JOHN MARSHALL

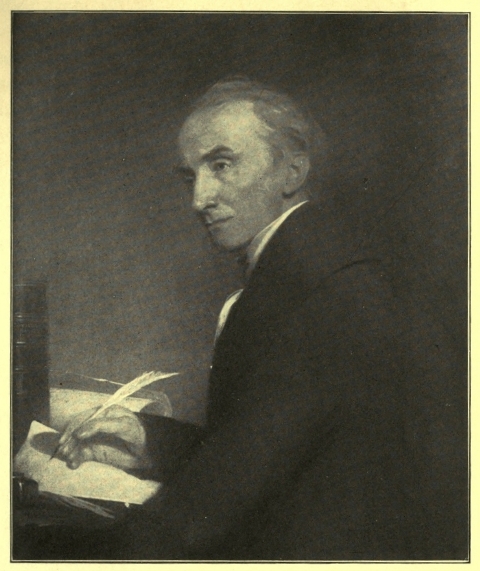

JOHN MARSHALLFrom the portrait by Henry Inman

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of John Marshall Volume 4 of 4, by Albert J. Beveridge This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Life of John Marshall Volume 4 of 4 Author: Albert J. Beveridge Release Date: August 19, 2012 [EBook #40533] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL *** Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| I. | THE PERIOD OF AMERICANIZATION | 1 |

| War and Marshall's career—Federalists become British partisans—Their hatred of France—Republicans are exactly the reverse—The deep and opposite prejudices of Marshall and Jefferson—Cause of their conflicting views—The people become Europeanized—They lose sight of American considerations—Critical need of a National American sentiment—Origin of the War of 1812—America suffers from both European belligerents—British depredations—Jefferson retaliates by ineffective peaceful methods—The Embargo laws passed—The Federalists enraged—Pickering makes sensational speech in the Senate—Marshall endorses it—Congress passes the "Force Act"—Jefferson practices an autocratic Nationalism—New England Federalists propose armed resistance and openly advocate secession—Marshall rebukes those who resist National authority—The case of Gideon Olmstead—Pennsylvania forcibly resists order of the United States Court—Marshall's opinion in U.S. vs. Judge Peters—Its historical significance—The British Minister repeats the tactics of Genêt—Federalists uphold him—Republicans make great gains in New England—Marshall's despondent letter—Henry Clay's heroic speeches—War is declared—Federalists violently oppose it: "The child of Prostitution"—Joseph Story indignant and alarmed—Marshall proposed as Presidential candidate of the peace party—Writes long letter advocating coalition of "all who wish peace"—Denounces Napoleon and the Decree of St. Cloud—He heads Virginia Commission to select trade route to the West—Makes extended and difficult journey through the mountains—Writes statesmanlike report—Peace party nominates Clinton—Marshall criticizes report of Secretary of State on the causes of the war—New England Federalists determine upon secession—The Administration pamphlet on expatriation—John Lowell brilliantly attacks it—Marshall warmly approves Lowell's essay—His judicial opinions on expatriation—The coming of peace—Results of the war—The new America is born. | ||

| II. | MARSHALL AND STORY | 59 |

| Marshall's greatest Constitutional decisions given during the decade after peace is declared—Majority of Supreme Court becomes Republican—Marshall's influence over the Associate Justices—His life in Richmond—His negligent attire—Personal anecdotes—Interest in farming—Simplicity of habits—Holds Circuit Court[Pg vi] at Raleigh—Marshall's devotion to his wife—His religious belief—His children—Life at Oak Hill—Generosity—Member of Quoit Club—His "lawyer dinners"—Delights in the reading of poetry and fiction—Familiarity and friendliness—Joseph Story first meets the Chief Justice—Is captivated by his personality—Marshall's dignity in presiding over Supreme Court—Quickness at repartee—Life in Washington—Marshall and Associate Justices live together in same boarding-house—His dislike of publicity—Honorary degrees conferred—Esteem of his contemporaries—His personality—Calmness of manner—Strength of intellect—His irresistible charm—Likeness to Abraham Lincoln—The strong and brilliant bar practicing before the Supreme Court—Legal oratory of the period—Length of arguments—Joseph Story—His character and attainments—Birth and family—A Republican—Devotion to Marshall—Their friendship mutually helpful—Jefferson fears Marshall's influence on Story—Edward Livingston sues Jefferson for one hundred thousand dollars—Circumstances leading to Batture litigation—Jefferson's desire to name District Judge in Virginia—Jefferson in letter attacks Marshall—He dictates appointment of John Tyler to succeed Cyrus Griffin—Death of Justice Cushing of the Supreme Court—Jefferson tries to name Cushing's successor—He objects to Story—Madison wishes to comply with Jefferson's request—His consequent difficulty in filling place—Appointment of Story—Jefferson prepares brief on Batture case—Public interest in case—Case is heard—Marshall's opinion reflects on Jefferson—Chancellor Kent's opinion—Jefferson and Livingston publish statements—Marshall ascribes Jefferson's animosity in subsequent years to the Batture litigation. | ||

| III. | INTERNATIONAL LAW | 117 |

| Marshall uniformly upholds acts of Congress even when he thinks them unwise and of doubtful constitutionality—The Embargo, Non-Importation, and Non-Intercourse laws—Marshall's slight knowledge of admiralty law—His dependence on Story—Marshall is supreme only in Constitutional law—High rank of his opinions on international law—Examples: The Schooner Exchange; U.S. vs. Palmer; The Divina Pastora; The Venus; The Nereid—Scenes in the court-room—Appearance of the Justices—William Pinkney the leader of the American bar—His learning and eloquence—His extravagant dress and arrogant manner—Story's admiration of him—Marshall's tribute—Character of the bar—Its members statesmen as well as lawyers—The attendance of women at arguments—Mrs. Smith's letter—American Insurance Co. et al. vs. David Canter—Story delivers the opinion in Martin vs. Hunter's Lessee—Reason for Marshall's declining to sit in that case—The Virginia Republican organization—The great political triumvirate, Roane, Ritchie, and Taylor—The Fairfax litigation—The Marshall purchase of a part of the Fairfax estate—Separate purchases of James M. Marshall—The Marshall and Virginia "compromise"—Virginia Court of Appeals decides in favor of Hunter[Pg vii]—National Supreme Court reverses State court—The latter's bold defiance of the National tribunal—Marshall refuses to sit in the case of the Granville heirs—History of the Granville litigation—The second appeal from the Virginia Court in the Fairfax-Martin-Hunter case—Story's great opinion in Fairfax's Devisee vs. Hunter's Lessee—His first Constitutional pronouncement—Its resemblance to Marshall's opinions—The Chief Justice disapproves one ground of Story's opinion—His letter to his brother—Anger of the Virginia judges at reversal of their judgment—The Virginia Republican organization prepares to attack Marshall. | ||

| IV. | FINANCIAL AND MORAL CHAOS | 168 |

| February and March, 1819, mark an epoch in American history—Marshall, at that time, delivers three of his greatest opinions—He surveys the state of the country—Beholds terrible conditions—The moral, economic, and social breakdown—Bad banking the immediate cause of the catastrophe—Sound and brilliant career of the first Bank of the United States—Causes of popular antagonism to it—Jealousy of the State banks—Jefferson's hostility to a central bank—John Adams's description of State banking methods—Opposition to rechartering the National institution—Congress refuses to recharter it—Abnormal increase of State banks—Their great and unjustifiable profits—Congress forced to charter second Bank of the United States—Immoral and uneconomic methods of State banks—Growth of "private banks"—Few restrictions placed on State and private banks and none regarded by them—Popular craze for more "money"—Character and habits of Western settlers—Local banks prey upon them—Marshall's personal experience—State banks control local press, bar, and courts—Ruthless foreclosures of mortgages and incredible sacrifices of property—Counterfeiting and crime—People unjustly blame Bank of the United States for their financial misfortunes—It is, at first, bad, and corruptly managed—Is subsequently well administered—Popular demand for bankruptcy laws—State "insolvency" statutes badly drawn and ruinously executed—Speculators use them to escape the payment of their liabilities while retaining their assets—Foreclosures and sheriff's sales increase—Demand for "stay laws" in Kentucky—Marshall's intimate personal knowledge of conditions in that State—States begin to tax National Bank out of existence—Marshall delivers one of his great trilogy of opinions of 1819 on contract, fraud, and banking—Effect of the decision of the Supreme Court in Sturges vs. Crowninshield. | ||

