J. Webster

BOSTON

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

New York: 11 East Seventeenth Street

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1884

Copyright, 1884,

By ELIZABETH KARR.

All rights reserved.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge:

Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton & Co.

In presenting this volume to the women of America, the author would remark that, at least as far as she is aware, it is the first one, exclusively devoted to the instruction of lady riders, that has ever been written by one of their own countrywomen. In its preparation, no pretension is made to the style of a practiced author, the writer freely acknowledging it to be her first venture in the (to her) hitherto unexplored regions of authorship; she has simply undertaken,—being guided and aided by her own experience in horseback riding,—to write, in plain and comprehensive language, and in as concise a manner as is compatible with a clear understanding of her subject, all that she deems it essential for a horsewoman to know. This she has endeavored to do without any affectation or effort to acquire reputation as an author, and wholly for the purpose of benefiting those of her own sex who wish to learn not only to ride, but to ride well. She has also[iv] been induced to prepare the work by the urgent solicitations of many lady friends, who, desirous of having thorough information on horseback riding, were unable to find in any single work those instructions which they needed.

Many valuable works relating to the subject could be had, but none especially for ladies. True, in many of these works prepared for equestrians a few pages of remarks or advice to horsewomen could be found, but so scant and limited were they that but little useful and practical information could be gleaned from them. The writers of these works never even dreamed of treating many very important points highly essential to the horsewoman; and, indeed, it could hardly be expected that they would, as it is almost impossible for any horseman to know, much less to comprehend, these points. The position of a man in the saddle is natural and easy, while that of a woman is artificial, one-sided, and less readily acquired; that which he can accomplish with facility is for her impossible or extremely difficult, as her position lessens her command over the horse, and obliges her to depend almost entirely upon her skill and address for the means of controlling him.

If a gentleman will place himself upon the[v] side-saddle and for a short time ride the several gaits of his horse, he will have many points presented which he had not anticipated, and which may puzzle him; that which appeared simple and easy when in his natural position will become difficult of performance when he assumes the rôle of a horsewoman. A trial of this kind will demonstrate to him that the rules applicable to the one will not invariably be adapted to the other. The reader need not be surprised, therefore, if in the perusal of this volume she discovers in certain instances instructions laid down which differ from those met with in the popular works upon this subject by male authors.

Another inducement to prepare this volume existed in the fact that the ladies throughout the country, and especially in our large cities and towns, are apparently awakening to an appreciation of the importance of out-door amusement and exercise in securing and prolonging health, strength, beauty, and symmetry of form, and that horseback riding is rapidly becoming the favorite form of such exercise. Instructions relating to riding have become, therefore, imperative, in order to supply a need long felt by those horsewomen who, when in the saddle, are desirous of acquitting themselves[vi] with credit, but who have heretofore been unable to gain that information which would enable them to ride with ease and grace, and to manage their steeds with dexterity and confidence. The author—who has had several years' experience in horseback riding with the old-fashioned, two-pommeled saddle, and, in later years, with the English saddle, besides having had the benefit of the best continental teaching—believes she will be accused of neither vanity nor egotism when she states that within the pages of this work instructions will be found amply sufficient to enable any lady who attends to them to ride with artistic correctness.

Great care has been taken to enter upon and elucidate all those minute but important details which are so essential, but which, because they are so simple, are usually passed over without notice or explanation. Especial attention has also been given to the errors of inexperienced and uneducated riders, as well as to the mistakes into which beginners are apt to fall from incorrect modes of teaching, or from no instruction at all; these errors have been carefully pointed out, and the methods for correcting them explained. A constant effort has been made to have these practical hints and valuable[vii] explanations as lucid as possible, that they may readily be comprehended and put into practical use by the reader.

From the fact that considerable gossip, including some truth, as to illiteracy, rudeness, offensive familiarity, and scandal of various kinds has in past years been associated with some of the riding-schools established in our cities, many ladies entertain a decided antipathy to all riding-schools; to these ladies, as well as to those who are living in places where no riding-schools exist, the author feels confident that this work will prove of great practical utility. Yet she must remark that, in her opinion, it is neither just nor right to ostracize indiscriminately all such schools, simply because some of them have proven blameworthy; whenever a riding-school of good standing is established and is conducted by a well-known, competent, and gentlemanly teacher, with one or more skilled lady assistants, she would advise the ladies of the neighborhood to avail themselves of such opportunity to become sooner thorough and efficient horsewomen by pursuing the instructions given in this work under such qualified teachers.

ELIZABETH KARR.

North Bend, Ohio.

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| PAGE | |

| Utility, health, and enjoyment, in horseback riding.—Affection of the horse for a kind mistress.—Incorrect views entertained by ladies relative to horses and horseback riding.—Tight lacing incompatible with correct riding.—Advantages of good riding-schools.—Instinct not a sufficient guide.—Compatibility of refinement and horseback riding.—Importance of out-of-door exercise. | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. THE HORSE. | |

| Origin and countries of the horse.—Earliest Scriptural mention of the horse.—Caligula's horse.—Horseback riding in the Middle Ages.—The Arab horse and his descendants.—Selection of a horse, and points to be observed.—Suitable gaits for the several conformations of riders.—The fast or running walk.—Various kinds of trotting.—The jog trot undesirable.—Temperament of the horse to be taken into consideration.—Thorough-bred horses.—Low-bred horses.—Traits of thorough and low bred horses.—Purchasing a horse; when to pay for the purchase.—Kindness to the horse instead of brutality.—Advantages of kind treatment of the horse.—Horses properly trained from early colt-life, the best.—Certain requirements in training a horse for a lady.—Ladies should visit their horses in the stable.—Ladies of refinement, occupying[x] the highest positions in the civilized and fashionable world, personally attend to their horses.—Nature of the horse.—Unreliable grooms; their vicious course with horses intrusted to their care.—Care required in riding livery-stable horses. | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. THE RIDING HABIT. | |

| Riding habit should not be gaudy.—Instructions concerning the material for riding habit, and how this should be made.—The waist.—The basque or jacket.—Length of riding habit.—White material not to be worn on horseback.—Riding shirt.—Riding drawers.—Riding boots.—Riding corset.—Riding coiffure or head-dress.—Riding hat.—Minutiæ to be attended to in the riding costume.—How to hold the riding skirt while standing.—Riding whip. | 52 |

| CHAPTER III. THE SADDLE AND BRIDLE. | |

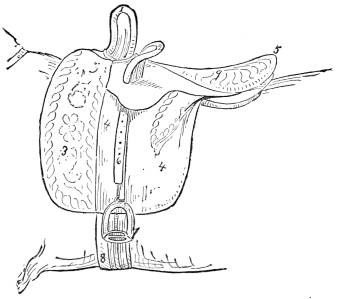

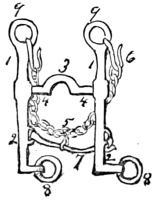

| Saddle of ancient times, and the manner of riding.—Planchette.—Catherine de Medici deviser of the two-pommeled saddle.—M. Pellier, Sr., inventor of the third pommel.—English saddle.—Advantages of the third pommel.—Saddle should, invariably, be made and fitted to the horse.—Seat of saddle.—Kinds of saddles for different ladies.—Proper application of the third pommel.—Saddle recommended and used by the author.—Points to be attended to in procuring a saddle.—Girths.—New mode of tightening girths.—Stirrups and stirrup-leathers.—Safety stirrups.—How to attach the stirrup-leather.—The bridle and reins.—Martingales.—Snaffle-bits.—Curb-bits.—Curb-chain.—Tricks of horses with bits, and[xi] their remedy.—Adjustment of the bit and head-stall.—Care of the bit.—How to correctly place the saddle on the horse.—Remarks concerning girthing the horse.—Great advantages derived from knowing how to saddle and bridle one's horse. | 67 |

