by

J. G. EDGAR,

AUTHOR OF "BOYHOOD OF GREAT MEN," "CAVALIERS AND ROUNDHEADS," ETC.

LONDON:

S. O. BEETON, 248, STRAND.

1863.

In the following pages I have endeavoured to tell in a popular way the story of the Norman Conquest, and to give an idea of the principal personages who figured in England at the period when that memorable event took place; and I have endeavoured, I hope not without some degree of success, to treat the subject in a popular and picturesque style, without any sacrifice of historic truth.

With a view of rendering the important event which I have attempted to illustrate, more intelligible to the reader, I have commenced by showing how the Normans under Rolfganger forced a settlement in the dominions of Charles the Simple, whilst Alfred the Great was struggling with the Danes in England, and have recounted the events which led to a connexion between the courts of Rouen and Westminster, and to the invasion of England by William the Norman.

It has been truly observed that the history of the Conquest is at once so familiar at first sight, that it appears superfluous to multiply details, so difficult to realize on examination, that a writer feels himself under the necessity of investing with importance many particulars previously regarded as uninteresting, and that the defeat at Hastings was not the catastrophe over which the curtain drops to close the Saxon tragedy, but "the first scene in a new act of the continuous drama." I have therefore continued my narrative for many years after the fall of Harold and the building of Battle Abbey, and have traced the Conqueror's career from the coast of Sussex to the banks of the Humber and the borders of the Tweed.

For the same reason I have narrated the quarrels which convulsed the Conqueror's own family—have related how son fought against father, and brother against brother—and have indicated the circumstances which, after a fierce war of succession in England, resulted in the peaceful coronation of Henry Plantagenet, and the establishment of that great house whose chiefs were so long the pride of England and the terror of her foes.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Rolfganger and his Comrades:—Rolfganger's banishment—Settles in France—Ludicrous incident during the ceremony of Rolfganger'staking the oath of fealty to Charles the Simple | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| William the Conqueror:—His birth and parentage—Duke Robert's pride in him—Is declared successor to Robert the Devil—Duke Robert's death—Opposition to William's succession—Conspiracy headed by Bessi and Cotentin—William flees from them—Defeat of the conspirators, and accession of William to the ducal throne of Normandy—Hiscruelty—Good qualities of William | 8 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Danes in England:—The Saxons come to the assistance of the Britons—Seize on Britain—Formation of the Kingdom of England—The first inroad of the Danes—Death of Ethelred, and accession of Alfred the Great to the throne of England—Alfred in the swineherd's cottage—Visits the Danish camp—Drives the Danes from England—Sweyn, King of Denmark, invades England—Is bribed to retire—Massacre of St. Brice—Sweyn again invades England—His sudden death—Canute succeeds him—Treachery and punishment of Edric Streone—Canute's marriage—Death of Canute—Accession of Harold Harefoot—His death—Accession of Hardicanute—His death | 14 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Earl Godwin:—Ulf and Godwin—Canute's partiality to Godwin—Godwin becomes Earl of Wessex—Marries the daughter of Sweyn, King of Denmark—Godwin espouses the cause of Hardicanute—Godwin procures the crown of England for Edward the Confessor | 21 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Edward the Confessor:—His parentage—Death of his brother Alfred—Edward demands justice of Hardicanute—Ascends the English throne—Edward and the leper—Edward marries Edith, daughter of Godwin | 25 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The King and the King-maker:—Edward's Norman friends—Dislike of the Normans by the English—Quarrel between Eustace of Boulogne and the townsmen of Dover—Godwin's quarrel with Edward—Godwin is outlawed—William of Normandy visits England—His reception—Godwin returns to England—Is restored to power—Godwin's awful death | 29 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Matilda of Flanders:—William of Normandy determines to marry Matilda of Flanders—Matilda's pedigree—Her father's acquiescence in William's proposal—Her refusal to the espousal—William's love-making—Matilda's consent is obtained—The Pope's opposition to the marriage—William overcomes the Pope's scruples—Obtains a dispensation—Marries Matilda of Flanders | 36 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Siward the Dane:—His appearance—The mystic banner—Siward's reception by Hardicanute—Tostig's raillery and its punishment—Battle between Eadulph, Earl of Northumberland, and Siward—Siward is sent by Edward the Confessor to defend the Northumbrian coast—Death of Siward | 40 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Harold, the Saxon King:—Harold's personal appearance—Harold's first appearance in national affairs—His great military reputation—Harold proposes to visit Normandy—King Edward tries to dissuade him—He sets out—His cordial reception by Duke William—Harold accompanies William in a war against the Bretons—William extorts a promise from Harold to aid him in obtaining the English crown—Death of Edward the Confessor | 45 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Duke William and his Difficulties:—William has news of Harold's accession to the English throne—Harold is summoned by the Court of Rome to defend himself on the charges of perjury and sacrilege—He refuses to acknowledge the jurisdiction of the See of Rome—William is ordered by the Pope to invade England—He prepares to set out—William Fitzosborne overrules the objections of the Norman nobles. | 53 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Tostig, son of Godwin:—Tostig is made Earl of Northumberland—His cruelty—The Northumbrians force him to flee—Harold is sent against the insurgents—Tostig is deposed—His anger is turned against Harold—The massacre of Hereford—Tostig repairs to Flanders—Obtains aid from William of Normandy—Tostig's unfavourable reception by Sweyn, King of Denmark | 58 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Harold Hardrada:—His personal appearance—Harold at the battle of Stiklestad is wounded—Harold with his companions goes to Constantinople and takes service as a varing—The varings—Goes to Africa and Sicily, and makes an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem—Drives out the Moslems—Returns to Constantinople—Is enamoured of Maria, niece of the Empress Zoe—The Empress in love with Harold—Magnus, the illegitimate son of Olaf, usurps the throne of Norway—Harold, wishing to assert his superior claim, is detained in Constantinople by the Empress—Is delivered by a Greek lady—Rouses his companions, carries off Maria, and sets sail for Denmark—Hardrada shares the throne with Magnus—Death of Magnus—Tostig applies to Hardrada for assistance against Harold, King of England—Tostig makes a descent on England—Hardrada sails for England—The apprehensions of the Norwegians | 62 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Alarm in England:—Harold's indefatigable exertions for the welfare of England—Duke William claims fulfilment of Harold's promise—Harold's refusal—Duke William sends again to Harold—His offers again refused—William's threat—The alarm—Tostig lands in the North—Harold goes against him | 66 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Battle of Stamford Bridge:—Tostig and Hardrada burn Scarborough, take York, and encamp on the river Derwent at Stamford Bridge—The approach of the English—Harold's proposition to Tostig—Tostig's refusal—The battle—Hardrada is slain—Harold a second time offers peace—Is refused—Tostig is slain—The defence of the bridge—Termination of the conflict—The Norwegians leave England—Harold claims the booty as his own—Discontent in the army—Harold receives news of William's landing | 69 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Philip of France:—William of Normandy seeks the assistance of Philip, King of France—The French barons refuse to aid him in his invasion | 74 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Norman Armament:—William decides to invade England in August, 1066—William's treatment of the Saxon spy—The weather not being favourable, the Normans are filled with superstitious fears—William's strategy to calm their apprehensions—The Normans set sail—William's ship sails away from the rest—The landing—William burns his fleet—Overruns the county of Sussex—Receives intelligence of the Saxons' approach | 76 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Harold's Host:—Harold arrives in London—His ill-timed rashness—Not being able to attack William unawares, Harold halts at Epiton,and fortifies his position—The Saxon chiefs advise a retreat—Harold refuses to listen to them—William denounces Harold as a perjurer and liar—The effect of William's message on the Saxons—Gurth advises Harold to quit the army—The night before the battle | 81 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Battle of Hastings:—Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, blesses the Norman army—Arrangement of the Norman army—William in 1066—Superstitious fears of the Normans—William's address to his soldiers—Taillefer, the Norman minstrel—The attack—The Norman first division is repulsed—They renew the charge—Obstinate resistance of the Saxons—William's strategy—Its success—Harold and Leofwine are slain—Gurth's courageous resistance—Gurth is slain—Rout of the Saxons—William pitches his camp for the night | 85 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Body of Harold:—William returns thanks for his victory—Calls over the muster-roll—The Saxons seek to bury their dead—William refuses to allow the body of Harold to be buried—At the intercession of the monks of Waltham he relents—The search for the body—Harold's burial | 91 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Conqueror and the Kentishmen:—William finding no allegiance paid him, takes Dover and marches towards London—Is opposed by a large body of Kentishmen—The advancing wood—Parley with the Kentishmen—William turns towards the west, and crosses the Thames at Wallingford—The Saxon Wigod's treachery—Berkhampstead is taken | 93 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Edgar Atheling:—The Londoners determine upon crowning Edgar Atheling—Edgar's birth and parentage—His popularity with the people—Harold, afraid of Edgar's popularity, treats him with great respect and honour—Edgar is proclaimed king—Ansgar, the standard-bearer of the City of London, excites the people to deliver the keys of London to the Conqueror—Edgar Atheling, the archbishops, and chief citizens pay homage to William | 95 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Coronation of the Conqueror:—William marches towards London—The Abbot and inhabitants of St. Albans oppose him—William, doubting the propriety of accepting the crown, holds a council of war—The speech of Aimery de Thouars decides the council—Christmas day, 1066, is fixed for the coronation—The ceremony is performed by Aldred, Archbishop of York; Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury declining to crown him—Tumult during the coronation—The lion banner of Normandy is planted on the Tower of London, and the south and east of England given to William's followers—He embarks for Normandy—His enthusiastic reception—He refuses to take the oath of fealty to the Pope | 99 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Siege of Exeter:—During William's absence in Normandy, the Norman barons treat the Saxons with great cruelty—Saxon leagues are formed—William, receiving notice of the state of affairs in England, returns home—He ingratiates himself with the chiefs and the populace—William proceeds westward—Is opposed at Exeter—He attacks the town—Desperate resistance of the besieged—Exeter is taken—Somerset and Gloucester subjugated—Escape of Githa, Harold's mother—Bad treatment of the Saxon women | 103 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Matilda and Brihtrik:—Matilda's arrival and enthusiastic reception in England—Origin of Matilda's popularity—Her vindictive spirit—In her early years becomes enamoured of Brihtrik—Brihtrik does not reciprocate her affection—Brihtrik leaves Bruges—Matilda's indignation at his coolness—Probability of Brihtrik's speaking too freely about the Duchess Matilda—Matilda, after the siege of Exeter keeps Brihtrik's possessions as her share of the spoil—Brihtrik is imprisoned—His death | 106 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

