THE RIVAL SUBMARINES

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Rival Submarines

Author: Percy F. Westerman

Release Date: March 20, 2013 [EBook #40866]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RIVAL SUBMARINES ***

Produced by Al Haines.

THE RIVAL SUBMARINES

BY

PERCY F. WESTERMAN

AUTHOR OF "A LAD OF GRIT"

ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

C. FLEMING WILLIAMS

THIRD IMPRESSION

LONDON

S. W. PARTRIDGE & CO., LTD.

OLD BAILEY

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

THE RIVAL SUBMARINES.

CHAPTER I.

CAPTAIN RESTRONGUET LEAVES CARDS.

The garrison port of Portsmouth was mobilized. Not for the "real thing," be it understood, but for the quarterly practice laid down in the joint Naval and Military Regulations of 1917.

Everything, thanks to a rigid administration, had hitherto proceeded with the regularity of clockwork; the Army officials were patting themselves on the back, the Naval authorities were shaking hands with themselves, and, in order to cement the bond of unity, each of the two Services congratulated the other.

To the best of their belief they had reason to assert that Portsmouth was once more impregnable. A series of surprise torpedo-boat attacks upon the fortress had signally failed. The final test during the mobilization was to be in the form of a combined attack upon the defences by the battleships then lying at Spithead and the airships and aeroplanes stationed at Dover, Chatham, and Sheerness.

At eight o'clock on the morning of the day for the grand attack the fleet at Spithead prepared to get under way. Forty sinister-looking destroyers slipped out of harbour in double column line ahead, and as soon as they had passed the Nab Lightship a general signal was communicated by wireless for the battleships to weigh and proceed.

The Commander-in-Chief and the Admiral-Superintendent of Portsmouth Dockyard had breakfasted ashore on that particular morning, and both officers, with the Military Lieutenant-Governor of the Garrison, were to proceed to Spithead on a cruiser to witness the departure of the fleet. It was a fine day, but the beauties of the morning were lost upon them; to have to breakfast at an unearthly hour had considerably ruffled their tempers.

"Come along, Maynebrace," exclaimed the Commander-in-Chief irritably. "It's six bells already."

"Coxswain! Coxswain! Where in the name of thunder is my coxswain?" shouted Rear-Admiral Maynebrace.

"Here, sir!" exclaimed that worthy, saluting.

"Has the Lieutenant-Governor arrived yet, coxswain?"

"Yes, sir. The police at the Main Gate have just telephoned through to say that Sir John Ambrose has arrived, sir, but being rather late proceeded straight to the jetty."

"And kept us kicking our heels here," grumbled Sir Peter Garboard, the Commander-in-Chief. "Look alive, Maynebrace, or----"

At that moment a flag-lieutenant, red in the face and well-nigh breathless with running, dashed up the steps of the portico of the Admiralty House.

"Sir!" he exclaimed. "Sir, this message has just come through."

Sir Peter took the proffered envelope, fumbled with the flap with his flabby fingers, and at last untied the Gordian knot by tearing off one edge.

"Good heavens, Maynebrace!" he gasped. "Read this!"

The Admiral-Superintendent, with unbecoming haste, grasped the paper and read:--

"Vice-Admiral, First Battle Squadron, Home Fleet, to Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth. On fleet weighing anchor a painted board was found attached to the anchor of every battleship, the said board bearing the words 'With the compliments of Captain Restronguet.' Have ordered fleet to anchor again and am sending divers to investigate. Will communicate their report in due course."

All traces of irritability vanished from the faces of the two Admirals. Instinctively they realized that something of moment had taken place, and that instant action was necessary.

"A diver has been playing the fool, perhaps?" hazarded Maynebrace.

"Diver? Humph! Can you imagine a diver leaving his card, in the shape of a painted piece of wood, attached to the anchors of forty ships? No, no, Maynebrace, it's not that: at least, that's my opinion."

"Well, then, sir, what is it?" questioned the Rear-Admiral.

"A menace to our fleet, that's what it is. Although there is no real harm done the moral result is bad enough. It's my opinion that there's a foreign submarine at work. Moreover, she must have means of direct outside communication while she is submerged."

"What makes you think it is a foreign submarine?"

"Logic, my dear Maynebrace, logic. None of ours are capable of such a feat, and there's no knowing what these foreigners are up to. As inventors they are miles ahead of us. And what is more, the name--Restronguet--doesn't that sound French?"

"Perhaps," admitted the Rear-Admiral. "But all the same it is exasperating; it is humiliating. And there are some who think that the days of the submarine are over!"

Even as the introduction of ironclads propelled by steam machinery had revolutionized naval warfare in the middle of the nineteenth century, so had the vast strides in military aeronautics rendered obsolete, or nearly so, the huge battleships that were the chief features of the world's navies in the beginning of the present century. For several years a fierce war of controversy was waged between the supporters of an all-powerful navy and those who pinned their faith in vessels capable of supporting themselves in the air and able to use the terribly aggressive means that the researches of science could bestow.

Not only did the Great Powers take up the question. The lesser states of the world, realizing that a sudden revolution in warfare might place them on an equal basis with nations who had hitherto kept them in the background, took the liveliest interest in the discussion. They agreed that since the ill-advised building of the first British Dreadnought had given other Sea Powers a chance to build equally formidable vessels at the same rate of construction, and that in consequence the predominant Navy flying the White Ensign was practically out-of-date, a drastic and sudden revolution whereby a comparatively cheap means of offence could be created might also render obsolete the huge costly leviathans that even the richest nations could ill-afford to maintain in the race for naval supremacy.

In Great Britain the opinion of those qualified to judge was nearly equally divided. The Blue Water School maintained that a numerically superior fleet of ships, capable of defence against aircraft, would meet the case, provided a supplementary division of airships and aeroplanes was ready to act in conjunction with the squadron. Battleships could keep the sea in all weathers, while aircraft were at the mercy of every hurricane.

On the other hand the supporters of the air fleet deprecated the need of a huge navy--using the word navy in the strict sense of the term. All the warships that Great Britain had at her command could not prevent the passage by night of airships and aeroplanes--either singly or collectively--across the comparatively short distance between the Continent and the East Coast of England, while by a judicious study of the barometer and climatic conditions generally the dangers of being overtaken by a heavy gale could be reduced to a minimum. Besides, had there not been instances of foreign aircraft manoeuvring over the East Coast naval ports at night during the progress of a terrible equinoctial gale that had caused, amongst other disasters at sea, the loss of several destroyers taking a doubtful shelter in the badly-protected Admiralty Harbour at Dover?

Up to the present time the result of the controversy in Great Britain was a compromise. Instead of spending a couple of million pounds upon a single battleship of between forty or fifty thousand tons, smaller ships were laid down and completed within eleven months. They were not pleasing to the eye. Even the "ironclads," ugly in comparison with the stately "wooden walls" of the early nineteenth century, were models of symmetry and grace beside the latest creations from the brain of the Chief Constructor of the Navy.

The modern battleships were vessels of but ten thousand tons displacement, or about the same as the "Anson" class of 1886. Their draught was, however, considerably less, being but twenty-two feet when fully manned and ready for sea. They were propelled by internal combustion heavy oil engines capable of developing 22,000 horse-power, the maximum speed being forty-two knots. The principal armament consisted of twenty-four six-inch guns, that for muzzle velocity, range, penetration, and bursting power of the projectile were more than equal to the fifteen-inch gun mounted on the later Super-Dreadnoughts of the United States Navy. The weight saved in engines, armament, and especially by the absence of coal, was devoted to additional armour. The battleships were veritable steel-clad vessels, for not only were the sides completely encased in Harveyized steel, but the upper decks were surmounted by a V-shaped roof capable of resisting the most powerfully-charged shell that airships could possibly carry.

Nor was the protection for submarine attack left unprovided for. The whole of the under-water surface was armour-plated, not merely by one skin but by two complete layers of steel, the thickest being on the inside. In the double bottoms thus formed, oil, the food for the motors, was stored. A powerful torpedo might fracture the outer armoured skin and release the oil in that particular section, but having the thickest plating inside it was considered almost a matter of impossibility for the latter to be holed and thus admit the burning oil--a source of danger that had long been recognized--into the vitals of the ship.

Submarine warfare, in the opinion of many naval experts, had had its day. At the height of five hundred feet a scouting aeroplane could easily detect the presence of a submarine so long as it was daylight. By night a submarine would be fairly safe from observation, but conversely her commander could not with certainty attack a hostile ship that had taken the precaution of manoeuvring with screened lights. In addition to the danger of mistaking friend for foe there was also the possibility, nay probability, of being unable to see the enemy's ship. It was, however, admitted that the submarine's chance was to attack either at dawn or sunset, with a fairly choppy sea running, and no aircraft to upset the calculations of the officer at the periscope.

