| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://archive.org/details/cu31924028287724 |

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

IN THE

"Story of the Nations" Series.

Each volume large crown 8vo, cloth, fully Illustrated, 5s.

MODERN ENGLAND BEFORE THE REFORM BILL.

MODERN ENGLAND UNDER QUEEN VICTORIA.

IN PREPARATION.

PORTRAITS OF THE SIXTIES.

Demy 8vo, cloth, Illustrated, 16s.

LONDON: T. FISHER UNWIN.

| 1. | ARTHUR JAMES BALFOUR | 1 |

| 2. | LORD SALISBURY | 25 |

| 3. | LORD ROSEBERY | 49 |

| 4. | JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN | 73 |

| 5. | HENRY LABOUCHERE | 99 |

| 6. | JOHN MORLEY | 125 |

| 7. | LORD ABERDEEN | 151 |

| 8. | JOHN BURNS | 177 |

| 9. | SIR MICHAEL HICKS-BEACH | 203 |

| 10. | JOHN E. REDMOND | 229 |

| 11. | SIR WILLIAM HARCOURT | 255 |

| 12. | JAMES BRYCE | 281 |

| 13. | SIR HENRY CAMPBELL-BANNERMAN | 307 |

My first acquaintance with Mr. Arthur J. Balfour, who recently became Prime Minister of King Edward VII., was made in the earliest days of my experience as a member of the House of Commons. The Fourth party, as it was called, had just been formed under the inspiration of the late Lord Randolph Churchill. The Fourth party was a new political enterprise. The House of Commons up to that time contained three regular and recognized political parties—the supporters of the Government, the supporters of the Opposition, and the members of the Irish Nationalist party, of whom I was one. Lord Randolph Churchill created a Fourth party, the business of which was to act independently alike of the Government, the Opposition, and the Irish Nationalists. At the time when I entered Parliament the Conservatives were in power, and Conservative statesmen occupied the Treasury Bench. The members of Lord Randolph's party were[2] all Conservatives so far as general political principles were concerned, but Lord Randolph's idea was to lead a number of followers who should be prepared and ready to speak and vote against any Government proposal which they believed to be too conservative or not conservative enough; to support the Liberal Opposition in the rare cases when they thought the Opposition was in the right; and to support the Irish Nationalists when they believed that these were unfairly dealt with, or when they believed, which happened much more frequently, that to support the Irishmen would be an annoyance to the party in power.

The Fourth party was made up of numbers exactly corresponding with the title which had been given to it. Four men, including the leader, constituted the whole strength of this little army. These men were Lord Randolph Churchill, Arthur J. Balfour, John Gorst (now Sir John Gorst), and Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, who has during more recent years withdrawn altogether from parliamentary life and given himself up to diplomacy, in which he has won much honorable distinction. Sir John Gorst has recently held office in the Government, and is believed to have given and felt[3] little satisfaction in his official career. He is a man of great ability and acquirements, but these have been somewhat thrown away in the business of administration.

The Fourth Party certainly did much to make the House of Commons a lively place. Its members were always in attendance—the whole four of them—and no one ever knew where, metaphorically, to place them. They professed and made manifest open scorn for the conventionalities of party life, and the parliamentary whips never knew when they could be regarded as supporters or opponents. They were all effective debaters, all ready with sarcasm and invective, all sworn foes to dullness and routine, all delighting in any opportunity for obstructing and bewildering the party which happened to be in power. The members of the Fourth party had each of them a distinct individuality, although they invariably acted together and were never separated in the division lobbies. A member of the House of Commons likened them once in a speech to D'Artagnan and his Three Musketeers, as pictured in the immortal pages of the elder Dumas. John Gorst he described as Porthos, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff as Athos, and Arthur Bal[4]four as the sleek and subtle Aramis. When I entered Parliament I was brought much into companionship with the members of this interesting Fourth party. One reason for this habit of intercourse was that we sat very near to one another on the benches of the House. The members of the Irish Nationalist party then, as now, always sat on the side of the Opposition, no matter what Government happened to be in power, for the principle of the Irish Nationalists is to regard themselves as in perpetual opposition to every Government so long as Ireland is deprived of her own national legislature. Soon after I entered the House a Liberal Government was the result of a general election, and the Fourth party, as habitually conservative, sat on the Opposition benches. The Fourth party gave frequent support to the Irish Nationalists in their endeavors to resist and obstruct Government measures, and we therefore came into habitual intercourse, and even comradeship, with Lord Randolph Churchill and his small band of followers.

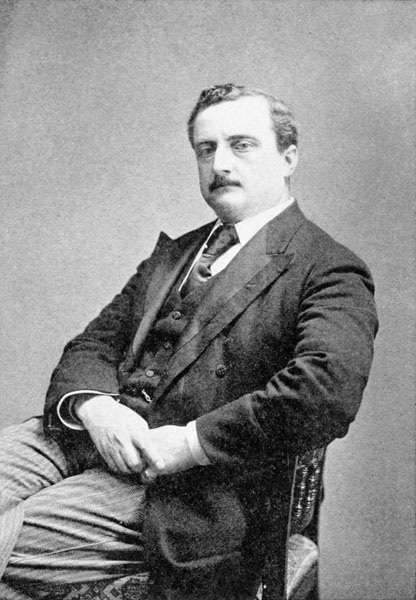

Arthur Balfour bore little resemblance, in appearance, in manners, in debating qualities, and apparently in mould of intellect, to any of the three men with whom he was then con[5]stantly allied. He was tall, slender, pale, graceful, with something of an almost feminine attractiveness in his bearing, although he was as ready, resolute, and stubborn a fighter as any one of his companions in arms. He had the appearance and the ways of a thoughtful student and scholar, and one would have associated him rather with a college library or a professor's chair than with the rough and boisterous ways of the House of Commons. He seemed to have come from another world of thought and feeling into that eager, vehement, and sometimes rather uproarious political assembly. Unlike his uncle, Lord Salisbury, he was known to enjoy social life, but he was especially given to that select order of æsthetic social life which was "sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought," a form of life which was rather fashionable in society just then. But it must have been clear even to the most superficial observer that he had a decided gift of parliamentary capacity. He was a fluent and a ready speaker and could bear an effective part in any debate at a moment's notice, but he never declaimed, never indulged in any flight of eloquence, and seldom raised his clear and musical voice much above the conversational[6] pitch. His choice of language was always happy and telling, and he often expressed himself in characteristic phrases which lived in the memory and passed into familiar quotation. He had won some distinction as a writer by his "Defense of Philosophic Doubt," by a volume of "Essays and Addresses," and more lately by his work entitled "The Foundations of Belief." The first and last of these books were inspired by a graceful and easy skepticism which had in it nothing particularly destructive to the faith of any believer, but aimed only at the not difficult task of proving that a doubting ingenuity can raise curious cavils from the practical and argumentative point of view against one creed as well as against another. The world did not take these skeptical ventures very seriously, and they were for the most part regarded as the attempts of a clever young man to show how much more clever he was than the ordinary run of believing mortals. Balfour's style was clear and vigorous, and people read the essays because of the writer's growing position in political life, and out of curiosity to see how the rising young statesman could display himself as the avowed advocate of philosophic skepticism.

