Project Gutenberg's The Minute Man of the Frontier, by W. G. Puddefoot This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Minute Man of the Frontier Author: W. G. Puddefoot Release Date: September 17, 2012 [EBook #40783] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MINUTE MAN OF THE FRONTIER *** Produced by Greg Bergquist, Julia Neufeld and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

FIELD SECRETARY OF THE HOME MISSIONARY SOCIETY

NEW YORK: 46 East 14th Street

THOMAS Y. CROWELL & COMPANY

BOSTON: 100 Purchase Street

Copyright, 1895,

By Thomas Y. Crowell & Co.

TYPOGRAPHY BY C. J. PETERS & SON,

BOSTON.

In a very able review of Maspero's "Dawn of Civilization," the writer says "that for hundreds of years it was believed that history had two eyes; but now we know she has at least three, and that archæology is the third."

This may account for the saying that "history is a lie agreed to;" for it needs to be argus-eyed to give us any adequate idea of the truth; and while the writer of the following sketches does not aspire to the rank of a historian, he has been induced to print them for two or three reasons. First, because urged to by friends; and secondly, because of the unique condition of American frontier[iv] life that is so rapidly passing away forever.

One may read Macaulay, Froude, Knight, and, in fact, a half-dozen histories of England, and then sit down to the gossipy sketches of Sidney culled from Pepys's, Evelyn's, and other diaries, and get a truer view of English life than in all the great histories combined. It would be impossible to give even the slightest sketch of a country so large as ours for a single decade in many volumes; although, in one sense, we are more homogeneous than many suppose.

There was a greater difference in two counties in England before the advent of the railways than between two of our Northern States to-day. To-day a man may travel from Boston to San Francisco, and he will find the same headlines in his morning papers, and for three thousand miles will find the scenery[v] desecrated by the wretched quack medicine advertisements that produce "that tired feeling" which they profess to cure.

If he goes into one county in the mother country, he will find the people singeing the bristles of their swine, and counting by the score, in another by the stone, etc., and customs kept up that had grown settled before travel became general. But with us it is different. We had no time to become crystallized before the iron horse, the great cosmopolitan of the age, rapidly levelled all distinctions; and it is only by getting away from the railway, and into settlements that still retain all the primitiveness of an earlier day, that we find the conditions of which much of this book treats.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface | iii | |

