*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 40757 ***

THE

NURSERY

A Monthly Magazine

For Youngest Readers.

VOLUME XXIX.—No. 6.

BOSTON:

THE NURSERY PUBLISHING COMPANY,

No. 36 Bromfield Street.

1881.

Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1881, by

THE NURSERY PUBLISHING COMPANY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

IN PROSE.

| | PAGE |

| The Careless Nurse | 161 |

| Master Baby | 165 |

| Two Small Boys | 166 |

| A Saucy Visitor | 168 |

| How Georgie Fed his Fawn | 171 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 177 |

| A Picnic in a Strange Garden | 178 |

| Two Small Girls | 182 |

| The Careful Nurse | 183 |

| Ralph's Great-Grandmother and her History | 185 |

IN VERSE.

| | PAGE |

| Feeding the Fowls | 163 |

| A Polite Dandelion | 164 |

| Kitty didn't mean to | 167 |

| The Rose | 173 |

| Margie's Trial | 180 |

| Why the Chick came out | 184 |

| June | 188 |

[161]

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 6.

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 6.

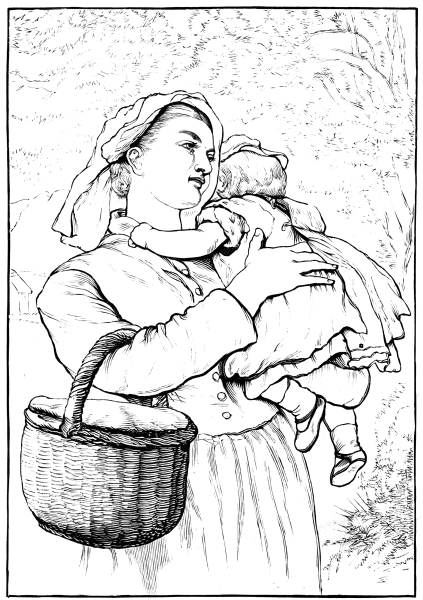

THE CARELESS NURSE.

HE rights of man do not give me much concern;

neither do I trouble myself much about the rights

of woman. My mission is to look after the rights of

children. I never forget this wherever I may be.

[162]

Some people may think that the rights of children are

safe enough in the care of the fathers and mothers.

Are they indeed! How many children are sent out, day

after day, in charge of nurses? Who protects the children

against careless and cruel nurses? Anxious mother, answer

me that.

Many cases of gross neglect have come under my eye. I

will mention one case that took place last summer at the

seaside.

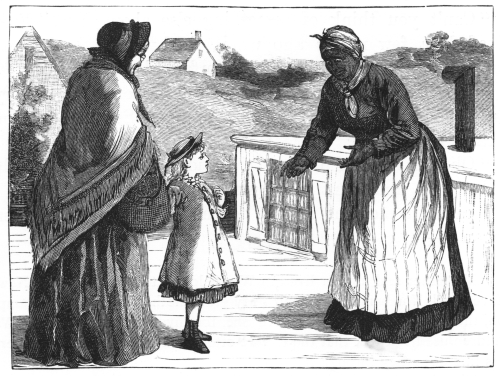

I was out in my yacht at the time. Scanning the shore

with my spy-glass, this is what I saw:—

A good-looking young woman was pushing a baby-carriage

before her. In the carriage was a little child. The young

woman seemed to be singing, and all went well until a

young man came up and walked by her side.

From his dress I should say that he was a sailor. Perhaps

he had just landed from a man-of-war. His trousers had

the man-of-war cut.

The young man and the young woman talked and laughed

together as they went along. They seemed to be very good

friends. But what became of the infant in the carriage?

Poor child! She fell off the seat. Her head hung over

the side of the carriage, just in front of the wheel, and there

she lay shrieking for help.

I could not hear her shrieks, for I was a mile away; but

the sight was enough for me. I seized my trumpet. "Shipmate,

ahoy!" I shouted to the sailor-chap.

