Project Gutenberg's The Mayflower and Her Log, Complete, by Azel Ames This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Mayflower and Her Log, Complete Author: Azel Ames Release Date: October 7, 2006 [EBook #4107] Last Updated: August 24, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAYFLOWER AND LOG *** Produced by David Widger

“Next to the fugitives whom Moses led out of Egypt, the little shipload of outcasts who landed at Plymouth are destined to influence the future of the world."

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

O civilized humanity, world-wide, and especially to the descendants of the Pilgrims who, in 1620, laid on New England shores the foundations of that civil and religious freedom upon which has been built a refuge for the oppressed of every land, the story of the Pilgrim “Exodus” has an ever-increasing value and zest. The little we know of the inception, development, and vicissitudes of their bold scheme of colonization in the American wilderness only serves to sharpen the appetite for more.

Every detail and circumstance which relates to their preparations; to the ships which carried them; to the personnel of the Merchant Adventurers associated with them, and to that of the colonists themselves; to what befell them; to their final embarkation on their lone ship,—the immortal MAY-FLOWER; and to the voyage itself and to its issues, is vested to-day with, a supreme interest, and over them all rests a glamour peculiarly their own.

For every grain of added knowledge that can be gleaned concerning the Pilgrim sires from any field, their children are ever grateful, and whoever can add a well-attested line to their all-too-meagre annals is regarded by them, indeed by all, a benefactor.

Of those all-important factors in the chronicles of the “Exodus,”—the Pilgrim ships, of which the MAY-FLOWER alone crossed the seas,—and of the voyage itself, there is still but far too little known. Of even this little, the larger part has not hitherto been readily accessible, or in form available for ready reference to the many who eagerly seize upon every crumb of new-found data concerning these pious and intrepid Argonauts.

To such there can be no need to recite here the principal and familiar facts of the organization of the English “Separatist” congregation under John Robinson; of its emigration to Holland under persecution of the Bishops; of its residence and unique history at Leyden; of the broad outlook of its members upon the future, and their resultant determination to cross the sea to secure larger life and liberty; and of their initial labors to that end. We find these Leyden Pilgrims in the early summer of 1620, their plans fairly matured and their agreements between themselves and with their merchant associates practically concluded, urging forward their preparations for departure; impatient of the delays and disappointments which befell, and anxiously seeking shipping for their long and hazardous voyage.

It is to what concerns their ships, and especially that one which has passed into history as “the Pilgrim bark,” the MAY-FLOWER, and to her pregnant voyage, that the succeeding chapters chiefly relate. In them the effort has been made to bring together in sequential relation, from many and widely scattered sources, everything germane that diligent and faithful research could discover, or the careful study and re-analysis of known data determine. No new and relevant item of fact discovered, however trivial in itself, has failed of mention, if it might serve to correct, to better interpret, or to amplify the scanty though priceless records left us, of conditions, circumstances, and events which have meant so much to the world.

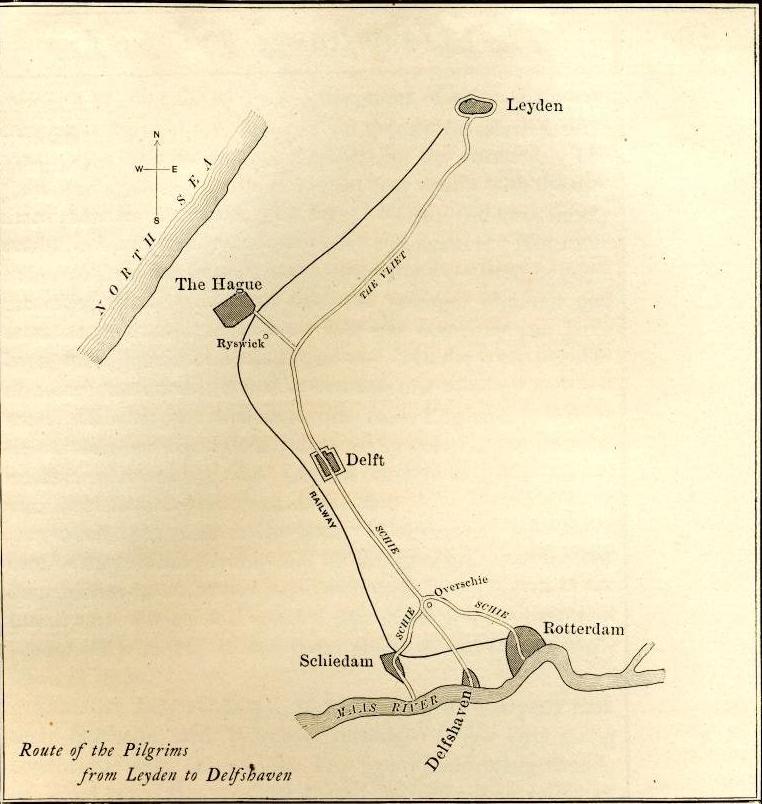

As properly antecedent to the story of the voyage of the MAY-FLOWER as told by her putative “Log,” albeit written up long after her boned lay bleaching on some unknown shore, some pertinent account has been given of the ship herself and of her “consort,” the SPEEDWELL; of the difficulties attendant on securing them; of the preparations for the voyage; of the Merchant Adventurers who had large share in sending them to sea; of their officers and crews; of their passengers and lading; of the troubles that assailed before they had “shaken off the land,” and of the final consolidation of the passengers and lading of both ships upon the MAY-FLOWER, for the belated ocean passage. The wholly negative results of careful search render it altogether probable that the original journal or “Log” of the MAY-FLOWER (a misnomer lately applied by the British press, and unhappily continued in that of the United States, to the recovered original manuscript of Bradford’s “History of Plimoth Plantation “), if such journal ever existed, is now hopelessly lost.

So far as known, no previous effort has been made to bring together in the consecutive relation of such a journal, duly attested and in their entirety, the ascertained daily happenings of that destiny-freighted voyage. Hence, this later volume may perhaps rightly claim to present —and in part to be, though necessarily imperfect—the sole and a true “Log of the MAY-FLOWER.” No effort has been made, however, to reduce the collated data to the shape and style of the ship’s “Log” of recent times, whose matter and form are largely prescribed by maritime law. While it is not possible to give, as the original—if it existed—would have done, the results of the navigators’ observations day by day; the “Lat.” and “Long.”; the variations of the wind and of the magnetic needle; the tallies of the “lead” and “log” lines; “the daily run,” etc.—in all else the record may confidently be assumed to vary little from that presumably kept, in some form, by Captain Jones, the competent Master of the Pilgrim bark, and his mates, Masters Clarke and Coppin.

As the charter was for the “round voyage,” all the features and incidents of that voyage until complete, whether at sea or in port, properly find entry in its journal, and are therefore included in this compilation, which it is hoped may hence prove of reference value to such as take interest in Pilgrim studies. Although the least pleasant to the author, not the least valuable feature of the work to the reader—especially if student or writer of Pilgrim history—will be found, it is believed, in the numerous corrections of previously published errors which it contains, some of which are radical and of much historical importance. It is true that new facts and items of information which have been coming to light, in long neglected or newly discovered documents, etc., are correctives of earlier and natural misconceptions, and a certain percentage of error is inevitable, but many radical and reckless errors have been made in Pilgrim history which due study and care must have prevented. Such errors have so great and rapidly extending power for harm, and, when built upon, so certainly bring the superstructure tumbling to the ground, that the competent and careful workman can render no better service than to point out and correct them wherever found, undeterred by the association of great names, or the consciousness of his own liability to blunder. A sound and conscientious writer will welcome the courteous correction of his error, in the interest of historical accuracy; the opinion of any other need not be regarded.

Some of the new contributions (or original demonstrations), of more or less historical importance, made to the history of the Pilgrims, as the author believes, by this volume, are as follows:—

(a) A closely approximate list of the passengers who left Delfshaven on the SPEEDWELL for Southampton; in other words, the names—those of Carver and Cushman and of the latter’s family being added—of the Leyden contingent of the MAY-FLOWER Pilgrims.

(b) A closely approximate list of the passengers who left London in the MAY-FLOWER for Southampton; in other words, the names (with the deduction of Cushman and family, of Carver, who was at Southampton, and of an unknown few who abandoned the voyage at Plymouth) of the English contingent of the MAY-FLOWER Pilgrims.

(c) The establishment as correct, beyond reasonable doubt, of the date, Sunday, June 11/21, 1620, affixed by Robert Cushman to his letter to the Leyden leaders (announcing the “turning of the tide” in Pilgrim affairs, the hiring of the “pilott” Clarke, etc.), contrary to the conclusions of Prince, Arber, and others, that the letter could not have been written on Sunday.

(d) The demonstration of the fact that on Saturday, June 10/20, 1620, Cushman’s efforts alone apparently turned the tide in Pilgrim affairs; brought Weston to renewed and decisive cooperation; secured the employment of a “pilot,” and definite action toward hiring a ship, marking it as one of the most notable and important of Pilgrim “red-letter days.”

(e) The demonstration of the fact that the ship of which Weston and Cushman took “the refusal,” on Saturday, June 10/20, 1620, was not the MAY-FLOWER, as Young, Deane, Goodwin, and other historians allege.

(f) The demonstration of the fact (overthrowing the author’s own earlier views) that the estimates and criticisms of Robinson, Carver, Brown, Goodwin, and others upon Robert Cushman were unwarranted, unjust, and cruel, and that he was, in fact, second to none in efficient service to the Pilgrims; and hence so ranks in title to grateful appreciation and memory.

(g) The demonstration of the fact that the MAY-FLOWER was not chartered later than June 19/29, 1620, and was probably chartered in the week of June 12/22—June 19/29 of that year.

(h) The addition of several new names to the list of the Merchant Adventurers, hitherto unpublished as such, with considerable new data concerning the list in general.

(i) The demonstration of the fact that Martin and Mullens, of the MAY-FLOWER colonists, were also Merchant Adventurers, while William White was probably such.