| I. | The Frontier in Relation to the World | 1 |

| II. | Early Reminiscences | 11 |

| III. | The Minute-Man on the Frontier | 22 |

| IV. | The Immigrant on the Frontier | 48 |

| V. | The Oddities of the Frontier | 61 |

| VI. | Lights and Shadows | 68 |

| VII. | Saturday Afternoon in the South | 77 |

| VIII. | All Sorts and Conditions of Men | 82 |

| IX. | The South in Springtime | 91 |

| X. | The North-west | 102 |

| XI. | A Brand New Woods Village | 107 |

| XII. | Out-of-the-Way Places | 123 |

| XIII. | Cockle, Chess, and Wheat | 134 |

| XIV. | Chips from other Logs | 142 |

| XV. | A Trip in Northern Michigan | 151 |

| XVI. | Black Clouds with Silver Linings | 163 |

| XVII. | Sad Experiences | 171 |

| XVIII. | A Sunday on Sugar Island | 180 |

| [viii] | ||

| XIX. | The Needs of the Minute-Man | 189 |

| XX. | The Minute-Man in the Miner's Camp | 197 |

| XXI. | The Sabbath on the Frontier | 211 |

| XXII. | The Frontier of the South-west | 220 |

| XXIII. | Dark Places of the Interior | 227 |

| XXIV. | The Dangerous Native Classes | 235 |

| XXV. | Christian Work in the Lumber-Town | 244 |

| XXVI. | Two Kinds of Frontier | 255 |

| XXVII. | Breaking New Ground | 262 |

| XXVIII. | Sowing the Seed | 270 |

| XXIX. | "Harvest Home" | 277 |

| XXX. | Injeanny vs. Heaven | 285 |

| XXXI. | The Latest Frontier—Oklahoma | 293 |

| XXXII. | The Pioneer Wedding | 318 |

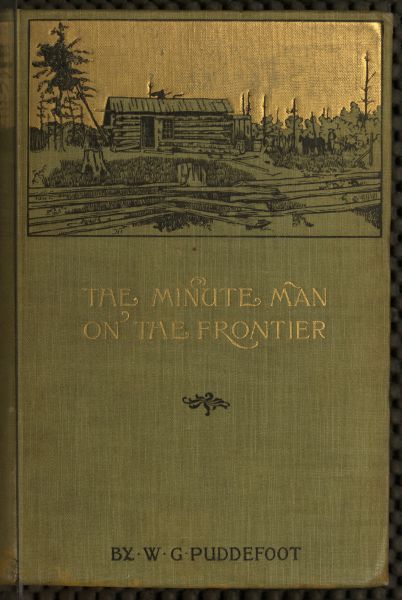

| Portrait of the Author | Frontispiece |

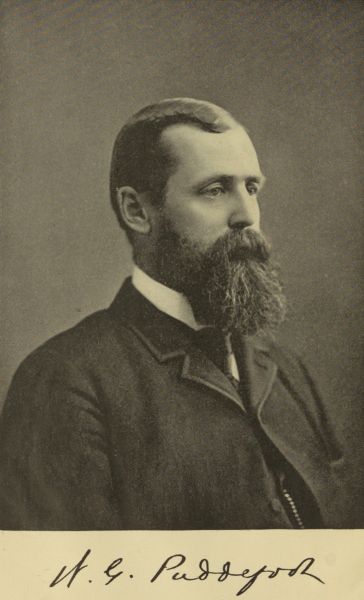

| Indian Camp, Grand Traverse Bay | Page 16 |

| View near Petoskey, Mich. | 20 |

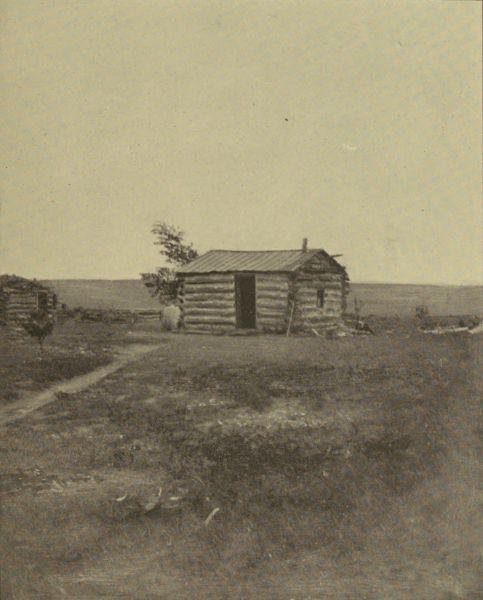

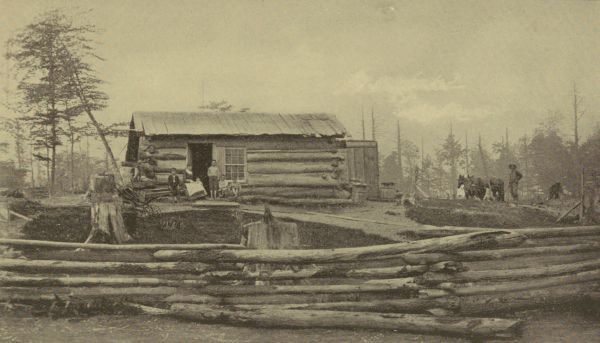

| Typical Log House | 46 |

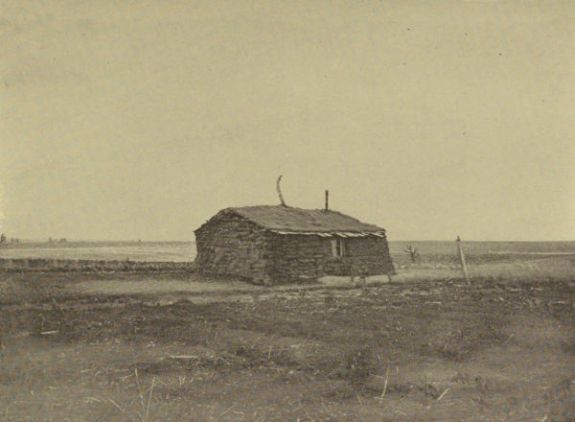

| Typical Sod House | 61 |

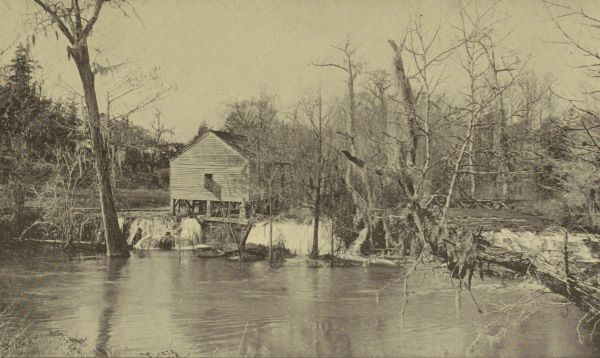

| A Southern Saw-Mill | 91 |

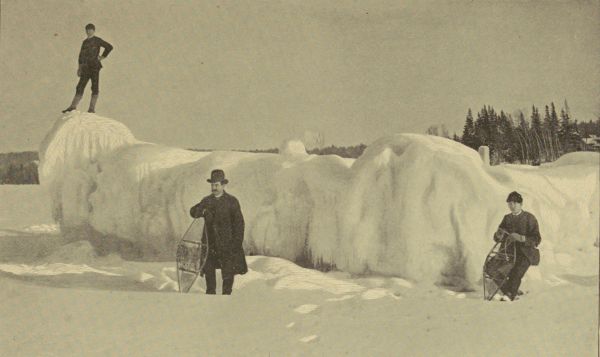

| Winter Scene in Northern Michigan | 127 |

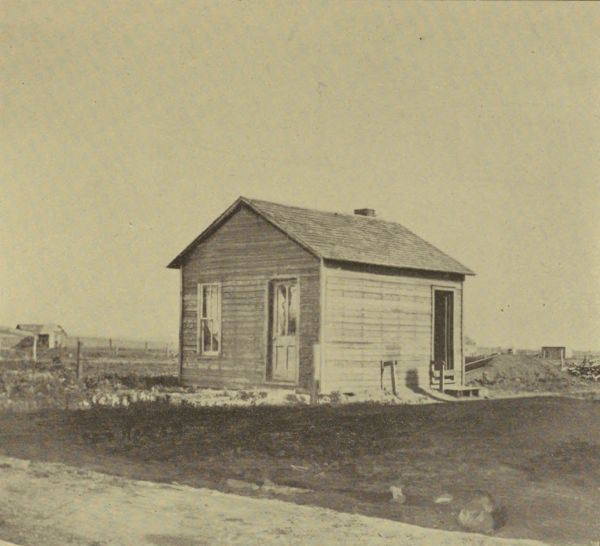

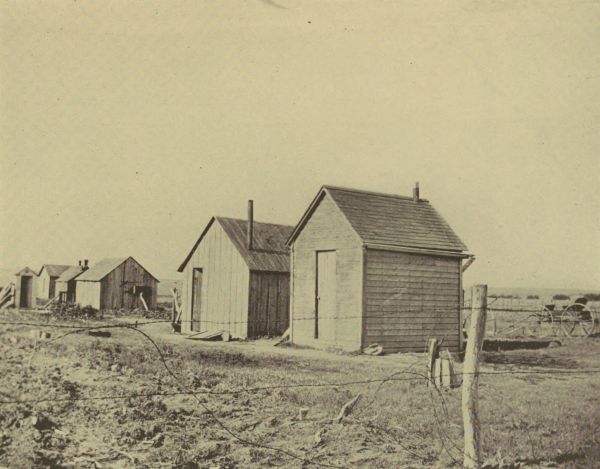

| A Minute Man's Parsonage | 190 |

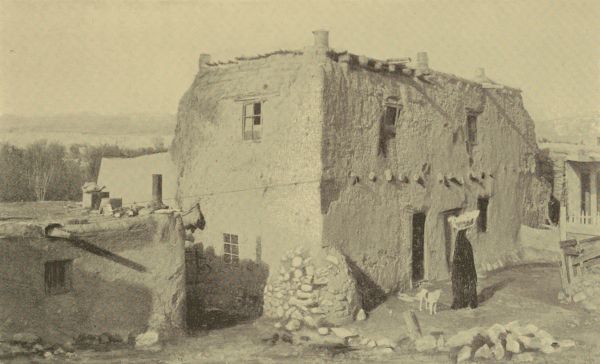

| Oldest House in the United States, Santa Fé, New Mexico | 220 |

| Breaking New Ground | 262 |

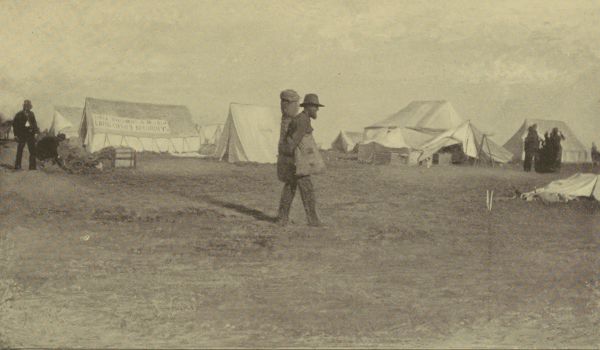

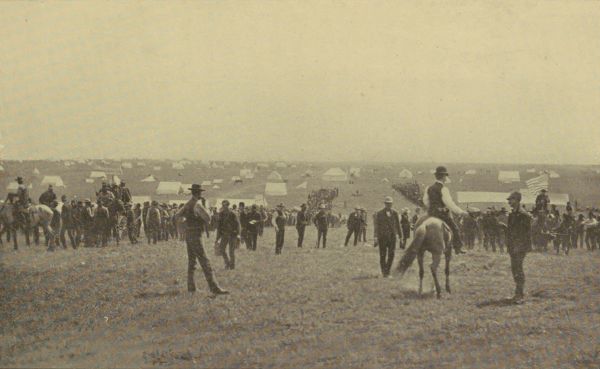

| Looking for a Town Lot | 294 |

| Forming in Line to vote for Mayor | 296 |

| Indians at Pawnee, Oklahoma Ter. | 301 |

| After a Storm, Guthrie, Oklahoma Ter. | 306 |

| First Church and Parsonage, Alva, Oklahoma Ter. | 307 |

| At a Church Dedication | 310 |

The opening up of a new frontier is world-wide in its operations. Minnesota entered the Union as a State in 1858. The putting to practical use the Falls of St. Anthony was felt all over Europe. Thousands of little country mills, nestling amid the trees, and adding to the beauty of the English pastoral scenery, to-day stand idle, the great wheels covered with green moss; and Tennyson's "Miller" becomes a reminiscence. Iowa became a State in 1846, and now leads the world in the production of corn; and although it[2] is a thousand miles from the seaboard, yet through its immense production, and with the cheapening of transportation, we find over seventy thousand Italians emmigrating to this country, as, in spite of low wages, they cannot compete on the plains of Lombardy. (See Wells's "Economic Changes.")—We find that the man at the front can ship from Chicago to Liverpool the product of five acres of grain for less money than the cost of manuring one acre of land in England. (Ibid.)

Every time a new frontier in America is opened, it means both prosperity and disaster. So large are the opportunities, so rich the results, that at first all calculations are upset. Natural gas in the Middle States changes the price of coal in Europe. The finding of a tin-mine is felt in Cornwall and Wales the next day. The opening of the iron-mines in Michigan makes Cornish towns spring up in the upper peninsula, while the finding of ore in desolate places has caused communities to[3] spring up with all the conditions of a cosmopolitan civilization, and we have to-day men living twenty-five miles from trees or grass. But such is the energy of the frontier type, that grass-plats have been carried and planted on the solid rocks, as in Duluth, where hundreds of thousands of dollars are expended in the grading of streets, and the opening of the sewers, all having to be blasted to do the work.

North Dakota was a wilderness of 150,000 square miles, and had not produced a single bushel of wheat for sale, in 1881. In 1886 it produced nearly 35,000,000 bushels; in 1887, 62,553,000. (See Wells's "Recent Economic Changes.") The opening up of these immense territories starts railways from California to Siberia; for, with the Great West competing, Russia is stirred to greater effort. India, with her great commerce with Great Britain, needs a shorter route; and the Suez canal is made. Australia must compete with the Western plains; and great steamers, filled with refrigerators, are constructed for[4] carrying fresh beef. The South American republics respond in return.

The hardy pioneer, ever on the move, explores well nigh impracticable routes in search of precious metals. The inventive mechanic must respond with an engine that can climb anywhere; and in almost inaccessible mountain eyries the eagle is disturbed by the shriek of the locomotive, and the bighorn must take refuge with the bison in the National Park. The news of new mines flies around the world, fortunes are made and lost in a day, and the destinies of nations determined. A great crop starts railways, steamships. Miners, smelting-works, iron and steel, respond. Letters fly across the Atlantic, and returning steamers are filled with eager men and women, who answer the letters in person. Down from the far north, Sweden and Norway have responded with over a million of their children. Great Britain has sent nearly six millions. Germany follows with 4,417,950; Italy, 392,000; France, 315,130; Austria, 304,976; Denmark, 114,[5] 858; Hungary, 141,601; Switzerland, 167,203; Russia and Poland, 326,994; Netherlands, 99,516; and so on: in all, a total for Europe in fifty years of over 13,000,000, the great majority of whom have been started from their homes by the opening up of new frontiers.

It has been stated on good authority, that sixty per cent of the Germans that come are between the ages of fifteen and forty, while all Germany has only thirty per cent of that age.

On the authority of Dr. Farr, quoted by R. Mayo Smith in his "Emigration and Immigration," he calculates the money value of the immigrants from the British Isles from 1837 to 1876 reached the enormous sum of 1,400,000 pounds sterling, or 7,000,000,000 of dollars, an average of 175,000,000 dollars a year; while the amount sent back from British North America and the United States since 1848 was but £32,294,596. And what has been produced by the immigrant and exported amounts to many hundred millions[6] of dollars. It has been computed that the country has been pushed forward a quarter of a century by this vast mass of immigrants, nearly all of whom labor for a living.