No answer. It was plain that the sailor-chap did not

care in the slightest degree for that poor suffering child.

Nobody offered to help her.

"Steer for the shore!" I said to my helmsman. "Bear

down to the rescue!" We landed as soon as we could, but

not without some delay, and when we reached the place[163]

it was too late. Nurse, carriage, sailor-chap, and all were

gone.

What was the fate of that poor infant is a mystery to me

to this day. But I tell the story as a warning to all mothers

against trusting their children to a careless nurse.

JACK TAR.

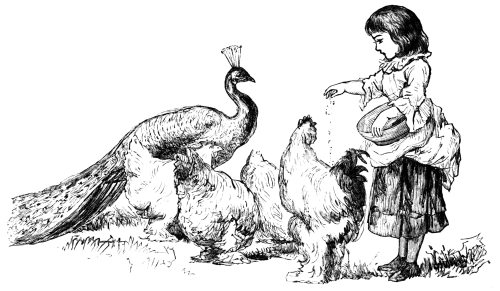

FEEDING THE FOWLS.

Pecking away, and looking so knowing,

Feathers and tails in the breezes blowing,

"Cluck, cluck, cluck!" come the hens to be fed,

And Edith is scattering crumbs of bread.

The peacock comes also, strutting so grandly,

His long tail behind him trailing so blandly,

Doesn't he look as proud as a king,

With his crown, and his tail, and his brilliant wing!

S. T. U.

[164]

A POLITE DANDELION.

By George Cooper.

"Oh, what shall I do, Dandelion?

My white satin gown will be spoiled:

The rain has begun;

I've nowhere to run;

And my bonnet and all will be soiled."

"Don't be in a flutter, Miss Miller,

And where are you going so fast?

My sunshade of gold

Above you I'll hold

Till this very hard shower has passed."

[165]

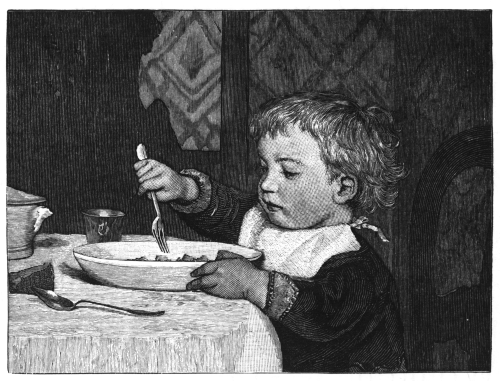

MASTER BABY.

ASTER BABY has been playing in the park all

the morning. He has been chasing a butterfly.

He did not catch the butterfly. But he has come

home with two rosy cheeks and a good appetite.

Now he must have his dinner. Tie his bib

around his neck. Seat him at the table. Give him some

soup. Now cut him up some meat and potato, and let him

feed himself.

He is a little awkward; but a hungry boy will soon learn

how to handle a fork. Let him alone for that. It will not

take long to teach him how to use a knife too.

Boys need a good deal of food to make them strong and

hearty. Give them plenty of fresh air. Let the sun shine

on them. Then they will be sure to eat with a relish.

J. K. L.

[166]

TWO SMALL BOYS.

This is our Sam. He is the

boy who goes to sea in a bowl.

He throws out a

line, and catches a

fish. What does

the fish look like?

Where would Sam

be if the bowl should tip over?

Would he get wet?

This is Billy with his whip.

He thinks he would

like to drive a coach.

But where will he get

his team? He will find

it, I dare say, without

going out of the room.

An arm-chair will do for a

coach, and a pair of boots will

make a fine span of horses.

M. N. O.

[167]

KITTY DIDN'T MEAN TO.

Joanna scolds my kitty every day:

I'm filled with grief.

Just now to Mary Ann I heard her say,

"That cat's a thief!"

Poor kit! you did not wish for milk to-day,

But wanted meat.