(j) The demonstration of the fact that “Master Williamson,” the much-mooted incognito of Bradford’s “Mourt’s Relation” (whose existence even has often been denied by Pilgrim writers), was none other than the “ship’s-merchant,” or “purser” of the MAY-FLOWER,—hitherto unknown as one of her officers, and historically wholly unidentified.

(k) The general description of; and many particulars concerning, the MAY-FLOWER herself; her accommodations (especially as to her cabins), her crew, etc., hitherto unknown.

(1) The demonstration of the fact that the witnesses to the nuncupative will of William Mullens were two of the MAY-FLOWER’S crew (one being possibly the ship’s surgeon), thus furnishing the names of two more of the ship’s company, and the only names—except those of her chief officers—ever ascertained.

(m) The indication of the strong probability that the entire company of the Merchant Adventurers signed, on the one part, the charter-party of the MAY-FLOWER.

(n) An (approximate) list of the ages of the MAY-FLOWER’S passengers and the respective occupations of the adults.

(o) The demonstration of the fact that no less than five of the Merchant Adventurers cast in their lots and lives with the Plymouth Pilgrims as colonists.

(p) The indication of the strong probability that Thomas Goffe, Esquire, one of the Merchant Adventurers, owned the “MAY-FLOWER” when she was chartered for the Pilgrim voyage,—as also on her voyages to New England in 1629 and 1630.

(q) The demonstration of the fact that the Master of the MAY-FLOWER was Thomas Jones, and that there was an intrigue with Master Jones to land the Pilgrims at some point north of the 41st parallel of north latitude, the other parties to which were, not the Dutch, as heretofore claimed, but none other than Sir Ferdinando Gorges and the Earl of Warwick, chiefs of the “Council for New England,” in furtherance of a successful scheme of Gorges to steal the Pilgrim colony from the London Virginia Company, for the more “northern Plantations” of the conspirators.

(r) The demonstration of the fact that a second attempt at stealing the colony—by which John Pierce, one of the Adventurers, endeavored to possess himself of the demesne and rights of the colonists, and to make them his tenants—was defeated only by the intervention of the “Council” and the Crown, the matter being finally settled by compromise and the transfer of the patent by Pierce (hitherto questioned) to the colony.

(s) The demonstration of the actual relations of the Merchant Adventurers and the Pilgrim colonists—their respective bodies being associated as but two partners in an equal copartnership, the interests of the respective partners being (probably) held upon differing bases—contrary to the commonly published and accepted view.

(t) The demonstration of the fact that the MAY-FLOWER—contrary to the popular impression—did not enter Plymouth harbor, as a “lone vessel,” slowly “feeling her way” by chart and lead-line, but was undoubtedly piloted to her anchorage—previously “sounded” for her—by the Pilgrim shallop, which doubtless accompanied her from Cape Cod harbor, on both her efforts to make this haven, under her own sails.

(u) The indication of the strong probability that Thomas English was helmsman of the MAY-FLOWER’S shallop (and so savior of her sovereign company, at the entrance of Plymouth harbor on the stormy night of the landing on Clarke’s Island), and that hence to him the salvation of the Pilgrim colony is probably due; and

(v) Many facts not hitherto published, or generally known, as to the antecedents, relationships, etc., of individual Pilgrims of both the Leyden and the English contingents, and of certain of the Merchant Adventurers.

For convenience’ sake, both the Old Style and the New Style dates of many events are annexed to their mention, and double-dating is followed throughout the narrative journal or “Log” of the Pilgrim ship.

As the Gregorian and other corrections of the calendar are now generally well understood, and have been so often stated in detail in print, it is thought sufficient to note here their concrete results as affecting dates occurring in Pilgrim and later literature.

From 1582 to 1700 the difference between O.S. and N.S. was ten (10) days (the leap-year being passed in 1600). From 1700 to 1800 it was eleven (11) days, because 1700 in O.S. was leap-year. From 1800 to 1900 the difference is twelve (12) days, and from 1900 to 2000 it will be thirteen (13) days. All the Dutch dates were New Style, while English dates were yet of the Old Style.

There are three editions of Bradford’s “History of Plimoth Plantation” referred to herein; each duly specified, as occasion requires. (There is, beside, a magnificent edition in photo-facsimile.) They are:—

(a) The original manuscript itself, now in possession of the State of Massachusetts, having been returned from England in 1897, called herein “orig. MS.”

(b) The Deane Edition (so-called) of 1856, being that edited by the late Charles Deane for the Massachusetts Historical Society and published in “Massachusetts Historical Collections,” vol. iii.; called herein “Deane’s ed.”

(c) The Edition recently published by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and designated as the “Mass. ed.”

Of “Mourt’s Relation” there are several editions, but the one usually referred to herein is that edited by Rev. Henry M. Dexter, D. D., by far the best. Where reference is made to any other edition, it is indicated, and “Dexter’s ed.” is sometimes named.

AZEL AMES.

WAKEFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS, March 1, 1901.

“Hail to thee, poor little ship MAY-FLOWER—of Delft Haven —poor, common-looking ship, hired by common charter-party for coined dollars,—caulked with mere oakum and tar, provisioned with vulgarest biscuit and bacon,—yet what ship Argo or miraculous epic ship, built by the sea gods, was other than a foolish bumbarge in comparison!”

THOMAS CARLYLE

“Curiously enough,” observes Professor Arber, “these names [MAY-FLOWER and SPEEDWELL] do not occur either in the Bradford manuscript or in ‘Mourt’s Relation.’”

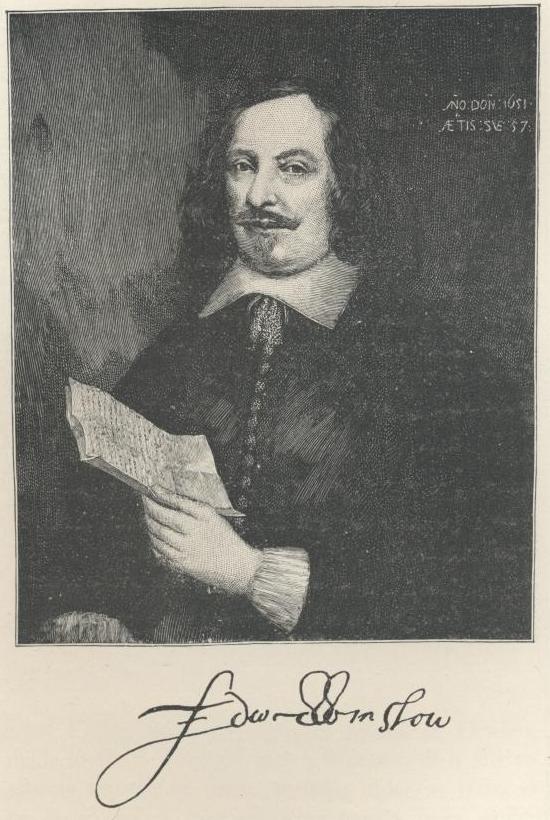

[A Relation, or Journal, of the Beginning and Proceedings of the

English Plantation settled at Plymouth in New England, etc. G.

Mourt, London, 1622. Undoubtedly the joint product of Bradford and

Winslow, and sent to George Morton at London for publication.

Bradford says (op, cit. p. 120): “Many other smaler maters I omite,

sundrie of them having been already published, in a Jurnall made by

one of ye company,” etc. From this it would appear that Mourt’s

Relation was his work, which it doubtless principally was, though

Winslow performed an honorable part, as “Mourt’s” introduction and

other data prove.]

He might have truthfully added that they nowhere appear in any of the letters of the “exodus” period, whether from Carver, Robinson, Cushman, or Weston; or in the later publications of Window; or in fact of any contemporaneous writer. It is not strange, therefore, that the Rev. Mr. Blaxland, the able author of the “Mayflower Essays,” should have asked for the authority for the names assigned to the two Pilgrim ships of 1620.

It seems to be the fact, as noted by Arber, that the earliest authentic evidence that the bark which bore the Pilgrims across the North Atlantic in the late autumn of 1620 was the MAY-FLOWER, is the “heading” of the “Allotment of Lands”—happily an “official” document—made at New Plymouth, New England, in March, 1623—It is not a little remarkable that, with the constantly recurring references to “the ship,”—the all-important factor in Pilgrim history,—her name should nowhere have found mention in the earliest Pilgrim literature. Bradford uses the terms, the “biger ship,” or the “larger ship,” and Winslow, Cushman, Captain John Smith, and others mention simply the “vessel,” or the “ship,” when speaking of the MAY-FLOWER, but in no case give her a name.

It is somewhat startling to find so thorough-paced an Englishman as Thomas Carlyle calling her the MAY-FLOWER “of Delft-Haven,” as in the quotation from him on a preceding page. That he knew better cannot be doubted, and it must be accounted one of those ‘lapsus calami’ readily forgiven to genius,—proverbially indifferent to detail.

Sir Ferdinando Gorges makes the curious misstatement that the Pilgrims had three ships, and says of them: “Of the three ships (such as their weak fortunes were able to provide), whereof two proved unserviceable and so were left behind, the third with great difficulty reached the coast of New England,” etc.

The SPEEDWELL was the first vessel procured by the Leyden Pilgrims for the emigration, and was bought by themselves; as she was the ship of their historic embarkation at Delfshaven, and that which carried the originators of the enterprise to Southampton, to join the MAY-FLOWER, —whose consort she was to be; and as she became a determining factor in the latter’s belated departure for New England, she may justly claim mention here as indeed an inseparable “part and parcel” of the MAY-FLOWER’S voyage.

The name of this vessel of associate historic renown with the MAY-FLOWER was even longer in finding record in the early literature of the Pilgrim hegira than that of the larger It first appeared, so far as discovered, in 1669—nearly fifty years after her memorable service to the Pilgrims on the fifth page of Nathaniel Morton’s “New England’s Memorial.”