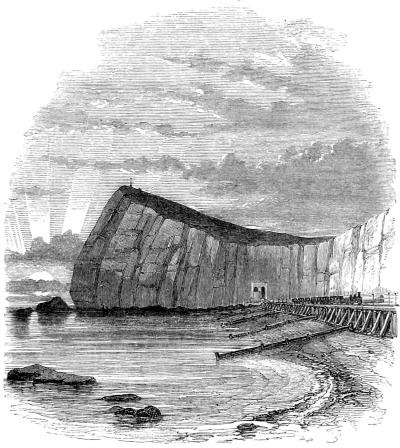

| The Normans in Northumberland:—State of the county of Northumberland in 1068—The Conqueror marches northward—York is taken—Robert Comine is deputed to extend the conquest as far as Durham—Eghelwin, Bishop of Durham's advice to Comine—The vengeance of the Northumbrians—The King of Denmark sends a fleet to the assistance of the English—The Saxons and Danes march upon York—The Normans are driven into the citadel—The citadel is taken—William's wrath at the death of Comine and the destruction of York—He bribes the Danes to depart—William again marches upon York—York is once more taken by the Normans—After ravaging Northumberland, the Normans reach Durham—The bishop and clergy of Durham set out for Holy Island—William enters Durham, and surprises the Saxons—William's guides, marching to Hexham, lose the way, and are separated from the rest of the army—The army is regained—William halts at Hexham—The subjugated territory is divided amongst William's nobles—The Normans erect castles for the better governance of the Northumbrians | 109 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Cospatrick and the Conqueror:—William determines to conciliate the Northumbrians—Cospatrick—His birth and parentage—The crimes of the house of Godwin—Cospatrick's enmity to Harold—Cospatrick claims the earldom of Northumberland—William's bargain with Cospatrick | 115 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Saxon Saints and Norman Soldiers:—The saving of the church of St. John of Beverley—The inhabitants of Beverley take refuge in the church of St. John—The Normans hear reports of the riches lodged within the walls of the church—Toustain heads the Normans in the pillage of the church—Toustain's misadventure—Superstitious terror of the Normans | 118 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Reduction of Chester:—William determines to take Chester—The soldiers murmur—William marches into Chester—Gherbaud, a Fleming, made Earl of Chester—Gherbaud, finding the earldom too much trouble, resigns—Hugh le Loup is appointed in his stead—His parentage—Nigel joins Hugh le Loup at Chester—Gilbert de Lacy is granted the domain of Pontefract—Blackburn and Rochdale succumb to him | 121 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

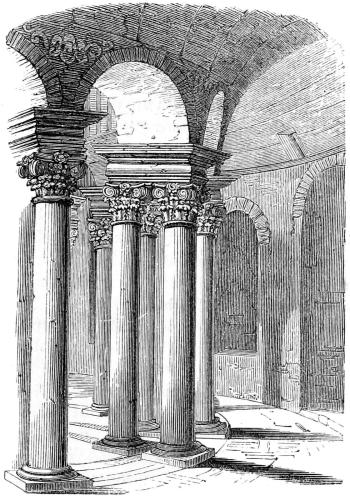

| Lanfranc of Pavia:—The Pope's legates arrive in London—Deposition of the Saxon bishops—Lanfranc is appointed to the Archbishopric of Canterbury—Lanfranc's birth-place—His fame at Bec-Hellouin—Lanfranc gains the friendship of William the Norman—Lanfranc opposes William's marriage—He gains a dispensation for William—Is restored to favour—Is made Abbot of Caen—William's delight at Lanfranc's appointment to the province of Canterbury—The Pope's letter to Lanfranc—Lanfranc's entry into Canterbury—The church in ruins—Lanfranc gains the primacy of England for Canterbury—Undertakes a revision of the Scriptures—The Saxons averse to the revision—Lanfranc the people's champion | 124 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Edwin and Morkar:—Their personal appearance—Edwin the handsomest man of his age—They took no part in the battle of Hastings—Aspire to the throne—Edgar Atheling's adherents too strong—Go to York—Their plans—William attempts to conciliate them—William promises his daughter in marriage to Edwin—Edwin and Morkar accompany William to the Continent—William refuses to give his daughter to Edwin—Edwin and Morkar escape from Court—Their enterprise fails—Reconciliation to William—A mighty conspiracy formed—The camp of refuge—Morkar is deluded by William's promises and imprisoned—Edwin resolves to leave Ely—Is betrayed by three of his officers—Is attacked by the Normans—Attempts to escape—Edwin's death—William's grief | 128 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Ivo Taille-Bois:—His unpopularity—His marriage to Lucy, sister of Edwin and Morkar—His tyranny—His various modes of annoyance—His oppression of the monks of Spalding—The monks leave Spalding—Some Angevin monks are substituted in their place | 133 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Hereward the Saxon:—Hereward, living in Flanders, is told by some exiles of the spoliation of his home—He sets out for England—Assembles his friends and retakes his paternal home—His popularity—Is made captain of the camp at Ely—Is admitted a member of the high Saxon militia—Is sneered at by the Norman knights—Turauld, the fighting churchman—Turauld is appointed Abbot of Peterborough—Hereward makes a descent on the abbey and carries off the crosses, sacred vestments, &c.—Turauld arrives at Peterborough—Ivo Taille-Bois proposes to Turauld to attack the camp of Ely—Hereward attacks Turauld's soldiers at the abbey, seizes upon the abbot and his attendants, and detains them prisoners—Sweyn, King of Denmark, fits out a fleet for the assistance of the Saxons—Sweyn joins Hereward at Ely—William bribes him to return—Departure and sacrilege of the Danes—The Normans commence siege operations—Hereward attacks the workmen—Hereward is suspected of being in league with the Evil One—Ivo Taille-Bois procures the services of a witch to disenchant Hereward's operations—Hereward's bonfire—Blockade of the Isle of Ely—Treachery of the monks of Ely—Rout of the Saxons—Hereward's escape—His daring attack on the Norman station—Exploits of Hereward and his followers—Hereward's marriage—Hereward accepts the king's peace—His treacherous assassination—Valorous defence—Asselm's remark | 137 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Building of Battle Abbey:—William begins to build Battle Abbey—Deficiency of water—William's promise—The abbey built—Endowment of the abbey | 147 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Malcolm Canmore:—William determines to invade Scotland—Malcolm's parentage—Siward, upon Malcolm's flight from Scotland, protects him—Edward the Confessor's court—The Scots request the restoration of Malcolm—Malcolm prepares to attack Macbeth—Defeat of Macbeth—His death—Lulach attempts to usurp the throne—His death—Malcolm is crowned at Scone—A conspiracy is formed to dethrone Malcolm—The conspirators defeated—Malcolm's ingratitude to the English—Northumberland devastated by the Scots—Malcolm shelters Edgar and Margaret Atheling—Malcolm marries Margaret Atheling—Malcolm raises an army to vindicate Edgar Atheling's right to the English throne—Treaty with William | 148 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| The Death of Cospatrick:—Cospatrick attempts to draw Malcolm from Northumberland—Durham cathedral in disorder—Deposition of the Bishop of Durham—Cospatrick is deprived of the earldom of Northumberland—He goes to Flanders—The clergy enemies to Cospatrick—Cospatrick's pilgrimage to the Holy Land—His illness—Sends to Melrose for the hermits Aldwin and Turgot—Cospatrick's gifts—His death—His son—Burial in Norham church—Norham a memorial of his greatness | 153 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Atheling and His Allies:—Malcolm Canmore promises to aid Edgar Atheling—Malcolm's inability to do so—Atheling seeks a reconciliation with William—Obtains it—Atheling being suspected, again flies to Scotland—Personal appearance of Edgar Atheling—Atheling seeks allies in Flanders—Is disappointed—Philip of France offers his assistance—Offers Atheling the fortress of Montreuil—Atheling's misfortunes—His fleet lost at sea—Determines to seek peace with William—Joins William at Rouen—His amusements | 157 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Fitzosborne and de Gael:—The marriage at Norwich—William's disapproval thereof—The marriage feast—Signs of a coming storm—The conspiracy—The conspirators apply to Sweyn, king of Denmark,for aid—Roger Fitzosborne raises an army at Hereford—Is stopped at Worcester—Fitzosborne excommunicated—The battle at Worcester—Defeatof Fitzosborne—De Gael raises his standard at Cambridge—Is defeated at Fagadon—De Gael escapes—Flies to Norwich—Goes to Brittany for aid—The Bretons expelled from England—Sweyn's descent on the eastern coast—Fitzosborne refuses William's present at Easter—William's anger | 162 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Waltheof, Son of Siward:—Tostig usurps the earldom of Northumberland—Waltheof figures as Earl of Huntingdon—Waltheof submits to the Conqueror—He joins the Northumbrians in their insurrection—His share in the death of Comine—Prodigies of valour—Reconciliation with William—Marriage to Judith—Friendship with Vaulcher—Fitzosborne and De Gael try to persuade him to join their conspiracy—Promises secrecy—Is betrayed by his wife—Is confined in Winchester Castle—Sentenced to death—Fearing a riot, Waltheof is privately executed—Judith, Waltheof's wife, is destined for Simon de Senlis—Her dislike to the match—Judith repairs to Croyland—Her death in poverty | 167 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