You took a little bit from off the tray,

[168]And, with your feet,

A glass of water, standing in the way,

You tumbled down;

And just for this you had to bear, all day,

Joanna's frown.

I think that Miss Joanna must be seen to;

For, kitty, I am sure you didn't mean to.

AMANDA SHAW ELSEFFER.

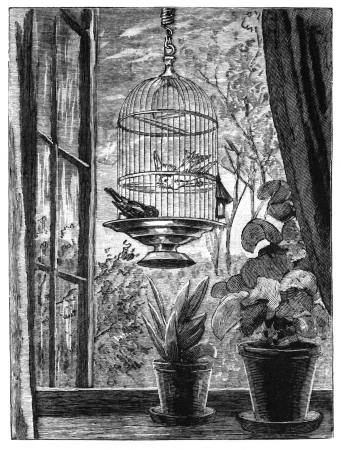

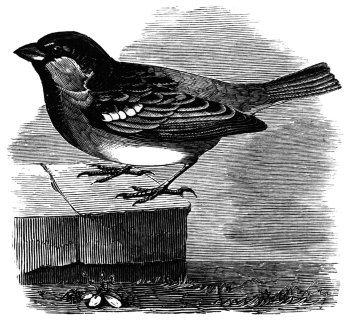

A SAUCY VISITOR.

NCE upon a time a mother-sparrow and her three

children lived in a great big maple-tree, which stood

before a great big house, which had a broad piazza

in front of it. The mother-bird often used to talk

to her children about the people who lived in the

house, and their pets.

"See, Polly Dolly Adeline," she said to her oldest child

one day, "see those lazy yellow canaries down there on the

piazza. They have every thing they want. See how they

are coddled while we are left to shift for ourselves."

"Boo-hoo!" said Polly Dolly. "I don't think it is a bit

fair."

"I don't either," said the youngest of all. He was a

pert little fellow. His name was Flop. He was so called,

because, when he first began to fly, he would flop over on

one side.

But he could fly well enough now, and so he said boldly,

"I mean to go down to one of those cages, and eat some of

that nice seed myself. I'll let young Canary know that I

am as good as he."

[169]

At these words Mrs. Sparrow was so frightened that she

fell off the branch; but she soon flew back, and said, "Flop,

you naughty boy, don't you go! you may get killed."

"Cats, you know, Flop!" said Polly Dolly Adeline. "Cats

with green eyes!"

"Pooh!" said Flop. "Who cares? I'm not afraid."

Flop flew gaily down to the piazza railing. Here he

stopped, and looked around; while his mother and sisters

watched him in fear and trembling. Nobody was on the

piazza: so Flop flew straight to one of the cages.

"How do you do, my young friend?" he said, saucily[170]

helping himself to the seed that had been scattered. "I've

come to take dinner with you."

Mr. Canary did not like this at all. "You've not been

invited," he squeaked out, ruffling up his feathers, and flying

at Flop with all his might. But the bars were between

them; and Flop went on eating his dinner as calmly as

possible.

Then the canary became so angry that he danced back

and forth on his perch, and screamed. Flop made another

very polite bow. "Oh, how good that hemp-seed tastes!"

said he. "The rape-seed, too, is very nice,—nice as the

fattest canker-worm I ever ate."

So he went on eating, looking up now and then to wink

at his angry host. When he had eaten all he could find, he

made his best bow and said saucily, "Thank you, sir, thank

you. Don't urge me to stay longer now. I'll come again

some other day," and he flew back to his anxious mother

and sisters.

B. W.

[171]

HOW GEORGIE FED HIS FAWN.

EORGIE stood at the kitchen-door with a piece of

bread in his hand to feed his pet fawn. There

was the fawn chained to a post in the grass-plat.

Between them was a long gravel walk. How was

Georgie to get the bread to the fawn?

