The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 15, Slice 4, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 15, Slice 4

"Jevons, Stanley" to "Joint"

Author: Various

Release Date: October 14, 2012 [EBook #41055]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 15, SLICE 4 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

JEVONS, WILLIAM STANLEY (1835-1882), English economist and logician, was born at Liverpool on the 1st of September 1835. His father, Thomas Jevons, a man of strong scientific tastes and a writer on legal and economic subjects, was an iron merchant. His mother was the daughter of William Roscoe. At the age of fifteen he was sent to London to attend University College school. He appears at this time to have already formed the belief that important achievements as a thinker were possible to him, and at more than one critical period in his career this belief was the decisive factor in determining his conduct. Towards the end of 1853, after having spent two years at University College, where his favourite subjects were chemistry and botany, he unexpectedly received the offer of the assayership to the new mint in Australia. The idea of leaving England was distasteful, but pecuniary considerations had, in consequence of the failure of his father’s firm in 1847, become of vital importance, and he accepted the post. He left England for Sydney in June 1854, and remained there for five years. At the end of that period he resigned his appointment, and in the autumn of 1859 entered again as a student at University College, London, proceeding in due course to the B.A. and M.A. degrees of the university of London. He now gave his principal attention to the moral sciences, but his interest in natural science was by no means exhausted: throughout his life he continued to write occasional papers on scientific subjects, and his intimate knowledge of the physical sciences greatly contributed to the success of his chief logical work, The Principles of Science. Not long after taking his M.A. degree Jevons obtained a post as tutor at Owens College, Manchester. In 1866 he was elected professor of logic and mental and moral philosophy and Cobden professor of political economy in Owens college. Next year he married Harriet Ann Taylor, whose father had been the founder and proprietor of the Manchester Guardian. Jevons suffered a good deal from ill health and sleeplessness, and found the delivery of lectures covering so wide a range of subjects very burdensome. In 1876 he was glad to exchange the Owens professorship for the professorship of political economy in University College, London. Travelling and music were the principal recreations of his life; but his health continued bad, and he suffered from depression. He found his professorial duties increasingly irksome, and feeling that the pressure of literary work left him no spare energy, he decided in 1880 to resign the post. On the 13th of August 1882 he was drowned whilst bathing near Hastings. Throughout his life he had pursued with devotion and industry the ideals with which he had set out, and his journal and letters display a noble simplicity of disposition and an unswerving honesty of purpose. He was a prolific writer, and at the time of his death he occupied the foremost position in England both as a logician and as an economist. Professor Marshall has said of his work in economics that it “will probably be found to have more constructive force than any, save that of Ricardo, that has been done during the last hundred years.” At the time of his death he was engaged upon an economic work that promised to be at least as important as any that he had previously undertaken. It would be difficult to exaggerate the loss which logic and political economy sustained through the accident by which his life was prematurely cut short.

Jevons arrived quite early in his career at the doctrines that constituted his most characteristic and original contributions to economics and logic. The theory of utility, which became the keynote of his general theory of political economy, was practically formulated in a letter written in 1860; and the germ of his logical principles of the substitution of similars may be found in the view which he propounded in another letter written in 1861, that “philosophy would be found to consist solely in pointing out the likeness of things.” The theory of utility above referred to, namely, that the degree of utility of a commodity is some continuous mathematical function of the quantity of the commodity available, together with the implied doctrine that economics is essentially a mathematical science, took more definite form in a paper on “A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy,” written for the British Association in 1862. This paper does not appear to have attracted much attention either in 1862 or on its publication four years later in the Journal of the Statistical Society; and it was not till 1871, when the Theory of Political Economy appeared, that Jevons set forth his doctrines in a fully developed form. It was not till after the publication of this work that Jevons became acquainted with the applications of mathematics to political economy made by earlier writers, notably Antoine Augustin Cournot and H. H. Gossen. The theory of utility was about 1870 being independently developed on somewhat similar lines by Carl Menger in Austria and M.E.L. Walras in Switzerland. As regards the discovery of the connexion between value in exchange and final (or marginal) utility, the priority belongs to Gossen, but this in no way detracts from the great importance of the service which Jevons rendered to English economics by his fresh discovery of the principle, and by the way in which he ultimately forced it into notice. In his reaction from the prevailing view he sometimes expressed himself without due qualification: the declaration, for instance, made at the commencement of the Theory of Political Economy, that “value depends entirely upon utility,” lent itself to misinterpretation. But a certain exaggeration of emphasis may be pardoned in a writer seeking to attract the attention of an indifferent public. It was not, however, as a theorist dealing with the fundamental data of economic science, but as a brilliant writer on practical economic questions, that Jevons first received general recognition. A Serious Fall in the Value of Gold (1863) and The Coal Question (1865) placed him in the front rank as a writer on applied economics and statistics; and he would be remembered as one of the leading economists of the 19th century even had his Theory of Political Economy never been written. Amongst his economic works may be mentioned Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (1875), written in a popular style, and descriptive rather than theoretical, but wonderfully fresh and original in treatment and full of suggestiveness, a Primer on Political Economy (1878), The State in Relation to Labour (1882), and two works published after his death, namely, Methods of Social Reform and Investigations in Currency and Finance, containing papers that had appeared separately during his lifetime. The last-named volume contains Jevons’s interesting speculations on the connexion between commercial crises and sun-spots. He was engaged at the time of his death upon the preparation of a large treatise on economics and had drawn up a table of contents and completed some chapters and parts of chapters. This fragment was published in 1905 under the title of The Principles of Economics: a Fragment of a Treatise on the Industrial Mechanism of Society, and other Papers.

Jevons’s work in logic went on pari passu with his work in political economy. In 1864 he published a small volume, entitled Pure Logic; or, the Logic of Quality apart from Quantity, which was based on Boole’s system of logic, but freed from what he considered the false mathematical dress of that system. In the years immediately following he devoted considerable attention to the construction of a logical machine, exhibited before the Royal Society in 1870, by means of which the conclusion derivable from any given set of premisses could be mechanically obtained. In 1866 what he regarded as the great and universal principle of all reasoning dawned upon him; and in 1869 he published a sketch of this fundamental doctrine under the title of The Substitution of Similars. He expressed the principle in its simplest form as follows: “Whatever is true of a thing is true of its like,” and he worked out in detail its various applications. In the following year appeared the Elementary Lessons on Logic, which soon became the most widely read elementary textbook on logic in the English language. In the meantime he was engaged upon a much more important logical treatise, which appeared in 1874 under the title of The Principles of Science. In this work Jevons embodied the substance of his earlier works on pure logic and the substitution of similars; he also enunciated 362 and developed the view that induction is simply an inverse employment of deduction; he treated in a luminous manner the general theory of probability, and the relation between probability and induction; and his knowledge of the various natural sciences enabled him throughout to relieve the abstract character of logical doctrine by concrete scientific illustrations, often worked out in great detail. Jevons’s general theory of induction was a revival of the theory laid down by Whewell and criticized by Mill; but it was put in a new form, and was free from some of the non-essential adjuncts which rendered Whewell’s exposition open to attack. The work as a whole was one of the most notable contributions to logical doctrine that appeared in Great Britain in the 19th century. His Studies in Deductive Logic, consisting mainly of exercises and problems for the use of students, was published in 1880. In 1877 and the following years Jevons contributed to the Contemporary Review some articles on J. S. Mill, which he had intended to supplement by further articles, and eventually publish in a volume as a criticism of Mill’s philosophy. These articles and one other were republished after Jevons’s death, together with his earlier logical treatises, in a volume, entitled Pure Logic, and other Minor Works. The criticisms on Mill contain much that is ingenious and much that is forcible, but on the whole they cannot be regarded as taking rank with Jevons’s other work. His strength lay in his power as an original thinker rather than as a critic; and he will be remembered by his constructive work as logician, economist and statistician.

See Letters and Journal of W. Stanley Jevons, edited by his wife (1886). This work contains a bibliography of Jevons’s writings. See also Logic: History.

JEW, THE WANDERING, a legendary Jew (see Jews) doomed to wander till the second coming of Christ because he had taunted Jesus as he passed bearing the cross, saying, “Go on quicker.” Jesus is said to have replied, “I go, but thou shalt wait till I return.” The legend in this form first appeared in a pamphlet of four leaves alleged to have been printed at Leiden in 1602. This pamphlet relates that Paulus von Eizen (d. 1598), bishop of Schleswig, had met at Hamburg in 1542 a Jew named Ahasuerus (Ahasverus), who declared he was “eternal” and was the same who had been punished in the above-mentioned manner by Jesus at the time of the crucifixion. The pamphlet is supposed to have been written by Chrysostomus Dudulaeus of Westphalia and printed by one Christoff Crutzer, but as no such author or printer is known at this time—the latter name indeed refers directly to the legend—it has been conjectured that the whole story is a myth invented to support the Protestant contention of a continuous witness to the truth of Holy Writ in the person of this “eternal” Jew; he was to form, in his way, a counterpart to the apostolic tradition of the Catholic Church.

The story met with ready acceptance and popularity. Eight editions of the pamphlet appeared in 1602, and the fortieth edition before the end of the following century. It was translated into Dutch and Flemish with almost equal success. The first French edition appeared in 1609, and the story was known in England before 1625, when a parody was produced. Denmark and Sweden followed suit with translations, and the expression “eternal Jew” passed as a current term into Czech. In other words, the story in its usual form spread wherever there was a tincture of Protestantism. In southern Europe little is heard of it in this version, though Rudolph Botoreus, parliamentary advocate of Paris (Comm. histor., 1604), writing in Paris two years after its first appearance, speaks contemptuously of the popular belief in the Wandering Jew in Germany, Spain and Italy.