Nor had the vast changes occasioned by the development of aircraft been confined to naval affairs. Fortifications, hitherto considered impregnable, were rendered untenable by reason of the danger from attack from above; and in this respect the reorganization of the Portsmouth defences might be taken as an example of what had to be done in other naval and military towns of the British Isles.

As is well known Portsmouth, the principal naval arsenal of the British Empire, is defended by a triple line of fortifications; while to prevent subsidized tramp steamers from emulating Togo's feat at Port Arthur by being sunk at the entrance to the harbour a line of massive concrete blocks were placed from the shore to the east of Southsea Castle, extending seawards as far as to Horse Sand Fort--one of the three built upon the bottom of the sea. This form of defence was severely criticized, for it proved a source of danger to trading and other private ships, while at high tide a torpedo-boat could with impunity pass over the submerged artificial reef.

Consequently a permanent breakwater, fashioned after the manner of that superb work protecting Plymouth Sound, took the place of the worse than useless concrete blocks; a similar one was constructed from Ryde Sands to the Noman Fort, and thus, with the exception of the main channel between these two hitherto sea-girt forts, Spithead was rendered almost immune from torpedo-boat attacks.

These breakwaters, and indeed all the fortifications on shore, were armed with the latest type of air-craft repelling armament; a three-inch automatic gun, capable of firing one shell per second. The bursting charge of each shell was proved to have an effective radius of a hundred yards, while the creation of air-waves and "pockets" resulting from the detonation, would seriously imperil the stability of every aeroplane within three hundred yards. At night each of these guns was supplied by an ingeniously constructed searchlight that, projecting a narrow ray of light almost parallel with the axis of the gun-barrel, rendered a "miss" an impossibility unless the range was greatly miscalculated. As the sights of the weapon were altered the beam of the searchlight was automatically adjusted. All the gunlayer had to do was to train the searchlight upon the hostile aircraft and fire.

Yet in spite of all these elaborate means of defence the main portion of the British Navy, seemingly anchored in perfect security at Spithead, had received a most unpleasant moral blow. Who and what is this mysterious Captain Restronguet?

CHAPTER II.

SUB-LIEUTENANT HYTHE DISCOVERS THE SUBMARINE.

"Pipe away the diving-party!"

H.M.S. "Ramillies," the flagship of the First Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet, had just anchored in almost the identical position that she had occupied barely a quarter of an hour previously. With mathematical precision the other battleships of the squadron had also returned to their late anchorage and were preparing to investigate the mysterious occurrence in the shape of a complimentary message from the still more mysterious Captain Restronguet.

Up from below tumbled the diving-party. Air-pipes, life-lines, pumps, dresses, and helmets were produced from some remote yet properly apportioned part of the ship and were thrown down in a seemingly chaotic manner upon the steel deck. Actuated by electric power several sections of the armoured shields between the upper deck and the eaves of the V-shaped shell-proof roof were lowered till they lay flat upon the deck, and steel ladders for the divers' use were rapidly placed in position.

"Do you wish me to go down, sir?" asked a sub-lieutenant of the Number One.

"Certainly, Mr. Hythe," replied the first lieutenant. "Make a careful examination for a radius of say fifty yards from the shot-rope. You will doubtless be able to see the place where the flukes of our anchor held before. Ascertain if there are any traces of independent work; such as footprints in the ooze, tracks of the underbody of a submarine settling on the bottom, for example."

"Very good, sir," replied the sub, who, saluting, went off to be assisted into his diving-dress.

Sub-lieutenant Arnold Hythe was generally regarded as a smart and promising young officer. These golden opinions were gained not by self-advertisement, for the sub was unusually reticent concerning his profession, but by sheer hard work and a consistent application to that great deity that should always be before the eyes of all true subjects of the King--Duty.

He held a First-class certificate in Seamanship, Gunnery, and Engineering; a Second in Torpedo, and also in what the Navy List terms "Voluntary Subjects"; he was a qualified interpreter in French and German, and had more than a smattering of Spanish and Italian. In addition to these intellectual qualifications he possessed a powerful physique, and had a sound reputation as an all-round athlete whilst at Dartmouth.

The latter portion of his time as midshipman and the first few months after his promotion to sub-lieutenant were spent in duty with the Fifth Submarine Flotilla, whose base was at Fort Blockhouse at the entrance of Portsmouth Harbour. But through some cause, to him quite inexplicable, he had been appointed to the "Ramillies." This was somewhat to the sub's disgust, but realizing that it was of no use repining over such matters, Arnold Hythe accepted the change with cheerful alacrity.

Banks and Moy, the two seamen divers who were also to descend, were already dressed. All that remained was for their copper helmets to be donned, the telephones and air-tubes adjusted, and the glass fronts screwed on.

"I don't expect you will find any actual evidence, and it will be lucky if you come across any circumstantial evidence," remarked Mr. Watterley, the first lieutenant. "But in any case, should you see anything of a suspicious nature, inform us before proceeding to investigate. I need not remind you that the east-going tide is making, and that the current will be running fairly strong in a few minutes."

"Very good, sir."

Sub-lieutenant Hythe was a diver of considerable experience. Ever since his first descent in the training tank at Whale Island he took naturally to the hazardous duty. Going under the sea had a peculiar fascination for him, whether it was in the hull of a submarine or encased in the cumbersome india-rubber suit and ponderous helmet of the diver.

The men at the air-pumps began slowly to turn the handles. The glass front plates of the sub's helmet were secured, and assisted by a seaman Hythe staggered awkwardly towards the head of the iron ladder.

Rung by rung he descended till the water rose to his shoulders.

"By Jove, the tide does run," he muttered. "If it's like this now, what will it be in another ten minutes?"

Raising one arm he waved to those on deck, then releasing his hold he allowed himself to drop into the deep. The "Ramillies" was anchored in nine fathoms, but ere the sub reached bottom nearly a hundred and twenty feet of life-line and air-tube were paid out. With an effort he gained his footing and commenced to walk in the direction of the ship's anchor, battling against the two-knot current that swirled past him.

Although the sun was shining brightly and the light at that depth ought to be fairly strong, the sand and mud churned up by the tidal current made it impossible to see beyond a few yards. With nothing to guide him, for the life-line was quivering in the swirling water, Hythe struggled stolidly in the supposed direction. He realized that he was practically on a fool's errand. The mysterious person or agency who had been responsible for attaching the message to the anchors of the squadron was not likely to remain upon the scene of his exploit, while already all the sought-for traces must have been obliterated by the tide.

Presently two eerie-looking shapes ambled towards him. They were his companions, Banks and Moy.

"Well, if I am going in the wrong direction, those fellows are making the same mistake," thought the sub. "So here goes."

Another thirty yards were laboriously covered. Here and there the divers had to make a detour to avoid the wavy trailing masses of seaweed, that, if not actually dangerous, would seriously impede their progress, while at every few steps numbers of flatfish, barely discernible from the sand and mud in which they were partially buried, would dart off with the utmost rapidity.

"Thank goodness, here's the shot-line," exclaimed the sub, as a thin rope, magnified under water to the size of a man's wrist, became visible in the semi-gloom. The shot-line, terminating in a heavy piece of lead, had previously been lowered to serve as a guide for the divers to work from.

Pointing in two opposite directions Hythe signed to the two men to begin their investigations, while he, taking a route that lay at right angles to the others' course, began once more to struggle against the current. Ere he had traversed another ten yards his feet slipped into a slight depression. It was the hole scooped out by the flukes of the "Ramillies'" stockless anchor.

"Could do with a lamp," he remarked to himself, then stooping he began to examine the bed of mud and sand in which he stood. Beyond the almost filled-in cavity and the faint traces of the sweep of the battleship's anchor-chain there was nothing to attract his attention. He turned to look at his own footprints. They were already practically obliterated, so it was hopeless to expect to find the footprints of the mysterious diver or divers who had contrived to visit each of the anchors of the battleships in turn.

"Anything to report?" asked a voice through the telephone.

"No, sir," replied the sub.

"Thought as much," said Watterley. "Merely a matter of form. You may as well come up. I'll recall the two men."

Sub-Lieutenant Hythe was not sorry to hear the order to return. Had there been any possibility of success he would have prosecuted his investigations with alacrity, but Spithead with an east-going spring tide running is no place to indulge in submarine excursions. The danger of getting life-line and air-tube foul of some unseen obstruction was no slight one.