| CHAPTER IV. MOUNTING AND DISMOUNTING. | |

| Timidity in presence of a horse should be overcome.—First attempts at mounting.—Mounting from a horse-block.—Mounting from the ground.—Mounting with assistance from a gentleman; how this is effected.—What the gentleman must do.—A restive horse while mounting; how to be managed.—Attractiveness of correct mounting.—To dismount with assistance from a gentleman; what the gentleman must do.—Attentions to the skirt both while mounting and dismounting.—Dismounting without aid; upon the ground; upon a very low horse-block.—Concluding remarks. | 99 |

| CHAPTER V. THE SEAT ON HORSEBACK. | |

| The absolute necessity for a correct seat.—Natural riders rarely acquire a correct seat.—The dead-weight seat.—The wabbling seat.—Essential to good and graceful riding that the body be held square and erect.—The correct seat.—Proper attitude for the body, shoulders, waist, arms, hands, knees, and legs, when on horseback.—Uses and advantages of the third pommel.—Lessons in position should always be taken by the novice in horseback riding.—Faulty positions of ladies called "excellent equestriennes," pointed out at an imaginary park.—Remarks concerning the improper use of stirrups and pommels.—Pupils and teachers frequently in erroneous positions toward each[xii] other.—Obstinacy of some pupils, and wrong ideas of others.—Ladies should not be in too much haste to become riders before they understand all the elementary and necessary requirements; but should advance carefully, attentively, and thoroughly.—Suggestions to teachers of ladies in equitation. | 114 |

| CHAPTER VI. HOLDING THE REINS, AND MANAGING THE HORSE. | |

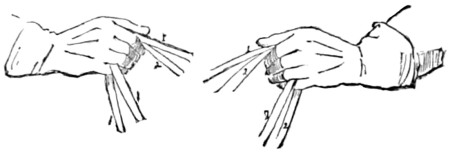

| A thorough knowledge of the management of the horse highly necessary for a lady.—Position in the saddle has an important influence.—Horses generally more gentle with women than with men.—Position should be acquired first, and afterwards the reins be used.—How to hold the hands and snaffle-reins, in first lessons.—To turn the horse to the right, to the left, to back him, to stop him, with a snaffle-rein in each hand.—Manner of holding the snaffle-reins in the bridle-hand; to turn the horse to either side; to back, and to stop him.—To change the snaffle-reins from the left to the right hand; to reinstate them in the bridle-hand.—To separate the snaffle-reins; to shorten or lengthen them.—To hold the curb and bridoon, or double bridle-reins; to shorten or lengthen them; to shorten the curb and lengthen the snaffle-reins; to shorten the snaffle and lengthen the curb-reins.—To tighten a rein that has become loose.—To change the double bridle from the left to the right hand; to return it to the left hand.—Management of reins when making quick turns.—European manner of holding the double bridle-reins, a pair in each hand.—The equestrienne should practice and perfect herself in these various manœuvrings with the reins.—The proper rein-hold creates a correspondence between the rider's hand and the horse's mouth, and gives support to the animal.—Give and take movements—The dead-pull.—In collecting the horse the curb must be used.—The[xiii] secret of good riding.—The management of the reins with restive horses.—Liberty of the reins sometimes necessary.—Movements of horse and rider should correspond.—Horse united or collected.—Horse disunited.—To animate the horse.—To soothe the horse.—What to do in certain improper movements of the horse.—Concluding remarks. | 145 |

| CHAPTER VII. THE WALK. | |

| The movements of the horse in walking.—A good walk is a certain basis for perfection in other gaits.—A lady's horse should be especially trained to walk well.—Every change in the walk, as turning, backing, and stopping, should be well learned, before attempting to ride in a faster gait.—The walk is a gait more especially desirable for some ladies.—The advance, the turn, the stop, the reining back, in the walk.—Remarks on the reining back. | 181 |

| CHAPTER VIII. THE TROT, THE AMBLE, THE PACE, THE RACK. | |

| The movements of the horse in trotting.—The trot a safe gait for a lady.—The jog trot.—The racing trot.—The true trot.—The French trot.—The English trot; is desirable for ladies to learn.—Objections to the French trot.—How to manage the horse and ride the English trot.—Which is the leading foot of the horse in the trot.—To[xiv] stop a horse in the English trot.—Trotting in a circle.—Circling to the right, to the left.—The amble.—The pace.—The rack. | 197 |

| CHAPTER IX. THE CANTER. | |

| Leading with the right foot, with the left foot.—The rapid gallop.—The canter.—The true canter.—To commence the canter; position of the rider, and management of the horse.—To canter with the right leg leading.—To canter with the left leg leading.—To determine with which leg the horse is leading in the canter.—To change from the trot to the canter.—To turn in the canter, to the right, to the left.—Management of the horse while making a turn in the canter.—To stop in the canter.—Remarks concerning position in the canter. | 221 |

| CHAPTER X. THE HAND GALLOP, THE FLYING GALLOP. | |

| The hand gallop, a favorite gait with ladies.—Position and management of the reins, in the hand gallop.—Cautions to ladies when riding the hand gallop.—To manage a disobedient horse during the hand gallop.—Turning when riding the hand gallop.—Position of rider while turning in the hand gallop.—The flying gallop an exercise for country roads.—Cautions to ladies previous to riding the flying gallop.—Holding the reins, position of the rider, and management of the horse, in the flying gallop.—To stop in the flying gallop.—Concluding remarks. | 238 |

| CHAPTER XI. THE LEAP, THE STANDING LEAP, THE FLYING LEAP. | |

| Advantages of learning to leap.—Requisites necessary in leaping.—The standing leap.—Position of the rider, rein-hold, and management of the horse, in the standing leap.—Points to be carefully observed in the leap.—How to make the horse leap.—Management of the reins and of[xv] the rider's position during the leap.—Counsels which should be well learned by the rider before attempting the leap, and especially as to the management of the horse.—How to train a horse to leap.—A lady should never attempt the leap, except with a horse well trained in it.—Horses do not all leap alike.—The flying leap.—Important points to know relative to the flying leap. | 249 |

| CHAPTER XII. DEFENSES OF THE HORSE, CRITICAL SITUATIONS. | |

| A lady's horse should be gentle, well-trained, and possess no vice.—Shying, and its treatment.—Shying sometimes due to defective vision, and at other times to discontent.—Balking, and its treatment.—Backing, and its treatment.—Gayety.—Kicking, and its remedy. An attention to the position and motions of the horse's ears will determine what he is about to do.—Plunging; bucking; what to do in these cases.—Rearing, and the course to be pursued.—Running away, and the course to be pursued.—Unsteadiness of the horse while being mounted, and how to correct it.—Stumbling, and its treatment.—What to do when the horse falls.—Remarks concerning the use of the whip and spur.—Be generous to the horse when he yields to his rider. | 271 |

| ADDENDA. | |

| Thirty-four points necessary to be learned, and to be well understood by equestriennes.—Conclusion. | 301 |

| GLOSSARY | 313 |

| INDEX | 319 |

The Chase.

Among ladies of wealth and culture in England, the equestrienne art forms a portion of their education as much as the knowledge of their own language, of French, or of music, and great care is taken that their acquirements in this art shall be as thorough as those in any other branch of their tuition. The mother bestows much of her own personal supervision on her daughter's instruction, closely watching for every little fault, and promptly correcting it when any becomes manifest. As a result universally acknowledged, a young English lady, when riding a well-trained and spirited horse, is a sight at once elegant and attractive. She exhibits a degree of confidence, a firmness of seat, and an ease and grace that can be acquired only by the most careful and correct[2] instruction. The fair rider guides her steed, without abruptness, from walk to canter, from canter to trot, every movement in perfect harmony; horse and rider being, as it were, of one thought.

"Each look, each motion, awakes a new-born grace."