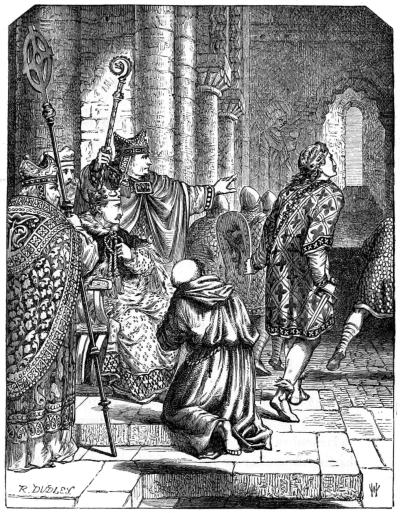

| Wulstan, Bishop of Worcester:—Wulstan accompanies Edgar Athelingto make his submission to William—Wulstan a simple weak-minded man—Wulstan is confirmed in his diocese—His services to the Norman king—Lanfranc reports Wulstan incapacitated—Is summoned to the great council in Westminster church—Is commanded to give up his robes and staff—Resigns his staff at the tomb of the Confessor—Wulstan is entreated to resume his episcopal robes—Wulstan beloved by the Saxons | 173 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Robert Curthose:—William's dismal forebodings—Robert, his eldest son—Robert recognised as heir of Normandy—Badly trained—His good qualities—His nickname—Robert claims Maine—William refuses to cede it to him—Robert's indignation—William Rufus' and Henry Beauclerc's practical joke—Its evil consequences—Robert attempts to seize Rouen—His failure—Robert's bad counsellors—Robert asks Normandy,or part of England, of his father—Being refused, he leaves Normandy and goes to Flanders—Is everywhere well received—His waste of money | 176 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| The Conqueror and his Heir:—Curthose craves support from Philip of France—Repairs to Gerberoy—Curthose's reception at Gerberoy—Matilda sends money to Curthose—William's displeasure—Matilda still sends to Curthose—William upbraids her—Matilda's maternal affection—William orders Samson the Breton to have his eyes put out—Samson escapes—Curthose raises an army—William besieges Curthose in Archembrage—Curthose's sally—His success—Hand to hand with his father—William unhorsed—His rescue—William refuses to be reconciled with Curthose—Forgives Curthose—Malcolm Canmore invades England—Curthose is sent to repulse him—Malcolm retreats into Scotland—Curthose founds Newcastle—Matilda of Flanders dies—William's quarrel with Curthose again breaks out | 180 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| Odo, Bishop of Bayeux:—Odo, regent of England—William enriches his relations on his mother's side—Odo, no shaveling—The warrior-monk—Odo celebrates mass at Hastings—Leads the cavalry at that battle—Odo is created Grand Justiciary of England—Earl of Hereford—Odo, during William's absence, behaves badly—The murder of Liulf—Vaulcher attempts to mediate between Leofwin and Gislebert, and the relations of Liulf—Meets the Saxons at Gateshead—Eadulf, the Saxon spokesman—Eadulf incites the Northumbrians to slay the bishop—Odo marches northward to punish the murderers—The Saxons, unable to take Durham, disperse—Odo's cruelty—Odo prepares to leave England for Italy—Reasons for doing so—William much displeased at Odo's intention—Odo intercepted off the Isle of Wight—Arraigned before the council of barons—William's impeachment of Odo—William sentences Odo—Odo defies his authority—Odo is carried to Normandy and imprisoned | 184 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

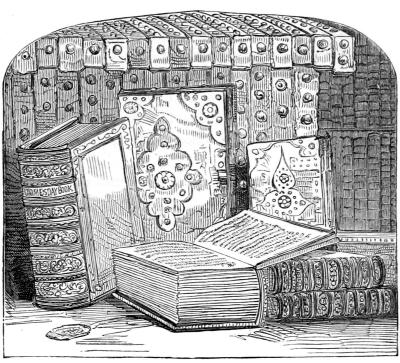

| Doomsday Book:—William begins to think about casting up his subjects' accounts—His commissioners—Bad understanding between the king and the barons—The manner of carrying out the undertaking—The council for the discussion of the Doomsday Book—The Goddess of Discord in the council—William asserts himself proprietor of all the land that belonged to Edward the Confessor, Harold, and the house of Godwin—Several barons renounce their allegiance—Their descendants | 189 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| The Conqueror's Death:—Louis le Gros—Curthose and Beauclerc at Conflans—The quarrel between Louis and Beauclerc—Philip ravages Normandy—William goes against him—Christina Atheling is persuaded to take the veil—Edgar is sent on a pilgrimage—The bone of contention—William's lying-in—Curthose joins Philip—William reaches Mantes—The town on fire—The accident—William is removed to the priory of St. Gervase—Conscience-stricken—William's bequests—Death of William | 192 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| The Burial at Caen:—Consternation in Rouen—Inside the priory of St. Gervase—The conqueror's body deserted—The Archbishop of Rouen attends to the funereal honours—Interruption of the ceremony—Fitzarthur is recompensed—The Anglo-Norman barons decide for Robert as King of England | 199 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| The Red King:—William Rufus—Personal appearance—Gains the support of Lanfranc—Wulnoth and Morkar committed to prison—Odo, bishop of Bayeux, at the head of a conspiracy to dethrone William—Lanfrancas prime minister—Rufus conciliates the Saxon Thanes—The insurgents repulsed at Rochester—Curthose is bribed to let William remain on the throne—William forgets his promises to the Anglo-Saxons—Lanfranc's disgust at his perfidy—Death of Lanfranc—Rufusa bachelor—His dissolute morals—Ravages committed by William's followers—London Bridge built—Westminster Hall founded—Discontent in the land | 203 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| Rufus and the Jews:—The Jews in England—Favour with Rufus—The disputation—Conversion of the young Jew—William's avarice | 210 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| Rufus and the Scots:—William's longings for Normandy—Atheling being expelled from Normandy, once more takes refuge with Malcolm Canmore—Canmore invades England—William patches up a peace with Curthose, and prepares to march against the Scots—Malcolm falls back—Everything wrong with the English—Malcolm's defiance—Peace—Rufus being sick, sends for Malcolm to settle disputes—Rufus treats him badly—Malcolm ravages Northumberland as far as Alnwick—The castle of Ivo de Vesci besieged—Hammond Morael—His deliverance of the garrison—Malcolm's death—Morael's escape—The sally—Rout of the Scots—Malcolm's burial—Donald Bane usurps the Scottish throne—Atheling returns to England | 213 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| Robert de Moubray:—Possessions of Moubray—The conspiracy—Moubray suspected—The King marches northward—Tynemouth taken—Bamburgh impregnable—Erection of Malvoisin—Moubray captured—Moubray's wife defends the Castle of Bamburgh—Surrender of Bamburgh—Moubray imprisoned at Windsor—His death | 218 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| Henry Beauclerc:—Personal appearance of Beauclerc—A native of England—His manners—His learning—Military education—Addicted to gaming—Beauclerc's avarice—Beauclerc lends money to Curthose—Lord of Cotentin—Selection of a chaplain—Takes part with Curthose in the defence of Normandy—Firm dealing at Rouen—Curthose comes to terms with Rufus—They besiege Henry in the Castle of Mont St. Michael—The Red King in danger—Defence of the saddle—Want of water in the fortress—Curthose grants permission to Beauclerc to get water—Beauclerc defeated—Departs to Brittany—Beauclerc feels assured he will ascend the throne of England—Is elected governor of Damfront—Rufus, jealous of Beauclerc, invites him to England—Joins his brother—Fondness for the chase—"Deersfoot"—Presentiments | 221 |

| CHAPTER LI. | |

| The Death of Rufus:—Rufus at Malwood—His vision—The Abbot of Gloucester's despatch—The breakfast—The six arrows—Departure for the chase—Tyrel and Rufus hunt together—The King's bow-string breaks—Commands Tyrel to shoot—The King's death—Tyrel escapes to France—The King's last ride | 227 |

| CHAPTER LII. | |

| A Change of Fortune:—Beauclerc goes to Winchester—William de Breteuil protests against Henry having the keys—Beauclerc secures the public money and regal ornaments—Is crowned at Westminster—Curthose's adherents—Beauclerc marries Edith, daughter of Margaret Atheling—Edith changes her name to Maude—Godrick and Godiva—Where is Curthose? | 231 |

| CHAPTER LIII. | |

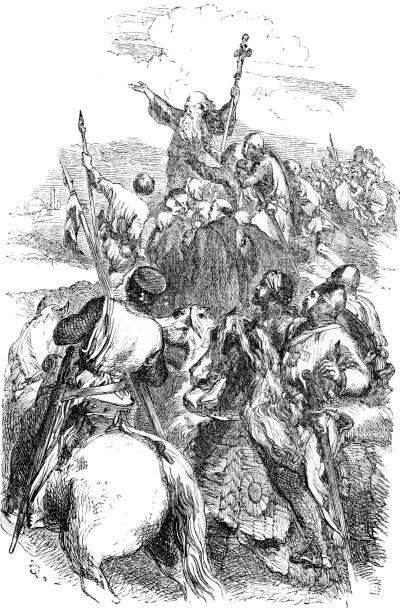

| Curthose at the Crusade:—Peter the Hermit—Success of his preaching—Curthose and Atheling resolve to take part in the Crusade—Rufus supplies them with money—Curthose's popularity—Edgar Atheling does not go with Curthose—Atheling sets out for Scotland, to dethrone Donald Bane—Curthose meets the other princes at Constantinople—Curthose's valour—At Antioch—Edgar Atheling joins Curthose—Atheling and Curthose the terror of the Saracens—Election of the King of Jerusalem—Curthose declines the honour—Death of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux—Curthose at Conversano—The territory of Conversano—Curthose marries Sybil, daughter of the Count of Conversano—Waste of time | 234 |

| CHAPTER LIV. | |

| Beauclerc and Curthose:—Ralph Flambard, "the fighting bishop," is imprisoned—Flambard incites Curthose to invade England—Curthose embarks for England—Curthose sells his birthright—Resigns his pension in favour of the queen—His indignation at finding himself duped—The castle of Rouen—Beauclerc proposes to purchase Normandy—Being refused, he prepares to take it by force—Tinchebray—The battle—Fortune against the English—Treason!—Nigel de Albini—Curthose and Atheling captured—Curthose imprisoned in Cardiff—Attempts to escape—Is subjected to a rigorous durance—Edgar Atheling's old age | 242 |

| CHAPTER LV. | |

| After Tinchebray:—William Clito—Louis of France attempts to place Clito on the throne of Normandy—Death of Clito—Beauclerc's reputation not so good—The Queen Maude's popularity—Death of Henry's son—Geoffrey of Anjou—His marriage to the daughter of Henry—Stephen of Bouillon seizes the crown of England—The treaty of Wallingford—Henry II.—Conclusion | 247 |

DANES, SAXONS, AND NORMANS;

or,

Stories of our Ancestors.