| V. | THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE | 220 |

| The Dartmouth College case affected by the state of the country—Marshall prepares his opinion while on his vacation—His views well known—His opinion in New Jersey vs. Wilson—Eleazar Wheelock's frontier Indian school—The voyage and mission of[Pg viii] Whitaker and Occom—Funds to aid the school raised in England and Scotland—The Earl of Dartmouth—Governor Wentworth grants a royal charter—Provisions of this document—Colonel John Wheelock becomes President of the College—The beginnings of strife—Obscure and confused origins of the Dartmouth controversy, including the slander of a woman's reputation, sectarian warfare, personal animosities, and partisan conflict—The College Trustees and President Wheelock become enemies—The hostile factions attack one another by means of pamphlets—The Trustees remove Wheelock from the Presidency—The Republican Legislature passes laws violative of the College Charter and establishing Dartmouth University—Violent political controversy—The College Trustees and officers refuse to yield—The famous suit of Trustees of Dartmouth College vs. Woodward is brought—The contract clause of the Constitution is but lightly considered by Webster, Mason, and Smith, attorneys for the College—Supreme Court of New Hampshire upholds the acts of the Legislature—Chief Justice Richardson delivers able opinion—The case appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States—Webster makes his first great argument before that tribunal—He rests his case largely on "natural right" and "fundamental principles," and relies but little on the contract clause—He has small hopes of success—The court cannot agree—Activity of College Trustees and officers during the summer and autumn of 1818—Chancellor James Kent advises Justices Johnson and Livingston of the Supreme Court—William Pinkney is retained by the opponents of the College—He plans to ask for a reargument and makes careful preparation—Webster is alarmed—The Supreme Court opens in February, 1819—Marshall ignores Pinkney and reads his opinion to which five Associate Justices assent—The joy of Webster and disgust of Pinkney—Hopkinson's comment—The effect of Marshall's opinion—The foundations of good faith—Comments upon Marshall's opinion—The persistent vitality of his doctrine as announced in the Dartmouth College case—Departures from it—Recent discussions of Marshall's theory. | ||

| VI. | VITALIZING THE CONSTITUTION | 282 |

| The third of Marshall's opinions delivered in 1819—The facts in the case of M'Culloch vs. Maryland—Pinkney makes the last but one of his great arguments—The final effort of Luther Martin—Marshall delivers his historic opinion—He announces a radical Nationalism—"The power to tax involves the power to destroy"—Marshall's opinion is violently attacked—Niles assails it in his Register—Declares it "more dangerous than foreign invasion"—Marshall's opinion more widely published than any previous judicial pronouncement—The Virginia Republican organization perceives its opportunity and strikes—Marshall tells Story of the coming assault—Roane attacks in the Richmond Enquirer—"The people must rouse from the lap of Delilah to meet the Philistines"—The letters of "Amphyction" and "Hampden"—The United States is "as much a league as was the former confedera[Pg ix]tion"—Marshall is acutely alarmed by Roane's attacks—He writes a dull and petulant newspaper defense of his brilliant opinion—Regrets his controversial effort and refuses to permit its republication—The Virginia Legislature passes resolutions denouncing his opinion and proposing a new tribunal to decide controversies between States and the Nation—The slave power joins the attack upon Marshall's doctrines—Ohio aligns herself with Virginia—Ohio's dramatic resistance to the Bank of the United States—Passes extravagantly drastic laws—Adopts resolutions denouncing Marshall's opinions and defying the National Government—Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Indiana, Illinois also demand a new court—John Taylor "of Caroline" writes his notable book, Construction Construed—Jefferson warmly approves it—Declares the National Judiciary to be a "subtle corps of sappers and miners constantly working underground to undermine the foundations of our confederated fabric." | ||

| VII. | THREATS OF WAR | 340 |

| Relation of slavery and Marshall's opinions—The South threatens war: "I behold a brother's sword crimsoned with a brother's blood"—Northern men quail—The source and purpose of Marshall's opinion in Cohens vs. Virginia—The facts in that case—A trivial police court controversy—The case probably "arranged"—William Pinkney and David B. Ogden appear for the Cohens—Senator James Barbour, for Virginia, threatens secession: "With them [State Governments], it is to determine how long their [National] government shall endure"—Marshall's opinion is an address to the American people—The grandeur of certain passages: "A Constitution is framed for ages to come and is designed to approach immortality"—The Constitution is vitalized by a "conservative power" within it—Independence of the Judiciary necessary to preservation of the Republic—Marshall directly replies to the assailants of Nationalism: "The States are members of one great empire"—Marshall originates the phraseology, "a government of, by, and for the people"—Publication of the opinion in Cohens vs. Virginia arouses intense excitement—Roane savagely attacks Marshall under the nom de guerre of "Algernon Sidney"—Marshall is deeply angered—He writes Story denouncing Roane's articles—Jefferson applauds and encourages attacks on Marshall—Marshall attributes to Jefferson the assaults upon him and the Supreme Court—The incident of John E. Hall and his Journal of American Jurisprudence—John Taylor again assails Marshall's opinions in his second book, Tyranny Unmasked—He connects monopoly, the protective tariff, internal improvements, "exclusive privileges," and emancipation with Marshall's Nationalist philosophy—Jefferson praises Taylor's essay and declares for armed resistance to National "usurpation": "The States must meet the invader foot to foot"—Senator Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky, in Congress, attacks Marshall and the Supreme Court—Offers an amend[Pg x]ment to the Constitution giving the Senate appellate jurisdiction from that tribunal—Roane asks the Virginia Legislature to demand an amendment to the National Constitution limiting the power of the Supreme Court—Senator Johnson makes bold and powerful speech in the Senate—Declares the Supreme Court to be a denial of the whole democratic theory—Webster sneers at Johnson's address—Kentucky and the Supreme Court—The "Occupying Claimant" laws—Decisions in Green vs. Biddle—The Kentucky Legislature passes condemnatory and defiant resolutions—Justice William Johnson infuriates the South by an opinion from the Circuit Bench—The connection of the foregoing events with the Ohio Bank case—The alignment of economic, political, and social forces—Marshall delivers his opinion in Osborn vs. The Bank of the United States—The historical significance of his declaration in that case. | ||

| VIII. | COMMERCE MADE FREE | 397 |

| Fulton's experiments on the Seine in Paris—French scientists reject his invention—The Livingston-Fulton partnership—Livingston's former experiments in New York—Secures monopoly grants from the Legislature—These expire—The Clermont makes the first successful steamboat voyage—Water transportation revolutionized—New York grants monopoly of steamboat navigation to Livingston and Fulton—They send Nicholas J. Roosevelt to inspect the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers—His romantic voyage to New Orleans—Louisiana grants exclusive steamboat privileges to Livingston and Fulton—New Jersey retaliates on New York—Connecticut forbids Livingston and Fulton boats to enter her waters—New York citizens defy the steamboat monopoly—Livingston and Fulton sue James Van Ingen—New York courts uphold the steamboat monopoly, and assert the right of the State to control navigation on its waters—The opinion of Chief Justice Kent—The controversy between Aaron Ogden and Thomas Gibbons—Ogden, operating under a license from Livingston and Fulton, sues Gibbons—State courts again sustain the monopoly acts—Gibbons appeals to the Supreme Court—Ogden retains William Pinkney—The case is dismissed, refiled, and continued—Pinkney dies—Argument not heard for three years—Several States pass monopoly laws—Prodigious development of steamboat navigation—The demand for internal improvements stimulated—The slave interests deny power of Congress to build roads and canals—The daring speech of John Randolph—Declares slavery imperiled—Threatens armed resistance—Remarkable alignment of opposing forces when Gibbons vs. Ogden is heard in Supreme Court—Webster makes the greatest of his legal arguments—Marshall's opinion one of his most masterful state papers—His former opinion on the Circuit Bench in the case of the Brig Wilson anticipates that in Gibbons vs. Ogden—The power of Congress over interstate and foreign commerce absolute[Pg xi] and exclusive—Marshall attacks the enemies of Nationalism—The immediate effect of Marshall's opinion on steamboat transportation, manufacturing, and mining—Later effect still more powerful—Railway development incalculably encouraged—Results to-day of Marshall's theory of commerce—Litigation in New York following the Supreme Court's decision—The whole-hearted Nationalism of Chief Justice Savage and Chancellor Sanford—Popularity of Marshall's opinion—The attack in Congress on the Supreme Court weakens—Martin Van Buren, while denouncing the "idolatry" for the Supreme Court, pays an exalted tribute to Marshall: "The ablest judge now sitting on any judicial bench in the world"—Senator John Rowan of Kentucky calls the new popular attitude toward the Supreme Court "a judicial superstition"—The case of Brown vs. Maryland—Marshall's opinion completes his Constitutional expositions of the commerce clause—Taney's remarkable acknowledgment. | ||

| IX. | THE SUPREME CONSERVATIVE | 461 |

| Marshall's dislike for the formal society of Washington—His charming letters to his wife—He carefully avoids partisan politics—Refrains from voting for twenty years—Is irritated by newspaper report of partisanship—Writes denial to the Richmond Whig—Clay writes Marshall—The Chief Justice explains incident to Story—Marshall's interest in politics—His letter to his brother—Permits himself to be elected to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-30—His disgust at his "weakness"—Writes Story amusing account—Issues before the convention deeply trouble him—He is frankly and unshakably conservative—The antiquated and undemocratic State Constitution of 1776 and the aristocratic system under it—Jefferson's brilliant indictment of both in a private letter—His alarm and anger when his letter is circulated—He tries to withdraw it—Marshall's interest in the well-being of the people—His prophetic letter to Charles F. Mercer—Marshall's only public ideal that of Nationalism—His views on slavery—Letters to Gurley and Pickering—His judicial opinions involving slavery and the slave trade: The Antelope; Boyce vs. Anderson—Extreme conservatism of Marshall's views on legislation and private property—Letter to Greenhow—Opinions in Ogden vs. Saunders and Bank vs. Dandridge—Marshall's work in the Virginia convention—Is against any reform—Writes Judiciary report—The aristocratic County Court system—Marshall defends it—Impressive tributes to Marshall from members of the convention—His animated and powerful speeches on the Judiciary—He answers Giles, Tazewell, and Cabell, and carries the convention by an astonishing majority—Is opposed to manhood suffrage and exclusive white basis of representation—He pleads for compromise on the latter subject and prevails—Reasons for his course in the convention—He probably prevents civil strife and bloodshed in Virginia—The convention adjourns—History of Craig vs. Missouri—Marshall's[Pg xii] stern opinion—The splendid eloquence of his closing passage—Three members of the Supreme Court file dissenting opinions—Marshall's melancholy comments on them—Congressional assaults on the Supreme Court renewed—They are astonishingly weak, and are overwhelmingly defeated, but the vote is ominous. | ||

