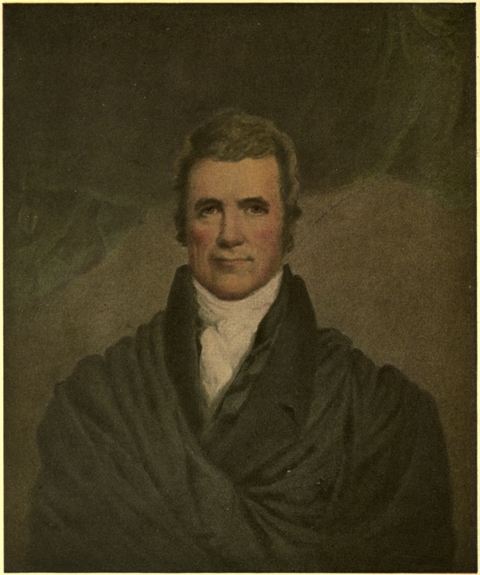

JOHN MARSHALL AS CHIEF JUSTICE

JOHN MARSHALL AS CHIEF JUSTICEFrom the portrait by Jarvis

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4), by Albert J. Beveridge This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4) Author: Albert J. Beveridge Release Date: August 3, 2012 [EBook #40389] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF JOHN MARSHALL *** Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE

COPYRIGHT, 1919, BY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| I. | INFLUENCE OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION ON AMERICA | 1 |

| The effort of the French King to injure Great Britain by assisting the revolt of the colonists hastens the upheaval in France—The French Revolution and American Government under the Constitution begins at the same time—The vital influence of the French convulsion on Americans—Impossible to understand American history without considering this fact—All Americans, at first, favor the French upheaval which they think a reform movement—Marshall's statement—American newspapers—Gouverneur Morris's description of the French people—Lafayette's infatuated reports—Marshall gets black and one-sided accounts through personal channels—The effect upon him—The fall of the Bastille—Lafayette sends Washington the key of the prison—The reign of blood in Paris applauded in America—American conservatives begin to doubt the wisdom of the French Revolution—Burke writes his "Reflections"—Paine answers with his "Rights of Man"—The younger Adams replies in the "Publicola" essays—He connects Jefferson with Paine's doctrines—"Publicola" is viciously assailed in the press—Jefferson writes Paine—The insurrection of the blacks in St. Domingo—Marshall's account—Jefferson writes his daughter: "I wish we could distribute the white exiles among the Indians"—Marshall's statement of effect of the French Revolution in America—Jefferson writes to Short: "I would rather see half the earth desolated"—Louis XVI guillotined—Genêt arrives in America—The people greet him frantically—His outrageous conduct—The Republican newspapers suppress the news of or defend the atrocities of the revolutionists—The people of Philadelphia guillotine Louis XVI in effigy—Marie Antoinette is beheaded—American rejoicing at her execution—Absurd exaggeration by both radicals and conservatives in America—The French expel Lafayette—Washington sends Marshall's brother to secure his release from the Allies—He fails—Effect upon Marshall—Ridiculous conduct of the people in America—All titles are denounced: "Honorable," "Reverend," even "Sir" or "Mr." considered "aristocratic"—The "democratic societies" appear—Washington denounces them—Their activities—Marshall's account of their decline—The influence on America of the French Revolution summarized—Marshall and Jefferson. | ||

| II. | A VIRGINIA NATIONALIST[Pg vi] | 45 |

| The National Government under the Constitution begins—Popular antagonism to it is widespread—Virginia leads this general hostility—Madison has fears—Jefferson returns from France—He is neutral at first—Madison is humiliatingly defeated for Senator of the United States because of his Nationalism—The Legislature of Virginia passes ominous Anti-Nationalist resolutions—The Republicans attack everything done or omitted by Washington's Administration—Virginia leads the opposition—Washington appoints Marshall to be United States District Attorney—Marshall declines the office—He seeks and secures election to the Legislature—Is given his old committees in the House of Delegates—Is active in the general business of the House—The amendments to the Constitution laid before the House of Delegates—They are intended only to quiet opposition to the National Government—Hamilton presents his financial plan—"The First Report on the Public Credit"—It is furiously assailed—Hamilton and Jefferson make the famous Assumption-Capitol "deal"—Jefferson's letters—The Virginia Legislature strikes Assumption—Virginia writes the Magna Charta of State Rights—Marshall desperately resists these Anti-Nationalist resolutions and is badly beaten—Jefferson finally agrees to the attitude of Virginia—He therefore opposes the act to charter the Bank of the United States—He and Hamilton give contrary opinions—The contest over "implied powers" begins—Political parties appear, divided by Nationalism and localism—Political parties not contemplated by the Constitution—The word "party" a term of reproach to our early statesmen. | ||

| III. | LEADING THE VIRGINIA FEDERALISTS | 77 |

| Marshall, in Richmond, is aggressive for the unpopular measures of Washington's Administration—danger of such conduct in Virginia—Jefferson takes Madison on their celebrated northern tour—Madison is completely changed—Jefferson fears Marshall—Wishes to get rid of him: "Make Marshall a judge"—Jefferson's unwarranted suspicions—He savagely assails the Administration of which he is a member—He comes to blows with Hamilton—The Republican Party grows—The causes for its increased strength—Pennsylvania resists the tax on whiskey—The Whiskey Rebellion—Washington denounces and Jefferson defends it—Militia ordered to suppress it—Marshall, as brigadier-general of militia, prepares to take the field—War breaks out between England and France—Washington proclaims American Neutrality—Outburst of popular wrath against him—Jefferson resigns from the Cabinet—Marshall supports Washington—At the head of the military forces he suppresses the riot at Smithfield and takes a French privateer—The Republicans in Richmond attack Mar[Pg vii]shall savagely—Marshall answers his assailants—They make insinuations against his character: the Fairfax purchase, the story of Marshall's heavy drinking—The Republicans win on their opposition to Neutrality—Great Britain becomes more hostile than ever—Washington resolves to try for a treaty in order to prevent war—Jay negotiates the famous compact bearing his name—Terrific popular resentment follows: Washington abused, Hamilton stoned, Jay burned in effigy, many of Washington's friends desert him—Toast drank in Virginia "to the speedy death of General Washington"—Jefferson assails the treaty—Hamilton writes "Camillus"—Marshall stands by Washington—Jefferson names him as the leading Federalist in Virginia. | ||

| IV. | WASHINGTON'S DEFENDER | 122 |

| Marshall becomes the chief defender of Washington in Virginia—The President urges him to accept the office of Attorney-General—He declines—Washington depends upon Marshall's judgment in Virginia politics—Vicious opposition to the Jay Treaty in Virginia—John Thompson's brilliant speech expresses popular sentiment—He couples the Jay Treaty with Neutrality: "a sullen neutrality between freemen and despots"—The Federalists elect Marshall to the Legislature—Washington is anxious over its proceedings—Carrington makes absurdly optimistic forecast—The Republicans in the Legislature attack the Jay Treaty—Marshall defends it with great adroitness—Must the new House of Representatives be consulted about treaties?—Carrington writes Washington that Marshall's argument was a demonstration—Randolph reports to Jefferson that Marshall's speech was tricky and ineffectual—Marshall defeated—Amazing attack on Washington and stout defense of him led by Marshall—Washington's friends beaten—Legislature refuses to vote that Washington has "wisdom"—Jefferson denounces Marshall: "His lax, lounging manners and profound hypocrisy"—Washington recalls Monroe from France and tenders the French mission to Marshall, who declines—The Fauchet dispatch is intercepted and Randolph is disgraced—Washington forces him to resign as Secretary of State—The President considers Marshall for the head of his Cabinet—The opposition to the Jay Treaty grows in intensity—Marshall arranges a public meeting in Richmond—The debate lasts all day—The reports as to the effect of his speeches contradictory—Marshall describes situation—The Republicans make charges and Marshall makes counter-charges—The national Federalist leaders depend on Marshall—They commission him to sound Henry on the Presidency as the successor of Washington—Washington's second Administration closes—He is savagely abused by the Republicans—The fight in the Legislature over the address to him—Marshall leads the Administration forces and is beaten—The House of Delegates refuse to vote that Washington is wise, brave, or even patriotic—Washington goes out of the [Pg viii]Presidency amid storms of popular hatred—The "Aurora's" denunciation of him—His own description of the abuse: "indecent terms that could scarcely be applied to a Nero, a defaulter, or a common pickpocket"—Jefferson is now the popular hero—All this makes a deep and permanent impression on Marshall. | ||

| V. | THE MAN AND THE LAWYER | 166 |

| An old planter refuses to employ Marshall as his lawyer because of his shabby and unimpressive appearance—He changes his mind after hearing Marshall address the court—Marshall is conscious of his superiority over other men—Wirt describes Marshall's physical appearance—He practices law as steadily as his political activities permit—He builds a fine house adjacent to those of his powerful brothers-in-law—Richmond becomes a flourishing town—Marshall is childishly negligent of his personal concerns: the Beaumarchais mortgage; but he is extreme in his solicitude for the welfare of his relatives: the letter on the love-affair of his sister; and he is very careful of the business entrusted to him by others—He is an enthusiastic Free Mason and becomes Grand Master of that order in Virginia—He has peculiar methods at the bar: cites few authorities, always closes in argument, and is notably honest with the court: "The law is correctly stated by opposing counsel"—Gustavus Schmidt describes Marshall—He is employed in the historic case of Ware vs. Hylton—His argument in the lower court so satisfactory to his clients that they select him to conduct their case in the Supreme Court of the United States—Marshall makes a tremendous and lasting impression by his effort in Philadelphia—Rufus King pays him high tribute—After twenty-four years William Wirt remembers Marshall's address and describes it—Wirt advises his son-in-law to imitate Marshall—Francis Walker Gilmer writes, from personal observation, a brilliant and accurate analysis of Marshall as lawyer and orator—The Federalist leaders at the Capital court Marshall—He has business dealings with Robert Morris—The Marshall syndicate purchases the Fairfax estate—Marshall's brother marries Hester Morris—The old financier makes desperate efforts to raise money for the Fairfax purchase—Marshall compromises with the Legislature of Virginia—His brother finally negotiates a loan in Antwerp on Morris's real estate and pays half of the contract price—Robert Morris becomes bankrupt and the burden of the Fairfax debt falls on Marshall—He is in desperate financial embarrassment—President Adams asks him to go to France as a member of the mission to that country—The offer a "God-send" to Marshall, who accepts it in order to save the Fairfax estate. | ||

