Lemerciergravure

Printed in Paris

Rudolph C. Slatin

Project Gutenberg's Fire and Sword in the Sudan, by Rudolf C. Slatin

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Fire and Sword in the Sudan

A Personal Narrative of Fighting and Serving the Dervishes 1879-1895

Author: Rudolf C. Slatin

Translator: F. R. Wingate

Release Date: October 12, 2012 [EBook #41035]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIRE AND SWORD IN THE SUDAN ***

Produced by Moti Ben-Ari and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

Prompted by the earnest entreaties of my friends rather than by any wish of my own to relate my experiences, I have written these chapters.

The few months which have elapsed since my escape have been so much occupied in resuming my official duties, compiling reports, and satisfying the kindly interest displayed by a large number of people in my strange fate, that any attempt at quiet and steady literary work has been almost impossible.

During my captivity I was unable to make any notes or keep any diaries; in writing, therefore, the following pages, I have been dependent entirely on my memory, whilst the whirl of the busy European world and the constant interruptions to which I have alluded, have given me little time to collect my scattered thoughts.

When, therefore, after having been debarred for so many years from intercourse with outside affairs, and entirely out of practice in writing down my ideas,[viii] I find myself urged to lose no time in publishing an account of my adventures, I must beg my readers to excuse the many defects they may notice.

My experiences have no pretence to being of any literary or scientific value, and the personal episodes I have described can lay claim to little importance; I have merely attempted to give to those interested in Sudan affairs a true and faithful account of my life whilst fighting and serving the Mahdists.

London, October, 1895.

The joy at meeting my dear friend and former comrade in captivity, Slatin Pasha, in Cairo, after his miraculous escape, was indeed great; and it is with extreme gratification that I comply with the wishes of those friends who are interested in his experiences, to preface them with a few remarks.

To have been a fellow-sufferer with him for many years, during which the closest friendship existed between us,—a friendship which, owing to the circumstances of our captivity, was necessarily of a surreptitious nature, but which, interrupted as it was, mutually helped to alleviate our sad lot,—is I think a sufficiently good reason for my friends to urge that I should comply with their wishes.

Apart, however, from these purely personal motives, I need only refer to the fact that the small scraps of information which from time to time reached the outside world regarding Slatin Pasha, excited the deepest sympathy for his sad fate; what wonder, then, that there should have been a genuine outburst of rejoicing when he at length escaped from[x] the clutches of the tyrannical Khalifa, and emerged safely from the dark Sudan?

It is most natural that all those interested in the weal and woe of Africa should await with deep interest all that Slatin Pasha can tell them of affairs in the former Egyptian Sudan, which only a few short years ago was considered the starting point for the civilisation of the Dark Continent, and which now, fallen, alas! under the despotic rule of a barbarous tyrant, forms the chief impediment to the civilising influences so vigorously at work in all other parts of Africa.

Slatin Pasha pleads with perfect justice that, deprived all these years of intellectual intercourse, he cannot do justice to the subject; nevertheless, I consider that it is his bounden duty to describe without delay his strange experiences, and I do not doubt that—whatever literary defects there may be in his work—the story of his life cannot fail to be both of interest and of value in helping those concerned in the future of this vast country to realise accurately its present situation.

It should be remembered that Slatin Pasha held high posts in the Sudan, he has travelled throughout the length and breadth of the country and—a perfect master of the language—he has had opportunities which few others have had to accurately describe affairs such as they were in the last days of the Egyptian Administration; whilst his experiences during his cruel captivity place him in a perfectly unique position as the highest authority on the rise, progress, and wane of that great religious movement which wrenched the country from its conquerors,[xi] and dragged it back into an almost indescribable condition of religious and moral decadence.

Thrown into contact with the principal leaders of the revolt, unwillingly forced to appear and live as one of them, he has been in the position of following in the closest manner every step taken by the Mahdi and his successor, the Khalifa, in the administration of their newly founded empire.

Sad fate, it is true, threw me also into the swirl of this great movement; but I was merely a captive missionary, whose very existence was almost forgotten by the rulers of the country, whilst Slatin Pasha was in the vortex itself of this mighty whirlpool which swamped one by one the Egyptian garrisons, and spread far and wide over the entire Sudan.

If, therefore, there should be any discrepancies between the account published some three years ago of my captivity and the present work, the reader may safely accept Slatin Pasha's conclusions as more correct and accurate than my own; the opinions I expressed of the Khalifa's motives and intentions, and of the principal events which occurred, are rather those of an outsider when compared to the intimate knowledge which Slatin Pasha was enabled to acquire, by reason of his position in continuous and close proximity to Abdullahi.

In concluding, therefore, these remarks, I will add an earnest hope that this book will arouse a deep and wide-spread interest in the fate of the unhappy Sudan, and will help those concerned to come to a right and just decision as to the steps which should be taken[xii] to restore to civilisation this once happy and prosperous country.

That the return of Slatin Pasha from, so to speak, a living grave should bring about this restoration, is the fervent prayer of his old comrade in captivity and devoted friend,

Suakin, June, 1895.

In preparing the edition in English of Slatin Pasha's experiences in the Sudan, I have followed the system adopted in Father Ohrwalder's "Ten Years' Captivity in the Mahdi's Camp."

London, October, 1895.

| Page | |

| Slatin Pasha | Frontispiece |

| Gessi Pasha's Troops advancing to the Attack on | |

| "Dem Suleiman" | To face 18 |

| Zubeir Pasha | " 48 |

| A Rizighat Warrior | " 52 |

| Bedayat praying to the Sacred Tree | " 114 |

| Surrender of the Bedayat to Slatin | " 116 |

| Fight between the Rizighat and Egyptian Troops | " 188 |

| A Dervish Emir | " 238 |

| The Death of Hicks Pasha | " 240 |

| Bringing Gordon's Head to Slatin | " 340 |

| An Abyssinian Scout | " 424 |

| A Slave Dhow on the Nile | " 430 |

| The Mahdi's Tomb, Omdurman | " 432 |

| The Execution of the "Batahin" | " 446 |

| Famine-stricken | " 454 |

| The Khalifa inciting his Troops to attack Kassala | " 504 |

| The Khalifa and Kadis in Council | " 528 |

| In the Slave Market, Omdurman | " 558 |

| Coming from Market, Omdurman | " 570 |

| Slatin Pasha's flying from Omdurman | " 592 |

| Slatin in hiding in the hills | " 598 |

| A Camel Corps Scout | " 616 |

| Plan of Khartum and Omdurman. | " 630 |

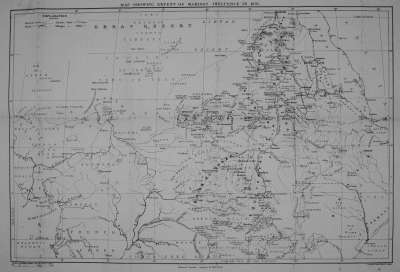

| Map showing Extent of Mahdist Influence in 1895. | " 630 |

My First Journey to the Sudan—Return to Austria—My Second Journey—Corruption in the Sudan—Appointed Governor of Dara—Gordon in Darfur—He suppresses the Slave-Trade—Zubeir Pasha and his Son Suleiman—The Gellabas, Jaalin, and Danagla—Retrospect of the First Causes of the Revolt in Bahr el Ghazal—Gessi's Campaigns—The Flight of Rabeh—Execution of Suleiman Zubeir—Effect of the Campaign on the Local Arabs.

In July, 1878, when serving as lieutenant in H. I. H. the Crown Prince Rudolph's regiment, the 19th Foot, on the Bosnian frontier, I received a letter from General Gordon, inviting me to come to the Sudan and take service with the Egyptian Government, under his direction.

I had previously, in 1874, undertaken a journey to the Sudan, travelling by Assuan, Korosko, and Berber, and had reached Khartum in the month of October of that year; thence I had visited the Nuba mountains, and had remained a short time at Delen, where a station of the Austrian Roman Catholic Mission had just been established. From here I explored the Golfan Naïma and Kadero mountains, and would have made a longer stay in these interesting districts, but the revolt of the Hawazma Arabs broke out, and, being merely a traveller, I received a summons to return forthwith to El Obeid, the chief town of Kordofan. The Arab revolt, which had arisen over the collection of the excessively high taxes imposed by the Government, was soon suppressed; but, under the[2] circumstances, I did not think it worth while returning to the Nuba districts, and therefore decided to travel in Darfur.