Davis, in his “Ancient Landmarks of Plymouth,” makes a singular error for so competent a writer, when he says: “The agents of the company in England had hired the SPEEDWELL, of sixty tons, and sent her to Delfthaven, to convey the colonists to Southampton.” In this, however, he but follows Mather and the “Modern Universal History,” though both are notably unreliable; but he lacks their excuse, for they were without his access to Bradford’s “Historie.” That the consort-pinnace was neither “hired” nor “sent to Delfthaven” duly appears.

Bradford states the fact,—that “a smale ship (of some 60 tune), was bought and fitted in Holand, which was intended to serve to help to transport them, so to stay in ye countrie and atend ye fishing and such other affairs as might be for ye good and benefite of ye colonie when they come ther.” The statements of Bradford and others indicate that she was bought and refitted with moneys raised in Holland, but it is not easy to understand the transaction, in view of the understood terms of the business compact between the Adventurers and the Planters, as hereinafter outlined. The Merchant Adventurers—who were organized (but not incorporated) chiefly through the activity of Thomas Weston, a merchant of London, to “finance” the Pilgrim undertaking—were bound, as part of their engagement, to provide the necessary shipping,’ etc., for the voyage. The “joint-stock or partnership,” as it was called in the agreement of the Adventurers and Planters, was an equal partnership between but two parties, the Adventurers, as a body, being one of the co-partners; the Planter colonists, as a body, the other. It was a partnership to run for seven years, to whose capital stock the first-named partner (the Adventurers) was bound to contribute whatever moneys, or their equivalents,—some subscriptions were paid in goods, —were necessary to transport, equip, and maintain the colony and provide it the means of traffic, etc., for the term named. The second-named partner (the Planter body) was to furnish the men, women, and children, —the colonists themselves, and their best endeavors, essential to the enterprise,—and such further contributions of money or provisions, on an agreed basis, as might be practicable for them. At the expiration of the seven years, all properties of every kind were to be divided into two equal parts, of which the Adventurers were to take one and the Planters the other, in full satisfaction of their respective investments and claims. The Adventurers’ half would of course be divided among themselves, in such proportion as their individual contributions bore to the sum total invested. The Planters would divide their half among their number, according to their respective contributions of persons, money, or provisions, as per the agreed basis, which was:

[Bradford’s Historie, Deane’s ed.; Arber, op. cit. p. 305.

The fact that Lyford (Bradford, Historie, Mass. ed. p. 217)

recommended that every “particular” (i.e. non-partnership colonist)

sent out by the Adventurers—and they had come to be mostly of that

class—“should come over as an Adventurer, even if only a servant,”

and the fact that he recognized that some one would have to pay in

L10 to make each one an Adventurer, would seem to indicate that any

one was eligible and that either L10 was the price of the Merchant

Adventurer’s share, or that this was the smallest subscription which

would admit to membership. Such “particular,” even although an

Adventurer, had no partnership share in the Planters’ half-interest;

had no voice in the government, and no claim for maintenance. He

was, however, amenable to the government, subject to military duty

and to tax. The advantage of being an Adventurer without a voice in

colony affairs would be purely a moral one.]

that every person joining the enterprise, whether man, woman, youth,

maid, or servant, if sixteen years old, should count as a share; that a

share should be reckoned at L10, and hence that L10 worth of money or

provisions should also count as a share. Every man, therefore, would be

entitled to one share for each person (if sixteen years of age) he

contributed, and for each L10 of money or provisions he added thereto,

another share. Two children between ten and sixteen would count as one and

be allowed a share in the division, but children under ten were to have

only fifty acres of wild land. The scheme was admirable for its equity,

simplicity, and elasticity, and was equally so for either capitalist or

colonist.

Goodwin notes, that, “in an edition of Cushman’s ‘Discourse,’ Judge Davis of Boston advanced the idea that at first the Pilgrims put all their possessions into a common stock, and until 1623 had no individual property. In his edition of Morton’s ‘Memorial’ he honorably admits his error.” The same mistake was made by Robertson and Chief Justice Marshall, and is occasionally repeated in this day. “There was no community of goods, though there was labor in common, with public supplies of food and clothing.” Neither is there warrant for the conclusion of Goodwin, that because the holdings of the Planters’ half interest in the undertaking were divided into L10 shares, those of the Adventurers were also. It is not impossible, but it does not necessarily follow, and certain known facts indicate the contrary.

Rev. Edward Everett Hale, in “The Pilgrims’ Life in Common,” says: “Carver, Winslow, Bradford, Brewster, Standish, Fuller, and Allerton. were the persons of largest means in the Leyden group of the emigrants. It seems as if their quota of subscription to the common stock were paid in ‘provisions’ for the voyage and the colony, and that by ‘provisions’ is meant such articles of food as could be best bought in Holland.” The good Doctor is clearly in error, in the above. Allerton was probably as “well off” as any of the Leyden contingent, while Francis Cooke and Degory Priest were probably “better off” than either Brewster or Standish, who apparently had little of this world’s goods. Neither is there any evidence that any considerable amount of “provision” was bought in Holland. Quite a large sum of money, which came, apparently, from the pockets of the Leyden Adventurers (Pickering, Greene, etc.), and some of the Pilgrims, was requisite to pay for the SPEEDWELL and her refitting, etc.; but how much came from either is conjectural at best. But aside from “Hollands cheese,” “strong-waters” (schnapps), some few things that Cushman names; and probably a few others, obtained in Holland, most of the “provisioning,” as repeatedly appears, was done at the English Southampton. In fact, after clothing and generally “outfitting” themselves, it is pretty certain that but few of the Leyden party had much left. There was evidently an understanding between the partners that there should be four principal agents charged with the preparations for, and carrying out of, the enterprise,—Thomas Weston and Christopher Martin representing the Adventurers and the colonists who were recruited in England (Martin being made treasurer), while Carver and Cushman acted for the Leyden company. John Pierce seems to have been the especial representative of the Adventurers in the matter of the obtaining of the Patent from the (London) Virginia Company, and later from the Council for New England. Bradford says: “For besides these two formerly mentioned, sent from Leyden, viz., Master Carver and Robert Cushman, there was one chosen in England to be joyned with them, to make the provisions for the Voyage. His name was Master Martin. He came from Billerike in Essexe; from which parts came sundry others to go with them; as also from London and other places, and therefore it was thought meet and convenient by them in Holand, that these strangers that were to goe with them, should appointe one thus to be joyned with them; not so much from any great need of their help as to avoid all susspition, or jealosie, of any partialitie.” But neither Weston, Martin, Carver, nor Cushman seems to have been directly concerned in the purchase of the SPEEDWELL. The most probable conjecture concerning it is, that in furtherance of the purpose of the Leyden leaders, stated by Bradford, that there should be a small vessel for their service in fishing, traffic, etc., wherever they might plant the colony, they were permitted by the Adventurers to purchase the SPEEDWELL for that service, and as a consort, “on general account.”

It is evident, however, from John Robinson’s letter of June 14, 1620, to John Carver, that Weston ridiculed the transaction, probably on selfish grounds, but, as events proved, not without some justification.

Robinson says: “Master Weston makes himself merry with our endeavors about buying a ship,” [the SPEEDWELL] “but we have done nothing in this but with good reason, as I am persuaded.” Although bought with funds raised in Holland,

[Arber (The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers, p. 341) arrives at the

conclusion that “The SPEEDWELL had been bought with Leyden money.

The proceeds of her sale, after her return to London, would, of

course, go to the credit of the common joint-Stock there.” This

inference seems warranted by Robinson’s letter of June 16/26 to

Carver, in which he clearly indicates that the Leyden brethren

collected the “Adventurers” subscriptions of Pickering and his

partner (Greene), which were evidently considerable.]

it was evidently upon “joint-account,” and she was doubtless so

sold, as alleged, on her arrival in September, at London, having proved

unseaworthy. In fact, the only view of this transaction that harmonizes

with the known facts and the respective rights and relations of the

parties is, that permission was obtained (perhaps through Edward

Pickering, one of the Adventurers, a merchant of Leyden, and others) that

the Leyden leaders should buy and refit the consort, and in so doing might

expend the funds which certain of the Leyden Pilgrims were to pay into the

enterprise, which it appears they did,—and for which they would

receive, as shown, extra shares in the Planters’ half-interest. It was

very possibly further permitted by the Adventurers, that Mr. Pickering’s

and his partners’ subscriptions to their capital stock should be applied

to the purchase of the SPEEDWELL, as they were collected by the Leyden

leaders, as Pastor Robinson’s letter of June 14/24 to John Carver,

previously noted, clearly shows.

She was obviously bought some little time before May 31, 1620,—probably in the early part of the month,—from the fact that in their letter of May 31st to Carver and Cushman, then in London, Messrs. Fuller, Winslow, Bradford, and Allerton state that “we received divers letters at the coming of Master Nash and our Pilott,” etc. From this it is clear that time enough had elapsed, since their purchase of the pinnace, for their messenger (Master Nash) to go to London,—evidently with a request to Carver and Cushman that they would send over a competent “pilott” to refit her, and for Nash to return with him, while the letter announcing their arrival does not seem to have been immediately written.

The writers of the above-mentioned letter use the words “we received,” —using the past tense, as if some days before, instead of “we have your letters,” or “we have just received your letters,” which would rather indicate present, or recent, time. Probably some days elapsed after the “pilott’s” arrival, before this letter of acknowledgment was sent. It is hence fair to assume that the pinnace was bought early in May, and that no time was lost by the Leyden party in preparing for the exodus, after their negotiations with the Dutch were “broken off” and they had “struck hands” with Weston, sometime between February 2/12, 1619/20, and April 1/11, 1620,—probably in March.