| X. | THE FINAL CONFLICT | 518 |

| Sadness of Marshall's last years—His health fails—Contemplates resigning—His letters to Story—Goes to Philadelphia for surgical treatment—Remarkable resolutions by the bar of that city—Marshall's response—Is successfully operated upon by Dr. Physick—His cheerfulness—Letters to his wife—Mrs. Marshall dies—Marshall's grief—His tribute to her—He is depressed by the course of President Jackson—The warfare on the Bank of the United States—Congress recharters it—Jackson vetoes the Bank Bill and assails Marshall's opinions in the Bank cases—The people acclaim Jackson's veto—Marshall is disgusted—His letters to Story—He is alarmed at the growth of disunion sentiment—Causes of the recrudescence of Localism—Marshall's theory of Constitutional construction and its relation to slavery—The tariff—The South gives stern warnings—Dangerous agitation in South Carolina—Georgia asserts her "sovereignty" in the matter of the Cherokee Indians—The case of George Tassels—Georgia ignores the Supreme Court and rebukes Marshall—The Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia—The State again ignores the Supreme Court—Marshall delivers his opinion in that case—Worcester vs. Georgia—The State defies the Supreme Court—Marshall's opinion—Georgia flouts the Court and disregards its judgment—Jackson supports Georgia—Story's melancholy letter—The case of James Graves—Georgia once more defies the Supreme Court and threatens secession—South Carolina encouraged by Georgia's attitude—Nullification sentiment grows rapidly—The Hayne-Webster debate—Webster's great speech a condensation of Marshall's Nationalist opinions—Similarity of Webster's language to that of Marshall—The aged Madison repudiates Nullification—Marshall, pleased, writes Story: "Mr. Madison is himself again"—The Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 infuriate South Carolina—Scenes and opinion in that State—Marshall clearly states the situation—His letters to Story—South Carolina proclaims Nullification—Marshall's militant views—Jackson issues his Nullification Proclamation—It is based on Marshall's theory of the Constitution and is a triumph for Marshall—Story's letter—Hayne replies to Jackson—South Carolina flies to arms—Virginia intercedes—Both parties back down: South Carolina suspends Nullification and Congress passes Tariff of 1833—Marshall describes conditions in the South—His letters to Story—He almost despairs of the Republic—Public appreciation of his character—Story dedicates his Commentaries to Marshall—Marshall presides over the Supreme Court for the last time—His fatal illness—He dies at Philadelphia—The funeral at Richmond[Pg xiii]—Widespread expressions of sorrow—Only one of condemnation—The long-continued mourning in Virginia—Marshall's old club resolves never to fill his place or increase its membership—Story's "inscription for a cenotaph" and the words Marshall wrote for his tomb. | ||

| WORKS CITED IN THIS VOLUME | 595 | |

| INDEX | 613 | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | Colored Frontispiece |

| From the portrait painted in 1832 by Henry Inman, in the possession of The Law Association of Philadelphia. A copy was presented to the Connecticut State Library by Senator Frank B. Brandegee and was chosen by the Secretary of the Treasury out of all existing portraits to be engraved on steel for use as a vignette on certain government bonds and treasury notes. | |

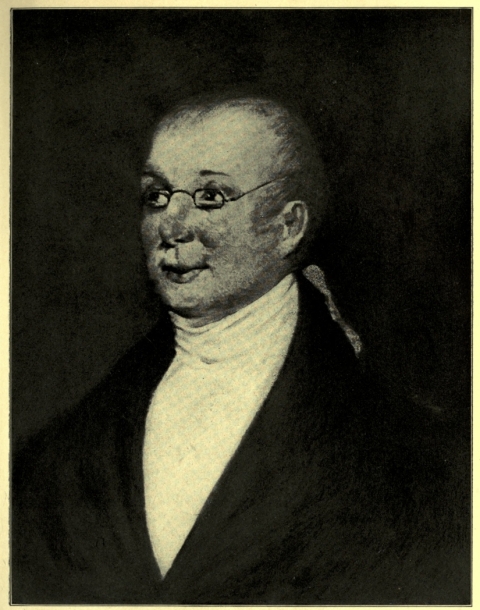

| TIMOTHY PICKERING | 50 |

| From a painting by Stuart, owned by Mr. Robert M. Pratt, Boston. | |

| JOSEPH STORY | 96 |

| From a crayon drawing by his son, William Wetmore Story, in the possession of the family. | |

| WILLIAM PINKNEY | 132 |

| From the original painting by Charles Wilson Peale, in the possession of Pinkney's grandson, William Pinkney Whyte, Esq., Baltimore, Maryland. | |

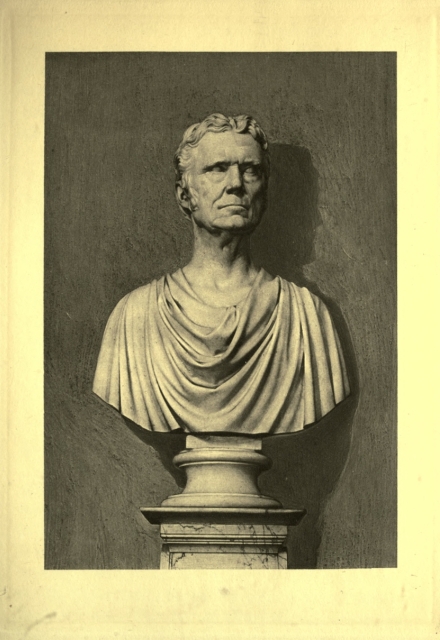

| JOHN MARSHALL | 210 |

| From the bust in the Court Room of the United States Supreme Court. | |

| JOSEPH HOPKINSON | 254 |

| From a portrait owned by Dartmouth College. | |

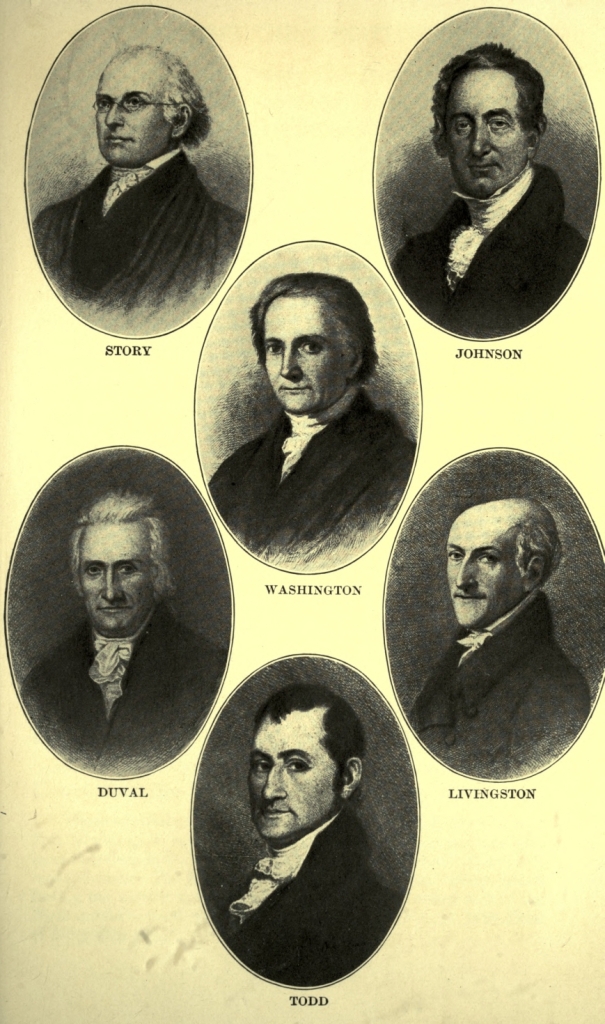

| ASSOCIATE JUSTICES SITTING WITH MARSHALL IN THE CASE OF M'CULLOCH VERSUS MARYLAND: BUSHROD WASHINGTON, WILLIAM JOHNSON, BROCKHOLST LIVINGSTON, THOMAS TODD, JOSEPH STORY, GABRIEL DUVAL | 282 |

| From etchings by Max and Albert Rosenthal in Hampton L. Carson's history of The Supreme Court of the United States, reproduced through the courtesy of the Lawyers' Coöperative Publishing Company, Rochester, New York. The etchings were made from originals as follows: Washington, from a painting by Chester Harding in the possession of the family; Johnson, from a painting by Jarvis in the possession of the New York Historical Society; Livingston, from a painting in the possession of the family; Todd, from a painting in the possession of the family; Story, from a drawing by William Wetmore Story in the possession of the family; Duval, from a painting in the Capitol at Washington. Mr. Justice Todd is included as a member of the Court at that time, although absent because of illness. | |

| SPENCER ROANE | 314[Pg xvi] |

| From a painting in the Court of Appeals at Richmond, Virginia. | |

| JOHN TAYLOR OF CAROLINE | 336 |

| From a painting in the possession of the Virginia State Library, Richmond. | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | 412 |

| From a portrait painted by J. B. Martin and presented to the University of Virginia in 1901 by John L. Williams, Esq., of Richmond, Virginia. | |

| SILHOUETTE OF JOHN MARSHALL | 462 |

| From the original found in the desk of Mr. Justice Story. | |

| LEEDS MANOR | 528 |

| From a photograph. This was the principal house in the Fairfax Purchase and was the home of Marshall's son James Keith Marshall. The wing on the left was built especially for the use of Chief Justice Marshall, who expected to spend his declining years there. Many of his books and papers were kept in this house. | |