The popularity of the pamphlet and its translations soon led to reports of the appearance of this mysterious being in almost all parts of the civilized world. Besides the original meeting of the bishop and Ahasuerus in 1542 and others referred back to 1575 in Spain and 1599 at Vienna, the Wandering Jew was stated to have appeared at Prague (1602), at Lübeck (1603), in Bavaria (1604), at Ypres (1623), Brussels (1640), Leipzig (1642), Paris (1644, by the “Turkish Spy”), Stamford (1658), Astrakhan (1672), and Frankenstein (1678). In the next century the Wandering Jew was seen at Munich (1721), Altbach (1766), Brussels (1774), Newcastle (1790, see Brand, Pop. Antiquities, s.v.), and on the streets of London between 1818 and 1830 (see Athenaeum, 1866, ii. 561). So far as can be ascertained, the latest report of his appearance was in the neighbourhood of Salt Lake City in 1868, when he is said to have made himself known to a Mormon named O’Grady. It is difficult to tell in any one of these cases how far the story is an entire fiction and how far some ingenious impostor took advantage of the existence of the myth.

The reiterated reports of the actual existence of a wandering being, who retained in his memory the details of the crucifixion, show how the idea had fixed itself in popular imagination and found its way into the 19th-century collections of German legends. The two ideas combined in the story of the restless fugitive akin to Cain and wandering for ever are separately represented in the current names given to this figure in different countries. In most Teutonic languages the stress is laid on the perpetual character of his punishment and he is known as the “everlasting,” or “eternal” Jew (Ger. “Ewige Jude”). In the lands speaking a Romance tongue, the usual form has reference to the wanderings (Fr. “le Juif errant”). The English form follows the Romance analogy, possibly because derived directly from France. The actual name given to the mysterious Jew varies in the different versions: the original pamphlet calls him Ahasver, and this has been followed in most of the literary versions, though it is difficult to imagine any Jew being called by the name of the typical anti-Semitic king of the Book of Esther. In one of his appearances at Brussels his name is given as Isaac Laquedem, implying an imperfect knowledge of Hebrew in an attempt to represent Isaac “from of old.” Alexandre Dumas also made use of this title. In the Turkish Spy the Wandering Jew is called Paul Marrane and is supposed to have suffered persecution at the hands of the Inquisition, which was mainly occupied in dealing with the Marranos, i.e. the secret Jews of the Iberian peninsula. In the few references to the legend in Spanish writings the Wandering Jew is called Juan Espera en Dios, which gives a more hopeful turn to the legend.

Under other names, a story very similar to that given in the pamphlet of 1602 occurs nearly 400 years earlier on English soil. According to Roger of Wendover in his Flores historiarum under the year 1228, an Armenian archbishop, then visiting England, was asked by the monks of St Albans about the well-known Joseph of Arimathaea, who had spoken to Jesus and was said to be still alive. The archbishop claimed to have seen him in Armenia under the name of Carthaphilus or Cartaphilus, who had confessed that he had taunted Jesus in the manner above related. This Carthaphilus had afterwards been baptized by the name of Joseph. Matthew Paris, in repeating the passage from Roger of Wendover, reported that other Armenians had confirmed the story on visiting St Albans in 1252, and regarded it as a great proof of the Christian religion. A similar account is given in the chronicles of Philippe Mouskès (d. 1243). A variant of the same story was known to Guido Bonati, an astronomer quoted by Dante, who calls his hero or villain Butta Deus because he struck Jesus. Under this name he is said to have appeared at Mugello in 1413 and at Bologna in 1415 (in the garb of a Franciscan of the third order).

The source of all these reports of an ever-living witness of the crucifixion is probably Matthew xvi. 28: “There be some of them that stand here which shall in no wise taste of death till they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.” As the kingdom had not come, it was assumed that there must be persons living who had been present at the crucifixion; the same reasoning is at the root of the Anglo-Israel belief. These words are indeed quoted in the pamphlet of 1602. Again, a legend was based on John xxi. 20 that the beloved disciple would not die before the second coming; while another legend (current in the 16th century) condemned Malchus, whose ear Peter cut off in the garden of Gethsemane (John xvii. 10), to wander perpetually till the second coming. The legend alleges that he had been so condemned for having scoffed at Jesus. These legends and the 363 utterance of Matt. xvi. 28 became “contaminated” by the legend of St Joseph of Arimathaea and the Holy Grail, and took the form given in Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris. But there is nothing to show the spread of this story among the people before the pamphlet of 1602, and it is difficult to see how this Carthaphilus could have given rise to the legend of the Wandering Jew, since he is not a Jew nor does he wander. The author of 1602 was probably acquainted either directly or indirectly with the story as given by Matthew Paris, since he gives almost the same account. But he gives a new name to his hero and directly connects his fate with Matt. xvi. 28.

Moncure D. Conway (Ency. Brit., 9th ed., xiii. 673) attempted to connect the legend of the Wandering Jew with a whole series of myths relating to never-dying heroes like King Arthur, Frederick Barbarossa, the Seven Sleepers, and Thomas the Rhymer, not to speak of Rip Van Winkle. He goes even farther and connects our legend with mortals visiting earth, as the Yima in Parsism, and the “Ancient of Days” in the Books of Daniel and Enoch, and further connects the legend with the whole medieval tendency to regard the Jew as something uncanny and mysterious. But all these mythological explanations are supererogatory, since the actual legend in question can be definitely traced to the pamphlet of 1602. The same remark applies to the identification with the Mahommedan legend of the “eternal” Chadhir proposed by M. Lidzbarski (Zeit. f. Assyr. vii. 116) and I. Friedländer (Arch. f. Religionswiss. xiii. 110).

This combination of eternal punishment with restless wandering has attracted the imagination of innumerable writers in almost all European tongues. The Wandering Jew has been regarded as a symbolic figure representing the wanderings and sufferings of his race. The Germans have been especially attracted by the legend, which has been made the subject of poems by Schubart, Schreiber, W. Müller, Lenau, Chamisso, Schlegel, Mosen and Koehler, from which enumeration it will be seen that it was a particularly favourite subject with the Romantic school. They were perhaps influenced by the example of Goethe, who in his Autobiography describes, at considerable length, the plan of a poem he had designed on the Wandering Jew. More recently poems have been composed on the subject in German by Adolf Wilbrandt, Fritz Lienhard and others; in English by Robert Buchanan, and in Dutch by H. Heijermans. German novels also exist on the subject, by Franz Horn, Oeklers, Laun and Schucking, tragedies by Klinemann, Haushofer and Zedlitz. Sigismund Heller wrote three cantos on the wanderings of Ahasuerus, while Hans Andersen made of him an “Angel of Doubt.” Robert Hamerling even identifies Nero with the Wandering Jew. In France, E. Quinet published a prose epic on the subject in 1833, and Eugène Sue, in his best-known work, Le Juif errant (1844), introduces the Wandering Jew in the prologues of its different sections and associates him with the legend of Herodias. In modern times the subject has been made still more popular by Gustave Doré’s elaborate designs (1856), containing some of his most striking and imaginative work. Thus, probably, he suggested Grenier’s poem on the subject (1857).

In England, besides the ballads in Percy’s Reliques, William Godwin introduced the idea of an eternal witness of the course of civilization in his St Leon (1799), and his son-in-law Shelley introduces Ahasuerus in his Queen Mab. It is doubtful how far Swift derived his idea of the immortal Struldbrugs from the notion of the Wandering Jew. George Croly’s Salathiel, which appeared anonymously in 1828, gave a highly elaborate turn to the legend; this has been republished under the title Tarry Thou Till I Come.

Bibliography.—J. G. Th. Graesse, Die Sage vom ewigen Juden (1844); F. Helbig, Die Sage vom ewigen Juden (1874); G. Paris, Le Juif errant (1881); M. D. Conway, The Wandering Jew (1881); S. Morpugo, L’ Ebreo errante in Italia (1891); L. Neubaur, Die Sage vom ewigen Juden (2nd ed., 1893). The recent literary handling of the subject has been dealt with by J. Prost, Die Sage vom ewigen Juden in der neueren deutschen Literatur (1905); T. Kappstein, Ahasver in der Weltpoesie (1905).

JEWEL, JOHN (1522-1571), bishop of Salisbury, son of John Jewel of Buden, Devonshire, was born on the 24th of May 1522, and educated under his uncle John Bellamy, rector of Hampton, and other private tutors until his matriculation at Merton college, Oxford, in July 1535. There he was taught by John Parkhurst, afterwards bishop of Norwich; but on the 19th of August 1539 he was elected scholar of Corpus Christi college. He graduated B.A. in 1540, and M.A. in 1545, having been elected fellow of his college in 1542. He made some mark as a teacher at Oxford, and became after 1547 one of the chief disciples of Peter Martyr. He graduated B.D. in 1552, and was made vicar of Sunningwell, and public orator of the university, in which capacity he had to compose a congratulatory epistle to Mary on her accession. In April 1554 he acted as notary to Cranmer and Ridley at their disputation, but in the autumn he signed a series of Catholic articles. He was, nevertheless, suspected, fled to London, and thence to Frankfort, which he reached in March 1555. There he sided with Coxe against Knox, but soon joined Martyr at Strassburg, accompanied him to Zurich, and then paid a visit to Padua.