Arthur Balfour took a conspicuous part in the attack made upon the Liberal Government in 1882 on the subject of the once famous Kilmainham Treaty. The action which he took in this instance was avowedly inspired by a desire to embarrass and oppose the Government because of the compromise into which it had endeavored to enter with Charles Stewart Parnell for some terms of agreement as to the manner in which legislation in Ireland ought to be administered. The full history of what was called the Kilmainham Treaty has not, so far as I know, been ever correctly given to the public, and it is not necessary, when surveying the political career of Mr. Balfour, to enter into any lengthened explanation on the subject. Mr. Parnell was in prison at the time when the arrangement was begun, and those who were in his confidence were well aware that he was becoming greatly alarmed as to the state of Ireland under the rule of the late W. E. Forster, who was then Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant, and under whose operations leading Irishmen were thrown into prison on no definite charge, but because their general conduct left them open in the mind of the Chief Secretary to the suspicion that their public agi[8]tation was likely to bring about a rebellious movement. Parnell began to fear that the state of the country would become worse and worse if every popular movement were to be forcibly repressed at the time when the leaders in whom the Irish people had full confidence were kept in prison and their guidance, control, and authority withdrawn from the work of pacification. The proposed arrangement, whether begun by Mr. Parnell himself or suggested to him by members of his own party or of the English Radical party, was simply an understanding that if the leading Irishmen were allowed to return to their public work the country might at least be kept in peace while English Liberalism was devising some measures for the better government of Ireland. The arrangement was in every sense creditable alike to Parnell and to the English Liberals who were anxious to cooperate with him in such a purpose. But it led to some disturbance in Mr. Gladstone's government and to Mr. Forster's resignation of his office. In 1885, when the Conservatives again came into power and formed a government, Balfour was appointed President of the Local Government Board and afterwards became Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant[9]—in other words, Chief Secretary for Ireland. He had to attempt a difficult, or rather, it should be said, an impossible task, and he got through it about as well as, or as badly as, any other man could have done whose appointed mission was to govern Ireland on Tory principles for the interests of the landlords and by the policy of coercion.

Balfour, it should be said, was never, even at that time, actually unpopular with the Irish National party. We all understood quite well that his own heart did not go with the sort of administrative work which was put upon him; his manners were always courteous, agreeable, and graceful; he had a keen, quiet sense of humor, was on good terms personally with the leading Irish members, and never showed any inclination to make himself needlessly or wantonly offensive to his opponents. He was always readily accessible to any political opponent who had any suggestion to make, and his term of office as Chief Secretary, although of necessity quite unsuccessful for any practical good, left no memories of rancor behind it in the minds of those whom he had to oppose and to confront. More lately he became First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of[10] Commons, and the remainder of his public career is too well known to call for any detailed description here. My object in this article is rather to give a living picture of the man himself as we all saw him in public life than to record in historical detail the successive steps by which he ascended to his present high position, or rather, it should be said, of the successive events which brought that place within his reach and made it necessary for him to accept it. For it is only fair to say that, so far as outer observers could judge, Mr. Balfour never made his career a struggle for high positions. So clever and gifted a man must naturally have had some ambition in the public field to which he had devoted so absolutely his time and his talents. But he seemed, so far as one could judge, to have in him none of the self-seeking qualities which are commonly seen in the man whose purpose is to make his parliamentary work the means of arriving at the highest post in the government of the State. On the contrary, his whole demeanor seemed to be rather that of one who is devoting himself unwillingly to a career not quite congenial. He always appeared to me to be essentially a man of literary, scholarly, and even retiring tastes, who[11] has a task forced upon him which he does not feel quite free to decline, and who therefore strives to make the best of a career which he has not chosen, but from which he does not feel at liberty to turn away. Most men who have attained the same political position give one the idea that they feel a positive delight in parliamentary life and warfare, and that nature must have designed them for that particular field and for none other. The joy in the strife which men like Palmerston, like Disraeli, and like Gladstone evidently felt never showed itself in the demeanor of Arthur Balfour. There was always something in his manner which spoke of a shy and shrinking disposition, and he never appeared to enter into debate for the mere pleasure of debating. He gave the idea of one who would much rather not make a speech were he altogether free to please himself in the matter, and as if he were only constraining himself to undertake a duty which most of those around him were but too glad to have an opportunity of attempting.

There are instances, no doubt, of men gifted with an absolute genius for eloquent speech who have had no natural inclination for debate and would rather have been free from any ne[12]cessity for entering into the war of words. I have heard John Bright say that he would never make a speech if he did not feel it a duty imposed upon him, and that he would never enter the House of Commons if he felt free to keep away from its debates. Yet Bright was a born orator and was, on the whole, I think, the greatest public and parliamentary orator I have ever heard in England, not excluding even Gladstone himself. Bright had all the physical qualities of the orator. He had a commanding presence and a voice of the most marvelous intonation, capable of expressing in musical sound every emotion which lends itself to eloquence—the impassioned, the indignant, the pathetic, the appealing, and the humorous. Then I can recall an instance of another man, not, indeed, endowed with Bright's superb oratorical gifts, but who had to spend the greater part of his life since he attained the age of manhood in the making of speeches within and outside the House of Commons. I am thinking now of Charles Stewart Parnell. I know well that Parnell would never have made a speech if he could have avoided the task, and that he even felt a nervous dislike to the mere putting of a question in the House. But no[13] one would have known from Bright's manner when he took part in a great debate that he was not obeying in congenial mood the full instinct and inclination of a born orator. Nor would a stranger have guessed from Parnell's clear, self-possessed, and precise style of speaking that he was putting a severe constraint upon himself when he made up his mind to engage in parliamentary debate. There is something in Arthur Balfour's manner as a speaker which occasionally reminds me of Parnell and his style. The two men had the same quiet, easy, and unconcerned fashion of utterance, always choosing the most appropriate word and finding it without apparent difficulty; each man seemed, as I have already said of Balfour, to be thinking aloud rather than trying to convince the listeners; each man spoke as if resolved not to waste any words or to indulge in any appeal to the mere emotions of the audience. But the natural reluctance to take any part in debate was always more conspicuous in the manner of Balfour than even in that of Parnell.

Balfour is a man of many and varied tastes and pursuits. He is an advocate of athleticism and is especially distinguished for his devotion to the game of golf. He obtained at one[14] time a certain reputation in London society because of the interest he took in some peculiar phases of fanciful intellectual inventiveness. He was for a while a leading member, if not the actual inventor, of a certain order of psychical research whose members were described as The Souls. More than one novelist of the day made picturesque use of this singular order and enlivened the pages of fiction by fancy portraits of its leading members. Such facts as these did much to prevent Balfour from being associated in the public mind with only the rivalries of political parties and the incidents of parliamentary warfare. One sometimes came into social circles where Balfour was regarded chiefly as the man of literary tastes and somewhat eccentric intellectual developments. All this cast a peculiar reflection over his career as a politician and filled many observers with the idea that he was only playing at parliamentary life, and that his other occupations were the genuine realities for him. Even to this day there are some who persist in believing that Balfour, despite his prolonged and unvarying attention to his parliamentary duties, has never given his heart to the prosaic and practical work of administrative office and the business[15] of maintaining his political party. Yet it has always had to be acknowledged that no man attended more carefully and more closely to such work when he had to do it, and that the most devoted worshiper of political success could not have been more regular and constant in his attention to the business of the House of Commons. People said that he was lazy by nature, that he loved long hours of sleep and of general rest, and that he detested the methodical and mechanical routine of official work. But I have not known any Minister of State who was more easy of approach and more ready to enter into the driest details of departmental business than Arthur Balfour. I may say, too, that, whenever appeal was made to him to forward any good work or to do any act of kindness, he was always to be found at his post and was ever ready to lend a helping hand if he could.