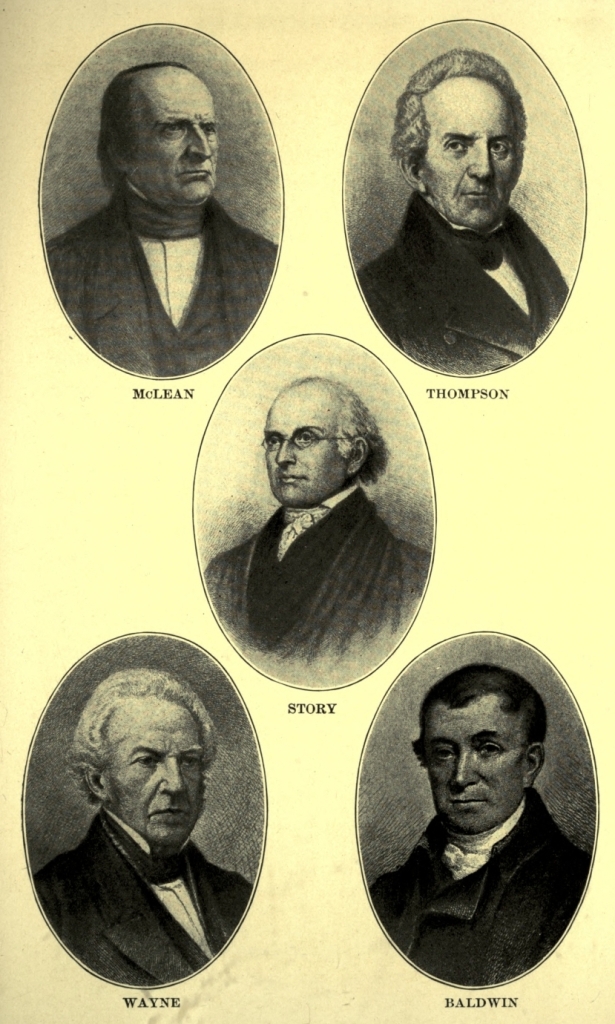

| ASSOCIATE JUSTICES AT THE LAST SESSION OF THE SUPREME COURT OVER WHICH JOHN MARSHALL PRESIDED: JOSEPH STORY, SMITH THOMPSON, JOHN McLEAN, HENRY BALDWIN, JAMES M. WAYNE | 584 |

| From etchings by Max and Albert Rosenthal in Hampton L. Carson's history of The Supreme Court of the United States, reproduced by the courtesy of the Lawyers' Coöperative Publishing Company, Rochester, New York. The etchings were made from originals as follows: Story, from a drawing by William Wetmore Story in the possession of the family; Smith Thompson from a painting by Dumont in the possession of Smith Thompson, Esq., Hudson, New York; McLean, from a painting by Ives, in the possession of Mr. Justice Brown; Baldwin, from a painting by Lambdin in the possession of the family; Wayne, from a photograph by Brady in the possession of Mr. Justice Field. | |

| THE GRAVE OF JOHN MARSHALL | 592 |

| From a photograph of the graves of Marshall and his Wife in the Shockoe Hill Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia. |

All references here are to the List of Authorities at the end of this volume

Adams: U.S. See Adams, Henry. History of the United States.

Ambler: Ritchie. See Ambler, Charles Henry. Thomas Ritchie: A Study in Virginia Politics.

Ames: Ames. See Ames, Fisher. Works.

Anderson. See Anderson, Dice Robins. William Branch Giles.

Babcock. See Babcock, Kendric Charles. Rise of American Nationality, 1811-1819.

Bayard Papers: Donnan. See Bayard, James Asheton. Papers from 1796 to 1815. Edited by Elizabeth Donnan.

Branch Historical Papers. See John P. Branch Historical Papers.

Catterall. See Catterall, Ralph Charles Henry. Second Bank of the United States.

Channing: Jeff. System. See Channing, Edward. Jeffersonian System, 1801-1811.

Channing: U.S. See Channing, Edward. History of the United States.

Curtis. See Curtis, George Ticknor. Life of Daniel Webster.

Dewey. See Dewey, Davis Rich. Financial History of the United States.

Dillon. See Dillon, John Forrest. John Marshall: Life, Character, and Judicial Services.

E. W. T.: Thwaites. See Thwaites, Reuben Gold. Early Western Travels.

Farrar. See Farrar, Timothy. Report of the Case of the Trustees of Dartmouth College against William H. Woodward.

Hildreth. See Hildreth, Richard. History of the United States of America.

Hunt: Livingston. See Hunt, Charles Havens. Life of Edward Livingston.

Kennedy. See Kennedy, John Pendleton. Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt.

King. See King, Rufus. Life and Correspondence. Edited by Charles R. King.

Lodge: Cabot. See Lodge, Henry Cabot. Life and Letters of George Cabot.

Lord. See Lord, John King. A History of Dartmouth College, 1815-1909.

McMaster. See McMaster, John Bach. A History of the People of the United States.

Memoirs, J. Q. A.: Adams. See Adams, John Quincy. Memoirs. Edited by Charles Francis Adams.

Morison: Otis. See Morison, Samuel Eliot. Life and Letters of Harrison Gray Otis.

Morris. See Morris, Gouverneur. Diary and Letters. Edited by Anne Cary Morris.

N.E. Federalism: Adams. See Adams, Henry. Documents relating to New-England Federalism, 1800-1815.

Parton: Jackson. See Parton, James. Life of Andrew Jackson.

Plumer. See Plumer, William, Jr. Life of William Plumer.

Priv. Corres.: Webster. See Webster, Daniel. Private Correspondence. Edited by Fletcher Webster.

Quincy: Quincy. See Quincy, Edmund. Life of Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts.

Randall. See Randall, Henry Stephens. Life of Thomas Jefferson.

Records Fed. Conv.: Farrand. See Records of the Federal Convention of 1787. Edited by Max Farrand.

Richardson. See Richardson, James Daniel. A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 1789-1897.

Shirley. See Shirley, John M. The Dartmouth College Causes and the Supreme Court of the United States.

Story. See Story, Joseph. Life and Letters. Edited by William Wetmore Story.

Sumner: Hist. Am. Currency. See Sumner, William Graham. A History of American Currency.

Sumner: Jackson. See Sumner, William Graham. Andrew Jackson. As a Public Man.

Tyler: Tyler. See Tyler, Lyon Gardiner. Letters and Times of the Tylers.

Works: Ford. See Jefferson, Thomas. Works. Edited by Paul Leicester Ford.

Writings: Adams. See Gallatin, Albert. Writings. Edited by Henry Adams.

Writings: Hunt. See Madison, James. Writings. Edited by Gaillard Hunt.

Great Britain is fighting our battles and the battles of mankind, and France is combating for the power to enslave and plunder us and all the world. (Fisher Ames.)

Though every one of these Bugbears is an empty Phantom, yet the People seem to believe every article of this bombastical Creed. Who shall touch these blind eyes. (John Adams.)

The object of England, long obvious, is to claim the ocean as her domain. (Jefferson.)

I am for resistance by the sword. (Henry Clay.)

Into the life of John Marshall war was strangely woven. His birth, his young manhood, his public services before he became Chief Justice, were coincident with, and affected by, war. It seemed to be the decree of Fate that his career should march side by side with armed conflict, and that the final phase of that career should open with a war—a war, too, which brought forth a National consciousness among the people and demonstrated a National strength hitherto unsuspected in their fundamental law.

Yet, while American Nationalism was Marshall's one and only great conception, and the fostering of it the purpose of his life, he was wholly out of sympathy with the National movement that led to our second conflict with Great Britain, and against the continuance of it. He heartily shared the opinion of the Federalist leaders that the War of 1812 was unnecessary, unwise, and unrighteous.