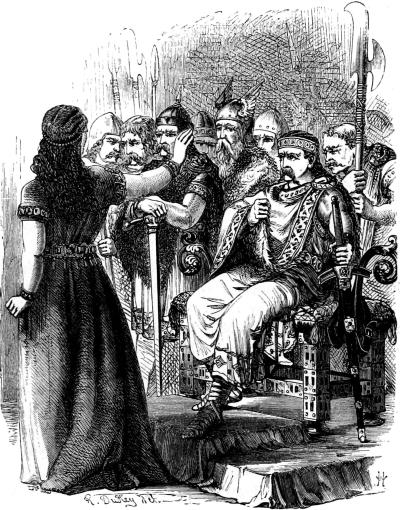

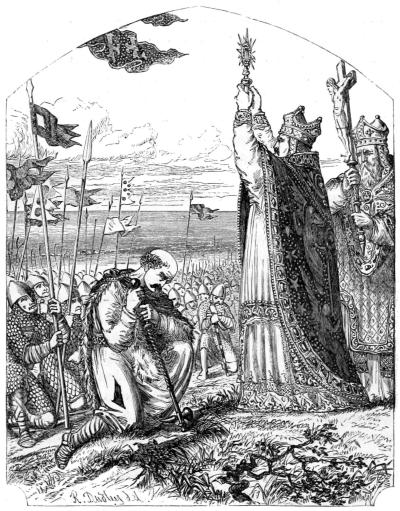

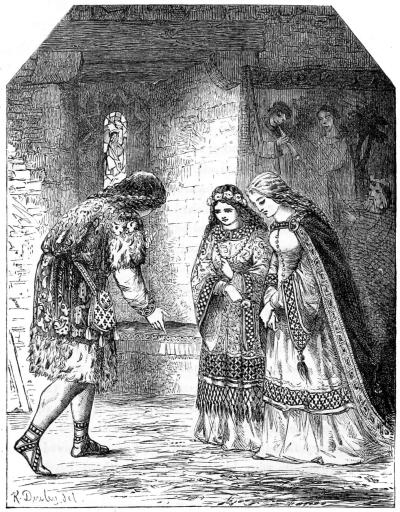

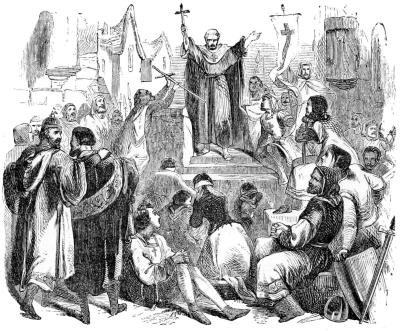

Hilda's appeal to Harold Harfagher.

ROLFGANGER AND HIS COMRADES.

One day towards the close of the ninth century, Harold, King of Norway, exasperated at the insubordination and contumacy of the chiefs among whom that land of mountain, and forest, and fiord[Pg 2] was divided, vowed not to cut his fair hair till he had reduced the whole country to his sovereign authority. The process proved, as he doubtless foresaw, somewhat difficult and slow. Indeed, the chiefs of Norway, who were, in fact, petty kings, disputed the ground inch by inch, and Harold was occupied for so many years ere consummating his victories, that his hair, growing ridiculously long and thick, led to his receiving the surname of "Hirsute."

Even after having sustained numerous defeats on the land, the fierce chiefs—all Vikings, and, like their adversaries, worshippers of Odin—taking to the sea, ravaged the coasts and islands, and excited the Norwegians to rebellion. Harold, however, resolved to do his work thoroughly, went on board his war-fleet, sailed in pursuit of his foes, and, having sunk several of their vessels, forced the others to seek refuge in the Hebrides, where the exiled war-chiefs—many of them ancestors of the Anglo-Norman nobles—consoled themselves with horns of potent drink, with schemes for conquering kingdoms, and with the hope of better fortune and brighter days.

It appears that in the long and arduous struggle which gave him the sole and undisputed sovereignty of Norway, Harold had been faithfully served by a Jarl named Rognvald; and it was to this Jarl's timber-palace, in Möre, that the victorious King repaired to celebrate the performance of his vow. Elate with triumphs, perhaps more signal than he had anticipated, Harold made himself quite at home; and having, before indulging in the Jarl's good cheer, refreshed himself with a bath and combed his hair, he requested Rognvald to cut off his superfluous locks.

"Now, Jarl," exclaimed Harold, when this operation was over, "methinks I should no longer be called 'Hirsute.'"

"No, King," replied Rognvald, struck with surprise and pleasure at the improvement in Harold's appearance; "your hair is now so beautiful that, instead of being surnamed 'Hirsute,' you must be surnamed 'Harfagher.'"

It happened that Rognvald, by his spouse Hilda, had a son named Rolf, or Roll, who was regarded as the foremost among the noble men of Norway. He was as remarkable for his sagacity in peace, and for his courage in war as for his bulk and stature, which were[Pg 3] such that his feet touched the ground when he bestrode the horses of the country. From this peculiarity the son of Rognvald found himself under the necessity of walking when engaged in any enterprise on the land; and this circumstance led to his becoming generally known among his countrymen as Rolfganger.

But the sea appears to have been Rolfganger's favourite element. From his youth he had delighted in maritime adventures, and in such exploits as made the men of the north celebrated as sea-kings; and one day, when returning from a cruise in the Baltic, he, while off the coast of Wighen, shortened sail, and ventured on the exercise of a privilege of impressing provisions, long enjoyed by sea-kings, and known as "strandhug." But he found that, with Harold Harfagher on the throne, and stringent laws against piracy in force, the rights of property were not thus to be set at defiance. In fact, the peasants whose flocks had been carried away complained to the King; and the King, without regard to the offender's rank, ordered him to be tried by a Council of Justice.

Notwithstanding Rognvald's services to the King and his personal influence with Harold Harfagher, Rolfganger's chance of escaping sentence of banishment appeared slight. Moved, however, by maternal tenderness, Hilda, the spouse of Rognvald, made an effort to save her son. Presenting herself at the rude court of Norway, she endeavoured to soften the King's heart.

"King," said she, "I ask you, for my husband's sake, to pardon my son."

"Hilda," replied Harold, "it is impossible."

"What!" exclaimed Hilda, rearing herself to her full height; "am I to understand that the very name of our race has become hateful to you? Beware," continued she, speaking in accents of menace, "how you expel from the country and treat as an enemy a man of noble race. Listen, King, to what I tell you. It is dangerous to attack the wolf. When once he is angered, let the herd in the forest beware!"

But Harold Harfagher was determined to make the laws respected, and, notwithstanding Hilda's vague threats, a sentence of perpetual exile was passed against her tall son. Rolfganger, however,[Pg 4] was not a man to give way to despair. Fitting out his ships in some rocky coves, still pointed out, he embarked at an island off the mouth of Stor-fiord, took a last look at his native country, with its rugged scenery, its rapids, cataracts, and fiords, forests of dark pine and mountains of white snow, herds of reindeer and clouds of birds, and, sailing for the Hebrides, placed himself at the head of the banished Norwegians, who speedily, under his auspices, resolved on a grand piratical enterprise, which they did not doubt would result in conquest and plunder.

Having cut their cable and given the reins to the great sea-horses—such was their expression—the Normans made an attempt to land in England, where Alfred the Great then reigned. Defeated in this attempt by the war-ships with which the Saxon King guarded the coast, they turned their prows towards France, and, entering the mouth of the Seine, sailed up the river, pillaging the banks as they proceeded, and, with little delay, found themselves admitted into Rouen, on which they fixed as their future capital.

It was the year 876 when Rolfganger and his comrades sailed up the Seine; and on becoming aware of their presence in France, Charles the Simple, who then, as heir of Charlemagne, wielded the French sceptre with feeble hand, summoned the warriors of his kingdom to stop the progress of the Normans. An army, accordingly, was mustered and sent, under the command of the Duke of France, to encounter the grim invaders. Before fighting, however, the French deemed it prudent to tempt the Normans with offers of lands and honours, on condition of their submitting to King Charles, and sent messengers to hold a parley. But the Normans treated the proposals with lofty disdain.

"Go back to your King," cried they, "and say that we will submit to no man, and that we will assert dominion over all we acquire by force of arms."

With this answer the ambassadors returned to the French camp, and ere long the Normans were attacked in their entrenchments. But Rolfganger and his comrades rushed to arms, and fought with such courage that the French suffered a complete defeat, and the Duke of France fell by the hand of a fisherman of Rouen.

The Normans, after vanquishing the host of King Charles, found themselves at liberty to pursue their voyage; and Rolfganger, availing himself of the advantage, sailed up the Seine, and laid siege to Paris. Baffled in his attempt to enter the city, the Norman hero consoled himself by taking Bayeux, Evreux, and other places, and gradually found himself ruling as a conqueror over the greater part of Neustria. At Evreux, he seized as his prey a lady named Popa, the daughter of Count Beranger, whom he espoused; and, becoming gradually more civilized, he rendered himself wonderfully popular with the inhabitants of the district subject to his sway.

Meanwhile the French suffered so severely from the hostility of the Normans, that Charles the Simple recognised the expediency of securing the friendship of warriors so formidable. With this object he sent the Archbishop of Rouen to negotiate with Rolfganger, and the result was that the Sea-King consented to become a Christian, to wed Gisla, the daughter of Charles, and to live at peace with France, on condition that the French monarch ceded to him the province of Neustria.

