understand,” said the colonel, looking bewilderedly from one to the other of his two companions.

“Then let me enlighten you.” And, supplemented from time to time by Jack, the doctor gave a concise account of the incidents leading up to the discovery of Jarrold breaking into the colonel’s cabin.

The officer could hardly believe his ears.

“Of course I have suspected Jarrold all along, and cannot be too grateful to this young man for his vigilance,” he said; “but the diabolical ingenuity of the man is beyond me.”

“He ought to be in irons at this minute,” asserted the doctor, “but so far as I can see, he has covered up his tracks so cleverly that we have nothing upon which to base a complaint against him.”

“At the present time, no, unfortunately,” said the colonel reluctantly. “And if it had not been for Mr. Ready, here, the whole plot might have proved a complete success.”

“I think it is reasonably certain that when you awakened, which might not have been till late to-morrow morning, you would have found your papers gone,” said the doctor.