At that time the Governor-General of the Sudan, Ismail Pasha Ayub, was staying at El Fasher, the capital of Darfur; and on reaching Kaga and Katul, I found, to my great disappointment, that an order had just been issued prohibiting strangers from entering the country, as it had been only recently subjugated, and was considered unsafe for travellers. I returned therefore, without further delay, to Khartum; where I made the acquaintance of Emin Pasha (then Dr. Emin), who had arrived a few days previously from Egypt in company with a certain Karl von Grimm.

At that time General Gordon was Governor-General of the Equatorial Provinces, and was residing at Lado; so to him we wrote asking for instructions. Two months afterwards the reply came inviting us to visit Lado; but in the meantime letters had reached me from my family in Vienna urging me to return to Europe. I had been suffering considerably from fever, and besides I was under the obligation of completing my military service the following year. I therefore decided to comply with the wishes of my family.

Dr. Emin, however, accepted Gordon's invitation, and he started soon afterwards for the south, while I left for the north. Before parting, I begged Emin to recommend me to General Gordon, which he did; and this introduction eventually resulted in my receiving the letter to which I have already referred, three years later.

Emin, it will be remembered, was, soon after his arrival at Lado, granted the rank of Bey, and appointed Governor of Lado; and on Gordon's departure he was nominated Governor-General of Equatoria, in which position he remained until relieved by Mr. Stanley, in 1889.

I returned to Egypt by the Bayuda Desert, Dongola, and Wadi Haifa, and reached Austria towards the close of 1875.

[3]Gordon's letter, received in the midst of the Bosnian campaign, delighted me; I longed to return to the Sudan in some official capacity; but it was not till December, 1878, when the campaign was over and my battalion had gone into quarters at Pressburg, that I received permission, as an officer of the Reserve, to set out once more for Africa.

My brother Henry was still in Herzegovina; so, remaining only eight days in Vienna, to bid the rest of my family farewell, I left for Trieste on 21st December, 1878, little dreaming that nearly seventeen years would elapse, and that I should experience such strange and terrible adventures, before I should see my home again. I was then twenty-two years of age.

On arrival in Cairo, I received a telegram from Giegler Pasha, from Suez; he had just been appointed Inspector-General of Sudan Telegraphs, and was on his way to Massawa, to inspect the line between that place and Khartum; he invited me to travel with him as far as Suakin, and I gladly availed myself of his kind offer. We parted at Suakin, he proceeding by steamer to Massawa, while I made preparations to cross the desert to Berber on camels. I received every assistance from Ala ed Din Pasha, who was then Governor, and who subsequently, as Governor-General of the Sudan, accompanied Hicks Pasha, and was killed with him when the entire Egyptian force was annihilated at Shekan, in November, 1883.

On reaching Berber, I found a dahabia awaiting me there by General Gordon's orders, and, embarking immediately, I arrived at Khartum on 15th January, 1879. Here I was shown every kindness and consideration; Gordon placed at my disposal a house situated not far from the palace, and a certain Ali Effendi was directed to attend to all my wants. In the course of our daily meetings, General Gordon used often to talk of the Austrian officers whom he had met at Tultcha, when on the Danube Commission, and for whom he entertained a genuine friendship. I remember his saying to me that he thought[4] it was such a mistake to have changed our smart white jackets for the blue uniform we now wear.

Early in February, Gordon appointed me Financial Inspector, and I was instructed to travel about the country and examine into the complaints of the Sudanese who objected to the payment of the taxes, which were not considered unreasonably heavy. In compliance with these orders, I proceeded via Mesallamia to Sennar and Fazogl, whence I visited the mountain districts of Kukeli, Regreg, and Kashankero, in the neighbourhood of Beni Shangul; and then I submitted my report to General Gordon.

In this report I pointed out that, in my opinion, the distribution of taxes was unjust, and resulted in the bulk of taxation falling on the poorer landed proprietors, whilst those who were better off had no difficulty in bribing the tax-gatherers, for a comparatively small sum, to secure exemption. Thus enormous quantities of land and property entirely escaped taxation, whilst the poorer classes were mercilessly ground down, in order to make up the heavy deficit which was the result of this most nefarious system.

I further pointed out that much of the present discontent was due to the oppressive and tyrannical methods of the tax-gatherers, who were for the most part soldiers, Bashi-Bozuks, and Shaigias. These unscrupulous officials thought only of how to enrich themselves as quickly as possible at the expense of the unfortunate populations, over whom they exercised a cruel and brutal authority.

In the course of my journey, I frequently observed that the property of the Sudan officials—for the most part Shaigias and Turks—was almost invariably exempted from taxation; and, on inquiry, I was always told that this privilege had been procured, owing to the special services they had rendered the Government. When I remarked that they received pay for their services, they appeared greatly offended and annoyed. However, on my arresting some of the principal delinquents, they admitted that their taxes were justly due. In Mesallamia, which is a large[5] town situated between the Blue and White Niles, and a considerable trade centre, I found an immense collection of young women, the property of the wealthiest and most respected merchants, who had procured them and sold them for immoral purposes, at high prices. This was evidently a most lucrative trade; but how were the establishments of these merchants to be taxed, and what action was I to take? I confess that ideas and experience on this point quite failed me; and feeling my utter inability under these circumstances to effect any reform, and having at the same time little or no financial experience, I felt it was useless to continue, and therefore sent in my resignation. Meanwhile, Gordon had gone off to Darfur, with the object of inquiring into the circumstances connected with the campaign against Suleiman, the son of Zubeir Pasha; but before leaving he had promoted Giegler to the rank of Pasha, intrusting him with the position of acting Governor-General during his absence. I therefore took the occasion to send him my report and resignation by the same post, and soon afterwards received a telegram from Gordon, approving my resignation of the position of Financial Inspector.

It was an immense relief to me to be free from this hateful task; I had no qualms of conscience, for I felt my utter inability to cope with the situation, such as I found it,—radically wrong, and corrupt through and through.

A few days later, I received a telegram from Gordon, appointing me Mudir of Dara, comprising the southwestern districts of Darfur, and ordering me to start at once, as I was required to conduct military operations against Sultan Harun, the son of a former Sultan, and who was bent on endeavouring to wrest back his country from its Egyptian conquerors. Gordon further instructed me to meet him, on his return journey, somewhere between El Obeid and Tura el Hadra, on the White Nile. Having despatched my camels to this spot, where Gordon's steamer was waiting for him, I embarked without further delay, and on landing at Tura el Hadra, I proceeded west,[6] and after two hours' ride reached the telegraph station of Abu Garad, where I learnt that Gordon was only four or five hours distant, and was on his way to the Nile. I therefore started off again, and in a few hours found him halted under a large tree. He was evidently very tired and exhausted after his long ride, and was suffering from sores on his legs. I had fortunately brought some brandy with me from the stock on board his own steamer, and he was soon sufficiently revived to continue his journey. He asked me to come back with him to Tura el Hadra, to discuss the Darfur situation with him, and to give me the necessary instructions. He also introduced me to two members of his suite, Hassan Pasha Helmi el Juwaizer, formerly Governor-General of Kordofan and Darfur, and to Yusef Pasha esh Shellali, who was the last to join Gessi in his campaign against Suleiman Zubeir and the slave hunters. We were soon in the saddle; but Gordon shot far ahead of us, and we found it impossible to keep up with his rapid pace. We soon reached Tura el Hadra, where the baggage camels, which had previously been sent on ahead, had already arrived. As the steamers were anchored in mid-stream, we were rowed out in a boat. I found myself sitting in the stern, next Yusef Pasha esh Shellali, and, as a drinking-cup was near him and I was thirsty, I begged him to dip it into the river, and give me a drink. Gordon, noticing this, turned to me, smiling, and said, in French, "Are you not aware that Yusef Pasha, in spite of his black face, is very much your senior in rank? You are only the Mudir of Dara, and you should not have asked him to give you a drink." I at once apologised in Arabic to Yusef Pasha, adding that I had asked him for the water in a moment of forgetfulness; to which he replied that he was only too pleased to oblige me or any one else to whom he could be of service.