By the time France and England had renewed[Pg 2] hostilities in 1803, the sympathies of these men had become wholly British. The excesses of the French Revolution had started them on this course of feeling and thinking. Their detestation of Jefferson, their abhorrence of Republican doctrines, their resentment of Virginia domination, all hastened their progress toward partisanship for Great Britain. They had, indeed, reverted to the colonial state of mind, and the old phrases, "the mother country," "the protection of the British fleet,"[1] were forever on their lips.

These Federalists passionately hated France; to them France was only the monstrous child of the terrible Revolution which, in the name of human rights, had attacked successfully every idea dear to their hearts—upset all order, endangered all property, overturned all respectability. They were sure that Napoleon intended to subjugate the world; and that Great Britain was our only bulwark against the aggressions of the Conqueror—that "varlet" whose "patron-saint [is] Beelzebub," as Gouverneur Morris referred to Napoleon.[2]

So, too, thought John Marshall. No man, except his kinsman Thomas Jefferson, cherished a prejudice more fondly than he. Perhaps no better example of first impressions strongly made and tenaciously retained can be found than in these two men. Jefferson was as hostile as Marshall was friendly to Great Britain; and they held exactly opposite sentiments toward France. Jefferson's strongest title[Pg 3] to immortality was the Declaration of Independence; nearly all of his foreign embroilments had been with British statesmen. In British conservatism he had found the most resolute opposition to those democratic reforms he so passionately championed, and which he rightly considered the manifestations of a world movement.[3]

And Jefferson adored France, in whose entrancing capital he had spent his happiest years. There his radical tendencies had found encouragement. He looked upon the French Revolution as the breaking of humanity's chains, politically, intellectually, spiritually.[4] He believed that the war of the allied governments of Europe against the new-born French Republic was a monarchical combination to extinguish the flame of liberty which France had lighted.

Marshall, on the other hand, never could forget his experience with the French. And his revelation of what he had endured while in Paris had brought him his first National fame.[5] Then, too, his idol, Washington, had shared his own views—indeed, Marshall had been instrumental in the formation of Washington's settled opinions. Marshall had championed the Jay Treaty, and, in doing so, had necessarily taken the side of Great Britain as opposed to France.[6] His business interests[7] powerfully inclined him in the same direction. His personal friends were the ageing Federalists.[Pg 4]

He had also become obsessed with an almost religious devotion to the rights of property, to steady government by "the rich, the wise and good,"[8] to "respectable" society. These convictions Marshall found most firmly retained and best defended in the commercial centers of the East and North. The stoutest champions of Marshall's beloved stability of institutions and customs were the old Federalist leaders, particularly of New England and New York. They had been his comrades and associates in bygone days and continued to be his intimates.

In short, John Marshall had become the personification of the reaction against popular government that followed the French Revolution. With him and men of his cast of mind, Great Britain had come to represent all that was enduring and good, and France all that was eruptive and evil. Such was his outlook on social and political life when, after these traditional European foes were again at war, their spoliations of American commerce, violations of American rights, and insults to American honor once more became flagrant; and such continued to be his opinion and feeling after these aggressions had become intolerable.

Since the adoption of the Constitution, nearly all Americans, except the younger generation, had become re-Europeanized in thought and feeling. Their partisanship of France and Great Britain relegated America to a subordinate place in their minds and hearts. Just as the anti-Federalists and[Pg 5] their successors, the Republicans, had been more concerned in the triumph of revolutionary France over "monarchical" England than in the maintenance of American interests, rights, and honor, so now the Federalists were equally violent in their championship of Great Britain in her conflict with the France of Napoleon. Precisely as the French partisans of a few years earlier had asserted that the cause of France was that of America also,[9] the Federalists now insisted that the success of Great Britain meant the salvation of the United States.

"Great Britain is fighting our battles and the battles of mankind, and France is combating for the power to enslave and plunder us and all the world,"[10] wrote that faithful interpreter of extreme New England Federalism, Fisher Ames, just after the European conflict was renewed. Such opinions were not confined to the North and East. In South Carolina, John Rutledge was under the same spell. Writing to "the head Quarters of good Principles," Boston, he avowed that "I have long considered England as but the advanced guard of our Country.... If they fall we do."[11] Scores of quotations from prominent Federalists expressive of the same views might be adduced.[12] Even the assault on[Pg 6] the Chesapeake did not change or even soften them.[13] On the other hand, the advocates of France as ardently upheld her cause, as fiercely assailed Great Britain.[14]

Never did Americans more seriously need emancipation from foreign influence than in the early decades of the Republic—never was it more vital to their well-being that the people should develop an American spirit, than at the height of the Napoleonic Wars.

Upon the renewal of the European conflict, Great Britain announced wholesale blockades of French ports,[15] ordered the seizure of neutral ships wherever found carrying on trade with an enemy of England;[16] and forbade them to enter the harbors of immense stretches of European coasts.[17] In reply, Napoleon declared the British Islands to be under blockade, and ordered the capture in any waters whatsoever of all ships that had entered British harbors.[18] Great Britain responded with the Orders in Council of 1807 which, in effect, prohib[Pg 7]ited the oceans to neutral vessels except such as traded directly with England or her colonies; and even this commerce was made subject to a special tax to be paid into the British treasury.[19] Napoleon's swift answer was the Milan Decree,[20] which, among other things, directed all ships submitting to the British Orders in Council to be seized and confiscated in the ports of France or her allies, or captured on the high seas.

All these "decrees," "orders," and "instructions" were, of course, in flagrant violation of international law, and were more injurious to America than to all other neutrals put together. Both belligerents bore down upon American commerce and seized American ships with equal lawlessness.[21] But, since Great Britain commanded the oceans,[22] the United States suffered far more severely from the depredations of that Power.[23] Under pressure of conflict, Great[Pg 8] Britain increased her impressment[24] of American sailors. In effect, our ports were blockaded.[25]

Jefferson's lifelong prejudice against Great Britain[26] would permit him to see in all this nothing but a sordid and brutal imperialism. Not for a moment did he understand or consider the British point of view. England's "intentions have been to claim the ocean as her conquest, & prohibit any vessel from navigating it but on ... tribute," he wrote.[27] Nevertheless, he met Great Britain's orders and instructions with hesitant recommendations that the country be put in a state of defense; only feeble preliminary steps were taken to that end.[Pg 9]

The President's principal reliance was on the device of taking from Great Britain her American markets. So came the Non-Importation Act of April, 1806, prohibiting the admission of those products that constituted the bulk of Great Britain's immensely profitable trade with the United States.[28] This economic measure was of no avail—it amounted to little more than an encouragement of successful smuggling.

When the Leopard attacked the Chesapeake,[29] Jefferson issued his proclamation reciting the "enormity" as he called it, and ordering all British armed vessels from American waters.[30] The spirit of America was at last aroused.[31] Demands for war rang throughout the land.[32] But they did not come from the lips of Federalists, who, with a few exceptions, protested loudly against any kind of retaliation.

John Lowell, unequaled in talent and learning among the brilliant group of Federalists in Boston, wrote a pamphlet in defense of British conduct.[33][Pg 10] It was an uncommonly able performance, bright, informed, witty, well reasoned. "Despising the threats of prosecution for treason," he would, said Lowell, use his right of free speech to save the country from an unjustifiable war. What did the Chesapeake incident, what did impressment of Americans, what did anything and everything amount to, compared to the one tremendous fact of Great Britain's struggle with France? All thoughtful men knew that Great Britain alone stood between us and that slavery which would be our portion if France should prevail.[34]

Lowell's sparkling essay well set forth the intense conviction of nearly all leading Federalists. Giles was not without justification when he branded them as "the mere Anglican party."[35] The London press had approved the attack on the Chesapeake, applauded Admiral Berkeley, and even insisted upon war against the United States.[36] American Federalists were not far behind the Times and the Morning Post.

Jefferson, on the contrary, vividly stated the thought of the ordinary American: "The English being equally tyrannical at sea as he [Bonaparte] is on land, & that tyranny bearing on us in every point of either honor or interest, I say, 'down with Eng[Pg 11]land' and as for what Buonaparte is then to do to us, let us trust to the chapter of accidents, I cannot, with the Anglomen, prefer a certain present evil to a future hypothetical one."[37]

But the President did not propose to execute his policy of "down with England" by any such horrid method as bloodshed. He would stop Americans from trading with the world—that would prevent the capture of our ships and the impressment of our seamen.[38] Thus it was that the Embargo Act of December, 1807, and the supplementary acts of January, March, and April, 1808, were passed.[39] All exportation by sea or land was rigidly forbidden under heavy penalties. Even coasting vessels were not allowed to continue purely American trade unless heavy bond was given that landing would be made exclusively at American ports. Flour could be shipped by sea only in case the President thought it necessary to keep from hunger the population of any given port.[40]

Here was an exercise of National power such as John Marshall had never dreamed of. The effect was disastrous. American ocean-carrying trade was ruined; British ships were given the monopoly of the seas.[41] And England was not "downed," as Jefferson expected. In fact neither France nor Great Britain relaxed its practices in the least.[42]

The commercial interests demanded the repeal of the Embargo laws,[43] so ruinous to American shipping, so destructive to American trade, so futile in redressing the wrongs we had suffered. Massachusetts was enraged. A great proportion of the tonnage of the whole country was owned in that State and the Embargo had paralyzed her chief industry. Here was a fresh source of grievance against the Administration and a just one. Jefferson had, at last, given the Federalists a real issue. Had they[Pg 13] availed themselves of it on economic and purely American grounds, they might have begun the rehabilitation of their weakened party throughout the country. But theirs were the vices of pride and of age—they could neither learn nor forget; could not estimate situations as they really were, but only as prejudice made them appear to be.

