The Project Gutenberg EBook of Randolph Caldecott, by Henry Blackburn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Randolph Caldecott

A Personal Memoir of His Early Art Career

Author: Henry Blackburn

Illustrator: Randolph Caldecott

Release Date: October 17, 2012 [EBook #41086]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RANDOLPH CALDECOTT ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Diane Monico, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

BY

HENRY BLACKBURN,

EDITOR OF "ACADEMY NOTES," ETC.; AUTHOR OF "BRETON FOLK,"

"ARTISTS AND ARABS," ETC.

WITH

ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS,

9, LAFAYETTE PLACE.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1886.

The object of this memoir is to give some information as to the early work of Randolph Caldecott, an artist who is known to the world chiefly by his Picture Books.

The extracts from letters have a personal charm apart from any literary merit. The majority of the letters, and the sketches which accompanied them, were sent to the author's family; others have[Pg viii] been kindly lent for this memoir by Mr. William Clough, Mr. Locker-Lampson, Mr. Whittenbury, and other friends. Acknowledgments are also due to the publishers who have lent engravings.

At the desire of Mr. Caldecott's representatives,—to whom the author is indebted for extracts from diaries and other material—the consideration of his later work is reserved for a future time.

Although the text of this book is little more than a setting for the illustrations, it is hoped that the material collected may be found interesting.

103, Victoria Street, Westminster,

September 1886.

