*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 40830 ***

Andrew A. Anderson

"Twenty-Five Years in a Waggon in South Africa"

"Sport and Travel in South Africa"

Preface.

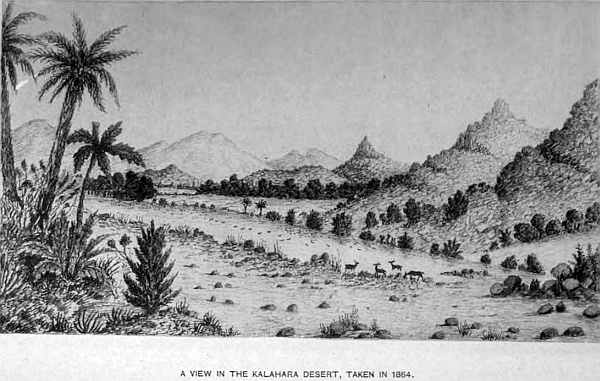

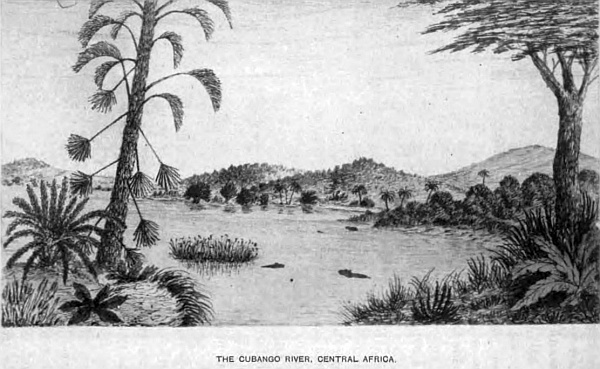

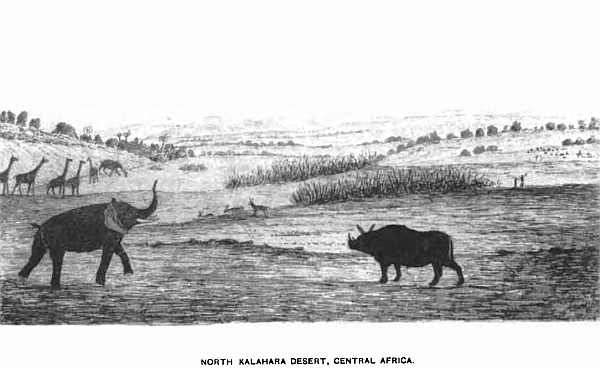

My object in writing this work is to add another page to the physical geography of Africa. That region selected for my explorations has hitherto been a terra incognita in all maps relating to this dark continent. The field of my labour has been South Central Africa, north of the Cape Colony, up to the Congo region, comprising an area of 2,000,000 square miles; in length, from north to south, 1100 miles, and from east to west—that is, from the Indian to the South Atlantic Ocean—1800 miles, which includes the whole of Africa from sea to sea, and from the 15 degree to the 30 degree south latitude.

It has been my desire to make physical geography a pleasant study to the young, and in gaining this knowledge of a country, they may at the same time become acquainted with its resources and capabilities for future enterprise in commercial pursuits to all who may embark in such undertakings, and this cannot be accomplished without having a full knowledge of the people who inhabit the land; also its geological features, natural history, botany, and other subjects of interest in connection with it. Such information is imperative to a commercial nation like Great Britain, particularly when we look round and see such immense competition in trade with our continental neighbours, necessitates corresponding energy at home if we wish to hold our own in the great markets of the world, and this cannot be done unless the resources and capabilities of every quarter of the globe is thoroughly known. And for this purpose my endeavours have been directed, so far as South Central Africa is concerned, and to fill up the blank in the physical geography of that portion of the African Continent.

When I undertook this work in 1863 no information could be obtained as to what was beyond our colonial frontier, except that a great part was desert land uninhabited, except in parts by wild Bushmen, and the remaining region beyond by lawless tribes of natives. I at once saw there was a great field open for explorations, and I undertook that duty in that year, being strongly impressed with the importance, that eventually it would become (connected as it is with our South African possessions) of the highest value, if in our hands, for the preservation of our African colonies, the extension of our trade, and a great field for civilising and Christianising the native races, as also for emigration, which would lead to most important results, in opening up the great high road to Central Africa, thereby securing to the Cape Colony and Natal a vast increase of trade and an immense opening for the disposal of British merchandise that would otherwise flow into other channels through foreign ports; and, at the same time, knowing how closely connected native territories were to our border, which must affect politically and socially the different nationalities that are so widely spread over all the southern portion of Africa. With these advantages to be attained, it was necessary that some step should be taken to explore these regions, open up the country, and correctly delineate its physical features, and, if time permitted, its geological formation also, and other information that could be collected from time to time as I proceeded on my work. Such a vast extent of country, containing 2,000,000 square miles, cannot be thoroughly explored single-handed under many years’ labour, neither can so extensive an area be properly or intelligibly described as a whole. I have, therefore, in the first place, before entering upon general subjects, deemed it advisable to describe the several river systems and their basins in connection with the watersheds, as it will greatly facilitate and make more explicit the description given as to the locality of native territories that occupy this interesting and valuable portion of the African continent, in relation to our South African colonies. And, secondly, to describe separately each native state, the latitude and longitude of places, distances, and altitudes above sea-level, including those subjects above referred to. All this may be considered dry reading. I have therefore introduced many incidents that occurred during my travels through the country from time to time. To have enlarged on personal events, such as hunting expeditions, which were of daily occurrence, would have extended this work to an unusual length, therefore I have taken extracts from my journals to make the book, I trust, more interesting, and at the same time make physical geography a pleasant study to the young, who may wish to make themselves acquainted with every part of the globe. This is the first and most important duty to all who are entering into commercial pursuits, for without this knowledge little can be done in extending our commerce to regions at present but little known.

My travels and dates are not given consecutively, but each region is separately described, taken from journeys when passing through them in different years.

Chapter One.

In Natal—Preparing for my long-promised explorations into the far interior.

As a colonial, previous to 1860, I had long contemplated making an expedition into the regions north of the Cape Colony and Natal, but not until that year was I able to see my way clear to accomplish it. At that time, 1860, the Cape Colony was not so well known as it is now, and Natal much less; more particularly beyond its northern boundary, over the Drakensberg mountains, for few besides the Boers had ever penetrated beyond the Free State and Transvaal; and when on their return journey to Maritzburg, to sell their skins and other native produce, I had frequent conversations with them, the result was that nothing was known of the country beyond their limited journeys. This naturally gave me a greater desire to visit the native territories, and, being young and full of energy, wishing for a more active life than farming, although that is active during some part of the year, I arranged my plans and made up my mind to visit these unknown regions, and avail myself of such opportunities as I could spare from time to time to go and explore the interior, and collect such information as might come within my reach, not only for self-gratification, but to obtain a general knowledge of the country that might eventually be of use to others, and so combine pleasure with profit, to pay the necessary expenses of each journey. Such were my thoughts at the time, and if I could make what little knowledge I possessed available in pursuing this course, my journeys would not be wasted. My plans at first were very vague, but, eventually, as I proceeded they became more matured, and having a thorough knowledge of colonial life and what was necessary to be done to carry out my wishes, I had little difficulty in getting my things in order. Geology was one of my weaknesses, also natural history, which were not forgotten in my preparations. The difficulty was, there were no maps to guide me in the course to take over this wide and unknown region; I therefore determined to add that work also to my duties, and make this a book of reference on the Geography of South Central Africa, and so complete as I went on such parts visited, as time and opportunities permitted, as also a general description of the country, the inhabitants, botany, and other subjects, and incidents that took place on my travels through this interesting and important part of the African continent, and so cool down a little of the superabundant Scotch blood that would not let me settle down to a quiet life when there was anything to be done that required action; for we know perfectly well before we enter upon these explorations, that we shall not be living in the lap of luxury, or escape from all the perils that beset a traveller when first entering upon unknown ground—if any of these troubles should enter his mind, he had better stay at home. But, at the same time, it will be necessary to give some idea what an explorer has to undergo in penetrating these regions, and also the pleasures to be derived therefrom.

“There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

There is a rapture by the lonely shore,

There is society where none intrudes

By the deep sea, and music in its roar.”

Byron.

It is a pleasure to be able to ramble unfettered by worldly ambition over a wild and new country, far from civilisation, where the postman’s knock is never heard, or shrieking railway-whistles, startling the seven senses out of your poor bewildered brain, and other so-called civilising influences, keeping up a perpetual nervous excitement not conducive to health. A life in the desert is certainly most charming with all its drawbacks, where the mind can have unlimited action. To travel when you please, eat and drink when so inclined, bunt, fish, sketch, explore, read or sleep, as the case may be, without interruption; no laws to curb your actions, or conventional habits to be studied. This is freedom, liberty, independence, in the full sense of the word. With these dreamy thoughts constantly before me, I determined to give such a life a trial; consequently, without more ado, I set to work to provide myself with the necessary means. Having heard, when travelling through Natal, that the country a few miles beyond the Drakensberg mountains was a terra incognita, where game could be counted by the million, and the native tribes beyond lived in primitive innocence, I was charmed with the thought of being the first in the field to enjoy Nature in all its forms, and bring before me, face to face, a people whose habits, customs, and daily life were the same to-day they were five thousand years ago. What a lesson for man! With what greed I looked upon my probable isolation from the outer world; craving for this visit to the happy hunting-ground.