| VI. | ENVOY TO FRANCE[Pg ix] | 214 |

| Marshall starts for France—Letters to his wife—Is bored by the social life of Philadelphia—His opinion of Adams—The President's opinion of Marshall—The "Aurora's" sarcasm—The reason for sending the mission—Monroe's conduct in Paris—The Republicans a French party—The French resent the Jay Treaty and retaliate by depredations on American Commerce—Pinckney, as Monroe's successor, expelled from France—President Adams's address to Congress—Marshall, Pinckney, and Gerry are sent to adjust differences between France and America—Gerry's appointment is opposed by entire Cabinet and all Federalist leaders because of their distrust of him—Adams cautions Gerry and Jefferson flatters him—Marshall arrives at The Hague—Conditions in France—Marshall's letter to his wife—His long, careful and important letter to Washington—His letter to Lee from Antwerp—Marshall and Pinckney arrive at Paris—The city—The corruption of the Government—Gerry arrives—The envoys meet Talleyrand—Description of the Foreign Minister—His opinion of America and his estimate of the envoys—Mysterious intimations. | ||

| VII. | FACING TALLEYRAND | 257 |

| Marshall urges formal representation of American grievances to French Government—Gerry opposes action—The intrigue begins—Hottenguer appears—The Directory must be "soothed" by money "placed at the disposal of M. Talleyrand"—The French demands: "pay debts due from France to American citizens, pay for French spoliations of American Commerce, and make a considerable loan and something for the pocket" (a bribe of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars)—Marshall indignantly opposes and insists on formally presenting the American case—Gerry will not agree—Bellamy comes forward and proposes still harder terms: "you must pay money, you must pay a great deal of money"—The envoys consult—Marshall and Gerry disagree—Hottenguer and Bellamy breakfast with Gerry—They again urge loan and bribe—Marshall writes Washington—His letter an able review of the state of the country—News of Bonaparte's diplomatic success at Campo Formio reaches Paris—Talleyrand's agents again descend on the envoys and demand money—"No! not a sixpence"—Marshall's bold but moderate statement—Hauteval joins Hottenguer and Bellamy—Gerry calls on Talleyrand: is not received—Talleyrand's agents hint at war—They threaten the envoys with "the French party in America"—Marshall and Pinckney declare it "degrading to carry on indirect intercourse"—Marshall again insists on written statement to Talleyrand—Gerry again objects—Marshall's letter to his wife[Pg x]—His letter in cipher to Lee—Bonaparte appears in Paris—His consummate acting—The fête at the Luxemburg to the Conqueror—Effect on Marshall. | ||

| VIII. | THE AMERICAN MEMORIAL | 290 |

| Madame de Villette—Her friendship with Marshall—Her proposals to Pinckney—Beaumarchais enters the plot—Marshall his attorney in Virginia—Bellamy suggests an arrangement between Marshall and Beaumarchais—Marshall rejects it—Gerry asks Talleyrand to dine with him—The dinner—Hottenguer in Talleyrand's presence again proposes the loan and bribe—Marshall once more insists on written statement of the American case—Gerry reluctantly consents—Marshall writes the American memorial—That great state paper—The French decrees against American commerce become harsher—Gerry holds secret conferences with Talleyrand—Marshall rebukes Gerry—Talleyrand at last receives the envoys formally—The fruitless discussion—Altercation between Marshall and Gerry—Beaumarchais comes with alarming news—Marshall again writes Washington—Washington's answer—The French Foreign Minister answers Marshall's memorial—He proposes to treat with Gerry alone—Marshall writes reply to Talleyrand—Beaumarchais makes final appeal to Marshall—Marshall replies with spirit—He sails for America. | ||

| IX. | THE TRIUMPHANT RETURN | 335 |

| Anxiety in America—Jefferson is eager for news—Skipwith writes Jefferson from Paris—Dispatches of envoys, written by Marshall, are received by the President—Adams makes alarming speech to Congress—The strength of the Republican Party increases—Republicans in House demand that dispatches be made public—Adams transmits them to Congress—Republicans are thrown into consternation and now oppose publication—Federalist Senate orders publication—Effect on Republicans in Congress—Effect on the country—Outburst of patriotism: "Hail, Columbia!" is written—Marshall arrives, unexpectedly, at New York—His dramatic welcome at Philadelphia—The Federalist banquet: Millions "for defense but not one cent for tribute"—Adams wishes to appoint Marshall Associate Justice of the Supreme Court—He declines—He is enthusiastically received at Richmond—Marshall's speech—He is insulted at the theater in Fredericksburg—Congress takes decisive action: Navy Department is created and provisional army raised—Washington accepts command—His opinions of the French—His letter to Marshall's brother—Jefferson attacks X. Y. Z. dispatches and defends Talleyrand—Alien and Sedition Laws are enacted—Gerry's predicament in France—His return—Marshall disputes Gerry's statements—Marshall's letter to his wife—He is hard pressed for [Pg xi]money—Compensation for services as envoy saves the Fairfax estate—Resolves to devote himself henceforth exclusively to his profession. | ||

| X. | CANDIDATE FOR CONGRESS | 374 |

| Plight of the Federalists in Richmond—They implore Marshall to be their candidate for Congress—He refuses—Washington personally appeals to him—Marshall finally yields—Violence of the campaign—Republicans viciously attack Marshall—the Alien and Sedition Laws the central issue—"Freeholder's" questions to Marshall—His answers—Federalists disgusted with Marshall—"The Letters of Curtius"—The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions—The philosophy of secession—Madison writes address of majority of Virginia Legislature to their constituents—Marshall writes address of the minority which Federalists circulate as campaign document—Republicans ridicule its length and verbosity—Federalists believe Republicans determined to destroy the National Government—Campaign charges against Marshall—Marshall's disgust with politics: "Nothing more debases or pollutes the human mind"—Despondent letter to his brother—On the brink of defeat—Patrick Henry saves Marshall—Riotous scenes on election day—Marshall wins by a small majority—Washington rejoices—Federalist politicians not sure of Marshall—Jefferson irritated at Marshall's election—Marshall visits his father—Jefferson thinks it a political journey: "the visit of apostle Marshall to Kentucky excites anxiety"—Naval war with France in progress—Adams sends the second mission to France—Anger of the Federalists—Republican rejoicing—Marshall supports President's policy—Adams pardons Fries—Federalists enraged, Republicans jubilant—State of parties when Marshall takes his seat in Congress. | ||

| XI. | INDEPENDENCE IN CONGRESS | 432 |

| Speaker Sedgwick's estimate of Marshall—Cabot's opinion—Marshall a leader in Congress from the first—Prepares answer of House to President's speech—It satisfies nobody—Wolcott describes Marshall—Presidential politics—Marshall writes his brother analysis of situation—Announces death of Washington, presents resolutions, and addresses House: "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen"—Marshall's activity in the House—He clashes with John Randolph of Roanoke—Debate on Slavery and Marshall's vote—He votes against his party on Sedition Law—Opposes his party's favorite measure, the Disputed Elections Bill—Forces amendment and kills the bill—Federalist resentment of his action: Speaker Sedgwick's comment on Marshall—The celebrated case of Jonathan Robins—Republicans make it principal ground of attack on Administration—The Livingston Resolution—Marshall's great speech on Executive [Pg xii]power—Gallatin admits it to be "unanswerable"—It defeats the Republicans—Jefferson's faint praise—the "Aurora's" amusing comment—Marshall defends the army and the policy of preparing for war—His speech the ablest on the Army Bill—His letter to Dabney describing conditions—Marshall helps draw the first Bankruptcy Law and, in the opinion of the Federalists, spoils it—Speaker Sedgwick vividly portrays Marshall as he appeared to the Federalist politicians at the close of the session. | ||

| XII. | CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE UNITED STATES | 485 |