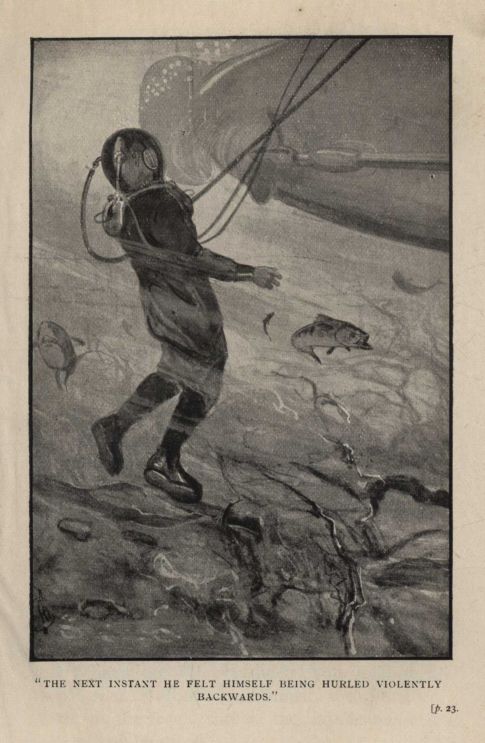

Hythe adjusted the valve of his helmet prior to giving the recognized number of tugs on the life-line--the signal to be hauled up. The next instant he felt himself being hurled violently backwards by a sudden and irresistible swirl of water. Within ten feet of him a huge, ill-defined mass of what appeared to be bright metal tore past. He was just conscious of a vision of one of a pair of propellers thrashing the muddy water and the object was lost to view.

"What a narrow squeak!" he growled angrily. "By Jove, I shouldn't be surprised if Banks is done for. It's a submarine, that I'll swear, but not one of ours. Ours are painted a dull grey and that seems to be a huge moving mirror."

In spite of his strong nerves, a mild panic overtook the sub. He signalled frantically to be drawn up, and to his relief he found himself alongside the battleship.

Grasping a line that was thrown him, Hythe hauled himself along till he reached the iron ladder. Here he clung, too excited to attempt to climb, until a seaman descended and assisted him up the side.

"What's up, Mr. Hythe? You look as if you'd seen a ghost," exclaimed the Number One, as the front plate of the sub-lieutenant's helmet was removed.

"Are Banks and Moy safe?" gasped the young officer.

"Safe? Of course they are," replied Lieutenant Watterley, giving a hasty glance over the side to where two distinct clusters of air-bubbles marked the progress of the divers. "What have you seen? But no, say nothing more at present. Wait till you're out of your dress, and you can report to the captain."

Arnold Hythe sat down on a bollard and attempted to collect his scattered thoughts, while his attendant proceeded to remove his helmet and leaden weights. Ere his india-rubber dress was stripped off Banks and Moy appeared over the side.

"Well?" demanded the first lieutenant laconically.

"Nothin' to report, sir," replied Banks, while his companion signified corroboration by a nod of his head.

Mr. Watterley looked inquiringly at the sub. The flush upon his face had vanished and his features were white with excitement. Several of the officers had come up and were engaged in plying Hythe with questions, to which the latter paid no attention. He was still in a kind of stupor, the result of a sudden shock to his nerves.

"Now then, Mr. Hythe--why, what's the matter with you? Here, I must send for the staff-surgeon; I must, by George!"

Assisted by two of his brother officers the sub was taken below, and in a very short space of time Doctor Hamworthy succeeded in bringing him to a more normal state.

Meanwhile Admiral Hobbes, hardly able to conceal his impatience beneath a cloak of official reserve, was engaged in animated conversation with Captain Warborough upon the eventful incidents that had necessitated the return of the Fleet to Spithead.

"Commander-in-Chief coming off, sir!" reported the lieutenant of the watch.

Tearing as hard as her sixty horse-power motors could drive her the Admiral's pinnace containing the Commander-in-Chief, the Admiral-Superintendent of the Dockyard, and the military Governor of the Fortress headed towards the "Ramillies."

Received with due ceremony and formality the officials came over the side, and on being welcomed by Vice-Admiral Hobbes were taken below to the latter's cabin.

"Well, Hobbes, what do you make of this business, eh?" asked Sir Peter Garboard. "Have you taken any steps to investigate?"

"Sent three divers down," replied the Vice-Admiral. "I am even now awaiting their report."

"Then the sooner the better," rejoined the Commander-in-Chief.

Admiral Hobbes touched a bell and a marine orderly entered the cabin.

"Pass the word for Mr. Watterley."

The marine orderly saluted and doubled along the half-deck, nearly bowling over the staff-surgeon and the first lieutenant who were already on their way to make their report to the captain.

"What's this? Mr. Hythe frightened by something he saw beneath the surface?" demanded Vice-Admiral Hobbes.

"No, sir," replied Doctor Hamworthy. "He is suffering from a shock to the nervous system; the symptoms are almost identical with those resulting from a severe electric shock."

"You don't mean to say that Mr. Hythe is the victim of a submarine discharge?"

"I do not assert, sir; I merely stated my opinion based upon observations."

"And how is he now?" asked the Vice-Admiral impatiently.

"Fairly fit; he could be judiciously cross-examined," replied the staff-surgeon. "But, unless absolutely necessary----"

"It is absolutely necessary," interposed Admiral Hobbes; then turning to the first lieutenant he continued:--

"And what were the other men doing? I understand that there were two seamen sent down. Were they injured?"

"They saw nothing unusual, sir," replied Mr. Watterley. "I subjected them to a strict examination. They walked in opposite directions from the shot-rope, athwart the tide, while Mr. Hythe went dead against the current. The water was very muddy. The men said they could see about ten yards in front of them. Banks, after the question was repeated, said he fancied he felt a cross-current that might have been the following-wave of a submerged vessel moving at high speed----"

"By the by," interposed Sir Peter Garboard. "I suppose you ascertained that none of our submarine flotilla were manoeuvring at Spithead?"

"Oh, no, sir; or rather, I mean yes, sir," replied the harassed lieutenant. "We signalled to Fort Blockhouse and in reply were informed that F 1, 3, 7, and 9 of the 2nd Flotilla went out at 7 this morning for exercise off the Nab. Those were the only submarines under way from this port. I also asked them to communicate with the Submarine Depots at Devonport, Dover, Sheerness, Harwich----"

"I hope you didn't give the reason, by Jove!" exclaimed Sir Peter vehemently. "If the papers get hold of the news there'll be a pretty rumpus."

"I shouldn't be surprised if the Press hasn't received more information than we have," remarked Rear-Admiral Maynebrace. "It passes my comprehension how they manage it. One thing, it's no use trying to hush the matter up. We cannot expect to muzzle nearly five thousand men."

"Wish to goodness I could!" snapped Sir Peter. Then addressing Mr. Watterley, he added: "Oh, first lieutenant, will you please send for Mr. Hythe, so that we can hear his version of the business."

Five minutes later Sub-Lieutenant Hythe was shown into the Admiral's cabin. The young officer was still pale. His iron nerves had received a severe shock, but thanks to Doctor Hamworthy's attentions he was able to pull himself together sufficiently to give a fairly full account of what had occurred.

"How would you describe the submarine that passed so close to you?" asked Captain Warborough.

"She was quite unlike any of our types, sir. I noticed she was almost wall-sided, with a very flat floor. Instead of tapering to a point fore and aft she had a straight stem and, I believe, a rounded stern, cut away so as to protect the propellers."

"How many propellers?"

"Two, I think, sir. I distinctly saw the starboard one revolving. The eddy from it prevented my seeing anything more."

"H'm. By the by, had she a conning-tower?"

"I could not see, sir. Her upper deck must have been quite twelve feet above my head."

"What colour was she painted?"

"That, sir, I can hardly describe. I can only liken the sides to a huge mirror that reflected objects without reflecting the sunlight at the same time. As it was I could only see that portion of her that passed immediately in front of me. I could not even give an estimate as to her length, or even the speed at which she was travelling."

"You were capsized, I believe. Did anything strike you?"

"An under-water wave, sir, hurled me backwards. Nothing actually struck me, but I felt a strange paralysing sensation in my limbs, so that I could not make my way back to the shot-rope. All I could do was to signal to be hauled up."

"Then how do you account for the fact that this submarine craft passed close to you, and yet was unseen by Banks who was farther from the ship than you were?"

"I regret, sir, I cannot hazard an opinion," replied the sub.

"That will do, Mr. Hythe," said the Commander-in-Chief, indicating that the interview was at an end.

"Oh, by the way, Doctor," he continued, after the sub had left the cabin, "I suppose you have no doubt that this young officer actually did see this submarine? Is it possible that he was the victim of a hallucination?"

"From Mr. Hythe's medical sheet, and from my personal knowledge of his physical and mental condition, I have every reason to reply in the negative to both your questions, sir."