On reaching the steamers, Gordon and I went on board the "Ismaïlia," while Yusef Pasha and Hassan Pasha went on the "Bordein." Gordon explained to me in the fullest detail the state of Darfur, saying that he hoped most[7] sincerely the campaign against Sultan Harun would be brought to a successful close, for the country for years past had been the scene of continuous fighting and bloodshed, and was sorely in need of rest. He also told me that he believed Gessi's campaign against Suleiman Zubeir would soon be over; before long, he must be finally defeated or killed, for he had lost most of his Bazinger troops (rifle-bearing Blacks), and it was impossible for him to sustain the continual losses which Gessi had inflicted on him. It was past ten o'clock when he bade me "Good-bye." He had previously ordered the fires to be lighted, as he was starting that night for Khartum, and, as I stepped over the side, he said, in French, "Good-bye, my dear Slatin, and God bless you; I am sure you will do your best under any circumstances. Perhaps I am going back to England, and if so, I hope we may meet there." These were the last words I ever heard him utter; but who could have imagined the fate that was in store for both of us? I thanked him heartily for his great kindness and help, and on reaching the river-bank, I stopped there for an hour, waiting for the steamer to start. Then I heard the shrill whistle, and the anchor being weighed, and in a few minutes Gordon was out of sight—gone for ever!

On the following morning, mounted on the pony which Gordon had given me, and which carried me continuously for upwards of four years, I started off for Abu Garad, and, travelling thence by Abu Shoka and Khussi, reached El Obeid, where I found Dr. Zurbuchen, the Sanitary Inspector. He was about to start for Darfur, and we agreed to keep each other company as far as Dara. We hired baggage camels through the assistance of Ali Bey Sherif, the Governor of Kordofan; and just as we were about to set out, he handed me a telegram which had been sent from Foga, situated on the eastern frontier of Darfur; it was from Gessi, announcing that Suleiman Zubeir had fallen at Gara on 15th July, 1879: thus was Gordon's prediction verified that Suleiman must soon submit or fall.

It may not be out of place here to give a brief account[8] of this campaign; its principal features are probably well known, but it is possible I may be able to throw fresh light on some details which, though almost twenty years have now elapsed, still possess an interest, inasmuch as it was this campaign which was the means of bringing to the front a man whose strange exploits in the far west of Africa are now exercising the various European Powers who are pressing in from the west coast, towards the Lake Chad regions. I refer to Rabeh, or, as I find he is now called, Rabeh Zubeir.

After the conquest of Darfur, Zubeir, who had by this time been appointed Pasha, was instructed by the then Governor of the Sudan, Ismail Pasha, to reside in the Dara and Shakka districts. At this particular period relations between Ismail and Zubeir were strained; the latter had complained of the unnecessarily heavy taxation, and had begged the Khedive's permission to be allowed to come to Cairo to personally assure His Highness of his loyalty and devotion. Permission had been granted, and he had left for Cairo. Soon afterwards Ismail Pasha Ayub also left Darfur, and Hassan Pasha el Juwaizer succeeded him as Governor; while Suleiman, the son of Zubeir, was nominated as his father's representative, and was instructed to proceed to Shakka. Gordon, it will be remembered, had also succeeded Ismail Ayub as Governor-General, and had paid a visit of inspection to Darfur with the object of quieting the country, and introducing, by his presence and supervision, a more stable form of government.

On 7th June, 1878, Gordon arrived at Foga, and from there sent instructions to Suleiman Zubeir to meet him at Dara. Previous to this, information had reached him that Suleiman was not satisfied with his position, and was much disturbed by the news that his father was detained in Cairo by order of the Government.

It is said that Zubeir had sent letters to his son urging on him and his followers that, under any circumstances, they should be independent of the Egyptian Government; and as it was well known that Suleiman's object was to[9] maintain his father's authority in the country, his discontent was a factor which it was not possible to ignore.

From Foga, Gordon proceeded by Om Shanga to El Fasher, where he inspected the district and gave instructions for a fort to be built; and after a few days' stay there he came on to Dara, where Suleiman, with upwards of four thousand well-armed Bazingers, had already arrived, and was encamped in the open plain lying to the south of the fort. Conflicting opinions prevailed in Suleiman's camp in regard to the order that they were to move to Shakka. Most of his men had taken part in the conquest of Darfur, and consequently imagined that they had a sort of prescriptive right to the country, and they did not at all fancy handing over these fertile districts to the Turkish and Egyptian officials; moreover, Suleiman and his own immediate household were incensed against what they considered the unjust detention of Zubeir Pasha in Cairo, and it was evident they were doing all in their power to secure his return. It must also be borne in mind that most of Zubeir's chiefs were of his own tribe—the Jaalin—and had formerly been slave-hunters. By a combination of bravery and good luck they had succeeded in taking possession of immense tracts of land in the Bahr el Ghazal province, and here they had exercised an almost independent and arbitrary authority; nor was this a matter of surprise when the uncivilised condition of both the country and its inhabitants is taken into consideration. They had acquired their position by plundering and violence, and their authority was maintained by the same methods. When, therefore, they learnt that Gordon was coming, they discussed amongst themselves what line of action they should take. Some of the more turbulent members were for at once attacking Dara, which would have been a matter of no difficulty for them; others advised seizing Gordon and his escort, and then exchanging him for Zubeir: should he resist and be killed in consequence, then so much the better. A few, however, counselled submission and compliance with the orders of the Government.

[10]In the midst of all this discussion and difference of opinion, Gordon, travelling by Keriut and Shieria, had halted at a spot about four hours' march from Dara, and, having instructed his escort to follow him as usual, he and his secretaries, Tohami and Busati Bey, started in advance on camels. Hearing of his approach, Suleiman had given instructions to his troops to deploy in three lines between the camp and the fort; and while this operation was being carried out, Gordon, coming from the rear of the troops, passed rapidly through the lines, riding at a smart trot, and, saluting the troops right and left, reached the fort.

The suddenness of Gordon's arrival left the leaders no time to make their plans. They therefore ordered the general salute; but even before the thunder of the guns was heard, Gordon had already sent orders to Suleiman and his chiefs to appear instantly before him. The first to comply with this peremptory summons was Nur Angara; he was quickly followed by Said Hussein and Suleiman. The latter was not slow to perceive that the favourable moment had passed, and, therefore, at the head of a number of his leaders, presented himself before the ubiquitous Governor-General. After the usual compliments, Gordon ordered cigarettes and coffee to be handed round, and he then inquired after their affairs, and promised that he would do all in his power to satisfy every one; he then dismissed them, and told them to return to their men. But he motioned Suleiman to remain; and when alone, told him that he had heard there was some idea amongst his men of opposing the Government: he therefore urged him not to listen to evil counsellors. He gave him clearly to understand that it would be infinitely more to his advantage to comply with the orders of Government than to attempt offensive measures, which must eventually end in his ruin; and after some further conversation, in which Gordon to some extent excused the enormity of Suleiman's offence on account of his extreme youth, he forgave him, and allowed him to return to his troops, with the injunction that he should strictly obey all orders in the future.

[11]Meanwhile the escort which had been following behind from El Fasher arrived at the fort, and Gordon, after a short rest, sent for one of Suleiman's leaders, Said Hussein, with whom he discussed the situation. The latter declared that his chief, in spite of pardon, was even then ready to fight in order to secure his father's return and to get back his own power and authority. Gordon now appointed Said Hussein Governor of Shakka, and ordered him to start the following day with the troops he required; but he asked him to say nothing about his nomination for a few hours.

No sooner had he left Gordon than Nur Angara was summoned; and on being upbraided for the want of loyalty that evidently existed amongst the men, he replied that Suleiman was surrounded by bad advisers, who were driving him to his ruin, and that whenever he ventured to express a contrary opinion, Suleiman took not the smallest heed of what he might say. Gordon, convinced of his loyalty, appointed him Governor of Sirga and Arebu, in western Darfur, and instructed him to start the following day with Said Hussein and to take any men he liked with him.