Under Elizabeth’s succession he returned to England, and made earnest efforts to secure what would now be called a low-church settlement of religion. Indeed, his attitude was hardly distinguishable from that of the Elizabethan Puritans, but he gradually modified it under the stress of office and responsibility. He was one of the disputants selected to confute the Romanists at the conference of Westminster after Easter 1559; he was select preacher at St Paul’s cross on the 15th of June; and in the autumn was engaged as one of the royal visitors of the western counties. His congé d’élire as bishop of Salisbury had been made out on the 27th of July, but he was not consecrated until the 21st of January 1560. He now constituted himself the literary apologist of the Elizabethan settlement. He had on the 26th of November 1559, in a sermon at St Paul’s Cross, challenged all comers to prove the Roman case out of the Scriptures, or the councils or Fathers for the first six hundred years after Christ. He repeated his challenge in 1560, and Dr Henry Cole took it up. The chief result was Jewel’s Apologia ecclesiae Anglicanae, published in 1562, which in Bishop Creighton’s words is “the first methodical statement of the position of the Church of England against the Church of Rome, and forms the groundwork of all subsequent controversy.” A more formidable antagonist than Cole now entered the lists in the person of Thomas Harding, an Oxford contemporary whom Jewel had deprived of his prebend in Salisbury Cathedral for recusancy. He published an elaborate and bitter Answer in 1564, to which Jewel issued a Reply in 1565. Harding followed with a Confutation, and Jewel with a Defence, of the Apology in 1566 and 1567; the combatants ranged over the whole field of the Anglo-Roman controversy, and Jewel’s theology was officially enjoined upon the Church by Archbishop Bancroft in the reign of James I. Latterly Jewel had been confronted with criticism from a different quarter. The arguments that had weaned him from his Zwinglian simplicity did not satisfy his unpromoted brethren, and Jewel had to refuse admission to a benefice to his friend Laurence Humphrey (q.v.), who would not wear a surplice. He was consulted a good deal by the government on such questions as England’s attitude towards the council of Trent, and political considerations made him more and more hostile to Puritan demands with which he had previously sympathized. He wrote an attack on Cartwright, which was published after his death by Whitgift. He died on the 23rd of September 1571, and was buried in Salisbury Cathedral, where he had built a library. Hooker, who speaks of Jewel as “the worthiest divine that Christendom hath bred for some hundreds of years,” was one of the boys whom Jewel prepared in his house for the university; and his Ecclesiastical Polity owes much to Jewel’s training.

Jewel’s works were published in a folio in 1609 under the direction of Bancroft, who ordered the Apology to be placed in churches, in some of which it may still be seen chained to the lectern; other editions appeared at Oxford (1848, 8 vols.) and Cambridge (Parker Soc., 4 vols.). See also Gough’s Index to Parker Soc. Publ.; Strype’s Works (General Index); Acts of the Privy Council; Calendars of Domestic and Spanish State Papers; Dixon’s and Frere’s Church Histories; and Dictionary of National Biography (art. by Bishop Creighton).

JEWELRY (O. Fr. jouel, Fr. joyau, perhaps from joie, joy; Lat. gaudium; retranslated into Low Lat. jocale, a toy, from jocus, by misapprehension of the origin of the word), a collective term for jewels, or the art connected with them—jewels being personal ornaments, usually made of gems, precious stones, &c., with a setting of precious metal; in a restricted sense it is also common to speak of a gem-stone itself as a jewel, when utilized in this way. Personal ornaments appear to have been among the very first objects on which the invention and ingenuity of man were exercised; and there is no record of any people so rude as not to employ some kind of personal decoration. Natural objects, such as small shells, dried berries, small perforated stones, feathers of variegated colours, were combined by stringing or tying together to ornament the head, neck, arms and legs, the fingers, and even the toes, whilst the cartilages of the nose and ears were frequently perforated for the more ready suspension of suitable ornaments.

Amongst modern Oriental nations we find almost every kind of personal decoration, from the simple caste mark on the forehead of the Hindu to the gorgeous examples of beaten gold and silver work of the various cities and provinces of India. Nor are such decorations mere ornaments without use or meaning. The hook with its corresponding perforation or eye, the clasp, the buckle, the button, grew step by step into a special ornament, according to the rank, means, taste and wants of the wearer, or became an evidence of the dignity of office. Nor was the jewel deemed to have served its purpose with the death of its owner, for it is to the tombs of ancient peoples that we must look for evidence of the early existence of the jeweller’s art.

The jewelry of the ancient Egyptians has been preserved for us in their tombs, sometimes in, and sometimes near the sarcophagi which contained the embalmed bodies of the wearers. An amazing series of finds of the intact jewels of five princesses of the XIIth Dynasty (c. 2400 B.C.) was the result of the excavations of J. de Morgan at Dāhshur in 1894-1895. The treasure of Princess Hathor-Set contained jewels with the names of Senwosri (Usertesen) II. and III., one of whom was probably her father. The treasure of Princess Merit contained the names of the same two monarchs, and also that of Amenemhē III., to whose family Princess Nebhotp may have belonged. The two remaining princesses were Ita and Khnumit.

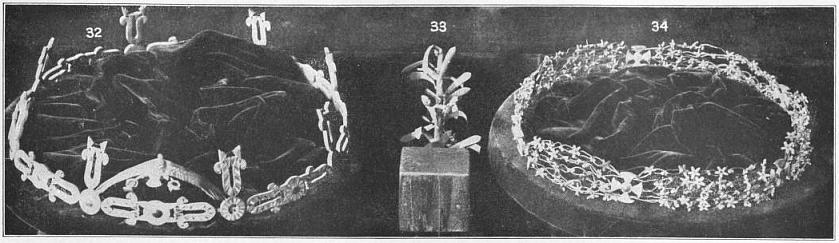

|

| Fig. 1. |

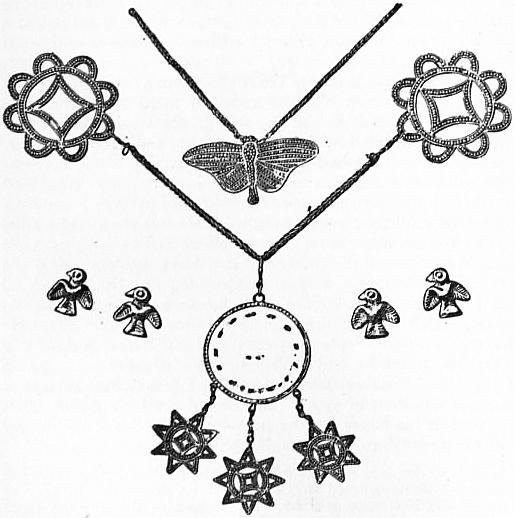

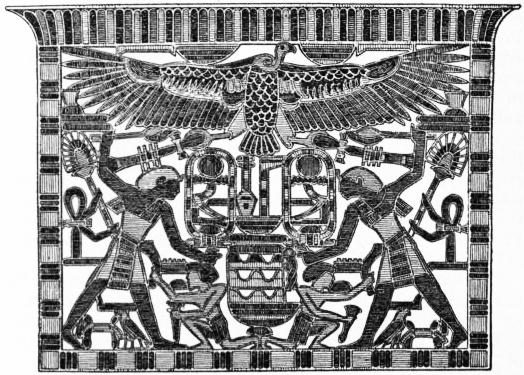

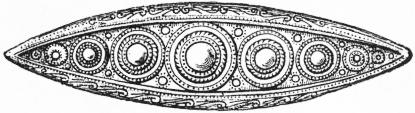

The art of the nameless Memphite jewellers of the XIIth Dynasty is marked by perfect accuracy of execution, by sureness of intention, by decorative instinct and sobriety in design, and by the serviceable nature of the jewels for actual wear. All forms of work are represented—including chiselling, soldering, inlaying with coloured stones, moulding and working with twisted wires and filigree. Here also occurs the earliest instance of granulated work, with small grains of gold, soldered on a flat surface (fig. 1). The principal items in this dazzling group are the following: Three gold pectorals (fig. 2 and Plate I. figs. 35, 36) worked à jour (with the interstices left open); on the front side they are inlaid with coloured stones, the fine cloisons being the only portion of the gold that is visible; on the back, the gold surfaces are most delicately carved, in low relief. Two gold crowns (Plate I. figs. 32, 34), found together, are curiously contrasted in character. The one (fig. 32) is of a formal design, of gold, inlaid (the plume, Plate I. fig 33, was attached to it); the other (fig. 34) has a multitude of star-like flowers, embodied in a filigree of daintily twisted wires. A dagger with inlaid patterns on the handle shows extraordinary perfection of finish.

|

| Fig. 2. |

|

| Fig. 3. |

Nearly a thousand years later we have another remarkable collection of Egyptian art in the jewelry taken from the coffin of Queen Aah-hotp, discovered in 1859 by Mariette in the entrance to the valley of the tombs of the kings and now preserved in the Cairo museum. Compared with the Dāhshur treasure the jewelry of Aah-hotp is in parts rough and coarse, but none the less it is marked by the ingenuity and mastery of the materials that characterize all the work of the Egyptians. Hammered work, incised and chased work, the evidence of soldering, the combinations of layers of gold plates, together with coloured stones, are all present, and the handicraft is complete in every respect.