I remember one instance of this kind which I have no hesitation in mentioning, although I am quite sure Mr. Balfour had little inclination for its obtaining publicity. Not very many years ago it was brought to my knowledge that an English literary woman who had won much and deserved distinction as a novel-[16]writer had been for some time sinking into ill health, had been therefore prevented from going on with her work, and had in the mean time been perplexed by worldly difficulties and embarrassments which interfered sadly with her prospects and made her a subject of well-merited sympathy. Some friends of the authoress were naturally anxious, if possible, to give her a helping hand, and the idea occurred to them that she would be a most fitting recipient of assistance to be bestowed by a department of the State. One of her friends, himself a distinguished novelist, who happened to be also a friend of mine, spoke to me with this object, assuming that, as an old parliamentary hand, I knew more than most writers of books would be likely to know about the manner in which such help might be obtained. There is in England a fund—a very small fund, truly—at the disposal of the Government for the help of deserving authors who happen to be in distress. This fund is at the disposal of the First Lord of the Treasury, the office which was then, as now, held by Arthur Balfour. I was still at that time a member of the House of Commons, and my friend suggested that, as I knew something about the whole business, I might be a[17] suitable person to represent the case to the First Lord of the Treasury and make appeal for his assistance. My friend's belief was that the application might come with more effect from one who had been for a long time a member of Parliament, and whose name would therefore be known to the First Lord of the Treasury, than from a literary man who had nothing to do with parliamentary life. Nothing could give me greater pleasure than to become the medium through which the appeal might be brought under the notice of the First Lord, but I felt some difficulty and doubt because of the conditions of the time. England was then in the most distracting period of the South African war. We were hearing every day of fresh mishaps and disasters in the campaign. Arthur Balfour was Leader of the House of Commons, and had to deal every day with questions, with demands for explanation, with arguments and debates turning on the events of the war. It seemed to me to be rather a venturesome enterprise to attempt to gain the attention of a minister thus perplexingly occupied for a matter of merely private and individual concern. I feared that an overworked statesman might feel naturally inclined to remit the subject to[18] the care of some mere official, and that time might thus be lost and the needed helping hand be long delayed. I undertook the task, however, and I wrote to Mr. Balfour at once. I received the very next day a reply written in Mr. Balfour's own hand, expressing his cordial willingness to consider the subject, his sympathy with the purpose of the appeal, and his hope that some help might be given to the distressed novelist. Mr. Balfour promptly took the matter in hand, and the result was that a grant was made from the State fund to secure the novelist against any actual distress. Now, I do not want to make too much of this act of ready kindness done by Mr. Balfour. The appeal was made for a most deserving object; the fund from which help was to be given was entirely at Mr. Balfour's disposal; and it is probable that any other First Lord in the same circumstances would have come to the same decision. But how easy it would have been for Mr. Balfour to put the whole matter into the hands of some subordinate, and not to add a new trouble to his own intensely busy life at such an exciting crisis by entering into the close consideration of a mere question of State beneficence! I certainly should not have been[19] surprised if I had not received an answer to my letter for several days after I had sent it, and if even then it had come from some subordinate in the Government department. But in the midst of all his incessant and distracting occupations at a most exciting period of public business Mr. Balfour found time to consider the question himself, to reply with his own hand, and to see that the desired help was promptly accorded. I must say that I think this short passage of personal history speaks highly for the kindly nature and the sympathetic promptitude of Arthur Balfour.

For a long time there had been much speculation in these countries concerning the probable successor to Lord Salisbury, whenever Lord Salisbury should make up his mind to resign the position of Prime Minister. We all knew that that resignation was sure to come soon, although very few of us had any idea that it was likely to come quite so soon. The general opinion was that the country would not be expected, for some time at least, to put up again with a Prime Minister in the House of Lords. If, therefore, the new Prime Minister had to be found in the House of Commons, there seemed to be only a choice between two[20] men, Arthur Balfour and Joseph Chamberlain. It would be hard to find two men in the House of Commons more unlike each other in characteristic qualities and in training than these two. They are both endowed with remarkable capacity for political life and for parliamentary debate, "but there," as Byron says concerning two of whom one was a Joseph, "I doubt all likeness ends between the pair." Balfour is an aristocrat of aristocrats; Chamberlain is essentially a man of the British middle class—even what is generally called the lower middle class. Balfour has gone through all the regular course of university education; Chamberlain was for a short time at University College School in London, a popular institution of modern origin which does most valuable educational work, but is not largely patronized by the classes who claim aristocratic position. Balfour is a constant reader and student of many literatures and languages; "Mr. Chamberlain," according to a leading article in a London daily newspaper, "to put it mildly, is not a bookworm." Balfour loves open-air sports and is a votary of athleticism; Chamberlain never takes any exercise, even walking exercise, when he can possibly avoid the trouble. Balfour is an æsthetic lover of all[21] the arts; Chamberlain has never, so far as I know, given the slightest indication of interest in any artistic subject. Balfour is by nature a modest and retiring man; Chamberlain is always "Pushful Joe." The stamp and character of a successful municipal politician are always evident in Chamberlain, while Balfour seems to be above all other things the university scholar and member of high society. I suppose it must have been a profound disappointment to Chamberlain that he was not offered the place of Prime Minister, but it would be hardly fair to expect that such a place would not be offered to the First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Commons, even if that First Lord did not happen to be a nephew of the retiring Prime Minister.

It would be idle just now to enter into any speculation as to whether Mr. Arthur Balfour will long continue to hold the office. If he should make up his mind, as was at one time thought possible by many observers, to accept a peerage and become Prime Minister in the House of Lords, such a step would undoubtedly be a means of pacifying the partisans of Chamberlain, for Chamberlain would then become, almost as a matter of course, the leader of the[22] Conservative government in the House of Commons, and this elevation might well satisfy his ambition and give his pushful energy work enough to do. But the country has of late become less and less satisfied with the practice of having a Prime Minister removed from the centre of active life and hidden away in the enervating atmosphere of the House of Lords. The friends of Mr. Balfour are naturally inclined to hope and believe that he will not bury himself in such a living tomb. His path will in any case be perplexed by many difficulties and obstructions. My own impression is that the inevitable reaction is destined to come before long. The next general election may prove that the country at large is tired of a Conservative administration. The public mind will soon get over the feverish excitement created by the South African war, and people will begin to remember that England had won battles and annexed territory before there ever was a Transvaal Republic, and found then, as she will find now, that successes abroad do not relieve her from the necessity of managing successfully her business at home. It has to be borne in mind, too, that the House of Commons does not really originate anything in the work[23] of important legislation. The best business of the Liberal party begins outside the House of Commons—begins with the people and with those who take an interest in the welfare of the people and have brains and foresight enough to find out how it can be most thoroughly promoted. All great reforms have their origin outside the House of Commons and are only taken up by the House of Commons when it is felt that the popular demand is so earnest that it must receive serious consideration. The country will soon begin to realize the fact that, shamefully mismanaged as the War Department may have been during the recent campaigns, the War Department is not by any means the only national institution which needs the strong hand of reform. The spirited foreign policy has had its innings, and the condition of the people at home must have its turn very soon. The Liberal party has its work cut out for it, and where there is the work to be done a Liberal party will be found to do it. So far as I can read the signs of the times, I am encouraged to hope that a great opportunity is waiting for the Liberal party, and I cannot see the slightest reason to doubt that a Liberal party will be found ready for the opportunity and[24] equal to it. A Tory Prime Minister has, indeed, before now had the judgment and the energy to forestall the Liberal party in the great work of domestic reform, but I do not believe that even the warmest admirers of Mr. Balfour imagine that he is quite the man to undertake such an enterprise. Arthur Balfour is, according to my judgment, the best man for the place to be found in the Conservative ranks at present, but I do not suppose that he is destined just now to be anything more than a stop-gap. I admire his great and varied abilities, I recognize his brilliant debating powers, and I have felt the charm of his genial and graceful manners, but I do not believe him capable of maintaining the present administration against the rising force of a Liberal reaction.