Easily enough, one would think,—by carrying it straight

to the fawn. But Georgie didn't find this such an easy

thing to do. He met with difficulties.

In the first place there was Rover, the big brown pup.

Georgie had not taken three steps, when Rover spied the

bread, and, thinking it was for him, began jumping after

it. Georgie thought he would have to run back to the

house; but, seeing a stick on the ground, he picked it up,

and shook it at Rover. Rover was afraid of the stick, and

ran meekly away.

Nothing else happened to trouble Georgie until he had

gone halfway up the walk. Then he met another difficulty.

Two big turkey-gobblers, looking very red about the head,

and with feathers all ruffled up, rushed towards him for the

bread, crying, "Gobble, gobble!" in a frightful manner.

Georgie hesitated. Dare he go past them? "Gobble,

gobble!" screeched the turkeys. Down went the bread on

the ground, and back to the house, as fast as his legs could

carry him, ran Georgie.

His mother saw two big tears in the little fellow's eyes

and felt sorry for him. She cut another piece of bread,

turned his apron up over it so the turkeys could not see it,

and told him to run bravely past them. He hoped they

were still eating the other piece, and would not notice him;[172]

but they had swallowed every crumb and ran toward him

for more.

He screwed up his courage, and tried to run by them.

Alas! he stumbled and fell. Away rolled the bread, and,

before he could get it again, the gobblers had it and were

quarrelling noisily, each trying to pull it away from the

other one.

This second loss was more than little

Georgie could bear. He went crying

into the house. Then his sister Jennie

said she would go with him, and

keep off the turkeys. She took

some bread in one hand, and

held Georgie's hand with

the other, and this time

the turkeys were

passed

safely.

Georgie fed the pretty fawn, who took the bread from his

hand, and capered about with delight, for he likes to have

Georgie pet him, and pines for his company. Georgie is

going to ask the gardener to buy two chains and fasten

the two old gobblers in some other part of the yard. Then

he can visit the fawn often.

AUNT SADIE.

[173]

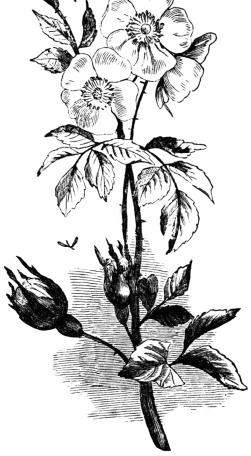

THE ROSE.

ANNIE.

The sweetest and the brightest days

Of all the happy year!

The green leaves dance, the gay birds sing,

The merry June is here!

We will of roses weave her crown,

The fairest that unclose;

Each one of different form and hue,

Yet each a perfect rose.

BESSIE.

(With a red rose.)

And this one will outshine them all;

Amid the garden's rare

And splendid flowers, it raised its head,

[174]The brightest blossom there.

All decked with dew like gems, its robe

Of royal crimson glows—

The matchless queen of summer-time,

The beautiful red rose!

CHARLOTTE.

(With a white rose.)

But this to me is lovelier far,

So pure and sweet it seems;

Among the green leaves on the bough

Like fallen snow it gleams.

Its breath gives perfume to the wind,

As over it it blows;

'Tis stainless as an angel's wings,

The fragrant, fair white rose.

[175]

DELIA.

(With a yellow rose.)

And this, to greet the early morn,

In yellow mantle shone,

Bright as is China's emperor

Upon his dazzling throne.

It opens wide its golden leaves,

Its gleaming heart it shows,—

A sunshine-loving, cheery thing,

The winsome yellow rose!

EVA.

(With a brier rose.)

Among the brambles and the brake

Beside the dusty way;

This dainty little blossom sheds

Its sweetness all the day.

It makes the rough hill pastures fair;

Amid the rocks it grows;

It clambers o'er the gray stone wall,—

The simple brier rose!

[176]

FRANCES.

(With a blush rose.)

This blushes like a morning cloud.

GERTRUDE.