When it came to Suleiman's ears that his two chiefs had been made governors by Gordon, he reproached them bitterly, and called to their minds how they owed all they possessed to his father's generosity; to this they replied that had it not been for their faithful services to his father, he would never have become so celebrated and successful. With these mutual recriminations the two new Governors quitted Suleiman, and started at daybreak the following morning for their destination.

When they had gone, Gordon again sent for Suleiman and his chiefs. He at first refused to come; but on the earnest entreaties of the others, who urged that further resistance to Gordon's orders was out of the question, he yielded with a bad grace, and once more found himself face to face with him. On this occasion Gordon treated him with the greatest consideration, pointing out that he had come expressly to advise Suleiman against the folly of[12] thinking that he could attempt to thwart the Government by trusting in the bravery and loyalty of his Bazingers; he assured him that loyal service under Government would bring him into a position which could not fail to satisfy his ambitions, and, that, further he had no reason to be concerned about his father's detention in Cairo, that he was treated with the greatest respect and honour there, and that he had only to exercise a little patience. Finally Gordon instructed him to proceed to Shakka with his men, and await his arrival there.

The following morning Suleiman received orders that on his arrival at Shakka the new Governor had been instructed to make all provision for the troops, and that therefore he should start without delay,—an order which he at once carried into effect. Thus had Gordon, by his amazing rapidity and quick grasp of the situation, arrived in two days at the settlement of a question which literally bristled with dangers and difficulties. Had Suleiman offered resistance at a time when Darfur was in a disturbed state, Gordon's position and the maintenance of Egyptian authority in these districts would have been precarious in the extreme.

Gordon then returned to El Fasher and Kebkebia; already the disturbances which had been so rife in the country showed signs of abatement, and by his personal influence he succeeded in still further quieting the districts and establishing a settled form of government. Leaving El Fasher in September, 1877, he again visited Dara and Shakka, where he found that Suleiman had quite accepted the situation and was prepared to act loyally; he therefore appointed him Governor of the Bahr el Ghazal province, which had been conquered by his father; he further gave him the rank of Bey, with which Suleiman appeared much gratified, and expressed great satisfaction at Gordon's confidence in him. A number of slaves, with their masters, who, when Suleiman was in disgrace at Dara, had deserted him, and had gone over to Said Hussein, now returned to him; and thus, with a considerable acquisition to his[13] strength, he left for Dem Zubeir, the chief town of his new province, which had been founded by his father.

Arrived here, he issued circulars to all parts of the country to the effect that he had been appointed Governor; and at the same time he sent a summons to a certain Idris Bey Ebtar to present himself forthwith before him. This Idris Bey Ebtar had, on Zubeir Pasha's departure for Cairo, been appointed by him as his agent in the Bahr el Ghazal. He was a native of Dongola, and in this fact lies, I think, the secret of the subsequent deplorable events.

The Bahr el Ghazal province is inhabited by an immense variety of negro tribes, who were more or less independent of each other until the Danagla and Jaalin Arabs, advancing from the Nile valley in their slave-hunting expeditions, gradually settled in the country and took possession of it. The Jaalin trace their descent back to Abbas, the uncle of the Prophet. They are very proud of it, and look down with the greatest contempt and scorn on the Danagla, whom they regard as descended from the slave Dangal. According to tradition, this man, although a slave, rose to be the ruler of Nubia, though he paid tribute to Bahnesa, the Coptic Bishop of the entire district lying between the present Sarras and Debba. This Dangal founded a town after his own name, Dangala (Dongola), and gradually the inhabitants of the district were known as Danagla. They are, for the most part, of Arab descent, but, having mixed freely with the natives of the country, have somewhat lost caste. Of course they too insist on their Arab descent, but the Jaalin continually refer to their Dangal origin, and treat them with contempt and derision. The relations between these two tribes must be fully recognised in order to understand what follows.

The friends of Idris Ebtar, who were for the most part Danagla, strongly urged him to disobey Suleiman's summons; and, in consequence, a situation arose which was entirely after the slave-hunter's own heart. To play off one chief against another, and thereby serve his own interest and derive personal benefit, is the Arab's delight; and[14] in this instance it was not long before Idris Ebtar's defiance of Suleiman's authority developed into terror of being taken prisoner, and he fled the country to Khartum. Arrived here, he reported that Suleiman was now acting as if the country were entirely his own; that instead of performing his duties as a governor, he had usurped the position of his father, who was rather a king than a governor; that he had given the best positions to his own Jaalin followers, to the exclusion of all the other tribes, more especially the Danagla, who were being tyrannized over and oppressed in every possible way,—indeed, according to Idris Ebtar's story, Suleiman was about to declare himself an independent ruler; and in support of his statement he produced quantities of petitions, purporting to have been received from merchants, slave-dealers, and others in the Bahr el Ghazal, all urging the Government to dismiss Suleiman at once, and replace him by another governor. Assisted by his numerous relatives, Idris Ebtar made such a good case of it to the Khartum authorities that they offered him the post of governor in succession to Suleiman, on condition that he would supply a regular annual revenue of ivory and india-rubber, and that he would also provide annually a contingent of Bazinger recruits, trained to the use of fire-arms, for incorporation in the Egyptian army.

In order to give full effect to his new appointment, he was given an escort of two hundred regular troops under a certain Awad es Sid Effendi, to whom instructions were given to comply absolutely with his orders.

Idris, leaving Khartum, proceeded by steamer up the White Nile, and thence by the Bahr el Ghazal to Meshra er Rek, eventually reaching Ganda, whence he wrote to Suleiman informing him that he had been dismissed. The receipt of this document was naturally the signal for a general commotion. Suleiman instantly summoned his relatives and friends to his side, and informed them in the most resolute manner that he would utterly refuse to comply with such an unfair order, pointing out with a certain amount of justice that since his arrival in Bahr el Ghazal[15] he had had practically no dealings with the Government, and that it was very unjust of them to act on mere suspicion, without giving him a chance of defending himself. He urged, moreover, that Government was not dealing fairly in discharging him from a position which was his by right. But here Suleiman was to a certain extent incorrect in claiming territory which, though conquered by his father, was now the actual property of the Government. The meeting over, he wrote a letter in the above sense to Idris Ebtar, protesting in the strongest terms against his interference, accusing him of base ingratitude, and of acting in defiance of every law of honour and justice in having recourse to such means to gratify his personal ambitions. He further reminded him of the assistance and support ever accorded to him by his absent father, Zubeir, who, on being obliged to leave Darfur, had appointed him his agent; and he finally upbraided him for having gone to Khartum as he did and intrigued to be made governor, instead of coming and seeing him as he had ordered, after Gordon had appointed him (Suleiman) governor; and he wound up his letter by an emphatic refusal to pay the smallest attention to Idris Bey's summons.

In answer to this letter, Idris sent Suleiman an ultimatum, calling on him to either submit instantly, or take the consequences of being proceeded against as a rebel; to which Suleiman replied that he was quite prepared to let the sword decide between them.

It was now clear that war must inevitably result, and the merchants began to be alarmed for their lives and property. The Jaalin, of course, wished Suleiman to remain their chief, whilst the other tribes, considerably in the minority, sided with Idris, who, on assuring himself that a resort to arms was inevitable, despatched his brother, Osman Ebtar, with two hundred regulars and a number of Bazingers under Awad es Sid Effendi, to garrison Ganda, whilst he himself, with a small party of Bazingers, proceeded to collect some followers, with a view to making a sudden onslaught[16] on Suleiman. The latter, however, incited by the intense hatred of his tribe for their Danagla enemies, did not hesitate to risk arbitration by the sword. Secretly collecting a number of his followers at Dem Zubeir, he made a sudden attack on the zariba at Ganda; and although Osman Ebtar and his men made a gallant stand, the zariba was soon reduced to ashes, the houses and huts, in accordance with Suleiman's orders, being completely destroyed, and the dead and wounded thrown into the flames. After this bloody encounter, all attempts at arriving at a peaceful settlement were out of the question; it was now war to the knife between Suleiman and Idris, and the latter, learning of the disaster at Ganda, lost no time in returning to Khartum and reporting that Suleiman had revolted in the Bahr el Ghazal, and had declared his independence, which was, in fact, the case. Indeed, no time was lost by Suleiman in informing the principal Bahr el Ghazal merchants, such as Genawi Abu Amuri, Zubeir Wad el Fahl, and others, that he had resolved to take up arms against the Government, and he begged them to co-operate with him. It was thus quite clear that Suleiman did not doubt the Government would not give up a province like Bahr el Ghazal without making a final effort to hold it. The Danagla also, knowing that they had no mercy to expect from the Jaalin, set to work to strengthen their own positions; but the principal merchants, such as Ali Amuri and Zubeir Wad el Fahl, who were very anxious to do nothing which would jeopardise their relations with the Government, stood aloof.