The frontiers of America will yet change the world. When in the not distant future hundreds of millions cover the great continent, dotted with schools and churches, and an intelligent population speaking one language, and with other millions in Africa, Australia, and the islands of the sea, using the same language, the time will come when they will arbitrate for the world, and war shall be no more. Long before the Atlantic cable was stretched across the ocean, millions of heartstrings were vibrating from this land to all parts of Europe; and to-day the letters fly homeward from the frontier immigrants in their sod houses, bearing good cheer in words and money.

The freedom of the frontier is contagious, and the poor European strives harder than ever to reach his kin across[7] the sea. And when we consider that only 300,000 square miles out of 1,500,000 miles of arable land is under cultivation, and that already the farmers of England and most parts of Europe are being pushed to the wall, we begin to realize that the growth of the frontiers of the United States not only influences our own land, but changes materially the course of events in the whole world. The above figures are by Mr. Edward Atkinson, as quoted in substance from "Recent Economic Changes."

To show the growth of one State during the past fifty years, let us take Michigan. In 1840 Michigan had a population of 212,267; in 1890, 2,093,889. In 1840 there were three small railroads, with a total mileage of 59 miles. In 1890 there were over 7,000 miles. "In 1840 [I quote from Hon. B. W. Cutcheon, in "Fifty Years' Growth in Michigan"] mining had not begun. In 1890 over 7,000,000 tons of iron were shipped from her mines; while the output of copper had reached[8] over a 100,000,000 lbs., and valued at $15,845,427.28. The salt industry, a late one, rose from 4,000 bbls. in 1860 to 3,838,937 bbls. in 1890; while the value of her lumber products for 1890 was over $55,000,000. In 1840 there were neither graded nor high schools, normal schools nor colleges. In 1890, 654,502 children were of school age, with an enrolment of 427,032, with 33,975 additional attending private schools. These children were taught by 15,990 teachers, who received in salaries $3,326,287."

In 1840 Michigan had 30,144 horses and mules, 185,190 neat cattle, 99,618 sheep. In 1890 there were 579,896 horses, 3,779 mules, of milch cows 459,475, oxen and other cattle 508,938, of sheep 2,353,779, of swine 893,037. The total value came to $74,892,618. Over 1,700 men are engaged in the fisheries, with nearly a million dollars invested, with a total yield of all fish of 34,490,184 lbs., valued at over a million and a half of dollars. The value of her apples and[9] peaches in 1890 was $944,332; of cherries, pears, and plums, $65,217; of strawberries, $166,033; of other berries, $267,398; and of grapes, $122,394. The wheat crop for 1891 was valued at $27,486,910; the oats at $9,689,441; besides 811,977 bushels of buckwheat, and 2,522,376 bushels of barley. The capital invested in lumber alone was $111,302,797. "While her great University, which saw its first student in 1841, and which had but three teachers, one of them acting as president, has grown to be one of the largest in the nation, with eighty professors and instructors and 2,700 students registered on her rolls, conferring 623 degrees upon examination." And all this but the partial record of fifty years in one State.

Since Michigan was entered as a State fourteen new States have been formed (not counting Texas) and three Territories, with an aggregate of over 17,000,000 square miles of land, and a population of nearly 15,000,000, nearly all of which[10] fifty years ago was wilderness, the home of the Indian and the wild beasts. With such stupendous changes in so short a time, we see that the American frontiers have a direct and powerful influence in changing the histories and destinies of the nations of the whole world.

It was in the spring of 1859 that I first saw the frontier. Our way was over the New York Central, very little of which had two tracks. I have a very vivid recollection of the worm fences, the log houses, and the great forests that we passed on our way to Upper Canada. I remember the hunters coming towards the train with their moccasons on and the bucks slung over their shoulders. I have since that time seen many men who were the first to cut a tree in this county or that town. There were about forty thousand miles of railway in the whole land at that date, against nearly two hundred thousand miles to-day. Cities which are now the capitals of States were the feeding-ground of buffalo; wolves and black bears had[12] their dens where to-day we can see a greater miracle in stone than Cheops; i.e., a stone State House built inside the appropriation! Then six miles of travel on the new roads smashed more china than three thousand miles by sea and rail. The little towns were but openings in a forest that extended for hundreds of miles. The best house in the village without a cellar; roots were kept in pits. Houses could be rented for two dollars per month, where to-day they are twelve dollars. Pork was two dollars a hundred; beef by the quarter, two and one-half cents a pound; potatoes, fifteen cents a bushel. Men received seventy-five cents a day for working on the railroad. Cord-wood was two dollars a cord; and you could get it cut, split, and piled for fifty cents a cord. Men wore stogy boots, generally with one leg of the trousers outside and one in. Blue denham was the prevailing suit for workingmen. The shoemaker cut his shoes, and they were sent out to be[13] bound by women. The women wore spring-heeled shoes, print dresses, and huge sunbonnets; and in the summer-time the settlers went barefooted. The roads were simply indescribable. When a tree fell, it was cut off within an inch of the ruts; the wagon would sink to the hubs, and need prying out with poles; harnesses were never cleaned, and boot-blacking had no sale. But the schoolhouse was in every township. In the older settlements could be seen the log hut in which the young couple started housekeeping, then a log house of more pretentious size; the frame-house which followed, and a fine brick house where the family now lived, showing the rapid progress made.

This was in western Canada. Toronto was separated from Yorkville, but was a busy, substantial city. I remember the stores being closed when Lincoln was buried, and black bunting hung along the principal streets. I remember, too, the men who were loudest in their curses[14] at the government and against Lincoln, how the tears came to their eyes, and how that event brought them to their senses. Most of them were shoemakers from New England.

In 1873 I crossed into Michigan with my family. Even as late as that the greater part of northern Michigan, and especially the upper peninsula, was terra incognita to most of the people of that State. The railroads stopped at a long distance this side the Straits of Mackinaw. The lumbermen had but skimmed the best of the trees; and, with the exception of a few isolated settlements on the lakes and up the larger rivers, it was an unbroken wilderness, abounding in fish, deer, bears, wolves, and wild-cats; in fact, a hunter's paradise, as it is even to this day.

But with the extension of the railways to the Straits of Mackinaw, and the opening of new lines to the north into the iron mines of Menominee to the Gogebic range, the great copper mines of the Keweenaw[15] peninsula, and the ever-increasing traffic of the lakes, the changes were simply marvellous. Some things I shall say will seem paradoxical, but they are nevertheless true to life.

The greater parts of southern Michigan and southern Wisconsin were settled by people from New York State; and long before the northern parts of Michigan and Wisconsin were opened up, new States had risen in the West, and the tide of immigration swept past towards new frontiers, leaving vast frontiers behind them. Sometimes a few stray men with money at their command would pierce the country and form a settlement, as in the case of Traverse City. Here for years the mail was brought by the Indians on dog-sledges in the winter. It took eight days to reach Grand Rapids on snow-shoes. It is four hundred miles by water to Chicago. Sometimes the winters were so long that the provisions had to be dealt out very sparingly; but all the time the little colony was growing, and when at last the railroads reached it,[16] the traveller, after riding for miles through virgin forests, would come upon a little city of four thousand people, with good churches, fine schools, and one store that cost one hundred thousand dollars to build.

If it chanced to be summer-time he would see the tepees of the Indians along the bay, and two blocks back civilized homes with all the conveniences and luxuries of modern life. Here a huge canoe made of a single log, and there a mammoth steamer with all the elegances of an ocean-liner. Should he go on board of one of the steamers coasting around the lakes with supplies, he would pass great bays with lovely islands, and steam within a stone's throw of a comparatively rare bird, the great northern diver, and suddenly find himself near a wharf with a village in sight—a great saw-mill cutting its hundreds of thousands of feet of lumber a day; and near by, Indian graves with the food still fresh inside, and a tame deer with a collar and bell around its neck trotting around the streets.

INDIAN CAMP, GRAND TRAVERSE BAY, MICHIGAN.

INDIAN CAMP, GRAND TRAVERSE BAY, MICHIGAN.He can sit and fish for trout on his doorstep that borders the little stream, or he can get on the company's locomotive and run twenty miles back into the woods and see the coveys of partridges rising in clouds, and here and there a timid doe and her fawn, whose curiosity is greater than their fears, until the whistle blows, and they are off like a shot into the deep forest, near where the black bear is munching raspberries in a ten-thousand-acre patch, while millions of bushels of whortleberries will waste for lack of pickers. He can sit on a point of an inland lake and catch minnows on one side, and pull up black bass on the other; and if a "tenderfoot" he will bring home as much as he can carry, expecting to be praised for his skill. He is mortified at the request to please bury them. He will ride over ground that less than fifteen years ago could be bought for a song and to-day produces millions, and is dotted with towns and huge furnaces glowing night and day.

[18]If in the older settled parts, he will ride through cornfields whose tassels are up to the car windows, where the original settler paddled his skiff and caught pickerel and the ague at the same time, and who is still alive to tell the story. He can talk with a man who knew every white man by name when he first went there, and remembers the Indian peeping in through his log-cabin window, but whose grandchildren have graduated from a university with twenty-seven hundred students, where he helped build the log schoolhouse; who remembers when he had to send miles for salt, and yet was living over a bed of it big enough to salt the world down.