As soon as Congress convened in November, 1808, New England opened the attack on Jefferson's retaliatory measures. Senator James Hillhouse of Connecticut offered a resolution for the repeal of the obnoxious statutes. "Great Britain was not to be threatened into compliance by a rod of coercion," he said.[44] Pickering made a speech which might well have been delivered in Parliament.[45] British maritime practices were right, the Embargo wrong, and principally injurious to America.[46] The Orders in Council had been issued only after Great Britain "had witnessed ... these atrocities" committed by Napoleon and his plundering armies, "and seen the[Pg 14] deadly weapon aimed at her vitals." Yet Jefferson had acted very much as if the United States were a vassal of France.[47]

Again Pickering addressed the Senate, flatly charging that all Embargo measures were "in exact conformity with the views and wishes of the French Emperor, ... the most ruthless tyrant that has scourged the European world, since the Roman Empire fell!" Suppose the British Navy were destroyed and France triumphant over Great Britain—to the other titles of Bonaparte would then "be added that of Emperor of the Two Americas"; for what legions of soldiers "could he not send to the United States in the thousands of British ships, were they also at his command?"[48]

As soon as they were printed, Pickering sent copies of these and speeches of other Federalists to his close associate, the Chief Justice of the United States. Marshall's prompt answer shows how far he had gone in company with New England Federalist opinion.

"I thank you very sincerely," he wrote "for the excellent speeches lately delivered in the senate.... If sound argument & correct reasoning could save our country it would be saved. Nothing can be more completely demonstrated than the inefficacy of the embargo, yet that demonstration seems to be of no avail. I fear most seriously that the same spirit which so tenaciously maintains this measure will impel us to a war with the only power which protects any part of the civilized world from the[Pg 15] despotism of that tyrant with whom we shall then be ravaged."[49]

Such was the change that nine years had wrought in the views of John Marshall. When Secretary of State he had arraigned Great Britain for her conduct toward neutrals, denounced the impressment of American sailors, and branded her admiralty courts as habitually unjust if not corrupt.[50] But his hatred of France had metamorphosed the man.

Before Marshall had written this letter, the Legislature of Massachusetts formally declared that the continuance of the Embargo would "endanger ... the union of these States."[51] Talk of secession was steadily growing in New England.[52] The National Government feared open rebellion.[53] Only one eminent Federalist dissented from these views of the party leaders which Marshall also held as fervently as they. That man was the one to whom he owed his place on the Supreme Bench. From his retirement in Quincy, John Adams watched the growing excitement with amused contempt.

"Our Gazettes and Pamphlets," he wrote, "tell us that Bonaparte ... will conquer England, and command all the British Navy, and send I know not how many hundred thousand soldiers here and con[Pg 16]quer from New Orleans to Passamaquoddy. Though every one of these Bugbears is an empty Phantom, yet the People seem to believe every article of this bombastical Creed and tremble and shudder in Consequence. Who shall touch these blind eyes?"[54]

On January 9, 1809, Jefferson signed the "Force Act," which the Republican Congress had defiantly passed, and again Marshall beheld such an assertion of National power as the boldest Federalist of Alien and Sedition times never had suggested. Collectors of customs were authorized to seize any vessel or wagon if they suspected the owner of an intention to evade the Embargo laws; ships could be laden only in the presence of National officials, and sailing delayed or prohibited arbitrarily. Rich rewards were provided for informers who should put the Government on the track of any violation of the multitude of restrictions of these statutes or of the Treasury regulations interpretative of them. The militia, the army, the navy were to be employed to enforce obedience.[55]

Along the New England coasts popular wrath swept like a forest fire. Violent resolutions were passed.[56] The Collector of Boston, Benjamin Lincoln, refused to obey the law and resigned.[57] The Legislature of[Pg 17] Massachusetts passed a bill denouncing the "Force Act" as unconstitutional, and declaring any officer entering a house in execution of it to be guilty of a high misdemeanor, punishable by fine and imprisonment.[58] The Governor of Connecticut declined the request of the Secretary of War to afford military aid and addressed the Legislature in a speech bristling with sedition.[59] The Embargo must go, said the Federalists, or New England would appeal to arms. Riots broke out in many towns. Withdrawal from the Union was openly advocated.[60] Nor was this sentiment confined to that section. "If the question were barely stirred in New England, some States would drop off the Union like fruit, rotten ripe," wrote A. C. Hanson of Baltimore.[61] Humphrey Marshall of Kentucky declared that he looked to "Boston ... the Cradle, and Salem, the nourse, of American Liberty," as "the source of reformation, or should that be unattainable, of disunion."[62]

Warmly as he sympathized with Federalist opinion of the absurd Republican retaliatory measures, and earnestly as he shared Federalist partisanship for Great Britain, John Marshall deplored all talk of[Pg 18] secession and sternly rebuked resistance to National authority, as is shown in his opinion in Fletcher vs. Peck,[63] wherein he asserted the sovereignty of the Nation over a State.

Another occasion, however, gave Marshall a better opportunity to state his views more directly, and to charge them with the whole force of the concurrence of all his associates on the Supreme Bench. This occasion was the resistance of the Legislature and Governor of Pennsylvania to a decree of Richard Peters, Judge of the United States Court for that district, rendered in the notable and dramatic case of Gideon Olmstead. During the Revolution, Olmstead and three other American sailors captured the British sloop Active and sailed for Egg Harbor, New Jersey. Upon nearing their destination, they were overhauled by an armed vessel belonging to the State of Pennsylvania and by an American privateer. The Active was taken to Philadelphia and claimed as a prize of war. The court awarded Olmstead and his comrades only one fourth of the proceeds of the sale of the vessel, the other three fourths going to the State of Pennsylvania, to the officers and crew of the State ship, and to those of the privateer. The Continental Prize Court reversed the decision and ordered the whole amount received for sloop and cargo to be paid to Olmstead and his associates.

This the State court refused to do, and a litigation began which lasted for thirty years. The funds were invested in United States loan certificates, and these were delivered by the State Judge to the State Treas[Pg 19]urer, David Rittenhouse, upon a bond saving the Judge harmless in case he, thereafter, should be compelled to pay the amount in controversy to Olmstead. Rittenhouse kept the securities in his personal possession, and after his death they were found among his effects with a note in his handwriting that they would become the property of Pennsylvania when the State released him from his bond to the Judge.

In 1803, Olmstead secured from Judge Peters an order to the daughters of Rittenhouse who, as his executrixes, had possession of the securities, to deliver them to Olmstead and his associates. This proceeding of the National court was promptly met by an act of the State Legislature which declared that the National court had "usurped" jurisdiction, and directed the Governor to "protect the just rights of the state ... from any process whatever issued out of any federal court."[64]

Peters, a good lawyer and an upright judge, but a timorous man, was cowed by this sharp defiance and did nothing. The executrixes held on to the securities. At last, on March 5, 1808, Olmstead applied to the Supreme Court of the United States for a rule directed to Judge Peters to show cause why a mandamus should not issue compelling him to execute his decree. Peters made return that the act of the State Legislature had caused him "from prudential ... motives ... to avoid embroiling the government of the United States and that of Pennsylvania."[65]

Thus the matter came before Marshall. On February 20, 1809, just when threats of resistance to the[Pg 20] "Force Act" were sounding loudest, when riots were in progress along the New England seaboard, and a storm of debate over the Embargo and Non-Intercourse laws was raging in Congress, the Chief Justice delivered his opinion in the case of the United States vs. Peters.[66] The court had, began Marshall, considered the return of Judge Peters "with great attention, and with serious concern." The act of the Pennsylvania Legislature challenged the very life of the National Government, for, "if the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery, and the nation is deprived of the means of enforcing its laws by the instrumentality of its own tribunals."