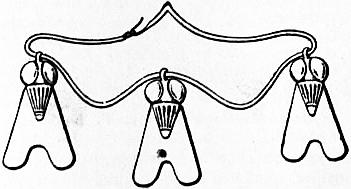

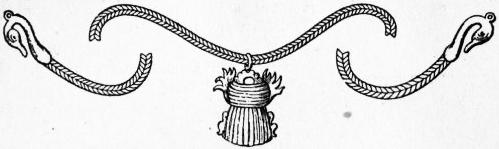

A diadem of gold and enamel, found at the back of the head of the mummy of the queen (fig. 3), was fixed in the back hair, showing the cartouche in front. The box holding this cartouche has on the upper surface the titles of the king, “the son of the sun, Aahmes, living for ever and ever,” in gold on a ground of lapis lazuli, with a chequered ornament in blue and red pastes, and a sphinx couchant on each side. A necklace with three pendant flies (fig. 4) is entirely of gold, having a hook and loop to fasten it round the neck. Fig. 5 is a gold drop, inlaid with turquoise or blue paste, in the shape of a fig. A gold 365 chain (fig. 6) is formed of wires closely plaited and very flexible, the ends terminating in the heads of water fowl, and having small rings to secure the collar behind. To the centre is suspended by a small ring a scarabaeus of solid gold inlaid with lapis lazuli. We have an example of a bracelet, similar to those in modern use (fig. 7), and worn by all persons of rank. It is formed of two pieces joined by a hinge, and is decorated with figures in repoussé on a ground inlaid with lapis lazuli.

|

|

| Fig. 4. | Fig. 5. |

|

| Fig. 6. |

|

|

| Fig. 7. | Fig. 8. |

|

| Fig. 9.—From Archaeologia, vol. 59, p. 447, by permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London. |

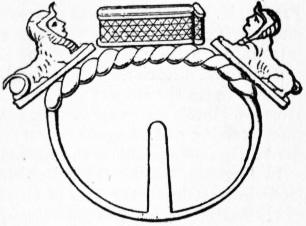

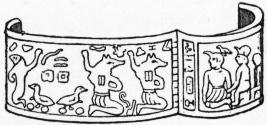

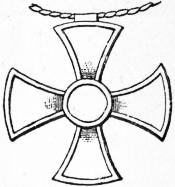

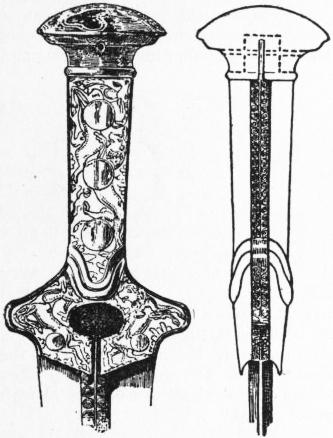

That the Assyrians used personal decorations of a very distinct character, and no doubt made of precious materials, is proved by the bas-reliefs from which a considerable collection of jewels could be gathered, such as bracelets, ear-rings and necklaces. Thus, for example, in the British Museum we have representations of Assur-nazir-pal, king of Assyria (c. 885-860 B.C.), wearing a cross (fig. 8) very similar to the Maltese cross of modern times. It happens, however, that the excavations have not hitherto been fertile in actual remains of gold work from Assyria. Chance also has so far ordained that the excavations in Crete should not be particularly rich in ornaments of gold. A few isolated objects have been found, such as a duck and other pendants, and also several necklaces with beads of the Argonaut shell-fish pattern. More striking than these is a short bronze sword. The handle has an agate pommel, and is covered with gold plates, engraved with spirited scenes of lions and wild goats (fig. 9, A. J. Evans in Archaeologia, 59, 447). In general, however, the gold jewelry of the later Minoan periods is more brilliantly represented by the finds made on the mainland of Greece and at Enkomi in Cyprus. Among the former the gold ornaments found by Heinrich Schliemann in the graves of Mycenae are pre-eminent.

|

|

| Fig. 10. | Fig. 11. |

|

| Fig. 12. |

|

| Fig. 13. |

The objects found ranged over most of the personal ornaments still in use; necklaces with gold beads and pendants, butterflies (fig. 10), cuttlefish (fig. 11), single and concentric circles, rosettes and leafage, with perforations for attachment to clothing, crosses and stars formed of combined crosses, with crosses in the centre forming spikes—all elaborately ornamented in detail. The spiral forms an incessant decoration from its facile production and repetition by means of twisted gold wire. Grasshoppers or tree crickets in gold repoussé suspended by chains and probably used for the decoration of the hair, and a griffin (fig. 12), having the upper part of the body of an eagle and the lower parts of a lion, with wings decorated with spirals, are among the more remarkable examples of perforated ornaments for attachment to the clothing. There are also perforated ornaments belonging to necklaces, with intaglio engravings of such subjects as a contest of a man and lion, and a duel of two warriors, one of whom stabs his antagonist in the throat. There are also pinheads and brooches formed of two stags lying down (fig. 13), the bodies and necks crossing each other, and the horns meeting symmetrically above the heads, forming a finial. The heads of these ornaments were of gold, with silver blades or pointed pins inserted for use. The bodies of the two stags rest on fronds of the date-palm growing out of the stem which receives the pin. Another remarkable series is composed of figures of women with doves. Some have one dove resting on the head; others have three doves, one on the head and the others resting on arms. The arms in both instances are extended to the elbow, the hands being placed on the breasts. These ornaments are also perforated, and were evidently sewed on the dresses, although there is some evidence that an example with three doves has been fastened with a pin.

An extraordinary diadem was found upon the head of one of the bodies discovered in the same tomb with many objects similar to those noticed above. It is 25 in. in length, covered with shield-like or rosette ornaments in repoussé, the relief being very low but perfectly distinct, and further ornamented by thirty-six large leaves of repoussé gold attached to it. As an example of design and perfection of detail, another smaller diadem found in another tomb may be noted (fig. 14). It is of gold plate, so thick as to require no “piping” at the back to sustain it; but in general the repoussé examples have a piping of copper wire.

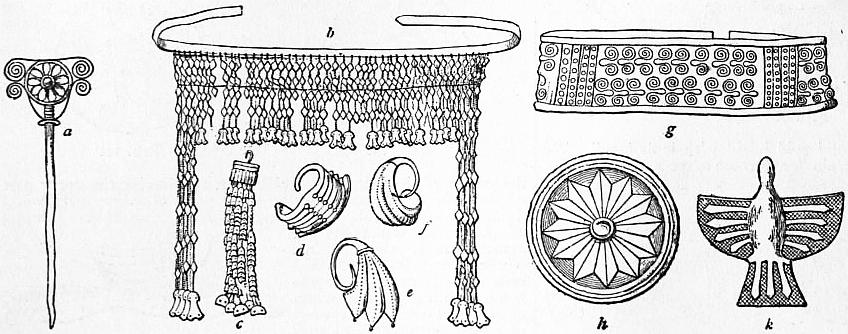

|

| Fig. 14. |

The admirable inlaid daggers of the IVth grave at Mycenae are unique in their kind, with their subjects of a lion hunt, of a lion chasing a herd of antelopes, of running lions, of cats hunting wild duck, of inlaid lilies, and of geometric patterns. The subjects are inlaid in gold of various tints, and silver, in bronze plates which are inserted in the flat surfaces of the dagger-blades. In part also the subjects are rendered in relief and gilded. The whole is executed with marvellous precision and vivid representation of motion. To a certain limited extent these daggers are paralleled by a dagger and hatchet found in the treasure of Queen Aah-hotp mentioned above, but in their most characteristic features there is little resemblance. The gold ornaments found by Schliemann at Hissarlik, the supposed site of Troy, divide themselves, generally speaking, into two groups, one being the “great treasure” of diadems, ear-rings, beads, bracelets, &c., which seem the product of a local and uncultured art. The other group, which were found in smaller “treasures,” have spirals and rosettes similar to those of Mycenae. The discovery, however, of the gold treasures of the Artemision at Ephesus has brought out points of affinity between the Hissarlik treasures and those of Ephesus, and has made any reasoning difficult, in view of the uncertainties surrounding the Hissarlik finds. The group with 366 Mycenaean affinities (fig. 15) includes necklaces, brooches, bracelets (g), hair-pins (a), ear-rings (c, d, e, f), with and without pendants, beads and twisted wire drops. The majority of these are ornamented with spirals of twisted wire, or small rosettes, with fragments of stones in the centres. The twisted wire ornaments were evidently portions of necklaces. A circular plaque decorated with a rosette (h) is very similar to those found at Mycenae, and a conventionalized eagle (k) is characteristic of much of the detail found at that place as well as at Hissarlik. They were all of pure gold, and the wire must have been drawn through a plate of harder metal—probably bronze. The principal ornaments differing from those found at Mycenae are diadems or head fillets of pure hammered gold (b) cut into thin plates, attached to rings by double gold wires, and fastened together at the back with thin twisted wire. To these pendants (of which those at the two ends are nearly three times the length of those forming the central portions) are attached small figures, probably of idols. It has been assumed that these were worn across the forehead by women, the long pendants falling on each side of the face.

|

| Fig. 15. |

The jewelry of the close of the Mycenaean period is best represented by the rich finds of the cemetery of Enkomi near Salamis, in Cyprus. This field was excavated by the British Museum in 1896, and a considerable portion of the finds is now at Bloomsbury. It was rich in all forms of jewelry, but especially in pins, rings and diadems with patterns in relief. In its geometric patterns the art of Enkomi is entirely Mycenaean, but special stress is laid on the mythical forms that were inherited by Greek art, such as the sphinx and the gryphon.

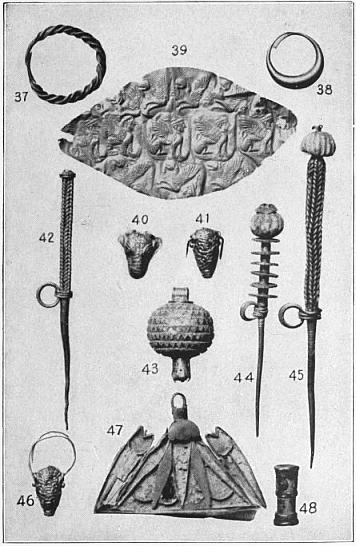

| Figs. | 37-48 | (Plate I.) | are examples of the late Mycenaean treasures from Enkomi. |

| ” | 37, 38 | ” | Ear-rings. |

| ” | 39 | ” | Diadem, to be tied on the forehead. The impressed figure of a sphinx is repeated twelve times. |

| ” | 40, 41, 46 | ” | Ear-rings, originally in bull’s head form (fig. 40). Later, the same general form is retained, but decorative patterns (figs. 41, 46) take the place of the bull’s head. |

| ” | 42 | ” | Pin, probably connected by a chain with a fellow, to be used as a cloak fastening. |

| ” | 43 | ” | Pomegranate pendant, with fine granulated work. |

| ” | 44, 45 | ” | Pins as No. 42. The heads are of vitreous paste. |

| ” | 46 | (See above.) | |

| ” | 47 | ” | Pendant ornament, in lotus-form, of a pectoral, inlaid with coloured pastes. |

| ” | 48 | ” | Small slate cylinder, set in filigree. |

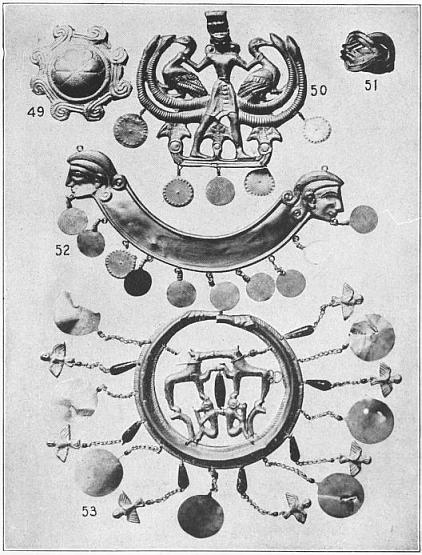

Another find of importance was that of a collection of gold ornaments from one of the Greek islands (said to be Aegina) which also found its way to the British Museum. Here we find the themes of archaic Greek art, such as a figure holding up two water-birds, in immediate connexion with Mycenaean gold patterns.