| Chap. | PAGE |

| I.—His early Art Career | 1 |

| II.—Drawing for "London Society" | 13 |

| III.—In London, the Harz Mountains, etc. | 29 |

| IV.—Drawing for "The Daily Graphic" | 51 |

| V.—Drawing for "The Pictorial World" | 67 |

| VI.—At Farnham Royal, Bucks | 90 |

| VII.—"Old Christmas" | 100 |

| VIII.—Letters, Diagrams, etc. | 117 |

| IX.—Royal Academy, "Bracebridge Hall," etc. | 134 |

| X.—On the Riviera | 148 |

| XI.—"Breton Folk," etc. | 165 |

| XII.—At Mentone, etc. | 190 |

| XIII.—Conclusion | 203 |

| Appendix | 211 |

The unpublished illustrations are marked with an asterisk *

| PAGE | |

| Portrait | Frontispiece |

| *Decorative Design by R. Caldecott | vii |

| *Tailpiece | xvi |

| *Air—"I know a Bank" | 1 |

| *First Clerk—Second Do. | 2 |

| *Coom, then | 3 |

| *Three Friends | 4 |

| *Going to the Dogs | 5 |

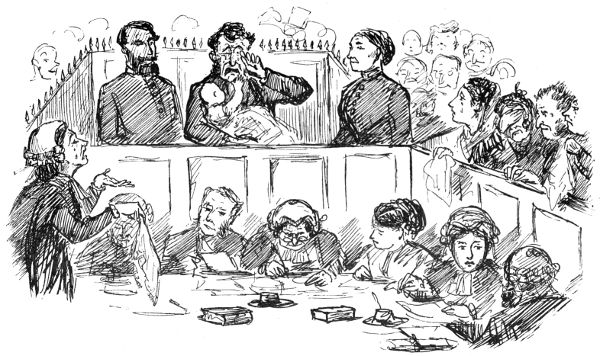

| *A Sketch in Court | 7 |

| *Full Cry | 8 |

| *In the Hunting Field | 9 |

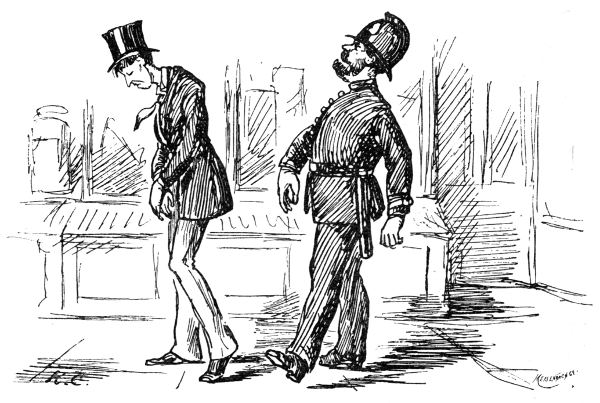

| *Street Sketch—Policeman, etc. | 10 |

| *Society in Manchester | 11 |

| *A New Contributor (London Society) | 13 |

| Education under Difficulties | 14 |

| Ye monthe of Aprile | 15 |

| Sketch in Hyde Park | 16 |

| The Chancellor of the Exchequer | 17 |

| *The Trombone | 18 |

| The Two Trombones | 19 |

| Christmas Day, 4.30 A.M. | 20 |

| Clinching an Argument | 21 |

| Snowballs | 22 |

| [Pg xii] Heigh-ho, the Holly! | 23 |

| Going to Cover | 25 |

| Hyde Park—Out of the Season | 26 |

| Coming of Age of the Pride of the Family | 27 |

| *The end of all things | 28 |

| *Sketch on a Post Card | 29 |

| First Drawing in "Punch," 22nd June, 1872 | 31 |

| *A cool sequestered Spot | 32 |

| A Tour in the Toy Country (Harz Mountains) | 33 |

| A Mountain Beer Garden | 34 |

| A Fraulein | 35 |

| A Mountain Path | 35 |

| A Warrior of Sedan in a Beer Garden at Goslar, 1872 | 36 |

| The Ark of Refuge | 37 |

| *The Dance of Witches | 38 |

| Spectres of the Brocken | 39 |

| A Sketch at Supper | 40 |

| Back to the View | 40 |

| The Guide at Goslar | 41 |

| Procession of the Sick | 42 |

| Drinking the Waters at Goslar | 43 |

| A General in the Prussian Army | 44 |

| *A School on the March—Harz Mountains, 1872 | 45 |

| Sketch—Harz Mountains, 1872 | 46 |

| Sketch—Harz Mountains, 1872 | 48 |

| At Clausthal | 49 |

| *Sketch | 50 |

| Sketch in "Punch," 8th March, 1873 | 51 |

| A Check | 53 |

| Sketch (Published in Pall Mall Gazette) | 55 |

| Looking out for the "Graphic" Balloon | 57 |

| Off to the Exhibition—Vienna, 1873 | 59 |

| *A Viennese Dog | 60 |

| Sketch (Published in Pall Mall Gazette) | 62 |

| [Pg xiii] *Early Decorative Design | 64 |

| This is not a First-class Cow | 66 |

| *Studies for a large Decorative Design, 1874 | 67 |

| The Polling Booth (Pictorial World) | 70 |

| *Home Rule—March 1874 | 71 |

| On the Stump | 72 |

| The Scotch Elections—Going to the Hustings | 73 |

| Pairing Time | 74 |

| Coursing | 75 |

| Her First Valentine | 76 |

| A Valentine | 76 |

| Somebody's Coming! | 77 |

| I wonder who sent me these Flowers | 78 |

| The young Hamlet | 79 |

| House of Commons, March 1874—Arrival of New Members | 80 |

| The Speaker going up to the Lords | 81 |

| At the Bar of the House of Lords | 82 |

| The New Prime Minister | 83 |

| The Tichborne Trial—Breaking-up Day | 84 |

| The Morning Walk | 86 |

| *Decorative Painting for a Dining-room | 89 |

| *The Cottage, Farnham Royal | 90 |

| *Sketch from The Cottage, Farnham Royal | 91 |

| *Bringing Home the Sultanas | 92 |

| *The Paddock, Farnham Royal | 93 |

| *Studying from Nature | 95 |

| Sketch (Published in Pall Mall Gazette) | 96 |

| Sketch (Published in Pall Mall Gazette) | 97 |

| *Drawing from Familiar Objects | 98 |

| *Could not Draw a Lady! | 99 |

| Headpiece (Old Christmas) | 100 |

| The Stage Coachman | 103 |

| In the Stable Yard | 104 |

| The Troubadour | 106 |

| [Pg xiv] The Fair Julia | 107 |

| Master Simon and his Dogs | 109 |

| On the Road Side, Brittany | 111 |

| *At Guingamp, Brittany | 113 |

| *To M. H.—Christmas, 1874 | 114 |

| *Facsimile of Letter | 116 |

| *St. Valentine's Day | 117 |

| *At Farnham Royal | 118 |

| *Sunrise | 119 |

| *Diagram. Study in Line | 120 |

| *Diagram. Study in Line | 120 |

| *Diagram. Design for a Picture, 1875 | 121 |

| *Diagram. A Mad Dog | 122 |

| *Diagram. The Lecturer | 123 |

| Diagram. Child | 124 |

| Diagram. Mad Dog | 125 |

| *Sketch | 127 |

| *Shows his Terra Cottas | 129 |

| *The First Year of Academy Notes | 130 |

| *Three Pelicans and Tortoise | 131 |

| *Inspecting Embroideries | 132 |

| *Freshwater, Isle of Wight | 132 |

| *A Christmas Card to K. E. B. | 133 |

| Opinions of the Press (Manchester Quarterly) | 134 |

| There were Three Ravens sat on a Tree | 135 |

| *Private view of my First R.A. Picture | 136 |

| *A Horse Fair in Brittany | 137 |

| Captain Burton | 139 |

| Preface 1 Bracebridge Hall | 140 |

| Preface 2 Bracebridge Hall | 140 |

| The Chivalry of the Hall prepared to take the Field | 141 |

| The Fair Julia and her Lover | 143 |

| General Harbottle at Dinner | 144 |

| An Extinguisher | 145 |

| [Pg xv] *At Whitchurch | 146 |

| At Buxton | 147 |

| *A Christmas Card | 148 |

| Gaming Tables at Monte Carlo (Graphic) | 151 |

| Priest and Player (Graphic) | 153 |

| The Priest's Servant (North Italian Folk) | 155 |

| The Husbandman | 157 |

| Gossip | 158 |

| Dignity and Impudence (National Gallery) | 160 |

| Spaniels, King Charles's Breed | 160 |

| Portrait of a Lawyer by Moroni | 161 |

| *Waiting for a Boat | 163 |

| *Tailpiece | 164 |

| *Cleopatra | 165 |

| The Three Huntsmen (L'Art) | 167 |

| A Boar Hunt (Grosvenor Notes) | 168 |

| The Trap (Breton Folk) | 170 |

| Sketching under Difficulties | 171 |

| Breton Farmer and Cattle | 172 |

| A Wayside Cross | 173 |

| At the Horse Fair, Le Folgoet | 174 |

| Trotting out Horses at Carhaix | 175 |

| Cattle Fair at Carhaix | 176 |

| A Typical Breton | 177 |

| A Bretonne | 178 |

| *Sketch | 179 |

| A Cap of Finisterre | 180 |

| Returning from Labour—Pont Aven, 1878 | 181 |

| A Breton | 183 |

| *A Family Horse | 184 |

| *Sketch in Woburn Park | 185 |

| *A Carnation | 186 |

| *Hotel Gray et d'Albion, Cannes | 189 |

| *At Mentone | 190 |

| [Pg xvi] *Sketch | 191 |

| Sketch | 192 |

| Not such Disagreeable Weather after all—some People Think (from Punch) | 193 |

| *A Pig of Brittany | 194 |

| *A Bookplate | 195 |

| *Sketch | 196 |

| *Sketch | 197 |

| *Facsimile of Letter | 199 |

| Sketch | 200 |

| Sketch of Wybournes | 201 |

| *A New Year's Greeting | 203 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| *Headpiece. Caldecott's Picture Books | 212 |

| Æsop's Fables | 214 |

| A Sketch Book | 215 |

| Breton Folk | 216 |

Randolph Caldecott, the son of an accountant in Chester, was born in that city on the 22nd of March, 1846, and educated at the King's School, where he became the head boy. He was not studious in the popular sense of the word, but spent most of his leisure time in wandering in the country round. Thus, his love of sport and fondness for rural pursuits, which never forsook him, were evidenced at an early age. His artistic instincts were also early developed, and many treasured[Pg 2] sketches, models of animals, &c., cut out of wood, were produced in Chester by the boy Caldecott.

Perhaps the best and most characteristic record of his early life is, that he and his brother were "two of the best boys in the school;" the genius that consists in "an infinite faculty for taking pains" having much to do with his after career of success.

In 1861 Caldecott was sent to a bank at Whitchurch in Shropshire, where, for six years, he seems to have had considerable leisure and opportunity for indulging in his favourite pursuits. Here, living at an old farm-house about two miles from the[Pg 3] town, he used to go fishing and shooting, to the meets of hounds, to markets and cattle fairs, gathering in a store of knowledge useful to him in after years. The practical, if half-unconscious, education that he thus obtained in his "off-time," as he termed it, whilst clerk at the Whitchurch and Ellesmere Bank, was often referred to afterwards with pleasure. Thus from the earliest time it will be seen that he lived in an atmosphere favourable to his after career. But the bank work was never neglected; from the day he left his school in Chester in 1861 to become a clerk in Whitchurch, until the spring of 1872 when he left Manchester finally for London, the record of his office work was that he "did it well."

During the Whitchurch days he had, as we have indicated, unusual advantages of leisure, and the opportunity of visiting many an old house and farm, driving sometimes on the business of the bank, in his favourite vehicle, a country gig, and "very eagerly," writes one of his fellow clerks and intimate friends, "were those advantages enjoyed. We who knew him, can well understand how welcome he must have been in many a cottage, farm, and hall. The handsome lad carried his own recommendation. With light brown hair falling with a ripple over his brow, blue-grey eyes shaded by long lashes, sweet and mobile mouth, tall and well-made, he joined to these physical advantages a gay good humour and a charming disposition. No wonder that he was a general favourite."

But soon he was transferred to Manchester, where a very different life awaited him—a life of more arduous duties—in the "Manchester and Salford Bank,"[Pg 5] but with opportunities for knowledge in other directions, of which he was not slow to avail himself. If in his early years his father discouraged his artistic leanings, he was now in a city which above all others encouraged the study of art—"as far as it was consistent with business." In the Brasenose Club, and at the houses of hospitable and artistic friends in Manchester, Caldecott had exceptional opportunities of seeing good work, and obtaining information on art matters.

One who knew him well at this time, writing in the Manchester Courier of Feb. 16th, 1886, says:—

"Caldecott used to wander about the bustling, murky streets of Manchester, sometimes finding himself in queer out-of-the-way quarters, often coming across an odd character, curious bits of antiquity and the like. Whenever the chance came, he made short excursions into the adjacent country, and long walks which were never purposeless. Then[Pg 6] he joined an artists' club and made innumerable pen and ink sketches. Whilst in this city so close was his application to the art that he loved that on several occasions he spent the whole night in drawing."

For five years, from 1867 to 1872, Caldecott worked steadily at the desk in Manchester, studying from nature whenever he had the chance in summer; and at the school of art in the long evenings, sometimes working long and late at some water colour drawing. Caldecott owed much to Manchester, as he often said, and he never forgot or undervalued the good of his early training. The friends he made then he kept always, and they were amongst his dearest and best.

In Manchester on the 3rd of July, 1868—his first drawings were published in a serio comic paper called Will o' the Wisp; and in 1869, in another paper called The Sphinx, he had several pages of drawings reproduced. He was painting a little at the same time, making many hunting and other studies; they were chiefly for friends, but one picture was exhibited at the Manchester Royal Institution in 1869.

"Consider, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury, the sad

position in which my Client is placed—deserted by his Wife and left to

support himself and tender Infant by his own Exertions."

"Consider, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury, the sad

position in which my Client is placed—deserted by his Wife and left to

support himself and tender Infant by his own Exertions."

There was no restraining Caldecott now, his artistic bent and his delightful humour were finding expression in sketches in odd hours and minutes, on bits of note paper, on old envelopes, and on the blotting paper before him at his desk, until everybody about him must have been alive to his talent. He might no doubt have eventually attained a good position in the bank, for, as one of his friends writes of him very truly,

"Caldecott's ability was general, not special. It found its natural and most agreeable outlet in art and humour, but everybody who knew him, and those who received his letters, saw that there were perhaps[Pg 10] a dozen ways in which he would have distinguished himself had he been drawn to them."

The unpublished sketches dispersed through this chapter indicate but slightly the originality and fecundity of Caldecott's genius at this time.

"This is not a Culprit going to gaol—it is only a

Gentleman in love who happens to be walking before a Policeman!"

"This is not a Culprit going to gaol—it is only a

Gentleman in love who happens to be walking before a Policeman!"

There was clearly but one course to pursue—to give up commercial pursuits and go to London—if such sketches as these were to be found scattered amongst bank papers!

And so, in May, 1870, Caldecott, as his diary records, went to London for a few days with a letter of introduction to Mr. Thomas Armstrong from Mr. W. Slagg; and in the same year, 1870, some of his drawings were shown to Shirley Brooks, and to Mark Lemon, then editor of Punch. Mr. Clough thus records the event:—

"Bearing an introductory letter he went up to London on a flying visit, carrying with him a sketch on wood and a small book of drawings of the 'Fancies of a Wedding.' He was well received. The sketch was accepted, and with many compliments the book of drawings was detained.