| The shattering of Adams's Cabinet—Marshall declines office of Secretary of War—Offered that of Secretary of State—Adams's difficult party situation—The feud with Hamilton—Marshall finally, and with reluctance, accepts portfolio of Secretary of State—Republican comment—Federalist politicians approve: "Marshall a state conservator"—Adams leaves Marshall in charge at Washington—Examples of his routine work—His retort to the British Minister—His strong letter to Great Britain on the British debts—Controversy with Great Britain over contraband, treatment of neutrals, and impressment—Marshall's notable letter on these subjects—His harsh language to Great Britain—Federalist disintegration begins—Republicans overwhelmingly victorious in Marshall's home district—Marshall's despondent letter to Otis: "The tide of real Americanism is on the ebb"—Federalist leaders quarrel; rank and file confused and angered—Hamilton's faction plots against Adams—Adams's inept retaliation: Hamilton and his friends "a British faction"—Republican strength increases—Jefferson's platform—The second mission to France succeeds in negotiating a treaty—Chagrin of Federalists and rejoicing of Republicans—Marshall dissatisfied but favors ratification—Hamilton's amazing personal attack on Adams—The Federalists dumbfounded, the Republicans in glee—The terrible campaign of 1800—Marshall writes the President's address to Congress—The Republicans carry the election by a narrow margin—Tie between Jefferson and Burr—Federalists in House determine to elect Burr—Hamilton's frantic efforts against Burr: "The Catiline of America"—Hamilton appeals to Marshall, who favors Burr—Marshall refuses to aid Jefferson, but agrees to keep hands off—Ellsworth resigns as Chief Justice—Adams reappoints Jay, who declines—Adams then appoints Marshall, who, with hesitation, accepts—The appointment unexpected and arouses no interest—Marshall continues as Secretary of State—The dramatic contest in the House over Burr and Jefferson—Marshall accused of advising Federalists that Congress could provide for Presidency by law in case of deadlock—Federalists consider Marshall for the Presidency—Hay assails Marshall—Burr refuses Federalist proposals—The Federalist bargain with Jefferson—He is elected—The "midnight judges"—The power over the Supreme [Pg xiii]Court which Marshall was to exercise totally unsuspected by anybody—Failure of friend and foe to estimate properly his courage and determination. | ||

| APPENDIX | 565 | |

| I. List of Cases | 567 | |

| II. General Marshall's Answer to an Address of the Citizens of Richmond, Virginia | 571 | |

| III. Freeholder's Questions to General Marshall | 574 | |

| WORKS CITED IN THIS VOLUME | 579 | |

| JOHN MARSHALL AS CHIEF JUSTICE | Colored Frontispiece |

| From the portrait by John Wesley Jarvis in the possession of Mr. Roland Gray, of Boston. It represents Marshall as he was during his early years as Chief Justice and as he appeared when Representative in Congress and Secretary of State. The Jarvis portrait is by far the best likeness of Marshall during this period of his life. | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | 48 |

| From a painting by E. F. Petticolas, presented by the artist to John Marshall and now in the possession of Mr. Malcolm G. Bruce, of South Boston, Va. | |

| JOHN MARSHALL | 124 |

| From a painting by Rembrandt Peale in the rooms of the Long Island Historical Society. | |

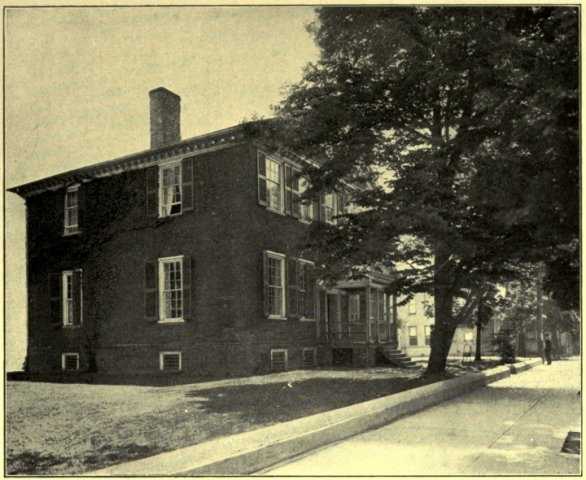

| JOHN MARSHALL'S HOUSE, RICHMOND | 172 |

| From a photograph taken especially for this book. The house was built by Marshall between 1789 and 1793. It was his second home in Richmond and the one in which he lived for more than forty years. | |

| THE LARGE ROOM WHERE THE FAMOUS "LAWYERS' DINNERS" WERE GIVEN | 172 |

| From a photograph taken especially for this book. The woodwork of the room, which is somewhat indistinct in the reproduction, is exceedingly well done. | |

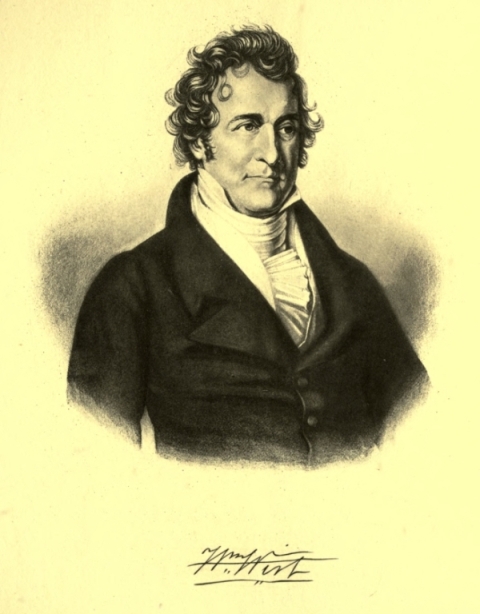

| WILLIAM WIRT | 192 |

| From an engraving by A. B. Walter, from a portrait by Charles B. King, in "Memoirs of William Wirt," by John P. Kennedy, published by Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia, 1849. Autograph from the Chamberlain collection, Boston Public Library. | |

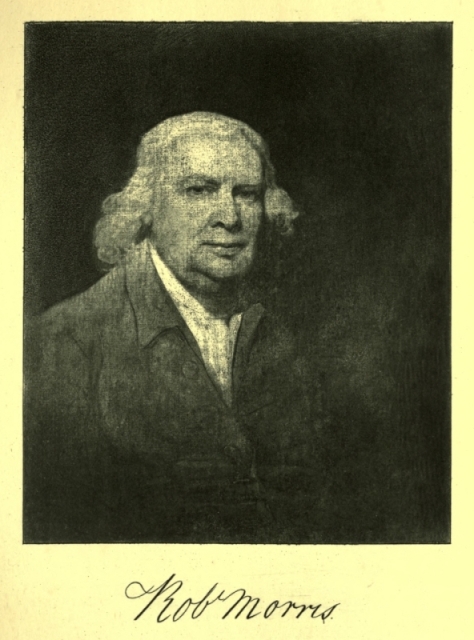

| ROBERT MORRIS | 202 |

| From an original painting by Gilbert Stuart through kind permission of the owner, C. F. M. Stark, Esq., of Winchester, Mass. Autograph from the Declaration of Independence. | |

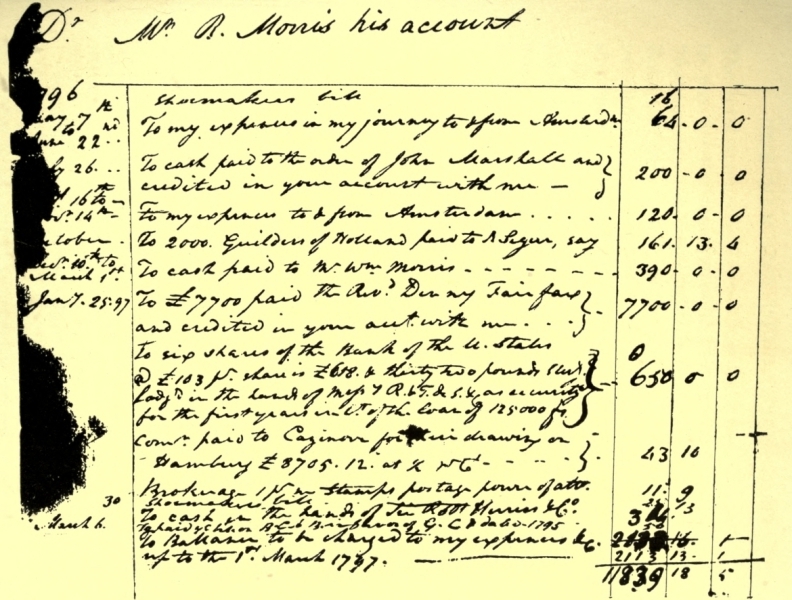

| FACSIMILE OF A PAGE OF JAMES MARSHALL'S ACCOUNT WITH ROBERT MORRIS, HIS FATHER-IN-LAW | 210 |

| From the original in the possession of James M. Marshall, of Front Royal, Virginia. This page shows £7700 sterling furnished by Robert Morris to the Marshall brothers for the purchase of the Fairfax estate. This documentary evidence of the source of the money with which the Marshalls purchased this holding has not hitherto been known to exist. | |

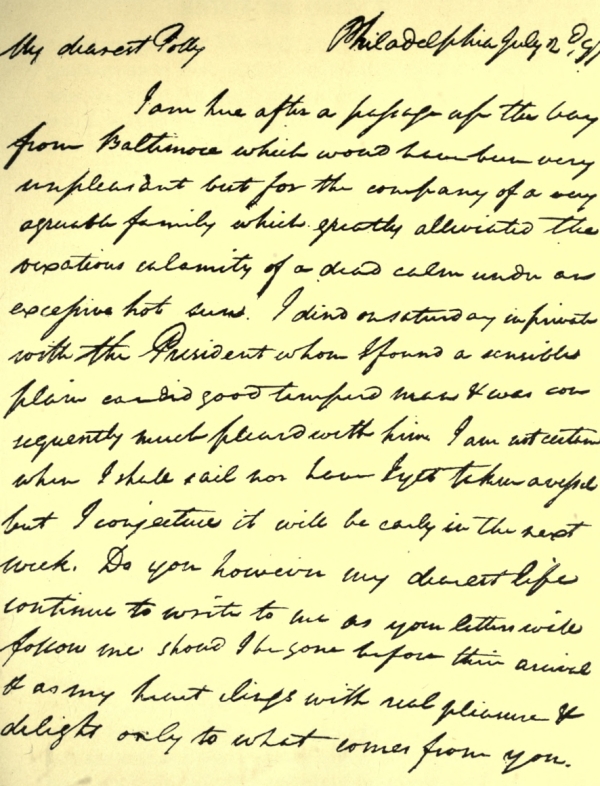

| FACSIMILE OF THE FIRST PAGE OF A LETTER FROM JOHN MARSHALL TO HIS WIFE, JULY 2, 1797[Pg xvi] | 214 |

| From the original in the possession of Miss Emily Harvie, of Richmond. The letter was written from Philadelphia immediately after Marshall's arrival at the capital when starting on his journey to France on the X. Y. Z. Mission. It is characteristic of Marshall in the fervid expressions of tender affection for his wife, whom he calls his "dearest life." It is also historically important as describing his first impression of President Adams. | |