"Well, well, gentlemen," exclaimed Sir Peter, "we have a great task in front of us, with very little data to work upon. We have reason to suppose that there is a mysterious submarine commanded by an equally mysterious Captain Restronguet--a name that suggests that the fellow is French. We have definite evidence that by some unknown means that Captain Restronguet is able to execute extensive and fairly intricate work, namely, fixing those painted boards to the fluke of the anchors of the Fleet. How it was done has to be proved, and it must be proved up to the hilt, for even though no hostile act has been committed it is quite evident that the ships at Spithead were quite at the mercy of this unknown submarine. As far as the safety of the Fleet at Spithead is concerned, you, my dear Hobbes, are responsible. I, for my part, must take due precautions to prevent this submarine from entering the harbour, and I venture to assert, gentlemen, that when our preparations are complete, this Captain Restronguet and his submarine will be neatly trapped."

CHAPTER III.

THE MAN WHO WALKED OUT OF THE SEA.

Before night the news of the event that caused the manoeuvres to be hurriedly abandoned had been published in the papers. Most of the journals contented themselves with a brief account of what had transpired, based upon reports that had been obtained from men serving in the Fleet; for although liberty men were not landed communication with the shore had to be maintained. Other papers enlarged on the actual facts, and announced in double-leaded columns that a foreign submarine had attempted to fix mines to the hulls of the ships at Spithead.

Never had there been such conjectures since the time when some years previously an airship of unknown nationality had sailed over Chatham and Sheerness. People asked what was the use of making elaborate defences against aircraft when a submarine could unseen enter the most strongly fortified roadstead in the world and coolly tamper with the moorings of the Fleet?

Meanwhile the Naval authorities at Portsmouth, who regarded Captain Restronguet's visit as a slur upon their capabilities, lost no time in prosecuting their investigations. A stupendous obstruction, formed of several old torpedo nets fastened together, was thrown across the Needles Channel between Cliff End Fort in the Isle of Wight and Hurst Castle on the Hampshire shore; while a similar defence net was placed between the seaward extremities of the two new breakwaters on the eastern side of Spithead. All homeward bound shipping was forbidden to make for any of the ports within these obstructions, while an embargo was placed upon all merchant vessels about to leave Southampton, Portsmouth and Cowes, and their outlying ports. It was a drastic order, and quite unnecessary, but the country was almost in a state of panic.

Into the enclosed area every available trawler suitable for mine-sweeping, as well as all the dockyard hopper-barges fitted with appliances for "creeping" were kept busily at work, till hardly a square yard of the bottom of the Solent was left unexplored, and not until this particular work was completed did the authorities agree that the mysterious submarine might have left these waters almost as soon as Captain Restronguet had left his new-fangled cards upon the officers commanding H.M. ships at Spithead.

While these dragging operations were in progress the force of the tide through the Needles Channel, which often exceeds seven knots, tore away the nets thrown across that passage. Two days later the easternmost netdefence was removed, and it was then found that a rent thirty feet in length had been made in the steel meshes. Whether this was done by human or natural agency could not be determined, a minute examination of the fracture ending in nothing but heated arguments between the experts who had been called in to make a report.

On the same day that the torpedo net defences were removed the master of SS. "Barberton Castle" reported sighting two submarines lying motionless on the water, about fifteen miles S.S.E. of the Lizard. He stated that owing to the submarines being against the light he was unable to see them at all distinctly, yet he felt certain that they were of a totally different type from those of the British and French navies. They were so close together that the bows of one overlapped the quarters of the other, and thinking that they were in distress, he ordered the "Barberton Castle's" head to be turned in their direction. Directly the tramp answered to her helm both submarines dived simultaneously, and were lost to view.

The next morning Reuter's published a telegram from their agent at Cherbourg, announcing that the mysterious Captain Restronguet had brought his submarine into the harbour and at high tide had placed three dummy mines at the entrance to the docks in the naval arsenal. To each of the mines was a tablet on which was painted "Avec les assurances de ma plus parfaite consideration--Restronguet, capitan de sous-marin."

With the fall of the tide, that here exceeds twenty feet, these disquieting evidences were discovered, and within a few hours Captain Restronguet was the talk of all the cafés of Paris. The French, pioneers in submarine warfare, were now at a loss to explain how a submerged craft could, in broad daylight, enter the breakwater-enclosed harbour and run alongside the caissons of the docks without being discovered, while to deposit three bulky "mines" in water of not more than three fathoms in depth was an exploit that required a lot of explanation as to how it was done.

The transference of Captain Restronguet's attentions to the other side of the Channel relaxed the tension on the British shore. But, bearing in mind that Cherbourg is only a few hours' distance from Portsmouth, the naval authorities at the latter port were still on tenter-hooks.

A week passed. The First Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet still remained at Spithead, although under orders to proceed to the Nore at an early date.

At 11.15 one morning a startling incident occurred that, rightly or wrongly, was attributed in some manner to Captain Restronguet.

It was on Southsea beach, almost midway between the pier and the castle. The beach and parade were thronged with people, mostly visitors who had taken advantage of the Fleet's presence to enjoy the view of the ships. The sea was perfectly smooth, being unruffled by the light off-shore breeze; the tide was, however, running very strongly, for it was about the fourth hour of the ebb.

Suddenly a succession of shrieks from a group of children paddling in the water attracted the attention of persons in the vicinity, and to the astonishment of every one the head and shoulders of a man encased in a dull green metal helmet emerged from the waves.

For a few moments the man hesitated, then staggered out of the water. At the edge of the beach he sat down and began to remove his head-dress, that the onlookers noticed was unprovided with air-tube or life-line. He was apparently quite independent of an outside air-supply.

Surprise had hitherto kept the spectators at a respectful distance, although their numbers were momentarily increased by others, until a deep semicircle of gaping onlookers hedged the diver in on the landward side. But as soon as he began to take off his helmet the crowd swayed nearer and nearer.

The removal of the metal head-dress revealed the features of a man of about thirty years of age, clean-shaven and with closely-cropped dark-brown hair that had a tendency to curl. Without speaking a word the unknown drew a knife from his belt and began to hack rapidly at some contrivance at the back of his helmet. As soon as he had severed the part he was attacking he stood up and hurled it far into the sea. This done he calmly began to strip off the stiff fabric that composed his diving suit.

By this time the coastguard on duty at the look-out hut had noticed the crowd congregate, and through his glass saw that something unusual was happening and that a diver had come ashore. Since there were no Government diving boats anywhere in sight he naturally thought that it was a case for investigation, and the detachment of coastguards was promptly turned out.

"Here, sir, what's the meaning of this?" demanded the chief officer, forcing his way through the crowd. "Who are you, and how did you manage to get ashore here?"

"That I can easily explain," replied the unknown. "I am an inventor, and this diving-dress represents the result of seven years' work. I walked into the sea at Gosport a couple of hours ago, but, getting caught in the strong current running out of Portsmouth Harbour, I was swept a great distance until I managed to regain my feet. By walking in a direction due north as shown by my watertight compass I came ashore here. Needless to say I do not look for publicity, and all I wish is to pack up my discarded gear and go."

The chief officer looked at the stranger with mingled astonishment, admiration, and doubt. Never before had he known of a diver covering a distance of more than two miles, and that without the assistance of a boat containing the necessary apparatus for supplying the submerged man with air.

"Hanged if I know what to make of it, Smithers!" he said in an aside to his leading petty officer. "Perhaps he's a spy, or one of that blooming Captain Restronguet's crowd. This beats all creation!"

"Can't we detain him on suspicion?" asked Smithers. "I'll swear he's up to no good."

"I've half a mind to," replied the chief officer dubiously. "But, you see, they'll come down on me like a hundred of bricks if I exceed my duty."

"Invite him to the station, friendly-like," suggested the petty officer, "then, while he's there, you can telephone for instructions."

"I'll try it, by smoke!" ejaculated the chief officer, and approaching the unknown he asked if he would like to dry his clothes at the coast-guard station, since his ordinary garments, owing to the exertion in a confined space, were dripping with moisture.

"No, thank you," replied the submarine pedestrian. "All I want is to get a taxi, and make myself scarce. The attentions of so large a crowd are really embarrassing, and I am a man of a very retiring disposition. Had I expected this reception I should have vastly preferred to have landed in a more secluded spot."

With that he ignored his questioners and began to roll his diving suit into as small a compass as possible.

The coastguards were on the horns of a dilemma. They feared to make an unlawful arrest, while they might be severely brought to book for allowing the stranger to slip through their fingers, but there was nothing in the King's Regulations to prevent a man landing on a public beach, whether from a boat, hydro-aeroplane, or otherwise.