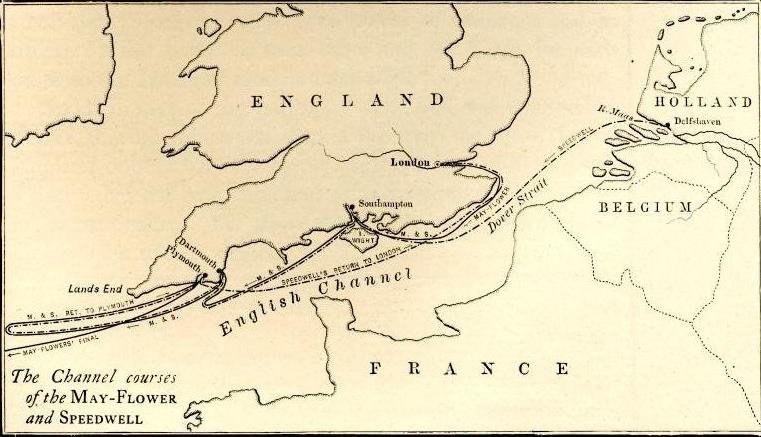

The consort was a pinnace—as vessels of her class were then and for many years called—of sixty tons burden, as already stated, having two masts, which were put in—as we are informed by Bradford, and are not allowed by Professor Arber to forget—as apart of her refitting in Holland. That she was “square-rigged,” and generally of the then prevalent style of vessels of her size and class, is altogether probable. The name pinnace was applied to vessels having a wide range in tonnage, etc., from a craft of hardly more than ten or fifteen tons to one of sixty or eighty. It was a term of pretty loose and indefinite adaptation and covered most of the smaller craft above a shallop or ketch, from such as could be propelled by oars, and were so fitted, to a small ship of the SPEEDWELL’S class, carrying an armament.

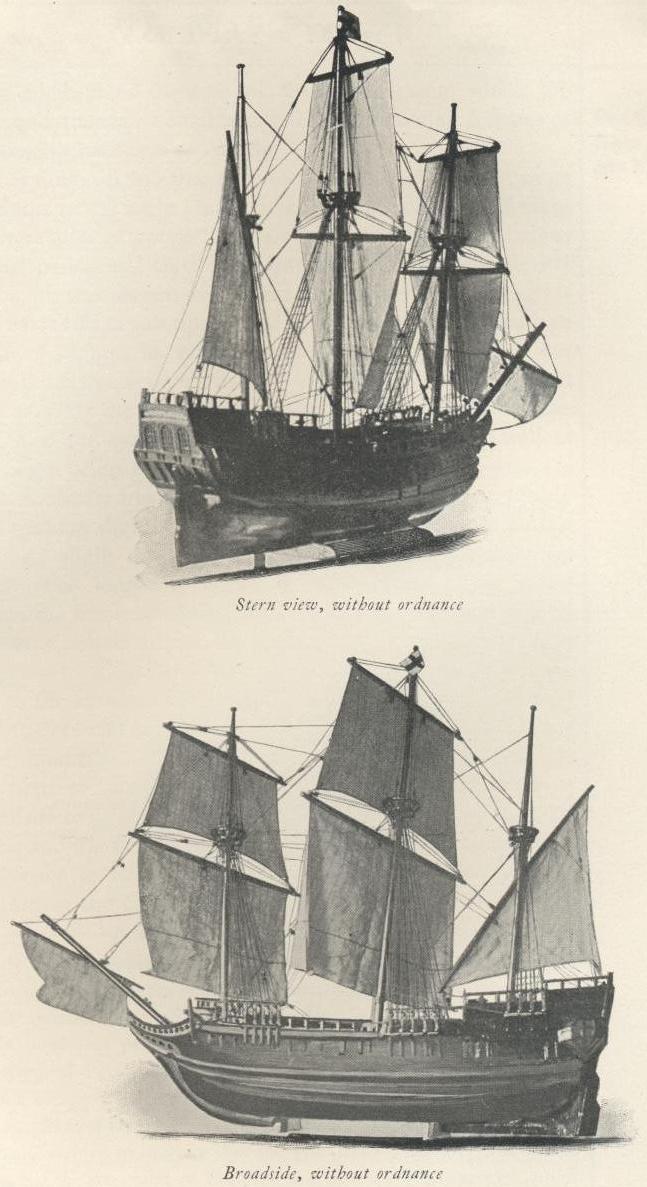

None of the many representations of the SPEEDWELL which appear in historical pictures are authentic, though some doubtless give correct ideas of her type. Weir’s painting of the “Embarkation of the Pilgrims,” in the Capitol at Washington (and Parker’s copy of the same in Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth); Lucy’s painting of the “Departure of the Pilgrims,” in Pilgrim Hall; Copes great painting in the corridor of the British Houses of Parliament, and others of lesser note, all depict the vessel on much the same lines, but nothing can be claimed for any of them, except fidelity to a type of vessel of that day and class. Perhaps the best illustration now known of a craft of this type is given in the painting by the Cuyps, father and son, of the “Departure of the Pilgrims from Delfshaven,” as reproduced by Dr. W. E. Griffis, as the frontispiece to his little monograph, “The Pilgrims in their Three Homes.” No reliable description of the pinnace herself is known to exist, and but few facts concerning her have been gleaned. That she was fairly “roomy” for a small number of passengers, and had decent accommodations, is inferable from the fact that so many as thirty were assigned to her at Southampton, for the Atlantic voyage (while the MAY-FLOWER, three times her tonnage, but of greater proportionate capacity, had but ninety), as also from the fact that “the chief [i.e. principal people] of them that came from Leyden went in this ship, to give Master Reynolds content.” That she mounted at least “three pieces of ordnance” appears by the testimony of Edward Winslow, and they probably comprised her armament.

We have seen that Bradford notes the purchase and refitting of this “smale ship of 60 tune” in Holland. The story of her several sailings, her “leakiness,” her final return, and her abandonment as unseaworthy, is familiar. We find, too, that Bradford also states in his “Historie,” that “the leakiness of this ship was partly by her being overmasted and too much pressed with sails.” It will, however, amaze the readers of Professor Arber’s generally excellent “Story of the Pilgrim Fathers,” so often referred to herein, to find him sharply arraigning “those members of the Leyden church who were responsible for the fitting of the SPEEDWELL,” alleging that “they were the proximate causes of most of the troubles on the voyage [of the MAY-FLOWER] out; and of many of the deaths at Plymouth in New England in the course of the following Spring; for they overmasted the vessel, and by so doing strained her hull while sailing.” To this straining, Arber wholly ascribes the “leakiness” of the SPEEDWELL and the delay in the final departure of the MAYFLOWER, to which last he attributes the disastrous results he specifies. It would seem that the historian, unduly elated at what he thought the discovery of another “turning-point of modern history,” endeavors to establish it by such assertions and such partial references to Bradford as would support the imaginary “find.” Briefly stated, this alleged discovery, which he so zealously announces, is that if the SPEEDWELL had not been overmasted, both she and the MAY-FLOWER would have arrived early in the fall at the mouth of the Hudson River, and the whole course of New England history would have been entirely different. Ergo, the “overmasting” of the SPEEDWELL was a “pivotal point in modern history.” With the idea apparently of giving eclat to this announcement and of attracting attention to it, he surprisingly charges the responsibility for the “overmasting” and its alleged dire results upon the leaders of the Leyden church, “who were,” he repeatedly asserts, “alone responsible.” As a matter of fact, however, Bradford expressly states (in the same paragraph as that upon which Professor Arber must wholly base his sweeping assertions) that the “overmasting” was but “partly” responsible for the SPEEDWELL’S leakiness, and directly shows that the “stratagem” of her master and crew, “afterwards,” he adds, “known, and by some confessed,” was the chief cause of her leakiness.

Cushman also shows, by his letter,—written after the ships had put back into Dartmouth,—a part of which Professor Arber uses, but the most important part suppresses, that what he evidently considers the principal leak was caused by a very “loose board” (plank), which was clearly not the result of the straining due to “crowding sail,” or of “overmasting.” (See Appendix.)

Moreover, as the Leyden chiefs were careful to employ a presumably competent man (“pilott,” afterwards “Master” Reynolds) to take charge of refitting the consort, they were hence clearly, both legally and morally, exempt from responsibility as to any alterations made. Even though the “overmasting” had been the sole cause of the SPEEDWELL’S leakiness, and the delays and vicissitudes which resulted to the MAY-FLOWER and her company, the leaders of the Leyden church—whom Professor Arber arraigns —(themselves chiefly the sufferers) were in no wise at fault! It is clear, however, that the “overmasting” cut but small figure in the case; “confessed” rascality in making a leak otherwise, being the chief trouble, and this, as well as the “overmasting,” lay at the door of Master Reynolds.

Even if the MAY-FLOWER had not been delayed by the SPEEDWELL’S condition, and both had sailed for “Hudson’s River” in midsummer, it is by no means certain that they would have reached there, as Arber so confidently asserts. The treachery of Captain Jones, in league with Gorges, would as readily have landed them, by some pretext, on Cape Cod in October, as in December. But even though they had landed at the mouth of the Hudson, there is no good reason why the Pilgrim influence should not have worked north and east, as well as it did west and south, and with the Massachusetts Bay Puritans there, Roger Williams in Rhode Island, and the younger Winthrop in Connecticut, would doubtless have made New England history very much what it has been, and not, as Professor Arber asserts, “entirely different.”

The cruel indictment fails, and the imaginary “turning point in modern history,” to announce which Professor Arber seems to have sacrificed so much, falls with it.