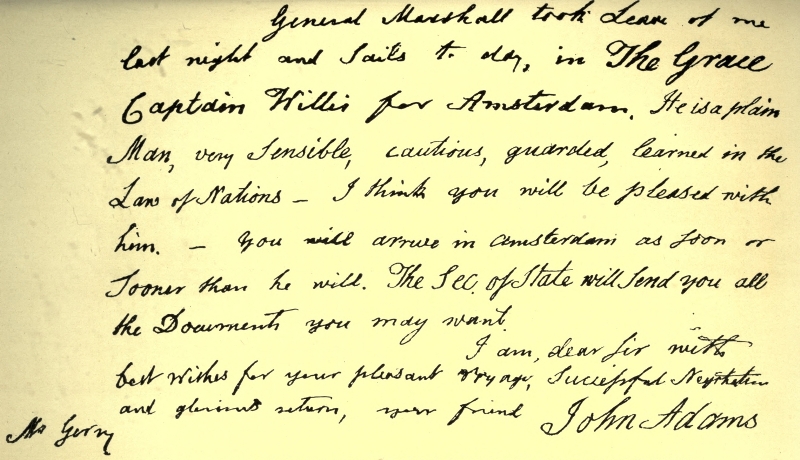

| FACSIMILE OF PART OF LETTER OF JULY 17, 1797, FROM JOHN ADAMS TO ELBRIDGE GERRY DESCRIBING JOHN MARSHALL | 228 |

| From the original in the Adams Manuscripts. President Adams writes of Marshall as he appeared to him just before he sailed for France. | |

| CHARLES MAURICE DE TALLEYRAND-PÉRIGORD | 252 |

| From an engraving by Bocourt after a drawing by Mullard, reproduced through the kindness of Mr. Charles E. Goodspeed. This portrait represents Talleyrand as he was some time after the X. Y. Z. Mission. | |

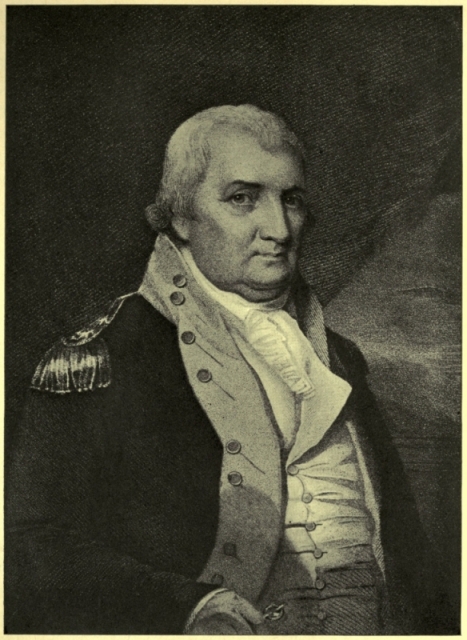

| GENERAL CHARLES COTESWORTH PINCKNEY | 274 |

| From an engraving by E. Wellmore after the miniature by Edward Greene Malbone. | |

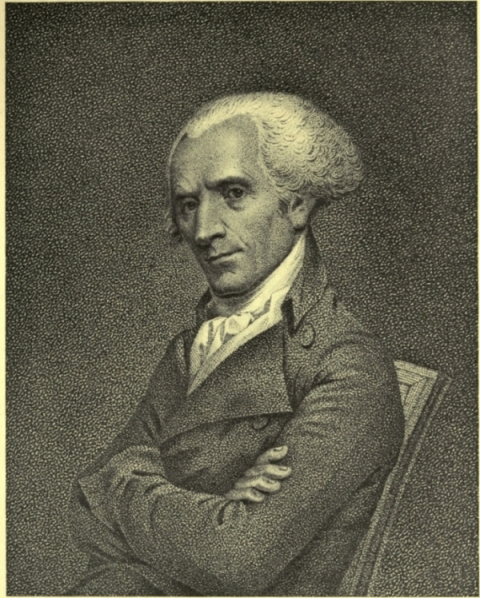

| ELBRIDGE GERRY | 310 |

| From an engraving by J. B. Longacre after a drawing made from life by Vanderlyn in 1798, when Gerry was in Paris. | |

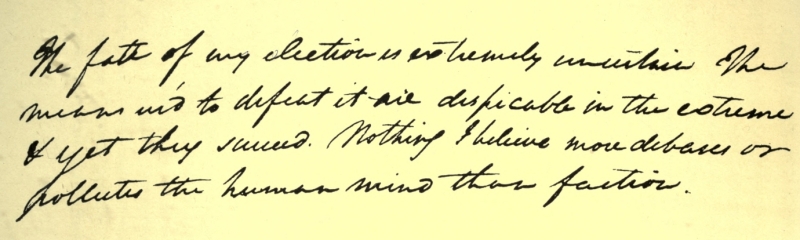

| FACSIMILE OF PART OF A LETTER FROM JOHN MARSHALL TO HIS BROTHER, DATED APRIL 3, 1799, REFERRING TO THE VIRULENCE OF THE CAMPAIGN IN WHICH MARSHALL WAS A CANDIDATE FOR CONGRESS | 410 |

| The word "faction" in this excerpt meant "party" in the vernacular of the period. | |

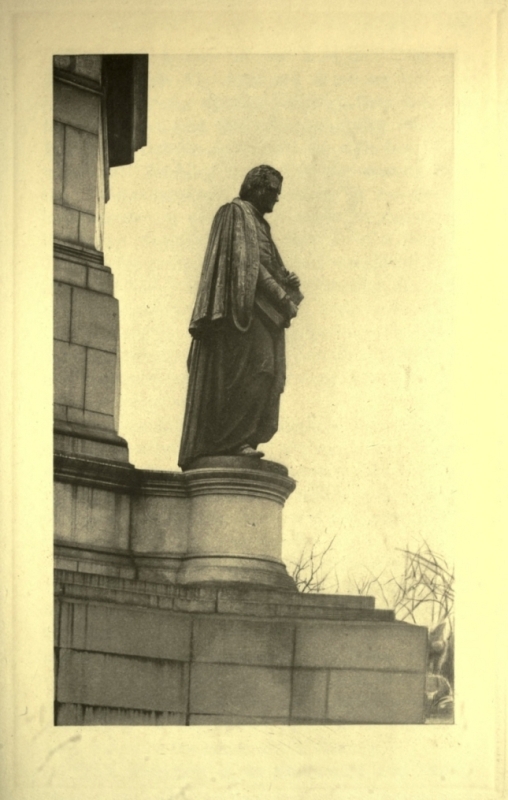

| STATUE OF JOHN MARSHALL, BY RANDOLPH ROGERS | 456 |

| This is one of six statues at the base of the Washington monument in Richmond, Va., the other figures being Jefferson, Henry, Mason, Nelson, and Lewis. The Washington Monument was designed by Thomas Crawford, who died before completing the work, and was finished by Rogers. From a photograph. | |

| STATUE OF MARSHALL, BY W. W. STORY | 530 |

| At the Capitol, Washington, D.C. From a photograph. |

All references here are to the List of Authorities at the end of this volume.

Am. St. Prs. See American State Papers.

Beard: Econ. I. C. See Beard, Charles A. Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States.

Beard: Econ. O. J. D. See Beard, Charles A. Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy.

Cor. Rev.: Sparks. See Sparks, Jared. Correspondence of the Revolution.

Cunningham Letters. See Adams, John. Correspondence with William Cunningham.

Letters: Ford. See Vans Murray, William. Letters to John Quincy Adams. Edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford.

Monroe's Writings: Hamilton. See Monroe, James. Writings. Edited by Stanislaus Murray Hamilton.

Old Family Letters. See Adams, John. Old Family Letters. Edited by Alexander Biddle.

Works: Adams. See Adams, John. Works. Edited by Charles Francis Adams.

Works: Ames. See Ames, Fisher. Works. Edited by Seth Ames.

Works: Ford. See Jefferson, Thomas. Works. Federal Edition. Edited by Paul Leicester Ford.

Works: Hamilton. See Hamilton, Alexander. Works. Edited by John C. Hamilton.

Works: Lodge. See Hamilton, Alexander. Works. Federal Edition. Edited by Henry Cabot Lodge.

Writings: Conway. See Paine, Thomas. Writings. Edited by Moncure Daniel Conway.

Writings: Ford. See Washington, George. Writings. Edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford.

Writings: Hunt. See Madison, James. Writings. Edited by Gaillard Hunt.

Writings, J. Q. A.: Ford. See Adams, John Quincy. Writings. Edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford.

Writings: Smyth. See Franklin, Benjamin. Writings. Edited by Albert Henry Smyth.

Writings: Sparks. See Washington, George. Writings. Edited by Jared Sparks.

Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than it now is. (Jefferson.)

That malignant philosophy which can coolly and deliberately pursue, through oceans of blood, abstract systems for the attainment of some fancied untried good. (Marshall.)

The only genuine liberty consists in a mean equally distant from the despotism of an individual and a million. ("Publicola": J. Q. Adams, 1792.)