The first thing to be done was to apply to an old friend, living a short distance from Maritzburg on a farm, who had been on several hunting expeditions, and returned a few weeks before, with his waggon-load of skins of various animals he had shot with his and his sons’ guns, which he spread out before me—one hundred and five—six lions, four leopards, seven otters, eight wolves, fourteen tiger-cats; the remainder made up of gnu, springbok and blesbok, and a variety of other antelopes, all shot within one hundred miles from the northern and western border of Natal, over the Drakensberg mountains, besides a heap of ostrich feathers of various kinds—a goodly bag of a seven months’ trip. The result of my cogitations with him was the procuring of a waggon and fourteen trek oxen, with the usual gear—a horse, saddle and bridle, with all sorts of odds and ends for cooking, water-casks, food of all kinds, flour, biscuits, bread, mealies for the Kaffirs, tea, coffee, sugar, preserves, and other necessaries needed for the road. A safe driver and forelooper, and an extra boy to cook and look after the horse, besides three rifles (not breechloaders, they were not known in Natal in 1860) and a double-barrel Westley Richards, and any quantity of ammunition. These three boys were all Zulus, with good characters, therefore could be depended on, which is a great thing.

Being a “Colonial” I was well up to African life and the Zulu language—a great advantage in that country. All things provided, I took several trips round the country in my waggon, up to August 1863, when I started north.

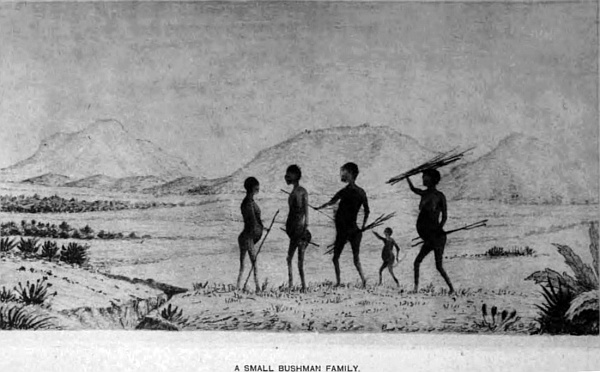

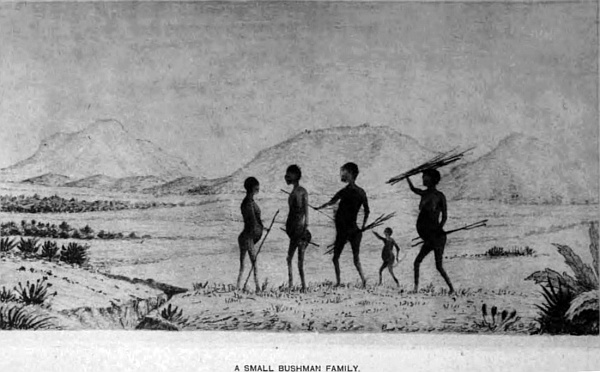

Twenty-five years ago!—a quarter of a century! What changes have come over South Africa in that time! Natal was little-known and scarcely heard of in England. The white population did not exceed one-half its present number of 30,000, and the greater part was overrun by Kaffirs, who were Zulus, similar to those of Zululand. Game of various kinds in plenty, lions were common, elephants, buffaloes, elands, wildebeests, quagga, and other antelopes, were numerous on the plains and long flats; leopards—here called tigers—wolves, jackals, and other beasts of prey, were heard nightly in the bush; and in the open rolling plains, under the Drakensberg range of mountains, that flank the western and northern boundary of the colony, springbok and blesbok, quagga and the gnu could be counted in thousands. Where are they now? Cleared from the face of the earth by the rifle, so that scarcely one is left, and those preserved that they should not be entirely exterminated. Beyond that magnificent and grand mountain range that rises in parts ten thousand feet above the sea-level, and extending several hundred miles in length, rearing its noble head far up in the clouds, and looking down as if guarding the beautiful and peaceful Natal at its feet. The scenery, especially on the western side, taking in the Giant and Champagne Castle and the lofty peaks to the north, few landscapes on earth can compare with it. Here the wild Bushmen lived in all their pristine glory; their home—the caves and kloofs in the gorges of mountains—far away from any other tribe, living by their poisoned arrows on game that comes within bowshot, and upon fruits and roots, which will be more particularly described in another chapter. Where are they now? Much like the game, exterminated by the rifle. They were then a great pest to the colonial people who kept stock near the foot of the mountain, for they would come down, after watching for days, mounted or on foot, and steal the cattle, killing all they could not carry off.

These Bushmen became such a pest that it was necessary to hunt them down. Two forces of a dozen men or more each were sent out under Captains Allison and Giles, and they got on their spoor after they had stolen a number of fine English-bred cattle and horses, many of which when they first escaped to the hills were found killed, when unable to keep up.

They tracked these Bushmen about on the hills in snow for some days, and at last the two parties met, and just before dark saw the Bushmen’s fires in caves. The parties slept on the ground, and in the morning saw a Bushman come out with a bridle to catch a horse. Suddenly, like Robinson Crusoe, he stood aghast seeing their spoor, threw down his bridle, and bolted to give the alarm. The Bushmen fought with their poisoned arrows, and as their sexes could not be distinguished in the bush, as they dress alike, all were killed, except one old woman, shot through the knee, who rode in as if nothing was wrong with her. She was cured, carried near to another tribe and turned out. No other Bushmen were ever seen after that in Natal. Previously one lad was shot through the shoulder and caught. He was never of any service, not even as an after-rider, though a splendid horseman, being quite unteachable. He never attempted to escape to his tribe, though he might easily have done so; and when taken out to track them, and coming on their caves, he broke their pots, a sign of displeasure among Kaffirs; and he said all he wanted was, to catch and kill his mother.

Starting.

Before starting on my memorable expedition, I procured some sail-cloth, to make a side-tent to my waggon, which formed a very comfortable retreat for my boys on wet nights. My driver, a fine young Zulu, could handle an ox-whip and give the professional crack to perfection. If not able to accomplish this feat, they are not considered efficient drivers. His name was Panda, after the great Zulu chief, and he was from all accounts a descendant of that renowned warrior, his father having fled into Natal some time before. He was now working to collect a sufficient number of heifers together to buy his first wife, a young Zulu maid living in a large kraal half a mile from his master’s farm. The forelooper, one who leads the two front oxen in dangerous places, and looks after the span when in the Veldt feeding and assists in inspanning, another fine young Zulu about eighteen, a handsome lad, was named Shilling. The other and third boy, younger, also a Zulu, I named Jim, as his other name was too long to use or recollect. After seeing some of my friends and saying good-bye, we make the first afternoon trek over the Town hill towards Howick, a very steep and stony road, full of ruts made by the heavy rains, and out on the rising ground beyond; where a magnificent view is obtained of the surrounding country and distant hills, of which Table Mountain, some twenty miles on the east of the city, stands out boldly in the landscape. There are several table mountains in Natal, so-called from their flat heads. My object when I commenced this journey was to push on with all speed to the foot of the Drakensberg Mountains, a distance of over 100 miles, cross the Berg at Van Reenen’s Pass, and make for Harrysmith in the Orange Free State, then determine where I should commence my journey of exploration. But I did not reach the foot of the mountain until the 12th of September, 1863, having deviated from the main transport road to visit some farmer friends, and take up one of the sons of an old “Colonial,” who had lived many years in the country as a stock-farmer, and who offered me his son as a guide, he being well acquainted with the country and people I proposed visiting. As he was a good driver and a good shot, as all colonials are, I was pleased to have his company, and being young, only seventeen, just the age to enjoy a rough and ready kind of life, it suited me exactly, so John Talbot was added to my little family. This detained me six days; as his mother wished to bake some biscuits for the road, also bread, and get some butter and other good things, I was quite agreeable to stay and go out with the old man to look up some game also, to supply my larder. So whilst the mother and her pretty daughter of true English blood, a year older than her brother John, were busy in the house, we men were also busy outside with our guns; besides large game, such as elands, koodoo, blesbok and springbok, we had excellent sport with the shot-guns, there being plenty of hares, partridges, pheasants, snipe, and ducks. The farm is situated on the Tugela river, and being some two miles from the foot of one of the spurs of the mountain, was out of the way of all traffic, and was as pretty a locality as any one could desire to live in; there was any quantity of fish, consequently there was no lack of fish, flesh, or fowl in this beautiful and quiet retreat.

The second morning of my arrival there, Mr Talbot and I, after taking coffee, saddled-up, as the sun was just peeping over the distant mountain tops in a blaze of gold and crimson light, with an atmosphere pure and clear, casting a brilliant reflection on all around,—a glorious sight to behold. This part of the world is famed for the lovely and varied tints which the sun produces in the sky in rising and setting, more particularly in the summer, forming celestial landscapes, marvellous to look upon, and grand in the extreme. On leaving the farm-house for our ride into the open plains to see if we could discover some elands, we met a Dutchman on horseback, with the usual companion rifle. After the morning greeting and shaking hands, he inquired if we had seen any stray calves about; finding we had not, he suspected the Bushmen had been down again from the mountains and had carried off two. He informed us that a neighbour of his, another Dutch farmer, a week or so before had lost some sheep, and he had traced them up into a deep kloof of the mountain, and came upon a family of Bushmen in the act of driving three of his sheep towards the hills, where he shot the two men and took a woman and two children, and brought them to his farm, making them drive the sheep back with them, and they were at his farm now.