Unfortunately, at the present day, from want of careful study of the subject, the majority of American lady riders, notwithstanding the elegance of their forms and their natural grace, by no means equal their English sisters in the art of riding. In most instances, a faulty position in the saddle, an unsteadiness of seat, and a lack of sympathy between horse and rider, occasion in the mind of the spectator a sense of uneasiness lest the horse, in making playful movements, or, perhaps, becoming slightly fractious, may unseat his rider,—a feeling which quite destroys the charm and fascination she might otherwise exercise. If my countrywomen would but make a master stroke, and add correct horseback riding to the long list of accomplishments which they now possess, they would become irresistible, and while delighting others, would likewise promote their own physical well-being. There is no cosmetic nor physician's skill which can preserve the bloom and freshness of youth as riding can,[3] and my fair readers, if they wish to prolong those charms for which they are world renowned, charms whose only fault is their too fleeting existence, must take exercise, and be more in the fresh air and sunshine.

How much better to keep old age at bay by these innocent means, than to resort to measures which give to the eye of the world a counterfeit youth that will not deceive for a moment. Even an elderly lady may without offense or harsh criticism recall some of the past joys of younger years by an occasional ride for health or recreation, and, while gracefully accepting her half century, or more, of life, she can still retain some of the freshness and spirit of bygone years.

Not only is health preserved and life prolonged by exercise on horseback, but, in addition, sickness is banished, or meliorated, and melancholy, that dark demon which occasionally haunts even the most joyous life, is overcome and driven back to the dark shades from whence it came. Should the reader have the good fortune to possess an intelligent horse, she can, when assailed by sorrows real or fancied, turn to this true, willing friend, whose affectionate neigh of greeting as she approaches, and whose pretty little graceful arts, will tend[4] to dispel her gloom, and, once in the saddle, speeding along through the freshening air, fancied griefs are soon forgotten, while strength and nerve are gained to face those troubles of a more serious nature, whose existence cannot be ignored.

To the mistress who thoroughly understands the art of managing him, the horse gives his entire affection and obedience, becomes her most willing slave, submits to all her whims, and is proud and happy under her rule.

In disposition the horse is much like a child. Both are governed by kindness combined with firmness; both meet indifference with indifference, but return tenfold in love and obedience any care or affection that is bestowed upon them. The horse also resembles the child in the keenness with which he detects hypocrisy; no pretense of love or interest will impose on either.

To the lady rider who has neither real fondness for her horse nor knowledge of governing him, there is left but one resource by means of which the animal can be controlled, and this is the passion of fear. With a determined will, she may, by whipping, force him to obey, but this means is not always reliable, especially with a high-spirited animal, nor is it a method[5] which any true woman would care to employ. If, in addition to indifference to the horse, there be added nervousness and timidity, which she finds herself unable to overcome by practice and association, the lady might as well relinquish all attempt to become a rider.

Should any of my readers think that these views of the relations between horse and rider are too sentimental, that all which is needed in a horse is easy movement, obedience to the reins, and readiness to go forward when urged, and that love and respect are quite unnecessary, she will find, should she ever meet with any really alarming object on the road, that a little of this despised affection and confidence is very desirable, for, in the moment of danger, the voice which has never spoken in caressing accents, nor sought to win confidence will be unheeded; fear will prevail over careful training, and the rider will be very fortunate if she escapes without an accident. The writer is sustained in the idea that the affection of the horse is essential to the safety of the rider, not only by her own experience, but also by that of some of the most eminent teachers of riding, and trainers of horses.

Maud S. is an example of what a firm yet kind rule will effect in bringing forth the[6] capabilities of a horse. She has never had a harsh word spoken to her, and has never been punished with the whip, but has, on the contrary, been trained with the most patient and loving care; and the result has been a speed so marvelous as to have positively astonished the world, for although naturally high tempered, she will strain every nerve to please her kind, loving master, when urged forward by his voice alone.

Some ladies acquire a dislike for horseback riding, either because they experience discomfort or uneasiness when in the saddle, or because the movements of their horses cause them considerable fatigue. There may be various reasons for this: the saddle may be too large, or too small, or improperly made; or the rider's position in the saddle may be incorrect, and as a consequence, the animal cannot be brought to his best paces. Discomfort may occasionally be caused by an improperly made riding-habit. The rider whose waist is confined by tight lacing cannot adapt herself to the motions of her horse, and the graceful pliancy so essential to good riding will, therefore, be lost. The lady who wears tight corsets can never become a thorough rider, nor will the exercise of riding give her either pleasure or health. She may[7] manage to look well when riding at a gait no faster than a walk, but, beyond this, her motions will appear rigid and uncomfortable. A quick pace will induce rapid circulation, and the blood, checked at the waist, will, like a stream which has met with an obstacle in its course, turn into other channels, rushing either to the heart, causing faintness, or to the head, producing headache and vertigo. There have even been instances of a serious nature, where expectoration of blood has been occasioned by horseback riding, when the rider was tightly laced.

The naturally slender, symmetrical figure, when in the saddle, is the perfection of beauty, but she whom nature has endowed with more ample proportions will never attain this perfection by pinching her waist in. Let the full figure be left to nature, its owner sitting well in the saddle, on a horse adapted to her style, and she will make a very imposing appearance, and prove a formidable rival to her more slender companion.

There is a mistaken idea prevalent among certain persons, that horseback riding induces obesity. It is true that, to a certain extent, riding favors healthy muscular development, but the same may be said of all kinds of exercise,[8] and this effect, far from being objectionable, is highly desirable, as it contributes to symmetry of form, as well as to health and strength, conditions that in a large proportion of our American women are unfortunately lacking. Those who ride on horseback will find that while gaining in strength and proper physical tissue, they will, at the same time, as a rule, be gradually losing all excess of flesh; it is impossible for an active rider to become fat or flabby; but the indolent woman who is prejudiced against exercise of any kind will soon find the much dreaded calamity, corpulency, overtaking her, and beauty of form more or less rapidly disappearing beneath a mountain of flesh.

There are many persons who entertain the mistaken idea that instinct is a sufficient guide in learning to ride; that it is quite unnecessary to take any lessons or to make a study of the art of correct riding; and that youth, a good figure, and practice are all that is required to make a finished rider. This is a most erroneous opinion, which has been productive of much harm to lady riders. The above qualifications are undoubtedly great assistants, but without correct instruction they will never produce an accomplished and graceful rider.

The instinctive horsewoman usually rides[9] boldly and with perfect satisfaction to herself, but to the eye of the connoisseur she presents many glaring defects. Very bold, but, at the same time, very bad riding is often seen among those who consider themselves very fine horsewomen. In order to gain the reputation of a finished rider, it is not essential that one should perform all the antics of a circus rider, nor that she should ride a Mazeppian horse. The finished rider may be known by the correctness of her attitude in the saddle, by her complete control of her horse, and by the tranquillity of her motions when in city or park; in such places she makes no attempt to ride at a very rapid trot, or flying gallop-gaits which should be reserved for country roads, where more speed is allowable.

There is still another false idea prevalent among a certain class of people, which is that a love for horses, and for horseback riding necessarily makes one coarse, and detracts from the refinement of a woman's nature. It must be acknowledged that the coarseness of a vulgar spirit can be nowhere more conspicuously displayed than in the saddle, and yet in no place is the delicacy and decorum of woman more observable. A person on horseback is placed in a position where every motion is subject[10] to critical observation and comment. The quiet, simple costume, the easy movements, the absence of ostentatious display, will always proclaim the refined, well-bred rider. Rudeness in the saddle is as much out of place as in the parlor or salon, and greatly more annoying to spectators, besides being disrespectful and dangerous to other riders. Abrupt movements, awkward and rapid paces, frequently cause neighboring horses to become restless, and even to run away. Because a lady loves her horse, and enjoys riding him, it is by no means necessary that she should become a Lady Gay Spanker, indulge in stable talk, make familiars of grooms and stable boys, or follow the hounds in the hunting field.