Just at that instant a policeman strolled leisurely up, and scenting a charge, produced his notebook and pencil.

"Hi! What's this you're up to?" he demanded, but the unknown totally ignored him.

"Can't he speak English?" asked the policeman of the coastguard officer.

"Rather," asserted the other emphatically; then in a lower tone he added, "Look here, we want to detain the man, but we cannot name a charge."

"I'll see about that," retorted the policeman. "Now, sir, your name and address, please."

"Allow me to inform you, constable, that my name is not 'Hi.' Since you addressed me as such you must not be surprised that your question was ignored."

A titter went up from the crowd, which had the effect of rousing the ire of the representative of the Law.

"Now, sir, your name and address, please."

"What for, constable?"

"For bathing off a public beach in prohibited hours."

"Don't talk rot!" exclaimed the unknown indignantly.

"Very good; since you refuse I have no option--I arrest you. Any statement you make may be used as evidence against you. Come along with me."

Attended by the surging crowd the policeman escorted his charge to the road, where a cab was hailed. The chief officer of coastguards was requested to accompany the prisoner as a witness, and the three entered the vehicle and were driven to the police-station.

Here, in order to gain time, the prisoner was formally charged with unlawful bathing, and as the Court was still sitting at the Town Hall he was ordered to be taken there at once. The chief officer meanwhile communicated with the naval authorities by telephone, expressing his opinion that the diver was a member of the mysterious Captain Restronguet's submarine.

But the prisoner never arrived at the Town Hall. When the cab stopped outside the court a policeman was found insensible on the seat. The floor had been violently ripped up, and unknown to the driver and the constable on the box the suspect had got clean away. By some inexplicable agency the unknown had deprived his captor of his senses, and the mystery of Captain Restronguet had entered into another phase.

CHAPTER IV.

THE SIGNAL FROM THE DEPTHS.

"Naval appointments: The following appointment was made at the Admiralty this afternoon: Sub-Lieutenant Arnold Hythe to the 'Investigator' for special duties (undated)."

This item, in the Stop-Press columns of an evening paper, was shown to Sub-Lieutenant Hythe by one of his brother officers.

"You are a lucky dog!" exclaimed the latter. "My Lords evidently recognize your capabilities as a diver. Well, good luck, old man. I hope you'll play the chief part in running down this plaguey fellow. Hang it all, I cannot see that he's doing any harm, except that all leave is stopped until something is done to stop his little antics."

"Yes, that is hard lines," assented the sub. "But I'll do my level best, no doubt."

H.M. surveying vessel "Investigator" was lying in dock at Portsmouth, and was under orders to proceed to sea at the first possible opportunity, her errand being to endeavour to locate and capture the submarine that, it was generally agreed, was still in the vicinity of Spithead.

To cope with the situation a special Bill had been hurriedly introduced into Parliament making it an offence against the Naval Secrets Act for any person to manoeuvre a private submarine within five miles of specified naval ports. The Bill received the Royal assent and became law within thirty-six hours after the escape of the suspect arrest on Southsea beach, an individual who was generally accepted as being the man of mystery, Captain Restronguet.

The fellow's diving gear, or at any rate the major portion of it, remained in the hands of the authorities. After being subjected to a lengthy research at the hands of the Diving School at Whale Island the following report was issued confidentially: "The helmet is of a metal hitherto unknown, possessing all the advantages of aluminium, without the known disadvantages. It is a departure from the usual form, having a ridge-shaped projection in front, possibly to lessen the resistance to the water when moving on the bottom of the sea. The helmet is also valveless, the air, chemically prepared, is by some means kept at a fairly high pressure, sufficient to distend the suit in order to do away with any discomfort to the wearer by reason of the weight of water. The suit is made, not of rubber as was at first supposed, but of an unknown quality of flexible metal. When distended it also presents an edge in front, in order to minimize lateral resistance. How the air is purified is still a secret, the apparatus for so doing having been detached and thrown into the sea by the unknown. A diligent search had failed to produce this important item. Undoubtedly the suit, when complete, is far in advance of any now used in the Service."

A careful watch was maintained along the shore, the coastguards stationed in the district being temporarily augmented by men drafted from more remote places. Yet no trace of the mysterious submarine on the surface was to be seen. How, when and where the craft replenished her fuel necessary for locomotion purposes and her provisions and fresh water completely baffled the naval experts; for a fortnight had elapsed since she announced her appearance at Spithead, and save for the temporary visit to Cherbourg all evidence pointed to the fact that she was still within the limits of the Port of Portsmouth.

Arnold Hythe duly joined the "Investigator" as officer in charge of the diving parties. Twelve first-class seamen-divers were drafted into the ship, while special gear for "creeping" was placed on board. Submarine apparatus for recording by sound the presence of submerged craft under way was also installed, so that it was impossible for any vessel making the faintest noise to approach within two miles of the "Investigator." Even the wavelets lapping the bows of a passing fishing-smack would be reproduced with unerring fidelity. Just before high water the "Investigator" was undocked; steam was soon raised, for the surveying vessel, being of an old type, was driven by reciprocating engines and oil-fed boilers. Almost at the moment of casting off the hawsers and springs came news that caused the greatest disappointment amongst officers and crew.

Captain Restronguet had, according to the latest report, turned up in a totally different spot. This time he devoted his attention to the German port of Wilhelmshaven. Here his visit was not of a comparatively harmless nature, for the locks of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal were totally demolished by means of a powerful explosive. The battleship, "Karl Adelbert," that was about to pass out of the canal, was badly damaged. In the confusion six destroyers and submarines were ordered from Cuxhaven. They were quickly on the spot, but no trace of the mysterious submarine was to be seen, except a small barrel painted white and green, with the name "Captain Restronguet" in bold letters.

The "Investigator" was immediately ordered to make fast one of the buoys in Portsmouth harbour. Her special mission was, for the time being at least, over; a far more serious situation had arisen.

The German Government, supported almost entirely by the Press of that country, actually suggested that, since Captain Restronguet had committed an act of piracy against the German Fleet while he had refrained from so doing on his visit to Portsmouth and Cherbourg, Great Britain and France were secretly aware of the identity of this modern buccaneer, and that they had encouraged him to make an unlawful act of hostility towards a friendly Power.

Three army corps were hastily ordered to Hanover and Schleswig-Holstein, the German High Sea Fleet was ordered to assemble at a rendezvous off Heligoland, and every available battleship, cruiser, destroyer and submarine in the Baltic was sent through the Great Belt and around the Skaw to augment the naval armament already in the North Sea.

The British Government met the situation with promptitude, firmness, and calmness. The First and Second Home Fleets settled at the Nore; the Third Home Fleet, which happened to be cruising off the Orkneys, was ordered to the Firth of Forth. Troops were quickly entrained at Aldershot and Salisbury Plain for the defence of the East Coast, while the Territorial Army and the National Reserve were called up for garrison duty. At the same time a statement was made to the German Ambassador in London in which His Majesty's Government totally repudiated the suggestions that Captain Restronguet held any authority, either direct or indirect, from the Crown.

To this the German Press retorted by pronouncing the declaration to be a diplomatic lie, and unanimously urged the Imperial Government to recall its ambassador. All privately owned airships in the Fatherland were taken possession of by the authorities, and ordered to the newly-formed Government aerodrome at Munster, a Westphalian town sufficiently far from the sea to be out of the reach of the guns of hostile warships, yet within a few hours' flying distance from the East Coast of England.

The struggle, if it came off, would be a desperate one. Both fleets were almost numerically equal, the British having a slight margin of superiority, but in aircraft the Germans held a decided advantage. In the science of warfare there was little to choose between the two, so that as far as Great Britain was concerned the issue depended upon whether the British tars still retained their bull-dog tenacity that characterized their forefathers in the days of the old wooden walls.

In spite of the British Government's coolness and determination the country, that had passed through so many international complications with safety, was in a panic. Consols dropped lower than ever they had been known to fall; prices immediately rose with a bound, and within twelve hours of the receipt of the disquieting news of Captain Restronguet's escapade at Wilhelmshaven the country was experiencing the horrors of war without actually being engaged in a desperate conflict on which her very existence depended.

On the morning following the momentous news from Wilhelmshaven a message appeared in The Times. It was a statement purporting to come from Captain Restronguet, in which he emphatically denied ever being in German waters, and that as a proof he would give a sure sign of his presence off the shores of Great Britain. At noon of that very day he would give a demonstration of the irresistible powers at his command at a spot somewhere between the Horse Sand Fort and the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour.

"Do you think it is a joke, sir?" asked Sub-Lieutenant Hythe of the navigating officer of the "Investigator."