He had nothing but York State pumpkins and wild cranberries for his Thanksgiving dinner, with salt pork for turkey; and he lives to-day in one of the great fruit belts of the world, and ships his turkeys by the ton to the East; and to-day in the North the same experience is going on. Places where the mention of[19] an apple makes the teeth water, and where you can still see them come wrapped in tissue paper like oranges, and yet, paradoxical as it may seem, you can enter a lumber-camp and find the men regaled on roast chicken and eating cucumbers before the seed is sown in that part of the country.

Here are farms worth over eighty thousand dollars, which but a few years ago were entered by the homesteader who had to live on potatoes and salt, and cut wild hay in summer, and draw it to town on a cedar jumper, in order to get flour for his hungry children. Here on an island are men living who used to leave their farming to see the one steamer unload and load, or watch a schooner drawn up over the Rapids, and who now see sweeping by their farms a procession of craft whose tonnage is greater than all the ocean ports of the country.

I have sat on the deck of a little steamer and drawn pictures for the Indians, who took them and marched off[20] with the smile of a schoolboy getting a prize chromo, and in less than five years from that time I have at the same place sat down in a hotel lighted with electricity, and a menu equal to any in the country, with a bronze portrait of General Grant embossed on the top. Within ten years I have preached, with an Indian chief for an interpreter, in a log house in which a half-brother of Riel of North-Western fame was a hearer, where to-day there are self-supporting churches and flourishing schools.

Less than sixteen years ago I stopped at the end of the Michigan Central Railway, northern division; every lot was filled with stumps. A school was being rapidly built, while the church had a lot only. The next time I visited the town it had fine churches and schools. The hotel had a beautiful conservatory filled with choice flowers. I could take my train, pass on over the Straits of Mackinaw, on by rail again, and clear to the Pacific, with sleeper and dining-car attached.

VIEW NEAR PETOSKEY, MICHIGAN.

VIEW NEAR PETOSKEY, MICHIGAN.But once leave your railway, and soon you can get to settlements twenty years old which saw the first buggy last year come into the clearings. Here are deep forests where the preacher on his way home from church meets the panther and the wild-cat, and where as yet he must ford the rivers and build his church, the first in nine thousand square miles.

The minute-men at the front are the nation's cheapest policemen; and strange as it may seem, these men stand in vital relations to all the great cities of the country from which they are so far removed. It is a well-known fact that every city owes its life and increase to the fresh infusion of country blood, and it depends largely on the purity of that blood as to what the moral condition of the city shall be. Therefore it is of the utmost importance that Zion's watchmen shall lift up their voices day and night, until not only the wilderness shall be glad because of them, but that the city's walls may be named Salvation and her gates Praise.

Let us make the rounds among our minute-men to see how they live and what they do. Our road leads along the Grand[23] Rapids and Indiana Railway. All day long we have been flitting past new towns, and toward night we plunge into the dense forests with only here and there an opening. The fresh perfume of the balsam invades the cars, the clear trout-streams pass and repass under the track, a herd of deer scurry yonder, and once we see a huge black bear swaying between two giant hemlocks.

At eleven P.M. we leave the train. There is a drizzling rain through which we see a half-dozen twinkling lights. As the train turns a curve we lose sight of its red lights, and feel we have lost our best friend. A little boy, the sole human being in sight, is carrying a diminutive mail-bag. The sidewalk is only about thirty-six feet long. Then among the stumps we wind our slippery way, and at last reach the only frame house for miles. To the north and east we see a wilderness, with here and there a hardy settler's hut, sometimes a wagon with a cover and the stump of a stove-pipe sticking through the top.

[24]After climbing the stairs, which are destitute of a balustrade, we enter our room. It is carpeted with a horse-blanket. Starting out with a lumber wagon next morning, with axes and whip-saw, we hew our way through the forest to another line of railway, and returning, are asked by the people in the settlement, "Will it ever be settled?" "Could a man raise apples?" "Snow too deep?" "Mice girdle all the trees, eh?" etc.

Five years later, on a sleeping-car, we open our eyes in the morning, and what a change! The little solitary stations that we passed before are surrounded with houses. White puffs of steam come snapping out from factories. A weekly paper, a New York and Boston store, and the five- and ten-cent counter store are among the developments. Our train sweeps onward, miles beyond our first stop; and instead of the lonely lodging-house, palatial hotels invite us, bands of music are playing, the bay is a scene of magic, here a little naphtha launch, and there a steam[25] yacht, and then a mighty steamer that makes the dock cringe its whole length as she slowly ties up to it.

Night comes on, but the woods are as light as day with electric lights. Rustic houses of artistic design are on every hand. Here, where it was thought apples could not be raised because of mice and deep snow, is a great Western Chautauqua.

Eighty thousand people are pushing forward into the northern counties of this great State. Roads, bridges, schoolhouses,—all are building. Most of the settlers are poor, sometimes having to leave part of their furniture to pay freight. They are from all quarters of our own and other lands. Here spring up great mill towns, mining towns, and county seats; and here, too, our minute-man comes. What can he do? Nearly all the people are here to make money. He has neither church, parsonage, nor a membership to start with. Here he finds towns with twenty saloons in a block, opera house and electric plants, dog-fights, men-fights, no Sabbath but[26] an extra day for amusements and debauchery.

The minute-man is ready for any emergency; he takes chances that would appall a town minister. He finds a town without a single house that is a home; he has missed his train at a funeral. It is too cold to sleep in the woods, and so he walks the streets.

A saloon-keeper sees him. "Hello, Elder! Did ye miss yer train? Kind o' tough, eh?" with a laugh. "Well, ye ken sleep in the saloon if ye ken stand it." And so down on the floor he goes, comforting himself with the text, "Though I make my bed in hell, behold, thou art there."

Another minute-man in another part of the country finds a town given up to wickedness. He gets his frugal lunch in a saloon, the only place for him.

"Are you a preacher?"

"Yes."

"Thought so. You want to preach?"

"I don't know where I can get a hall."

[27]"Oh, stranger, I'll give ye my dance-hall; jest the thing, and I tell ye we need preaching here bad."

"Good; I will preach."

The saloon man stretches a large piece of cotton across his bar, and writes,—

"Divine service in this place from ten A.M. to twelve to-morrow. No drinks served during service."

It is a strange crowd: there are university men, and men who never saw a school. With some little trembling the minute-man begins, and as he speaks he feels more freedom and courage. At the conclusion the host seizes his big hat, and with a revolver commences to take up a collection, remarking that they had had some pretty straight slugging. On the back seats are a number of what are called five-cent-ante men; and as they drop in small coin, he says,—

"Come, boys, ye have got to straddle that."

[28]He brings the hat to the parson, and empties a large collection on the table.

"But what can I do with these colored things?"

"Why, pard, them's chips; every one redeemable at the bar in gold."

Sometimes the minute-man has a harder time. A scholarly man who now holds a high position in New England was a short time since in a mountain town where he preached in the morning to a few people in an empty saloon, and announced that there would be service in the same place in the evening. But he reckoned without his host. By evening it was a saloon again in full blast. Nothing daunted, he began outside.

The men lighted a tar-barrel, and began to raffle off a mule. Just then a noted bravo of the camps came down; and quick as a flash his shooting-irons were out, and with a voice like a lion he said,—

"Boys, I drop the first one that interferes with this service."

[29]Thus under guard from unexpected quarters, the preacher spoke to a number of men who had been former church-members in the far East.

Often these minute-men must build their own houses, and live in such a rough society that wife and children must stay behind for some years. One minute-man built a little hut the roof of which was shingled with oyster-cans. His room was so small that he could pour out his coffee at the table, and without getting up turn his flapjacks on the stove. A travelling missionary visiting him, asked him where he slept. He opened a little trap-door in the ceiling; and as the good woman peered in she said,—

"Why, you can't stand up in that place!"

"Bless your soul, madam," he exclaimed, "a home missionary doesn't sleep standing up."

Strapping a bundle of books on his shoulders, this minute-man starts out[30] on a mule-trail. If he meets the train, he must step off and climb back. He reaches the distant camp, and finds the boys by the dozen gambling in an immense saloon. He steps up to the bar and requests the liberty of singing a few hymns. The man answers surlily,—

"Ye ken if ye like, but the boys won't stand it."

The next minute a rich baritone begins, "What a friend we have in Jesus," and twenty heads are lifted. He then says,—

"Boys, take a hand; here are some books." And in less than ten minutes he has a male choir of many voices. One says, "Pard, sing number so and so;" and another, "Sing number so and so." By this time the saloon-keeper is growling; but it is of no use; the minister has the boys, and starts his work.

In some camps a very different reception awaits him, as, for instance, the following: At his appearance a wild-looking[31] Buffalo-Bill type of man greeted him with an oath and a pistol levelled at him.

"Don't yer know thar's no luck in camp with a preacher? We are going to kill ye."

"Don't you know," said the minute-man, "a minister can draw a bead as quick as any man?" The boys gave a loud laugh, for they love grit, and the rough slunk away. But a harder trial followed.

"Glad to see ye, pard; but ye'll have to set 'em up 'fore ye commence—rule of the camp, ye know." But before our man could frame an answer, the hardest drinker in the crowd said,—

"Boys, he is the fust minister as has had the sand to come up here, and I'll stand treat for him."