The decision of the French King, Louis XVI, on the advice of his Ministers, to weaken Great Britain by aiding the Americans in their War for Independence, while it accomplished its purpose, was fatal to himself and to the Monarchy of France. As a result, Great Britain lost America, but Louis lost his head. Had not the Bourbon Government sent troops, fleets, munitions, and money to the support of the failing and desperate American fortunes, it is probable that Washington would not have prevailed; and the fires of the French holocaust which flamed throughout the world surely would not have been lit so soon.

The success of the American patriots in their armed resistance to the rule of George III, although brought about by the aid of the French Crown, was, nevertheless, the shining and dramatic example which Frenchmen imitated in beginning that vast and elemental upheaval called the French Revolu[Pg 2]tion.[1] Thus the unnatural alliance in 1778 between French Autocracy and American Liberty was one of the great and decisive events of human history.

In the same year, 1789, that the American Republic began its career under the forms of a National Government, the curtain rose in France on that tremendous drama which will forever engage the interest of mankind. And just as the American Revolution vitally influenced French opinion, so the French Revolution profoundly affected American thought; and, definitely, helped to shape those contending forces in American life that are still waging their conflict.

While the economic issue, so sharp in the adoption of the Constitution, became still keener, as will appear, after the National Government was established, it was given a higher temper in the forge of the French Revolution. American history, especially[Pg 3] of the period now under consideration, can be read correctly only by the lights that shine from that titanic smithy; can be understood only by considering the effect upon the people, the thinkers, and the statesmen of America, of the deeds done and words spoken in France during those inspiring if monstrous years.

The naturally conservative or radical temperaments of men in America were hardened by every episode of the French convulsion. The events in France, at this time, operated upon men like Hamilton on the one hand, and Jefferson on the other hand, in a fashion as deep and lasting as it was antagonistic and antipodal; and the intellectual and moral phenomena, manifested in picturesque guise among the people in America, impressed those who already were, and those who were to become, the leaders of American opinion, as much as the events of the Gallic cataclysm itself.

George Washington at the summit of his fame, and John Marshall just beginning his ascent, were alike confirmed in that non-popular tendency of thought and feeling which both avowed in the dark years between our War for Independence and the adoption of our Constitution.[2] In reviewing all the situations, not otherwise to be fully understood, that arose from the time Washington became President until Marshall took his seat as Chief Justice, we must have always before our eyes the extraordinary scenes and consider the delirious emotions which the French Revolution produced in America. It[Pg 4] must be constantly borne in mind that Americans of the period now under discussion did not and could not look upon it with present-day knowledge, perspective, or calmness. What is here set down is, therefore, an attempt to portray the effects of that volcanic eruption of human forces upon the minds and hearts of those who witnessed, from across the ocean, its flames mounting to the heavens and its lava pouring over the whole earth.

Unless this portrayal is given, a blank must be left in a recital of the development of American radical and conservative sentiment and of the formation of the first of American political parties. Certainly for the purposes of the present work, an outline, at least, of the effect of the French Revolution on American thought and feeling is indispensable. Just as the careers of Marshall and Jefferson are inseparably intertwined, and as neither can be fully understood without considering the other, so the American by-products of the French Revolution must be examined if we would comprehend either of these great protagonists of hostile theories of democratic government.

At first everybody in America heartily approved the French reform movement. Marshall describes for us this unanimous approbation. "A great revolution had commenced in that country," he writes, "the first stage of which was completed by limiting the powers of the monarch, and by the establishment of a popular assembly. In no part of the globe was this revolution hailed with more joy than in America. The influence it would have on the affairs of the world was not then distinctly[Pg 5] foreseen; and the philanthropist, without becoming a political partisan, rejoiced in the event. On this subject, therefore, but one sentiment existed."[3]

Jefferson had written from Paris, a short time before leaving for America: "A complete revolution in this [French] government, has been effected merely by the force of public opinion; ... and this revolution has not cost a single life."[4] So little did his glowing mind then understand the forces which he had helped set in motion. A little later he advises Madison of the danger threatening the reformed French Government, but adds, reassuringly, that though "the lees ... of the patriotic party [the French radical party] of wicked principles & desperate fortunes" led by Mirabeau who "is the chief ... may produce a temporary confusion ... they cannot have success ultimately. The King, the mass of the substantial people of the whole country, the army, and the influential part of the clergy, form a firm phalanx which must prevail."[5]

So, in the beginning, all American newspapers, now more numerous, were exultant. "Liberty will have another feather in her cap.... The ensuing winter [1789] will be the commencement of a Golden Age,"[6] was the glowing prophecy of an enthusiastic Boston journal. Those two sentences of the New[Pg 6] England editor accurately stated the expectation and belief of all America.

But in France itself one American had grave misgivings as to the outcome. "The materials for a revolution in this country are very indifferent. Everybody agrees that there is an utter prostration of morals; but this general position can never convey to an American mind the degree of depravity.... A hundred thousand examples are required to show the extreme rottenness.... The virtuous ... stand forward from a background deeply and darkly shaded.... From such crumbling matter ... the great edifice of freedom is to be erected here [in France].... [There is] a perfect indifference to the violation of engagements.... Inconstancy is mingled in the blood, marrow, and very essence of this people.... Consistency is a phenomenon.... The great mass of the common people have ... no morals but their interest. These are the creatures who, led by drunken curates, are now in the high road à la liberté."[7] Such was the report sent to Washington by Gouverneur Morris, the first American Minister to France under the Constitution.

Three months later Morris, writing officially, declares that "this country is ... as near to anarchy as society can approach without dissolution."[8] And yet, a year earlier, Lafayette had lamented the[Pg 7] French public's indifference to much needed reforms; "The people ... have been so dull that it has made me sick" was Lafayette's doleful account of popular enthusiasm for liberty in the France of 1788.[9]

Gouverneur Morris wrote Robert Morris that a French owner of a quarry demanded damages because so many bodies had been dumped into the quarry that they "choked it up so that he could not get men to work at it." These victims, declared the American Minister, had been "the best people," killed "without form of trial, and their bodies thrown like dead dogs into the first hole that offered."[10] Gouverneur Morris's diary abounds in such entries as "[Sept. 2, 1792] the murder of the priests, ... murder of prisoners,... [Sept. 3] The murdering continues all day.... [Sept. 4th].... And still the murders continue."[11]

John Marshall was now the attorney of Robert[Pg 8] Morris; was closely connected with him in business transactions; and, as will appear, was soon to become his relative by the marriage of Marshall's brother to the daughter of the Philadelphia financier. Gouverneur Morris, while not related to Robert Morris, was "entirely devoted" to and closely associated with him in business; and both were in perfect agreement of opinions.[12] Thus the reports of the scarlet and revolting phases of the French Revolution that came to the Virginia lawyer were carried through channels peculiarly personal and intimate.

They came, too, from an observer who was thoroughly aristocratic in temperament and conviction.[13] Little of appreciation or understanding of the basic causes and high purposes of the French Revolution appears in Gouverneur Morris's accounts and comments, while he portrays the horrible in unrelieved ghastliness.[14]

Such, then, were the direct and first-hand accounts that Marshall received; and the impression made upon him was correspondingly dark, and as lasting as it was somber. Of this, Marshall himself leaves us in no doubt. Writing more than a decade later he gives his estimate of Gouverneur Morris and of his accounts of the French Revolution.[Pg 9]

"The private correspondence of Mr. Morris with the president [and, of course, much more so with Robert Morris] exhibits a faithful picture, drawn by the hand of a master, of the shifting revolutionary scenes which with unparalleled rapidity succeeded each other in Paris. With the eye of an intelligent, and of an unimpassioned observer, he marked all passing events, and communicated them with fidelity. He did not mistake despotism for freedom, because it was sanguinary, because it was exercised by those who denominated themselves the people, or because it assumed the name of liberty. Sincerely wishing happiness and a really free government to France, he could not be blind to the obvious truth that the road to those blessings had been mistaken."[15]

Everybody in America echoed the shouts of the Parisian populace when the Bastille fell. Was it not the prison where kings thrust their subjects to perish of starvation and torture?[16] Lafayette, "as a missionary of liberty to its patriarch," hastened to present Washington with "the main key of the[Pg 10] fortress of despotism."[17] Washington responded that he accepted the key of the Bastille as "a token of the victory gained by liberty."[18] Thomas Paine wrote of his delight at having been chosen by Lafayette to "convey ... the first ripe fruits of American principles, transplanted into Europe, to his master and patron."[19] Mutual congratulations were carried back and forth by every ship.

Soon the mob in Paris took more sanguinary action and blood flowed more freely, but not in sufficient quantity to quench American enthusiasm for the cause of liberty in France. We had had plenty of mobs ourselves and much crimson experience. Had not mobs been the precursors of our own Revolution?

The next developments of the French uprising and the appearance of the Jacobin Clubs, however, alarmed some and gave pause to all of the cautious friends of freedom in America and other countries.