| Figs. | 49-53 | (Plate I.) | are specimens from this treasure. |

| ” | 49 | ” | Plate with repoussé ornament for sewing on a dress. |

| ” | 50 | ” | Pendant. Figure with two water-birds, on a lotus base, and having serpents issuing from near his middle, modified from Egyptian forms. |

| ” | 51 | ” | Ring, with cut blue glass-pastes in the grooves. |

| ” | 52 | ” | Pendant ornament, repoussé, and originally inlaid with pieces of cut glass-paste. |

| ” | 53 | ” | Pendant ornament, with dogs and apes, modified from Egyptian forms. |

For the beginnings of Greek art proper, the most striking series of personal jewels is the great deposit of ornaments which was found in 1905 by D. G. Hogarth in the soil beneath the central basis of the archaic temple of Artemis of Ephesus. The gold ornaments in question (amounting in all to about 1000 pieces) were mingled with the closely packed earth, and must necessarily, it would seem, have been in the nature of votive offerings, made at the end of the 7th or the beginning of the 6th century B.C. The hoard was rich in pins, brooches, beads and stamped disks of gold. The greater part of the find is at Constantinople, but a portion was assigned to the British Museum, which had undertaken the excavations.

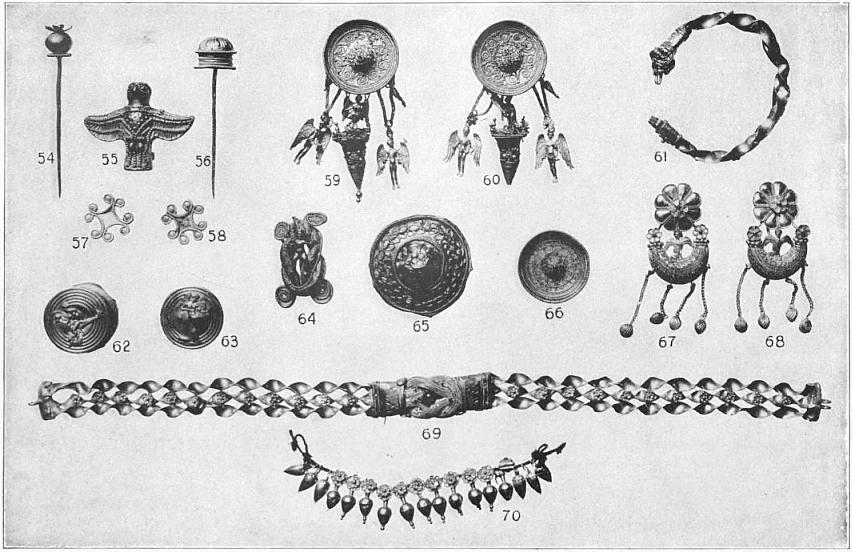

| Figs. | 54-58 | (Plate II.) | Examples of the Ephesus hoard. |

| ” | 54 | ” | Electrum pin, with pomegranate head. |

| ” | 55 | ” | Hawk ornament. |

| ” | 56 | ” | Electrum pin. |

| ” | 57, 58 | ” | Electrum ornaments for sewing on drapery. |

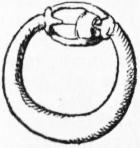

The cemeteries of Cyprus have yielded a rich harvest of jewelry of Graeco-Phoenician style of the 7th and following centuries B.C. Figs. 16 and 17 are typical examples of a ring and ear-ring from Cyprus.

|

|

| Fig. 16. | Fig. 17. |

Greek, Etruscan and Roman ornaments partake of very similar characteristics. Of course there is variety in design and sometimes in treatment, but it does not rise to any special individuality. Fretwork is a distinguishing feature of all, together with the wave ornament, the guilloche, and the occasional use of the human figure. The workmanship is often of a character which modern gold-workers can only rival with their best skill, and can never surpass.

|

| Fig. 18. |

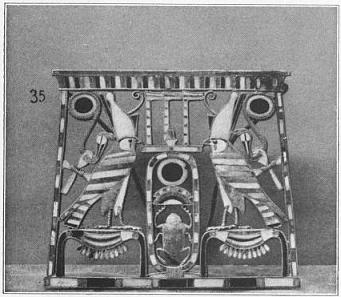

Plate I.

| |

|

|

| EARLY EGYPTIAN. | |

|

|

| (From Enkomi.) | (From the Greek Islands.) |

| LATE MYCENAEAN. | |

Plate II.

| |

| GREEK. | |

|

|

| ETRUSCAN. | ROMAN. |

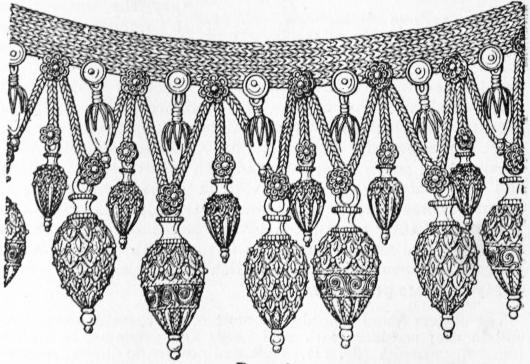

The Greek jewelry of the best period is of extraordinary delicacy and beauty. Fine examples are shown in the British Museum from Melos and elsewhere. Undoubtedly, however, the most brilliant collection of such ornaments is that of the Hermitage, which was derived from the tombs of Kerch and the Crimea. It contains examples of the purest Greek work, together with objects which must have been of local origin, as is shown by the themes which the artist has chosen for his reliefs. Fig. 18 illustrates the jewelry of the Hermitage (see also Ear-Ring).

As further examples of Greek jewelry see the pendant oblong ornament for containing a scroll (fig. 19).

| ||

| Fig. 19. | Fig. 20. | Fig. 21. |

The ear-rings (figs. 20, 21) are also characteristic.

| Figs. | 59-70 | (Plate II.) | Examples of fine Greek jewelry, in the British Museum. |

| ” | 59-60 | ” | Pair of ear-rings, from a grave at Cyme in Aeolis, with filigree work and pendant Erotes. |

| ” | 61 | ” | Small bracelet. |

| ” | 62-63 | ” | Small gold reel with repoussé figures of Nereid with helmet of Achilles, and Eros. From Cameiros (Rhodes). |

| ” | 64 | ” | Filigree ornament (ear-ring?) with Eros in centre. From Syria. |

| ” | 65 | ” | Medallion ornament with repoussé head of Dionysos and filigree work. (Blacas coll.) |

| ” | 66 | ” | Stud, with filigree work. |

| ” | 67-68 | ” | Pair of ear-rings, of gold, with filigree and enamel, from Eretria. |

| ” | 69 | ” | Diadem, with filigree, and enamel scales, from Tarquinii. |

| ” | 70 | ” | Necklace pendants. |

Etruscan jewelry at its best is not easily distinguished from the Greek, but it tends in its later forms to become florid and diffuse, without precision of design. The granulation of surfaces practised with the highest degree of refinement by the Etruscans was long a puzzle and a problem to the modern jeweller, until Castellani of Rome discovered gold-workers in the Abruzzi to whom the method had descended through many generations. He induced some of these men to go to Naples, and so revived the art, of which he contributed examples to the London Exhibition of 1872 (see Filigree).

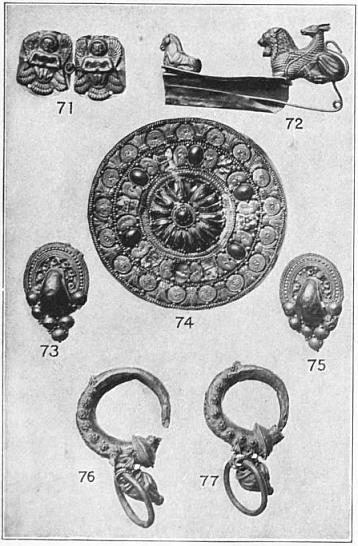

| Figs. | 71-77 | (Plate II.) | are well-marked examples of Etruscan work, in the British Museum. |

| ” | 71 | ” | Pair of sirens, repoussé, forming a hook and eye fastening. From Chiusi (?). |

| ” | 72 | ” | Early fibula. Horse and chimaera. (Blacas coll.) |

| ” | 74 | ” | Medallion-shaped fibula, of fine granulated work, with figures of sirens in relief, and set with dark blue pastes. (Bale coll.) |

| ” | 73, 75 | ” | Pair of late Etruscan ear-rings. |

| ” | 76, 77 | ” | Pair of late Etruscan ear-rings, in the florid style. |

The jewels of the Roman empire are marked by a greater use of large cut stones in combination with the gold, and by larger surfaces of plain and undecorated metal. The adaptation of imperial gold coins to the purposes of the jeweller is also not uncommon.