It is a great pleasure to add that the man who did this is to-day a Christian.

One man is found on our grand round, living with a wife and a large family in a church. The church building[32] had been too cold to worship in, and so they gave it to him for a parsonage. The man had his study in the belfry, and had to tack a carpet up to keep his papers from blowing into the lake. This man's life was in constant jeopardy, and he always carried two large revolvers. He had been the cause of breaking up the stockade dens of the town, and ruffians were hired to kill him. He seemed to wear a charmed life—but then, he was over six feet high, and weighed more than two hundred pounds. Some of the facts that this man could narrate are unreportable.

The lives lost on our frontiers to-day through sin in all its forms are legion, and no man realizes as well as the home missionary what it costs to build a new country; on the other hand, no man has such an opportunity to see the growth of the kingdom.

There died in Beloit, recently, the Rev. Jeremiah Porter, a man who had been a[33] home missionary. His field was at Fort Brady before Chicago had its name. His church was largely composed of soldiers; and when the men were ordered to Fort Dearborn, he went with them, and organized what is now known as the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago. This minute-man lived to see Chicago one million two hundred thousand strong.

We should have lost the whole Pacific slope but for our minute-man, the glorious and heroic Whitman, who not only carried his wagon over the Rockies, but came back through stern winter and past hostile savages, and by hard reasoning with Webster and others secured that vast possession for us. As a nation we owe a debt we can never repay to the soldiers of the cross at the front, who have endured (and endure to-day) hardships of every kind. They are cut off from the society which they love; often they live in dugouts, sometimes in rooms over a saloon; going weeks without fresh meat, sometimes suffering from hunger, and for a long time[34] without a cent in the house. Yet who ever heard them complain? Their great grief is that fields lie near to them white for the harvest, while, with hands already full, they can only pray the Lord of the harvest to send forth more laborers.

Often there is but one man preaching in a county which is larger than Massachusetts. He is cut off from libraries, ministers' meetings, and to a large extent from the sympathies of more fortunate brethren, and is often unable to send his children to college. These men still stand their ground until they die, ofttimes unknown, but leaving foundations for others to build on.

One place visited by a general missionary was so full of reckless men that the station-agent always carried a revolver from his house to the railway station. A vile variety show, carried on by abandoned women, was kept open day and night. Sunday was the noisiest day of all. Yet in this place a church was formed; and many men and women, having found a[35] leader, were ready to take a stand for the right.

I am not writing of the past; for all the conditions that I have spoken of exist in hundreds, yes, thousands, of places all over the land. One need not go to the far West to find them; they exist in every State of the Union, only varying in their types of sin.

Visiting a home missionary in a mining region within two hours' ride of the capital, in a State not four hundred miles from the Atlantic, I found the man in one of the most desolate towns I ever saw. The most prosperous families were earning on an average five dollars a week, store pay. All were in debt. When the missionary announced his intention of going there, he was warned that it was not safe; but that did not alter his plans.

The first service was held in a schoolhouse, the door panels of which were out and not a pane of glass unbroken. A roaring torrent had to be passed on an[36] unsteady plank bridge, over which the women and children crawled on hands and knees. It was dark when they came. The preacher could see the gleam of the men's eyes from their grimy faces as the lanterns flickered in the draughts. He began to preach. Soon white streaks were on the men's cheeks, as tears from eyes unused to weeping rolled down those black faces. At the close a church was organized, a reading-room was added, and many a boy was saved from the saloon by it. Yet, strange to say, although the owners (church members too) had cleared a million out of those mines, the money to build the needed church and parsonage had to be sent from the extreme East.

Hundreds of miles eastward I have found men living, sixty and seventy in number, in a long hut, their food cooked in a great pot, out of which they dipped their meals with a tin dipper. No less than seventy-five thousand Slovaks live in this one State, and their only spiritual[37] counsel comes from a few Bible-readers. Ought we not then, as Christians, to help those already there, and give of our plenty to send the men needed to carry the light to thousands of places that as yet sit in the darkness and the shadow?

HOW THE HOME MISSIONARY BEGINS WORK IN THE NEW COMMUNITY.

First, pastoral visiting is absolutely necessary to success. The feelings of newcomers are tender after breaking the home ties and getting to the new home, and a visit from the pastor is sure to bring satisfactory results. Sickness and death offer him opportunities for doing much good, especially among the poor, and they are always the most numerous.

Some very pathetic cases come under every missionary's observation. Once a man called at the parsonage and asked for the elder, saying that a man had been killed some miles away in the woods, and the family wanted the missionary to preach[38] the funeral sermon. The next morning a ragged boy came to pilot the minister. The way led through virgin forests and black-ash swamps. A light snow covered the ground and made travelling difficult, as much of the way was blocked by fallen trees. After two hours' walking the house was reached; and here was the widow with her large family, most of them in borrowed clothes, the supervisor, a few rough men, and a county coffin.

The minister hardly knew what to say; but remembering that that morning a large box had been sent containing a number of useful articles, he made God's providence his theme. A few days after, the box was taken to the widow's home. When they reached the shanty they found two little bunks inside. Her only stove was an oven taken from an old-fashioned cook-stove. The oven stood on a dry-goods box.

The missionary said, "Why, my poor woman, you will freeze with this wretched fire."

[39]"No," she said; "it ain't much for cooking and washing, but it's a good little heater."

A few white beans and small potatoes were all her store, with winter coming on apace. When she saw the good things for eating and wearing that had been brought to her, she sobbed out her thanks.

In the busy life of a missionary the event was soon forgotten, until one day a woman said, "Elder, do you recollect that 'ar Mrs. Sisco?"

"Yes."

"She is down with a fever, and so are her children."

At this news the minister started with the doctor to see her. As they neared the place he noticed some red streaks gleaming in the woods, and asked what they were.

"Oh," said the doctor, "that is from the widow's house. She had to move into a stable of the deserted lumber camp."

The chinks had fallen out from the[40] logs, and hence the gleam of fire. The house was a study in shadows—the floor sticky with mud brought in with the snow; the débris of a dozen meals on the table; a lamp, without chimney or bottom, stuck into an old tomato-can, gave its flickering light, and revealed the poor woman, with nothing to shield her from the storm but a few paper flour-sacks tacked back of the bed. Two or three chairs, the children in the other bed, the baby in a little soapbox on rockers, were all the wretched hovel contained. Medicine was left her, and the minister's watch for her to time it. He exchanged his watch for a clock the next day. By great persuasion the proper authorities were made to put her in the poorhouse, and she was lost to sight; but there was a bright ending in her case.

About a year after, a rosy-faced woman called at the parsonage. The pastor said, "Come in and have some dinner."

"I got some one waiting," she said.

"Why, who is that?"

"My new man."

[41]"What, you married again?"

"Yes; and we are just going after the rest of the traps up at the shanty, and I called to see whether you would give me the little clock for a keepsake?"

"Oh, yes."

Away she went as happy as a lark. Less than two years from the time she was left a widow, a rich old uncle found in her his long-lost niece, and the woman became heiress to thousands of dollars.

Sometimes dreadful scenes are witnessed at funerals where strong drink has suddenly finished the career of father or mother. At the funeral of a little child smothered by a drunken father, the mother was too sick to be up at the funeral, the father too drunk to realize what was taking place, and twice the service was stopped by drunken men. At another funeral a dog-fight began under the coffin. The missionary kicked the dogs out, and resumed as well as he could.

At another wretched home the woman was found dying, the husband drunk, no[42] food, mercury ten degrees below zero, and the little children nearly perishing with cold. The drunken man pulled the bed from under his dying wife while he went to sleep. His awakening was terrible, and the house crowded at the funeral with morbid hearers.

In one town visited, a county town at that, the roughs had buried a man alive, leaving his head above ground, and then preached a mock funeral sermon, remarking as they left him, "How natural he looks!"

As the nearest minister is miles away, the missionary has to travel many miles in all weathers to the dying and dead. Visiting the sick, and sitting up with those with dangerous diseases, soon cause the worst of men not only to respect but to love the missionary; and no man has the moulding of a community so much in his hands as the courageous and faithful servant of Christ. The first missionary on the field leaves his stamp indelibly fixed on the new village. Towns left without[43] the gospel for years are the hardest of all places in which to get a footing. Some towns have been without service of any kind for years, and some of the young men and women have never seen a minister. There are townships to-day, even in New York State, without a church; and, strange as it may seem, there are more churchless communities in Illinois than in any other State in the Union. Until two years ago Black Rock, with a population of five thousand, had no church or Sunday-school. Meanwhile such is the condition of the Home Missionary Society's treasury that they often cannot take the students who offer themselves, and the churchless places increase.

All kinds of people crowd to the front,—those who are stranded, those who are trying to hide from justice, men speculating. Gambling dens are open day and night, Sundays of course included, the men running them being relieved as regularly as guards in the army.

In purely agricultural districts a different[44] type is met with. Many are so poor that the men have to go to the lumber woods part of the year. The women thus left often become despondent, and a very large per cent in the insane asylum comes from this class.

One family lived so far from town that when the husband died they were obliged to make his coffin, and utilized two flour-barrels for the purpose.