Edmund Burke hysterically sounded the alarm. On account of his championship of the cause of American Independence, Burke had enjoyed much credit with all Americans who had heard of him. "In the last age," exclaimed Burke in Parliament, February 9, 1790, "we were in danger of being entangled by the example of France in the net of a relentless despotism.... Our present danger from[Pg 11] the example of a people whose character knows no medium, is, with regard to government, a danger from anarchy; a danger of being led, through an admiration of successful fraud and violence, to an imitation of the excesses of an irrational, unprincipled, proscribing, confiscating, plundering, ferocious, bloody, and tyrannical democracy."[20]

Of the French declaration of human rights Burke declared: "They made and recorded a sort of institute and digest of anarchy, called the rights of man, in such a pedantic abuse of elementary principles as would have disgraced boys at school.... They systematically destroyed every hold of authority by opinion, religious or civil, on the minds of the people.[21]... On the scheme of this barbarous philosophy, which is the offspring of cold hearts and muddy understandings," exclaimed the great English liberal, "laws are to be supported only by their own terrours.... In the groves of their academy, at the end of every vista, you see nothing but the gallows."[22]

Burke's extravagant rhetoric, although reprinted in America, was little heeded. It would have been better if his pen had remained idle. For Burke's wild language, not yet justified by the orgy of blood[Pg 12] in which French liberty was, later, to be baptized, caused a voice to speak to which America did listen, a page to be written that America did read. Thomas Paine, whose "Common Sense" had made his name better known to all people in the United States than that of any other man of his time except Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, and Henry, was then in France. This stormy petrel of revolution seems always to have been drawn by instinct to every part of the human ocean where hurricanes were brooding.[23]

Paine answered Burke with that ferocious indictment of monarchy entitled "The Rights of Man," in which he went as far to one extreme as the English political philosopher had gone to the other; for while Paine annihilated Burke's Brahminic laudation of rank, title, and custom, he also penned a doctrine of paralysis to all government. As was the case with his "Common Sense," Paine's "Rights of Man" abounded in attractive epigrams and striking sentences which quickly caught the popular ear and were easily retained by the shallowest memory.

"The cause of the French people is that of ... the whole world," declared Paine in the preface of his flaming essay;[24] and then, the sparks beginning to fly from his pen, he wrote: "Great part of that order which reigns among mankind is not the effect of government.... It existed prior to government, and would exist if the formality of government was[Pg 13] abolished.... The instant formal government is abolished," said he, "society begins to act; ... and common interest produces common security." And again: "The more perfect civilization is, the less occasion has it for government.... It is but few general laws that civilised life requires."

Holding up our own struggle for liberty as an illustration, Paine declared: "The American Revolution ... laid open the imposition of governments"; and, using our newly formed and untried National Government as an example, he asserted with grotesque inaccuracy: "In America ... all the parts are brought into cordial unison. There the poor are not oppressed, the rich are not privileged.... Their taxes are few, because their government is just."[25]

Proceeding thence to his assault upon all other established governments, especially that of England, the great iconoclast exclaimed: "It is impossible that such governments as have hitherto [1790] existed in the world, could have commenced by any other means than a violation of every principle sacred and moral."

Striking at the foundations of all permanent authority, Paine declared that "Every age and generation must be ... free to act for itself in all cases.... The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies." The people of yesterday have "no right ... to bind or to control ... the people of the present day ... in any shape whatever....[Pg 14] Every generation is, and must be, competent to all the purposes which its occasions require."[26] So wrote the incomparable pamphleteer of radicalism.

Paine's essay, issued in two parts, was a torch successively applied to the inflammable emotions of the American masses. Most newspapers printed in each issue short and appealing excerpts from it. For example, the following sentence from Paine's "Rights of Man" was reproduced in the "Columbian Centinel" of Boston on June 6, 1792: "Can we possibly suppose that if government had originated in right principles and had not an interest in pursuing a wrong one, that the world could have been in the wretched and quarrelsome condition it is?" Such quotations from Paine appeared in all radical and in some conservative American publications; and they were repeated from mouth to mouth until even the backwoodsmen knew of them—and believed them.

"Our people ... love what you write and read it with delight" ran the message which Jefferson sent across the ocean to Paine. "The printers," continued Jefferson, "season every newspaper with extracts from your last, as they did before from your first part of the Rights of Man. They have both served here to separate the wheat from the chaff.... Would you believe it possible that in this country there should be high & important characters[27] who need your lessons in republicanism & who do not heed them. It is but too true that we have a sect preaching up & pouting after an English constitu[Pg 15]tion of king, lords, & commons, & whose heads are itching for crowns, coronets & mitres....

"Go on then," Jefferson urged Paine, "in doing with your pen what in other times was done with the sword, ... and be assured that it has not a more sincere votary nor you a more ardent well-wisher than ... Thoṣ Jefferson."[28]

And the wheat was being separated from the chaff, as Jefferson declared. Shocked not more by the increasing violence in France than by the principles which Paine announced, men of moderate mind and conservative temperament in America came to have misgivings about the French Revolution, and began to speak out against its doings and its doctrines.

A series of closely reasoned and well-written articles were printed in the "Columbian Centinel" of Boston in the summer of 1791, over the nom de guerre "Publicola"; and these were widely copied. They were ascribed to the pen of John Adams, but were the work of his brilliant son.[29][Pg 16]

The American edition of Paine's "Rights of Man" was headed by a letter from Secretary of State Jefferson to the printer, stating his pleasure that the essay was to be printed in this country and "that something is at length to be publickly said against the political heresies which have sprung up among us."[30] Publicola called attention to this and thus, more conspicuously, displayed Jefferson as an advocate of Paine's doctrines.[31]

All Americans had "seen with pleasure the temples of despotism levelled with the ground," wrote the keen young Boston law student.[32] There was "but one sentiment...—that of exultation." But what did Jefferson mean by "heresies"? asked Publicola. Was Paine's pamphlet "the canonical book of scripture?" If so, what were its doctrines? "That[Pg 17] which a whole nation chooses to do, it has a right to do" was one of them.

Was that "principle" sound? No! avowed Publicola, for "the eternal and immutable laws of justice and of morality are paramount to all human legislation." A nation might have the power but never the right to violate these. Even majorities have no right to do as they please; if so, what security has the individual citizen? Under the unrestrained rule of the majority "the principles of liberty must still be the sport of arbitrary power, and the hideous form of despotism must lay aside the diadem and the scepter, only to assume the party-colored garments of democracy."

"The only genuine liberty consists in a mean equally distant from the despotism of an individual and of a million," asserted Publicola. "Mr. Paine seems to think it as easy for a nation to change its government as for a man to change his coat." But "the extreme difficulty which impeded the progress of its [the American Constitution's] adoption ... exhibits the fullest evidence of what a more than Herculean task it is to unite the opinions of a free people on any system of government whatever."

The "mob" which Paine exalted as the common people, but which Publicola thought was really only the rabble of the cities, "can be brought to act in concert" only by "a frantic enthusiasm and ungovernable fury; their profound ignorance and deplorable credulity make them proper tools for any man who can inflame their passions; ... and," warned Publicola, "as they have nothing to lose by the total[Pg 18] dissolution of civil society, their rage may be easily directed against any victim which may be pointed out to them.... To set in motion this inert mass, the eccentric vivacity of a madman is infinitely better calculated than the sober coolness of phlegmatic reason."

"Where," asked Publicola, "is the power that should control them [Congress]?" if they violate the letter of the Constitution. Replying to his own question, he asserted that the real check on Congress "is the spirit of the people."[33] John Marshall had said the same thing in the Virginia Constitutional Convention; but even at that early period the Richmond attorney went further and flatly declared that the temporary "spirit of the people" was not infallible and that the Supreme Court could and would declare void an unconstitutional act of Congress—a truth which he was, unguessed at that time by himself or anybody else, to announce with conclusive power within a few years and at an hour when dissolution confronted the forming Nation.

Such is a rapid précis of the conservative essays written by the younger Adams. Taken together, they were a rallying cry to those who dared to brave the rising hurricane of American sympathy with the French Revolution; but they also strengthened the force of that growing storm. Multitudes of writers attacked Publicola as the advocate of "aristocracy" and "monarchy." "The papers under the signature of Publicola have called forth[Pg 19] a torrent of abuse," declared the final essay of the series.

Brown's "Federal Gazette" of Philadelphia branded Publicola's doctrines as "abominable heresies"; and hoped that they would "not procure many proselytes either to monarchy or aristocracy."[34] The "Independent Chronicle" of Boston asserted that Publicola was trying to build up a "system of Monarchy and Aristocracy ... on the ruins both of the Reputation and Liberties of the People."[35] Madison reported to Jefferson that because of John Adams's reputed authorship of these unpopular letters, the supporters of the Massachusetts statesman had become "perfectly insignificant in ... number" and that "in Boston he is ... distinguished for his unpopularity."[36]

In such fashion the controversy began in America over the French Revolution.

But whatever the misgivings of the conservative, whatever the alarm of the timid, the overwhelming majority of Americans were for the French Revolution and its doctrines;[37] and men of the highest ability and station gave dignity to the voice of the people.[Pg 20]

In most parts of the country politicians who sought election to public office conformed, as usual, to the popular view. It would appear that the prevailing sentiment was influential even with so strong a conservative and extreme a Nationalist as Madison, in bringing about his amazing reversal of views which occurred soon after the Constitution was adopted.[38] But those who, like Marshall, were not shaken, were made firmer in their opinions by the very strength of the ideas thus making headway among the masses.

An incident of the French Revolution almost within sight of the American coast gave to the dogma of equality a new and intimate meaning in the eyes of those who had begun to look with disfavor upon the results of Gallic radical thought. Marshall and Jefferson best set forth the opposite impressions made by this dramatic event.

"Early and bitter fruits of that malignant philosophy," writes Marshall, "which ... can coolly[Pg 21] and deliberately pursue, through oceans of blood, abstract systems for the attainment of some fancied untried good, were gathered in the French West Indies.... The revolutionists of France formed the mad and wicked project of spreading their doctrines of equality among persons [negroes and white people] between whom distinctions and prejudices exist to be subdued only by the grave. The rage excited by the pursuit of this visionary and baneful theory, after many threatening symptoms, burst forth on the 23d day of August 1791, with a fury alike destructive and general.