Wishing to see them, we rode over, a distance of some seven miles, where we found them confined in an outhouse, squatting on the floor, looking anything but amiable; they were poor specimens of humanity. We had them brought out for a closer inspection. The woman was not old or young, of a yellowish-white colour, a few little tufts of wool on the head; eyes she had, but the lids were so closed they were not to be seen, although she could see between them perfectly; no nose, only two orifices, through which she breathed, with thin projecting lips, and sharp chin, with broad cheek-bones, her spine curved in the most extraordinary manner, consequently the stomach protruded in the same proportion, with thin, calfless legs, and with that wonderful formation peculiar to this Bushmen tribe, and slightly developed in the Hottentot and Korannas. The two little girls—the eldest did not seem more than ten or twelve—were of the same type, the woman measured four feet one inch in height. The old Boer wanted to shoot them, but his vrow wished to keep and make servants of them. Their language was a succession of clicks with no guttural sound in the throat, like that of the Hottentot and Koranna tribes, but both languages assimilated so closely that it is clear the Hottentot and Koranna have partly descended from this pure breed, for a pure breed they are, and may be the remnants of almost a distinct race that lived on the face of this earth in prehistoric ages.

The quarter of the globe in which they are found, at the extreme end of a large continent, in a rugged and mountainous country, a locality well adapted to preserve them from utter extinction, may be the cause of their preservation; at any rate, there are no other people in the world like them, and their having a language almost without words except clicks, is a most peculiar feature in connection with this entirely distinct race, and for anthropological science, these people should be preserved, that is the pure breed, unmixed by Hottentot or Koranna blood.

Leaving the Boer farm, after the usual cup of coffee, we skirted the hills which ran out in grand and lofty spurs, broken here and there by perpendicular cliffs, many hundred feet deep, clothed with subtropical plants and shrubs, with beautiful creepers climbing among the projecting rocks, and hanging in festoons, with crimson and yellow pods, contrasting so beautifully with the rich green around.

We reached the head of one of the Tugela branches, one of the most picturesque and lovely landscapes I have ever seen in Africa. The lofty mountain range, 10,000 feet in altitude, forming the background, with their peaked and rugged summits, fading away in the distance to a pale bluish pink tint, with the nearer mountains, and a glimpse of a pretty waterfall, with the richly-wooded foreground and placid stream at our feet, completed a picture seldom to be seen. My friend and host, Mr Talbot, proposed a halt at this spot, therefore, selecting a fine clump of trees to be in the shade, for although early in the spring, the sun shining down upon us from a cloudless sky was unusually warm; we were therefore glad to seek the shelter of the trees, off-saddle and knee-halter the horses to feed, whilst we stretched ourselves on the soft young grass to view the scene around and take our lunch.

As it was early in the day, we gave the horses a good rest, and then saddled-up for our return journey. There were many small herds of various kinds of antelopes, but too far away to follow. Springboks we could shoot, but being so many miles from the farm, we waited until we got within a reasonable distance to carry them on the horses, which as we approached home we had plenty of opportunities of doing, and secured three, two of which I made into biltong for the road. On arriving at the farm, my boy Panda showed me a large snake, one of those cobra de capello whose bite is very dangerous, sometimes causing death; it measured five feet in length, and was killed in the house, which was built with poles and reeds, called in the country a hartebeest house, with several outbuildings on the same plan. They are made very comfortable and snug within, but will not keep out snakes; most of the cooking is done out of doors, where a fire is constantly burning: early coffee about six, breakfast at eight, dinner at one, and supper at sundown. This is the general custom on the farms. After an outing of nearly twenty miles, we enjoyed our dinner of baked venison of eland, with stewed peaches to follow, and good home-baked bread. As lions were very plentiful, as also wolves and leopards, the farmers had to make secure kraals for their cattle, sheep, and goats; the horses were kept in sheds; and with these precautions it not unfrequently occurred that a leopard, which out here is called a tiger, leaped the enclosure and carried off a goat or sheep. A few weeks before my arrival here, some wolves and hyenas broke into the sheep-kraal, killing seven, carrying three half a mile away, where their remains were found next morning. They make these attacks mostly on dark and stormy nights, when it is difficult to hear any noise when shut in the house.

The next day my host, his son John, and myself, after breakfast saddled-up, and with our rifles, started for the native location, which is an extensive tract of country under the foot of the Berg, occupied by the Zulus, who have large kraals and plenty of cattle, in order to buy some young bullocks to break in for trek oxen. Visiting some on our way, at one of which we off-saddled to rest, the Kaffirs coming out to stare as usual, the young intombes (Kaffir maids), like their white sisters, curious to see the strangers, came to look also. John and his father being well known to them, we were asked in to have some Kaffir beer. Some of the girls were very pretty, and we told them so, which they took as a matter of course, and came forward that we might have a better look at them, and seemed pleased to be admired.

Beautifully formed, with expressive countenances, tall, and carrying themselves as well as if they had been drilled under a professional; their constant habit of carrying heavy Kaffir pots of water, which can only be done by walking erect, has produced this effect. One young Kaffir was very busy making a hut for himself, as he was going to be married. The care and attention he displayed on its erection, and the ingenuity with which he interweaved each green stick, which was tied with thin slips of skin, was most interesting, and he seemed quite proud when praised for his good workmanship. One of the girls was pointed out to us as his wife that was to be, a fine good-looking girl about seventeen, ornamented with plenty of brass bracelets and beads, the present of her fiancé. They are not encumbered with much clothing, being in a state of nature with the exception of an apology for an apron, or frequently only a string of beads, two or three inches long. Their huts and enclosures are kept clean and neat, and in every respect as far as order and quietness are concerned, the Zulus may set an example to many white towns. After purchasing a few Kaffir sheep, we returned to the farm.

The 3rd of September, a lovely bright morning, two beautiful secretary-birds came walking close past the farm,—they are preserved for the good they do in killing snakes, therefore a heavy fine is set upon any one shooting them; they are similar in shape to the crane, but much larger, with long and powerful legs. It is strange to see them kill a snake; one would think that with their strong horny legs and beaks, they need only tread on and kill him with their beaks, but they are evidently afraid to do this. They dart into the air and pound down violently upon him with their feet until he is dead.

Shortly after breakfast, a Zulu girl came for work; she had run away from her father’s kraal, to escape being married to an old Zulu Induna, living on the Bushman river, and had walked nearly forty miles across the country to Mrs Talbot’s to escape the match. She told, when pressed, that her father wanted to sell her for twenty heifers to the old man, and she did not like it, as she liked a young Zulu, therefore she fled from the kraal the previous day, and had walked that distance without food, avoiding other kraals, fearing the people, if they saw her, would send her back, and she begged the “misses” would let her stop and work for her. She was a very fine young girl, apparently about seventeen, tall, and well-made, and very good-looking, without ornaments or anything on her in the way of clothes. The “misses” soon found an old garment to cover her nakedness. Poor girl, she is not devoid of affection, as this action of hers shows. I fear there are many similarly situated, both white and black. So Mrs Talbot had compassion and employed her, and she turned out a very good and useful help. The Zulu war was caused by a similar occurrence, two girls having taken refuge in Natal, whence they were fetched out and killed by the Zulus, who refused to give up the murderers.

Some few days after, we were all sitting under the shade of the trees close to the house, taking coffee, when four young Zulu girls came, each carrying a bowl on her head, full of maize, to exchange for beads and brass wire to make bracelets, as all outlying farmers keep such things for payment. Their ages might be about fifteen. One of them had her woolly hair in long ringlets all over her head, and seemed to be a born flirt, her manner was so coquettish; all of them were very good-looking, as most of them are when young.

I told them if they would give us a dance, I would present each with a kerchief. This gave much satisfaction, and they commenced their Zulu dances, singing, laughing, and playing tricks, in their native way. When it was over the kerchiefs were given, which they fastened turban fashion round their heads, then marched up and down, much pleased with their appearance, showing they are not devoid of vanity. Savage or civilised, woman is woman all over the world. Most of the Kaffirs living in Natal belong to the Amalimga Zulus, those in Zululand to the Amazulu family. Sixty years ago there were cannibals in Natal, in the mountains. I was shown the spot and tree, by an old Zulu, where the last man was cooked and eaten. At that time the country was infested with hordes of wild Bushmen, of the type before described, who had their stronghold in those grand old mountains that skirt the northern and western boundary of this fair and beautiful little colony—the cannibals were not Bushmen; and also with wandering tribes of the Amagalekas, Amabaces, Amapondas, many of them travelling west, and who settled on the Unzimvobo river, and along the coast in Tambookie and other districts, and remained in a wild and savage state up to within thirty years of the present time; then it was a howling wilderness, swarming with lions, leopards, wolves, and other beasts of prey; only a few years ago lions were very numerous. The landlord of the Royal Hotel at Durban told me a lion came into his yard in the daytime, leaped into an open window and seized upon a fine hot sirloin of beef that was on the table with other good things prepared for a dinner-party, and quietly walked off with it. At the present time (1860) up in these parts they are to be seen daily, and great care is required to preserve the oxen and other animals from falling a prey to their nightly visits. Only three weeks back a farmer on the Tugela had one of his horses killed and partly eaten before morning. The horse was made fast in a shed, a short distance from the house; it appears there were several lions from the number of footprints to be seen in the morning. The Kaffirs forgot to fasten the door at night. Almost every evening we hear them.

A Lion in a Dog-cart.

As an instance of their boldness at times, for, generally speaking, they are cowardly, the following was related by Mr Botha, a respectable, educated Boer farmer, and is quite true. It happened to his uncle.

“Journal.—Apes river, between Pretoria and Waterborg. Arrived at the Outspan, remained until next night at twelve, then started the waggon off on the springbok flats (twenty miles without water). The party consisted of L. Botha, P. Venter, and the servants, one waggon with span of sixteen oxen, one cart and two horses. Venter and Botha remained at the Outspan place with the cart and horses and a bastard Hottentot boy called Mark, twelve years old.