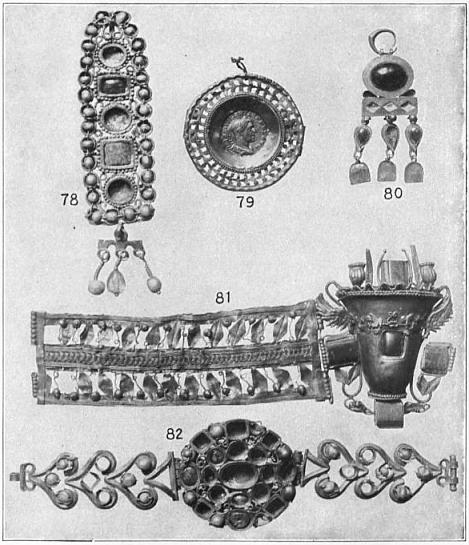

| Figs. | 78-82 | (Plate II.) | Late Roman imperial jewelry, in the British Museum. |

| ” | 78 | ” | Large pendant ear-ring, set with stones and pearls. From Tunis, 4th century. |

| ” | 79 | ” | Pierced-work pendant, set with a coin of the emperor Philip. |

| ” | 80 | ” | Ear-ring, roughly set with garnets. |

| ” | 81 | ” | Bracelet, with a winged cornucopia as central ornament, set with plasmas, and with filigree and leaf work. |

| ” | 82 | ” | Bracelet, roughly set with pearls and stones. From Tunis, 4th century. |

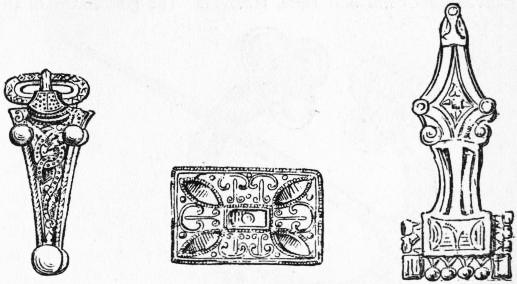

With the decay of the Roman empire, and the approach of the barbarian tribes, a new Teutonic style was developed. An important example of this style is the remarkable gold treasure, discovered at Pétrossa in Transylvanian Alps in 1837, and now preserved, as far as it survives, in the museum of Bucharest. A runic inscription shows that it belonged to the Goths. Its style is in part the classical tradition, debased and modified; in part it is a singularly rude and vigorous form of barbaric art. Its chief characteristics are a free use of strongly conventionalized animal forms, such as great bird-shaped fibulae, and an ornamentation consisting of pierced gold work, combined with a free use of stones cut to special shapes, and inlaid either cloisonné-fashion or in a perforated gold plate. This part of the hoard has its affinities in objects found over a wide field from Siberia to Spain. Its rudest and most naturalistic forms occur in the East in uncouth objects from Siberian tombs, whose lineage however has been traced to Persepolis, Assyria and Egypt. In its later and more refined forms the style is known by the name, now somewhat out of favour (except as applied to a limited number of finds), of Merovingian.

| ||

| Fig. 22. | Fig. 23. | Fig. 24. |

| ||

| Fig. 25. | Fig. 26. | Fig. 27. |

|

| Fig. 28. |

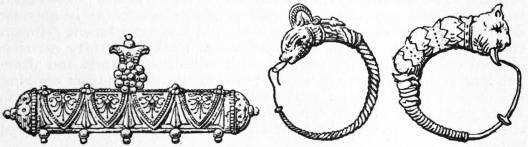

The so-called Merovingian jewelry of the 5th century, and the Anglo-Saxon of a later date, have as their distinctive feature thin plates of gold, decorated with thin slabs of garnet, set in walls of gold soldered vertically like the lines of cloisonné enamel, with the addition of very decorative details of filigree work, beading and twisted gold. The typical group are the contents of the tomb of King Childeric (A.D. 481) now in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris. In Figs. 22 and 23 we have examples of Anglo-Saxon fibulae, the first being decorated with a species of cloisonné, in which garnets are inserted, while the other is in hammered work in relief. A pendant (fig. 24) is also set with garnets. The buckles (figs. 25, 26, 27) are remarkably characteristic examples, and very elegant in design. A girdle ornament in gold, set with garnets (fig. 28), is an example of Carolingian design of a high class. Another remarkable group of barbaric jewelry, dated by coins as of the beginning of the 7th century, was excavated at Castel Trosino near the Picenian Ascoli, and is attributed to the Lombards. See Monumenti antichi (Accademia dei Lincei), xii. 145.

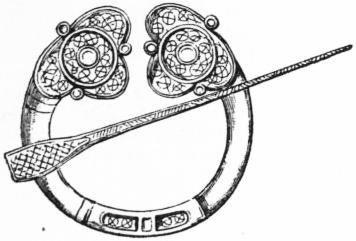

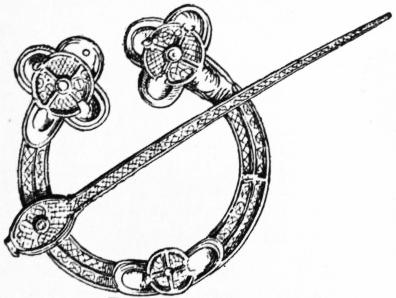

We turn now to the Celtic group of jewelled ornaments, which has an equally long and independent line of descent. The characteristic Celtic ornaments are of hammered work with details in repoussé, having fillings-in of vitreous paste, coloured enamels, amber, and in the later examples rock crystal with a smooth rounded surface cut en cabochon. The 368 whole group is a special development within the British Isles of the art of the mid-European Early Iron age, which in its turn had been considerably influenced by early Mediterranean culture. In its early stages its special marks are combinations of curves, with peculiar central thickenings which give a quasi-naturalistic effect; a skilful use of inlaid enamels, and the chased line. After the introduction of Christianity, a continuous tradition combined the old system with the interlaced winding scrolls and other new forms of decoration, and so led up to the extreme complexity of early Irish illumination and metal work.

A remarkable group of gold ornaments of the pre-Christian time (probably of the 1st century) was discovered about 1896, in the north-west of Ireland, and acquired by the British Museum. It was subsequently claimed by the Crown as treasure trove, and after litigation was transferred to Dublin (see Archaeologia, lv., pl. 22).

|

| Fig. 29. |

Figs. 29 and 30 are illustrations of two brooches of the latest period in this class of work. The first is 13th century; the latter is probably 12th century, and is set with paste, amber and blue.

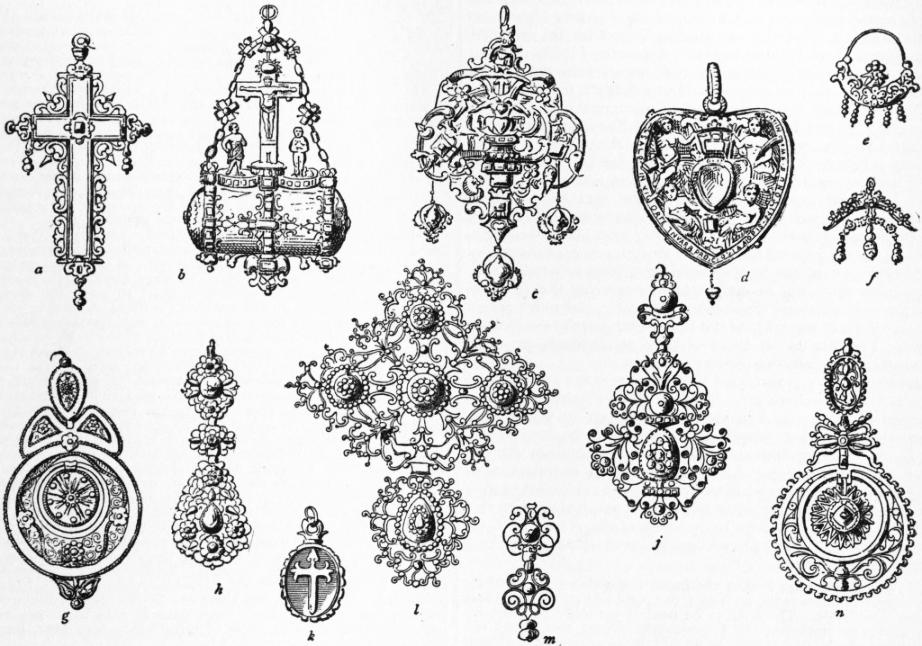

Rings are the chief specimens now seen of medieval jewelry from the 10th to the 13th century. They are generally massive and simple. Through the 16th century a variety of changes arose; in the traditions and designs of the cinquecento we have plenty of evidence that the workmen used their own designs, and the results culminated in the triumphs of Albert Dürer, Benvenuto Cellini and Hans Holbein. The goldsmiths of the Italian republics must have produced works of surpassing excellence in workmanship, and reaching the highest point in design as applied to handicrafts of any kind. The use of enamels, precious stones, niello work and engraving, in combination with skilful execution of the human figure and animal life, produced effects which modern art in this direction is not likely to approach, still less to rival.

|

| Fig. 30. |

In fig. 31 illustrations are given of various characteristic specimens of the Renaissance and later forms of jewelry. A crystal cross set in enamelled gold (a) is German work of the 16th century. The pendant reliquary (b), enamelled and jewelled, is of 16th century Italian work, and so probably is the jewel (c) of gold set with diamonds and rubies. The Darnley or Lennox jewel (d), now in the possession of the king, was made about 1576-1577 for Lady Margaret Douglas, countess of Lennox, the mother of Henry Darnley. It is a pendant golden heart set with a heart-shaped sapphire, richly jewelled and enamelled with emblematic figures and devices. It also has Scottish mottoes around and within it. The ear-ring (e) of gold, enamelled, hung with small pearls, is an example of 17th century Russian work, and another (f) is Italian of the same period, being of gold and filigree with enamel, also with pendant pearls. A Spanish ear-ring, of 18th century work (g), is a combination of ribbon, cord and filigree in gold; and another (h) is Flemish, of probably the same period; it is of gold open work set with diamonds in projecting collets. The old French-Normandy pendant cross and locket (l) presents a characteristic example of peasant jewelry; it is of branched open work set with bosses and ridged ornaments of crystal. The ear-ring (j) is French of 17th century, also of gold open work set with crystals. A small pendant locket (k) is of rock crystal, with the cross of Santiago in gold and translucent crimson enamel; it is 16th or 17th century Spanish work. A pretty ear-ring of gold open scroll work (m), set with minute diamonds and three pendant pearls, is Portuguese of 17th century, and another ear-ring (n) of gold circular open work, set also with minute diamonds, is Portuguese work of 18th century. These examples fairly illustrate the general features of the most characteristic jewelry of the dates quoted.