"'From that day to this,' said Mr. Caldecott, 'I have not seen either sketch or book.' Some time after, on meeting Mark Lemon, the incident was recalled, when the burly, jovial editor replied, 'My dear fellow, I am vagabondising to-day, not Punching.' I don't think Mr. Caldecott rightly appreciated that joke."

From this date and all through the year 1871, Caldecott was at work in Manchester and sending to London drawings, some of which have hardly been exceeded for humour and expression in a few lines.

It was in February 1871, in the pages of London Society—a magazine which at that time included amongst its contributors J. R. Planché, Shirley Brooks, Francis T. Palgrave, Frederick Locker, G. A. Sala, Edmund Yates, Percy Fitzgerald, F. C. Burnand, Arthur à Beckett, Tom Hood, Mortimer[Pg 14] Collins, Joseph Hatton, &c.; and amongst its artists Sir John Gilbert, Charles Keene, Linley Sambourne, G. Bowers, Mrs. Allingham, W. Small, F. Barnard, F. W. Lawson, M.E.E., and many other notable names—that Caldecott made his first appearance before a London public.

On November 3rd, 1870, his diary says:—

"Some drawings which I left with A. in London have been shown, accompanied by a letter from Du Maurier, to a man on London Society. Must wait a bit and go on working—especially studying horses, A. said."

From this parcel of Caldecott's drawings the present writer, being the "man" referred to, selected a few to be engraved; the sketch of the Rt. Hon. Robert Lowe on horseback in Hyde Park, on page 17, "Ye monthe of Aprile" and "Education under Difficulties" being amongst the first published.

It was suggested to him early in 1870 that he should come to London for a short time and make[Pg 16] sketches in Hyde Park, and it touched Caldecott's fancy, (as he often mentioned afterwards,) that he whose experiences were far removed from such scenes should have been chosen as a chronicler of "Society." The sketches were made always from his own point of view, and some were so grotesque, and hit so hard at the aristocracy, that they were[Pg 17] found inappropriate to a fashionable magazine!—one especially of Hyde Park in the afternoon, called "Sons of Toil," had to be declined by the Editor with real regret.

The packet of original sketches lies before the writer now; the pen and ink drawing of "The Chancellor of the Exchequer" is dated June 3rd,[Pg 18] 1870. But the best and funniest of these early works could not be published in a magazine.

For Christmas time, 1871, Caldecott made many sketches. Two were to illustrate a short story called "The Two Trombones," by F. Robson, the actor. It was a ridiculous story, bordering on broad farce, depicting the adventures of Mr. Adolphus Whiffles, a young man from the country, who in order to get behind the scenes of a theatre undertakes to act as a substitute for a friend as "one of the trombones," unknown to the leader of the orchestra. His friend[Pg 19] assures him that in a crowded assembly "one trombone would probably make as much noise as two," and that, if he took his place in the orchestra, he had only to "pretend to play and all would be right."

In the first sketch we see him in his bedroom contemplating the unfamiliar instrument left by his friend; in the second he is at the theatre at the crisis when the leader of the band calls upon him to "play in" (as it is called) one of the performers on to the stage! Mr. Whiffles's instructions were[Pg 20] to keep his eyes on the other trombone and imitate his movements exactly; but unfortunately the other trombone was a substitute also. The leader looks round, and seeing the two trombones apparently perfectly ready to begin, gives the signal, and the curtain rises. The dénoûment may be imagined! Other stories were illustrated by Caldecott, about this period, in London Society; one of Indian life, another called Crossed in Love, &c., but the artist wished that some illustrations should not be reprinted. Several drawings from London Society are omitted, from the same cause.

The freshness of fancy, not to say recklessness of style, in many of the drawings which came by post at this time—the abundance of the flow from a stream, the course of which was not yet clearly[Pg 22] marked—raised embarrassing thoughts in an editor's mind. "What to do with all the material sent?" was the question in 1871—a question which Caldecott was soon able to answer for himself.

In 1871, many favourable notices appeared in the press referring to the humorous illustrations in London Society; but the sketch of all others which attracted attention to the work of the unknown artist was "A Debating and Mutual Improvement Society" on page 21, a recollection probably of some meeting or actual scene in Manchester.[1] Here the artist was on his own ground,[Pg 23] and the result is one of the most rapid and spontaneous sketches in pen and ink ever achieved. It had many of the characteristics of his later work, a lively and searching analysis of character, without one touch of grossness or ill-nature—fun and satire of the subtlest and the kindliest. Here was the touch of genius unmistakable, an example of expression in line seldom equalled.

In an altogether different vein, drawing with pen, and a brush for the tint,—the new artist tries his hand at illustrating one of Mortimer Collins's madrigals called "Heigh-ho, the Holly!"

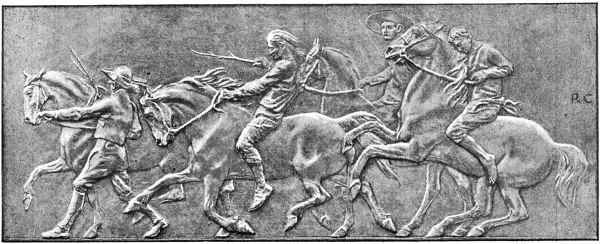

Amongst the most ambitious and interesting of Caldecott's drawings at this time were his "hunting and shooting friezes," of which several examples will be found in the pages of London Society for 1871 and 1872, drawn in outline with a pen; showing, thus early, much decorative feeling and a liking for design in relief which never left him in after years.

Two of the best that he did were the hunting subjects, entitled "Going to Cover" and "Full Cry."

"The Coming of Age of the Pride of the Family"[Pg 26] is another example, in a different style, of Caldecott's drawing in line at this period. It is reproduced opposite, in exact facsimile from the pen and ink drawing in possession of the writer.

Trivial as these things may seem now, the arrival in Manchester of the red covers of London Society containing almost every month something new by R. C., were among the events in the life of the young banker's clerk which soon set the tide of his affairs towards London.

Referring to drawings made for the magazine after Midsummer 1872, when Mrs. Ross Church succeeded to the editorship, Caldecott writes to a friend:—

"Florence Marryat wants me to illustrate a novelette, very humorous, to run through five or six numbers of London Society, beginning in February. Engraved illustrations, no 'process.' I think I shall do them, I want coin!"

But he had soon other work in hand as will be seen in the next chapter.

Early in the year 1872 Caldecott left Manchester for London, "bearing with him the well wishes of the Brazenose Club and of an extensive circle of friends." This great change was not decided upon without considerable hesitation; but, to quote again from a Manchester letter:—

"Caldecott was greatly encouraged to take this step by the sale of some small oil and water colour paintings at modest prices, and by the acceptance of drawings by London periodicals. The clinking of sovereigns and the rustling of bank-notes became[Pg 30] sounds of the past—the fainter the pleasanter, so at least Caldecott thought at that time, with energy, ardour, and the world before him."

In February and March, 1872, he was still drawing for the magazines and illustrating short stories.

In March, 1872, he exhibited hunting sketches in oil at the Royal Institution, Manchester.

On the 16th April he went to the Slade School to attend the Life Class under E. J. Poynter, R.A., until the 29th June.

As this was the turning point in Caldecott's career, it should be recorded that at this time, and ever afterwards, Mr. Armstrong, the present Art Director at the South Kensington Museum, was his best friend and counsellor.[2] He had also the advantage of the friendship of George du Maurier, M. Dalou, the sculptor, Charles Keene, Albert Moore, and others.

On the 8th June he records, "A. urged me to prepare caricatures of people well known," probably with the view of making drawings for periodicals.

Several drawings of Caldecott's were under consideration by the proprietors of Punch, and on the 22nd June, 1872, the first appeared.

In the same month he exhibited a frame of four small sepia drawings at the Black and White Exhibition, Egyptian Hall, London.

On the 28th June his diary records, "in the gallery of the House of Commons attending the debate on the Ballot Bill;" and again on the 8th July. On the 9th he is "engaged on chalk caricatures all day."

A letter dated 21st July, 1872, to one of his Manchester friends is worth having for the ludicrous sketch accompanying it. He writes:—

"London is of course the proper place for a young man, for seeing the manners and customs of society, and for getting a living in some of the less frequented grooves of human labour, but for a residence give me a rural or marine retreat. I sigh for some 'cool sequestered spot, the world forgetting, by the world forgot.'"