Meanwhile the news came that Romolo Gessi had reached Khartum, and had been appointed commander of the expedition against Suleiman and the slave-hunters. Accompanied by Yusef Pasha esh Shellali and forty officers and men, he proceeded in the first instance to Fashoda, where he secured the services of two companies of troops and further reinforcements of regulars and irregulars from Lado and Makaraka. At Gaba Shamba he found a considerable store of Remington rifles and ammunition[17] and a number of Bazingers, which raised his force to upwards of two thousand five hundred rifles.

It was now (July, 1878) the rainy season, and operations against Suleiman were for the moment impossible. Gessi, therefore, proceeded to Rumbek, and from thence sent a summons to Genawi and Wad el Fahl to join him. With this order they at once complied, bringing with them a further reinforcement of some two thousand five hundred men, while Gessi received continual additions to his strength from the smaller merchants and others, so that when the wet season was over he found himself at the head of upwards of seven thousand men, besides two guns and a number of rockets, with which he prepared to march to Ganda. Meanwhile, doubts being entertained of Said Hussein's loyalty, Gordon despatched Mustafa Bey Abu Kheiran to replace him; and on the arrival of the latter at Shakka, Said Hussein was sent to Khartum under escort. His arrest was the signal for all Zubeir Pasha's old chiefs, such as Osman Wad Tayalla, Musa Wad el Haj, and others, to join Suleiman, who had in the meantime been concentrating his troops, and had been joined by thousands of minor slave-hunters, mostly Rizighat and Habbania Arabs, who were ever ready to side with the winners, in the hope of plunder. Thus Suleiman's force was numerically far superior to that of Gessi Pasha, who by this time had reached Ganda.

Arrived here, he at once proceeded to construct a zariba and entrench himself. Yusef Pasha and the others who had no knowledge of fortification, laughed at Gessi's precautions; but it was not long before they were fully convinced of their efficacy. Suleiman advanced to attack Ganda, on 25th December, 1878; and after a terrific onslaught, in which both sides lost heavily, he was forced to retire. In spite of this heavy defeat, Suleiman, in the course of the next three months, made four other unsuccessful attacks on Ganda; and at length, in March, 1879, Gessi, having procured ammunition and reinforcements, prepared to take the offensive against Suleiman, who had[18] by this time suffered heavily, and had lost many of his best leaders.

On 1st May an action was fought, which was, comparatively speaking, insignificant in regard to losses, but resulted in Suleiman being forced to beat a precipitate retreat from Dem Zubeir; the large stock of slaves and booty falling into the hands of Gessi's Danagla followers, who, apparently without his knowledge, shared the plunder amongst themselves.

Suleiman's power was thoroughly broken, and he had now to decide between unconditional surrender to Government, or flight into the interior of Africa. The Danagla had become possessors of all his property, including his enormous harem of some eight hundred women, besides those of his various chiefs, whose respective households could not have numbered less than one hundred women each,—indeed, every Bazinger, who was practically a slave, was also the possessor of one or two wives; and now all this immense amount of human loot had fallen into the hands of his enemies. Moreover, his scattered forces, which were now roaming about the country in search of work, made no secret of the quantities of gold and silver treasure which Suleiman had amassed, and which were now, no doubt, in the hands of Gessi's men. When it is remembered that Suleiman's treasury included the masses of gold and silver jewellery captured by his father at Dara, at Manawashi,—where Sultan Ibrahim had ruled, and had fallen on the capture of Darfur,—at El Fasher, at Kebkebia, etc., it can be readily understood what riches must have fallen into the hands of the Government levies, and—perhaps unknown to their commander, who was ignorant of the language—had been divided up amongst them.

Gessi now quartered the bulk of his troops in the entrenched camp vacated by Suleiman, and with a comparatively small force proceeded to follow him up in pursuit. In order to conceal his whereabouts, Suleiman had scattered his men throughout the western districts; but Gessi came across one of his armed bands, under Rabeh, and dispersed it without much difficulty.[19] Rabeh, however, escaped, and just at this period Gessi received orders from Gordon to meet him in Darfur; he therefore collected all his troops in Dem Suleiman, where they rested after their fatiguing campaign, whilst he himself, accompanied by some of his officers, amongst whom was Yusef Pasha esh Shellali, proceeded to Et Toweisha, where the caravan routes from Om Shanga, El Obeid, and Dara join, and here he met Gordon.

In this his second visit to Darfur, Gordon had ascertained that the Sudanese merchants of El Obeid had been selling arms and powder to the rebel Suleiman, with whom they naturally sympathised for their own selfish purposes; this contraband of war had been secretly despatched to Bahr el Ghazal through the intermediary of the Gellabas (petty traders), who obtained enormous prices from Suleiman: for instance, six to eight slaves would be exchanged for a double-barrelled gun, and one or two slaves was the price of a box of caps. The officials at El Obeid made some attempt to check this trade, but the difficulties were great. The districts between Kordofan and Bahr el Ghazal were inhabited principally by nomad Arab tribes such as the Rizighat, Hawazma, Homr, and Messeiria; it was, moreover, an easy matter for small parties of Gellabas to traverse, without fear of detection, the almost uninhabited forests, with which the country abounds; and even if an Egyptian official came across them, he was, as a rule, quite amenable to a small bribe.

Gordon was fully cognisant of all this, and therefore gave the order that trade of every description was to be stopped between El Obeid and Bahr el Ghazal. The merchants were, in consequence, ordered to quit all districts lying to the south of the El Obeid, Et Toweisha, and Dara caravan road, and to confine their trade entirely to the northern and western countries, whilst active operations were going on in Bahr el Ghazal. But, in spite of the strictness with which these orders were enforced, the chances of gain were so enormous and so enticing that the merchants grew almost insensible to the risk of discovery; and, in fact, the[20] Government had not at hand the means of checking the trade in an adequate manner,—indeed, in spite of the Government restrictions, the trade rather increased than decreased. Gordon, therefore, had to resort to very drastic measures. He ordered the Sheikhs of the Arab tribes to seize all Gellabas in their districts, and forcibly drive them to Dara, Toweisha, Om Shanga, and El Obeid, and at the same time held them responsible for any Gellabas found in their countries, after a certain date. This order was welcomed by the greedy Arabs, who seized the occasion to pillage, not only the wandering traders, but even those who had been settled amongst them for years, and who had nothing to do with this illicit commerce; they gathered the wheat and the tares together, and cast out both indiscriminately, making considerable profit over the transaction. Gordon's order was now the signal for a wholesale campaign against the traders, who not only lost their goods, but almost every stitch of clothing they possessed, and were driven like wild animals in hundreds, almost naked, towards Dara, Toweisha, and Om Shanga. It was a terrible punishment for their unlawful communication with the enemies of the Government.

Many of these traders had been residing amongst the Arabs for years. They had got wives, children, concubines, and considerable quantities of property, which in turn fell into the hands of the Arabs. The fates, indeed, wreaked all their fury on these wretched slave-hunters, and the retribution—merited as it undoubtedly was, on the principle of an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth—was painful enough to witness, and had consequences which were more far-reaching; for it must be remembered that the majority of these petty traders were Jaalin from the Nile valley, and between them and their Arab oppressors there now arose the most implacable hatred, which has continued up to the present time, and which shows signs of increase rather than of diminution.

In point of humanity, this attack on the Gellabas may be open to question; but on closer investigation it will be[21] apparent to all that it was not possible to deal with an anomalous situation, such as then existed, by political or philanthropic methods,—drastic and violent measures could alone be effective. The Arab himself says, "Nar el ghaba yelzamha el harika" (Against a prairie-fire, fire must be used); and the proverb was peculiarly applicable in this case.