The Rev. Dr. Griffis (“The Pilgrims in their Three Homes,” p. 158) seems to give ear to Professor Arber’s untenable allegations as to the Pilgrim leaders’ responsibility for any error made in the “overmasting” of the SPEEDWELL, although he destroys his case by saying of the “overmasting:” “Whether it was done in England or Holland is not certain.” He says, unhappily chiming in with Arber’s indictment: “In their eagerness to get away promptly, they [the Leyden men] made the mistake of ordering for the SPEEDWELL heavier and taller masts and larger spars than her hull had been built to receive, thus altering most unwisely and disastrously her trim.” He adds still more unhappily: “We do not hear of these inveterate landsmen and townsfolk [of whom he says, ‘possibly there was not one man familiar with ships or sea life’] who were about to venture on the Atlantic, taking counsel of Dutch builders or mariners as to the proportion of their craft.” Why so discredit the capacity and intelligence of these nation-builders? Was their sagacity ever found unequal to the problems they met? Were the men who commanded confidence and respect in every avenue of affairs they entered; who talked with kings and dealt with statesmen; these diplomats, merchants, students, artisans, and manufacturers; these men who learned law, politics, state craft, town building, navigation, husbandry, boat-building, and medicine, likely to deal negligently or presumptuously with matters upon which they were not informed? Their first act, after buying the SPEEDWELL, was to send to England for an “expert” to take charge of all technical matters of her “outfitting,” which was done, beyond all question, in Holland. What need had they, having done this (very probably upon the advice of those experienced ship-merchants, their own “Adventurers” and townsmen, Edward Pickering and William Greene), to consult Dutch ship-builders or mariners? She was to be an English ship, under the English flag, with English owners, and an English captain; why: should they defer to Dutch seamen or put other than an English “expert” in charge of her alterations, especially when England rightfully boasted the best? But not only were these Leyden leaders not guilty of any laches as indicted by Arber and too readily convicted by Griffis, but the “overmasting” was of small account as compared with the deliberate rascality of captain and crew, in the disabling of the consort, as expressly certified by Bradford, who certainly, as an eye-witness, knew whereof he affirmed.

Having bought a vessel, it was necessary to fit her for the severe service in which she was to be employed; to provision her for the voyage, etc.; and this could be done properly only by experienced hands. The Pilgrim leaders at Leyden seem, therefore, as noted, to have sent to their agents at London for a competent man to take charge of this work, and were sent a “pilott” (or “mate”), doubtless presumed to be equal to the task. Goodwin mistakenly says: “As Spring waned, Thomas Nash went from Leyden to confer with the agents at London. He soon returned with a pilot (doubtless [sic] Robert Coppin), who was to conduct the Continental party to England.” This is both wild and remarkable “guessing” for the usually careful compiler of the “Pilgrim Republic.” There is no warrant whatever for this assumption, and everything contra-indicates it, although two such excellent authorities as Dr. Dexter and Goodwin coincide—the latter undoubtedly copying the former—concerning Coppin; both being doubtless in error, as hereafter shown. Dexter says “My impression is that Coppin was originally hired to go in the SPEEDWELL, and that he was the ‘pilott’ whose coming was ‘a great incouragement’ to the Leyden expectants, in the last of May, or first of June, 1620 [before May 31, as shown]; that he sailed with them in the SPEEDWELL, but on her final putting back was transferred to the MAY-FLOWER.” All the direct light any one has upon the matter comes from the letter of the Leyden brethren of May 31 [O.S.], 1620, previously cited, to Carver and Cushman, and the reply of the latter thereto, of Sunday, June 11, 1620. The former as noted, say: “We received diverse letters at the coming of Master Nash [probably Thomas] and our pilott, which is a great incouragement unto us . . . and indeed had you not sente him [the ‘pilott,’ presumably] many would have been ready to fainte and goe backe.” Neither here nor in any other relation is there the faintest suggestion of Coppin, except as what he was, “the second mate,” or “pilott,” of the MAY-FLOWER. It is not reasonable to suppose that, for so small a craft but just purchased, and with the expedition yet uncertain, the Leyden leaders or their London agents had by June 11, employed both a “Master” and a “pilott” for the SPEEDWELL, as must have been the case if this “pilott” was, as Goodwin so confidently assumes, “doubtless Robert Coppin.” For in Robert Cushman’s letter of Sunday, June 11, as if proposing (now that the larger vessel would be at once obtained, and would, as he thought, be “ready in fourteen days”) that the “pilott” sent over to “refit” the SPEEDWELL should be further utilized, he says: “Let Master Reynolds tarrie there [inferentially, not return here when his work is done, as we originally arranged] and bring the ship [the SPEEDWELL], to Southampton.” The latter service we know he performed.

The side lights upon the matter show, beyond doubt:—

(a) That a “pilott” had been sent to Holland, with Master Nash, before May 31, 1620;

(b) That unless two had been sent (of which there is no suggestion, and which is entirely improbable, for obvious reasons), Master Reynolds was the “pilott” who was thus sent;

(c) That it is clear, from Cushman’s letter of June 11/21, that Reynolds was then in Holland, for Cushman directs that “Master Reynolds tarrie there and bring the ship to Southampton;”

(d) That Master Reynolds was not originally intended to “tarrie there,” and “bring the ship,” etc., as, if he had been, there would have been no need of giving such an order; and

(e) That he had been sent there for some other purpose than to bring the SPEEDWELL to Southampton. Duly considering all the facts together, there can be no doubt that only one “pilott” was sent from England; that he was expected to return when the work was done for which he went (apparently the refitting of the SPEEDWELL); that he was ordered to remain for a new duty, and that the man who performed that duty and brought the ship to Southampton (who, we know was Master Reynolds) must have been the “pilott”, sent over.

We are told too, by Bradford,

[Bradford’s Historie, as already cited; Arber, The Story of the

Pilgrim Fathers, p. 341. John Brown, in his Pilgrim Fathers of New

England, p. 198, says: “She [the SPEEDWELL] was to remain with the

colony for a year.” Evidently a mistake, arising from the length of

time for which her crew were shipped. The pinnace herself was

intended, as we have seen, for the permanent use of they colonists,

and was to remain indefinitely.]

that the crew of the SPEEDWELL “were hired for a year,” and we know,

in a general way, that most of them went with her to London when she

abandoned the voyage. This there is ample evidence Coppin did not do,

going as he did to New England as “second mate” or “pilott” of the

MAY-FLOWER, which there is no reason to doubt he was when she left London.

Neither is there anywhere any suggestion that there was at Southampton any

change in the second mate of the larger ship, as there must have been to

make good the suggestion of Dr. Dexter.

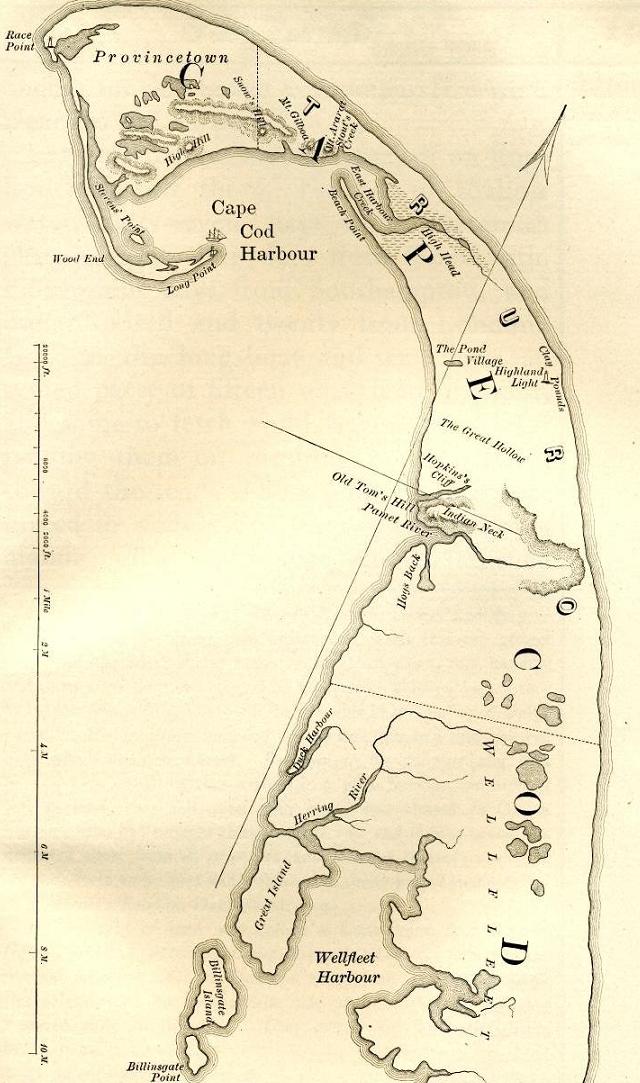

Where the SPEEDWELL lay while being “refitted” has not been ascertained, though presumably at Delfshaven, whence she sailed, though possibly at one of the neighboring larger ports, where her new masts and cordage could be “set up” to best advantage.

We know that Reynolds—“pilott” and “Master” went from London to superintend the “making-ready” for sea. Nothing is known, however, of his antecedents, and nothing of his history after he left the service of the Pilgrims in disgrace, except that he appears to have come again to New England some years later, in command of a vessel, in the service of the reckless adventurer Weston (a traitor to the Pilgrims), through whom, it is probable, he was originally selected for their service in Holland. Bradford and others entitled to judge have given their opinions of this cowardly scoundrel (Reynolds) in unmistakable terms.

What other officers and crew the pinnace had does not appear, and we know nothing certainly of them, except the time for which they shipped; that some of them were fellow-conspirators with the Master (self-confessed), in the “strategem” to compel the SPEEDWELL’S abandonment of the voyage; and that a few were transferred to the MAYFLOWER. From the fact that the sailors Trevore and Ely returned from New Plymouth on the FORTUNE in 1621, “their time having expired,” as Bradford notes, it may be fairly assumed that they were originally of the SPEEDWELL’S crew.

That the fears of the SPEEDWELL’S men had been worked upon, and their cooperation thus secured by the artful Reynolds, is clearly indicated by the statement of Bradford: “For they apprehended that the greater ship being of force and in which most of the provisions were stored, she would retain enough for herself, whatever became of them or the passengers, and indeed such speeches had been cast out by some of them.”