“The waggon had been gone half-an-hour when they heard the rattling of wheels in a manner which made them think that the oxen must have had a ‘scrick’ (scare) from a lion, as that place is full of them. Mark, who was sleeping alongside the fire, was called up to bring the horses. The lazy fellows there won’t do anything themselves, not even when there is a ‘scrick’ from a lion. They were soon going to render assistance to the waggon, going at a jog trot (even then they did not hurry), when Mark, who was on the front seat, called out, ‘Baas, de esel byt de paarde’ (‘The donkey bites the horse’), and immediately the cart stopped, and a lion was seen clasped round the fore-quarters of the favourite horse. Before the gun was taken up, down went the horse; meanwhile the gun was levelled at the lion, but the cap missed. Another was searched for, but it would not fit, as it was small and the nipple a large military one (so like a Boer!). The lion now was making his meal off the horse, lying at his ease alongside the splash-board, eating the hind-quarter, Botha trying to split a cap to make it fit in vain; so Venter took the gun, and Botha made up powder with spittle to make it stick, and Venter was to take aim and Botha to do the firing with a match. Just as it ignited, the lion sprang right into the cart between them, and gave Venter a wound on the head and scratched his hand with his claw, and bit off a piece of the railing, sending the gun and Mark spinning out of the cart, and with that force that the lion fell down behind the cart. He then came round, as fast as he could, on to the dead horse, and continued his feed; but, not in the same cool manner, but making a growling, like a cat with meat when a dog is near, and now and then giving an awful roar, which made the cart, men, and all shake again. The other horse, which is a miracle, stood quite still, never attempting to budge an inch. After the lion had fed he went away, and Botha got out, intending to unharness the remaining horse, but no sooner was he on the ground than he heard the lion coming on again at full speed. He threw himself into the cart, and the lion stopped in front of the living horse, which tried to escape but was held fast by the pole-chain after breaking the swingle-trees. The lion gave one jump on to the horse, and with one bite behind the ears killed him. Botha was lying on the front seat, with his legs hanging down alongside the splash-board, when the lion came and licked the sweat of his horse off his trousers, but did not bite, Botha remaining quite still, which was the only chance, in the dog-cart from ten o’clock, when first attacked, until near daybreak, when the lion left; you may imagine what Botha felt as he looked at his two valuable hunters. Soon a waggon came along and took on the cart, when their driver told them that, soon after he left, suddenly the oxen bolted for some distance, but luckily in the track, by the driver cracking his whip on both sides of them, which, no doubt, kept off the lion also, who was galloping alongside.” This is a most remarkable case of boldness in a lion, when not wounded.

The South African lions are not nearly so fierce and plucky as the Syrian, and they are often very cowardly. A Hottentot relates that he once came on a lion asleep, and put his elephant “roer” at his ear, when before he fired, he heard klop! klop! and the bullet, which had been secured only by a loose paper wad, rolled down and dropped into the lion’s ear, who jumped up and bolted!

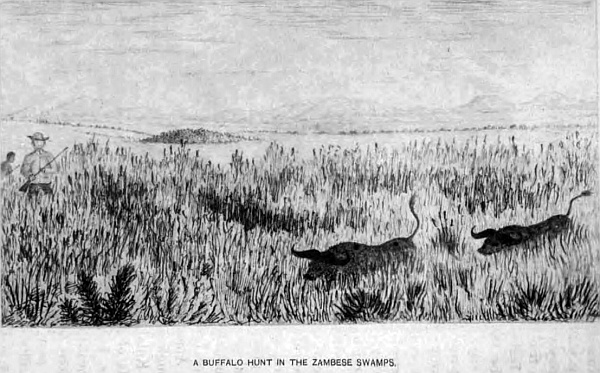

There are a few herds of buffaloes in the Bush, but they are very wild and dangerous to approach, having been so much hunted. I have seen them tamed and inspanned with oxen. Elephants are seen no more in Natal. The Berea, near Durban, which is an extensive Bush country, was a favourite resort for them, and the hippopotamus is becoming extinct in the rivers. There are five preserved in the Umgeni river near Durban, off a sugar estate; one had disappeared for some time, and then came back with a calf. This “Hero” must have swum 100 miles by sea into the Zulu country after her Leander. There are also a few in the Upper Umgeni, near Maritzburg. I have been told by many Zulus that they have seen them leave a river, go out to sea and follow the coast down until they arrive at another river and enter it, and some of the old settlers have confirmed it.

The coast is much more tropical than the up-country. Fruits, such as guava, citron, lime, tamarind, loquat, lemon, orange, banana, pineapple, figs, grow to perfection. Also peaches, and apples, and every kind of European vegetable. The coast is favourable for sugar, tea, coffee, tobacco, indigo, arrowroot, ginger, all kinds of spices, and the cotton-plant has just been introduced on the coast, but it failed, owing to the aphis fly; the castor-oil plant and the aloe grow to a great size. There is also some very fine timber, particularly in the kloofs amongst the hills. Coal, in seams eleven feet thick, exists in the Newcastle district, as the name denotes. Iron abounds all over the colony. Altogether, Natal is a very pleasant colony to settle in; the climate is everything that can be wished. The two principal drawbacks are the annual grass-fires, destroying everything as they sweep over the country, killing all young forest trees, and making the grass of a coarser texture; and there are sometimes many months of drought. But these are not confined to Natal; the same drawbacks pervade every part of South Africa, even up to the Zambese, and the long drought that lasts for months is more common towards the western portion of the continent than it is on the east coast. The summer being the rainy season makes it pleasant, though the lightning is terrible, and dangerous to a degree which, perhaps, does not exist anywhere else. The most dangerous are the dry storms.

Chapter Two.

My first start across the Drakensberg Mountains—Visit Harrysmith, Wakkerstroom, Utrich, Newcastle, Home.

Early in the morning of the fourth found me ready for a start for a four months’ trip before plunging into the unknown land. My little expedition consisted of a waggon and fourteen trek oxen, a young four-year-old Natal horse, my driver and two Zulu boys, myself and young Talbot, well provisioned for my journey. Leaving my kind friends, I took the road to Ladysmith, but turned off to the left before reaching that town, and took the Transport Road, leading to Harrysmith in the Free State, over the mountain, passing up by Van Reenen’s Pass, a very steep and long hill, the altitude being 7250 feet above sea-level, and arrived at Harrysmith on the 18th of September, 1863, where I outspanned close to the town. The country along the whole distance up to the berg is very pretty and picturesque. From the base of the berg to the summit the distance is about five miles, with a rise of 2000 feet, that being the difference in the altitude between the upper or northern part of Natal and the Orange Free State, consequently being so much higher and open, makes the winter much colder. From this elevation, and looking back upon Natal, a more lovely or extensive landscape can scarcely be imagined. To the right and left huge rocks stand out on the rugged summits in those grotesque forms from which descend perpendicular cliffs and deep kloofs clothed in subtropical vegetation, between which long spurs of the mountain are thrown out, terminating in rolling plains and beyond lofty hills and deep valleys. Far away, on the right, continues the Drakensberg, with its lofty and noble peaks rearing their heads far into the clouds that hang on their summits in loving embrace, until they are lost to view in the pale tints of the evening sky, leaving the central view open to the sea, 120 miles to the coast, where the bluff at Port Durban can be distinguished overlooking the intervening country with its plains and hills.

It was here, at the Bushman’s Pass, 9000 feet high, that the sad affair with Langalibalele’s tribe occurred. A number of them had been at the diamond-fields, where they had procured guns for wages. No Kaffirs in Natal are allowed to have guns, except a few hundred, by special licence, and the sale of gunpowder is all in the hands of the Government, white men even not being allowed more than ten pounds a year, and they cannot import guns without a special permission from the Government.

The entire immunity of Natal, from its first annexation, from Kaffir wars, which have caused so much waste of blood and treasure at the Cape, is owing chiefly to this wise law, which is so rigidly enforced that a number of guns were seized which had been made in Natal, at a cost of 2 pounds 10 shillings each. The barrels were gas-pipes, whilst good muskets could have been imported at 5 shillings each. All the Cape wars have been caused by the omission of this simple precaution.

The Natal border Zulu chief Langalibalele had been a rebel from his youth upwards. He rebelled against Panda, the Zulu king, and barely escaped into Natal with a few followers, leaving all his cattle behind. Shortly after he returned, killed the keepers of the cattle, and took them into Natal. There he was given about the best “location” on the beautiful spot here described in the Drakensberg. Many refugees from Zululand joined him, and his tribe became powerful. But they were always restless and contumacious. At last about 250 of them brought back from the diamond-fields the guns which they had received for wages, and when called upon to give them up refused to do so, or even—as subsequently allowed—to send them in to be registered, and they insulted the messengers sent by the Government. A force was consequently marched into the location, and as the whole tribe was about to depart into the Zulu country with the cattle, a proceeding which was against all Kaffir law, the passes of the mountains were occupied, to prevent their escape, by volunteers, and the soldiers were kept below. To the Bushman’s Pass a force of about twenty of the Natal carbineers (cavalry) was sent up. The pass, 9000 feet high, was so steep that they could not ride, but had to lead their horses, in doing which Colonel Durnford (killed at Isandhlwana), who commanded the party, was pulled down a rock by his horse, and his shoulder dislocated. It was pulled in at once, but being a delicate man the pain and fatigue overcame him entirely, and he was obliged to remain behind, while the rest went on and bivouacked on the pass. During the night, young Robert Erskine, son of the Colonial Secretary, went down twice to his assistance, taking brandy, etc., and eventually he got him on to his horse and up to his men. Early next morning a part of the tribe, with the cattle, came up, the rest having passed before, and occupied the rocks around, being armed with guns.