About this time it was suggested to him to illustrate a book of summer travel, and on the 20th August 1872 he enters in his diary:—

"To Rotterdam, Harzburg, &c., to join Mr. and Mrs. B. in the Harz Mountains."

This was the first book that Caldecott illustrated;[3] the[Pg 34] title suggested was "A Tour in the Toy Country," and before leaving London he made the drawing on the preceding page. Caldecott, being then twenty-six, started on this journey with great readiness. The idea was altogether delightful to him; and here, as in every country he visited in after years, his playful fancy and facility for seizing the grotesque side of things stood him in good stead.

In a strange land, amidst unfamiliar scenes and faces, he roamed "fancy free"; in a country so compact in size that the whole could be traversed in a month's walking tour.

With Baedeker's Guide (English edition) in his pocket, and a dialogue book of sentences in[Pg 35] German and English, he used to delight to interrogate the wondering natives; the necessary questions difficult to find, and "the elaborate and quite unnecessary" (as he expressed it), always turning up. Such little incidents gave opportunity to the observant artist to study the faces of the listeners; the interviews conducted slowly and gravely, and ending in a peal of laughter from the natives.

Life at a German watering-place, as seen on a small scale in summer in the Harz mountains, was Caldecott's first experience of scenes with which his name afterwards became familiar in the pages of the Graphic newspaper. In looking at these early sketches we must bear in mind that they were made at a time when Caldecott, as an "artist," was scarcely two years old; that although his sense of humour was overflowing, his hand was comparatively untrained; that with his keen eye for the grotesque he turned his back upon much that was beautiful about him, that his sense of the fitness of things, of the requirements of composition and the like, were in embryo, so to speak.

Nevertheless, as indicated in the next few pages[Pg 37] he has left us work which, if ever a more complete life of Caldecott should be written, would form an important chapter in his art career.

Although little fitted for a mountaineer, he could not resist excursions to the highest points, and with a will which surmounted all difficulties, reached one evening the summit of the famous "Brocken." What he saw is recorded in the sketch below.

There is a legend that when the deluge blotted out man from most parts of the earth, the waters of the northern seas penetrated far into Germany, and that the enormous rock which forms the top of the Brocken formed a shelter and resting-place.

There was no need of a romantic legend to suggest to the mind, at the first sight of the primitive hostelry on the top of the Brocken, its[Pg 38] similitude to the "ark of refuge." The situation was delightful; we were in the "toy country" without doubt. There was the identical form of packing-case which the religious world has with one consent provided as a plaything for children; there were Noah and his family, people walking two and two, and horses sheep, pigs, and goats stowed away at the great side door.

The resemblance was irresistible, and more attractive to Caldecott's mind than any of the legends and mysteries with which German imagination has peopled the district.

There is "no holding" Caldecott now; on the[Pg 39] "Hexen Tanzplatz," the sacred ground of Goethe's poetic fancy, within sound almost of the songs of the spirit world that haunt this lonely summit, he sets to work.

The dance of witches, so weird and terrible, (as lately seen on the Lyceum stage in Henry Irving's production of Faust) took a different form in the young artist's eyes, whose fancy sketch from the Hexen Tanzplatz is reproduced opposite. He had been properly "posted," as he expressed it, he had[Pg 40] read all that should be read about ghosts, witches, and spectres, and the result is before us. The last sketch from the dreary summit, showing the patient tourists waiting to see the view, was all we could get from him of spectres of the Brocken.

One or two sketches of the interior of his Noah's ark, when some sixty travellers had assembled to supper, completed his subjects.

It may be noted that the feeling for landscape which Caldecott possessed in after years in such a[Pg 41] high degree, if it touched him here, was not recorded in pencil. The magnificent scenery eastward through the valley of the River Bode, the grim iron foundries and ochre mines, and the wonderful view from the heights above Blankenberg, familiar to all travellers in the Harz, was recorded in only two sketches; one of a roadside inn, where we were invited to stay, the other of two tourists en route.

How, at the little wayside sheds and "drink gardens" scattered on the mountain paths, the tourists sat persistently back to the view which they had toiled miles to see, were depicted by the artist in pencil, and many little incidents on the road were dotted down for future use.

In the old tenth-century city of Goslar, Caldecott's pencil was never at rest. Taking a guide to save time (whose portrait he gives us, with a note of a[Pg 42] curious sixteenth-century street door) he explores from morning to night, choosing as subjects always "the life of the place."

"Drinking the waters at Goslar" in 1872 was a crude effort artistically, which may be contrasted with his sketches of the same scenes at Buxton in 1876, but the humour is irresistible. An extract from our diaries is necessary here to explain the illustration.

"The figures are pilgrims, that have come from far and wide to combine the attractions of a summer holiday with the benefits of a wonderful 'cure' for which the city is celebrated. The promenades and walks on the ramparts lined with trees, are going through the routine of getting up early, taking regular exercise and drinking daily several pints of a dark mixture having the appearance, taste, and effect of taraxacum or senna. The bottles are supplied at the public gardens and cafés situated at convenient distances in the suburbs of Goslar."

On another day he encounters a school starting for two or three days on the mountains, the band making hideous noises as the procession passes out of Goslar. Everything is characteristic here and full of local colour; the order of march, the costumes and the boots of the boys, and the general gravity of the company are given exactly—making the usual allowance for exaggeration. In the background is seen one of the iron factories and an indication of a bit of Harz scenery; the sketch recalling the incident with wonderful vraisemblance. The "School on the March" in its humour and exaggeration may remind the reader of some drawings by Thackeray.

Here, as in Belgium, the harnessing of dogs to carts, drawing sometimes two people over the rough cobble stones of Goslar, excited Caldecott's pity and anger; he made several sketches of the animals and one portrait of their master who had just got down to enjoy a pipe at the corner of a street.

Sketches at various table d'hôtes in hotels, public gardens and the like, were plentiful and perpetual. But the majority were destroyed or put away; out of fifty only one such as "A General in the Prussian Army" (see page 44) being selected for reproduction.[4]

At Clausthal we joined a party to explore one of the iron mines, and Caldecott gives a sketch of the[Pg 47] preparations. A note from our diary will best explain the situation.

"In order to descend the mines at Clausthal, visitors have to divest themselves of their ordinary costumes and put on some cast-off suits of ill-fitting garments left at the entrance to the mine for the purpose. As we approach the mouth of the shaft where the miners are waiting with lanterns to commence the descent, our party,—consisting of four Englishmen—a professor of geology, a director of mines, an editor and an artist—present the somewhat undignified aspect in the sketch. This change of costume is necessary on account of the wet state of the mines, the thick caps being a protection against loose pieces of ore and the wet earth that falls from time to time in the galleries."

Caldecott gives the generally dismal and disreputable appearance of the party with great verve; his own portrait is presented in a few touches in the background, hurrying into garments much too big for him.

On one occasion the artist takes a solitary walk between Thale and Clausthal, a pathway lined in[Pg 48] some parts by rows of trees with forbidden fruit, a novel and tempting experience. There being no mention of this route in the guide books, he writes as he says his "own Baedeker" in the familiar practical manner:—

"I start at 3.40 P.M. from the 'Tenpounds Hotel' at Thale to walk up the valley of the Bode, over a wooden bridge, then through a beer garden, round a rocky corner," &c. "The way next through woods of beech, birch and oak; a stream can be heard but not seen. Treseburg is reached at 5.40; a prettily situated village by the water side; homely inn, damp beds."

"Leave Treseburg at 9.40 A.M. over a bridge on the right bank of the Bode. Altenbrack at 10.50, Wendefurth at 11.50. Rubeland reached at 2.30 P.M., and so on to Elbingerode, where a halt is made for the night at the 'Blauer Engel,' a tolerable inn. Women of burden and foresters are the only wayfarers met with.

"The route hence south-west over high open[Pg 49] land with fine views to the iron works of Rothehütte in an hour. Thence up a hill for half an hour and through dense fir woods, then out on the high road again, resting at the 'Brauner Hirsch' at Braunlage. From thence over hills commanding a vast extent of country with the familiar form of the Brocken continually in view. The road descends by easy stages through a district full of small reservoirs and leads the traveller in about two hours into the wide, clean, empty streets of Clausthal."

On the 19th September, 1872, Caldecott is at work again in his rooms at 46, Great Russell Street (opposite the British Museum) arranging with the writer for some of his Harz Mountain drawings to accompany an article in the London Graphic newspaper. These appeared in the autumn of 1872.

On the 18th October, the following entry appears in Caldecott's diary: "Called at Graphic office, saw Mr. W. L. Thomas, who took my address."[Pg 50] This entry is interesting as the beginning of a long connection with the Graphic newspaper which proved mutually advantageous.