There are in this work no especial instructions given for the hunting field, as the author does not consider it a suitable place for a lady rider. She believes that no lady should risk life and limb in leaping high and dangerous obstacles, but that all such daring feats should be left to the other sex or to circus actresses. Nor would any woman who really cared for her horse wish to run the risk of reducing him to the deplorable condition of many horses that follow the hounds. In England, where hunting is the favorite pastime among gentlemen, the[11] number of maimed and crippled horses that one meets is disheartening. Every lady, however, who desires to become a finished rider, should learn to leap, as this will not only aid her in securing a good seat in the saddle, but may also prove of value in times of danger.

Before concluding I would again urge upon my readers the importance of out-of-door exercise, which can hardly be taken in a more agreeable form than that of horseback riding,—a great panacea, giving rest and refreshment to the overworked brain of the student, counteracting many of the pernicious effects of the luxurious lives of the wealthy, and acting upon the workers of the world as a tonic, and as a stimulus to greater exertion.

Venus and Adonis.

It is supposed that the original home of the horse was central Asia, and that all the wild horses that range over the steppes of Tartary, the pampas of South America, and the prairies of North America, are descendants of this Asiatic stock.1 There is, in the history of the[14] world, no accurate statement of the time when the horse was first subjugated by man, but so far back as his career can be traced in the dim and shadowy past, he seems to have been man's servant and companion. We find him, on the mysterious ruins of ancient Egypt, represented with his badge of servitude, the bridle; he figures in myth and fable as the companion of man and gods; he is a prominent figure in the pictured battle scenes of the ancient world; and has always been a favorite theme with poet, historian, and philosopher in all ages.

The first written record, known to us, of the subjection of the horse to man is found in the Bible, where in Genesis (xlvii. 17) it is stated that Joseph gave the Egyptians bread in exchange for their horses, and in 1. 9, we read that when Joseph went to bury his father Jacob, there went with him the servants of the house of Pharaoh, the elders of the land of Egypt, together with "chariots and horsemen" in numbers. Jeremiah compares the speed of the horse with the swiftness of the eagle; and Job's description of the war charger has never been surpassed.

Ancient Rome paid homage to the horse by a[15] yearly festival, when every one abstained from labor, and the day was made one of feasting and frolic. The horse, decked with garlands, and with gay and costly trappings, was led in triumph through the streets, followed by a multitude who loudly proclaimed in verse and song his many good services to man.

This adulation of the horse sometimes went beyond the bounds of reason, as in the case of Caligula, who carried his love for his horse, Incitatus, to an insane degree. He had a marble palace erected for a stable, furnished it with mangers of ivory and gold, and had sentinels guard it at night that the repose of his favorite might not be disturbed. Another elegant palace was fitted up in the most splendid and costly style, and here the animal's visitors were entertained. Caligula required all who called upon himself to visit Incitatus also, and to treat the animal with the same respect and reverence as that observed towards a royal host. This horse was frequently introduced at Caligula's banquets, where he was presented with gilded oats, and with wine from a golden cup. Historians state that Caligula would even have made his steed consul of Rome, had not the tyrant been opportunely assassinated, and the world freed from an insane fiend.

In the legends of the Middle Ages the knight-errant and his gallant steed were inseparable, and together performed doughty deeds of valor and chivalry. In our present more prosaic age, the horse has been trained to such a degree of perfection in speed and motion as was never dreamed of by the ancients or by the knights of the crusades; and there has been given to the world an animal that is a marvel of courage, swiftness, and endurance, while, at the same time, so docile, that the delicate hand of woman can completely control him.

The Arabian is the patrician among horses; he is the most intelligent, the most beautifully formed, and, when kindly treated, the gentlest of his race. He is especially noted for his keenness of perception, his retentive memory, his powers of endurance, and, when harshly or cruelly treated, for his fierce resentment and ferociousness, which nothing but death can conquer. In his Arabian home he is guarded as a treasure, is made one of the family and treated with the most loving care. This close companionship creates an affection and confidence between the horse and his master which is almost unbounded; while the kindness with which the animal is treated seems to brighten his intelligence as well as to render him gentle.

When these horses were first introduced into Europe they seemed, after a short stay in civilization, to have completely changed their nature, and, instead of gentleness and docility, exhibited an almost tiger-like ferocity. This change was at first attributed to difference of climate and high feeding, but, after several grooms had been injured or killed by their charges, it began to be suspected that there was something wrong in the treatment. The experiment of introducing native grooms was therefore tried, and the results proved most satisfactory, the animals once more becoming gentle and docile.2 Since then the nature of the Arabian has become better understood, and,[18] both in this country and in Europe, he shows, at the present day, a decided improvement upon the original native of the desert. He is larger and swifter, yet still retains all the spirit as well as docility of his ancestors. In America his descendants are called "thorough-breds," and Americans may well be proud of this race of horses, which is rapidly becoming world renowned.

Before purchasing a saddle-horse, several points should be considered. First, the style of the rider's figure; for a horse which would be suitable for a large, stout person would not be at all desirable for one having a small, slender figure. A large, majestic looking woman would present a very absurd spectacle when mounted upon a slightly built, slender horse; his narrow back in contrast with that of his rider would cause hers to appear even larger and wider than usual, and thus give her a heavy and ridiculous appearance, while the little horse would look overburdened and miserable, and his step, being too short for his rider, would cause her to experience an unpleasant sensation of embarrassment and restraint. On the other hand, a short, light, slender rider, seated upon a[19] tall broad-backed animal, would appear equally out of place; the step of the horse being, in her case, too long, would make her seat unsteady and insecure, so that instead of a sense of enjoyment, exhilaration, and benefit from the ride, she would experience only fatigue and dissatisfaction.

If the rider be tall and rather plump, the horse should be fifteen hands and three inches in height, and have a somewhat broad back. A lady below the medium height, and of slender proportions, will look equally well when riding a pony fourteen hands high, or a horse fifteen hands. An animal fifteen hands, or fifteen hands and two inches in height, will generally be found suitable for all ladies who are not excessively large and tall, or very short and slender. In all cases, however, the back of the horse should be long enough to appear well under the side-saddle, for a horse with a short back never presents a fine aspect when carrying a woman. In such cases, the side-saddle extends from his withers nearly, if not quite, to his hips, and as the riding skirt covers his left side, little is seen of the horse except his head and tail. Horses with very short backs are usually good weight-carriers, but their gaits are apt to be rough and uneasy.

Another point to be considered in the selection of a horse is, what gait or gaits are best suited to the rider, and here again the lady should take her figure into consideration. The walk, trot, canter, and gallop are the only gaits recognized by English horsewomen, but in America the walk, rack, pace, and canter are the favorite gaits. If the lady's figure be slender and elegant, any of the above named gaits will suit her, but should she be large or stout, a brisk walk or easy canter should be selected. The rapid gallop and all fast gaits should be left to light and active riders.

The fast or running walk is a very desirable gait for any one, but is especially so for middle-aged or stout people, who cannot endure much jolting; it is also excellent for delicate women, for poor riders, or for those who have long journeys to make which they wish to accomplish speedily and without undue fatigue to themselves or their horses. A good sound horse who has been trained to this walk can readily travel thirty or forty miles a day, or even more. This gait is adapted equally well to the street, the park, and the country road; but it must be acknowledged that horses possessing it rarely have any other that is desirable, and, indeed, any other would be apt to impair the ease and[21] harmony of the animal's movements in this walk.

The French or cavalry trot (see page 203) should never be ridden on the road by a woman, as the movements of the horse in this gait are so very rough that the most accomplished rider cannot keep a firm, steady seat. The body is jolted in a peculiar and very unpleasant manner, occasioning a sense of fatigue that is readily appreciated, though difficult to describe.