Of the list of passengers who embarked at Delfshaven, July 22, 1620, “bound for Southampton on the English coast, and thence for the northern parts of Virginia,” we fortunately have a pretty accurate knowledge. All of the Leyden congregation who were to emigrate, with the exception of Robert Cushman and family, and (probably) John Carver, were doubtless passengers upon the SPEEDWELL from Delfshaven to Southampton, though the presence of Elder Brewster has been questioned. The evidence that he was there is well-nigh as conclusive as that Robert Cushman sailed on the MAY-FLOWER from London, and that Carver, who had been for some months in England,—chiefly at Southampton, making preparations for the voyage, was there to meet the ships on their arrival. It is possible, of course, that Cushman’s wife and son came on the SPEEDWELL from Delfshaven; but is not probable. Among the passengers, however, were some who, like Thomas Blossom and his son, William Ring, and others, abandoned the voyage to America at Plymouth, and returned in the pinnace to London and thence went back to Holland. Deducting from the passenger list of the MAYFLOWER those known to have been of the English contingent, with Robert Cushman and family, and John Carver, we have a very close approximate to the SPEEDWELL’S company on her “departure from Delfshaven.” It has not been found possible to determine with absolute certainty the correct relation of a few persons. They may have been of the Leyden contingent and so have come with their brethren on the SPEEDWELL, or they may have been of the English colonists, and first embarked either at London or at Southampton, or even at Plymouth,—though none are supposed to have joined the emigrants there or at Dartmouth.

The list of those embarking at Delfshaven on the SPEEDWELL, and so of the participants in that historic event,—a list now published for the first time, so far as known,—is undoubtedly accurate, within the limitations stated, as follows, being for convenience’ sake arranged by families:

The Family of Deacon John Carver (probably in charge of John Howland),

embracing:—

Mrs. Katherine Carver,

John Howland (perhaps kinsman of Carver), “servant” or “employee,”

Desire Minter, or Minther (probably companion of Mrs. Carver,

perhaps kinswoman),

Roger Wilder, “servant,”

“Mrs. Carver’s maid” (whose name has never transpired).

Master William Bradford and

Mrs. Dorothy (May) Bradford.

Master Edward Winslow and

Mrs. Elizabeth (Barker) Winslow,

George Soule a “servant” (or employee),

Elias Story, “servant.”

Elder William Brewster and

Mrs. Mary Brewster,

Love Brewster, a son,

Wrestling Brewster, a son.

Master Isaac Allerton and

Mrs. Mary (Morris) Allerton,

Bartholomew Allerton, a son,

Remember Allerton, a daughter,

Mary Allerton, a daughter,

John Hooke, “servant-boy.”

Dr. Samuel Fuller and

William Butten, “servant"-assistant.

Captain Myles Standish and

Mrs. Rose Standish.

Master William White and

Mrs. Susanna (Fuller) White,

Resolved White, a son,

William Holbeck, “servant,”

Edward Thompson, “servant.”

Deacon Thomas Blossom and

——- Blossom, a son.

Master Edward Tilley and

Mrs. Ann Tilley.

Master John Tilley and

Mrs. Bridget (Van der Velde?) Tilley (2d wife),

Elizabeth Tilley, a daughter of Mr. Tilley by a former wife(?)

John Crackstone and

John Crackstone (Jr.), a son.

Francis Cooke and

John Cooke, a son.

John Turner and

—— Turner, a son,

—— Turner, a son.

Degory Priest.

Thomas Rogers and

Joseph Rogers, a son.

Moses Fletcher.

Thomas Williams.

Thomas Tinker and

Mrs. —— Tinker,

—— Tinker, a son.

Edward Fuller and

Mrs. —— Fuller,

Samuel Fuller, a son.

John Rigdale and

Mrs. Alice Rigdale.

Francis Eaton and

Mrs. —— Eaton,

Samuel Eaton, an infant son.

Peter Browne.

William Ring.

Richard Clarke.

John Goodman.

Edward Margeson.

Richard Britteridge.

Mrs. Katherine Carver and her family, it is altogether probable, came

over in charge of Howland, who was probably a kinsman, both he and

Deacon Carver coming from Essex in England,—as they could hardly

have been in England with Carver during the time of his exacting

work of preparation. He, it is quite certain, was not a passenger

on the Speedwell, for Pastor Robinson would hardly have sent him

such a letter as that received by him at Southampton, previously

mentioned (Bradford’s “Historie,” Deane’s ed. p. 63), if he had been

with him at Delfshaven at the “departure,” a few days before. Nor

if he had handed it to him at Delfshaven, would he have told him in

it, “I have written a large letter to the whole company.”

John Howland was clearly a “secretary” or “steward,” rather than a

“servant,” and a man of standing and influence from the outset.

That he was in Leyden and hence a SPEEDWELL passenger appears

altogether probable, but is not absolutely certain.

Desire Minter (or Minther) was undoubtedly the daughter of Sarah, who,

the “Troth Book” (or “marriage-in-tention” records) for 1616, at the

Stadtbuis of Leyden, shows, was probably wife or widow of one

William Minther—evidently of Pastor Robinson’s congregation—when

she appeared on May 13 as a “voucher” for Elizabeth Claes, who then

pledged herself to Heraut Wilson, a pump-maker, John Carver being

one of Wilson’s “vouchers.” In 1618 Sarah Minther (then recorded as

the widow of William) reappeared, to plight her troth to Roger

Simons, brick-maker, from Amsterdam. These two records and the

rarity of the name warrant an inference that Desire Minter (or

Minther) was the daughter of William and Sarah (Willet) Minter (or

Minther), of Robinson’s flock; that her father had died prior to

1618 (perhaps before 1616); that the Carvers were near friends,

perhaps kinsfolk; that her father being dead, her mother, a poor

widow (there were clearly no rich ones in the Leyden congregation),

placed this daughter with the Carvers, and, marrying herself, and

removing to Amsterdam the year before the exodus, was glad to leave

her daughter in so good a home and such hands as Deacon and Mistress

Carver’s. The record shows that the father and mother of Mrs. Sarah

Minther, Thomas and Alice Willet, the probable grandparents of

Desire Minter, appear as “vouchers” for their daughter at her Leyden

betrothal. Of them we know nothing further, but it is a reasonable

conjecture that they may have returned to England after the

remarriage of their daughter and her removal to Amsterdam, and the

removal of the Carvers and their granddaughter to America, and that

it was to them that Desire went, when, as Bradford records, “she

returned to her friends in England, and proved not very well and

died there.”

“Mrs. Carver’s maid” we know but little about, but the presumption is

naturally strong that she came from; Leyden with her mistress. Her

early marriage and; death are duly recorded.

Roger Wilder, Carver’s “servant;” was apparently in his service at Leyden

and accompanied the family from thence. Bradford calls him “his

[Carver’s] man Roger,” as if an old, familiar household servant,

which (as Wilder died soon after the arrival at Plymouth) Bradford

would not have been as likely to do—writing in 1650, thirty years

after—if he had been only a short-time English addition to Carver’s

household, known to Bradford only during the voyage. The fact that

he speaks of him as a “man” also indicates something as to his age,

and renders it certain that he was not an “indentured” lad. It is

fair to presume he was a passenger on the SPEEDWELL to Southampton.

(It is probable that Carver’s “servant-boy,” William Latham, and

Jasper More, his “bound-boy,” were obtained in England, as more

fully appears.)

Master William Bradford and his wife were certainly of the party in the

SPEEDWELL, as shown by his own recorded account of the embarkation.

(Bradford’s “Historie,” etc.)

Master Edward Winslow’s very full (published) account of the embarkation

(“Hypocrisie Unmasked,” pp. 10-13, etc.) makes it certain that

himself and family were SPEEDWELL passengers.

George Soule, who seems to have been a sort of “upper servant” or

“steward,” it is not certain was with Winslow in Holland, though it

is probable.

Elias Story, his “under-servant,” was probably also with him in Holland,

though not surely so. Both servants might possibly have been

procured from London or at Southampton, but probably sailed from

Delfshaven with Winslow in the SPEEDWELL.

Elder William Brewster and his family, his wife and two boys, were

passengers on the SPEEDWELL, beyond reasonable doubt. He was, in

fact, the ranking man of the Leyden brethren till they reached

Southampton and the respective ships’ “governors” were chosen. The

Church to that point was dominant. (The Elder’s two “bound-boys,”

being from London, do not appear as SPEEDWELL passengers.) There is,

on careful study, no warrant to be found for the remarkable

statements of Goodwin (“Pilgrim Republic,” p. 33), that, during the

hunt for Brewster in Holland in 1619, by the emissaries of James I.

of England (in the endeavor to apprehend and punish him for printing

and publishing certain religious works alleged to be seditious),

“William Brewster was in London . . . and there he remained until

the sailing of the MAYFLOWER, which he helped to fit out;” and that

during that time “he visited Scrooby.” That he had no hand whatever

in fitting out the MAYFLOWER is certain, and the Scrooby statement

equally lacks foundation. Professor Arber, who is certainly a

better authority upon the “hidden press” of the Separatists in

Holland, and the official correspondence relating to its proprietors

and their movements, says (“The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers,”

p.196): “The Ruling Elder of the Pilgrim Church was, for more than a

year before he left Delfshaven on the SPEEDWELL, on the 22 July-

1 August, 1620, a hunted man.” Again (p. 334), he says: “Here let

us consider the excellent management and strategy of this Exodus.