In November, 1872, the present writer went to America, taking a scrap-book of proofs of the best of Caldecott's early drawings, a few of which were published in an article on the Harz Mountains in Harper's Monthly Magazine in the spring of 1873.[5] His drawings were also shown to the conductors of the Daily Graphic, of New York, which led to an engagement referred to in the next chapter.

During the latter part of 1872 numerous small illustrations were produced for London Society.

Some idea of the work on which Caldecott was engaged in 1873 and 1874, may be gathered from extracts from his diary in those years. They are interesting if only to show that at that early period his art studies were varied, and that his experience was not confined to book illustration as has generally been supposed.

In January, 1873, he made six illustrations for Frank Mildmay by "Florence Marryatt," and on January 22nd, an "Initial for Punch."

In February—

"Began wax-modelling for practice, hearing that my hunting frieze (white on brown paper) had been successful in Manchester, and that I should perhaps be asked to model some animals for a chimney-piece."

24th April.—"A. came to see my wax models; liked them, said I must do something further."

Several hunting subjects were also in progress at this time. Next are two letters to a friend in Manchester.

"My dear ——,—The ancient Romans said, or ought to have said, that ingratitude was the greatest of human crimes. But, my dear fellow, I am not an ingrate. I have not forgotten you—unless, as the poet sings, 'if to think of thee by day and dream of thee by night, be forgetting thee, thou art indeed forgot.' I did receive your last collected joke, and a very good joke it was—for a Manchester joke. I'm sorry that I have not power to use it, but it will keep, although it will tread on some people's feelings when used. The fact[Pg 54] is that this same joke nearly brought me to an untimely end. I went out hunting on the day I received it, and at one fence and ditch I had quite enough to do to avoid a rabbit-hole on the taking-off side and some barked boughs of fallen timber on the landing side—not to mention some low-hanging oak trees. Well, just when I was in the air I thought of your joke and smiled all down one side; my hunter—by King Tom, out of Blazeaway's dam, by Boanerges—took the opportunity of stumbling, and, before an adult with all his teeth could get as far as the third syllable in 'Jack Robinson,' my nose was engaged in cutting a furrow all across a fine grass field, some eight acres and a half in extent, laid down after fine crops of seeds and roots, and well boned last winter. However, in less than half a minute (having retained possession of the reins), I was again chasing the flying hounds.

"About the middle of February I went down into the country to make some studies and sketches, and remained more than a month. Had several smart attacks on my heart, a little wounded once, causing that machine to go up and down like a lamb's tail when its owner is partaking of the nourishment provided by a bounteous Nature. Further particulars in our next—no more paper now. I hope you and —— are well, and with kind regards, remain yours faithfully,

"My dear ——,—I was delighted to receive your letter—quite a long one for you. I hope that you had a fine time of it at the ball. Dancing is not absolutely necessary to a man's welfare temporally or spiritually; so if you be a 'Wobbler,' wobble away and fear not, but see that thou wobblest with all thy might, then shall thy zeal compensate for lack of skill. I've nearly given up gymnastics. I only danced twenty-one times at the last ball.

"I now find that during quadrilles my mind wanders away from the subject before it, and I am[Pg 56] continually reminded that I ought to be idiotically squaring away at some one instead of cogitating with my noble back leaning against the wall. 'Sed tempora new potater,' &c. I hope you are all well, and with kind regards, remain yours faithfully,

In May he is "working in clay in low relief."

6th June.—"Began modelling mare and foal in round."

In the latter part of June, and in July, he is "at Vienna with Mr. Blackburn," engaged on various illustrations for the Daily Graphic.

It was in the summer of 1873 that it occurred to the proprietors of the Daily Graphic (the American illustrated newspaper referred to) that the Gulf Stream, and the strong prevailing current of wind easterly from the continent of America in that latitude, might be turned to profitable account for advertising purposes. They constructed a large balloon which hung high above the houses in Broadway for some weeks, and announced that on a certain day the Daily Graphic balloon would sail for Europe. The start was telegraphed to London and gravely[Pg 57] announced in the Times and other London papers, and every one was on the qui vive for this new arrival in the air.

The humour and absurdity of the situation was seized at once by the comic journals, but probably nothing that appeared at the time was more telling than the drawing made by Caldecott at Farnham[Pg 58] Royal for the Daily Graphic, and published in New York as a page of that newspaper.

Other drawings followed, descriptive of various scenes in London and England, such as a special service by Cardinal Manning at the Pro-Cathedral in Kensington; an address by Bradlaugh at the east end of London; a London picture exhibition; hunting in a northern county, &c., and Caldecott, to whom all this was a new experience, was pleased to work for the American newspaper as "London artistic correspondent."

In this capacity Caldecott went with the writer to Vienna to the International Exhibition of 1873, and there were sent to America various satirical sketches, accompanying letters, notably one of the banquet held on the 4th of July, with portraits of some well-known American citizens. One of the most successful and life-like of the smaller sketches was a Vienna horse-car entitled—"Off to the Exhibition," reproduced here.

The experience gained in various excursions during Caldecott's engagement with the Daily Graphic, was most valuable to him in after years;[Pg 60] although as we have elsewhere said, illustrated journalism properly so-called, was never sympathetic to him, nor would his health have been equal to the strain of so trying an occupation. As occasional contributor to an illustrated newspaper he was destined to be without a rival, as the columns of the London Graphic for many years have testified.

The humour and vivacity, the abandon, so to speak, exhibited in some of these early drawings, form a delightful episode in his early art career, and many will wonder, looking at the variety of movement and expression (in the drawing of the overloaded car, for instance), that the artist should have been amongst us so long without more recognition. It is true that his drawings were[Pg 61] uncertain, and that the results of want of training were sometimes too palpable; that the accusation made in 1872 that the editor of London Society had chosen "an artist who could not draw a lady," could hardly be gainsaid in 1873.

The artistic interest in these drawings is great, if only from the fact that they are amongst the few of his works drawn in pen and ink for direct reproduction without the intervention of the wood-engraver. Caldecott was one of the first to try, and to avail himself of, the various methods of reproduction for the newspaper press; and in the pages of the Daily Graphic, his facile touch and play of line was made to appear with startling emphasis on the printed page.[6]

But after all, the humour and drollery of Caldecott's nature appears with more unrestrained effect in the sketches on his letters to friends, such as are scattered through this volume; the natural awe of publication in any form having a restraining effect.

In July and August he is working "in the loose box at Farnham Royal," the country cottage sketched on page 90 and referred to in the following and other letters.

"Dear ——,—The poet sings, 'Oh! have you seen her lately?' to which I answer, 'Yes.' But, whether or no, I returned to-day from a fortnight's sojourn in Buckinghamshire, and the first thing I was going to do was to write to you and say that I have no acquaintance with the happy medium who resides in my very old rooms in Great Russell Street. I have left those rooms, and am a wanderer and an Ishmaelite. I dare not take those rooms when she leaves. I called at the house just now and found another note from you. I had a good look at Europe during my Vienna expedition. I[Pg 63] was away a month and saw many towns, and conversed with many peoples and tongues. I could say much, but will defer till we meet over the flowing bowl. Since I came back I have been staying with a friend at Holborn Circus, and also with some friends at Farnham Royal, near Slough, a lovely country place. There I have been working off some sketches of Vienna and England for the use of the neighbouring country of America. But I could not help being interrupted. Fancy a being like this bobbing about! Howsomedever, I am again in town at Bank Chambers, Holborn Circus, E.C., where I may be consulted daily. Please observe signature on the box, without which none others are genuine, post free for thirteen stamps. So you see that I have had a seven weeks' delightful mixture of toil and pleasure, and ought now to have a bout of toil only. There is a book waiting to be illustrated.

In the same month (August 1873), he went with a letter of introduction to Dalou, the French sculptor, then living in Chelsea. Of this interview he writes, "M. Dalou very kind in hints, showing me clay, &c." A friendship followed, cemented in the first[Pg 64] instance by a bargain that Caldecott should come and work at the studio and teach the sculptor to talk English, whilst Dalou helped him in his modelling! Caldecott profited by the arrangement, and often spoke in after years of the value of Dalou's practical teaching. Many visits were paid to the sculptor's studio in the year 1873.

In the intervals of work Caldecott also made life studies at the Zoological Gardens in London, and anatomical studies of birds.