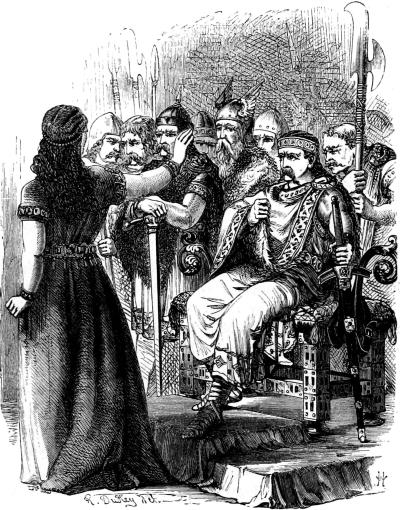

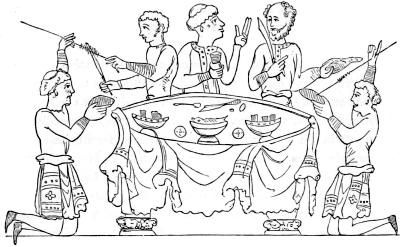

Matters having reached this stage, preparations were made to ratify the treaty in a solemn manner, and for that purpose Charles the Simple and Rolfganger agreed to hold a conference at the village at St. Clair, on the green-margined Epte. Each was accompanied by a numerous train, and, while the French pitched their tents on one side of the river, the Normans pitched theirs on the other. At the appointed hour, however, Rolfganger crossed the Epte, approached the chair of state, placed his hand between those of the King, took, without kneeling, the oath of fealty, and then, supposing the ceremony was over, turned to depart.

"But," said the Frenchmen, "it is fitting that he who receives such a gift of territory should kneel before the King and kiss his foot."

"Nay," exclaimed Rolfganger; "never will I kneel before a mortal; never will I kiss the foot of any man."

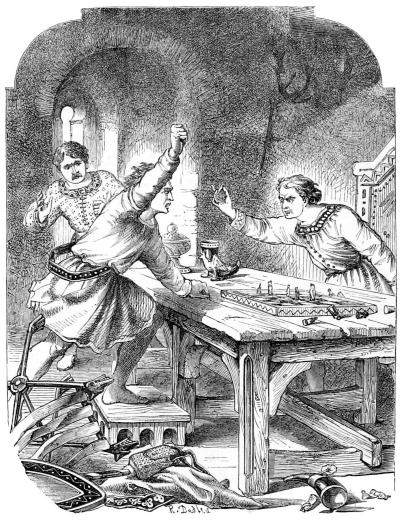

The French counts, however, insisted on this ceremony, and Rolfganger, with an affectation of simplicity, made a sign to one of his comrades. The Norman, obeying his chief's gesture, immediately stepped forward and seized upon Charles's foot. Neglecting, however,[Pg 6] to bend his own knee, he lifted the King's foot so high in the effort to bring it to his lips, that the chair of state was overturned, and the heir of Charlemagne lay sprawling on his back.

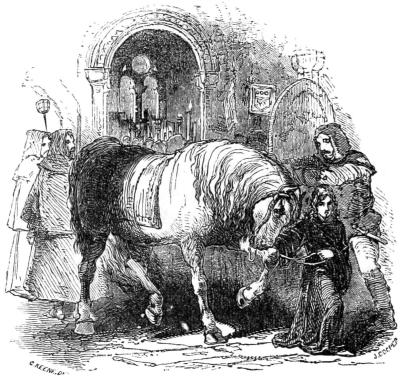

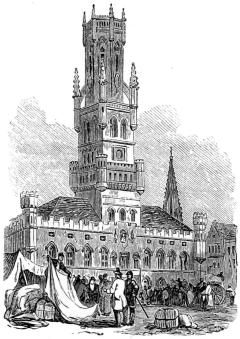

Rolfganger paying homage to Charles the Simple.

At this ludicrous incident the Normans raised shouts of derisive laughter, and the French held up their hands in horror. For a few moments all was confusion, but fortunately no serious quarrel resulted; and soon after, Rolfganger was received into the Christian Church, and married to Gisla, the King's daughter, at Rouen.

Rolfganger, having begun life anew as a Christian and a Count, divided the territory of Neustria among his comrades, and changed its name to Normandy. Maintaining internal order by severe laws, and administering affairs with vigour, he soon became famous as the most successful justiciary of the age. Such was the security felt under his government, that mechanics and labourers flocked to establish themselves in the newly-founded state, and the Normans[Pg 7] applied themselves to the arts of peace with as much ardour as they had previously exhibited in their predatory enterprises.

Gradually adopting the French tongue, and refining their manners, Rolfganger's comrades and their heirs were metamorphosed from a band of pagan sea-kings and pirates into the most refined, the most chivalrous, and the most religious race in Christendom—orators from their cradle; warriors charging in chain mail, with resistless courage, at the head of fighting men; and munificent benefactors to religious houses, where holy monks kept alive the flame of ancient learning, and dispensed befitting charities to the indigent and poor.

One glorious afternoon in the autumn of the year 1023, some damsels of humble rank were making merry and dancing joyously under the shade of trees in the neighbourhood of Falaise, when, homeward from the chase, accompanied by knights, squires, and grooms, with his bugle at his girdle, his hawk on his wrist, and his hounds running at his horse's feet, came, riding with feudal pride, that Duke of Normandy whom some, in consideration, perhaps, of substantial favours, called Robert the Magnificent, and whom others, in allusion to his violent temper, characterized as Robert the Devil.

Not being quite indifferent to female charms, Duke Robert reined up, and, as he did so, with an eye wandering from face to form and from form to face, the grace and beauty of one of the dancers arrested his attention and touched his heart. After expressing his admiration, and learning that she was the daughter of a tanner, the duke pursued his way. But he was more silent and meditative than usual; and,[Pg 9] soon after reaching the Castle of Falaise, he deputed the most discreet of his knights to go to the father of the damsel to reveal his passion and to plead his cause.

It appears that the negotiation was attended with considerable difficulty. At first, the tanner, who had to be consulted, treated the duke's proposals with scorn; but, after a pause, he agreed to take the advice of his brother, who, as a hermit in the neighbouring forest, enjoyed a high reputation for sanctity. The oracle's response was not quite consistent with his religious pretensions. Though dead, according to his own account, to the vanities of the world, the hermit would seem to have cherished a lingering sympathy with human frailty. At all events, he declared that subjects ought, in all things, to conform to the will of their prince; and the tanner, without further scruple, allowed his daughter to be conducted to the castle of Robert the Devil. In due time Arlette gave birth to a son, destined, as "William the Conqueror," to enrol his name in the annals of fame.

It was the 14th of October, 1024, when William the Norman drew his first breath in the Castle of Falaise. Arlette had previously been startled with a dream, portending that her son should reign over Normandy and England; and no sooner did William see the light than he gave a pledge of that energy which he was in after years to exhibit. Being laid upon the floor, he seized the rushes in his hands, and grasped them with such determination, that the matrons who were present expressed their astonishment, and congratulated Arlette on being the mother of such a boy.

"Be of good cheer," cried one of them, with prophetic enthusiasm; "for verily your son will prove a king!"

At first Robert the Devil did not deign to notice the existence of the boy who was so soon to wear the chaplet of golden roses that formed the ducal diadem of Normandy; but William, when a year old, was presented to the duke, and immediately won the feudal magnate's heart.

"Verily," said he, "this is a boy to be proud of. He is wonderfully like my ancestors, the old dukes of the Normans, and he must be nurtured with care."

From that time the mother and the child were dear to Duke Robert. Arlette was treated with as much state as if a nuptial benediction had been pronounced by the Archbishop of Rouen: and William was educated with more than the care generally bestowed, at that time, on the princes of Christendom. At eight he could read the "Commentaries of Cæsar;" and in after life he was in the habit of repeating a saying of one of the old counts of Anjou, "that a king without letters is a crowned ass."

It happened that, about the year 1033, Robert the Devil, reflecting on his manifold transgressions, and eager to make atonement, resolved on a penitential pilgrimage to Jerusalem. A serious obstacle, however, presented itself. The Norman nobles, with whom the descendant of Rolfganger was in high favour, on being convened, protested loudly against his departure.

"The state," they with one voice exclaimed, "will be in great peril if we are left without a chief."

"By my faith!" said Robert, "I will not leave you without a chief. I have a little bastard—I know he is my son; and he will grow a gallant man, if it please God. Take him, then, as your liege lord; for I declare him my heir, and bestow upon him the whole Duchy of Normandy."

No objections were raised to the Duke's proposal. In fact, everything seems to have gone more smoothly than could have been anticipated. William was formally presented to the assembly, and each feudal lord, placing his hand within those of the boy, took the oath of allegiance with such formalities as were customary.

Having arranged matters to his satisfaction, and placed his son under the protection of the court of France, Duke Robert took the pilgrim's scrip and staff, and, attended by a band of knights, set out for the Holy Sepulchre. On reaching Asia Minor he fell sick, and, dispensing with the company of his knights, hired four Saracens to carry him in a litter onward to Jerusalem. When approaching the Holy City, he was met by a palmer from Normandy, and waved his hand in token of recognition.

"Palmer," cried the duke, "tell my valiant lords that you have seen me carried towards Paradise on the backs of fiends."

The fate of Duke Robert was never clearly ascertained; but from his pilgrimage to Jerusalem it is certain that he did not return to Normandy. Within a year of his departure, indeed, news reached Rouen that the pilgrim-duke had breathed his last at Nice; and the Normans, though without implicitly believing the report, gradually came to think of him as one who had gone to his long home.

With news of the death of Robert the Magnificent came the crisis of the fate of "William the Bastard." Notwithstanding the oath taken with so much ceremony, the Norman barons were in no humour to submit to a boy—and to a boy, especially, who was illegitimate.

It was in vain that the guardians of young William exerted all their energies to establish his power. One pretender after another was put down by the strong hand. But the old Norman seigneurs, who had submitted with reluctance to the rule of legitimate princes, steeled their hearts against the humiliation of bending their knees to a bastard.