Now, these traders being for the most part Jaalin, Shaigias and Danagla had, of course, relations and friends in the Nile valley; and, indeed, many of the latter were their intermediaries in the commercial and slave transactions which took place. Gordon's orders, therefore, were scarcely less unpopular amongst these Nile-dwellers, who could not understand why such severe measures were necessary, merely to prevent Gessi from being defeated in Bahr el Ghazal.

But to return to Gessi's movements. Having met Gordon at Toweisha, and explained the situation to him, he was instructed to proceed to Dara, while Gordon returned to Khartum, and with him Yusef Pasha Shellali, who during the entire campaign had served Gessi most loyally, but who had been told, by some of the numerous intriguers, that his chief was against him; he therefore begged Gordon to allow him to return with him to Khartum,—a request which was at once granted, while his services were further recognised by his promotion to the rank of Pasha.

On his arrival at Dara, Gessi received information that Suleiman had quitted Bahr el Ghazal, and, having collected his forces, was somewhere in the southwest of Darfur. It was thought that he intended to unite with Sultan ben Seif ed Din, a direct descendant of the old Darfur kings, who was said to have collected a force with the object of opposing the Government and driving out the foreigners. It is impossible to say whether this was really Suleiman's intention; but there is no doubt that Sultan Harun had never concluded an alliance with Suleiman, who, being the son of the conqueror of Darfur, by whom the dynasty had been destroyed, was hated by the Darfur people even more than[22] were the Egyptians; the latter, in comparison with Zubeir's lawless gangs of Bazingers, had a slightly higher reputation, but both seemed to consider the Darfurians their legitimate prey, and both were guilty of acts of cruelty and oppression.

At this time the principal Government official at Dara was Zogal Bey (Mohammed Bey Khaled); and Gessi, having left almost all his troops in Bahr el Ghazal, now begged him to place at his disposal two companies of regular troops, under the command of Saghkolaghasi Mansur Effendi Helmi; with these, and a certain Ismail Wad el Barnu,—an Egyptian born in Darfur, and well known for his bravery, and knowledge of the country,—Gessi set off for Kalaka, the headquarters of the Habbania Arabs. Here he was joined by Arifi Wad Ahmed, head Sheikh of the Habbania, and by Madibbo Bey, chief of the Rizighat, who was loyal to Government, and could place several hundred horsemen in the field.

Suleiman's star was now declining. Abandoned by most of his own tribesmen, who had secretly made off through the forests to the Nile valley; deserted by the greater part of his trusted Bazingers, whom hunger, fatigue, and aimless wandering in pathless regions had hopelessly scattered; his footsteps dogged by Gessi, who was kept informed of his every movement,—he was, indeed, in sorry plight when Ismail Wad Barnu, despatched by Gessi with a summons to surrender, appeared before him at Gharra.

Ismail was well known to Suleiman, and had been instructed by Gessi to inform him that, should he submit, his life and the lives of his chiefs would be spared, and his women and children should not be touched, on condition that he handed over to him his Bazingers, with their arms, and made a solemn vow of loyalty to the Egyptian Government. Ismail pointed out to Suleiman that all hope of successful resistance was now at an end, and, as a native of the country, he gave it as his private opinion that Sultan Harun would never be induced to enter into alliance with him.

[23]Suleiman now convened a meeting of his principal men to discuss the terms of peace offered by Gessi. Most of them were heartily tired of this constant fighting, in which they had been almost invariably defeated, but there were some who doubted the sincerity of the conditions proposed; Ismail, however, asserted in the strongest terms that he would guarantee the sincerity of Gessi, who himself longed to put an end to this useless bloodshed, and further stated that he had been authorised by him to take a solemn oath in his name that the conditions of surrender would be faithfully observed.

Suleiman and all his chiefs, with the exception of Rabeh, agreed to accept; but the latter pointed out, with a prescience, which subsequent events justified, that Suleiman had been warned, before he took up arms, of the danger he was incurring, and that once in the hands of his captors he could not hope for mercy. As regards himself, Rabeh declared that it would be pain and grief to him to separate from men who had been his companions in joy and sorrow all these years, but he gave them distinctly to understand that he would never place himself in the power of Gessi, whose success had been due to the Danagla, and who, though an European, was really in their hands. He begged his companions to remember the bitter animosity which existed between the Jaalin and Danagla, and recalled the merciless manner in which the former had treated the latter when Osman Ebtar had been defeated at Ganda. He therefore had two proposals to make, viz., to collect their entire force and march west into the Banda countries, which had hitherto been untouched by foreign intruders, and which could offer no resistance to the thousands of well-armed Bazingers they still had at their command. He then went on to say, that once the Black tribes had been subjugated, they could enter into relations with the kingdoms of Wadai, Baghirmi, and Bornu, and that it was most unlikely that Gessi and his men, who were tired of fighting, would follow them into distant and unknown regions, over which the Government had no control, and from which it was not likely they could reap any benefit.

[24]Should this proposal not meet with their approbation, then he would suggest that as they wished now to lead quiet lives with their fellow-tribesmen in the Nile valley, they should send a special deputation either to His Highness the Khedive or to Gordon Pasha, begging for pardon and peace; but that they should never do so through Gessi, whose only object was to secure their arms and Bazingers, and who, at the capture of Dem Suleiman, had unhesitatingly taken everything they possessed. If, therefore, they wished to save their lives and avoid the intrigues of the Danagla, all they had to do was to leave the Bazingers with their arms behind, and themselves proceed by Kalaka and Shakka and through the uninhabited forests of Dar Hamar to Foga, the western telegraph station on the Darfur frontier, whence they could wire their submission and ask for pardon, which would undoubtedly be granted. Or they might, added Rabeh, proceed from Shakka through Dar Homr, and, skirting the northern Janghé country, reach El Obeid, where they could make their submission through the intermediary of the Governor and their relative, Elias Pasha Wad Um Bereir. He concluded his speech by saying that should none of these proposals meet with approval, then he was prepared, with the greatest reluctance, to quit his lifelong friends, and, taking those who wished to join him, he would march west and take his chance; but, he added most emphatically, he would never place himself in the hands of Gessi and his Danagla.

These proposals were made by Rabeh to Suleiman and the others in the presence of Ismail Wad Barnu, who again urged that they should submit to Gessi, arguing that as the latter had been originally entrusted with the campaign, it would naturally be a point of honour with him to see to Suleiman's safety and to write favourably to Government in regard to him; but, on the other hand, added Ismail, should Suleiman attempt to obtain pardon without Gessi's intermediary, then the latter would naturally be very angry, and would probably be the means of injuring him in the eyes of the Government.

[25]Musa Wad el Haj, one of Suleiman's best leaders, and who also had some influence with Gessi, now addressed Rabeh as follows: "You have made certain proposals in the hearing of Ismail Wad Barnu, who is Gessi's messenger. Should we concur with your proposals, what do you consider we should do with him?" To this question Rabeh answered, "Ismail is our friend, and was trusted by Zubeir; far be it from me to wish him any harm. Should we decide on flight, then, in self-preservation, we must take him with us a certain distance and when we are out of reach of pursuit, let him go." A long discussion now ensued, which resulted in a division of opinions: Suleiman, Hassan Wad Degeil (Zubeir's uncle), Musa Wad el Haj, Ibrahim Wad Hussein (the brother of Saleh Wad Hussein, the former Governor of Shakka, who had been arrested and sent to Khartum), Suleiman Wad Mohammed, Ahmed Wad Idris, Abdel Kader Wad el Imam, and Babakr Wad Mansur, all of the Gemiab section of the Jaalin tribe; also Arbab Mohammed Wad Diab of the Saadab section, agreed to accept Gessi's conditions and submit. But Rabeh, Abu el Kasim (of the Magazib section), Musa Wad el Jaali, Idris Wad es Sultan, and Mohammed Wad Fadlalla, of the Gemiab section, and Abdel Bayin, a former slave of Zubeir Pasha, decided not to submit under any circumstances, but to march west. Ismail, being of course most anxious to inform Gessi of Suleiman's submission, urged him to break up the meeting and to give him a written document that the conditions were acceptable. Suleiman complied, and with eight of his chiefs signed the compact and handed it to Ismail, who at once returned to Gessi at Kalaka with presents of several male and female slaves.