In September he made a drawing of Mark Twain lecturing in London, for the Daily Graphic, and in October records the purchase by Mr. G. Aitchison, the architect, of a cast of his "first bas relief," a hunting subject; also of "two brown paper pelican drawings," one reproduced on the last page.

In November he writes the following to a friend in Manchester:—

"Dear ——,—I have nothing to say to you—nothing at all. Therefore I write. I don't like writing when I have aught to say, because I never feel quite eloquent enough to put the business in the proper light for all parties. Having a love and yearning for Bowdon and Dunham, and the 'publics' which there adjacent lie, I think of you on these calm Sunday evenings about the hour when my errant legs used to repose beneath the deal of the sequestered inn at Bollington. How are you? I was pleased to see that the Athenæum gave a long space to your book, although I presume you did not care for the way they reviewed it. That is nothing. I have been very busy—not coining money, oh no!—but occupied, or I should say have descended into the country, during last month.[Pg 66] 'Graced with some merit, and with more effrontery; his country's pride, he went down to the country.' My summer rambles shall be talked of, and the wonderful works in the regions of art shall be described when next I see you. Till then, farewell! This short letter is like a call.—Yours, R. C."

The last entry of interest in his diary in 1873, is on December 3rd.

"To Graphic office, saw Mr. Thomas. Fixed that I should go down to Leicestershire next week for hunting subjects."

Let us now glance at Caldecott's diary for 1874, which, with his letters to friends and the sketches which so often accompanied them, give an insight into the character of his work at this time. It is altogether an extraordinary record.

On the 14th of January, 1874, he is "working in the afternoons, sketching swans at Armstrong's." This was part of a large decorative design which[Pg 68] he afterwards assisted in painting (see illustration on page 89).

On the 23rd January, 1874, is an interesting note.

"J. Cooper, engraver, came and proposed to illustrate, with seventy or eighty sketches, Washington Irving's Sketch Book. Went all through it and left me to consider. I like the idea."

In February he completed a drawing of the Quorn Hunt for the Graphic newspaper.

On the 12th March, he enters in his diary, "Preparing sketch of choir for W. Irving's Sketch Book;" showing that he was already at work on the book which was to make his reputation.

At the same time he was preparing illustrations and trying new processes of drawing for reproduction, to aid in founding a new newspaper.

How far Mr. Caldecott was ready to conquer difficulties in his art, and how heartily he aided his friends in any project with which he was connected, are matters of history closely connected with his engagement on the Pictorial World, which had a bright promise for the future in 1874.

Some of the large illustrations were produced by Dawson's "Typographic Etching" process. The drawings were made with a point on plates covered with a thin coating of wax, the artist's needle, as in etching, removing the wax and exposing the surface of the plate wherever a line was required in relief—"a fiendish process!" as Caldecott described it, but with which he succeeded in obtaining excellent results—better than any artist previously.

On the 7th of March, 1874, a new illustrated newspaper called the Pictorial World was started in London, of which the present writer was the art editor.

It was the time of the general election of 1874, when the defeat of Mr. Gladstone, the question of "Home Rule," and many exciting events were being recorded in the newspapers. Caldecott was asked to make a cartoon of the elections, and at once sat down and made the pencil sketch overleaf.

For some reason this drawing was not completed; but instead, a group of various election scenes was drawn by him and appeared in the Pictorial World.

There were numerous sketches combined on one page, three of which are reproduced here. The illustrations on pages 70, 72, 80, 81, 82, and 84 were drawn (generally under great pressure of time) with an etching needle on Dawson's plates. This was the beginning of what are now familiarly known as "process" drawings in newspapers, but the system of photographic engraving, now largely used, was not then perfected. In 1874 it would[Pg 71] have been impossible to reproduce rapidly in a newspaper, either the delicate lines of a pen and ink sketch, or such a pencil drawing as that given above.

Caldecott rendered valuable assistance at this time, and the early numbers of the paper are[Pg 72] worth having if only for the reproduction of his work. It is not generally known how many of the large illustrations in the Pictorial World were by his hand, or how much he was identified with the publication in the first days of its career.

Amongst the best illustrations by Caldecott for the newspaper at that period were sketches and[Pg 73] studies that he had made for pictures, selected from his studio; such for instance as "Coursing," "Somebody's Coming," and the "Morning Walk," on pp. 75, 77, and 86. The latter design was not drawn specially for the Pictorial World, but Caldecott made a drawing of it for the paper, which appeared in the number for 18th July, 1874.

From a bundle of sketches (some very pretty) of subjects connected with Saint Valentine, he[Pg 74] made a page for the same paper. These again, may seem small matters to record, but they are facts in the history of a life teeming with interest, and show that Caldecott's talent as an illustrator was revealed in 1874; that he was "invented," as the saying is, long before the publication of Washington Irving's Sketch Book.

On the 31st of October, 1874, Mr. Henry Irving made his first appearance in London as Hamlet, one of those occasions on which the theatre was crowded with critics and well-known personages. Caldecott, altogether inexperienced in such work, made several rough sketches, seizing the grotesque side "as far as he dared" as he said.

The trying nature of that performance, and the flitting about on the stage of the nervous anxious[Pg 78] figure, with the ever-present white pocket-handkerchief in his belt—will be remembered by many. Caldecott made the best sketch that he could from the left side of the dress-circle, the only position in the house that could be obtained for him.

In company with the writer, Caldecott made various sketches in the House of Commons, the Law Courts, the theatres, and the like. The first three sketches of the House of Commons—one showing "The Arrival of the New Members,"[Pg 79] another, "The Speaker going up to the Lords," and a third, "At the Bar of the House of Lords"—were amongst the funniest of the series. Others followed from week to week, such as "The new Prime Minister," on page 83. On one occasion he went down to Westminster Hall to see the Rt. Hon. Benjamin D'Israeli enter the House of Commons[Pg 81] as the new prime minister, and to a large illustration showing the north door of Westminster Hall (the architecture drawn by Mr. Jellicoe), he added the figures, a grotesque group of bystanders, presumably Conservatives, welcoming their new representative. (See the Pictorial World, March 7th, 1874.)

It was an exciting time politically and socially, and many events of interest had to be recorded. Amongst them the conclusion, amidst general rejoicing, of the great Tichborne Trial on March 2nd, 1874, a trial which had lasted 188 days.[Pg 83] This was an opportunity for the artist. Caldecott's original sketch of this subject, if it is in existence, should be treasured; some idea of the humour of it may be gathered from the drawing overleaf which was crowded into the corner of the newspaper. He also made a highly grotesque and artistic model in terra-cotta of the Tichborne Trial, now in the possession of Mr. Stanley Baldwin of Manchester.

About this time, Caldecott went to the "farewell benefit" of the late Benjamin Webster and sketched the actor—surrounded by members of his company—making his final bow to the public.

On the eighteenth birthday, the "coming of age," of the late Prince Imperial of France, Caldecott went to Chislehurst. The drawing of the crowd on the lawn of Camden House in a state of general[Pg 85] congratulation, the ceremony of presentation of enormous bouquets of violets and the like; of Frenchmen and their wives, of diplomatists, and others, will be found in the Pictorial World for March 21st, 1874.

Here was a comparatively unknown artist at work, revealing talent which in after years would delight the world.

But fortunately for his health and peace of mind, and also for his future career, the young artist, who two years before had given up a clerkship in a Manchester bank (a "certainty" of more than £100 a year), was advised to refuse an engagement on the Pictorial World of £10 10s. a week, which, had it been carried out, would have done much to raise the fortunes of that newspaper.

But the rush and hurry of journalistic work was distasteful to him; he had many commissions at this time, work of a better kind, requiring quiet and study. He was willing, and wishing always, to aid his friends, and so for some time he kept up a connection with the paper and made sketches on special occasions.

His health was delicate, but he was not suffering as in later years; his spirits were overflowing, and his kindliness and personal charm had made him friends everywhere.

On the 10th of April he enters in his diary—"At Armstrong's all day. Began to paint pigeons on canvas panel. Looking at pigeons in British Museum quadrangle;" and on the 11th again, "painting pigeons."

On the 15th of April he is "making a drawing of storks, &c.," and on the 17th, 21st, and 22nd, "painting swans at Armstrong's all day."

On the 23rd of April he enters: "Bas-relief hunting scene going on," and on 24th, "painting storks and pigeons," and on 28th, "swans."

The painting of swans, storks, and pigeons, referred to above, was very important work for Caldecott. In conjunction with his friend Mr. Armstrong, he painted the birds in two panels, one of swans (reproduced overleaf), and one of a stork and magpie. These panels were about six feet high, and form part of a series of decorations in[Pg 88] the dining-room of Mr. Henry Renshawe's house at Bank Hall, near Buxton, Derbyshire.