If the Pilgrims had gone to London to embark for America, many, if

not most of them, would have been put in prison [and this is the

opinion of a British historian, knowing the temper of those times,

especially William Brewster.] So only those embarked in London

against whom the Bishops could take no action.” We can understand,

in light, why Carver—a more objectionable person than Cushman to

the prelates, because of his office in the Separatist Church—was

chiefly employed out of their sight, at Southampton, etc., while the

diplomatic and urbane Cushman did effective work at London, under

the Bishops’ eyes. It is not improbable that the personal

friendship of Sir Robert Naunton (Principal Secretary of State to

King James) for Sir Edward Sandys and the Leyden brethren (though

officially seemingly active under his masters’ orders in pushing Sir

Dudley Carleton, the English ambassador at the Hague, to an

unrelenting search for Brewster) may have been of material aid to

the Pilgrims in gaining their departure unmolested. The only basis

known for the positive expression of Goodwin resides in the

suggestions of several letters’ of Sir Dudley Carleton to Sir Robert

Naunton, during the quest for Brewster; the later seeming clearly to

nullify the earlier.

Under date of July 22, 1619, Carleton says: “One William Brewster,

a Brownist, who has been for some years an inhabitant and printer at

Leyden, but is now within these three weeks removed from thence and

gone back to dwell in London,” etc.

On August 16, 1619 (N.S.), he writes: “I am told William Brewster is

come again for Leyden,” but on the 30th adds: “I have made good

enquiry after William Brewster and am well assured he is not

returned thither, neither is it likely he will; having removed from

thence both his family and goods,” etc.

On September 7, 1619 (N.S.), he writes: “Touching Brewster, I am now

informed that he is on this side the seas [not in London, as before

alleged]; and that he was seen yesterday, at Leyden, but, as yet, is

not there settled,” etc.

On September 13, 1619 (N.S.), he says: “I have used all diligence to

enquire after Brewster; and find he keeps most at Amsterdam; but

being ‘incerti laris’, he is not yet to be lighted upon. I

understand he prepares to settle himself at a village called

Leerdorp, not far from Leyden, thinking there to be able to print

prohibited books without discovery, but I shall lay wait for him,

both there and in other places, so as I doubt but either he must

leave this country; or I shall, sooner or later, find him out.”

On September 20, 1619 (N.S.), he says: “I have at length found out

Brewster at Leyden,” etc. It was a mistake, and Brewster’s partner

(Thomas Brewer), one of the Merchant Adventurers, was arrested

instead.

On September 28, 1619 (N.S.), he states, writing from Amsterdam:

“If he lurk here for fear of apprehension, it will be hard to find

him,” etc.

As late as February 8, 1619/20, there was still a desire and hope

for his arrest, but by June the matter had become to the King—and

all others—something of an old story. While, as appears by a

letter of Robert Cushman, written in London, in May, 1619, Brewster

was then undoubtedly there, one cannot agree, in the light of the

official correspondence just quoted, with the conclusion of Dr.

Alexander Young (“Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers,” vol. i.

p. 462), that “it is probable he [Brewster] did not return to

Leyden, but kept close till the MAYFLOWER sailed.”

Everything indicates that he was at Leyden long after this; that he

did not again return to London, as supposed; and that he was in

hiding with his family (after their escape from the pursuit at

Leyden), somewhere among friends in the Low Countries. Although by

July, 1620, the King had, as usual, considerably “cooled off,” we

may be sure that with full knowledge of the harsh treatment meted

out to his partner (Brewer) when caught, though unusually mild (by

agreement with the authorities of the University and Province of

Holland), Brewster did not deliberately put himself “under the

lion’s paw” at London, or take any chances of arrest there, even in

disguise. Dr. Griffis has lent his assent (“The Pilgrims in their

Homes,” p, 167), though probably without careful analysis of all the

facts, to the untenable opinion expressed by Goodwin, that Brewster

was “hiding in England” when the SPEEDWELL sailed from Delfshaven.

There can be no doubt that, with his ever ready welcome of sound

amendment, he will, on examination, revise his opinion, as would the

clear-sighted Goodwin, if living and cognizant of the facts as

marshalled against his evident error. As the leader and guide of

the outgoing part of the Leyden church we may, with good warrant,

believe—as all would wish—that Elder Brewster was the chief figure

the departing Pilgrims gathered on the SPEEDWELL deck, as she took

her departure from Delfshaven.

Master Isaac Allerton and his family, his wife and three children, two

sons and a daughter, were of the Leyden company and passengers in

the SPEEDWELL. We know he was active there as a leader, and was

undoubtedly one of those who bought the SPEEDWELL. He was one of

the signers of the joint-letter from Leyden, to Carver and Cushman,

May 31 (O.S.) 1620.

John Hooke, Allerton’s “servant-lad,” may have been detained at London or

Southampton, but it is hardly probable, as Allerton was a man of

means, consulted his comfort, and would have hardly started so large

a family on such a journey without a servant.

Dr. Samuel Fuller was, as is well known, one of the Leyden chiefs,

connected by blood and marriage with many of the leading families of

Robinson’s congregation. He was active in the preparations for the

voyage the first signer of the joint-letter of May 31, and doubtless

one of the negotiators for the SPEEDWELL. His wife and child were

left behind, to follow later as they did.

William Butten, the first of the Pilgrim party to die, was, in all

probability, a student-“servant” of Doctor Fuller at Leyden, and

doubtless embarked with him at Delfshaven. Bradford calls him

(writing of his death) “Wm. Butten, a youth, servant to Samuel

Fuller.” Captain Myles Standish and his wife Rose, we know from

Bradford, were with the Pilgrims in Leyden and doubtless shipped

with them. Arber calls him (“The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers,”

p. 378) a “chief of the Pilgrim Fathers” in the sense of a father

and leader in their Israel; but there is no warrant for this

assumption, though he became their “sword-hand” in the New World.

By some writers, though apparently with insufficient warrant,

Standish has been declared a Roman Catholic. It does not appear

that he was ever a communicant of the Pilgrim Church. His family,

moreover, was not of the Roman Catholic faith, and all his conduct

in the colony is inconsistent with the idea that he was of that

belief. Master William White, his wife and son, were of the Leyden

congregation, both husband and wife being among its principal

people, and nearly related to several of the Pilgrim band. The

marriage of Mr. and Mrs. White is duly recorded in Leyden. William

Holbeck and Edward Thompson, Master White’s two servants, he

probably took with him from Leyden, as his was a family of means and

position, though they might possibly have been procured at

Southampton. They were apparently passengers in the SPEEDWELL.

Deacon Thomas Blossom and his son were well known as of Pastor

Robinson’s flock at Leyden. They returned, moreover, to Holland

from Plymouth, England (where they gave up the voyage), via London.

The father went to New Plymouth ten years later, the son dying

before that time. (See Blossom’s letter to Governor Bradford.

Bradford’s Letter Book, “Plymouth Church Records,” i. 42.) In his

letter dated at Leyden, December 15, 1625, he says: “God hath taken

away my son that was with me in the ship MAYFLOWER when I went back

again.”

Edward Tilley (sometimes given the prefix of Master) his wife Ann are

known to have been of the Leyden company. (Bradford’s “Historie,”

p. 83.) It is doubtful if their “cousins,” Henry Sampson and

Humility Cooper, were of Leyden. They apparently were English

kinsfolk, taken to New England with the Tilleys, very likely joined

them at Southampton and hence were not of the SPEEDWELL’S

passengers. Humility Cooper returned to England after the death of

Tilley and his wife. That Mrs. Tilley’s “given name” was Ann is not

positively established, but rests on Bradford’s evidence.

John Tilley (who is also sometimes called Master) is reputed a brother of

Edward, and is known to have been—as also his wife—of the Leyden

church (Bradford, Deane’s ed. p. 83.) His second wife Bridget Van

der Velde, was evidently of Holland blood, and their marriage is

recorded in Leyden. Elizabeth Tilley was clearly a daughter by an

earlier wife. He is said by Goodwin (“Pilgrim Republic,” p. 32) to

have been a “silk worker” Leyden, but earlier authority for this

occupation is not found.

John Crackstone is of record as of the Leyden congregation. His daughter

remained there, and came later to America.

John Crackstone, Jr., son of above. Both were SPEEDWELL passengers.

Francis Cooke has been supposed a very early member of Robinson’s flock

in England, who escaped with them to Holland, in 1608. He and his

son perhaps embarked at Delfshaven, leaving his wife and three other

children to follow later. (See Robinson’s letter to Governor

Bradford, “Mass. Hist. Coll.,” vol. iii. p. 45, also Appendix for

account of Cooke’s marriage.)

John Cooke, the son, was supposed to have lived to be the last male

survivor of the MAY-FLOWER, but Richard More proves to have survived

him. He was a prominent man in the colony, like his father, and the

founder of Dartmouth (Mass.).

John Turner and his sons are also known to have been of the Leyden party,

as he was undoubtedly the messenger sent to London with the letter

(of May 31) of the leaders to Carver and Cushman, arriving there

June 10, 1620. They were beyond doubt of the SPEEDWELL’S list.

Degory Priest—or “Digerie,” as Bradford calls him—was a prominent

member of the Leyden body. His marriage is recorded there, and he

left his family in the care of his pastor and friends, to follow him

later. He died early.

Thomas Rogers and his son are reputed of the Leyden company. He left

(according to Bradford) some of his family there—as did Cooke and

Priest—to follow later. It has been suggested that Rogers might

have been of the Essex (England) lineage, but no evidence of this

appears. The Rogers family of Essex were distinctively Puritans,

both in England and in the Massachusetts colony.

Moses Fletcher was a “smith” at Leyden, and of Robinson’s church. He was

married there, in 1613, to his second wife. He was perhaps of the

English Amsterdam family of Separatists, of that name. As the only

blacksmith of the colonists, his early death was a great loss.

Thomas Williams, there seems no good reason to doubt, was the Thomas

Williams known to have been of Leyden congregation. Hon. H. C.

Murphy and Arber include him—apparently through oversight alone

—in the list of those of Leyden who did not go, unless there were

two of the name, one of whom remained in Holland.

Thomas Tinker, wife, and son are not certainly known to have been of the

Leyden company, or to have embarked at Delfshaven, but their

constant association in close relation with others who were and who

so embarked warrants the inference that they were of the SPEEDWELL’S

passengers. It is, however, remotely possible, that they were of

the English contingent.