So amid all sorts and conditions of men, and under a variety of circumstances, the minute-man lives, works, and dies, too often forgotten and unsung, but remembered in the Book; and when God shall make up his jewels, some of the brightest gems will be found among the pioneers who carried the ark into the wilderness in advance of the roads, breaking through the forest guided by the surveyor's blaze on the trees.

There are hundreds of people who pierce into the heart of the country by going up the rivers before a path has been made. In one home found there,[45] the minute-man had the bed in a big room down-stairs, while the man, with his wife and nine children, went up steps like a stable-ladder, and slept on "shakedowns," on a floor supported with four rafters which threatened to come down. But the minute-man, too tired to care, slept the sleep of the just. Often not so fortunate as then, he finds a large family and but one room. Once he missed his way, and had to crawl into two empty barrels with the ends knocked out. Drawing them as close together as he could, to prevent draughts, he had a short sleep, and awoke at four A.M. to find that a house and bed were but twenty rods farther.

In a new village, for the first visit all kinds of plans are made to draw the people out. Here is one: The minute-man calls at the school, and asks leave to draw on the blackboard. Teacher and scholars are delighted. After entertaining them for a while, he says, "Children, tell your parents that the man who chalk-talked to you will preach here at eight o'clock."[46] And the youngsters, expecting another such good time as they have just enjoyed, come out in force, bringing both parents with them. The village is but two years old. At first the people had the drinking-water brought five miles in barrels on the railroad, and for washing melted the snow. Then they took maple sap, and at last birch sap; but, "Law," said a woman, "it was dreadful ironin'!"

A TYPICAL LOG HOUSE.

A TYPICAL LOG HOUSE.Here was a genuine pioneer: his house of logs, hinges wood, latch ditto, locks none; a black bear, three squirrels, a turtle-dove, two dogs, and a coon made up his earthly possessions. He was tired of the place.

"Laws, Elder! when I fust come ye could kill a deer close by, and ketch a string of trout off the doorsteps; but everything's sp'iled. Men beginning to wear b'iled shirts, and I can't stand it. I shall clear as soon as I can git out. Don't want to buy that b'ar, do ye?"

In this little town a grand minute-man laid down his life. He was so anxious to[47] get the church paid for, that he would not buy an overcoat. Through the hard winter he often fought a temperature forty degrees below zero; but at last a severe cold ended in his death. His good wife sold her wedding-gown to buy an overcoat, but all too late; and a bride of a twelvemonth went out a widow with an orphan in her arms.

Yet the children of God are said to add to their already large store four hundred million dollars yearly, and some think of building a ten-million-dollar temple to honor God—while temples of the Holy Ghost are too often left to fall, through utter neglect, because we withhold the little that would save them. We shall never conquer the heathen world for Christ until we have learned the way to save America. Save America, and we can save the world.

Whatever may be the effect of immigrants in cities, the immigrant on the frontier has sent the country ahead a quarter of a century. In the first place, the pioneer immigrants are in the prime of life. They generally bring enough money to make a start. They need houses, tools, horses, and all the things needful to start. They seldom fail. Used to privation at home, they make very hardy settlers. In some States they comprise seventy per cent of the voters; and the getting of a piece of land they can call their own makes good citizens of them sooner than any other way. You can't make a dangerous kind of a man of him who can call a quarter section his own.

In order to show how the pioneer settler[49] from Europe prospers, let us begin with him at the wharf. There floats the leviathan that has a whole villageful on board,—over twelve hundred. They are on deck; and a motley crowd they appear, for they are from all lands. Here is a girl dressed in the picturesque costume of Western Europe, and here a man with a great peak to his hat, an enormous long coat, his beard half way down his breast, a china pipe as big as a small teacup in his mouth, his wife like a bundle of meal tied in the middle, with immense earrings, and an old colored handkerchief over her head. Behind them a half-dozen little ones with towheads of hair, looking as shaggy as Yorkshire terriers, blue-eyed and healthy. They are carrying copper coffee-pots and kettles; and away they march, eight hundred of them and more, up Broadway.

Here and there a man steps into a bakery, and comes out with a yard of bread, and breaks it up into hunks; and the little children grind it down without[50] butter, with teeth that are clean from lack of meat, with all the gusto of Sunday-school children with angel-cake at a picnic. They are soon locked in the cars, and night comes on. Go inside and you will see the good mother slicing up bolognas or a Westphalia ham, and handing around slices of black bread. After supper reading of the Bible and prayers; and then the little ones are put into sack-like nightgowns, and put up in the top bunks, where they lie, watching their elders playing cards, until they fall asleep.

In the morning you go up to one of the women who is washing a boy and ask, as you see the great number of children around her, whether they are all hers: she courtesies and says, "Me no spik Inglish;" but by pantomime you make her understand, and she laughingly says, "Yah, yah;" and you think of Russell's song,—

Their train is a slow one; it is side-tracked for the great fliers as they reach a single-track road.

The very cattle-trains have precedence of them. We watch their train as it reaches the great brown prairie; a little black shack or two is all you can see. The very tumble-weeds outstrip their slow-moving train; but after many weary hours they reach the end of the road, so far as it is built that day; it will go three miles farther to-morrow. As yet there are no freight-sheds, and they camp out on the prairie. The cold stars come out, the coyotes' sharp bark is heard in the distance, blended with the howl of the prairie wolf. Some of them dig holes in the side-hill, and put their little ones in them for the night. Tears come into the eyes of the mothers as they think of home and relatives beyond the seas.

[52]And there we will leave them for twelve years, and then on one of our transcontinental palaces on wheels we will follow the immigrant trail. Where they passed black ash-swamps and marshes and scattered homes, we go through villages with public libraries; where they touched the brown prairie, we view a sea of living green; where they took five days, we go in two; where they stepped off at the end of the road, we stop at a junction whose steel rails run on to the Pacific or the Gulf of Mexico; where they made the shelter for their little ones in the ground, we find a good hotel, a city alive to the finger-tips, electric cars on the streets, an opera-house, and a high school just about to keep its commencement. On the street we notice some people that appear somewhat familiar, but we are not sure. When we spoke to them twelve years ago they said with a courtesy, "Me no spik Inglish;" but now without a courtesy they talk in broken English. The man has lost his big beard, his clothes are well-made; the[53] wife is no longer like a bag of meal with a string around it. No; with a daily hint from Paris, she has all the feathers the law allows.

They are making for the high schoolhouse, and we follow them. A chorus of fifty voices, with a grand piano accompaniment, is in progress as we take our seats, after which a boy stands forth and declaims his piece. We should never know him. It is one of our tow-headed youngsters from the wharf. The old father sits with tears of joy running down his wrinkled face. He can hardly believe his senses. He remembers when his grandsire was a serf under Nicholas, and it seems too good to be true. But he hears the neighing of his percherons under the little church-shed; and by association of ideas his fields and waving grain, his flocks, herds, and quarter section, rise before his mind's view, and he opens his eyes to see his favorite daughter step on the platform dressed in white, and great June roses drooping on her breast; and the old man's[54] eyes sparkle as his daughter steps down amid a round of applause as she says in the very spirit of old Cromwell, "Curfew shall not ring to-night."

And this is real. It has been going on for a quarter of a century. States with whole counties filled with Russians voting, and being the banner counties to have prohibition in the State's Constitution; or, like North Dakota, with nearly seventy per cent foreign voters, driving the lottery from them when needing money sorely. Men and women who could scarcely speak the English language living to see their sons senators and governors.

All the dismal prophecies about ruin from the immigrant are disproved as one looks over Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas to-day; and instead of having a great German nation on this side of the Atlantic, as one writer predicted, we have in the great agricultural States some of our stanchest American citizens.

One of the mightiest factors in human[55] life to-day is the language we use. Three centuries ago there were about 6,000,000 using it; to-day 125,000,000 speak the English tongue. The Duke of Argyle was once asked which was the best language. He said, "If I want to be polite I use the French, if I want to be understood I take the English, if I want to praise my Maker I take the Gaelic, my mother-tongue." Foreigners coming here think in their own language, even though they may be able to speak in ours; gradually they come to think in English, but still they dream in their mother-tongue; at last they dream, think, and speak in the language of the land, and become homogeneous with the nation.

God's greatest gift to this New World is the foreigner. The thought came to me while on my way to Savannah: Why did not the discoverers of the Western Hemisphere find a higher civilization than the one they left? Why should God have kept so large a portion of the[56] world hidden from the eyes of Europe for thousands of years? Had he not some grand design that in the fulness of time he would lead Columbus, like Abraham of old, to found a new nation?

Take your map and find those States which the stream of immigration has passed by, and in every case you find them behind the times. Strange how prejudice warps our vision! Jefferson said, "Would to God the Atlantic were a sea of flame;" and Washington said, "I would we were well rid of them, except Lafayette." Strange words for a man who would not have been an American had his ancestors not been immigrants. Hamilton, the great statesman, was an immigrant. Albert Gallatin the financier, Agassiz the scientist, and thousands of illustrious names, make a strong list. One-twelfth of the land foreigners!—but one-fourth of the Union armies were foreigners too.

[57]WHAT THEY BECOME.