(With a moss rose.)

And this is veiled in moss.

HELENA.

(With a cluster of climbing roses.)

This, with the honeysuckle-vines,

My lattice twines across.

ANNIE.

(To whom all the roses are given.)

And which one is the fairest flower

I'm sure cannot be told:

We'll twine them all in one long wreath,

The white and red and gold.

MARIAN DOUGLAS.

[177]

DRAWING-LESSON.

DRAWING-LESSON.

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 6.

[178]

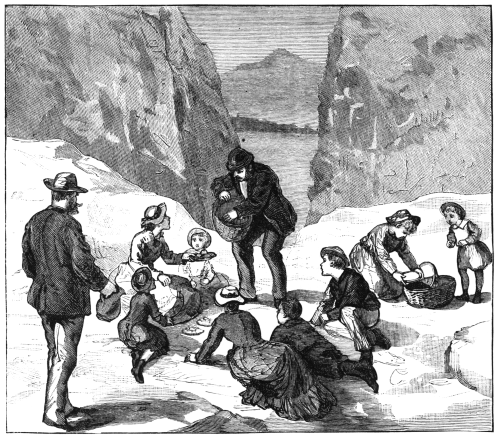

A PICNIC IN A STRANGE GARDEN.

F I should ask you children to tell me what a garden

is, I think you would all say, "A place where trees,

flowers, and grass grow." That would be a good

answer.

But the garden where this picnic took place is of a very

different kind. Instead of bright leaves and flowers, there

are hundreds of rocks of many sizes and shapes. Its name

is the "Garden of the Gods," and it lies at the foot of the

Rocky Mountains, in Colorado.

The color of most of the rocks is red; but some are silvery

gray, and some nearly white. Seen together they make a

fine contrast. Many have strange shapes, and look like nuns

and priests, animals, birds, and fishes turned into stone.

On one high rock may be seen the image of a man and a

bear; on another, the outline of a lion's head, and part of its

body, so perfect in shape, that it seems as though some one

must have drawn it.

Some of the rocks are very high. One reaches up three

hundred and thirty feet. Near the top of it is a hole, which

looks from the ground to be about the size of a dinner-plate,

but is really large enough for a horse and buggy to pass

through.

A few trees manage to live high up on the rocks, and the

prickly cactus grows in the soil around them.

To this garden went, one bright summer day, a wagon-load

of people—six happy little girls and boys, with their

mothers and fathers—on a picnic.

The children were dressed in big shade hats, and clothes

that they might tear and tumble all they wished. Such fun

as they had! The older ones climbed the smaller rocks, and

made speeches to the little ones on the ground below. Then[179]

they all played "hide-and-seek," and never were there such

grand hiding-places.

At noon they had lunch. Their table was a large flat

rock. Mountain air and play give good appetites. How

they did enjoy eating the nice things, chatting and laughing

all the while!

After lunch away they ran in search of "specimens," by

which they meant pretty stones. They chipped pieces off

the rocks with hammers, playing they were miners finding

gold and silver. They filled their baskets, and pretended to

have made great fortunes.

They kept up the sport until five o'clock, when their

mammas said it was time to start for home, and counted[180]

the children to see if all were there. Only five could be

found. There should have been six. Who was missing?

It was four-year-old Willie. "Willie, Willie!" shouted

every one, and from the great red rock came a faint reply.

Then began "hide-and-seek" in earnest, and soon they spied

the little fellow sitting on the side of the rock full five

yards up.

"Why, Willie!" called his mamma. "What are you

doing up there?"

"Going to climb through the little hole, mamma; but I'm

tired."

His uncle climbed after him, and soon brought him down.

Six tired little children went early to bed that night, and

dreamed of stony men and women, lions and bears.

AUNT SADIE.