During the 17th and 18th centuries we see only a mechanical kind of excellence, the results of the mere tradition of the workshop—the lingering of the power which when wisely directed had done so much and so well, but now simply living on traditional forms, often combined in a most incongruous fashion. Gorgeous effects were aimed at by massing the gold, and introducing stones elaborately cut in themselves or clustered in groups. Thus diamonds were clustered in rosettes and bouquets; rubies, pearls, emeralds and other coloured special stones were brought together for little other purpose than to get them into a given space in conjunction with a certain quantity of gold. The question was not of design in its relation to use as personal decoration, but of the value which could be got into a given space to produce the most striking effect.

The traditions of Oriental design as they had come down through the various periods quoted, were comparatively lost in the wretched results of the rococo of Louis XIV. and the inanities of what modern revivalists of the Anglo-Dutch call “Queen Anne.” In the London exhibition of 1851, the extravagances of modern jewelry had to stand comparison with the Oriental examples contributed from India. Since then we have learnt more about these works, and have been compelled to acknowledge, in spite of what is sometimes called inferiority of workmanship, how completely the Oriental jeweller understood his work, and with what singular simplicity of method he carried it out. The combinations are always harmonious, the result aimed at is always achieved; and if in attempting to work to European ideas the jeweller failed, this was rather the fault of the forms he had to follow, than due to any want of skill in making the most of a subject in which half the thought and the intended use were foreign to his experience.

A collection of peasant jewelry got together by Castellani for the Paris exhibition of 1867, and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, illustrates in an admirable manner the traditional jewelry and personal ornaments of a wide range of peoples in Europe. This collection, and the additions made to it since its acquisition by the nation, show the forms in which these objects existed over several generations among the peasantry of France (chiefly Normandy), Spain, Portugal, Holland, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland, and also show how the forms popular in one country are followed and adopted in another, almost invariably because of their perfect adaptation to the purpose for which they were designed.

Apart from these humbler branches of the subject, in the middle of the 19th century the production of jewelry, regarded as a personal art, and not as a commercial and anonymous industry, was almost extinct. Its revival must be associated with the artistic movement which marked the close of that century, and which found emphatic expression in the Paris international exhibition of 1900. For many years before 1895 this industry, though prosperous from the commercial point of view, and always remarkable from that of technical finish, remained stationary as an art. French jewelry rested on its 369 reputation. The traditions were maintained of either the 17th and 18th centuries or the style affected at the close of the second empire—light pierced work and design borrowed from natural flowers. The last type, introduced by Massin, had exercised, indeed, a revolutionary influence on the treatment of jewelry. This clever artist, not less skilful as a craftsman, produced a new genre by copying the grace and lightness of living blossoms, thus introducing a perfectly fresh element into the limited variety of traditional style, and by the use of filigree gold work altering its character and giving it greater elegance. Massin still held the first rank in the exhibition of 1878; he had a marked influence on his contemporaries, and his name will be remembered in the history of the goldsmith’s art to designate a style and a period. Throughout these years the craft was exclusively devoted to perfection of workmanship. The utmost finish was aimed at in the mounting and setting of gems; jewelry was, in fact, not so much an art as a high-class industry; individual effort and purpose were absent.

|

| Fig. 31. |

Up to that time precious stones had been of such intrinsic value that the jeweller’s chief skill lay in displaying these costly stones to the best advantage; the mounting was a secondary consideration. The settings were seldom long preserved in their original condition, but in the case of family jewels were renewed with each generation and each change of fashion, a state of things which could not be favourable to any truly artistic development of taste, since the work was doomed, sooner or later, to destruction. However, the evil led to its own remedy. As soon as diamonds fell in value they lost at the same time their overwhelming prestige, and refined taste could give a preference to trinkets which derived their value and character from artistic design. This revolutionized the jeweller’s craft, and revived the simple ornament of gold or silver, which came forward but timidly at first, till, in the Salon of 1895, it burst upon the world in the exhibits of René Lalique, an artist who was further confirmed in his remarkable position by the exhibition of 1900. What specially stamps the works of Lalique is their striking originality. His work may be considered from the point of view of design and from that of execution. As an artist he has completely reconstructed from the foundation the scheme of design which had fed the poverty-stricken imagination of the last generation of goldsmiths. He had recourse to the art of the past, but to the spirit rather than the letter, and to nature for many new elements of design—free double curves, suave or soft; opalescent harmonies of colouring; reminiscences, with quite a new feeling, of Egypt, Chaldea, Greece and the East, or of the art of the Renaissance; and infinite variety of floral forms even of the humblest. He introduces also the female nude in the form of sirens and sphinxes. As a craftsman he has effected a radical change, breaking through old routine, combining all the processes of the goldsmith, the chaser, the enameller and the gem-setter, and freeing himself from the narrow lines in which the art had been confined. He ignores the hierarchy of gems, caring no more on occasion for a diamond than for a flint, since, in his view, no stone, whatever its original estimation, has any value beyond the characteristic expression he lends it as a means to his end. Thus, while he sometimes uses diamonds, rubies, sapphires or emeralds as a background, he will, on the other hand, give a conspicuous position to common stones—carnelian, agate, malachite, jasper, coral, and even materials of no intrinsic value, such as horn. One of his favourite stones is the opal, which lends itself to his arrangements of colour, and which has in consequence become a fashionable stone in French jewelry.

In criticism of the art of Lalique and his school it should be observed that the works of the school are apt to be unsuited to the wear and tear of actual use, and inconveniently eccentric in their details. Moreover, the preciousness of the material is an almost inevitable consideration in the jeweller’s craft, and cannot be set at naught by the artist without violating the canons of his art.

The movement which took its rise in France spread in due course to other countries. In England the movement conveniently described as the “arts and crafts movement” affected the design of jewelry. A group of designers has aimed at purging the jeweller’s craft of its character of mere gem-mounting in conventional forms (of which the more unimaginative, representing stars, bows, flowers and the like, are varied by such absurdities as insects, birds, animals, figures of men and objects made up simply of stones clustered together). Their work is often excellently and fancifully designed, but it lacks that exquisite perfection of execution achieved by the incomparable craftsmen of France. At the same time English sculptor-decorators—such as Alfred Gilbert, R.A., and George J. Frampton, A.R.A.—have produced objects of a still higher class, but it is usually the work of the goldsmith rather than of the jeweller. Examples may be seen in the badge executed by Gilbert for the president of the Institute of Painters in Water Colours and in the mayoral chain for Preston. Symbolism here enters into the design, which has not only an ornamental but a didactic purpose.

The movement was represented in other countries also. In the United States it was led by L. C. Tiffany, in Belgium by Philippe Wolfers, who occupies in Belgium the position which in France is held by René Lalique. If his design is a little heavier, it is not less beautiful in imagination or less masterly in execution. Graceful, ingenious, fanciful, elegant, fantastic by turns, his objects of jewelry and goldsmithery have a solid claim to be considered créations d’art. It has also been felt in Germany, Austria, Russia and Switzerland. It must be admitted that many of the best artists who have devoted themselves to jewelry have been more successful in design than in securing the lightness and strength which are required by the wearer, and which were a characteristic in the works of the Italian craftsmen of the Renaissance. For this reason many of their masterpieces are more beautiful in the case than upon the person.

Modern Jewelry.—So far we have gone over the progress and results of the jeweller’s art. We have now to speak of the production of jewelry as a modern art industry, in which large numbers of men and women are employed in the larger cities of Europe. Paris, Vienna, London and Birmingham are the most important centres. An illustration of the manufacture as carried on in London and Birmingham will be sufficient to give an insight into the technique and artistic manipulation of this branch of art industry; but, by way of contrast, it may be interesting to give in the first place a description of the native working jeweller of Hindustan.

He travels very much after the fashion of a tinker in England; his budget contains tools, materials, fire pots, and all the requisites of his handicraft. The gold to be used is generally supplied by the patron or employer, and is frequently in gold coin, which the travelling jeweller undertakes to convert into the ornaments required. He squats down in the corner of a courtyard, or under cover of a veranda, lights his fire, cuts up the gold pieces entrusted to him, hammers, cuts, shapes, drills, solders with the blow-pipe, files, scrapes and burnishes until he has produced the desired effect. If he has stones to set or coloured enamels to introduce, he never seems to make a mistake; his instinct for harmony of colour, like that of his brother craftsman the weaver, is as unerring as that of the bird in the construction of its nest. Whether the materials are common or rich and rare, he invariably does the very best possible with them, according to native ideas of beauty in design and combination. It is only when he is interfered with by European dictation that he ever vulgarizes his art or makes a mistake. The result may appear rude in its finish, but the design and the thought are invariably right. We thus see how a trade in the working of which the “plant” is so simple and wants are so readily met could spread itself, as in years past it did at Clerkenwell and at Birmingham before gigantic factories were invented for producing everything under the sun.

It is impossible to find any date at which the systematic production of jewelry was introduced into England. Probably the Clerkenwell trade dates its origin from the revocation of the edict of Nantes, as the skilled artisans in the jewelry, clock and watch, and trinket trades appear to have been descendants of the emigrant Huguenots. The Birmingham trade would appear to have had its origin in the skill to which the workers in fine steel had attained towards the middle and end of the 18th century, a branch of industry which collapsed after the French Revolution.