These clear, strong words were addressed to Massachusetts and Connecticut no less than to Pennsylvania. They were meant for Marshall's Federalist comrades and friends—for Pickering, and Gore, and Morris, and Otis—as much as for the State officials in Lancaster. His opinion was not confined to the case before him; it was meant for the whole country and especially for those localities where National laws were being denounced and violated, and National authority defied and flouted. Considering the depth and fervor of Marshall's feelings on the whole policy of the Republican régime, his opinion in United States vs. Judge Peters was signally brave and noble.[Pg 21]

Forcible resistance by a State to National authority! "So fatal a result must be deprecated by all; and the people of Pennsylvania, not less than the citizens of every other state, must feel a deep interest in resisting principles so destructive of the Union, and in averting consequences so fatal to themselves." Marshall then states the facts of the controversy and concludes that "the state of Pennsylvania can possess no constitutional right" to resist the authority of the National courts. His decision, he says, "is not made without extreme regret at the necessity which has induced the application." But, because "it is a solemn duty" to do so, the "mandamus must be awarded."[67]

Marshall's opinion deeply angered the Legislature and officials of Pennsylvania.[68] When Judge Peters, in obedience to the order of the Supreme Court, directed the United States Marshal to enforce the decree in Olmstead's favor, that official found the militia under command of General Bright drawn up around the house of the two executrixes. The dispute was at last composed, largely because President Madison rebuked Pennsylvania and upheld the National courts.[69][Pg 22]

A week after the delivery of Marshall's opinion, the most oppressive provisions of the Embargo Acts were repealed and a curious non-intercourse law enacted.[70] One section directed the suspension of all commercial restrictions against France or Great Britain in case either belligerent revoked its orders or decrees against the United States; and this the President was to announce by proclamation. The new British Minister, David M. Erskine, now tendered apology and reparation for the attack on the Chesapeake and positively assured the Administration that, if the United States would renew intercourse with Great Britain, the British Orders in Council would be withdrawn on June 10, 1809. Immediately President Madison issued his proclamation stating this fact and announcing that after that happy June day, Americans might renew their long and ruinously suspended trade with all the world not subject to French control.[71]

The Federalists were jubilant.[72] But their joy was quickly turned to wrath—against the Administration. Great Britain repudiated the agreement of her Minister, recalled him, and sent another charged with rigid and impossible instructions.[73] In deep humiliation, Madison issued a second proclamation reciting the facts and restoring to full operation against Great Britain all the restrictive commercial and maritime laws remaining on the statute[Pg 23] books.[74] At a banquet in Richmond, Jefferson proposed a toast: "The freedom of the seas!"[75]

Upon the arrival of Francis James Jackson, Erskine's successor as British Minister, the scenes of the Genêt drama[76] were repeated. Jackson was arrogant and overbearing, and his instructions were as harsh as his disposition.[77] Soon the Administration was forced to refuse further conference with him. Jackson then issued an appeal to the American people in the form of a circular to British Consuls in America, accusing the American Government of trickery, concealment of facts, and all but downright falsehood.[78] A letter of Canning to the American Minister at London[79] found its way into the Federalist newspapers, "doubtless by the connivance of the British Minister," says Joseph Story. This letter was, Story thought, an "infamous" appeal to the American people to repudiate their own Government, "the old game of Genêt played over again."[80][Pg 24]

Furious altercations arose all over the country. The Federalists defended Jackson. When the elections came on, the Republicans made tremendous gains in New England as well as in other States,[81] a circumstance that depressed Marshall profoundly. In December an acrimonious debate arose in Congress over a resolution denouncing Jackson's circular letter as a "direct and aggravated insult and affront to the American people and their Government."[82] Every Federalist opposed the resolution. Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts declared that every word of it was a "falsehood," and that the adoption of it would call forth "severe retribution, perhaps in war" from Great Britain.[83]

Disheartened, disgusted, wrathful, Marshall wrote Quincy: "The Federalists of the South participate with their brethren of the North in the gloomy anticipations which your late elections must inspire. The proceedings of the House of Representatives already demonstrate the influence of those elections on the affairs of the Union. I had supposed that the late letter to Mr. Armstrong,[84] and the late seizure [by[Pg 25] the French] of an American vessel, simply because she was an American, added to previous burnings, ransoms, and confiscations, would have exhausted to the dregs our cup of servility and degradation; but these measures appear to make no impression on those to whom the United States confide their destinies. To what point are we verging?"[85]

Nor did the Chief Justice keep quiet in Richmond. "We have lost our resentment for the severest injuries a nation ever suffered, because of their being so often repeated. Nay, Judge Marshall and Mr. Pickering & Co. found out Great Britain had given us no cause of complaint,"[86] writes John Tyler. And ever nearer drew the inevitable conflict.

Jackson was unabashed by the condemnation of Congress, and not without reason. Wherever he went, more invitations to dine than he could accept poured in upon him from the "best families"; banquets were given in his honor; the Senate of Massachusetts adopted resolutions condemning the Administration and upholding Jackson, who declared that the State had "done more towards justifying me to the world than it was possible ... that I or any other person could do."[87] The talk of secession grew.[88] At[Pg 26] a public banquet given Jackson, Pickering proposed the toast: "The world's last hope—Britain's fast-anchored isle!" It was greeted with a storm of cheers. Pickering's words sped over the country and became the political war cry of Federalism.[89] Marshall, who in Richmond was following "with anxiety" all political news, undoubtedly read it, and his letters show that Pickering's words stated the opinion of the Chief Justice.[90]

Upon the assurance of the French Foreign Minister that the Berlin and Milan Decrees would be revoked after November 1, 1810, President Madison, on November 2, announced what he believed to be Napoleon's settled determination, and recommended the resumption of commercial relations with France and the suspension of all intercourse with Great Britain unless that Power also withdrew its injurious and offensive Orders in Council.[91]

When at Washington, Marshall was frequently in[Pg 27] Pickering's company. Before the Chief Justice left for Richmond, the Massachusetts Senator had lent him pamphlets containing part of John Adams's "Cunningham Correspondence." In returning them, Marshall wrote that he had read Adams's letters "with regret." But the European war, rather than the "Cunningham Correspondence," was on the mind of the Chief Justice: "We are looking with anxiety towards the metropolis for political intelligence. Report gives much importance to the communications of Serrurier [the new French Minister],[92] & proclaims him to be charged with requisitions on our government, a submission to which would seem to be impossible.... I will flatter myself that I have not seen you for the last time. Events have so fully demonstrated the correctness of your opinions on subjects the most interesting to our country that I cannot permit myself to believe the succeeding legislature of Massachusetts will deprive the nation of your future services."[93]

As the Federalist faith in Great Britain grew stronger, Federalist distrust of the youthful and growing American people increased. Early in 1811, the bill to admit Louisiana was considered. The Federalists violently resisted it. Josiah Quincy declared that "if this bill passes, the bonds of this Union are virtually dissolved; that the States which compose it are free from their moral obligations, and that, as it will be the right of all, so it will be the duty of some, to prepare definitely for a separation[Pg 28]—amicably if they can, violently if they must."[94] Quincy was the embodiment of the soul of Localism: "The first public love of my heart is the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. There is my fireside; there are the tombs of my ancestors."[95]

The spirit of American Nationalism no longer dwelt in the breasts of even the youngest of the Federalist leaders. Its abode now was the hearts of the people of the West and South; and its strongest exponent was a young Kentuckian, Henry Clay, whose feelings and words were those of the heroic seventies. Although but thirty-three years old, he had been appointed for the second time to fill an unexpired term in the National Senate. On February 22, 1810, he addressed that body on the country's wrongs and duty: "Have we not been for years contending against the tyranny of the ocean?" We have tried "peaceful resistance.... When this is abandoned without effect, I am for resistance by the sword."[96] Two years later, in the House, to which he was elected immediately after his term in the Senate expired, and of which he was promptly chosen Speaker, Clay again made an appeal to American patriotism: "The real cause of British aggression was not to distress an enemy, but to destroy a rival!"[97][Pg 29] he passionately exclaimed. Another Patrick Henry had arisen to lead America to a new independence.

Four other young Representatives from the West and South, John C. Calhoun, William Lowndes, Langdon Cheves, and Felix Grundy were as hot for war as was Henry Clay.[98]

Clay's speeches, extravagant, imprudent, and grandiose, had at least one merit: they were thoroughly American and expressed the opinion of the first generation of Americans that had grown up since the colonies won their freedom. Henry Clay spoke their language. But it was not the language of the John Marshall of 1812.

Eventually the Administration was forced to act. On June 1, 1812, President Madison sent to Congress his Message which briefly, and with moderation, stated the situation.[99] On June 4, the House passed a bill declaring war on Great Britain. Every Federalist but three voted against it.[100] The Senate[Pg 30] made unimportant amendments which the House accepted;[101] and thus, on June 18, war was formally declared.

At the Fourth of July banquet of the Boston Federalists, among the toasts, by drinking to which the company exhilarated themselves, was this sentiment: "The Existing War—The Child of Prostitution, may no American acknowledge it legitimate."[102] Joseph Story was profoundly alarmed: "I am thoroughly convinced," he wrote, "that the leading Federalists meditate a severance of the Union."[103] His apprehension was justified: "Let the Union be severed. Such a severance presents no terrors to me," wrote the leading Federalist of New England.[104]

While opposition to the war thus began to blaze into open and defiant treason in that section,[105] the[Pg 31] old-time Southern Federalists, who detested it no less, sought a more practical, though more timid, way to resist and end it. "Success in this War, would most probably be the worst kind of ruin," wrote Benjamin Stoddert to the sympathetic James McHenry. "There is but one way to save our Country ... change the administration—... this can be affected by bringing forward another Virgn. as the competitor of Madison." For none but a Virginian can get the Presidential electors of that State, said Stoddert.