The retirement of Lord Salisbury from the position of Prime Minister and the leadership of the Conservative Government withdraws into comparative obscurity the most interesting and even picturesque figure in the English Parliamentary life of the present day. Even the most uncompromising opponents of the Prime Minister and of his political party felt a sincere respect for the character, the intellect, and the bearing of the man himself. Every one gave Lord Salisbury full credit for absolute sincerity of purpose, for superiority to any personal ambitions or mere self-seeking, for an almost contemptuous disregard of State honors and political fame.

Yet it was not that Lord Salisbury was habitually careful and measured in his speech, that he was never hurried into rash utterances, that he was guided by any particular anxiety to avoid offending the susceptibilities of others, or, indeed, that, as a rule, he preferred to use sooth[28]ing words in political controversy. He has, on the contrary, a marvelous gift of sarcasm and of satirical phrase-making, and he was only too ready to indulge occasionally this peculiar capacity at the expense of political friend as well as of political foe. In his early days of public life, when he sat in the House of Commons as a nominal follower of Mr. Disraeli, he was once described in debate by his nominal leader as "a master of flouts and jeers." On another occasion Disraeli spoke of him, although not in Parliamentary debate, as a young man whose head was on fire. In later days, and even when he had held high administrative office, Lord Salisbury often indulged in sudden outbursts of contemptuous humor which for a time seemed likely to provoke indignant remonstrance even from his own followers. One illustration of this unlucky tendency towards contemptuous utterance may be found in his famous allusion several years ago to a native of Hindustan, who had been elected to a seat in the House of Commons, as "a black man." That was a time when every English public man recognized the great importance of indulging in no expression which might seem calculated to wound the susceptibilities of the many races who have been[29] brought under the rule of the Imperial system in the Indian dominions of the sovereign. The member of Parliament thus scornfully alluded to was no more a black man than Lord Salisbury himself. He was one of the Parsee races chiefly found in the Bombay regions, almost European in the color of their skin, and he looked more like a German scholar than a native of any sunburnt land. No one defended Lord Salisbury's rash utterance, but many people excused it on the ground that it was only Lord Salisbury's way; that he never meant any harm, but could not resist the temptation of saying an amusing and sarcastic thing when it came into his mind. The truth is that Lord Salisbury's odd humor is a peculiarity without which he could not be the complete Lord Salisbury, and an unlucky expression was easily forgiven because of the many brilliant flashes of genuine and not unfair sarcasm with which he was accustomed to illumine a dull debate. When he succeeded to his father's title, and had, therefore, to leave the House of Commons and take his place in the House of Lords, every one felt that the representative chamber had lost one of its most attractive figures, and that the hereditary chamber was not exactly the place[30] in which such a man could find his happiest hunting-ground. Yet even in the somber and unimpressive House of Lords, Lord Salisbury was able, whenever the humor took him, to brighten the debates by his apt illustrations and his witty humor.

Lord Salisbury resigns his position as Prime Minister at a time of life when, according to the present standards of age, a man is still supposed to have long years of good work before him. Lord Palmerston's career as Prime Minister was cut short only by his death, an event which occurred when Palmerston was in his eighty-first year. Gladstone was more than ten years older than Lord Salisbury is now when he voluntarily gave up his position as head of a Liberal administration. Lord Beaconsfield's time of birth is somewhat uncertain, but he must have been some seventy-seven years of age and had lost none of his powers as a debater when his brilliant life came to its close. We may take it for granted that Lord Salisbury had been for a long time growing tired of the exalted political position which had of late become uncongenial with his habits and his frame of mind. By the death of his wife he had lost the most loved companion of his home,[31] his intellectual tastes, and his political career. A pair more thoroughly devoted to each other than Lord and Lady Salisbury could hardly have been found even in the pages of romance. The whole story of that marriage and that married life would have supplied a touching and a telling chapter for romance. Early in his public career Lord Salisbury fell in love with a charming, gifted, and devoted woman, whom a happy chance had brought in his way. She was the daughter of an eminent English judge, the late Baron Alderson; and although such a wife might have been thought a suitable match even for a great aristocrat, it appears that the Lord Salisbury of that time, the father of the late Prime Minister, who was then only Lord Robert Cecil, did not approve of the marriage, and the young pair had to take their own way and become husband and wife without regard for the family prejudices. Lord Robert Cecil was then only a younger brother with a younger brother's allowance to live on, and the newly wedded pair had not much of a prospect before them, in the conventional sense of the words. Lord Robert Cecil accepted the situation with characteristic courage and resolve. There seemed at that time no likelihood of his[32] ever succeeding to the title and the estates, for his elder brother was living, and was, of course, heir to the ancestral title and property. Lord Robert Cecil had been gifted with distinct literary capacity, and he set himself down to work as a writer and a journalist. He became a regular contributor to the "Saturday Review," then at the height of its influence and fame, and he wrote articles for some of the ponderous quarterly reviews of the time, brightening their pages by his animated and forcible style. He took a small house in a modest quarter of London, where artists and poets and authors of all kinds usually made a home then, far removed from West End fashion and courtly splendor, and there he lived a happy and productive life for many years. He had obtained a seat in the House of Commons as a member of the Conservative party, but he never pledged himself to support every policy and every measure undertaken by the Conservative leaders, whether they happened to be in or out of office. Lord Robert always acted as an independent member, although he adhered conscientiously to the cardinal principles of that Conservative doctrine which was his political faith throughout his life. He soon won for[33] himself a marked distinction in the House of Commons. He was always a brilliant speaker, but was thoughtful and statesmanlike as well as brilliant. He never became an orator in the higher sense of the word. He never attempted any flights of exalted eloquence. His speeches were like the utterances of a man who is thinking aloud and whose principal object is to hold and convince his listeners by the sheer force of argument set forth in clear and telling language. Many of his happy phrases found acceptance as part of the ordinary language of political and social life and became in their way immortal. Up to the present day men are continually quoting happy phrases drawn from Lord Robert Cecil's early speeches without remembering the source from which they came.

Such a capacity as that of Lord Robert Cecil could not long be overlooked by the leaders of his party, and it soon became quite clear that he must be invited to administrative office. I ought to say that, after Lord Robert had completed his collegiate studies at Oxford, he devoted himself for a considerable time to an extensive course of travel, and he visited Australasia, then but little known to young Englishmen of his rank, and he actually did much[34] practical work as a digger in the Australian gold mines, then newly discovered. He had always a deep interest in foreign affairs, and it was greatly to the advantage of his subsequent career that he could often support his arguments on questions of foreign policy by experience drawn from a personal study of the countries and States forming successive subjects of debate. Suddenly his worldly prospects underwent a complete change. The death of his elder brother made him heir to the family title and the great estates. He became Viscount Cranborne in succession to his dead brother. I may perhaps explain, for the benefit of some of my American readers, that the heir to a peerage who bears what is called a courtesy title has still a right to sit, if elected, in the House of Commons. It is sometimes a source of wonder and puzzlement to foreign visitors when they find so many men sitting in the House of Commons who actually bear titles which would make it seem as if they ought to be in the House of Lords. The eldest sons of all the higher order of peers bear such a title, but it carries with it no disqualification for a seat in the House of Commons, if the bearer of it be duly elected to a place in the repre[35]sentative chamber. When the bearer of the courtesy title succeeds to the actual title belonging to the house, he then, as a matter of course, becomes a peer, has to enter the House of Lords, and would no longer be legally eligible to sit in the representative chamber. Lord Palmerston's presence in the House of Commons was often a matter of wonder to foreign visitors, for in all the days to which my memory goes back, Lord Palmerston seemed too old a man to have a father alive and in the House of Lords. I have had to explain the matter to many a stranger, and it only gives one other illustration of the peculiarities and anomalies which belong to our Parliamentary system. Palmerston's was not a courtesy title; the noble lord was a peer in his own right; but then he was merely an Irish peer, and only a certain number of Irish peers are entitled to sit in the House of Lords. The more fortunate, for so I must describe them, of the Irish peers not thus entitled to sit in the hereditary chamber are free to seek election for an English constituency in the House of Commons and to obtain it, as Lord Palmerston did. Lord Viscount Cranborne, therefore, continued for a time to hold the place in the House of Com[36]mons which he had held as Lord Robert Cecil. In 1866 Lord Cranborne entered office, for the first time, as Secretary of State for India during the administration of Lord Derby.