The country jog-trot is another very fatiguing gait, although farmers, who ride it a good deal, state that "after one gets used to it, it is not at all tiresome." But a lady's seat in the saddle is so different from that of a gentleman's that she can never ride this gait without excessive fatigue.

A rough racker or pacer will prove almost as wearisome as the jog-trotter. Indeed, if she wishes to gain any pleasure or benefit from riding, a lady should never mount a horse that is at all stiff or uneven in his movements, no matter what may be his gait.

The easiest of all gaits to ride, although the most difficult to learn, is the English trot. This is especially adapted to short persons, who can ride it to perfection. A tall woman will be apt to lean too far forward when rising in it, and[22] her specialties, therefore, should be the canter and the gallop, in which she can appear to the greatest advantage. The rack, and the pace of a horse that has easy movements are not at all difficult to learn to ride, and are, consequently, the favorite gaits of poor riders.

In selecting a horse his temperament must also be considered. A high-spirited, nervous animal, full of vitality, highly satisfactory as he might prove to some, would be only a source of misery to others of less courageous dispositions. First lessons in riding should be taken upon a horse of cold temperament and kindly disposition who will resent neither mistakes nor awkwardness. Having learned to ride and to manage a horse properly, no steed can then be too mettlesome for the healthy and active lady pupil, provided he has no vices and possesses the good manners that should always belong to every lady's horse.

It is a great mistake to believe, as many do, that a weak, slightly built horse is yet capable of carrying a woman. On the contrary, a lady's horse should be the soundest and best that can be procured, and should be able to carry with perfect ease a weight much greater than hers. A slight, weak animal, if ridden much by a woman, will be certain to "get out of condition,"[23] will become unsound in the limbs of one side, usually the left, and will soon wear out.

Before buying a horse, the lady who is to ride him should be weighed, and should then have some one who is considerably heavier than herself ride the animal, that she may be sure that her own weight will not be too great for him. If he carries the heavier weight with ease, he can, of course, carry her.

In selecting a horse great care should be taken to ascertain whether there is the least trace of unsoundness in his feet and legs, and especially that variety of unsoundness which occasions stumbling. The best of horses, when going over rough places or when very tired may stumble, and so will indolent horses that are too lazy when traveling to lift their feet up fully; but when this fault is due to disease, or becomes a habit with a lazy animal, he should never be used under the side-saddle.

If the reader will glance at Figs. 1 and 2, she will observe the difference between the head of the low-bred horse and that of the best bred of the race. Fig. 1 represents the head of an Arabian horse; the brain is wide between the eyes, the brow high and prominent, and the expression of the face high-bred and intelligent. Fig. 2 shows the head of a low-bred horse, whose[24] stupid aspect and small brain are very manifest. The one horse will be quick to comprehend what is required of him, and will appreciate any efforts made to brighten his intelligence, while the other will be slow to understand, almost indifferent to the kindness of his master, and apt, when too much indulged, to return treachery for good treatment. The whip, when applied to the latter as a means of punishment, will probably cow him, but, if used for the same purpose on the former, will rouse in him all the hot temper derived from his ancestors, and in the contest which ensues between his master and himself, he will conquer, or terminate the strife his own death, or that of his master.

Another noticeable feature in the Arab horse, and one usually considered significant of an active and wide-awake temperament, is the width and expansiveness of the nostrils. These, upon the least excitement, will quiver and expand, and in a rapid gallop will stand out freely, giving a singularly spirited look to the animal's face.

The shape and size of the ears are also indications of high or low birth. In the high-bred horse they are generally small, thin, and delicate on their outer margins, with the tips inclined somewhat towards one another. By means of these organs the animal expresses his different emotions of anger, fear, dislike, or gayety. They may be termed his language, and their various movements can readily be understood when one takes a little trouble to study their indications. The ears of a low-bred horse are large, thick, and covered with coarse hair; they sometimes lop or droop horizontally, protruding from the sides of the head and giving a very sheepish look to the face; they rarely move, and express very little emotion of any kind.

The eye of the desert steed is very beautiful, possessing all the brilliancy and gentleness so much admired in that of the gazelle. Its expression[26] in repose is one of mildness and amiability, but, under the influence of excitement, it dilates widely and sparkles. A horse which has small eyes set close together, no matter what excellences he may possess in other respects, is sure to have some taint of inferior blood. Some of the coarser breeds have the large eye of the Arabian, but it will usually be found that they have some thorough-bred among their ancestors.

Width between the sides or branches of the lower jaw is another distinctive feature of the horse of pure descent. (Fig. 3.) A wide furrow or channel between the points mentioned is necessary for speed, in order to allow room for free respiration when the animal is in rapid motion. The coarser breeds have very small, narrow channels (Fig. 4), and very rapid motion soon distresses them.

The mouth of the well-bred horse is large, allowing ample room for the bit, and giving him a determined and energetic, but at the same time pleasant,[27] amiable expression. The mouth of the low-bred horse is small and covered with coarse hair, and gives the animal a sulky, dejected appearance.

The light, elegant head of the Arabian is well set on his neck; a slight convexity at the upper part of the throat gives freedom to the functions of this organ, as well as elasticity to the movements of the head and neck; and the encolure, or crest of the neck, is arched with a graceful curve. But it is especially in the shape of the shoulders that this horse excels all others, and this is the secret of those easy movements which make him so desirable for the saddle. These shoulders are deep, and placed obliquely at an angle of about 45°; they act like the springs of a well-made carriage, diminishing the shock or jar of his movements. They are always accompanied by a deep chest, high withers, and fore-legs set well forward, qualities which make the horse much safer for riding. (Fig. 5.)

The animal with straight shoulders, no matter how well shaped in other respects, can never make a good saddle-horse, and should be at[28] once rejected. These shoulders are usually accompanied by low withers, and fore-legs placed too far under the body, which arrangement causes the rider an unpleasant jar every time a fore-foot touches the ground. Moreover, the gait of the horse is constrained and not always safe, and if he be used much under the saddle his fore-feet will soon become unsound. This straight, upright shoulder is characteristic of the coarser breeds of horses, and is frequently associated with a short, thick neck. Such horses are not only unfit for the saddle, but, when any speed is desired, are unsuitable even for a pleasure carriage. (Fig. 6.)

The haunch of the low-bred horse is generally large, but not so well formed as that of the thorough-bred. This portion of the Arabian courser is wide, indicating strength, and force to propel himself forward, while his tail, standing out gayly when he is in motion, projects in a line with his back-bone. His forearm is large, long, and muscular,3 his knees broad and firm,[29] his hocks of considerable size, while his cannon-bone, situated between the knee and the fetlock, is short, although presenting a broad appearance when viewed laterally.

On each front leg, at the back of the knee, there is a bony projection, giving attachments to the flexor muscles, and affording protection to certain tendons. The Orientals set a great value upon the presence of this bone, believing that it favors muscular action, and the larger this prominence is the more highly do they prize the animal that possesses it. The pasterns of the high-bred horse are of medium length, and very elastic, while the foot is circular and of moderate size.

In the preceding description, the author has endeavored to make plain to the reader the most important points to be observed in both the high-bred and the low-bred horse, and has given the most pronounced characteristics of each.

Between these extremes, however, there are many varieties of horses, possessing more or less of the Arabian characteristics mingled with those of other races. Some of the best American horses are numbered among these mixed races, and, by many, are considered an improvement upon the Arabian, as they are excellent for light carriages and buggies. The more they resemble the Oriental steed, the better they are for the saddle.