Unfortunately, the Governor of Natal had got it into his head that he was a born soldier, and had accompanied the soldiers who were below. As the captain of the volunteers knew no drill, and could not move the men, the Governor—who was weakly allowed by the colonel in command to dictate—sent Major Durnford, an engineer—who knew no more than the captain about manoeuvring men—in command, and to this folly added a mad injunction “not to fire first!” in obedience to which Durnford allowed the tribe to keep coming up. Erskine, who had been private secretary to the former governor, and who knew the tribe well, having lived among them sketching, and having had twenty-five of them working for him at the diamond-fields, offered to go down the pass and remonstrate with the chiefs who were below. Major Durnford would not allow it, saying that he had saved his life, and it was certain death. The tribe kept coming up and lining the rocks, calling out, “You’ll never see your mother again! That’s my horse! That’s my saddle!” etc.

At last a cowardly fellow, a drill-sergeant, formerly in the Cape Mounted Rifles, who had been allowed to join the force as dry-nurse, persuaded the men that they would all be killed, and they sent their captain to Durnford to say so, and that as he would not allow them to fire they would not stay. On which Durnford called out, “Will nobody stand by me?” when Erskine said, “I will, major,” and another, Bond, said so, as also did one more. Durnford then said, “If you will not stand by me you must go;” and not knowing the cavalry word, the drill-sergeant gave the word, “Fours right! right wheel! Walk! March!” As they filed past the rocks, the Zulu in command called, “Don’t fire until they have passed,” and they then fired and shot down the whole rear section, and the rest galloped off, except Durnford, who was drinking at the source of the Orange river. His bridle was seized by two Zulus, and one wounded him in the shoulder. Although one arm was disabled, with the other he shot them both, and escaped.

At the same time the Kaffir interpreter, who fought gallantly, was killed, and Erskine also, whose horse was shot down, was shot through the head and heart, in the source of the Orange river. One of the four, whose horse had been shot down, caught Erskine’s horse, which had got up again, and escaped on him for a space. The horse then fell dead, and two of the men dismounted and covered him, shooting some of the Zulus who were coming on. He caught Durnford’s spare horse running by, and after some delay and danger from a shower of bullets, succeeded in getting Erskine’s saddle on to the horse, and escaped. Durnford tried in vain to rally the men, and they went helter-skelter down the pass, the captain—afraid to ride down—being sledged down on his stern.

The bodies were allowed to remain there several days, although there was not a Zulu near, and then they were buried by Durnford under a large cairn, erected with rocks, interspersed with the beautiful heaths and flora growing around. Erskine’s body was found in the source itself of the Orange river. The people erected a handsome monument to their memory in the market-square at Maritzburg, and another to those who fell at Isandhlwana—about thirty. Thus, out of a troop of fifty, thirty-three of the Natal volunteer carbineers fell in these two affairs owing, on both occasions, to the grossest mismanagement. Ne sutor ultra crepidam!

The tribe was afterwards hunted for two months in these mountains by volunteers only, and captured with their chief, Langalibalele, who was sent to the Cape, and kept more comfortably than he ever was in his life, in a nice house and grounds, with entire freedom to move about, his only grievance being that he was not allowed more than three of his wives, the cause of this distressing privation being simply that the balance would not come. An absurd proposition was sent out by the Home Government lately that he should be allowed to return to Natal, but it was promptly quashed by that Government. Coelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt, as was proved in the case of Cetewayo’s restoration, “who had learnt and forgotten nothing.”

This, if it can be called one, is the only rebellion ever known, or likely to be known, in Natal, where the Kaffirs are thoroughly loyal. Shortly before this a little raid was made into Natal by one of Moshesh’s sons, when two natives were killed and some cattle lifted. A force was sent up, too late, and en route the Colonial Secretary and Secretary for Native Affairs, who were sitting in a waggon, were watching a tribe, when they diverted, and forming regularly into line their orator ran out, and running as they do up and down made an oration, “There’s the Government in the waggon! What’s the meaning of this? Why is this land invaded? Why are our people killed and our cattle stolen? Why were we not called out sooner? Was it that we are not trusted? Wow!! There sit under that waggon Langalibalele’s people! Who are they? Dogs! that we used to hunt down; and would again, if not prevented by the Government.”

Sir T. Shepstone did not even condescend to address them himself, but in a few words, through an interpreter, told them they were quite loyal, had the approval of the great Queen, and could pass on, which they did, moving off by companies from the right, like soldiers, and singing a war song, making the earth tremble with their stamping. (On such occasions extraordinary licence of speech is allowed by the Zulus.) All these tribes would fight well for us at first if there were to be a rising outside, but after a bit they would join their own kind, as they both feel and say that white and black blood can never mingle because we despise them.

The great change in climate and vegetation is very perceptible on leaving fair Natal for the cold, dreary, open, and inhospitable Free State. Harrysmith, in 1863, was a poor, dull, sleepy town, only supported and kept alive by a few transport riders on their way to the Transvaal and the small villages of the Free State. But after the annexation of the former State by the British Government in 1877, it soon became a town of importance, and being on the main road from Natal, large and well-built stores, houses, churches, and schools soon put life into its inhabitants. Thanks to British gold for turning a howling wilderness into a land of promise!

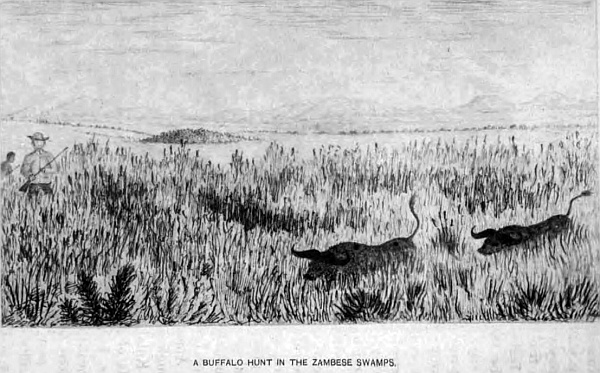

I remained two days to gain news and information about the locality, and the various roads to the north; game being plentiful in all directions, principally blesbok and springbok, wildebeest or gnu, quaggas, hartebeest, and others. The ostrich was also plentiful. I decided to follow the game up, taking the advice of my Natal friend, who had recently returned from his shooting excursion. I took the road leading east, and less frequented than the others, which eventually leads to the newly-formed town of Wakkerstroom, on the eastern border of the Transvaal, and also north from that town to Lydenburg, now the gold centre. Anxious to make the most of my time, as I had to return to Natal before starting on my grand explorations to obtain a fresh driver and two Kaffirs, I was constantly in the saddle after anything that crossed my path, travelling slowly on, shooting as much game as we required for the road. To shoot more would be mere waste, although the Boers make a practice of killing as many as they can for the sake of the skins, leaving the dead animals to be devoured by lions, wolves, or any other animal.

One night, as we were outspanned on the bank of a dry sluit, close to a small but thickly wooded koppie (hill) and large blocks of stone, we were disturbed by hearing the roar of two or more lions, within a very short distance of our camp. Not having made any preparation to receive visitors of this kind, we were all soon on our feet with rifles. The fire had gone out, but the stars gave some little light, sufficient to see all safe, particularly my horse. We were all on the watch, peering into the darkness, when we saw two lions cross over from the opposite bank and enter the near koppie. I was told before starting, by several old hunters, never to shoot at a lion when near, if it can be avoided, unless certain of killing; for if only wounded he would attack before you could reload.

Our anxiety was for the safety of our oxen and horse, fearing they might get away and be caught by the lions. I made the two Kaffirs collect a few sticks, and with what was left from last night made a fire, which threw a light into the bushes, where we saw our two friends enter, and shortly after I saw a pair of eyes shining like fire from out of the wood within thirty yards. If I could have depended on my Kaffirs, all being armed, he would certainly have had the contents of my rifle, but knowing them to be bad shots when cool, and that they would have been worse than useless in time of danger, to my great disgust was I obliged to stand and watch only. As they left the koppie, they made a circuit of my camp, but at a greater distance. Taking the two rifles from the young Kaffirs, placing them against the fore-wheel of the waggon, to be ready at a moment’s notice, I could not resist so fine a chance of a shot in the open, only fifty yards distant; the light of the fire giving out a good glare, I had a full view, and fired, and found I had wounded one—the thud of the bullet is sufficient to know that. My driver, a fine Zulu, and young Talbot, had their rifles ready in case he charged, which he did, in short bounds. As he neared, they both fired and both hit, but not sufficiently to kill him; but he was unable to move, as his hind-quarters were rendered powerless. Reloading, we walked up, and I gave him a bullet as near the heart as I could, when he fell over; the other we saw moving away into the darkness—a fine full-grown lion with dark mane. This was the third lion that had fallen by my rifle. The little affair detained us the following day, skinning and pegging out to dry in the sun, in addition to several other skins of the game shot on the road, eleven in all. When a skin is taken from an animal, I sprinkle a little salt over it, then roll it up, to be pegged out at a convenient opportunity.