Edward Fuller and his wife and little son were of the Leyden company, and

on the SPEEDWELL. He is reputed to have been a brother of Dr.

Fuller, and is occasionally so claimed by early writers, but by what

warrant is not clear.

John Rigdale and his wife have always been placed by tradition and

association with the Leyden emigrants but there is a possibility

that they were of the English party. Probability assigns them to

the SPEEDWELL, and they are needed to make her accredited number.

Francis Eaton, wife, and babe were doubtless of the Leyden list. He is

said to have been a carpenter there (Goodwin, “Pilgrim Republic,” p.

32), and was married there, as the record attests.

Peter Browne has always been classed with the Leyden party. There is no

established authority for this except tradition, and he might

possibly have been of the English emigrants, though probably a

SPEEDWELL passenger; he is needed to make good her putative number.

William Ring is in the same category as are Eaton and Browne. Cushman

speaks of him, in his Dartmouth letter to Edward Southworth (of

August 17), in terms of intimacy, though this, while suggestive, of

course proves nothing, and he gave up the voyage and returned from

Plymouth to London with Cushman. He was certainly from Leyden.

Richard Clarke is on the doubtful list, as are also John Goodman, Edward

Margeson, and Richard Britteridge. They have always been

traditionally classed with the Leyden colonists, yet some of them

were possibly among the English emigrants. They are all needed,

however, to make up the number usually assigned to Leyden, as are

all the above “doubtfuls,” which is of itself somewhat confirmatory

of the substantial correctness of the list.

Thomas English, Bradford records, “was hired to goe master of a [the]

shallopp” of the colonists, in New England waters. He was probably

hired in Holland and was almost certainly of the SPEEDWELL.

John Alderton (sometimes written Allerton) was, Bradford states, “a hired

man, reputed [reckoned] one of the company, but was to go back

(being a seaman) and so making no account of the voyages for the

help of others behind” [probably at Leyden]. It is probable that he

was hired in Holland, and came to Southampton on the SPEEDWELL.

Both English and Alderton seem to have stood on a different footing

from Trevore and Ely, the other two seamen in the employ of the

colonists.

William Trevore was, we are told by Bradford, “a seaman hired to stay a

year in the countrie,” but whether or not as part of the SPEEDWELL’S

Crew (who, he tells us, were all hired for a year) does not appear.

As the Master (Reynolds) and others of her crew undoubtedly returned

to London in her from Plymouth, and her voyage was cancelled, the

presumption is that Trevore and Ely were either hired anew or—more

probably—retained under their former agreement, to proceed by the

MAY-FLOWER to America, apparently (practically) as passengers.

Whether of the consort’s crew or not, there can be little doubt that

he left Delfshaven on the SPEEDWELL.

—- Ely, the other seaman in the Planters’ employ, also hired to “remain

a year in the countrie,” appears to have been drafted, like Trevore,

from the SPEEDWELL before she returned to London, having, no doubt,

made passage from Holland in her. Both Trevore and Ely survived

“the general sickness” at New Plimoth, and at the expiration of the

time for which they were employed returned on the FORTUNE to England

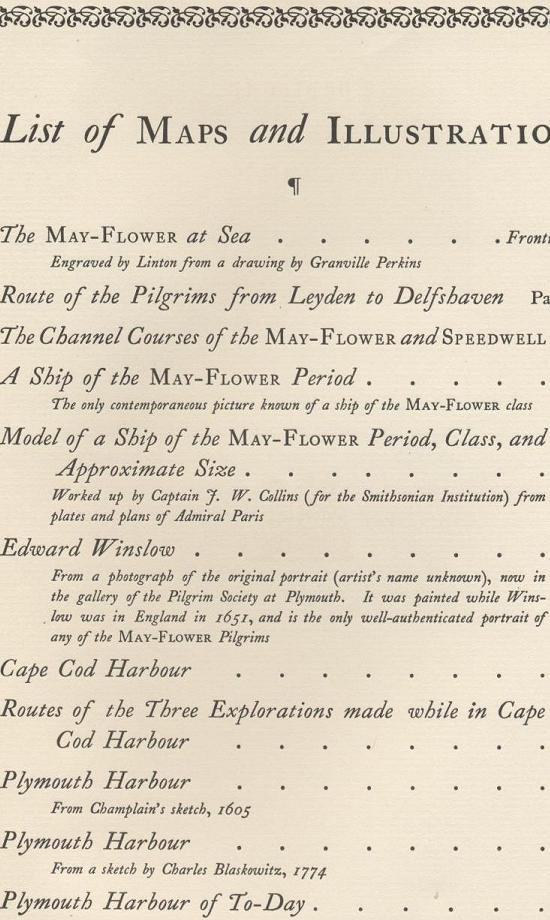

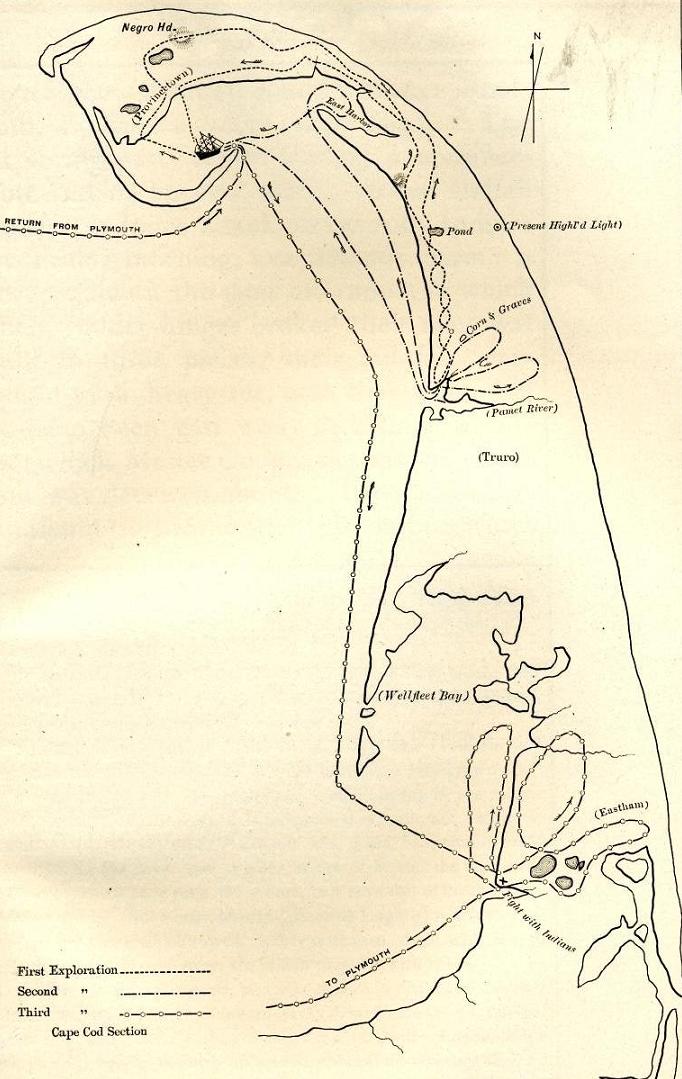

Of course the initial embarkation, on Friday, July 21/31 1620, was at Leyden, doubtless upon the Dutch canal-boats which undoubtedly brought them from a point closely adjacent to Pastor Robinson’s house in the Klock-Steeg (Bell, Belfry, Alley), in the garden of which were the houses of many, to Delfshaven.

Rev. John Brown, D.D., says: “The barges needed for the journey were most likely moored near the Nuns’ Bridge which spans the Rapenburg immediately opposite the Klok-Steeg, where Robinsons house was. This, being their usual meeting-place, would naturally be the place of rendezvous on the morning of departure. From thence it was but a stone’s throw to the boats, and quickly after starting they would enter the Vliet, as the section of the canal between Leyden and Delft is named, and which for a little distance runs within the city bounds, its quays forming the streets. In those days the point where the canal leaves the city was guarded by a water-gate, which has long since been removed, as have also the town walls, the only remaining portions of which are the Morsch-gate and the Zylgate. So, gliding along the quiet waters of the Vliet, past the Water-gate, and looking up at the frowning turrets of the Cow-gate, ‘they left that goodly and pleasant city which had been their resting-place near twelve years.’ . . . Nine miles from Leyden a branch canal connects the Vliet with the Hague, and immediately beyond their junction a sharp turn is made to the left, as the canal passes beneath the Hoom-bridge; from this point, for the remaining five miles, the high road from the Hague to Delft, lined with noble trees, runs side by side with the canal. In our time the canal-boats make a circuit of the town to the right, but in those days the traffic went by canal through the heart of the city . . . . Passing out of the gates of Delft and leaving the town behind, they had still a good ten miles of canal journey before them ere they reached their vessel and came to the final parting, for, as Mr. Van Pelt has clearly shown, it is a mistake to confound Delft with Delfshaven, as the point of embarkation in the SPEEDWELL. Below Delft the canal, which from Leyden thither is the Vliet, then becomes the Schie, and at the village of Overschie the travellers entered the Delfshaven Canal, which between perfectly straight dykes flows at a considerable height above the surrounding pastures. Then finally passing through one set of sluice gates after another, the Pilgrims were lifted from the canal into a broad receptacle for vessels, then into the outer haven, and so to the side of the SPEEDWELL as she lay at the quay awaiting their arrival.”

Dr. Holmes has prettily pictured the “Departure” in his “Robinson of Leyden,” even if not altogether correctly, geographically.

“He spake; with lingering, long embrace,

With tears of love and partings fond,

They floated down the creeping Maas,

Along the isle of Ysselmond.

“They passed the frowning towers of Briel,

The ‘Hook of Holland’s’ shelf of sand,

And grated soon with lifting keel

The sullen shores of Fatherland.

“No home for these! too well they knew

The mitred king behind the throne;

The sails were set, the pennons flew,

And westward ho! for worlds unknown.”