The lady who, in this country, cannot find a horse to suit her, will, indeed, be difficult to please. It will be best for her to tell some gentleman what sort of horse she wishes, and let him select for her; but, at the same time, it can do no harm, and may prove a great advantage to her to know all the requisite points of a good saddle-horse. It will not take long to learn them, and the knowledge gained will prevent her from being imposed upon by the ignorant or unscrupulous. Gentlemen, even those who consider themselves good judges of horse-flesh, are sometimes guilty of very serious blunders in selecting a horse for a lady's use; and should the lady be obliged to negotiate directly with a horse-dealer, she must bear in mind constantly the fact that, although there are reliable and honorable dealers to be found,[31] there are many who would not scruple to cheat even a woman. A careful perusal of the present work, together with the advice of an upright and trustworthy veterinary surgeon, or a skilled riding-master, will aid her in protecting herself from the impositions of unprincipled horse-jockeys and self-styled "veterinary doctors."

In any case, whatever be the other characteristics of the animal selected, be sure that he has the oblique shoulder, as well as depth of shoulder, and hind-legs well bent. Without these characteristics he will be unfit for a lady's use, as his movements will be rough and unsafe, and the saddle will be apt to turn.

If it be desired to purchase a horse for a moderate price, certain points which might be insisted on in a high-priced animal will have to be dispensed with; for instance, his color may not be satisfactory; he may not have a pretty head, or a well-set tail, etc., but these deficiencies may be overlooked if he be sound, have good action, and no vices. He may be handsome, well-actioned, and thoroughly trained, but have a slight defect in his wind, noticeable only when he is urged into a rapid trot, or a gallop. If wanted for street and park service only, and if the purchaser does not care for fast[32] riding, a horse of this sort will suit her very well. Sometimes a horse of good breed, as well as of good form, has never had the advantages of a thorough training, or he may be worn out by excessive work. Should he be comparatively young, rest and proper training may still make a good horse of him, but great care should be taken to assure one's self that no permanent disease or injury exists. The Orientals have a proverb, that it is well to bear in mind when buying an animal of the kind just described:—"Ruin, son of ruin, is he who buys to cure."

Always examine with great care a horse's mouth. A hard-mouthed animal is a very unpleasant one for a lady to ride, and is apt to degenerate into a runaway. Scars at the angles of the mouth are good indications of a "bolter," or runaway, or at least of cruel treatment, and harsh usage is by no means a good instructor.

While a very short-backed horse does not appear to great advantage under a side-saddle, he may, nevertheless, have many good qualities that will compensate for this defect, and it may be overlooked provided the price asked for him be reasonable; but horses of this kind frequently command a high price when their action is exceptionally good. Corns on the feet generally depreciate the value of a horse, although[33] they may sometimes be cured by removing the shoes, and giving him a free run of six or eight months in a pasture of soft ground; if he be then properly shod, and used on country roads only, he may become permanently serviceable. There is, however, considerable risk in buying a horse that has corns, and the purchaser should remember the Oriental proverb just referred to, and not forget the veterinary surgeon.

Before paying for a horse, the lady should insist upon having him on trial for at least a month, that she may have an opportunity of discovering his vices or defects, if any such exist. She must be careful not to condemn him too hastily, and should, when trying him, make due allowance for his change of quarters and also for the novelty of carrying a new rider, as some horses are very nervous until they become well acquainted with their riders. Should the horse's movements prove rough, should he be found hard-mouthed, or should any indications of unsoundness or viciousness be detected, he should be immediately returned to his owner. It must be remembered, however, that very few horses are perfect, and that minor defects may, in most instances, be overlooked if the essentials are secured. Before rejecting the horse,[34] the lady should also be very sure that the faults to which she objects are not due to her own mismanagement of him. But if she decides that she is not at fault, no amount of persuasion should induce her to purchase. In justice to the owner of the horse, he ought to be reasonably paid for the time and services of his rejected animal; but if it be decided to keep the horse, then only the purchase-money originally agreed upon should be paid.

The surest and best way of securing a good saddle-horse is to purchase, from one of the celebrated breeding farms, a well-shaped four-year-old colt of good breed, and have him taught the gaits and style of movement required. Great care should be taken in the selection of his teacher, for if the colt's temper be spoiled by injudicious treatment, he will be completely ruined for a lady's use. A riding-school teacher will generally understand all the requirements necessary for a lady's saddle-horse, and may be safely intrusted with the animal's education. If no riding-school master of established reputation as a trainer can be had, it may be possible to secure the services of some one near the lady's home, as she can then superintend the colt's education herself and be sure that he is treated neither rashly nor cruelly.

The ideas concerning the education of the horse have completely changed within the last twenty-five years. The whip as a means of punishment is entirely dispensed with in the best training schools of the present day, and, instead of rough and brutal measures, kindness, firmness, and patience are now the only means employed to train and govern him. The theory of this modern system of training may be found in the following explanation of a celebrated English trainer, who subdued his horses by exhibiting towards them a wonderful degree of patience:—"If I enter into a contest with the horse, he will fling and prance, and there will be no knowing which will be master; whereas if I remain quiet and determined, I have the best of it."

The following is an example of the patience with which this man carried out his theory:—

Being once mounted on a very obstinate colt that refused to move in the direction desired, he declined all suggestions of severe measures, and after one or two gentle but fruitless attempts to make the animal move, he desisted, and having called for his pipe, sat there quietly for a couple of hours enjoying a good smoke, and chatting gayly with passing friends. Then after another quiet but unsuccessful attempt[36] to induce the colt to move, he sent for some dinner which he ate while still on the animal's back. As night approached and the air became cool, he sent for his overcoat and more tobacco, and proceeded to make a night of it. About this time the colt became uneasy, but not until midnight did he show any disposition to move in the required direction. Now was the time for the master to assert himself. "Whoa!" he cried, "you have stayed here so long to please yourself, now you will stay a little longer to please me." He then kept the colt standing in the same place an hour longer, and when he finally allowed him to move, it was in a direction opposite to that which the colt seemed disposed to take. He walked the animal slowly for five miles, then allowed him to trot back to his stable, and finally—as if he had been a disobedient child—sent him supperless to bed, giving him the rest of the night in which to meditate upon the effects of his obstinacy.

To some this may seem a great deal of useless trouble to take with a colt that might have been compelled to move more promptly by means of whip or spur; but that day's experience completely subdued the colt's stubborn spirit, and all idea of rebellion to human authority was banished from his mind forever.[37] Had a contrary course been pursued, it would probably have made the creature headstrong, balky, and unreliable; he would have yielded to the whip and spur at one time only to battle the more fiercely against them at the first favorable opportunity, and his master would never have known at what minute he might have to enter into a contest with him. That a horse trained by violent means can never be trusted is a fact which is every day becoming better recognized and appreciated.

"A great many accidents might be avoided," says a well-known authority upon the education of the horse, "could the populace be instructed to think a horse was endowed with senses, was gifted with feelings, and was able in some degree to appreciate motives."... "The strongest man cannot physically contend against the weakest horse. Man's power reposes in better attributes than any which reside in thews and muscles. Reason alone should dictate and control his conduct. Thus guided, mortals have subdued the elements. For power, when mental, is without limit: by savage violence nothing is attained and man is often humbled."

The lady who has the good fortune to live in the country where she can have so many opportunities for studying the disposition and[38] character of her animals, and can, if she chooses, watch and superintend the education of her horse from the time he is a colt, has undoubtedly a better chance of securing a fine saddle-horse than she who lives in the city and is obliged to depend almost entirely upon others for the training of her horse. Indeed, very little formal training will be necessary for a horse that has been brought up under the eye of a kind and judicious mistress, for he will soon learn to understand and obey the wishes of one whom he loves and trusts, and if she be an accomplished rider she can do the greater part of the training herself.

The best and most trustworthy horse the author ever had was one that was trained almost from his birth. Fay's advent was a welcome event to the children of the family, by whom he was immediately claimed and used as a play-fellow. By the older members of the family he was always regarded as part of the household,—an honored servant, to be well cared for,—and he was petted and fondled by all, from paterfamilias down to Bridget in the kitchen. He was taught, among other tricks, to bow politely when anything nice was given him, and many were the journeys he made around to the kitchen window, where he would make[39] his obeisance in such an irresistible manner that Bridget would be completely captivated; and the dainty bits were passed through the window in such quantities and were swallowed with such avidity that the lady of the house had to interfere and restrict the donations to two cakes daily.