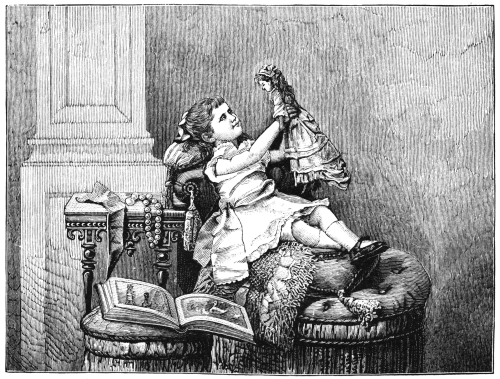

MARGIE'S TRIAL.

My beautiful Evelina,

Come listen to me, my dear;

I want to tell you a secret

That nobody else must hear:

We're going away to the country,—

Mamma and baby and I,

And grandmamma doesn't like dollies,

Now please, my darling, don't cry.

Oh, don't you remember last winter

She called you an image, my pet!

Just think, like those ugly old idols:

[181]I'm sure I shall never forget.

She's the loveliest grandma, my precious;

But some things are not to be borne:

I'm sure that my heart would be broken

If she should treat you with scorn.

I'll put on your very best bonnet,

Your pretty pink shoes on your feet;

And you shall sit up by the window,

And look at the folks in the street.

Oh, dear! but I never can leave you

A whole summer long on the shelf;

If you are an "image," my baby,

I'll just be a heathen myself.

EMILY HUNTINGTON MILLER.

[182]

TWO SMALL GIRLS.

Ann is not yet five years old.

But she knows how to read,

and is very fond of her

book. She does not

care to sit down, but

reads her book as she

walks. This is not a

good plan. It hurts the

eyes.

Grace, who is nine years old,

often has a book in her

hand. But she does not

read and walk at

the same time. She

sits down on the

floor. It would be quite as well

for her to take a chair and sit

up straight.

P. Q. R.

[183]

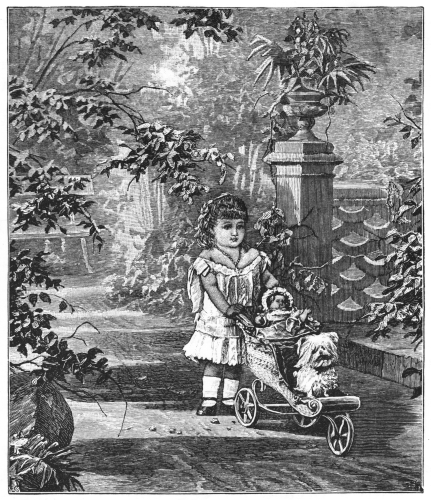

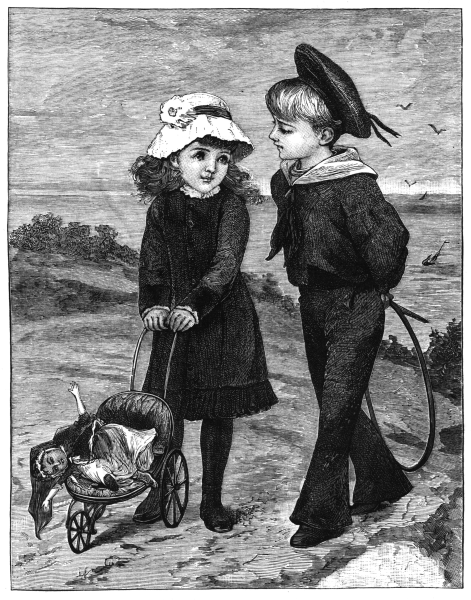

THE CAREFUL NURSE.