The year following brought about a sort of crisis in Lord Cranborne's political career, and probably showed the general public of England, for the first time, what manner of man he really was. Up to that period he had been regarded by most persons, even among those who habitually gave attention to Parliamentary affairs, as a brilliant, independent, and somewhat audacious free-lance whose political conduct was usually directed by the impulse of the moment, and who made no pretensions to any fixed and ruling principles. That was the year 1867, when the Conservative Government under Lord Derby and Mr. Disraeli took it into their heads to try the novel experiment, for a Conservative party, of introducing a Reform Bill to improve and expand the conditions of the Parliamentary suffrage. Disraeli was the author of this new scheme, and it had been suggested to him by Mr. Gladstone's failure in the previous year with his measure of reform. Gladstone's reform measure did not go far enough to satisfy the genuine Radicals, while it went[37] much too far for a considerable number of doubtful and half-hearted Liberals, and it was strongly opposed by the whole Tory party. As usually happens in the case of every reform introduced by a Liberal administration, a secession took place among the habitual followers of the Government. The secession in this case was made famous by the name which Bright conferred upon it as the "Cave of Adullam" party; and by the co-operation of the seceding section with the Tory Opposition, the measure was defeated, and Mr. Gladstone went out of office. Disraeli saw, with his usual sagacity, that the vast mass of the population were in favor of some measure of reform, and when Lord Derby and he came into office he made up his mind that, as the thing had to be done, he and his colleagues might as well have the advantage of doing it. The outlines of the measure prepared for the purpose only shaped a very vague and moderate scheme of reform, but Disraeli was quite determined to accept any manner of compromises in order to carry some sort of scheme and to keep himself and his party in power. But then arose a new difficulty on which, with all his sagacity, he had not calculated. Lord Cranborne for the first[38] time showed that he was a man of clear and resolute political principle, and that he was not willing to sacrifice any of his conscientious convictions for the sake of maintaining his place in a Government. He was sincerely opposed to every project for making the suffrage popular and for admitting the mass of the workingmen of the country to any share in its government. I need hardly say that I am entirely opposed to Lord Cranborne's political theories, but I am none the less willing to render full justice to the sincerity, not too common among rising public men, which refused to make any compromise on a matter of political principle. Lord Cranborne was then only at the opening of his administrative career, and he must have had personal ambition enough to make him wish for a continuance of office in a powerful administration. But he put all personal considerations resolutely aside, and resigned his place in the Government rather than have anything to do with a project which he believed to be a surrender of constitutional principle to the demands of the growing democracy. Lord Carnarvon and one or two other members of the administration followed his lead and resigned their places in the Government. I need not[39] enter into much detail as to the progress of the Disraeli reform measure. It is enough to say that Disraeli obtained the support of many Radicals by the Liberal amendments which he accepted, and the result was that a Tory Government carried to success a scheme of reform which practically amounted to the introduction of household suffrage. Lord Cranborne and those who acted with him held firmly to their principles, and steadily opposed the measure introduced by those who at the opening of the session were their official leaders and colleagues. I am convinced that even the most advanced reformers were ready to give a due meed of praise to the man who had thus made it evident that he preferred what he believed to be a political principle, even though he knew it to be the principle of a losing cause, to any consideration of personal advancement.

Some of us felt sure that we had then learned for the first time what manner of man Lord Cranborne really was. We had taken him for a bold and brilliant adventurer, and we found and were ready to acknowledge that he was a man of deep, sincere, and self-sacrificing convictions. I have never from that time changed my opinions with regard to Lord Cranborne's per[40]sonal character. His career interested me from the first moment that I had an opportunity of observing it, and I may say that from an early period of my manhood I had much opportunity of studying the ways and the figures of Parliamentary life. But until Lord Cranborne had taken this resolute position on the reform question, I had never given him credit for any depth of political convictions. The impression I formed of him up to that time was that he was merely a younger son of a great aristocratic family, who had a natural aptitude alike for literature and for politics, and that he was following in Parliament the guidance of his own personal humors and argumentative impulses, and that he was ready to sacrifice in debate not only his friends but his party for the sake of saying a clever thing and startling his audience into reluctant admiration. From those days of 1867 I knew him to be what all the world now knows him to be, a man of deep and sincere convictions, ever following the light of what he believes to be political wisdom and justice. I can say this none the less readily because I suppose it has hardly ever been my fortune to agree with any of Lord Salisbury's utterances on questions of political importance.

In 1868 the career of Lord Cranborne in the House of Commons came to an end by the death of his father. He succeeded to the title of Marquis of Salisbury, and became, as a matter of course, a member of the House of Lords. He was thus withdrawn while still a comparatively young man from that stirring field of splendid debate where his highest qualities as a speaker could alone have found their fitting opportunity. I need not trace out his subsequent public career with any sequence of detail. We all know how from that time to this he has held high office, has come to hold the highest offices in the State whenever his political party happened to be in power. He has been Foreign Secretary; he has been Prime Minister in three Conservative administrations. For a time he actually combined the functions of Prime Minister and those of Foreign Secretary. He was envoy to the great conference at Constantinople in 1876 and 1877, and he took part in the Congress of Berlin, that conference which Lord Beaconsfield declared brought to England peace with honor. Everything that a man could have to gratify his ambition Lord Salisbury has had since the day when he succeeded to his father's title and estates. His own intel[42]lectual force and his political capacity must undoubtedly have made a way for him to Parliamentary influence and success even if he had always remained Lord Robert Cecil, and his elder brother had lived to succeed to the title. But from the moment when Lord Robert Cecil became the heir, it was certain that his party could not venture to overlook him. He might have made eccentric speeches, he might have indulged in sarcastic and scornful allusions to his political leaders, he might have allowed obtrusive scruples of conscience to interfere with the interests of his party, but none the less it became absolutely necessary that the Conservative politicians should accept, when opportunity came, the leadership of the Marquis of Salisbury. "Thou hast it all"—the words which Banquo applies to Macbeth—might have been said of Lord Salisbury when he became for the first time Prime Minister.