Fay had been taught to shake hands with his admirers, and this trick was called his "word of honor;" he had his likes and dislikes, and would positively refuse to honor some people with a hand-shake. If these slighted individuals insisted upon riding him, he made them so uncomfortable by the roughness of his gaits that they never cared to repeat the experiment. But the favored ones, whom he had received into his good graces and to whom he had given his "word of honor," he would carry safely anywhere, at his lightest and easiest gait. Fay never went back on his word, which is more than can be said of some human beings.

The great difficulty in training a horse for a lady's use is to get him well placed on his haunches. In Fay's case this was accomplished by teaching him to place his fore-feet upon a stout inverted tub, about two feet high. When he offered his "hand" for a shake, some one pushed forward the tub, upon which his "foot"[40] dropped and was allowed to remain a short time, when the other foot was treated in the same manner. After half a dozen lessons of this sort, he learned to put up his feet without assistance; first one, and then the other, and, finally, both at once. These performances were always rewarded by a piece of apple or cake, together with expressions of pleasure from the by-standers. Fay had a weakness for flattery, and no actor called before the curtain ever expressed more pleasure at an encore than did Fay when applauded for his efforts to please. That the tub trick would prove equally effectual with other horses in teaching them to place themselves well on their haunches cannot be positively stated. It might prove more troublesome to teach most horses this trick than to have them placed upon their haunches in the usual way by means of a strong curb, or by lessons with the lunge line. It proved entirely successful in Fay's case, and a horse lighter in hand or easier in gait was never ridden by a woman.

Fay's training began when he was only a few weeks old: a light halter and a loose calico surcingle were placed on him for a short time each day, during which time he was carefully watched lest he should do himself some injury. When[41] he was about eight months old, a small bit, made of a smooth stick of licorice, was put into his mouth, and to this bit light leather reins were fastened by pieces of elastic rubber: this rubber relieved his mouth from a constant dead pull, and tended to preserve its delicate sensibility. Thus harnessed he was led around the lawn, followed by a crowd of youthful admirers and playmates, who formed a sort of triumphal procession, with which the colt was as well pleased as the spectators. Every attempt on his part to indulge in horse-play, such as biting, kicking, etc., was always quickly checked, and no one was allowed to tease or strike him.

Nothing heavier than a dumb jockey was put on his back until he was four years old, when his education began in sober earnest. After a few lessons with the lunge line, given by a regular trainer, a saddle was put on his back, and for the first time in his life he carried a human being.

When learning his different riding gaits on the road, he was always accompanied by a well-trained saddle-horse, aided by whose example as well as by the efforts of his rider he was soon trained in three different styles of movement, namely, a good walk, trot, and hand gallop. Fear seemed unknown to this horse, for he had[42] always been allowed as a colt to follow his dam on the road, and had thus become so accustomed to all such alarming objects as steam engines, hay carts, etc., that they had ceased to occasion him the least uneasiness. This high spirited and courageous animal had perfect confidence in the world and looked upon all mankind as friendly. His constant companionship with human beings had sharpened his perceptive faculties, and made him quick to understand whatever was required of him. The kindness shown him was never allowed to degenerate into weakness or over-indulgence, and whenever anything was required of him it was insisted upon until complete obedience was obtained. In this way he was taught to understand that man was his master and superior.

Although it is not absolutely essential that a lady's horse should learn the tricks of bowing, hand-shaking, etc., yet the lady who will take the pains to teach her horse some of them will find that she not only gets a great deal of pleasure from the lessons, but that they enable her to gain more complete control over him, for the horse, like some other animals, gives affection and entire obedience to the person who makes an effort to increase his intelligence.

Lessons with the lunge line should always be[43] short, as they are very fatiguing to a young colt, and when given too often or for too great a length of time they make him giddy from rush of blood to the head; not a few instances, indeed, have occurred where a persistence in such lessons has occasioned complete blindness.

A lady's horse should be taught to disregard the flapping of the riding-skirt, and it is also well for him to become accustomed to having articles of various kinds, such as pieces of cloth, paper, etc., fluttering about him, as he will not then be likely to take fright should any part of the rider's costume become disarranged and blow about him.

He should also be so trained that he will not mind having the saddle moved from side to side on his back. The best of riders may have her saddle turn, and if the horse be thus trained he will neither kick nor run away should such an accident occur.

It is also very important that the horse should be taught to stop, and stand as firm as a rock at the word of command given in a low, firm tone. This habit is not only important in mounting and dismounting,—feats which it is difficult, if not impossible, for the lady to perform unless the horse be perfectly still,—but the rider will also find this prompt obedience of[44] great assistance in checking her horse when he becomes frightened and tries to break away; for he will stop instinctively when he hears the familiar order given in the voice to which he is accustomed.

A lady should not fail to visit her horse's stable from time to time, in order to assure herself that he is well treated and properly cared for by the groom. Viciousness and restlessness on the road can often be traced to annoyances and ill-treatment in the stable. Grooms and stable boys sometimes like to see the horse kick out and attempt to bite, and will while away their idle hours in harassing him, tickling his ears with straws, or touching him up with the whip in order to make him prance and strike out. The result of these annoyances will be that, if the lady during her ride accidentally touches her horse with the whip, he will begin prancing and kicking; or, if it is summer time, the gnats and flies swarming about his ears will make him unmanageable. In the latter case, ear-tips will only make the matter worse, especially if they have dangling tassels. When such signs of nervousness are noticeable, especially in a horse that has been hitherto gentle, they may usually be attributed to the treatment of the groom or his assistants.

Most grooms delight in currying their charges with combs having teeth like small spikes and in laying on the polishing brush with a hand as heavy as the blows of misfortune. Some animals, it is true, like this kind of rubbing, but there are many, who have thin, delicate skins, to whom such treatment is almost unmitigated torture. Should the lady hear any contest going on between the horse and groom during the former's morning toilette, she should order a blunt curry-comb to be used; or even dispense with a comb altogether, and let the brush only be applied with a light hand. Grooms sometimes take pleasure in throwing cold water over their horses. In very warm weather, and when the animal is not overheated, this treatment may prove refreshing to him, but, as a general rule it is objectionable, as it is apt to occasion a sudden chill which may result in serious consequences.

The stable man may grumble at the lady's interference and supervision, but she must not allow this to prevent her from attending carefully to the welfare of the animal whose faithful services contribute so largely to her pleasure. When she buys a horse she introduces a new member into her household, who should be as well looked after and cared for as any other[46] faithful servant or friend. Indeed, the horse is the more entitled to consideration in that he is entirely helpless, and his lot for good or evil lies wholly in her power. If the mistress is careless or neglects her duty, the servants in whose charge the horse is placed will be very apt to follow her example, and the poor animal will suffer accordingly.

Perhaps the lady, however, may object to entering the stable, and agree with the groom in thinking it "no place for a woman." Or she may fear that in carrying out the ideas suggested above she will expose herself to the ridicule of thoughtless acquaintances who can never do anything until it has received the sanction of fashion.

For the benefit of this fastidious individual and her timid friends we will quote the example of the Empress of Austria, who, although occupying an exalted position at a court where etiquette is carried to the extremes of formality, yet does not hesitate to visit the stable of her favorite steeds and personally to supervise their welfare; and woe to the perverse groom who in the least particular disobeys her commands.

Many other examples might be given of high-born ladies, such as Queen Victoria, the Princess of Wales, the Princess of Prussia, and[47] others, who do not seem to consider it at all unfeminine or coarse for a woman to give some personal care and supervision to her horses. But to enter into more details would prove tiresome, and the example given is enough to silence the scruples of the followers of fashion.