No sooner had he gone than Rabeh again came to Suleiman, and in the most earnest terms begged him to reconsider the matter; but Suleiman was obdurate, and Rabeh, therefore, retired heart-broken, beat his war-drums to collect his Bazingers and followers, sorrowfully bade his old companions farewell, and marched off in a southwesterly[26] direction, to the sound of the ombeÿa, or elephant's tusk (the Sudan war-horn, which can be heard at an immense distance).

Several of Suleiman's men, seeing that Rabeh was determined not to submit, joined him, preferring the uncertainty of a life of adventure in the pathless forests to the risk of giving themselves up to the hated Danagla. But the five chiefs who had been his main supporters took the occasion to desert him at his first camping-station, intending to conceal themselves by the help of the Arab chiefs whom they knew, and eventually to make their way back to the Nile when all danger was over.

On receipt of Suleiman's letter of submission, Gessi set out with all speed for Gharra, accompanied by Ismail, who feared that Rabeh's counsels might after all prevail and that they had no time to lose; they took with them a considerable number of men, and were reinforced by contingents supplied by the Rizighat and Habbania chiefs. Arrived near Gharra, Gessi sent on Ismail to tell Suleiman that he had received the signed conditions, with which he was satisfied, and that he had come to personally accept his submission. In a short time Ismail returned, reporting Rabeh's flight with a considerable number of Bazingers and arms, and that Suleiman was quite prepared to surrender. Gessi therefore advanced to Gharra with his troops and met Suleiman, whose men had piled their arms. He verbally gave them the pardon for which they asked, and then ordered the Bazingers to be distributed between Sheikh Arifi and Madibbo Bey, while instructions were given to put the chiefs under a guard until the Government officials appointed to take charge of them should have been selected.

These orders were executed with great promptitude, and in two hours, out of the entire camp, only Suleiman and the chiefs, with their wives and families, remained, and over these a small guard was placed.

Now, as Rabeh had truly foretold, the intrigues of the Danagla against Suleiman began. They told Gessi that[27] Suleiman's servants had reported that he already regretted having submitted, and that had he known that he was to be received in such a way, he would rather have died fighting. Gessi, although a man of an open and honourable disposition, was somewhat susceptible to such insinuations; he trusted his own men, and as they had risked their lives for him, he did not doubt their words. But he neither knew nor realised that his men were bent on Suleiman's destruction. The loot which they had taken in Dem Suleiman and in many other engagements was enormous, besides male and female slaves, gold and silver jewellery, and an immense amount of cash, all of which they had distributed amongst themselves, unknown to Gessi. What they now feared was that Suleiman, being admitted to Gessi's favour, would inform him of what had occurred, and that he would enter a claim against the Government. Moreover, it will be remembered how Idris Ebtar had by his intrigues given the authorities the impression that the Bahr el Ghazal revolt was entirely due to the Zubeir faction, while they showed themselves in the light of faithful adherents and martyrs to the Government cause. They dreaded lest Suleiman might be sent to Khartum, whence he would probably obtain permission to visit his father in Cairo, and they knew that Zubeir possessed sufficient influence to institute claims against them for the seizure of his property, and would moreover do his utmost to show that Suleiman was not responsible for the revolt.

The Danagla, therefore, now resorted to the following base expedient: they informed Gessi that Suleiman had sent messengers to recall Rabeh, that he had given him instructions to make an attack on Gessi, who had only an insignificant force, and to whom they had surrendered under the impression that his force was much larger, but that Rabeh was sufficiently strong to easily overcome him, and thus completely turn the tables.

Mansur Effendi Helmi also came forward and corroborated these tales, adding that he was convinced Suleiman was just as hostile as before, and that on the smallest[28] chance being given him he would not hesitate to revolt once more against the Government.

Gessi was now fully convinced that their statements were true, and in consequence of their urgent declamations against Suleiman he went back on the promise he had made that their lives should be safe. In the course of the day he had Suleiman and the nine chiefs brought into his tent, and reproached them very severely for their traitorous conduct. To proud and uncivilised men these reproaches were unbearable, and they replied in an equally abrupt tone. Gessi, stung to anger, quitted the tent and ordered the Danagla, who were lurking about, to shoot them. In a moment the tent was pulled down over their heads, they were secured, their hands were tied behind their backs, and they were driven to the place of execution. With the most bitter imprecations on their lips against the treacherous Danagla, they fell, shot through the back by the rifles of a firing party of Mansur Helmi's regulars, on the 15th July, 1879. Thus did fate overtake Suleiman and his friends. Death had come upon them treacherously, it is true; but they had abused the authority with which they had been vested, by their cruelty and ambition they had wrecked the provinces of Bahr el Ghazal and Darfur, and had reduced the inhabitants to an unparalleled state of misery and wretchedness.

Gessi lost no time in sending a telegram to the station at Foga reporting Suleiman's death and the conclusion of the campaign to Gordon. This news, as already related, reached me through Ali Bey Sherif the day I left El Obeid for Darfur.

Gessi now called on the Shaigias to hand over the Bazingers in their charge; but they reported that owing to an insufficient guard they had escaped; and as the story seemed credible, Gessi collected the remainder of his men, with the intention of proceeding to Bahr el Ghazal, where he wished to establish a settled form of government, in place of the constant warfare which had decimated this fertile province. Just before leaving, he received information[29] that the five chiefs who had left Rabeh, viz., Abdel Kasim, Musa Jaali, Idris Wad es Sultan, Mohammed Fadlalla, and Abdel Bayin; were in hiding amongst the Arabs; he therefore left orders for the Shaigia to search for them, and when found, to bring them for punishment before the Governor of El Fasher. Zogal Bey, the Governor of Shakka, was also ordered to do his utmost to catch these men, with the result that they were discovered without much difficulty, and brought, with shebas round their necks, to El Fasher, where Messedaglia Bey, without further ado, had them instantly shot. Thus, with the exception of Rabeh, the entire Zubeir gang was destroyed, and the power of the slave-hunters crippled.

The campaign had resulted in a considerable loss to Government of arms and ammunition, and in a corresponding acquisition of strength to the great southern Arab tribes, such as the Baggara, Taisha, Habbania, and Rizighat, who both before and after the fall of Suleiman had captured numbers of Bazingers and immense quantities of loot; the subsequent effects of which were not long in showing themselves.

Arrival at Om Shanga—Matrimonial Difficulties—A Sudanese Falstaff—Description of El Fasher—The Furs and the Tago—A Tale of Love and Perfidy—Founding of the Tungur Dynasty—Conquest of Darfur by Zubeir Pasha—The Rizighat Tribe—Quarrel between Zubeir Pasha and the Governor-General—Both recalled to Cairo—Gordon Governor-General of the Sudan—I take up my Duties at Dara—Zogal Bey the Sub-Governor—I undertake a Campaign against Sultan Harun—Niurnia, Harun's Stronghold in Jebel Mara—I defeat the Sultan at Rahad en Nabak—Death of Harun—My Meeting with Dr. Felkin and the Rev. Wilson—My Boy Kapsun—Gordon's Letter from Abyssinia.

I left El Obeid early in July, 1879, in company with Dr. Zurbuchen, the Sanitary Inspector-General, whom I had met in Cairo; our route took us through Foga, the telegraph terminus, and here I found a telegram from Gordon, telling me that he was proceeding on a Mission to King John of Abyssinia.

We reached Om Shanga to find it crowded with Gellabas who had been turned out of the southern districts, and were really in a pitiable condition. Curiously enough, the news had spread far and wide that I was Gordon's nephew (I suppose on account of my blue eyes and shaven chin), and in consequence I was looked upon with some apprehension by these people, who considered him as the cause of all the troubles which they were now justly suffering. I was overwhelmed with petitions for support; but I told them that as Om Shanga was not in my district, I could do nothing for them,—and even if I could have spared them something from my private purse, I had neither the desire nor inclination to do so.