When Linnæus was under gardener, the head gardener had a flower he could not raise. He gave it to Linnæus, who took it to the back of a pine, placed broken ice around it, and gave it a northern exposure. In a few days the king with delight asked for the name of the beautiful gem. It was the Forsaken Flower.

So there are millions of our fellow-men in Europe to-day, in a harsh environment, sickly, poor, and ready to die; but when they are transplanted, they find a new home, clothes, food, and, above all, the freedom that makes our land the very paradise for the poor of all lands. These immigrants have made the brown prairie to blossom as the rose, the wilderness to become like the garden of the Lord. They drove the Louisiana Lottery out of North Dakota; they voted for temperance in South Dakota. Their hearts beat warm for their native land, but they are true to their adopted country.

[58]The mixture of the nationalities is the very thing that makes us foremost: it has produced a new type; and if we but do our duty we shall be the arbitrator of the nations. There is no way to lift Europe so fast as to evangelize her sons who come to us. Sixteen per cent go home to live, and these can never forget what they saw here; did we but teach them aright, they would be an army of foreign missionaries, fifty thousand strong, preachers of the gospel to the people in the tongue in which they were born, and thus creating a perpetual Pentecost.

One other great fact needs pointing out. The discovery of this land was by the Latin races; and yet they failed to hold it, lacking the genius for colonization for which the Anglo-Saxon is pre-eminent. During the last fifty years, over 13,000,000 immigrants have come to this land. Great Britain sent nearly 6,000,000; Germany, 4,500,000; Norway and Sweden, 939,603; Denmark, 144,858; the Netherlands, 99,522; Belgium, 42,102. Here we[59] have over 11,000,000 Anglo-Saxon, Teutonic, and Scandinavian, of the 13,000,000, and almost half of them speaking English, while Italy, Russia, Poland, France, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Spain, Portugal, and all other nations sent but 1,708,897 out of the 13,296,157. And we must note also that nearly all of the Latin races came within the last few years; so that we were a nation 50,000,000 strong before many of them came, and eighty per cent of all our people speak English.

No nation ever drove out its people without loss, as witness Spain and France with their Protestants and Huguenots. England took them, and they helped to make her great. Often when a nation has actually been conquered in war, she in turn conquers her victors and is made better. Germany conquered Rome; but Roman laws and Roman government conquered the invaders, and made Germany the mother of modern civilization. Norsemen, Danes, and Saxons invaded Britain, and drenched her fields in blood. The Normans brought[60] their beef, their mutton, and their pork, but the English kept their oxen, sheep, and swine; and eventually from the Norman, Dane, and others came the Anglo-Saxon race. England has four times as much inventive genius as the rest of Europe, but America has ten times as much as England; and why? Because added to the English colony is all Europe; and in our own people we have the practical Englishman, the thoughtful German, the metaphysical Scot, the quick-witted Irishman, the sprightly Gaul, the musical and artistic Italian, the hardy Swiss, the frugal and clear-headed Swede and Norwegian; and all united make the type which the world will yet come to, the manhood which will recognize the inherent nobility of the race, its brotherhood, and the great God, Father.

A TYPICAL SOD HOUSE.

A TYPICAL SOD HOUSE.As the waves of the sea cast up all sorts of things, so the waves of humanity that flood the frontiers cast up all sorts and conditions of men. To go into a sod house and find a theological library belonging to the early part of the century, or to hear coming up through the ground a composition by Beethoven played on a piano, is a startling experience; so are some of the questions and assertions that one hears in a frontier Sunday-school.

I remember one old man who was in class when we were studying that part of the Acts of the Apostles where the disciples said, "It is not reason that we should leave the word of God and serve tables;" the old fellow said, "I have an idee that them tables was the two tables of stone that Moses brought down from[62] the Mount." This was a stunner. I thought afterwards that the old man had an idea that they were to leave the law and stick to the gospel; but still it did not seem right to pick out men to serve the tables if that was what he meant.

Another would be satisfied with nothing but the literal meaning of everything he read. So when I explained to the class the modern idea of the Red Sea being driven by the wind so as to leave a road for light-laden people to walk over, the old man was up in arms at once, "Why," said he, "it says a wall;" and no doubt the pictures which he had seen in his youth, of the children of Israel walking with bottle-green waters straight as two walls on either side, and the reading of a celebrated preacher's sermon, where it spoke of the fish coming up to peep at the little children, as if they would like a nibble, confirmed the old man in his views.

In vain I told him that a wind that would hold up such a vast mass of water would blow the Israelites out of their[63] clothes; still he stuck to his position until I asked him whether, when Nabal's men told him that David's men had been a wall unto them day and night, he thought that David had plastered them together?

He said, "No; it meant a defence," and apparently gave in, but muttered, "It says a wall, anyway."

Another man told me that if a man cut himself in the woods, there was a verse in the Bible so that if he turned to it and put his finger upon it, the blood would at once stop running; and he wanted to know whether I knew where to find it. I told him I was very sorry that I did not know.

On the other hand, you may find a man with a Greek Testament, and well up in Greek, making his comments from the original. Here a Barclay & Perkins brewer from London, who has plunged into the woods to get rid of drink, and succeeded. Here a family, one of whom was Dr. Norman McLeod's nurse, and a playmate of the family. Another informs[64] you he preached twenty-five years, "till his voice give out;" and here a Hard-shell Baptist, who "don't believe in Sunday-schools nohow."

The minute-man at the front needs to be ready for all emergencies, for he meets all kinds of original characters. One of the most successful men I ever heard of was the famous Father Paxton described by the Rev. E. P. Powell in the Christian Register in a very bright article from which I quote:—

When "blue," I always went down to the Depository, and begged him for a few stories. He rode a splendid horse, that was in full sympathy with his master, and bore the significant name, Robert Raikes. There were few houses except those built of logs, and these were not prejudiced against good ventilation. He laughed long and loud at his experience in one of these, which he reached one night in a furious storm. He was welcomed to the best, which was a single rude bed, while the family slept on the floor, behind a sheet hung up for that special occasion. Paxton was so thoroughly tired that he slept sound as soon as he touched the bed; but he half waked in the morning with the barking of a dog. The master of[65] the house was shaking him, and halloing, "I say, stranger! pull in your feet or Bowser 'll bite 'em!" Stretching out in the night, he had run his feet through the side of the house, between the logs; and the dog outside had gone for them. The time he took in pulling in was so trifling as to be hardly worth the mention.

Those who know little of frontier life can have no idea of the difficulties to be met by a man with Paxton's mission. There was one district, not far from Cairo, that was ruled by a pious old fellow who swore that no Sunday-school should be set up "in that kidntry." Some one cautioned "the missioner" to keep away from M——, who would surely be as good as his word and thrash him. M—— was a Hard-shell Baptist, and owned the church, which was built also of logs. He lived in the only whitewashed log house of the region. Instead of avoiding him, Father Paxton rode up one day, and jumping off Robert Raikes, hitched him to the rail that always was to be found before a Southern house. Old M—— sat straddle of a log in front of his door eating peaches from a basket. Paxton straddled the log on the other side of the basket, and helped himself. This was Southern style. You were welcome to help yourself so long as there was anything to eat. The conversation that started up was rather wary, for M—— suspected who his visitor was. Pretty soon Paxton noticed some hogs in a lot near them. "Mighty fine lot of hogs, stranger!"

[66]"And you mought say well they be a mighty fine lot of hogs."

"How many mought there be, stranger?"

"There mought be sixty-two hogs in that there lot, and they can't be beat."

Just then a little boy went up and grabbed a peach.

"Mought that be your young un, stranger?" asked Paxton.

"As nigh as one can say, that mought be mine."

"And a fine chap he be, surely."

"A purty fine one, I reckon myself."

"How many young ones mought you have, my friend?"

"Well, stranger, that's where you have me. Sally, I say, come to the door there! You count them childer while I name 'em—no, you name 'em, and I'll count."

So they counted out seventeen children. Paxton had his cue now, and was ready.

"Stranger, I say," he said, "this seems to me a curious kind of a kidntry."

"Why so, stranger?"

"Because, when I axed ye how many hogs ye had, ye could tell me plum off; but when I axed ye how many children ye had, ye had to count right smart before ye could tell. Seems to me ye pay a lettle more attention to your hogs than ye do to your childer."

"Stranger," shouted M——, "ye mought sure be the missioner. You've got me, sure! You shall[67] have the church in the holler next Sunday, and me and my wife and my seventeen shall all be there."

True to his word, he helped Paxton to establish a school. When I was in St. Louis, there was a Sunday-school convention there. A fine-looking young man came up to Father Paxton, who was then in charge of the Sunday-school Depository, and said,—

"Don't ye know me, Father Paxton?"

"No," said Paxton; "I reckon I don't recall ye."

"Well, I am from ——; and I am one of the seventeen children of M——. And I am a delegate here, representing over one hundred Sunday-schools sprung from that one."

Perhaps no man gets such a vivid idea of the dark and bright sides of frontier life as the general missionary. One week among the rich, entertained sumptuously, and housed with all the luxuries of hot air and water and the best of cooking; and then, in less than twelve hours, he may find himself in a lumber-wagon, called a stagecoach, bumping along over the wretched roads of a new country, and lodged at night in a log house with the wind whistling through the chinks where the mud has fallen out, to sit down with a family who do not taste fresh meat for weeks together, who are twelve miles from a doctor and as many from the post-office.