Like all herbivorous creatures that love to roam in herds, the horse is naturally of a restless temperament. Activity is the delight of his existence, and when left to nature and a free life he is seldom quiet. Man takes this creature of buoyant nature from the freedom of its natural life, and confines the active body in a prison house where its movements are even more circumscribed than are those of the wild beasts in the menagerie; they can at least turn around and walk from side to side in their cages, but the horse in his narrow stall is able only to move his head from side to side, to paw a little with his fore-feet, and to move backwards and forwards a short distance, varying with the length of his halter; when he lies down to sleep he is compelled to keep in one position, and runs the risk of meeting with some serious accident. In some stables where the grooms delight in general stagnation, the horses under their charge are not allowed to indulge in even the smallest liberty. The slightest movement[48] is punished by the lash of these silence-loving tyrants, in whose opinion the horse has enough occupation and excitement in gazing at the blank boards directly in front of his head. If these boards should happen to be whitewashed, as is often the case in the country, constant gazing at them will be almost sure to give rise to shying, or even to occasion blindness. If the reader will, for several minutes, gaze steadily at a white wall, she will he able to get some idea of the poor horse's sensations.

Is it then to be wondered at, that an animal of an excitable nature like the horse should, when released from the oppressive quiescence of his prison-house, act as if bereft of reason, and perform strange antics and caperings in his insane delight at once more breathing the fresh air, and seeing the outside world. But, while the horse is thus expressing his pleasure and recovering the use of limbs by vigorous kicks, or is expending his superfluous energy by bounding out of the road at every strange object he encounters, the saddle will be neither a safe nor pleasant place for the lady rider. To avoid such danger, and to compensate, in some degree, the liberty-loving animal for depriving him of his natural life and placing him in bondage, he should be given, instead of[49] the usual narrow stall, a box stall, measuring about sixteen or eighteen feet square. In this box the horse should be left entirely free, without even a halter, as this appendage has sometimes been the cause of fearful accidents, by becoming entangled with the horse's feet.

The groom may grumble again at this innovation, because a box stall means more work for him, but if he really cares for the horses under his charge he will soon become reconciled to the small amount of extra work required by the use of a box stall. Every one who knows anything about a horse in the stable is well aware of the injury done to this animal's feet and limbs by compelling him to stand always confined to one spot in a narrow stall. A box will prevent the occurrence of these injuries, besides giving the horse a little freedom and enabling him to get more rest and benefit from his sleep.

Some horses are fond of looking through a window or over a half door. The glimpse they thus get of the outside life seems to amuse and interest them, and it can do no harm to gratify this desire. Others, however, seem to be worried and excited by such outlooks; they become restless and even make attempts to leap over the half door or through the window. In such[50] cases there should, of course, be no out-of-door scenery visible from the box.

The groom should exercise the horse daily, in a gentle and regular manner; an hour or two of walking, varied occasionally by a short trot, will generally be found sufficient. Being self-taught in the art of riding, grooms nearly always have a very heavy bridle hand, and, if allowed to use the curb bit, will soon destroy that sensitiveness of the horse's mouth which adds so much to the pleasure of riding him. The man who exercises the horse should not be permitted to wear spurs; a lady's horse should be guided wholly by the whip and reins,—as will be explained hereafter,—and in no case whatever should the spur be used. If the lady wishes to keep her horse in good health and temper she must insist upon his being exercised regularly, and must assure herself that the groom executes her orders faithfully; for some men, while professing to obey, have been known to stop at the nearest public house, and, after spending an hour or two in drinking beer and gossiping with acquaintances, to ride back complacently to the stable, leaving the horse to suffer from want of exercise. Other grooms have gone to the opposite extreme, and have ridden so hard and fast that the horse on his[51] return was completely tired out, so that when there was occasion to use him the same day it was an effort for him to maintain his usual light gait. Grooms who are always doctoring a horse, giving him nostrums that do no good but often much harm, are also to be avoided. In short, the owner of a horse must be prepared for tricks of all kinds on the part of these stable servants; although, in justice to them, it must be said that there are many who endeavor to perform all their duties faithfully, and can be relied on to treat with kindness any animals committed to their care.

Should the lady rider be obliged to get her horse from a livery stable, she should not rely entirely upon what his owner says of his gaits or gentleness, but should have him tried carefully by some friend or servant, before herself attempting to mount him. She should also be very careful to see, or have her escort see, that the saddle is properly placed upon the back of the horse and firmly girthed, so that there may be no danger of its turning.

Dryden.

A riding habit should be distinguished by its perfect simplicity. All attempts at display, such as feathers, ribbons, glaring gilt buttons, and sparkling jet, should be carefully avoided, and the dress should be noticeable only for the fineness of its material and the elegance of its fit.

One of the first requirements in a riding dress is that it should fit smoothly and easily. The sleeves should be rather loose, especially near the arm-holes, so that the arms may move freely; but should fit closely enough at the wrist to allow long gauntlet gloves to pass readily over them. It is essential that ample room should be allowed across the chest, as the shoulders are thrown somewhat back in riding, and the chest is, consequently, expanded. The neck of the dress should fit very easily, especially at the back part. Care must be taken not to make the waist too long, for, owing to a[53] lady's position in the saddle, the movements of her horse will soon make a long waist wrinkle and look inelegant. To secure ease, together with a perfect fit without crease or fold, will be somewhat difficult, but not impossible. Some tailors, particularly in New York, Philadelphia, London, and Paris, make a specialty of ladies' riding costumes, and can generally be relied on to supply comfortable and elegant habits.

The favorite and most appropriate style of riding jacket is the "postilion basque;" this should be cut short over the hips, and is then especially becoming to a plump person, as it diminishes the apparent width of the back below the waist. The front should have two small darts, and should extend about three inches below the waist; it should then slope gradually up to the hips,—where it must be shortest,—and then downward so as to form a short, square coat-flap at the back, below the waist. This flap must be made without gathers or plaits, and lined with silk, between which and the cloth some stiffening material should be inserted. The middle seam of the coat-flap should be left open as far as the waist, where about one inch of it must be lapped over from left to right; the short side-form on each side must be lapped a little toward the central unclosed[54] seam. The arm-holes should be cut rather high on the shoulders, so that the back may look less broad. If the lady lacks plumpness and roundness, her jacket must be made double-breasted, or else have padding placed across the bust, for a hollow chest mars all the beauty of the figure in the saddle, and causes the rider to look round-shouldered. The edge of the basque should be trimmed with cord-braid, and the front fastened with crocheted bullet buttons; similar buttons should be used to fasten the sleeves closely at the wrist, and two more should be placed on the back of the basque just at its waist line.

Great care must be taken to have the jacket well lined and its seams strongly sewed. The coat-flaps on the back of the basque, below the waist-line, should be held down by heavy metallic buttons, sewed underneath each flap at its lower part, and covered with the same material as that of the dress. Without these weights this part of the dress will be apt to be blown out of position by every passing breeze, and will bob up and down with every motion of the rider's body, presenting a most ridiculous appearance.

For winter riding an extra jacket may be worn over the riding basque. It should be made of some heavy, warm material, and fit half[55] tightly. If trimmed with good fur, this jacket makes a very handsome addition to the riding habit.

Poets have expatiated upon the grace and beauty of the long, flowing riding skirt, with its ample folds, but experience has taught that this long skirt, though, perhaps, very poetical, is practically not only inconvenient but positively dangerous. In the canter or gallop the horse is very apt to entangle his hind-foot in it and be thrown, when the rider may consider herself fortunate if she escapes with no worse accident than a torn skirt. Another objection to this poetical skirt is, that it gathers up the mud and dust of the road, and soon presents a most untidy appearance; while if the day be fresh and breezy its ample folds will stream out like a victorious banner; if made of some light material the breeze will swell it out like an inflated balloon; and if of heavy cloth its length will envelop the rider's feet, and make her look as if tied in a bag.