"There is, then, but one man to be thought of as the candidate of the Federalists and of all who were against the war. That man is John Marshall." Stoddert informs McHenry that he has written an article for a Maryland Federalist paper, the Spirit of Seventy-Six, recommending Marshall for President. "This I have done, because ... every body else ... seems to be seized with apathy ... and because I felt it sacred duty."[106]

Stoddert's newspaper appeal for Marshall's nomination was clear, persuasive, and well reasoned. It opened with the familiar Federalist arguments against the war. It was an "offensive war," which meant the ruin of America. "Thus thinking ... I feel it a solemn duty to my countrymen, to name John Marshall, as a man as highly gifted as any other in the United States, for the important office of Chief Magistrate; and more likely than any other to com[Pg 32]mand the confidence, and unite the votes of that description of men, of all parties, who desire nothing from government, but that it should be wisely and faithfully administered....

"The sterling integrity of this gentleman's character and his high elevation of mind, forbid the suspicion, that he could descend to be a mere party President, or less than the President of the whole people:—but one objection can be urged against him by candid and honorable men: He is a Virginian, and Virginia has already furnished more than her full share of Presidents—This objection in less critical times would be entitled to great weight; but situated as the world is, and as we are, the only consideration now should be, who amongst our ablest statesmen, can best unite the suffrages of the citizens of all parties, in a competition with Mr. Madison, whose continuance in power is incompatible with the safety of the nation?...

"It may happen," continues Stoddert, "that this our beloved country may be ruined for want of the services of the great and good man I have been prompted by sacred duty to introduce, from the mere want of energy among those of his immediate countrymen [Virginians], who think of his virtues and talents as I do; and as I do of the crisis which demands their employment.

"If in his native state men of this description will act in concert, & with a vigor called for by the occasion, and will let the people fairly know, that the contest is between John Marshall, peace, and a new order of things; and James Madison, Albert Gallatin[Pg 33] and war, with war taxes, war loans, and all the other dreadful evils of a war in the present state of the world, my life for it they will succeed, and by a considerable majority of the independent votes of Virginia."

Stoddert becomes so enthusiastic that he thinks victory possible without the assistance of Marshall's own State: "Even if they fail in Virginia, the very effort will produce an animation in North Carolina, the middle and Eastern states, that will most probably secure the election of John Marshall. At the worst nothing can be lost but a little labour in a good cause, and everything may be saved, or gained for our country." Stoddert signs his plea "A Maryland Farmer."[107]

In his letter to McHenry he says: "They vote for electors in Virga. by a general ticket, and I am thoroughly persuaded that if the men in that State, who prefer Marshall to Madison, can be animated into Exertion, he will get the votes of that State. What little I can do by private letters to affect this will be done." Stoddert had enlisted one John Davis, an Englishman—writer, traveler, and generally a rolling stone—in the scheme to nominate Marshall. Davis, it seems, went to Virginia on this mission. After investigating conditions in that State, he had informed Stoddert "that if the Virgns. have nerve to believe it will be agreeable to the Northern & E. States, he is sure Marshall will get the Virga. votes."[108][Pg 34]

Stoddert dwells with the affection and anxiety of parentage upon his idea of Marshall for President: "It is not because I prefer Marshall to several other men, that I speak of him—but because I am well convinced it is vain to talk of any other man, and Marshall is a Man in whom Fedts. may confide—Perhaps indeed he is the man for the crisis, which demands great good sense, a great firmness under the garb of great moderation." He then urges McHenry to get to work for Marshall—"support a cause [election of a peace President] on which all that is dear to you depends."[109] Stoddert also wrote two letters to William Coleman of New York, editor of the New York Evening Post, urging Marshall for the Presidency.[110]

Twelve days after Stoddert thus instructed McHenry, Marshall wrote strangely to Robert Smith of Maryland. President Madison had dismissed Smith from the office of Secretary of State for inefficiency in the conduct of our foreign affairs and for intriguing with his brother, Senator Samuel Smith, and others against the Administration's foreign[Pg 35] policy.[111] Upon his ejection from the Cabinet, Smith proceeded to "vindicate" himself by publishing a dull and pompous "Address" in which he asserted that we must have a President "of energetic mind, of enlarged and liberal views, of temperate and dignified deportment, of honourable and manly feelings, and as efficient in maintaining, as sagacious in discerning the rights of our much-injured and insulted country."[112] This was a good summary of Marshall's qualifications.

When Stoddert proposed Marshall for the Presidency, Smith wrote the Chief Justice, enclosing a copy of his attack on the Administration. On July 27, 1812, more than five weeks after the United States had declared war, Marshall replied: "Although I have for several years forborn to intermingle with those questions which agitate & excite the feelings of party, it is impossible that I could be inattentive to passing events, or an unconcerned observer of them." But "as they have increased in their importance, the interest, which as an American I must take in them, has also increased; and the declaration of war has appeared to me, as it has to you, to be one of those portentous acts which ought to concentrate on itself the efforts of all those who can take an active part in rescuing their country from the ruin it threatens.

"All minor considerations should be waived; the lines of subdivision between parties, if not absolutely effaced, should at least be convened for a time;[Pg 36] and the great division between the friends of peace & the advocates of war ought alone to remain. It is an object of such magnitude as to give to almost every other, comparative insignificance; and all who wish peace ought to unite in the means which may facilitate its attainment, whatever may have been their differences of opinion on other points."[113]

Marshall proceeds to analyze the causes of hostilities. These, he contends, were Madison's subserviency to France and the base duplicity of Napoleon. The British Government and American Federalists had, from the first, asserted that the Emperor's revocation of the Berlin and Milan Decrees was a mere trick to entrap that credulous French partisan, Madison; and this they maintained with ever-increasing evidence to support them. For, in spite of Napoleon's friendly words, American ships were still seized by the French as well as by the British.

In response to the demand of Joel Barlow, the new American Minister to France, for a forthright statement as to whether the obnoxious decrees against neutral commerce had or had not been revoked as to the United States, the French Foreign Minister delivered to Barlow a new decree. This document, called "The Decree of St. Cloud," declared that the former edicts of Napoleon, of which the American Government complained, "are definitively, and to date from the 1st day of November last [1810], considered as not having existed [non avenus] in regard to American vessels." The "decree" was dated April 28,[Pg 37] 1811, yet it was handed to Barlow on May 10, 1812. It expressly stated, moreover, that Napoleon issued it because the American Congress had, by the Act of May 2, 1811, prohibited "the vessels and merchandise of Great Britain ... from entering into the ports of the United States."[114]

General John Armstrong, the American Minister who preceded Barlow, never had heard of this decree; it had not been transmitted to the French Minister at Washington; it had not been made public in any way. It was a ruse, declared the Federalists when news of it reached America—a cheap and tawdry trick to save Madison's face, a palpable falsehood, a clumsy afterthought. So also asserted Robert Smith, and so he wrote to the Chief Justice.

Marshall agreed with the fallen Baltimore politician. Continuing his letter to Smith, the longest and most unreserved he ever wrote, except to Washington and to Lee when on the French Mission,[115] the Chief Justice said: "The view you take of the edict purporting to bear date of the 28tḥ of April 1811 appears to me to be perfectly correct ... I am astonished, if in these times any thing ought to astonish, that the same impression is not made on all." Marshall puts many questions based on dates, for the purpose of exposing the fraudulent nature of the French decree and continues:

"Had France felt for the United States any portion of that respect to which our real importance entitles us, would she have failed to give this proof of it? But[Pg 38] regardless of the assertion made by the President in his Proclamation of the 2ḍ of Novṛ 1810, regardless of the communications made by the Executive to the Legislature, regardless of the acts of Congress, and regardless of the propositions which we have invariably maintained in our diplomatic intercourse with Great Britain, the Emperor has given a date to his decree, & has assigned a motive for its enactment, which in express terms contradict every assertion made by the American nation throughout all the departments of its government, & remove the foundation on which its whole system has been erected.

"The motive for this offensive & contemptuous proceeding cannot be to rescue himself from the imputation of continuing to enforce his decrees after their formal repeal because this imputation is precisely as applicable to a repeal dated the 28tḥ of April 1811 as to one dated the 1st of November 1810, since the execution of those decrees has continued after the one date as well as after the other. Why then is this obvious fabrication such as we find it? Why has Mṛ Barlow been unable to obtain a paper which might consult the honor & spare the feelings of his government? The answer is not to be disguised. Bonaparte does not sufficiently respect us to exhibit for our sake, to France, to America, to Britain, or to the world, any evidence of his having receded one step from the position he had taken.

"He could not be prevailed on, even after we had done all he required, to soften any one of his acts so far as to give it the appearance of his having advanced one step to meet us. That this step, or rather[Pg 39] the appearance of having taken it, might save our reputation was regarded as dust in the balance. Even now, after our solemn & repeated assertions that our discrimination between the belligerents is founded altogether on a first advance of France—on a decisive & unequivocal repeal of all her obnoxious decrees; after we have engaged in a war of the most calamitous character, avowedly, because France had repealed those decrees, the Emperor scorns to countenance the assertion or to leave it uncontradicted.

"He avers to ourselves, to our selected enemy, & to the world, that, whatever pretexts we may assign for our conduct, he has in fact ceded nothing, he has made no advance, he stands on his original ground & we have marched up to it. We have submitted, completely submitted; & he will not leave us the poor consolation of concealing that submission from ourselves. But not even our submission has obtained relief. His cruizers still continue to capture, sink, burn & destroy.