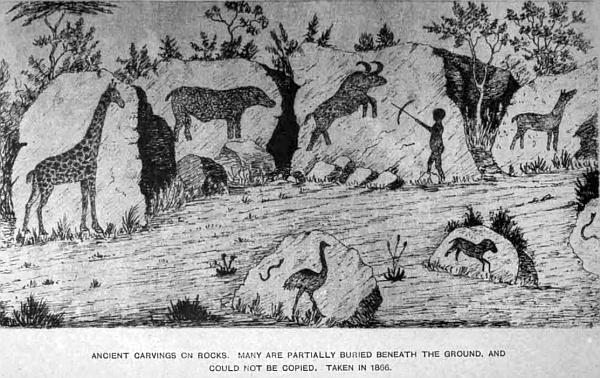

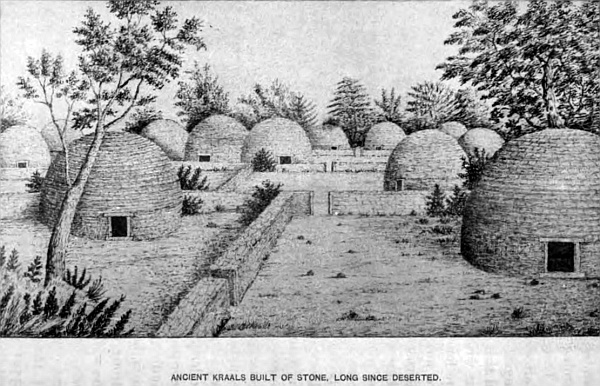

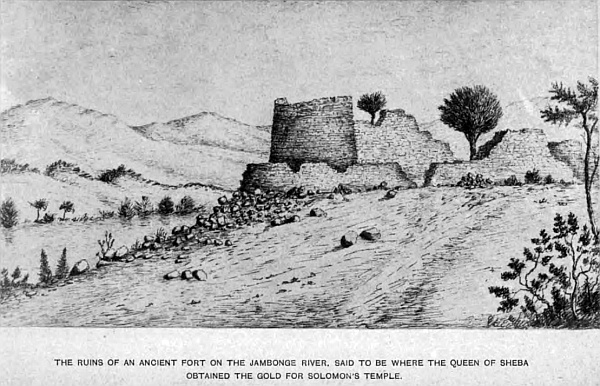

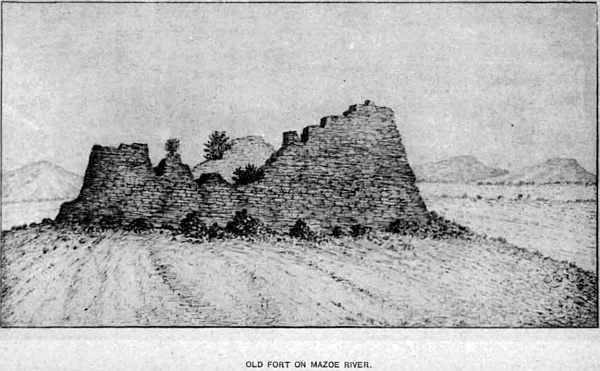

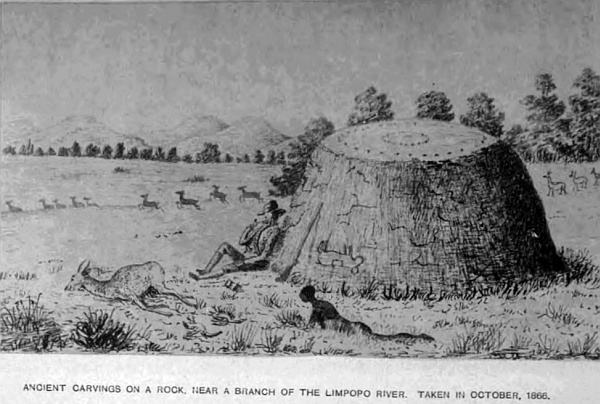

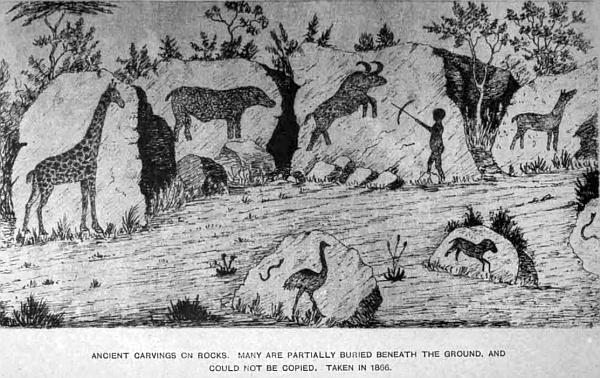

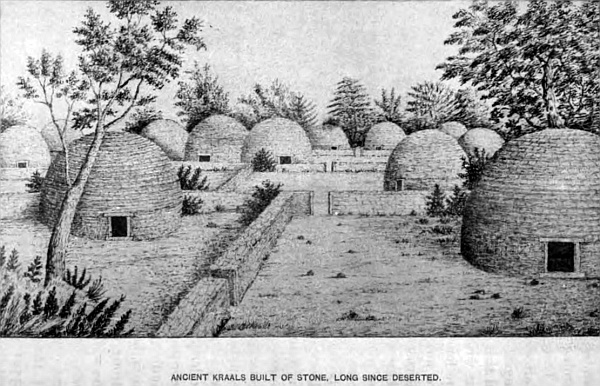

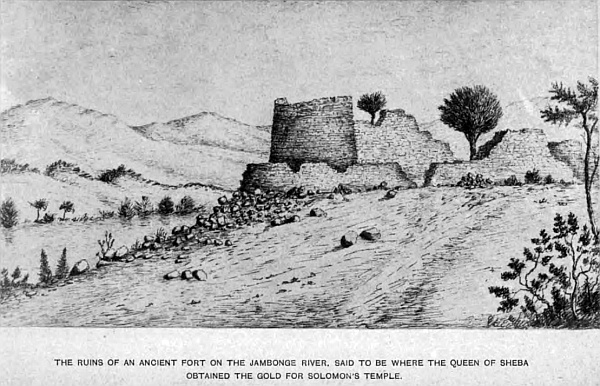

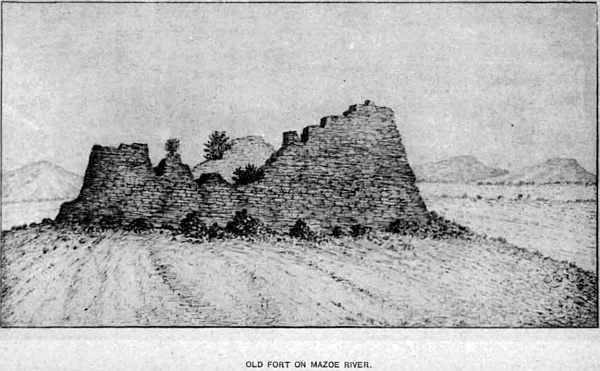

The next day we made a fresh move towards a lofty isolated hill in the Free State, which we reached in two inspans, and crossing a stony sluit, outspanned under a few trees, close to some very ancient stone walls built without mortar. They were square and some twelve feet high. The open plains were full of game of many kinds. Wishing to explore this hill, early in the morning after coffee I took my rifle to climb to the topmost ridge, letting John have the horse to get a springbok. After rambling about the hill, scanning the country all round, I was coming down when I nearly stumbled on a wolf (hyena), which must have been asleep amongst the stones. I was within twenty feet when I fired, killing him at once. Not far away were two large black eagles; the report of the rifle seat them soaring away into space. About half-way down the hill I saw two stones that had evidently been cut into shape by a mason; they looked like coping-stones, with well-marked lines, and perfectly square. I took their measure and a sketch of each, both of them exactly a foot in length and six inches wide. They evidently belonged to some ancient building, but when? is a question not so easily solved. But other stone huts two days’ trek beyond were clearly erected by a race long since passed away; they were circular, with circular stone roofs, and nearly two feet thick, of partly hewn stone, beautifully made; a stone door with lintels, sills, and door-plates. Kaffirs have never been known to build in this way. Between each hut there was a straight stone wall, five feet in height, with doorways and lintels, communicating with each square enclosure, perfect specimens of art. They were, I believe, erected by the same people who worked the gold-mines, the remains of which we frequently find in the Transvaal and the Matabele, and beyond, where so many of their forts still remain. In the Marico district there are two extensive remains of these stone towns, which must, from their extent, have occupied many years to complete. The outer wall that encloses the whole is six feet thick, and at the present time five feet high. Several large trees are growing out and through the roof of some of them. They are how the abode of the leopard, jackal, and wolf, and so hidden by bush they, are not seen until you are close upon them. Broken pieces of pottery are the only things I have discovered. The present natives know nothing of them; they are shrouded in mystery. Many remains of old walls are standing, showing that at one time this upper part of the Free State must have been thickly populated. At this outspan I killed a yellow snake, three feet in length, with four legs, but not made for locomotion. I heard there were such in Natal, but this is the first I have seen. When he found he could not make his escape, he curled himself into a circle, with his head raised to strike similar to other snakes. I consigned him to a bottle of spirits. I also shot one of those beautiful blue jays, as there were many in this district.

I pass over my shooting exploits, as there is nothing worth recording, each daily trek being almost a repetition of the last, until we arrive in sight of Wakkerstroom, a poor village, a few houses, flat roofs, single floors, built in an open country near a lofty hill, which stands on the main road from Natal to Lydenburg; we remained only a few days, then went north, as far as Lake Crissie, an open piece of water, no trees or bushes near; a solitary sea-cow is the only occupant of this dismal-looking place. In this district the Vaal river rises, and many small branches meet, until the veritable river is formed. The elevation at the lake was 5613 feet, and on a hill a few miles north I found the altitude above sea-level to be 6110 feet, an open grass undulating country as far as the eye could see, except on the east, where the mountain range that forms the Quathlamba is seen in the distance. I retraced part of the road, and turned south-east, over the hills leading to where Lunenburg now stands, and on towards Swaziland, which is an independent native territory, thickly populated and very mountainous; there are rich gold-mines there now, and some of the mountains attain an altitude of 8000 feet.