Lord Salisbury certainly did not achieve his position by any of the arts, even the less culpable arts, which for a time secured to Macbeth the highest reach of his ambition. Lord Salisbury's leadership came to him and was not sought by him. I cannot help thinking, however, that, after he had once attained that su[43]preme position in his party, the remainder of his public career has been something in the nature of an anticlimax. Was it that the chill and deadening influence of the House of Lords proved too depressing for the energetic and vivacious spirit which had won celebrity for Lord Robert Cecil in the House of Commons? Was it that Lord Salisbury, when he had attained the height of his ambition, became a victim to that mood of reaction which compels such a man to ask himself whether, after all, the work of ascent was not much better than the attained elevation? Lord Salisbury's years of high office coming now thus suddenly to an end give to me at least the melancholy impression of an unfulfilled career. The influence of the Prime Minister, so far as mere outsiders can judge of it, has always been exerted in foreign affairs for the promotion of peace. Even the late war in South Africa is not understood to have been in any sense a war of his seeking. The general belief is that the policy of war was pressed upon him by influences which at the time he was not able to control—influences which would only have become all the stronger if he had refused to accept the responsibility of Prime Minister and had left it to others to[44] carry on the work of government. However this may be, it can hardly be questioned that of late years Lord Salisbury had become that which nobody in former days could ever suppose him likely to become, the mere figurehead of an administration. Lord Salisbury's whole nature seems to have been too sincere, too free from mere theatrical arts, to allow him to play the part of leader where he had no heart in the work of leadership. A statesman like Disraeli might have disapproved of a certain policy and done his best to reason his colleagues out of it, but nevertheless, when he found himself likely to be overborne, would have immersed himself deliberately in all the new-born zeal of the convert and would have behaved thenceforward as if his whole soul were in the work which had been put upon him to do. Lord Salisbury is most assuredly not a man of this order, and he never would or could put on an enthusiasm which he did not feel in his heart. We can all remember how, at the very zenith of British passion against China during the recent political convulsions and the intervention of the foreign allies, Lord Salisbury astonished and depressed some of his warmest admirers by a speech which he made at Exeter Hall, a speech[45] which, metaphorically at least, threw the coldest of cold water on the popular British ardor for forcing Western civilization on the Chinese people.

Lord Salisbury's frame of mind was one which could never allow him to become even for a moment a thorough Jingo, and through all the later years of his power he held the office of Prime Minister at a time when Jingoism was the order of the day among the outside supporters of the Conservative Government. He never had a fair chance for the full development of his intellectual faculties while he remained at the head of a Conservative administration. Under happier conditions he might have been a great Prime Minister and a leading force in political movement, but his intellect, his tastes, and his habits of life did not allow him to pay much deference to the prejudices and passions of those on whom he was compelled to rely for support. There was too much in him of the thinker, the scholar, and the recluse to make him a thoroughly effective leader of the party who had to acknowledge his command. He loved reading, he loved literature and art, and he took no delight in the formal social functions which are in our days an im[46]portant part of successful political administration. He could not be "hail-fellow-well-met" with every pushing follower who made it a pride to be on terms of companionship with the leader of the party. I have often heard that he had a singularly bad memory for faces, and that many a devoted Tory follower found his enthusiasm chilled every now and then by the obvious fact that the Prime Minister did not seem to remember anything about the identity of his obtrusive admirer. Much the same thing has been said over and over again about Mr. Gladstone, but then Gladstone had the inborn genius of leadership, threw his soul into every great political movement, and did not depend in the slightest degree on his faculty for appreciating and conciliating every individual follower. Lord Salisbury's tastes were for the society of his close personal friends, and I believe no man could be a more genial host in the company of those with whom he loved to associate; but he had no interest in the ordinary ways of society and made no effort to conciliate those with whom he found himself in no manner of companionship. He did not even take any strong interest in the study of the most remarkable figures in the political world around[47] him, if he did not feel drawn into sympathy with their ways and their opinions. On one occasion, when a report had got about in the newspapers that Lord Salisbury was often seen in friendly companionship with the late Mr. Parnell in the smoking-room of the House of Commons, Lord Salisbury publicly stated that he had never, to his knowledge, seen Parnell, and had never been once in the House of Commons smoking-room.

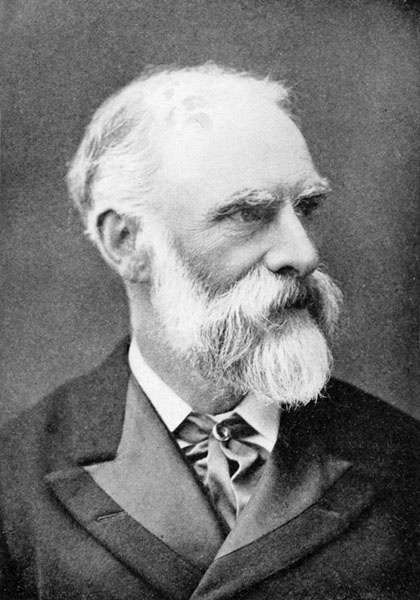

No man has been better known, so far as personal appearance was concerned, to the general English public than Lord Salisbury. He has been as well known as Mr. Gladstone himself, and one cannot say more than that. He was a frequent walker in St. James's Park and other places of common resort in the neighborhood of the Houses of Parliament. Every one knew the tall, broad, stooping figure with the thick head of hair, the bent brows, and the careless, shabby costume. No statesman of his time was more indifferent than Lord Salisbury to the dictates of fashion as regarded dress and deportment. He was undoubtedly one of the worst-dressed men of his order in London. In this peculiarity he formed a remarkable contrast to Lord Beaconsfield, who down to the[48] very end of his life took care to be always dressed according to the most recent dictates of fashion. All this was strictly in keeping with Lord Salisbury's character and temperament. The world had to take him as he was—he could never bring himself to act any part for the sake of its effect upon the public. My own impression is that when he was removed by the decree of fate into the House of Lords and taken away from the active, thrilling life of the House of Commons, he felt himself excluded from his congenial field of political action and had but little interest in the game of politics any more. He does not seem destined to a place in the foremost rank of English Prime Ministers, even of English Conservative Prime Ministers. But his is beyond all question a picturesque, a deeply interesting, and even a commanding figure in English political history, and the world will have reason to regret if his voluntary retirement from the position of Prime Minister should mean also his retirement from the field of political life.

Lord Rosebery was for a prolonged season the man in English political life upon whom the eyes of expectation were turned. He is a younger man than most of his political colleagues and rivals, but it is not because of his comparative youth that the eyes of expectation were and still are turned upon him. Not one of those who stand in the front ranks of Parliamentary life to-day could be called old, as we reckon age in our modern estimate. Palmerston, Gladstone, and Disraeli won their highest political triumphs after they had passed the age which Lord Salisbury and Sir William Harcourt have now reached; Mr. Balfour is still regarded in politics as quite a young man, and Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman has but lately been elected leader of the Liberal party in the House of Commons. Lord Rosebery has already held the highest political offices. He has been Foreign Secretary and he has been Prime Minister. He has been[52] leader of the Liberal party. No other public man in England has so many and so varied mental gifts, and no other public man has won success in so many distinct fields. We live in days when, for the time at least, the great political orator seems to have passed out of existence. The last great English orator died at Hawarden a few short years ago. We have, however, several brilliant and powerful Parliamentary debaters, and among these Lord Rosebery stands with the foremost, if he is not, indeed, absolutely the foremost. As an orator on what I may call great ceremonial occasions he is, according to my judgment, the very foremost we now have. As an after-dinner speaker—and after-dinner speaking counts for a great deal in the success of an English public man—he has never had an equal in England during my time. Then Lord Rosebery has delivered lectures or addresses in commemoration of great poets and philosophers and statesmen which may even already be regarded as certain of an abiding place in literature. Lord Rosebery is a literary man, an author as well as a statesman and an orator; he has written a life of Pitt which is already becoming a sort of classic in our libraries. There are profounder stu[53]dents, men more deeply read, than he, but I doubt if there are many men living who have so wide an acquaintance with general literature. He is a lover as well as a student and a connoisseur of art, he is an accomplished yachtsman, has a thorough knowledge of horses, is famous on the turf, and the owner of two horses which won the Derby. The legendary fairy godmother seems to have showered upon him at his birth all her richest and most various gifts, and no malign and jealous sprite appears to have come in, as in the nursery stories, to spoil any of the gifts by a counteracting spell. He was born of great family and born to high estate; he married a daughter of the house of Rothschild; he has a lordly home near Edinburgh in Scotland, a noble house in the finest West End square of London, and a delightful residence in one of our most beautiful English counties.