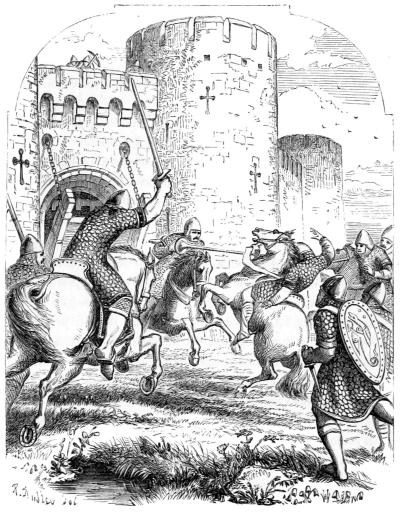

Among the nobles of Normandy, by far the haughtiest and most turbulent were the seigneurs of Bessi and Cotentin. These men were proud to excess of their Norwegian descent, and very tenacious of their Scandinavian traditions and customs. Indeed, they treated with something like contempt the conversion of the Normans to Christianity, carried pagan devices on their shields, and rode into battle with the old Scandinavian war-cry of "Thor aide!" Rejoicing, above all things, in the purity of their blood, these ancient seigneurs not only talked with ridicule of the idea of submitting to the son of Arlette, but formed a strong league, marshalled their fighting men, and prepared to display their banners and seize William's person.

When this conspiracy was formed, William had attained his seventeenth year, and, utterly unconscious of his danger, was residing in a castle unprepared for defence. The Counts of Bessi and Cotentin were making ready to mount their war-steeds and secure their prey, when one of their household fools stole away during the night, reached the castle where William was, clamoured for admittance in a loud voice, and would not be silenced till led to the young duke's presence. On getting audience of William, the fool hastily told him of his peril, and warned him to fly instantly.

"What say you?" asked William in surprise.

"I tell you," answered the fool, "that your enemies are coming, and, if you don't fly without delay, you'll be slain."

After some further questioning, William resolved to take the fool's advice, and mounting, spurred rapidly towards the Castle of Falaise. But he was imperfectly acquainted with the country; and he had not ridden far when he missed his way. William reined up his steed, and halted in perplexity and dismay; and his alarm was increased by hearing sounds as of enemies following at no great distance. Fortunately, at that moment, however, he met a peasant, who, by pointing out the way to the fugitive, and setting the pursuers off in a wrong direction, enabled the duke to reach Falaise in safety.

At that time, Henry, grandson of Hugh Capet, figured as King of France, and wore the diadem which his grandsire had torn from the head of the heirs of Charlemagne. In other days, Henry had been protected against the enmity of an imperious mother and a turbulent brother by Robert the Magnificent; and when William hastened to the French court, Henry, moved by the young duke's tale of distress, and remembering Robert's services, promised to give all the aid in his power. Ere long he redeemed his pledge by leading a French army against the insurgents. The result was the defeat of the rebel lords in a pitched battle at the "Val des Dunes," near Caen, and a victory which, for a time, gave security to Arlette's son on the ducal throne of Rollo.

William's youth was so far fortunate. His friends regarded him with idolatry; and his enemies, forced to admit that he seemed not unworthy of his position, became quiescent. The day on which he mounted his horse without placing foot in stirrup was hailed with joy; and the day on which he received knighthood was kept as a holiday throughout Normandy.

As time passed on, William showed himself very ambitious, and somewhat vindictive. He made war on his neighbours in Maine and Britanny on slender provocations, and resented without mercy any offensive allusion to his maternal parentage. One day, when he was besieging the town of Alençon, the inhabitants, to annoy him,[Pg 13] beat leather skins on the walls, in allusion to the occupation of his grandfather, and shouted, "Hides, hides!" William, in bitter rage, revenged himself by causing the hands and feet of all his prisoners to be cut off, and thrown by the slingers over the walls into the town.

But, whatever William's faults, he was loved and respected by his friends. Nor could the duke's worst enemy deny that he looked a prince of whom any people might well have been proud. In person he was scarce above the ordinary height; but so grand was his air, and so majestic his bearing, that he seemed to tower above ordinary mortals. His strength of arm was prodigious; and few were the warriors in that age who could even bend his bow. His face was sufficiently handsome to command the admiration of women, and his aspect sufficiently stern to awe men into submission to his will. No prince in Europe was more capable of producing an impression on a beholder than, at the age of twenty-five, was the warrior destined to attempt and accomplish that mighty exploit since celebrated as the Norman Conquest of England.

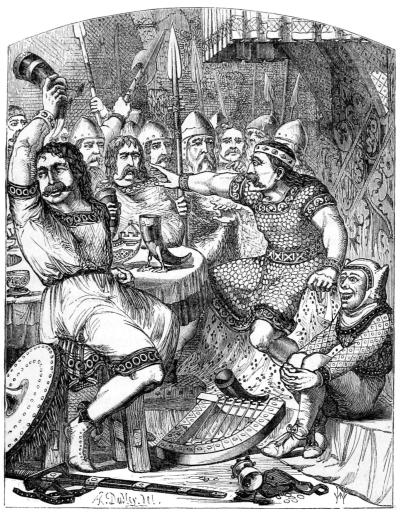

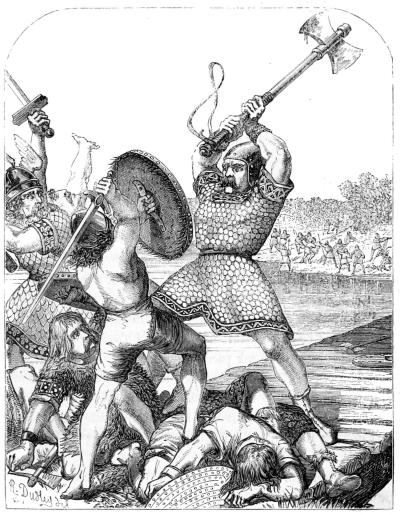

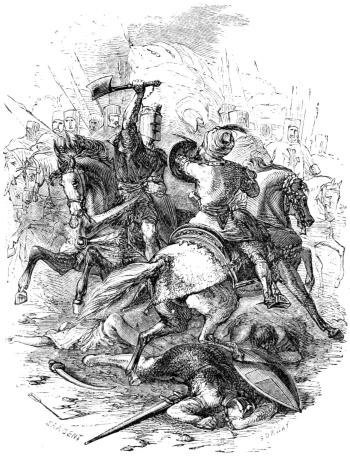

Sweyn struck by the hand of death.

THE DANES IN ENGLAND.

At the time when William the Norman was making good his claim to the Dukedom won by Rolfganger, the Saxons had been settled in England for nearly six centuries. During that long period, however, the country had frequently been exposed to the horrors of civil war[Pg 15] and to the inroads of those ruthless Northmen, who "replunged into barbarism the nations over which they swept."

It was about the year 451 that the Saxons, with huge axes on their shoulders, set foot on the shores of Britain. At that period—when the ancient Britons, left by the Roman conquerors at the mercy of the Picts and Scots, were complaining that the barbarians drove them to the sea, and that the sea drove them back to the barbarians—there anchored off the coast of Kent three bulky ships, commanded by Hengist and Horsa, two Saxon chiefs, who claimed descent from Woden, their god of war, and boasted of some military skill acquired when fighting in the ranks of Rome. From Hengist and Horsa, still worshippers of Thor and Woden, the Britons implored aid against the Picts and Scots; and the Saxon chiefs, calling over a band of their countrymen, speedily drove the painted Caledonians to their mountains and fastnesses.

After having rescued the Britons from their northern neighbours, the Saxons did not exhibit any haste to leave the country which they had delivered. Indeed, these mighty sons of Woden rather seemed ambitious of making Britain their own; and Hengist, having settled in Lincolnshire, gave a great feast. Among other guests who on this occasion came to the Saxon's stronghold was Vortigern, a King among the Britons, and, his eye being arrested and his heart inflamed by the grace and beauty of Rowena, the daughter of Hengist, while she presented the wassail-cup on bended knee, he became so desperately enamoured that he never rested till the fair and fascinating Saxon was his wife. After the marriage of Vortigern and Rowena, the Saxons plainly intimated their intention of being masters of Britain, and, the sword having been drawn, the two races—the Saxons and the Celts—commenced that struggle which lasted for more than a hundred and fifty years, during which King Arthur and the Knights of his Round Table are said to have wrought those marvellous exploits which have been celebrated by chroniclers and bards.

At length, however, the Saxons, in spite of prolonged resistance, established their supremacy, and, during the existence of the Saxon Heptarchy, which included the whole country, subject to seven[Pg 16] Princes, the conquerors of Britain became converts to Christianity, and members of the Catholic Church; and, abandoning the worship of Thor and Woden, they endeavoured to show their zeal by erecting churches and monasteries.

As time passed on, Egbert, King of Wessex, in 827 prevailed over all rivals, formed the separate provinces into a single state, and reigned as King of England. But while the Saxons were still engaged in putting down the Celts and cutting each other to pieces, a band of grim adventurers one morning sailed into the port of Teignmouth. In the discharge of his duty, a Saxon magistrate proceeded to the shore to learn whence they came and what they wanted. Without deigning an answer, the strangers slew the magistrate and his attendants, plundered the town, carried the booty to their ships, and then, hoisting their sails, took their departure. This was the first appearance in England of those Danes who were, ere long, to rend the Anglo-Saxon empire in pieces, and place their King on the English throne.

In fact, from the time of this their first visit to the English coast, the Danes were constantly finding their way to England, and signalising their inroads by every kind of barbarity. They were the most reckless of pirates and pagans, calling the ocean their home and the tempest their servant, and delighting to shed the blood of Christian priests, to desecrate churches, and to stable their steeds in chapels. In their cruel inroads, they tossed infants on the points of their spears, and mocked the idea of tears and mourning. For them, indeed, death had no terrors, for they believed themselves secure, especially if they fell in battle, of being conveyed to Valhalla; and gloried in the prospect of feasting in the halls of Odin, waited on by lovely damsels, and quaffing beer out of huge cups of horn. Settling gradually in Northumberland, East Anglia, and Mercia, the Danes occupied the whole country north of the Thames. Only one province remained to the Saxons, that of Wessex, which then extended from the mouth of the Thames to the Bristol Channel.