The greater part of the summer months, a mist envelops the hills, but it is a very healthy part of Africa, and horse sickness is rarely known to exist, consequently many horses are bred here. Passing Kruger’s post, through Buffel forest, which is hilly, and splendid timber trees cover the entire country, the scenery is grand and wild; quartz reefs crop out in all directions, sandstone, shale, and in some places limestone overlap the granite formation, which compose these lofty ridges of the Drakensberg; shale, which indicates the existence of coal, is frequently seen in the valleys, and along the Pongola river and its several branches.

I left Harrysmith on the 20th September, 1863, arriving on the banks of the Pongola river on the 16th October. In that time I had treked 350 miles, being delayed on the road shooting and exploring.

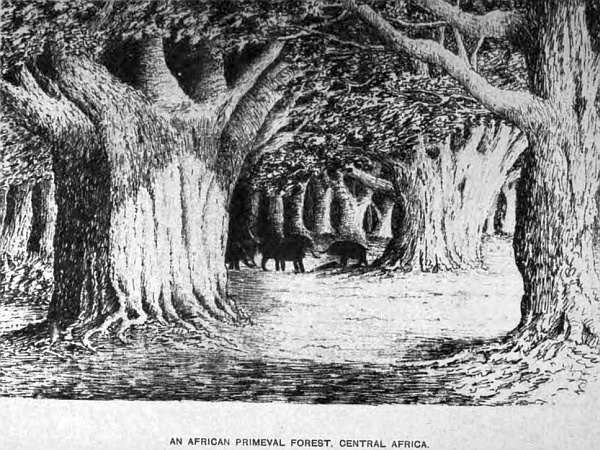

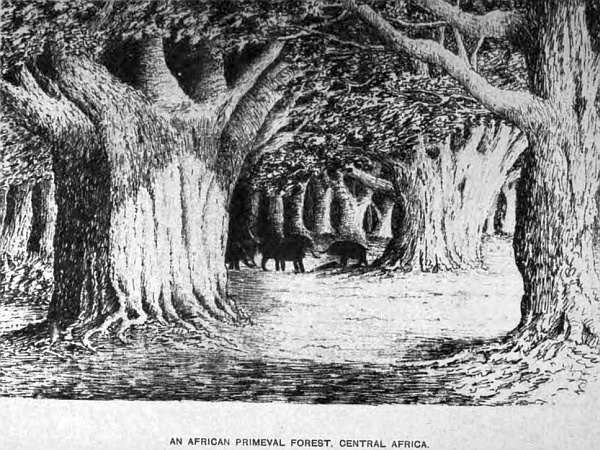

The people at Wakkerstroom wanted to know what I was doing in the country, as I did not handel (trade), and was not a smouser, the term applied to those who went about the country in waggons to sell and buy. They would not believe I came into the country for pleasure and to shoot, but I was set down as an English spy, as I took notes and made sketches of the country. When I showed them a small drawing of the town with the hill at the backhand people walking about, they held it upside down, and said it was mooi (pretty). Most of the Boers are very slow in comprehending anything, the women are much quicker, and turned the picture round, and knew it at once, as also some Kaffir girls, pointing to the figures, naming whom they represented with expressions of delight. Some of the girls seem to have a natural gift for drawing and the beauties of nature, pointing out with their finger various objects, and explaining to those around what the drawing represented. I have often thought that many of these bright Kaffir girls might make good artists with proper training. Mrs Colenso taught some to draw, paint, and play and sing. When they were about sixteen their father came for them, and they, quite delighted, ran off, stripped off their clothes, and went off naked, and never returned, just like some wild pigeons I had once tamed. They are also quite alive to the ridiculous: in the sketch were two horses playing, one standing with his fore-feet in the air; this caught their attention at once, causing great amusement, and imitating their action. They belonged to the Mantatees or Mahowas tribe, which is divided into many kraals under various chiefs, all subject to the head chief Secocoene, who lives on the north of Lydenburg. The Pongola skirts the Swazi, or, as it is sometimes called, the Amaswasiland, a very mountainous country; the people are Zulus, their habits and mode of fighting being the same. Many of these people came to my waggon with milk, which I took in exchange for tobacco and beads. The men are a fine manly race, and the women, many of them, good-looking, but very scanty in their dress, which is only a little strip of beads an inch wide. The Swazi country is situated between the eastern boundary of the Transvaal and the Amatonga, which is the northern part of Zululand, up to the Portuguese settlement in Delagoa Bay on the east side. It is governed by an independent chief, their laws and language being the same as the Zulus. The country has every indication of being rich in gold, some specimens of quartz I obtained from reefs running through the country looked very promising. The Pongola Bush, as it is called, is a beautiful forest of fine timber trees. Some of the most valuable are the Bosch Gorrah, of a scarlet colour, fine grain; Ebenhout, a sort of ebony; Borrie yellow, Bockenhout, no regular grain; Assagaai, used for spear handles; Wild Almond, Grelhout, Saffraan, Stinkwood, Speckerhout, Wild Fig, Umghu, Witgatboom, Tambooti; White Ironwood, very hard, and many others of great use for many purposes. The Pongola river is very pretty; passing down through a richly-wooded district, with its tributaries, flowing east and then north it joins the beautiful river Usutu, which enters the south side of Delagoa Bay. The Usutu river drains the greater portion of the Amaswasiland with its many branches; it rises on the east side of the Veldt and Randsberg, that is the continuation of the watershed from Natal, already described, which separates the waters of the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, some of the springs of the Usutu rising within a few miles of the upper springs of the Vaal, near Lake Crissie. The principal tributaries of the former river are the Umtaloos, Lobombo, Assagaai, Impeloose, Umkonto, and Umkompies, all uniting in the Swazi country; then it flows east, through a beautiful break in the Lobombo Mountains, and enters Delagoa Bay, as before described. For beauty of scenery and picturesque views, with the deep glens, ravines, and thickly wooded kloofs of every variety of tint, few views in Africa will surpass them, and some day, when the country is prospected, if the Swazis will permit it, I believe it will be found to be a rich gold-bearing country, both alluvial and in the quartz. I went several times into the river-beds to prospect, the natives following me, watching my actions, but of course not knowing what I was looking for. As the time was drawing short I left the Pongola, and treked down to Eland’s Neck, where the country was more open, and on a small branch of that river, close to a very pretty waterfall, are many fine tree-ferns, that grow to a great size. Here we were again in the clouds on the Elandsberg, at an elevation of 6000 feet, and overlooking Zululand, with the distant mountain in the background. With my boys to feed—and no small quantity satisfies them—the rifles were in constant use, and in an unknown country it is never safe to go any distance from the waggon without one. The Zulus have no other weapons than the assagai or knobkerrie. Wolves were nightly visitors; several we shot, but not a lion was to be seen or heard. There were many leopards and panthers in the mountains, but they did not trouble us. My driver being a Zulu as well as the other boys, I got on very well with the people at the kraals I passed, and the girls came without any fear. In fact we always got on well with them, having provided myself with brass wire and beads, the principal articles in demand, as clothes they do not wear. They are exceedingly clean in their persons, and very fond of bathing. One afternoon I saddled-up, and started for the open to get a buck. Passing through the bush to the river, I came upon nearly fifty black women bathing in the stream. Some scampered out on the other side, then stood and looked at the white man; the greater number kept in the water splashing about, for it was not deep enough to swim, and laughing and cheering, showing their beautiful white teeth, not in the least afraid. It is true I had been nearly a week outspanned near their two separate kraals, and they were daily at my waggon with milk, so that I was to a certain extent known to them, few white men being seen down so far in that part of Zululand.

November 30th.—It was time to make a move homewards. I therefore prepared for a start, and the following morning took the road towards Natal, stopping at Deepkloof on my way, leaving on the right some very picturesque and lofty hills; not a farm-house to be seen. Having shot plenty of game for the road to last many days, by turning it into biltong, pushed on early the next morning, passing down one of the most stony and difficult passes to be met with in Africa, running against trees, which had to be cut down, breaking one of the oxen’s horns, which had got fixed in the branches of a tree, and with difficulty I saved the waggon from being smashed. The view from this hill, looking west, was very fine, an open plain beneath us with lofty hills on the right and left, open to the south and west, where a distant view of the lofty peaks of the Drakensberg could be seen; the distance in a straight line being over eighty miles; so clear is the atmosphere they did not seem more than half that distance.

The next day about noon I came to a Boer farm, where we procured some milk, a little butter, and some meal. The comfortless manner in which these people live is surprising, and the dirt displayed about the premises would shock many a poor labourer at home. The old Boer asked, which is always the first question put after shaking hands, “What’s your name? where from? what have I up to handel (sell)?” After replying, “Then what’s the news?” This is the usual salutation at every Boer farm, and considering their isolation, a very practical one. Coffee is then handed round, and the tobacco-bag produced, to fill your pipe, as a matter of course. The old Boer complained sadly of the heavy storms that had passed over the country, and loss of cattle from lightning, the old vrow putting in a word occasionally; their three buxom daughters sat on boxes, looking at the stranger as if he were some unknown kind of animal from a strange land.

We crossed a small branch of the Buffalo river, leaving the Belslaberg mountains, covered with bush, on our right. At the back of this range is a mineral spring on the White river, which is a tributary of the Pongola, the water being warm when it issues from the ground.