"What do you think of it, may I ask?" replied Lieutenant Egmont guardedly.

"Personally, I hardly consider that it is a hoax. You see the notice appeared in the Personal Column."

"And paid for in the usual manner, I suppose."

"But the Business Editor has the option of refusing any advertisement."

"That's what makes me think there's something genuine about it. Again, the paper has a short leader on it: non-committal, it is true."

"But how can a fellow cooped up in a submarine that is being watched for all along the coast contrive to get ashore to send off a message to The Times?" asked Egmont. "How can he keep in touch with affairs? Why, in order to have that notice inserted he must have heard of the Wilhelmshaven business within an hour or so of its occurrence."

"Admitted; but all the same Captain Restronguet is a modern magician in submarine work. I should not be surprised if he has a perfect wireless service at his command. By the by, has Captain Tarfag orders to proceed to Spithead?"

"No, and he told me himself that he didn't want to be sent on a wild-goose chase. The Admiral has ordered a couple of aero-hydroplanes to manoeuvre over the place indicated at noon, and to keep a sharp look-out for any suspicious object under the surface. There they are, by Jove!"

Both officers stopped in their "constitutional," a to and fro promenade of the short quarterdeck of the "Investigator." A dull hum, momentarily growing louder, announced that Nos. 27 and 29 Aero-hydroplanes had left their sheds on the shores of Fareham Creek and were rising rapidly to the height of one thousand feet.

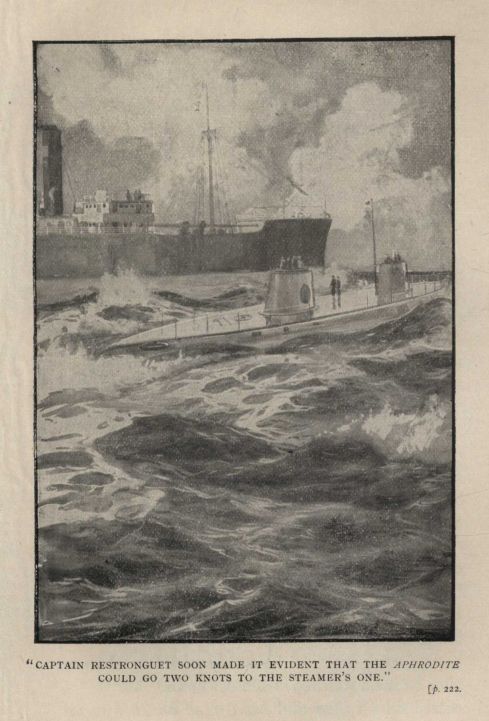

As soon as this altitude was reached both aero-hydroplanes, abandoning their spiral motion, leapt forward, and passing high above the shipping in the harbour were soon mere specks floating in the blue sky.

Watch in hand the sub waited. It was close on the fateful hour of noon. To and fro, in elliptical curves, the aero-hydroplanes maintained their lofty vigil, each turning at almost the same moment and passing within fifty yards of one another.

Twelve o'clock! Hythe and his brother officer exchanged glances. Captain Tarfag ascended the bridge, and hailing the wireless operator and the yeoman of signals by telephone, demanded if either of them had received news of the mysterious submarine.

"No message has been received at the Semaphore Tower, sir," they replied. The captain gave a deprecating shrug and descended the ladder.

"They're coming back, by Jove!" exclaimed Lieutenant Egmont, after another ten minutes had elapsed. "That proves that the message was a hoax."

"They may have seen something," suggested the sub, unwilling to have his opinions shattered.

"Not they. Do you mean to tell me that if they had spotted anything suspicious they would not follow it up. I was----"

The navigating officer's words were interrupted by a heavy detonation, like the report of a fourteen-inch gun fired with a full charge. Beyond the houses of Old Portsmouth, and at an altitude of about five hundred feet, a cloud of yellow smoke hung almost motionless in the still air. The aero-hydroplanes, overtaken by a wave of disturbed atmosphere, lurched violently, although fully a mile from the actual place of the explosion. It required all the efforts at the command of their crew to save the aerial vessels from destruction, but recovering their equilibrium by superb manoeuvring of the planes, the aero-hydroplanes turned and headed towards that portion of Spithead over which they had so lately been reconnoitring.

"By Jove! There's pluck for you!" ejaculated Egmont. "That was Restronguet's signal. If it had been to time those fellows would have been done for; and now they're trying to spot the submarine. You were right after all, Hythe. That paragraph was not a hoax."

Captain Tarfag was in the middle of lunch when the detonation was heard. He rushed on deck, and realizing that it was a case where waiting for orders would be detrimental to success, he ordered the moorings to be slipped.

Within the harbour all was commotion. Nearly a dozen destroyers, two scouts, and three tugs were making for Spithead, while five more aero-hydroplanes and the naval airship "Beresford" were ploughing their way against a stiff south-easterly breeze towards the scene of Captain Restronguet's latest demonstration.

One noticeable result of the explosion was that within a quarter of an hour the weather, hitherto perfectly calm, became changed. Clouds were rapidly banking up, with every appearance of a heavy thunderstorm, while the placid waters of Spithead were now white with foam-crested waves.

For two hours the "Investigator" and her consorts cruised up and down, betwixt the Nab Lightship to the eastward and Cowes to the west. Aloft the aircraft kept anxious watch and ward, till it seemed impossible that any craft could lie at the bottom of that comparatively shallow roadstead without being discovered.

"Nothing to report," came the wireless message from the aircraft with monotonous regularity. Captain Restronguet had outwitted the eyes and ears of the British Fleet.

Upon the "Investigator's" return to Portsmouth Harbour it was possible to obtain details of what had occurred: The sea wall in front of Southsea Castle was crowded with people who, half-doubting, were yet sufficiently curious to see whether the promise in The Times would be redeemed. They saw the two aero-hydroplanes approach and manoeuvre over the pre-arranged area. They heard the clocks chime the hour of twelve. They waited a few moments longer, nothing happened, so with a derisive cheer they began to disperse. Some remained--mostly those of the leisured class who were not restricted by the midday meal that the British workman holds up as an established institution.

Suddenly--it was exactly at eleven minutes past twelve--a column of water leapt vertically upwards at less than four hundred yards from the shore. There was a shrieking sound like the screech of a high velocity projectile, followed by a detonation so powerful that most of the spectators on the sea-front were deaf for days afterwards. The ground trembled, several persons were overthrown; the windows of several houses overlooking the common were broken. Expecting a shower of scraps of metal from the bursting projectile the terror-stricken crowd broke and ran, but curiously enough no one could afterwards be found to report that anything of a solid nature fell to earth. Captain Restronguet's token was merely an explosive rocket of high power.

That same afternoon news came that a German seagoing training-ship, the "Sachsen" was sunk by some unknown means in Kiel Harbour, and another green and white buoy bearing Captain Restronguet's name, was found floating over the wreck of the sunken vessel.

By what manner, incomprehensible beyond the wildest dream of fiction, could this Captain Restronguet be at Portsmouth just after noon and at Kiel, in the Baltic Sea, two hours later? Was his submarine in possession of supernatural powers whereby he could annihilate space and practically conquer time? The theory was no sooner advanced than it was regarded as utterly impossible; the opinion that Captain Restronguet was, after all, not responsible for the outrages at Wilhelmshaven began to gain ground both in Great Britain and Germany.

In naval and military circles the importance of the offensive powers of the mysterious submarine were fully commented upon. It was recognized that submarine warfare was more than likely to regain the supremacy that had been wrested from it by aircraft. Here was a submerged vessel, invisible although only in seven fathoms of water, that could project a shell charged with a high explosive vertically to a great height. Although not in the accepted sense of the word an aerial torpedo, the rocket had seriously affected the stability of the two aero-hydroplanes that were at a distance hitherto considered as a safe margin. Had it been an aerial torpedo instead of a rocket the result would have been terrible to contemplate.

The Chronicle appeared next morning with an apology and manifesto from Captain Restronguet. He regretted that, owing to the proximity of the two aero-hydroplanes, he was not able to give his promised token precisely at the hour of twelve, and trusted that the British public would realize that the slight delay was due solely to his desire to avoid loss of life and property to His Majesty's subjects. He once more repudiated any suggestion that the Kiel outrage was carried out at his instigation, and, further, as a proof of good faith, he hoped to give an exhibition of the forces at his command this time in Plymouth Sound. At 6 a.m. on the following day, unless unforeseen circumstances prevented, he would make known his presence in Cawsand Bay.

As soon as this decision was communicated to the Admiralty telegraphic orders were sent to Portsmouth, ordering the "Investigator" to proceed at once to Plymouth, where, co-operating with the surveying-vessel "Mudlark," she was to make every effort to effect the capture of Captain Restronguet's submersible ship.