Such was the state of affairs when, in 871, a Saxon King, named Ethelred, was slain in a conflict with the Danes, and was succeeded by his son, Alfred, afterwards Alfred the Great, but then a youth of[Pg 17] twenty-two. At first, the courage and ability of the young King inspired the Saxons with high hopes. But Alfred, puffed up with conceit of his superior knowledge, despised those whom he governed, and his contemptuous indifference to their opinions and wishes rendered him ere long so very unpopular that when, after having reigned seven years, he was under the necessity of preparing against an inroad of the Danes, he found himself, to his mortification, almost unsupported. In vain the King, after the fashion of his ancestors, sent messengers of war to town and hamlet, bearing the arrow and naked sword, and proclaiming, "Let each man that is not a nothing leave his house and come!" So few obeyed the summons that Alfred, deeply mortified, abandoned his throne, and sought refuge in Cornwall.

It was at this dismal period that Alfred found shelter in the hut of a swineherd, and, while examining his arrows, allowed the cakes to burn. "Stupid man!" cried the swineherd's wife, unaware of his quality, "you will not take the trouble to prevent my bread from burning, though you're always so glad to eat it."

But, ere long, Alfred emerged from his obscure lurking-place, visited the Danish camp disguised as a harper, and, while entertaining the rude Northmen with music and song, became so well acquainted with the situation of affairs that he took immediate steps to restore the old Saxon nationality. Summoning fighting men of the Saxon race from every quarter, Alfred met the Danes in the field, vanquished them in eight battles, and finally reduced them to submission and obedience.

After the death of Alfred the Great, who had, after his restoration, reigned with lustre and glory, Ethelstane, pursuing Alfred's conquests, recovered York, crossed the Tweed, defeated the Danes and Cambrians at Bamborough, and brought the whole island under his dominion. For some time after Ethelstane's triumphs, the Saxons were allowed unmolestedly to sow and reap, to buy and sell, to marry and give in marriage.

In 994, however, Sweyn, King of Denmark, turned his eyes covetously towards England, where Ethelred the Unready then reigned; and forthwith, in company with Olaf, King of Norway, undertook an expedition. Despairing of opposing the invaders with success,[Pg 18] Ethelred bribed them with a large sum of money to retire, and both of them withdrew, after having sworn not again to trouble England. Nevertheless, in 1001, Sweyn, in whom the spirit of the pirate was strong, reappeared; and the Saxon King, seeing no way of getting rid of such a foe except by bribery, agreed to pay an annual tribute, to be levied throughout England under the name of "Dane-gold."

Sweyn, to whom an arrangement that was every year to replenish his treasury seemed satisfactory, returned to Denmark. Many Danes, however, remained in England, and conducted themselves with such intolerable insolence that the Saxons projected a general massacre of their unwelcome guests, and fixed on St. Brice's Day, 1002, for the execution of their hoarded vengeance. Ethelred, who, having lost his first wife, Elgira, the mother of Edmund Ironsides, had espoused Emma, sister of the Duke of Normandy, and who deemed himself secure in the alliance of the heir of Rolfganger, unhappily consented to the massacre, and, on the appointed day, the Saxons applied themselves to the work of extermination, little dreaming what would be the consequences.

No sooner did Sweyn hear of the massacre of St. Brice, than he vowed revenge, and, embarking with a mighty force, landed in England, and commenced a work of bloodshed, carnage, sacrilege, destruction, and every kind of enormity. Ethelred, after a vain attempt at resistance, fled to Normandy, with Emma his wife, and their two sons, Alfred and Edward; while Sweyn, left a victor, caused himself to be proclaimed King of England. But he did not live long to enjoy his conquests. One day, while feasting at Thetford, drinking to excess, and threatening to spoil the monastery of St. Edmund, he suddenly felt as if he had been violently struck, and the chiefs, who sat around in a circle, observed that his face underwent a rapid change.

"Oh!" exclaimed Sweyn, gasping for breath, "I have been struck by this St. Edmund with a sword!"

"Nay," said the Danish chiefs, who did not share their King's superstitious feeling, "there is no St. Edmund here."

Death, however, seemed written on Sweyn's face, and horror took possession of his soul. After suffering terrible tortures for three[Pg 19] days, he breathed his last, and left his claims and pretensions to his son Canute, who, coming victoriously out of that struggle with Edmund Ironsides, in which the royal Saxon, after repeatedly defeating the Danes, perished by the hand of an assassin, succeeded to the English throne, where he was destined to render his name memorable and his memory illustrious as Canute the Great.

It appears that, during these unfortunate struggles with the Danes, Ethelred and his son Edmund Ironsides relied much on the services of a man whom the Saxon King delighted to honour, and whom English historians have since branded as one of the most infamous traitors that ever breathed English air. This was Edric Streone, who had obtained from Ethelred the Earldom of Mercia, and who evinced his gratitude for that and countless favours by betraying his benefactor and suborning a ruffian to stab his benefactor's son.

After Ironsides' murder, Edric hastened to Canute and claimed a reward. Not unwilling, perhaps, to profit by the treachery, but abhorring the traitor, the Danish conqueror had recourse to dissimulation, and spoke to Edric in language which raised the villain's hopes.

"Depend upon it," said Canute, "I will set your head higher than any man's in the realm;" and, by way of redeeming his promise, he soon after ordered the traitor to be beheaded.

"King," cried Edric, in amazement, "remember you not your promise?"

"I do," answered Canute, with grim humour. "I promised to set your head higher than other men's, and I will keep my word." And having ordered Edric to be executed, he caused the body to be flung into the Thames, and the head to be placed high over the highest of the gates of London.

After having won considerable popularity among the Saxons by the execution of Edric Streone, Canute, who figured as King of Denmark and Norway, as well as England, endeavoured to strengthen his position by a matrimonial alliance. With this view the royal Dane wedded Emma of Normandy, the widow of Ethelred; and it was supposed that, at his death, Hardicanute, the son whom he had by this fair descendant of Rolfganger, was to succeed to the English throne.

In 1035, however, when Canute the Great went the way of all flesh, and when his remains were laid in the Cathedral of Winchester, there was living in London one of his illegitimate sons, named Harold, who, from his swiftness in running, was surnamed Harefoot. Immediately, Harold Harefoot claimed the crown, and a contest took place between his adherents and those of Hardicanute, who was then in Denmark. Harold Harefoot, however, being favoured by the Danes of London, carried the day; and finding that the Archbishop refused to perform the ceremony of coronation, he placed the crown on his head with his own hand, became an avowed enemy of the Church, lived as one "who had abjured Christianity," and displayed his contempt for religious rites by having his table served and sending out his dogs to hunt at the hour when people were assembling for worship.

After reigning four years, however, he breathed his last, and was buried at Westminster.

When Harold Harefoot died, Hardicanute was at Bruges with his mother, the Norman Emma, and he immediately sailed for England. No attempt seems to have been made to restore the Saxon line. Indeed, Hardicanute found himself received with general joy, and commenced his career as King of England by causing the body of his half-brother to be dug out of his tomb at Westminster and thrown into the Thames. Hardicanute then abandoned himself to gluttony and drunkenness, and scandalously oppressed the nation over which he swayed the sceptre. His career, however, was brief, and his end was so sudden, that some have ascribed it to foul play.

It was the 8th of June, 1041, and Hardicanute was celebrating the wedding of a Danish chief at Lambeth. Nobody expected a catastrophe, for he was still little more than twenty, and his constitution was remarkably strong. While revelling and carousing, however, he suddenly tossed up his arms and dropped on the floor a corpse. Some ascribed the death of Hardicanute to poison, but none lamented his fate; and, by the Saxons, the event was rather hailed as a sign for the restoration of the Saxon line and the heirs of Alfred.

ONE morning, at the time when Edmund Ironside and Canute were

struggling desperately for the kingdom of England, and when the son of

Ethelred had just defeated the son of Sweyn in a great battle in

Warwickshire, a Danish captain—Ulf by name—separated from his men,

and, flying to save his life, entered a wood with the paths of which

he was quite unacquainted. Halting in one of the glades, and looking

round in extreme perplexity, he felt relieved by the approach of a

young Saxon, in the garb of a herdsman, driving his father's oxen to

the pastures.

"Thy name, youth," said Ulf to the herdsman, saluting him after the fashion of his country.

"I," answered the herdsman, "am Godwin, son of Wolwoth; and thou, if I mistake not, art one of the Danes."

"It is true," said Ulf. "I have wandered about all night, and now I beg you tell me how far I am from the Danish camp, or from the ships stationed in the Severn, and by what road I can reach them."

"Mad," exclaimed Godwin, "must be the Dane who looks for safety at the hands of a Saxon."

"Nevertheless," said Ulf, "I entreat thee to leave thy herd and guide me to the camp, and I promise that thou shalt be richly rewarded."

"The way is long," said Godwin, shaking his head, "and perilous would be the attempt. The peasants, emboldened by victory, are everywhere up in arms, and little mercy would they show either to thee or thy guide."

"Accept this, youth," said the Dane, coaxingly, as he drew a gold ring from his finger.

"No," answered Godwin, after examining the jewel with curiosity, "I will not take the ring, but I will give you what aid I can."

Having thus promised his assistance to Ulf, Godwin took the Danish captain under his guidance, and led him to Wolwoth's cottage hard by, and, when night came, prepared to conduct him, by bye-paths, to the camp. They were about to depart when Wolwoth, with a tear in his eye, laid his hand in that of the Dane.

"Stranger," said the old man, "know that it is my only son who trusts to your good faith. For him there will be no safety among his countrymen from the moment he has served you as a guide. Present him, therefore, to Canute, that he may be taken into your king's service."

"Fear not, Saxon," said Ulf, "I will do more than you ask for your son. I will treat him as my own."