Nowhere in the world can a man so soon exchange the refinements of civilized life for one of hardship and toil[69] as in a new country. Our minute-man must share with the settler all his toils, and yet often forego the settler's hope. The life among frontiersmen is apt to unfit a man for other work. His scanty salary will not allow many new books, and often his papers are out of date. The finding of a home is one of the worst of hardships. Let us start with the missionary to the front; our way lies through a rich valley. The moon is at her full, and we pass fine farms. The scent of the hay floats in at the car windows; fine orchards surround the houses, while great flocks of sheep are seen feeding, and herds resting, comfortably chewing the cud.

But morning comes, and we must change cars. We are in a city of 80,000 people, with 498 factories with 15,000 employees, where a few years ago a few log houses only were in sight. As we change cars we change company too. We left the train at a Union Station, with its green lawns and trim garden, to[70] find a station with old oil-barrels around it, the mud all over everything, the train filled with lumbermen, with their red mackinaw shirts and great boots spiked on the bottoms, and a comforter tied around the waist.

A few women are on the train, often none at all. Our new road is poorly ballasted, and the train bounces along like a great bumble-bee. The men are all provided with pocket-pistols that are often more deadly than a revolver. At the first station—a little mouse-colored affair, sometimes without a ticket-agent—we notice the change. The stumps are thick in the fields; many of the houses have the building-paper fluttering in the wind; the streets are of sawdust. You can see the flags growing up from the swamp beneath. The saloons are numerous; and as the train is a mixed one in more senses than one, abundant time is given while shunting the freight-cars for the men to reload their pocket-pistols and get gloriously drunk.

And so on we go again for forty miles, when all leave the train but one solitary man, who lies prostrate in the car, too big for our little conductor to lift, and so he goes to the terminus with us. It is getting late, and the last ten miles are through a wilderness of dead pines, with here and there a winding line of timothy and clover that has sprung up from seeds dropped by the supply teams. But presently we see a pretty stream with bosky glades, and visions of speckled trout come up; then an immense mill, and a village of white houses with green Venetian blinds, and a pert little church. We had expected some good deacon to meet us and take us home to dinner; but, alas! no deacon is waiting, or dinner either for some time. For out of eight hundred people only five church-members can be found, four of them women.

It well nigh daunts the minute-man's courage as he sees the open saloons, the[72] big, rough men, the great bull-terriers on the steps of the houses. The awful swearing and vile language appal him, and the thought of bringing his little ones to such a place almost breaks his spirits; but here he has come to stay and work. The hotel is his home until he can find a house for his family. There is but one place to rent in the town, and that is in a fearful condition. It is afterwards whitewashed and used as a chicken-coop. But at length a family moves away, and the house is secured just in time; for the new schoolmaster is after it, and meets the man on the way with a long face.

"You got the house?"

"Yes."

"What can I do? my goods are on the way!"

"Oh, they will build one for you, but not for a preacher."

"No, they won't. Could I get my things in for eight or ten days?"

"Oh, yes." The minister is so glad to get the place that he feels generous. But[73] the good man stays eleven months; and he has besides his wife and child, a mother-in-law, a grandmother-in-law, a niece, a protégée, and a young man, a nephew, who has come to get an education and do the chores. They are all very nice people, but it leaves the minute-man and his wife and four children with but three rooms. The beds must stand so that the children have to climb over the head-boards to get at them. The family sit by the big stove at their meals, and can look out on the glowing sand and see the swifts darting about; while in the winter the study is sitting-room and playground too.

But this is luxury. Often the minute-man must be content with one room, for which the rent charged may be extortionate. Even then he must keep his water in a barrel out in the hall. In cold weather perhaps it must be chopped before getting it into the kettle.

I knew of one man who lived in a log house. It had been lathed and plastered on the inside, and weather-boarded on the[74] outside, so that it was very warm, and so thick that you could not hear the storms outside, which raged at times for days together.

One day late in March a fearful snowstorm arose, and for three days and nights the snow came thick and fast. Luckily it thawed fast too. On the fourth day there was need for the minute-man to go for the doctor, who lived some miles away. On the road he engaged a woman to go to his house, where her services were in demand. After he had summoned the doctor the good man took his time, and reached home in the afternoon. He was greeted by a duet from two young strangers from a far land.

Night closed in fast; the house was so thick that no one suspected another storm; but on going out to milk the cow, it was storming again, and the man saw he had need to be careful or he would not find his way back from the barn, though it was only a few yards away.

When he reached the house, the good[75] lady visitor, who had insisted that she could not stay later than evening, gave up all hope of getting home that night. She stayed a fortnight! For this time the storm raged without thawing, and for three nights and days the snow piled up over the windows, and almost covered the little pines, in drifts fifteen feet deep. Not a horse came by for two weeks.

Once another man started in a storm on a similar errand; but in spite of his love, courage, and despair, he was overwhelmed, and sinking in agony in the drift, he never moved again. When the storm was over, the sun came out; and what a mockery it seemed! The squirrels ran nimbly up the trees, the blue jays called merrily; but the settlers looked over the white expanse, and missed the gray smoke that usually rose from the little log shanty.

The men gathered to break the roads; the ox-team and snow-plough were brought out, and the dogs were wild with delight as they ploughed up the snow with their snouts, and barked for very joy; but the[76] men were sorrowful, and worked as for life and death. Half way to the house the husband was found motionless as a statue, his blue eyes gazing up into the sky. The men redoubled their efforts, and gained the house. The stoutest heart quailed. A poor cat was mewing piteously in the window. And when at last the oldest man went in, he found mother and new-born child frozen to death.

The South has two kinds of frontier,—that which has never been settled, and once thickly settled parts that have grown up to wild woods and wastes since the war. In old times the slave had a half-holiday on Saturday, which custom the colored brother still keeps up; and a more picturesque scene is not to be found than that presented by a town, say of three thousand inhabitants, where the county has seven colored people to one white.

Never was such a motley company gathered in one place,—old men with grizzled heads, all with a rabbit-foot in their pocket, a necklace for a charm around their necks, their bronzed breasts open to view; old mammies with scarlet bandannas; young belles of all shades—here a mulatto girl in pale-blue dress and[78] pointed shoes, her waist as disfigured as any Parisian's, there a mammoth, coal-black negro driving a pair of splendid mules.

Here is an original turnout; it was once a sulky. The shafts stick out above the great ears of the mule; the seat has been replaced by an old rocking-chair; the wheels are wired-up pieces of a small barrel that have replaced some of the spokes, while fully half the harness is made up of rope, string, and wire. The owner's clothes are one mass of patchwork, and his hat is full of holes, out of which the unruly wool escapes and keeps his hat from blowing off.

The sidewalk presents a moving panorama unmatched for richness of color. As we leave the town, we ride past plantations that once had palatial residences, whose owners had from one to three thousand slaves, the little log cabins arranged around and near the house. In many cases the houses are still there, but dilapidated.

[79]Here, where each white person was once worth on an average thirty thousand dollars, to-day you may buy land for a dollar an acre, with all the buildings. It is a lovely park-like country, with clear streams running through meadows, branching into a dozen channels, where the fish dart about; and the trees shade and perfume the air with their rich blossoms, and the whole region is made exquisitely vocal with the song of the peerless mocking-bird. Here, too, the marble crops out from the soil, and some of the richest iron ore in the world, all waiting for the spirit of enterprise to turn the land into an Eldorado.

To be sure, there are obstacles; but the Southern man of to-day was born into conditions for which he is not responsible, any more than his father and ancestors before him were responsible for theirs. And those that started the trouble lived in a day when men knew no better. Did not old John Hawkins as he sailed the seas in his good ship Jesus, packed with[80] Guinea negroes, praise God for his great success? So we find the men of that day piously presenting their pastor and the church with a good slave, and considering it a meritorious action.

Time, with colonies settling in the new South, will yet bring back prosperity without the old taint, and keep step with all that is good in the nation. It cannot be done at once. I knew an energetic American who had built a town, and thought he would go South, and at least start another; but, said he, "I had not been there a week when I felt, as I rocked to and fro, listening to the music of the birds, and catching the fragrance of the jessamine, that I did not care whether school kept or not."

There is no great virtue in the activity that walks fast to keep from freezing. We owe a large portion of our goodness to Jack Frost.

Dr. Ryder tells a story of one of our commercial travellers who had been overtaken by night, and had slept in the home[81] of a poor white. In the morning he naturally asked whether he could wash. "Ye can, I reckon, down to the branch." A little boy belonging to the house followed him; for such clothes and jewellery the lad had never before seen. After seeing the man wash, shave, and clean his teeth, he could hold in no longer, and said,—

"Mister, do you wash every day?"

"Yep."

"And scrape yer face with that knife?"

"Yep."

"And rub yer teeth too?"

"Yep."

"Wal, yer must be an awful lot of trouble to yerself."

Civilization undoubtedly means an awful lot of trouble.

The frontier is the place to find all sorts of conditions and also of men. Monotony is not one of the troubles of the minute-man. He is frequently too poor to dress in a ministerial style, and quite often he is not known until he begins the services. This sometimes leads to the serio-comic, as witness the following:—