The series of decorative paintings (by Thomas Armstrong) which included these panels, was exhibited at Mr. Deschamps' Gallery in New Bond Street in 1874, and attracted much attention at the time. The birds showed to great advantage, and will remain in the memory of many as amongst the most vigorous and effective of Caldecott's paintings in oils. They showed, thus early, a mastery of bird form and a power in reserve of an unusual kind.

"I have paid a little attention to decorative art," he writes to a friend at this time; besides being "at work on the Sketch Book," the results of which will be seen in the next chapter.

During the summers of 1872, 1873, and 1874, Caldecott stayed often at a cottage belonging to the writer, three miles north of Slough, in Buckinghamshire, in the picturesque neighbourhood of Stoke Pogis and Burnham Beeches.

A "loose box" adjoining the stable—a few yards to the right of the little verandah in the above sketch—had been fitted up for him by friendly hands; and it was here in this temporary studio,[Pg 91] in the quiet of the country, looking out on woods and fields, that he made many of the drawings for Old Christmas.

Several entries in Caldecott's diary in 1874 mention that in June and July he was "working in the 'loose box' at Farnham Royal, on the Sketch Book."

Those were happy, irresponsible days, before great success had tempered his style, or brought with it many cares. Take the following letter (one of many) written in the full enjoyment of the change from lodgings in London:—

"We are passing a calm and peaceful existence here and were therefore somewhat startled the other day, when Sharp asked for the cart and[Pg 92] donkey to take to the common for the purpose of bringing us a few Sultanas. We stroked our beards, but as Sharp seemed bent upon the affair reluctantly consented."

[The boy Sharp attended to the wants of Caldecott and his friend L., and wanted to make a pudding. The end of the letter is reproduced in facsimile.]

The illustration on the last page is a copy of a water-colour sketch made from "the loose box" at Farnham Royal. It depicts the arrival of a pony at the cottage and consequent disgust of the donkey at the intrusion. The old man—who combined the various offices of gardener, groom, and parish clerk—stood unconsciously as a model for several drawings in Old Christmas.

From Farnham Royal he writes at another time to a friend:—

"We are fast drifting into a vortex of dissipation—eddying round a whirlpool of gaiety; but I hope that through all, our heads will keep clear enough to guide the helms of our hearts."

About this time it was suggested to Caldecott to make studies of animals and birds, with a view to an illustrated edition of Æsop's Fables, a work for which his talents seemed eminently fitted. The idea was put aside from press of work, and when finally brought out in 1883 was not the success that had been anticipated. This was principally owing to the plan of the book.

As Caldecott's Æsop was often talked over with the writer in early days, a few words may be appropriate here. Caldecott yielded to a suggestion of Mr. J. D. Cooper, the engraver, to attach to each fable what were to be styled "Modern Instances," consisting of scenes, social or political, as an "application." Humorous as these were, in the artist's best vein of satire, the combination was felt to be an artistic mistake. That Caldecott was aware of this, almost from the first, is evident from a few words in a letter to an intimate friend where he says:[Pg 96]—

"Do not expect much from this book. When I see proofs of it I wonder and regret that I did not approach the subject more seriously."

Circumstances of health also in later years interfered with the completion of what might have been his chef d'œuvre.

In the following letter to a friend in Manchester (headed with the above sketch) he refers modestly to his drawings for Old Christmas, on which he was now busily engaged.

"My dear ——,—It is so long since I have heard from you that I have concluded that you must be very flourishing in every way. No news being good news, and no news lasting for so long a time, you must have a quiver full of good things. How is ——? The woods of Dunham? The gaol of Knutsford?—the vale of Knutsford, I mean. A fortnight ago, when all the ability were leaving town, I returned from a six weeks' pleasant sojourn in Bucks, at Farnham Royal. I was hard at work all the time, for I have been very much occupied of late, you will be glad to hear, I know. In process of time, and if successful, I will tell you upon what. I wish I had had a severe training for my present profession. Eating my dinners, so to speak. I have now got a workshop, and I sometimes wish that I was a workman. Art is long: life isn't. Perhaps you are now careering round Schleswig or some other-where for a summer holiday. I shall probably go to France next month for a business and pleasure excursion. Let me hear from you about things in general or in[Pg 98] particular—a line, a word will be welcome. I hope you are all well; and with kind regards remain

It is clear from the above letter that Caldecott was conscious of the great change that was coming in his work in 1874. The suggestions of his friends that he should draw continually from familiar objects, and the hints he received from time to time that he "could not draw a lady," are ludicrously illustrated in two sketches to a Manchester friend who watched the progress of the artist with lively interest.

But in spite of his moving laughter, the period referred to in this chapter was the most serious and[Pg 99] eventful in Caldecott's career; when a sense of beauty and fitness in design seemed to have been revealed to him, as it were, in a vision, and when his serious studies seemed to be bearing fruit for the first time; when he felt, as he never felt before, the responsibilities of his art and the want of severe training for his profession. Then—but not till then—did the lines of Punch "On the late Randolph Caldecott," written in February 1886, apply exactly:—

The "new departure" which Caldecott made in the summer of 1874 will be seen clearly marked in the next few pages, where, with the permission of the publishers, we have reproduced some characteristic drawings from Old Christmas.

"There was issued in 1876 by the Messrs. Macmillan" (writes Mr. William Clough, an old and intimate friend of Caldecott) "a book with[Pg 101] illustrations that forcibly drew attention to the advent of a new exponent of the pictorial art. These pictures were of so entirely new a nature, and gave such a meaning and emphasis to the text, as to stir even callous bosoms by the graceful and pure creations of the artist's genius. Washington Irving's Old Christmas was made alive for us by a new interpreter, who brought grace of drawing with a dainty inventive genius to the delineation of English life in the last century."

It is not generally known that the drawings for Old Christmas, one hundred and twelve in number, were all made in 1874; and there is a marked alteration in style during the progress of this book, such as, for example, between the drawing of "The Village Choir" (commenced in March 1874), and the portrait of "Master Simon," placed opposite to each other on pages 96 and 97 of the first edition of Old Christmas.

The humour is more robust, but never in after-work was more delightful, than in his rendering of the typical stage coachman. Until these illustrations came it had been said that Washington Irving's coachman stood out as a unique and matchless description of a character that has passed away.

"In the course of a December tour in Yorkshire," writes Washington Irving, "I rode for a long distance on one of the public coaches on the day preceding Christmas."

Three schoolboys were amongst his fellow-passengers. "They were under the particular guardianship of the coachman to whom, whenever an opportunity presented, they addressed a host of questions, and pronounced him one of the best fellows in the world. Indeed I could not but notice the more than ordinary air of bustle and importance of the coachman, who wore his hat a little on one side and had a large bunch of Christmas green stuck in the button-hole of his coat.

"Wherever an English stage coachman may be seen he cannot be mistaken for one of any other craft or mystery. He has commonly a broad full face, curiously mottled with red, as if the blood had been forced by hard feeding into every vessel of the skin; he is swelled into jolly dimensions by frequent potations of malt liquors, and his bulk is still further increased by a multiplicity of coats in which he is buried like a cauliflower, the upper one reaching to his heels. He wears a broad-brimmed low-crowned hat; a huge roll of coloured handkerchief about his neck, knowingly knotted and tucked in at the bosom, and has in summer-time a large bouquet of flowers in his button-hole, the present most probably of some enamoured country[Pg 103] lass. His waistcoat is commonly of some bright colour, striped; and his small clothes extend far below the knees to meet a pair of jockey-boots which reach about halfway up his legs.

"All this costume is maintained with much precision; he has a pride in having his clothes of excellent materials; and notwithstanding the seeming grossness of his appearance, there is still discernible that neatness and propriety of person which is almost inherent in an Englishman. He[Pg 104] enjoys great consequence and consideration along the road; has frequent conferences with the village housewives, who look upon him as a man of great trust and dependence; and he seems to have a good understanding with every bright-eyed lass. The moment he arrives he throws down the reins with something of an air, and abandons the cattle to[Pg 105] the care of the ostler; his duty being merely to drive from one stage to another. When off the box his hands are thrust in the pockets of his greatcoat, and he rolls about the inn yard with an air of the most absolute lordliness. Here he is generally surrounded by an admiring throng of ostlers, stable-boys, shoe-blacks, and those nameless hangers-on that infest inns and taverns and run errands. Every ragamuffin that has a coat to his back thrusts his hands in his pockets, rolls in his gait, talks slang, and is an embryo 'coachey.'"