[31]In one case, however, I confess to having broken the rule; but before relating this little episode, I should explain that my action must not be judged from the standpoint of purely Christian morality. In this case I admit to being guilty of even greater moral laxity in regard to the Moslem marriage law, than is enjoined in the Sharia, or religious law; but when my readers have finished the story, I think they will perhaps share the feelings which prompted me to act as I did. Several of the merchants who had travelled from the Nile called upon me and begged me to interest myself in the case of an unfortunate youth, a native of Khartum and only nineteen years of age. They related that before quitting Khartum he had been betrothed to his beautiful but very poor young cousin; the parents had consented to the marriage, but he was to first take a journey and try to make some money. On his arrival at Om Shanga a very rich old woman took a violent fancy to him. Whether the youth had been overcome by her riches, my informants did not say, but the old woman would have her way and had married him; and now, finding himself comparatively wealthy, he had no particular desire to give her up. The sad news had reached Khartum, the poor girl was distracted, and now I was asked to solve the difficulty. What was I to do? I called up the youth, who was unusually good-looking, and, taking him aside, I spoke to him with as serious a countenance as I could preserve; I pointed out how very wrong it was of him, a foreigner, to have married a strange old woman while his poor fiancée was crying her eyes out at home, and that even if his cousin's dowry was small, still, in honour bound, he should keep his promise. He hesitated for a long time, but at length decided to go before the Kadi (judge of the religious law) and get a divorce. I had previously seen the Kadi, and had instructed him that should the youth seek a divorce, it was his duty to break the news as gently as he could to the old wife, as I was most anxious the separation should be carried out with as little commotion as possible; and, taking a guarantee from the young[32] man's relatives that they would be responsible that he should go direct to Khartum, I warned the Government official of Om Shanga that the youth was to be banished at two days' notice! I also told him that he might say what he liked about me to the old woman, and that I was quite ready to bear the blame, provided he could get her to give him some money for the journey. Little did I imagine what a storm I had brought on my devoted head! It was about four o'clock in the afternoon, and I was lying on my angareb (native couch) in the little brick hut, when I heard the voice of an angry woman demanding to see me instantly. I guessed at once who it was, and, bracing my nerves for the fray, told the orderly to let her in. Dr. Zurbuchen, who was in the room with me, and whose knowledge of Arabic was very limited, was most desirous to leave me; but I was by no means anxious to be left alone with an angry woman, and at length persuaded him to stay. No sooner was the divorced wife admitted than she rushed up angrily to Dr. Zurbuchen, whom she mistook for me, and shrieked in a tone of frantic excitement, "I shall never agree to a divorce. He is my husband, and I am his wife; he married me in accordance with the religious law, and I refuse to let him divorce me." Dr. Zurbuchen, thoroughly startled, muttered in broken Arabic that he had nothing to do with the case, and meekly pointed to me as the hard-hearted Governor. I could not help being amused at the extraordinary figure before me. She was a great strong woman, with evidently a will of her own; and so furious was she that she had quite disregarded all the rules which usually apply when Eastern ladies address the opposite sex. Her long white muslin veil had got twisted round and round her dress, exposing her particoloured silk headdress, which had fallen on her shoulders; she had a yellowish complexion, and her face was covered with wrinkles, while her cheeks were marked by the three tribal slits, about half an inch apart; in her nose she wore a piece of red coral, massive gold earrings in her ears, and her greasy hair was twisted into innumerable[33] little ringlets, which were growing gray with advancing age. I thought I had never seen a more appalling looking old creature; but my contemplations were cut short by her screeching voice, which was now directed on me with renewed fury, and I was confronted with the same question she had addressed to the terrified doctor. Giving her time to recover her breath, I replied, "I quite understand what you say, but you must submit to the inevitable: your husband must leave; and as you are a native, I cannot permit you to go with him. You appear undesirous of having a divorce; but you must remember that, in accordance with the Moslem law, it is for the man to give the woman her divorce papers, and not the woman the man."

"Had you not interfered," she shrieked, "he would never have left me. Cursed be the day you came here!"

"I beg of you, do not say that," I answered; "you are a woman of means, and I should not think you would have any difficulty in securing another and perhaps older husband."

"I want no other," she literally screamed.

"Silence!" I said somewhat sharply. "The relatives of your former husband wish him to leave you; they complained that it was only your money which bound him to you; and now, whatever you may say, he is to leave to-morrow. Besides, do you not think it is outrageous that an old woman like you should have married a young lad who might have been your grandson?" These last words drove her into a state of perfect frenzy; and, losing all control over herself, she threw up her hands, tore off her veil, and what else might have happened I know not, but my kavass (orderly), hearing the noise, rushed in and quietly but forcibly removed her from the room, cautioning her that her conduct was disgraceful, and that she had made a laughing-stock of herself. The following day her husband left, and I do not doubt her grief was considerable; but some years later I had the satisfaction of meeting the youth, married to his early fiancée, and already the father of a family; he thanked me profusely for having got him[34] out of the clutches of the old woman and brought him to his present happy state. It is needless to relate that I slept soundly that night, convinced that I had done a good piece of work, and that it had cost me nothing.

Two days later we left Om Shanga, and halted for the night at Jebel el Hella, where we were met by Hassan Bey Om Kadok, the Sheikh of the northern Berti tribes, who had shown great loyalty and had been granted by Gordon the rank of Bey. He was a middle-aged man, very stout, with great broad shoulders and a round, smiling face; he might well have been called the Sudan "Falstaff." Some years later, when the tables were turned, and masters became servants, he and I found ourselves together as orderlies in the Khalifa's body-guard, where his cheerful disposition and genial nature brightened an existence which at times was almost unbearable. His brother Ismail was exactly the opposite,—tall, thin, and serious; and the two brothers never by any chance agreed, except on one point, and that was their inveterate love of marissa (Sudan beer): to have each a large jar (made of pottery, and known in Darfur as the Dulang asslia or Um bilbil) of this marissa, and to vie with one another in emptying it first, was to them the greatest pleasure in life.

They invited us to sup with them, and for our evening meal an entire sheep, baked on charcoal, was served up, besides a quantity of roast fowls and a dish of asida (the latter is somewhat like the Italian polenta, and is eaten with all the courses); there were also several jars of marissa. We thoroughly enjoyed the food, leaving the marissa to our hosts, and substituting for it some of our own red wine. Hassan and Ismail, however, freely regaled themselves with wine as well as marissa; the effect on the former being to make him extremely talkative, while the latter became more and more silent. Hassan related many little incidents about Gordon, for whom he had the greatest admiration and regard. He was much grieved to hear he was going to Abyssinia. "Perhaps," said he, sadly, "he will go back to his own country, and never return to the[35] Sudan again." Curiously enough, he was partially correct. He then left the room and returned almost at once, carrying a magnificent saddle and sword. "Look," said he, "these are the last presents General Gordon gave me when I accompanied him to El Fasher; he was most kind and generous." Then Ismail showed us a rich gold embroidered robe which Gordon had presented to him. "Pride," said Hassan, "was unknown to Gordon. One day, on our way to El Fasher, one of the attendants shot a bustard; and when we halted at noon, the cook at once boiled some water and threw the bird into the pot, so as to take off its feathers. Gordon, seeing this, went and sat himself down by the cook and began helping him to pull out the feathers. I at once rushed up and begged him to allow me to do this for him, but he answered, 'Why should I be ashamed of doing work? I am quite able to wait on myself, and certainly do not require a Bey to do my kitchen work for me.'"

Hassan continued chatting till a late hour. He related his experiences during Zubeir's conquest of Darfur, then of the subsequent revolts and the present situation, frequently reverting to Gordon, whom he held in great honour. "Once, travelling with Gordon," he remarked, "I fell ill, and Gordon came to see me in my tent. In the course of our conversation I told him that I was addicted to alcoholic drinks, and that I put down my present indisposition to being obliged to do without them for the last few days. This was really my indirect way of asking Gordon to give me something; but I was mightily disappointed, and, instead, received a very severe rebuke. 'You a Moslem,' said he, 'and forbidden by your religion to drink wines and spirits! I am indeed surprised. You should give up this habit altogether; every one should follow the precepts of his religion.' I replied, 'Having been accustomed to them all my life, if I now gave them up my health must suffer; but I will try and be more moderate in future.' Gordon seemed satisfied, got up, shook hands with me, and bade me good-bye. The following[36] morning, before leaving, he sent me three bottles of brandy, with injunctions that I should use them in moderation."