"In one night, a preconcerted insurrection of the blacks took place throughout the colony of St. Domingo; and the white inhabitants of the country, while sleeping in their beds, were involved in one indiscriminate massacre, from which neither age nor sex could afford an exemption. Only a few females, reserved for a fate more cruel than death, were intentionally spared; and not many were fortunate enough to escape into the fortified cities. The insurgents then assembled in vast numbers, and a bloody war commenced between them and the whites inhabiting the towns."[39]

After the African disciples of French liberty had overthrown white supremacy in St. Domingo, Jefferson wrote his daughter that he had been informed "that the Patriotic party [St. Domingo revolutionists] had taken possession of 600 aristocrats & monocrats, had sent 200 of them to France, & were sending 400 here.... I wish," avowed Jef[Pg 22]ferson, in this intimate family letter, "we could distribute our 400 [white French exiles] among the Indians, who would teach them lessons of liberty & equality."[40]

Events in France marched swiftly from one bloody climax to another still more scarlet. All were faithfully reflected in the views of the people of the United States. John Marshall records for us "the fervour of democracy" as it then appeared in our infant Republic. He repeats that, at first, every American wished success to the French reformers. But the later steps of the movement "impaired this ... unanimity of opinion.... A few who had thought deeply on the science of government ... believed that ... the influence of the galleries over the legislature, and of mobs over the executive; ... the tumultuous assemblages of the people and their licentious excesses ... did not appear to be the symptoms of a healthy constitution, or of genuine freedom.... They doubted, and they feared for the future."

Of the body of American public opinion, however, Marshall chronicles that: "In total opposition to this sentiment was that of the public. There seems to be something infectious in the example of a powerful and enlightened nation verging towards democracy, which imposes on the human mind, and leads human reason in fetters.... Long settled opinions yield to the overwhelming weight of such dazzling authority. It wears the semblance of be[Pg 23]ing the sense of mankind, breaking loose from the shackles which had been imposed by artifice, and asserting the freedom, and the dignity, of his nature."

American conservative writers, says Marshall, "were branded as the advocates of royalty, and of aristocracy. To question the duration of the present order of things [in France] was thought to evidence an attachment to unlimited monarchy, or a blind prejudice in favour of British institutions.... The war in which the several potentates of Europe were engaged against France, although in almost every instance declared by that power, was pronounced to be a war for the extirpation of human liberty, and for the banishment of free government from the face of the earth. The preservation of the constitution of the United States was supposed to depend on its issue; and the coalition against France was treated as a coalition against America also."[41]

Marshall states, more clearly, perhaps, than any one else, American conservative opinion of the time: "The circumstances under which the abolition of royalty was declared, the massacres which preceded it, the scenes of turbulence and violence which were acted in every part of the nation, appeared to them [American conservatives] to present an awful and doubtful state of things.... The idea that a republic was to be introduced and supported by force, was, to them, a paradox in politics."

Thus it was, he declares, that "the French revolution will be found to have had great influence[Pg 24] on the strength of parties, and on the subsequent political transactions of the United States."[42]

As the French storm increased, its winds blew ever stronger over the responsive waters of American opinion. Jefferson, that accurate barometer of public weather, thus registers the popular feeling: "The sensations it [the French Revolution] has produced here, and the indications of them in the public papers, have shown that the form our own government was to take depended much more on the events of France than anybody had before imagined."[43] Thus both Marshall and Jefferson bear testimony as to the determining effect produced in America by the violent change of systems in France.

William Short, whom Jefferson had taken to France as his secretary, when he was the American Minister to France, and who, when Jefferson returned to the United States, remained as chargé d'affaires,[44] had written both officially and privately of what was going on in France and of the increasing dominance of the Jacobin Clubs.[45] Perhaps no[Pg 25] more trustworthy statement exists of the prevailing American view of the French cataclysm than that given in Jefferson's fatherly letter to his protégé:—

"The tone of your letters had for some time given me pain," wrote Jefferson, "on account of the extreme warmth with which they censured the proceedings of the Jacobins of France.[46]... Many guilty persons [aristocrats] fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent:... It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine[Pg 26] not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree....

"The liberty of the whole earth," continued Jefferson, "was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated.

"Were there but an Adam & an Eve left in every country, & left free, it would be better than as it now is," declared Jefferson; and "my sentiments ... are really those of 99 in an hundred of our citizens," was that careful political observer's estimate of American public opinion. "Your temper of mind," Jefferson cautions Short, "would be extremely disrelished if known to your countrymen.

"There are in the U.S. some characters of opposite principles.... Excepting them, this country is entirely republican, friends to the constitution.... The little party above mentioned have espoused it only as a stepping stone to monarchy.... The successes of republicanism in France have given the coup de grace to their prospects, and I hope to their projects.

"I have developed to you faithfully the sentiments of your country," Jefferson admonishes Short, "that you may govern yourself accordingly."[47][Pg 27]

Jefferson's count of the public pulse was accurate. "The people of this country [Virginia] ... are unanimous & explicit in their sympathy with the Revolution" was the weather-wise Madison's report.[48] And the fever was almost as high in other States.

When, after many executions of persons who had been "denounced" on mere suspicion of unfriendliness to the new order of things, the neck of Louis XVI was finally laid beneath the knife of the guillotine and the royal head rolled into the executioner's basket, even Thomas Paine was shocked. In a judicious letter to Danton he said:—

"I now despair of seeing the great object of European liberty accomplished" because of "the tumultuous misconduct" of "the present revolution" which "injure[s its] character ... and discourage[s] the progress of liberty all over the world.... There ought to be some regulation with respect to the spirit of denunciation that now prevails."[49]

So it was that Thomas Paine, in France, came to speak privately the language which, in America, at that very hour, was considered by his disciples to be the speech of "aristocracy," "monarchy," and[Pg 28] "despotism"; for the red fountains which drenched the fires of even Thomas Paine's enthusiasm did not extinguish the flames his burning words had lighted among the people of the United States. Indeed Paine, himself, was attacked for regretting the execution of the King.[50]

Three months after the execution of the French King, the new Minister of the French Republic, "Citizen" Genêt, arrived upon our shores. He landed, not at Philadelphia, then our seat of government, but at Charleston, South Carolina. The youthful[51] representative of Revolutionary France was received by public officials with obsequious flattery and by the populace with a frenzy of enthusiasm almost indescribable in its intensity.

He acted on the welcome. He fitted out privateers, engaged seamen, issued letters of marque and reprisal, administered to American citizens oaths of "allegiance" to the authority then reigning in Paris. All this was done long before he presented his credentials to the American Government. His progress to our Capital was an unbroken festival of triumph. Washington's dignified restraint was interpreted as hostility, not only to Genêt, but also to "liberty." But if Washington's heart was ice, the people's heart was fire.

"We expect Mr. Genest here within a few days,"[Pg 29] wrote Jefferson, just previous to the appearance of the French Minister in Philadelphia and before our ignored and offended President had even an opportunity to receive him. "It seems," Jefferson continued, "as if his arrival would furnish occasion for the people to testify their affections without respect to the cold caution of their government."[52]

Again Jefferson measured popular sentiment accurately. Genêt was made an idol by the people. Banquets were given in his honor and extravagant toasts were drunk to the Republic and the guillotine. Showers of fiery "poems" filled the literary air.[53] "What hugging and tugging! What addressing and caressing! What mountebanking and chanting! with liberty caps and other wretched trumpery of sans culotte foolery!" exclaimed a disgusted conservative.[54]

While all this was going on in America, Robespierre, as the incarnation of liberty, equality, and fraternity in France, achieved the summit of power and "The Terror" reached high tide. Marie Antoinette met the fate of her royal husband, and the executioners, overworked, could not satisfy the lust of the Parisian populace for human life. All this, however, did not extinguish American enthusiasm for French liberty.

Responding to the wishes of their subscribers, who at that period were the only support of the press, the Republican newspapers suppressed such atrocities as they could, but when concealment was impossible,[Pg 30] they defended the deeds they chronicled.[55] It was a losing game to do otherwise, as one of the few journalistic supporters of the American Government discovered to his sorrow. Fenno, the editor of the "Gazette of the United States," found opposition to French revolutionary ideas, in addition to his support of Hamilton's popularly detested financial measures,[56] too much for him. The latter was load enough; but the former was the straw that broke the conservative editor's back.

"I am ... incapacitate[d] ... from printing another paper without the aid of a considerable loan," wrote the bankrupt newspaper opponent of French doctrines and advocate of Washington's Administration. "Since the 18th September, [1793] I have rec'd only 35¼ dollars," Fenno lamented. "Four years & an half of my life is gone for nothing; & worse (for I have a Debt of 2500 Dollars on my Shoulders), if at this crisis the hand of benevolence & patriotism is not extended."[57][Pg 31]

Forgotten by the majority of Americans was the assistance which the demolished French Monarchy and the decapitated French King had given the American army when, but for that assistance, our cause had been lost. The effigy of Louis XVI was guillotined by the people, many times every day in Philadelphia, on the same spot where, ten years before, as a monument of their gratitude, these same patriots had erected a triumphal arch, decorated with the royal lilies of France bearing the motto, "They exceed in glory," surmounted by a bust of Louis inscribed, "His merit makes us remember him."[58]

At a dinner in Philadelphia upon the anniversary of the French King's execution, the dead monarch was represented by a roasted pig. Its head was cut off at the table, and each guest, donning the liberty cap, shouted "tyrant" as with his knife he chopped the sundered head of the dead swine.[59] The news of the beheading of Louis's royal consort met with a like reception. "I have heard more than one young woman under the age of twenty declare," testifies Cobbett, "that they would willingly have dipped their hands in the blood of the queen of France."[60][Pg 32]

But if the host of American radicals whom Jefferson led and whose spirit he so truly interpreted were forgetful of the practical friendship of French Royalty in our hour of need, American conservatives, among whom Marshall was developing leadership, were also unmindful of the dark crimes against the people which, at an earlier period, had stained the Monarchy of France and gradually cast up the account that brought on the inevitable settlement of the Revolution. The streams of blood that flowed were waters of Lethe to both sides.