CHAPTER V.

CAPTURED.

At 4 a.m. the "Investigator" arrived off the eastern arm of Plymouth Breakwater, whence she signalled to Devonport Dockyard the news of her arrival. The lights of the "Mudlark" were soon afterwards observed as she threaded her way through the tortuous passage between Drake's Island and the mainland, and in company the two vessels bore away in the direction of Penlee Point.

Officers and crew were in a state of suppressed excitement. If Captain Restronguet were a man of his word, as he evidently was, his capture seemed certain, for the waters of Cawsand Bay were admirably suited to the arrangements which Captain Tarfag had made for his great coup.

By dawn the vicinity of the bay presented a scene of animation. The cliffs between the village of Cawsand and Penlee Tower were black with people. Thousands of the good folk of the Three Towns had crossed over to Cremyll and thence, mostly on foot--for the number of vehicles available was quite inadequate--had tramped the hilly road across Maker Heights. Kept at a respectful distance by a strong patrol of picquet-boats were hundreds of crafts of all sizes, from the frail pleasure skiff to the weatherly fishing-smacks and the local ferry steamers. Beyond these lay several battleships and cruisers whose presence had not yet been required in the North Sea; and since they were of an older type, with masts and unprotected decks, they were literally covered with human beings.

A better place to effect the capture of the submarine could hardly be found, for the depth shelved gradually from twenty feet close inshore to forty along a line joining the extremities of Penlee and Picklecombe Points.

The after-decks of the two surveying vessels were buried beneath piles of nets composed of three-inch tarred rope intermeshed with flexible steel wire. These could be "paid-out" with considerable rapidity, and being buoyed and weighted would sink automatically till their upper edge was ten feet below the surface and their lower edge the same distance from the bottom. Both vessels were to start simultaneously from the western extremity of the Breakwater and head for Penlee and Picklecombe Points respectively, where strong parties of seamen were ready to haul the ends of the nets ashore.

At half-past five Captain Tarfag gave the order to commence paying out the obstructions, and at a steady six knots the "Investigator" steamed ahead, her consort, being a slower vessel, having to take the shorter distance--that between the Breakwater and Picklecombe. Precisely at five minutes to six the shoreward ends of the nets were secured.

"If Captain Restronguet keeps his promise he is already safe in the net!" exclaimed Lieutenant Egmont. "You see, there is nothing to prevent him from giving his signal at the appointed time. There are no vessels in the bay, and no aircraft overhead."

"It will be a nasty shock to those craft if he fires a rocket over their heads," remarked Arnold Hythe, indicating the crowd of small vessels that, in spite of the picquet-boats, were continually edging nearer and nearer in the desire of their occupants to see more of the promised "fun." "But what is going to happen when we trap the submarine?"

"Oh, Captain Tarfag and I have already settled about that," replied the navigating lieutenant confidentially. "As soon as we are certain that the submarine is in the bay parties of men ashore will drag in the nets, till the craft is either stranded or her propellers are hopelessly entangled in the rope and wire strands. But stand by! It's close on six."

A hush fell on the assembled multitudes. Every face was turned in the direction of the tranquil bay, where, save for a slight ground-swell, the water was unruffled.

The crowds were not kept waiting. Punctually to the minute, at less than four hundred yards from shore and almost abreast of the little village that gives the bay its name, a green and white flag, hanging limply from a staff by reason of the saturated state of the bunting, rose above the surface. Then urged by some unseen power the flag-staff ripped its way through the water, throwing the spray in silvery cascades. Then it described a circle of less than a hundred yards in diameter, then as abruptly as it appeared the emblem of the mysterious Captain Restronguet vanished beneath the surface.

"We've got him, by Jove!" shouted Captain Tarfag.

Four blasts in rapid succession from the "Investigator's" syren was the signal for the men ashore to haul away.

Slowly the ponderous line of netting was dragged through the water. Fortunately there was little or no tide and hardly any floating weed to render the task more difficult than it might otherwise have been; nevertheless it required an hour's hard work ere the enclosed space marked by the line of buoys appreciably diminished.

All the while signals from the "Investigator" were being exchanged with the look-out tower on Penlee Point. Again and again came the disquieting news "No sign of submarine."

"Surely in fifty feet, with a clear sandy bottom, those fellows up there ought to detect the craft!" exclaimed Lieutenant Egmont impatiently.

"I failed to see it at ten yards, although I admit the water was awfully muddy," said the sub.

"But what if she's given us the slip?" continued the navigating lieutenant. "Look, man; in another half an hour the bight of the net will come ashore."

"A lot may happen in half an hour," replied Hythe. "Unless she uses an explosive to clear a passage we have her safe enough, and I do not think that Captain Restronguet will resort to extreme measures, judging how he has already behaved in British waters."

"What I want to know is how Captain Tarfag proposes to take possession of her, when she is held up in the nets. He told me he had a plan, which we are now carrying out, but not a word more on the subject would he say, so, of course, I couldn't offer any suggestions."

"It is nearly high-water springs," observed the sub. "That means that we could get her sufficiently high for the falling tide to leave her stranded. Hulloa! What's that?"

A sudden commotion at less than a cable's length on the "Investigator's" starboard bow showed that some large moving object had been held up in the stout meshes of the net. Myriads of air-bubbles rose to the surface, causing a considerable patch of broken water on the otherwise smooth sea. A light-draught picquet boat, with two heavy grapnels made ready to lower, dashed over the submerged net. The iron hooks fell with a dull splash.

"Holding, sir!" shouted the midshipman in charge of the picquet-boat.

"Good! Belay there!" replied Captain Tarfag. "Drop the second grapnel, and I will send a boat to bring the rope aboard."

The working parties ashore desisted in their efforts. All the power at their command could not bring the nets home another fathom. Held by the submarine, that in turn was tenaciously anchored to the bottom of the bay, they absolutely refused to be hauled in. A sounding gave a depth of seven and a half fathoms.

"Mr. Hythe," shouted the captain.

The sub took the bridge-ladder at top speed, and saluting, awaited his chief's orders.

"Oh, Mr. Hythe," continued the latter. "I want to send a couple of men down to report on the position of the submarine. If she's anchored, get them to find out in which direction her cable leads and we can then creep for it. Also I want to ascertain whether it be possible to lower the bight of a chain under her bow and stern. If that can be done I'll signal to the Dockyard for a couple of lighters, and we'll lift the craft with the rising tide and take her straight into the Hamoaze. But mind, Mr. Hythe, I wish it to be distinctly understood that volunteers only are required for this service."

"I should like to descend, sir."

"You! Why I thought, by Jove, you had enough of it on the last occasion you encountered the submarine, judging by all accounts. But of course, I should be glad to accept your offer. Take two men with you."

The sub again saluted, and on gaining the quarter deck ordered the bo's'un's mate to pipe away the diving-party.

Of the qualified divers every man-jack expressed his desire, as vehemently as the presence of the officers permitted, to go down. Hythe would have much preferred to have taken Moy and Banks, who at his request had been transferred from the "flagship, but favouritism he strongly set his face against.

"Numbers one and two front rank men, fall out."

Number one was a tall, broad-shouldered Irishman named O'Shaunessey, a man who still retained the Wexford brogue. Number two was a dapper little Cockney, Price by name, who had the distinction of holding the Navy record for deep-sea diving.

"Look here, Price," said the sub, "I'm going down too; but I want you to clearly understand what to do. I will try to locate the Submarine, and see if there is any possibility of raising it by means of a grapnel. You I want to get as close to the bows as you can without much chance of being seen and report by telephone what forefoot she has, if any, and if there's any chance of slinging her at that end. O'Shaunessey, I want you to examine the after-end, and find out what overhang she has; also whether her propellers are foul of anything."

"Hurry up, there!" ordered Captain Tarfag. He was naturally anxious that his prey should not escape him, for, although the strain on the picquet boat's grapnel-line was maintained, the bubbles no longer rose from the enmeshed submarine.

Hythe was the first to descend, from a boat lowered from the "Investigator." The conditions beneath the surface were far more favourable than on the occasion of his descent at Spithead, for the bottom was of firm white sand, and the tidal current was barely a quarter of a knot.

Ere he had traversed fifty yards an ill-defined mass loomed up ahead of him. It was the submarine, exaggerated out of all proportion by the refractive properties of the water.

With rapidly beating heart the sub continued to advance. Suddenly he saw a figure in diver's dress approaching. He stopped. The stranger stopped too.

"I'll wait for Price and O'Shaunessey," thought Hythe, and still keeping his face towards the unknown diver he laboriously retraced his steps. As he did so the stranger did likewise.