The Dane and Godwin then left Wolwoth's cottage, and, under the guidance of the young herdsman, the Dane reached the camp in safety. Nor was his promise forgotten. On entering his tent, Ulf seated Godwin on a seat as highly-raised as his own, and, from that hour, treated him with paternal kindness.

It was under such romantic circumstances, if we may credit ancient chroniclers and modern historians, that Godwin entered on that marvellous career which was destined to conduct him to more than regal power in England. Presented by Ulf to Canute, the son of Wolwoth soon won the favour of the Danish king; nor was he of a family whose members ever allowed any scrupulous adherence to honour to[Pg 23] stand in the way of ambitious aspirations. Indeed, he was nephew of that Edric Streone who had betrayed Ethelred the Unready, and whom Canute had found it necessary to sacrifice to the national indignation; and it has been observed that, "even as kinsman to Edric, who, whatever his crimes, must have retained a party it was wise to conciliate, Godwin's favour with Canute, whose policy would lead him to show marked distinction to any able Saxon follower, ceases to be surprising."

But, however that may have been, Godwin, protected by the king and inspired by ambition, rose rapidly to fame and fortune. Having accompanied Canute to Denmark, and afterwards signalized his military skill by a great victory over the Norwegians, he returned to England with the reputation of being, of all others, the man whom the Danish King delighted to honour. No distinction now appeared too high to be conferred on the son of Wolwoth. Ere long he began to figure as Earl of Wessex, and husband of Thyra, one of Canute's daughters.

Godwin's marriage with the daughter of Canute did not increase the Saxon Earl's popularity. Indeed, Thyra was accused of sending young Saxons as slaves to Denmark, and regarded with much antipathy. One day, however, Thyra was killed by lightning; soon after, her only son was drowned in the Thames; and Godwin lost no time in supplying the places of his lady and his heir.

Again at liberty to gratify his ambition by a royal alliance, he wedded Githa, daughter of Sweyne, Canute's successor on the throne of Denmark; and the Danish princess, as time passed on, made her husband father of six sons—Sweyne, Harold, Tostig, Gurth, Leofwine, and Wolwoth—besides two daughters—Edith and Thyra—all destined to have their names associated in history with that memorable event known as the Norman Conquest.

Meanwhile, Godwin was taking that part in national events which he hoped would raise him to still higher power among his countrymen, when Canute the Great breathed his last, and was laid at rest in the cathedral at Winchester. Then there arose a dispute about the sovereignty of England between Hardicanute and Harold Harefoot. The South declared for Hardicanute, the North for Harefoot. Both had their chances; but Harold Harefoot being in England at the[Pg 24] time, as we have seen, while Hardicanute was in Denmark, had decidedly the advantage over his rival.

Godwin, however, favouring Hardicanute, invited Queen Emma to England. He assumed the office of Protector, and received the oaths of the men of the South. But for once the son of Wolwoth found fortune adverse to his policy; and, having waited till Emma made peace with Harold Harefoot, the potent Earl also swore obedience, and allowed the claims of Hardicanute to rest.

But when time passed over, and affairs took a turn, when Harold Harefoot died, and Hardicanute, having come to England, ascended the throne, excited the national discontent by imposing excessive taxes, and was perpetually alarmed, in the midst of his debaucheries, with intelligence of tax-gatherers murdered and cities in insurrection, it became pretty clear that the Danish domination must, ere long, come to an end. Then Godwin, who had ever a keen eye to his interest, doubtless watched the signs of the times with all the vigilance demanded by the occasion, and marked well the course of events which were occurring to place the game in his hands. Accordingly, when, in the summer of 1041, Hardicanute expired so suddenly at Lambeth, while taking part in the wedding festivities of one of his Danish chiefs, Godwin perceived that the time had arrived for the restoration of Saxon royalty. With his characteristic energy, he raised his standard, and applied himself to the business. His success was even more signal than he anticipated. Indeed, if he had chosen, he might have ascended the throne of Alfred and of Canute. But his policy was to increase his own power without exciting the envy of others. With this view he assembled a great council at Gillingham. Acting by his advice, the assembled chiefs resolved on calling to the throne, not the true heir of England—the son of Edmund Ironsides, who resided in Hungary, and probably had a will of his own—but an Anglo-Saxon prince who had been long absent from England—an exile known to be inoffensive in character as well as interesting from misfortune, and with whom Godwin doubtless believed he could do whatever he pleased. At all events, it was as King-maker, and not as King, that the ennobled son of Wolwoth aspired, at this crisis, to influence the destinies of England.

While Duke William was overcoming his enemies in Normandy, and Earl Godwin was putting an end to the domination of the Danes in England, there might have been observed about the Court of Rouen a man of mild aspect and saintly habits, who had reached the age of forty. He was an exile, a Saxon prince, and one of the heirs of Alfred.

It was about the opening of the eleventh century that King Ethelred, then a widower, and father of Edmund Ironsides, espoused Emma, sister of Richard, Duke of Normandy. From this marriage sprung two sons and a daughter. The sons were named Edward and Alfred; the name of the daughter was Goda.

Edward was a native of England, and drew his first breath, in the year 1002, at Islip, near Oxford. At an early age, however, when the massacre of the Danes on the day of St. Brice resulted in the exile of Ethelred, Edward, with the other children of Ethelred and Emma, found refuge at the Court of Normandy. It was there that the youth of Edward was passed; it was there that his tastes were formed; and it was there that, brooding over the misfortunes of his country and his race, he sought consolation in those saintly theories and romantic practices which distinguished him so widely from the princes of that fierce and adventurous period which preceded the first Crusade.

When Ethelred the Unready breathed his last, in 1016, and Canute the Great demanded the widowed queen in marriage, and Emma, delighted at the prospect of still sharing the throne of England, threw herself into the arms of the royal Dane, her two sons, Edward and Alfred, remained for a time securely in Normandy. Indeed, they do not appear to have been by any means pleased at the idea of[Pg 26] their mother uniting her fate with a man whom they had regarded as their father's mortal foe. However, as years passed over, the sons of Ethelred received an invitation from Harold Harefoot to visit their native country, and they did not think fit to decline. At all events, it appears that Alfred proceeded to England, and that he went attended by a train of six hundred Normans.

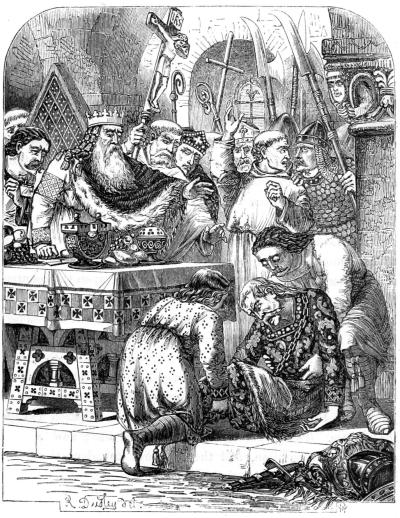

On arriving in England, Alfred was immediately invited by Harold Harefoot to come to London, and, not suspecting any snare, he hastened to present himself at court. No sooner, however, had the Saxon prince reached Guildford than he was met by Earl Godwin, conducted under some pretence into the Castle, separated from his attendants—who were massacred by hundreds—and then put in chains, to be conveyed to the Isle of Ely, where he was deprived of his sight, and so severely treated that he died of misery and pain.

Edward, who had remained in Normandy, soon learned with horror that his brother had been murdered; and when Hardicanute succeeded Harold Harefoot, he hastened to England to demand justice on Godwin. Hardicanute received his half-brother with kindness, promised that he should have satisfaction, and summoned the Earl of Wessex to answer for the murder of Prince Alfred. But Godwin's experience was great, and his craft was equal to his experience. Without scruple, he offered to swear that he was entirely guiltless of young Alfred's death, and at the same time presented Hardicanute with a magnificent galley, ornamented with gilded metal, and manned by eighty warriors, every one of whom had a gilded axe on his left shoulder, a javelin in his right hand, and bracelets on each arm. The young Danish king looked upon this gift as a most conclusive argument in favour of Godwin's innocence—and the son of Wolwoth was saved.

Edward returned to Normandy, and passed the next five years of his life in monkish austerities. But when the Danish domination came to an end, and the Grand Council was held at Gillingham, Godwin, as if to atone for consigning one of the sons of Ethelred to a tomb, hastened to place the other on a throne. Edward, then in his fortieth year, was accordingly elected king, and, on reaching England, was crowned at Winchester, in that sacred edifice where[Pg 27] his illustrious ancestors and their Danish foes reposed in peace together.

It is related by the chroniclers of this period, that when Edward, arrayed in royal robes, and accompanied by bishops and nobles, was on the point of entering the church to be crowned, a man afflicted with leprosy sat by the gate.

"What do you there?" cried the king's friends. "Move out of the way."

"Nay," said Edward, meekly, "suffer him to remain."

"King!" cried the leper, in a loud voice, "I conjure you, by the living God, to have me carried into the church, that I may pray to be made whole!"

"Unworthy should I be of heaven if I did not," Edward replied; and, stooping forward, he raised the leprous man on his back, bore him into the church, and prayed earnestly, and not in vain, for his restoration. Roger Hoveden even asserts that the king's prayers were heard, and that the leper was made whole from that hour. But, in any case, there can be no doubt that on the fierce nobles and people of his realm such a scene as this must have produced a strange impression. It was believed that Edward's sanctity gave him the power to heal; and belief in the influence which his hand was in this way supposed to have, led to the custom of English sovereigns touching for the king's evil.

In fact, however, people soon discovered that Edward was more of a monk than a monarch; and far happier would he have been if he had remained in Normandy, and sought refuge from the rude and wicked world in the quiet of a cloister. It soon appeared, moreover, that the son of Ethelred was intended to be king but in name; and that the son of Wolwoth was to be virtually sovereign of England. The plan was not unlikely to succeed. Indeed, Edward was so saintly and so simple, that Godwin might, to the hour of his death, have exercised all real power, had he not, with the vulgar ambition natural to such a man, risked everything for the chance of his posterity occupying the English throne.