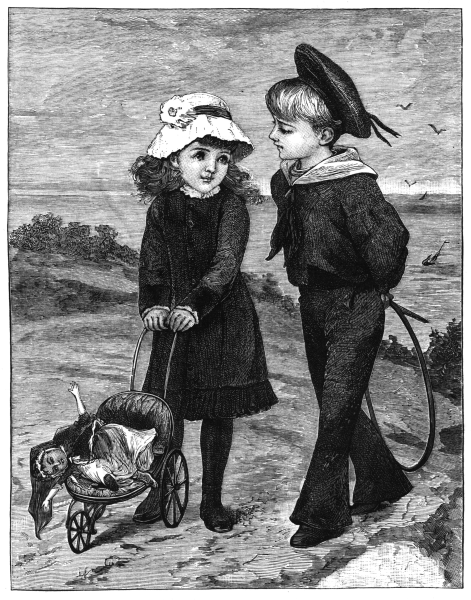

HIS is little Grace taking Dolly out for an airing. It

is a bright June day. The birds are singing. The

flowers are in bloom. It is so warm that Grace goes

without a hat.

Dolly is snugly seated in her carriage; and Snip

the dog, who barks, but never bites, has a place in it too.[184]

He is one of the breed known as the toy dog. He does not

bark unless you squeeze him. He is never cross.

Grace rolls them down the broad path through the garden.

She gives Dolly a nice ride, and then takes her home, and

puts her to sleep in her little bed. She never lets Dolly miss

her nap. Grace is a careful nurse.

JANE OLIVER.

WHY THE CHICK CAME OUT.

Benny Bright-Eyes, climbing over

Heaps of crisp and fragrant clover,

Spies the dearest, cutest thing,

Hiding under Biddy's wing.

What sees Benny next? A wonder!

Rudely pushed quite out from under

Biddy's breast, an egg comes sliding,

In its shell a chicken hiding.

"Ah!" says Benny as he gazes,

And his merry blue eyes raises,

"I know why his house he's spoiled:

He's afraid of being boiled."

M. J. TAYLOR.

[185]

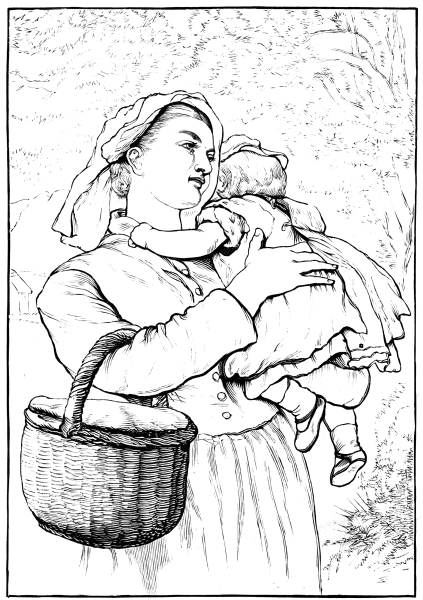

RALPH'S GREAT-GRANDMOTHER.

ISS EASTMAN, the pretty drawing-teacher at the

academy, boards in our family. Some time ago

she chanced to take up an old, faded daguerrotype-likeness

of my grandmother. She proposed copying it; and

a lovely picture in crayon, of Ralph's great-grandmother, is

the result.

My grandmother was ninety years old when the likeness

was taken; yet she appears in it erect and vigorous, sitting

in her high-backed chair, with her knitting-work in her

hand. She wears a snug cap, and a plain Quaker kerchief

folded smoothly over her black silk dress.

Naturally we have talked much about her; and my boys,

Ralph and Fred, who have a happy faculty for drawing me

out, have well-nigh exhausted all my memories of their

great-grandmother.[186]

"Can't you think of something else about her?" Fred

pleaded, a few nights ago when, tired of his books and

games, he had seated himself comfortably before the fire.

"Yes," I replied, "I have been thinking of another story

as I sit here knitting. It is about going to Southampton on

a canal-boat."

"Oh, that's splendid, I know!" said both boys in a breath.

"Hurry up, and count your stitches quick, mamma."