On the morning of the 4th of December, 1863, I started for Natal, on my backward journey, and treked over an open country in two inspans, and arrived in the evening on the banks of the Buffalo river, which divides Natal from the Zulu country, and outspanned for the night, as I never travel after dark for two reasons: the first, I cannot see the country, and the second, that I always meet with some accident in travelling a road not known—breaking desselboom, axle, or some part of the waggon, sticking in mud-holes that would be avoided in daylight. The Buffalo is a fine stream, rising in the Drakensberg, passing the town of Wakkerstroom, and falling into the Tugela twenty miles below the town of Weenen, where it forms a broad stream to the sea, dividing Zululand from Natal. At the outspan there was a Boer with his waggon waiting to go through, the water being too high to cross; but it was going down, having risen from the heavy rains, and an accident having happened to his waggon by the bullocks turning round when treking in the night, from fright probably by a wild beast, and breaking the desselboom; but on my arrival I found the young Boer and his vrow sitting by their camp-fire, taking their evening coffee, and after the usual shaking of hands was asked to sit, and a Bushman girl was told to give me a cup of coffee; afterwards, of course, a smoke.

Having made my waggon ready for the night, and looked after the boys and oxen, I took my evening meal with John; then walked over to the Boer waggon for a chat, where we remained until bed-time, which was nine o’clock. Sitting listening to the Boer’s various tales of Zulu fighting, and hunting, and other anecdotes, I found he lived on a farm some little distance beyond this outspan; his name was Uys, rather a pleasant kind of man for his class. Probably the father of Piet Uys, the hero of the Zulu war.

The next morning at sunrise I had a look at the river, which was not much lower; but an exciting scene was taking place; a flock of about 300 sheep was being swum through, which occupied all the first part of the morning. I was astonished to see how well they took to the water when they were in, the difficulty lay in getting them in: some would turn back, others go down the river; what with the bleating of the sheep, the shouting of a dozen Kaffir boys and their two Boer masters making a perfect din of sounds; however, with only the loss of two sheep, they got them safely over, and as the water was falling fast, everything was made ready to cross. My friend Uys took the lead. The banks on both sides being very steep, the breaks had to be screwed home to bring the waggons safely down to the water. Each waggon had a forelooper, a Kaffir, to take the fore-tow of the front oxen to keep them straight towards the opposite drift, otherwise they might take it into their heads to go down stream, and all would be lost. On his return from one of his expeditions on the east coast, Mr St. Vincent Erskine, the traveller, on reaching Natal bought a horse, and as he had to swim several rivers he put his journal for safety into a waggon. It was carried down a river, the oxen and a white girl lost, and his journal. Long searches were made for it by numbers of Kaffirs, when the river went down, in vain. Two years afterwards it was found in its tin case, quite legible, being in pencil. It was in a bush so far above the river that no one had thought of looking for it.

We reached the bank safely on the opposite side, which is Natal, and treked on in a westerly course for a few miles, where we outspanned, and then went on again for a long trek, as there was nothing further to delay us, and the next day we continued on to a very pretty opening, close to the river Ineandu; the lofty Drakensberg range on our right, with its beautiful rugged outline, and deep kloofs, was grand to look upon. Game was more plentiful here than we had seen for some time, and we also found lions were not wanting to keep up the excitement during the night-watch. As we arrived late, there was nothing to do but have our fires, cook some tea and a slice of a young springbok over the red embers, with a little salt, mustard, and pepper,—a supper not to be cast on one side. We were rightly informed, and cautioned not to let the oxen and horse stray in the bush, but kept them near and in sight, for lions had considerably increased of late and had done much damage in carrying off oxen when out in the Veldt. Mr Evans, the merchant, once saw forty all together. We therefore made everything fast before going to sleep, and collected wood for fires, if it were necessary to light them during the night. My horse would have been a great loss; he was excellent when out after game, for, on dismounting and throwing the rein over his head to hang on the ground, he would not move from the spot until you returned from following up game where a horse could not go. As there was no moon the night was getting dark, and while we were sitting round the camp-fire, listening to the boys’ tales of some hunting expeditions they had been in, we were reminded that our friends the lions were not far away. In the stillness of night, when all is silent, the sounds made by a lion close at hand in a thick bush surrounding the camp, the deep tones of his growls, make every one start, and look around to see if all is safe, and put more wood on the fires, to throw light into the bush, and take our rifles which had been left in the waggon. Although we could not see them, we knew they were close at hand; others were heard in the distance, and would no doubt come nearer; sleep was out of the question, as a vigilant watch was necessary, in case they might make an attack on our oxen. Wolves also began to enliven the night-air with their sounds, and occasionally a jackal was heard. With the exception of a few scares, when they came too close to the waggon, the night passed off very well, and a lovely bright morning succeeded. We inyoked the oxen, and treked at daylight—saddling up the horse, I rode into the bush, but could see nothing except their footprints in the sand.

From this outspan to Ladysmith occupied five days. The country over which we travelled was very pretty, and in many places hilly. Ladysmith is another small town, where we remained the morning, and then started for the farm, and arrived on the 20th of December, 1863, in time to spend the Christmas with the old people.

Ladysmith is now the terminus of the railway, 180 miles from D’Urban. It is to be continued at once to Newcastle, passing through a rich coal district 100 miles, where it will be only about fifty miles from the nearest gold-fields. Natal only asks the Imperial Government to enable it to borrow the money at three per cent, for this great strategical work, which besides reaching the Transvaal, would afford the only coaling-station in South Africa.

Chapter Three.

Final departure for the unknown land—The happy hunting-ground.

Christmas day, 1863; on the banks of the Tugela river, Natal; 96 degrees in the shade, 149 degrees in the sun; 9:30 a.m.; a cloudless sky, with scarcely a puff of air to relieve the oppressive heat. No greatcoats, thick gloves, mufflers, or snow-boots are needed on Christmas Day in these southern climes. The thinnest of thin clothes, and those but few, can be worn with comfort. I envy the native tribes their freedom from dress in such weather. But so it must be, I suppose; we are but children of circumstances, and must abide by the rules of society. Not always. The celebrated Mr Fynn went naked among the Kaffirs for years, as also did Gordon Cumming.

But with all this glorious sunshine, sultry and Oppressive atmosphere, Christmas is not Christmas as we know it in Old England, where friends meet friends in all the warmth of overflowing love and hospitality round the well-filled board, and the social gatherings round the hearth, with song and dance, and Christmas-tree. We live in its memory when it comes upon us in this far-away land, hoping against hope that at its next anniversary we may be united again with those dear to us, and join in the festivities of merry Christmas in our native land. Father Frost, with his snow-white mantle, is a welcome guest at this season of the year; without him we know not what real Christmas is.

In this warm clime we endeavour to realise that Christmas is upon us, but how can we reconcile the fact with the thermometer at noon standing 106 degrees in the shade, flies, ants, mosquitoes, and countless other insects buzzing round you, fighting after your food and filling the dishes, until you can scarcely make out what is in them! Such is Christmas in a subtropical land.

However, with all these drawbacks, my friends on the farm, who were colonists of eight years standing, did their best to keep up the old customs; their two daughters and one son—all born in England—with myself, and the old people, comprised our little family party. Plum-pudding, mince pies, venison, and fowls were served up in the old style, with good English bottled ale, and sundry fruits afterwards. We managed to pass away Christmas Day with many pledges of good luck and success to all absent friends in glasses of some real old whisky which I had in my waggon. Two Zulu girls attended, with a bunch of long ostrich feathers each, to keep off the flies during meals, otherwise flies as well as food would have passed into the mouth.

But the day was not to terminate as brightly as it commenced. Soon after four p.m. dense clouds were rising over the lofty Drakensberg mountains in heavy massive folds, rising one after the other in quick succession, spreading out, expanding over the clear sky above, enveloping the mountain tops, blending together earth and sky, a grand and beautiful sight, with the quick flashes of lightning and the distant rumble of the thunder. We watched with intense interest and admiration its rapid approach until we were warned by the hurricane that preceded it that the house was the safest place. Having made everything fast without, we waited its arrival. Those who have never witnessed a tropical thunderstorm can have but a faint idea of its violence, and in no place in Africa is it more so than in Natal. They are renowned for their rapid appearance and destructive effects.

(Fourteen soldiers were struck in one room in Natal, some men and two officers on parade another time; whole spans of oxen are often struck, the lightning running along the trek-chain. A woman woke up one morning, and found that her husband had been struck dead by her side without her knowing it.)

At half-past five it was at its height; the lightning was incessant and thunder continuous; the rain falling not in drops but in sheets, flooding everything. Shortly after six it was passing away to the east, the rumbling of the thunder growing fainter, until a calm succeeded, and the sun shone again in all its brightness, and the evening passed away as serenely and calm as if there were no such things as storms, the only evidence left being broken branches of trees, and every hollow full of water. However, this did not prevent our finishing up our Christmas amusements. I arranged to remain here until after the New Year, and prepare for my long journey to regions unknown. A driver and two boys had to be looked up.

On the farm was a middle-aged Hottentot, who had been a driver to a transport rider. Mr Talbot told me I could have him if he would go, being trustworthy as far as blacks can be trusted. When spoken to on the subject he was all eagerness to be engaged, as driving was his legitimate work. Consequently John was engaged forthwith, and told to look out two boys to go with us. He said he knew two good boys in Ladysmith if I would let him go and get them, which I agreed to, and in five days he returned with two very likely lads who were used to waggons and anxious to be engaged—ten shillings a month and food. So far all was settled. The next step was to get my things from Maritzburg; this entailed a waggon journey.