Modern jewelry may be classified under three heads: (1) objects in which gems and stones form the principal portions, and in which the work in silver, platinum or gold is really only a means for carrying out the design by fixing the gems or stones in the position arranged by the designer, the metal employed being visible only as a setting; (2) when gold work plays an important part in the development of the design, being itself ornamented by engraving (now rarely used) or enamelling or both, the stones and gems being arranged in subordination to the gold work in such positions as to give a decorative effect to the whole; (3) when gold or other metal is alone used, the design being wrought out by hammering in repoussé, casting, engraving, chasing or by the addition of filigree work (see Filigree), or when the surfaces are left absolutely plain but polished and highly finished.

Of course the most ancient and primitive methods are those wholly dependent upon the craft of the workman; but gradually various ingenious processes were invented, by which greater accuracy in the portions to be repeated in a design could be produced with certainty and economy: hence the various methods of stamping used in the production of hand-made jewelry, which are in themselves as much mechanical in relation to the end in view as if the whole object were stamped out at a blow, twisted into its proper position as regards the detail, or the various stamped portions fitted into each other for the mechanical completion of the work. It is therefore rather difficult to draw an absolute line between hand-made and machine-made jewelry, except in extreme cases of hand-made, when everything is worked, so to speak, from the solid, or of machine-made, when the hand has only to give the ornament a few touches of a tool, or fit the parts together if of more than one piece.

The best and most costly hand-made jewelry produced in England, whether as regards gold work, gems, enamelling or engraving, is made in London, and chiefly at Clerkenwell. A design is first made with pencil, sepia or water colour, and when needful with separate enlargement of details, everything in short to make the drawing thoroughly intelligible to the working jeweller. According to the nature and purpose of the design, he cuts out, hammers, files and brings into shape the constructive portions of the work as a basis. Upon this, as each detail is wrought out, he solders, or (more rarely) fixes by rivets, &c., the ornamentation necessary to the effect. The human figure, representations of animal life, leaves, fruit, &c., are modelled in wax, moulded and cast in gold, to be chased up and finished. As the hammering goes on the metal becomes brittle and hard, and then it is passed though the fire to anneal or soften it. In the case of elaborate examples of repoussé, after the general forms are beaten up, the interior is filled with a resinous compound, pitch mixed with fire-brick dust; and this, forming a solid but pliable body underneath the metal, allows of the finished details being wrought out on the front of the design, and being finally completed by chasing. When stones are to be set, or when they form the principal portions of the design, the gold or other metal has to be wrought by hand so as to receive them in little cup-like orifices, these walls of gold enclosing the stone and allowing the edges to be bent over to secure it. Setting is never effected by cement in well-made jewelry. Machine-made settings have in recent years been made, but these are simply cheap imitations of the true hand-made setting. Even strips of gold have been used, serrated at the edges to allow of being easily bent over, for the retention of the stones, true or false.

Great skill and experience are necessary in the proper setting of stones and gems of high value, in order to bring out the greatest amount of brilliancy and colour, and the angle at which a diamond (say) shall be set, in order that the light shall penetrate at the proper point to bring out the “spark” or “flash,” is a subject of grave consideration to the setter. Stones set in a haphazard, slovenly manner, however brilliant in themselves, will look commonplace by the side of skilfully set gems of much less fine quality and water. Enamelling (see Enamel) has of late years largely taken the place of “paste” or false stones.

Engraving is a simple process in itself, and diversity of effect can be produced by skilful manipulation. An interesting variety in the effect of a single ornament may be produced by the combination of coloured gold of various tints. This colouring is a process requiring skill and experience in the manipulation of the materials according to the quality of the gold and the amount of silver alloy in it. The objects to be coloured are dipped in a boiling mixture of salt, alum and saltpetre. Of general colouring it may be said that the object aimed at is to enhance the appearance of the gold by removing the particles of alloy on the surface, and thus allowing the pure gold only to remain visible to the eye. The process has, however, gone much out of fashion. It is apt to rot the solder, and repairs to gold work can be better finished by electro-gilding.

The application of machinery to the economical production of certain classes of jewelry, not necessarily imitations, but as much “real gold” work, to use a trade phrase, as the best hand-made, has been on the increase for many years. Nearly every kind of gold chain now made is manufactured by machinery, and nothing like 371 the beauty of design or perfection of workmanship could be obtained by hand at, probably, any cost. The question therefore in relation to chains is not the mode of manufacture, but the quality of the metal. Eighteen carat gold is of course preferred by those who wear chains, but this is only gold in the proportion of 18 to 24, pure gold being represented by 24. The gold coin of the realm is 22 carat; that is, it contains one-twelfth of alloy to harden it to stand wear and tear. Thus 18 carat gold has one-fourth of alloy, and so on with lower qualities down to 12, which is in reality only gold by courtesy. It must be remembered that the alloys are made by weight, and as gold is nearly twice as heavy as the metal it is mixed with, it only forms a third of the bulk of a 12 carat mixture.

The application of machinery to the production of personal ornaments in gold and silver can only be economically and successfully carried on when there is a large demand for similar objects, that is to say, objects of precisely the same design and decoration throughout. In machine-made jewelry everything is stereotyped, so to speak, and the only work required for the hand is to fit the parts together—in some instances scarcely that. A design is made, and from it steel dies are sunk for stamping out as rapidly as possible from a plate of rolled metal the portion represented by each die. It is in these steel dies that the skill of the artist die-sinker is manifested. Brooches, ear-rings, pinheads, bracelets, lockets, pendants, &c., are struck out by the gross. This is more especially the case in silver and in plated work—that is, imitation jewelry—the base of which is an alloy, afterwards gilt by electro-plating. With these ornaments imitation stones in paste and glass, pearls, &c., are used, and it is remarkable that of late years some of the best designs, the most simple, appropriate and artistic, have appeared in imitation jewelry. It is only just to those engaged in this manufacture to state distinctly that their work is never sold wholesale for anything else than what it is. The worker in gold only makes gold or real jewelry, and he only makes of a quality well known to his customers. The producer of silver work only manufactures silver ornaments, and so on throughout the whole class of plated goods.

It is the retailer who, if he is unprincipled, takes advantage of the ignorance of the buyer and sells for gold that which is in reality an imitation, and which he bought as such. The imitations of old styles of jewelry which are largely sold in curiosity shops at foreign places of fashionable resort are said to be made in Germany, especially at Munich.

Bibliography.—For the Dāhshur jewels, see J. de Morgan and others; Fouilles à Dahchour, Mars-Juin 1894 (Vienna, 1895) and Fouilles à Dahchour en 1894-1895 (Vienna, 1903). For the Aah-hotep jewels, see Mariette, Album de Musée de Boulaq, pls. 29-31; Birch, Facsimiles of the Egyptian Relics discovered in the Tomb of Queen Aah-hotep (1863). For Cretan excavations, see A. J. Evans, in Annual of the British School at Athens, Nos. 7 to 11; Archaeologia, vol. lix. For excavations at Enkomi, see Excavations in Cyprus, by A. S. Murray and others (1900). For Schliemann’s excavations, see Schliemann’s works; also Schuchhardt, Schliemann’s Excavations; Perrot & Chipiez, Histoire de l’Art, vi. For the Greek Island treasure, see A. J. Evans, Journal of Hellenic Studies, xiii. For Ephesus gold treasure, see D. G. Hogarth, British Museum Excavations at Ephesus; The Archaic Artemisia. For the Hermitage Collection from South Russia, see Gillé, Antiquités du Bosphore Cimmérien (reissued by S. Reinach), and the Comptes rendus of the Russian Archaeological Commission (St Petersburg). For later jewelry, Pollak, Goldschmiedearbeit. For Treasure of Pétrossa, A. Odobesco, Le Trésor de Pétrossa. For the European and west Asiatic barbaric jewelry, see O. M. Dalton, in Archaeologia, lviii. 237, and the Treasure of the Oxus (British Museum, 1905). For the whole history, G. Fontenay, Les Bijoux anciens et modernes (Paris [Quantin], 1887). For the recent movement, Léonce Bénédite, “La Bijouterie et la joaillerie, à l’exposition universelle; René Lalique,” in the Revue des arts décoratifs, 1900 (July, August).

JEWETT, SARAH ORNE (1840-1909), American novelist, was born in South Berwick, Maine, on the 3rd of September 1849. She was a daughter of the physician Theodore H. Jewett (1815-1878), by whom she was greatly influenced, and whom she has drawn in A Country Doctor (1884). She studied at the Berwick Academy, and began her literary career in 1869, when she contributed her first story to the Atlantic Monthly. Her best work consists of short stories and sketches, such as those in The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896). The People of Maine, with their characteristic speech, manners and traditions, she describes with peculiar charm and realism, often recalling the work of Hawthorne. She died at South Berwick, Maine, on the 24th of June 1909.

Among her publications are: Deephaven (1877), a series of sketches; Old Friends and New (1879); Country By-ways (1881); A Country Doctor (1884), a novel; A Marsh Island (1885), a novel; A White Heron and other Stories (1886); The King of Folly Island and other People (1888); Strangers and Wayfarers (1890); A Native of Winby and other Tales (1893); The Queen’s Twin and other Stories (1899), and The Tory Lover (1901), an historical novel.

JEWS (Heb. Yehūdi, man of Judah; Gr. Ἰουδαῖοι; Lat. Judaei), the general name for the Semitic people which inhabited Palestine from early times, and is known in various connexions as “the Hebrews,” “the Jews,” and “Israel” (see § 5 below). Their history may be divided into three great periods: (1) That covered by the Old Testament to the foundation of Judaism in the Persian age, (2) that of the Greek and Roman domination to the destruction of Jerusalem, and (3) that of the Diaspora or Dispersion to the present day.

I.—Old Testament History