Surely it has seldom happened in the history of illustration that an author should be so very closely followed—if not overtaken—by his illustrator. No literary touch seemed to be wanting from the author to convey a picture of English life and character passed away; but Caldecott's coachman helps to elucidate the text; and whilst it carried to many a reader of Old Christmas in the New World a living portrait of a past age, it revealed also the presence of a new illustrator.

Here was a reproachful lesson. The art of illustration—an art untaught in England and unconsidered by too many—was shown in all its strength and usefulness by a comparatively new hand.

Of the numerous illustrations drawn by Caldecott in 1874 for Old Christmas, we may select as examples the young Oxonian leading out one of his maiden aunts at a dance on Christmas Eve; and "the fair Julia" in the intervals of dancing listening with apparent indifference to a song from her admirer; amusing herself the while by plucking to pieces a choice bouquet of hothouse flowers.

The style and treatment of the drawing, on the opposite page, differs from anything previously done by Caldecott, and would hardly have been recognised as his work; the handling is less firm, and colour and quality have been more considered in deference[Pg 108] to what was considered the public taste in such matters. But in a few pages he emancipates himself again, and gives us some brilliant character sketches. In the last example from Old Christmas he is in his element. Nothing could be more characteristic, or in touch with the period illustrated, than the picture of Frank Bracebridge, Master Simon, and the author of Old Christmas, walking about the grounds of the family mansion "escorted by a number of gentleman-like dogs, from the frisking spaniel to the steady old staghound. The dogs were all obedient to a dog-whistle which hung to Master Simon's button-hole, and in the midst of the gambols would glance an eye occasionally upon a small switch he carried in his hand."[7] Thus the minute observation of the writer is closely followed by the illustrator, who here from his own habit of close observation of the ways of animals, was enabled to give additional completeness to the picture; and the effect was greatly heightened by a wise determination on the part[Pg 109] of Mr. Cooper the engraver, that the illustrations should be "so mingled with the text that both united should form one picture." This book was engraved at leisure, and not published until the end of 1875, by Messrs. Macmillan & Co., bearing date 1876.

It is interesting to note that Old Christmas was offered to, and declined by, one of the leading publishers in London; principally on the[Pg 110] ground that the illustrations were considered "inartistic, flippant and vulgar, and unworthy of the author of Old Christmas"! It was not until 1876 that the world discovered a new genius.

During the progress of the drawings for Old Christmas in 1874, Caldecott went with the writer to Brittany to make sketches for a new book; but the publication was postponed until after a more extended tour in 1878.

These summer wanderings of Caldecott in Brittany were prolific of work; his pencil and notebook were never at rest, as the pages of Breton Folk testify (see Chapter xi.). The drawings, both in 1874 and in 1878, mark a strong artistic advance upon similar work in the Harz Mountains. His feeling for the sentiment and beauty of landscape, especially the open land,—generally absent from the sketches in the Harz Mountains,—is noticeable here. The statuesque grace of the younger women, the picturesqueness of costume, operations of husbandry, outdoor fêtes and the like, and the open air effect of nearly every group of figures seen in these summer[Pg 111] journeys—all came as delightful material for his pencil.

Caldecott's studies with M. Dalou, the sculptor, in 1874, and the great proficiency he had already obtained in modelling in clay, enabled him to make several successful groups from his Brittany subjects.

The bright-eyed stolid child in sabots at the roadside (one of the first of the quaint little figures that attracted his attention in Brittany) stands on[Pg 112] the writer's table in concrete presentment in clay; the model is not much larger than the sketch—the front, the profile, and the back view, each forming a separate and faithful study from life.

The young mother and child in the cathedral at Guingamp (reproduced opposite) was another successful effort in modelling, but Caldecott was not satisfied with it excepting as a rough sketch—"a recollection in clay."

It is interesting here to note the handling of the artist in his favourite material, French clay. The model stands but six inches high, but it was intended to have reproduced it larger. Another sketch in the round was of "a pig of Brittany," reproduced on page 194.

"Save up," he writes about this time to a friend in Manchester, "and be an art patron; you will soon be able to buy some interesting terra cottas by R. C.!"

This was a heavy year, for many illustrations were produced not mentioned in these pages; and in October he was busy on the wax bas-relief of a "Brittany horse fair," afterwards cast in metal and exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1876 (see page 137).

On the 19th of November and following days Caldecott was "working at Dalou's on a cat crouching for a spring." He had a skeleton of a cat, a dead cat, and a live cat to work from. This model in clay was finished on the 8th December, 1874.

Christmas Eve was spent "in the caverns of the British Museum making a drawing, and measuring skeleton of a white stork." This was a most elaborate and careful record of measurements. On the 28th of December he was "engaged on brown paper cartoon of storks at Armstrong's," and on the 30th is the entry,—"at British Museum; had storks out of cases to examine insertion of wing feathers."

Thus, all through the year 1874 Caldecott, working without much recognition excepting from a few intimates, got through an immense amount of work; not forgetting his friends the children, to whom he sent many Christmas greetings with letters and coloured sketches. The drawing on the opposite page accompanied a kindly letter to a child of six years.

"I thank you," he says, "very much for your grand sheet of drawings, which I think are very nice indeed. I hope you will go on trying and learning to draw. There are many beautiful things waiting to be drawn. Animals and flowers oh! such a many—and a few people."

The last sketch in 1874—a postscript to a private letter—tells its own story.

In a letter to a friend in Manchester, on the 17th January, 1875, Caldecott writes:—

"I stick pretty close to business, pretty much in that admirable and attentive manner which was the delight, the pride, the exultation of the great chiefs who strode it through the Manchester banking halls. Yes, I have not forsaken those gay—though perhaps, to the heart yearning to be fetterless, irksome—scenes without finding that the world ever requires toil from those sons of labour who would be successful.

"However, during the last year I managed to do a lot of work away from town, and enjoyed it. Sometimes it was expensive, because when at the cottage in Bucks, we of course mixed with the county families and had to 'keep a carriage' to return calls, return from dinner, and so forth."

Here is "a meditation for the New Year"—

"You will excuse me," he says, "talking of myself when I tell you that amongst the resolutions for the New Year was one only to talk of matters about which there was a reasonable probability that I knew something. Now human beings are a mystery to me, and taking them all round I think we may consider them a failure. If I do not understand anything that belongs to myself, how can I understand what belongeth to another? This, my dear W., with your clear intellect, you will see is sound.

"I often think of the scenes and faces and jokes of banking days, and have amongst them many pleasant reminiscences. Perhaps we shall all meet again in that land which lies round the corner!"

[Here follows a grotesque sketch of a man on a winter's day, with an umbrella, hurrying off to the "Nag and Nosebag."]

At the beginning of 1875, in the intervals of book illustration, Caldecott was busy "working on a cartoon of storks." This was a design for a picture in oils, painted in March and afterwards bought by Mr. F. Pennington, late M. P. for Stockport.

On the 7th of January he enters in his diary, "Painted some storks on the wing for a panel for a[Pg 120] wardrobe." The rendering of dawn on the upmost clouds, the storks rising from the dark earth to greet the sun, can hardly be indicated without colour, but the design is given accurately. It was a poetic fancy which he had had in his mind for some time; one of many half developed designs which, if his health had permitted, the world might have seen more of.

On the 25th of January he "made a dry point sketch of a Quimperlé Brittany woman," and in February he was busy modelling as usual.

On the 5th of February, "took to Lucchesi (moulder) wax bas-relief of horse fair, and small 'sketch of brewers' waggon."

The advance of the art of reproducing drawings in facsimile in a cheap form, suitable for printing at the type press like wood engravings, was attracting much attention in England in 1875, and at the writer's request Caldecott made a series of diagrams suggestive[Pg 121] of the power of line and of effects to be obtained by simple methods, to illustrate a paper read before the Society of Arts in London in March, 1875, on "The Art of Illustration."

With his usual kindness and enthusiasm he put aside his work—some modelling in clay which he had been studying under his friend M. Dalou, the French sculptor—and at once began a diagram, about seven feet by five feet, to suggest a picture in[Pg 122] the simplest way. Without much consideration, without models, and in the limited area of his little studio in Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, he set to work with a brush on the broad white sheet, and in about an hour produced the drawing in line of "Youth and Age" on the last page.

The horses were not quite satisfactory to himself; but the sentiment of the picture, the open[Pg 123] air effect of early spring, the crisp grass, the birds' nests forming in the almost leafless trees, the effect of distance indicated in a few lines—and above all, the feeling of sky produced by the untouched background—were skilfully suggested in the large diagram.