Lord Rosebery is one of the most charming talkers whom it has ever been my good fortune to meet. He has a keen sense of humor, a happy art of light and delicate satire, and, in private conversation as well as in Parliamentary debate, he has a singular facility for the invention of expressive and successful phrases which[54] tell their whole story in a flash. One might well be inclined to ask what the kindly fates could have done for Lord Rosebery that they have left undone. Nevertheless, the truth has to be told, that up to this time Lord Rosebery has not accomplished as much of greatness as most of us confidently expected that he would achieve.

I have been, perhaps, somewhat too hasty in saying that no counteracting spell had in any way marred the influence of the gifts which the fairies had so lavishly bestowed on Lord Rosebery. One stroke of ill fortune—ill fortune, that is, for an English political leader—was certainly directed against him. Nature must have meant him to be a successful Prime Minister, and yet fortune denied him a seat in the House of Commons. He succeeded to his grandfather's peerage at an early period of his life, and he had to begin his political career as a member of the House of Lords. He therefore missed all that splendid training for political warfare which is given in the House of Commons. It would not, perhaps, be quite easy for an American reader to understand how little the House of Lords counts for in the education of fighting statesmen.

When Charles James Fox was told in his declining years that the King, as a mark of royal favor, intended to make him a peer and thus remove him from the House of Commons into the House of Lords, he struck his forehead and exclaimed: "Good Heaven! he does not think it has come to that with me, does he?" Fox had had all the training that his genius needed in the House of Commons, and he was not condemned to pass into the House of Lords. Nothing but the inborn consciousness of a genius for political debate can stimulate a man to great effort in the House of Lords. Nothing turns upon a debate in that House. If a majority in the House of Lords were to pass a vote of censure three times a week on the existing Government, that Government would continue to exist just as if nothing had happened, and the public in general would hardly know that the Lords had been expressing any opinion on the subject. An ordinary sitting of the House of Lords is not expected to last for more than an hour or so, and the whole assembly often consists of some half a dozen peers. Now and again, during the course of a session, there is got up what may be called a full-dress debate when some great question is disturbing the[56] country, and the peers think that they ought to put on the appearance of being deeply concerned about it, and some noble lord who has a repute for wisdom or for eloquence gives notice of a formal motion, and then there is a lengthened discussion, and perhaps, on some extraordinary occasion, the peers may sit to a late hour and even take a division. But on such remarkable occasions the peer who induces the House to come together and listen to his oration is almost sure to be one who has had his training in the House of Commons and has made his fame as an orator there.

Now, I cannot but regard it as a striking evidence of Lord Rosebery's inborn fitness to be an English political leader that he should have got over the dreary discouragement of such a training-school, and should have practiced the art of political oratory under conditions that might have filled Demosthenes himself with a sense of the futility of trying to make a great speech where nothing whatever was likely to come of it. Lord Rosebery, however, did succeed in proving to the House of Lords that they had among them a brilliant and powerful debater who had qualified himself for success without any help from the school in[57] which Lord Brougham and the brilliant Lord Derby, Lord Cairns, and Lord Salisbury had studied and mastered the art of Parliamentary eloquence.

But, indeed, Lord Rosebery appears to have had a natural inclination to seek and find a training-school for his abilities in places and pursuits that might have seemed very much out of the ordinary British aristocrat's way. Until a comparatively recent period, we had nothing that could be called a really decent system of municipal government in the greater part of London. We had, of course, the Lord Mayor and the municipality of the City of London, but then the City of London is only a very small patch in the great metropolis that holds more than five millions of people. London, outside the City, was governed by the old-fashioned parish vestries, and to some extent by a more recent institution which was called the Metropolitan Board of Works. Now, the Metropolitan Board of Works did not manage its affairs very well. There were disagreeable rumors and stories about contracts and jobbing and that sort of thing, and although matters were never supposed to have been quite so bad as they were in New York during days which I can[58] remember well, the days of Boss Tweed, there was enough of public complaint to induce Parliament, at the instigation of Lord Randolph Churchill, to abolish the Board of Works altogether and set up the London County Council, a thoroughly representative body elected by popular suffrage and responsible to its constituents and the public. Lord Rosebery threw himself heart and soul into the promotion of this better system of London municipal government. He became a member of the London County Council, was elected its first Chairman, and later on was re-elected to the same office. Now, I think it would be hardly possible for a man of Lord Rosebery's rank and culture and tastes to give a more genuine proof of patriotic public spirit than he did when he threw himself heart and soul into the work of a municipal council.

Up to that time the business of a London municipality had been regarded as something belonging entirely to the middle class or the lower middle class, something with which peers and nobles could not possibly be expected to have anything to do. A London Alderman had been from time out of mind a sort of figure of fun, a vulgar, fussy kind of person, who[59] bedizened himself in gaudy robes on festive occasions, and was noted for his love of the turtle in quite a different sense from that which Byron gives to the words. Lord Rosebery set himself steadily to the work of London municipal government at a most critical period in its history; his example was followed by men of rank and culture, and some of the most intellectual men of our day have been elected Aldermen of the London County Council. Only think of Frederic Harrison, the celebrated Positivist philosopher, the man of exquisite culture and refinement, the man of almost fastidious ways, the scholar and the writer, becoming an Alderman of the London County Council, and devoting himself to the duties of his position! Lord Rosebery undoubtedly has the honor of having done more than any other Englishman to raise the municipal government of London to that position which it ought to have in the public life of the State.

All that time Lord Rosebery was not neglecting any of the other functions and occupations which had been imposed upon him, or which he had voluntarily taken upon himself. He held the office of First Commissioner of Works in one of Mr. Gladstone's administrations, an office[60] involving the care of all the State buildings and monuments and parks of the metropolis. He was always to be seen at the private views of the Royal Academy and the other great picture galleries of the London season. He was always starting some new movement for the improvement of the breed of horses, and, indeed, there is a certain section of our community among whom Lord Rosebery is regarded, not as a statesman, or a London County Councilor, or a lover of literature, but simply and altogether as a patron of the turf. Meanwhile we were hearing of him every now and then as an adventurous yachtsman, and as the orator of some great commemoration day when a statue was unveiled to a Burke or a Burns.

A more delightful host than Lord Rosebery it would not be possible to meet or even to imagine. I have had the honor of enjoying his hospitality at Dalmeny and in his London home, and I shall only say that those were occasions which I may describe, in the words Carlyle employed with a less gladsome significance, as not easily to be forgotten in this world. No man can command a greater variety of topics of conversation. Politics, travel, art, letters, the life of great cities, the growth[61] of commerce, the tendencies of civilizations, the art of living, the philosophy of life, the way to enjoy life, the various characteristics of foreign capitals—on all such topics Lord Rosebery can speak with the clearness of one who knows his subject and the vivacity of one who can put his thoughts into the most expressive words. I suppose there must be some eminent authors with whose works Lord Rosebery is not familiar, but I can only say that if there be any such, I have not yet discovered who they are—and I have spent a good deal of my time in reading. I have seen Lord Rosebery in companies where painters and sculptors and the writers of books and the writers of plays formed the majority, where political subjects were not touched upon, and I have observed that Lord Rosebery could hold his own with each practitioner of art on the artist's special subject. Lord Rosebery does not profess to be a bookworm or a great scholar, but I do not know any man better acquainted with general literature. Such a man must surely have got out of life all the best that it has to give.