Yet to both they were draughts which produced in one an obsession of reckless unrestraint and in the other a terror of popular rule no less exaggerated.[61] Of the latter class, Marshall was, by far, the most moderate and balanced, although the tragic aspect of the convulsion in which French liberty was born, came to him in an especially direct fashion, as we have seen from the Morris correspondence already cited.

Another similar influence on Marshall was the case of Lafayette. The American partisans of the French Revolution accused this man, who had fought for[Pg 33] us in our War for Independence, of deserting the cause of liberty because he had striven to hold the Gallic uprising within orderly bounds. When, for this, he had been driven from his native land and thrown into a foreign dungeon, Freneau thus sang the conviction of the American majority:—

"Here, bold in arms, and firm in heart,

He help'd to gain our cause,

Yet could not from a tyrant part,

But, turn'd to embrace his laws!"[62]

Lafayette's expulsion by his fellow Republicans and his imprisonment by the allied monarchs, was brought home to John Marshall in a very direct and human fashion. His brother, James M. Marshall, was sent by Washington[63] as his personal representative, to plead unofficially for Lafayette's release. Marshall tells us of the strong and tender personal friendship between Washington and Lafayette and of the former's anxiety for the latter. But, writes Marshall: "The extreme jealousy with which the persons who administered the government of France, as well as a large party in America, watched his [Washington's] deportment towards all those whom the ferocious despotism of the jacobins had exiled from their country" rendered "a formal interposition in favour of the virtuous and unfortunate victim [Lafayette] of their furious passions ... unavailing."

Washington instructed our ministers to do all they could "unofficially" to help Lafayette, says Marshall; and "a confidential person [Marshall's brother[Pg 34] James] had been sent to Berlin to solicit his discharge: but before this messenger had reached his destination, the King of Prussia had delivered over his illustrious prisoner to the Emperor of Germany."[64] Washington tried "to obtain the powerful mediation of Britain" and hoped "that the cabinet of St. James would take an interest in the case; but this hope was soon dissipated." Great Britain would do nothing to secure from her allies Lafayette's release.[65]

Thus Marshall, in an uncommonly personal way, was brought face to face with what appeared to him to be the injustice of the French revolutionists. Lafayette, under whom John Marshall had served at Brandywine and Monmouth; Lafayette, leader of the movement in France for a free government like our own; Lafayette, hated by kings and aristocrats because he loved genuine liberty, and yet exiled from his own country by his own countrymen for the same reason[66]—this picture, which was the one Marshall saw, influenced him profoundly and permanently.

Humor as well as horror contributed to the repugnance which Marshall and men of his type felt ever more strongly for what they considered to be mere popular caprice. The American passion for equality had its comic side. The public hatred of all[Pg 35] rank did not stop with French royalty and nobility. Because of his impassioned plea in Parliament for the American cause, a statue of Lord Chatham had been erected at Charleston, South Carolina; the people now suspended it by the neck in the air until the sculptured head was severed from the body. But Chatham was dead and knew only from the spirit world of this recognition of his bold words in behalf of the American people in their hour of trial and of need. In Virginia the statue of Lord Botetourt was beheaded.[67] This nobleman was also long since deceased, guilty of no fault but an effort to help the colonists, more earnest than some other royal governors had displayed. Still, in life, he had been called a "lord"; so off with the head of his statue!

In the cities, streets were renamed. "Royal Exchange Alley" in Boston became "Equality Lane"; and "Liberty Stump" was the name now given to the base of a tree that formerly had been called "Royal." In New York, "Queen Street became Pearl Street; and King Street, Liberty Street."[68] The liberty cap was the popular headgear and everybody wore the French cockade. Even the children, thus decorated, marched in processions,[69] singing, in a mixture of French and English words, the meaning[Pg 36] of which they did not in the least understand, the glories of "liberté, égalité, fraternité."

At a town meeting in Boston resolutions asking that a city charter be granted were denounced as an effort to "destroy the liberties of the people; ... a link in the chain of aristocratic influence."[70] Titles were the especial aversion of the masses. Even before the formation of our government, the people had shown their distaste for all formalities, and especially for terms denoting official rank; and, after the Constitution was adopted, one of the first things Congress did was to decide against any form of address to the President. Adams and Lee had favored some kind of respectful designation of public officials. This all-important subject had attracted the serious thought of the people more than had the form of government, foreign policy, or even taxes.

Scarcely had Washington taken his oath of office when David Stuart warned him that "nothing could equal the ferment and disquietude occasioned by the proposition respecting titles. As it is believed to have originated from Mr. Adams and Mr. Lee, they are not only unpopular to an extreme, but highly odious.... It has given me much pleasure to hear every part of your conduct spoken of with high approbation, and particularly your dispensing with ceremony, occasionally walking the streets; while Adams is never seen but in his carriage and six. As trivial as this may appear," writes Stuart, "it appears to be more captivating to the generality, than matters[Pg 37] of more importance. Indeed, I believe the great herd of mankind form their judgments of characters, more from such slight occurrences, than those of greater magnitude."[71]

This early hostility to ostentation and rank now broke forth in rabid virulence. In the opinion of the people, as influenced by the French Revolution, a Governor or President ought not to be referred to as "His Excellency"; nor a minister of the gospel as "Reverend." Even "sir" or "esquire" were, plainly, "monarchical." The title "Honorable" or "His Honor," when applied to any official, even a judge, was base pandering to aristocracy. "Mr." and "Mrs." were heretical to the new religion of equality. Nothing but "citizen"[72] would do—citizen judge, citizen governor, citizen clergyman, citizen colonel, major, or general, citizen baker, shoemaker, banker, merchant, and farmer,—citizen everybody.

To address the master of ceremonies at a dinner or banquet or other public gathering as "Mr. Chairman" or "Mr. Toastmaster" was aristocratic: only "citizen chairman" or "citizen toastmaster" was the true speech of genuine liberty.[73] And the name of the Greek letter college fraternity, Phi Beta Kappa, was the trick of kings to ensnare our unsuspecting youth. Even "Φ.Β.Κ." was declared to be "an infringement of the natural rights of society." A college fraternity was destructive of the spirit of equality in American[Pg 38] colleges.[74] "Lèse-républicanisme" was the term applied to good manners and politeness.[75]

Such were the surface and harmless evidences of the effect of the French Revolution on the great mass of American opinion. But a serious and practical result developed. Starting with the mother organization at Philadelphia, secret societies sprang up all over the Union in imitation of the Jacobin Clubs of France. Each society had its corresponding committee; and thus these organizations were welded into an unbroken chain. Their avowed purpose was to cherish the principles of human freedom and to spread the doctrine of true republicanism. But they soon became practical political agencies; and then, like their French prototype, the sowers of disorder and the instigators of insurrection.[76]

The practical activities of these organizations aroused, at last, the open wrath of Washington. They "are spreading mischief far and wide," he wrote;[77] and he declared to Randolph that "if these self-created societies cannot be discountenanced, they will destroy the government of this country."[78]

Conservative apprehensions were thus voiced by George Cabot: "We have seen ... the ... representatives of the people butchered, and a band of[Pg 39] relentless murderers ruling in their stead with rods of iron. Will not this, or something like it, be the wretched fate of our country?... Is not this hostility and distrust [to just opinions and right sentiments] chiefly produced by the slanders and falsehoods which the anarchists incessantly inculcate?"[79]

Young men like John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts and John Marshall of Virginia thought that "the rabble that followed on the heels of Jack Cade could not have devised greater absurdities than" the French Revolution had inspired in America;[80] but they were greatly outnumbered by those for whom Jefferson spoke when he said that "I feel that the permanence of our own [Government] leans" on the success of the French Revolution.[81]

The American democratic societies, like their French originals, declared that theirs was the voice of "the people," and popular clamor justified the claim.[82] Everybody who dissented from the edicts of the clubs was denounced as a public robber or monarchist. "What a continual yelping and barking are our Swindlers, Aristocrats, Refugees, and British Agents making at the Constitutional Societies" which were "like a noble mastiff ... with ... impotent and noisy puppies at his heels," cried the indignant editor of the "Independent Chronicle" of Boston,[83] to whom the democratic societies were "guardians of liberty."[Pg 40]

While these organizations strengthened radical opinion and fashioned American sympathizers of the French Revolution into disciplined ranks, they also solidified the conservative elements of the United States. Most viciously did the latter hate these "Jacobin Clubs," the principles they advocated, and their interference with public affairs. "They were born in sin, the impure offspring of Genêt," wrote Fisher Ames.

"They are the few against the many; the sons of darkness (for their meetings are secret) against those of the light; and above all, it is a town cabal, attempting to rule the country."[84] This testy New Englander thus expressed the extreme conservative feeling against the "insanity which is epidemic":[85] "This French mania," said Ames, "is the bane of our politics, the mortal poison that makes our peace so sickly."[86] "They have, like toads, sucked poison from the earth. They thirst for vengeance."[87] "The spirit of mischief is as active as the element of fire and as destructive."[88] Ames describes the activities of the Boston Society and the aversion of the "better classes" for it: "The club is despised here by men of right heads," he writes. "But ... they [the members of the Club] poison every spring; they whisper lies to every gale; they are everywhere, always acting like Old Nick and his imps.... They will be as busy as Macbeth's witches at the election."[89][Pg 41]