I paused a moment to knit to the seam-needle, and then

began:—

"My father and mother lived in Westfield, on the banks of the New-Haven

and Northampton Canal. My grandmother lived in Southampton,

the town next north of ours. She, too, lived near the canal. We

children used to think that the trip we often took from our house to hers

was like a journey through fairy-land.

"The first time I ever went out from under my mother's wing was

with my grandmother, who took me from home with her one bright June

day. I was a little sober on parting with my mother; but the negro

cook, on board the boat a fat, jolly-looking woman, took me under her

special care.

"I went down in her cabin, and she gave me cookies and great puffy

doughnuts, and a pink stick of candy, and I watched her while she

cleaned the lamps."

"Is that all?" said Ralph, as I paused a moment to

secure a dropped stitch in the red stocking.

"Oh, no indeed!" I say as I go on,—

"By and by my grandmother's family were all scattered. My grandfather

died, and left her sad and lonely; but she still lived in the old

homestead.

"I can see her room now. There were four windows in it,—two

looking east, towards Mounts Tom and Holyoke, and two south, over a

lovely old-fashioned garden filled with tulips, hollyhocks, southernwood,

thyme, cinnamon-roses, spice-pinks, lavender, white-lilies, and violets.

"There was an open Franklin stove in the room; and a little, chubby[187]

black teapot always stood on its top. One sunny south window was

filled with flowers. Grandmother always carried a bunch of flowers to

church with her, and she had a black velvet bag, in which she carried

sugar-plums, to give to us drowsy children on Sunday afternoon, when

the minister preached one of his long sermons."

"Just one story more," said Ralph, as I again paused to

observe what progress I was making in my knitting.

"Will you promise not to ask for another one to-night?"

"We promise certain sure," said Fred.

"Only tell a long one for the last."

"Very well," said I.

"Once my grandmother made a party for a

circle of cousins. We counted nine cousins in

all when we took our seats at the supper-table."

"What did you have for supper?"

observed Fred.

"We had nice seed-cookies cut into hearts,

diamonds, leaves, and rounds; frosted cup-cakes

powdered with pink sugar sand; little sweet

biscuits, currant-tarts, dried beef, plum preserves,

honey in a great glass dish, and jelly from a blue

mug. We poured milk from a great green pitcher

into pink china cups, and used grandma's tiny

silver tea-spoons for our preserves."

"Wasn't that splendid!" said Ralph. "I wish some one

would invite me to such a supper."

"In the evening we drew up before the open fire, and each had a

great plateful of nuts, raisins, figs, and candy. Then grandma told us

all about when she was a little girl,—what funny dresses she wore,

what strange houses people lived in, and how they were furnished; and[188]

she remembered a little about the Revolutionary war, and the dark day,

and Gen. Washington, and the Indians.

"When grandma grew very old, she came to live with my mother.

My uncle in Florida used to send her oranges and other nice fruit; and

my pretty aunt Eleanor in New York gave her all her caps and fine

muslin neckerchiefs. All her sons and daughters were very thoughtful

for her happiness.

"By and by she fell asleep, and there was a funeral at our house one

lovely day in early autumn. It did not seem sad or gloomy. We

returned from the quiet country graveyard in the twilight of the beautiful

day, and gathered in grandma's pleasant room, and talked with tears

and smiles of her long and useful life."

"What a good grandmother!" said Ralph, almost tearfully.

"I wish I could have seen her just once."

We have had the picture framed, and it hangs in my

boys' room now; and often in the early morning, as I linger

on the stairs, I hear them tell in a very familiar way all

they have learned of Ralph's great-grandmother.

SARAH THAXTER THAYER.

JUNE.

|

My sister May

Has gone away

With April and his showers.

I come apace

To take her place.

Accept my gift of flowers!

|

Transcriber's Notes: Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The original text for the January issue had a table of contents

that spanned six issues. This was divided amongst those issues.

Additionally, only the January issue had a title page. This page

was copied for the remaining five issues. Each issue had the number

added on the title page after the Volume number.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 40757 ***