Yet it is certain that the eyes of expectation are still turned upon Lord Rosebery. There is a general conviction that he has something[62] yet to do—that, in fact, he has not yet given his measure. He has been Prime Minister, and he has been leader of the English Liberal party, but in neither case had he a chance of proving his strength. When Mr. Gladstone made up his mind to retire finally from political life, the Queen sent for Lord Rosebery and invited him to form an administration. Now, it is no secret that at that time there were men in the Liberal party whose friends and admirers believed that their length of service gave them a precedence of claims over the claims of Lord Rosebery. There were those who thought Sir William Harcourt had won for himself a right to be chosen as the successor to Mr. Gladstone. On the other side—for there was grumbling on both sides—there were members of the Liberal administration who positively declined to continue in office if Sir William Harcourt were made Prime Minister. These men did not object to serve under Sir William Harcourt as leader of the House of Commons, but they objected to his elevation to the supreme place of Prime Minister. Also, there were Liberals of great influence, who, while they had the fullest confidence in Lord Rosebery and were not fanatically devoted to Sir William Harcourt,[63] objected to the idea of having a Prime Minister in the House of Lords, and a Prime Minister, too, who had never sat in the House of Commons. Now, it would be idle to deny that there was some practical reason for this objection. The House of Commons is the field on which political battles are fought and won. The Commander-in-Chief ought always to be within reach. A whole plan of campaign may have to be changed at a quarter of an hour's notice. It must obviously often be highly inconvenient to have a Prime Minister who cannot cross the threshold of the House of Commons in order to get into instant communication with the leading men of his own party who are fighting the battle.

At all events, I am now only concerned to say that these doubts and difficulties and private disputations did arise, and that, although Lord Rosebery did accept the position of Prime Minister, he must have done so with some knowledge of the fact that certain of his colleagues were not quite satisfied with the new conditions. Lord Rosebery had been most successful as Foreign Secretary during each term when he held the office, but it was well known, before Mr. Gladstone's retirement, that there[64] were some questions of foreign policy on which the old leader and the new were not quite of one opinion. In English political life, and I suppose in the political life of every self-governing country, there are seasons of inevitable action and reaction which must be observed and felt, although they cannot always be explained.

To a distant observer the policy of the Liberal party might have seemed just the same after Mr. Gladstone had retired from politics as it was when he was in the front of political life. But just as the policy which sustained him in his early days as Prime Minister was helped by the reaction which had set in against the aggressive policy of Lord Palmerston, so there came, with the close of Gladstone's Parliamentary career, a kind of reaction against his counsel of peace and moderation. Lord Rosebery was believed to have more of what is called the Imperialist spirit in him than had ever guided the policy of his great leader. Certainly some of Mr. Gladstone's former colleagues in the House of Commons appear to have thought so, and there began to be signs of a growing division in the party. Lord Rosebery's Prime Ministership lasted but a short[65] time. The Government sustained one or two Parliamentary discomfitures, and there followed upon these a positive defeat in the nature of a sort of vote of censure carried by a small majority against a department of the administration, on the ground of an alleged insufficiency in some of the supplies of ammunition for military service. Many a Government would have professed to think little of such a defeat, would have treated it only as a mere question of departmental detail, and would have gone on as if nothing had happened. But Lord Rosebery refused to take things so coolly and so carelessly. Probably he was growing tired of his position under the peculiar circumstances. Perhaps he thought the most manly course he could take was to give the constituencies the opportunity of saying whether they were satisfied with his administration or were not. The Government appealed to the country. Parliament was dissolved, and a general election followed. Then was seen the full force of the reaction which had begun to set in against the Gladstone policy of peace, moderation, and justice. The Conservatives came into power by a large majority. Lord Rosebery was now merely the leader of the Liberal party in Opposition. Even this posi[66]tion he did not long retain. Some of the most brilliant speeches he ever made in the House of Lords were made during this time, but somehow people began to think that his heart was not in the leadership, and before long it was made known to the public that he had ceased to be the Liberal Commander-in-Chief.

Everybody, of course, was ready with an explanation as to this sudden act, and perhaps, as sometimes happens in such cases, the less a man really knew about the matter the more prompt he was with his explanation. Two reasons, however, were given by observers who appeared likely to know something of the real facts. One was that Lord Rosebery did not see his way to go as far as some of his colleagues would have gone in arousing the country to decided action against the Ottoman Government because of the manner in which it was allowing its Christian subjects to be treated. The other was that Lord Rosebery was too Imperialistic in spirit for such men as Sir William Harcourt and Mr. John Morley. No one could impugn Lord Rosebery's motives in either case. He might well have thought that too forward a movement against Turkey might only bring on a great European war or leave Eng[67]land isolated to carry out her policy at her own risk, and in the other case he may have thought that the policy bequeathed by Mr. Gladstone was tending to weaken the supremacy of England in South Africa.

Lord Rosebery then ceased to lead a Government or a party, and became for the time merely a member of the House of Lords. I do not suppose his leisure hung very heavy on his hands. I cannot imagine Lord Rosebery finding any difficulty in passing his day. The only difficulty I should think such a man must have is how to find time to give a fair chance to all the pursuits that are dear to him. Lord Rosebery spent some part of his leisure in yachting, gave his usual attention to the turf, was to be seen at picture galleries, and occasionally addressed great public meetings on important questions, and was a frequent visitor to the House of Commons during each session of Parliament. The peers have a space in the galleries of the House of Commons set apart for their own convenience, and, although that space can hold but a small number of the peers, yet on ordinary nights its benches are seldom fully occupied. But when some great debate is coming on, then the peers make a rush for[68] the gallery space in the House of Commons, and those who do not arrive in time to get a seat have to wait and take their chance, each in his turn, of any vacancy which may possibly occur. I am not a great admirer of the House of Lords as a legislative institution, and I must say that it has sometimes soothed the rancor of my jealous feelings as a humble Commoner to see a string of peers extending across the lobby of the House of Commons, each waiting for his chance of filling some sudden vacancy in the peers' gallery.

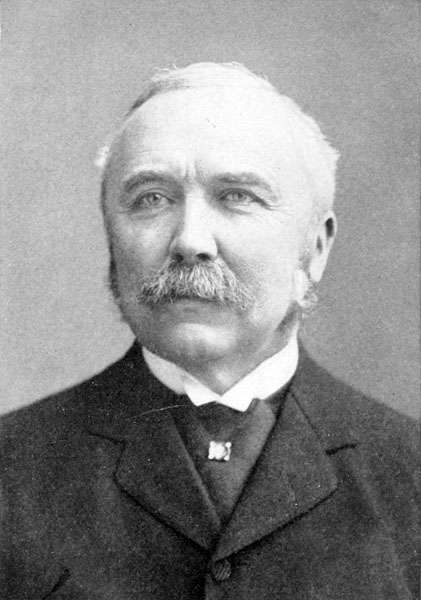

Lord Rosebery continued to attend the debates when he had ceased to be Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal party just as he had done before. His fine, clearly cut, closely shaven face, with features that a lady novelist of a past age would have called chiseled, and eyes lighted with an animation that seemed to have perpetual youth in it, were often objects of deep interest to the members of the House, and to the visitors in the strangers' galleries, and no doubt in the ladies' gallery as well. The appearance of Lord Rosebery in the peers' gallery was sure to excite some talk among the members of the House of Commons on the green benches below. We were always ready[69] to indulge in expectation and conjecture as to what Lord Rosebery was likely to do next, for there seemed to be a general consent of opinion that he was the last man in the world who could sit down and do nothing. But what was there left for him to do? He had held various administrative offices: he had twice been Foreign Secretary; he had twice been Chairman of the London County Council; he had been Prime Minister; he had been leader of the Liberal party; he had been President of all manner of great institutions; he had been President of the Social Science Congress; he had been Lord Rector of two great Universities; he had twice won the Derby. What was there left for him to do which human ambition in our times and in the dominions of Queen Victoria could care to accomplish? Yet the general impression seemed to be that Lord Rosebery had not yet done his appointed work, and that impression has grown deeper and stronger with recent events.