"I wonder----" thought the sub, and raising his right arm he saw the unknown diver simultaneously raise his left. Hythe was confronted by a magnified reflection of himself. The sides of the submarine were made of a mirror-like substance.

Keeping a respectful distance from the submerged craft Hythe walked towards, but parallel to, the bows. Presently he became aware that he was passing under the lowermost edge of the net, that, with elongated meshes, was stretched tightly across the upper portion of the stem of the submarine.

Since nothing had attempted to molest him, Hythe's sense of confidence rose.

"No, they wouldn't dare play the fool now," he reasoned. "There's no escape for them, and they will make the best of a bad job by surrendering at discretion as soon as the lighters sling her clear of the bottom. I wonder where her cable is?"

No signs of the submarine's anchor and chain were visible. There were hawse-pipes--two on the starboard bow and one on the port bow, but in none of them was a stockless anchor, or indeed one of any description. The hawsepipes were partly concealed by the nets, but the meshes were sufficiently distended to make the sub certain on that point.

Keeping his eyes fixed upon the ground Hythe walked on, thinking that, from the position of the vessel, he would eventually stumble over an anchor and chain lying half-buried in the sand. At length he came to the limit of his life-line, his search unrewarded.

"That's completely stumped me--middle wicket, by Jove!" he muttered. "A looking-glass submarine fixed as tight as a limpet to the sand, and not an anchor to be seen! All in good time, I suppose. When we get her into Plymouth we'll find out all we want to learn soon enough."

With that he turned and began to make his way round the submarine once more.

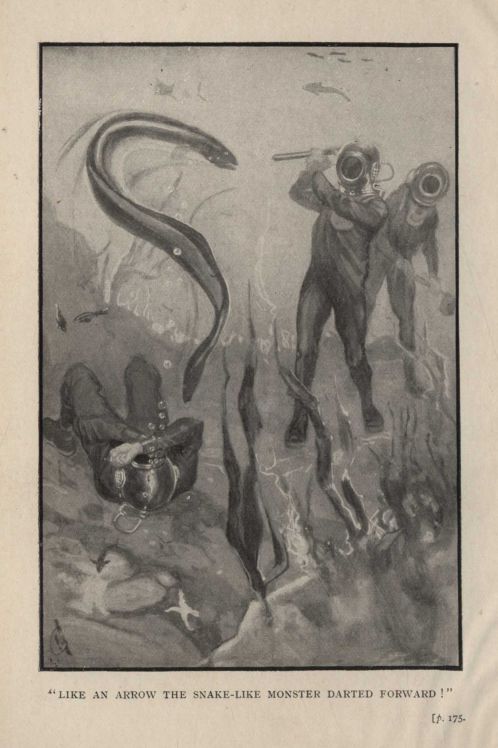

"Oh, there's O'Shaunessey!" he said to himself, as a huge helmeted figure came shambling along through the semi-transparent water. "I wonder what---- Great Scott!"

Arnold Hythe came to an abrupt stop. The diver approaching him was not O'Shaunessey. The Irishman's helmet was provided with an air-tube, and a life-line encircled his chest; this fellow had neither. He was one of the crew of Captain Restronguet's submarine.

The sub was not devoid of personal courage. The sight of the strange diver advancing in his direction aroused all the bull-dog fighting instinct in him.

"All right, my fine fellow!" he muttered. "I'll see if I can't tackle you."

Unhesitatingly he advanced towards the stranger. The latter, pausing a brief instant, held up one hand as if warning off his rival, but seeing that Hythe was intent upon grappling with him he stood on his guard.

The sub had no compunction. Although he could not under present circumstances summon the man to surrender in the King's name, he realized that, by virtues of the special Act of Parliament, he was authorized to summarily arrest any member of Captain Restronguet's command.

The next instant the two divers were locked in a close embrace, Hythe endeavouring to bring the man's arms to his sides, while at the same time he shouted through the telephone for his comrades in the boat to haul him to the surface. The unknown struggled desperately, striving to pass one heavily-leaded boot behind the sub's ankle. For ten seconds they grappled in the eerie depths of the sea, then Hythe found himself being dragged along the sandy bottom. His signal to be hauled up was being answered, and the steady strain on the life-line told him that unless anything unforeseen occurred another minute would find him and his captive at the surface.

On and on, over the yielding sand the two men were dragged, for the long scope of rope prevented an immediate upward ascent. Suddenly the unknown diver wrenched one hand free. He drew his knife, the blade glinted dully in the pale green light, and with a steady motion severed the life-line.

"Great heavens! He'll sever my air-tube next," thought the sub, but, apparently content with the advantage already scored, the fellow dropped his knife and tightened his grasp upon his antagonist.

"Blow me up!" gasped Hythe through the telephone, but although the men at the air-pumps redoubled their exertions the extra pressure of air escaped through the valve in the young officer's helmet, since he was unable to close it.

"I am attacked. Tell O'Shaunessey and Price to come to my assistance," exclaimed the sub. In spite of his powerful physique he was not even holding his own. He had bitten off more than he could chew.

During the struggle the sand churned up by the feet of the wrestlers rose till it was almost impossible to see more than a few feet away. Several times Hythe gave a hasty glance to see if his men were coming to his aid--but no.

Four grotesquely-attired figures appeared through the sand-blurred water. With a feeling of dismay the sub realized that he was hopelessly outnumbered. Since he had taken the initiative in provoking the contest he knew that he must expect to accept the consequences; yet he determined to resist as long as his strength of body and mind remained.

Powerful hands grasped him by the arms and legs. He was overthrown and lifted into a horizontal position. Even then he kicked out strongly till his captors, having good cause to fear his leaden-soled boots, desisted in their efforts to secure his legs.

A loud buzzing--the hiss of escaping air--told him that the worst was at hand. The minions of Captain Restronguet were unscrewing the union of his air-tube.

CHAPTER VI.

FACE TO FACE.

The hissing sound stopped. Instead, under a pressure of nearly two and a half atmospheres, the water rushed into the disconnected valve. In five seconds it had risen to the sub's knees. Then the inrush was checked.

It was useless to struggle, but with an uncontrollable longing to wrench himself away from his captors, rather than be drowned like a rat, Hythe persisted in his efforts, till he realized that he was in no immediate danger of being suffocated. In the place of the air pumped in from above--air that was anything but fresh--came a cool, invigorating vapour strongly charged with oxygen.

He no longer appealed for aid. He knew that with the air-tube and life-line the telephone wire had been severed. He was cut off from all intercourse from above. Even his air supply was self-contained.

Instinctively he felt certain that he would be carried off to the mysterious submarine. Curiosity prompted him to accept the situation with equanimity, his inborn fighting disposition urged him to resist. If he were to be made a prisoner he would let his captors know that the liberty of a British officer is not lightly lost.

It was a strange procession on the sandy floor of Cawsand Bay, for others of the submarine's crew had come upon the scene, and surrounded and held by five weirdly-garbed and helmeted men Hythe was frog-marched towards the huge submerged vessel.

A dull patch in the side of the craft indicated that a portion of her plating had been swung back, revealing on closer inspection a door about five feet in height and thirty inches wide.

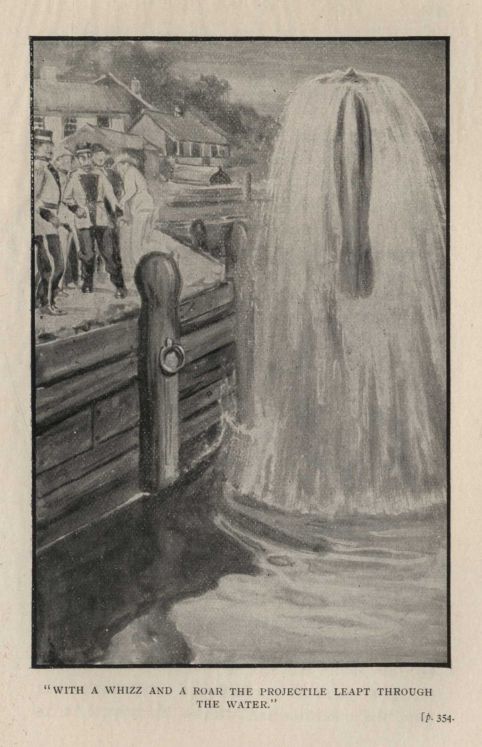

Here the sub saw his chance. With outstretched arms and legs he defied the crowd of captors to pass his resisting body through the narrow aperture. Twice he almost freed himself from their clutches. The oxygen-charged vapour he was breathing accentuated his fighting instincts, and mainly through sheer delight at being able to thwart his antagonists he lashed out right and left.